Principles of Neurosurgery,

edited by Robert G. Grossman. Rosenberg © 1991'

Published by Raven Press, Ltd., New York.

CHAPTER 11

Trigeminal and Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia

and Hemifacial Spasm

Ronald I. Apfelbaum

Trigeminal and Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia, 223

Incidence, 223

Etiology and Pathology, 223

Symptoms, 224

Signs, 225

Diagnostic Tests, 225

Treatment, 226

Outcome, 231

Hemifacial Spasm, 231

Incidence, 231

Etiology and Pathology, 231

Symptoms, 232

Signs, 232

Diagnostic Tests, 232

Treatment, 233

Outcome, 233

References, 234

TRIGEMINAL AND

GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NEURALGIA

Incidence

The true incidence of trigeminal neuralgia is not known,

but it has been estimated from some limited epidemio-

logic studies that approximately 5,000 to 10,000 new

cases occur annually in the United States (1). Women

are more commonly afflicted than men, by a margin of

approximately three to two. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia

is much less common, occurring only once for every 70

to 100 cases of trigeminal neuralgia (2).

Etiology and Pathology

Ancient medical writings describe variations in head

and face pain that probably included cases of trigeminal

neuralgia. The first full description of this condition by a

physician is attributed to John Locke in 1677. Nicholas

Andre is credited with recognition of trigeminal neural-

gia as a definite clinical entity in 1756; in 1773 John

Fothergill published a similar account, unaware of the

R. I. Apfelbaum: Division of Neurological Surgery, The Uni-

versity of Utah, School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah

84132.

French physician's earlier contribution (3). From these

beginnings, gradually increasing recognition of trigemi-

nal neuralgia ensued. Because the condition presents as a

well-defined clinical entity and because patients afflicted

with this condition suffer so greatly, a great deal of atten-

tion has been focused on studying the problem and at-

tempting to treat it.

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia, on the other hand, is a

much less common problem and has been recognized

only fairly recently as a distinct clinical entity. Weisen-

berg in 1910 first reported this symptom complex in a

patient with a tumor in the cerebellopontine angle; a

report by Sicard and Robineau in 1920 followed. Harris

first used the term glossopharyngeal neuralgia in 1921.

White and Sweet called attention to the involvement of

some of the vagal fibers and suggested the term vagoglos-

sopharyngeal neuralgia in 1969 (2). Though technically

more precise, this term has not gained widespread use.

In attempting to explain the etiology and pathophysiol-

ogy of these conditions, various authors have hypothe-

sized about the possible roles of trauma, dental pathol-

ogy and suppuration, clinical and subclinical viral

infections, congenital and acquired skull base distor-

tions, demyelinating processes, neoplasms, vascular

compressive lesions, and intrinsic brainstem pathway

dysfunction. Many theories have been advanced and

have enjoyed brief popularity before falling by the way-

side. Thus, for example, when studies demonstrated a.

223

224 / CHAPTER 11

frequent occurrence of herpes virus within the gasserian

ganglion, the virus was advocated as the etiologic agent

of trigeminal neuralgia—until control studies demon-

strated an equally high incidence in asymptomatic indi-

viduals.

The one consistent observation, which holds true both

for patients with demyelinating disease and for those

without, is that there are segmental pathological changes

at the root entry zone of the nerve affecting the centrally

myelinated portion of the nerve (4-7). Central myelin

(derived from oligodendroglial cells) extends a few milli-

meters from the brainstem into the nerve before being

replaced by myelin formed by Schwann cells (8). In elec-

tron-microscopic studies there has been consistent de-

myelination in this area, as well as axonal disruption. In

patients suffering from multiple sclerosis who also have

trigeminal neuralgia, demyelinating plaques are invari-

ably located in this region (and may also be found in

other portions of the trigeminal pathway within the

brainstem).

Walter Dandy first observed the high incidence of vas-

cular channels impinging upon the root entry zone of the

nerve and suggested that this might be the cause of tri-

geminal neuralgia (9). It was not until Dr. Peter Jannetta

applied the operating microscope to the systematic study

of these problems that the truly high incidence of such

root entry zone compression was accurately appreciated

(over 97 percent) (10,11). Several postmortem studies

have confirmed the abnormally high incidence of vascu-

lar lesions in patients suffering from trigeminal neuralgia

as compared to control populations (12-14). This com-

pression appears to be the cause of the demyelination

and is accepted by most, but not all, specialists in this

field as the cause of the symptoms in most patients. The

major exception is in patients with multiple sclerosis,

who of course have intrinsic neural disease.

The anatomical derangement in the nerve apparently

alters the physiology in an as yet incompletely under-

stood manner. Gardner has hypothesized the develop-

ment of a "short circuit" in the nerve at the site of de-

myelination, resulting in touch sensation carried by the

larger afferent fibers actuating thinner pain fibers (15).

Loeser, Calvin, and Howe have suggested that antidro-

mic reflectance of a normal nerve impulse sets up a re-

verberating circuit, explaining how a light touch can trig-

ger a painful paroxysm (16,17).

Because of its rarity, similar pathological studies have

not been performed in patients with glossopharyngeal

neuralgia, but the conditions are otherwise analogous

and are thought to have the same physiological basis.

Symptoms

These conditions are characterized by a very consis-

tent clinical pattern among patients. Patients will experi-

ence brief repetitive paroxysmal spasms of unilateral

pain of extreme intensity, confined entirely to the terri-

tory of one or more divisions of the trigeminal or the

glossopharyngeal nerve. The pain is frequently described

as a "bolt of lightening" or an electric shock-like phe-

nomenon, and patients will often, in describing the pain,

make a characteristic gesture, flinging open a closed

hand to demonstrate the rapid onset and spread of the

pain.

The pain may occur spontaneously but is often trig-

gered by nonpainful tactile stimuli, usually, but not in-

variably, within the territory of the affected nerve. Thus,

in the case of trigeminal neuralgia, the pain may be acti-

vated by a breeze on the face, touching the face lightly,

chewing, talking, or eating. Common activities, such as

face washing, hair combing, and tooth brushing, become

difficult or impossible. The attack of pain is always uni-

lateral, with an approximately 60 to 40 right to left pre-

dominance. Some patients may be unfortunate enough

to suffer from this condition bilaterally (1 to 3 percent),

but the pain is neither simultaneous nor synchronous on

the two sides.

Most patients will not have any underlying back-

ground pain. But an occasional patient may complain of

a burning or drawing feeling after the sharp paroxysm

subsides, and some will note a prickling, burning or

throbbing sensation before the tic starts (18). In obtain-

ing a history, one must also be careful that repetitive

paroxysms occurring in long volleys are not mistaken for

one steady, long pain.

When the diagnosis is doubtful (usually because the

patient is a poor historian) one should inquire about the

patient's behavior during the pain attacks. Patients with

trigeminal neuralgia tend to remain as immobile as possi-

ble and to guard against any contact with the exposed

area. This is in contradistinction to other types of pain

such as cluster headache (Horton's cephalgia), in which

patients tend to pace or throw themselves about, often

crying out. These latter patients may often place hot or

cold compresses on the face or massage the affected area

in an attempt to diminish the pain.

Both trigeminal and glossopharyngeal neuralgia are

conditions that seem to occur with increasing frequency

with advancing age. Contrary to some descriptions, how-

ever, they are not exclusively diseases of elderly patients

and may occur as early as the teenage years in rare in-

stances. The peak age of onset is in midlife, during the

fifth to sixth decades.

In the natural history of trigeminal neuralgia, remis-

sions are common and may last for extended periods of

time. With increased duration of the illness, however,

remissions tend to become shorter and periods of exacer-

bation longer.

Another useful characteristic in the differential diag-

nosis is the infrequent occurrence of nocturnal pain.

Many patients are able to find a comfortable position

TRIGEMINAL AND GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NEURALGIA AND HEMIFACIAL SPASM / 225

and get adequate rest. This condition therefore is not a

chronic pain but rather an acute pain syndrome occur-

ring repetitively. Narcotic analgesics are impotent in this

situation, and thus it is extremely uncommon to find a

patient who is habituated or even a frequent user of nar-

cotics.

