How do consumers evaluate risk in

financial products?

Received (in revised form): 20th January, 2005

Kathleen Byrne

has over 20 years’ experience in the insurance industry, spanning life insurance, investment and general insurance. Her

current focus is on lump sum investment products including guaranteed bonds and structured products. She joined Cardif

Pinnacle in 1994, with responsibility for Actuarial, and was Group Actuarial Director prior to her appointment as Managing

Director – Investments in October 2002. She is currently responsible for all aspects of Pinnacle’s investment business from the

design of new products through to service delivery.

Abstract

Decision-making processes consumers use in investing lump sums are

reviewed, focusing on how investment risk is perceived and assessed. Primary research

was undertaken with investment customers to explore the role played in evaluation of

investment risk by risk perceptions and risk propensity. Both the literature review and

the research findings indicate the central role risk perceptions play in financial

decisions. Sitkin and Weingart’s risk model is used as a research framework. Risk

propensity and risk perception were found to be negatively correlated, however, deposit

accounts were selected for investment irrespective of how risky a respondent considered

them to be.

Risk perceptions and expected return were positively correlated for all asset types

apart from property. Further investigation revealed that experts exhibited positive

correlation in risk return judgments but novices showed no correlation. There was no

correlation between risk and return for either novices or experts for property.

Return expectations were positively correlated with investment allocation. Provision of

past performance information appears to create an expectation for future returns around

the same level as past returns. Research findings suggest that outcome history is a

predictor variable, with a Positive outcome history leading to higher risk Propensity. The

level of risk customers are assuming shows a significantly increasing trend.

Keywords Decision making, risk perceptions, financial products, consumer behaviour,

behaviour finance

INTRODUCTION

Falling stock markets over recent years

have led to some financial products

returning less than the initial investment to

consumers when they have matured.

Despite product literature including

information about risk to capital,

consumers appear not to have understood

the risks they took on.

Providers of financial services products

need to investigate how they evaluate

financial products, including how

consumers perceive investment risk, to

ensure that they understand the products

they buy. Decision making within

financial products has not received much

research attention and consumer

understanding of risk within financial

products even less so. These topics are of

practical importance for consumer

understanding of financial products.

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

21

Kathleen Byrne

Cardif Pinnacle,

Pinnacle House,

A1 Barnet Way,

Borehamwood,

Hertfordshire

WD6 2XX, UK.

Tel: +44 (0)20 8207 9226;

Fax: +44 (0)20 8207 4220;

e-mail: kathy.byrne@

cardifpinnacle.com

Literature on decision making and its

relevance to financial decisions is reviewed.

Risk is defined in relation to financial

products and different facets of risk are

discussed. The research methodology

includes a research model, constructs used

and details of the research sample. Results

are presented and practical implications for

product providers are discussed.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Consumer decision making literature in

the context of financial products is

surprisingly scarce. This was noted by

Harrison

1

in this Journal in 2003 and

Goodman

2

explained the actuarial

profession’s recent research into consumer

understanding of risk. Both economists

and psychologists have studied risky

decision making. However, much research

relates to simple choices, often using

gambling devices. There is little coverage

of consumer understanding of financial

risk involved in the evaluation of financial

products.

Decision-making models

Decision making for financial products is

complex because products are intangible,

outcomes are uncertain and financial risk

following a poor decision is significant.

Marketing textbooks

3,4

present a five-stage

model of complex decision making.

Evaluation of competing products is the

stage at which investment risk is evaluated

and quantified and this is the focus of this

paper.

Evaluation of alternatives

Marketing textbooks

3,4

state that

consumers seek certain benefits from the

alternatives they consider. Products are a

series of attributes with different abilities

to produce benefits to satisfy the need

identified. Consumers decide which

attributes are relevant and most important

to them. While different processes may be

used to evaluate products and form

preferences, decisions are rational and

cognitively based.

Risk perceptions play an important role

in evaluating competing products and

behavioural finance authors

5–10

have

demonstrated that risky decision making

can be irrational rather than rational and

cognitively based. In complex decision

making consumers must make choices

between different alternatives and use

heuristics, or rules of thumb, to simplify

the choice they make and in doing so

introduce bias into their decisions.

Heuristics and biases include

representativeness,

5,11–16

availability,

6,17,18

anchoring,

6,16

overconfidence,

19

loss

aversion,

11,17,20

status quo bias,

21,22

hindsight bias,

23

confirmation bias

17

and

mental accounting.

24

Representativeness leads to bias because

people ignore objective information that

does not fit with their stereotype and place

more weight on information confirming

stereotypes. Jordan and Kass

16

investigated

the role of judgmental heuristics in private

investors’ evaluation of risk and return.

Anchoring, representativeness and the

affect heuristic are used by investors and

lead to biases in risk/return judgments.

They found that anchoring effects occur in

expected returns, whereas the affect and

representativeness heuristics affect

perceived investment risk. Both informed

and uninformed groups show judgmental

heuristics, with uninformed investors

showing larger biases.

The way that information is presented

or ‘framed’ means that alternative

descriptions of a decision problem give rise

to different preferences when the same

problem is framed differently.

25,26

What is risk?

The classical economist view of risk is a

situation where the future outcome is

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

22

Byrne

unknown but a probability can be placed

on each possible outcome. Dean and

Thompson

27

put forward two major

concepts of risk, the positivist and

contextualist. A positivist concept of risk is

defined in terms of probabilities based on

objective, verifiable experience and a

contextualist concept of risk is based on

the context in which it is used. Olsen

28

suggests that risk is a continuum taking

into account both the emergent and

multidimensional nature of risk and

concludes that experts tend to focus on

probabilistic models whereas non-experts

use contextual models.

