"mess you up"

November 2002

THE

CrossFit Journal

IN THIS ISSUE:

The Muscle-up -

page 1

Glycemic Index -

page 1

Stategies for rowing 2000 meters in 7 minutes -

page 7

Glycemic Index

For several decades now, bad science and bad politics

have joined hands to produce what is arguably the

most costly error in the history of science - the low

fat diet. This fad diet has cost millions unnecessary

death and suffering from heart disease,

diabetes and, it increasingly seems, a

host of cancers and other chronic and

debilitating illnesses.

, the esteemed science

writer, has written two brilliant and

highly regarded pieces on exactly this

subject. The first appeared in

just this summer.

A new age is dawning in nutrition: one

where the culprit is no longer seen as

dietary fat but excess consumption of

carbohydrate - particularly refined or

processed carbohydrate. In fact, there’s

an increasing awareness that excess

carbohydrates play a dominant role in

chronic diseases like obesity, coronary heart disease,

many cancers, and diabetes. This understanding comes

directly from current medical research. Amazingly, the

near universal perception that dietary fat is the major

culprit in obesity has no scientific foundation. (See

Taubes, above.)

There’s a family of popular diets and diet books based

on decreasing carbohydrate consumption. Most of them

are excellent.

Chief among these books are Barry Sears’ Enter the

Zone, Michael Eades’ Protein Power, Atkins’ Dr.

Atkins’ Diet Revolution, Cordain’s The Paleo Diet, and

the Hellers’ Carbohydrate Addict’s Diet. Each of these is

an honest and accurate chronicling the effects of the low

fat, fad diet.

(continued on page 5)

The Muscle-up

The muscle-up is astonishingly difficult to perform,

unrivaled in building upper body strength, a critical

survival skill, and most amazingly of all, virtually

unknown.

This movement gets you from under

things to on them (

). Let your

imagination run.

Though containing a pull-up and a dip,

its potency is due to neither. The heart

of the muscle-up is the transition from

pull-up to dip - the agonizing moment

when you don’t know if you’re above

or below.

That moment - the transition - can

last from fractions to dozens of

seconds. At low, deliberate speeds, the

muscle-up takes a toll physically and

psychologically that can only be justified

by the benefit. No other movement can

deliver the same upper body strength.

Period.

This Frankenstein’s monster combination of pull-up

and dip gives the exercise advantages that render it

supreme among exercises as fundamental as the pull-

up, rope climb, dips, push-ups, and even the almighty

bench press.

We do our muscle-ups from rings chiefly because that’s

the hardest place possible.

Here’s how to do a muscle-up on the rings:

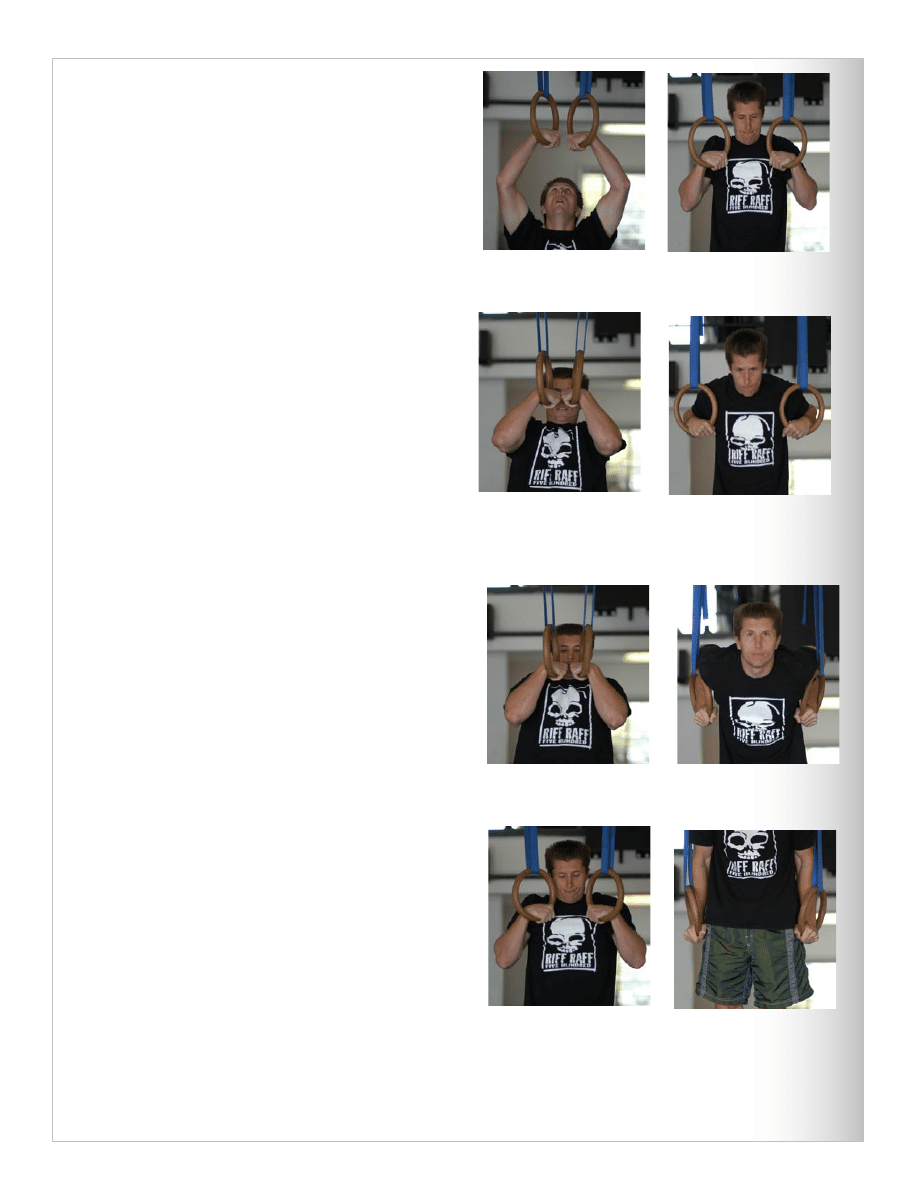

1. Hang from a false grip

2. Pull the rings to your chest or “pull-up”

3. Roll your chest over the bottom of the rings

4. Press to support or “dip”

(continued on page 2)

1

November 2002

It’s that simple. Steps 1 and 3 are where you’ll have trouble

if you do.

From a normal grip roll the meat of the hand over the ring

leaving the thumb on the starting side until the wrist opposite

the thumb is in full contact with the ring - this is a false grip.

It shortens the forearm greatly improving strength.

The false grip is difficult simply because it’s a sufficiently odd

feeling that the beginner rarely believes is what’s expected.

No false grip, no muscle-up. When an athlete can’t get it,

50% of the time they’ve got too much hand on the thumb’s

side of the ring. This part is really very, very easy. On the

other hand rolling your chest over the bottom of the rings is

very, very hard.

Here are some tips for rolling your chest over the bottom of

the rings.

1. Stick your nose as far over the rings as possible

2. Drive your elbows from down in front of you to

up and behind you

3. Keep the rings as close to your body as possible

4. Tighten your gut

5. Have the meat of the thumb trace a line from

collarbone to the armpit, just above the nipple

Ultimately, none of this really helps; you just have to struggle

with it until you get it.

Assuming the grip is O.K. - you’ll know it is if you get deep

bruises on the wrist opposite the thumb - there are two other

common barriers to the muscle-up.

First, not being strong enough. Here’s the litmus: if you can

do fifteen good pull-ups and fifteen good dips then you’re

strong enough. If you can’t, work your pull-ups and dips

overtime until you can do the muscle-up.

If youcan do the pull-ups and dips, your grip is good (you’re

getting bruised wrists) and you’re still unable to get above

rings, then you’re either letting the rings wander away from

your body or you aren’t trying hard enough.

The muscle-up gets noticeably harder with every quarter

inch the ring moves away from the body. Keep the rings in as

close to your body as you can. Only a buddy can tell you if

they’re wandering or not. Typically the struggler has no sense

of where he is.

As weird as it sounds not trying hard enough is common

1. Note the “false grip”.

Without this you don’t

have a chance

5. Watch the elbow’s migration

from pointing down and in front to

pointing back then slightly up

6. Notice Loyd Lewis leaning foward

through the transition - sticking his

nose out over the rings

3. The closer the rings are kept to the

body the easier the muscle-up

7. The head travels from looking up to

foward to down to up again

4. Note the rings rotation from adjacent

in two parallel planes to parallel in one

plane back to parallel in two planes

through a rotation of 180 degrees

8. It’s not readily apparent but the

muscle-up involves a rather potent

ab contraction that “hollows” the

trunk. This makes rolling over

the rings much easier. The motion

reminds us of dodging a “high-in-

side” pitch

2. The hands come together down the

sternum to below the collarbones where

they separate and move towards the

armpits

2

November 2002

among even the most accomplished athletes. Don’t give up on each attempt until you’ve struggled for ten seconds with

the rings at the chest. This part is very hard.

