Rigoletto Page 1

Rigoletto

Italian opera in three acts

Music

by

Giuseppe Verdi

Premiere at the Gran Teatro La Fenice, Venice,

March 1851

Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, based on Victor

Hugo’s play Le Roi s’amuse,

(The King Has a Good Time)

Adapted from the

Opera Journeys Lecture Series

by

Burton D. Fisher

Story Synopsis

Page 2

Principal Characters in the Opera

Page 2

Story Narrative with Music Highlights

Page 3

Verdi…..and

Rigoletto

Page 15

Opera Journeys™ Mini Guide Series

Published © Copywritten by

Opera Journeys

www.operajourneys.com

Rigoletto Page 2

Story Synopsis

Rigoletto is a grim and brutal melodrama.

Rigoletto, deformed and hunchbacked, is a jester in the

16

th

century Court of the Duke of Mantua. Rigoletto

mocks and outrageously insults the husbands and fathers

of his master’s amorous conquests, eventually provoking

the noble Monterone, whose daughter had been raped

by the Duke, to pronounce a father’s curse on him.

Rigoletto himself has a young daughter, Gilda,

whom he overprotects by secluding her from the outside

world. Unknown to Rigoletto, Gilda falls in love with

the Duke after she meets him when he is disguised as a

poor student. The courtiers of the Mantuan court, seeking

revenge against the despised court jester, believe Gilda

to be Rigoletto’s mistress. They conspire to abduct her

and deliver their prize to the libertine Duke.

When Rigoletto finds Gilda in the Duke’s palace,

he vows revenge and punishment against his master for

the rape of his beloved daughter; he hires the

professional assassin, Sparafucile, to murder the Duke.

Sparafucile’s sister and accomplice, Maddalena, becomes

infatuated with the Duke and persuades her brother to

fulfill his murder contract by killing the next person

who enters their inn.

Instead of the Duke, Gilda sacrifices her life for

her new-found love and becomes the victim of

Sparafucile’s sword. In a tragic irony of failed revenge,

the corpse delivered to Rigoletto is his own beloved

daughter, Gilda.

Principal Characters in the Opera

Rigoletto, a court jester

Baritone

Gilda, Rigoletto’s daughter

Soprano

Duke of Mantua

Tenor

Giovanna, Gilda’s nurse

Soprano

Sparafucile, a hired assassin

Bass

Maddalena, Sparafucile’s sister

Soprano

Monterone, a nobleman

Bass

Count Ceprano, Countess Ceprano, Borsa,

Marullo, and courtiers

Time and Place: 16th century,

The city of Mantua, Italy

Rigoletto Page 3

Story Narrative and Music Highlights

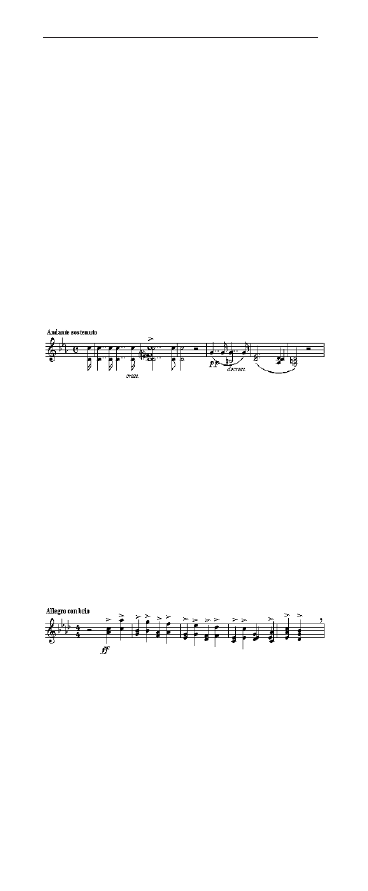

Prelude:

A short prelude, somber, ominous, and menacing,

musically presages the forthcoming tragedy. In the very

first scene, Rigoletto will have mocked the aged

nobleman, Monterone, for damning the Duke as the

rapist of his daughter. In return for his insolence,

Monterone pronounces a father’s curse on Rigoletto,

the fear of the curse echoing throughout the drama and

haunting Rigoletto.

The musical motive of the prelude underscores

Rigoletto’s fear and horror when he recalls Monterone’s

curse: Quel vecchio maledivami!, “That old man cursed

me!”

ACT 1 - Scene 1: A Salon in the Ducal Palace

An elegant assembly of courtiers, ladies, and pages,

are gathered in a magnificent salon in the Duke’s palace.

The festive air is accented by lighthearted, elegant dance

music played by an off-stage band; the trivial gaiety is a

profound contrast to the grotesque reality of the scene

which is pervaded by banality, evil, and depravity. The

ambience suggests a Roman orgy, or the circus-like

decadence of a Felliniesque La dolce vita.

Off-stage Dance Music:

The Duke of Mantua strolls through the crowd

while in conversation with Borsa, one of his courtiers,

enthusiastically telling him about a beautiful young girl

he saw in church and has been pursuing incognito for

the past three months. He relates how he followed her

to her small home located in a narrow lane in a remote

part of the city, but has been confused by the appearance

of a mysterious man who visits her every evening.

The Duke’s attention wanders to a group of

women who cross before him. Among them is the

Countess Ceprano, whom he immediately praises for her

Rigoletto Page 4

beauty, heedless to Borsa’s counsel that her husband, the

Count Ceprano, should not overhear his amorous overtures.

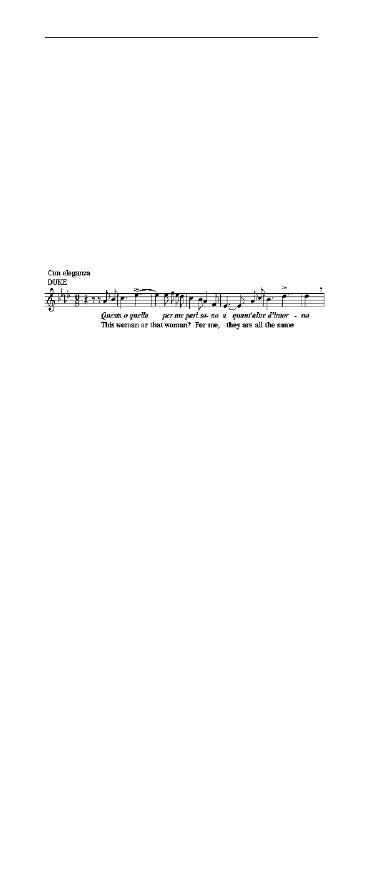

The Duke responds to Borsa’s caution by expounding

his libertine, chauvinist philosophy about women: Questa o

quella per me pari sono, “This woman or that woman? For

me, they are all the same.” The Duke’s cynicism expresses

the view that one pretty woman is the same as any other;

today this one pleases him, tomorrow another. He speaks of

fidelity as “a tyrant to shun like a bad disease,” scornfully

affirming his freedom to love according to his whims, and

flamboyantly ridiculing cuckolded and jealous husbands.

Questa o quella per me pari sono

Indifferent to Count Ceprano’s rage, the Duke

fervently continues his flirtations with the Countess,

kissing her hand and telling her he is “drunk with love

for her.” After the Duke wanders off with the Countess

to an adjoining room, Rigoletto, the hunchbacked court

jester, arrives and immediately taunts and provokes the

furious Count Ceprano, adding fuel to his outrage by

implying that the Duke is enjoying the willing favors of

the Countess.

After Rigoletto goes off to follow the Duke and

the Countess Ceprano, to the merriment of the other

courtiers, Marullo breaks the news that he has discovered

that the ugly old jester has a mistress, a woman whom

he visits every night. The courtiers react in disbelief,

suggesting to Marullo that pandering by this sexually

repulsive hunchback must surely be an hilarious joke.

The Duke returns to the festivities and confides

to Rigoletto that the Countess Ceprano would be a

wonderful conquest, however, her husband is an

impediment and he would like to get rid of him. The

malevolent Rigoletto adds fuel to the fire and casually

suggests prison, exile, or even execution for the Count,

saying with nonchalance: “so what, what does it matter?”

Ceprano overhears their nefarious conversation, fumes

with revenge, and reacts violently, barely restraining

himself from drawing his sword against Rigoletto.