Kahneman and Tversky

6

were the first

to bring behavioural aspects into

economically based risk models. They

found that people appear irrational in

decision making and utility theory does

not fully explain how people make

decisions. They offered an alternative

theory, prospect theory, which assigns

values to gains and losses rather than to

final assets and replaces probabilities with

decision weights. They observed two

effects, first the certainty effect, which

leads to risk aversion in choices for sure

gains and risk seeking in choices for sure

losses. Secondly, the isolation effect where

people generally discard components

shared by all prospects leading to

inconsistent preferences when the same

choice is presented in different formats.

Other models consistent with prospect

theory include Einhorn and Hogarth’s

29

ambiguity model and Harvey’s

17

heuristic

judgment theory.

Sitkin and Pablo

30

identify several

studies that present contradictory results to

those predicted by prospect theory. They

present a model, based on theoretical

analysis, reconciling these contradictions

by examining the usefulness of placing risk

propensity and risk perception in a more

central role than previously recognised.

Sitkin and Weingart

31

test this model in

which risk propensity and risk perception

mediate the effects of problem framing

and outcome history on risky decision-

making behaviour. They conclude that a

mediated model of risk behaviour is more

powerful than one in which the direct

effects of a large number of antecedent

variables are examined individually.

Risk propensity

Several researchers

30,32,33

have investigated

the link between personality and risk

propensity to test whether risk propensity

is a stable personality trait. Their findings

suggest that risk propensity or risk

preference is not a personality trait and

people’s risk perceptions are important in

their propensity to take or avoid risks.

Ensuring people have the right perception

of the level of risk should mean that they

understand the risks they are taking on.

Investment risk

Olsen

28

found that professional investment

managers and experienced individual

investors share a common conception of

investment risk. Jordan and Kass

16

found

that investors’ risk perceptions have four

dimensions:

— downside risk

— upside risk

— volatility

— ambiguity

While there is overlap between these and

Olsen’s findings, there are also differences.

Olsen did not include the ambiguity

dimension of Jordan and Kass, although he

considered economic uncertainty.

Risk and return

Ganzach

34

found that for familiar assets,

risk/return judgments tend to be derived

from past performance as proxies for

current risk perceptions. The relationship

How do consumers evaluate risk in financial products?

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

23

between risk and return judgments is

positive. For unfamiliar assets, risk and

return judgments are derived from global

preferences and the relationship between

risk and return is negative.

Muradoglu

35

looked at experts’ and

novices’ predictions of stock prices.

Investors are positive feedback traders

when presented with a time series

excluding contextual information,

supporting previous research. With

contextual and real-time information,

however, optimism is the norm, bullish

trends are extrapolated and mean reversion

is expected in bear markets only.

Differences are observed in return

expectations and perceived risks due to

contextual information, stock market

trends and expertise.

Summary

People appear far from rational in making

decisions under risk because the complex

nature of financial decisions means that

heuristics used to simplify complex

decisions bring bias into the evaluation.

Risk perceptions appear to play a central

role in financial decisions. The role of risk

propensity, past experience and framing

are also important. Experts appear better

at evaluating investment risk than novices

and the impact of expertise on risk

perceptions is likely to be important. (See

Table 1.)

METHODOLOGY

Research context

The research sample was drawn from

investment consumers so that the results

would be directly applicable to investment

products. The research instrument was

designed to simulate investment decisions

that consumers might expect to make

when considering an investment rather

than using simplified gambling examples

that have often been used to research risky

decision making.

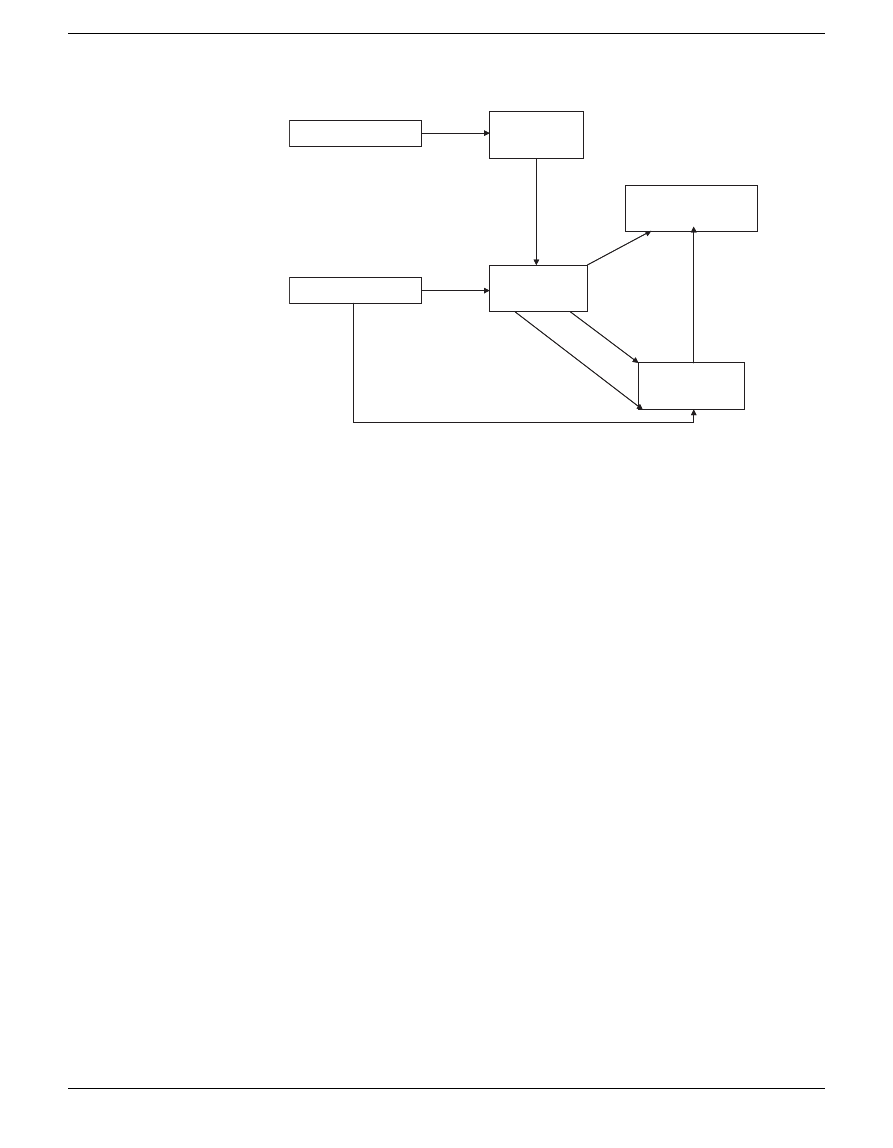

Research model

Role of risk perceptions

Sitkin and Weingart’s model

31

was

developed for management decisions under

risk but appears potentially applicable to

financial decisions as risk perceptions are a

Table 1

Literature summary

Main research findings

Author(s)

