Risk for Suicide Attempts

Among Adolescents Who

Engage in Non-Suicidal

Self-Injury

Jennifer J. Muehlenkamp and Peter M. Gutierrez

The current study examined whether common indicators of suicide risk differ between

adolescents engaging in non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) who have and have not

attempted suicide in an effort to enhance clinicians’ ability to evaluate risk for suicide

within this group. Data were collected from 540 high school students in the Midwest

who completed the RADS, RFL-A, SIQ, and SHBQ as part of a larger adolescent

risk project. Results suggest that adolescents engaging in NSSI who also attempt

suicide can be differentiated from adolescents who only engage in NSSI on measures

of suicidal ideation, reasons for living, and depression. Clinical implications of the

findings are discussed.

Keywords

adolescents, deliberate self-harm, non-suicidal self-injury, suicide

There is growing interest in understanding

the psychological correlates and psychiatric

morbidity of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI)

in adolescents. Prevalence rates of NSSI

among adolescent samples range from

14% to 40% in the community (Muehlen-

kamp & Gutierrez, 2004; Ross & Heath,

2002) and from 40% to 61% in inpatient

samples

(Darche,

1990;

DiClemente,

Ponton, & Hartley, 1991). There is some

evidence to suggest that the incidence of

NSSI may be increasing (Hawton, Fagg,

Simkin et al., 1997; Olfson, Gameroff,

Marcus et al., 2005) within this age group.

The increasing rate of NSSI is of particular

concern because some individuals with his-

tories of NSSI are at greater risk for suicide

(Dulit, Fryer, Leon et al., 1994; Zlotnick,

Donaldson, Spirito et al., 1997), although

not all self-injurers will attempt suicide

(Kessler, Borges, & Walters, 1999). Research

to date has not progressed far beyond docu-

menting an association between increased

risk for suicide and NSSI, limiting clinicians’

ability to evaluate risk for suicide attempts

within

this

at-risk

group.

Therefore,

additional studies examining psychological

correlates that may differentiate adolescents

engaged in NSSI who attempt suicide from

those who do not attempt suicide are needed

to better inform current knowledge and

clinical practice.

Non-suicidal self-injury is conceptua-

lized as behavior existing along a continuum

of self-harm on which suicide is the final and

most severe endpoint (O’Carroll, Berman,

Marris et al., 1996; Stanley, Winchel, Mol-

cho et al., 1992). Consequently, there is a

potential for shared psychiatric morbidity

and other risk factors underlying both NSSI

Archives of Suicide Research, 11:69–82, 2007

Copyright # International Academy for Suicide Research

ISSN: 1381-1118 print/1543-6136 online

DOI: 10.1080/13811110600992902

69

and suicide attempts. For example, research

has documented that childhood sexual

abuse, depression, interpersonal or family

conflict, isolation or loneliness, impulsivity,

borderline personality disorder, and psychi-

atric illness are among the risk factors for

both NSSI and suicidal behavior (Brent,

Perper, Mortiz et al., 1993b; Garrison,

Addy, McKeown et al., 1993; Maris, Ber-

man, & Silverman, 2000; Walsh, 2005).

These shared risk factors make it difficult

to clarify potential suicide risk among indi-

viduals engaged in NSSI, and it is unknown

whether there are gradations of severity on

these variables between those with a history

of NSSI and=or suicide attempts. Identifying

potential differences in symptom severity

among individuals who engage in NSSI

and=or suicide attempts is important to

improving risk assessment, but there is little

research in this area.

We were able to identify only two stu-

dies (Guerton, Lloyd-Richardson, Spirito

et al., 2001; Stanley, Gameroff, Michalsen

et al., 2001) that have examined potential

differences

in

psychosocial

correlates

between

NSSI

and

suicide

attempts.

Stanley and colleagues (2001) examined

potential psychosocial differences in 53

adult women with borderline personality

disorder who presented to a psychiatric

treatment

facility

following

a

suicide

attempt. Individuals with both NSSI and

suicide attempts were found to have signifi-

cantly higher levels of depression, hope-

lessness, aggression, anxiety, impulsivity,

and suicidal ideation. Guertin et al. (2001)

conducted a similar study in a sample of

95 adolescents presenting to a child psychi-

atric clinic following a suicide attempt, of

which 54.7% had a history of at least one

act of NSSI. Results indicated that indivi-

duals who had engaged in both NSSI

and had made a suicide attempt were more

likely

to

be

diagnosed

with

major

depression, dysthymia, or oppositional

defiant disorder. Additionally, the NSSI

and suicide attempt group had significantly

higher levels of depression, loneliness,

anger, and risk taking behaviors than the

suicide attempt only group.

These findings enhance our under-

standing of suicide attempters, confirming

ideas that individuals who engage in a range

of self-harming behaviors (e.g., NSSI, risk

taking, suicide attempts) are likely to

experience increased psychological impair-

ment. However, neither study provided

data that would improve understanding of

psychiatric differences between individuals

engaged in NSSI who do and do not

attempt suicide. Furthermore, these studies

did not explore what aspects of the psychi-

atric disorders or psychosocial correlates

may have contributed to increased risk

for a suicide attempt. The findings are also

restricted to clinical populations who were

accessing treatment, making it difficult to

determine whether similar patterns of

results would generalize beyond such sam-

ples. Given the increased prevalence of

NSSI within community samples of adoles-

cents, it is imperative to expand the find-

ings by Guertin et al. (2001) and Stanley

et al. (2001) to non-clinical samples, as well

as to determine if similar patterns of suicide

risk exist for adolescents who have a his-

tory NSSI.

Another reason to further examine dif-

ferences in risk factors such as depression

and suicidal ideation within samples of

individuals who engage in NSSI, is that

NSSI is identified as a potential precursor

to suicide attempts. Joiner (2005) has pro-

posed a model of suicide in which he posits

that participation in self-injurious behaviors

over time desensitizes an individual to self-

harm. This desensitization to self-harm is

one mechanism which increases risk for

suicide attempts because the person has

habituated to fears and physical pain asso-

ciated with self-injury. Consequently, a

person with a history of NSSI more readily

acquires the capacity to engage in lethal

acts of self-harm. This understanding of

NSSI’s potential relationship to suicide

Risk For Suicide

70

VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1 2007

supports the need to further clarify indica-

tors of risk that may signal a shift from

NSSI to a suicide attempt.

Examining potential differences in

levels of depression and suicidal ideation

between

self-injuring

adolescents

who

attempt suicide and those who do not can

also inform clinical practice. However,

understanding of NSSI and risk for suicide

within this group may be improved by

examining additional factors that could

shed light on suicide risk. Reasons for liv-

ing have been identified as important pro-

tective

factors

against

suicide-related

behavior in both adolescent and adult sam-

ples (e.g., Gutierrez, Osman, Kopper, et al.,

2000; Osman, Downs, Kopper et al., 1998).

