Introduction to Scholastic Ontology

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/introsch.htm

1 of 4

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

Introduction to Scholastic Ontology

I. Constituent Ontology

A constituent ontology, as I am conceiving of it, aims at a general characterization

of substances in terms of various types of constituents which are in some

straightforward sense intrinsic to them and compatible with their status as unified

wholes. Scholastic ontology is in this broad sense a constituent ontology.

Now every plausible ontology of material substances must acknowledge that such

substances have material constituents or parts and can thus be characterized as

composite in that sense. However, scholastic ontology sees the natures (or

essences) of such substances, as well as their characteristics (or accidents), as

individuals intrinsic to those substances and capable of existing only within

singular substances. The natures of such substances constitute them as entities of a

given natural kind, whereas their accidents (both those that emanate directly from

the natures and those that are peculiar to particular substances within a given

natural kind) are related to them by the 'transcendental' relation of inherence.

A non-constituent ontology, by contrast, aims at a general characterization of

substances in terms of their relations to entities (e.g., Platonistically conceived

universals or properties, including abstract essences and natures) that have their

being and reality independently of those substances. These natures and

characteristics of substances are in some obvious way extrinsic to them and linked

to them by the relation of exemplification or participation. On such a view all

individuals are in some sense lacking in intrinsic composition at any level other

than that of integral parts. At the very least, this sort of ontology does not think of

other sorts of composition as ontologically significant.

The recent literature on divine simplicity in analytic philosophy of religion

illustrates well how skewed matters become when those who work within a

non-constituent ontology try to address without adequate care or preparation

relevant aspects of scholastic metaphysics. For the scholastics were able to fashion

a substantive and metaphysically interesting account of the distinction between

God and creatures by characterizing God as wholly simple, i.e., wholly lacking in

the sorts of composition characteristic of creaturely substances. Thus, they

claimed, for instance, that in God there is no composition of form and matter, of

substance and accident, of esse and essentia, or of genus and difference. However,

each of these claims, if transformed without due care into the framework of

non-constituent ontology, leads to patent absurdities. (For an analysis of this

situation I recommend Nicholas Wolterstorff, "Divine Simplicity," Philosophical

Perspectives 5 (1991): 531-552.)

In what follows I will try to explain the motivations for the postulation of the

Introduction to Scholastic Ontology

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/introsch.htm

2 of 4

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

various types of constituents posited by mainline Aristotelian scholastic

metaphysicians.

II. Modes of Composition in Scholastic Ontology

A. Physical composition

The requirement of physical composition arises from the analysis of change.

Aristotle posited three principles of change, viz., privation, form, and matter. The

matter of a given change is that which perdures through the change and is

modified by the change, whereas the form is the terminus ad quem of the change

and the privation the terminus a quo of the change.

In cases of qualified or accidental change, this analysis requires that there be a

composition of substance and accident, where the substance is the matter of the

change and the accident which comes to modify the substance is the form. This

accident or accidental form is a reality (perfection, sort of being) that depends for

its existence on the existence of the substance in which it inheres. Such accidents

are usually taken to fall into categories along the lines suggested by Aristotle,

though among the later medievals there were heated debates about the status of

accidents. Ockham, for instance, saw Aristotle's categories as a classification of

terms rather than of entities and went on to argue that only certain terms in the

category of quality signify distinctive entities; Suarez and St. Thomas, grants a

type of reality to all accidents, though Suarez assigns some the status of modes,

which, unlike full-fledged accidents, are only "modally distinct" and not "really

distinct" from the substances in which they inhere. (A real distinction implies

separability at least by God's absolute power.) Modes are something like states of

substances and have less unity and independence than do, say, qualities. In any

case, the three basic types of accidental change are (i) alteration (change with

respect to quality), (ii) augmentation and diminution (change with respect to

quantity), and local motion (change with respect to place). All changes with

respect to other categories are reducible, i.e., able to be traced back, to these three.

But Aristotle insisted, apparently in keeping with common sense but contrary to

received philosophical wisdom, that at least some really real things (ousiai) could

themselves come into and pass out of existence through change. If such

unqualified or substantial change is possible, there must be within the relevant

substances (or individual natures) a composition of (primary) matter and

(substantial) form. So the same matter can successively be a constituent of

different substances and even of different kinds of substances. The types of

substantial change are generation and corruption. (A note on Empedocles,

Anaxagoras, and the atomists).

The form/matter and substance/accident distinctions can both be seen as

determinations of the more general distinction between act and potency, since in

each case what we have is a determinable "matter" (a potentiality) being

determined or actualized or brought to completion by a determinant "form" (an

actuality), which is the terminus of the change.

Introduction to Scholastic Ontology

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/introsch.htm

3 of 4

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

Aquinas's distinction between being (esse) and essence is yet another instance of

this general distinction between act and potency, one that is meant to

accommodate, contrary to received philosophical wisdom, the possibility of an

exercise of efficient causality that is not a modification of an existing matter or

substratum but is instead a creation ex nihilo of a substance with all its accidents

(essentia). In this case the notion of a principle of potentiality is stretched a bit,

since this principle does not exist prior to the exercise of efficient causality.

Nonetheless, Aquinas and his followers insist that the distinction between esse and

essence is a real distinction (in his sense of 'real distinction', which does not

involve separability) on a par with the distinctions between substance and accident

and between form and matter. (Suarez takes this distinction to be a conceptual

distinction with a foundation in reality, but this difference is not of present concern

to us.)