Financial decisions use complex decision making

Assael, 1995

3

; Kotler, 2003

4

Evaluation of alternatives

Decisions are rational and cognitively based

Assael, 1995

3

; Kotler, 2003

4

Risky decision making can be irrational

Tversky & Kahneman, 1974

15

; Kahneman &

Tversky, 1979

16

; Thaler, 1980

7

; Slovic, 1991

8

;

Camerer, 1998

9

; Rabin, 1998

10

Framing

Khaneman, 2000

25

; Johnson

et al, 1993

26

Risk

Risk is multidimensional and emergent

Dean & Thompson, 1995

27

; Olsen, 1997

28

;

Jordan & Kass, 2002

16

Risk propensity is not a personality trait

Sitkin & Pablo, 1992

30

; Sitgin & Weingart,

1995

31

; Weber & Milliman, 1997

32

; Weber, Blais

& Betz, 2002

33

Risk/Return relationship is positively correlated for

experts/familiar assets and negatively correlated for

novices/unfamiliar assets

Ganzach, 2000

34

; Muradoglu, 2002

35

Risk propensity and risk perception are key mediating

variables in risky decision making

Sitkin & Pablo, 1992

30

; Sitkin & Weingart,

1995

31

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

24

Byrne

key mediating variable in both types of

decision. For financial decisions, the

expected return and investor expertise are

also expected to be important. This model

is used as a research framework, adapted

to include return and expertise variables

(Figure 1). A positive or negative sign

indicates the direction of each relationship.

The purpose of the research is to test

whether the relationships indicated in the

model exist and their strength. Therefore

the research looks at pairs of relationships

rather than testing the whole model. The

hypotheses to be investigated are also

shown and are now discussed.

H

1

:

Outcome history is positively

correlated with risk propensity

Successful risk-taking experience is

expected to lead to a higher risk propensity

and unsuccessful experience to risk aversion

in future decisions.

H

2

:

Risk propensity is negatively

correlated with risk perception

The higher the level of perceived risk, the

less likely someone is to take that risk and

vice versa. In the investment context, the

higher the level of perceived risk the less

likely someone is to invest and, if they do

invest, the higher the perceived risk the

smaller the investment. Conversely, the

lower the perceived risk, the more they

will invest.

H

3

:

There is positive correlation between

risk perception and expected return for

expert investors

H

4

:

There is negative correlation between

risk perception and expected return for

novice investors

The link between risk perception and a

decision to invest is complicated by an

additional variable, which is the expected

return from the investment. The literature

review shows the rational view is that the

higher the level of risk associated with an

investment then the higher the return the

investor should expect. This is where

Outcome History

Problem Framing

Risk

Propensity

Risk

Perception

How much to

invest

Return

Expectations

Experts

Novices

+

+

+

–

–

–

H3

H4

H2

H1

H5

+

+

+

H1

Source: Adapted from Sitkin and Weingart (1995)

31

Figure 1

Model of the determinants of investment decisions

How do consumers evaluate risk in financial products?

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

25

investment expertise may differentiate

behaviour, with experts following the

rational view of positive correlation

between risk and return and novices

showing negative correlation.

H

5

:

Return expectations will be driven by

past performance information provided

as an anchor

Framing effects are difficult to measure in

complex situations and so the effect of

anchoring on return expectations is the

only framing effect investigated.

Constructs

Experience

Several authors looked at investors’

expertise in their research.

16,28,35

Jordan

and Kass’s construct using knowledge (‘I

know a lot about investing money’) and

experience (‘I am very experienced at

investing’) was used as this was most

relevant to financial products.

Risk perception

This construct encapsulated components

covering both probabilistic and contextual

elements of risk perception:

— Upside risk (potential for good returns)

— Downside risk (potential for loss, not

meeting investment objectives, strength

of regulation)

— Volatility (returns varying over time)

— Feelings (uncertainty, worry)

Risk propensity

This was defined as the likelihood to

engage in a particular activity and in the

investment context was measured by the

amount invested in a specified product.

Research sample

Investment customers of Pinnacle

Insurance plc (Pinnacle) were selected as a

suitable group to study as they had made

or considered a lump sum investment. By

using this customer base bias is introduced,

as Pinnacle’s customers may not be

representative of the whole population of

UK consumers with a lump sum to invest.

Research was conducted by

questionnaire mailed to selected customers.

In order to be able to investigate decision

making across different customer groups,

the customer base was segmented by

customers’ past investment experience with

Pinnacle. Two main product types had

been offered in the past, a guaranteed

insurance bond (GIB) and structured

capital at risk products (Scarps) where the

return was linked to the performance of

specified stock market indices. Falling

stock markets have reduced returns under

Scarps and equities but have not affected

GIB returns as GIBs are fixed rate

products. GIB customers have had good

experience with their investment, while

Scarp customers may have been

disappointed with their returns. A third

customer group, direct customers, was

identified. Some direct customers have

policies with Pinnacle and some do not, so

this group has unknown past experience.

Three customer groups were identified as

follows:

Premier customers

These customers had structured capital

at risk (Scarp) policies (‘Premier

Bonds’) that matured between

November 2003 and March 2004.

