Childhood Maltreatment and Difficulties in Emotion Regulation: Associations with

Sexual and Relationship Satisfaction among Young Adult Women

Alessandra H. Rellini

Department of Psychology, University of Vermont

Anka A. Vujanovic

National Center for PTSD–Behavioral Science Division, VA Boston Healthcare System,

Boston University School of Medicine

Myani Gilbert and Michael J. Zvolensky

Department of Psychology, University of Vermont

This study examined relations among childhood maltreatment, difficulties in emotion

regulation, and sexual and relationship satisfaction among young adult women reporting

current involvement in committed, romantic relationships. A sample of 192 women (ages

18–25) completed self-report questionnaires as part of an Internet-based survey. It was

hypothesized that severity of childhood maltreatment and difficulties in emotion regulation

would each independently and negatively predict (a) sexual satisfaction, (b) relationship

intimacy, and (c) expression of affection within the context of the relationship. Furthermore,

it was hypothesized that greater emotion regulation difficulties would moderate the effects of

childhood maltreatment on these sexual and relationship variables (i.e., sexual satisfaction,

relationship intimacy, and expression of affection). Findings suggest that difficulties in emo-

tion regulation demonstrated an incremental effect with regard to sexual satisfaction, but not

with intimacy and affection expression. In contrast to predictions, no significant interactive

effects were documented. Clinical implications and future directions related to this line of

inquiry are discussed.

There is a high prevalence of relational and sexual

problems among adult women exposed to childhood

maltreatment, defined as childhood sexual abuse,

physical abuse, or neglect (Davis, Petretic-Jackson, &

Ting, 2001; Fromuth, 1986; Loeb et al., 2002; Meston,

Heiman, Trapnell, & Carlin, 1999; Rellini & Meston,

2007; Scholerdt & Heiman, 2003). The most commonly

reported sexual and relationship problems for women

with a history of childhood maltreatment include

inhibited sexual desire, lower levels of sexual satisfac-

tion, difficulties becoming sexually aroused or reaching

orgasm, difficulties developing emotional intimacy with

a partner, and interpersonal aggression (DeSilva, 2001;

Lewis et al., 2010; Rellini & Meston, 2007).

As not all individuals with a history of childhood

maltreatment report sexual or relational problems in

adulthood (Leonard & Follette, 2002; Loeb et al.,

2002; Rellini & Meston, 2007), increasing our under-

standing

of

malleable

(changeable)

vulnerabilities

remains a fecund area of intellectual and clinical pursuit.

There is increasing evidence that emotion regulation

offers promise for advancing our understanding of

potential risk and maintenance factors for sexual and

relational problems (Rellini, Vujanovic, & Zvolensky,

2010). Emotion regulation is a promising construct in

this context; it encapsulates an individual’s understand-

ing and regulation of emotional responses (Cole,

Michel, & Teti, 1994; Mennin, 2004; Salovey, Mayer,

Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, 1995). Gratz and Roemer

(2004) developed an empirically grounded assessment

instrument entitled the Difficulties in Emotion Regula-

tion

Scale

(DERS),

which

measures

emotional

regulation from a multidimensional framework. The

DERS assesses several facets of emotion regulation,

including difficulties relevant to an individual’s (a)

acceptance of emotional responses, (b) ability to engage

This research was supported by the McNeil Prevention and

Community Psychology Fund and the Undergraduate Research

Endeavour Competitive Award. The views expressed here are those

of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Depart-

ment of Veterans Affairs or the McNeil Fund. We thank Sarah P.

Roberts for her substantial contribution with data collection.

Correspondence should be addressed to Alessandra H. Rellini,

Department of Psychology, University of Vermont, John Dewey Hall,

2 Colchester Ave., Burlington, VT 05405. E-mail: arellini@uvm.edu

JOURNAL OF SEX RESEARCH, 49(5), 434–442, 2012

Copyright # The Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality

ISSN: 0022-4499 print=1559-8519 online

DOI: 10.1080/00224499.2011.565430

in goal-directed behavior under distress, (c) ability to

control impulsive behaviors when distressed, (d) aware-

ness of emotional experiences, (e) access to emotion

regulation strategies, and (f) emotional clarity.

It has been theorized that emotion regulation difficul-

ties are the product of the interaction between biological

vulnerabilities and environmental factors (Linehan,

1993; Thompson, 1994). As part of the environmental fac-

tors, an invalidating, abusive, or neglectful childhood

environment wherein children do not learn adaptive ways

of coping with aversive emotions has been hypothesized

as a risk factor for the development of emotion dysregula-

tion (Linehan, 1993). Such emotion regulatory difficulties

may be formed and=or maintained via social learning

contexts and relationships in adolescence and early adult-

hood (Kim, Pears, Capaldi, & Owen, 2009). It is possible

that greater levels of emotion regulation difficulties may

exacerbate the effects of childhood maltreatment on sex-

ual and relationship problems in adulthood (Rellini,

2008). For example, women with histories of child mal-

treatment may be more likely to manifest sexual and

relationship problems if they also experience high levels

of difficulties regulating emotions. In contrast, emotion

regulation skills may decrease the negative effects of child-

hood maltreatment in terms of sexual and relationship

problems (e.g., Rellini et al., 2010).

There is a dearth of empirical literature devoted to

the examination of associations between emotion regu-

lation and sexual and relationship functioning. In the

only published empirical study to date, Rellini and

colleagues (2010) documented significant (negative)

incremental associations between emotion regulation

difficulties, as indexed by the DERS, and sexual satis-

faction, even after controlling for theoretically relevant

variables (i.e., posttraumatic stress symptom severity,

negative affectivity, anxiety sensitivity, and daily ciga-

rette consumption). This investigation relied on a

relatively small sample of 43 men and women, with a

history of varied types of trauma exposure. The sample

also was limited in that it focused exclusively on smo-

kers. There is a need to replicate and extend such work

to a more diverse population in a number of specific

ways. First, it is important to replicate the previously

documented findings among larger samples of indivi-

duals who are currently engaged in committed roman-

tic relationships independently from their smoking

behavior, so as to increase the generalizability of

results and improve accuracy of relationship function-

ing reports. Second, since men and women have been

shown to manifest unique sexual and relationship func-

tioning problems (Lewis et al., 2010; Parish et al.,

2007), it is important to examine these relations using

a gender-specific within-subjects design so as to attain

a clearer understanding of variables among men and

women, independently. Third, Rellini et al. (2010)

documented varied types of trauma exposure among

participants, thus impeding specific interpretations of

the effects of certain types of trauma (e.g., childhood

maltreatment).

