Vol. 39, No. 4, July–August 2009, pp. 346–352

issn

0092-2102

eissn 1526-551X 09 3904 0346

inf

orms

®

doi

10.1287/inte.1090.0432

© 2009 INFORMS

OR Process Skills Transform an Out-of-Control

Call Center into a Strategic Asset

Vijay Mehrotra, Thomas A. Grossman

Department of Finance and Quantitative Analytics, School of Business and Management,

University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California 94117

{drvijay@sbcglobal.net, tagrossman@usfca.edu}

A large consumer-software company was struggling to manage a seemingly unmanageable, high-cost technical-

support call center. The company used “OR process skills” to transform the call center into a strategic asset. By

focusing on executive priorities, personally observing business processes, engaging with frontline workers, and

directly examining the sources of important data, we discovered the central problem amidst a contentious, dis-

organized situation. We used a pilot program to test simple analytical tools, such as Pareto charts and sampling,

to bring actionable information to the right parts of the organization. Following the processes we developed, the

company analyzed customer feedback to improve the product and customer self-support mechanisms, thereby

reducing both current and future call volumes. By empowering client staff and leading process change across

functional boundaries, the company reduced its call-center costs and achieved higher product quality. In addi-

tion, we demonstrate that OR process skills can be an essential element in sustaining long-term consultant-client

relationships.

Key words: OR/MS implementation; data analysis; philosophy of modeling; quality management applications.

History: Published online in Articles in Advance April 22, 2009.

T

his paper describes an engagement from a long

consultant-client relationship. This project utilized

only a few basic analytic techniques, such as statistical

sampling and Pareto charts, adapted to the services

context. Despite its modest mathematical content, this

project is noteworthy because it highlights OR process

skills that are often essential in satisfying client needs

and uncovering opportunities to apply traditional OR.

We describe in context the OR process skills that we

applied and place them into a larger framework of

OR practice.

The client organization is a large consumer-software

company with three product lines. The company had

achieved rapid growth by adding new features to

its products and marketing aggressively; it released

new product versions annually. However, technical-

support call-center expenses were excessive. Senior

management lacked confidence in the call-center man-

agers and felt that the call center was not being man-

aged well.

We used OR process skills to change how the

call center did business and to reestablish senior

management confidence in its operations. The main

benefits to the client were (1) conversion of the call

center into a strategic asset that enabled improved

product quality and customer service, (2) elimina-

tion of a source of aggravation and distraction, and

(3) reduction of call volumes. The benefits to us

were credibility and goodwill, which led directly

to extensive follow-on work performing traditional

OR, including the project described in Saltzman and

Mehrotra (2001).

OR Process Skills

OR process skills address the real-world factors that

are “assumed away” in mathematical models. These

skills, which are essential for enabling organizations

to effectively use analytic models, are part of every

consultant-client engagement. This engagement relied

heavily on seven OR process skills (Table 1).

None of these skills is new, and research literature

exists on many of them. The contribution of this paper

is to describe their role in the context of an engage-

ment that cemented an important long-term client

relationship.

346

Mehrotra and Grossman:

