J

OANNA

A

NTOSZEWSKA

Class II Division 2 Treatment

Supported by Absolute Anchorage – Case Report

Leczenie klasy II grupy 2 wspomagane zakotwieniem absolutnym

– opis przypadku

Department of Dentofacial Orthopedics and Orthodontics, Silesian Piasts University of Medicine in Wrocław,

Poland

Dent. Med. Probl. 2007, 44, 2, 275–280

ISSN 1644−387X

CLINICAL CASE

© Copyright by Silesian Piasts University of Medicine in Wrocław

and Polish Stomatological Association

According to orthodontic nomenclature, distal

position of first lower molars in relation to maxil−

lary ones, accompanied by retrusion of upper inci−

sors is qualified as class II/2. This type of malocc−

lusion may result from either skeletal abnormali−

ties and/or dento−alveolar discrepancies, which

determines selection of the treatment method.

Age, growth pattern, facial esthetics as well as

arch−length deficiency should also be considered

in the treatment planning. Therefore, in adole−

scents with class II/2 malocclusion coinciding

with moderate crowding (up to 9 mm) and arch−

−length deficiency, maxillary molar distalization is

usually indicated as a non−extraction treatment ap−

proach [1, 2]. The treatment of a class II malocc−

lusion without extraction requires posterior move−

ment of the maxillary dentition, anterior move−

ment of the mandibular dentition, or a combination

of both. Force moving molars backwards may have

its fulcrum on patient’s head and/or neck – when

a headgear is applied, or on premolars – when in−

traoral distalizing devices are used. Nevertheless,

disadvantages of these appliances have been widely

discussed in the literature [3–9]. Efficiency of extra−

oral traction is basically dependent on patient’s

compliance, whereas intraoral approach shows

Abstract

The paper describes a case of class II/2 malocclusion efficiently treated with Absoanchor

®

system of microscrews

(1.2 diameter and 6 to 8 mm long) placed into alveolar bone and used as anchorage for incisor intrusion and for

class I reestablishment. The microscrew implants were maintained firmly throughout the therapy. Overbite decre−

ase and distalization proceeded with any of adverse reciprocal effects of conventional biomechanics such as: me−

sial molar or premolar tipping, premolar elongation or flaring of incisors. En masse distal movement of the whole

upper dental arch after anterior tooth alignment apparently reduced the active treatment into 12 months, thus ma−

ximizing the efficacy of the treatment. It may be concluded, that microimplants supporting class II/2 treatment are

promising and beneficial solutions for either clinicians or patients (Dent. Med. Probl. 2007, 44, 2, 275–280).

Key words: microscrew implants, orthodontics, class II division 2 malocclusion, non−extraction treatment.

Streszczenie

Opisano przypadek klasy II/2 leczony skutecznie za pomocą systemu Absoanchor

®

– śrub o średnicy 1,2 mm, dłu−

gości 6–8 mm, implantowanych w wyrostek zębodołowy i pełniących rolę zakotwienia w intruzji zębów siecznych

i odtwarzaniu klasy I. Mikrośruby były stabilne podczas całej terapii. Nagryz pionowy i dystalizacja przebiegły bez

widocznych skutków ubocznych konwencjonalnej biomechaniki, takich jak: mezjoinklinacja zębów trzonowych

lub przedtrzonowych, wydłużenie zębów przedtrzonowych lub wychylenie zębów siecznych. Dystalizacja en masse

wszystkich zębów górnych po uszeregowaniu zębów przednich pozwoliła wyraźnie skrócić czas aktywnego lecze−

nia do 12 miesięcy, a tym samym maksymalnie je usprawnić. Można zatem twierdzić, że mikroimplanty wspoma−

gające leczenie klasy II/2 są obiecującym i korzystnym rozwiązaniem zarówno dla lekarza, jak i pacjenta (Dent.

Med. Probl. 2007, 44, 2, 275–280).

Słowa kluczowe: mikroimplanty, ortodoncja, klasa II grupa 2, leczenie nieekstrakcyjne.

undesired mesial movement of anchoring teeth

and flaring of incisors. In addition, molars after di−

stalization are usually tipped distally, since the for−

ce vector passes by their centre of resistance.

Elimination of adverse changes on the reactive

part is possible due to fix, extradental anchorage

produced by titan orthodontic screws, temporarily

implanted in alveolar cortical bone. They do not re−

quire osseointegration, therefore may be loaded

immediately; force value must not exceed 400 G,

whereas 180 G per side is sufficient for en masse

retraction [10]. Evidence−based literature [11] pro−

ves that loading of microimplants (cross−sectional

1.3 mm or less) with distalizing forces applied ne−

ar the canine, are transmitted through dental con−

tact points to the molars. Subsequently, the whole

dental arch freely moves backwards, since the li−

kelihood of root−microimplant−contact – certainly

limiting range of required distal displacement – is

diminished proportionally to screw−diameter de−

crease.