The Duke berates Rigoletto, suggesting that this

time he has gone too far; nevertheless, the jester feels

secure in his unlimited trust in the Duke’s protection.

All the courtiers have at one time or another been victims of

the malevolent derision of the contemptuous court jester.

Rigoletto Page 5

Rigoletto’s jibes at Ceprano have pushed the envelope, and

this time, the courtiers readily agree with Ceprano that they

will meet him later that evening to plot revenge on the

hunchback. Their revenge on Rigoletto will be the ultimate

irony to Rigoletto’s scorn: they will follow Rigoletto’s own

suggestion to the Duke and will abduct his “mistress.”

The stern voice of Count Monterone is heard

outside, demanding to be admitted. Monterone confronts

the Duke and denounces the profligate libertine for

seducing his daughter. Rigoletto mocks and ridicules the

old man, but Monterone continues his protest and

declares that dead or alive, he will haunt the Duke for

the rest of his days.

The Duke’s response is to order that Monterone

be arrested. The relentless Rigoletto continues to insult

the outraged father, ultimately inflaming Monterone

to curse the Duke, as well as to damn the court jester.

Monterone, the austere voice of divine justice, curses

the evil Rigoletto: “As for you, serpent, you can laugh

at a father’s anguish; a father’s curse be on your head.”

It is Monterone’s second curse, directed solely at

Rigoletto, that makes the jester freeze with horror.

The courtiers resume their festivities as

Monterone is led off by guards. Rigoletto trembles with

fright and terror, and recoils in fear; Monterone’s curse

is firmly implanted in his soul.

Scene 2: A deserted and dark street

Rigoletto, almost totally disguised and wrapped in a

cloak, walks toward his home, paranoid in his fear of

Monterone’s curse: Qual vecchio maladivami! “That old

man cursed me!”

He is followed by an ominous figure who introduces

himself as Sparafucile, a professional assassin-for-hire.

Sparafucile explains the terms of his profession with

the self-conscious rectitude of an honest tradesman,

offering Rigoletto his services at reasonable charges

should he ever need to get rid of any rival for the young

woman he keeps under lock and key.

Sparafucile’s music:

Rigoletto Page 6

Sparafucile explains the details of his trade to

Rigoletto; he and his sister, a gypsy temptress, lure their

victims to their Inn and then dispose of them. Rigoletto

indicates no present need for his services, dismisses him,

but indeed makes a point of learning how he can be found in

the future.

Alone, Rigoletto is again haunted by returning

thoughts of Monterone’s curse. He then reflects on his

chance meeting with the assassin for hire, comparing

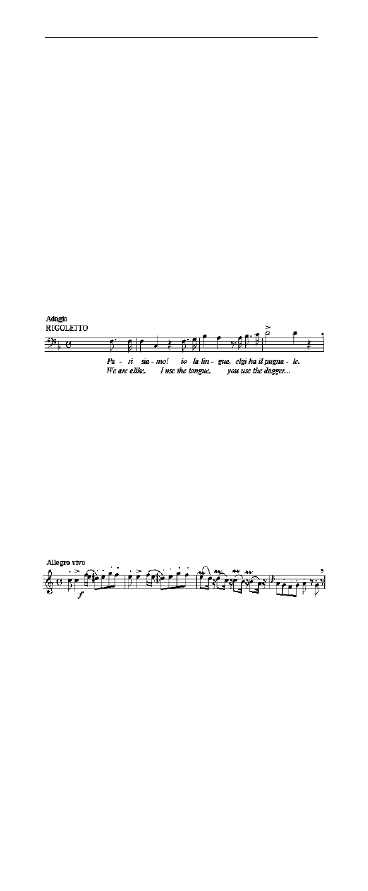

himself as his equal: Pari siamo! Io la lingua, egli ha il

pugnato…, “We are equals, I use the tongue, you use

the dagger.” Both men indeed share evil: both men are

paid to wound their victims with their lethal weapons;

one with his tongue, the other with his sword.

Pari siamo

In this soliloquy, Pari siamo…, Rigoletto curses

fate and nature for bringing him into the world ugly and

deformed. He further blames the hated courtiers as the

cause of his own wickedness and evil. But again,

Monterone’s curse returns to haunt his thoughts, his

disturbed mood shaken off only when the echo of flute

music returns his thoughts to his beloved daughter, Gilda.

Gilda welcomes Rigoletto:

Rigoletto enters the courtyard of his house and

Gilda rushes joyfully to embrace her father.

Gilda senses her father’s sadness. Rigoletto is

uneasy and agitated. Bordering on fear and panic, he

immediately asks Gilda if she has been out of the house,

fearing that she would fall victim to one of the courtiers

or the evils of the city.

Gilda tries to change the mood; she expresses her

deep love for her father, and asks to know more about

him and her family. Why does her father never tell her

his name? She asks about her mother, and Rigoletto

replies: “Do not speak of misery, of that terrible loss…”

Rigoletto Page 7

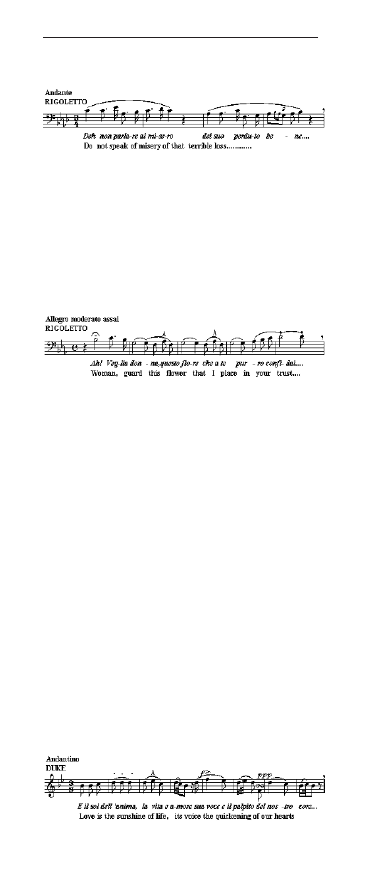

Rigoletto and Gilda: Deh non parlare al misero

Rigoletto passionately explains to Gilda that she is

his only treasure left in this world, but suddenly, again

preoccupied with fears, he turns to the nurse Giovanna

and reminds her to carefully protect his beloved child;

Gilda is to remain within the walls of their home and

never to venture into the town except on that one day

when the nurse is to accompany her to church.

Ah veglia donna

Noises are heard from the street and Rigoletto

rushes out to investigate. After he leaves, the Duke

slips into the courtyard, sees Giovanna, and throws her

a purse to buy her silence. The Duke remains hidden as

Rigoletto returns.

Unable to allay his fears and suspicions, Rigoletto

questions Gilda if anyone had ever followed her from

church. Gilda responds negatively, assuring her father

that he need not fear for her safety; her mother - an

angel in heaven - is always protecting her.

Rigoletto bids a touching farewell to Gilda, his

parting words mia figlia, “my daughter,” are overheard

by the hiding Duke, and provides him with a surprising

revelation.

After Rigoletto departs, Gilda confesses to

Giovanna her remorse at not having confided to her

father that she has frequently been followed from church

by a handsome young man. As she reveals her love for

this mysterious suitor - t’amo, “I love you” - the Duke

steps out from hiding, embraces Gilda, and then explodes

into a declaration of his love for her.

È il sol dell’anima

Rigoletto Page 8

Gilda tries feebly to resist the Duke’s ardor but

surrenders; both join in an ecstatic love duet. In response to

Gilda’s curiosity, the Duke tells her that his name is Gualtier

Maldé, a poor and struggling student.

The voices of Borsa and Ceprano – preparing the

courtier’s intrigue to abduct Rigoletto’s mistress - cause

Giovanna to warn the lovers. Gilda is also fearful that

her father may be returning and insists that her new-

found lover depart. Gilda and Gualtier Maldé – the

Duke – sing a passionate farewell.

