63

Between the development of upright posture

and the emergence of the promenade, four mil-

lion years passed, a period reaching from the

Miocene epoch to the Enlightenment. One of

the chief works of the latter age was the Ency-

clopédie, which Diderot and d´Alembert began

to edit and publish in Paris in 1751. In arriving

at a definition of “promenade”, the dictionary

distinguishes between a garden or town element

and perambulation. The German translation of

promenade reflects this differentiation between a

permanent installation and the fleeting character

of movement with the words Spazierweg (path)

and Spaziergang (walk, as in going for a walk).

Walking is a time-honoured occupation that still

enjoys much popularity today, and the more man

has been able to liberate himself from the strug-

gle for survival, the more devotees it has found.

Walking is more of a matter of leisure than sim-

ply having time. Most of the Platonic dialogues

were conducted while strolling about; the Sun-

day walk is a further case in hand, and walking

with a friend can be tantamount to having a

good conversation. Nevertheless, the institution

of going for a walk was only one of the things

that led to the development of the promenade.

An open space, a tree-lined street or an avenue of

trees is not necessarily a promenade, and going

for a walk is not necessarily the same as ambling

down a promenade. The 18th century German

novelist Johann Gottfried Seume journeyed to

Syracuse on foot (as he related in a three-volume

account), whereas his contemporary Casanova

was given to strolling about in the Jardins des

Tuileries in Paris. In contrast to making a journey

on foot, promenading has less to do with seeing

the countryside and communing with nature,

Von der Entwicklung zum aufrechten Gang bis zur Erfindung der Pro-

menade brauchte es vier Millionen Jahre, vom Miozän bis immerhin zur

Aufklärung. Deren Zentralorgan, die Encyclopédie, von Diderot und

d´Alembert ab 1751 in Paris herausgegeben, trifft unter dem Stichwort

»Promenade« eine kluge Unterscheidung: 1. Promenade als gärtnerische

und städtebauliche Anlage und 2. Form der Fortbewegung. In der deut-

schen Übersetzung wird diese feine Unterscheidung von dauerhafter Anla-

ge und flüchtiger, vorübergehender Bewegung als einerseits Spazierweg und

andererseits Spaziergang nachvollzogen. Der Spaziergang ist eine von alters

her überlieferte, bis heute populäre Gangart, die mehr Anhänger fand, je

mehr sich der Mensch von den drückenden Lasten der Daseinsbewältigung

befreien konnte. Mit der Muße hat der Spaziergang mehr zu tun als mit

dem Müßiggang. Kaum ein platonischer Dialog kommt ohne ihn aus, vom

Sonntagsspaziergang können wir ein Lied singen. Beim gemächlichen Ge-

hen im Grünen kommt man gut ins Gespräch. Der Spaziergang ist aber nur

ein Vorläufer der Promenade, Weggeselle bis zu jener Biegung der Ent-

wicklung, wo sich die Wege trennten. Wie ein öffentlicher Platz, eine

baumgeschmückte Straße noch längst keine Promenade macht, so wenig

wird ein jeder Spaziergang gleich als Promenade gelten. Seume spaziert

nach Syrakus, während Casanova in den Jardins des Tuileries promeniert.

Im Unterschied zum Spaziergang geht es auf den Promenaden auch nicht

in erster Linie um ein landschaftliches Erlebnis oder den Naturgenuss, es

geht auch weniger um Erholung und Erbauung, sondern um Kommunika-

tion und Konversation, um Zerstreuung und Erlebnis. Von daher rückt der

Jahrmarkt als ein weiterer Vorläufer in den Blick. Die Promenade vermittelt

weit weniger als der Volkspark des 19. Jahrhunderts ein Naturerlebnis in der

Stadt. Sie ist vielmehr Bühne für die Selbstinszenierung der neuen tonan-

gebenden Bürgerschicht und von daher, wie Fred E. Schrader festhält, dem

Vergnügungspark, dem jardin spectacle näher.

Was die öffentliche Promenade im 18. Jahr-

hundert zur Attraktion macht, was sie überhaupt

erst zu einem Fall der Kulturgeschichte qualifi-

ziert, soll hier als Ausgangsfrage dienen. Ein Blick

zurück zu den Anfängen ihrer Erfolgsgeschichte

bietet nämlich allerhand Aufschluss über die Er-

folgsbedingungen heutiger Promenaden: Wo

auch immer neue geplant und gebaut werden,

Zur Lust der Einwohner

For the pleasure of the people

Carl Friedrich Schröer

Die Pariser Promenaden des 18. Jahrhunderts

waren das Gegenmodell zum königlichen Ver-

sailles, Bühne für die bürgerliche Klasse.