Among different orthodontic screw−systems

available on the Polish market only Absoanchor

®

(produced by Dentos

®

, supplied by Orto Trading

®

)

provides with tapered microimplants, therefore

their unique features were utilized in treatment of

presented class II/2 case.

Case Report

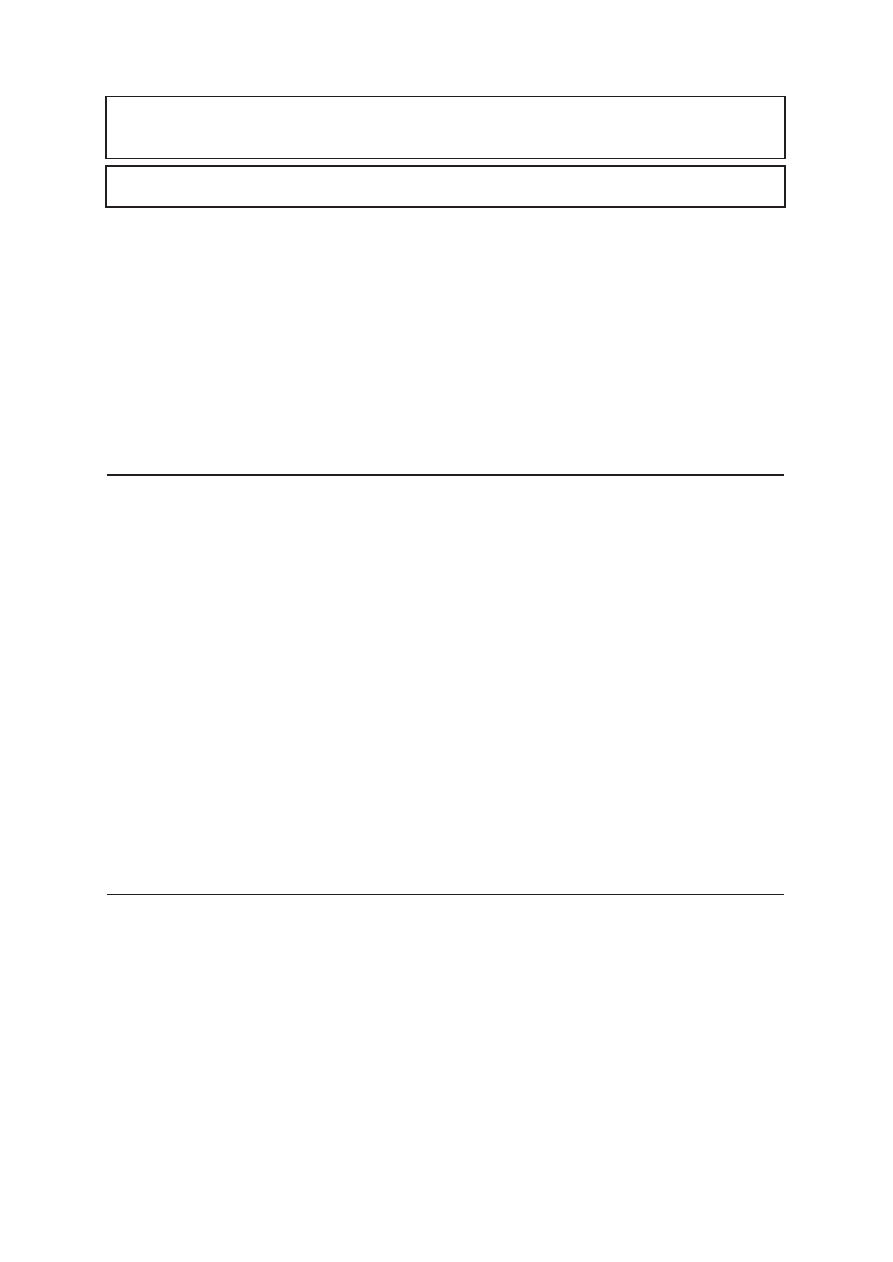

Patient L. S., 13−year−old, presented for ortho−

dontic treatment in December 2005. Her facial

profile displayed skeletal class II relationship:

B line−crossing the base of the upper lip and the

chin was angulated distally in relation to A line−

−crossing bases of the nose and the upper lip (Fig. 1).