How hard? Not very, really. Gymnastics moves are graded “A” through “E”, “A” being easiest and “E” hardest. The

muscle-up is an “A” move. That’s right, easiest. So it’s easy for gymnasts and nearly impossible for most everyone else.

But, once you get it, anything you can get a finger hold on, you can surmount. You’ll be able to jump for something, catch

it with only two fingers, pull in two more, choke up to the false grip and, “boom!” - you’re on top. Military, police, and

firefighter applications are too obvious to mention.

Less obvious are the martial applications where alternately pulling and pushing from awkward angles is routine. Our Jiu-

jitsu guys recognize at once the utility of strength along these bodylines, as well

as the strength and advantage of the false grip.

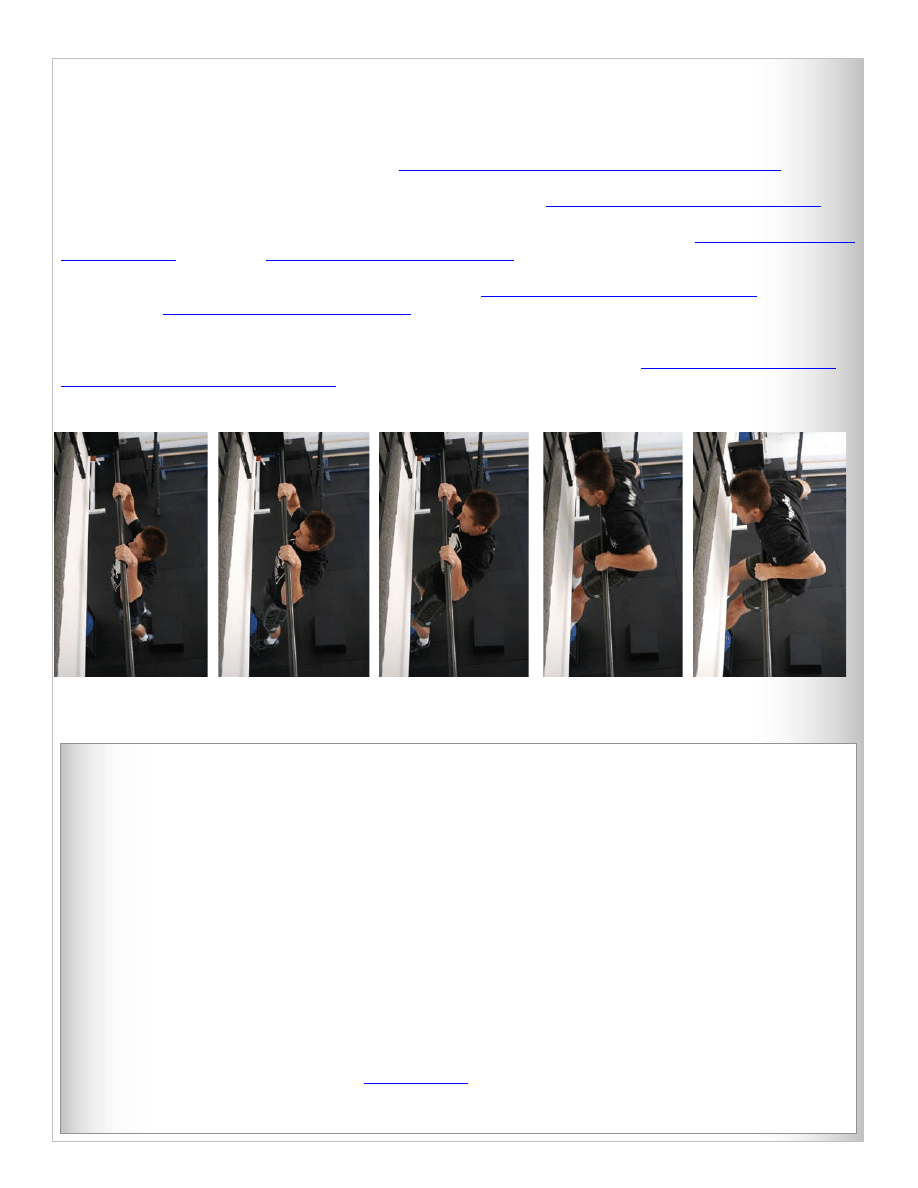

You can assist the muscle-up with an easy push under the rump during the

transition. It’s important for the spotter to push gently, and straight up. The

athlete’s legs will typically rise leaving him in a near-seated position from

which directing a push “up” and not “out” will be easy.

