Associations Between Symptoms of Borderline

Personality Disorder, Externalizing Disorders,

and Suicide-Related Behaviors

Lisa M. James

&

Jeanette Taylor

Published online: 4 January 2008

# Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2007

Abstract Borderline personality disorder and externalizing

disorders are associated with suicide-related behaviors. The

present study examined whether symptoms of borderline

personality disorder mediate the relationship between

externalizing disorders and suicide-related behaviors. Diag-

nostic interviews were administered to 344 participants (n=

233 women). Results indicated that symptoms of antisocial

personality disorder, alcohol use disorders, and drug use

disorders each were significantly associated with suicide

threats and self-injurious behavior in women and symptoms

of antisocial personality disorder were associated with

suicide attempts in women. With the exception of the

association between symptoms of alcohol dependence and

self-injurious behaviors, borderline personality disorder

symptoms mediated or partially mediated all associations

between externalizing disorders and suicide-related behav-

iors in women. These results highlight the importance of

assessment and treatment of borderline personality disorder

symptoms in individuals with externalizing disorders,

particularly in the presence of suicide-related behaviors.

Keywords Borderline personality disorder . Externalizing

disorders . Suicide-related behavior . Mediation

Suicide is among the leading causes of death in the USA

(Kochanek et al.

) and suicide-related behavior was the

fifth most common reason for mental health-related visits to

the emergency room between 1992 and 2001 (Larken et al.

). Suicide-related behaviors (i.e., self-injurious behav-

ior, suicide threats, suicide attempts, and suicide comple-

tions; O

’Carroll et al.

) occur most often among those

with clinical disorders although the prevalence of suicide-

related behaviors in non-clinical samples is noteworthy

(Kessler et al.

). For example, Kessler et al. (

reported that 13.5% of a nationally representative sample of

adults reported lifetime suicidal ideation and 4.6% attemp-

ted suicide. Among young people, ages 15

–24, suicide is

the third-leading cause of death (Kochanek et al.

) and

a study of college students noted that 10% reported

seriously considering suicide in the 12 months prior to the

study and 2% attempted suicide at least once (Brenner et al.

). Prior suicide-related behavior is the single best

predictor of future suicide-related behavior (Joiner et al.

; Kessler et al.

); thus, further understanding the

correlates of suicide-related behavior is important for

assessment and prevention of suicide.

Borderline personality disorder is often associated with

self-injury and suicide attempts (i.e., parasuicidal behavior)

in adults. Approximately 60

–80% of individuals with

borderline personality disorder engage in parasuicidal

behavior (see Linehan and Heard

, for a review), and

10% die of suicide (Paris and Zweig-Frank

). Among

personality disorders, substantial research also documents a

relationship between suicide-related behavior and antisocial

personality disorder (Duberstein and Conwell

; Verona

et al.

). Approximately 30

–40% of suicides are

committed by individuals with Axis II disorders and

borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality

disorder account for a large majority of these (Duberstein

and Conwell

). A consistent relationship between

substance use disorders and suicide-related behaviors has

also been documented (Haw et al.

; Kessler et al.

;

also see Wilcox et al.

, for review) and it has been

reported that up to two thirds of individuals that complete

suicide had a diagnosable substance use disorder (Conwell

J Psychopathol Behav Assess (2008) 30:1

–9

DOI 10.1007/s10862-007-9074-9

L. M. James (

*)

:

J. Taylor

Department of Psychology, Florida State University,

209 Eppes Hall,

Tallahassee, FL 32306-1270, USA

e-mail: james@psy.fsu.edu

et al.

). Adding to a growing body of literature, two

recent epidemiological studies found that symptoms of

antisocial personality disorder and substance use disorders

were associated with suicide attempts and completions

(Verona et al.

; Hills et al.

Thus, in addition to borderline personality disorder, both

antisocial personality disorder and substance use disorders

(i.e., externalizing disorders) are also associated with

suicide-related behavior and recently it has been suggested

that borderline personality disorder might mediate that

relationship (Hills et al.

). This potential link has not

been examined although various lines of evidence support

this possibility. For instance, both antisocial personality

disorder and substance use disorders are highly comorbid

with borderline personality disorder. Approximately 25% of

borderline patients also meet criteria for antisocial person-

ality disorder (Zanarini et al.

), although Axis II

pathology is not limited to psychiatric patients. In fact, one

recent study found that the prevalence of personality

disorders in a community sample was 11% (Ekselius et al.

). Notably, prior research suggests that the risk for

suicide in borderline personality disorder patients is even

greater in the presence of antisocial traits (Black et al.

). Regarding comorbidity with substance use, a recent

review of the literature indicated that approximately 50% of

study participants with borderline personality disorder also

met criteria for an alcohol use disorder and roughly 40%

met criteria for a comorbid drug use disorder (Trull et al.

). Similarly, these authors noted high rates of comorbid

borderline personality disorder among those with substance

use disorders.

Further, these disorders share a common relationship

with impulsivity. Externalizing disorders are characterized

by impulse control problems and acting out behaviors that

may be harmful to oneself or others (Verona and Patrick

) and this conceptualization has garnered substantial

support (Cloninger

; Gorenstein and Newman

McGue et al.

; Moeller and Dougherty

; Sher and

Trull

). Although borderline personality disorder is not

typically considered an externalizing disorder, character-

istics of externalizing disorders such as impulsivity and

self-harm are among the hallmark features of borderline

personality disorder. Impulsivity is considered a core

feature of borderline personality disorder (Links et al.

) and two recent reviews (Bornolova et al.

; Trull

et al.

) suggest that impulsivity might be a common

process that underlies the comorbidity between borderline

personality disorder and substance use disorders. Impulsiv-

ity has also been linked to suicide-related behaviors and

substantial research suggests that impulsivity is associated

with self-injury (Crowell et al.

), suicide attempts

(Dougherty et al.

), and suicide completions (Maser et

al.

Finally, it seems that suicide-related behaviors and

externalizing disorders are underlain by common neurobi-

ological mechanisms. In a review of the literature, Verona

and Patrick (

) noted that a reliable association exists

between decreased serotonergic functioning, suicide-related

behaviors, and features of externalizing disorders such as

impulsivity, aggression, and violence. Serotonergic systems

have also been implicated in borderline personality disor-

der. Oquenda and Mann (

) reviewed various lines of

human and animal research including fenflumarine chal-

lenge, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain imaging studies that

converge on findings of reduced serotonergic functioning in

individuals with borderline personality disorder, particular-

ly in those with higher impulsive and aggressive behavior

or more suicide-related behavior.