The Parisian promenades of the 18th century

flouted Versailles by providing the new bour-

geois classes with a forum for emancipation.

ihre Akzeptanz seitens der heutigen Promeneurs hängt von einer Reihe von

Bedingungen ab, die alle bedeutenden Beispiele zumindest eine Zeit lang er-

füllt haben. Vor allem: Es sind weit weniger die gartenkünstlerischen Ge-

staltungsfragen, als vielmehr die konkrete soziale und politische Situation, in

die hinein sie wirken, die für ihren Zulauf ausschlaggebend ist. Innerhalb der

bald ausufernden Großstädte konnten diese besonderen gärtnerischen Anla-

gen ihre Bedeutung, vor allem als soziale Einrichtungen, gewinnen: Die Be-

gegnung der Bevölkerung über Standesgrenzen hinweg, der freie Meinungs-

austausch über alle erdenklichen Themen, die Konversation mit Zugereisten

und Fremden außerhalb des Zugriffs der Zensur wurde innerhalb der Pro-

menades Publiques möglich. Sie wurden zum ersten großen Forum für eine

moderne Errungenschaft: die öffentliche Meinung. Ihr Durchbruch zur be-

stimmenden politischen Größe im vorrevolutionären Frankreich – wie auch

bald in ganz Europa – sollte sich auf den neuen Promenaden ereignen. Denn

sie wurden zum bevorzugten Ort der Zeitungslektüre. An den bewachten

Eingängen zu den Tuilerien, dem Palais Royal oder dem Cours-la-Reine ver-

kaufte die Schweizer Garde nicht nur Limonade und Sandwiches, sondern

auch erste Tageszeitungen, die man sich des hohen Preises wegen zu Dritt

and with recreation and edification, than with

communication, amusement, conversation and

entertainment. This explains why fairs can be re-

garded as a precursor of the promenade. Prome-

nades were not places intended for the enjoy-

ment of nature, as in the case of the 19th-centu-

ry Volksgarten, but came about because they pro-

vided the new trend-setting bourgeois classes

with a place to see and be seen. In this respect, as

Fred E. Schrader has pointed out, promenades

fulfilled something of the function of a leisure

park, un jardin spectacle.

What was it that made the promenades

publiques such an attraction in the 18th century?

In what way do they contribute to cultural histo-

ry? This is a fundamental question. A look back

at the early days of the success story of the prom-

enade is revealing in that it indicate which prere-

quisites today’s promenades need to fulfil to be a

success. No matter where they are built, the

acceptance of promenades always depends on a

number of conditions, conditions that all impor-

tant examples fulfilled for a time at least. First

and foremost, these concern the prevailing social

and political situation and not so much garden

design. Promenades became important in the

teeming cities of the 18th century for social rea-

sons since they enabled encounter between peo-

ple of differing rank and station, a free exchange

of opinion on all conceivable topics, and conver-

sation with strangers and newcomers beyond the

reach of the supervisors of conduct and morals.