There is a well-established association between trigemi-

nal neuralgia and multiple sclerosis. In a large series of

patients with multiple sclerosis, 1 to 2 percent will be

found to have trigeminal neuralgia (19). Conversely, a

similar percentage of patients suffering from trigeminal

neuralgia will be found to have multiple sclerosis. As

previously mentioned, in these patients there is a demye-

linating plaque at the root entry zone of the trigeminal

nerve. The site of pathology, therefore, is in exactly the

same area as that found in trigeminal neuralgia pro-

duced by vascular compression, but in these patients the

disease is intrinsic within the nerve rather than due to an

extrinsic cause. The clinical symptoms are also identical.

The association of glossopharyngeal neuralgia and multi-

ple sclerosis has been documented only rarely.

The symptoms of glossopharyngeal neuralgia are gen-

erally similar to those of trigeminal neuralgia but have

some additional features. The pain resembles that of tri-

geminal neuralgia and occurs as brief paroxysms in the

throat or ear. A higher number of patients, however, ex-

perience a dull, aching, or burning feeling. As in trigemi-

nal neuralgia, the episodes of pain are usually triggered,

the common provocative maneuvers being swallowing,

chewing, coughing, or talking. Patients may experience

paroxysms of coughing with their attacks of pain. Syn-

cope has also been reported, but appears to be a very

uncommon associated symptom. It may be due to hyper-

sensitivity of the carotid sinus nerve, producing asystole.

Signs

The diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia is made by his-

tory. On very close examination with careful attention

being directed to facial cutaneous sensibility, abnormali-

ties may be encountered in as many as 25 percent of

patients; these are minimal changes, which will not nor-

mally be detected on routing neurologic examination.

Of course, if the patient has had prior destructive sur-

gery, appropriate abnormalities may exist.

Tumors in the cerebellopontine angle, which may be a

cause of trigeminal or glossopharyngeal neuralgia, may

produce deficits in several of the lower cranial nerves,

cerebellar dysfunction, and papilledema. These signs

may be detected on a careful neurologic examination.

Diagnostic Tests

There is no specific test that will establish the diagnosis

of trigeminal neuralgia. The diagnosis rests entirely upon

a careful and adequate history. A magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) scan should be performed, with particu-

lar attention paid to the affected nerve in the middle and

posterior fossa, on every patient who has this problem so

as to exclude an underlying neoplasm. Multiple sclerosis

will usually be readily detected on the MRI scan, but if

doubt exists other appropriate tests may include audi-

tory and visual evoked responses and spinal fluid analy-

sis to help establish the diagnosis.

In addition to excluding neoplasms and ruling out

multiple sclerosis, MRI scanning in trigeminal neuralgia

has demonstrated the flow voids of vascular loops adja-

cent to the root entry zone of the affected nerve, with

distortion of the nerve. Abnormal uptake of gadolinium

in the compressed region also may be seen. These

changes in the preganglionic segment of the trigeminal

nerve are best viewed on coronal T,-weighted sequences

(Fig. 1) (20). Scanning also alerts the surgeon to the pres-

ence of dolichoectatic major vessels (Fig. 2), aneurysms,

and vascular malformations. All are infrequent causes of

vascular compression but ones that may require differ-

ent treatment or surgical strategics.

In glossopharyngeal neuralgia, in addition to the

above, a useful diagnostic test is the application of a topi-

cal solution of 10 percent cocaine to the oropharynx.

This will provide several hours of relief, during which the

majority of patients with this problem will be able to eat

and drink without experiencing pain. This time helps to

establish the diagnosis and also aids in predicting the

outcome of surgical treatment.

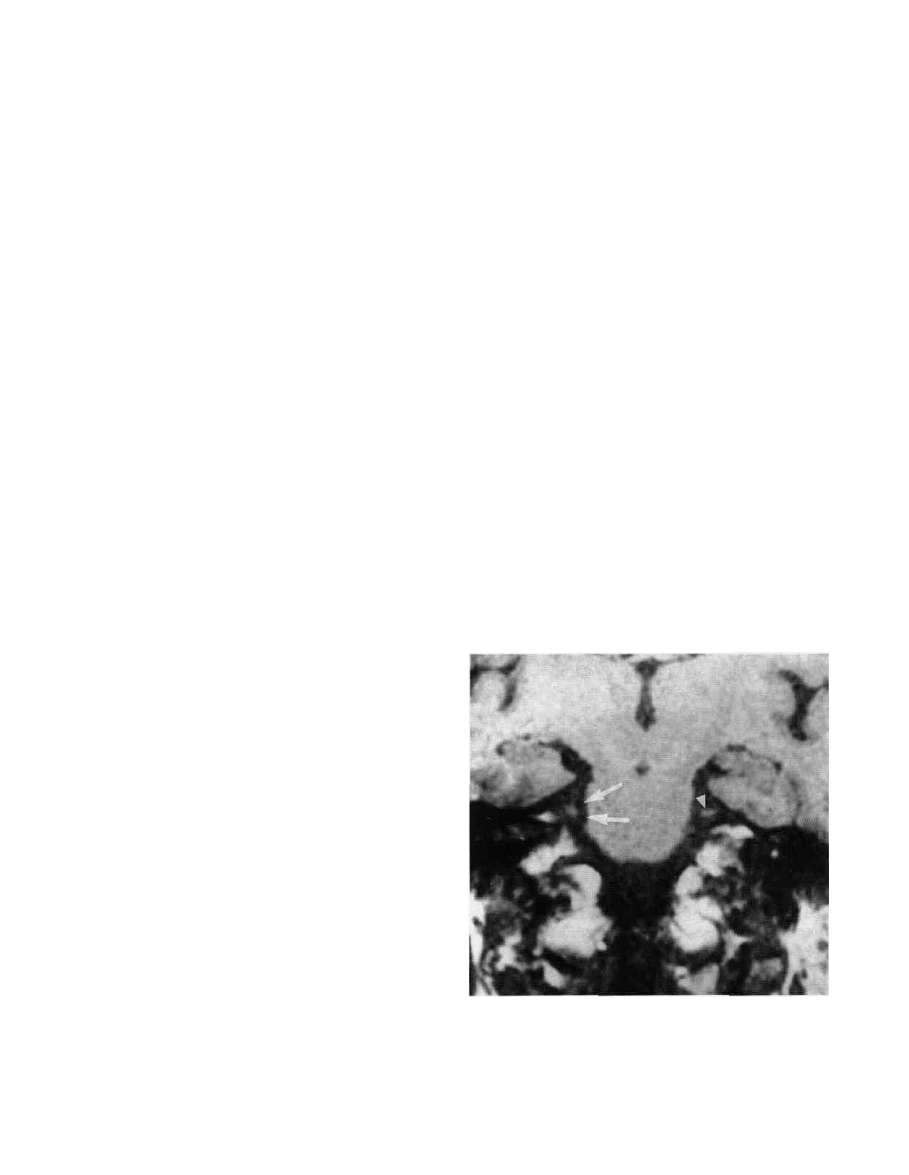

FIG. 1. Coronal T1-weighted MRI demonstrating two flow

voids (arrows) adjacent to and distorting the right pregan-

glionic segment of the trigeminal nerve. Note the normal ap-

pearing left preganglionic segment of trigeminal nerve (arrow

head) for comparison.