OR Process Skills Transform an Out-of-Control Call Center into a Strategic Asset

Interfaces 39(4), pp. 346–352, © 2009 INFORMS

347

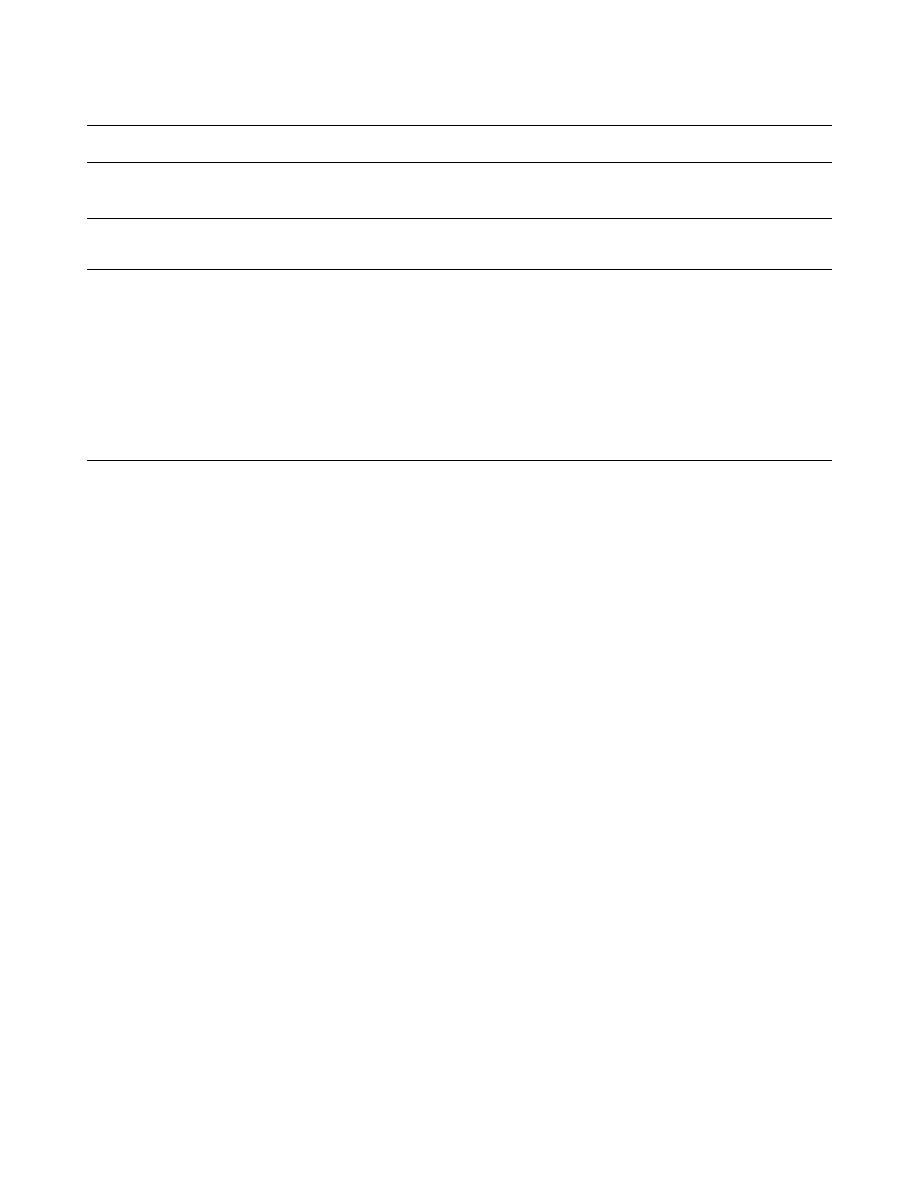

OR process skills used in this engagement

1. Understand and address executive priorities.

2. Personally observe existing business processes.

3. Engage with frontline workers and earn their trust.

4. Examine the source of the data and do not trust data that are given.

5. Use a pilot program before attempting a large-scale rollout.

6. Take the lead in changing business processes, especially across

functions.

7. Empower people in the client organization.

Table 1: This table shows the OR process skills we used in this

engagement.

Literature Survey: Call Centers and

OR Technology

Call centers have been fertile ground for OR. Reseach

includes

call-forecasting

models

(Andrews

and

Cunningham 1995, Avramidis et al. 2004), staffing

models based on queueing theory (Andrews and

Parsons 1993; Koole and Mandelbaum 2002; Green

et al. 2003, 2007), agent-scheduling algorithms

(Andrews and Parsons 1989; Aykin 1996, 2000;

Caprera et al. 2003; Atlason et al. 2004), and sim-

ulation models (Brigandi et al. 1994, Saltzman and

Mehrotra 2001, Mehrotra and Fama 2003). Several

surveys, including Aksin et al. (2007), Gans et al.