They provided public opinion – a modern phe-

nomenon – its first major forum. The break-

through of public opinion as a determining po-

litical factor in pre-Revolutionary France – and

soon after throughout the whole of Europe – was

64

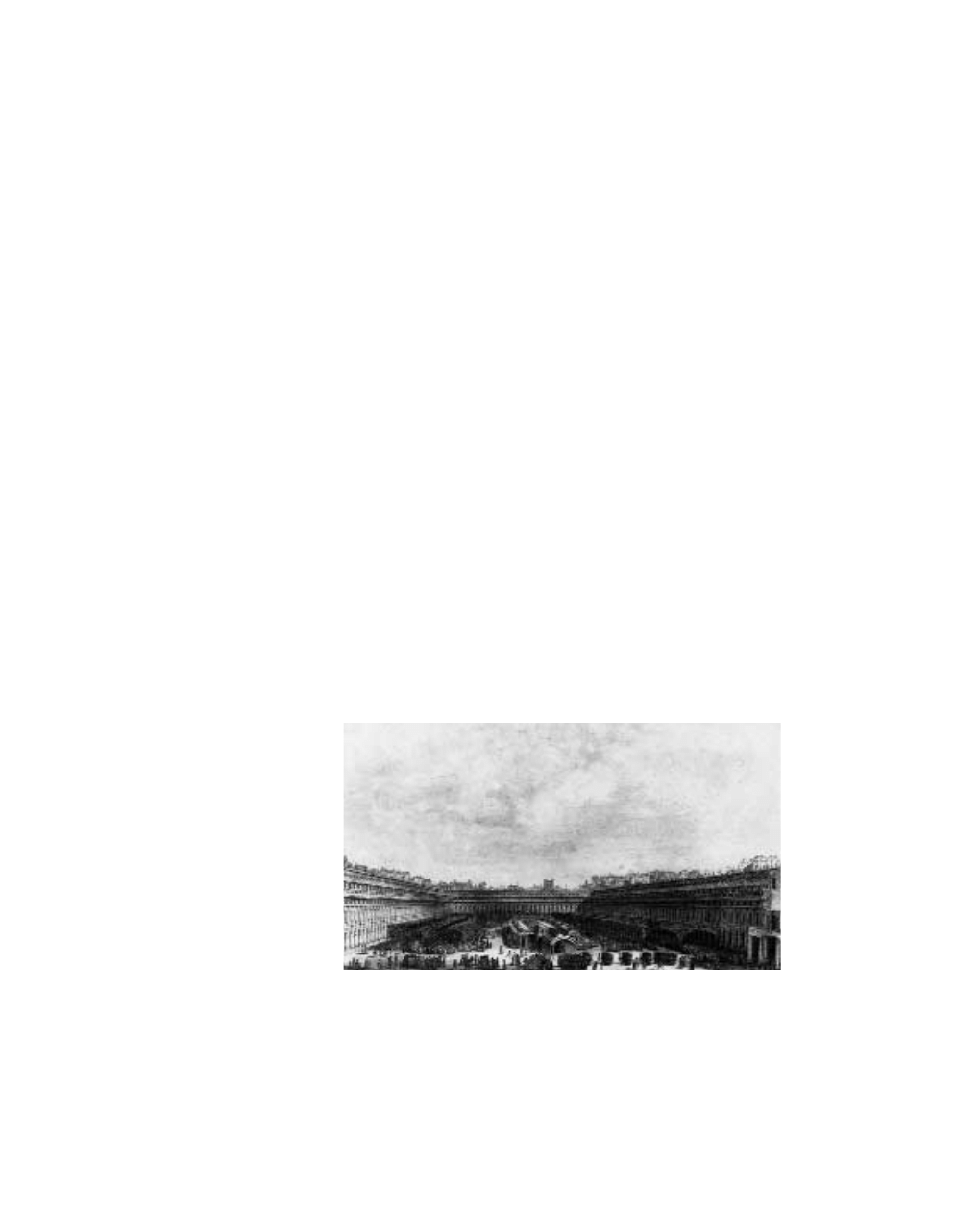

Das Palais Royal wurde nach

seinem Umbau 1780 zur be-

liebtesten Pariser Promenade.

In der neuen klassizistischen

Anlage mit dem adeligen Na-

men brach sich eine friedliche

Revolution Bahn: eine sponta-

ne, unentwegte Party der neu-

en tragenden Schichten am

Vorabend der Revolution.

After its conversion in 1780,

the former garden at the

Palais Royal became the most

popular promenade in Paris.

On the eve of the Revolution,

the formal gardens with the

aristocratic name became the

scene of an incessant celebra-

tion of freedom on the part of

the bourgeois classes.

65

enabled in part by the new promenades. More-

over, they were also a favourite place for reading

newspapers. The Swiss Guard soldiers guarding

the entrances to the Tuileries, the Palais Royal or

the Cours-la-Reine sold not only lemonade and

sandwiches but also the first broadsheets, which

being expensive, were bought collectively and

read out loud straight away. This symbiotic rela-

tionship with the public promenades fostered the

rise of the gazettes quite considerably.

It was this particular historical circumstance

that determined the popularity of promenades

and later led to their decline. The 18th century

was an age of radical change, of revolution and

restoration, a time primarily characterised by the

rise of common man. Sweeping away standards of

conduct that been unchallenged for centuries, a

social upheaval took place at inconceivable speed

and with undreamed-of consequences, neglecting

to replace the old class system, in which every es-

tate had its allotted place, with new and equally

binding structures. It was only in such a phase

that the promenade could become an emancipa-

tory element of a society fraying at the seams.

Questions of taste, such as garden design, were

only relevant to the extent that they expressed po-

litical doctrines. Discussions of fashions, garden

styles and moral dictates turned into debates

about what these things stood for in the crisis-rid-

den political reality of the day. This brings the

flourishing salon culture of the epoch to mind,

and indeed, the salon and the promenade were

twin phenomena within the prevailing atmos-

phere of repression. Astonished travellers to Paris

spoke of the promenades as “green living rooms”.

The heyday of the promenade. The invention of

the promenade came from France, from 18th-

oder Viert teilte und laut vorgelesen wurden. Die Journale entwickelten sich

in symbiotischer Beziehung zu den Promenaden außerordentlich prächtig.

Es ist der besondere zeitgeschichtliche Hintergrund, vor dem die Pro-

menade ihre großen Auftritte feiert, er bedingt und befördert sie und lässt sie

auch wieder entbehrlich werden. Es ist eine Zeit des Umbruchs, der wieder-

holten Revolutionen und Restaurationen, die vor allem durch den Aufstieg

eines Standes charakterisiert wird: des Bürgers. Ein gesellschaftlicher Um-

bruch von nicht gekannten Auswirkungen und unvorstellbarer Geschwin-

digkeit setzte über Jahrhunderte unangefochtene gesellschaftliche Regeln in-

nerhalb weniger Jahrzehnte außer Kraft, ohne jedoch an die Stelle der alten

Ordnung, die jedem Stand einen im Prinzip gesicherten Platz zuwies, neue,

ebenso verbindliche Strukturen zu setzen. In dieser Phase konnte die Pro-

menade zu einem emanzipatorischen Element einer geschlossenen Gesell-

schaft im Aufbruch werden. Geschmacksfragen, etwa solche nach dem Stil

der gärtnerischen Gestaltung, wurden nur insoweit relevant, als sich mit der

jeweiligen Gartenmode bestimmte politische Glaubenssätze verbinden

ließen. Die Diskussion um den Guten Geschmack, Gartenstile und morali-

sche Gebote wurde zur Debatte über symbolische Formen innerhalb einer

krisenhaften politischen Wirklichkeit. Es liegt nahe, an die aufblühende Sa-

lonkultur der Epoche zu denken, und tatsächlich erscheinen Salon und Pro-

menade als Zwillinge in einer repressiven Kultur. Reisende in Paris sprechen

erstaunt von den neuen Promenaden als den »grünen Wohnzimmern«.