In sum, independent lines of research have found that

borderline personality disorder and externalizing disorders

are associated with suicide-related behaviors. These disor-

ders are highly comorbid and share links with personality

traits and neurobiological factors. As suggested by Hills et

al. (

), it is possible that borderline personality disorder

symptoms mediate the relationship between externalizing

disorders and suicide-related behaviors and the goal of the

current study was to assess this possibility in a non-clinical

sample given the prevalence of suicide-related behaviors in

non-clinical populations. Consistent with previous litera-

ture, it was expected that symptoms of externalizing

disorders would be associated with suicide-related behav-

iors but, as suggested by Hills et al. (

), it was

hypothesized that these relationships would become non-

significant after accounting for borderline personality

disorder symptoms. Although it is not possible to draw

conclusions regarding causality in this study due to the

cross-sectional design, several recent studies have similarly

examined mediation in cross-sectional studies to provide a

useful initial test of a model (e.g., Orcutt et al.

; Sachs-

Ericsson et al.

Method

Participants

The data for this study were obtained from a series of

studies aimed at examining risk factors associated with

personality disorders and substance use disorders. Partic-

ipants were 344 individuals (n=233 women) who had

participated in one of three studies conducted between 2001

and 2006 at a large southeastern university. Most of the

participants were college students, including 115 members

of twin pairs recruited for a paid twin study, 123 individuals

recruited for a paid study on physiological reactivity and

substance use, and 70 individuals recruited for a study of

2

J Psychopathol Behav Assess (2008) 30:1

–9

physiological and cognitive factors associated with person-

ality and substance use for which they received credit in an

introductory psychology course. The remainder of the

sample comprised 36 members of twin pairs recruited from

the community with newspaper advertisements for the paid

twin study. Participants were pooled across studies in order

to provide adequate power to test hypotheses given the low

base rate of suicide-related behaviors. Participants were age

18 to 58 years (mean = 20.41, SD = 4.79). The racial

composition was 0.6% American Indian/Alaska Native,

0.6% Asian, 15.0% Black/African American, 9.3% Hispanic/

Latino, 0.9% Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander,

70.1% white, and 3.6% Other (included those that affiliated

with more than one ethnic category and those that felt their

ethnic category was not represented). The racial composition

was largely representative of the racial/ethnic distribution of

the community in which the studies were conducted. Twelve

percent of the sample were freshmen, 30% were sophomores,

26% were juniors, 19% were seniors, and 12% had completed

college. In each study from which participants for this study

were drawn, informed written consent was obtained prior to

beginning any procedures and the university IRB approved all

procedures.

Procedures and Measures

The studies from which the participants were drawn used

similar though not identical methods for assessing person-

ality disorders and substance use disorders. Differences in

assessment measures across the samples are noted below.

Personality Disorder Symptoms

All participants completed semistructured diagnostic inter-

views to assess the presence of Axis II symptoms.

Interviews were conducted by clinical graduate students

trained by one of the authors (J.T.), a Ph.D.-level clinical

psychologist. Seventy participants were administered the

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Person-

ality Disorders (SCID-II; First et al.

) and 274 were

administered the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Person-

ality (SIDP-IV; Pfohl et al.

). In all cases, the

interviews were audio taped. In the study that used the

SCID-II, the trained interviewer assigned symptoms. In

the two studies that used the SIDP-IV, two or more clinical

graduate students who reviewed all available information

and came to a consensus on the presence or absence of a

symptom assigned symptoms. In all cases, symptom level

data were then entered into a computer. For this particular

study only items assessing borderline personality disorder

and antisocial personality disorder were included. Symptom

counts of each disorder were created via a computer

algorithm that simply summed the positively endorsed

symptoms. The symptom assessing recurrent suicidal

threats, gestures, or behaviors was not included in the

symptom count for borderline personality disorder. Also,

although the diagnostic interviews include substance use as

part of the criteria for borderline personality disorder

impulsivity, substance use was not included in the

impulsivity criteria for the present study to avoid artificially

inflating comorbidity by means of shared symptomatology.

Similarly, although impulsivity is a feature of both

antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality

disorder, care was taken to avoid coding the same behavior

as impulsive for both disorders. In order to meet the

impulsivity criteria for both disorders participants had to

provide distinct examples of impulsivity that reflected

failure to plan ahead (e.g., walking off of a job) and

impulsivity that could be self-damaging (e.g., promiscuity,

binge-eating, etc.) as consistent with the DSM-IV criteria

for antisocial personality disorder and borderline personal-

ity disorder, respectively.

In the study using the SCID-II, reliability was assessed

by an independent interviewer who was blind to the

original interviewer

’s coding using the audiotapes of the

original interviews to assign symptoms on a random sample

of 10% of cases. In each of the two studies using the SIDP-

IV, the consensus case conference procedure described

above was repeated for a random sample of approximately

15% of cases by an independent team that was blind to the

original team

’s coding. Inter-rater reliability of symptom

counts was excellent across measures and procedures for

both borderline personality disorder (r=0.94

–0.96 for SID-

P; r=0.99 for SCID-II) and antisocial personality disorder

(r=0.84 for SID-P; r=1.0 for SCID-II). Approximately 2%

of the sample met threshold for formal diagnosis of BPD

(i.e., 5+ symptoms) and 6% of the sample met criteria for

ASPD (i.e., 3+ symptoms).

Substance Use Disorder Symptoms

All participants were administered diagnostic interviews to

assess the presence of symptoms of alcohol and drug abuse

and dependence. Drugs assessed included cannabis, stimu-

lants, cocaine, hallucinogens, opioids, sedatives, PCP, and

other (inhalants, steroids, etc.). Participants were adminis-

tered either the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First et al.

; n=193) or the

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI;

Sheehan et al.

; n=151). The SCID is often considered

the gold standard of clinical diagnoses (e.g., Shear et al.

) and concordance with the MINI is generally good

(Sheehan et al.

). In all cases, the interviews were

audio taped. For participants in one of the studies (n=70),

SCID symptoms were assigned by the trained interviewer.