226 / CHAPTER 11

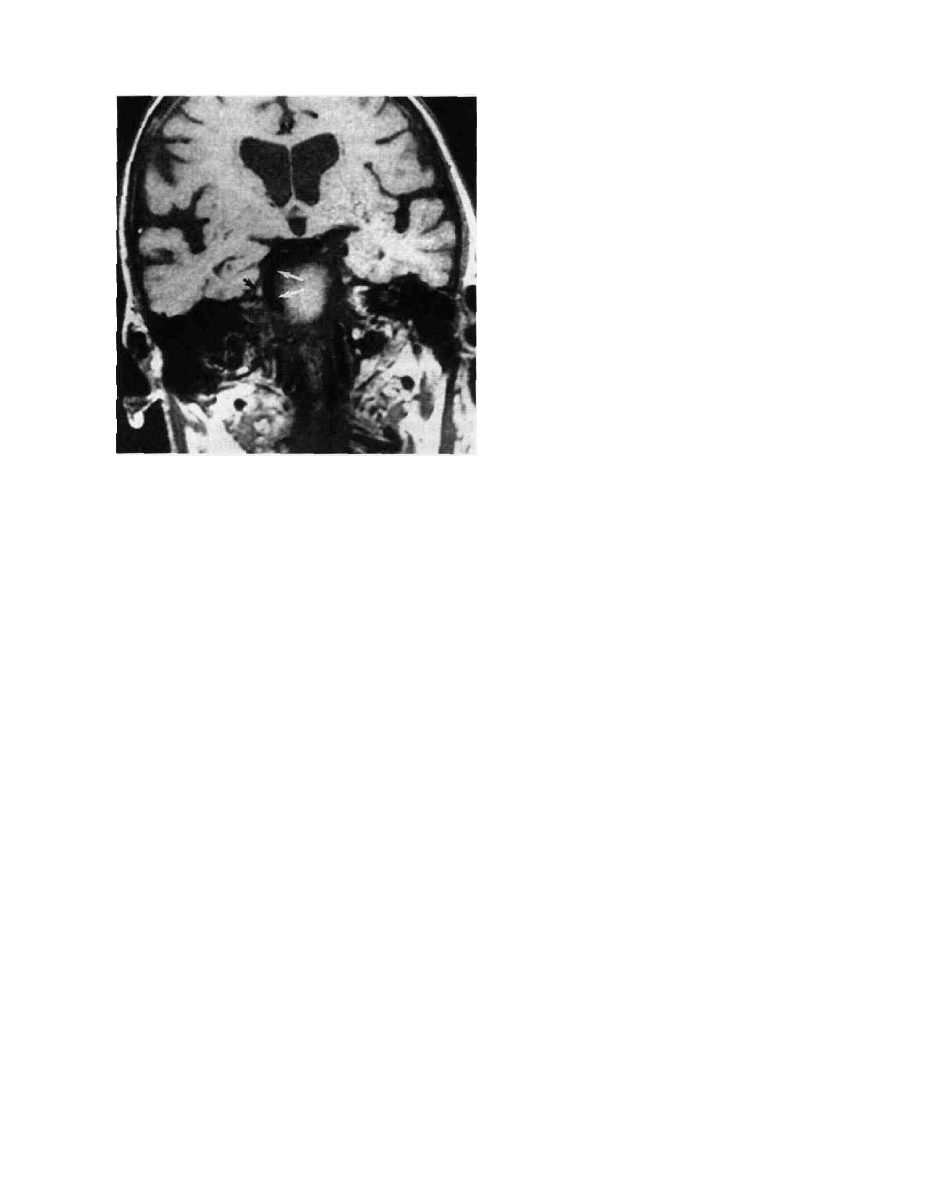

FIG 2 Coronal T1 -weighted MRI demonstrating a large, do-

lichoectatic basilar artery (winte arrows) compressing and

distorting the preganglionic segment of the left trigeminal

nerve (smaller black arrow).

Treatment

The goal of any treatment is to render the patient pain

free at a tolerable level of side effects. The treatment

must provide reliable and consistent pain control so that

not only is the pain relieved but also the fear of pain

recurrence, which can dominate a patient's life. Partial

control is not a satisfactory goal in this day and age.

Trigeminal Neuralgia: Medical

The management of trigeminal neuralgia (21,22) is

first and foremost medical, with surgical treatment re-

served for those patients who are refractory to medical

treatment or who develop toxicity. Two drugs, pheny-

toin (Dilantin®) and carbamazepine (Tegretol®), are the

mainstays of treatment (23). Many physicians prefer to

start with phenytoin because of its lower toxicity, al-

though it is effective only in about one-half of patients

and has a relatively high failure rate after a period of

time. After an appropriate loading dose, 300 to 400 mg a

day will usually be adequate if this drug is effective.

Serum phenytoin levels can be determined and dosage

adjusted to obtain a therapeutic level of 10 to 20 meg/ml.

We usually start with carbamazepine 100 mg twice a

day and increase it by 100 mg every other day until con-

trol is achieved or toxicity develops. Unlike phenytoin,

this drug has no absolute dosage range. Although some

atients may achieve control with as little as 200 mg a

day, many patients will require 1,600 mg or more. An

average dose might be 800 mg per day (200 mg q.i.d.).

This medication should be given with food or milk to

avoid gastric upset. Common subjective side effects in-

clude mental obtundation, sedation, interference with

higher cognitive functions, disequilibrium, and incoordi-

nation. These are usually dose related. Significant liver,

renal, and especially hematologic side effects also occur.

Patients should therefore have periodic blood tests, ini-

tially every two weeks and then at monthly intervals

while on the medication. The development of toxicity

may limit the use of this drug, but it is initially effective

in over 80 percent of the patients treated. Because carba-

mazepine is so effective, the patient's failure to respond

when an adequate dosage can be tolerated should alert

one to reassess the diagnosis.

Phenytoin may be added to carbamazepine and may

increase the effectiveness of the latter or allow good pain

control at a lower dose, reducing side effects. It, of

course, may be used alone in case of carbamazepine intol-

erance or toxicity. Liver function abnormalities, a cuta-

neous rash, disequilibrium, and sedation are some of the

more common side effects and may require discontinu-

ance of the drug.

Baclofen (Lioresal®) and chlorphenesin carbamate

(Maolate®) are second-order drugs that may help some

patients. In our experience they are most useful for pa-

tients who are well controlled on carbamazepine or

phenytoin but who have to stop using these medications

due to toxicity. They rarely provide significant pain con-

trol for any length of time in patients who do not re-

spond to phenytoin or carbamazepine.

Trigeminal Neuralgia: Surgical

Two types of surgical procedures, percutaneous partial

destruction of the trigeminal preganglionic rootlets and

the Jannetta microvascular decompression of the trigemi-

nal nerve via a posterior fossa craniectomy, are the

current operative procedures of choice for patients who

have become refractory or have developed toxicity to

medical therapy.

Percutaneous neurolysis may be accomplished in sev-

eral ways. These techniques have replaced peripheral

nerve sections or injections, and intracranial sections,

because a more controlled selective partial destruction of

the nerve can be produced. This achieves pain control

with some preservation of sensation and provides better

long-term results with less risk.

Percutaneous radiofrequency thermal lesioning of the

trigeminal nerve was introduced by Sweet and Wepsic in

1974 (24) as a refinement of earlier gross electrocoagula-

tion techniques of the gasserian ganglion pioneered by

Kirschner in 1931. Radiofrequency lesioning requires

only a brief hospitalization.

TRIGEMINAL AND GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NEURALGIA AND HEMIFACIAL SPASM / 227

The procedure can be performed in the x-ray depart-

ment or in an operating theater. Neuroleptic analgesia is

utilized. The patient is sedated with droperidol 150 mg

per kg IM, and fentanyl 50 mg is given intravenously

initially. Supplemental increments of 25 mg of fentanyl

are given as needed, titrating the patient's perception of

pain against the patient's mental state to avoid obtunda-

tion. Fentanyl is a short-acting agent that facilitates good

control of the patient's discomfort, while allowing the

patient to cooperate during the procedure. Such coopera-

tion is essential for proper and safe performance of this

procedure. Some surgeons supplement the above by in-

ducing brief deeper anesthesia with methohexital (Brevi-

tal®) during the more painful moments of the procedure.

A needle electrode is inserted in the cheek approxi-

mately 2 cm lateral to the corner of the mouth and

through the foramen ovale under radiographic control,

utilizing the Hartel technique (Fig. 3) (25). Once the nee-

dle is in place, the stylet is withdrawn and an electrode is

inserted through the needle. Stimulation is then used to

localize the appropriate divisions of the trigeminal

nerve, adjusting the electrode's position as necessary.