In 1780, Duke Louis-Philippe

d'Orléans decided to embark

on a daring piece of property

speculation to overcome a pri-

vate financial crisis. His solu-

tion: Erection of tenement

houses complete with arcades

on three sides of the garden

behind his town palais, the

Palais Royal. The central area

took on the form of a formal

garden inspired by the colon-

nades of classical antiquity.

Weil er seine Schulden nicht

bezahlen konnte, entschloss

sich Louis-Philippe d‘Orleans

zu einer gewagten Immobilien-

spekulation: An drei Seiten des

Gartens hinter seinem Stadt-

palais, dem Palais Royal, ließ

er ab 1780 Miethäuser mit ei-

nem Arkadengeschoss bauen.

Der Platz in der Mitte wurde

zu einem architektonischen

Garten, in Anlehnung an anti-

ke Wandelgänge.

Hohe Zeit der Promenade. Die Erfindung kommt aus Frankreich, ge-

nauer aus dem Paris des 18. Jahrhunderts, das mit einiger Berechtigung als

»Hauptstadt des Luxus und der Moden« gelten konnte. In Paris trafen un-

gleich günstige Voraussetzungen zusammen, die für die Entstehung der

Promenade entscheidend werden sollten: eine reiche Gartentradition, eine

rasant wachsende Stadtbevölkerung und eine fundamentale Krise der Mon-

archie, die sich zum revolutionären Umbruch der politischen Verhältnisse

in Europa ausweitete. Paris hatte beim Ausbruch der Revolution 640 000

bis 670 000 Einwohner. In der damals nach London zweitgrößten Stadt

Europas lassen sich exemplarisch Aufstieg und Niedergang der Promenade

studieren. Von der Öffnung der königlichen Gärten des Chateau des Tui-

leries und des Palais du Luxembourg in der Zeit nach dem Tod Ludwig

XIV. (1715) über die Erweiterung der Champs-Elysées und der nördlichen

Boulevards bis zur Anlage des Parc des Buttes-Chaumont als Arbeiterpark

gegen Ende des Second Empire – die Einweihung fiel mit der Eröffnung

der Pariser Weltausstellung am 1. April 1867 zusammen – lässt sich die ge-

samte Spannweite der neuen öffentlichen Promenaden aufzeigen.

Promenadenmischling – das Palais Royal. Der rasche Aufstieg der Prome-

nade zu einem Phänotyp der Epoche kennt zudem einen unbestrittenen

Star: das Palais Royal. Eine absolute Neuheit, geboren aus der Laune der

Zeit. Hier kommt alles zusammen, ein einzigartiges, völlig neues Amalgam,

von dem nicht sicher zu sagen ist, was es mehr ist, Platz, Garten, Galerie,

Spielsalon, Kauf- oder Freudenhaus. Aber wieso Promenade? Im Vergleich

zu den anderen Promenaden, war sie sogar ausgesprochen klein; entspre-

chend groß war das Geschiebe und Gedränge bis in die Nacht, was sie um-

somehr zur ersten Attraktion von Paris werden ließ. Obwohl die neue Anla-

ge niemals offiziell so genannt wurde, steht sie doch unerreicht als Prototyp

aller späteren Promenaden da. Hier zeigt sich die Überlegenheit der Prome-

neurs über die Architekten und Städtebauer. Die massenhafte Handlung

entschied über die bauliche Fassung. Zur Promenade wurde das neue Palais

Royal, weil die Pariser es für ihre Lieblingsbeschäftigung in Besitz nahmen,

nicht aber weil die Investoren oder Planer eine beispielhafte Promenade an-

zulegen gedachten. Um seine private Finanzkrise zu bewältigen, entschloss

sich Herzog Louis-Philippe von Orléans 1780 zu einer gewagten Immobili-

enspekulation ganz nach Art der aufstrebenden Finanzbürger. Zu drei Seiten

des Gartens hinter seinem noblen Stadtpalais ließ er Mietshäuser mit uni-

formen Fassaden errichten. Der schönste Hinterhof von Paris war entstan-

century Paris to be precise, which was regarded

with all due justification as the “capital of luxury

and fashion.” Paris brought together the right cir-

cumstances for the emergence of the promenades:

a rich garden tradition, a population growing at a

breakneck pace, and a fundamental monarchical

crisis that ultimately caused a revolutionary

change in political conditions all over Europe.

When the French Revolution broke out in

1789, between 640,000 and 670,000 people were

living in Paris, making it the second-largest city in

Europe after London. It witnessed all the stages in

the rise and fall of the new public promenade,

such as the opening of the royal gardens at the

Tuileries and the Palais du Luxembourg after

Louis XIV died in 1715, the enlargement of the

Champs-Elysées and the northern boulevards, and

the inauguration towards the end of the Second

Empire of the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont as a

workers’ park in April 1867, on the same day that

the Exposition Universelle was opened.