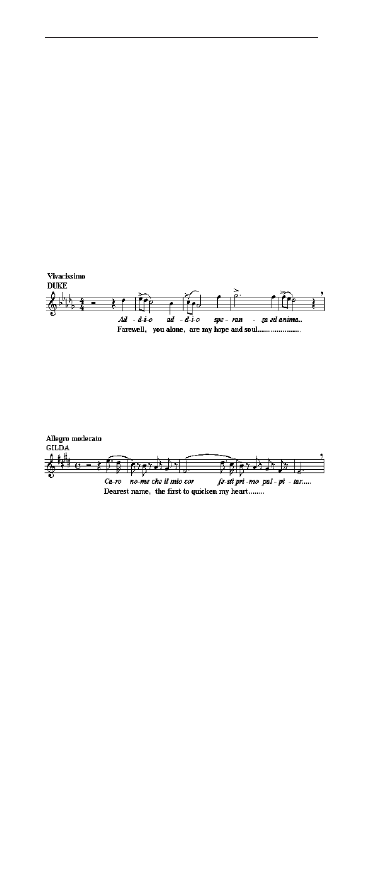

Duke and Gilda: Addio, addio, speranza ed anima.

Alone, Gilda sighs joyfully about the poor student

she has fallen in love with, Gualtier Maldé: Caro nome,

“Dearest name, the first to quicken my heart.”

Caro nome

Meanwhile, the courtiers – disguised and masked

- have assembled in the dark night. They notice Gilda

from hiding, and comment on the beauty of “Rigoletto’s

mistress.”

Rigoletto unexpectedly returns, runs into the

courtiers, and they calm his fears and suspicions by

telling him that their mission is to abduct Ceprano’s

wife for the Duke. Rigoletto delights perversely at the

intrigue, points them to Ceprano’s house, and offers

them his help.

The courtiers insist that Rigoletto must also wear

a disguising mask. Thoroughly confused and blinded by

the mask, Rigoletto unwittingly holds a ladder for the

courtiers against what he believes to be the wall of

Ceprano’s house, but in reality, he is holding the ladder

against his own house.

The abductors enter Rigoletto’s house and seize,

gag, and carry away Gilda. A moment later, Gilda’s cries

for help are heard, followed by shouts of “victory”

from the escaping courtiers. But Rigoletto, his ears

covered by the mask, hears nothing. Now thoroughly

Rigoletto Page 9

confused and bewildered, he tears off the mask and discovers

that he is in his own courtyard. On the ground, he notices

Gilda’s scarf, and then notices that the door of his house is

wide open. Frantic with fear, he rushes into his house and

finds that Gilda has disappeared.

He comes out of the house dragging the terrified

Giovanna, and staggers in shock on the disaster he has

helped bring upon himself. In agony, he remembers

Monterone’s curse and bursts out: Ah! La maledizione!

“Ah, the curse!” And then, Rigoletto faints.

ACT II: A drawing room in the Duke’s Palace

The Duke is agitated and distraught. He had

returned to Rigoletto’s house; instead of finding Gilda,

he found the house deserted. Certain that Gilda has

been abducted, he is torn between rage that anyone

should have dared to cross him, and pity for the girl

whom he now claims has awakened for the first time,

genuine feelings of affection. The Duke reveals a

heretofore unrevealed sense of sincerity and compassion.

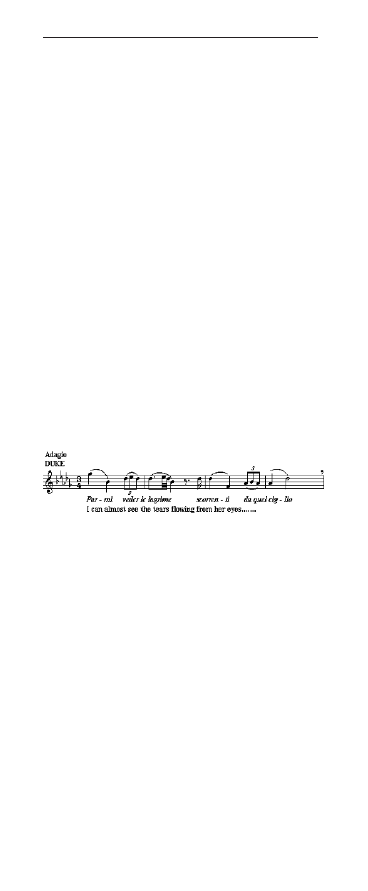

Parmi veder le lagrime

Marullo, Ceprano, Borsa, and other courtiers enter

the drawing room and gleefully – and heartlessly - narrate

their adventures of the previous night, cynically

describing Rigoletto’s unwitting collaboration as they

abducted the girl they believed to be Rigoletto’s mistress.

The Duke realizes that they are referring to none other

than Gilda. He is further delighted when he learns that

they have brought her to the palace. He dashes off to

the conquest, intending to console his new love.

The grief-stricken Rigoletto enters the salon, self-

controlled and pretending nonchalance; his cynicism

conceals his distress and anxiety. The courtiers greet

him with ironical good humor, but in a pathetic

spectacle, Rigoletto searches for clues as to the

whereabouts of his daughter, even snatching up a

handkerchief from the table in the hope that it may

belong to Gilda.

Certain that Gilda is with the Duke and in the

palace, he tries to enter the Duke’s quarters, but the

Rigoletto Page 10

courtiers bar his way, telling him that the Duke is asleep and

cannot be disturbed. A page enters to announce that the

Duchess wishes to speak to her husband. The courtiers

respond by pretending that the Duke has gone hunting, but

Rigoletto pierces through the veil of their charade and

intuitively senses the truth: he concludes that Gilda is

definitely in the palace.

Behind a laughing exterior, Rigoletto continues

his search for Gilda. The courtiers mock him, telling

him to look for his “mistress” somewhere else. In a

fury, Rigoletto astonishes them and reveals the truth,

crying out: Io vo’ mia figlia, “I want my daughter.”

Alternating between threats and pleas - and even

force - to enter the Duke’s quarters, in a state of fury

and frustration, Rigoletto violently denounces the

courtiers, simultaneously lashing out at their cruelty

with pleas for mercy: Cortigiani vil razza,dannata

“Courtiers, you cursed race.”

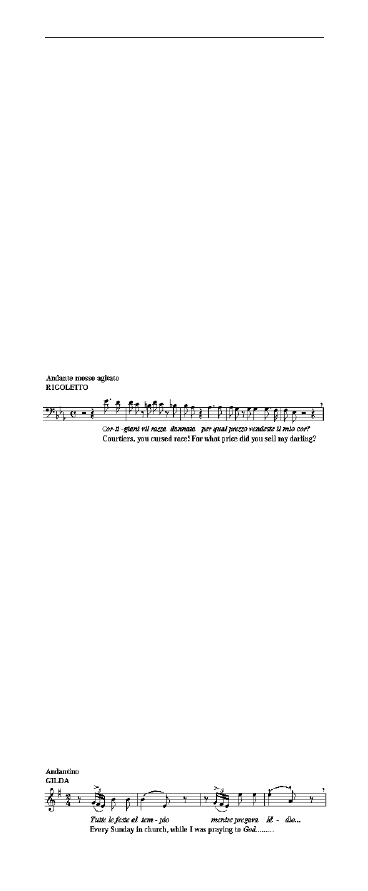

Cortigiani vil razza, dannata

Suddenly, the freshly ravished Gilda rushes out

from the Duke’s apartments and throws herself into her

father’s arms. Rigoletto’s first reaction is one of relief:

in his mind she is safe. Perhaps it was all a joke.

Gilda sees her father for the first time in his jester’s

costume, and each, in a blinding moment of revelation,

realizes their shame. Gilda’s tears convince Rigoletto

that the matter is more serious as she tells her father:

“Let me blush before you alone.”

Gilda admits her guilt and confesses everything

to Rigoletto. She relates how a young student she had

seen in church followed her to her home, and how she

later fell in love with him. When she was abducted and

brought to the palace, she was surprised to find that the

young man was none other than the Duke of Mantua:

Gilda had innocently fallen in love and abandoned herself

to her new love consensually.

Tutte le feste al tempio

Rigoletto Page 11

During this poignant and delicate moment, Rigoletto

tenderly attempts to comfort his daughter, but he is confused,

and even in denial. Monterone passes by under guard on

his way to prison. He pauses and directs his chagrined anger

before the Duke’s portrait: “Since I have cursed you in vain,

and no thunderbolt or sword has struck you down, you live

happily still, Duke.”

As Monterone is led away, Rigoletto calls to him,

telling him that he is mistaken: Rigoletto assures him

that they will both be avenged. At this turning point of

the drama, Rigoletto is now transformed into a man of

savage fury. He swears a frightful vengeance on the

Duke while Gilda tries in vain to beg forgiveness for the

man she deeply loves.

