Does corpus linguistics exist? Some old and new issues

Jan Aarts

University of Nijmegen

Abstract

This paper deals with a number of methodological questions in corpus linguistics. It

discusses various kinds of linguistic data and examines the nature and use of corpus data

and the function of corpus annotation. These topics are put within the context of two recent

issues in corpus linguistics: the new evidence that has become available from spoken

corpora such as COLT and the spoken part of the BNC, and the renewed discussion of

corpus linguistic methodology, notably about the distinction between the corpus-based and

the corpus-driven approaches.

1.

Introduction

It is difficult to attach a date to the birth of corpus linguistics, but if we take it to

mean computer corpus linguistics (see Leech 1992) we can locate its origin early

in the 1960s, at the time when the computerization of the the Brown Corpus was

finished. For about a decade and a half the use of corpora belonged very much to

the linguistic underground, and the term ‘corpus linguistics’ did not come into use

until it began to gain some respectability in the late seventies or early

eighties.Today it is taken seriously by the majority of linguists. Not by all of them

– Chomsky’s position, for example, is still as negative as it was in the sixties:

[Corpus linguistics] doesn’t exist. If you have nothing, or if you are stuck, or if

you’re worried about Gothic, then you have no choice. (Chomsky in an interview

with Bas Aarts; Aarts 2000: 5)

Other theoretical linguists take a less diehard view. Fillmore recently

described his position with respect to the use of corpora as follows:

My peace-making position [in Fillmore 1992 – JA] was that one

couldn’t succeed in the language business without using both

resources: any corpus offers riches that introspecting linguists will

never come upon if left to their meditations; and at the same time,

every native speaker has solid knowledge about facts of their

language that no amount of corpus evidence, taken by itself, could

support or contradict. (Fillmore 2001: 1)

That feelings about this issue can still run high became apparent in a recent

discussion on the corpora list, where (after almost 40 years!) we could renew the

2

Jan Aarts

acquaintance with some arguments we hadn’t seen come by for some time. In

many such discussions it is not clear what exactly is at issue, however. Is it a

discussion about the question which data sources are the most appropriate for

linguistic research? Is it a clash between different methodologies? Or is it –

perhaps more basically – a disagreement about what should the object of

linguistic study? More generally, such issues come down to the question: what

kind of linguistic discipline is corpus linguistics? Is it a linguistic discipline in its

own right? Or, to borrow Chomsky’s provocative words: does corpus linguistics

exist?

1

In this paper I want to deal with such questions by looking at two

important things going on in corpus linguistics at the moment. First, there appears

to be a new focus on spoken language – this is beginning to receive the same sort

of attention that the written language has received so far. Notably there is a

widening of the attention given to the spoken language so as to also include its

syntax and to contrast this with the syntax of the written language. This new

attention showed itself, for example, in Miller and Weinert’s book Spontaneous

Spoken Language: Syntax and Discourse (1998). On the basis of corpus material

from English, German and Russian, they analyse the differences between the

syntax and discourse of spontaneous speech and written language, claiming that

the differences are such that they have far-reaching consequences for theory-

oriented linguistic research. In 1999 another book appeared that bears the stamp

of a new focus on the spoken language: the Longman Grammar of Spoken and

Written English (Biber et al.). And finally, an important new resource for the

research into spoken English became available in 2000, namely Anna-Brita

Stenström’s Corpus of London Teenage Language (COLT). Containing the

spontaneous speech of a young generation of native speakers, it is bound to put its

stamp on the research of spoken English in the near future; it has already

generated a considerable list of publications.

2

A second important recent development is a renewed interest in and

discussion of questions of methodology. I have already mentioned the recent

dicussion on the corpora list, which centred on the old question of intuitive data

vs. corpus data. The issue returned at the 2001 ICAME conference, notably in the

keynote lecture by Fillmore, entitled ‘Armchair linguistics vs. corpus linguistics

revisited’ (Fillmore 2001), a title which echoed his earlier paper delivered ten

years previously at the Stockholm Nobel Symposium on corpus linguistics

(Fillmore 1992). At the same conference another contribution on methodology

was made by Tognini-Bonelli. This was only sideways related to the intuitive vs.

corpus data debate, but more concerned with methodological matters that arise

once the linguist has chosen for the use of corpus data. It thus raises an issue that

is internal to corpus linguistics and therefore probably more important for the

discipline. It is concerned with the question how dominant a status should be

assigned to the data in corpus linguistic research. Putting this differently, the

question is not what data the linguist thinks it is appropriate to use, but what he

Does corpus linguistics exist? Some old and new issues

3

should do with them. In this connection Tognini-Bonelli distinguishes the corpus-

based approach and the corpus-driven approach. She describes the two as

follows:

... corpus-based work relates corpus data to existing descriptive

categories adding a probabilistic extension to theoretical parameters

which are already received, i.e. established without reference to

corpus evidence. On the other hand, corpus-driven work attempts to

define the categories of description step by step, in the presence of

specific evidence from the corpus. (Tognini-Bonelli 2001b: 99)

Whether a researcher will prefer a corpus-based or a corpus-driven approach

depends on the answers he will give to a number of basic questions: 1. what

kind of evidence does he think corpus data provide? 2. does he want to leave

room for other than corpus data? 3. what should be the role played by

previous linguistic research that was not based on corpus data? As said, these

are basic questions and a discussion of them and of the corpus-based vs.

corpus-driven distinction is called for. In what follows I shall look more

closely at the two issues mentioned; I’ll start with the methodological

question and after that discuss the new research into the spoken language in

relation to it. At the end we return briefly to the question posed in the title.