(2003), and Grossman et al. (2001), provide additional

references.

The Starting Point

Our client at the software company was the vice pres-

ident of operations (VPO). We had just concluded our

first engagement by delivering a call-center forecast-

ing tool, and we felt strongly that the company had a

need for significant additional work applying the tra-

ditional OR tools of queueing theory, simulation, and

optimization.

However, the company and the VPO had other pri-

orities. The technical-support call centers were in a

crisis state. Customer waiting times were excessive,

with a mean of over five minutes. Call abandonment

was high, at times in excess of 20 percent. Call-center

expenses were 16 percent of revenue, almost triple the

6 percent that competitors were spending.

The VPO, who had executive responsibility for the

call-center operations, felt heavy pressure to resolve

the crisis. Upon learning that this was his top priority,

we proposed to help sort out the problems at the call

center (we used OR process skill 1).

Gathering Information and

Defining the Problem

The problem was ill-defined. We began by gathering

information about the call-center operations from sev-

eral sources, starting with the VPO. Customers con-

tacted technical-service representatives (TSRs) in one

of two locations by calling a toll-free number. Each of

the 300 TSRs cost the company over $50,000 per year,

a total of more than $15 million to the company. The

call center received 45,000 calls per week, with higher

volumes near product release dates, and in Decem-

ber, January, and February because of customer usage

patterns immediately before and after the end of each

calendar year. Call volumes were perceived to be ris-

ing, in part because of a growing customer base.

We talked with call-center line managers. They

believed that they understood their operations well

and provided 50-page reports full of charts, graphs,

and tables that they prepared weekly as evidence.

They claimed that high technical-support costs were

because of error-prone, complex products used by

unsophisticated customers. They argued for increased

funding to hire new TSRs to respond to the increas-

ing call volumes, and felt that the engineering team

should be doing more to fix bugs and improve the

software’s usability.

The call center reported to the VPO but was funded

by a business unit (BU) that was responsible for sales,

marketing, engineering, and product development.

We talked with several BU managers. They were frus-

trated by the call-center performance and lacked con-

fidence in its management. They were also unwilling

to throw more money at the call center when technical

support costs were already much higher than those of

competitors.

We paid frequent visits to the call centers to per-

sonally observe existing business processes, engage

with frontline workers, and examine the source of the

data (we used OR process skills 2–4). In particular, we

spent substantial time sitting with TSRs while they

were talking to customers. Between calls and dur-

ing breaks, we listened carefully to their insights and

worked hard to earn their trust. During a call, a TSR

Mehrotra and Grossman:

OR Process Skills Transform an Out-of-Control Call Center into a Strategic Asset

348

Interfaces 39(4), pp. 346–352, © 2009 INFORMS

listened to a customer’s description of symptoms,

took notes, experimented on his or her own com-

puter, speculated on the cause, searched collections

of Post-it notes and e-mail printouts, consulted online

resources, asked the customer to take certain actions,

and eventually proffered a solution. The variety in

call content was so high that TSRs saw few repeat

problems. (This seemed surprising; however, we veri-

fied that it was true.) We found that supervisors used

each TSR’s average handling time (AHT) in evaluat-

ing performance; therefore, TSRs were under pressure

to keep calls as short as possible.

We observed how they captured raw data on cus-

tomer issues by using a list of over 100 “wrap-up

codes.” At the end of each call, the TSR was sup-

posed to find the appropriate code number from a

three-page list and enter it into his telephone handset.

Because we were physically present and trusted by

the TSRs, we were able to diagnose three significant

problems associated with using the wrap-up codes.

TSRs selected incorrect codes. TSRs had an incentive

to choose a code quickly to ensure short AHTs. Sev-

eral TSRs told us that it was common to simply select

a code arbitrarily rather than search for the correct

one. Not surprisingly, they frequently selected codes

near the top of the list.

