From Morality to Metaphysics

This page intentionally left blank

From Morality

to Metaphysics

The Theistic Implications

of our Ethical Commitments

Angus Ritchie

1

3

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP,

United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University

’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of

Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

# Angus Ritchie 2012

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2012

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the

prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted

by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics

rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the

above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the

address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN 978

–0–19–965251–8

Printed in Great Britain by

MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King

’s Lynn

To my parents,

with love and gratitude

Acknowledgements

Ralph Walker

’s influence on this work is manifold—in the personal and

philosophical inspiration he has provided since my undergraduate days;

in his patience and diligence as a doctoral supervisor, and in his typically

fair-minded insistence that he should have a co-supervisor with rather

different views. As this book is a reworking of my doctoral thesis, my

first expressions of thanks are to him and his co-supervisor Sabina

Lovibond (who deepened my engagement with the work of John

McDowell and Philippa Foot in particular). Thanks are also due to

Sabina Alkire, John Deacon, Rob Gilbert, Amanda Greene, Mark

Hopwood, Philip Krinks, Michael Piret, David Staples, Richard Taylor,

and Mark Thakkar for stimulating discussions and wise counsel; to my

doctoral examiners Tim Mawson and John Cottingham for their very

helpful advice and encouragement, and to Peter Momtchilloff for his

assistance in the process of turning my thesis into a book.

It is often argued that faith must be kept out of politics, for reasons both

practical and theoretical. Practically, it is said that religion is a divisive

force. Theoretically, it is claimed that religious beliefs (unlike other kinds

of conviction) are immune to rational debate and correction. I have now

spent over a decade in ministry in East London, all of it in churches

organizing for social justice alongside other faiths. The witness of those

churches has been a crucial inspiration for this work. Community organiz-

ing offers a very practical example of the positive role of faith in public life.

In this book, I seek to complement this with a more theoretical argu-

ment

—showing the openness of religious belief to rational debate.

Through her love, encouragement, and practical support, Jennifer Lau

has contributed more to this work than she knows. It was her misfortune

that my last year of thesis writing was the

first year of our relationship, and

the year of its conversion to a book was the

first year of our marriage. Her

loss has undoubtedly been my gain, and this acknowledgment comes with

heartfelt love and gratitude. I am also thankful to my parents-in-law,

Chau-Kiong and Kim-Heung Lau, for their hospitality as the

final draft

was prepared.

I

first learnt of God and goodness from my family, and from the wider

community in which I spent my childhood. I am deeply grateful to them

all

—to the Church of Scotland congregations in Ardersier and Petty, to

my brother John, and above all to my parents, Garden and Kathleen

Ritchie, to whom this book is dedicated.

Limehouse, East London

The Feast of the Epiphany, 2012

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

vii

This page intentionally left blank

Contents

1. Why Take Morality to be Objective?

2. The Gap Opens: Evolution and our Capacity

3. Alternatives to Realism: Simon Blackburn

4. Procedures and Reasons: Tim Scanlon and

5. Natural Goodness: Philippa Foot

John McDowell and David Wiggins

7. From Goodness to God: Closing the Explanatory Gap

This page intentionally left blank

1. Con

flicting Impulses in Moral Philosophy

What are the raw materials which

‘moral truth’ is constructed? Is it

constituted (or generated) by facts about human sentiments and cultural

conventions? Or is there an objective moral reality, existing prior to those

sentiments and conventions, in virtue of which some moral statements are

true and others are false?

Faced with these questions, most students of philosophy feel two

con

flicting impulses. The first might be called the pull of reductionism.

At its crudest level, this re

flects the common conviction that the only

things really

‘out there’ are the entities described by the physical sciences.

If this conviction is correct, then what people call

‘moral truth’ will be

accounted for by reference to human sentiments, preferences and cultural

conventions, and not to an ontologically independent moral reality.

Competing with this

first impulse is the pull of objectivism. Students

will no doubt accept that some of their attitudes are culturally conditioned.

However, they will

find it hard to do justice to their deepest commitments

without making claims which are more metaphysically ambitious. Sooner

or later, whether in the seminar room or the college bar, the case of the

Holocaust or the Killing Fields will be raised. Few students are willing to

deny that the evil of Hitler or Pol Pot is in some sense absolute.

Such con

flicting impulses are clearly present when students begin a

degree course in philosophy. Oxford University

’s Examiners’ Reports

suggest that three or four years of study do little to resolve the ambiva-

lence. A recent report on the scripts for one of the ethics questions in

Philosophy Finals makes the following comment:

The name most often mentioned in candidates

’ scripts was that of Kant, who

featured in 97% of scripts. The second most often mentioned name was that of

Hitler, who appeared in 91% of scripts. Almost all of this latter group would have

been crude moral relativists if they had not suddenly thought of Hitler halfway

through their answers.

1

The examiners clearly felt the question demanded a rather more nuanced

response, and that too many students had given an answer which careered

from one extreme to the other

—between the competing ‘pulls’ identi-

fied above. There is of course important intellectual terrain to explore in

between the extremes:a growing number of philosophers have turned their

backs on a wholesale reductionism, but have sought to accommodate the

language of

‘moral truth’ and ‘absolute’ good and evil within a more modest

an ontological framework. Such thinkers are keen to avoid any suggestion

that the universe itself has some kind of purpose behind it, whether a causally

ef

ficacious Good (as in axiarchism) or the will of a benevolent Creator.

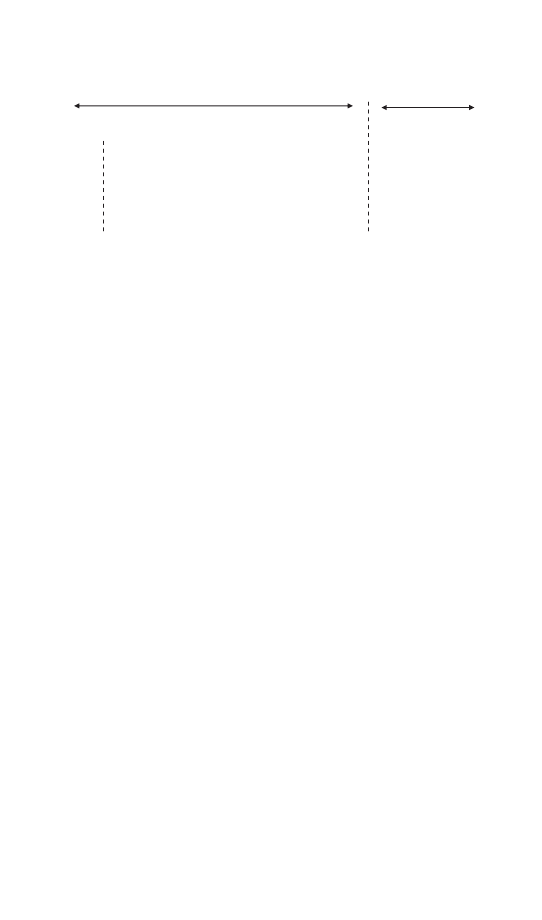

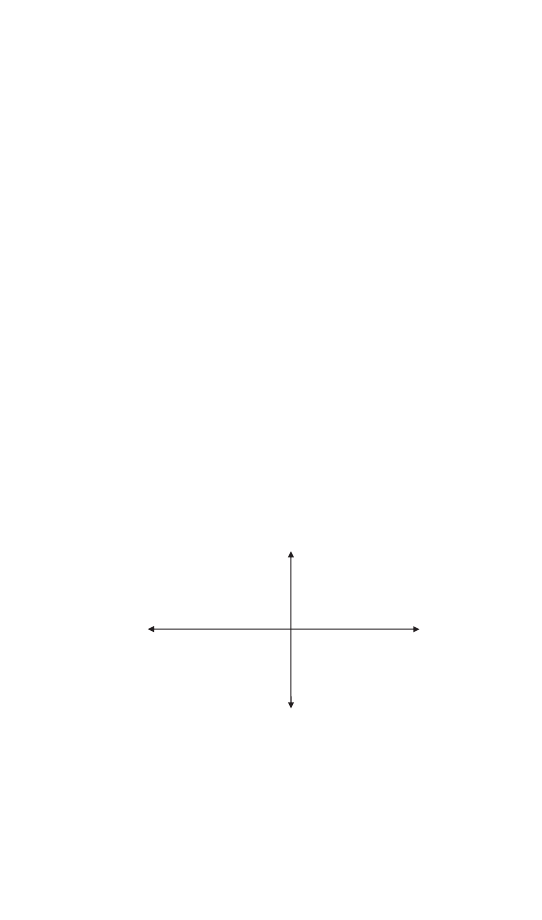

Figure 1 places a range of contemporary philosophical positions on a

continuum, depending on how they respond to the con

flicting pulls.