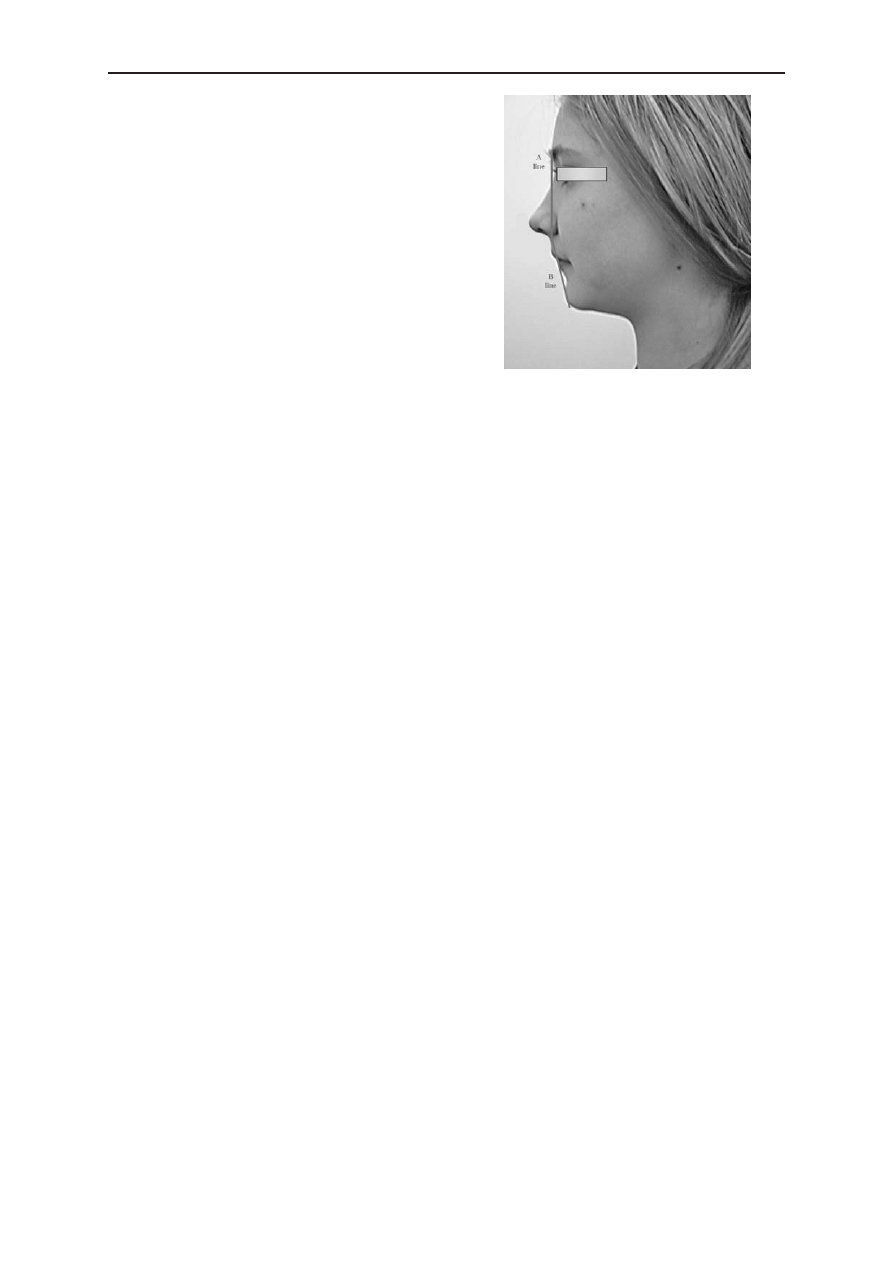

Intraorally she had an Angle class II (Fig. 2a–b)

and increased overbite (Fig. 2c). Cephalometric

analysis showed no significant abnormalities,

except high value of ANB angle (5.1

o

) – skeletal

component of class II, and retruded upper incisors

(1 + NA = 14

o

). Additional factors, such as young

patient’s age and merely –2 mm of dentoalveolar

discrepancy – all together called for nonextraction

treatment. It started from banding and bonding of

brackets with 0.018 slots in the upper arch; for le−

veling 0.016 round NiTi archwire with minimum

friction was applied (Low Force

®

, Forestadent

®

).