The other two studies employed the consensus case

J Psychopathol Behav Assess (2008) 30:1

–9

3

3

conference procedure described above. In all cases, symp-

tom level data were entered into a computer. Separate

symptom counts were generated via computer algorithm for

alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, and drug

dependence. The latter two variables reflected the number

of symptoms met for the most used drug as reported by the

participant. The reliability procedures described above for

the personality disorder assessments were also used for

substance use disorders. The reliability of symptom counts

was excellent for all classes of substance dependence (r=

1.0 for MINI; r=0.94

–1.0 for SCID-I;) and abuse (r=0.86–

1.0 for MINI; r=0.81

–1.0 for SCID-I) with the following

exceptions for drugs assessed with the SCID-I: sedative

abuse (r=0.69), cannabis abuse (r=0.75),

“other” abuse

(r=0.73) and

“other” dependence (r=0.73), which were

acceptable. A substantial number of participants met the

diagnostic threshold for formal diagnosis of substance use

disorders: alcohol abuse

—26%, alcohol dependence—13%,

drug abuse

—19%, and drug dependence—16%.

Suicide-Related Behavior

Suicide-related behavior was assessed by endorsement of

the borderline personality disorder symptom regarding

recurrent suicide threats, attempts, or self-injurious behav-

ior. For this particular study, sub-threshold cases as well as

those meeting full criteria for suicide-related behavior were

included. Analyses were completed on categorical endorse-

ment of the subcomponents of this item (i.e., threats,

attempts, self-injury), resulting in three dependent varia-

bles. The inter-rater reliability was excellent across meas-

ures and procedures (r=0.89 for SCID-II; r=0.97

–1.0 for

SID-P).

Analyses

According to procedures outlined in Baron and Kenny

(

), independent logistic regression analyses were con-

ducted to test the ability of symptoms of borderline

personality disorder (minus the suicide-related behavior

item), antisocial personality disorder, alcohol dependence,

alcohol abuse, drug dependence, and drug abuse to predict

suicide related behavior (i.e., threats, attempts, and self-

injurious behavior). Any significant associations were

followed up with additional logistic regression analyses to

determine if borderline personality disorder symptoms

mediated the relationship. Mediational analyses were fol-

lowed by Sobel tests, which are designed to formally test the

significance of a mediator (Preacher and Leonardelli

).

Because Sobel tests are conservative (MacKinnon et al.

), p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

To provide an additional test of borderline personality

disorder symptoms as a mediator, the analyses were

repeated using borderline personality disorder symptoms as

the independent variable predicting suicide-related behav-

iors and mediating effects of each of the externalizing

disorders on that relationship were independently examined.

Results

Prior to data analysis, all variables were examined for

outlier values and normality of score distributions. Univar-

iate outlier values were adjusted after bringing the scores to

within three times the standard deviation of the mean of

each variable. Distributions for symptoms of antisocial

personality disorder and drug dependence were log trans-

formed to correct for kurtosis and all analyses were

completed on the transformed variables. For ease of

interpretation, results for transformed variables are pre-

sented in terms of raw scores. All remaining distributions

were normal.

Means and standard deviations for all variables are

presented in Table

. Missing data resulted in variable

sample sizes as indicated in Table

. Men endorsed

significantly more symptoms of antisocial personality

disorder and substance use disorders than women. There

was no gender difference for borderline personality disorder

symptoms or any of the suicide-related variables. The

relationships among the variables also differed for men and

women (Table

). Focused comparisons of effect size

contrasting the magnitude of the correlations between men

and women (Cohen

’s q) indicated generally small to

medium effects ranging from 0.01 to 0.38 (mean=0.15).

In women, all externalizing disorder symptoms were

associated with suicide threats and self-injurious behavior.

Only endorsement of symptoms of antisocial personality

disorder or borderline personality disorder was correlated

with suicide attempts in women. In men, borderline

personality disorder symptoms were significantly correlated

with recurrent self-injurious behavior. This was the only

significant correlation between externalizing disorder

symptoms and suicide-related behavior in men, suggesting

that the proposed mediation analyses were not warranted in

this sample of men. Thus, the following analyses were only

completed for women.

Logistic regressions indicated that symptoms of each of

the externalizing disorders significantly predicted suicide

threats in women and borderline personality disorder

symptoms mediated these relationships (Table

). Only

symptoms of antisocial personality disorder predicted

recurrent suicide attempts in women [Wald=8.28, Exp (B) =

66.42, p<0.004] and this relationship was also mediated by

borderline personality disorder symptoms (p>0.09). As with

suicide threats, symptoms of each of the externalizing

disorders significantly predicted self-injurious behavior in

4

J Psychopathol Behav Assess (2008) 30:1

–9

women (Table

). Borderline personality disorder symptoms

mediated the relationships between symptoms of drug

dependence and drug abuse with self-injurious behavior.

The relationships between alcohol abuse symptoms and

antisocial personality disorder symptoms to self-injury were

partially mediated by symptoms of borderline personality

disorder. Borderline personality disorder symptoms failed to

mediate the relationship between alcohol dependence symp-

toms and self-injury

1

. Sobel test statistics were computed for

each of the significant mediation analyses. In all cases,

borderline personality disorder symptoms significantly re-

duced the effect of symptoms of externalizing disorders on

suicide-related variables, formally demonstrating that bor-

derline personality disorder symptoms significantly mediated

these relationships (p<0.005 except for the associations

between symptoms of alcohol use disorders and suicide-

related variables which were significant at p<0.05).

Analyses were repeated using borderline personality

disorder symptoms as the independent variable predicting

suicide-related behaviors and mediating effects of each of

the externalizing disorders on that relationship were

independently examined. The relationship between border-

line personality disorder symptoms and suicide-related

behaviors remained significant at p<0.001 in all of the

analyses.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies utilizing community

samples (Hills et al.

; Verona et al.

), externalizing

disorder symptoms were associated with suicide-related

behavior in the current study, providing further evidence

that suicide-related behaviors are not limited to clinical

samples; however, self-injury, suicide attempts, and suicide

threats were only associated with symptoms of externaliz-

ing disorders in women in the present study. The current

sample was comprised of considerably more women than

men and relatively few men endorsed suicide-related

behavior in the current study so there may not have been

adequate power to examine these relationships in men.