The Palais Royal. The Palais Royal is the un-

contested star in the swift rise of the promenades

as an expression of the era that brought them

about. Unheard-of before as a public place, the

Palais Royal was born of the mood of the times, a

completely new amalgam that united various ele-

ments in such a way that it is impossible to say

whether it was an open space, a garden, a gallery,

a casino, a trading floor or a bawdy-house. And

why was it called a promenade at all? In compari-

son to others, it was extremely short, but that was

the whole point: the pushing and shoving that

went on until deep into the night was what it

made it the foremost attraction of Paris. Although

never officially called a promenade, the Palais

Royal holds an unsurpassed place as the prototype

66

67

of all the promenades that followed. It was the

promeneurs who determined it rather than archi-

tects and town planners, its limits decided by the

masses that congregated its spaces. The Palais

Royal became a promenade because the Parisians

took possession of it as a place to pursue their

favourite pastime, and not because investors or

planners decided to create the ideal esplanade.

The promenade at the Palais Royal goes back

to Duke Louis-Philippe d’Orléans, who in order

to overcome a private financial crisis decided to

embark on a daring piece of property speculation

in the style of the rising financial bourgeoisie.

This involved having three tenement houses with

uniform facades erected on the three sides of the

garden behind his smart town palais. The result

was the most beautiful back yard in Paris. Ar-

cades were built against the buildings surroun-

ding the rectangular yard, and filled with coffee-

houses, bookshops, gaming houses and theatres

as well as shops and boutiques. The entire

amusement area took St. Mark’s Square in Venice

as its inspiration, but in contrast was not paved

but laid out like a formal garden, complete with

areas of grass, rows of topiary, and ponds. The

reading cabinet at the centre of the large avenue

was always thronged with people, and the “arbre

de cracovie” pavilion was the daily meeting-place

of novellistes and all others interested in politics.

Being the private property of the regent to the

crown, the Palais Royal grounds were relatively

safe from state guardians of opinion, and conse-

quently became the favourite open space of the

Parisian people in the years before the revolution.