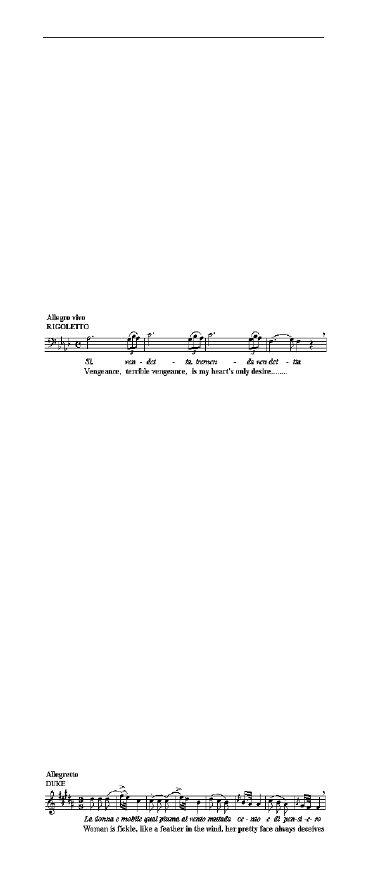

Duet: Si vendetta tremenda vendetta.

ACT III: Sparafucile’s Inn on the deserted banks of the

Mincio River.

Sparafucile sits inside the inn, polishing his belt.

Outside, Rigoletto and Gilda watch through a small

opening in the wall.

Still full of romantic protestations, Gilda persists

that she passionately loves the Duke, and truly believes

he will return her love. But Rigoletto believes he can

cure her affectation for this licentious libertine by

bringing her to Sparafucile’s Inn; he well knows that

what she will witness inside will prove to her that her

lover is worthless and capricious.

The Duke, disguised as a cavalier, is seen inside

the Inn ordering wine and a room for the night. Gilda

now hears her lover in his true character. The libertine

Duke once again advances his cynical, chauvinist

philosophy about the fickleness of woman: La donna è

mobile, “Woman is fickle.”

La donna é mobile

Rigoletto Page 12

Sparafucile’s sister, Maddalena, the gypsy

enchantress, had lured the Duke to the inn and now

joins him. Gilda and Rigoletto remain outside, watching

the Duke flirt with Maddalena inside the tavern.

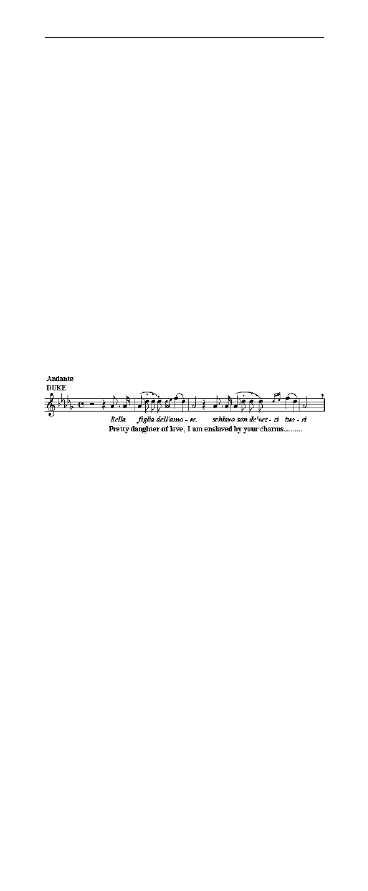

The famous Act III Quartet begins with Bella

figlia dell’amore, “Pretty daughter of love.” Each

character’s individual passions stands out in high relief:

outside the inn, Rigoletto seeks revenge while Gilda is

forgiving; inside the inn, Maddalena half-heartedly repels

the Duke’s advances as the Duke pulsates with amorous

passion, prepared to offer her anything, even marriage,

to succeed in his amorous conquest.

Concealed in the darkness outside, Gilda witnesses

the amorous interplay between the Duke and Maddalena,

becoming heartbroken and grim as she witnesses how

lightly they speak of love.

Quartet: Bella figlia dell’amore

Rigoletto persuades the disillusioned and

heartbroken Gilda to return home, dress in male attire,

and set out for Verona where he will meet her the next

day. After she leaves, Rigoletto summons Sparafucile

and hands over half the assassin’s fee for the murder of

the Duke, promising to pay the remainder when the

body is delivered to him in a sack at midnight. Sparafucile

offers to throw the body in the river himself, but

Rigoletto, wanting personal satisfaction, insists that he

will personally return at midnight for the body.

Sparafucile casually asks Rigoletto the victim’s

name, and Rigoletto antagonistically replies: Voui saper

anche il mio? Egli è Delitto, Punizion son io, “Do you

want to know my name as well? He is crime, and mine

is punishment.”

Meanwhile, inside the inn, the flirtations between

Maddalena and the Duke grow more intimate. A storm

has gathered outside, which forces the Duke to stay the

night at the inn. Gilda has returned and overhears

Maddalena announce to Sparafucile that she has been

seduced by the Duke’s charms and has fallen in love

with him. Maddalena attempts to dissuade her brother

from murdering her new-found love; nevertheless,

Sparafucile fails to understand his sister ’s sudden

Rigoletto Page 13

sentiment when the real stake is their fee of twenty crowns.

Maddalena suggests to her brother that he kill the

hunchback instead of the man she now endearingly refers

to as her “Apollo.” Citing his honor, Sparafucile refuses

to betray his employer; one does not betray and murder

his own client. Sparafucile offers his sister a compromise:

if another stranger should chance to call at the Inn

before midnight, the hour of Rigoletto’s return, he will

be the murder victim. In either case, Rigoletto will still

have a corpse for his money. If no one appears,

Maddalena’s new love must die.

Gilda has overheard Maddalena and Sparafucile

argue as to which of the two shall die: Gilda’s lover, or

their client, her father Rigoletto. Gilda fears for her

lover’s life, ultimately resolving to sacrifice her own

life for the Duke. Lightning and thunder crack as the

storm increases with sudden and overwhelming fury.

Gilda summons up her courage, knocks on the door, and

calls out: “Have pity on a beggar who wants shelter for

the night.” She then enters the inn and runs into

Sparafucile’s sword. In the darkness, Gilda’s last pathetic

words are heard, “God forgive them.” After a violent

orchestral outburst, all is silent.

As midnight strikes, Rigoletto returns to the inn.

Sparafucile meets him with the sack containing the dead

victim, offers to throw the sack in the river, but Rigoletto

claims his privilege and satisfaction, wanting to savor

the triumph of his vengeance.

The gloating Rigoletto drags the sack toward the

river. In his moment of victory, he proclaims:

Ora mi guarda o mondo! Quest’è un buffone, ed

un potente è questo! Ei sta sotto i miei piedi! È desso!

Oh gioia!

“World look at me now! Here is a buffoon, and a

powerful buffoon! And standing under my foot, it is

him! Oh joy!”

Rigoletto trembles when he hears in the distance

the Duke’s voice singing La donna é mobile. In disbelief,

he cries out that it must be a dream or an illusion. If

not, who is in the sack? It is pitch dark with occasional

lightning providing the only visibility. He tears the sack

open, and a sudden flash of lightning reveals Gilda’s

face. He cannot believe his senses, but the faint voice

from the sack reveals the truth: it is indeed his beloved

Gilda.

Rigoletto Page 14

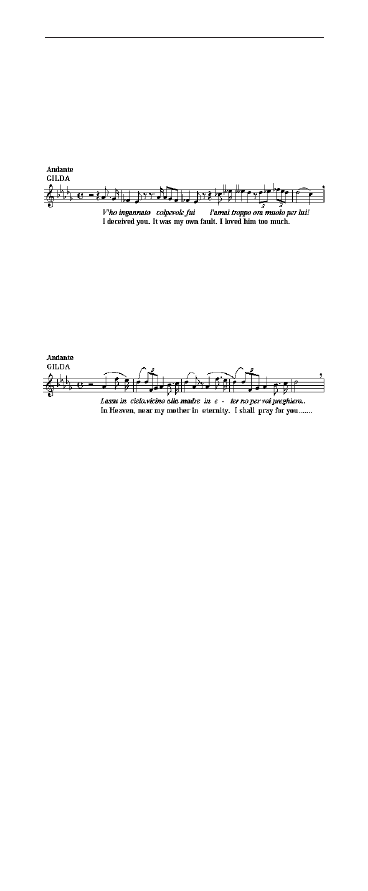

Gilda is dying from her wounds, but with her last

breath, she begs her father’s forgiveness, at the same time,

defending her actions by explaining how much she loved

the Duke.