Inevitably, such a diagram is rather rough-and-ready, as the nuances of

each position are forced into just two dimensions. At one extreme is

the error theory of John Mackie. This account is so in

fluenced by the

pull of reductionism that it regards the objectivism in humans

’ pre-

philosophical moral attitudes as entirely mistaken. At the other extreme

are theistic and axiarchic positions, which seek to answer the epistemolog-

ical and ontological questions under discussion with reference to a purpose

which, they claim lies behind the universe as a whole. In the middle,

between the dotted lines, lie positions which seek to accommodate both

pulls. While they differ in many other ways, these intermediate positions

all share two properties. Firstly, they are

‘secular’ in that they deny the

universe has any intrinsic purpose: the existence and nature of the universe

are not to be explained by either an agent (as in classical theism) or the

causal power of the Good (as in axiarchism). Secondly, they all seek to

vindicate the incipient objectivism in humans

’ pre-philosophical moral

attitudes. Although some of these intermediate positions attempt to ac-

commodate these attitudes within in an ontology every bit as modest as

Mackie

’s, what distinguishes all these positions from his is that they refuse

to regard our fundamental, pre-philosophical objectivism as an

‘error’.

1

I owe this quote to Bob Hargrave

’s online guide to ‘How to Fail Philosophy Exams’, at

ball0888/oxfordopen/Rodin.htm>

2

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

2. Argument of this Book

This book offers an argument for theism. Its claim is that only purposive

accounts of the universe both do justice to our pre-philosophical moral

commitments and explain the human acquisition of belief-generating and

belief-evaluating capacities which track (an ex hypothesi independent)

moral truth. Among such purposive accounts, it claims that theism

offers the most satisfying, intelligible explanation of this phenomenon.

It is important to stress from the outset that this book will not advance a

more general case for theism. Nor will it address the other grounds on

which secular philosophers might reject religious beliefs. The sole purpose

of the book is to highlight a serious and systemic problem facing any

secular positions that attempts to accommodate our pre-philosophical

moral commitments. (In terms of Figure 1, these are the range of positions

which lie between the dotted lines.)

In varied ways, these secular accounts seek to mediate between the

con

flicting pulls of objectivism and reductionism. At one extreme, Simon

Blackburn, Allan Gibbard, Christine Korsgaard, and (in his earlier writ-

ings) Tim Scanlon argues that our fundamental moral convictions can be

accommodated without objectivism. At the other, Philippa Foot, Roger

Crisp, and the later Scanlon seek to combine a fully objectivist account of

moral norms with an explanation of human knowledge of these norms

which does not involve a purposive agent or force. John McDowell

’s

position is harder to categorize, as it rejects any

‘sideways-on’ view

from which the world and our conceptual schemes could be compared.

McDowell describes his general philosophical position as

‘anti-anti-realism’.

NON-PURPOSIVE (‘SECULAR’) ACCOUNT OF UNIVERSE

PURPOSIVE ACCOUNT

ERROR

THEORY

(Mackie)

MORAL QUASI-

REALISM

(Blackburn / Gibbard)

‘ANTI-ANTI–

REALISM’

(McDowell)

OBJECTIVISM

(Crisp / later Scanlon)

THEISM

CONSTRUCTIVISM

(Korsgaard / early Scanlon)

NATURALISM

(Foot)

AXIARCHISM

(Rice / Leslie)

< < Pull of reductionism

Pull of objectivism >>

Figure 1 The continuum of moral philosophy

INTRODUCTION

3

For these purposes, what matters is that he regards moral truth as every bit as

‘real’ and ‘objective’ as any other kind.

This book claims that all such secular accounts are problematic. Their

individual

flaws flow from systematic weaknesses—weaknesses which

make it doubtful that any future secular account could fare better. These

weaknesses are twofold. In the case of the less objectivist theories (on

the left of the diagram) the concessions made to reductionism leave

themunable to do justice to humans

’ most fundamental moral convictions.

The accounts on the right, which accommodate the pull of objectivism,

face a different problem. These more objectivist theories generate an

‘explanatory gap’.

This brings us to the central contention of the book. My claim is that

all secular theories which do justice to our most fundamental moral

convictions go on to generate an insoluble

‘explanatory gap’. This ‘gap’

consists in their inability to answer the following question:

(Q)

How do human beings, developing in a physical universe which

is not itself shaped by any purposive force, come to have the

capacity to apprehend objective moral norms?

It is important to stress that (Q) concerns the explanation for humans

’

possession of truth-tracking capacities with respect to morality. It does

not concern the justi

fication we have for relying on the deliverances of our

belief-generating mechanisms. I do not deny that secular thinkers have

some reason to trust the human capacity for moral discernment. My claim

is that all otherwise satisfactory secular accounts generate an explanatory

gap with respect to human knowledge of moral truth.

3. Structure of the Argument

The book has a threefold structure. The

first part advances the prima

facie case against those secular accounts which posit an objective moral

order

—namely, that they generate an explanatory gap. The second part

considers the resources secular accounts might have to bridge the gap, or to

avoid it by deploying a weaker conception of objectivity. It argues these

resources are insuf

ficient. The third section develops an argument for

theism

—arguing, firstly that purposive accounts of the universe are the

only kind which can avoid this explanatory gap, and secondly that theism

is the most satisfying of these accounts.

4

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

I will now sketch out how the argument develops, chapter by chapter.

Part I: The Explanatory Gap Emerges

The argument just outlined only has force if the

‘pull of objectivism’ needs

to be respected. The explanatory gap can very easily be avoided if there is

no objective moral order. So my

first task is to explain why we must take

morality to be (to at least some degree) objective; only then does the

explanatory question arise.

Chapter 1 defends our pre-philosophical commitment to moral

objectivism. It is an essential prelude to the main argument, for it sets

the standard by which I will determine which secular accounts are

‘suffi-

ciently

’ objective. This part of the book is not so much a defence of moral

objectivism as an outline of the considerations I take to count in its favour.

Readers seeking a comprehensive defence, rather than the sketch of one,

will need to refer to the thinkers I draw on and cite.

In claiming that humans have the capacity for apprehending an

objective moral order, I will not be making extravagant claims about the

accuracy of our existing moral beliefs. Nor will I presuppose an optimistic

picture of how the con

flicting moral convictions of today’s humans will or

will not converge in the future. The argument of this book just requires

two much more modest assumptions. It assumes that in our moral

re

flection, each of us seeks to approximate to a truth beyond ‘whatever

I think is true

’. I also assumes that this quest is not in vain: which is to say,

that humans have some capacity to attune their beliefs more closely to

thatmoral truth, when they honestly and carefully seek it out. The purpose

of Chapter 1 is to explain why I take these assumptions to be justi

fied.