The codes were not actionable. The codes were mostly

symptoms (e.g., “General Protection Fault 000254”),

or fixes provided by the TSRs (e.g., “Reinstall the

WPR.EXE file”). They provided no insight into the

root causes of customer problems.

Customer problems did not match codes. The codes

were defined prior to product release. Thus, many

customer problems were not associated with a code

because they were unanticipated. New problems were

not added to the code list, and several TSRs told us

that they typically coded such problems arbitrarily.

We reached several conclusions from this problem-

definition process. First, the wrap-up code data were

fatally flawed; hence, the lengthy reports that the call-

center management generated were neither accurate

nor meaningful. Second, the call center was unable

to provide information to the groups within the BU

(engineering, marketing, and documentation) that

could drive bug fixes and product changes; therefore,

despite tens of thousands of telephone conversations

each week, the company was unable to “hear” its

customers. Finally, without systematic improvements

in the software product, growth in the customer base

would only exacerbate the call-center crisis in the

months and years to follow.

Rethinking the Role of the Call Center

In the short term, the call center continued to fight

for more financial resources to hire additional TSRs

to increase its service capacity. In the long run, how-

ever, we understood that the company had to reduce

the customers’ need to call technical support. To help

achieve this, it needed to expand beyond helping cus-

tomers with their problems; specifically, it needed to

influence the BU to fix product bugs, improve product

usability, and enhance customer self-support materi-

als, all of which would reduce demand for call center

resources. To make this work, the call center needed

to take three actions.

Obtain the correct data. The TSRs had a great deal of

knowledge about underlying causes that the wrap-up

codes did not capture. This knowledge needed to be

captured and utilized.

Analyze data to create actionable information. Based on

feedback from the BU, we knew that it was essen-

tial to provide detailed information about recurrent

problems, their relative frequency, and the context

in which they occurred. The call center needed to

develop a method for analyzing raw data to identify

specific customer problems.

Establish communication and trust across departments.

The call center could not eliminate any customer

issues by making changes to the software, documen-

tation, or Web support resources without the cooper-

ation of the BU.

Learning from a Pilot Program

To test our ideas about data collection and data anal-

ysis, we ran a pilot program (we used OR process

skill 5) involving 16 particularly diligent TSRs at a

call center close to our office. We provided the TSRs

with a simple paper form on which they would

document the customer’s activity when the problem

occurred, the TSR’s assessment of the cause and the

proffered solution(s), and the problem-handling time.

We coached the TSRs to provide plenty of detail and

visited them often to maintain a strong relationship.

Mehrotra and Grossman:

OR Process Skills Transform an Out-of-Control Call Center into a Strategic Asset

Interfaces 39(4), pp. 346–352, © 2009 INFORMS

349

Within two weeks they had created 4,000 paper

forms. We organized the forms into binders under

approximately 100 themes, such as “printer prob-

lems.” This enabled us to distinguish multiple issues

that had previously been incorporated under a single

code. For example, the code “Unable to Print” became

“cannot print a Summary Report,” “when printing

my font is very small,” or “HP Deskjet prints transac-

tions with different margins than I see on my screen.”

Unlike textbook examples, the Pareto chart of the

issues was flat. Fewer than 10 issues had a frequency

of even 1 percent of total calls; approximately 20–30

issues had a frequency 0.5 to 1 percent; and 50–75

issues had a frequency of 0.25 to 0.5 percent. About

half the calls appeared to be unique issues.

Getting Buy-in from the BU

(and Funding from the VPO)

Armed with these results, we still needed to change

business processes so that call-center insights could

be used to improve the product; we also needed the

help of the BU staff to change the processes (we

used OR process skill 6). The BU staff was outside

the VPO’s direct authority and not friendly with the

call center. With difficulty, we were able to set up

meetings with representatives from marketing, engi-

neering, and documentation. In these meetings, we

discovered that both our Pareto charts and the binders

containing the sorted call-content forms were effective

in motivating the BU to take action to address specific

customer issues.

With this level of buy-in from the BU, the VPO

agreed to fund a full-scale “call-stopping” program

that would improve upon the pilot, implement it

across both call centers, and transfer it to client staff.