Parisian nobility and bourgeois citizens excluded

from the power that emanated from Versailles

made the Palais Royal an imposing setting for the

den. Das Erdgeschoss des längsgestreckten Hofes wurde zu drei Seiten als Ar-

kadengang ausgebaut. In diesen Galerien etablierten sich ringsum Ge-

schäftslokale, Boutiquen, zahlreiche Caféhäuser und Restaurants, Buchlä-

den und Spielsalons hielten ebenso Einzug wie Theater und die Oper. Zum

Vorbild der neuen Pariser Anlage diente der Markusplatz in Venedig, doch

wurde der freie Raum hier nicht gepflastert, sondern nach dem Muster for-

maler Gärten mit Rasenflächen, Baumreihen in Formschnitt und Wasser-

bassins angelegt. Das Lesekabinett in der Mitte der großen Allee wurde zum

umlagerten Zentrum. Der arbre de cracovie genannte Pavillon wurde zum

tägliche Treffpunkt der Novellistes und aller politisch Interessierten. Als pri-

vate Anlage des Regenten war er vor polizeilichem Zugriff und Zensur rela-

tiv geschützt. So konnte die neue Promenade in den Jahren vor Ausbruch der

Revolution zum bevorzugten öffentlichen Raum der Pariser Bevölkerung

werden. Städtischer Adel wie Bourgeoisie, weitgehend von der Macht und

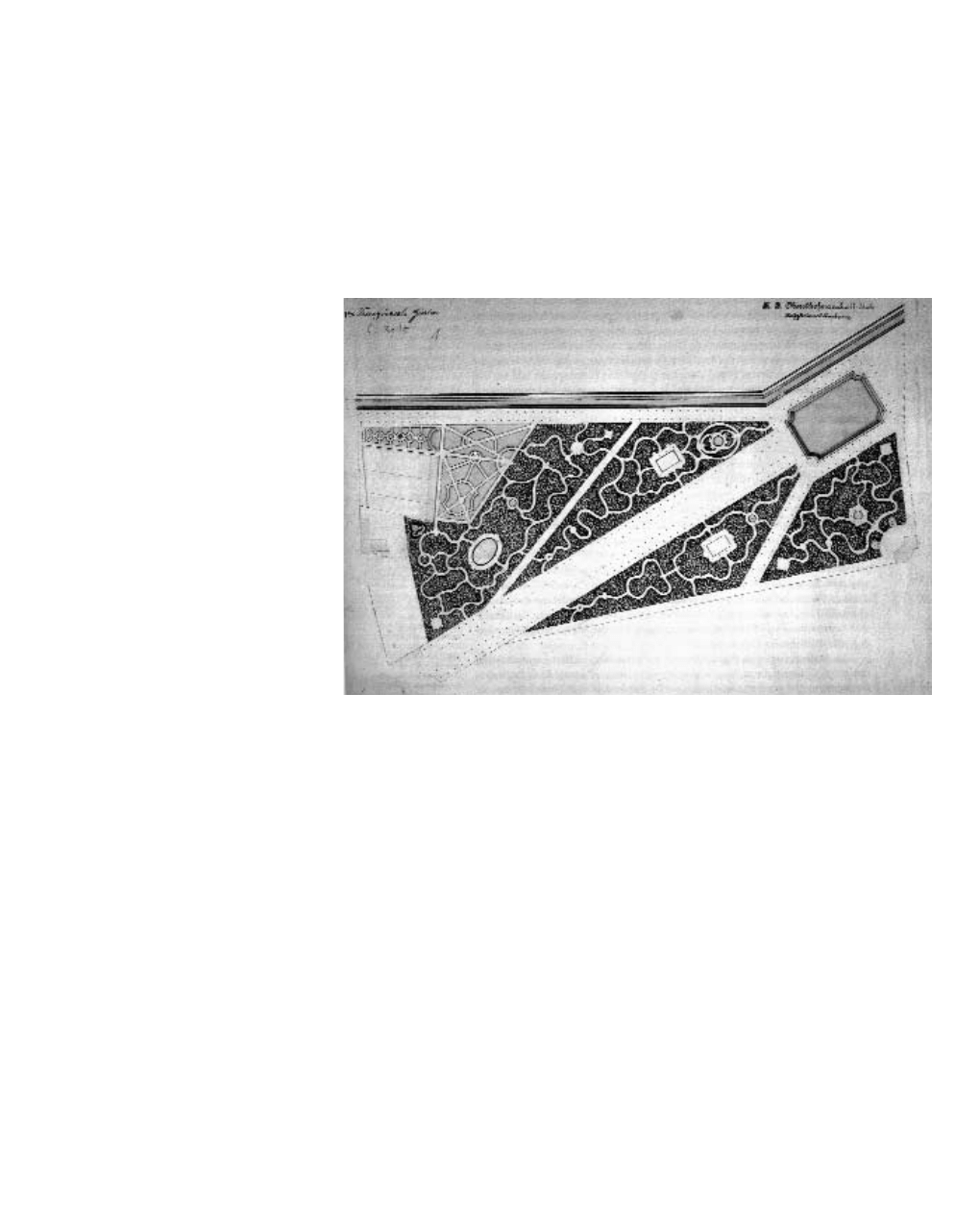

In 1769, the elector palatine

Carl Theodor commissioned

his court architect, Nicolas des

Pigage (1723-1796), to cre-

ate a promenade “for the peo-

ple’s pleasure” between Jäger-

hof castle and the ramparts of

Düsseldorf’s fortifications. Fol-

lowing the “Jardin public” in

Bordeaux (1746), it was the

first to be created outside

France for the entertainment

of the urban population.

Nicolas des Pigage (1723-

1796), Hofarchitekt des Kur-

fürsten Carl Theodor zu Pfalz,

erhielt 1769 den Auftrag, »Zur

Lust der Einwohnerschaft«

einen Spazierweg zwischen

Schloss Jägerhof und den

Glacis der Festung Düsseldorf

anzulegen. Nach dem »Jardin

public« in Bordeaux von 1746

wurde er zur ersten öffentli-

chen Promenade außerhalb

Frankreichs.

dem Machtzentrum in Versailles ausgeschlossen, erkoren das Palais Royal

zur imposanten Kulisse für ihre tägliche Demonstration. Man pflegte einen

freien, bald zügellosen Lebensstil. »Libertinage« laute die Losung der Epo-

che, »l´esprit vagabonde«. Die Promenade wurde zum Probesaal im Freien,

geprobt wurde eine neue Macht der Öffentlichkeit. Das Palais Royal wurde

seinem königlichen Namen ganz entgegen schnell zu einem Club en plein

air, ja zum »Garten der Revolution« als am 13. Juli 1789 Camille Desmou-

lins vor dem Café Foy Cocaden aus Kastanienblättern ans vorbeiströmende

Volk verteilte und zum bewaffneten Kampf aufrief.

Die Entwicklung in Deutschland. »Zur Lust der Einwohnerschaft«, lässt

der aufgeklärt-barocke Kurfürst Carl Theodor 1769 eine öffentliche Prome-

nade in Düsseldorf anlegen. Es wird die erste, eigens zur Lustbarkeit der Be-

völkerung geschaffene Anlage außerhalb Frankreichs. Beim Düsseldorfer

Hofgarten handelt es sich um eine öffentliche Grünanlage, die von einem

System von Alleen geschickt gegliedert wird. Ein Caféhaus fehlte hier eben-

sowenig wie intimere »Grüne Kabinette« zum freien Meinungsaustausch.

Der Französische Einfluss bleibt evident, zumal der bestellte Architekt der

neuen Promenade, Nicolas de Pigage, Eleve der berühmten königlichen Ar-

chitekturakademie in Paris ist. Der neue Spazierweg, kaum einen Kilometer

daily demonstration of a free lifestyle that be-

came increasingly dissolute as time went past.

“L’esprit vagabonde” and libertinage were the

watchwords of the moment, making the prome-

nade an open air rehearsal space for a piece de-

voted to the new-found power of the public.

Contrary to its name, the Palais Royal soon be-

came a club en plein air, and by July 13, 1789, the

day on which Camille Desmoulins distributed

chestnut-leaf cockades at Café Foy, calling on

passers-by to take up arms, it had truly become a

“garden of revolution”, a garden of the revolution

that broke out the very next day.

The development of the promenade in Germany.