Proper localization is achieved when the patient per-

ceives a nonpainful vibratory or paresthetic sensation in

the appropriate division at a threshold of under 0.4 volts

(50 Hz, 2.5 msec continuous pulse train). The radiofre-

quency current is then placed on the electrode, which

raises the temperature of the electrode tip, producing

some thermocoagulation of the preganglionic trigeminal

nerve fibers. After each incremental lesion, the patient is

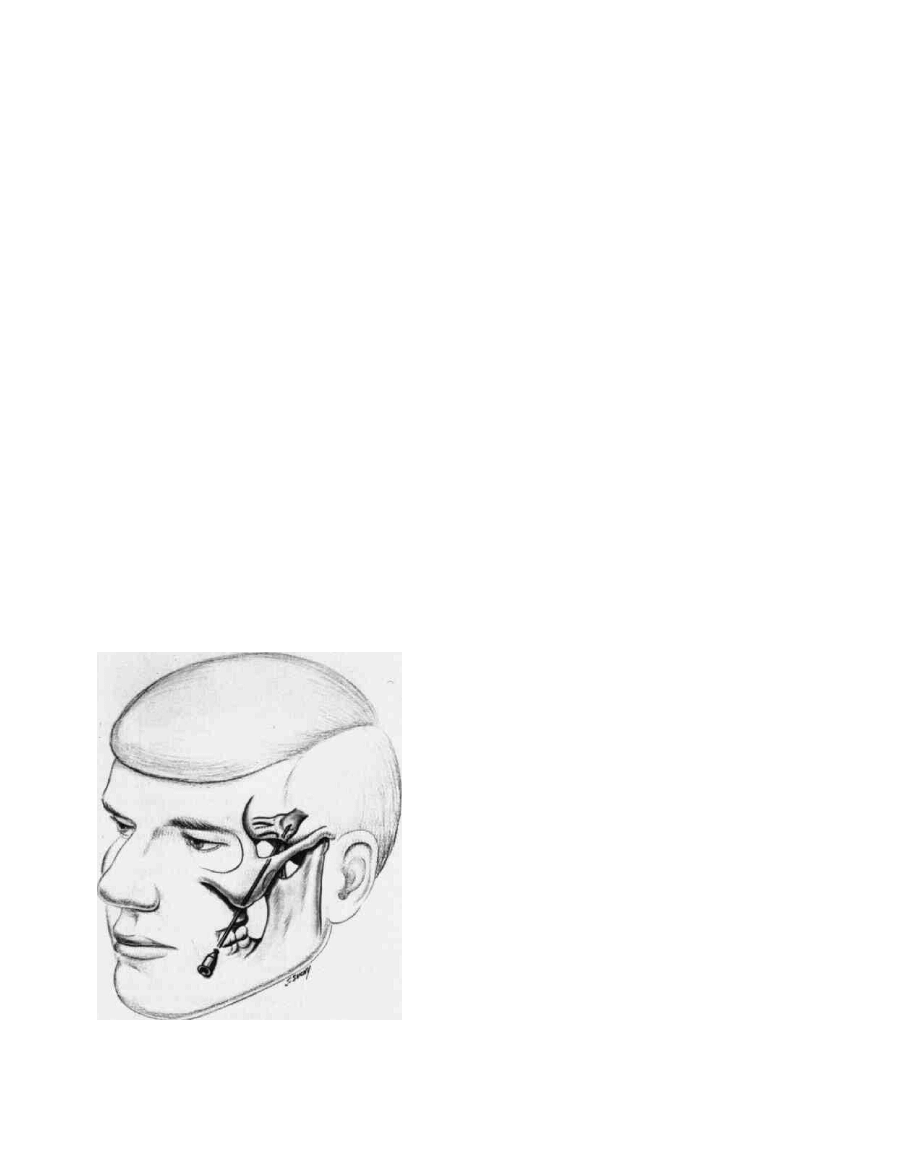

FIG. 3. Placement of the needle through the lateral cheek

and into the gasserian ganglion for percutaneous radiofre-

quency lesioning. (From reference 51, with permission.)

tested and the procedure is terminated when moderate

or greater hypalgesia in the affected area is achieved.

Using carefully applied, small, graded increments of

heating, one can usually remove pain perception while

preserving some useful touch in the treated area, since

the thin unmyelinated pain fibers are more sensitive to

thermal destruction than the larger myelinated touch

fibers. At times the lesion will spread to adjacent divi-

sions of the nerve, producing a larger area of numbness

than desired.

This procedure can be well tolerated even by elderly or

medically debilitated patients. Patients must be aware

that this procedure will permanently alter facial sensa-

tion, producing significant numbness in 90 percent of

our patients, and that it may produce corneal anesthesia

if the first division is affected or the lesion spreads to

involve that division. Most patients are willing to accept

this small risk (18 percent experience decreased or ab-

sent corneal sensation; 2 percent corneal ulceration or

keratitis)* and can tolerate the numbness fairly well. An

occasional patient, however, will be greatly bothered by

the numbness. If there is any doubt as to a patient's abil-

ity to tolerate numbness, nerve blocks can be performed

to remove sensation temporarily so as to allow the pa-

tient to experience this numbness prior to deciding

whether or not to accept the procedure. I have found it

helpful to describe the altered facial sensation to the pa-

tient as similar to the feeling when a dental anesthetic

has partially worn off. The patient must be aware, how-

ever, that, unlike a dental anesthetic, this sensation will

be a permanent one and cannot be reversed.

More troublesome is the occurrence of dysesthetic

sensations (20 percent), which usually are fairly mild and

well tolerated but in a small percentage (4 percent) can

be quite severe and troublesome. These latter patients,

who suffer from analgesia or anesthesia dolorosa, are

bothered by constant and severe burning, itching, or

crawling sensations, which they may find as intolerable

as their initial trigeminal neuralgia pain. Unfortunately,

these sensations are refractory to treatment, although

some patients will respond to a combination of Trila-

fon 4 mg and amitriptyline hydrochloride (Elavil®) 25

mg q.i.d.

Some authors with greater experience have advocated

making less dense lesions to produce mild to moderate

rather than dense analgesia. This procedure, they claim,

is equally effective in relieving the pain but significantly

decreases the risks of corneal anesthesia and dysesthetic

sequelae (31).

Other unwanted side effects that have been reported

include the rare occurrence of intracranial infections and

* The percentages expressed here represent my personal experience

with 134 patients treated over 10 years by this technique. On analysis,

these percentages agree with many large published series (26-30).

228 / CHAPTER 11

abscesses, and injury to the third, fourth, and sixth cra-

nial nerves. Punctures of the carotid artery and cavern-

ous sinus usually are benign, but on occasion carotid

cavernous fistula and/or cerebral vascular accidents

have been reported. These latter complications, how-

ever, are all exceedingly rare.

Patients may resume full activity and diet immedi-

ately after recovery from the anesthetic and are usually

discharged the following day. There are no restrictions of

their activities after this procedure.

Percutaneous chemoneurolysis with glycerol was intro-

duced in 1981 by Hakanson (32). In this approach, pure

anhydrous glycerol (99.5 percent) is instilled into the tri-

geminal cistern under fluoroscopic control. It is not clear

whether the effect of the glycerol is due to chemical or

hyperosmotic damage to the trigeminal nerve pregan-

glionic rootlets. In any case, the effect is to produce ex-

cellent pain relief with usually only minimal sensory loss

at times none. Some patients, however, will get

significant sensory loss (4 percent), even anesthesia,

though the latter usually occurs only with sequential de-

structive procedures. In 158 patients treated with this

technique over seven years, we have only rarely observed

corneal anesthesia (4 percent) and have never seen kera-

titis develop as a sequela to the procedure. Dysesthetic

sensations are also very infrequent (3 percent) and

usually quite mild. Anesthesia dolorosa has not been re-

ported from this procedure (33).