Developing and Rolling Out the

Full-Scale Call-Stopping Program

Significant changes were needed to develop and im-

plement the full-scale program based on the pilot. To

enable hundreds of TSRs to collect call-content data,

we replaced the paper forms with an Access database

with a Visual Basic interface. Given the large vol-

ume of data, it would be infeasible to examine all

call records; therefore, we used sampling to choose

records for classification.

Most importantly, to sustain the program over the

long run, we needed to empower client personnel to

take ownership of analysis and reporting (we used

OR process skill 7). Two new “call-content analyst”

(CCA) positions were created to analyze call-content

data, organize findings within a database, and com-

municate them across the organization. Two highly

regarded TSRs were hired into these positions. Ulti-

mately, we transferred responsibility for all analysis,

reporting, and communication with other groups to

the CCAs until they owned the entire data collection,

data analysis, and reporting process.

We worked with the CCAs to develop a Visual

Basic platform to randomly sample call records, as-

sign them to specific customer issues based on the

raw data entered by the TSRs, compute frequency

statistics, and generate specific reports.

Given their credibility as former TSRs and knowl-

edge of the products and the organization, the CCAs

were able to take actions that we could not. For exam-

ple, one challenge was to persuade the TSRs to capture

the requisite detailed data. The CCAs were passion-

ate advocates for high-quality data collection. Once

their analysis began to produce insights about cus-

tomer behavior, the CCAs regularly presented their

results to teams of TSRs to motivate them.

We worked to establish new business processes for

communicating results from the call center to the BU

(we used OR process skill 6). We began by changing

the reports that were provided to the BU, focusing on

information quality rather than quantity. We developed

reports of frequently asked questions (FAQs); they

included actionable information on the most common

customer issues. The Excel-based FAQ lists (e.g., Fig-

ure 1) could be sorted on AHT, frequency, or workload

(AHT weighted by frequency).

We produced three primary reports each week. The

“Flash Report” listed all issues that had emerged for

the first time that week. The “Rolling Four-Week

FAQ” provided insight into the cyclical nature of cus-

tomer issues. The BU staff eagerly read the “Year-to-

Date FAQ” to estimate the costs associated with each

of the top issues.

We assembled a cross-functional team comprising

the CCAs, marketing, engineering, documentation,

Web development, and technical-support training. The

Mehrotra and Grossman:

OR Process Skills Transform an Out-of-Control Call Center into a Strategic Asset

350

Interfaces 39(4), pp. 346–352, © 2009 INFORMS

FAQ report

Product1

Call data period: 7/25–10/27

Average handling time (AHT): 13.1

Calls sampled: 5,363

Workload

Workload

rank

(% call minutes)

Freq rank

Freq (%)

AHT

Question ID

Question

1

1.72

1

1.64

1372

63

Report X won’t print on HP printer Y

2

1.27

6

0.95

1747

44

Screen A, field B data conversion incorrect

3

1.21

3

1.21

1306

105

Conflict with ABC’s Anti-Virus Product

4

1.20

4

1.14

1377

343

Won’t import data from program Z when

more than 255 entries

5

1.17

5

0.99

1545

212

Blue screen of death when execute

command C at screen D, Hex dump A365DE113

6

1.11

2

1.55

935

335

Printer type size on IBM, update WPR.EXE

7

1.06

18

0.65

2138

101

Won’t import file type. ABC from program XYZ

8

0.98

28

0.58

2224

311

Wrong default printer pagination option for Brand Alpha

9

0.94

22

0.64

1922

4

Output TOTAL on screen L wrong if subtract negative values

10

0.94

27

0.60

205

38

Product freezes screen E, update C8DRV.DLL

Figure 1: This example of a frequently asked questions report is sorted by workload (the data are disguised).