GIB customers

These customers had guaranteed

insurance bonds (GIBs) that matured

between June 2003 and June 2004 and

were subject to similar economic

conditions to Premier customers.

Direct customers

These customers have registered to

receive investment offers and invest

directly rather than using an

independent financial adviser (IFA).

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

26

Byrne

Two versions of the questionnaire were

used; version two included past

performance information to test the effect

of anchoring on return expectations. Each

of the sample groups needed to have

approximately 50 respondents so that

results compared across groups would be

statistically significant. A 10 per cent

response rate was expected, therefore

questionnaires were sent to roughly 1,000

customers in each customer group so that

around 50 responses for each version of

the questionnaire would be obtained.

An extract from the customer database

for the three customer groups was

obtained at 30th June, 2004. A report was

run against this database to remove the

following customers:

— Customers who had opted out from

mailings

— Private bank customers, since these

IFAs might object to questionnaires

being sent to their clients

— Customers who had invested over

£100,000 in a single investment

because the aim was to look at the

views of the mass affluent rather than

ultra high net worth customers.

The research instrument

Questions were based on previously tested

questionnaires where possible because these

questions had already been tested for

validity. The questionnaire was divided

into five sections with an introductory

paragraph preceding these. Questions were

structured with a four-point scale so that

respondents had to make a choice on

whether or not they agreed or disagreed

with the statement. The choice was

limited to four, as customers were not

expected to be able to make very fine

distinctions. In some questions a ‘don’t

know’ response was allowed so that

respondents were not forced to make a

choice when they genuinely did not know

how to answer. Appendix 1 shows the

questions relevant to this paper.

RESULTS

There were 371 useable questionnaires, an

overall response rate of 11.24 per cent, with

53 per cent responding on version 1 and 47

per cent on version 2. Table 2 summarises

the responses. Statistical tests were based on

95 per cent confidence intervals.

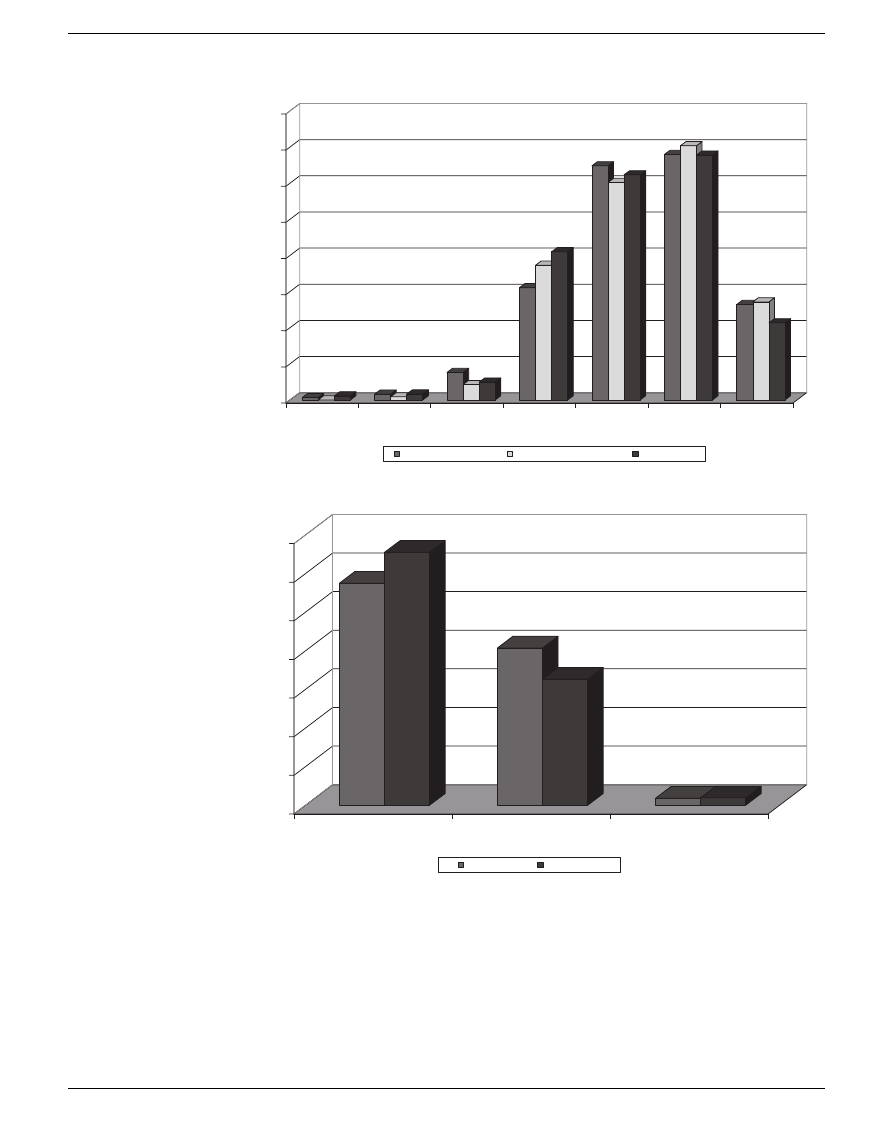

Demographics

Figure 2 shows the age profile of the

respondents compared with the age profile

of the database that was mailed with the

questionnaire. Age was not available in the

Direct database, so comparisons are shown

for the GIB and Premier database against

GIB and Premier respondents and against

all respondents. The old age profile of

respondents reflects the age profile of the

database.

Gender information was available for

both respondents and the full mailing

Table 2

Questionnaire responses

Premier

customers

GIB customers

Direct customers

Customer

group

unknown

Number mailed

622

618

501

500

530

530

Questionnaire version

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

Responses

received

54

66

56

61

63

29

24

18

Responses by

group

120

117

92

42

Response rate

9.68%

11.69%

8.68%

How do consumers evaluate risk in financial products?

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

27

database. Figure 3 shows a comparison

between the database and respondents,

which shows that males are over-

represented in the sample and females are

under-represented compared with the

database population.