Reasons for living have also been shown to

accurately differentiate adolescents at high

and low risk for suicide (Gutierrez, Osman,

Kopper et al., 2000); however there are no

known studies that have examined how

reasons for living may affect suicide risk

in self-injuring samples. From a theoretical

viewpoint, NSSI is often conceptualized as

an emotion regulation strategy (Nock &

Prinstein, 2004), suggesting that individuals

engaged in NSSI are motivated to live but

have difficulty coping with distress. Con-

sistent with this hypothesis, Muehlenkamp

and Gutierrez (2004) found that adoles-

cents who had a history of NSSI had more

positive attitudes towards life than adoles-

cents who attempted suicide. It is possible

that individuals engaged in NSSI would

identify greater numbers of reasons for liv-

ing than those who attempt suicide because

they have a desire to live. Therefore, rea-

sons for living may also be able to indicate

risk for (or protection against) suicide

attempts within self-injuring adolescents.

To date, the relationship between reasons

for living and NSSI has not been examined,

nor is it known whether reasons for living

could act as an indicator of risk for suicide

attempts within a sample of self-injurers.

Current

understandings

of

NSSI

and suicide suggest that there should be

gradations in the severity of pathology

associated with each behavior. Differences

are expected to exist on factors such as sui-

cide ideation, depression, and reasons for

living; yet, there are few studies evaluating

this assumption. In addition to variations

in severity, there may also be quantitative

differences within specific elements of

these

psychosocial

correlates

between

NSSI and suicide, but we are unaware of

any research examining this idea. The clo-

sest approximation is research exploring

specific traits associated with NSSI such

as

increased

aggression=hostility

and

impulsivity (Brent, Johnson, Bartle et al.,

1993a; Kumar, Pope, & Steer, 2004; Ross

& Heath, 2003). Results from studies in

this area suggest that adopting a symp-

tom-based

approach

to

understanding

NSSI may be warranted over approaches

that attempt to understand the behavior

within the context of specific disorders. A

study by Muehlenkamp, Jacobson, and

Miller (2005) further supports efforts to

understand NSSI from a symptom-based

perspective, finding that specific symptoms

of impulsivity, anger, and chronic emptiness

predicted NSSI in an outpatient sample of

adolescents better than axis I diagnoses

alone. Examining differences in the types

of depressive symptoms and reasons for

living endorsed by adolescents engaged in

NSSI who have and have not attempted

suicide would likely enhance our under-

standing of risk for these behaviors.

In

summary,

researchers

have

attempted

to

establish

a

theoretical

differentiation between NSSI and suicide

attempts on a number of psychosocial cor-

relates to better understand these behaviors.

Many of these studies have been limited in

their ability to identify factors that would

indicate heightened risk for a suicide

attempt within groups who engage in NSSI,

which is important due to the documented

risk for suicide associated with NSSI beha-

viors. The current study expands upon

research conducted by Guertin et al. (2001)

J. Muehelenkamp and P. Gutierrez

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

71

and Stanley et al. (2001) with the goal of

identifying group differences that can

inform assessments of risk for suicide

within a community sample of adolescents

who engage in NSSI.

We hypothesized that adolescents who

have a history of NSSI would report lower

levels of depressive symptoms and suicidal

ideation than individuals with a history

of both NSSI and a suicide attempt. In

addition, it was hypothesized that adoles-

cents with both NSSI and a suicide attempt

would report fewer reasons for living than

adolescents who engaged in only NSSI. We

also explored potential differences in spe-

cific aspects of depressive symptoms and

reasons for living between the adolescent

groups to expand our understanding of risk

associated with the behaviors. Due to the

exploratory nature of the secondary analy-

ses, no hypotheses were specified.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Participants were recruited as part of an

ongoing suicide screening project at an

urban high school in the Midwest. The cur-

rent data were collected over the course of

three academic years from 2001–2004. Data

were collected from 540 adolescents of

whom 62.3% were female. The mean age

of the participants was 15.53 (SD ¼ 1.42).

Among the participants, 48.3% identified

themselves as Caucasian, 28.4% as African

American, 8.1% as Hispanic, 11.8% as

Multi-ethnic, and 2.0% as Asian. Seven

participants (1.4%) did not report their

ethnicity.

Participant

recruitment

occurred

through announcements and parent letters

handed out in English, Math, Social

Studies, Psychology, and Drama classes.

Because we do not know the total enroll-

ment of classes in which recruitment

occurred, and due to variations in the way

consent data were tracked across the three

years of the study, participation rates are

difficult to characterize. However, infor-

mation obtained from the school adminis-

tration suggests that the selected classes

contained the majority of freshman and

seniors enrolled in any given year, with

lower representation of sophomores and

juniors. We estimate that the parents of

1200 students were contacted regarding

the study and that we averaged a 60%

return rate, with the majority giving con-

sent. Across the three years, on average,

86.9% of students with parental consent

were able to be invited to participate in

the study. The remaining 13.1% were

either absent on the day of data collection,

were unable to participate due to classroom

activities, or had moved. While these

participation estimates are not as high as

one would like, and may not have resulted

in a purely representative sample, they

seem to be comparable to other studies

relying on school-based recruitment and

data collection. Students from whom we

obtained parental consent to participate,

and who gave their assent (95.8%), were

excused from their classrooms to complete

a packet of questionnaires within small

groups in a semi-private room of the

school library. All questionnaires were

counterbalanced with the exception of the

demographic form, which always occurred

first. It took approximately 50 minutes to

complete the packet. Upon completion,

students’ responses were examined for

indicators of depression or suicide risk.

Participants endorsing critical items were

spoken with privately by the examiner

about their safety and were given an appro-

priate referral to the school psychologist

who followed up the student’s parents if

the student was currently suicidal.

Measures

Reynolds

Adolescent

Depression

Scale

(RADS;

Reynolds, 1987).

This 30-item self-report

Risk For Suicide

72

VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1 2007

instrument is designed to measure depress-

ive symptoms in adolescents ages 13 to 18.

During the course of the current study, the

second edition of the RADS (RADS-2;

Reynolds, 2002) was released. The content

of items and scoring did not change, but

updated norms and interpretation infor-

mation became available which were used

for all analyses reported here. The RADS

breaks down depressive symptoms into

four subscales: dysphoric mood, anhedo-

nia, negative self-evaluation, and somatic

complaints. Each item is scored on a 4-

point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost

never) to 4 (most of the time). Scores are

obtained by summing responses and range

from 30–120 points, with higher scores

representing a greater level of depressive

symptoms. The RADS has demonstrated

strong reliability and validity (Reynolds,

1987; 2002). The internal consistency of

the RADS in the current study was a ¼ .94.

Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ; Reynolds,

1988).

The SIQ is a 30-item self-report

measure of current suicidal ideation for

adolescents in grades 10 through 12. Parti-

cipants respond to items on a 7-point scale

indicating the frequency of their thoughts

during

the

last

month.

Frequency

responses range from 6 (almost every

day) to 0 (I never had the thought), creating

a range of scores from 0 to 180, with

higher scores representing higher levels of

suicidal ideation. The SIQ has demon-

strated good internal consistency, and has

adequate concurrent and construct validity

(Reynolds, 1988). The SIQ-JR is a 15-item

version of the SIQ that was administered to

freshman participants since it is appropriate

for use with adolescents in grades 7

through 9. The SIQ-JR has also demon-

strated

good

psychometric

properties

(Range & Knott, 1997; Reynolds, 1988).