“Freq” refers to frequency; “AHT” refers to average handling time.

team met weekly to solve problems on the FAQ lists

by acting in three areas:

Product quality. The team eliminated bugs and

improved the user interface by providing immediate

patches and then making permanent changes to the

next major release;

Customer self-support facilities. It modified manuals,

the help facility, and the technical-support website;

and

First-call resolution. It prevented callbacks by revis-

ing the TSR training materials and online knowledge

base, thus ensuring that TSRs would solve problems

correctly.

Understanding the Call-Stopping

Program’s Benefits

This program led directly to thousands of changes to

the client’s products that enhanced both the customer

experience and product reputation. It resulted in

changes to documentation and websites that allowed

customers to self-support without needing to contact

the call center for help. The VPO spent much less

time on the “call-center crisis.” Senior management no

longer felt the call center was mismanaged. To the BU,

the call center became a strategic asset that bridged

customer needs and product capabilities (Chase and

Garvin 1989).

It is notable that cost savings were not an explicit

driver in this project. We were not asked to provide

a financial justification to sell either the pilot pro-

gram or the full-scale call-stopping program. As part

of a budgeting process to extend our approach to the

client’s other business units (an engagement not dis-

cussed in this paper), we were asked to provide a

rough savings estimate. We used a “quick-and-dirty”

model to estimate that savings would be in the range

of $0.75–$3.3 million for the largest of three product

lines. A financial analyst in the client organization

devised a simplistic model that had great credence

in the organization. A referee proposed an enhanced

model. We conclude that the estimation of cost sav-

ings is an interesting research question; in the elec-

tronic companion, we provide more detail and a call

for further research. The electronic companion to this

paper is available as part of the online version that

can be found at http://interfaces.pubs.informs.org/

ecompanion.html.

Conclusions

The technical-support call center, although expen-

sive, was delivering poor customer service with no

prospects for improvement other than throwing more

money at the problem. In partnership with many peo-

ple in the client organization, we transformed the

Mehrotra and Grossman:

OR Process Skills Transform an Out-of-Control Call Center into a Strategic Asset

Interfaces 39(4), pp. 346–352, © 2009 INFORMS

351

call center into a strategic asset that used customer

feedback to enhance product quality; it also reduced

call volumes. This engagement was essential to the

long-term success of our young OR firm because it

was the springboard for extensive follow-on work

doing traditional model-and-algorithm OR.

The Importance of OR Process Skills

Before entering academia, the authors spent a com-

bined 16 years working full time in OR consulting

firms. We learned that much of the art of prac-

tice involves managing the process whereby a client

organization can benefit from data and models. We

learned that to grow an OR consulting business over

the long run, it is important to sell follow-on engage-

ments to current clients. A long-term consultant-client

relationship depends heavily on OR process skills.

Despite its importance to the practice of OR, we

knew little of OR process skills when we left school,

similar to many young OR professionals we speak to

today. In this section, we discuss OR process skills

(Table 1), place them into a larger framework of prac-

tice, and argue that they deserve explicit attention in

our research literature.

Some might argue that these OR process skills are

not OR at all, or that they are the same as process and

quality management. However, our goal as practition-

ers is neither quality nor process improvement per se;

it is to convince clients that our OR work, whether

in the form of mathematical insights or softer process

improvements, is worthy of their time and money.

OR process skills are central to that conversation. We

believe that the OR profession must value OR process

skills and nurture them in its practitioners.

OR Process Skills in a Larger

Framework of Practice

Fortuin et al. (1996) performed structured interviews

with OR practitioners. They provide a powerful

framework for understanding different types of OR

practice. This paper fits their category of “facilita-

tor OR” whereby the “support from OR is more

on issues of cooperation and integration (cross-

functional, multi-plant) and it resides less in the tools

or interactive computer systems than in the person of

the OR worker and his or her process skills” (Fortuin

et al. 1996, p. 9). This category of OR practice has a

strong pedigree relevant to this paper. Ackoff (1973)

discusses the importance of managing “messes” that

are complex systems of changing problems that inter-

act with each other; Pidd (1996) discusses situations

with extreme ambiguity and possibly disagreement.