Together, this investigation sought to replicate and

extend extant findings among a sample of young adult

women, currently involved in committed romantic rela-

tionships and reporting varying degrees of childhood

maltreatment. First, it was hypothesized that childhood

maltreatment and difficulties in emotion regulation

would be significantly (negatively) correlated with sexual

and relationship satisfaction. Second, it was hypothe-

sized that severity of childhood maltreatment and diffi-

culties in emotion regulation would each incrementally

(independently) and negatively predict (a) sexual satis-

faction, (b) relationship intimacy, and (c) expression of

affection within the context of the relationship over

and above the variance accounted for by age and

relationship duration. Third, it was hypothesized that

greater emotion regulation difficulties would interact

with the effects of childhood maltreatment on these sex-

ual and relationship variables (i.e., sexual satisfaction,

relationship intimacy, and expression of affection). This

prediction was driven by the perspective that childhood

maltreatment may, theoretically, have the most deleteri-

ous interpersonal effects when co-occurring with greater

difficulties in regulating emotional states.

Method

Participants

Participants were 192 young adult women (M

age

¼

21.8, SD

¼ 3.7; observed range ¼ 18–25), recruited from

online advertisements posted on social networking

websites (see the Procedure section for details). Parti-

cipants were included in the study if they self-identified

as (a) female, (b) between the ages of 18 and 25, (c)

non-virgin, (d) U.S. citizen, and (e) English speaking. A

total of 596 women completed the online screener between

June and October 2009, and 218 qualified and enrolled in

the study and started questionnaire completion. A total of

192 women completed all questionnaires. Therefore,

analyses were based on 88% (N

¼ 192) of the women

who qualified for the study. No statistically significant

group differences were evident between women who com-

pleted the study and women who completed only the first

demographics questions (n

¼ 26) in terms of age, edu-

cation level, sexual orientation, relationship length, stu-

dent status, or race and ethnicity.

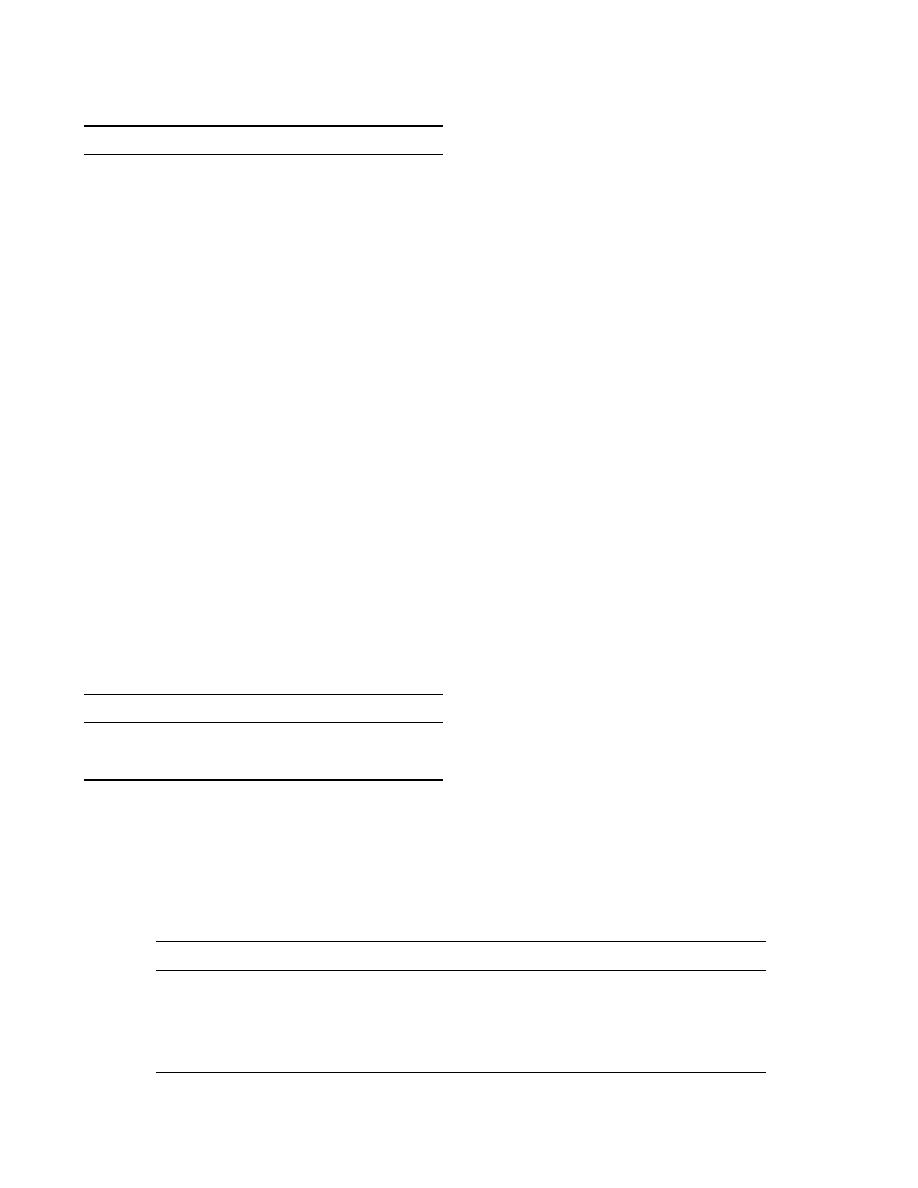

As illustrated in Table 1, participants were predomi-

nantly Caucasian women (90%), who had completed at

least some college (89%). Based on the Kinsey scale

(Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948), the sample reported

large variability in terms of sexual orientation, with

approximately 26% not identifying as exclusively or pre-

dominantly heterosexual. With regard to relationship

status at the time of the study, approximately 60%

EMOTION DYSREGULATION AND SEXUALITY

435

(n

¼ 116) of participants reported being involved in a

committed relationship or married, whereas the remain-

ing 41% (n

¼ 79) of participants reported either dating

one partner or being in a relationship that was not com-

mitted. A small minority of participants (9%; n

¼ 17)

reported being in a relationship with a woman. The mean

relationship length reported was 3.7 years (SD

¼ 2.3).

One hundred-three participants (54%) reported at least

one type of childhood maltreatment, and 10 (5%) scored

above the normative cutoff for all five types of childhood

maltreatment (i.e., emotional neglect, physical neglect,

emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse), as

measured by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

(CTQ; see the Measures section for details; Bernstein,

Fink, Handelsman, & Foote, 1994). Twenty-four parti-

cipants (13%) scored above the normative cutoff for sex-

ual abuse. Table 2 illustrates more details on frequency of

childhood maltreatment in the sample. Co-occurrence of

types of abuse was common, with only eight participants

(4%) meeting criteria exclusively for sexual abuse, six

participants (3.1%) meeting criteria exclusively for physi-

cal abuse, and none meeting criteria exclusively for

emotional abuse or emotional neglect.

Measures

Demographics.