2.

Methodology

Any discussion of corpus linguistic methodology must start from the data – after

all the discipline bears the name of a linguistic data source and in its present form

arose as a challenge to the preference of the linguistic mainstream for intuitive

data. In this section we first look at the different kinds of data that linguists have

used and are using. After that we discuss the different ways in which linguists use

corpus data in their research. In the last sub-section we examine the role of

annotation in corpus linguistic research.

2.1

Types of linguistic data

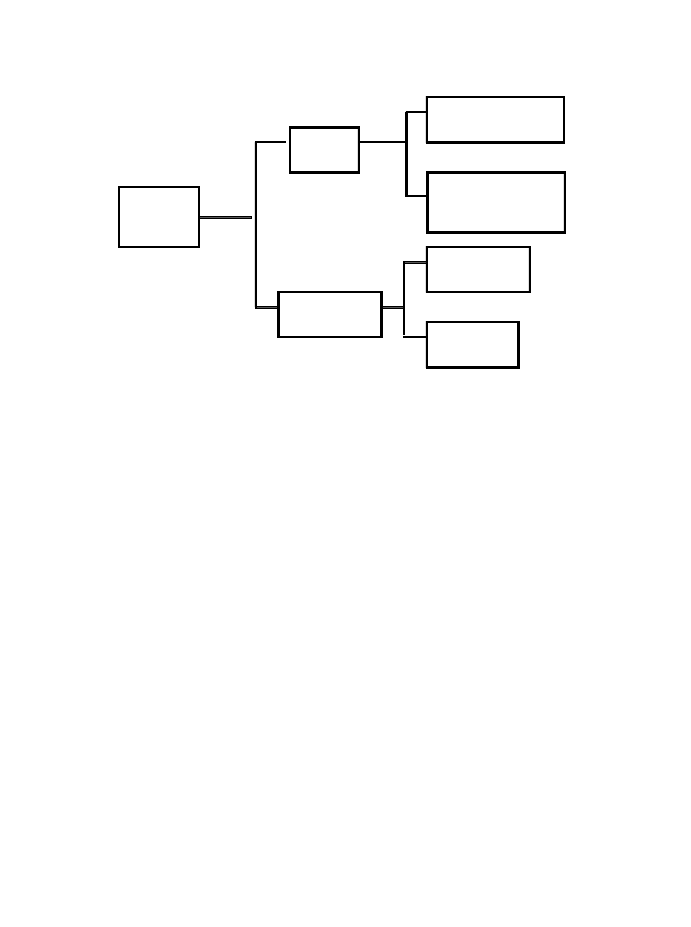

A survey of the different kinds of linguistic data is presented in Figure 1

(reproduced from J. Aarts 2000). The major distinction is between intuitive and

non-intuitive data. In the practice of linguistic research it is still more or less

tacitly assumed that intuitive data provide direct access to a speaker’s intuitive

knowledge of the language, that is, to some sort of internalized rule system, but

this has been shown not to be the case; instead, intuitive data appear to reflect

what a speaker believes to be true of language behaviour in concrete situations

(see, for example, Snow and Meyer 1977; Nagata 1989; Shohamy 1996).

4

Jan Aarts

Figure 1. Types of linguistic data

Introspective data were the favourite type of intuitive data during some decades in

the previous century; it was usual for the linguist to consult his own intuitions

about the language. It has been pointed out repeatedly that such data are

unreliable: they are subjective and unverifiable and there is confusion of the two

roles the linguist plays – that of native speaker and that of linguistic researcher.

Some of these drawbacks can be overcome by collecting informant data: the

linguist does not consult his own intuitions, but those of others. The collection of

informant data is a difficult and time-consuming job (see, for example, Quirk and

Svartvik 1966; de Mönnink 2000). As a consequence, informant data have not

been used very frequently nor very extensively.

Non-intuitive data are provided by what people actually say and write. The

material has to be on record in some form or other to serve as workable data for

linguistic research; this is always the case with written and printed material. It is

not surprising, therefore, that until quite recently, if it was claimed that linguistic

studies were based on ‘authentic material’, this was usually written material. The

distinction that is made in Figure 1 between anecdotal and corpus data has not to

do with the type of data involved, but with the manner of collecting them. Briefly

put, anecdotal data are collected unsystematically, while corpus data are compiled

systematically. Most of the standard reference grammars of English of the first

half of the previous century contain anecdotal data. They were collected in a

haphazard way: whenever the grammarian happened to read something that

caught his attention, he made a record of it. Thus, Jespersen (pt II, 1914: vi) talks

about ‘my quotations, which I have collected during many years of both

systematic and desultory reading’ and Poutsma (pt I, 2nd ed., 1928: vii) says:

anecdotal data

corpus data

other native

speakers:

informant data

linguistic

introspection

non-intuitive

intuitive

linguistic

data

Does corpus linguistics exist? Some old and new issues

5

[My] quotations have partly been borrowed from dictionaries and from

other grammars. But by far the majority of them have been collected by

myself from numberless and varied sources: not only literary and scientific

books, but also periodicals and newspapers.