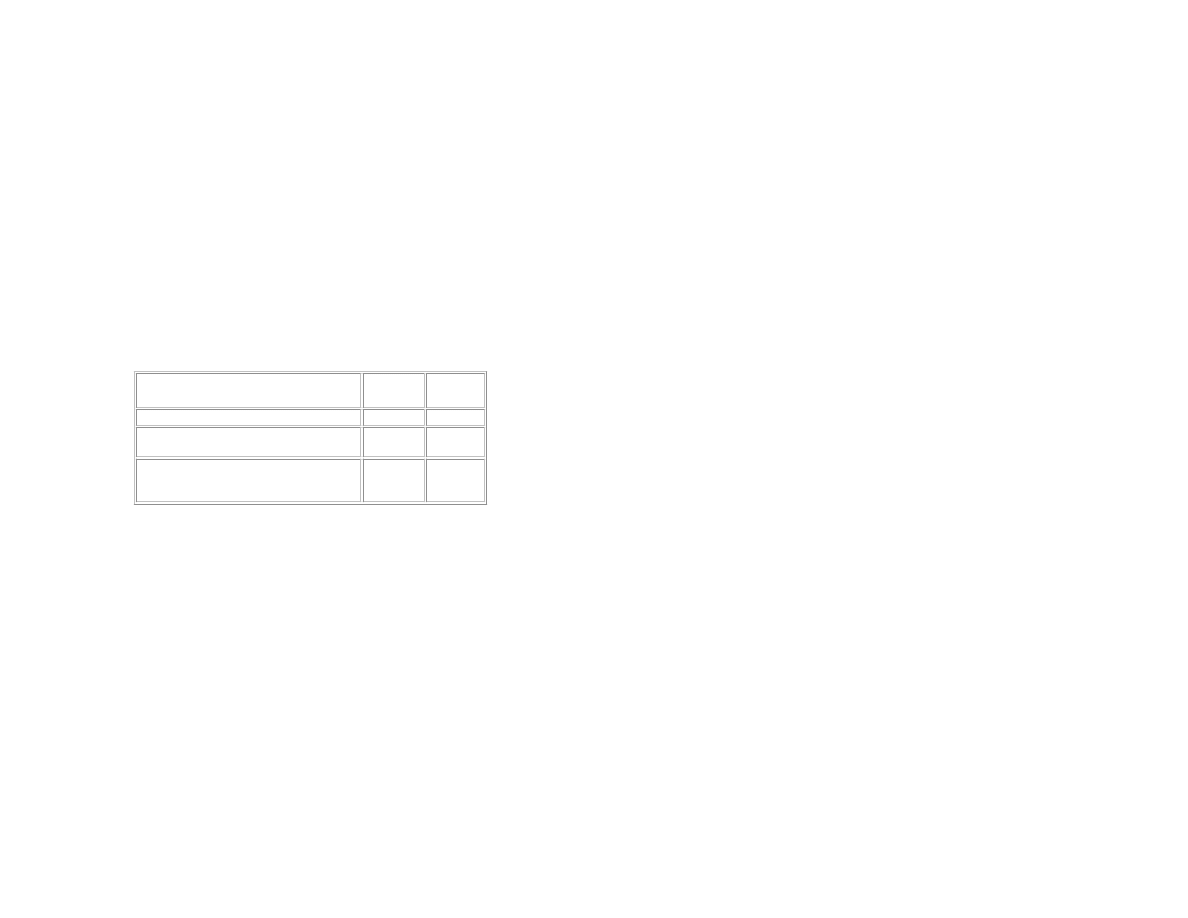

Thus we have the following:

Type of Causality

Act

(Passive)

Potency

creation/annihilation

esse

essentia

unqualified change:

generation & corruption

(substantial)

form

(primary)

matter

qualified change:

alteration & augmentation/diminution

& local motion

accident substance

B. Logical (alternatively: metaphysical) composition

The postulation of modes of physical composition arises from the analysis

of change; there is another sort of composition, the postulation of which

arises from broadly scientific considerations. If we think of scientific

theorizing as beginning with a taxonomy of natural kinds arranged

according to species and genus (reminiscent of Aristotle's category of

substance), and if we think of the goal of scientific inquiry as objective

knowledge of the natures of physical substances, then we will naturally ask

about the metaphysical grounds for our use of natural kinds terms, their

definitions, and predications in which such terms appear as the subject and

various (discovered) properties that 'emanate from' the relevant natures or

essences appear as predicates, e.g., 'Salt is soluble in water'. Such statements

(or 'laws') are in some obvious sense about universals or common natures

rather than primarily about singulars; or at least this much is true: If George

is a chunk of salt, then George is soluble by virtue of its being constituted as

a member of the natural kind salt.

Now all the scholastics agree that each secondary-substance or natural kind

Introduction to Scholastic Ontology

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/introsch.htm

4 of 4

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

term has a composite definition that signals similarities among natural kinds

as well as differences. For instance, both angels and aardvarks are

substances, but the former are immaterial whereas the latter are material.

The question then is: Is there a distinctive metaphysical constituent of a

substance corresponding to each element in its definition? To take the

simple hackneyed example, is there within a human being a distinctive

'metaphysical' constituent corresponding to each of the following

natural-kind terms: 'substance', 'body' ('material substance'), 'living

substance', 'sentient substance' ('animal'), 'rational', and, finally, 'human

being' itself?

Duns Scotus, for one, argued that there must be distinctive constituents of

this sort (he called them 'formalities') if scientific methodology and theories

are to be well-grounded. This is why he thought of them as 'metaphysical'

constituents and then was faced with the problem of relating these

metaphysical constituents to the corresponding physical constituents

(matter/form) of the same substance. Also, Scotus thought that among the

metaphysical constituents or formalities of a given substance there must be

an individuator or individual difference that accounts for that substance's

metaphysical distinctness from the other members of the same lowest-level

species.

Most other scholastics, by contrast, deny that substances have distinctive

metaphysical constituents in addition to their physical constituents.

According to them, the problem is to show how the various logical or

conceptual constituents of natural kind concepts and their definitions are

related to the physical constituents of the relevant substances. How, for

instance, are distinctions like matter/form and substance/accident related to

concepts of genus, species, and difference? And in the background is the

question that held Aristotle's attention in the impenetrable middle books of

the Metaphysics, viz., how can entities that exhibit these various modes of

composition have the unity characteristic of primary substances?

With this background we are ready to look at the first two sections of

Disputation 5, in which Suarez characterizes singular or individual unity and

then asks what this sort of unity adds to the common nature in such a way as

to compose with that common nature a singular substance.

Alfred J. Freddoso

University of Notre Dame

Disp. 5, sect. 1

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0501.htm

1 of 4

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

Disputation 5, Section 1:

Are all things that exist or are able to exist singular and

individual?

I. Reasons for doubting an affirmative answer (n. 1)

A. The case of God: The divine nature is communicable to the three

divine persons, in the same way that the common nature human being,

which is not a singular entity, is communicable to many individuals.

B. The case of angels: Angels have only specific or essential unity and

not numerical or singular unity. So each angel is akin to what the

common nature human being would be if it existed on its own as

such.

C. The case of common natures as existing in individuals: The

common nature human being exists in Peter and Paul and is not as

such a singular thing.

II. An analysis of the notion of individual (or singular or numerical)

unity (nn. 2-3)

A. Analysis: That which is singular or individual is opposed to that

which is common or universal (i.e., that which has specific or generic

unity rather than numerical unity) in the sense that that which is

singular or individual "is one in such a way that, under that notion of

being by which it is called one, it is not communicable to many as to

things which are [logically] inferior to or subordinated to it, or to

things which are many within that same notion." For instance, the

common nature human being lacks singular unity because it is

communicable to and common to many humanities (Peter, Paul, Joan,

etc.) which share the same notion, viz., human being. By contrast,

Peter, i.e., this humanity, is not common to many individuals which

share the notion this humanity. Also, Peter and Paul are subordinated

to human being in the sense of falling under it as determinates under a

determinable. So what is distinctive about numerical or individual

unity is the negation of a certain sort of divisibility, viz., divisibility of

a determinable into lower-level determinates.

B. Amplification: "Singular entitas is such that it is not the case that

its whole notion (ratio) is communicable to many similar entitates,

Disp. 5, sect. 1

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0501.htm

2 of 4

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

i.e., divisible into many entitates which are such as it itself is." Note

that even per accidens unities (e.g., a heap of stones), numbers greater

than one, and common natures (i.e., genera and species) themselves

have a sort of individuality. But they do not have full-fledged singular

unity because they are not per se entities, i.e., entities that as such

have natures capable of existing `in an unmediated way'. "So the

notion of per se individual and singular unity consists in entitas that is

by its nature one per se and is undivided or incommunicable in the

aforementioned sense."

III. the resolution of the question (nn. 4-5)

A. The answer: "Given that the notion of an individual or singular

being has been explicated in the above way, one should claim that all

things which are actual beings, i.e., which exist or are able to exist in

an unmediated way, are singular and individual. I say `in an

unmediated way' in order to exclude the common natures of things,

which cannot as such exist in an unmediated way or have actual

entitas except within singular and individual entities--the latter being

such that if they are destroyed, then it is impossible for anything real

to remain."

Question: Given this, what distinguishes common natures from

accidents?