Investment expertise

Respondents’ ratings of their knowledge

and experience with investments were

used to calculate an expertise score as the

arithmetic mean of these scores.

0.00%

5.00%

10.00%

15.00%

20.00%

25.00%

30.00%

35.00%

40.00%

%

of population

18 to 29

30 to 39

40 to 49

50 to 59

60 to 69

70 to 79

80 and over

Age Group

GIB & Premier Database

GIB & Premier Respondents

All Respondents

Figure 2

Age profile

0.00%

10.00%

20.00%

30.00%

40.00%

50.00%

60.00%

70.00%

%

of population

Male

Female

Unknown

Gender

Database

All Respondents

Figure 3 Gender profile

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

28

Byrne

The level of investment expertise was

compared between the three customer

groups. One-way ANOVA tests, followed

by the Scheffe procedure, identified

significant differences. Direct customers

have significantly higher expertise levels

than other customers but GIB and Premier

customers have similar expertise.

A grouping variable was set according

to expertise score. Experts (49 per cent of

sample) included respondents who agreed

that they were both knowledgeable and

experienced with investments, while

novices (51 per cent) disagreed with these

statements.

Risk profile

The financial products investors hold in

their portfolios, both now and previously,

were investigated. This allowed the actual

level of risk taken on to be measured for

comparison with risk perceptions and

investment choices. For each respondent

two variables were calculated by

weighting their investment holdings

according to the level of risk, as defined

by an expert, to calculate a current risk

score and a past risk score. These variables

can be compared to see whether past risk

propensity is correlated with current risk

propensity, enabling Hypothesis 1 to be

tested. There was strong correlation

between current and past risk scores (78

per cent), which confirms Hypothesis 1

and suggests that past risk behaviour is an

indicator of future risk behaviour.

A paired sample t test was used to test

the null hypothesis of no difference in

current and past investment risk scores.

This showed that differences were

statistically significant. The mean past risk

score is lower than the mean current risk

score, which suggests that the level of risk

in investment portfolios is increasing over

time. This increase in risk propensity

supports the proposition that successful

risk taking leads to higher risk propensity.

Risk perception and propensity

Respondents completed risk assessments

and risk likelihoods (likelihood of

engaging in each activity) for nine

gambling and simple investment decisions.

For most cases there was negative

correlation between risk likelihood and

risk perception; only one gambling

activity did not show significant

correlation between risk likelihood and

risk perception. This means that the higher

the level of perceived risk the less likely a

respondent is to engage in it.

Investment risk perception

Respondents provided their perception of

risk inherent in four defined financial

products (deposits, property, equities and a

structured capital at risk product) by

answering a series of eight perception

questions for each product. An average

risk perception score was calculated by

product, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from

0.60 to 0.81. Product definitions are shown

in Appendix 2.

Future returns

Expected future returns under the four

financial products assessed for risk were

investigated. Respondents using version 2

of the questionnaire were given past return

information for each product.

Independent sample t tests were used to

test Hypothesis 5 to establish whether

there was a difference in means between

the two questionnaire groups. There was a

significant difference for deposit accounts,

property and Scarps but not for equities.

This may be because the past performance

for equities has been poor and produced

negative returns and performance

information is discarded as it does not fit

with respondents’ future return

perceptions. In all cases, the group given

past performance data has a higher mean

How do consumers evaluate risk in financial products?

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

29

score than the group not provided with

this information. This suggests that for

some investments, providing past

performance information creates

expectations of higher returns than if no

past performance information were

provided. Therefore Hypothesis 5 is

proved for some, but not all, products

tested.

Correlations between risk perception

and future return expectations were

investigated. For all product types except

property, there was significant correlation.

Experts had significant positive correlation

between risk assessment and future return

expectations for all product types except

property, while novices showed no

correlation. These results support

Hypothesis 3 for all product types except

for property, but do not support

Hypothesis 4.

Individual investors who do not have

expertise in property may explain the lack

of correlation. Property is the third least

likely investment to be held, only 26 per

cent of respondents currently hold

property investments while a further 10

per cent have held this type of investment

previously. A chi-squared test shows no

difference in the propensity to hold

property between experts and novices.

Investment decision

Respondents were asked to allocate a

£10,000 investment between the four

financial products used in previous

questions. Table 3 shows the mean amount

allocated between products.

The amount allocated differed between

customer groups, so a one-way ANOVA

test was carried out to test significance.

Differences were significant for deposit

and Scarp allocation but were not

significant for property or equity

allocations. Using a Scheffe procedure, the

differences in means for deposit allocation

are significant between Premier and GIB

customers for deposit allocation, with

Premier customers allocating the least to

this product type.

Interestingly, the difference in allocation

for Scarps was between Premier customers

and Direct customers, with Premier

customers allocating more than any other

customer group. These customers could be

considered to have had bad previous

experience with this product and might

therefore have been expected to be less

likely to invest. Conversely, Premier

customers, having invested in Scarps

previously, are more likely to be familiar

with this investment.

The relationship between risk

perceptions and investment allocation (risk

propensity) was used to test Hypothesis 2

for complex products. Negative correlation

between risk perception and investment

allocation was significant for all investment

types except for deposits. This means that

investors allocate least to the assets they

perceive as most risky. Hypothesis 2 is

proved for all products except deposits.

Further investigation into deposits

showed no significant differences among

experts and novices. Individuals using

deposit accounts for ‘rainy day’ money

might explain this and therefore most

investors allocate some money to a deposit

account irrespective of their risk

assessment. Deposits feature in 89 per cent

of respondents’ portfolios.

Correlation between future return

expectations and investment allocation was

significant for all investment types except

for deposits. The higher the expected

return, the higher the investment allocation.

No significant differences were found

between experts and novices for deposits. A

Table 3

Mean investment allocations

Product

Mean amount allocated

Deposits

£4,723.30

Property

£2,264.56

Equities

£2,259.55

Scarps

£781.23

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

30

Byrne

decision to invest in deposits does not

appear to take account of future return

expectations or level of perceived risk.