Other twentieth-century grammarians have said similar things (see, for example,

Schibsbye 1965: v).

3

Anecdotal data are inferior to corpus data in two respects. In the first

place, the grammarian will only collect examples that ‘catch his attention’ and is

not interested in what he expects to find. Jespersen said that, whenever he could,

he selected sentences that were in some way ‘striking’ (ibid.). For this reason

anecdotal data are not only necessarily skewed, but the subjective element

involved in their collection is not recoverable. Another, more important,

drawback of anecdotal data is that they become isolated from both their micro-

and macro-context; that is to say, they are deprived of their immediate verbal

context and the contextual features that are relevant for their specific form, and

become separated from their larger sociolinguistic context, including genre,

register, style, domain, etc. As said above, anecdotal data provide, next to

intuitive data, the material for most of the twentieth century reference and other

grammars. Sometimes the emphasis is on intuitive data, as is the case in Sweet’s

grammar where we find hardly any authentic data – practically all the examples

he gives to illustrate points of syntax are made-up sentences. Other grammarians

use anecdotal data exclusively (Jespersen, Kruisinga) or predominantly

(Poutsma). In view of the fact that both intuitive data and anecdotal data have a

good deal of subjective colouring, it is perhaps at first sight a bit surprising that

their descriptions of the English language are so homogeneous. This can partly be

explained from the fact that most grammarians relied, of course, to a greater or

lesser extent on previously written grammars. Reading the prefaces of the

grammars one can see for example that Jespersen, Poutsma, Zandvoort and

Strang express their indebtedness to Sweet, while Sweet, Poutsma, Zandvoort,

Strang and Schibsbye say that they are (also) specially indebted to Jespersen –

and this chain of interdependence between grammars can be traced throughout

the century. Another factor is that the variety of English they describe is very

homogeneous: on the whole, not only do they concentrate on British English and

on educated standard language, but they are predominantly concerned with the

written language and with general language about non-specialized subjects.

In most twentieth-century grammars the relation between the description

and the data is not clear. When grammarians use authentic material they usually

regard this as a source to choose their examples from; with the exception of Fries

(1952), they do not treat their material as a data collection that has to be

accounted for. In this connection it is typical that Jespersen and Poutsma speak of

their ‘quotations’ (see above). Even in A Grammar of Contemporary English and

A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language, which we know to be

6

Jan Aarts

closely related to corpus data, the relation between data and description is not

clear, owing to the fact that the writers decided to ‘refrain from citing actual

utterances with references to sources. Most of our examples are either simplified

versions of actual utterances or invented’ (Greenbaum 1988: 46). I return to the

question of the relationship between description and corpus data below.

2.2

Corpus data: Their nature

The most important difference between corpus data and other kinds of linguistic

data is that in the former case their provenance is known: they are found in the

natural environment of the verbal context, we know in which medium they occur,

to what linguistic or extra-linguistic textual category, what (type of) language

user produced them, and so on. In other words, corpus data reflect the way in

which language is actually used. Now, language use is what most descriptive

grammars profess to want to give an account of. At the same time it must be said

that there is a not inconsiderable number of utterances that one comes across in

corpora but will look in vain for in descriptive grammars of language use. Among

them are broken-off sentences, false starts, repetitions of phonemes, morphemes,

words and (parts of) larger constituents, anacolutha, stretches of text from other

languages or from sub-standard varieties, as well as utterances that the speaker or

writer intended to be ungrammatical; in short, corpora contain among other things

evidence of ‘such grammatically irrelevant conditions as memory limitations,

distractions, shifts of attention and interest and errors ...’ Chomsky 1965: 3). In

other words, what one finds in a corpus is ‘performance’, that is, evidence of

linguistic behaviour. And linguistic behaviour is not only determined by

linguistically relevant, but also by linguistically irrelevant conditions.

Linguistically relevant are all aspects of the verbal context (or ‘micro-context’)

and all the parameters imposed by the sociolinguistic setting (the ‘macro-

context’). It seems reasonable, therefore, to say that a descriptive grammar should

give an account of the system of rules underlying language use together with the

linguistically relevant parameters that determine the form of utterances in their

context. It is of course not at all an easy matter to decide what, in a corpus, is

linguistically relevant and what not. Various terms and notions have been

proposed for the assessment of linguistic relevancy, all of which make an appeal

to some sort of consensus among native speakers, sometimes supported by a

criterion of frequency. Of these, the first was ‘acceptability’ defined by Chomsky

(1965: 11) as the quality of ‘utterances that are perfectly natural and immediately

comprehensible ... and in no way bizarre or outlandish’. Quirk and Svartvik

(1966) tried to operationalize the notion of acceptability, adding a quantitative

dimension. Widdowson (1991) introduces the concept of ‘feasibility’ as a filter

for corpus data; excluded are those data that do not meet a criterion of normality.