Questions about age, education (i.e.,

high school graduate or less vs. some college or more),

student status (i.e., currently a student: yes or no), and

ethnicity (i.e., African American or Black, Hispanic or

Latin American, Asian or Asian American, Native

Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska

Native, Euro-American or White, multiracial, and

‘‘other’’) were asked to characterize the sample. Addition-

ally, household income was measured separately for

people self-identifying as dependent or non-dependent

for tax purposes. Finally, the Kinsey scale (Kinsey et al.,

1948) was used to assess sexual orientation. This is a

seven-point (0–6) Likert scale that conceptualizes sexual

orientation as ranging continuously from exclusively

heterosexual (0) to exclusively homosexual (6). Relation-

ship characteristics measured in the study include

relationship status (dating, in a non-committed rela-

tionship, or married=committed relationship), length of

relationship (months), and partner’s gender.

Table 2.

Childhood Maltreatment Scores

Trauma Type

M

SD

Minimum–Maximum

Cutoff

n > cutoff; n (%)

a

CTQ-total

40.5

15.6

25–96

—

—

Emotional neglect

9.9

4.5

5–25

15

21 (10.9)

Emotional abuse

10.0

4.8

5–24

10

51 (26.6)

Physical neglect

6.7

2.7

5–19

8

27 (14.1)

Physical abuse

7.2

3.7

5–23

8

27 (14.1)

Sexual abuse

7.0

4.7

5–25

8

24 (12.5)

Note. CTQ

¼ Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein, Fink, Handelsman, & Foote, 1994).

a

Cutoff based on specificity and sensitivity scores (Walker et al., 1999).

Table 1.

Demographic and Relationship Characteristics for

All Participants in the Sample

Variable

n

%

Education

High school graduate or less

25

13.0

Some college or more

171

89.0

Currently a student

Yes

102

53.1

Ethnicity

African American or Black

6

3.1

Hispanic or Latin American

11

5.7

Asian or Asian American

7

3.6

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

1

0.5

American Indian or Alaska Native

5

2.6

Euro-American or White

173

90.1

Multiracial

11

5.7

Other

3

1.5

Sexual orientation (Kinsey scale)

0

93

48.4

1

49

25.5

2

20

10.4

3

10

5.2

4

6

3.1

5

5

2.6

6

6

3.1

Other

7

3.6

Relationship status

Single=dating

79

41.1

Married=committed relationship

116

60.4

Length of current relationship

0–6 months

45

23.4

6–12 months

30

15.6

1–2 years

31

16.1

3–5 years

39

20.3

5–10 years

6

3.1

Gender of current partner

Male

151

78.6

Female

17

8.9

M

SD

Relationship length (years)

3.7

2.3

Annual income=year for non-dependent

a

$34,700

$21,600

Family income=year for dependent or student

b

$105,000

$83,700

a

Participants self-identified as non-students and non-dependent based

on taxes filed the previous year.

b

Participants self-identified as either full-time students or dependent

based on taxes filed the previous year.

RELLINI, VUJANOVIC, GILBERT, AND ZVOLENSKY

436

CTQ (Bernstein et al., 1994).

The CTQ is a 28-item

self-report measure on which respondents indicate,

using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never

true) to 5 (very often true), their childhood experiences

of maltreatment—a construct indexed along five domains:

(a) Emotional Abuse, (b) Physical Abuse, (c) Sexual

Abuse, (d) Physical Neglect, and (e) Emotional Neglect

(Bernstein et al., 1994). The test–retest reliability of the

CTQ, over a two- to six-month period, has ranged from

r

¼ .79 to r ¼ .95; and convergent and discriminant val-

idity was determined to be adequate (Bernstein et al.,

1994). Overall internal consistency of the entire measure

was high (a

¼ .91; Scher, Stein, Asmundson, McCreary,

& Forder, 2001). A cutoff for each domain was used based

on findings from Walker et al. (1999), indicating that a

score of 8 for Physical Abuse, Physical Neglect, and Sex-

ual Abuse; a score of 10 for Emotional Abuse; and a score

of 15 for Emotional Neglect were sensitive and specific

scores to accurately identify individuals with these specific

types of abuse as assessed by experts in the field of trauma

(Walker et al., 1999). These cutoffs were utilized for a

description of the childhood maltreatment reported by

the sample. The continuous measure for severity of abuse

(CTQ) was the main variable in the analyses. In this study,

internal consistency was a

¼ .88, a ¼ .95, and a ¼ .90 for

Physical, Sexual, and Emotional Abuse, respectively;

and a

¼ .87 and a ¼ .77 for Emotional and Physical

Neglect, respectively. Consistent with past work (Rellini

et al., 2010), the CTQ-total score (logarithmic transform-

ation) was utilized as a measure of childhood maltreat-

ment severity in the analyses.

DERS (Gratz & Roemer, 2004).

The DERS is a

36-item self-report measure on which respondents indi-

cate, on a five-point Likert-style scale ranging from 1

(almost never) to 5 (almost always), how often each item

applies to them (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). The DERS is

multidimensional in that it is comprised of 6 factors in

addition to a total score. These factors include (a) Non-

acceptance of Emotional Responses, (b) Difficulties

Engaging in Goal-Directed Behavior, (c) Impulse Con-

trol Difficulties, (d) Lack of Emotional Awareness

(Aware), (e) Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Stra-

tegies, and (f) Lack of Emotional Clarity (Clarity). The

DERS has high levels of internal inconsistency (a

¼ .93;

Gratz & Roemer, 2004) and adequate test–retest

reliability over a four- to eight-week period (r

¼ .88;

Gratz & Roemer, 2004). The DERS-total sum score

represents a global emotional dysregulation composite

(Gratz & Roemer, 2004), and, in this study, it showed

adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s a

¼ .89).

Sexual Satisfaction Scale (SSS; Meston & Trapnell,

2005).

The SSS is a 30-item questionnaire that measures,

on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly

disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), five separate domains of sex-

ual satisfaction: (a) ease and comfort discussing sexual and

emotional issues (Communication); (b) compatibility

between partners in terms of sexual beliefs, preferences,

desires, and attraction (Compatibility); (c) contentment

with emotional and sexual aspects of the relationship (Con-

tentment), (d) personal distress concerning sexual prob-

lems (Personal Distress); and (e) distress regarding the

impact of sexual problems on partners and relationships

at large (Relational Distress). The five domains have

shown

acceptable

internal

consistency

(Cronbach’s

a

.74) and test–retest reliability after four to five weeks

(r

¼ .5879). The SSS reliably differentiated between

women with and without sexual dysfunction on each of

the domains and total scores (Meston & Trapnell, 2005).

In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the total score was .80.

Network of Relationships Inventory: Social Provisions

Version–Revised (NRI–SPV–R; Furman & Buhrmester,

2009).

This version of the NRI–SPV–R comprises 36

items on which respondents indicated, using a five-point

Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (little or none) to 5 (the

most), their levels of relationship satisfaction as indexed

by 10 factors (Furman & Buhrmester, 2009). Based on

research suggesting that the association between sexual

function and emotion regulation may be mediated by dif-

ficulties in developing emotional connections with part-

ners (Fruzzetti & Iverson, 2004; Linehan, 1993; Rellini

et al., 2010), only the Intimacy and Affection factors were

considered for this study. The Intimacy factor was com-

prised of items relevant to how much the person shares

with her partner (e.g., ‘‘How much do you share your

secrets and private feelings with this romantic partner?’’).