B. Argument:

(1) Whatever exists has a fixed and determinate entitas.

(2) But every such entitas has an added negation.

Therefore, every such entitas has singularity and individual

unity.

Proof of (2): Every entitas, by the very fact that it is a

determinate entitas, is unable to be divided from itself;

therefore, every entitas is also such that it cannot be

divided into many entitates which are such as it is (since

otherwise the whole entitas would be in each of them and

so it would, insofar as it exists in one of them, be divided

from itself insofar as it exists in another--which is

manifestly absurd).

According to Suarez, this argument shows that universals

cannot exist in reality separate from singular things. The

argument depends crucially on the rhetorical question:

How can a universal be truly predicated of, or essentially

constitute, a singular thing unless it exists in that thing?

That is, how can the essence or nature of a given thing be

Disp. 5, sect. 1

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0501.htm

3 of 4

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

something separate from it that does not exist within it?

This is precisely the question that many modern-day

Platonists answer with a resounding: "Easy! That's just

the way it is."

IV. Reply to original reasons for doubting an affirmative answer (nn.

6-8)

To A: The divine nature is singular and is communicable to the

persons not as a superior to an inferior (or species to an individual),

but in the manner of a form to a suppositum. The nature is not divided

from itself, but instead is whole in each of them. Note, then, that the

relation of the divine nature to the three divine persons is not to be

thought of as like the relation of the common nature human being to

Peter, Joan, and Paul. It's rather as if the same singular humanity were

each of Peter, Joan, and Paul. This is why the Trinity is mysterious.

To B: Some Thomists think that spiritual natures are like abstract

specific essences, but this will be discussed later. In the meantime, we

simply deny that angelic natures are anything other than singulars, and

this independently of how one answers the question of whether an

angelic nature can be multiplied in many individuals within the same

species.

To C: Human being, as it exists in reality, is singular, since it is

nothing other than Peter, Paul, etc. But whether it is in any sense

distinct from the individuals will be discussed in the next chapter.

V. Three separate questions concerning individuation

A. The individuality question: What is the intrinsic principle by virtue

of which a thing of a given species, say the species aardvark, is this

aardvark or numerically one aardvark or an individual aardvark? That

is, what constitutes it as something which is, as the Latin term

individuum suggests, indivisible into things each of which shares the

very same notion?

B. The distinctness question: Given a pair of individuals of the same

species, what is the intrinsic principle by virtue of which this one is

distinct from that one? (Note that distinctness is different from

individuality or numerical unity, since distinctness, unlike

individuality, is a relation that presupposes the existence of at least

two individuals.)

Disp. 5, sect. 1

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0501.htm

4 of 4

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

C. The plurality question: What makes numerical plurality within a

given species possible? That is, what is the metaphysical ground for

the possibility that there should exist more than one individual of a

given species? (This question is obviously different from the

individuality question, since it is conceivable that an individual should

belong to a species that cannot be multiplied into many individuals;

this, of course, is just what St. Thomas himself believes to be true of

the angelic species. The plurality question also differs from the

distinctness question, even though they are intimately related; for the

distinctness question has a place only on the assumption that there is a

plurality of individuals within a given species.)

Disp. 5, sect. 2

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0502.htm

1 of 8

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

Disputation 5, Section 2:

Is it the case that in all natures the individual and singular thing

as such adds something over and beyond the common, i.e.,

specific, nature?

I. The nature of the question (nn. 1 & 7)

"In order to clarify what this [individual and singular unity] is, we

cannot do better than to explain what it adds over and above the

common nature, i.e., the nature that is conceived by us abstractly and

universally."

"None of the authors doubts that the individual adds, over and beyond

the common nature, a certain negation that formally completes or

constitutes the unity of the individual. This is evident ... from what we

said above concerning the notion or nominal definition of an

individual. Indeed, if we are speaking formally about the individual

insofar as it is one in the relevant sense, it adds a negation in its

formal concept not only over and beyond the common nature

conceived of abstractly and universally, but even over and beyond the

whole singular entitas conceived of merely under a positive concept;

for this whole entitas is not conceived of as one in a singular and

individual way until it is conceived of as incapable of being divided

into many things that have the same notion."

"Therefore, the present problem is not about whether or not such a

negation formally pertains to the notion of this sort of unity ... Rather,

it is a problem about the ground for this negation. For since it does

not seem able to be grounded in the common nature (given that the

common nature is of itself indifferent and does not require such a lack

of divisibility into many similar things, but is indeed divided into

them), we are asking what it is within the singular and individual

thing by reason of which this negation belongs to it."

So the question is: does individual unity add to the individual some

positive entity over and above the common nature, a positive entity

that grounds the indivisibility that defines individuality?

II. Three popular positions on this question (nn. 2-6)

Disp. 5, sect. 2

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0502.htm

2 of 8

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

A. Affirmative: "The first position affirms in general that at least in the

case of created things the individual adds to the common nature some

real mode which (i) is in reality distinct from the nature itself and

which (ii) composes, along with that nature, the individual itself."

Main protagonist: Scotus with his individual differences. The

main arguments stem from (i) the object of scientific

knowledge (viz., the common nature) and its distinction from

individuals that have that nature, and from (ii) reflection on the

idea that the common nature, which constitutes the essence of

the individual, is common to many individuals and so cannot

itself account for individuality, which must consequently be

traced to some other reality.

B. Negative: "The second position is the exact opposite, viz., that the

individual adds to the common nature nothing that is positive and real

and nothing that is distinct, either really or conceptually, from that

nature; rather, each thing or nature is per se an individual in an

unmediated and primary way."

Main protagonists: Ockham, Biel, and the other nominalists.

The main argument is that there is no conceivable thing that is

not singular and so it is absurd that an [already existent] thing

should become individual by the addition of some real thing

over and beyond the common nature. Also, this addition would

be either essential to the thing or accidental to it--and both

answers lead to absurdities.

C. Affirmative for material things and negative for spiritual things:

"The third position is able to make use of the distinction between

spiritual and material things. For in the case of immaterial things the

singular thing adds nothing over and beyond the common nature,

whereas in material things it does add something ... The foundation

for this position is the claim that since immaterial substances neither

have matter nor bespeak a relation to matter, it is impossible to

imagine anything in them which they add over and beyond the

essence, and so they are individuals by their very selves; by contrast,

in composite things designated matter is added, and from this matter

one can infer something that the individual adds over and beyond the

species."

Main protagonists: Various Thomists (including St. Thomas?),

following Aristotle's dictum that in material things there is a

distinction between the essence (quod quid est) of a thing and

that which has the essence (id cuius est), whereas there is no

such distinction in immaterial things. The background idea is

that in the case of material things matter is in some way a

source of individuality.

Disp. 5, sect. 2

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0502.htm

3 of 8

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

III. Suarez's resolution of the question (nn. 8-30)

In resolving this question Suarez asserts and defends four theses which,

taken together, define a position distinct from the three just noted. I will

state these theses and give the barest indication of how he supports them.

A. The Theses

Thesis 1 (n. 8): The individual adds, over and beyond the

common nature, something real by reason of which (i) it is an

individual of the sort in question, and by reason of which (ii)

the negation of divisibility into many similar things belongs to

it.