In 1769, the enlightened baroque elector Carl

Theodor had a public promenade made in Düs-

seldorf “for the people’s pleasure”. The first of its

kind to be created outside France for the enter-

tainment of the urban population, it was laid out

at the Hofgarten and consisted of a park-like

space ingeniously articulated by a system of

straight avenues of trees. Features included a cof-

feehouse and an intimate “Green Cabinet” for

free exchanges of opinion. The French influence

was evident, particularly as Nicolas de Pigage, the

architect commissioned with the creation of the

new promenade, was a student of the famous roy-

al academy of architecture in Paris. A further pur-

pose of the new walkway, which was barely one

kilometre in length, was to serve the “embellish-

ment and prestige” of the former residence city

and contribute to its general improvement. This

included new squares, a comedy house and the

Carlstadt suburb, which was laid out on a regular

gridiron plan, a fairly new departure for the times.

Not only the promenade idea but also this embel-

lissement des villes programme had crossed the

68

Sechs Reihen Linden schmück-

ten ab1647 den Reitweg vom

Berliner Stadtschloss zum

Jagdrevier Thiergarten. Bereits

im 17. Jahrhundert wurde die

Grünanlage partiell und mit

strengen Auflagen für die Ber-

liner Bevölkerung geöffnet.

In Berlin, the bridle path from

the City Palace to the hunting

grounds in the “Thiergarten”

was embellished with six rows

of lime trees in 1647. Part of

the Tiergarten was made ac-

cessible to a strictly regiment-

ed public soon after.

69

Rhine from France to Germany. Twenty years af-

ter building the Düsseldorf promenade, Carl

Theodor went on to commission a more ambi-

tious public promenade, namely the Englische

Garten in Munich. Although the year was the one

that saw the outbreak of the French revolution,

the elector’s motive was to encourage “trusting

and convivial dealings and rapprochement be-

tween the classes … in the lap of beautiful nature”

– an approach that saw the promenade as a means

of promoting peace. To this day, the Englische

Garten remains the most exemplary popular park

in Germany. But mistrust of a public able to mix

and mingle in the new garden on the edge of the

city soon began to make itself felt. Even the gar-

den design theorist Christian C.L. Hirschfeld,

who open-mindedly championed the populistic

Volksgarten idea, called for “open spaces and

straight avenues” to facilitate the “police supervi-

sion that is often indispensable at such places.”

In Berlin, the royal zoological gardens had

been made accessible to a strictly regimented pub-

lic in 1740 (while the other royal parks remained

reserved for the court). Meanwhile, the former

hunting grounds at the Prater in Vienna had been

open to use by the nobility and distinguished

society since the 16th century, and were later

opened to all and sundry, as proclaimed in an

avertissement issued by emperor Joseph II in 1766

which stated: “all people without distinction can

walk freely within the Prater ...”. Yet all this throw-

ing open of royal gardens and razing of city walls

and fortifications was accompanied by a fear of the

new public. Despite the growing enthusiasm for

the new landscape gardens in the cities, the pro-

menade idea began to lose appeal, and the liberty

that was the ideal of the age became a closely

lang, soll überdies zur »Verschönerung und Ansehen« der ehemaligen Resi-

denzstadt dienen und ist somit Bestandteil einer umfassenden Stadtverschö-

nerung. Neue Plätze, ein Comödienhaus, wie die regelmäßige Carlstadt

gehören dazu. Auch dieses Programm, das embellissement des villes, war aus

Frankreich über den Rhein gekommen. Zwanzig Jahre nach der Düsseldor-

fer Promenade gibt Carl Theodor in München mit dem Englischen Garten

eine bedeutend größere öffentliche Promenade in Auftrag. Im Jahr des Aus-

bruchs der Revolution hofft der Kurfürst durch eine öffentliche Grünanlage

»zum traulichen und geselligen Umgang und Annäherung aller Stände ... im

Schoße der schönen Natur« anhalten zu können – die Promenade als frie-

densstiftende Maßnahme. Es ist bis heute der beispielgebende öffentliche

Garten in Deutschland geblieben. Das Misstrauen gegen eine sich frei gesel-

lende Öffentlichkeit in den neuen Anlagen vor der Stadt wird schon früh

Already equipped with the

18th-century Hofgarten prom-

enade and the Königsallee

shopping street created in the

early 19th century, Düsseldorf

decided to build itself a prom-

enade along the river Rhine in

the nineties. Cars rush through

two tunnels in the lower level,

while the upper level is

thronged by promeneurs until

deep in the night.

Im Rheinbogen gönnte sich

Düsseldorf nach der Hofgar-

tenpromenade aus dem 18.

Jahrhundert und der Königsal-

lee aus dem frühen 19. Jahr-

hundert eine dritte öffentliche

Promenade: die 1993 einge-

weihte Rheinuferpromenade.

Unten rauscht der Autoverkehr

durch zwei Tunnelröhren. Oben

tummeln sich die Promeneurs

bis in die Nacht hinein.

spürbar. Wie aufgeschlossen der Gartencheftheoretiker Christian C.L.