Similarly, generally low endorsement of suicide-related

behavior may have limited power to detect gender differ-

ences on suicide-related variables as previous studies have

found that women were significantly more likely to engage

in suicide behaviors than men (Verona et al.

). The

findings regarding gender differences in externalizing

disorder symptoms were in the expected direction and

consistent with previous literature. In the present study

there were no gender differences in the mean number of

borderline personality disorder symptoms. Similarly, Johnson

et al. (

) reported no gender differences regarding the

mean numbers of BPD criteria in patients diagnosed with

BPD although they reported that almost three times as many

women met diagnostic criteria for BPD than men. In line

with the present study and with Johnson et al., Skodol and

Bender (

) reviewed several studies that found little to no

gender difference in borderline personality disorder symp-

tomatology and concluded that reported gender differences

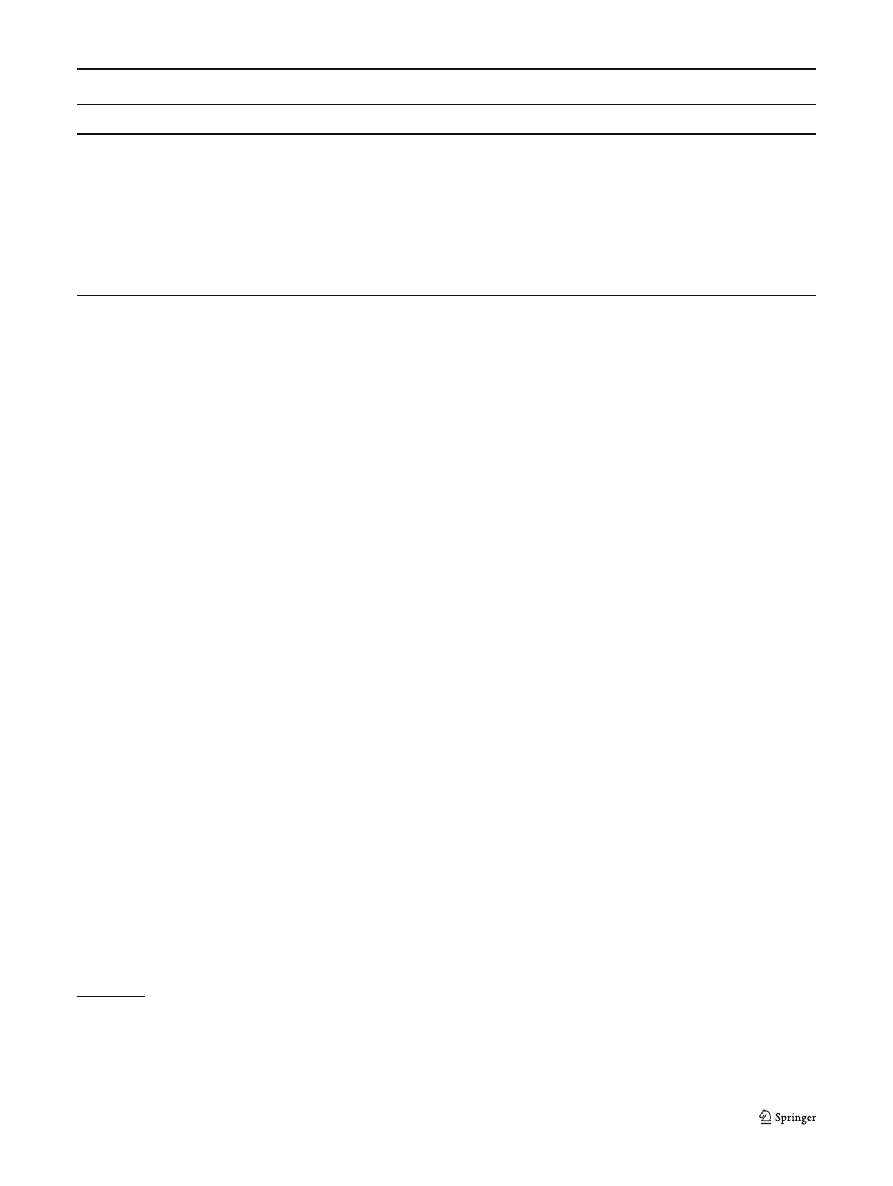

Table 1 Means, standard deviations, and percent endorsement of variables

Men

N

b

(%)

c

Women

N

b

(%)

c

t

ASPD

0.77 (1.12)

109 (40.5)

0.31 (.81)

233 (16.7)

2.88**

Alc-D

1.25 (1.63)

103 (44.5)

0.69 (1.17)

223 (33.5)

3.28**

Alc-A

0.61 (0.92)

104 (34.5)

0.33 (0.67)

219 (21.8)

2.88**

BPD

0.60 (0.86)

110 (39.5)

0.57 (1.04)

227 (30.9)

ns

Drug-D

1.04 (1.7)

109 (31.8)

0.67 (1.43)

227 (21.8)

2.13*

Drug-A

0.43 (0.82)

107 (26.4)

0.22 (0.57)

225 (14.6)

2.60**

Threat

5

a

111 (4.6)

16

a

233 (6.9)

ns

d

Attempt

2

a

111 (1.9)

11

a

233 (4.7)

ns

d

SIB

6

a

111 (5.6)

22

a

233 (9.4)

ns

d

ASPD Antisocial personality disorder symptoms, Alc-D alcohol dependence symptoms, Alc-A alcohol abuse symptoms, BPD borderline

personality disorder symptoms, Drug-D drug dependence symptoms, Drug-A drug abuse symptoms, threat suicide threats, attempt suicide

attempts, SIB self-injurious behavior

*p<0.05

**p<0.01

a

Number of participants endorsing

b

Number of participants with data on variable

c

Percent of sample endorsing at least one symptom

d

Mann

–Whitney U test

1

Since some of the participants (n=142) used in this study were

members of a twin pair, one twin was randomly excluded from

complete twin pairs and the data were reanalyzed. The results

remained unchanged except symptoms of drug dependence no longer

predicted suicide threats (p>0.117).

J Psychopathol Behav Assess (2008) 30:1

–9

5

5

might be a result of biases in sampling or in the application

and assessment of diagnostic criteria.

In general, there was relatively low endorsement of

suicide-related behaviors in this sample, particularly in

men, and considerably fewer participants endorsed suicide

threats and attempts as compared to self-injurious behavior.

