Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tjom20

Download by: [31.2.15.191]

Date: 16 February 2016, At: 18:41

Journal of Maps

ISSN: (Print) 1744-5647 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tjom20

Mythical creatures of Europe

Giedrė Beconytė, Agnė Eismontaitė & Jovita Žemaitienė

To cite this article: Giedrė Beconytė, Agnė Eismontaitė & Jovita Žemaitienė (2014) Mythical

creatures of Europe, Journal of Maps, 10:1, 53-60, DOI: 10.1080/17445647.2013.867544

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2013.867544

Published online: 09 Dec 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 5280

SOCIAL SCIENCE

Mythical creatures of Europe

Giedre˙ Beconyte˙

∗

, Agne˙ Eismontaite˙ and Jovita Z

ˇ emaitiene˙

Centre for Cartography, Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania

(Received 20 October 2012; Resubmitted 1 July 2013; Accepted 15 November 2013)

The map of Mythical Creatures of Europe represents information on 213 mythical creatures of

68 types that are described in folk-lore of European countries. It is compiled from data collected

by MSc students in Cartography at Vilnius University in Lithuania in 2011, totalling

approximately 1200 man hours. Among numerous sources of information on mythical

creatures, this map and database are unique as they contain geographic references and

information on the living environment of so many creatures. Only the most reliable

information has been included in the informative and visually attractive wall map. The

project included planning, analysis of feasibility, data collection, verification, generalisation

and filtering, classification of information on mythical creatures, building the GIS database,

analysis of data, and cartographic visualisation. The map described in this paper was

finalised in 2012 and designed with special focus on attractiveness for the user. The

reference scale of the printed map is 1:7,200,000 and contains an inset of Greece at scale

1:4,000,000. The size of the map image is 62.5

× 83 cm. It is complemented by textual

descriptions of each of 213 creatures. The relational database and exhaustive project

documentation are available for further updates and development.

Keywords: mythical creatures; supernatural creatures; legendary beasts; mythology; map;

cartography; Europe

1.

Introduction

Supernatural creatures have existed within in folklore of all countries since ancient times. Most of

them are believed to reside in particular countries, areas or landscape habitats, thus forming

diverse ‘ecological’ communities that could be called mythobiocenoses. These can potentially

be analyzed geographically. As there are so many kinds of mythical creatures and so various

beliefs concerning their shape, character and habits, most of the reliable information sources

are dedicated to just one or several types of such beings, their definitions, cultural roots and

related folklore. The authors have not found references to publications devoted to a geographic

inventory or distribution analysis of mythical creatures in any European country or a region.

On the other hand, most of primary sources of information about particular creatures (e.g.,

legends, tales, songs, anecdotes) contain geographic references. Thus we see a gap in cultural

geography that could to some extent be filled by providing maps and geographic databases.

They would allow better understanding of the mythical landscape in a territory.

#

2013 Giedre˙ Beconyte˙

∗

Corresponding author. Email:

Journal of Maps, 2014

Vol. 10, No. 1, 53 – 60, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2013.867544

Downloaded by [31.2.15.191] at 18:41 16 February 2016

The idea to create a map of mythical creatures (Main Map;

) was initially inspired by the legend about Huang Di, the ‘Yellow

Emperor’ of China who encountered on top of a mountain near the Eastern Sea the ancient

beast Bai Ze, a wise and holy creature, capable of human speech. The emperor used its knowl-

edge for understanding and management of other supernatural creatures of the known world.

The beast dictated the characteristics of all the ‘11,520 types of demons, monsters, shapeshif-

ters, and peculiar spirits’ and put their names on a map (

). The drawings and

writings have been published in a fascinating book, believed to be written by the emperor

himself, the ‘Bai Ze Guide’. There is no evidence that the book or the map still exist.

We believed that modern information technologies would make such work much easier.

The authors have found thousands of scientific and popular information sources about mythi-

cal creatures. The first analysis showed that only a small part of them are reliable; namely,

detailed studies in history and mythology of relatively small ethnographic areas, such as,

for example, Northern Lithuania, that refers to old, authentic narrative folk-lore. We started

developing a schema of the database for Lithuania and collecting information in spring of

2011. It soon became evident that such work, even completed at 1:250,000, would require

so many man hours, that a long-term project was needed. Instead, we decided to make a

pilot project at much smaller scale and larger territory that would be of interest to a much

wider audience.