Thesis 2 (n. 9): The individual, as such, does not add anything

that is distinct in reality from the specific nature--that is,

distinct in such a way that in this individual, say Peter,

humanity as such and this humanity (or better: that which is

added to humanity in order for it to become this humanity,

something that is usually called a haecceity or individual

difference) are distinct in reality and thus bring about a true

composition within the thing itself.

Thesis 3 (n. 16): The individual adds, over and beyond the

common nature, something which (i) is conceptually (ratione)

distinct from the nature, which (ii) belongs to the same category

(i.e., the reality grounding the individual difference is not an

accident), and which (iii), as an individual difference that

contracts the species and constitutes the individual,

metaphysically composes the individual .

Thesis 4 (n. 21): The individual, not only in material things and

in accidents but also in created and finite immaterial substances,

adds something conceptually distinct over and beyond the

species.

B. The Main Arguments:

For Thesis 1 (n. 8): "The common nature does not of itself

require such a negation, and yet such a negation belongs per se

and intrinsically to that nature insofar as it exists in reality and

has been made a this. Therefore, it adds to the nature something

by virtue of which the negation is adjoined to it. For every

negation that intrinsically and necessarily belongs to a thing is

grounded in something positive, something that cannot be a

concept but is instead real, since the unity and negation in

Disp. 5, sect. 2

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0502.htm

4 of 8

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

question belong to the thing itself truly and of itself." So on this

point Suarez agrees with Scotus. His contention, I believe, is

best seen as a confirmation that there is something real in an

individual in addition to whatever objective grounding there is

for its being a member of a given species. This is a very general

claim that leaves open the question of whether there is a distinct

reality or entitas that grounds individuality. So Thesis 1 says

something like: "Yes, there is an objective ground for

individuality, just as there is an objective ground for

membership in a natural kind, and we can at least make a

conceptual distinction between the two and think of the former

as adding something to the latter."

For Thesis 2 (nn. 9-15): Here Suarez first points out that anyone

who denies that natures exist in reality as universals ought to

accept this thesis, since a denial of Thesis 2 involves the claim

that the common nature is itself a thing (res) or at least a mode

with its own per se unity. From here the dialectic becomes

complicated, mainly because Suarez attempts to meet head-on

the Scotistic claim that there is an objective distinction, viz., a

formal distinction, between the common nature and the

individual difference. The best way to think of Scotus's formal

distinction is this: In the case of the human being Socrates,

corresponding to the terms or concepts human nature and

Socrates there are two 'formalities' or 'realities', the common

nature and the individual difference, which in themselves have

the sort of individuality appropriate to them but which unite

inseparably in the individual Socrates to constitute that

individual with its numerical or singular unity. So in itself the

nature has a "formal unity" that is "less than numerical unity,"

though as it exists in Socrates it is 'contracted' to this individual

and is 'really' identical with Socrates and his individual

difference. So within Socrates himself the common nature and

individual difference are "formally distinct from one another

but really identical with one another," where the formal

distinction is not just a conceptual distinction, but a distinction

'in reality', to use Suarez's term. Suarez, like most other

scholastics, finds this notion of a 'formal distinction' baffling

and full of contradictions: "Even though within the nature

[considered in abstraction from its individuation] this formal

unity can be conceptually distinguished from individual unity,

nonetheless it is inconceivable that it should, as abstracted, exist

in reality with its own entitas and be distinct in reality from

individual unity, and that it should as such also lack universal

unity." His own contention is that within the individual there is

an objective ground for the distinction between the concepts of

the common nature and the individual, but that there is no neat

fit between these concepts and the actually existing individual.

Disp. 5, sect. 2

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0502.htm

5 of 8

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

An argument that illustrates this is found in n. 14: "The

individual differences of Peter and Paul are distinct in reality

from one another as two things (res) that are incomplete but

singular and individual in the way in which they exist. And yet

these individual differences have a similarity to and agreement

with one another. For they are in fact more similar to each other

than they are to the individual difference of a horse or a lion.

And [yet] it is not necessary to distinguish in reality, within

them, a thing in which they are similar from a thing in which

they are distinct. Otherwise, there would be an infinite

regress--which is absurd among things or modes that are

distinct in reality."

For Thesis 3 (nn. 16-20): This thesis follows rather

straightforwardly from the first two, since if the individual adds

something to the nature in the way explained above but is not a

distinctive real entity, then the distinction between what

grounds the attribution of the common nature and what grounds

the attribution of individuality must be a well-grounded

distinction among concepts, where the composition alluded to

in part (iii) of Thesis 3 is a composition of concepts or a 'formal'

composition.

For Thesis 4 (nn. 21-30): It is only in the case of an infinite

being that a metaphysical (i.e., conceptual) composition of the

sort in question cannot even be imagined. And given the

explanation of the first three theses there is no reason why even

immaterial substances should not fall under those theses: "For

in any immaterial substance that is individual and finite, e.g.,

the archangel Gabriel, the mind conceives both (i) this

individual (since it conceives numerically this individual) and

(ii) its essential and specific notion, which does not essentially

include either (i) numerically this entitas or (ii) any positive

repugnance toward its being able to be communicated to

another individual. Therefore, in such a case the mind conceives

something common and something which is conceptually added

to the latter in order that it be determined to this individual.

Therefore, in precisely this respect there is no difference

between immaterial substances and other things." Suarez then

goes on to counter the arguments of Thomists by accusing them

of begging the question by presupposing that matter is the

ground or principle of individuation. But this will be disproved

in the next section. Also, he points out that even if matter were

the principle of individuation for material things, it would not

follow that individuality does not have some other principle in

angels. We have to look at each case separately.

Disp. 5, sect. 2

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0502.htm

6 of 8

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

IV. Replies to the three positions laid out at the beginning (nn. 31-39)

A. Reply to First Position (IIA above and nn. 31-33): The arguments

for this position "establish only that the specific nature expresses an

objective concept that is abstracted by reason from the individuals and

that, conversely, the individual adds something conceptually distinct

over and beyond the common nature. For human science has to do

with things as conceived universally, to which definitions and

demonstrations pertain immediately. And for this it is sufficient that

they be able to be abstracted conceptually, even though they are not

separate in reality. This is clear from what was said above about the

concept being, about which (i) there is scientific knowledge and about

which (ii) demonstrations can be made, even though it is obvious that

it does not in fact exist as abstracted from the proper notions of

beings, but instead is abstracted only conceptually. Hence, this sort of

distinction is also sufficient for causal locutions such as 'Because man

is risible, Peter is risible'. For in these locutions there is no real and

physical cause that mediates between Peter and risible, but instead

what is being explicated is the adequate reason and origin of the

property in question." What's more, in the other arguments for this

position there is a fallacy committed when one "argues from our mode

of conceiving, or from the use of the words by which we signify

things as conceived by us, to the things as they exist in themselves,

thus inferring a distinction among things from a conceptual

distinction." This latter sort of fallacy was labeled by Ockham as one

of the two worst mistakes in philosophy. (The other was the

postulation of universals as separately existing entities.)