Finally, in an earlier article (Aarts 1991) I suggested using the notion of

‘currency’, which is compounded of the frequency of occurrence of a

construction and its ‘normalcy’ which is a qualitative and intuitive notion, closely

Does corpus linguistics exist? Some old and new issues

7

resembling Widdowson’s ‘normality’. All in all, it is likely that there is a

consensus among corpus linguists that not every construct, by virtue of its

appearance in a corpus, has to be taken into account in a description of the corpus

language, but that every corpus will contain constructs that can be excluded on

the basis of their not meeting an intuitive criterion of naturalness or normalcy.

4

2.3

Corpus data: Their use

I started this paper with two quotations from theoretical linguists to illustrate their

attitude to corpus data. However different in tone they may be, they both illustrate

the same basic attitude towards corpus data: corpus data are supplementary with

respect to intuitive data. As such they may be held in low esteem, as Chomsky

does when he says that they are only relevant ‘if you are stuck’, or highly valued

as Fillmore does, but there can be no doubt about the primacy of intuitive data,

for these rest, as Fillmore (see above) puts it, on the ‘solid knowledge [of every

native speaker] about facts of their language that no amount of corpus evidence,

taken by itself, could support or contradict’. In other words, in the view of both

linguists the corpus is used to jog the linguist’s intuition.

Other linguists assign a more important role to corpus data. They see the

corpus not as a supplementary, but as an indispensable tool for the research into

language use. There are two purposes for which corpus data can be exploited that

could not possibly be achieved by using another kind of data. The first of these is

the examination of language variety – the only way to reveal similarities and

differences between language varieties is to make a comparative study of the

frequency and distribution of linguistic phenomena in corpora representing these

different varieties. So far, this has probably been the most extensive use to which

corpus data have been put; it has been the subject of many individual studies and

this strand of research has come to fruition for the first time in a reference

grammar of English (Biber et al. 1999).

The second research activity for which corpora are indispensable is their

use as a test bed for linguistic hypotheses about the language. What can be tested

is primarily the knowledge accumulated in the literature about one or more

aspects of the language or the ‘complete’ descriptions of the grammar of the

language laid down in reference grammars. In order to test a hypothesis

consistently and exhaustively on corpus data a formal grammar is needed that can

be translated into a computer program which analyses the corpus utterances in the

way specified in the formal grammar. The formal grammar should be a

transparent linguistic tool, the computer program an efficient parser. Testing the

linguistic hypotheses by analysing a corpus will involve of course a test of their

correctness, but what is at least as important is a test of their completeness – does

the formal grammar have sufficient coverage to account for the corpus data? This

is especially important if it is a ‘complete’ grammar that is tested, for in that case

the starting point for the formal grammar is – apart from the linguist’s intuitions –

the knowledge accumulated in reference grammars. And because the description

8

Jan Aarts

found in reference grammars is largely limited to the written language; the

syntactic canon provided by them is therefore bound to contain gaps in the

description.

As said, for the two research activities mentioned above – varieties

differentiation and hypothesis testing – corpora constitute an essential data

source. Both start from the knowledge accumulated in previous research, the

former using it as a basis for the comparative study of language varieties, the

latter testing it for its correctness and completeness. This implies that both

research activities are representative of what Tognini-Bonelli calls the ‘corpus-

based approach’ in the quotation given in the introductory section of this paper.

As early as 1985 Sinclair rejected this approach, saying that:

The categories and methods we use to describe English are not

appropriate to the new material We shall need to overhaul our

descriptive systems. (Sinclair 1985: 252)

In other words, in the face of ‘the new material’ it is no longer possible to

maintain the framework of description built up in the tradition of the English

grammars of the twentieth century. Instead, a ‘corpus-driven approach’ is called

for which emphasizes

... the strict interconnection between an item and its environment ...

[which] leads the corpus-driven linguist to postulate an ‘extended unit

of meaning’ bringing together the lexical, the grammatical, the

semantic and the pragmatic levels. (Tognini-Bonelli 2001a: 11)

This extended notion of meaning is also referred to as a new ‘unit of currency’ for

linguistic description. The corpus-driven approach can therefore be looked upon

as an operationalization of Firth’s ideas about the essential role of context in

linguistic description and his conception of meaning, ideas which also prompted

Quirk’s principle of ‘total accountability’ (Quirk 1968: chapter 7). Needless to

say, in the corpus-driven approach the status of what I have called ‘the

accumulated knowledge about the language’ is called into question.

What is the status of intuitive data in the corpus-based and corpus-driven

approaches? Within the corpus-based approach their status is comparatively clear;

few ‘corpus-based linguists’ will hold that just because something occurs in a

corpus it has to be accounted for in a description of language use. Instead, most

will use a quality of ‘acceptability’ or ‘currency’ or ‘feasibility’ or ‘naturalness’

of utterances as a filter to ‘clean the data’. And the decision whether or not to

assign this quality to an utterance is largely intuition-based. Ultimately, therefore,

a ‘corpus-based linguist’ allows his intuition to overrule his corpus data and

hence gives primacy to the former.

Does corpus linguistics exist? Some old and new issues

9

One would expect an opposite view in the corpus-driven approach, but the

position taken by Tognini-Bonelli is a bit ambiguous. Although she first asserts

that corpus evidence

... casts serious doubts on the role of intuition and introspection,

consistently proven to be unreliable when it comes to representing

exactly how language is really used ... (Tognini-Bonelli 2001a: 91).

she continues in the same passage:

Intuition will still be considered an essential input; it will play a big

part, for instance, in selecting the phenomenon that the linguist will

choose to investigate, and ultimately it will have an important role

when it comes to evaluating the evidence in the corpus. (ibid.)