Practitioners Must Do More Than Sell Tools

The impetus to focus narrowly on tools is a part of

OR’s historical evolution. Ackoff (1987) traces a devo-

lution of OR/MS from its roots as a “market-oriented

profession” that defined itself by the class of users

it addressed, through a stage of being an “output-

oriented profession” that defined itself by the class of

problems it solved, to becoming an “input-oriented pro-

fession” that defines itself by the class of tools it uses.

For OR practitioners, we see strong benefits to

a market orientation that focuses on the needs of

customers to solve operational problems using any

techniques that work. There is a far larger market for

consultants who can fix ambiguous, messy operational

problems than there is for people who are limited to

analyzing and optimizing stable business processes in

the presence of accurate data. It is desirable for the

OR practitioner to be effective working across func-

tional boundaries because clients often find it difficult

to do so. The practice of working through ill-defined

problems to improve business operations can lead to

opportunities to implement traditional OR solutions;

for example, Saltzman and Mehrotra (2001) describe

a subsequent project involving this client’s call cen-

ters. We note that as academics we can more easily

define ourselves based on deep, narrow expertise, in

part because we no longer need a stream of paying

clients to make a living.

Need for Research on OR Process Skills

We learned OR process skills via apprenticeship from

senior OR consultants, and by learning from our own

mistakes. Although these are expensive ways to learn,

they may be common; Corbett and van Wassenhove

(1993, p. 632) indicate that “Most knowledge about

the process of applying OR is implicit, and gener-

ally seems to be learned by trial and error.” We see

a need to make explicit this implicit knowledge by

performing research into the process of creating client

value using OR. We would also like to see the role of

these OR process skills receive more attention in the

presentation of traditional OR success stories.

Mehrotra and Grossman:

OR Process Skills Transform an Out-of-Control Call Center into a Strategic Asset

352

Interfaces 39(4), pp. 346–352, © 2009 INFORMS

Electronic Companion

An electronic companion to this paper is available as

part of the online version that can be found at http://

interfaces.pubs.informs.org/ecompanion.html.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the many people who guided us in our

practice careers. They are too many to name. Those who

stand out include Dean Boyd, Robert A. Luenberger, Stergios

Marinpoulos, Robert Perreault, Robert L. Phillips, Stephen

G. Regulinski, and C. S. Venkatakrishnan. The exposition

was greatly improved by the generous, detailed comments

from the associate editor, two anonymous referees, and

Sarah D. Saltzer.

References

Ackoff, R. L. 1973. Science in the systems age: Beyond IE, OR and

MS. Oper. Res. 21(3) 661–671.

Ackoff, R. L. 1987. Presidents’ symposium: OR, a post mortem.

Oper. Res. 35(3) 471–474.

Aksin, O. Z., M. Armony, V. Mehrotra. 2007. The modern call-

center: A multi-disciplinary perspective on operations manage-

ment research. Production Oper. Management 16(6) 665–688.

Andrews, B. H., S. M. Cunningham. 1995. L. L. Bean improves call

center forecasting. Interfaces 25(6) 1–13.

Andrews, B. H., H. L. Parsons. 1989. L. L. Bean chooses a telephone

agent scheduling system. Interfaces 19(6) 1–9.

Andrews, B. H., H. L. Parsons. 1993. Establishing telephone-agent

staffing levels through economic optimization. Interfaces 23(2)

15–20.

Atlason, J., M. A. Epelmen, S. G. Henderson. 2004. Call center

staffing with simulation and cutting plane methods. Ann. Oper.

Res. 127(1–4) 333–358.

Avramidis, A. N., A. Deslauriers, P. L’Ecuyer. 2004. Modeling

daily arrivals to a telephone call center. Management Sci. 50(7)

896–908.

Aykin, T. 1996. Optimal shift scheduling with multiple break win-

dows. Management Sci. 42(4) 591–602.