The Affection factor included items related to how much

the person feels loved by her partner (e.g., ‘‘How much

does this romantic partner have a strong feeling of affec-

tion [loving or liking] toward you?’’). This scale can be

used to assess the quality of a romantic relationship.

The scale has shown high internal consistency for the

domains of Intimacy (a

¼ .86) and affection (a ¼ .91) with

romantic partners (Furman & Buhrmester, 2009). In this

investigation, internal consistency was similarly high,

with a

¼ .89 for Intimacy and a ¼ .95 for Affection.

Procedure

Participants were recruited using online advertise-

ments posted on social networking websites, such as

Facebook.com

1

, Craigslist.org, and Backpage.com

1

,

indicating that (a) the online study was about sexual

health, and (b) people who completed the study would

be entered in a raffle to win $100 (with a 1 in 30 chance

of winning). An online site, PsychData

1

, was used for

anonymous and confidential collection of data from

recruited participants. Prior to beginning the online sur-

vey, interested individuals read a short explanation of

the study and clicked on a link leading to an online

screener. This eligibility screener assessed for age, gender

identity, virginity status, citizenship and language

EMOTION DYSREGULATION AND SEXUALITY

437

fluency. After completing the online screener, parti-

cipants received a more in-depth description of the study

and were informed that the questionnaires would take

between 30 and 45 min to complete. Participants were

not permitted to stop data entry and continue at a later

time. At the conclusion of the study, participants

received a random participation identification code that

they were asked to send to the researcher to be entered

into the monetary raffle for possible compensation.

Data Analytic Plan

First, zero-order correlations were computed to evaluate

associations

among

theoretically

relevant

variables.

Second, a series of three-step hierarchical regressions were

conducted to assess the main and interactive effects of child-

hood trauma severity (CTQ-total) and difficulties in emo-

tion regulation (DERS-total) with regard to the following

criterion variables: (a) sexual satisfaction (SSS), (b)

relationship intimacy satisfaction (NRI–SPV–R Intimacy

subscale), and (c) relationship affection satisfaction

(NRI–SPV–R Affection subscale). Age and relationship

duration were entered as covariates at Step 1 of the

regression models in an effort to account for developmental

differences in the sample, the main effects of childhood

trauma severity (CTQ-total) and difficulties in emotion

regulation (DERS-total) were entered at Step 2, and the

interactive effect of childhood trauma severity by difficult-

ies in emotion regulation (CTQ

DERS-total) was entered

at Step 3. DERS-total and CTQ-total were mean-centered.

Since CTQ scores were skewed, logarithmic transforma-

tions were applied before mean centering.

Results

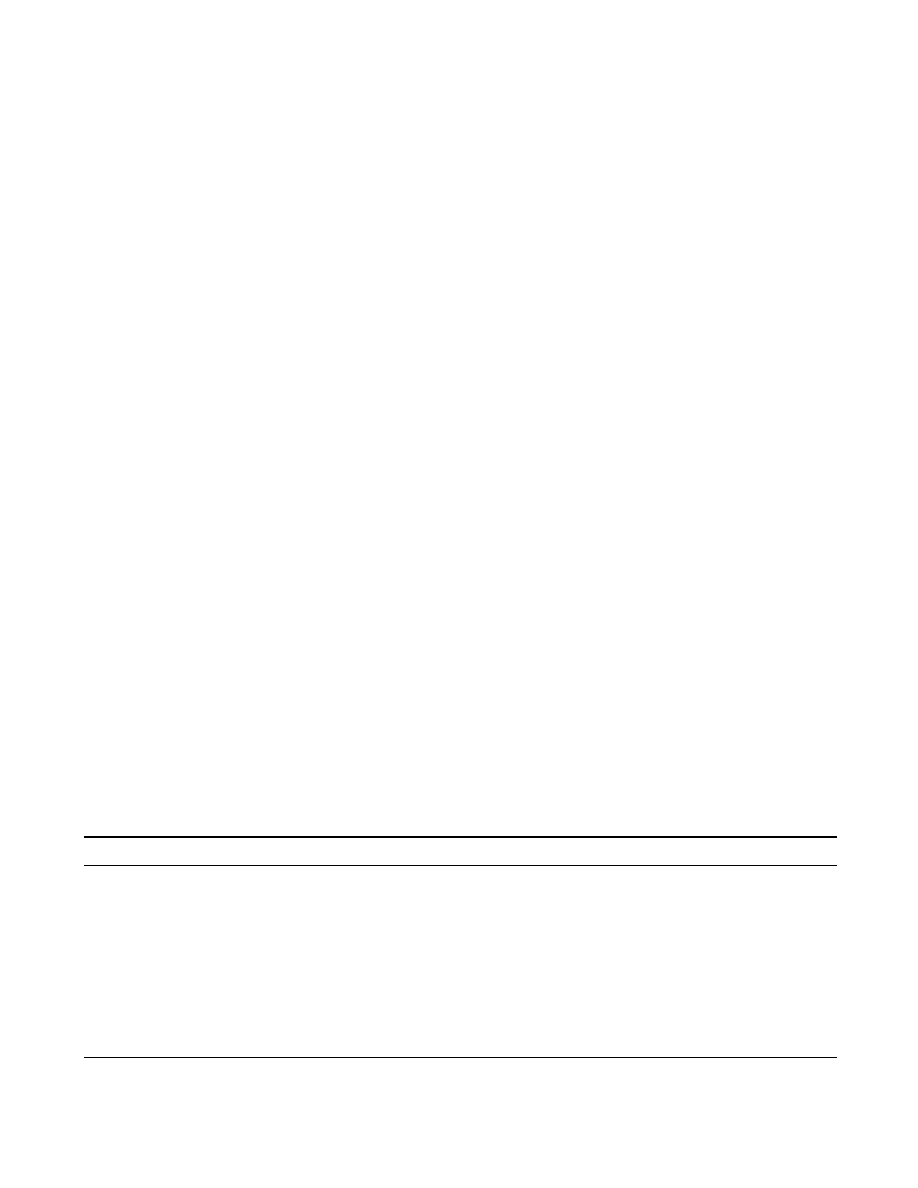

Correlations between Emotion Dysregulation,

Relationship Variables, and Childhood Trauma

Table 3 presents a summary of zero-order correlations

and descriptive data for theoretically relevant variables.