V’ho ingannato

In a touching farewell, Lassu in ciel, “Up there in

Heaven,” Gilda tells her father how much she truly loves

him, assures him that she will be united with her mother

in Heaven, where they will both pray for him.

Lassu in ciel

Rigoletto cries out, “She is dead.” His screams

reveal the utter futility of this tragic moment of fury

and frustration, his explanation for the collapse of his

world uttered in his last words: Ah! La maledizione,

“Ah, the curse.”

Monterone’s curse has been fulfilled as disaster

overcomes the jester, defeated by his own evil.

Rigoletto Page 15

Verdi………………..……….......................…and Rigoletto

B

y the year 1851, the year of Rigoletto’s

premiere, the 38 year-old Giuseppe Verdi was

acknowledged as the most popular opera composer in

the world. He had established himself as the legitimate

heir to the great Italian opera traditions that had been

preserved during the first half of the 19

th

century by his

immediate bel canto predecessors: Rossini, Bellini and

Donizetti.

Viewing the opera landscape at mid-century,

Donizetti had died in 1848, Meyerbeer’s Le Prophète

had premiered in 1849, and Wagner’s Lohengrin had

premiered in 1850.

Verdi composed 15 operas during his first creative

period - between the years 1840 and 1851. His first two

operas, Oberto (1839), and the comedy Un Giorno di Regno

(1840), were received with indifference. His third opera,

Nabucco (1842), was a triumph that overnight transformed

Verdi into an opera icon. He followed with I Lombardi (1843);

Ernani (1844); I Due Foscari (1844); Giovanna d’Arco

(1845); Alzira (1845); Attila (1846); Macbeth (1847); I

Masnadieri (1847); Il Corsaro (1848); La Battaglia di

Legnano (1849); Luisa Miller (1849) and Stiffelio (1850).

Eventually, Verdi would write a total of 28 operas during his

illustrious career, dying in 1901 at the age of 78.

The underlying theme that was the foundation of

Verdi’s early operas concerned his patriotic mission for

the liberation of his beloved Italy, at that time, suffering

under the oppressive rule of both France and Austria.

Verdi, with his operatic pen, sounded the alarm for Italy’s

freedom. Each of those early opera stories was disguised

with allegory, metaphor, and irony, all advocating

individual liberty, freedom, and independence: the

suffering and struggling heroes and heroines in his early

operas were his beloved Italian compatriots.

For example, in Giovanna d’Arco (Joan of Arc),

the French patriot Joan confronts the oppressive English

and is eventually martyred; the heroine’s plight became

synonymous with Italy’s struggle with its own foreign

oppression. In Nabucco, the suffering Hebrews enslaved

by Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonians were

allegorically, the Italian people themselves, similarly in

bondage by foreign oppressors.

Verdi’s Italian audience easily read the underlying

message he had subtly injected between the lines of his

text and music. At Nabucco’s premiere, at the end of the

Hebrew slave chorus, Va Pensiero, the audience actually

stopped the performance with inspired nationalistic shouts

of Viva Italia. The Va pensiero chorus became the unofficial

Italian “National Anthem,” the musical symbol of Italy’s

Rigoletto Page 16

patriotic aspirations. Even the name V E R D I had a dual

meaning: homage to the great maestro in the form of Viva

Verdi, and also as an acronym for Italian unification; V E R D

I stood for Vittorio Emanuelo Re D’ Italia, a dream for the

return of King Victor Emmanuel.

A

s the 1850s unfolded, Verdi’s genius had

arrived at a turning point in terms of his artistic

evolution and maturity. He felt that his patriotic mission

for Italian independence was soon to be realized, sensing

the fulfillment of Italian liberation and unification in

the forthcoming Risorgimento, the historic

revolutionary event that established the Italian nation

as we know it today.

Satisfied that he had achieved his patriotic

objectives, Verdi decided to abandon the heroic pathos

and nationalistic themes of his early operas. He now

was seeking more profound operatic subjects: subjects

that would be bold to the extreme; subjects with greater

dramatic and psychological depth; subjects that accented

spiritual values, intimate humanity and tender emotions.

From this point forward, he would be ceaseless in his

goal to create an expressiveness and acute delineation

of the human soul that had never before been realized

on the opera stage.

The year 1851 inaugurated Verdi’s “middle

period,” the defining moment in his career, the moment

when his operas would start to contain heretofore

unknown dramatic qualities and intensities, an

exceptional lyricism, and a profound characterization

of humanity. Starting in this “middle period,” Verdi’s

art flowered into a new maturity, resulting into some of

the best loved operas of all time: Rigoletto (1851); Il

trovatore (1853); La Traviata (1853); I Vespri Siciliani (1855);

Simon Boccanegra (1857); Aroldo (1857); Un Ballo in

Maschera (1859); La Forza del Destino (1862); Don Carlos

(1867); Aïda (1871). In his final works, he succeeded in his

advance toward a greater dramatic synthesis between text

and music that would culminate in what some consider his

greatest masterpieces: Otello (1887), and Falstaff (1893).

I

n 1851, Verdi was approached by the

management of La Fenice in Venice to write an opera

to celebrate the Carnival and Lent seasons. In seeking a

story source for the opera, Verdi turned to the new

romanticism of the French dramatist, Victor Hugo.

Seven years earlier, in 1844, Verdi had a brilliant success

with his operatic treatment of Hugo’s Hernani: Verdi’s Ernani.

Rigoletto Page 17

Victor Hugo’s play, Le Roi s’amuse, “The King has a

good time,” premiered in 1832 and depicted the libertine

escapades and adventures of François I of France (1515-

1547), the drama featuring as its primary force, an ugly,

disillusioned, hunchbacked court jester named Triboulet.

Hugo had boldly announced that his plays would no

longer parade one-dimensional protagonists who were either

all-virtuous, or all-villainous. Hugo now created new types

of characters who were complex and ambivalent: personalities

whom he would label “grotesque creatures.” In his play Le

Roi s’amuse, in particular, he created his quintessential

“grotesque creature” in the ambivalent character of the jester

Triboulet: a tragic man with two souls; a physically

monstrous and morally evil, wicked personality, but a

man who was simultaneously, a magnanimous, kind,

gentle, and compassionate human being. Hugo’s

Triboulet – Rigoletto in Verdi’s opera – was outwardly

a physically ugly hunchback, ridiculous and deformed,

as well as mean and sadistic. Yet inwardly, he was an

intensely human creature, a man filled with passion and

unbounded love which he showered on his beloved

daughter. (The name Triboulet is descriptive: it is derived

from the French verb tribouler, meaning to guffaw, to

be noisy, hilarious, or boisterous.)

Verdi had read Hugo’s play Le Roi s’amuse, but

certainly had never seen the play on stage. Hugo’s play

survived only the one night of its premiere in 1832; its

next performance did not occur until 50 years later in

1882. Censors decided to ban the play from the French,

German, and Italian stages, compounding their criticism

by finding its content overly abundant in its immorality

and its repulsiveness.

But Verdi was now in his crusade to seek more

intense operatic subjects, and recognized in Hugo’s story

those sublime operatic possibilities that would stir moral

passions. He sensed that the character Triboulet was a

creation worthy of Shakespeare: a character who took

human nature to its limits, and through whom, new

levels of consciousness would come into being.

Verdi wrote to his favorite librettist of the time,

Francesco Maria Piave, his librettist for his earlier operas

Ernani and Macbeth - and later La Forza del Destino:

“I have in mind another subject, which, if the

police (censors) would allow it, is one of the greatest

creations of modern theatre. The story is great,

immense, and includes a character who is one of the

greatest creations that the theatres of all nations and all

times will boast.

The story is Le Roi s’amuse, and the character I

mean is Triboulet.”

Rigoletto Page 18

There was intense hostility and animosity in the

historical marriage of Hugo’s dramatic sources and Verdi’s

musical treatment of them. Earlier, Hugo had vigorously

denounced Verdi’s operatic adaptation of his play

Hernani - and later his adaptation of Rigoletto – when

they were staged in Paris, and did everything within his

power to prevent public production of what he

considered a literary mutilation of his works, even

unsuccessfully initiating legal action in the Paris courts

to prohibit their performances.