In Chapter 2, I develop the prima facie case for thinking all secular

moral theories which are

‘sufficiently’ objectivist will also generate an

‘explanatory gap’.

This explanatory gap is a distinctive problem for secular accounts of

moral knowledge. For the sake of this argument, I am happy to concede

that human sensitivity to facts about the physical world or norms of

theoretical reasoning can be explained without invoking any purposive

force or agent. Natural selection shows the survival value of having

accurate beliefs about key features of physical reality and the principles

of theoretical reasoning

—even if we take both of these to exist indepen-

dently of the sentiments, beliefs or social conventions of the perceiver. It is

INTRODUCTION

5

only in the case of evaluative beliefs that the survival value and the

accuracy of beliefs seem to come apart. It is likely that, if their belief-

generating faculties emerged from a combination of random mutations

and selective pressure, humans would have acquires moral convictions

which aided their survival and propagation. But it is not clear why those

convictions would correspond with the moral truth rather than selectively

advantageous simulacra. This is the heart of the explanatory gap: Why are

our capacities with respect to morality capable of tracking truth?

Why do we need an explanation for our truth-tracking capacities with

respect to morality? Why can we not answer the question of how

we apprehend moral truths by giving an anthropological account

—telling

the story of how parents, carers, and communities inculcate in their young

the very moral beliefs we all accept are justi

fied? Showing that we have

reason to trust our belief-generating faculties and telling a story of how

each new generation is inducted into the community of reasoners does not

provide an answer to (Q). For (Q) asked why we are fortunate enough to

have such truth-tracking faculties. We must not confuse an anti-sceptical

argument which justi

fies the trust we place in our faculties with one which

explains their accuracy. In the case of theoretical reasoning, we have the

kind of explanation I am demanding. For, as well as having (i) an argument

to the effect that we must trust our faculties, and (ii) an anthropological

and sociological story about how children are inducted into the commu-

nity of reasoners, we also have (iii) an explanation of why this community

has reliable faculties for reasoning. In the moral case, I argue we have (i)

and (ii) but lack (iii). This is why I claim that the case of moral knowledge

is particularly problematic for secular philosophers, and a distinctive

‘explanatory gap’ arises in this domain.

Part II: Secular Responses

In Part II, I examine some of the most prominent and powerful secular

accounts. I will argue that none of them manages avoid the following

dilemma: either the positions fail to vindicate our pre-philosophical

commitment to objectivism or they generate an explanatory gap. The

particular positions which I consider do not exhaust the conceptual

space open to the secular thinker

—so this book is not offering a ‘knock-

down

’ argument against all possible accounts. It is highlighting a serious

problem that naturalism

’s most prominent advocates have yet to solve, and

6

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

identifying systemic reasons for their failure which make it unlikely

that new variants will succeed.

Chapters 3 and 4 consider secular positions that fall short of objectivism.

The promise in all these positions is that they will do justice to our

pre-philosophical moral commitments without generating the

‘explana-

tory gap

’ which befalls full-blown objectivism.

Chapter 3 discusses quasi-realism, the position developed by Simon

Blackburn and Allan Gibbard. I will argue that it fails in two key respects.

Firstly, it makes our concern to learn from the insights of others rather

mysterious; whereas for an objectivist it is clear why moral sentiments very

different from our own have epistemic relevance. Secondly, it cannot give

a plausible account of future changes in our moral sensibilities.

Chapter 4 considers Timothy Scanlon

’s account of ethics. Like quasi-

realism, Scanlon

’s early position avoids the metaphysical commitments

which generate the

‘explanatory gap’. However, I will argue, the position

is unable to do justice to the inescapable ethical commitments outlined in

the

first chapter. Scanlon draws heavily on Christine Korsgaard for his

meta-ethical account, so the chapter will also consider of her

‘procedural

moral realism

’, arguing it shares the fundamental flaws of quasi-realism.

Finally, it turns to the more objectivist position developed in Scanlon

’s

2009 John Locke Lectures. While this position avoids the problems faced

by Blackburn, Gibbard, and Korsgaard, I will argue that it does so at the

price of generating the explanatory gap.

In Chapter 5, I will consider Philippa Foot

’s naturalist realism, which

treats moral properties as features of the natural world. I will argue that her

account defends a notion of

‘goodness’ too weak for our purposes.

A notion of moral correctness is required which transcends this species-

relative property. Chapter 6 examines John McDowell

’s ‘re-enchanted’

naturalism; a position that builds on Foot

’s and seeks to answer this

objection. Once again, I argue the position falls foul of the explanatory

gap. McDowell seeks to avoid this conclusion, by arguing that the kind of

explanation I am seeking is inappropriate. This returns us to the argument

of Chapter 2: that it is legitimate to ask for an explanation, because natural

selection can account for the way many of our other beliefs come to track

the truth. Chapter 6 concludes with a brief discussion of David Wiggins

’

weaker conception of objectivity in ethics. I will argue that Wiggins

’

position offers further con

firmation of my central thesis: that the

INTRODUCTION

7

explanatory gap is only evaded by positions which fail to do justice to

our pre-philosophical commitments.

While Parts I and II of this book consider a wide range of secular

accounts, the list is far from comprehensive. For example, it lacks a detailed

discussion of the

‘Cornell realism’ of Richard Boyd, Nicholas Sturgeon,

and David Brink, or the moral functionalism of Frank Jackson. While

these positions are distinctive in other ways, the objections advanced

against the positions listed above will (if successful) tell against these

and other secular accounts. I will indicate brie

fly in Chapters 2 and 5

where I take my arguments against quasi-realism and Foot

’s naturalism to

tell against Jackson and the Cornell realists respectively.

Offering a treatment of every secular account

—even if such a Hercule-

an labour were achievable

—would be incredibly tedious for reader

and author alike. My argument against each secular account is to press

upon them the same dilemma: either insuf

ficient objectivity to vindicate

our

first-order commitments or the generation of an explanatory gap.

To preserve the reader

’s good humour (as well as my own) I have limited

myself to advancing this dilemma against the

‘error theory’ and straight-

forward moral objectivism in Part I of the book, and against four of

the most plausible and distinctive intermediate positions in Part II.

Part III: Theism

The

final section of this book advances a positive case for theism.

In Chapter 7, I will defend the legitimacy of teleological explanations,

and in particular explanation in terms of the intentions of an agent. I will

argue they are uniquely are capable of accounting for the way we must

take the characteristics of the objective moral order to shape the convic-

tions and capacities of human beings. In consequence (and in contrast to

their secular counterparts) they are able to explain the human capacity for

apprehending the objective moral order. In Chapter 8 I will argue against

the axiarchism of Hugh Rice and John Leslie, claiming only classical

theism and a non-axiarchic Neoplatonism offer satisfactory explanations.

At the end of the chapter, I argue that classical theism offers the most

intelligible and comprehensive such explanation.

8

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

This page intentionally left blank

Why Take Morality to be

Objective?

1.1 Aim and Structure of the Chapter

The

first task of this book is to explain why we should take morality to be

(at least quasi-) objective. It is only if moral truth is in some sense objective

that the

‘explanatory gap’ will arise. If moral truth is constituted or

generated by our sentiments and cultural conventions, then the question

of how our moral beliefs succeed in tracking the truth is easily answered.

Much of the pull of objectivism comes from our pre-philosophical

moral commitments. Confronted with certain phenomena, most obviously

extreme evils, we feel compelled to say their moral properties are (in some

sense) absolute. This chapter will argue that we have good reason to retain

these commitments.