Regarding suicide attempts, it is interesting that only

antisocial personality disorder symptoms and borderline

personality disorder symptoms were predictive of suicide

attempts in women. Alcohol and drug use have been

associated with suicide attempts in previous studies so it

is unclear why this relationship did not bear out in the

present study. One possibility is that alcohol and drug use

may be relatively normative in a sample containing a

substantial portion of undergraduate students. In contrast,

those endorsing symptoms of borderline or antisocial

personality disorder may be more pathological and more

prone to extreme behaviors such as suicide attempts. In

addition, drug use in this study was predominantly

characterized by cannabis abuse and dependence. Although

there is limited research examining the association of

suicide related behaviors and cannabis use (Wilcox et al.

), the available literature suggests that suicide risk in

cannabis users is indirectly conferred from environmental

factors (i.e., sociodemographic disadvantage) and/or comor-

bidity with other disorders rather than directly associated

with cannabis use (Beautrais et al.

). In contrast,

substantial research (see Wilcox et al.

for review)

supports robust associations between other drugs (e.g.,

opiates) and suicide attempts. Thus, replication of this study

in a sample of heterogeneous substance users may help

clarify whether the results of the current study extend to

other types of drugs.

In contrast to suicide attempts, all variables of interest

were associated with self-injurious behavior and suicide

threats in women. This study adds to the growing body of

literature documenting associations between externalizing

disorders and self-injury but is among the first studies to

examine the relationship between externalizing disorders

and suicide threats. In the present study, symptoms of

substance use disorders and antisocial personality disorder

were each associated with recurrent suicide threats in

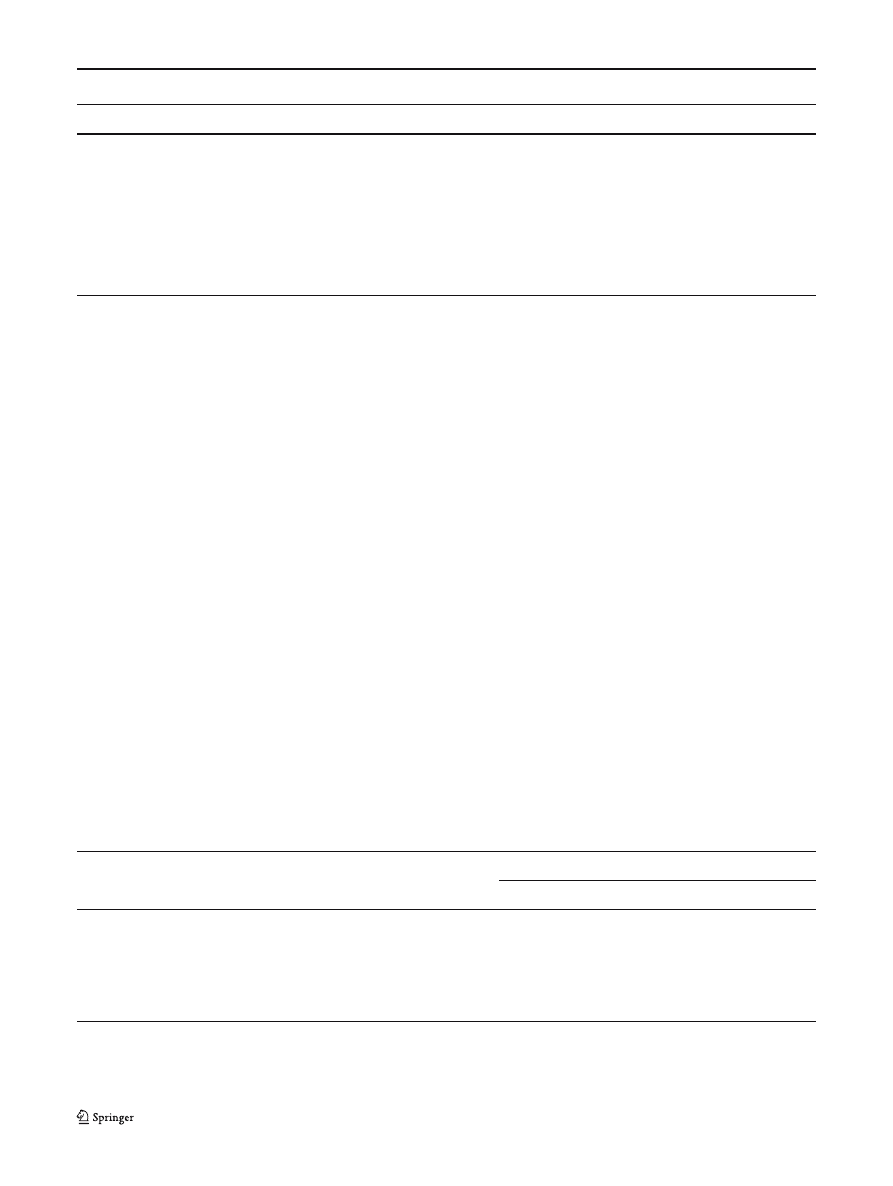

Table 3 Logistic regression and mediation analyses for suicide threats in women

Controlling for BPD

B

SE B

Wald value

EXP(B)

p value

B

SE B

Wald value

EXP(B)

p value

ASPD

4.22

1.31

10.35

67.79

0.001

2.36

1.45

2.68

10.62

0.102

Alc-D

0.44

0.18

6.34

1.55

0.012

0.39

0.22

3.11

1.48

0.078

Alc-A

0.76

0.31

6.06

2.15

0.014

0.58

0.38

2.37

1.79

0.124

Drug-D

2.36

0.94

6.29

10.54

0.012

0.47

1.17

0.16

1.59

0.690

Drug-A

0.85

0.31

7.82

2.35

0.005

0.26

0.36

0.52

1.29

0.47

BPD

1.11

0.21

28.63

3.03

0.000

Significant results are in bold.