In the current sample, an internal consist-

ency of a ¼ .94 was obtained. Based on

tables provided in the manual, total scores

on the SIQ and SIQ-JR were transformed

into percentile scores so that data from

the two versions could be combined during

analyses.

Reasons for Living Inventory for Adolescents (RFL-A;

Osman, Downs, Kopper et al., 1998).

The RFL-A

consists of 32 items and five subscales

measuring reasons adolescents give for not

committing suicide. Items are rated on a

6-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all impor-

tant) to 6 (extremely important). Scores are

obtained by averaging responses on each sub-

scale, with low scores being indicative of

fewer reasons for living, and higher suicide

risk. Total scores are calculated by averaging

the subscale scores. Good internal consist-

ency of the RFL-A has been demonstrated

(Osman, Downs, Kopper et al., 1998), and

an alpha of .95 was obtained in the current

sample. Adequate concurrent validity has

been shown through significant negative cor-

relations between RFL-A scores and scores

on measures of suicidal behaviors, hopeless-

ness, and depression (Gutierrez, Osman,

Kopper et al., 2000; Osman, Downs,

Kopper et al., 1998). The RFL-A has also

demonstrated discriminant validity between

psychiatric suicidal adolescents and norma-

tive high school students (Gutierrez, Osman,

Kopper et al., 2000).

Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire (SHBQ; Gutierrez,

Osman, Barrios et al. 2001).

The SHBQ is a

self-report measure consisting of forced-

choice and free-response items assessing

the degree to which participants have

engaged in self-harmful activities. The

SHBQ consists of four distinct sections

that inquire about the incidence and fre-

quency of non-suicidal self-harm, suicide

attempts,

suicide

threats,

and

suicide

ideation. Each section contains follow-up

questions about features of the target

behavior, such as the methods used and

frequency of the behavior. The SHBQ

defines NSSI behaviors as acts of inten-

tional self-harm without intent to die and

J. Muehelenkamp and P. Gutierrez

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

73

defines suicidal behavior as an act of self-

harm with any intent to die. The SHBQ

has shown good internal consistency with

alpha estimates from .89 to .96 among

the four sections (Gutierrez, Osman,

Barrios et al., 2001). A total score alpha

of .93 was obtained in the current sample.

Tests

of

convergent validity

revealed

SHBQ total scores were correlated with

existing measures of suicidal behavior

(r ¼ .34 to .70; Gutierrez, Osman, Barrios

et al., 2001).

Based on their responses to the SHBQ,

participants were divided into four cate-

gories of no self-harm (NoSH), non-

suicidal self-injurious behavior only (NSSI),

suicide attempts only (SA), and both self-

injury and suicide attempts (NSSI þ SA).

Responses describing the method of self-

harm (e.g., burn, cut) were coded for

descriptive data. It should be noted that

the section of the SHBQ assessing suicidal

ideation taps lifetime thoughts of suicide,

as distinct from current thoughts assessed

by the SIQ. A participant could indicate

that all of their thoughts about suicide

occurred within the same time frame as

assessed by the SIQ, in which case their

scores on that subscale would overlap with

their SIQ total score. Because the SHBQ

was used to classify students based on the

content of their responses, rather than

from the calculated subscale scores, we

do not believe this potential overlap poses

a problem for analyses.

RESULTS

Incidence and Description of Self-Harm

Non-suicidal self-injury was reported by

23.2% (n ¼ 125) of the sample, and

8.9% (n ¼ 48) reported making a suicide

attempt. After dividing participants into

the four self-harm categories, 75.2%

(n ¼ 406) fell into the NoSH group,

16.1% (n ¼ 87) fell into the NSSI only

group, 1.9% (n ¼ 10) comprised the SA

group, and 7.0% (n ¼ 38) comprised the

NSSI þ SA group. There were no signifi-

cant sex differences across three of the

self-harm groups, but a significant sex dif-

ference was found within the NSSI þ SA

group, v

2

(1) ¼ 4.63, p < .05. Females were

more likely to report both engaging in

NSSI and having attempted suicide than

were males. A significant difference was

also found for ethnicity across the self-

harm groups, v

2

(3) ¼ 9.53, p < .05, with

Caucasians reporting significantly more

self-harm than non-Caucasians, v

2

(1) ¼

8.83, p < .01. There were no significant dif-

ferences in self-harm status within the eth-

nic minority groups, v

2

(3) ¼ 8.83, p < .01.

The ethnic composition of each self-harm

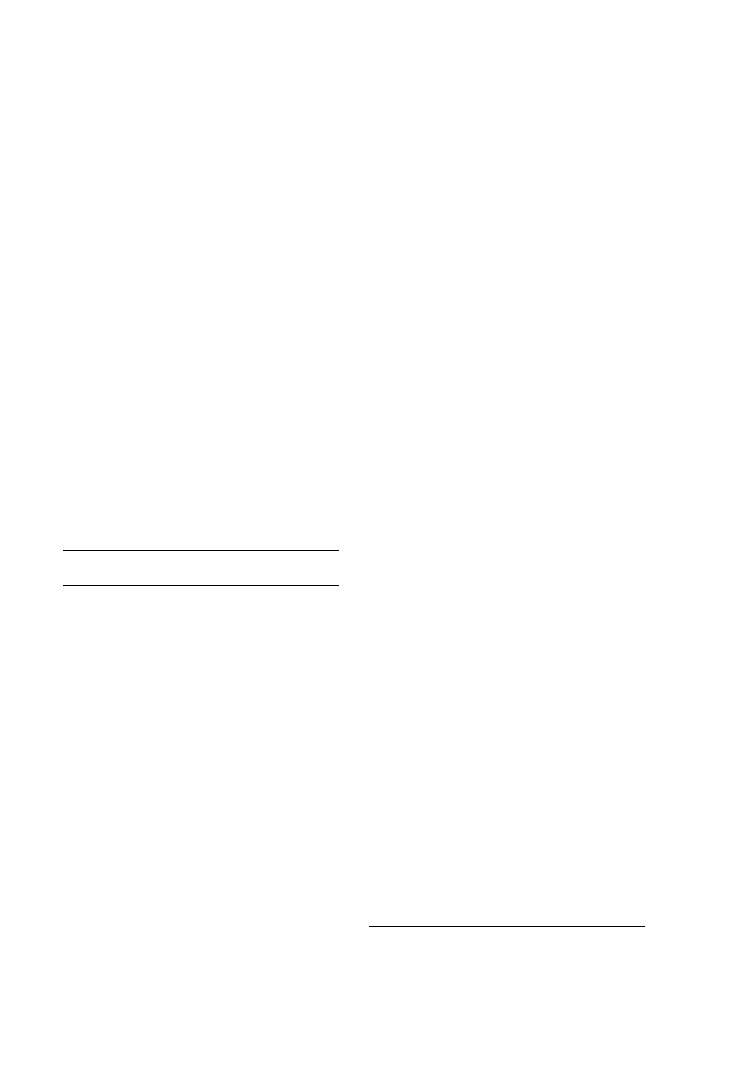

group is reported in Table 1.