The chapter has a twofold structure. Firstly, it challenges the

‘pull of

reductionism

’, addressing the most popular criticisms of our pre-

philosophical moral commitments. These criticisms concern the (allegedly

problematic) ontology and epistemology of objective moral norms. My

argument will be that even moral sceptics are committed to the view that

there are objective norms of theoretical reasoning with equally

‘problem-

atic

’ properties. Therefore, these alleged problems cannot constitute a

decisive objection.

The second part of the chapter offers a more positive argument which

builds on the same claim: that all humans are committed to the objectivity

of norms of theoretical reasoning. I will argue that we are committed to

such norms because they underwrite practices which are indispensable to

human thought and action. When we come to such practices (e.g. infer-

ence to the best explanation) we have reached

‘bedrock’. I will argue that

human beings are committed to the objectivity of moral norms for much

the same reason. Such objective norms are

‘deliberatively indispensable’—

they are essential to practices which are central to all of our lives. I will

maintain that it is impossible to engage in moral deliberation without

taking oneself to be aiming at a normative truth that goes beyond one

’s

own sentiments or the conventions of one

’s culture. Therefore, outside

the seminar room it is impossible for human beings to avoid a practical

assumption of moral objectivism. (That is the reason for giving this book

the subtitle

‘The theistic implications of our ethical commitments’.)

As I explained in the Introduction, the argument for moral objectivism

can only be advanced in outline form. Such a sketch needs to be given,

because the central claim of this book is that all secular accounts of morality

are either

‘insufficiently objective’ or generate an ‘explanatory gap’. This

chapter will establish standard against with these secular theories will be

assessed in the rest of the book; the standard by which I will argue theories

such as Simon Blackburn

’s and Christine Korsgaard’s are ‘insufficiently’

objective. The chapter is not designed to convince a reader with a worked-

out case against moral objectivism to revise his or her viewpoint. Rather, it

summarizes the arguments this author

finds convincing, and on which the

rest of his case will be built

—and refers sceptical readers to the places where

they are advanced more fully.

1.2 Arguments Against Objectivism

J. L. Mackie

’s Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong remains the classic modern

argument against objectivism.

1

Mackie thinks the ontology of moral

judgements is problematic for the objectivist (in his terminology, he thinks

there is a

‘queerness’ to such judgements). For it ascribes to such judge-

ments a combination of objectivity (claiming they are there independent

of any agent

’s motivational structure) and bindingness upon the rational

will (claiming they have a

‘built in to-be-pursuedness’).

The objectivity of moral judgements raises serious epistemological

issues. It looks as if we have trustworthy ways of evaluating analytic

statements (i.e. by linguistic analysis), and it is trivially true that we have

reliable ways of evaluating those statements that are empirically testable.

What, then, of this third category into which moral judgements seem to

1

J. L. Mackie, Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1977).

12

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

fall? (In fact, some philosophers do take moral statements to be analytic;

I will outline my reasons for rejecting this position below at 2.5.4.)

Mackie thinks that all moral objectivists are ultimately committed to

some kind of intuitionism:

[T]he central thesis of intuitionism is one to which any objectivist view of values is

in the end committed: intuitionism merely makes unpalatably plain what other

forms of objectivism wrap up

. . . [H]owever complex the real process, it will

require some input of this distinctive sort, either premises or forms of argument

or both. When we ask the awkward question, how we can be aware of this

authoritative prescriptivity

. . . ‘a special form of intuition’ is a lame answer, but it

is the one to which the clear-headed objectivist is compelled to resort.

2

Mackie

’s epistemological objections are reinforced by the extent of moral

disagreement between agents and between cultures. At

first blush, non-

objectivist theories look better equipped to explain the continuation of

apparently irresoluble differences in moral judgements. If there were the

same kind of objectivity to truth in ethics as in the physical sciences, one

might expect the former subject to have a similar degree of consensus to

the latter.

1.3 Responses

1.3.1 Analogy with theoretical reasoning

In the face of these objections, why not accept that morality is expressive

rather than objective? Later in the chapter, I will advance the positive case

for objectivism. At this stage I simply want to sketch a reply to Mackie

’s

negative arguments. My response will be to argue we are committed to the

existence of other norms of reasoning with the same ontological and

epistemological properties.

If there are objective, non-analytic norms in other areas of judgement,

this will remove a major motivation for denying there are objective moral

norms. For we would have shown that there are indeed true statements

which share the following pairs of features:

1) They are both descriptions of entities and are also prescriptive to

those rational agents who come to know their truth,

2

Mackie, Ethics, 38

–9.

WHY TAKE MORALITY TO BE OBJECTIVE

?

13

and

2) They are neither analytic nor knowable by empirical research

alone.

Even if we restrict ourselves entirely to the physical sciences, it looks as if

some norms with features (1) and (2) must exist. For it is hard to see how

we make choices between rival hypotheses without invoking such norms

of theory-choice.

I want to suggest that these norms of theoretical reasoning are (in David

Enoch

’s phrase) ‘deliberatively indispensable’.

3

By this I mean that while

scepticism about these norms is in principle possible, in practice all rational

agents must behave as if they are objective.

Enoch introduces the concept of deliberative indispensability with an

example. A physicist sees the vapour trail in a cloud chamber, and infers

the presence of a proton. The physicist

’s hypothesis (or, rather, the

complex theory of which it is a small part) is the best scienti

fic explanation

for the phenomenon in question. The principles for determining what

counts as a good explanation can be denied without self-contradiction,

and there is nothing

‘beneath’ these principles which we can use to offer a

non-circular justi

fication. None the less, it is indispensable to our deliber-

ation that we take there to be objective principles which tell us what

conclusions to draw in these cases and thus what the best explanation

consists in. We cannot engage in any serious attempt to make sense of the

world around us without principles of Inference to the Best Explanation

(IBE). Moreover, giving up the attempt to make sense of that world is not

a realistic alternative.

When we choose between rival theories, we rely upon a number of

principles of IBE. We favour those hypotheses which explain the most,

those which are least ad hoc and (arguably) those which are simplest and

most elegant. The precise list of qualities which the best explanation

should display, and the weighting attached to each, may be a matter of

ongoing debate. None the less, if empirical evidence provides us with

grounds for believing anything beyond what is logically deducible from

observation sentences, then some such set of principles must govern our

3

I owe this phrase to David Enoch,

‘An Outline of an Argument for Robust Metanor-

mative Realism

’, in Russ Shafer-Landau (ed.), Oxford Studies in Metaethics, vol. II (Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2007), 21

–50.

14

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

inferences. The principles in question must be normative and descriptive,

for they tell us what we ought to accept on the basis of the evidence.

Might the norms of theoretical reasoning be analytic truths? Surely not:

disagreement about their content cannot plausibly be reduced to debates

about the meanings of words. While the principle of Inference to the Best

Explanation is deliberatively indispensable, there is a substantive debate

within the philosophy of science about the precise qualities which earn a

theory the title

‘Best Explanation’. In particular, there is disagreement as to

whether elegance and simplicity count in favour of a theory being the

‘Best Explanation’, and hence provide grounds for thinking that theory

likely to be true. Likewise, there seems to be a substantive disagreement

between philosophers as to whether there is a distinct norm of theoretical

reasoning which validates the Principle of Induction, or whether (as

Gilbert Harman argued) it is possible to account for the logic of scienti

fic

discovery without such a bedrock principle.

For the purposes of this book, it does not matter which side is right in

each of these debates. All that matters is that each dispute is clearly a

substantive one, not merely a matter of linguistic analysis. There is a fact of

the matter about whether the principle of induction ought or ought not to

be relied upon, and a fact of the matter about whether elegance and

simplicity are part of what it is to be the

‘Best Explanation’.