ASPD Antisocial personality disorder symptoms, Alc-D alcohol dependence symptoms, Alc-A alcohol abuse symptoms, BPD borderline

personality disorder symptoms, Drug-D drug dependence symptoms, Drug-A drug abuse symptoms

Table 2 Correlation for all variables in men and women

Variable

ASPD

Alc-D

Alc-A

BPD

Drug-D

Drug-A

Threat

Attempt

SIB

ASPD

–

0.17**

0.33***

0.41***

0.21**

0.32***

0.27***

0.21**

0.26***

Alc-D

0.23*

–

0.70***

0.15*

0.36***

0.29***

0.18**

0.05

0.30***

Alc-A

0.39***

0.80***

–

0.22**

0.44***

0.29***

0.18**

0.05

0.22**

BPD

0.34***

0.49***

0.48***

–

0.32***

0.34***

0.46***

0.29***

0.38***

Drug-D

0.42***

0.44***

0.47***

0.39***

–

0.68***

0.17**

0.12

0.22**

Drug-A

0.41***

0.19

0.29**

0.27**

0.63***

–

0.21**

0.13

0.15*

Threat

0.01

−0.01

0.05

0.12

0.02

0.02

–

0.50***

0.51***

Attempt

0.03

0.06

0.14

0.14

0.08

−0.05

0.62***

–

0.35***

SIB

0.09

0.09

0.15

0.28**

0.08

0.05

0.72***

0.57***

–

Correlations for men are below the diagonal. Correlations for women are above the diagonal. ASPD Antisocial personality disorder symptoms,

Alc-D alcohol dependence symptoms, Alc-A alcohol abuse symptoms, BPD borderline personality disorder symptoms, Drug-D drug dependence

symptoms, Drug-A drug abuse symptoms, threat suicide threats, attempt suicide attempts, SIB self-injurious behavior

*p<0.05

**p<0.01

***p<0.001

6

J Psychopathol Behav Assess (2008) 30:1

–9

women and this is consistent with findings from the only

other study that examined this relationship. Lambert and

Bonner (

) noted that patients who threatened suicide to

increase the chance of hospital admission were more likely

to have substance dependence and exhibit antisocial

behavior. Both self-injury (Cooper et al.

) and suicide

threats (Shafii et al.

) are good indicators of future

suicide-related behaviors and additional research regarding

the associations between these behaviors and externalizing

disorders may provide useful clues for treatment and

prevention of suicidal behavior in populations characterized

by externalizing pathology.

As expected, symptoms of borderline personality disor-

der mediated most of the relationships between symptoms

of externalizing disorders and suicide-related behavior in

women. Notably, the relationships between symptoms of

alcohol-related disorders and self-injurious behavior and

symptoms of antisocial personality disorder and self-

injurious behaviors in women were not fully accounted

for by borderline personality disorder symptoms. One

possible explanation for this is that different processes

drive self-injurious behavior in women with alcohol-related

symptoms and antisocial personality disorder symptoms as

compared to women with drug-related symptoms. For

instance, the former may be driven by negative emotional-

ity whereas the latter may be linked more to impulsivity.

Prominent theories of suicide such as the hopelessness

theory of Beck et al. (

) and Baumeister

’s (

escape theory emphasize the role of negative affect and lack

of impulse control, respectively, in suicidal behavior. Other

theorists have proposed subtypes of suicidality (e.g., Apter

et al.

; Durkheim 1897/

). Apter et al. (

suggest that there are two types of suicidal behaviors: one

associated with depression and characterized by a wish to

die and another associated with aggression and impulsivity

and characterized by a desire to escape momentarily (Apter

et al.

). Inappropriate anger that can include aggression

and impulsivity are features of borderline personality

disorder and may be the mechanisms through which

borderline personality disorder symptoms mediated or

partially mediated most of the relationships between

externalizing disorders and suicide-related behaviors. That

is, for some individuals, suicide threats, attempts, or self-

injurious behavior may be attempts, albeit ineffective, to

communicate or manage anger or frustration. In contrast,

symptoms of borderline personality disorder did not

mediate the relationship between symptoms of alcohol

dependence and self-injurious behavior, suggesting that

relationship may be more strongly driven by depression.

The current study provides some initial insight into the

relationship between externalizing disorders and suicide-

related behaviors, particularly in women, and suggests

several additional avenues for future research. The use of

clinical interviews in a relatively large sample is a notable

strength of the current study. In addition, alcohol and drug

use were not included as part of the impulsivity criteria for

borderline personality disorder, reducing the possibility that

associations between symptoms of substance use disorders

and borderline personality disorder are limited to symptom

overlap. Similarly, an effort was made to reduce symptom

overlap between borderline personality disorder and antiso-

cial personality disorder by carefully assessing impulsivity.

The use of the borderline personality disorder symptom

regarding recurrent suicide threats, attempts, and self-injury

as an outcome measure was a limitation of the current

study. Future studies utilizing standard comprehensive

measures of suicide-related behaviors would be a useful

contribution to this area. Another limitation of the current

study was that men were under-represented and, due to

their low endorsement of suicide-related behaviors, there

may not have been adequate power to examine relation-

ships between externalizing disorders and suicide-related

behaviors in men. Previous studies reporting significant

associations between externalizing disorders and suicide-

related behaviors in men utilized large epidemiological

samples. For instance, Verona et al. (

) reported on

2,265 men. Of those, only 44 men (1.9%) had attempted

suicide in their lifetime. Thus, the rate of suicide-related

Table 4 Logistic regression and mediation analyses for self-injurious behavior in women

Controlling for BPD

B

SE B

Wald value

EXP(B)

p value

B

SE B

Wald value

EXP(B)

p value

ASPD

4.35

1.24

12.41

77.88

0.000

2.78

1.32

4.42

16.18

0.036

Alc-D

0.61

0.16

15.48

1.84

0.000

0.58

0.17

12.02

1.79

0.001

Alc-A

0.83

0.27

9.30

2.29

0.002

0.67

0.30

5.07

1.96

0.024

Drug-D

2.84

0.84

11.55

17.12

0.001

1.69

0.95

3.20

5.44

0.074

Drug-A

0.64

0.29

4.67

1.89

0.031

0.14

0.33

0.18

1.15

0.67

BPD

0.84

0.17

23.42

2.31

0.000

Significant results are in bold.

ASPD Antisocial personality disorder symptoms, Alc-D alcohol dependence symptoms, Alc-A alcohol abuse symptoms, BPD borderline

personality disorder symptoms, Drug-D drug dependence symptoms, Drug-A drug abuse symptoms

J Psychopathol Behav Assess (2008) 30:1

–9

7

7

behavior in the current study is comparable although a

larger sample may have been necessary to detect significant

relationships. Although externalizing disorders are associ-

ated with suicide-related behavior even after accounting for

depression and other internalizing disorders (Verona et al.