B. Reply to Second Position (IIB above and nn. 34-37): In the end

Suarez's own position has a marked similarity to this second position

and so it is interesting to see his reply to it. "As for the first argument

for the second position, one may reply that the argument correctly

proves that a thing is not made singular through the addition of a

reality or mode that is distinct in reality from the nature which is said

to become singular ... . However, that argument does not prove that it

is impossible for a thing to be made singular through the addition of

something that is conceptually distinct, since this sort of distinction

does not presuppose an actual entitas and hence does not presuppose

singularity in both of the terms. For since this distinction exists by

means of concepts, it can be readily understood to be a distinction

between a thing conceived universally and its mode." Notice that in

replying to Cajetan Suarez is careful to separate the act/potency

distinction as applied to real entities from the act/potency distinction

as applied analogously to concepts. After denying that the reality

which grounds individual unity can be accidental to the individual,

Suarez gives the following, rather illuminating summary:

"Thus it follows that our mind conceives that in which the

Disp. 5, sect. 2

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0502.htm

7 of 8

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

individuals agree with one another as some one thing and as

that which is 'formal' in them and which contributes per se to

scientific knowledge. For a distinction merely in entitas is

thought of as being, as it were, accidental and so is called

'material'. And for the same reason there is no scientific

definition except of the common and specific concept; and it is

in this sense that the lowest-level species is called the whole

essence of the individuals, viz., the essence as formally and

precisely taken and conceived, and the essence insofar as the

cognition of it merits human scientific knowledge. For

scientific knowledge does not descend to particulars according

to their proper and individual notions, since it is unable to grasp

them as they exist in themselves and does not deal with the

accidents proper to individuals. For either these accidents

belong to them contingently and accidentally; or else, if some

are perchance altogether proper, then they are as hidden as

individual differences are. And, finally, it would be a difficult

and almost infinite task to descend to each particular. Yet there

is no doubt that individuals, even if they differ solely in

number, have distinct essences in reality--essences which, if

they were conceived of and explicated as they exist in

themselves, would have to be explained through diverse

concepts and definitions. And they would also have distinct

properties, at least in reality or in accord with some proper

mode, and under this notion they are subject to angelic and

divine knowledge."

C. Reply to Third Position (IIC above and nn. 38-39): Suarez finds in

Aristotle no good argument for the claim that there is a deep

difference between immaterial and material substances on the issue of

individuation and individuality. In reply to the argument he says the

following:

"Even though this principle of individuation [viz., matter] does

not exist in immaterial things, there must nonetheless be some

analogous principle. For even these substances are individuals

not by dint of their specific notion but by dint of their singular

notion. Hence, when a spiritual substance is said to be an

individual by its very self, if 'by its very self' is taken to mean

'by dint of its specific notion,' then the question is begged and

something false is assumed, as has been shown. On the other

hand, if 'by its very self' is taken to mean 'through its own

entitas,' then this is indeed true, but it does not at all prevent it

from being the case that within that very entitas the specific

notion and the individual difference are conceptually distinct,

and that the same entitas can in different respects be the

principle and ground for both of them. For on this point the

argument is almost the same as in the case of material

Disp. 5, sect. 2

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0502.htm

8 of 8

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

substances. For regardless of whether it is designated matter or

some other thing that is called the principle of individuation for

material substances, this principle cannot be anything that is not

the essential entitas itself of the thing--whether its whole entitas

or part of it. Hence, within that entitas one has to distinguish

both (i) the specific notion, by reason of which [the entitas] is

said to be the essence or a part of the essence, and (ii) another

notion that is conceptually but not really distinct, by reason of

which [the entitas] is said to be the principle of individuation."

Disp. 5, sect. 3

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0503.htm

1 of 9

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

Disputation 5, Section 3:

Is designated matter the principle of individuation in material substances?

I. The meaning of the question (nn. 1-2)

We have already seen that we can think of the individual as adding something real to the

common nature in such a way as to constitute the individual. The composition itself is a

'metaphysical' composition in which the specific nature is contracted by the individual

difference in such a way as to formally constitute the individual--in a way strictly analogous

to that in which the generic nature is contracted by the specific difference to constitute the

species. Thus, some philosophers, most notably Scotus, have assumed that once we

understand this relation between the specific nature and the individual, we see that the

principle of individuation is the individual difference, and so there is no need to look for any

further principle of individuation.

But, of course, on Suarez's view the composition in question, while grounded in reality, is

itself merely a conceptual composition. So there is, he insists, a further question: What is it

within the thing itself that grounds the concept of the individual difference? And to motivate

the question, he notes, first, that philosophers often say, in the case of the definition of a

species, that the genus is taken from the matter whereas the specific difference is taken from

the form--and this even though the species is composed 'metaphysically' of the genus and

specific difference. Second, and perhaps more illuminating, we can understand what is

meant by saying that among the predicates true of a given substance, say the man Socrates,

(i) some are taken from his matter (e.g., 'material substance', 'snub-nosed', 'six feet tall'), (ii)

some are taken from his form (e.g., 'rational', 'capable of free decision'), and (iii) some are

taken from the composite (e.g., 'human being', 'tentmaker'). So the search for a principle of

individuation is a search for the physical component or components grounding the concept

of the individual difference.

II. Matter as the principle of individuation: initial exposition and objections (nn. 3-7)

A. The lure of matter: It is easy enough to see why matter might at first seem relevant to the

question of what distinguishes individuals of the same species from one another. It seems

that two red oaks, for instance, are distinct from one another because they are or include

distinct 'packets' of matter. Aristotle seems to have been of this view, as well as St. Thomas.

As a matter of fact, though, Suarez thinks that the authorities appealed to by this position

are a lot more impressive than the arguments usually adduced for it. Let us look briefly at

the three arguments and Suarez's reply to them. (It should be noted that unless otherwise

indicated, the term 'matter' is being used here to denote the bare primary principle of

determinability in material things, prior to and independently of its receiving quantity, i.e.,

determinate geometrical dimensions. Matter as subject to determinate dimensions is materia

Disp. 5, sect. 3

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0503.htm

2 of 9

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

signata a quantitate or designated matter.)

B. Arguments and objections

Argument 1:

(1) Matter is the principle of multiplication and numerical distinctness among

individuals within the same species.

(2) But that which is the principle of numerical distinctness is also the principle

of individuation.

Therefore, matter is the principle of individuation.

Objections:

Someone could readily reply that (1) is false. For that which is the principle of

distinctness is also the principle of multiplication, and, as St. Thomas himself

says, the first principle of distinctness is not matter, but form. The idea is

something like this: In the division of, say, armadillohood into distinct

individuals, a given individual's having armadillo-like geometrical dimensions

is metaphysically prior to and explains the division of the relevant matter into

distinct armadillo-like packets. Some Thomists accept this and claim that

numerical unity has two aspects, viz., (i) incommunicability to inferiors and (ii)

distinctness from other individuals, and that matter as such is the principle only

of the incommunicability, whereas quantity is the principle of the distinctness.

The idea is that matter, taken as completely bereft of form, itself stands in need

of some form, viz., determinate quanititative dimensions, in order to be

chopped up into distinct packets, as it were. These authors must thus disavow

Argument 1. Note that Suarez does not endorse this objection without

qualification. However, he does take these Thomist arguments to show at least

that there is no reason why the whole notion of numerical distinctness should

be attributed to matter rather than to form. For Suarez himself will try to show

that even matter as such has some 'entitative act' that distinguishes one matter

from another.

---------------------------------------------------

Argument 2:

(1) It is that which is incommunicable to similar inferiors that is an individual.

(2) But matter is the first ground and principle of this incommunicability (given

that form is an act and so is of itself communicable to something, viz., matter).

Therefore, matter is the principle of individuation.