We perform the procedure in the x-ray suite, using the

same technique for puncturing the foramen ovale under

direct fluoroscopic guidance that we use for radiofre-

quency lesioning (25). The entry site, approximately 2 to

3 cm from the corner of the mouth, is selected fluoro-

scopically (Fig. 4A) by placing the patient with his neck

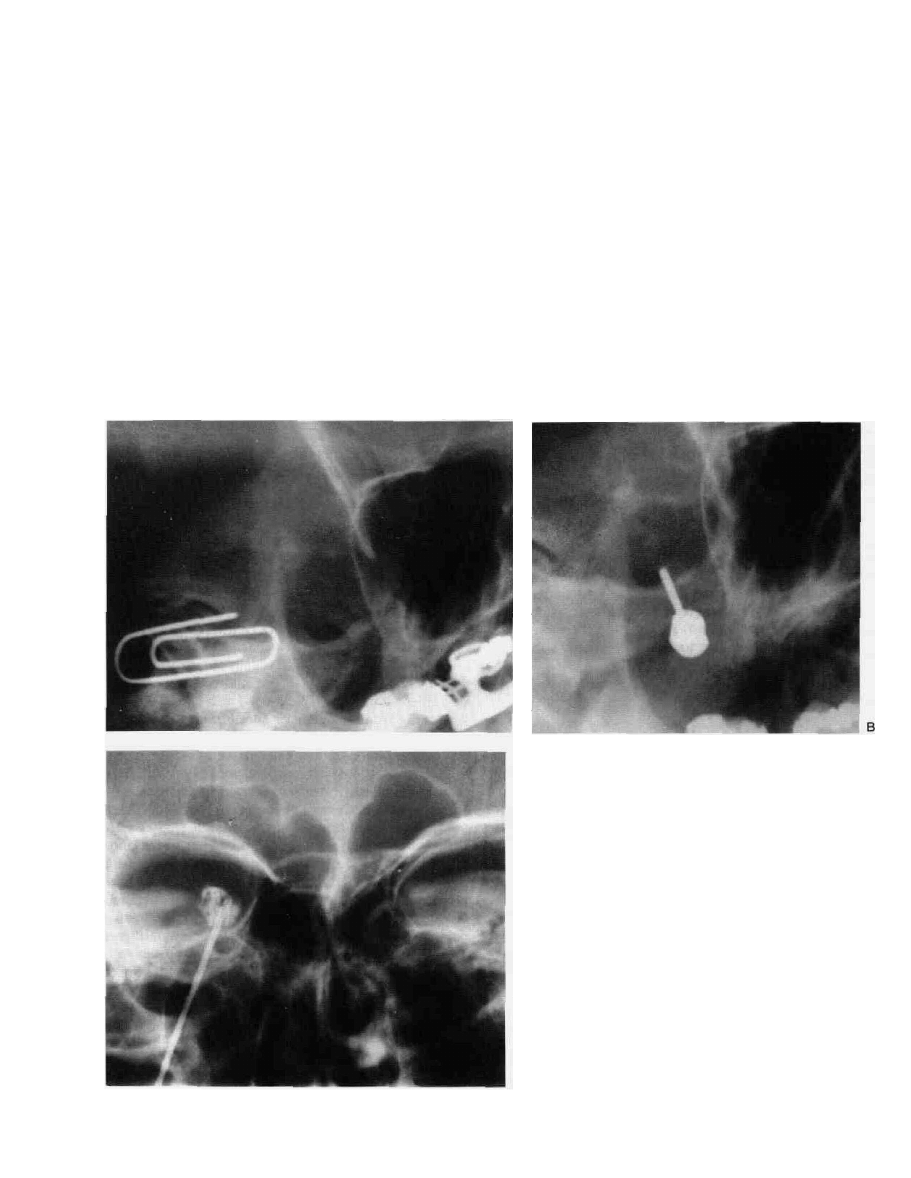

FIG. 4. Fiuoroscopic images during glycerol chemo-

neurolysis for trigeminal neuralgia. (A) Initial scout view

showing paper clip on skin at entrance site and end-on

view of foramen ovale. (B) Needle has now been in-

serted into the medial end of the foramen ovale, under

direct fluoroscopic imaging. (C) Trigeminal cisterno-

gram, AP projection with patient in upright position.

Preganglionic rootlets are visible as linear filling defects

within the cistern.

TRIGEMINAL AND GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NEURALGIA AND HEMIFACIAL SPASM / 229

hyperextended and head rotated to the contralateral side

about 15 to 20 degrees. This allows visualization directly

along the needle pathway, with the foramen ovale seen

projecting over the petrous ridge.

Needle puncture and advancement through the fora-

men ovale is accomplished with the patient briefly anes-

thetized using 40 to 60 mg of methohexital. It is impor-

tant that the foramen ovale be punctured at its medial

end to properly engage the trigeminal cistern. This can

be reliably accomplished using the fluoroscopic tech-

nique described above and placing the needle through

the foramen as its progress is being monitored (Fig. 4B).

Once the needle is in place and a free flow of cerebro-

spinal fluid (CSF) is obtained, the patient is allowed to

awaken. A cisternogram is then performed by connect-

ing a J ml syringe and extension tubing filled with io-

hexol (Omnipaque®, Winthrop Pharmaceuticals, New

York) (350 mg% concentration) to the needle, tilting the

x-ray table to the vertical position, and slowly injecting

the contrast agent while fluoroscoping in the anteroposte-

rior (AP) projection. If the needle is properly placed, the

contrast will fill the small cup-shaped trigeminal cistern

(Fig. 4C), then overflow into the posterior fossa. The

cisternogram confirms the correct placement and also

allows quantification of the size of the trigeminal cistern.

If not in the cistern (for example. CSF can be obtained in

the subarachnoid space beneath the temporal lobe), the

needle must be repositioned.

After satisfactory placement and cisternogram, the pa-

tient is again placed recumbent to allow the contrast

agent to flow out of the cistern; this is confirmed fluoro-

scopically. The patient then is placed back on a stretcher

in a full upright sitting position, and a quantity of glyc-

erol equal to the volume of the cistern is instilled slowly.

This may produce trigeminal pain, so it is best to pre-

medicate with analgesics, such as fentanyl, first. The pa-

tient is then transported back to his or her room but kept

sitting up at all times for about two hours to keep the

glycerol in the trigeminal cistern.

Most patients are pain free within a few hours and

may be discharged the following morning. Some will

continue to have tic pain for 7 to 10 days, though usually

it is distinctly less. Ten percent will require a second

procedure to get full relief. Once relieved. 75 percent

were still pain free after three years. For those with recur-

rence, the procedure can be readily repeated and has

been tolerated well so that there usually is no reluctance

on the patient's part to accept a repetition (unlike radio-

frequency lesioning).

Percutaneous compression of the gasserian ganglion

with a balloon catheter was introduced by Mullan in

1983 as technique to traumatize the trigeminal ganglion

and preganglionic rootlets mechanically using a percuta-

neously inserted balloon-tipped catheter (34). The cath-

eter is placed through the foramen ovale, using a similar

approach to the above two techniques, and then inflated

to compress the neural structures. The technique is

based on the earlier observation of Taarnhoj that me-

chanical trauma could relieve the pain of trigeminal neu-

ralgia, often for a significant period of time (35).

While long-term follow-up is not yet available, the ini-

tial results of this procedure appear to be comparable to

glycerol chemoneurolysis, with significantly less anesthe-

sia, dysesthesia, and corneal anesthesia than following

radiofrequency lesioning.

The Jannetta microvascular decompressive procedure,

in contradistinction to percutaneous neurolysis, in-

volves a formal operative procedure under general anes-

thesia. As such, it will always carry with it a higher risk. It

offers, however, the significant benefit of treating what

appears to be the probable cause of this problem and

achieving relief without neural destruction. Patients who

undergo this procedure, therefore, must accept a slightly

higher risk of serious complications but may be "cured"

of their problem without sacrificing neural function. We

usually reserve this procedure for the younger patient

(under 65) who is in good health and who is willing to

accept the somewhat higher risk to achieve these goals.

The procedure involves a limited suboccipital retro-

mastoid craniectomy performed under general endotra-

cheal anesthesia (35). I and many other surgeons have

preferentially used a sitting position for this operation;

however, equally satisfactory results can be achieved uti-

lizing a lateral, recumbent, or prone position. Access to

the trigeminal nerve is achieved by placing the craniec-

tomy just below the transverse sinus and just medial to

the sigmoid sinus. Opening the dura close to these ve- ,

nous sinuses allows exposure of the cerebellopontine an-

gle along the superior lateral margin of the cerebellum,

which is retracted gently. Prior microsurgical experience

and the use of the operating microscope are mandatory

for safe and accurate dissection. The petrosal vein is

usually coagulated and divided to gain access to the re-

gion of the trigeminal nerve, and the arachnoid around

the nerve is opened widely to inspect this area fully.