DISCUSSION

Investment expertise

Expertise is important for consumer

understanding of risk and the link between

risk and return. Direct customers had

significantly higher expertise scores than

other customers. This may be expected as

direct customers have an active

involvement with investments and buy

direct rather than using an IFA. In

contrast, most other customers are

introduced by an IFA and therefore seek

external advice on investment decisions.

Improving investment expertise,

measured by knowledge and experience,

should enable consumers to make better

investment decisions. Expert consumers

more accurately assess risk and have a

better understanding of risk/return

relationships. Any initiatives to improve

consumer knowledge, understanding and

expertise should be welcomed. This

research highlights the importance of the

FSA’s consumer education remit.

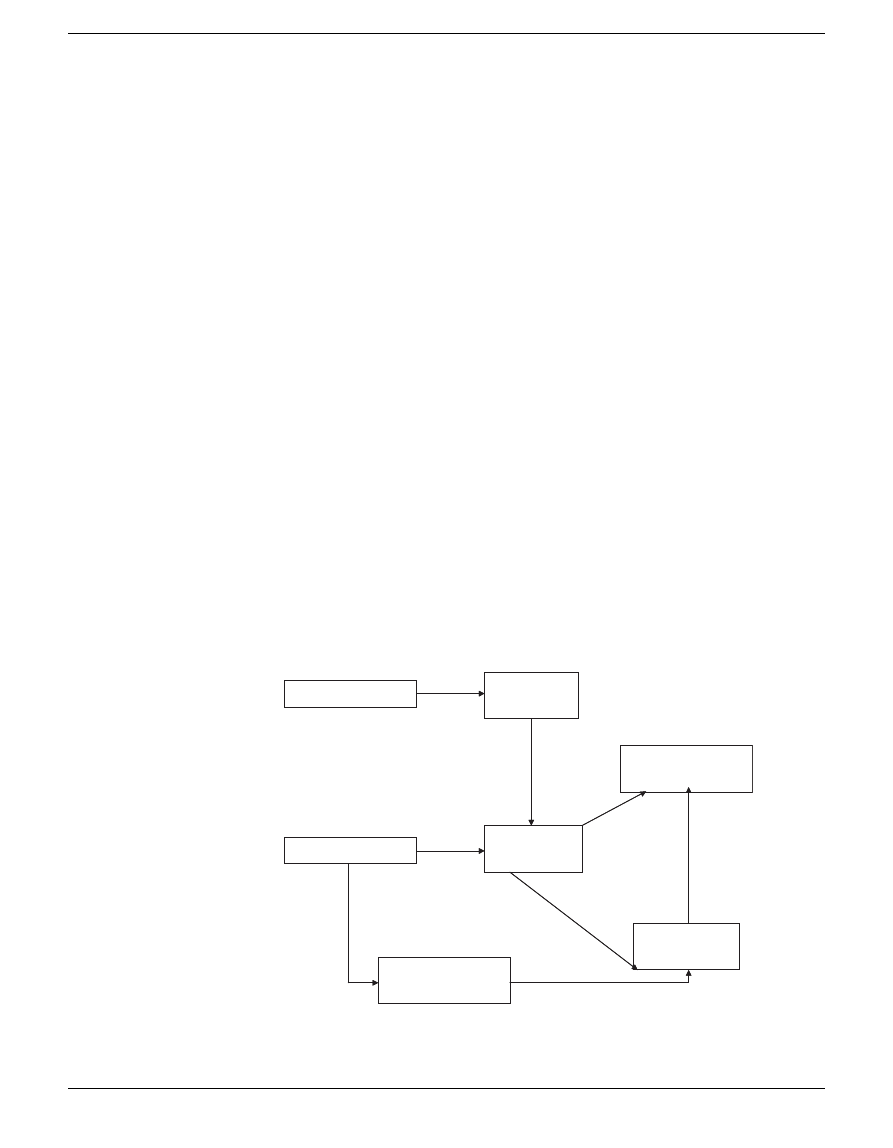

Risk model

The research results generally support the

relationships identified in the model of

determinants of investment decisions

presented in Figure 1.

The portfolio holdings of respondents

support the link between a positive

outcome history leading to a higher risk

propensity. Premier customers, however,

who could be considered as having had an

unsuccessful risk-taking experience, have a

higher propensity to invest in a similarly

risky product than other customer groups.

The returns under Premier policies were

below less risky products such as deposits

but were above higher risk products such

as equities. These customers could consider

the experience to have been successful, but

this is unlikely.

Both literature review and research

Outcome History

Problem Framing

Risk

Propensity

Risk

Perception

How much to

invest

Return

Expectations

Experts

+

+

+

+

+

Past Performance

Information

+

+

+

–

–

+

+

Figure 4

Updated model of the determinants of investment decisions

How do consumers evaluate risk in financial products?

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

31

findings indicate the central role that risk

perceptions play in financial decisions. This

is important because perceptions can be

influenced by how information is

presented. As expected, risk propensity

and risk perception were negatively

correlated with each other for both simple

decisions and also more complex

investment allocation. However, deposit

accounts were selected for investment

irrespective of how risky a respondent

considered them to be. This suggests that

this asset class is seen as a suitable

investment by all investors, at least for

part of their portfolio.

Return expectations were positively

correlated with investment allocation and

this relationship could be added to the

model. A revised model (Figure 4) is

proposed that takes account of this result

and the lack of correlation between risk and

return expectations for novices. The

findings confirm outcome history as a

predictor variable and expected return as an

additional mediating variable, which in turn

is mediated by risk perception for experts.

Limitations

The research sample may not be

representative of investment customers in

general because Pinnacle offers a limited

investment product range. These are low

to medium risk products, so the sample

may be biased towards low risk investors.

The customer age profile is skewed

towards older ages, which is unlikely to be

representative of the age profile of

investors in general.