The database of mythical creatures of the geographic territory of Europe has been compiled

mainly from cumulative sources and verified against other published sources in Lithuanian,

Czech, English, German, Latvian, Polish, Russian, Spanish and Ukrainian languages. The aim

of the project was to demonstrate the possibility and advantages of a geographic approach in

mythology and folk-lore studies.

The main tasks were:

.

to develop tentative typologies for geographic and some non-geographic characteristics of

mythical creatures;

.

to propose a versatile schema of a geographic database;

.

to collect reliable information of the most known mythical creatures in Europe into the

database;

.

to design an attractive wall map based on the collected data.

The targeted user groups are children of various ages and the general public. We do not claim

to have collected exhaustive, absolutely unbiased and precise information for the continent or rep-

resented it in the best way possible. The database and the map are rather a demonstration of feasi-

bility of the initiative than a finished project. We invite geographers and academic folklorists to

co-operate in developing the database and making the same style maps for smaller European

regions or individual countries.

2.

Target area

Based on various sources we accepted a ‘malleable’ definition of a mythical creature as a super-

natural being that is or was believed to be a material creature residing in a particular territory on

Earth and described in folk-lore sources native to that territory.

The requirements for a mythical creature to be included into the database were as follows:

(1) The creature must be mentioned in many authentic and sufficiently folk-lore plots, for

example, a devil, a fairy, a dragon;

54

G. Beconyte˙ et al.

Downloaded by [31.2.15.191] at 18:41 16 February 2016

(2) It must be believed to reside in particular places on Earth, basically in the territory of resi-

dence of a corresponding ethnic group, and seen by local people;

(3) It must appear in identifiable shape(s) (shapeshifters were included).

The following types were not included in the map as they do not comply with the definition:

.

fictional characters, only sporadically mentioned in some books and (or) legends;

.

ghosts and spirits, such as spook, phantom, ignis fatuus;

.

deities and demons, except semi-divine creatures that were believed to live on Earth and to

be encountered by people. For example, folk devils and imps are included, but not theolo-

gical demons;

.

fantastic beings created for a purpose (for example, a bogeyman invented by parents to

frighten children into compliant behaviour);

.

human characters, folks, figures with historical origins (such as Father Christmas or

legendary Arimaspi people in Scythia).

.

golems and homunculi.

Singular instances were described in the database but included in the map only in the case of

their historical significance (like Minotaur) and/or being widely known outside their home area

(like the Loch Ness monster). The significance of particular creatures was determined by the

authors based on popularity of the creature inside the country or culture and on the scale of

inclusion in various directories.

The database contains 274 records. Each of them describes a unique creature or a class of very

similar creatures, such as Slavic dragon, that is actually the term for several variations of an evil

dragon with three or nine heads and four extremities. Due to uncertainty of some information or

lack of information about the location only 213 creatures have been represented on the map. A

description of each can be found in textual tables by its unique number on the map. The database,

map and project information were initially prepared in Lithuanian and afterwards all texts were

translated into English.

3.

Types and characteristics of the creatures

Typology is necessary before one begins collecting information on countless mythical beings in a

large territory. A system that would allow finding a precise place for a new creature based on its

main characteristics is in principle possible, however, there is such a great variety of character-

istics with so negligible differences, that the task of creating a perfect system is impossible. There-

fore an ‘official’ taxonomy of mythical creatures does not exist. The authors of various lists

simply choose one or more classification criteria such as general shape (dragons, giants,

mermaids), habitat (water bodies, mountains, caves) or, rather often, the culture that the creature

belongs to. Most existing classifications appear superficial, inconsistent (e.g.