Objections:

In reply Suarez claims that (1) is equivocal and goes on to distinguish no fewer

than five possible sorts of communicability and corresponding

incommunicability:

(a) x's communicability to y insofar as y is a subject which x informs or in

which x inheres

(b) x's communicability to y insofar as x is a cause of y

(c) x's communicability to y insofar as x is a part of y

Disp. 5, sect. 3

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0503.htm

3 of 9

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

(d) x's communicability to y insofar as x is a nature had by the

suppositum y

(e) x's communicability to y insofar as x is a superior shared by y, which

is inferior to it or subordinated to it.

Matter is indeed incommunicable to anything in sense (a). But this sort of

incommunicability is not necessary for individuation, since accidents (and

substantial forms) lack it even though they are individuals. Nor is it sufficient

for individuality, since matter is incommunicable in this sense by dint of its

species and yet is not an individual by dint of its species, but is instead by dint

of its species common to many numerically different matters.

In sense (b) matter is communicable to form in the sense of sustaining it and in

that way being a 'cause' of it.

In sense (c) matter is communicable to the composite substance as a part to a

whole and as a (material) cause to its effect. For it communicates actual entitas

intrinsically (as opposed to extrinsically, like an efficient cause) to the

composite.

In sense (d) matter, as a part of the nature of a composite substance, is

communicable to its own suppositum, i.e., to the substance qua ultimate subject

of predication.

Finally, in sense (e), which is the sense relevant to individual unity, matter is as

such communicable to many inferiors, which can be its subject in the order of

predication--as when we say that Socrates has matter and Plato has matter.

Someone might object that it is matter in general, and not the designated matter

of the individuals, that is communicated in this way, and that designated matter,

by contrast, is not so communicable and can thus be the principle of

individuation. The reply is that designated matter does not have its

incommunicability by virtue of its being the first and most basic subject, which

is the notion appealed to by Argument 2. So if it is incommunicable, it gets this

incommunicability from something other than its being matter. But this

'something other' will be a feature that it shares with form (see below). This is

borne out by the fact that God and angels are 'first subjects' in the relevant sense

even though they have no matter.

---------------------------------------------------

Argument 3:

(1) The individual is the first subject in a metaphysical (categorial) ordering

(since all the superiors are predicated of it).

(2) Therefore, the first principle and ground of the individual as such must be

that which is the first subject among the physical principles or components of

the individual.

(3) But this is matter.

Therefore, matter is the first principle and ground of the individual as such.

Objections:

Being a subject of inherence (as matter is) is far different from being a subject

of predication (as the individual is). Even though there is an analogy between

the two, one sees in the case of simple substantival forms a subject of

Disp. 5, sect. 3

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0503.htm

4 of 9

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

predication without any subject of inherence. And an individual is as such a

first subject of predication: "Thus it is not necessary for that which is the first

subject in the order of generation and imperfection to be the first principle and

ground of the individual, which is the first subject in the order of predication,

containing within itself all the perfection of the superiors and adding something

proper by which it, as it were, completes and brings to fulfillment those

perfections."

III. The three modes of explaining designated matter (nn. 8-33)

A. Introduction (n. 8): Despite the fact that the foregoing arguments do not establish that

matter is the ground or principle of individuation, the authority of Aristotle and St. Thomas

is great enough that this position would at least be a reasonable one if it could be plausibly,

even if not absolutely convincingly, defended. The first difficulty is that matter is itself

common--common not only in the sense that it is communicable to many individuals at

once as a quasi-species but also in the sense that numerically the same 'chunk' of matter can

exist 'under' many forms successively in time. This is why the Thomists claim that it is not

matter as such, but rather designated matter, i.e., matter 'signed by quantity' and possessing

determinate geometrical dimensions, that is the principle of individuation. But the

explication of this notion is subject to many difficulties and disagreements. Suarez's strategy

is to distinguish three different accounts of designated matter and to show that each of them

fails as an account of the principle of individuation.

B. First analysis (nn. 9-17)

"The first explanation is that matter signed by quantity is nothing other than matter

with quantity or matter affected by quantity; they think that the principle of

individuation is, as it were, wholly made up of these two things, so that matter confers

incommunicability and quantity confers [numerical] distinctness, as was explained

above."

The argument:

(1) In order for matter to be the principle of individuation, something is

required that distinguishes this matter from that matter.

(2) But this something is not matter itself, since distinctness must be brought

about by an act, whereas matter as such is pure potentiality.

(3) Nor is this something the [substantial] form, since, to the contrary, this form

is distinct from that form precisely because it is effected and received in a

distinct matter.

Therefore, this something is quantity.

Three objections:

(1) On the assumption that the proponents of the argument hold, as they do,

that quantity inheres in and is an accident of the whole composite substance

and not the matter of the substance, so that the same quantity does not perdure

Disp. 5, sect. 3

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0503.htm

5 of 9

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

through generation and corruption: The substance qua individual is

metaphysically prior to quantity in the way that a substance is metaphysically

prior to its accidents. Hence, the quantity cannot constitute the substance as an

individual. "From this it follows that at first numerically this form is introduced

into this matter, and that the quantity follows upon this."

(2) On the assumption that the proponents of the argument mean to claim that

the quantity inheres in the matter prior to its inhering in the composite

substance, so that the quantity perdures through generation and corruption:

On this view designated matter, as well as matter as such, can exist under

diverse forms and hence in numerically distinct individuals. So just as they

argued above that common matter cannot be the principle of distinctness, so by

the same argument it follows that designated matter cannot be the principle of

distinctness or the principle of individuation. The Thomistic reply to this

objection plunges us into the labyrinth of St. Thomas's commentary on

Boethius's De Trinitate. For the claim is that it is matter with indeterminate

dimensions (perhaps: matter with some determinate dimensions or other) that is

thus common, whereas matter with determinate dimensions (perhaps: matter

with these particular dimensions) is not common in this way. In response,

Suarez asks: What do these determinate dimensions add over and beyond

quantity? If they add only a certain width, breadth, and depth, the same problem

arises since such dimensions can be common to many individuals. If they add

in addition certain dispositions, causal properties, and other qualities that

together determine the matter to one individual substantial form rather than

another, then, to be sure, designated matter in this sense cannot be common to

another. But this cannot be what the Thomists mean and, in addition, it cannot

be true. For, first, if this were so, then it would be more than quantity that is the

principle of individuation; it would be "quantified matter as signed by these

qualities". Second, on this view the accidents by which the matter is disposed

for this form would be intrinsically included in the principle of individuation;

but the accidents of a substance, in contrast to its principle of individuation,

cannot be intrinsically and formally included in the substance itself (thought of

as distinct from its accidents). Rather, they presuppose the substance and as

such are posterior to it.