Two kinds of intuition might be involved here: the intuition the linguist has as a

researcher and his intuition as a native speaker. He will be using the former type

of intuition when he selects the phenomenon to be investigated. It is not quite

clear what is meant by ‘evaluating the evidence in the corpus’. The phrase might

apply to what I called above ‘cleaning the data’, in which case native speaker

intuition seems to be implied, but it may also refer to the researcher’s judgement

as to whether and how new corpus evidence fits in with his previous findings.

Summing up, I think we can say that each of the three attitudes to corpus data

distinguished above leaves room for intuitive data although certainly not to the

same degree.

2.4

The annotation of corpus data

A few words should be said about the annotation of corpus data. I restrict myself

to the annotation for the purposes of linguistic research.

After what has been said above about the corpus-driven approach, it is not

surprising that it rejects annotation. It is argued that the annotation imposes a pre-

existing theory on the corpus data and that therefore it ‘will ensure that the data

will finally fit the theory’ (Tognini-Bonelli 2001a: 73). Another argument that is

put forward against annotation is that it results in a ‘loss’ or a ‘reduction’ of

information (Sinclair 1992: 385 f.; Tognini-Bonelli 2001a: 73). This argument is

a bit difficult to follow. How can the addition of information to items in a corpus

diminish the information contained in the items it is added to, if the two types of

information are of a different order? For the information contained in, say, the

tags added to the words of a text is information about the descriptive framework

that has generated the tags or, more precisely, about the distribution over the text

of the word classes that are part of the descriptive framework; and this

information is entirely different from that contained in the words of the text.

10

Jan Aarts

In the corpus-based approach, which, among other things, wants to collect

quantitative data about the categories of an existing descriptive grammar, or

wants to test an existing grammar on corpus data, (the process of) annotation is an

indispensable tool. For the collection of quantitative data the result of annotation

is important, while the annotation process is especially relevant for the testing of

a grammar. The grammar has a paradigmatic and a syntagmatic dimension: the

former involves assigning (strings of) items to classes, while the latter specifies

what functional relations can hold between the members of these classes in

context. These two linguistic dimensions nicely correspond with the two

computer programs by means of which annotation is usually carried out: a tagger

and a parser. Now, although annotation is very often not carried beyond the

tagging stage, it will be clear that for the testing of a grammar that claims to give

a ‘complete’ description of general language use an integral annotation requiring

both tagging and parsing will be necessary.

Summing up, it can be said that perhaps the most prominent difference

between the corpus-based and corpus-driven approaches is in their attitude to

annotation; whereas it is an indispensable tool for the corpus-based approach, it is

anathema for linguists subscribing to the corpus-driven approach.

3.

Spoken language research and methodological issues

In the introductory section I mentioned some landmarks that point to a heightened

interest in the spoken language. While considerable attention has been paid to

matters relating to intonation and discourse ever since the London-Lund corpus

became available, there is now a shift, or perhaps rather an extension, of interest

to the syntactic structure of spoken language, which may have received its

impetus from the availability of new resources such as COLT and the spoken part

of the BNC. I mentioned two recent books that are representative of the two

strands of corpus-based linguistics I distinguished in Section 2.3: Biber et al.

(1999) and Miller and Weinert (1998). The former extends the scope of a

syntactic description of general English to also include a characterization of

language varieties in terms of the frequency and distribution of structures, and in

doing so leans heavily on the syntactic canon of standard descriptions and on

annotated data reflecting these.

5

(see Biber et al. 1999: 6–7). The second book

raises a more fundamental question with respect to the difference between spoken

and written language: are the differences marginal, so that they can be captured in

a series of ‘footnotes’ to a description of the written language, or are they such

that they have important consequences for linguistic theory, as Miller and

Weinert claim? Both books take existing descriptions as their point of departure,

the one as a means to achieve a result (i.e. varieties differentiation), the other to

test their correctness and completeness. They are therefore firmly ingrained in the

corpus-based approach. This is not the place for an evaluation of the two books

and to assess whether Biber et al. is the last word on varieties differentiation or to

Does corpus linguistics exist? Some old and new issues

11

determine if Miller and Weinert make good their claim; I have mentioned them

because they illustrate the focus on spoken language syntax and because they

represent the two main strands in corpus-based research.

In the rest of this section I want to concentrate on the second strand of

research: the use of corpus data to test the adequacy and completeness of an

existing descriptive grammar. Unlike varieties differentiation, it does not accept

an existing description as an established fact. It is willing to assume that current

descriptions of English, based as they are mainly on the written medium, ‘are not

appropriate to the new material’, to borrow Sinclair’s words. It is therefore closer

to the corpus-driven approach. However, it does not take Sinclair’s statement as

axiomatic and as a point of departure for research, but merely accepts it as a

possibility.

As I argued above, in order to test an existing description consistently and

exhaustively on corpus data, it needs to be captured in a formal grammar.