) or not sufficient for our purposes. Others were too detailed or insufficiently

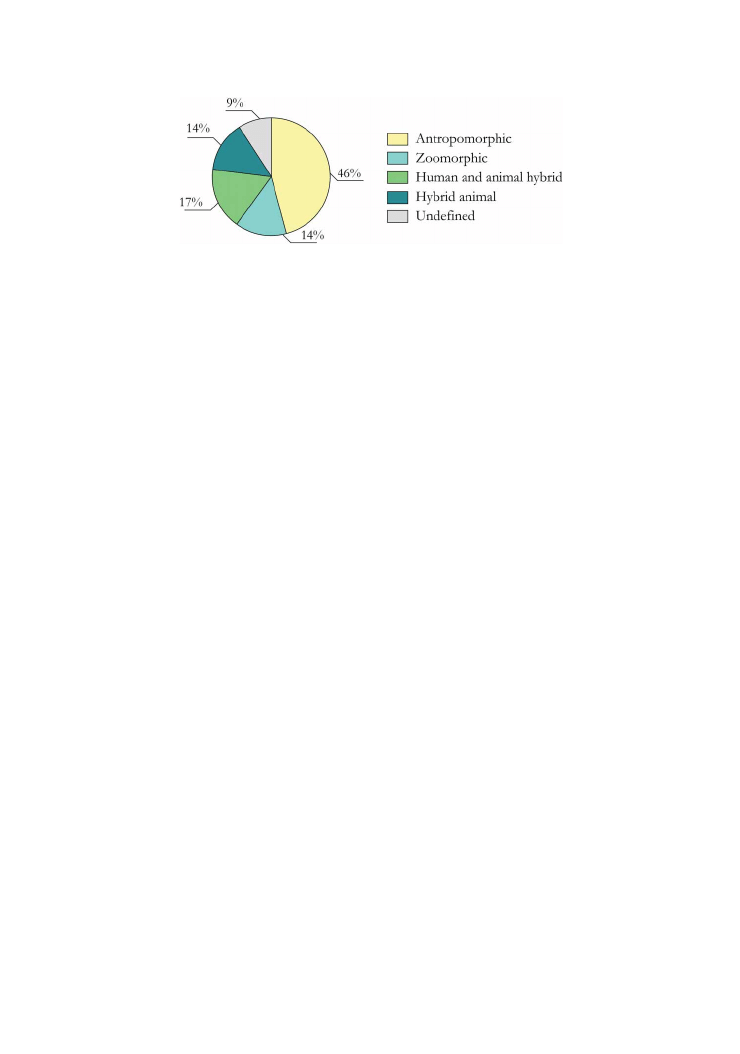

‘visual’. We therefore developed a new three-level classification that meanwhile encompasses 213

concrete types and is based on appearance of creatures (

.

Anthropomorphic (generally human shaped creatures):

W

Giants;

W

Dwarfs;

W

Other (‘normal’ human size);

Journal of Maps

55

Downloaded by [31.2.15.191] at 18:41 16 February 2016

.

Zoomorphic (creatures that resemble real animals):

W

Birds;

W

Wolves/dogs;

W

Other (horses, fishes and several more subtypes; so far only a few of them have more

than one instance in the database);

.

Human and animal hybrid (creatures that combine human and animal features; no second-

level subtypes):

.

Hybrid animal (creatures that combine features of two or more real animals; no second-

level subtypes);

.

Dragons (creatures that are very similar to hybrid animals, mainly reptiles and birds, but

deserve a separate class due to their importance in folk-lore of practically all cultures);

.

Undefined (creatures which appearance is variable or ambivalent, like Aitvaras, seen in

shape of a rooster, as a fireball or invisible; werewolves belong to the corresponding

zoomorphic type).

There was some discussion concerning inclusion of mythical creatures (mainly single speci-

men) that are reported as extinct (dead, killed, transformed into inanimate objects etc.). After all,

most mythical species are culturally disappearing. Therefore all reliable records on extinct crea-

tures have been represented on the map.