(3) "By abstracting from [the above assumptions] we argue in a third way: Even

though a thing's existing in itself as one thing is prior in nature to its being

distinct from other things, still, the latter follows intrinsically from the former

without any positive addition that comes to the thing that is one; rather, it

follows just through the negation by which, once the other term is posited, it is

true to say that this is not that. And so the same positive thing which grounds

the unity as regards the first negation, i.e., the intrinsic indivisibility,

consequently grounds in addition the second negation, i.e., the distinctness

from another. On this score it is often said--and absolutely correctly--that a

thing is distinct from others by virtue of that through which it is constituted in

itself, since it is distinct by virtue of that by which it exists ... Therefore, in the

case of individual unity, that which is the principle of the individual as regards

its constitution and its incommunicability or indivisibility in itself is also the

principle of its distinctness from others. And, conversely, whatever is the

Disp. 5, sect. 3

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0503.htm

6 of 9

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

principle of distinctness must also be the principle of constitution. Therefore, if

matter, by itself and excluding quantity, constitutes an individual that is in itself

incommunicable and one, then it also makes it distinct from others;

alternatively, if it cannot confer distinctness, then it cannot confer the

incommunicability of individuation, either ... And the same argument can be

made with regard to quantity as well." Suarez goes on to make a distinction

among three different kinds of distinctness and corresponding unity:

(a) distinctness with respect to quantity (distinctio quantitativa): Quantity

first gives its substance quantitative unity, "which consists in its being the

case that one substance exists under quantitative limits distinct from

those of another substance, in such a way that the one is not continuous

with the other by a proper continuity of quantity." Suarez has already

argued that quantitative unity presupposes the individual unity of the

substance it modifies and hence cannot be the ground for that individual

unity.

(b) distinctness with respect to position or place (distinctio situalis):

Quantity then (i.e., later in the order of nature) makes it the case that "one

substance exists outside the position or place of another." The

corresponding sort of unity is obviously extrinsic to a material substance,

since such a substance can change its place without ceasing to exist as

the same individual.

(c) numerical distinctness: the contrary of numerical unity, the sort we

have been talking about.

His claim is that (c) is prior to (a) and (b). Indeed, this account of the relation

between individual or numerical unity, on the one hand, and quantitative and

positional unity on the other leaves open at least the following conceptual

possibilities: that a material substance should exist without any quantity at all,

i.e., without determinate dimensions; that a material substance should exist

without being in a place; that a material substance should exist at one and the

same time in two discontinuous places; that two material things should exist in

exactly the same place. As a matter of fact, Suarez has theological reasons for

thinking that God can actualize each of these possibilities. But even someone

who is sceptical on that point can at least appreciate the fact that there are

distinct concepts involved in the three sorts of distinctness and that we can ask

coherently whether, say, two distinct material bodies can occupy the same

place, or whether one material substance can simultaneously be in two distinct

places. Suarez ends this section by accusing Soncinas and Ferrariensis of

conflating the transcendental unity which is the subject of the present

disputation and the categorial unity or oneness which is conferred by a

substance's quantity and which, as we have seen, presupposes transcendental

unity.

C. Second analysis (nn. 18-27)

"The second explanation is that matter signed by quantity includes quantity itself not

Disp. 5, sect. 3

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0503.htm

7 of 9

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

intrinsically, but rather as the terminus of the matter's disposition toward quantity. For

matter is by its nature susceptible to quantity, but it cannot as such be the complete

principle of individuation. For it is indifferent to any given quantity, just as it is

indifferent to any given form. However, by the action of the agent previous to

generation the matter is determined in such a way as to be susceptible to this quantity

and not another; and it is this matter which, as such, is called the principle of

individuation. By 'quantity' here we mean not just mathematical quantity but physical

quantity, i.e., quantity affected by physical qualities and dispositions." So on this view

matter signed by quantity is matter as predisposed by an agent for this determinate set

of dimensions. Thus, the objection to the first analysis is circumvented by the fact that

on this analysis the principle of individuation precedes the actual inherence of

quantity in either the matter or the substance. Rather, the matter is signed by virtue of

the fact that the agent imparts to it a disposition for this set of quantitative

dimensions.

Rationale:

The ensuing discussion becomes fairly complicated, but is interesting because it

gets to the heart of Aristotelian anti-reductionism. To see this, ponder the

following question: What is it that distinguishes a unified living organism at the

instant of its generation from an agglomeration of the preexisting substances

that provide the new substance's matter? On an Aristotelian view, the general

ontological answer to this question is that at that instant the matter in question

is informed directly and primarily by the new organism's substantial form or

form of the whole. It is this principle which unifies the substance and to which

all its characteristics, dispositions, and powers are subordinated. But in order

for this to be the case, and in order for it to be the case further that the accidents

of the new organism are primarily its accidents and not the accidents of the

other substances from which it was formed, we must conceive of the matter that

is so informed by the substantial form as being, at the instant of generation, a

materia nuda that is wholly receptive and wholly non-resistive with respect to

the form. We should note immediately that this does not entail that it is

naturally possible that just any substantial form should inform the matter at that

instant, since, as Suarez puts it, there is "a natural sequence by which this agent

here and now is determined by a natural ordering to introduce this form,

immediately after this alteration." Nor does it entail that materia nuda can ever

exist on its own as such. Nonetheless, if substantival generation is indeed

possible, it must be the case at the instant of generation that (i) the previous

substances, now altered in such a way as to prepare for the generation of the

new substance, cease to exist as such, along with their accidents, and that (ii)

the matter of the old substances comes directly under the unifying function of

the new substantial form.

Objections:

Given this picture, it is easier to understand the dialectic that unfolds as Suarez

criticizes the second analysis. The proponents of this analysis agree that what

makes the organism an individual cannot be quantity insofar as quantity is one

of its accidents, and this for the reasons set out above. Thus if designated matter

Disp. 5, sect. 3

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0503.htm

8 of 9

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

is to be the principle of individuality, it must be conceived of as naturally (even

if not temporally) prior to the generation of the substance as an individual. This

is why, on the second analysis, matter as the ground for individuation is the

matter insofar as it is conceived of as (i) naturally prior to the generation, (ii) in

the immediate or last preparation (or disposition) for the form, and (iii)

predisposed for the particular quantitative dimensions which will characterize

the substance itself. Much of Suarez's argument is meant to show these three

requirements are in conflict, since (i) and (ii) entail that what we are talking

about is materia nuda, whereas (iii) entails that this matter has positive

dispositions. All the attempts to avoid this basic contradiction are found

wanting.

D. Third analysis (nn. 28-33)

This analysis in effect gives up the claim that designated matter is in any way an

intrinsic principle of individuality. Suarez attributes four theses to the proponents of

this analysis:

Thesis 1: "Thus, first of all, speaking of the principle that constitutes the

individual in reality and from which is truly taken the individual difference that

contracts the species and constitutes the individual, this position denies that

designated matter is the principle of individuation."

Thesis 2: "Second, this position claims that matter is the principle and root of

the multiplication of individuals among material substances."

Thesis 3: "Third, this position claims that matter signed by quantity is the

principle and root of--or at least the occasion for--the production of this

individual as distinct from the rest."

Thesis 4: "Fourth, this position adds that 'matter signed by sensible quantity'

expresses the principle of individuation with respect to us, since it is through

this principle that we have cognition of the distinction of material individuals

from one another."

Suarez accepts Thesis 1, and he also accepts a version of Thesis 2 according to which

matter as such (rather than designated matter) is the principle of multiplication among

material substances. There is a long discussion of Thesis 3, in which Suarez poses

two interesting questions:

(a) Is matter the explanation for the fact that in a given instance of efficient

causality, it is this rather than that actual individual that is produced?

(b) Is matter the explanation for the fact that in a given instance of efficient

causality, it is this rather than some other possible individual, whose essence

would include just the same matter, that is produced?

He answers yes to (a). And he also gives a tentative yes to (b), as long as the matter is

thought of as designated and affected by other dispositions. He also accepts Thesis 4,

but worries in the end about whether this third analysis of designated matter is really

Disp. 5, sect. 3

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0503.htm

9 of 9

06/12/2006 08:37 p.m.

what St. Thomas had in mind, since it gives no rationale for St. Thomas's insistence

that angelic species cannot be multiplied in many individuals.