Hugo was admittedly resentful – and even envious

and jealous – of Verdi’s popularity, but his comments

about the famous Quartet from Rigoletto’s final act

represent his reluctant admission of Verdi’s operatic

genius, as well as his tribute to the unique expressiveness

of the operatic art-form. Hugo commented: “If I could

only make four characters in my plays speak at the

same time, and have the audience grasp the words and

sentiments, I would obtain the very same effect.”

Nevertheless, it was Giuseppe Verdi who would ultimately

provide immortality for Hugo’s play, Le Roi s’amuse.

E

urope’s mid-nineteenth century was a time

of revolution and unrest. Napoleon’s defeat and

the political alliances evolving from the Congress of

Vienna (1813-1815), had given Europe’s ruling

monarchies a renewed incentive to protect the status

quo of their autocracies, all of which were being

threatened by ethnic nationalism, the Enlightenment

sense of individual liberty and freedom: new ideological

forces evolving from the transformations caused by the

Industrial Revolution.

The ability of the continental powers to control

artistic truth was directly proportional to the stability

and continuity of their authority. Censorship –

particularly the control of ideas expressed in the arts –

became the vehicle to regulate and determine that

nothing should be shown upon the stage that might in

the least fan the flames of rebellion and discontent.

Kings, ministers, and governments, all reflected an

apparent paranoia, an irrational fear, and an almost

pathological suspicion of ideas. It was through censorship

that they exerted their power and determination to

protect what they considered “universal truths”:

conservatism would overpower progress.

A perfect example of censorship in action occurred in

France in the suppression of Hugo’s play Le Roi s’amuse.

Despite the French Constitution’s guarantee of freedom of

expression, the censors’ rationale for banning Hugo’s play

was simply stated without recourse to argument: they

considered the subject immoral, obscenely trivial, scandalous,

Rigoletto Page 19

and even a subversive threat to the status quo. Similarly, in

Verdi’s Italy, ruled by both France and Austria, censors would

reject and prevent the performance of works whose ideas

they considered subversive, or a threat to the social and

political fabric of their society.

The Verdi/Piave adaptation of Hugo’s Le Roi

s’amuse was initially titled La Maledizione, “The Curse.”

In Verdi’s opera, Monterone’s curse is the engine that

drives the drama. The working out of the curse is the

core, essential dramatic force in which the entire plot

devolves. In the opera story, the aged Monterone calls

upon the divine cosmic powers of good to condemn the

offensive Duke and the slanderous Rigoletto, demonizing

them both, but particularly obsessing and overcoming

the jester with fear and haunting him throughout the

drama: the musical theme echoing throughout the opera

- Quel vecchio maledivami, “That old man cursed me”

- always playing in the same key and with the same

instrumentation. In a similar vein, Alberich’s curse –

the Renunciation of love - provides the dramatic thread

for Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung.

Verdi and his librettist Piave were both very much

aware that their opera La Maledizione would provoke

the Venetian censors – Venice was then under Austrian

rule. Indeed, just three months before the scheduled

premiere of La Maledizione, their battle began. The

Austrian censors exploded, totally rejecting the work

and forbidding its performance, and expressing their

profound regret that Piave and Verdi did not choose a

more worthy vehicle to display their talents, rather

than the revolting immorality and obscene triviality

contained in the text of La Maledizione. The censors

considered the theme of the curse to be blasphemously

offensive to prevailing religious proprieties. Verdi and

Piave were far from naïve and their hope was to bring

the Hugo story to the opera stage without severe

mutilation or injury to its dramatic substance.

Their first concession was to change the opera’s

title: the opera title was changed to its title character,

Rigoletto, an adaptation of the French word rigoler, to

guffaw. But the real thrust of the censors’ main objection

concerned itself with the opera’s obscene and despicable

portrayal of the misdeeds and frailties of King François

I. In the story, the King is represented as an

unconscionable, debauched monarch. Royal profligacy in

action could not be staged, nor a royal plan to abduct a

courtier’s wife (Countess Ceprano), nor a royal keeping low

company in a tavern and becoming entrapped by a lowly

gypsy (Maddalena), and most of all, a King could not be

manipulated by a crippled jester and eventually become his

intended assassination victim.

Rigoletto Page 20

Verdi’s next concession was the substitution of the

Duke of Mantua for King François I: In effect, the Duke bore

the anonymity of any Mantovani, an insignificant ruler of a

petty state rather than an historic King of France. But in

addition, the censors were relentless and demanded that

Rigoletto’s daughter, Gilda, should be substituted with his

sister; that the sleaziness of Sparafucile’s Inn in the final

scene should be altered to eliminate its “aura” of a house of

prostitution; and finally, that they eliminate the repulsiveness

of “packing” Gilda – or his sister - in a sack in the opera’s

final moment.

In a stroke of operatic Providence, Verdi and

Piave were redeemed by none other than the Austrian

censor himself, a man named Martello, who was not

only an avid opera lover, but a man who venerated the

great Verdi as well. Martello made the final decision and

determined that the change of venue from Paris to

Mantua, and the renaming of the opera to Rigoletto

adequately satisfied censor requirements.

From the point of view of both Verdi and Piave,

Rigoletto had arrived back from the censors “safe and

sound, without fractures or amputations.”

T

he core of the Rigoletto drama – and

tragedy – concerns the tensions and conflicts

between a father and daughter: Rigoletto and Gilda. Every

artist trods on autobiographical terrain, and Giuseppe

Verdi certainly cannot be excluded.

Verdi’s operatic “father figures” dominate his

operas. There is a certain psychological truth when

those fathers and their offspring are seemingly alone in

the world. Those fathers obsessively overprotect their

children, and when a child seems to be threatened by an

alternate man, their relationship ultimately leads to an

almost incestuous structure, similar in many respects to

the relationship between Gilda and Rigoletto.

Verdi’s relationship with his own father was full

of constant conflict, tension and bitterness. He claimed

that his father never seemed to have understood him,

and even accused his father of jealousy and envy as he

transcended his parents’ social and intellectual world.

As a result, Verdi was virtually estranged from his father,

but within his inner self, he longed for fatherly affection

and understanding. In a more tragic sense, Verdi’s young

daughter and son died in their childhood, preventing him

from lavishing parental affection on his own children, an

ideal that lies deep within the soul of Italian patriarchal

traditions.

But Verdi would express the paternal affection he

never had, and the paternal affection he could never give to

his own children, in his own unique musical language: his

Rigoletto Page 21

operatic creations became the aftershock of those paternal

relationships he lacked in his own life.

In many of his operas, Verdi presents us with a

whole gallery of passionate, eloquent, and often self-

contradictory father figures, fathers who are passionately

devoted to, but often in conflict with their children.

Those father figures – almost always baritones or basses

- present some of the greatest moments in all of Verdi’s

operas: fathers who gloriously pour out their feelings

with floods of honest emotion and intense passion. In

La Forza del Destino, “The Force of Destiny,” the

tragedy of the opera concerns a dying father laying a

curse on his daughter, Leonora, as the heroine struggles

in her conflict between her love for her father versus

her lover, Don Alvaro. In La Traviata, Alfredo’s father

develops a more profound respect and love for Violetta,

the woman whose heart he has broken because of his

errant son, than for the son for whose sake he has

intervened. The elder Germont’s Piangi, piangi, “I am

crying,” is Germont weeping for Violetta as if she were

his own daughter. In Don Carlos, a terrifying old priest,

the Grand Inquisitor, approves of King Phillip II’s intent

to consign his son to death, the father agonizing and

weeping in remorse and desperation. And in Aïda, a father,

Amonasro, uses paternal tenderness - as well as threats - to

bend his daughter Aïda to his will and betray her lover,

Rhadames.

In Verdi, those fathers are powerful and ambivalent

personalities. The tempestuous passions of fathers churn

the cores of his operas as suffering sons and daughters sing

Padre, mio padre in tenderness, or in terror, or in tears.

Fathers and their conflict with their progeny intrigued Verdi

to such an extent that throughout his life he would

contemplate, but not bring to fruition, an opera based on the

greatest of father figures: Shakespeare’s King Lear; it is

only coincidence that Rigoletto and King Lear are dramas

about paternity that feature a court buffoon.