At this stage, a 7−mm−long microscrew – 1.2 dia−

meter – was placed between central incisors, under

the nasal spine, in medium position: 7 mm above

the archwire plane. Subsequently, upper incisors

were intruded with a force of 50 G generated by

a rectangular elastic thread (Superthread

®

, Den−

tos

®

), extending from the microimplant to the ma−

in archwire (Fig. 3). After 8 weeks bite−opening

was visible (Fig. 4), then lower round (0.016) Low

Force

®

was inserted in 0.018 slots of brackets.

0.016

×

0.022 Low Force

®

and 0.018 stainless ste-

el archwires respectively replaced the initial ones.

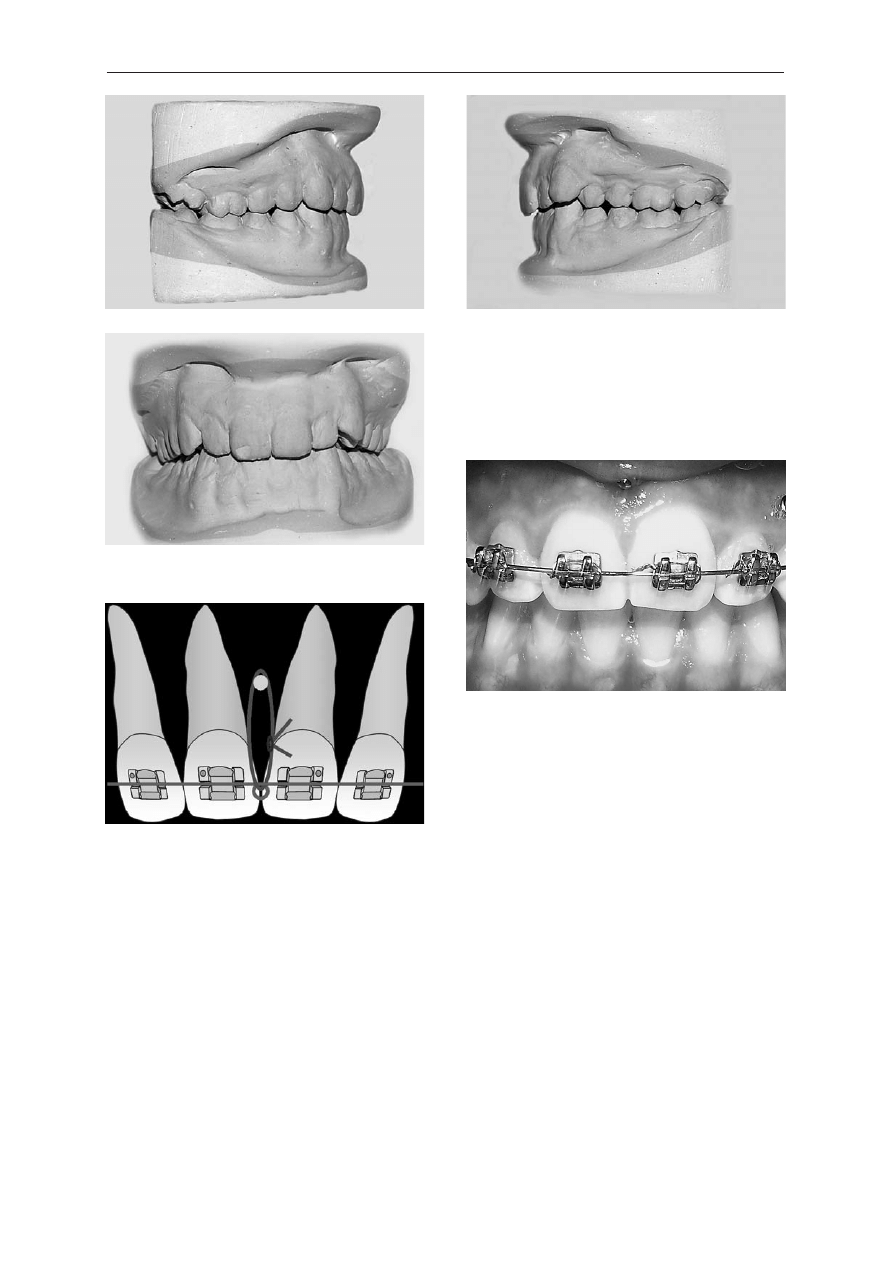

The next phase required implantation of two coni-

cal, 8-mm-long microscrews – 1.2 diameter – into

the vestibular, cortical bone, between roots of

upper second premolar and first molar, on either

sides. All hitherto used microimplants were trea-

ted as self-tapping ones: vertical 4-mm-long inci-

sion of oral mucosa and preparation of an oblique

canal with a pilot-drill (Fig. 5) preceded screw

tightening. Anatomy of the buccal alveolar surface

compelled vertical positioning of microimplants in

the borderline between low and high position –

5 mm above the archwire level. Consequently, the

distalizing force passing beneath the center of re-

sistance of the frontal teeth could have possibly in-

tensified initial retrusion of upper incisors. Such

undesired phenomena was prevented by extra

elongated hooks bent on the basic, 0.016

×

0.022

stainless steel archwire. Nevertheless, hooks 10-mm

-long displayed high tendency to bend distally,

therefore – in order to keep them upright – a stabi-

lizing, passive sectional archwire was utilized

(Fig. 6).