Many participants reported that the

NSSI began at age 13 (15.1%) or 14

(28.4%). Among those reporting NSSI

behavior, 32 (25.6%) reported one inci-

dent, 43 (34.4%) reported between two

and three incidents, and 27 (21.6%)

reported four or more incidents (23 did

not report the frequency of their NSSI).

Seventy four (59.2%) participants reported

at least one act of NSSI in the past year. Of

participants reporting a suicide attempt, 21

(43.8%) reported one attempt, another 15

(31.2%) reported two or three attempts,

and 6 (12.5%) reported attempting suicide

four or more times (6 participants did not

report a frequency). Sixteen participants

(33.3%) reported making a suicide attempt

within the past year. There was not a

significant difference in the frequency

of NSSI acts between the NSSI and

NSSI þ SA groups, t(121) ¼ .594, p > .05,

suggesting that the groups were compara-

ble in the number of times they had self-

injured without suicidal intent. Descriptive

data regarding the specific methods of

self-harm and number of methods used

are reported in Table 1.

Risk For Suicide

74

VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1 2007

Group Differences

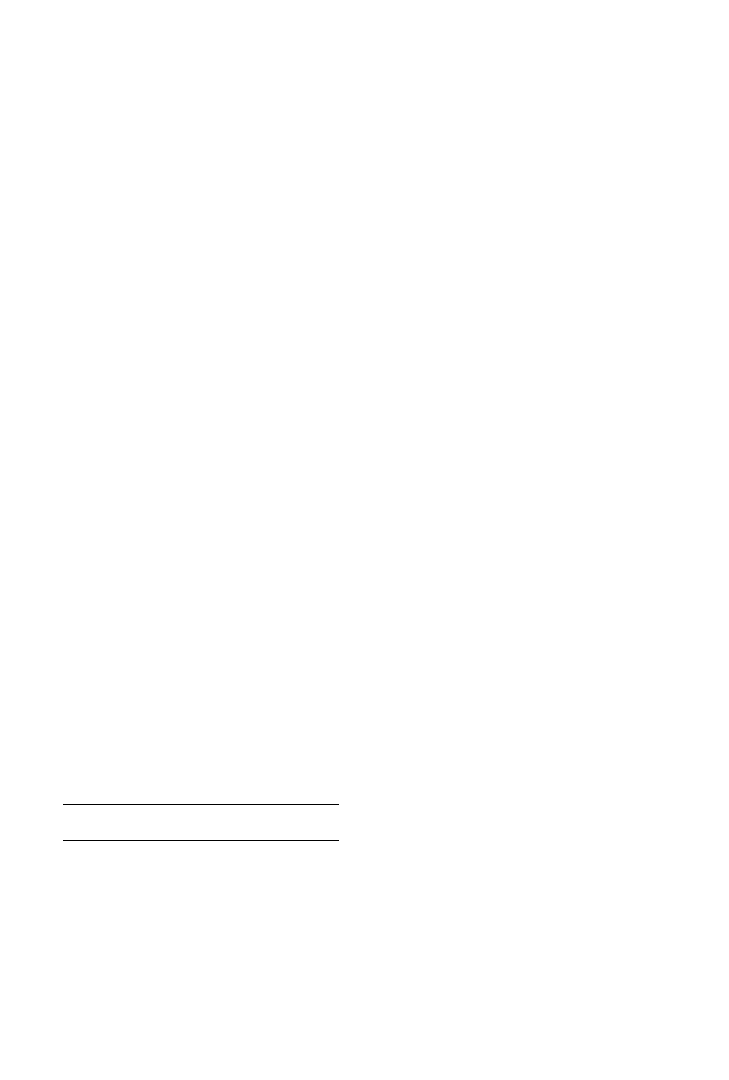

A series of ANCOVAs with sex and time

since last act of self-harm as covariates

were used to assess differences among the

NSSI, SA, NSSI þ SA, and NoSH groups

on levels of depression, suicidal ideation,

and reasons for living. The means, standard

deviations, and reliability of each measure

are presented in Table 2. Given the number

of planned contrasts conducted, the risk of

type I error was reduced by adopting a con-

servative p-value based on a Bonferroni

correction (.05=6; p < .001) to determine

statistical significance. Significant between

groups differences were found on the

RADS,

F

(3,532) ¼ 37.44,

p <

.000,

g

2

¼ .176;

SIQ,

F

(3,531) ¼ 57.28,

p <

.000, g

2

¼ .244; and the RFL-A, F

(3,530) ¼ 35.28, p < .000, g

2

¼ .166. The

covariate of time since last act of self-harm

did not have a significant effect on any of

the dependent variables (p > .20 for all),

so it was dropped in subsequent analyses.

Planned follow-up pairwise compari-

sons revealed significant differences between

the NoSH group and the NSSI and

NSSI þ SA groups on all dependent vari-

ables (p ¼ .000 for each). The only signifi-

cant difference between the NoSH and SA

group was on the SIQ (p ¼ .000). Parti-

cipants reporting some type of self-harm

had greater levels of depression and suicidal

ideation, as well as fewer reasons for living

than participants who did not report a

history of self-harm. When comparing the

NSSI, SA, and NSSI þ SA groups, signifi-

cant differences emerged between the NSSI

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Data for the Self-Harm Categories

Feature

NoSH (n ¼ 406)

NSSI (n ¼ 87)

SA (n ¼ 10)

NSSI þ SA (n ¼ 38)

Gender

Female

245

52

8

30

Ethnicity

Caucasian

182

50

5

25

African American

133

13

2

6

Hispanic

30

9

2

3

Multi-Ethnic

48

12

1

3

Other Race=Ethnicity

10

2

0

1

Method of Self-Harm

Cut

-

48

3

14

Scratch

-

36

0

0

Burn

-

5

0

0

Self-Hit

-

15

0

0

Punch=Kick

-

9

0

0

Banging

-

3

0

0

Other Method

-

16

8

4

Use of 1 Method

-

61

9

16

Use of 2 or More Methods

-

17

1

20

The values represent n-size for each feature. There are different amounts of missing data for each of the cate-

gories so the numbers reported will not add up to the expected totals. NoSH ¼ No Self-Harm group,

NSSI ¼ Non-suicidal self-injury only group, SA ¼ Suicide Attempt only group, NSSI þ SA ¼ both Non-suici-

dal self-injury and Suicide Attempt group.

J. Muehelenkamp and P. Gutierrez

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

75

and NSSI þ SA groups on the SIQ,

F

(2,129) ¼ 10.96,

p <

.001,

g

2

¼ .145,

and RFL-A, F(2,129) ¼ 7.18, p < .001,

g

2

¼ .101, with the NSSI þ SA group

reporting greater suicidal ideation and fewer

reasons for living than the NSSI group.