However, testing a grammar on corpus data is less easy than it sounds. In the first

place, the test does not simply imply the yes-or-no decision whether a given parse

is successful or fails. The full extent of failure occurs of course when the parser

fails to yield an analysis for a given utterance. But it is also possible that an

analysis is yielded, but is ‘wrong’ in the sense that a structure is assigned which

under no contextual conditions can ever be correct. Finally, it may happen that a

grammatically correct analysis is assigned that is contextually inappropriate.

Whenever an instance of one of these three types of failure occurs, the linguist

must settle the question whether it is due to an error or omission in the description

underlying the formal grammar or due to a mistake in the formalization of the

description – unfortunately there is no one-to-one correspondence between the

type of failure and the location of its cause. The testing of a grammar on corpus

data is therefore a laborious and time-consuming process, requiring the full force

of the linguist’s attention and ingenuity. Every single utterance needs to be

inspected manually, and errors and omissions traced back to their location either

in the formalization of the description or in the description itself; in the latter case

it must be determined whether or not the utterance in question needs to be

accounted for in the description/grammar or not (see Section 2.2).

Now, in the practice of corpus linguistic research it is not usual to go to

the trouble of formalizing a description of general language and converting the

formal grammar into a (tagger and) parser for the sole purpose of testing the

grammar and the description. On the contrary, an effort like that is normally only

made for the purpose of producing a parsed corpus for future research. Such a

project, undertaken by the TOSCA team of the University of Nijmegen, was the

development and implementation of a tagger and parser for the ICE project (see

Greenbaum 1992; Aarts 1992; Aarts et al. 1998) and its subsequent application to

ICE-GB by the Survey team of University College London. Experiences with the

ICE project have taught us that one should continually be on the alert not to

‘stretch’ the grammar too much to make it fit the data (see Aarts and Oostdijk

12

Jan Aarts

1997: 111 ff.). Working in the other direction, a number of problematic utterances

in the spoken material were ‘solved’ by the Survey team by adding to them a

‘normalized’ version which could be dealt with by the parser without any

problems. The possibility that the pressure of having to produce a syntactically

annotated corpus can lead to making ‘the data ... fit the theory’ (Tognini-Bonelli

2001a: 73) in some way or other is therefore not entirely unreal. Ideally, it would

be best to keep the production of a parsed corpus separate from the testing of a

grammar to check the correctness and completeness of its underlying description,

and to carry them out as two distinct research activities.

The confrontation of the TOSCA tagger and parser with spoken material

has led to an enhanced view of the descriptive framework that served as its

starting point, which leads us to believe that the corpus-based approach starting

from a pre-existing description can be effective and rewarding. The enhanced

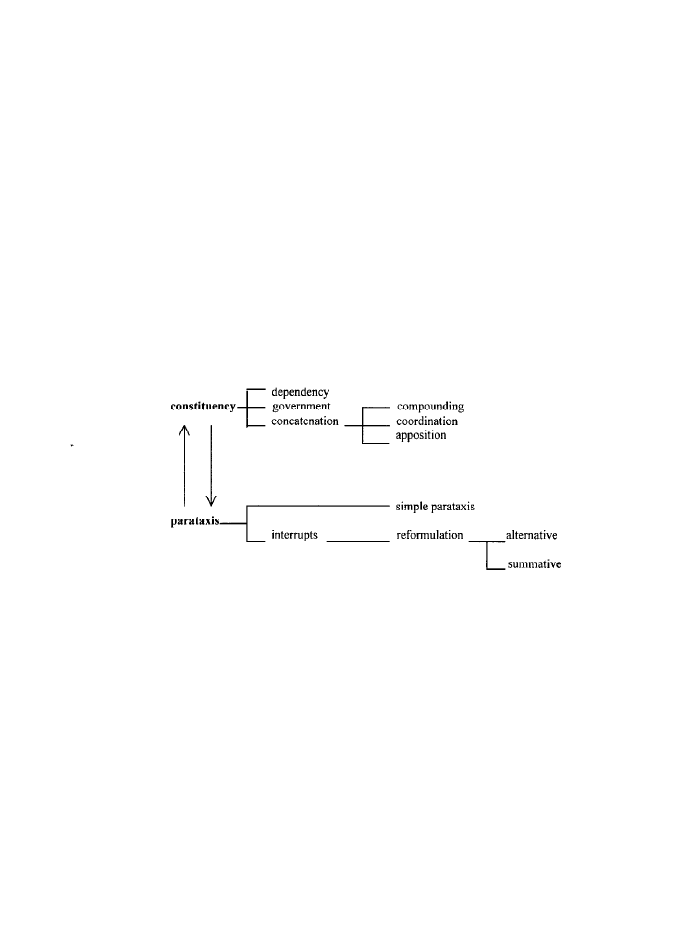

descriptive framework is shown schematically in Figure 2 (reproduced from Aarts

1999).