Age and relationship length were not significantly

correlated with the DERS subscales or the CTQ-total

score; however, they were significantly correlated with

the dependent variables used in the subsequent analy-

ses: SSS, NRI–SPV–R Affection, and NRI–SPV–R

Intimacy. Overall, both age and relationship length were

negatively correlated with SSS (r

¼ .18 and .27,

respectively) and NRI–SPV–R Affection (r

¼ .26 and

.21, respectively). Age was significantly and negatively

correlated with NRI–SPV–R Intimacy (r

¼ .17). These

results indicate that older participants reported less sex-

ual satisfaction, less affection, and less intimacy, while

individuals reporting a longer relationship scored lower

in sexual satisfaction and affection.

As illustrated in Table 3, CTQ-total was signifi-

cantly and negatively associated with SSS, r

¼ .18,

p < .05; but not NRI–SPV–R Intimacy and NRI–

SPV–R Affection, suggesting that individuals reporting

more severe forms of maltreatment reported lower

sexual satisfaction. Also, CTQ-total was significantly

and positively associated with DERS-total (r

¼ .28,

p < .01),

as

well

as

all

DERS

subscales

(range

r

¼ .1527, p < .05), with the exception of DERS-

Aware and DERS-Clarity (ps > .05). These findings

indicate that individuals with more severe forms of

childhood maltreatment reported more difficulties in

emotion regulation.

Consistent with our hypotheses of greater sexual

and relationship difficulties for individuals who have

more emotion dysregulation, DERS-total was signifi-

cantly and negatively associated with SSS (r

¼ .29,

p < .01). Yet, in contrast to predictions, DERS-total

was not significantly associated with the NRI–SPV–R

Intimacy or Affection. DERS-Aware and DERS-

Clarity subfactors demonstrated significant correlations

with SSS (r

¼ .22 and .36, respectively; p < .01),

NRI–SPV–R Intimacy (r

¼ .21 and .29; respectively,

p < .01), and NRI–SPV–R Affection (r

¼ .19 and

.25, p < .01).

Table 3.

Zero-Order Correlations and Descriptive Characteristics for All Targeted Variables

Variable

CTQ-Total

Age

Relationship Length

SSS

Intimacy

Affection

M (SD)

DERS-Non-acceptance

.26

.09

.20

.02

.03

14.2 (5.8)

DERS-Goals

.15

.11

.03

.13

.06

15.3 (4.8)

DERS-Impulse

.27

.07

.17

.07

.09

12.4 (5.2)

DERS-Aware

.08

02

.22

.21

.19

13.4 (4.6)

DERS-Strategies

.22

.11

25

.01

05

18.7 (7.0)

DERS-Clarity

.10

.05

.36

.29

.25

11.1 (3.8)

DERS-total

.28

.10

.29

.07

.13

85.0 (22.2)

CTQ-total

—

<

.01

.18

.12

.07

1.58 (0.15)

Age

<

.01

—

.18

.17

.26

21.7 (3.3)

Relationship length

.05

.15

.27

.13

.21

3.7 (2.3)

M

1.58

21.7

3.7

89.3

11.3

12.4

—

SD

0.15

3.3

2.3

19.9

3.3

3.1

Note. Intimacy and affection are subscales of the Network of Relationships Inventory: Social Provisions Version–Revised. CTQ-total is log

transformed. CTQ

¼ Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; SSS ¼ Sexual Satisfaction Scale; DERS ¼ Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale.

p < .05.

p < .01.

RELLINI, VUJANOVIC, GILBERT, AND ZVOLENSKY

438

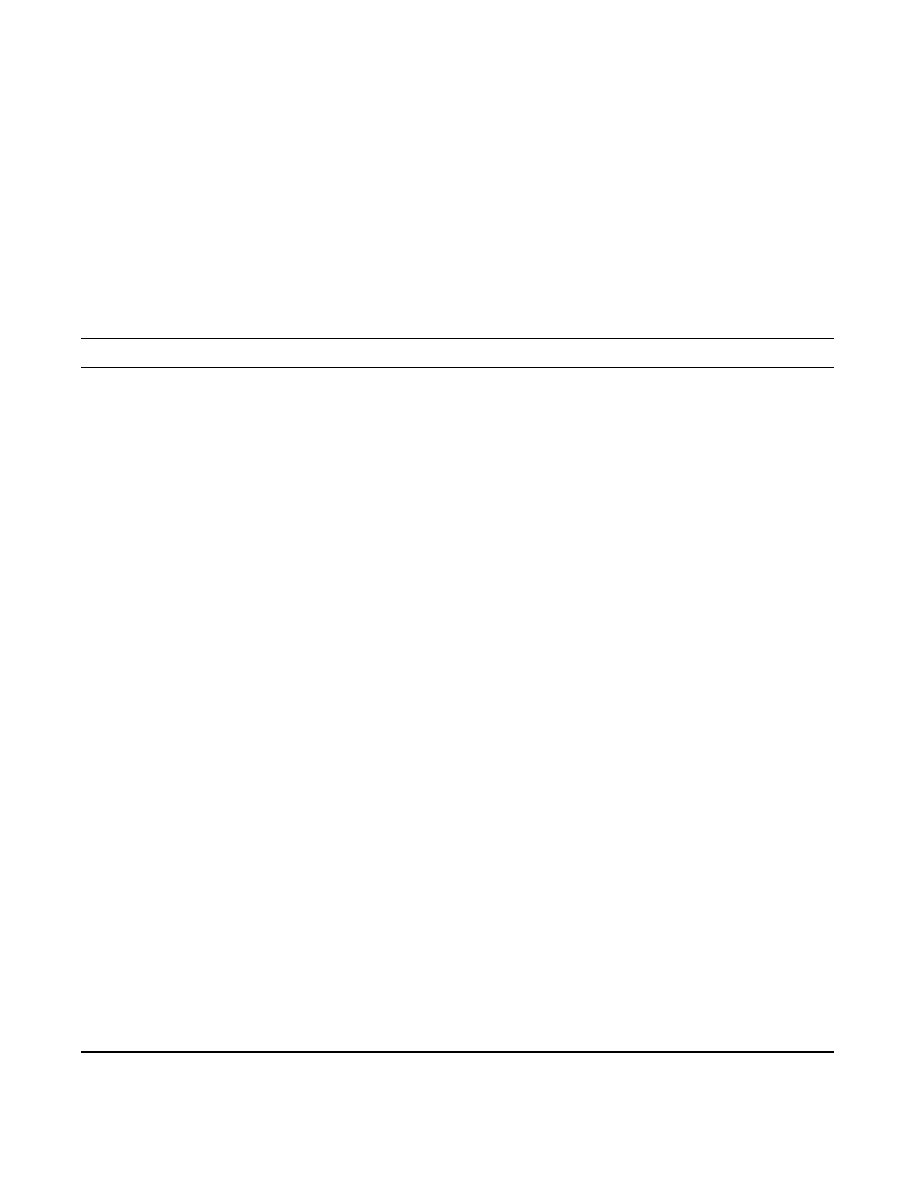

Childhood Trauma and Emotion Dysregulation

Predicting Sexual Satisfaction and Relationship

Variables

Table 4 illustrates the results for the hierarchical

regressions.

Sexual satisfaction (SSS).