Differences between the NSSI and NSSI þ

SA groups on the RADS suggest that the

NSSI þ SA group may have slightly higher

levels of depressive symptoms, F(2,129) ¼

3.46, p ¼ .03, g

2

¼ .045, but this needs to

be interpreted with caution given the signifi-

cance value and small effect size. The SA

group did not significantly differ from either

the NSSI or NSSI þ SA group on any of the

dependent variables. This lack of significance

is likely the result of the small n-size leading

to underpowered analyses (power ¼ .27).

Consequently, the SA group was excluded

from further analyses and interpretations

regarding this group will not be made.

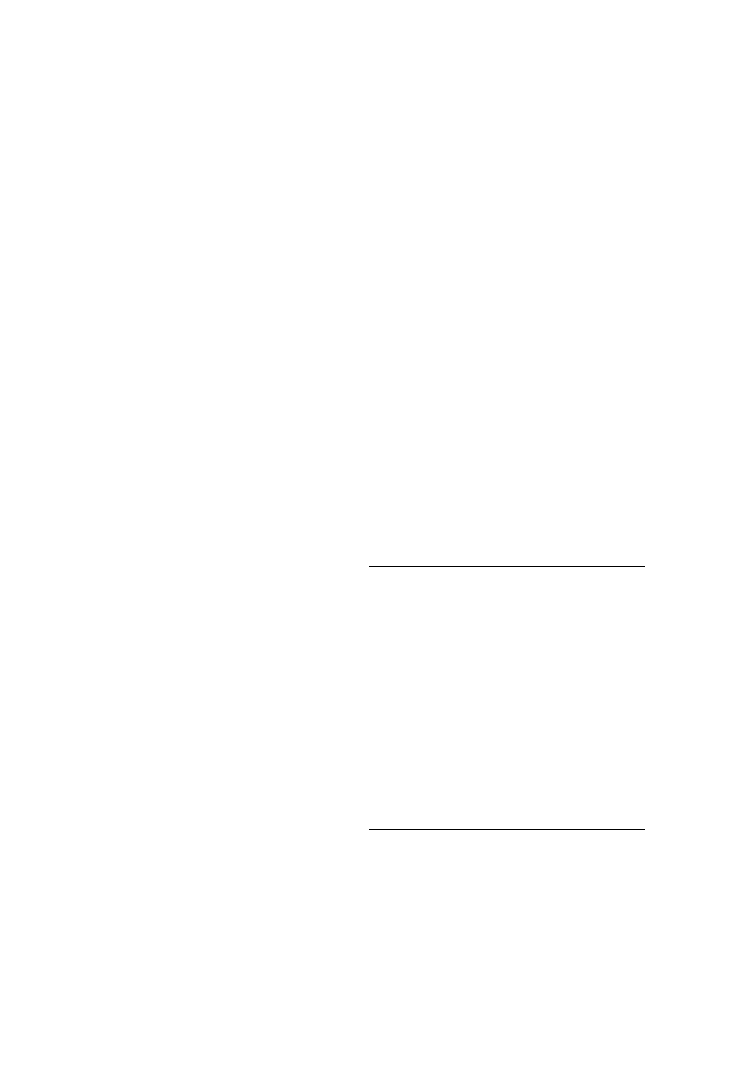

Follow-up a priori planned contrasts

were used to explore differences in the

specific symptoms of depression and com-

ponents of reasons for living between the

NSSI and NSSI þ SA groups. We included

depressive

symptoms

in

the

analyses

because the omnibus test demonstrated a

possible difference between the groups,

suggesting there may be a unique disparity

on one or more symptom areas of

depression measured by the RADS. Results

are presented in Table 3. There were

significant differences between groups on

the RADS subscales of anhedonia and

negative self-evaluation (score excluded

the suicide item to prevent an inflated

relationship), with the NSSI þ SA group

reporting higher levels of each symptom

cluster. On the RFL-A, significant differ-

ences were found on the future orientation,

suicide related concern, family alliance, and

self-acceptance subscales (see Table 3),

with the NSSI group reporting a greater

number of reasons for living associated

with each category.

TABLE 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Reliability of Variables Across Self-Harm Groups

Variable

NoSH (n ¼ 406)

NSSI (n ¼ 87)

SA (n ¼ 10)

NSSI þ SA (n ¼ 38)

a

RADS

.94

Mean

56.28

70.75

63.40

77.24

(SD)

(14.68)

(16.40)

(18.17)

(16.41)

Range

0–104

30–99

41–91

45–111

% Over cut-off

12.32

43.68

30.00

52.63

SIQ

a

.94

Mean

45.77

70.61

72.90

86.27

(SD)

(24.48)

(18.30)

(23.30)

(11.19)

Range

9–98

21–99

23–94

53–99

% Over cut-off

6.12

27.59

40.00

60.53

RFL-A

.95

Mean

5.04

4.47

4.49

3.80

(SD)

(.809)

(.853)

(.802)

(1.03)

Range

.14–6.0

1.89–5.82

3.60–6.0

1.09–6.0

a

SIQ scores are percentile scores. NoSH ¼ No Self-Harm group, NSSI ¼ Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Only group,

SA ¼ Suicide Attempt only group, NSSI þ SA ¼ both Non-Suicidal Self-Injurious and Suicide Attempt group.

RADS ¼ Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale, SIQ ¼ Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire, RFL-A ¼ Reasons

for Living Inventory for Adolescents. ‘‘% Over cut-off’’ represents participants with scores at or above the

clinically significant cut-off scores (84th percentile on SIQ; Score of 76 or greater on RADS).

Risk For Suicide

76

VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1 2007

DISCUSSION

The present study identified significant dif-

ferences in the level of suicidal ideation,

reasons for living, and depressive symp-

toms between adolescents with a history

of NSSI who had and had not attempted

suicide. Specifically, self-injuring adoles-

cents who attempted suicide reported

greater levels of suicidal ideation, signifi-

cantly fewer reasons for living, and may

be more likely to experience higher levels

of depressive symptoms. Both groups

reported significantly greater depressive

symptoms, suicidal ideation, and fewer rea-

sons for living than the group without any

self-harm. These findings offer empirical

data to suggest that NSSI may be concep-

tualized along a continuum of self-harm,

placing NSSI below suicide attempts in

terms of severity of the behavior and corre-

sponding psychological correlates. Addition-

ally, the results from this study appear

consistent with the theoretical understanding

of NSSI as a dysfunctional coping strategy.

Individuals engaged in NSSI were able to

identify a number of reasons to keep living,

suggesting that they are motivated to live,

which is antithetical to the motivations

underlying suicidal behavior (e.g., desire not

to live). This interpretation is congruent with

Muehlenkamp and Gutierrez’s (2004) find-

ing that self-injuring adolescents have a

greater attraction to life than those who

attempt suicide, indicating adolescents’ per-

spectives on life are important variables to

consider during treatment, and when asses-

sing risk for suicide. However, our inability

to make comparisons with the group of ado-

lescent who had only made suicide attempts

(due to the small n) limits the scope of this

interpretation.