Figure 2. Enhanced descriptive framework

The top part of the figure represents what I have called above ‘the

syntactic canon’. It is entirely based on the notion of constituency and the

hierarchical relations among constituents. These relations are nearly always

expressed by syntactic means and are of three kinds: dependency, government

and concatenation. Dependency manifests itself in all subordination/

superordination structures, government in complementation structures, where the

governing element may impose a particular form on the element realizing the

complement, while concatenation involves compounding, coordination or

apposition. The building blocks for the lower part of the figure are also

constituents, but the only ‘structural’ relation with their environment derives from

the one-thing-next-to-the-other principle – there is no attempt whatsoever at

syntactic integration. A distinction can be made between simple parataxis and

Does corpus linguistics exist? Some old and new issues

13

interrupts, which are elements interrupting regular consistency; a subclass of

these can be used to reformulate (a part of) a constituent which immediately

precedes.

An instance of simple parataxis is found in the italicized part of the

following example:

(1) I have been the radioman for the last couple months or so – last guys got

transferred, I moved up.

An example of summative reformulation is found in (2):

(2) Bartlett was the only member of staff to sport a beard, which bobbed up

and down when he talked, a process Lucy found fascinating to watch.

As the last example shows, parataxis also occurs in the written language,

although it is much more frequent in speech. The utterance in (3) offers a good

example of its frequency – it contains several instances of parataxis of various

kinds, both on phrase level and on clause level:

(3)

and it becomes an accepted wisdom that people in certain areas one of

them is London that have certain income bands the middle classes if you

like the affluent middle classes that they should go private that they will

go private.

Parataxis differs from concatenation in that the latter is usually marked

syntactically and is fully integrated in the constituency of sentences, with the

concatenated constituents always forming a clearly delineated higher-order

constituent. The distinction between constituency and parataxis is not an absolute

one; they can be seen as the two extremes on a scale of syntactisation. Paratactic

and constituent-like variants of constructions can exist side by side: an example is

(paratactic) direct speech by the side of (syntactically integrated) indirect speech

and mixed forms in between these two extremes.

Relations between structural phenomena like constituency and parataxis

and, more in general, extensions and revisions of an accepted descriptive frame-

work will only emerge, of course, if one takes that framework as one’s starting

point, as is usual in the corpus-based approach.

4.

Conclusion

Returning to the question posed in the title of this paper, we can ask ourselves

another: when can we say that a particular linguistic research activity constitutes a

linguistic discipline in its own right? Surely not by virtue of its use of a particular

type of data – corpus linguistics does not distinguish itself from another linguistic

14

Jan Aarts

discipline like theoretical linguistics on account of the fact that it uses corpus

data, nor would theoretical linguistics become a subdivision of corpus linguistics

if all its practitioners should suddenly agree that corpus data are as valuable as

intuitive data. The picture begins to change a little bit if the use of corpus data is

not so much a question of preference but of necessity; neither the corpus-based

nor the corpus-driven approach can do without the use of corpora. And perhaps

the fact itself that these two approaches exist side by side can be regarded as a

sign of an independent discipline – it is a bit difficult to maintain that a discipline

that accommodates two competing methodological approaches does not exist.

However, what really distinguishes one discipline from another is a

differerence in the object of study. And in this respect there really is a difference

between theoretical linguistics and corpus linguistics: whereas the former is

concerned with the phenomenon of language in general (call it the language

faculty, competence, I-language or universal grammar) and its object of study is

therefore language-independent, corpus linguistics is concerned with language

use, that is, with the way in which a given language system manifests itself in a

particular context and cultural environment. It aims therefore not only at an

understanding of the language system, but also of the parameters that determine

the selection from the possibilities offered by the language system and thus shape

the ultimate form that utterances must take in order to be appropriate within their

micro- and macro-context. So yes, corpus linguistics does exist, and it is a

discipline harbouring two mutually exclusive methodologies, the corpus-based

and the corpus-driven approaches, which, in all likelihood, will come up with

different but complementary results that together will give a fuller picture of

language in use.

Notes

1

In what follows I shall go on using the term ‘corpus linguistics’ as if it does.

2

See

A revised version of the corpus is due to appear in the

autumn of 2001.

3

An exception must be made for two grammarians who can be looked upon as

corpus linguists avant la lettre: Fries (1952) and Scheurweghs (1959). Their

grammars are firmly based on corpus data.

4

Sinclair (1984) discusses the ‘naturalness’ of sentences, a term which at first

sight seems to imply the same sort of intuitive judgement. However, he describes

the quality of naturalness as being determined by the degree to which an utterance

obeys the constraints of the context.

5

See Biber et al. 1999: 7: ‘The overriding goal has been to use categories and

terms that are familiar and unobjectionable to the widest range of grammar users.

Since CGEL is terminologically conservative, generally following informed

Does corpus linguistics exist? Some old and new issues

15

tradition in its choice of grammatical terms and categories, we have rarely

departed from its overall framework.’

References

Aarts, B. 2000. Corpus linguistics, Chomsky and fuzzy tree fragments. In C. Mair

and M. Hundt (eds.) Corpus linguistics and linguistic theory. Amsterdam:

Rodopi. 5–13.

Aarts, J. 1991. Intuition-based and observation-based grammars. In K. Aijmer

and B. Altenberg (eds.) English corpus linguistics. Studies in honour of

Jan Svartvik. London: Longman. 44–62.

Aarts, J. 1999. The description of language use. In H. Hasselgård and S. Oksefjell

(eds.) Out of corpora: Studies in honour of Stig Johansson. Amsterdam:

Rodopi. 3–20.