U

nquestionably, it was the title character

Rigoletto’s passionate paternal love for Gilda, his

daughter, that fired and inspired Verdi to write Rigoletto.

But, the fundamental theme of the entire work concerns

Rigoletto’s profoundly ambivalent character: the tension in

his soul caused by his inner contradictions. Rigoletto is

both virtue and evil. Virtue is attractive; evil is repulsive.

Rigoletto is that ambivalent man with two personalities -

perfectly symbolized by the two puppets his costume bears.

The essence of Hugo’s paradoxical “grotesque

creatures” is that the beautiful and the ugly or the hero and

the villain can exist within one human being. Rigoletto

Rigoletto Page 22

represents that essence of the duality of human character: a

man who is both good and evil: the operatic incarnation of

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Like Macbeth, another ambivalent

character, he is also a man who is human in all his wickedness

and evil: a man full of hate as he is a man full of love: the

defining characteristics of human ambivalence.

Rigoletto’s external deformity and ugliness sets him

aside as a curiosity, an object of humiliation. Rigoletto, like

Merrick’s Elephant Man, or any other freak of nature who is

demeaned by society and looked upon as the “other,” is a

man who believes he is condemned to a living hell. Rigoletto

reasons that his malice derives from his wretched deformity:

his deformity is his justification for his sins and his wrongs,

his bitterness; and his justification for revenge against

Nature. Rigoletto also blames his vile nature and his

hatred of the world on the corrupt Duke and the court

to whose service his deformity has condemned him.

Rigoletto hates the entire corrupt and evil world he

lives in: Rigoletto hates himself.

In his world, where evil is the rule rather than the

exception, Rigoletto readily corrupts his master, willingly

helps the Duke in his seductions, contributes to his

perversion by pimping for him, pushes him further into

vice, and even suggests the murder of any father

(Monterone) or husband (Ceprano) who represents an

obstacle to his lust.

Rigoletto feels justified in mocking the courtiers

because they represent the other evils in the world. He

hates the nobles simply because they are nobles or

simply because these men have no humps on their backs.

As a jester and a merciless cynic, he is ruthless and

mean, eventually provoking his enemies to avenge his

spitefulness, each of whom has at one time or another

been his victim and has felt his sting.

In Rigoletto’s famous soliloquy in Act I, Pari

siamo, “We are all equals,” the moment following

Rigoletto’s encounter with the assassin-for-hire,

Sparafucile, Verdi created an ingenious recitative that

contains all of the formal strength of an aria. Rigoletto

expresses the contradictions in his soul when he

compares himself to the assassin Sparafucile: Rigoletto

is the man with the lethal tongue that is as deadly as the

dagger of the assassin Sparafucile. This is a self-

introspective moment, an admission that he is incarnate

evil: it is an honest personal revelation that he is indeed

mean spirited, unscrupulous, odious, brutish, and

malicious.

Rigoletto Page 23

T

he counter-force to Rigoletto’s hatred of

the Duke and the courtiers is his passionate love for

his daughter, Gilda: that love is the essential ambivalence in

his character. The misshapen jester keeps just one part of

his evil nature pure: his sensitive and passionate love that

he reserves for his beloved daughter. The power of that love

serves to redeem him and forces us to vacillate in our feelings

about him; on the one hand, he repels us as a man of evil, but

on the other hand, we are gradually drawn to him in sympathy,

empathizing with his very human suffering.

Rigoletto keeps Gilda isolated from the vice of

Mantua. He teaches her only virtue and goodness, and

brings her up in innocence, faith, and chastity. His

greatest fear is that she may fall into evil, because being

evil himself, he knows what it is, and he knows what

suffering it causes. Therefore, Rigoletto’s treasured Gilda

is secluded behind high walls, hidden, shielded, and

sheltered from the realities of the wicked world

surrounding her. She has been commanded never to leave

the house except to go to church under the protection

of Giovanna, her nurse. Gilda, the light of Rigoletto’s

life, has become his bird in a cage, an overprotection

that can almost be interpreted as an incestuous perversion

of a father-daughter relationship in the disguise of pure

paternal love.

On the surface, Gilda is a naïve, simpleminded,

and angelic innocent, but her romantic fantasies, her

unconscious erotic desires and yearnings, all come to

life in the ecstasy of her first love. Gilda becomes

overwhelmed - passion overcomes reason - when she

meets her first suitor – the Duke in disguise – a man she

accepts at face value without question.

In a certain sense, as the plot progresses, sweet

Gilda is not all that sugary, nor is she exactly snow-

white in her purity, certainly not a sainted, innocent

maiden. Gilda can be seen as nothing more or less than

a mutinous – if not rebellious – child who defies parental

authority. Gilda not only falls in love with the

“anonymous” Duke, a man she does not know, but

readily consents to sin with him in the sense of her

consensual sexual surrender, what Rigoletto will interpret

as the Duke’s rape of his daughter.

From the very beginning of this story, Gilda is a

disobedient daughter: she lies to her father in Act I when

she fails to respond to his interrogation and reveal to her

father that she is being followed home from church by a

stranger; she will further disobey her father in the final act

by returning to the scene of her lover’s treachery and watch

with broken-hearted incredulity as the libertine Duke tries to

seduce Sparafucile’s gypsy sister and accomplice,

Maddelena.

Rigoletto Page 24

The supreme irony of this father-daughter relationship

is that Gilda has even been shielded from Rigoletto himself:

she has no knowledge of who her father really is, or what he

does. Therefore, perhaps the most pathetic moment of the

opera occurs in Act II when the freshly ravished Gilda sees

her father in his court jester costume for the first time; it is

indeed a tragic moment of shame for both father and daughter.

I

t is Monterone’s curse that falls not only on

Rigoletto in his role as the mocking, cynical court

jester, but also strikes Rigoletto as a father. Rigoletto

becomes, just like Monterone, the tragic father who

likewise loses his treasured daughter to the evil of the

court and the outside world. In the irony of this story,

the same Duke whom Rigoletto urged on to

indiscriminate libertine escapades, ravishes his own

daughter, striking down the jester in his role as father in

exactly the same manner as Monterone.

Rigoletto challenges defeat with denial. He is

unable to face the bitter truth that the Duke ravished

his own daughter, and certainly is unable to believe that

she willingly consented to be bedded by the Duke.

Rigoletto is unable to believe that the evil in the world

has invaded his life, or that the altar that he has built for

his daughter has fallen and has become overturned.

Rigoletto can only vindicate himself by exacting

justice through personal revenge on the Duke. Revenge

is the failure of reason; it is when savagery overcomes

the savage; it is when hatred is recycled; it is when the

order inherent in morality becomes chaos. Rigoletto’s

words of justification: Egli é delitto, punizion son io,

“He is crime, I am punishment.” – revenge reasoned as

“an eye for an eye” rather than “turn the other cheek.”

In the end, the poignant tragedy of this story

unfolds when this vanquished father finds himself alone

with the corpse of his beloved daughter, when revenge

has been foiled, and when the jester again remembers

Monterone’s haunting and portentous curse.

In that final scene, Verdi’s music soars upwards,

taking us to heaven with Gilda. Screams and

melodramatic passion are superfluous when we witness

the beloved daughter dying in her father’s arms, a cathartic,

passionate moment of suffering that honestly portrays that

perennial father-daughter tension so prevalent in Verdi.

Hugo ended his drama with Triboulet’s pathetic screams

expressing his final anguish: “I’ve killed my daughter.” In

Verdi, Rigoletto’s final anguish is: Ah! La maledizione, “Ah!

The curse.” Rigoletto blames the curse and not his own

actions as the cause of his own tragedy, his personal disaster

and catastrophe revealed in the fury and frustration of his

final outburst that expresses his ultimate impotence and the

failure of his will.

Rigoletto Page 25

The Duke is that quintessential operatic cad so familiar

to opera-lovers in the roles of Don Giovanni, Pinkerton, or

Baron Ochs. He is unquestionably a vicious libertine, a man

with a devil-may-care attitude, and a skirt-chaser who lives

for conquest. His signature mottoes are expressed in his two

arias: Quest o quella per me pari sono, “This woman or that

woman, they’re all the same,” or La Donna è mobile, “Woman

is fickle.”