Our finding that adolescents engaged

in NSSI who attempt suicide have higher

levels of suicidal ideation than those who

do not attempt suicide appears intuitive

and replicates numerous studies document-

ing that thoughts about suicide are associa-

ted with greater risk (e.g., Beautrais, Joyce,

& Mulder, 1996; Brent, Perper, Moritz et al.,

1993; De Man & Leduc, 1995; King,

Hovey, Brand et al., 1997; Kovacs, Gold-

ston, & Gatsonis, 1993). However, suicidal

ideation is often overlooked as a risk factor

within studies of NSSI because NSSI is

defined as a behavior void of any thoughts

TABLE 3.

Specific Content Differences between NSSI and NSSI þ SA Groups

Dependent Variable

NSSI Mean (SD)

NSSI þ SA Mean SD

df

t-value

p-level

RADS

Dysphoric Mood

2.60 (.644)

2.71 (.745)

535

.884

.377

Anhedonia

1.97 (.478)

2.19 (.561)

535

2.43

.015

Negative Self-Evaluation

2.23 (.736)

2.54 (.733)

535

2.34

.020

Somatic Complaints

2.65 (.644)

2.86 (.680)

535

1.65

.100

RFL-A

Future Orientation

4.94 (.937)

4.37 (1.37)

534

3.17

.002

Suicide Related Concerns

3.96 (1.50)

2.86 (1.60)

534

4.06

.000

Family Alliance

4.30 (1.20)

3.66 (1.38)

534

2.97

.003

Peer Acceptance & Support

4.65 (1.21)

4.25 (1.33)

533

1.92

.055

Self-Acceptance

4.49 (1.15)

3.88 (1.22)

534

2.93

.004

Significant values are in bold. RADS ¼ Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale; RFL-A ¼ Reasons for Living

scale, Adolescent version; NSSI ¼ non-suicidal self-injury only group, NSSI þ SA ¼ group with both non-sui-

cidal self-injury and a suicide attempt.

J. Muehelenkamp and P. Gutierrez

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

77

of death. The results we found provide

empirical evidence supporting the impor-

tance of monitoring suicidal ideation when

working with adolescents who are engaging

in NSSI in order to identify heightened

risk for suicide, and potentially to prevent

suicide attempts within this at-risk group.

Contrary to our hypotheses, level of

depressive symptoms did not significantly

differ between the NSSI and NSSI þ SA

groups (p ¼ .03); however, results suggest

a potential for the NSSI þ SA group to

have more severe levels of depressive

symptoms. Future studies in this area will

have to clarify our findings. We did find

that adolescents engaged in NSSI reported

significantly greater depressive symptoms

than those who did not have a history of

NSSI, which is consistent with previous

studies using community samples (e.g.,

Ross & Heath, 2002). What these results

appear to demonstrate is that adolescents

who engage in NSSI are experiencing a

significant level of distress relative to ado-

lescents without a history of self-harm.

Therefore, depression can be viewed as a

correlate of NSSI. Severity of depressive

symptoms may be an element that increases

risk for making a suicide attempt within sub-

groups of NSSI adolescents, but the findings

are inconclusive at this point. Other

researchers have noted that depressive

symptoms alone may not be strong predic-

tors of suicide (Mann, Waternaux, Haas

et al., 1999). Instead, it may be that other fac-

tors interact with a high level of depression

to increase risk for attempting suicide, or as

Joiner (2005) suggests, that high levels of

emotional distress coupled with repeated

acts of NSSI combine to propel an individual

to make a suicide attempt. The data is incom-

plete at this time and future research should

continue to evaluate these ideas.

In addition to documenting a signifi-

cant difference between NSSI adolescents

who had and had not attempted suicide

on our variables of interest; we examined

specific content differences within the

reasons for living reported and depressive

symptoms.

Some

consistent

findings

emerged across the two domains, indicating

robust results. The self-injuring adolescents

who attempted suicide reported signifi-

cantly higher levels of anhedonia on the

RADS and less of a future orientation on

the RFL-A than the self-injuring adoles-

cents

who

did

not

attempt

suicide.

Together, these complementary findings

suggest that feelings of apathy, lack of

motivation, and an inability to identify

something to work towards in the future

warrant increased attention by clinicians

to evaluate possible suicide risk. Self-

injuring adolescents who have a more nega-

tive outlook on life or who struggle to

identify future positive goals appear to be

at greater risk for attempting suicide. The

results are comparable to findings that feel-

ings of hopelessness significantly elevates

risk for suicide in adolescents (e.g., Maris,

1991; Maris, Berman, Maltsberger et al.,

1992; Mazza & Reynolds, 1998; Rich, Kirk-

patrick-Smith, Bonner et al., 1992), some-

times being a stronger predictor of suicide

attempts than global scores of depression.

Our findings indicate that a similar process

of risk may occur for self-injuring adoles-

cents. Lack of a future orientation and high

levels of anhedonia may contribute to a

pessimistic outlook on life, reducing motiv-

ation to struggle through difficult times,

and increasing the desire to attempt suicide.

Therefore, in order to prevent suicide

attempts within this at-risk group it

becomes important clinically to help self-

injuring adolescents develop long-term

goals, identify positive expectations about

the future, and broaden their perspective

beyond their immediate distress (see Berk,

Henriques, Warman et al., 2004; Brown,

Have, Henriques et al., 2005).

We also found that self-injuring adoles-

cents who did not attempt suicide reported

greater self-acceptance on the RFL-A, and less

negative self-evaluation on the RADS; how-

ever, their self-acceptance=self-evaluation

Risk For Suicide

78

VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1 2007

was still significantly lower than adolescents

who never engaged in NSSI. The fact that

the NSSI þ SA group reported more negative

self-evaluation=self-acceptance is consistent

with research documenting an association

between low self-esteem and suicide risk

(e.g., Overholser, Adams, Lehnert et al.,

1995) in non-self-injuring adolescents. What

our results suggest is that the NSSI only

adolescents were better able to identify some

positive attributes that likely contribute to a

more optimistic outlook and stronger sense

of self, reducing a wish to die. Therefore,

strengthening an adolescent’s self-acceptance

and challenging distorted self-evaluative judg-

ments may enhance feelings of self-worth as

well as increase self-efficacy to cope with

negative life events, adding to resilience

against suicide. Additional studies are needed

to further understand how an adolescent’s

self-perception may impact risk for NSSI

along with risk for suicidal behavior within

this at-risk population.

Two other differences were found

between our groups. The NSSI only group

reported higher levels of family alliance and

suicide

related

concerns

than

the

NSSI þ SA group. The result that adoles-

cents who engaged in only NSSI reported

higher family alliance than those who

attempted suicide suggests that NSSI only

adolescents were still able to identify and

draw upon external support from others

in their life to avoid attempting suicide.

This finding implies that fostering close,

supportive

relationships

is

potentially

important to reducing suicide risk. This

idea is further supported by the lack of sig-

nificant differences between our groups on

peer acceptance and support. Acceptance

by one’s peers and support from friends

is often identified as a protective factor

against suicide (Kandel, Raveis, & Davies,

1991; King, Segal, Naylor et al., 1993;

Rudd, 1990). However, within our sample,

peer support did not differ between the

groups. Therefore, having support and

feeling as though one can turn to a family

member for help may be a more important

protective factor against suicide attempts

within a self-injuring population of adoles-

cents than turning to one’s peers. Focusing

upon family interventions that enhance

supportive, positive connections between

adolescents and a family member may be

particularly warranted.