Step 1 accounted for a

statistically significant 10% of variance, F(2, 159)

¼

8.81, p < .001; both age (b

¼ .20, p < .05) and relation-

ship length (b

¼ .25, p < .01) were significant predic-

tors. Step 2 of the model contributed 9% of unique

variance, DF(2, 157)

¼ 8.20, p < .001. In partial support

of our hypotheses that both emotion dysregulation

and childhood trauma would independently contribute

to sexual satisfaction, DERS-total, but not CTQ-total,

emerged as a significant incremental predictor in Step

2 (b

¼ .27, p < .01). Finally, inconsistent with our pre-

diction,

the

interactive

effect

of

CTQ-total

DERS-total, entered at Step 3 of the model—DF(1,

156)

¼ 1.03—was not a significant predictor of sexual

satisfaction.

Table 4.

Regression Statistics for Sexual Satisfaction, Relationship Intimacy, and Affection Regressed on Age, Severity of Childhood

Maltreatment (CTQ), Difficulties in Regulating Emotions (DERS), and the Interaction Between CTQ and DERS

Criterion Variable

DF

DR

2

b

t

p

s-r

2

Sexual satisfaction (SSS)

Step 1

8.81

0.10

Age

0.20

2.59

.010

.04

Relationship length

0.25

3.24

.001

.06

Step 2

8.20

0.09

Age

0.16

2.23

.027

.03

Relationship length

0.23

3.19

.002

.05

DERS-total

0.27

3.53

.001

.06

CTQ-total

0.07

0.94

.349

>

.01

Step 3

1.03

0.01

Age

0.15

2.10

.037

.02

Relationship length

0.24

3.28

.001

.06

DERS-total

0.99

1.07

.170

.01

CTQ-total

0.08

1.38

.286

.01

CTQ

DERS

0.73

1.01

.313

>

.01

Relationship intimacy

Step 1

3.76

0.04

Age

0.16

2.15

.033

Relationship length

0.10

1.30

.195

Step 2

2.02

0.02

Age

0.15

2.01

.046

.01

Relationship length

0.10

1.37

.172

.01

DERS-total

0.83

1.07

.285

>

.01

CTQ-total

0.15

1.94

.054

.02

Step 3

0.58

>

0.01

Age

0.14

1.85

.066

.02

Relationship length

0.11

1.41

.160

.01

DERS-total

0.64

0.87

.387

>

.01

CTQ-total

0.14

1.78

.078

.02

CTQ

DERS

0.57

0.76

.449

>

.01

Relationship affection

Step 1

10.34

.10

Age

0.25

3.53

.001

.01

Relationship length

0.16

2.28

.024

>

.01

Step 2

1.93

.02

Age

0.24

3.35

.001

.01

Relationship length

0.17

2.30

.023

<

.01

DERS-total

0.12

1.59

.115

.02

CTQ-total

0.12

1.59

.113

.08

Step 3

1.95

.01

Age

0.23

3.13

.002

.01

Relationship length

0.17

2.35

.020

>

.01

DERS-total

0.78

1.09

.279

.01

CTQ-total

0.11

1.40

.163

.07

CTQ

DERS

0.67

0.93

.356

.01

Note. Intimacy and Affection are subscales of the Network of Relationships Inventory: Social Provisions Version–Revised. CTQ

¼ Childhood

Trauma Questionnaire; DERS

¼ Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; s-r ¼semi-partial coefficient; SSS ¼ Sexual Satisfaction Scale.

p < .05.

p < .001.

EMOTION DYSREGULATION AND SEXUALITY

439

Relationship intimacy (NRI–SPV–R).

Step 1 of the

model was statistically significant, F(2, 178)

¼ 3.67,

p < .05, indicating that age and relationship length

explained 4% of the variance in Intimacy. Step 2 pre-

dicted a nonsignificant 3% of the variance in NRI–

SPV–R Intimacy. Inconsistent with prediction, Step 3

did not provide a significant interactive effect for

NRI–SPV–R Intimacy.

Relationship affection (NRI–SPV–R).

Step 1 of the

model was statistically significant, F(2, 178)

¼ 10.34,

p < .001. Inconsistent with prediction, Steps 2 and 3 were

not significant, DF(2, 176)

¼ 1.93 and 1.95, respectively.

Discussion

Results were partially consistent with the hypotheses.

First, severity of childhood maltreatment was negatively

associated with sexual and relationship satisfaction,

further corroborating the well-documented array of

interpersonal difficulties experienced by adult women

exposed to neglectful and abusive childhood environ-

ments (Davis & Petretic-Jackson, 2000; DiLillo, 2001;

Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, & Livingston, 2005). Moreover,

severity of childhood maltreatment was positively corre-

lated with emotion regulation difficulties—a finding in

line with the theory that tumultuous social environments

may affect the ability of children to learn coping

mechanisms to regulate internal emotional states (Kim

et al., 2009; Linehan, 1993).

In agreement with a previous study (Rellini et al.,

2010), greater levels of difficulties in emotion regulation

were incrementally, negatively correlated with sexual

satisfaction. Specifically, difficulties in emotion regu-

lation independently contributed to the prediction of

variance in sexual satisfaction in the context of age,

relationship length, and childhood maltreatment sever-

ity. This result highlights the unique explanatory role

of emotion dysregulation on sexual satisfaction above

and beyond the effects of childhood maltreatment. In

fact, the effect size of the association between sexual

satisfaction and difficulties in emotion regulation (s-r

2

¼

.06) was stronger than that observed between sexual

satisfaction and childhood maltreatment (s-r

2

<

.01).

These findings, which replicate and extend past work

on the relations of emotion regulation with childhood

maltreatment (Kim & Cicchetti, 2010) and with sexual

satisfaction (Rellini et al., 2010), suggest that difficulties

in emotion regulation offer unique explanatory value

for better understanding sexual satisfaction among

women with varying degrees of childhood maltreat-

ment. Based on these findings, prospective tests of the

role of emotional regulation in regard to sexual satisfac-

tion represent an important next step in this line of

inquiry.

Inconsistent with expectations, difficulties in emotion

regulation did not significantly predict relationship inti-

macy or affection satisfaction. Thus, emotion regulation

may offer explanatory value for some, but not all,

aspects of relationship processes among young adult

women with a history of maltreatment. Childhood

maltreatment severity also demonstrated positive corre-

lations, but relatively minimal, concurrent predictive

power in regard to affection and intimacy among this

sample. This finding, in particular, was unexpected given

that previous studies have documented that adults

exposed to childhood sexual abuse tend to develop

difficulties in developing and maintaining functional

intimate relationships (Beitchman et al., 1992; Browne

& Finkelhor, 1996; Carson, Gertz, Donaldson, &

Wonderlich, 1990; Testa et al., 2005). The different find-

ings may be the product, in part, of the measurement of

affection and intimacy satisfaction utilized in this study.