Elongated arterial loops impinging upon and cross-

compressing the root entry zone of the trigeminal nerve

are the most common findings in patients undergoing

this operation (Fig. 5A). In our personal series of over

300 cases, these were encountered 79 percent of the time

(36,37). Occasionally, venous channels impinging upon

the nerve in a similar manner were found (15 percent)

and, on rare occasions, tumors in the cerebellopontine

angle, such as meningiomas, acoustic neurinomas, or

cholesteatomas, were seen (3 percent). No pathology was

found in 3 percent of these patients. When tumors are

encountered, they are removed. Veins can be coagulated

and divided to decompress the root entry zone of the

nerve. Arterial channels are dissected completely free of

the root entry zone and secured with a small plastic

sponge prosthesis, usually Ivalon® (Unipoint Industries,

High Point, North Carolina) or a shredded teflon sponge

230 CHAPTER 11

B

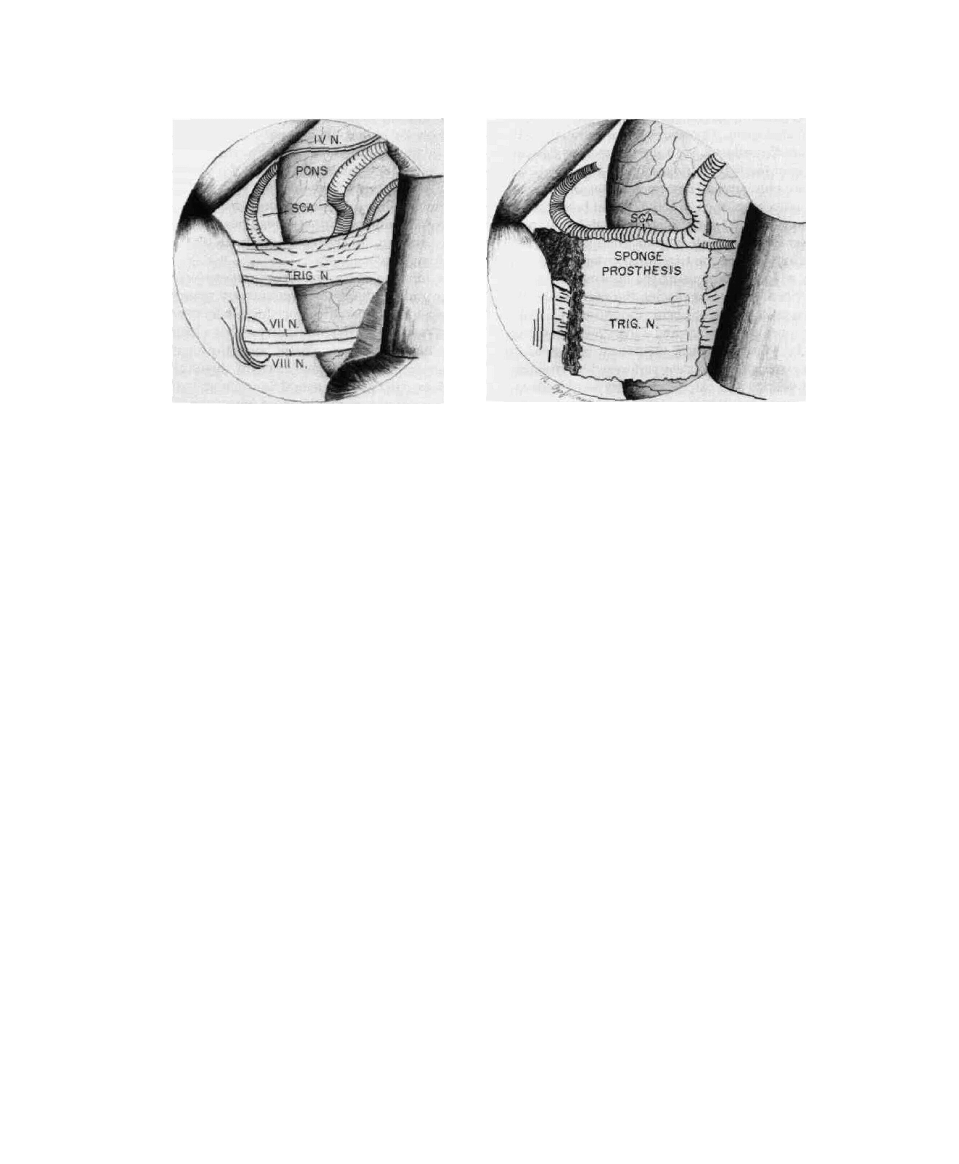

FIG. 5. (A) View through the operating microscope of the left trigeminal nerve, compressed by an

elongated superior cerebellar artery (SCA) as it traverses the brainstem. The artery is caught in the axilla

between the nerve and brainstem. (B) View after elevation of the arterial loop and placement of the

plastic prosthesis to prevent the reapposition of artery and nerve. (From reference 36, with permission.)

(Fig. 5B). The goal is to redirect the arterial pulsation

away from the root entry zone. Our operative findings

fully support those of Jannetta, and our results and fol-

low-up closely agree with those he has reported (38,39).

After satisfactory decompression, the dura is closed in

a watertight fashion and the wound is closed in layers.

We routinely place our patients on steroids preopera-

tively and for 24 hours postoperatively. Most patients

tolerate this procedure well and are able to begin oral

intake and get out of bed on the first postoperative day. If

the patients are operated on in the sitting position, they

usually have a moderate postoperative headache, which

can be controlled with oral analgesics. The majority of

patients can be discharged five to seven days postopera-

tively and usually take another week or two of additional

convalescence at home. During this period, they are en-

couraged to increase their activities gradually.

As with any operation, this procedure is not without

risk and fatal complications have ensued (1 percent).

Cerebellar hematomas or hemorrhagic infarction (1.6

percent) and supratentorial strokes (1 percent) have oc-

curred and at times have been responsible for fatalities,

despite vigorous appropriate treatment. Other signifi-

cant complications have included transient fourth-nerve

palsies (4 percent), transient facial nerve palsies (1.6 per-

cent), and unilateral hearing loss (2 percent; 1 percent

severe).

In trigeminal neuralgia associated with multiple sclero-

sis, if medical treatment is unsuccessful, relief can be

effected only by a destructive procedure. Percutaneous

lesioning is therefore the procedure of choice. If this is

unsuccessful for technical reasons, section of the nerve in

the posterior fossa will produce a similar benefit and, if

performed immediately adjacent to the brainstem, pro-

duces a lower incidence of dysesthesia and of numbness

than more peripheral destruction of the nerve.

There is a somewhat higher incidence of bilateral tri-

geminal neuralgia in patients afflicted with multiple scle-

rosis than occurs otherwise. In a small percentage of pa-

tients, trigeminal neuralgia may be the initial presenting

symptom of multiple sclerosis. This may explain the oc-

casional negative posterior fossa exploration, especially

in the younger patients.

Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia

The medical principles of treatment as outlined for

trigeminal neuralgia apply equally to this condition. If

these are unsuccessful, the Jannetta micro vascular de-

compression appears to be the definitive procedure of

choice, offering, as with trigeminal neuralgia, the oppor-

tunity for the relief of pain without sacrificing neural

function (38,39).

Radiofrequency lesioning at the jugular foramen has

been attempted, but this only produces a lesion distal to

the ganglion. Thus, recurrences in a few months can be

expected, as with peripheral nerve sectioning.

An alternative procedure involves sectioning of the

glossopharyngeal nerve and the upper several fascicles of

the vagus nerve in the posterior fossa (2). This procedure,

employed since its introduction by Love in 1948, is pref-

erable in more elderly patients, rather than exposing

them to increased operating time and the risks of manip-

ulating their intracranial vessels.

Potential complications and postoperative care are as

described above for trigeminal neuralgia. After section-

ing of the nerve, dysphagia may occur, as well as unpleas-

ant pharyngeal sensations.

TRIGEMINAL AND GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NEURALGIA AND HEMIFACIAL SPASM / 231

Outcome

Success in relieving the pain of trigeminal neuralgia

has been achieved in about 95 percent of the patients

treated with either of these two types of procedures. Re-

currences following percutaneous radiofrequency le-

sioning have varied significantly in different series, but

average approximately 35 percent within four years.

There is an increasing incidence of recurrences with the

passage of time after surgery. Recurrences may occur in

the treated area but are more common in adjacent un-

treated regions. If necessary, the procedure can be re-

peated and many surgeons have preferred to produce

minimal lesions, minimizing numbness and decreasing

the risk of corneal anesthesia and dysesthetic sequelae,

while accepting a higher recurrence rate and repeating

the procedure as often as necessary (27).