With regard to suicide related con-

cerns, the NSSI only group reported a

greater number of concerns indicating

greater aversion to suicide. Items from this

subscale

represent

fears

of

suicidal

thoughts, fears of pain associated with a

suicide attempt, and fears of suicidal beha-

vior. Within our sample, adolescents who

engaged in NSSI but did not make a suicide

attempt scored as being more fearful of sui-

cide. This may have implications for under-

standing suicide risk within a NSSI group

using Joiner’s (2005) model. Joiner pro-

poses that individuals who attempt suicide

are able to do so, in part, because they have

habituated to pain or fears associated with

self-destructive acts through exposure to

acts of self-harm. Our finding is consistent

with this perspective because those who

attempted suicide reported significantly

fewer fears of suicide. However, those

who attempted suicide did not differ in

the mean frequency of their NSSI acts

from those who did not attempt suicide,

which

conflicts

with

Joiner’s

thesis.

Additional research is needed to evaluate

the application of Joiner’s model within a

self-injuring sample. What can be taken

from our findings is that adolescents who

demonstrate behaviorally, or verbally, little

fear about severely injuring themselves are

probably at a high level of suicide risk.

A few limitations must be considered

when interpreting our findings. All of the

data were collected through self-report

measures and are retrospective in nature;

although a majority of participants had

self-injured within the past year. The fact

that some participants who reported self-

harm were not currently engaging in NSSI

J. Muehelenkamp and P. Gutierrez

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

79

means that some scores on the dependent

measures did not reflect the adolescents’

psychological state in close proximity to

the self-harm. However, this allows for a

conservative

estimate

of

differences,

assuming that psychological distress would

be lower during time periods in which the

adolescent is not actively engaging in self-

injury. Another limitation is that data were

drawn from a non-clinical sample of high

school students who endorsed symptoms

of depression and suicidal ideation well

within the normative range. On the other

hand, much of the research on NSSI has

focused upon clinical samples of adoles-

cents, so our sample provides valuable data

about the nature of self-injury in the

broader community of adolescents. The

self-report nature of the measures reduced

the follow-up data that could be collected

regarding self-injury, which prevented clari-

fication of ambiguous responses to the

Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire (Gutier-

rez, Osman, Barries et al., 2001). Data

regarding the function of SIB, other affect-

ive experiences (e.g., hostility), and family

functioning were not assessed but may also

shed light on potential differences between

self-injurers who do and do not attempt

suicide. Additionally, we did not collect

information on whether or not the parti-

cipants were currently, or had previously,

received therapeutic services, which could

affect scores on the measures we used.

Since our sample drew from a non-clinical

population the generalizability of our find-

ings to inpatient populations or to adoles-

cents with clinically significant psychiatric

disorders may be limited.

In summary, our results provide data

documenting clinically relevant differences

within traditional psychosocial correlates

of suicide risk between self-injuring adoles-

cents who attempt suicide and those who

do not. Additionally, our findings that

self-injuring

adolescents

who

endorse

symptoms of anhedonia, pessimistic future

perspectives, low self-acceptance, poor

family connections, and few fears about

self-harm appear to be at the greatest risk

for suicide add to the field’s understanding

of this at-risk population. Our results also

contribute evidence for arguments that a

symptom based approach should be used

when trying to comprehensively under-

stand NSSI and the associated risk for sui-

cide within this subgroup of adolescents.

Global diagnoses such as depression may

not capture the unique elements contribu-

ting to the destructive behavior(s). Overall,

the clinical implications of our findings are

that careful monitoring of suicidal ideation

and interventions targeting specific symp-

tom clusters underlying the NSSI may help

to prevent a potential suicide attempt or

death. Strengthening reasons for living,

improving family connections, and building

a positive future orientation would most

likely build strong internal resilience against

suicide for these vulnerable adolescents.

AUTHOR NOTE

Jennifer J. Muehlenkamp, University of

North Dakota

Peter M. Gutierrez, Northern Illinois

University

Correspondence regarding this article

should be addressed to Jennifer J. Muehlen-

kamp, Ph.D., Department of Psychology,

319 Harvard St Stop 8380, University of North

Dakota, Grand Forks, ND 58202. E-mail:

jennifer.muehlenkamp@und.nodak.edu

REFERENCES

Beautrais, A. L., Joyce, P. R., & Mulder, R. T. (1996).

Risk factors for serious suicide attempts among

youths aged 13 through 24 years. Journal of the

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

,

35

, 1174–1182.

Berk, M. S., Henriques, G. R., Warman, D. M., et al.

(2004). A cognitive therapy intervention for sui-

cide attempters: An overview of the treatment

Risk For Suicide

80

VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1 2007

and case examples. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice,

11

, 265–277.

Brent, D. A., Johnson, B., Bartle, S., et al. (1993a).

Personality disorder, tendency to impulsive viol-

ence, and suicidal behavior in adolescents. Journal

of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psy-

chiatry

, 32, 69–75.

Brent, D. A., Perper, J., Moritz, G., et al. (1993b).

Suicide in adolescents with no apparent psycho-

pathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child

and Adolescent Psychiatry

, 32, 494–500.

Brown, G. K., Have, T. T., Henriques, G. R., et al.

(2005). Cognitive therapy for the prevention of

suicide attempts: A randomized controlled trial.

JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association

,

294

, 563–570.

Darche, M. A. (1990). Psychological factors differen-

tiating self-mutilating and non-self-mutilating ado-

lescent inpatient females. The Psychiatric Hospital,

21

, 31–35.

De Man, A. F. & Leduc, C. P. (1995). Suicidal idea-

tion in high school students: Depression, and

other correlates. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51,

173–180.

DiClemente, R. J., Ponton, L. E., & Hartley, D.

(1991). Prevalence and correlates of cutting beha-

vior: Risk for HIV transmission. Journal of the

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry

,

30

, 735–739.

Dulit, R. A., Fryer, M. R., Leon, A. C., et al. (1994).

Clinical correlates of self-mutilation in borderline

personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry,

151

, 1305–1311.

Garrison, C. Z., Addy, C. L., McKeown, R. E., et al.

(1993). Nonsuicidal physically self-damaging acts

in adolescents. Journal of Child & Family Studies,

2

, 339–352.

Guertin, T., Lloyd-Richardson, E., Spirito, A., et al.

(2001). Self-mutilative behavior in adolescents

who attempt suicide by overdose. Journal of the

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

,

40

, 1062–1069.

Gutierrez, P. M., Osman, A., Barrios, F. X., et al.

(2001). Development and initial validation of the

self-harm

behavior

questionnaire.

Journal

of

Personality Assessment

, 77, 475–490.

Gutierrez, P. M. Osman, A., Kopper, B. A., et al.

(2000). Why young people do not kill themselves:

The reasons for living inventory for adolescents.