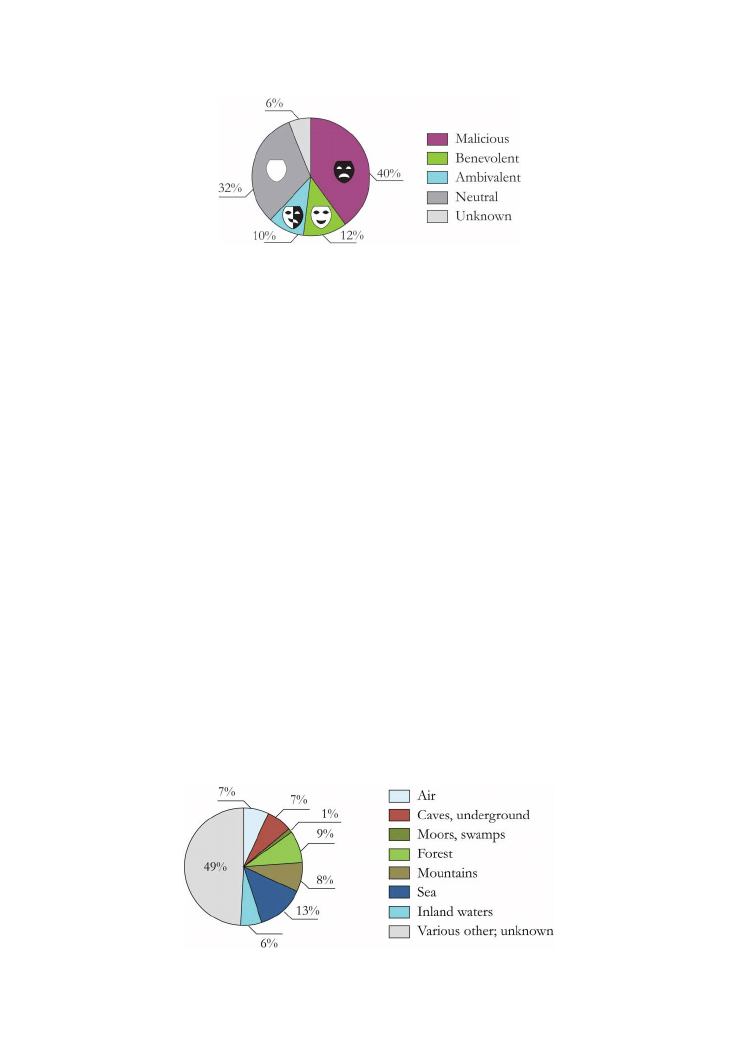

Disposition towards people is an interesting characteristic, however it was not always easy to

determine. In cases where it was possible, it is represented in the map legend by a mask-like

symbol:

.

Malicious or harmful (e.g Slavic dragon);

.

Benevolent or useful (e.g. unicorn);

.

Ambivalent (e.g. witch);

.

Neutral (e.g. banshee).

In quite a few cases information on disposition, especially for more exotic beings, could not

be found. Several creatures are described differently depending of culture or country, for example

Slavic vila. Corresponding records in the table do not have a sign (

).

Environmental information is something that makes the database unique and much more geo-

graphic. About a half of creatures are described in folk-lore as residing in specific environmental

conditions (

). On the map, typical environment is represented by surrounding drawings of

trees, caves, three types of mountains and lakes.

Figure 1.

Distribution of mythical creatures by type.

56

G. Beconyte˙ et al.

Downloaded by [31.2.15.191] at 18:41 16 February 2016

One more important characteristic is the frequency of occurrence:

.

Singular (e.g. Charybdis);

.

Rare (exists in particular small region, e.g. snoise in Iceland);

.

Frequent (exists in several countries within the limits of one culture, e.g. only in Slavonic

culture or in Celtic culture, e.g. vampire);

.

Common (widespread in the areas of various European cultures, e.g. hag).

This information is stored in the database, but is not represented on the map. Frequency of

general types is immediately perceived from the map whereas frequency of instances in most

cases is very difficult to estimate.

4.

Data and the database

The project is likely the first attempt to collect and visualise spatial information (typologies, living

environment, diversity and distribution) about mythical beings. Diverse cumulative sources such

as encyclopaedias, monographs devoted to mythology of particular cultures (

;

) or types of creatures (

;

) and publicly available

open-source materials from the Internet were the sources of information about mythical creatures

of Europe (due to large number of references, non-English publications and Internet sites are not

included). The authors analyzed over 100 Internet mythology sites in Czech, English, German,

Lithuanian, Polish, Russian and Spanish languages. Encyclopaedia Mythica. (

) is just one example.