4

The truth

in question is non-analytic. It appears therefore, that in our theoretical

reasoning we are committed to the existence of synthetic a priori impera-

tives (i.e. ones not reducible to the imperatives of logical inference) which

tell us what conclusions we ought to draw from the evidence generated by

empirical observation and experimentation. In consequence, it seems that

the existence of non-analytic norms of theoretical reasoning is delibera-

tively indispensable for any humans who want to explain and predict

features of the world around them.

What one should say to a sceptic who doubts the existence of any such

objective norms? Perhaps she will agree with us that the norms are indis-

pensable to the project of explaining our immediate observations, but will

then point out we have no independent reason to think the world is explicable.

How do we know our best principles of IBE help us to track the truth?

David Enoch offers a convincing ad hominem response to the sceptic:

4

Gilbert Harman,

‘The Inference to the Best Explanation’, The Philosophical Review 74

(1965).

WHY TAKE MORALITY TO BE OBJECTIVE

?

15

The explanatory project is intrinsically indispensable because it is one we cannot

—

and certainly ought not to

—fail to engage in, it is unavoidable for we are essentially

explanatory creatures. Of course, we can easily refrain from explaining one thing or

another, and it

’s not as if all of us have to be amateur scientists. But we cannot stop

explaining altogether, we cannot stop trying to make sense

—some sense—of what

is going on around us.

Because the practice of explanation is indispensable, and principles of IBE

are indispensable to that practice, we have to take them to be truth-

tracking.

Could the sceptic reply that, while these

‘explanations’ may be prag-

matically useful, that they are no guide to anything objective? The dif

fi-

culty for such a sceptic is that, in the very act of arguing for scepticism she

will have to rely on some synthetic a priori principles. That is to say, any

reasons she has for claiming that the world is

‘unlikely’ to resemble our

theories must itself rest upon an account of what we are entitled to infer on

the basis of any given piece of evidence. If the sceptic

’s view is that ‘we

have no reason to think the world explicable

’, then unless this is a simple

dogmatic assertion (the very thing to which the sceptic claims to be averse)

evidence will need to be provided. Given that the evidence will not entail

the truth of the sceptic

’s claim (for otherwise she would be able to show his

opponents to be caught in a contradiction), the sceptic will be relying on

the very kinds of principle she is supposed to be denying. In short, she will

be caught in a practical contradiction. To assert that anything at all is a basis

for believing anything else, beyond what is provable by deductive argu-

ment, involves an appeal to principles of IBE.

1.3.2 Re

flective equilibrium

The opponent of objectivism may reply that it is not enough for me to

argue that there must be objective norms of theoretical reasoning. Mackie

’s

epistemological worries about such entities need to be addressed more

directly.

I have argued elsewhere that our knowledge of synthetic a priori truths

(in both theoretical and practical reasoning) does not come from deductive

argument or experimental observation, but though a process of

‘reflective

equilibrium

’.

5

Such an

‘equilibrium’ is arrived at through a combination of

5

Angus Ritchie

‘Realism, Ideology, Truth: An Examination of Richard Rortys Critique

of Metaphysical Realism

’ (B. Phil. Thesis, 1996), 47–8.

16

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

(i) singular judgements (which are intuitively compelling to us) and (ii) our

systematization of these judgements into general rules; rules which also

bring them into harmony with the judgements of other people. In a sense,

then, Mackie is correct to say that moral objectivism involves

‘intuition-

ism

’, in that the raw materials of the process of reflective equilibrium

include the singular judgements that seem most intuitively compelling.

This is not a precursor to epistemic anarchy. For this combination of

intuition and systematization is a feature of all human reasoning.

In scienti

fic theory-formation, mathematics and ethics alike we con-

stantly attempt to systematize singular judgements into general rules. On

occasion it may be an open question whether to put up with the counter-

intuitive consequences of accepting a rule (be it a principle of theoretical

reasoning or a moral norm), or whether the counter-intuitive case should

be taken as a counter-example to the rule.

In a paper which predates Mackie

’s book by some years, J. R. Lucas

shows that this dialectic between singular case and general principle is

essential in a wide range of subject areas.

6

His most striking example is

taken from a courtroom where the judge is deciding a contestable point of

law. In such cases, judges do not merely enforce the law. They determine

it. The question then is how such determination is made. As Lucas argues:

[Good judges] do not decide the cases in accordance with some bad rule

—say that

of deciding for the party which bribes them most

—or they would be bad judges.

Nor do they show their impartiality by deciding cases by the toss of a coin in court;

or they would still be bad although now impartial judges. But they do not decide

the case according to some good rule: else the parties would have been able to see

what the decision was going to be and would have settled out of court. So good

judges decide their cases neither according to any rigid rule, good or bad, nor

randomly, that is accordingly to a no-rule. There is thus not an exhaustive

disjunction between being in accordance with some de

finite rule and being

completely unruly, between the conclusively justi

fied and quite unjustified.

7

Lucas

’ argument suggests a way to avoid the dilemma Mackie wishes to

force upon the moral objectivist: either statable rules or an epistemological

free-for-all. In ethics, as in other

fields, rationality involves singular judge-

ments as well as the deductive application of principles. Although Lucas

6

The term

first comes to Prominence in John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Cambridge,

MA: Belknap, 1971), 48.

7

J. R. Lucas,

‘The Lesbian Rule’, Philosophy 30 (1955): 114, 200.

WHY TAKE MORALITY TO BE OBJECTIVE

?

17

does not use the term

‘reflective equilibrium’ it is just such a process that

his paper describes. In doing so, he anticipates contemporary philosophers

such as Timothy Scanlon (whose 2009 John Locke lectures argue we are

committed to

‘reflective equilibrium’ thinking in our theoretical as well as

practical reasoning) and Robert Audi (whose

‘moderate intuitionism’

explicitly includes this process

—and is compatible with the more general

account I am developing).

8

1.3.3 Commitment to objectivity of truth

The argument above assumes that if science and mathematics are episte-

mologically

‘on all fours’ with ethics, this provides a reason for taking

moral truth to be objective. One could of course draw the opposite

conclusion, and reject objectivism in all areas of knowledge. This is exactly

the line taken by Richard Rorty. Rorty claims that developments in

the philosophy of science and of language (in particular the work of

W. V. Quine and Donald Davidson) show

‘we no longer have dialectical

room to worry about

“how language hooks on to the world”’.

9

I have argued elsewhere that Rorty

’s position is ultimately self-refuting:

like the sceptic considered above he is caught in a practical contradiction.

For, if we do

find Rorty’s denial of objectivism convincing, this will

inevitably be because we judge it well using our best lights of what

constitutes a good philosophical argument. In the very act of accepting

his argument, we will be taking those standards to justify our rejection of

objectivism. The issue here is stated neatly by Hilary Putnam:

If statements of the form

‘X is true (justified) relative to person P’ are themselves

true or false absolutely, then there is, after all, an absolute notion of truth (or

justi

fication), and not only of truth-for-me . . . [Otherwise, one would have to

say] that whether or not X is true relative to P is itself relative. At this point, our grasp

on what the position even means begins to wobble.

10

8

T. M. Scanlon,

‘The John Locke Lectures 2009: Being Realistic About Reasons’,

Lecture IV (online at <www.philosophy.ox.ac.uk/lectures/john_locke_lectures>); Robert

Audi,

‘Moderate Intuitionism and the Epistemology of Moral Judgment’, Ethical Theory and

Moral Practice 1(1) (1998):15

–44.

9

Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (Oxford: Blackwell, 1980), 261.

10

Hilary Putnam, Reason, Truth and History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1981), 121. Putnam argues for a realism which falls short of the metaphysical realism set out

below in (MR1) and (MR2) and defended in Ritchie, Realism, Ideology, Truth.