The Duke, like Rigoletto, is also an ambivalent

character. In Act II, the Duke expresses apparent

heartfelt tenderness as he laments his presumed loss of

Gilda, a longing certainly inconsistent with the crudeness

of his historical behavior. In that short, transitory

moment of ambivalent sentiment and compassion, the

repugnant rake gives away to sentimentality for a

moment, exhibiting profound feeling, however fleeting

or momentary his sincerity may be when he praises the

one person in the world who had inspired him with a

lasting love and the fulfillment of his desire: Gilda.

A

fter Verdi’s “middle period” was launched

in 1851 with Rigoletto, his quest for more intense

human passion on the lyric theater stage continued into

his next opera, Il Trovatore. In this opera, his central

character became the swarthy and ominous gypsy

mother, Azucena, a character who dominates the opera

story as she savagely recounts the vivid horror of how

her mother was brutally led to execution.

For Verdi’s 19

th

century audiences, archetypal,

beautiful heroines and handsome heroes were the only

acceptable characters to be seen onstage: villains could

be ugly, but could only be secondary figures.

Nevertheless, with Rigoletto and Azucena, Verdi

introduced exciting wicked people with tragic souls:

shocking and repulsive figures. Verdi proved that in

making these underdogs of society major protagonists,

he was willing to go quite far in his search for the bizarre.

In certain respects, these characters with bloodthirsty

passions, represented the prelude to realism in opera: the

verismo that would overcome the genre toward the end of

the 19

th

century.

To the deeply understanding Verdi, common man

suffers the need for revenge as genuinely as kings, gods,

and heroes. Verdi introduced suffering humanity to the

opera stage: Rigoletto, a hunchback, a mocked and

cynical character and Azucena, a hideously ugly and

reviled gypsy. For both characters, the mainsprings of

their actions is revenge which leads to a tragic irony:

Rigoletto’s decisions bring about the death of his own

daughter, killed by the assassin he hired to murder the Duke;

Azucena causes the death of her adored surrogate son

Rigoletto Page 26

Manrico, first by admitting under torture that she is his

mother, and second, by hiding from her arch-enemy, di Luna,

the fact that he and Manrico are actually brothers, an

admission that could have saved Manrico.

Rigoletto and Azucena are thus the male and

female faces of revenge that become defeated: a revenge

that ultimately brings about fatal injustice and tragedy.

Both operas, Rigoletto and Il Trovatore, are therefore

masterpieces of dramatic irony. The final horror for

both Rigoletto and Azucena is that these protagonists

believe they are striking a blow for justice. Rigoletto’s

final justification is Egli è delitto, punizion so io, “He is

crime, I am punishment.” Azucena repeats her mother’s

plea Mi vendica, “Avenge me.” However, in the end,

both fail and witness their children lying dead, the only

difference between them is that Rigoletto may live on

in agony, while Azucena will surely die at the stake as

did her mother.

I

n Rigoletto, Verdi introduced a treasure chest

of glorious music. The opera explodes with melodically

charged gusts of powerful and romantic passion. This

score brought a vitality to the operatic stage that had

never been heard before. Verdi’s musical language now

spoke with a new momentum and energy; his music now

had an intensity that was brimming over with violent

passions, a dark sinisterism, superstition, self pity, raging

emotion, and even murderous glee.

The opera’s ambience is saturated with a dark and

contrasting brilliance of spirit: those biting, ominous

declamatory phrases as Rigoletto explodes in fear of

Monterone’s curse – La maledizione, or Gilda’s

tenderness in Caro nome, delivered in virtuoso coloratura,

and of course, the Quartet, a universally acknowledged

marvel in which the diverse conflicts of the characters

are exposed to the foreground in a brilliant, coherent

musical unity.

Rigoletto also introduced a more perfect balance

between lyrical and dramatic elements. The score structure

is more integrated and fused to a more elevated level between

text and music than he had ever achieved before. As a result,

all of its musical themes are unified, well proportioned,

precisely arranged, and organically related to the whole: its

sharp and contrasting characterizations and super-charged

emotions overwhelm each scene and swiftly speed the opera

from one breathtaking climax to another.

With Rigoletto, Verdi developed and progressed

beyond the patterns established by his predecessors. Even

though the music score contains separate numbers, in

many instances, his orchestra is not just the traditional

Rigoletto Page 27

accompaniment, but an integral part of the drama. In addition,

Rigoletto contains many beautiful melodic inventions that

link recitative to aria in that no-man’s land or barrier between

the end of an aria, and the beginning of another set-piece.

Rigoletto provides a vocally charismatic tenor role,

but it is the title role, Rigoletto, that remains the greatest part

ever written for a high baritone, requiring every emotional

stop of which the voice is capable.

A

t the time of Rigoletto, Wagner’s theories

of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the ideal of the total

artwork and his conception of the music of the future

started to infest the European opera world; its particular

emphasis, that to create true music drama, there must

be a synthesis and fusion of text and music. Wagner’s

theories eventually transformed and revolutionized 19

th

century opera, but Verdi’s Rigoletto, with its bel canto,

its set-pieces, and its “hit-parade” song style, a certain

degree of accompaniments still built on dance-tune

rhythmic structure, certainly represent the antithesis

of Wagnerism. Nevertheless, Rigoletto is not the music

of the past, certainly not that intolerable kind of

Italianism in lyric drama that the Wagnerians considered

devilish: the operas of Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, and

of course, Verdi.

Rigoletto is a valuable reminder that in spite of

new ideas and transformations, in its widest sense, the

lyric theater does not have to conform to those theories

of perfect music drama in order for an opera to become

and remain a coherent masterpiece. Rigoletto’s musical

lushness and its dramatic passions remain engraved for

eternity. Its musical legacy passes into the world’s mind

just as familiar sentences from literature become catch-

phrases and proverbs. In essence, new currents and trends

arise and swirl up in opera, purer theories take shape,

but Rigoletto holds the stage firmly.

So, in spite of Wagnerisms and the eternal controversy

between the Italian conception of its own operatic music of

the future, the 150 year old Rigoletto goes on and on in

perennial favor. A part of the greatness of Rigoletto lies in

the fact that it indeed reverently and piously follows the

great Italian traditions: a work saturated with beautiful melody

in which the voice and melody reign supreme; an Italian

opera with vivid beauty and spontaneous power; an opera

with gems that seem ageless and continue to remain bright -

the Duke’s Questa o quella and La donna è mobile; Gilda’s

Caro nome and confessional Tutte le feste, Rigoletto’s Pari

siamo and Cortigiani, the Si vendetta duet, and, of course,

the Quartet.

Rigoletto Page 28

V

erdi himself described Rigoletto as

revolutionary, if not a landmark in his career: “the

best subject as regards theatrical effect that I’ve ever

set to music. It has powerful situations, variety,

excitement, pathos; all the vicissitudes arise from the

frivolous, rakish personality of the Duke. Hence,

Rigoletto’s fear, Gilda’s passions….”

Although 13 operas would follow, Rigoletto would

always remain Verdi’s favorite work throughout his entire

career. The reason may be that Rigoletto is saturated and

integrated with a strong dramatic and lyric beauty: poignant

expressions of emotion and pathos, despair, romantic

agonies, passions of love, and, of course, that tempestuous

fury that churns the opera: revenge.

Rigoletto is one of Verdi’s supreme lyrical

masterpieces: a late flowering of the Italian romantic

tradition. Verdi would go forward into his “middle period”

to create some of the most enduring works of the operatic

canon. Starting with Rigoletto, Verdi began to compose

in a totally new spirit with bolder subjects containing

greater dramatic and psychological depth.

Nevertheless, his Rigoletto represents, in effect,

the sum and substance of Italian opera, and, as such,

survives as one of opera’s supreme masterpieces.

Rigoletto Page 29

Rigoletto Page 30

Rigoletto Page 31

Rigoletto Page 32

Document Outline

- Rigoletto the Opera Journeys Mini Guide Series 0967397375

- Cover

- Title Page

- Story Synopsis

- Principal Characters in the Opera

- Story Narrative and Music Highlights

- ACT 1 Scene 1: A Salon in the Ducal Palace

- ACT II: A drawing room in the Duke’s Palace

- ACT III: Sparafucile’s Inn on the deserted banks of theMincio River.

- Verdi and Rigoletto

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

więcej podobnych podstron