CONCLUSIONS

The research has shown that the more

expertise a consumer has, the more

accurately they perceive risk and the better

they understand the link between risk and

return. Expertise appears to be important

in consumers’ understanding of the

products they have purchased.

Trends in the UK, such as the move of

pension schemes from defined benefit to

defined contribution, mean that

increasingly financial decisions will be

placed in the hands of consumers who are

likely to be inexperienced and novice

investors. Consumers need financial

knowledge and experience to be properly

equipped to make these types of financial

decision. This means that financial

education will become even more

important in the future. The FSA, the

media and product providers all

potentially have roles to play. The

possibilities of advisers mis-selling or

consumers mis-buying products should

be reduced if consumers are better

informed and understand the risks they

are taking on.

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

32

Byrne

APPENDIX 1: SELECTED QUESTIONS

Q3 Please indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statements

about your knowledge and experience with investments:

Strongly

Agree Disagree Strongly Don’t

agree

disagree

know

I know a lot about investing money

I am very experienced in investing

Q5 Which of the following types of investment products do you currently hold

or have held in the past?

Deposit account

National Savings

Government bonds (gilts)

PEP

Guaranteed insurance bond GIB (Life

Insurance bond)

Property (excluding your own house)

ISA — mini cash

Stocks and shares

ISA — mini stocks and shares

Structured product (no risk to capital) *

ISA — mini insurance

Structured product (capital at risk) **

ISA — maxi stocks and shares

TESSA

Investment trusts

Unit trusts

With profits bond

Questions 6 and 7 used the same statements but required a different choice of responses.

The statements were:

Betting a day’s income at the horse races

Investing 10 per cent of your annual income in a moderate growth unit trust

Lending a friend an amount equivalent to one month’s income

Investing 5 per cent of your income in a very speculative stock

Betting a day’s income on the outcome of a sporting event (eg football match)

Investing 5 per cent of your annual income in a building society deposit

Investing 10 per cent of your annual income in government bonds (gilts)

Gambling a week’s income at a casino

Taking a job where you get paid exclusively on a commission basis

Q6 For each of the following statements, please indicate your likelihood of

engaging in each activity.

Responses: Very unlikely, unlikely, likely, very likely

Q7 For each of the following statements, please indicate your initial reaction of

how risky each situation is.

Responses: Not at all risky, a bit risky, moderately risky, extremely risky

Q8 For each type of investment indicated, please answer the following questions

assuming that you have invested in it.

How do consumers evaluate risk in financial products?

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

33

(Question required responses for each of four products, which were Deposits, Property,

UK Stocks & shares, Structured capital at risk product)

a) This investment bears a high risk of losing money

b) This investment bears a high risk of missing personal investment objectives

c) I feel uncertain about investing in this investment as I feel uninformed about it

d) Investing in this investment also entails good chances to realise higher, above average

returns

e) I think there will be significant variations in performance over time

f) Investors who experience losses with this type of investment are very likely to lose

most or all of their investment

g) I would worry very much if I had invested in this type of investment

h) This type of investment is very well regulated

Responses: Strongly agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly disagree, Don’t know

Q9 For each of the investment types in Q8, please estimate the amount you

would expect back at the end of the next five years assuming you have

£10,000 to invest.

(Question required responses for each of four products, which were Deposits, Property,

UK Stocks & shares, Structured capital at risk product)

(Version 2 of the Questionnaire included the following note:

Note: Over the last five years, if you had invested £10,000 you would have got back on

average £11,716 from a deposit account, £19,918 from property, £8,528 from UK

stocks & shares and £10,420 from a structured capital at risk bond.)

Responses:

Less than £6,000

£6,000 to £7,749

£7,750 to £8,799

£8,800 to £9,999

£10,000 to £11,500

£11,501 to £12,750

£12,751 to £16,000 More than £16,000

Q10 Please allocate an amount of £10,000 between the following investment

types according to your investment preferences:

Investment type

Investment amount

Deposit account

Property

UK Stocks & shares

Structured capital at risk bond

Total

£10,000

Q12 Please indicate your age group

18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80 and over

Q13 Please indicate your gender:

Male

Female

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

34

Byrne

R

EFERENCES

1 Harrison, T. (2003) ‘Understanding the behaviour of

financial services consumers: A research agenda’, Journal

of Financial Services Marketing, Vol. 8, No. 1, p. 6.

2 Goodman, A. (2004) ‘Consumer Understanding of

Risk’, The Actuarial Profession, London, UK.

3 Assael, H. (1995) ‘Consumer Behavior and Marketing

Action’, 5th edn, South-Western College Publishing,

Cincinnati, USA.

4 Kotler, P. (2003) ‘Marketing Management’, 11th edn,

Pearson Education Inc., USA.

5 Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1974) ‘Judgment

under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases’, Science, Vol.

185, pp. 1124–1131.

6 Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979) ‘Prospect

theory: An analysis of decision under risk’,

Econometrica, Vol. 47, No. 2, pp. 263–91.

7 Thaler, R. H. (1980) ‘Towards a positive theory of

consumer choice’, Journal of Economic Behavior and

Organization, Vol. 1, pp. 39–60.

8 Slovic, P. (1991) ‘The construction of preference’,

American Psychologist, Vol. 50, No. 5, pp. 364–71.

9 Camerer, C. (1998) ‘Prospect Theory in the Wild:

Evidence from the Field’, Social Science Working Paper

1037.

10 Rabin, M. (1998) ‘Psychology and economics’, Journal

of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXVI, pp. 11–46.

11 Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1971) ‘Belief in the law

of small numbers’, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 2, pp.

105–110.

12 Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1982) ‘Judgments of

and by representativeness’, in Kahneman, D., Slovic, P.

and Tversky, A. (eds) ‘Judgment Under Uncertainty:

Heuristics and Biases’, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, UK, pp. 84–100.

13 Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1972) ‘Subjective

probability: A judgment of representativeness’,

Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 3, pp. 430–454.