18

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

My discussion of Rorty led on to a defence of two theses of Metaphysical

Realism:

(MR1) The world exists, and has certain properties, independently of

either human beliefs or conceptual schemes. Indeed, the

world would exist and have properties even if no human

beings existed at all, and

(MR2) A statement is true if and only if it is an adequate representa-

tion of the way the world is, where

‘the world’ is as construed

in (MR1).

11

The argument of this book will assume these theses to be correct. (One

quali

fication ought to be made. In assuming the truth of (MR1) and

(MR2) I am not asserting that

‘the world’ and ‘our conceptual schemes’

can be examined separately and compared. This quali

fication will not be

enough for John McDowell, whose account of the relationship between

mind and world is

‘anti-anti-realist’ rather than metaphysically realist.

However, in Chapter 6, I will argue that this difference between his

position and mine does not materially affect the case being made in this

book. The

‘explanatory gap’ arises for his account also.)

1.3.4 Extent of moral disagreement

I now want to consider the other objection raised at the start of this

chapter

—the (alleged) fact of widespread moral disagreement.

Once again, there is a parallel with the norms of theoretical reasoning.

Widespread and even intractable disagreement does not rule out the

possibility of objective truth. I have already referred to the debates around

the principle of induction. There is ongoing disagreement as to whether

some version of the principle of induction is among the fundamental

norms of theoretical reasoning. Whatever the merits of each side of the

argument, it looks as if there must be a

‘fact of the matter,’ one way or the

other. There are clearly a wide range of philosophical issues on which

ongoing disagreement occurs without localized relativism looking like a

plausible response. What matters is not whether agreement can always be

attained but whether we have ways of proceeding in the argument.

11

Ritchie, Realism, Ideology, Truth, 6.

WHY TAKE MORALITY TO BE OBJECTIVE

?

19

In evaluating the title of moral enquiry to objective truth, widespread

and ongoing disagreement is not a good sign, but it is hardly a decisive

objection.

12

The fact that there is disagreement between intelligent and

sensitive reasoners does not imply a relativistic

‘free-for-all’. In philosoph-

ical disagreements such as the debate around induction, we can distinguish

between rigorous and plausible arguments and mere sets of assertions.

What we have in each of these debates are ways of moving forward in

the argument, but as yet no party has won a decisive victory.

13

In the moral case, agreement goes deeper than is often apparent. Many

of the most oft-cited examples of intractable disagreement relate to the

sanctity of human life. In our own time and place, contested issues include

the permissibility of abortion and euthanasia and the circumstances (if any)

in which wars may be just. If we look to past centuries, and indeed to

different cultures today, there is a lack of agreement on matters such as the

morality of ritual human sacri

fice and the wholesale slaughter of con-

quered communities.

On closer examination, a striking feature of such disagreement, howev-

er serious and impassioned, is that it is usually contained within some

framework of agreement on the value of life. That is to say, the act of

killing another human being requires some justi

fication—perhaps in

denying that the agent in question is fully human (a key tactic in Nazi

propaganda) or claiming that the killing, while regrettable, is justi

fied by a

greater good (a key part of most justi

fications of war) or claiming that God

commanded the killing (a key thought in ritual slaughter or the killings of

other tribes authorized in the Old Testament).

14

Communities recognize

that a justi

fication must be provided for killing other humans, and as they

come to a deeper understanding of one another

’s identity and culture they

generally

find it harder to deny the other’s full humanity. ‘Dehumanizing’

another community usually involves empirical as well as moral falsehoods.

Untruths are circulated about the community

’s habits and allegedly evil

deeds because it is hard for humans who care about doing good to

12

See Enoch,

‘How is Moral Disagreement a Problem for Realism?’, Journal of Ethics 13(1)

(2009): 39ff.

13

See T. M. Scanlon,

‘Moral Theory: Understanding and Disagreement’, Philosophy and

Phenomenological Research 55(2) (1995): 353ff.

14

E.g. in 1 Samuel 15:3.

20

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

recognize the other as human and none the less be willing to harm or kill

them.

15

In short, it seems that a signi

ficant amount of moral disagreement turns

out not to be about fundamental moral principles, but about their appli-

cation in contested cases. The canvas on which these disagreements are

played out has more uniformity than we might initially appreciate. The

most egregious deviations in moral opinion come when individuals and

communities cease to be interested in a genuine search for the good.

There is a further piece of evidence in favour of this analysis of moral

disagreement: a community which wishes to dehumanize another feels the

need to weave together moral untruths with empirical ones. Communities

genuinely interested in understanding their neighbours and their possible

obligations towards them tend (as they discover more about them) to grow

in their belief in that these lives too have a dignity and worth. We need to

remember what the objectivist is committed to asserting. She need not

claim that all agents are motivated by moral considerations but that moral

considerations have a genuine claim on us that is independent of whether

we recognize it. As we shall see in 1.4.6, there is now a well-developed

literature on self-deception, both among individuals and at a communal

level. In so far as moral disagreement comes down to individuals and

communities biasing their moral beliefs in a self-serving fashion, it does

not undermine either the claim that there is an objective moral order or the

epistemological possibility of apprehending it.

1.4 Positive Case for Objectivism

1.4.1 Deliberative indispensability

So far, this chapter has been engaged in ground-clearing

—addressing the

well-worn objections to moral objectivism that fuel the

‘pull of reduc-

tionism

’. My strategy has been to show that the problems which are

alleged to af

flict moral reasoning also affect other areas of knowledge

15

Nothing I say here is intended to take a position either way on the arguments which

rage between thinkers who believe in a

‘moral law’ evident to all reasonable agents and those

who believe in more tradition-based modes of enquiry. My own argument is clearly

compatible with the former view

—and it is also compatible with the latter, provided that

(i) there are some signi

ficant moral commitments which all rationally defensible traditions

accept, and (ii) there is some possibility of rational engagement across traditions.

WHY TAKE MORALITY TO BE OBJECTIVE

?

21

where objectivism is widely accepted. The epistemological and ontologi-

cal issues which arise with respect to practical reasoning (of which moral

reasoning is a subset) arise also for theoretical reasoning.

In making a positive case for objectivism, I will continue to draw

parallels between theoretical and practical reasoning

—arguing that, just

as objective norms of theoretical reasoning are deliberatively indispensable, so

are moral norms with at least some degree of objectivity. My argument for

the deliberative indispensability of (to some degree) objective moral norms

draws upon, and modi

fies, the case made by David Enoch. As we have

seen, Enoch claims that there are a number of practices in which all human

reasoners engage. In each case, while scepticism is theoretically possible,

there is no credible suggestion that humans should actually abandon these

practices. I have already explained why (following Enoch) I take the

principles of IBE to be deliberatively indispensable. Scepticism about

IBE is theoretically possible, but its practical price would be abandonment

of any human ambition to understand the world around us.

1.4.2 Deliberative indispensability and practical reasoning

Just as IBE is indispensable to our attempts to understand the world around

us, Enoch argues objectivity about the norms of practical reasoning is

indispensable to our practical deliberation. As Enoch observes, when we

deliberate on what we should do, we seem to be trying to

find something

out, not simply expressing a preference or taste:

It is worth noting how similar the phenomenology of deliberation is to that of

trying to

find an answer to a straightforwardly factual question: When trying to

find an answer to a straightforwardly factual question (like what the difference is

between the average income of a lawyer and a philosopher) you try to get things

right, to come up with the answer that is

—independently of your settling on it—

the right one. When deliberating, you also try to get things right, to decide as

—

independently of how you end up deciding

—it makes most sense for you to

decide.

16

Of course, from the mere feel of our deliberation, relatively little follows.

We also deliberate over whether an action is

‘polite’, and can argue about

whether a joke is

‘funny’. This does not mean that there is anything more

than a locally objective standard of etiquette or humour.