With the Jannetta microvascular decompression, re-

currences, when they occur, tend to occur early, usually

within the first year to 18 months, with only a rare recur-

rence being reported after that. Severe refractory recur-

rences have occurred in 13 percent of our patients. An

additional 19 percent of our patients have had some

pain, which was well controlled with medication, usually

at very low dosages. Many of these patients (about one-

half) subsequently have been able to discontinue the

medication. All were refractory to medical treatment pre-

operatively, and most have reported that they feel the

procedure was of significant benefit to them, even if they

have required additional medication. Thus the overall

success rate for excellent (painfree) and good (controlled

pain) results is 87 percent.

Both of these procedures, therefore, offer great poten-

tial for the relief of this severe, incapacitating pain. Pa-

tient satisfaction with either has been gratifying, though

patients undergoing microvascular decompression are

significantly happier, since they do not have any sensory

loss, with its annoyance serving as a constant reminder

of their problem. The lack of dysesthesia and fewer recur-

rences also contribute to this increased satisfaction.

The choice of procedure must ultimately be made by

the patient, after he or she has achieved a thorough un-

derstanding of the potential risks and benefits of each.

The physician's recommendation also must be based on

a careful analysis of the patient's general health. For the

patient under age 65, in good general health, we usually

recommend the Jannetta microvascular decompression.

Glycerol chemoneurolysis is our preferred technique for

those patients who do not meet the above criteria, who

have multiple sclerosis, who do not wish to accept the

risks of microvascular decompression, or who have a re-

current tic after a prior surgical procedure.

The results in glossopharyngeal neuralgia are similar,

in a smaller number of reported cases treated with the

Jannetta procedure, and also with sectioning of the

nerve. The frequency of recurrence after microvascular

decompression approximates that seen in trigeminal neu-

ralgia and is less with nerve sectioning if the upper vagal

rootlets are included.

HEMIFACIAL SPASM

Incidence

Hemifacial spasm is a relatively rare condition. There

are no published epidemiologic studies, so its true inci-

dence is not known. From personal experience I would

estimate this condition to be approximately 25 percent

as common as trigeminal neuralgia. This may not be a

true figure, however, because many individuals may en-

dure rather than seek treatment for this condition, which

is neither life threatening nor painful. Also great regional

variation in incidence occurs, with an especially high fre-

quency of occurrence noted in Oriental (especially Japa-

nese) patients.

Etiology and Pathology

Hemifacial spasm appears to be the direct motor ana-

logue of trigeminal neuralgia. That is, both are disorders

of paroxysmal hyperactivity occurring in a cranial nerve.

Hemifacial spasm involves the facial nerve and as such

manifests pure motor hyperactivity, in comparison with

trigeminal neuralgia, which occurs in a primarily sen-

sory nerve and causes paroxysms of pain.

Significant historical observations have noted that, if

the nerve is sectioned at the stylomastoid foramen and

anastomosed to itself, the spasms return with reinnerva-

tion. If, however, an anastomosis to another cranial

nerve is performed, the spasms do not return. Thus the

site of pathology must be proximal to the stylomastoid

foramen. It has also been observed that a supratentorial

stroke producing a hemiplegia does not relieve the spasm

even in an otherwise plegic face (40). Therefore, the

pathological process must be confined to the lower mo-

tor neuron.

Isolated case reports dating back to an autopsy study

by Schultze in 1875 (41) have demonstrated vascular

lesions compressing the facial nerve in the posterior

fossa. Campbell and Keedy published two cases in 1947

in which a "cirsoid aneurysm" (nowadays known as ver-

tebral basilar dolichoectasia) was found compressing the

facial nerve (42). Other isolated case reports support

these observations. Tumors compressing the facial nerve

in the posterior fossa and causing hemifacial spasm were

noted by Dandy (43,44) and Gushing (45). In 1961

Gardner and Sava presented their experience with 19

patients (46). In 14 of these they found mass lesions. In

the majority of cases, the problem appeared to stem from

either normal or abnormal blood vessels. Gardner and

CHAPTER 11

Sava also suggested that hemifacial spasm was a revers-

ible pathophysiological state.

It was not until the systematic application of the oper-

ating microscope by Peter Jannetta, commencing in

1967, that a large series of observations was made in

patients with hemifacial spasm. Jannetta not only firmly

established that root exit zone compression of the facial

nerve is present in virtually every patient afflicted with

this problem but also devised a nondestructive tech-

nique for moving the blood vessel (which is the common

cause) away from the nerve and securing it with a small

sponge prosthesis to decompress the nerve effectively.

Jannetta's observations have been substantiated by sev-

eral other surgeons (36,47), firmly establishing the etiol-

ogy of hemifacial spasm.

The exact physiological effect that this root exit zone

compression produces is not fully understood. Hunt in

1909 detailed the role of sensory afferent fibers in the

facial nerve. Gardner suggested a reverberating circuit

produced by afferent-efferent transaxonal "short-circuit-

ing" (46).

Symptoms

Hemifacial spasm usually begins with small, uncon-

trollable twitching movements occurring in a unilateral

orbicularis oculi muscle, with a slow and insidious pro-

gressive spreading of the spasms down the face. The hy-

peractivity is limited entirely to muscles supplied by the

seventh cranial nerve. The twitching is involuntary and

patients are unable to stop it.

The condition tends to worsen gradually with the pas-

sage of time, often slowly over months to years until

gross disfiguration of the face occurs. Far from being

only a cosmetic problem, hemifacial spasm creates signif-

icant functional disability because of the limitations on

vision imposed by the constant blinking and twitching.

This can impair many normal daily activities such as

reading and driving. With increased severity, the pla-

tysma muscle in the anterior neck and the corrugator

muscles of the forehead may ultimately become in-

volved. Jannetta and associates have also described an

atypical form of this problem, which starts in the mid-

face and advances up to the forehead (48).

Hemifacial spasm is slightly more common in men

and more common on the left side of the face. It has not

been described in children. Like many neurologic prob-

lems it will be aggravated by psychological stress as well

as fatigue and has therefore been erroneously thought to

have an emotional basis. Voluntary movement may ag-

gravate the spasms. Spasms often stop during sleep but

may persist in about 10 percent of patients. Bilaterality

has been described (6 percent), but, when this occurs, the

spasms are neither synchronous nor symmetrical.

Hemifacial spasm has been reported in association

with trigeminal neuralgia. Gushing apparently was the

first to describe this under the term "tic convulsif" (49).

Most commonly, mass lesions in the posterior fossa, re-

sulting in compression of both the fifth and seventh

nerves, have been associated with this combination. Sep-

arate independent lesions, however, may also occur.

Signs

The clinical appearance of patients suffering from this

problem is quite characteristic. Intermittent, uncontrol-

lable, brief, repetitive, and painless spasms of the facial

musculature, most prominent in the midface, are noted.

Occasionally the "tonus" phenomenon occurs, in which

sustained forceful contractures, usually of the midface

musculature, last for several seconds or even longer.

Physical examination will usually reveal abnormalities

of the cranial nerves. Mild facial paresis (between

spasms) may be noted, as well as mild decreased hearing

in the ipsilateral ear, in long-standing cases. Deficits in

cranial nerves V, VII, or IX or cerebellar or brainstem

findings suggest a mass lesion in the cerebellopontine

angle.

Diagnostic Tests

The diagnosis of hemifacial spasm can be made by the

clinical appearance in association with the history as

given above. There is remarkable consistency among pa-

tients in clinical presentation. On electrical testing, the

EMG in hemifacial spasm is quite characteristic, demon-

strating rhythmically occurring bursts of 5 to 20 dis-

charges per second, along with individual discharges and

longer lasting bursts (50). The rate of discharge of the

latter may be as high as 150 to 250 per second, with

almost complete synchronization of the discharges occur-

ring within the entire area of the affected facial muscles.

These electrical findings are not seen in other conditions

and will therefore differentiate hemifacial spasm from

other types of abnormal facial motor activity.