Journal of Clinical Child Psychology

, 29, 177–187.

Hawton, K., Fagg, J., Simkin, S., et al. (1997). Trends

in deliberate self-harm in Oxford, 1985–1995:

Implications for clinical services and the preven-

tion of suicide. British Journal of Psychiatry, 171,

556–560.

Joiner, T. E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kandel, D. B., Raveis, V. H., & Davies, M. (1991).

Suicidal ideation in adolescence: Depression,

substance use, and other risk factors. Journal of

Youth and Adolescence

, 20, 289–309.

Kessler, R. C., Borges, G., & Walters, E. E. (1999).

Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide

attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey.

Archives of General Psychiatry

, 56, 617–626.

King, C. A., Hovey, J. D., Brand, E., et al. (1997).

Prediction of positive outcomes for adolescent

psychiatric inpatients. Journal of the American

Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

, 36,

1434–1442.

King, C. A., Segal, H., Naylor, M., et al. (1993). Fam-

ily functioning and suicidal behavior in adolescent

inpatients with mood disorders. Journal of the

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

,

32

, 1198–1206.

Kovacs, M., Goldston, D., & Gatsonis, C. (1993).

Suicidal behaviors and childhood-onset depressive

disorders: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of

the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psy-

chiatry

, 32, 8–20.

Kumar, G., Pope, D., & Steer, R. A. (2004). Ado-

lescent psychiatric inpatients’ self-reported reasons

for cutting themselves. The Journal of Nervous and

Mental Disease

, 192, 830–836.

Mann, J. J., Waternaux, C., Haas, G. L., et al. (1999).

Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in

psychiatric patients. The American Journal of Psy-

chiatry

, 156, 181–189.

Maris, R. W. (1991). Special issue: Assessment and

prediction of suicide: Introduction. Suicide and

Life-Threatening Behavior

, 21, 1–17.

Maris, R. W., Berman, A. L., Maltsberger, J. T. H,

et al. (Eds.). (1992). Assessment and prediction of sui-

cide

. New York: Guilford.

Maris, R. W., Berman, A. L., & Silverman, M. M.

(2000). Comprehensive textbook of suicidology. New

York: Guilford.

Mazza, J. J. & Reynolds, W. M. (1998). A longitudinal

investigation of depression, hopelessness, social

support, and major and minor life events and their

relation to suicidal ideation in adolescents. Suicide

and Life-Threatening Behavior

, 28, 359–374.

Muehlenkamp, J. J. & Gutierrez, P. M. (2004). An

investigation of differences between self-injurious

J. Muehelenkamp and P. Gutierrez

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

81

behavior and suicide attempts in a sample of

adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior,

34

, 12–23.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., Jacobson, C. M., et al. (2005).

Borderline symptoms and adolescent parasuicide.

Poster presented at the annual American Associ-

ation of Suicidology conference, Broomfield, CO.

Nock, M. K. & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional

approach to the assessment of self-mutilative

behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,

72

, 885–890.

O’Carroll, P.W., Berman, A.L., Marris, R.W., et al.

(1996). Beyond the Tower of Babel: A nomencla-

ture for suicidology. Suicide and Life-Threatening

Behavior

, 26, 237–52.

Olfson, M., Gameroff, M. J., Marcus, S. C., et al.

(2005). National trends in hospitalization of youth

with intentional self-inflicted injuries. The American

Journal of Psychiatry

, 162, 1328–1335.

Osman, A., Downs, W. R., Kopper, B. A., et al. (1998).

The reasons for living inventory for adolescents

(RFL-A): Development and psychometric proper-

ties. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54, 1063–1078.

Overholser, J. C., Adams, D. M., Lehnert, K. L., et al.

(1995). Self-esteem deficits and suicidal tendencies

among adolescents. Journal of the American Academy

of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

, 34, 919–928.

Range, L. M. & Knott, E. C. (1997). Twenty suicide

assessment instruments: Evaluation and recom-

mendations. Death Studies, 21, 25–58.

Reynolds, W. M. (1987). Reynolds adolescent depression

scale: Professional manual

. Lutz, FL: Psychological

Assessment Resources, Inc.

Reynolds, W. M. (1988). SIQ professional manual. Odessa,

FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Reynolds, W. M. (2002). Reynolds adolescent depression

scale–2nd edition: Professional manual

. Lutz, FL:

Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Rich, A. R., Kirkpatrick-Smith, J., Bonner, R. L., et al.

(1992). Gender differences in the psychosocial

correlates of suicidal ideation among adolescents.

Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior

, 22, 364–373.

Ross, S. & Heath, N. (2002). A study of the fre-

quency of self-mutilation in a community sample

of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31,

67–77.

Ross, S. & Heath, N. (2003). Two models of ado-

lescent self-mutilation. Suicide and Life-Threatening

Behavior

, 33, 277–287.

Rudd, M. D. (1990). An integrative model of suicidal

ideation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 20,

16–31.

Stanley, B., Gameroff, M. J., Michalsen, V., et al.

(2001). Are suicide attempters who self-mutilate

a unique population? The American Journal of Psy-

chiatry

, 158, 427–432.

Stanley, B., Winchel, R., Molcho, A., et al. (1992).

Suicide and the self-harm continuum: Phenom-

enological and biological evidence. International

Review of Psychiatry

, 4, 149–155.

Walsh, B.W. (2005). Treating self-injury: A practical guide.

New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Zlotnick, C., Donaldson, D., Spirito, A., et al. (1997).

Affect regulation and suicide attempts in ado-

lescent inpatients. Journal of the American Academy

of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

, 36, 793–798.

Risk For Suicide

82

VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1 2007

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Variations in Risk and Treatment Factors Among Adolescents Engaging in Different Types of Deliberate

3 T Proton MRS Investigation of Glutamate and Glutamine in Adolescents at High Genetic Risk for Schi

Associations among adolescent risk behaviours Do wstepu wazne

Karpińska Krakowiak, Małgorzata Conceptualising and Measuring Consumer Engagement in Social Media I

Sexual behavior and the non construction of sexual identity Implications for the analysis of men who

Psychiatric Impairment Among Adolescents Engaging in Different Types of Deliberate Self Harm

Brief Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Suicidal Behaviour and NSSI

The Epidemiology and Phenomenology of NSSI Behaviour Among Adolescents A Critical Review of the Lit

Single nucleotide polymorphism D1853N of the ATM gene may alter the risk for breast cancer

Physiological Arousal, Distress Tolerance, and Social Problem Solving Deficits Among Adolescent Self

Assessment of balance and risk for falls in a sample of community dwelling adults aged 65 and older

Ionic liquids as solvents for polymerization processes Progress and challenges Progress in Polymer

An Engagement in Seattle ?bbie Macomber

Doctors engaged in

making tea in place experiences of women engaged in a japanese tea ceremony

Robert P Smith, Peter Zheutlin Riches Among the Ruins, Adventures in the Dark Corners of the Global

Willingness to Engage in Unethical Pro Organizational Behavior

The Code of Honor or Rules for the Government of Principals and Seconds in Duelling by John Lyde Wil

więcej podobnych podstron