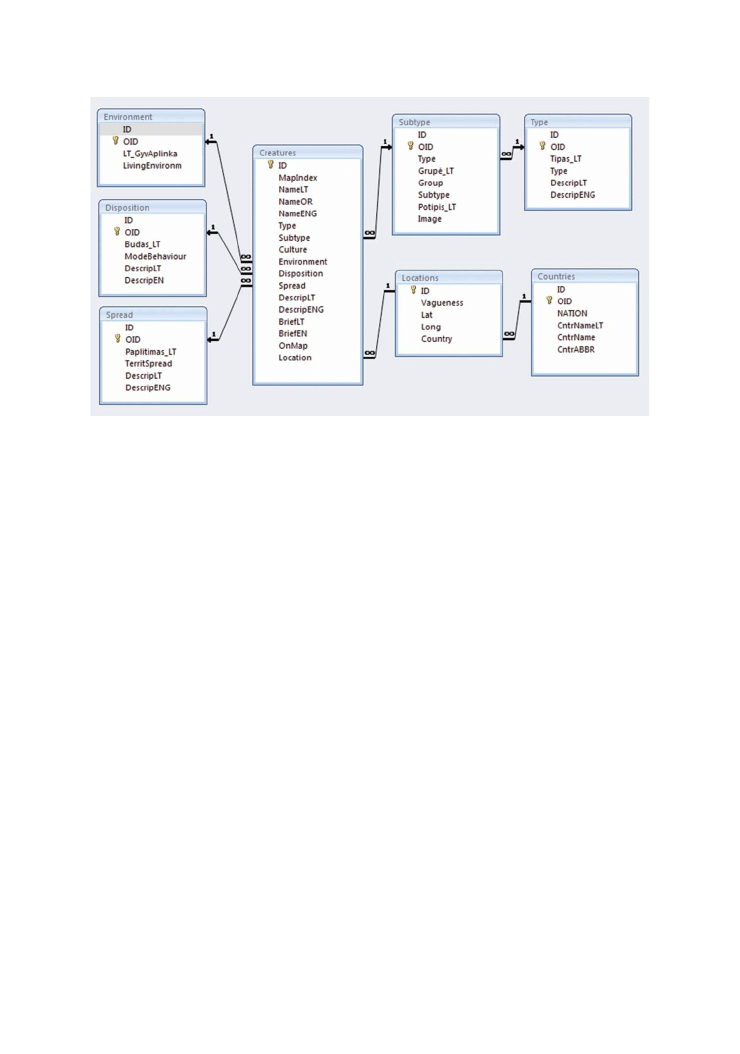

Data on mythical creatures and their characteristics have been collected using an evolutionary

approach. It means that the database was compiled as serial versions, starting from the draft

Figure 2.

Distribution of mythical creatures by disposition towards people.

Figure 3.

Distribution of mythical creatures by living environment.

Journal of Maps

57

Downloaded by [31.2.15.191] at 18:41 16 February 2016

version which contained only names and location information for the creatures. Each newer

version was reviewed, corrected and complemented, often with the help of different specialists,

so that the full extent and structure of information (

) unfolded step by step. Such a

method works well when working with uncertain and vague thematic information.

The collected data were verified against several comprehensive printed sources (

;

;

;

). The reliability of collected information

was routinely checked by a person other than the one who collected the relevant data and

using as many different sources as possible.

Location data were especially important for the project. The main problem is that whilst some

creatures are spread widely across large areas, others reside in precisely identifiable locations.

Some geographic references are uncertain (e.g. Iceland); some vary in different sources, thus

making precision of geographic data variable from a large region (e.g. Western Russia) to

almost co-ordinate level (a particular small lake or rock). Information on geographic vagueness

was represented by a corresponding attribute in the database, but not shown on the current

version of the map. Due to high-concentration locations were generalised, especially in Central

and Northern Europe.

The final version of the database contains 274 records of mythical creatures mainly within the

geographic boundaries of Europe, some spreading in neighbouring areas. Of these, 227 creatures

are represented on the map.

5.

Cartographic design

The chosen object-oriented design approach helps to avoid errors in visualisation as it ensures that

the selected attributes are all represented on the map, and it makes the design and reviewing pro-

cesses more efficient.

The drawings for 66 third-level subtypes and symbols of living environment were created

specifically for this project based on various available images, textual descriptions of creatures

Figure 4.

Database schema.

58

G. Beconyte˙ et al.

Downloaded by [31.2.15.191] at 18:41 16 February 2016

and the imagination of authors. Symbols of mountains and hills of different height have also been

drawn manually as well as the forest areas.

Reference data have been generalised to match the scale of the map if printed on ISO A0

format (1:7,200,000). Due to the large quantity of thematic information, only country names,

boundaries, hydrography and forests are included on the map. Ethnic regions are represented

by different background colours.

6.

Conclusion

The map of Mythical Creatures of Europe serves two purposes.

(1) It is likely the first attempt of such scale to collect and visualise spatial information (typol-

ogies, habitats, diversity and distribution) about known mythical beings; it is a geo-

graphic inventory that may be of use for anyone interested in mythology and ethnology.