The differential diagnosis of hemifacial spasm in-

cludes blepharospasm, which is a bilateral forced con-

tracture of the muscles about the eyes and is distin-

guished from hemifacial spasm by its bilaterality and its

confinement entirely to the periorbital musculature. Fol-

lowing Bell's palsy, at times, synkinetic movements of

the face may mimic hemifacial spasm. This history of

antecedent Bell's palsy with the development of such

movements as the nerve regenerates usually will distin-

guish these, but electrical testing may be helpful. An-

other condition, facial myokymia, results in writhing

worm-like movements of the facial musculature. This is

seen with intrinsic brainstem disease and, again, can be

differentiated electrically if the clinical situation is not

clear-cut.

TRIGEMINAL AND GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NEURALGIA AND HEMIFACIAL SPASM / 233

As in trigeminal neuralgia, a MR scan may disclose a

vascular loop but mainly is done to rule out a mass le-

sion.

Treatment

There is no effective medical treatment for hemifacial

spasm. This condition has been described as "socially,

psychologically and economically disabling" (48). There-

fore, surgery is of much more than cosmetic significance.

A number of procedures involving methods of destroy-

ing or injuring the facial nerve have been attempted but

result in incomplete relief of the problem and facial palsy

to some extent.

Some success has been achieved with partial denerva-

tion of the facial muscles by injecting botulinum toxin

into the most active regions. With small incremental in-

jections, denervation can be limited and the spasms re-

duced. Denervation of course does not fully resolve the

problem and may require repetitive treatments, but it

can be considered as an alternative, especially in elderly

or infirm patients.

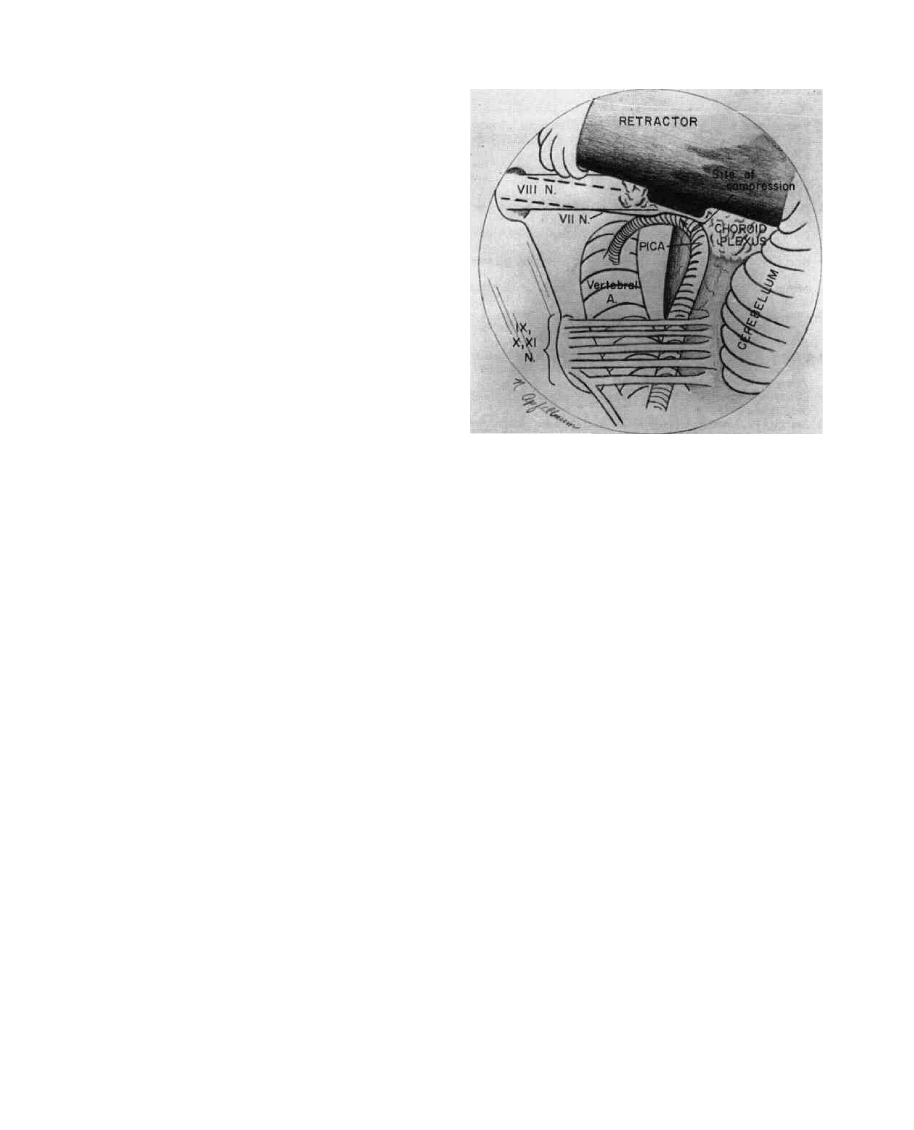

The definitive treatment of this problem is the Jan-

netta microvascular decompressive operation, which in-

volves a limited retromastoid posterior fossa craniec-

tomy and microsurgical exploration of the root exit zone

of the facial nerve. Lesions impressing upon the nerve at

this area have been found in close to 100 percent of pa-

tients in several large series explored by this technique

(Fig. 6). Most commonly these are arterial channels, ei-

ther normal vessels (usually the posterior inferior cere-

bellar artery, the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, or the

vertebral artery) or dilated or ectatic vessels (previously

called cirsoid aneurysms), but on occasion venous chan-

nels, arteriovenous malformations, aneurysms, and

small tumors have been encountered. These latter of-

fending causes are surgically removed. Arterial channels

are dissected free of the nerve and secured with a small

plastic sponge prosthesis to prevent their reappostion.

The operative technique is similar to that employed in

the Jannetta operation for trigeminal neuralgia, except

that the exposure is from lateral inferior, beneath the

cerebellum (36,48).

Outcome

The Jannetta procedure has resulted in excellent relief

of hemifacial spasm in the vast majority of patients so

treated. Jannetta in 1980 reported excellent results in

213 of 229 patients (12 patients required a second proce-

dure) (39). An additional 11 patients (5 percent) had less

than 25 percent of their preoperative level of spasms but

were not completely relieved. The procedure failed in

five patients (2 percent).

FIG. 6. Surgeon's view through the operating microscope.

Exposure of left facial nerve. When the cerebellum is ele-

vated, the root exit zone of the facial nerve is seen to be

compressed by an elongated loop of the posterior inferior

cerebellar artery (PICA). (From reference 36, with permis-

sion.)

In our personal series of 66 patients, we have found

vessels compressing the nerve in 65 cases: 64 were arte-

rial channels and 1 was a venous channel. A bony exos-

tosis compressed the nerve in the remaining case. No

negative explorations occurred. All patients were ini-

tially relieved of their spasm, although the spasm did

persist in the postoperative period for up to several

months in 10 percent of these patients before finally sub-

siding. Recurrences have appeared in 16 patients. Nine

were transient and resolved completely, four were mini-

mal not requiring further treatment, and two were signifi-

cant. One of these has been relieved by a second opera-

tion. Facial weakness was noted in six patients but was

only minimal in three. All these patients have recovered

from it.

This procedure, of course, involves a formal craniot-

omy under general anesthesia and will always carry with

it a small but real element of risk. In addition to the

generalized risks detailed earlier regarding this operative

technique for trigeminal neuralgia, the procedure as ap-

plied to the facial nerve carries with it the primary risk of

injury to the facial and/or auditory nerve. Thus, hearing

loss has been reported in the literature in approximately

8 percent of patients and facial weakness in 7 percent. In

our own experience, we have encountered hearing loss in

only one patient (2 percent) and, as noted, no permanent

facial weakness.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

ZX50 cap 11 (carburatore)

neural defect cap 19

Zarz[1] finan przeds 11 analiza wskaz

11 Siłowniki

11 BIOCHEMIA horyzontalny transfer genów

PKM NOWY W T II 11

wyklad 11

R1 11

CALC1 L 11 12 Differenial Equations

Prezentacje, Spostrzeganie ludzi 27 11

zaaw wyk ad5a 11 12

budzet ue 11 12

EP(11)

W 11 Leki działające pobudzająco na ośrodkowy układ

więcej podobnych podstron