17

We do not

16

Enoch,

‘How is Moral Disagreement a Problem for Realism?’, 34, 37.

17

Cf. Philippa Foot,

‘Morality as a System of Hypothetical Imperatives,’ repr. in her

Virtues and Vices (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

22

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

suppose that other cultures get something wrong if their rules of etiquette

are different from ours. Nor do we suppose it makes sense for an agent to

say a joke is unfunny if everyone in the world laughs at it (unless, perhaps,

he means that he disapproves of everyone

finding it funny, and thinks they

ought not to laugh).

What people

find funny is constitutive of what is funny. In conse-

quence, while we can imagine an academic research project into

‘Why

people

find certain things funny’, a Philosophy D.Phil. on ‘What things

are truly funny

’ would itself be a rather poor joke.

Where standards are clearly culturally relative, two kinds of deliberation

are possible. Firstly, agents can deliberate about what people will take to be

polite or amusing. (Trying to

‘strike the right note’ in a speech involves

seeking to understand the communal standards of etiquette and humour.)

Secondly, agents can deliberate on the stance they will take towards these

communal standards. Perhaps our speaker thinks the standards should be

revised. She may think that contemporary attitudes to humour are unduly

conservative, or that certain forms of etiquette exist only to perpetuate

social inequality. Alternatively, her rejection may be less principled; for

example, she may simply fail to see why she should bother to be good

mannered.

What is an agent doing when she deliberates about the attitude she

should take to such communal standards? She may be trying to work out

what her all-things-considered desires are, and what stance will best ful

fil

them. In a society which disapproved of divorce, an agent might deliberate

over whether to divorce her spouse without any reference to objective

norms. She would have to consider what made her contented and unhappy

within the marriage, about how those around her would react to the

instigation of divorce proceedings, and about her likely happiness at the

end of the process. We can see why this kind of deliberation has a

phenomenological af

finity with explanatory theorizing. They are both

trying to get to a fact of the matter. In the case of practical reasoning,

Enoch and I have yet to show that this

‘fact of the matter’ need involve

something independent of an agent

’s desires or social conventions. That is

the question to which I will now turn.

1.4.3 Deliberative indispensability and objective practical norms

Are there certain considerations which should bear on me, whatever I do or

do not happen to desire? If so, is one purpose of our deliberation to weigh

these considerations correctly? Enoch answers

‘yes’ to both questions:

WHY TAKE MORALITY TO BE OBJECTIVE

?

23

[W]hen you allow yourself to settle a deliberation by reference to a desire, you

commit yourself to the normative judgment that your desire made the relevant

action the one it makes most sense to perform. So even with desires at hand, you

still commit yourself to a normative truth.

18

Enoch is claiming the following: If after deliberation I take a course of

action because I desire that outcome, I am committed to the judgement

that the desire has made the action the one it makes most sense to perform.

I think this claim is excessive. In this section, I will explain why, before

advancing my own (less extreme) version of the argument.

To evaluate Enoch

’s claim, let us consider this example: I am deliberat-

ing over whether to meet someone I

find rather tiresome, on the

grounds that I have promised to do so, or whether to stay at home, on

the grounds that I would prefer this. If I decide to stay at home, am I really

committed to the view that it would have made less sense to go and meet

the person in question? Intuitively, it seems more plausible to say that I can

continue to agonize and debate about what to do, even once I am clear

about which course of action is morally the best. In eventually settling

upon a morally inferior choice, it is not obvious that I am committing

myself to the view that there is any kind of wider truth of practical reason

to the effect that staying at home and doing what I want is

‘the action . . . it

makes most sense to perform

’ (as if the moral ‘ought’ were outweighed by

other considerations in a wider,

‘all-things-considered ought’).

The relationship between deliberation and action in such cases is com-

plex and contested. Enoch

’s account seems to imply a highly rationalistic

view of this

—the kind of position taken by Socrates, and defended by

R. M. Hare in the opening sections of The Language of Morals. Hare argues

that we do not simply look at what someone says in order to work out

what they believe:

If we were to ask of a person

‘What are his moral principles?’ the way in which we

could be most sure of a true answer would be by studying what he did

. . . . [it is

when] faced with choices or decisions between alternative courses of action,

between alternative answers to the question

‘What shall I do?’, that he would

reveal in what principles of conduct he really believed.

19

18

Enoch,

‘How is Moral Disagreement a Problem for Realism?’, 37–8.

19

R. M. Hare, The Language of Morals (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952), 1.

24

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

One might think this account fails to capture the nuances of what goes on

in situations of akrasia (weakness of the will). It seems plausible to say that

we do sometimes deliberate over whether to act morally, without com-

mitting ourselves to the view that there is a

‘fact of the matter’ about

whether we ought, all-things-considered to act morally.

We do not need to come to a conclusion on this issue in order to move

forward in the wider discussion. As I will show below, Enoch

’s overall

conclusion (about the deliberative indispensability of normative realism)

can be defended even if we accept a claim about practical deliberation

weaker than the one he has made. All that we need claim is that, in so far as

an agent

’s action is the product of a practical deliberation, she judges the

action to make sense. If after deliberation she knowingly chooses the

morally wrong action, it must make sense in some other way (perhaps

because it generates pleasure or protects one of her fundamental interests).

It does not, however, need to make more sense than any other alternative.

The crucial question, then, is whether an agent need accept that there

are any objective moral reasons for action. If practical deliberation is

sometimes simply a matter of determining what my all-things-considered

desires are, or what social convention demands, why could it not always be

restricted to these kinds of fact? Why also postulate objective moral facts?

When an agent deliberates about the stance she will take towards a rule

of etiquette, or whether to instigate a divorce, she will not only ask

whether her actions will offend or please others. She will also ask whether

their responses are justi

fied. This question of justification is even more

central when we come to deliberate upon our own desires. It is pretty

implausible to claim that the only thing I ever do when re

flecting on my

desires is to discern my own all-things-considered desire. My deliberation

also involves considering whether my desires are excessively self-centred

or shallow, and how they ought to be weighed against the desires and

needs of others. It looks as if I am trying to get something right, and trying

to revise my desires in the light of the fact of the matter about what is or is

not right.

If this line of thought is correct, it still does not commit us to Enoch

’s

more extreme thesis

—that when I decide to act on my desires, I commit

myself to a normative truth. As I have observed, agents do not only

deliberate about what is the right thing to do. They also deliberate about

whether to do the right thing. Moral decision-making seems to include

both cases where we are solely concerned to work out what is the right

WHY TAKE MORALITY TO BE OBJECTIVE

?

25

thing to do and cases where we are concerned as to whether to do the right

thing. The latter case cannot be straightforwardly factual. If I choose

to do the wrong thing I do not seem committed to claim that, had

I chosen to do the right thing, I would have made a mistake (by ignoring

an overriding reason for action).

I conclude from this that we can sometimes deliberate without thinking

we are trying to get to a fact of the matter. However, it is impossible to

make sense of much of the deliberation all re

flective human beings

regularly engage in, whatever their philosophical persuasion, without

taking there to be some further standard by which they judge both their

desires and the attitudes of their wider culture. It is not clear how the non-

objectivist is to account for the prima facie independence of this standard.

On the other hand, even if we grant that there are reasons for agents to

act whose truth is independent of the their desires or opinions, it is not

obvious that any of this will lead to moral objectivism. One might accept

that there are objective norms of practical reasoning but deny that any of

these norms are, in the last analysis, moral. Moral objectivism is a stronger

claim, and one I will defend in the section which follows.

1.4.4 Objectivity of moral norms

In this book, I will be using

‘moral’ with a rather broader scope than some

philosophers. I will use the word to refer to all the reasons for action that

flow from the existence of objective value or obligation.