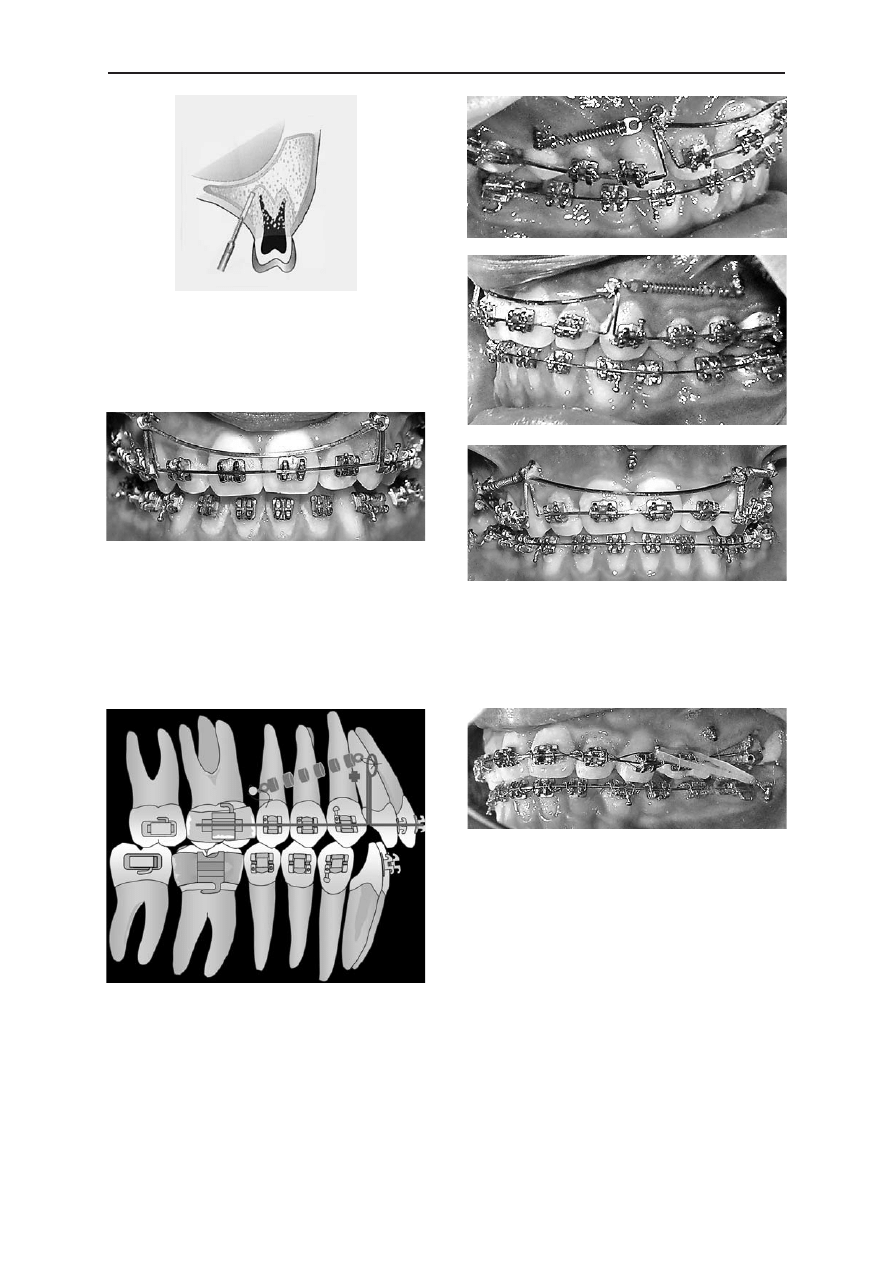

Lateral microimplants were loaded after 2 weeks

of soft tissue healing; 8−mm−long closed coil−

springs were stretched between screws and hooks

thus generating 180 G of distalizing force. Special

tiny holes in eye−lets of coil−springs (manufactu−

red by Dentos

®

) enabled tightening them firmly to

microscrews (Fig. 7). Six months later, molar and

canine class I relationships on both sides were re−

established (Fig. 8a–b), upper and lower midlines

coincided (Fig. 8c).