Namely, the NRI–SPV–R asks participants to indicate

how much they were likely to talk about secrets and per-

sonal matters with partners (intimacy) and how much

they felt loved and cared for by their partners (affec-

tion). These operational definitions of intimacy and

affection may not be fully comprehensive and may

thereby only capture aspects of intimacy that are not

salient to trauma survivors (i.e., disclosing secrets),

and overlook other important aspects. Alternatively, it

is possible that the lack of a significant association

between childhood maltreatment and intimacy or affec-

tion satisfaction may be partially due to the utilization

of a measure of childhood physical, emotional, and sex-

ual abuse, as compared to a focus on sexual abuse sever-

ity alone, as it was assessed in the previous study (Testa

et al., 2005). Finally, intimacy may simply not be an

aspect of relationship functioning that is associated with

childhood maltreatment. For example, an individual

exposed to childhood maltreatment may have learned

to share secrets and personal information with others

but may not know how to assert his or her needs with

a partner. As a result, there may be utility in exploring

related, but distinct, constructs (e.g., trust, sense of

worth) in future work with trauma-exposed persons.

Also, contrary to our prediction, there was no empiri-

cal evidence of an interactive effect between difficulties

in emotion regulation and childhood maltreatment

severity for any of the criterion variables. Thus, there

was no evidence of systematic interplay between these

two constructs in terms of the studied criterion variables

among this trauma-exposed sample of women. As sexual

and relationship satisfaction are likely influenced by

numerous factors (Christopher & Sprecher, 2000;

Wishman & Uebelacker, 2007), a more concerted effort

may usefully be applied to exploring other types of

interactive processes in future studies.

Although not the primary aim of this study, inspec-

tion

of

the

zero-order

correlations

indicated

an

interesting set of findings. Specifically, low emotional

RELLINI, VUJANOVIC, GILBERT, AND ZVOLENSKY

440

clarity was negatively associated with sexual satisfac-

tion, as well as affection and intimacy satisfaction, sug-

gesting that clarity of emotional responses is an

important aspect of sexual and relational satisfaction.

One way to interpret these findings is that understanding

one’s emotions is an essential aspect of communication

and, to the extent that clarity of communication plays

an important role in both sexual and relationship satis-

faction (Kelly, Strassberg, & Turner, 2006; MacNeil &

Byers, 2009; Wheeless, Wheeless, & Baus, 1984), then

clarity of emotions becomes important for both sexual

and relationship satisfaction. Somewhat surprisingly,

higher impulsivity was positively correlated with inti-

macy, indicating that women who were more impulsive

tended to share more personal and intimate information

with their partners. Of course, it is not clear whether all

forms and types of intimacy are equally healthy in a

relationship and, specifically, if sharing information

because of impulsivity is any healthier for a relationship

than maintaining some boundaries in the type of sharing

that occurs between partners.

Severity of childhood maltreatment evidenced a

significant correlation with difficulties in emotion regu-

lation (r

¼ .28). This finding replicates and extends past

work, documenting associations between childhood vic-

timization and emotional dysregulation among adults

(e.g., Briere & Rickards, 2007). Furthermore, this find-

ing provides replication of past work, demonstrating

significant associations between posttraumatic stress,

generally, and difficulties regulating emotion (e.g.,

Lanius et al., 2003; Litz, Orsillo, Kaloupek, & Weathers,

2000). For example, Tull, Barrett, McMillan, and

Roemer (2007) found that posttraumatic stress symp-

tom severity was significantly associated with greater

difficulties in emotion regulation, specifically lack of

acceptance of emotional experiences, lack of clarity of

emotional responses, and limited emotion regulation

strategies. This is the first study to date, however, to

document associations between childhood maltreatment

severity and difficulties in emotion regulation.

This study has a number of interpretative caveats.

First, the sample was recruited through Internet

methods and may not be fully generalizable to other

populations recruited via alternative methods. Second,

causal interpretations of these results are not possible

due to the cross-sectional design and use of measures

that aggregate experiences. Third, method variance

may have contributed to the observed effects, as

self-report instruments were exclusively employed to

measure the constructs of interest. Fourth, as the

study aims were focused on ascertaining basic psycho-

logical processes associated with relationship quality

among a female population, we did not study a spe-

cific clinical population. Future research could extend

these findings in a meaningful way by studying parti-

cipants seeking treatment for relationship or sexual

problems.

In summary, the results of this study, in conjunction

with other recent evidence (Rellini et al., 2010), are

consistent with the view that individual differences in

emotion regulation may be relevant to better under-

standing sexual and relationship satisfaction. Research

is now needed to explore the stability of such findings

over time in order to determine the time course and

sequencing of change between the studied variables.

References

Beitchman, J. H., Zucker, K. J., Hood, J. E., DaCosta, G. A., Akman,

P. A., & Cassavia, E. (1992). A review of the long-term effects of

child sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 16, 101–118.

Bernstein, D. P., Fink, L., Handelsman, L., & Foote, J. (1994). Initial

reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child

abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151,

1132–1136.

Briere, J., & Rickards, S. (2007). Self-awareness, affect regulation, and

relatedness: Differential sequels of childhood versus adult victimi-

zation experiences. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195,

497–503.

Browne, A., & Finkelhor, D. (1996). Impact of child sexual abuse: A

review of the research. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 66–77.

Carson, D. K., Gertz, L. M., Donaldson, M. A., & Wonderlich, S. A.

(1990). Family-of-origin characteristics and current family

relationships of female adult incest victims. Journal of Family

Violence, 5, 153–171.

Christopher, F. S., & Sprecher, S. (2000). Sexuality in marriage, dat-

ing, and other relationships: A decade review. Journal of Marriage

& the Family, 62, 999–1017.

Cole, P. M., Michel, M. K., & Teti, L. O. D. (1994). The development

of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective.

Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development,

59(23), 73–100.

Davis, J. L., & Petretic-Jackson, P. A. (2000). The impact of child sex-

ual abuse on adult interpersonal functioning: A review and syn-

thesis of the empirical literature. Aggression and Violent

Behavior, 5, 291–328.

Davis, J. L., Petretic-Jackson, P. A., & Ting, L. (2001). Intimacy

dysfunction and trauma symptomatology: Long-term correlates

of different types of child abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress,

14, 63–79.

DeSilva, P. (2001). Impact of trauma on sexual functioning and sexual

relationships. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 16, 269–278.

DiLillo, D. (2001). Interpersonal functioning among women reporting

a history of childhood sexual abuse: Empirical findings and meth-

odological issues. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 553–576.

Fromuth, M. E. (1986). The relationships of childhood sexual abuse

with later psychological adjustment in a sample of college women.

Child Abuse and Neglect, 10, 5–15.

Fruzzetti, A. E., & Iverson, K. M. (2004). Couples dialectical behavior

therapy: An approach to both individual and relational distress.

Couples Research and Therapy, 10, 8–13.

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (2009). The Network of Relationships

Inventory: Behavioral and systems version. International Journal

of Behavioral Development, 33, 470–478.