14 Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1973) ‘On the

psychology of prediction’, Psychological Review, Vol.

80, pp. 237–251.

15 Bar-Hillel, M. (1982) ‘Studies of representativeness’, in

Kahneman, D., Slovic, P. and Tversky, A. (eds)

‘Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases’,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 69–

83.

16 Jordan, J. and Kass, K. (2002) ‘Advertising in the

mutual fund business: The role of judgmental heuristics

in private investors’ evaluation of risk and return’,

Journal of Financial Services Marketing, Vol. 7, No. 2,

pp. 129–140.

17 Harvey, J. T. (1998) ‘Heuristic judgment theory’,

Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 47–64.

18 Combs, B. and Slovic, P. (1979) ‘Causes of death:

Biased newspaper coverage and biased judgments’,

Journalism Quarterly, Vol. 56, pp. 837–843.

19 Camerer, C. and Lovallo, D. (2000) ‘Overconfidence

and excess entry — An experimental approach’, in

Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (eds) ‘Choices Values

and Frames’, Cambridge University Press, Russell

Sage Foundation, Cambridge, UK.

APPENDIX 2: INVESTMENT DEFINITIONS

Deposit account:

A bank or building society account that allows you to withdraw

your money without penalty at any time.

Guaranteed insurance bond:

An insurance policy that pays a fixed income each year

and returns your investment at the end of a fixed term. Monthly income, annual income

or growth options are usually available.

Property:

A direct investment in property, which excludes your own house but

includes second homes, buy to let property and commercial property.

Stocks and shares (Equities):

Stocks and shares in UK companies such as BP, Marks

and Spencers, BT etc, also known as equities.

Structured product:

A product where the return is linked to the performance of one

or more stock market indices.

Structured capital at risk product (Scarp):

A product that offers fixed income but

the return of your capital at the end of the term will be reduced if the stock market is

below its starting level at the end of the investment term.

# Kathleen Byrne

How do consumers evaluate risk in financial products?

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

35

20 Baz, J., Briys, E., Bronnenberg, B. J., Cohen, M., Kast,

R., Viala, P., Wathieu, L., Weber, M. and

Wertenbroch, K. (1999) ‘Risk perception in the short

run and in the long run’, Marketing Letters, Vol. 10,

No. 3, pp. 267–283.

21 Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. and Thaler, R. (1991) ‘The

endowment effect, loss aversion and status quo bias’,

Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 193–

206.

22 Samuelson, W. and Zeckhauser, R. (1988) ‘Status quo

bias in decision making’, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty,

Vol. 1, pp. 7–59.

23 Fischhoff, B. (1982) ‘For those condemned to study the

past: Heuristics and biases in hindsight’, in Kahneman,

D., Slovic, P. and Tversky, A. (ed) ‘Judgment Under

Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases’, Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 335–351.

24 Thaler, R. H. (1999) ‘Mental accounting matters’,

Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 12, pp. 183–

206.

25 Kahneman, D. (2000) ‘Preface, in Kahneman, D. and

Tversky, A. (eds) ‘Choices, Values and Frames’,

Cambridge University Press, Russell Sage Foundation,

Cambridge, UK, pp. ix–xvii.

26 Johnson, E., Hershey, J., Meszaros, J. and Kunreuther,

H. (1993) ‘Framing, probability distortions and

insurance decisions’, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty,

Vol. 7, pp. 35–51.

27 Dean, W. and Thompson, P. (1995) ‘The Varieties of

Risk’, Working Paper, University of Alberta, Canada.

28 Olsen, R. (1997) ‘Investment risk: The expert’s

perspective’, Financial Analysis Journal, Vol. 53, No. 2,

pp. 62–66.

29 Einhorn, H. and Hogarth, R. (1986) ‘Decision making

under ambiguity’, Journal of Business, Vol. 59, No. 4,

‘Part 2: The behavioural foundations of economic

theory’ (October 1986), S225–S250.

30 Sitkin, S.B. and Pablo, A.L. (1992) ‘Reconceptualizing

the determinants of risk behaviour’, Academy of

Management Review, Vol. 17, pp. 9–39.

31 Sitkin, S.B. and Weingart, L.R. (1995) ‘Determinants

of risky decision-making behavior: A test of the

mediating role of risk perceptions and propensity’,

Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 38, No. 6, pp.

1573–1582.

32 Weber, E. and Milliman, R. (1997) ‘Perceived risk

attitudes: Relating risk perception to risky choice’,

Management Science, Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 123–144.

33 Weber, E., Blais, A.-R. and Betz, N. (2002) ‘A

domain-specific risk-attitude scale: Measuring risk

perceptions and risk behaviors’, Journal of Behavioral

Decision Making, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 263–290.

34 Ganzach, Y. (2000) ‘Judging risk and return of financial

assets’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, Vol. 83, pp. 353–370.

35 Muradoglu, G. (2002) ‘Portfolio managers’ and

novices’ forecasts of risk and return: Are there

predictable forecast errors?’, Journal of Forecasting, Vol.

21, No. 6, pp. 395–416.

Journal of Financial Services Marketing

Vol. 10, 1 21–36

Henry Stewart Publications 1363–0539 (2005)

36

Byrne

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Excellence in Financial Management Evaluating Financial Performance

Tea consumption and cardiovascular risk in the SU VI MAX study Are life style factors important

How Do You Design

Obrigado how to express your gratitude in Portuguese

Head at risk in LCP

How Do I Look Body Image Percep Nieznany

Evaluation of in vitro anticancer activities

praktikant in financial accounting

How do Drugs?fect Your Health

Dowód przyjęcia środka trwałego do użytkowania, kadrowe, księgowe i in

how do you come school

sumator wielobitoy how do it

how do i set up wds using mikro Nieznany

Leil Lowndes How to Make Anyone Fall in Love with You UMF3UZIGJVMET6TLITVXHA3EAEA4AR3CAWQTLWA

what do you like doing in your free time

How Do You Design

więcej podobnych podstron