Aarts, J. 2000. Towards a new generation of corpus-based English grammars. In

B. Lewandowska-Tomaszcyk and P. Melia (eds.) PALC ’99: Practical

applications in language corpora. Papers from the international

conference at the university of ód . Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. 17–

36.

Biber, D., S. Johansson, G. Leech, S. Conrad and E. Finegan. 1999. Longman

grammar of spoken and written English. Harlow, Essex: Longman.

Chomsky, N. 1965. Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge (Mass.): M.I.T.

Press.

De Mönnink, I. 2000. On the move. The mobility of constituents in the English

noun phrase: A multimethod approach. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Fillmore, C. 1992. ‘Corpus linguistics’ or ‘Computer-aided armchair linguistics’.

In J. Svartvik (ed.) Directions in corpus linguistics. Proceedings of Nobel

Symposium 82, Stockholm, 4–8 August 1991. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

35–60.

Fillmore, C. 2001. Armchair linguistics vs. corpus linguistics revisited. In S. De

Cock, G. Gilquin, S. Granger and S. Petch-Tyson (eds.) ICAME 2001.

Future challenges for corpus linguistics. Proceedings of the 22nd ICAME

conference. Louvain-la-Neuve: Université Catholique de Louvain. 1–2.

Fries, C. C. 1952. The structure of English. New York: Harcourt, Brace and

Company.

Greenbaum, S. 1988. Good English and the grammarian. London: Longman.

Jespersen, O. 1909–1949. A Modern English grammar on historical principles.

London: Allen and Unwin.

16

Jan Aarts

Leech, G. 1992. Corpora and theories of linguistic performance. In J. Svartvik

(ed.) Directions in corpus linguistics. Proceedings of Nobel Symposium

82, Stockholm, 4–8 August 1991. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 105–122.

Miller, J. and R. Weinert. 1998. Spontaneous spoken language: Syntax and

discourse. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Nagata, H. 1989. Judgments of sentence grammaticality and field-dependence of

subjects. In Perceptual and Motor Skills 69: 739–747.

Poutsma, H. 1928–1929. A grammar of late Modern English. Part I and Part II.

Groningen: Noordhoff.

Quirk, R. 1968. Essays on the English language: medieval and modern. London:

Longman.

Quirk, R. and J. Svartvik. 1966. Investigating linguistic acceptability. The Hague:

Mouton.

Schibsbye, K. 1965. A Modern English grammar. London: Oxford University

Press.

Shohamy, E. 1996. Competence and performance in grammar testing. In G.

Brown, K. Malmkjaer and J. Williams (eds.) Performance and competence

in second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

138–151.

Sinclair, J. 1984. Naturalness in language. In J. Aarts and W. Meijs (eds.) Corpus

linguistics: Recent developments in the use of computer corpora in

English language research. Amsterdam: Rodopi. 203–210.

Sinclair, J. 1985. Selected issues. In R. Quirk and H. Widdowson (eds.) English

in the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Snow, C. and G. Meijer. 1977. On the secondary nature of syntactic intuitions. In

S. Greenbaum (ed.) Acceptability in Language. The Hague: Mouton. 163–

177.

Strang, B. M. H. 1962. Modern English structure. London: Edward Arnold.

Sweet, H. 1900. A new English grammar, logical and historical. Part I. Oxford:

Clarendon Press.

Tognini-Bonelli, E. 2001a. Corpus linguistics at work. Amsterdam: John

Benjamins.

Tognini-Bonelli, E. 2001b. Towards a corpus-driven approach. In S. D. Cock, G.

Gilquin, S. Granger and S. Petch-Tyson (eds.) ICAME 2001. Future

challenges for corpus linguistics. Proceedings of the 22nd ICAME

conference. Louvain-la-Neuve: Université Catholique de Louvain. 99–

101.

Widdowson, H. G. 1991. The description and prescription of language. In J.

Alatis (ed.) Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and

Linguistics 1991. Linguistics and language pedagogy: The state of the art.

Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press. 11–24.

Does corpus linguistics exist? Some old and new issues

17

Zandvoort, R. W. 1945. A handbook of English grammar. Groningen: J. B.

Wolters.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

#0514 – Describing Old and New Clothes

The Vampire in Literature Old and New BA Essay by Elísabet Erla Kristjánsdóttir (2014)

Discrimination testing a few ideas, old and new

Anon An Answer to the Booke Called Observations of the old and new Militia

H Belloc The Old and New Enemies of the Catholic Church

Linguistic and Cultural Issues in Literary Translation

Chicago and New York Jazz

2008 5 SEP Practical Applications and New Perspectives in Veterinary Behavior

Brecht the realist and New German Cinema

Old Process, New Technology Modern Mokume

Alasdair C MacIntyre First Principles, Final Ends And Contemporary Issues

130 STUDIES LINKING VACCINES TO NEUROLOGICAL AND AUTOIMMUNE ISSUES COMMON TO AUTISM 4

christmas and new year a glossary for esl learners

Computer Virus Operation and New Directions

Shigellosis challenges and management issues

richter New economic sociology and new institutional economics

Corpus linguistics past, present, future A view from Oslo

Victoria Fontan Voices from Post Saddam Iraq, Living with Terrorism, Insurgency, and New Forms of T

więcej podobnych podstron