Gratz, K., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of

emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor

structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion

Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral

Assessment, 26, 41–54.

Kelly, M. P., Strassberg, D. S., & Turner, C. M. (2006). Behavioral

assessment of couples’ communication in female orgasmic

disorder. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 32, 81–95.

EMOTION DYSREGULATION AND SEXUALITY

441

Kim, J., & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Longitudinal pathways linking child

maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psycho-

pathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51,

706–716.

Kim, H. K., Pears, K. C., Capaldi, D. M., & Owen, L. D. (2009).

Emotion dysregulation in the intergenerational transmission of

romantic relationship conflict. Family Psychology, 23, 585–595.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual

behavior in the human male. Oxford, England: Saunders.

Lanius, R. A., Williamson, P. C., Hopper, J., Densmore, M.,

Boksman, K., Gupta, M., et al. (2003). Recall of emotional states

in posttraumatic stress disorder: An fMRI investigation. Biologi-

cal Psychiatry, 53, 204–210.

Leonard, L. M., & Follette, V. M. (2002). Sexual functioning in

women reporting a history of child sexual abuse: Review of the

empirical literature and clinical implications. Annual Review of

Sex Research, 13, 346–388.

Lewis, R. W., Fugl-Meyer, K. S., Corona, G., Hayes, R. D., Laumann,

E. O., Moreira, E. D., et al. (2010). Definition=epidemiology=risk

factors for sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7,

1598–1607.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline

personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford.

Litz, B. T., Orsillo, S. M., Kaloupek, D., & Weathers, F. (2000).

Emotional processing in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal

of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 26–39.

Loeb, T. B., Williams, J. K., Carmona, J. V., Rivkin, I., Wyatt, G. E.,

Chin, D., et al. (2002). Child sexual abuse: Associations with the

sexual functioning of adolescents and adults. Annual Review of

Sex Research, 13, 307–345.

MacNeil, S., & Byers, E. S. (2009). Role of sexual self-disclosure in the

sexual satisfaction of long-term heterosexual couples. Journal of

Sex Research, 46, 3–14.

Mennin, D. S. (2004). Emotion regulation therapy for generalized

anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 11,

17–29.

Meston, C. M., Heiman, J. R., Trapnell, P. D., & Carlin, A. S. (1999).

Ethnicity, desirable responding, and self-reports of abuse: A com-

parison of European- and Asian-ancestry undergraduates. Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 139–144.

Meston, C. M., & Trapnell, P. D. (2005). Development and validation

of a five factor sexual satisfaction and distress scale: The Sexual

Satisfaction Scale for Women (SSS–W). Journal of Sexual

Medicine, 2, 66–81.

Parish, W. L., Luo, Y., Stolzenberg, R., Laumann, E. O., Farrer, G., &

Pan, S. (2007). Sexual practices and sexual satisfaction: A

population based study of Chinese urban adults. Archives of

Sexual Behavior, 36, 5–20.

Rellini, A. H. (2008). Review of the empirical evidence for a theoretical

model to understand the sexual problems of women with a history

of CSA. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5, 31–46.

Rellini, A. H., & Meston, C. M. (2007). Sexual function and satisfac-

tion in adults based on the definition of child sexual abuse.

Journal of Sexual Medicine, 4, 1312–1321.

Rellini, A. H., Vujanovic, A. A., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2010). Emotional

dysregulation: Concurrent relation to sexual problems among

trauma-exposed adult cigarette smokers. Journal of Sex & Marital

Therapy, 36, 137–153.

Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Goldman, S. L., Turvey, C., & Palfai, T. P.

(1995). Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring

emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In

J. W. Pennebaker (Ed.), Emotion, disclosure, and health (pp. 125–

154). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Scher, C. D., Stein, M. B., Asmundson, G. J. G., McCreary, D. R., &

Forder, D. R. (2001). The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in a

community sample: Psychometric properties and normative data.

Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14, 843–857.

Scholerdt, K. A., & Heiman, J. R. (2003). Perceptions of sexuality as

related to sexual functioning and sexual risk in women with differ-

ent types of childhood abuse histories. Journal of Traumatic

Stress, 16, 275–284.

Testa, M., VanZile-Tamsen, C., & Livingston, J. A. (2005). Childhood

sexual abuse, relationship satisfaction, and sexual risk taking in a

community sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology, 73, 1116–1124.

Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of

definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child

Development, 59(2=3), 25–52.

Tull, M. T., Barrett, H. M., McMillan, E. S., & Roemer, L. (2007). A

preliminary investigation of the relationship between emotion

regulation

difficulties

and

posttraumatic

stress

symptoms.

Behavior Therapy, 38, 303–313.

Walker, E. A., Unutzer, J., Rutter, C., Gelfand, A., Saunders, K.,

VonKorff, M., et al. (1999). Costs of health care use by women

HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect.

Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 609–613.

Wheeless, L. R., Wheeless, V. E., & Baus, R. (1984). Sexual communi-

cation, communication satisfaction, and solidarity in the develop-

mental stages of intimate relationships. Western Journal of Speech

Communication, 48, 217–230.

Wishman, M. A., & Uebelacker, L. A. (2007). Maladaptive schemas

and core beliefs in treatment and research with couples. In L. P.

Riso, P. L. du Toit, D. J. Stein, & J. E. Young (Eds.), Cognitive

schemas and core beliefs in psychological problems: A scientist-

practitioner guide (pp. 199–220). Washington, DC: American

Psychological Association.

RELLINI, VUJANOVIC, GILBERT, AND ZVOLENSKY

442

Copyright of Journal of Sex Research is the property of Routledge and its content may not be copied or emailed

to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However,

users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Extending Research on the Utility of an Adjunctive Emotion Regulation Group Therapy for Deliberate S

Shearer (2009) Internet users Personality, pathology, and relationship satisfaction

Ebsco Garnefski Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and emotional problems in 9 11 year old ch

Ebsco Martin Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression, anxiety, stress, and an

Ebsco Garnefski Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and emotional problems in 9–11 year old ch

Ebsco Martin Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression, anxiety, stress, and an

Ebsco Garnefski Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and emotional problems in 9–11 year old ch

Ebsco Garnefski Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and emotional problems in 9 11 year old ch

Ebsco Garnefski Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and emotional problems in 9 11 year old ch

Ebsco Garnefski Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems

Resilience and Risk Factors Associated with Experiencing Childhood Sexual Abuse

Delay in diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus vaccination is associated with a reduced risk of childhood a

04 Emotional Intelligence and Emotion Regulation S

Avoidant or Ambivalent Attachment Style as a Mediator between Abusive Childhood Experiences and Adul

Ebsco Garnefski Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems pl

Ebsco Garnefski The Relationship between Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies and Emotional Pro

Emotional dissonance, emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction in call centre workers

Osteochondritis dissecans in association with legg calve perthes disease

więcej podobnych podstron