During finishing, for occlusion settling with−

out any side−effects on first lower molars, two mi−

J. A

NTOSZEWSKA

276

Fig. 1. Facial profile before treatment

Ryc. 1. Profil twarzy przed leczeniem

croscrews were implanted buccaly between roots

of first and second molars, on either sides of the

mandible. Implantation technique, suitable for

self−tapping screws, resembled one applied in the

maxilla. Two weeks later, microimplants were

loaded with 150 G of force per side, generated by

¼ medium elastics (Fig. 9) displacing whole man-

dible forward; finishing phase is still in progress.

Discussion

Conventional consecutive distal movement of

teeth, despite of its effectiveness, still brings a cer−

tain amount of anterior anchorage loss – mesial

movement of premolars contributes 20 to 40% of

the space created during distalization of molars;

furthermore distal tipping of the latter ones (rang−

ing from 4 to 14

o

) also becomes evident in routine

biomechanics [12, 13]. Intra−arch devices, such as

Keles Slider with NiTi coil−spring [14] or lingual

NiTi coil [15] successfully overcame the problem

of molar tipping, nevertheless both still provided

movement of single teeth against the device rather

than simultaneous retraction of the whole denti−

tion.

Search for stationary absolute anchorage have

demonstrated that implants utilized in prosthetics

were also applicable for orthodontic purposes. Pa−

latal implants supporting modified Distal Jet [16]

Class II Division 2 Treatment by Absolute Anchorage

277

Fig. 2. Dental casts before treatment:

a – right side, b – left side, c – en face

Ryc. 2. Modele przed leczeniem: a – strona prawa,

b – strona lewa, c – z przodu

Fig. 3. Scheme of Superthread

®

(0>) attached to main

archwire and passing through the hole in the head of

screw (

z

), thus loading the microimplant

Ryc. 3. Schemat nici Superthread

®

(0>) dowiązanej do

łuku podstawowego i przechodzącej przez otwór

w główce śruby (

z

), obciążającej w ten sposób mikro−

implant

Fig. 4. Treatment progress: apparent overbite decrease

Ryc. 4. Postęp leczenia: widoczne spłycenie nagryzu

pionowego

a

b

c

or Pendulum appliances [17], turned out to be re−

sistant against 250 G of distalizing force absolute−

ly adequate to provide en masse retraction. How−

ever, high cost, limited number of implantation

areas and necessity of delayed loading result in

cortical screws privilege over endosseous choice.

Sliding mechanics with the aid of the micro−

screw implant anchorage (MIA) and its applica−

tion for nonextraction treatment has not been wi−

dely discussed, although since screws have been

J. A

NTOSZEWSKA

278

Fig. 5. Scheme of pilot drilling and angulation

of the canal for microscrew−implant

Ryc. 5. Schemat prowadzenia wiertła pilotowego i na−

chylenia kanału dla mikrośruby

Fig. 6. Segmented archwire keeping hooks upright.

Noticeable symptoms of improper oral hygiene requi−

red professional re−training and plaque removal

Ryc. 6. Łuk odcinkowy pionizujący haczyki. Wyraźne

symptomy niewłaściwej higieny wymagały ponowne−

go profesjonalnego instruktażu i usunięcia złogów na−

zębnych

Fig. 7. Scheme of biomechanics applied for class II/2

treatment. Symbols:

®

– center of resistance,

z

– head of microimplants,

– closed coil spring,

}

– eyelet. Line displays archwire with the

customized hook

Ryc. 7. Schemat biomechaniki zastosowanej w lecze−

niu klasy II/2. Oznaczenia:

®

– centrum oporu,

z

– główka mikroimplantu,

– zwój sprężyny

zamkniętej,

}

– zaczep oczkowy. Linia oznacza łuk

podstawowy z indywidualnie dogiętym haczykiem

Fig. 8. Intraoral pictures after 12 months of treatment:

a – right side, b – left side, c – en face

Ryc. 8. Zdjęcia wewnątrzustne po 12 miesiącach

leczenia: a – strona prawa, b – strona lewa,

c – z przodu

Fig. 9. Class II elastics stretched between lower mi−

croscrew and hook of the canine−bracket, stabilizing

reestablished class I

Ryc. 9. Wyciągi klasy II rozpięte między dolną mikro−

śrubą i haczykiem zamka na kle, stabilizujące odtwo−

rzoną klasę I

a

b

c

introduced in clinical orthodontics [18] these pre−

sented the clinician with a versatile option. The

use of microscrews in the case reported enabled en

masse retraction of teeth, without any reciprocal

effect on the anchored unit; screws remained sta−

ble and did not show any mobility throughout the

treatment. Choice of self−tapping method of im−

plantation could have possibly been crucial for

firm fixation of screws: incision of gingiva and pi−

lot drilling prohibited either dragging of soft tissue

into screw−canal or excessive pressure during

screw tightening. By placing microscrew implants

at 30–40

o

to the long axes of the crowns, the api−

ces of the microscrew implants were kept apart

from the roots. Therefore, the possibility of dama−

ge to the roots was eliminated as well as a chance

that the roots of the teeth might have touched mi−

croscrew implants during retraction. The occlusal−

−gingival height of the microimplants and position

of the customized hooks together determined the

direction of the line of force relative to the center

of resistance, thus permitting predictable biome−

chanical control of the movements. The contact on

the crowns of teeth acted as a resistance to move−

ment, which created a counterclockwise moment

on the anterior teeth, resulting in their distal dis−

placement and proclination favorable in class II di−

vision 2 treatment.

Park [19] proved that ability to produce abso−

lute anchorage against which posterior teeth could

be retracted as a unit shorten treatment time due to

group movement of teeth, not to rapid tooth move−

ment possibly increasing risk of root resorption. It

was also true in the presented case were en masse

retraction of the whole dentition was achieved

after 6 months. Relation of microscrew to the

crown of the second premolar (Fig. 8a) displayed

efficiency and range of distal movement of the

upper teeth. Buccal crown torque and buccal fla−

ring bend prevented against undesired lingual tip−

ping and distal rotation reported in the literature

[20] as the side effects of a distalizing force ap−

plied on the vestibular side.

The author conclude that efficient distal move−

ment of upper molars is difficult to achieve co−

nventionally, since routine biomechanics enforces

either adverse anchorage loss or uncontrolled mo−

lar rotation and tipping. Furthermore, there is no

possibility to obtain dental unit withstanding si−

multaneous retraction of all teeth, so class II divi−

sion 2 treatment requires several, time−consuming

phases of distalization.

Ability to provide absolute anchorage for the

en masse distal bodily movement not only counte−

racts undesired movement but shortens the treat−

ment time distinctly, therefore nonextraction treat−

ment supported by the microscrew implants is be−

neficial for both clinicians and patients.

Class II Division 2 Treatment by Absolute Anchorage

279

References

[1] W

ONG

R.W.K.: Combined orthodontic–dentofacial orthopedic treatment of a Class II division 2 patient with seve−

re deep bite. J. Orthod. 2002, 29, 181–188.

[2] S

ELWYN

−B

ARNETT

B.J.: Rationale of treatment for Class II division 2 malocclusion. Br. J. Orthod. 1991, 18,

173–181.

[3] G

ULATI

S., K

HARBANDA

O.P., P

ARKASH

H.: Dental and skeletal changes after intraoral molar distalization with sec−

tional jig assembly. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1998, 114, 319–327.

[4] T

ANER

T.U., Y

UKAY

F., P

EHLIVANOGLU

M., C

AKIRER

B.: Comparative analysis of maxillary tooth movement pro−

duced by cervical headgear and Pend−X appliance. Angle Orthod. 2003, 73, 686–691.

[5] M

ATTHEWS

−B

RZOZOWSKA

T., K

AWALA

B., A

NTOSZEWSKA

J., G

OLUSIK

K.: Porównanie skuteczności dystalizacyjnej

wyciągu zewnątrzustnego oraz przerzutu podniebiennego. Dent. Med. Probl. 2003, 40, 373–376.

[6] P

AUL

L.D., O’B

RIEN

K.D., M

ANDALL

N.A.: Upper removable appliance or Jones Jig for distalizing first molars?

A randomized clinical trial. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2002, 5, 238–242.

[7] M

USE

D.S., F

ILLMAN

M.J., E

MMERSON

W.J., M

ITCHEL

R.D.: Molar and incisors changes with Wilson rapid molar

distalization. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1993, 104, 556–565.

[8] M

ATTHEWS

−B

RZOZOWSKA

T., A

NDRYCH

M.: Leczenie ortodontyczne aparatem MALU wad klasy II. Twój Prz.

Stomat. 2005, 5, 47–50.

[9] B

IELACZYC

A.: Zmiany w położeniu zębów po leczeniu aparatem Herbsta na szynach akrylowych u pacjentów

z tyłożuchwiem czynnościowym i zgryzem głębokim. Czas. Stomat. 2002, 55, 250–259.