Aykin, T. 2000. A comparative evaluation of modeling approaches

to the labor shift scheduling problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 125(2)

381–397.

Brigandi, A. J., D. R. Dargon, M. J. Sheehan, T. Spencer. 1994.

AT&T’s call processing simulator (CAPS) operational design

for inbound call centers. Interfaces 24(1) 6–28.

Caprera, A., M. Monaci, P. Toth. 2003. Models and algorithms for a

staff scheduling problem. Math. Programming 98(1–3) 445–476.

Chase, R. B., D. A. Garvin. 1989. The service factory. Harvard Busi-

ness Rev. 67(4) 61–70.

Corbett, C. J., L. N. van Wassenhove. 1993. The natural drift: What

happened to operations research? Oper. Res. 41(4) 625–640.

Fortuin, L., P. van Beek, L. van Wassenhove. 1996. OR at Work:

Practical Experiences of Operational Research. Taylor & Francis,

Bristol, PA.

Gans, N., G. Koole, A. Mandelbaum. 2003. Telephone call centers:

Tutorial, review and research prospects. Manufacturing Service

Oper. Management 5(2) 79–141.

Green, L. V., P. J. Kolesar, J. Soares. 2003. An improved heuristic

for staffing telephone call centers with limited operating hours.

Production Oper. Management 12(1) 46–61.

Green, L. V., P. J. Kolesar, W. Whitt. 2007. Coping with time-varying

demand when setting staffing requirements for a service sys-

tem. Production Oper. Management 16(1) 13–39.

Grossman, T. A., D. Samuelson, S. Oh, T. R. Rohleder. 2001. Call

centers. S. I. Gass, C. M. Harris, eds. Encyclopedia of Operations

Research and Management Science, 2nd ed. Kluwer Academic

Publishers, Boston, 73–76.

Koole, G., A. Mandelbaum. 2002. Queueing models of call centers:

An introduction. Ann. Oper. Res. 113(1–4) 41–59.

Mehrotra, V., J. Fama. 2003. Call center simulation modeling: Meth-

ods, challenges, and opportunities. S. Chick, P. J. Sanchez,

D. Ferrin, D. J. Morrice, eds. Proc. 2003 Winter Simulation Conf.,

Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, Piscataway, NJ,

135–143.

Pidd, M. 1996. Tools for Thinking: Modeling in Management Science.

John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Saltzman, R. M., V. Mehrotra. 2001. A call center uses simulation to

drive strategic change. Interfaces 31(3) 87–101.

The editor in chief has received a verification letter

attesting to the impact of this work on the firm. The

firm has requested to remain anonymous.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Babysitting a Billionaire 2 Out Of Control Nina Croft

Out of Control

Oh Yum! 21 Eve Savage Out of Control ( MWYM )

The impact of network structure on knowledge transfer an aplication of

Purani Jeans Out of control munde POZA KONTROLĄ UMYSŁU

Out of the Armchair and into the Field

[Mises org]George,Henry Protection Or Free Trade An Examination of The Tariff Question, With

The divine kingship of the Shilluk On violence, utopia, and the human condition, or, elements for a

The contribution of symbolic skills to the development of an explicit theory of mind

An%20Analysis%20of%20the%20Data%20Obtained%20from%20Ventilat

Does the number of rescuers affect the survival rate from out-of-hospital cardiac arrests, MEDYCYNA,

Breaking out of the Balkans Ghetto Why IPA should be changed

How does personality matter in marriage An examination of trait anxiety, interpersonal negativity, a

Effect of?renaline on survival in out of hospital?rdiac arrest

Hospital?re?ter resuscitation from out of hospital?rdiac arrest The emperor's new clothes

How to Get the Most Out of Conversation Escalation

Clint Leung An Overview of Canadian Artic Inuit Art (2006)

%d0%9e%d1%81%d1%82%d0%b0%d0%bf%d1%87%d1%83%d0%ba Cossack Ukraine In and Out of Ottoman Orbit, 1648 1

więcej podobnych podstron