(2) The map as a piece of art, made attractive by combining old and modern cartographic

design elements, can raise people’s interest in folk-lore and leads to better understanding

of other cultures in Europe.

Diversity of information sources in seven European languages used to collect the information

and professionally collected geographic references makes the database reliable at the given scale.

It is unique in terms of structure and content. Very precise data on mythical creatures of a small

territory can be collected using the same database structure.

Software

The main data have been collected and maintained in a Microsoft Access database. ESRI ArcGIS 10.0 has

been used for building the GIS database of locations. Adobe Illustrator graphic design software has been

used for design of the cartographic symbols and for overall cartographic design. Microsoft Office and

Google Documents have been used for project documentation and information sharing, and Microsoft

Project for project planning and management.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to members of the project team for collection and processing of data, project documentation

and useful suggestions concerning the map’s design, especially to exchange students Rico Beckert and

Michal Stransky and artists Anele˙ C

ˇ iru¯naite˙ and Jolanta Dzemydiene˙ who have designed several map

symbols. We thank the Centre for Cartography at Vilnius University for sharing its generalised GIS data

on hydrography, state boundaries and ethnic regions of Europe for this map.

References

Baring-Gould, S. (2010). Curious myths of the middle ages. Charleston: Nabu Press.

Beconyte˙, G., & Viliuviene˙, R. (2009). The concept and importance of style in cartography. Geodezija ir

kartografija (Geodesy and Cartography), 35(3), 82 – 91.

Cotterell, A. (1996). The encyclopedia of mythology: Classical celtic norse. New York: Smithmark Pub.

Cotterell, A., & Rizzo, T. (2008). Ultimate encyclopedia of mythology. Emmaus: JG Press.

Crossley-Holland, K. (1981). The norse myths. New York: Pantheon Books.

Day, M. (2007). 100 characters from classical mythology: Discover the fascinating stories of the greek and

roman deities. Barrons Educational Series.

Daly, K. N. (2009). Greek and roman mythology A to Z. New York: Chelsea House Publications.

Enzler, S. M. (2012). Water mythology. Lenntech. Retrieved from

http://www.lenntech.com/water-mythology.

Journal of Maps

59

Downloaded by [31.2.15.191] at 18:41 16 February 2016

Graves, R. (1997). The larousse encyclopedia of mythology. New York: Smithmark Pub.

Harper, D. (1985). A Chinese demonography of the third century B. C. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies,

45(2), 459 – 498.

Kononenko, N. (2007). Slavic folklore: A handbook. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

Lecouteux, C. (2000). Eine Welt im Abseits: Zur niederen Mythologie und Glaubenswelt des Mittelalters.

Dettelbach: Ro¨ll Verlag.

Neil, Ph. (2011). Eyewitness mythology. New York: DK Publishing.

Rolleston, T. W. (1990). Celtic myths and legends. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications.

Rose, C. (2001). Giants, monsters, and dragons: An encyclopedia of folklore, legend, and myth. New York:

W. W. Norton & Co.

60

G. Beconyte˙ et al.

Downloaded by [31.2.15.191] at 18:41 16 February 2016

Document Outline

- Abstract

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Target area

- 3. Types and characteristics of the creatures

- 4. Data and the database

- 5. Cartographic design

- 6. Conclusion

- Software

- Acknowledgements

- References

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Exalted Creatures of the Wyld Bonus Material

2014 05 04 THE ESSENTIALS OF A HEALTHY FAMILY part 3

Dannenberg et al 2015 European Journal of Organic Chemistry

ekonomia integracji europejskiej voir le 28 f vrier 2014 pour les etudiants, ekonomika integracji e

Conan Creatures of the Hyborian Age Part II

Conan Creatures of the Hyborian Age Part I

Hua et al 2009 European Journal of Organic Chemistry

2014 05 11 THE ESSENTIALS OF A HEALTHY FAMILY part 4

Exalted Creatures of the Wyld Bonus Material

2014 05 04 THE ESSENTIALS OF A HEALTHY FAMILY part 3

GURPS (4th ed ) Creatures of the Night 5

Castel Granados, The Mythical Components of the Iberian Witch

Roger Zelazny Creatures of Light and Darkness

Creature Of The Night by americnxidiot

Pike, Christopher Last Vampire 6 Creatures of Forever

India Harper Creatures Of Sin 5 Sins Of Profession

Siebner et al 2001 European Journal of Neuroscience

więcej podobnych podstron