[10] P

ARK

H.S.: Do miniscrews remain stationary under orthodontic forces? Korea J. Orthod. 2002, 32, 435–441.

[11] S

UNG

J.H., K

YUNG

H.M., B

AE

S.M., P

ARK

H.S., K

WON

O.W., M

C

N

AMARA

J.A.: Biomechanical considerations in

microimplant anchorage. In: Microimplants in Orthodontics. Eds.: Sung J.H., Kyung H.M., Bae S.M., Park H.S.,

Kwon O.W., McNamara J.A., Dentos, Daegu 2006, 63–81.

[12] B

OLLA

E., M

URATORE

F., C

ARANO

A., B

OWMAN

S.J.: Evaluation of maxillary molar distalization with the distal jet:

a comparison with other contemporary methods. Angle Orthod. 2002, 72, 481–494.

[13] B

YLOFF

F.K., D

ARENDELILER

M.A.: Distal molar movement using pendulum appliance. Part 1: clinical and radio−

logical evaluation. Angle Orthod. 1997, 67, 249–260.

[14] K

ELES

A.: Maxillary unilateral molar distalization with sliding mechanics: a preliminary investigation. Eur. J.

Orthod. 2001, 23, 507–515.

[15] B

ONDEMARK

L.: A comparative analysis of distal maxillary molar movement produced by a new lingual intra−arch

Ni−Ti coil appliance and a magnetic appliance. Eur. J. Orthod. 2000, 22, 683–695.

[16] K

ARCHER

H., B

YLOFF

F.K., C

LAR

E.: The Graz implant supported pendulum, a technical note. J. Cranio−Maxillo−

fac Surg. 2002, 30, 87–90.

[17] K

ARAMAN

A.I., B

ASCIFTCI

F.A., P

OLAT

O.: Unilateral distal molar movement with an implant−supported distal jet

appliance. Angle Orthod. 2002, 72, 167–174.

[18] C

REEKMORE

T.D., E

KLUND

M.K.: The possibility of skeletal anchorage. J. Clin. Orthod. 1983, 17, 266–269.

[19] P

ARK

H.S.: The skeletal cortical anchorage using titanium microscrew implants. Korea J. Orthod. 1992, 29,

699–705.

[20] P

ARK

H.M., K

WON

T.G., S

UNG

J.H.: Nonextraction treatment with microscrew implants. Angle Orthod. 2004, 74,

539–549.

Address for correspondence:

Joanna Antoszewska

Department of Dentofacial Orthopedics and Orthodontics

Silesian Piasts University of Medicine

Krakowska 26

50−425 Wrocław

Poland

Tel.: +48 71 784 02 99

E−mail: joanna.antoszewska@stomatologia.com

Received: 10.01.2007

Revised: 26.03.2007

Accepted: 31.05.2007

Praca wpłynęła do Redakcji: 10.01.2007 r.

Po recenzji: 26.03.2007 r.

Zaakceptowano do druku: 31.05.2007 r.

J. A

NTOSZEWSKA

280

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

17.09.08-Scenariusz zajęć dla klasy II-Dodawanie i odejmowanie do 20, Konspekty

PRZYKŁADOWE TEKSTY PISANIA Z PAMIĘCI DLA KLASY II

Elektroinstalator 2009 06 koordynacja ochronników klasy I [B] i II [C]

plan wynikowy dla klasy II

scenariusz lekcji klasy II kwiaty, KLASY I - III, Scenariusze kl. - III

Sprawdzian z edukacji polonistycznej dla klasy II, szkoła, j,polski, sprawdziany

23.09.08-Scenariusz zajęć dla klasy II-Podziwiamy ogrody kwiatowe, Konspekty

Konspekt zajęć zintegrowanych dla klasy II 23.03, Scenariusze i konspekty

LECZENIE CUKRZYCY II

SPRAWDZIAN DLA KLASY II dodawanie i odejmowanie w zakresie , październik

TEST DLA KLASY II LICEUM

ROZKŁAD MATERIAŁU DLA KLASY II GIMNAZJUM ZAJ INDYWID 11 12

PROGRAM Zajęc z muzyki dla klasy II, pliki zamawiane, edukacja

Bawimy się w lustra – na podstawie „Lustereczka” D Gellner (konspekt zajęć dramowych dla klasy II)

5256, Scenariusz zajęć z edukacji środowiskowo-polonistycznej dla klasy II

Regulamin klasy II c

więcej podobnych podstron