), it is possible that affective disorders may contribute

to or partially explain suicide-related behaviors. It was not

possible to examine the potential impact of affective

disorders on suicide-related behaviors in this sample and

future research examining associations between externaliz-

ing disorders, borderline personality disorder, and suicide-

related behaviors would be enhanced by the ability to parse

out the influence of affective disorders on these associa-

tions. Another limitation is that the sample was derived by

combining separately recruited participants from different,

albeit very similar, studies. The diagnostic interviews used

for the studies are generally comparable in terms of

psychometric properties and are widely used; however, it

is possible that the different formats used across studies

result in different response styles, which potentially

represents a limitation of the current study. Moreover, some

of the participants were members of a twin pair, which

might limit generalizability. Finally, the data from the

present study were cross-sectional, which prohibits con-

clusions regarding causality. Future studies utilizing longi-

tudinal designs are necessary to establish temporal

sequence and help rule out alternative explanations. Despite

these limitations, the current study provides a useful step

toward understanding suicide-related behaviors as they

relate to externalizing disorders, especially in women.

The results of this study suggest important consider-

ations regarding treatment of externalizing disorders. In

both men and women, borderline personality disorder was

highly associated with externalizing disorders. Thus,

assessment and treatment of borderline personality disorder

symptoms in individuals with externalizing disorders is

important, particularly in the presence of suicide-related

behaviors. Furthermore, thorough assessment of borderline

personality disorder may be especially important in settings

that focus on treating substance use disorders where Axis II

assessment may not be a priority. Finally, for individuals

with borderline personality disorder symptoms, treatment

outcomes for externalizing disorders may be enhanced by

incorporation of techniques designed specifically for bor-

derline personality disorder such as Linehan

’s (

dialectical behavior therapy.

References

Apter, A., Gothelf, D., Orbach, I., Weizman, R., Ratzoni, G., Har-

Even, D., et al. (1995). Correlation of suicidal and violent

behavior in different diagnostic categories of hospitalized

adolescent inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child

and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(7), 912

–918.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator

–mediator

variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual,

strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 51, 1173

–1182.

Baumeister, R. F. (1990). Suicide as escape from self. Psychological

Reivew, 97, 90

–113.

Beautrais, A. L., Joyce, P. R., & Mulder, R. T. (1999). Cannabis abuse

and serious suicide attempts. Addiction, 94(8), 1155

–1164.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R., Kovacs, M., & Garrison, B. (1985).

Hopelessness and eventual suicide: A 10-year prospective study

of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. American Journal

of Psychiatry, 142, 559

–563.

Black, D. W., Blum, M., Pfohl, B., & Hale, N. (2004). Suicidal

behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk

factors, prediction, and prevention. Journal of Personality

Disorders, 18(3), 226

–239.

Bornovalova, M. A., Lejuez, C. W., Daughters, S. B., Rosenthal, M. Z., &

Lynch, T. R. (2005). Impulsivity as a common process across

borderline personality and substance use disorders. Clinical

Psychology Review, 25, 790

–812.

Brenner, N. D., Barrios, L. C., & Hassan, S. S. (1999). Suicidal

ideation among college students in the United States. Journal of

Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(6), 1004

–1008.

Cloninger, C. R. (1987). Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in

alcoholism. Science, 236, 410

–416.

Conwell, Y., Duberstein, P. R., Cox, C., Hermann, J. H., Forbes, N. T.,

& Caine, E. D. (1996). Relationships of age and axis I diagnoses

in victims of completed suicide: a psychological autopsy study.

American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(8), 1001

–1008.

Cooper, J., Kapur, N., Webb, R., Lawlor, M., Guthrie, E., Mackway-

Jone, K., et al. (2005). Suicide after deliberate self-harm:

A 4-year cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(2),

297

–303.

Crowell, S. E., Beauchaine, T. P., McCauley, E., Smith, C. J.,

Stevens, A. L., & Sylvers, P. (2005). Psychological, autonomic,

and serotonergic correlates of parasuicide among adolescent

girls. Development and Psychopathology, 17(4), 1105

–1127.

Dougherty, D. B., Mathias, C. W., Marsh, T. M., Papageorgiou, T. D.,

Swann, A. C., & Moeller, F. G. (2004). Laboratory measured

behavioral impulsivity relates to suicide attempt history. Suicide

and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34(4), 374

–385.

Duberstein, P. R., & Conwell, Y. (1997). Personality disorders and

completed suicide: A methodological and conceptual review.

Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 4(4), 359

–376.

Durkheim, E. (1951). Suicide: A study in sociology (J. A. Spaulding &

G. Simpson, Trans.). Illinois: Free Press (Original work pub-

lished in 1897).

Ekselius, L., Tillfors, M., Furmark, T., & Fredrikson, M. (2001).

Personality disorders in the general population: DSM-IV and

ICD-10 defined prevalence as related to sociodemographic

profile. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 311

–320.

First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J., & Benjamin, L. S.

(1997). Structured clinical interview for DSM- IV axis II

personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American

Psychiatric Press Inc.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. E. W. (1995).

Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I, disorders-non-

patient Edition (SCID-I/NP, Version 2.0). New York: Biometrics

Research Department, State Psychiatric Institute.

Gorenstein, E. E., & Newman, J. P. (1980). Disinhibitory psychopa-

thology: A new perspective and a model for research. Psycho-

logical Review, 87, 301

–315.

Haw, C., Hawton, K., Casey, D., Bale, E., & Shepherd, A. (2005).

Alcohol dependence, excessive drinking and deliberate self-

8

J Psychopathol Behav Assess (2008) 30:1

–9

harm: Trends and patterns in Oxford, 1989

–2002. Social

Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(12), 964

–971.

Hills, A. L., Cox, B. J., McWilliams, L. A., & Sareen, J. (2005).

Suicide attempts and externalizing psychopathology in a nation-

ally representative sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 46(5),

334

–339.

Johnson, D. M., Shea, M. T., Yen, S., Battle, C. L., Zlotnick, C.,

Sanislow, C. A., et al. (2003). Gender differences in borderline

personality disorder: Findings from the Collaborative Longitudi-

nal Personality Disorders Study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 44

(4), 284

–292.