Hirschfeld den »Volksgarten« auch propagiert, so mahnt er doch »offene

Plätze und gerade Alleen« an, um »die Aufsicht der Polizey, die an solchen

Plätzen oft unentbehrlich ist« zu erleichtern. In Berlin wurde der königliche

Tiergarten seit 1740 einer streng reglementierten Öffentlichkeit zugänglich

gemacht, während die anderen Schlossparks weiter dem Hof vorbehalten

bleiben. In Wien war der Prater seit dem 16. Jahrhundert den Adligen und

Distinguierten zugänglich. Ein »Avertissement« Josephs II. von 1766 öffne-

te ihn dann so, dass »ohne Unterschied jedermann in den Bratter sowohl als

auch in das Stadtgut frey spazieren gehen« konnte. Mit der Öffnung der

fürstlichen Tierparks und Gärten, mit der Schleifung der Wälle und Entfe-

stigung der Städte macht sich auch die Angst vor der neuen Offenheit breit.

Bei aller anhaltenden Begeisterung für die neuen Landschaftsgärten in den

Städten, verflüchtigte sich die Idee der Promenade: Aus der ersehnten Frei-

heit wurde praktizierte Freizeit. Die neuen Freiflächen wurden zu »Tugend-

gärten«, Bildungsanstalten im Grünen zur Erziehung neuer Untertanen. Ein

strenger Sittenkodex hielt Einzug auf den Promenaden und die Gedanken-

polizei war wieder unterwegs.

Renaissance der Promenade? Schön wär’s. Wenn das nicht bloß Garten-

denkmalpflege heißt. Sie kann bestenfalls die Anlage schützen und rekon-

struieren. Doch für eine neue Belebung, eine neue soziale Funktion der alten

Promenaden wird ihre Kraft kaum reichen. Wo um die Reste einer »zivilen

Gesellschaft« gerungen wird, werden sich die Promenaden eines nostalgi-

schen Erinnerungswertes erfreuen. Und wo Freizeit mit Konsumglück in den

Arenen der event cities eingetauscht wird, werden sich neue Vergnügungs-

parks auftun. Eine moderne Stadtentwicklung aus dem Geist der Garten-

kunst ist nicht zu erwarten, solange die Planer den sozialen Bedürfnisse der

heutigen Promeneurs nach einer neuen Öffentlichkeit nicht entsprechen.

Ausgerechnet im promenadenstolzen Düsseldorf zeigt sich in schöner

Deutlichkeit der flüchtige Reiz der Promenaden. Die Königsallee mit ihren

feinen Geschäften und teuren Cafés lief schon bald der Hofgartenpromena-

de den Rang ab. Längst hat man unter Denkmalschutz gestellt, was übrig ge-

blieben ist vom einstigen Treffpunkt »der vornehmen Welt«. Heute fristet die

Hofgartenpromenade ein Schattendasein als städtische Grünanlage. Prome-

nade außer Betrieb. Außer Reichweite der Denkmalpflege die Hauptattrak-

tion: die Promeneurs von heute. Sie tummeln sich lieber auf der neuen, 1993

eröffneten Rheinuferpromenade. Promenade ist, wo die Leute hingehen.

watched and reglemented freedom. The new open

spaces became “gardens of virtue”, open-air estab-

lishments with the purpose of educating the sub-

jects of the realm. The promenades were suddenly

subject to a strict code of conduct, and the people

who used them had to watch what they said.

Renaissance of the promenade? If only this was

the case, and certainly not if it entails preservation

as a listed property. This kind of approach might

protect promenades and possibly even re-create

them, but would hardly be powerful enough to

instigate their resurrection or provide them with

new social functions. Wherever efforts are made

to preserve the remnants of “civil society”, prom-

enades will undoubtedly enjoy a nostalgic rebirth

for old times’ sake, and it is also possible that new

leisure parks will come about at places where

leisure counts for more than events and material

values. Nevertheless, as long as planners do not

meet the needs of today’s promeneurs, it is un-

likely that a form of town development based on

the spirit of garden design – complete with its

promenades – will come about.

Of all places it is Düsseldorf, the city that saw

the birth of the promenade in Germany, that

demonstrates that the popularity of a promenade

is a fleeting matter. Königsallee, a street lined with

exclusive shops and expensive cafés, has long out-

flanked the Hofgarten as a place to see and be

seen. The former meeting-place of “distinguished

society” now leads a shadowy existence as a listed

public gardens and is no longer used as a prome-

nade. Today, the promeneurs prefer to throng the

new Uferpromenade alongside the river Rhine,

beyond the reach of the authorities whose job it is

to preserve monuments. Only when people flock

to a promenade can it claim to be such.

70

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

WINDSOR FOR THE DERBY Empathy for People Uknown (remix)Gunboats 12 (Secretly Canadian) SC136sc136

Burda Style For people who sew

Coping a survival guide for people with Marc Segar

Self Help For people With Cancer v1 1

A Survival Guide For People With Asperger Syndrome (Marc Segar, 1997)

An Introduction to USA 1 The Land and People

The Pleasure Garden (1925)

Bangs, Nina The Pleasure Master

All the Pleasures Prove(1)

Blade Ashley The Pleasure Club The Dom

The Ten O Clock People

Anne Mather The Pleasure and the Pain [HP 4, MBS 403, MB 546] (docx)

Sport brings out the best and the worst in people

Outcome list of President Xi Jinping s state visit to the United States People s Daily Online

In the Navy Village People tekst

the pleasure slave gena showalter read online

Feynman Transcript The Pleasure Of Finding Things Out

the good country people summary and analisisdocx

więcej podobnych podstron