Disp. 5, sect. 4

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0504.htm

1 of 3

06/12/2006 08:38 p.m.

Disputation 5, Section 4:

Is the substantial form the principle of individuation in material substances?

I. The two principal arguments (nn. 1-2)

A. Argument 1

"The principle of individuation has to be something which (i) intrinsically constitutes

this substance and which (ii) is maximally proper to the substance. Thus, by reason of

the first property it has to be something substantival. For accidents, as has been said

repeatedly, constitute neither substance nor this substance, since this substance,

insofar as it is a this, is a per se and substantival being. On the other hand, by reason

of the second property the principle in question cannot be matter, but [must be] form.

For this matter is not maximally proper to this individual, since it can exist under

other forms as well. Therefore, form is the principle of individuation."

B. Argument 2

"The principle of unity is the same as the principle of entitas, since, as St. Thomas

says, 'Each thing has esse and individuation according to the same [principle].' But

each thing has its esse properly from its form. Therefore, it also has its individual

unity from the form. The major premise is obvious from the fact that unity is a

property that follows upon esse, and it adds to the latter only a negation; therefore,

unity cannot have a positive and real principle other than that which is the principle of

the entitas itself."

II. The evaluation (nn. 3-6)

A. Objection

The main objection to this position is that the two arguments just adduced prove at

most that form is a principle of individual unity, but not that it is the only such

principle. For the matter, too, constitutes the substance intrinsically and is thus at least

part of the principle of individual unity.

B. Reply 1

One reply to this objection is that the form individuates not only the substance but the

matter as well.

Disp. 5, sect. 4

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0504.htm

2 of 3

06/12/2006 08:38 p.m.

However, Suarez criticizes this reply in various ways. For one thing, it makes

mincemeat out of the Aristotelian contention that generation is a genuine change

because the very same matter is at first under one form and then under another. But

this cannot be true if the form makes the matter it informs to be this matter. Instead,

the matter at the terminus a quo of the change would not be the same as the matter at

the terminus ad quem.

C. Reply 2

"It is true, to be sure, that the adequate intrinsic cause of a material substance's

individual unity is, as the objection concludes, both the form and the matter.

However, if these two [principles] are compared with one another, the principal cause

of this unity is the form, and it is in this sense that it is especially attributed to the

form that it is the principle of individuation." For the form completes the individual in

the same way that the specific difference (form) completes the species. "The common

way of thinking and talking confirms this. For if, say, to Peter's soul there is united a

body composed of matter that is distinct from the body that he previously had, then

even though this latter composite is not identical in every part with the one that

existed before, the individual is still called the same individual, absolutely speaking,

by reason of the same soul." But the converse does not hold. This indicates that the

form, rather than the matter, is the principal principle of individuation.

Suarez is not utterly impressed by this reply, mainly because it still leaves open the

question: What makes this form itself a this? "It is not form as such, but rather that by

virtue of which the form is a this, that is the principle of individuation." And some

argue that this latter thing is the matter.

Now Suarez himself, of course, does not accept this answer to the question. Indeed,

he tries to show that exactly the same question arises with respect to the matter.

"Thus, all the arguments adduced above can prove the same thing about the matter

that they intend to prove about the form. For on this score there is a sort of parity

between the matter and the form. And from another angle the matter surpasses the

form only because it provides a certain occasion for producing various and individual

forms, whereas the form surpasses the matter because it principally constitutes the

individual, because it is more proper to it, and because it is the matter that exists

because of the form rather than vice versa." Nonetheless, he believes that even if

'matter' is a bad answer to the question, the question itself is nonetheless legitimate

and requires a reply that takes us beyond the account of individuation proposed in this

section.

III. The resolution (n. 7)

"Thus the present position, as we have explained it, is rather plausible and gets close to the

truth. Nonetheless, one should say without qualification that the form alone is not the full

and adequate principle of individuation for material things, if we are talking about their

entire entitas--even though it is the principal principle and is thus sometimes, according to

the formal mode of speaking, judged sufficient for denominating that same individual. All

Disp. 5, sect. 4

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0504.htm

3 of 3

06/12/2006 08:38 p.m.

of this will be clarified and proved at length in section 6."

Disp. 5, sect. 4

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0504.htm

1 of 3

06/12/2006 08:38 p.m.

Disputation 5, Section 4:

Is the substantial form the principle of individuation in material substances?

I. The two principal arguments (nn. 1-2)

A. Argument 1

"The principle of individuation has to be something which (i) intrinsically constitutes

this substance and which (ii) is maximally proper to the substance. Thus, by reason of

the first property it has to be something substantival. For accidents, as has been said

repeatedly, constitute neither substance nor this substance, since this substance,

insofar as it is a this, is a per se and substantival being. On the other hand, by reason

of the second property the principle in question cannot be matter, but [must be] form.

For this matter is not maximally proper to this individual, since it can exist under

other forms as well. Therefore, form is the principle of individuation."

B. Argument 2

"The principle of unity is the same as the principle of entitas, since, as St. Thomas

says, 'Each thing has esse and individuation according to the same [principle].' But

each thing has its esse properly from its form. Therefore, it also has its individual

unity from the form. The major premise is obvious from the fact that unity is a

property that follows upon esse, and it adds to the latter only a negation; therefore,

unity cannot have a positive and real principle other than that which is the principle of

the entitas itself."

II. The evaluation (nn. 3-6)

A. Objection

The main objection to this position is that the two arguments just adduced prove at

most that form is a principle of individual unity, but not that it is the only such

principle. For the matter, too, constitutes the substance intrinsically and is thus at least

part of the principle of individual unity.

B. Reply 1

One reply to this objection is that the form individuates not only the substance but the

matter as well.

Disp. 5, sect. 4

http://www.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/618/dm0504.htm

2 of 3

06/12/2006 08:38 p.m.

However, Suarez criticizes this reply in various ways. For one thing, it makes

mincemeat out of the Aristotelian contention that generation is a genuine change

because the very same matter is at first under one form and then under another. But

this cannot be true if the form makes the matter it informs to be this matter. Instead,

the matter at the terminus a quo of the change would not be the same as the matter at

the terminus ad quem.

C. Reply 2

"It is true, to be sure, that the adequate intrinsic cause of a material substance's

individual unity is, as the objection concludes, both the form and the matter.

However, if these two [principles] are compared with one another, the principal cause

of this unity is the form, and it is in this sense that it is especially attributed to the

form that it is the principle of individuation." For the form completes the individual in

the same way that the specific difference (form) completes the species. "The common

way of thinking and talking confirms this. For if, say, to Peter's soul there is united a

body composed of matter that is distinct from the body that he previously had, then

even though this latter composite is not identical in every part with the one that

existed before, the individual is still called the same individual, absolutely speaking,

by reason of the same soul." But the converse does not hold. This indicates that the

form, rather than the matter, is the principal principle of individuation.

Suarez is not utterly impressed by this reply, mainly because it still leaves open the

question: What makes this form itself a this? "It is not form as such, but rather that by

virtue of which the form is a this, that is the principle of individuation." And some

argue that this latter thing is the matter.

Now Suarez himself, of course, does not accept this answer to the question. Indeed,