Joiner, T. E., Conwell, Y., Fitzpatrick, K. K., Witte, T. K., Schmidt, N. B.,

Berlim, M. T., et al. (2005). Four studies on how past and current

suicidality relate even when

“everything but the kitchen sink” is

covaried. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(2), 291

–303.

Kessler, R. C., Borges, G., & Walters, E. (1999). Prevalence of and

risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National

Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(7),

617

–626.

Kochanek, K. D., Murphy, S. L., Anderson, R. N., & Scott, C. (2004).

Deaths: final data for 2002. National Vital Statistics Reports, 53

(5), 1

–115.

Lambert, M. T., & Bonner, J. (1996). Characteristics and six-month

outcome of patients who use suicide threats to seek hospital

admission. Psychiatric Services, 47(8), 871

–873.

Larken, G. L., Classen, C. A., Emond, J. A., Pelletier, A. J., &

Camargo, C. A. (2005). Trends in U.S. emergency department

visits for mental health conditions, 1992 to 2001. Psychiatric

Services, 56, 671

–677.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline

personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

Linehan, M. M., & Heard, H. (1999). Borderline personality disorder:

costs, course, and treatment outcomes. In N. Miller, & K.

Magruder (Eds.) The cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy: A

guide for practitioners, researchers, and policy-makers (pp.

291

–305). New York: Oxford Press.

Links, P. S., Heslegrave, R., & van Reekum, R. (1999). Impulsivity:

Core aspect of borderline personality disorder. Journal of

Personality Disorders, 13(1), 1

–9.

MacKinnon, D. P., Warsi, G., & Dwyer, J. H. (1995). A simulation

study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behavioral

Research, 30, 41

–62.

Maser, J. D., Akiskal, H. S., Schettler, P., Scheftner, W., Mueller, T.,

Endicott, J., et al. (2002). Can temperament identify affectively

ill patients who engage in lethal or near-lethal suicidal behavior?

A 14-year prospective study. Suicide and Life-Threatening

Behavior, 32(1), 10

–32.

McGue, M., Slutske, W., & Iacono, W. G. (1999). Personality and

substance use disorders: II. Alcoholism versus drug use

disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67

(3), 394

–404.

Moeller, F. G., & Dougherty, D. M. (2002). Impulsivity and substance

abuse: What is the connection? Addictive Disorders and Their

Treatment, 1(1), 3

–10.

O

’Carroll, P. W., Berman, A. L., Maris, R. W., Moscicki, E. K.,

Tanney, B. L., & Silverman, M. M. (1996). Beyond the tower of

Babel: A nomenclature for suicidology. Suicide and Life-

Threatening Behavior, 36(3), 237

–252.

Oquenda, M. A., & Mann, J. J. (2000). The biology and impulsivity

and suicidality. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(1),

11

–25.

Orcutt, H. K., Pickett, S. M., & Pope, E. P. (2005). Experiential avoidance

and forgiveness as mediators in the relation between traumatic

interpersonal events and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 24(7), 1003

–1029.

Paris, J., & Zweig-Frank, H. (2001). A 27-year follow-up of patients

with borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry,

42, 782

–787.

Pfohl, B., Blum, N., & Zimmerman, M. (1994). Structured interview

for DSM-IV personality: SIDP-IV. Iowa City, IA: American

Psychiatric Publishing.

Preacher, K. J., & Leonardelli, G. J. (2001). Calculation for the Sobel

test: An interactive calculation tool for mediation tests [Computer

software]. Available from

http://www.unc.edu~preacher/sobel/

(March).

Sachs-Ericsson, N., Verona, E., Joiner, T., & Preacher, K. J. (2006).

Parental verbal abuse and the mediating role of self-criticism in adult

internalizing disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 93, 71

–78.

Shafii, M., Carrigan, S., Whittinghill, J. R., & Derrick, A. (1985).

Psychological autopsy of completed suicide in children and

adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 142(9), 1061

–1064.

Shear, M. K., Greeno, C., Kang, J., Ludewig, D., Frank, E., Swartz, H. A.,

et al. (2000). Diagnosis of nonpsychotic patients in community

clinics. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 581

–587.

Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J.,

Weiller, E., et al. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiat-

ric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a

structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-

10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 22

–33.

Sher, K. J., & Trull, T. J. (1994). Personality and disinhibitory

psychopathology: Alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 92

–102.

Skodol, A. E., & Bender, D. S. (2003). Why are women diagnosed

borderline more than men? Psychiatric Quarterly, 74(4), 349

–360.

Trull, T. J., Sher, K. J., Minks-Brown, C., Durbin, J., & Burr, R.

(2000). Borderline personality disorder and substance use

disorders: A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review,

20(2), 235

–253.

Verona, E., & Patrick, C. J. (2000). Suicide risk in externalizing

syndromes: temperamental and neurobiological underpinnings. In

T. E. Joiner, & M. D. Rudd (Eds.) Suicide science: Expanding

the boundaries (pp. 137

–173). New York, NY: Kluwer.

Verona, E., Patrick, C. J., & Joiner, T. E. (2001). Psychopathy,

antisocial personality, and suicide risk. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology, 110(3), 462

–470.

Verona, E., Sachs-Ericsson, N., & Joiner, T. E. (2004). Suicide attempts

associated with externalizing psychopathology in an epidemio-

logical sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 444

–451.

Wilcox, H. C., Conner, K. R., & Caine, E. D. (2004). Association of

alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: An

empirical review of cohort studies. Drug and Alcohol Depen-

dence. Special Issue: Drug Abuse and Suicidal Behavior, 76

(Suppl7), 11

–19.

Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Dubo, E. D., Sickel, A. E., Trikha,

A., Levin, A., et al. (1998). Axis II comorbidity of borderline

personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 39(5), 296

–302.

J Psychopathol Behav Assess (2008) 30:1

–9

9

9

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Biological Underpinnings of Borderline Personality Disorder

No Man's land Gender bias and social constructivism in the diagnosis of borderline personality disor

Biological Underpinnings of Borderline Personality Disorder

Family Experience of Borderline Personality Disorder

No Man s land Gender bias and social constructivism in the diagnosis of borderline personality disor

Borderline Personality Disorder and Adolescence

APA practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Borderline Personality Disorder

Hypothesized Mechanisms of Change in Cognitive Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder

więcej podobnych podstron