20

In conse-

quence, when I claim that there are

‘objective moral norms’ all I mean is

that there is a fact of the matter about how one human being ought to

behave towards others (or how he

‘has reason’ to behave towards them),

and that the content of these obligations (reasons) is not wholly prudential.

That is to say, we have reasons for, and obligations to, care about one

another which do not

flow from the benefit that care will ultimately give

to us.

When

‘morality’ is defined in this broad sense, it seems fairly clear that

the deliberation all re

flective agents engage in makes use of moral, as well

as more generally practical, norms. Abandoning the belief that these

standards are objective would have a huge impact on our deliberative

practices. This impact is signi

ficantly underplayed by Mackie in his defence

20

Thus, in so far as aesthetic values provide reasons for action, these reasons would also

count as

‘moral’.

26

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

of an error theory. Mackie seeks to construct a

firewall between one’s

meta-ethics and both the content of

first-order moral judgements and the

intensity with which they are held.

21

This seems implausible: if, in the

final

analysis, we view our moral judgements simply as expressions of our

sentiments and preferences, or the conventions of our culture, rather

than an articulation of an absolute claim made upon us by the moral

order, this cannot but affect our

first-order attitudes.

Ronald Dworkin makes this point with characteristic force:

If someone says that soccer is a

‘bad’ or ‘worthless’ game, for example, he may well

concede on re

flection, that his distaste for soccer is entirely ‘subjective’—that he

doesn

’t regard that game as in any ‘objective’ sense less worthwhile than the game

he prefers to watch. Though he has a reason for not watching soccer, he might say,

no one whose tastes are different has the same reason.

So when I say that the badness of abortion is objective

. . . it would be natural to

understand me as explaining that I do not regard my views about abortion in the

same way

. . . The claim that abortion is objectively wrong seems equivalent, that is,

in ordinary discourse, to

. . . [the claim] that abortion would still be wrong even if

no one thought it was

. . . I mean that abortion is just plain wrong, not wrong only

because people think it is.

22

The cost of an error theory of morality is that it collapses these two kinds of

‘badness’ into one. In consequence, we can make no sense of that aspect of

our deliberation which relates to whether actions are justi

fied. In Dwor-

kin

’s example, the person who says soccer is ‘worthless’ is merely referring

to his all-things-considered desire. For such a person, a game of soccer

would have no worth. By contrast, the person who says abortion is

‘bad’ is

making a claim about what actions there are objective reasons to perform

or desist from, and our deliberation on these matters does not simply

concern our all-things-considered desires.

Of course, none of this proves that our pre-philosophical practices are

justi

fied. What it does show is that the consequences of adopting an error

theory are far deeper than Mackie has allowed. As Dworkin argues,

adopting such a theory will undermine our ability to claim anything at

all is

‘just plain wrong, not wrong because people think it is’.

21

Mackie, Ethics, ch. 5.

22

Ronald Dworkin,

‘Objectivity and Truth: You’d Better Believe It’, Philosophy and

Public Affairs 25(2) (1996): 98.

WHY TAKE MORALITY TO BE OBJECTIVE

?

27

There are of course arguments from within our normative discourse in

favour of scepticism about particular judgements. Many people are scepti-

cal about whether sexual acts are intrinsically good or bad, and see consent

and harm as the only criterion for value judgements.

23

Likewise, some

people object to attempts by one culture to impose its values on another.

24

In both cases, one set of normative judgements (

‘acts between consenting

adults are only wrong if someone is harmed

’ and ‘it is wrong for one

culture to impose its values on another

’) is used to deny the validity of

another (

‘homosexuals are intrinsically disordered’ and ‘the values of

western society ought to be imposed on other cultures

’). Local scepticism

flows from specific worries about the reliability of a moral judgement, and

assumes a backdrop of generally truth-tracking moral faculties. I judge this

attitude (be it disapproval of homosexuality or be it

‘cultural imperialism’)

to be a product of an erroneous social conditioning which has distorted my

view of the moral truth. But such a judgement relies on my capacities for

discerning moral truth to be, more generally, truth-tracking. Local scepti-

cisms rely on a backdrop which is non-sceptical.

It would be a natural, and I think correct, extension of Dworkin

’s

argument to say that a view which denies there are any reasons for action

grounded in the needs of others rather than our own preferences is one we

ought not to hold. The problem with grounding of morality in non-moral

reasons

—as Mackie’s error theory must—is that it is morally, rather than

meta-ethically, wrong. There is no non-circular justi

fication at this point:

we have reached bedrock.

That one cannot argue someone into our most fundamental moral

commitments does not undermine them, any more than our commitment

to the principles of Inference to the Best Explanation would be under-

mined by us encountering a sceptic who failed to see why anything

needed to be explained at all. In the moral case, as Raymond Gaita

observes:

The fact that blackboards can be

filled with what are called sceptical arguments is

what sustains the illusion that it is a serious intellectual option. If anyone seriously

asserted them in his own name we would judge him to be wicked and we would

23

E.g. Scanlon,

‘Moral Theory’, 352.

24

The tensions within such a view are discussed in Will Kymlicka, Multicultural Odysseys:

Navigating the New International Politics of Diversity (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 6f.

28

FROM MORALITY TO METAPHYSICS

believe his wickedness to be the reason such arguments carried any weight with

him.

25

Gaita argues that certain views ought to be

‘unthinkable’—that there is

something morally wrong with needing a justi

fication for the most funda-

mental of our ethical commitments. In applying this argument to this

discussion of Mackie, I am not impugning the morality of Mackie or his

fellow reductionists. Indeed, is their very loyalty to our shared and funda-

mental moral commitments that stops them pushing their meta-ethical

arguments to their logical conclusion. Mackie very much wants to avoid

first-order conclusions which are ‘unthinkable’ and ‘beyond consider-

ation

’. This is why a large proportion of Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong

is devoted to an attempt to show that a reductionist meta-ethics has

positive and progressive

first-order consequences.

26

For the reasons

given in this chapter, I think he fails.

The signi

ficance of Gaita’s observation is that it defuses one potential line

of response to this failure. We do not need to give credence to the response

that it is our

first-order practice (rather than the meta-ethics) which needs

to change. There is some evidence that Mackie would (at some level at

least) agree, for as we have seen, he tries very hard to downplay the negative

impact of his meta-ethics on our

first-order practice.

In the sections which follow, I will press home this critique of the error

theory, by arguing that it cannot escape a nihilistic view of humans

’ dignity

and value, and also that such nihilism has a human cost. The error theory

deprives us of the motivation for emancipatory changes in our moral

outlook, and also of one of the principal bulwarks against oppression.

The Oxford

finalists cited in the introduction to this book were not so

remiss in recalling Hitler half-way through their examination answers.

I will argue that a more consistent mindfulness of the evils of Nazi

Germany should make us wary of the

‘illusion’ that any moral scepticism

is a

‘serious intellectual option’.

1.4.5 Nihilism of error theory

I will make the case for the inherent nihilism of the error theory by way of

a thought-example. It is borrowed from Roger Crisp

’s defence of (what I,

25

Raymond Gaita, Good and Evil: An Absolute Conception (London: Routledge, 2004),

316.

26

Mackie, Ethics, Parts II and III.

WHY TAKE MORALITY TO BE OBJECTIVE

?

29

though not he, would term) moral objectivism in Reasons and the Good.

(Crisp

’s position is objectivist about practical norms, but not about what he

terms

‘morality’. But on the wider definition of morality given above,

where all

‘reasons for action that flow from the existence of objective value

or obligation

’ count as ‘moral’ reasons, Crisp is an objectivist. For he is a

hedonist who holds that pleasure and the avoidance of pain are the sole

bearers of objective value.