An effective workout would be for two athletes, regardless of ability to perform

the muscle-up - alternately assisting and working - in sets of five reps. Thirty

muscle-ups, each complete to lockout, is a good workout for most people. Fifty

will cover the needs of even elite barbarians.

If you still don’t have rings, you’re running out of excuses. There are options for

every budget and workout facility. See “Ring Buyer’s Guide.”

Rings were a regular feature of

until modern times. Strangely, this

perfect tool for perfecting upper body development has fallen to newer fashions

and a disregard for challenging or even slightly technical elements.

Help reverse this trend and you’ll benefit immensely. So buy some rings, set them up, and use them - starting with the

muscle-up.

Garth Taylor is being assisted by a “Delta No-Tangle Harness, Vest Style” by Sala (651.388.8282) connected overhead to a

block and tackle assembly with a 4:1 purchase by

.

This allows for a near perfect assistance – the line of action is

not altered by the assistance (compare to Loyd Lewis).

In assisting the muscle-up the key is to gently and slowly aid the transition. The challenge is to keep the athlete moving

through the transition but slowly. The Sala vest and block and tackle provide for a method that not only doesn’t alter the

line of action but also gives fantastic tactile feedback to the spotter. You can, by this method, assist perfectly without even

looking at the athlete – the sticking point can be easily felt.

3

November 2002

“Ring Buyer’s Guide”, CFJ, November ‘02

Here are some sources for rings, from a free - standing ring frame suitable for international competition, to a homemade set for

throwing over your pull-up bar or tying to a tree limb.

Spieth Anderson’s “Barcelona Ring Frame” is a classic.

http://www.spiethanderson.com/catalog/gymnastics/gym18.htm

If you’re blessed with space and budget you can get a great Ring Set from AAI.

http://www.gymnasticproducts.com/rings.htm

With less space, but still lucky enough to have tall ceilings you can buy ceiling mounted rings from AAI (

http://www.norberts.net/catalog/2816.pdf

Where budget or space is limited, you can get Lexan rings from AAI (

http://www.gymnasticproducts.com/rings.htm

from Norbert’s (

http://www.norberts.net/catalog/2816.pdf

). This arrangement can be thrown over your pull-up bar or just the right

tree limb.

Anyone can afford this option regardless of budget or facility. Frank Ollis, made a set for $3.25 (

http://www.crossfit.com/cgi-bin/

message/show.cgi?tpc=26&post=18#POST18

).

Here Loyd Lewis is demonstrating the muscle-up on our pull-up bar.

The technique is essentially the same whether the muscle-up is performed on a cliff, tree limb, balcony edge, or the rings.

CrossFit Muscle-up Contest

The competition is to perform as many consecutive muscle-ups as able. Each rep begins from a full hang and ends at full extension. The

count ends on touching the ground - even slightly.

Three natty “CrossFit Muscle-Up Champion T-Shirts” will be given for 1

st

, 2

nd

, and 3

rd

place in each weight division.

Men’s weight divisions:

0-125

126-150

151-175

176-200

201-225

226-250

251+

Every female able to demonstrate a muscle-up receives a T-shirt. (We’ve seen one, Olympian Eva Twardokens). Max reps is female

champion. There are no weight divisions.

Every athlete over fifty able to perform the muscle-up receives a T-shirt.

Submit claims with details of accomplishment to

along with contact information of athlete and any witnesses by

March 1

st

, 2003. Early submissions will be notified of ranking. Videotape, though not required, may be archived on CrossFit.com.

Zoom out showing head to toe.

4

November 2002

Glycemic Index

(continued from page 1)

and they all offer a rational, effective regimen for avoiding dietary ills. For those technically inclined, the mechanism by

which excess carbohydrate causes disease state is known as “hyperinsulinemia.” Hyperinsulinemia is the chronic and

acute elevation of insulin as a result of habitual consumption of excess carbohydrate.

The list of ills linked to hyperinsulinemia is staggering and growing. Just recently

was added to the

probable list of hyperinsulinemia-mediated diseases . The evidence linking excess carbohydrate consumption to

is compelling if not overwhelmingly convincing.

Additionally, excess consumption of carbohydrate may soon be shown to be linked to Alzheimer’s, aging, cancers and

other disease through a process known as “

At any rate, a search on “Google” for “

” reveals hundreds of ills linked to this metabolic derangement.

The rapidly growing awareness of the consequences of elevated blood sugar is one of the more promising avenues of

medical advancement today.

Though frightening, the diseases brought about through hyperinsulinemia can easily be avoided by minimizing

carbohydrate consumption - specifically carbohydrate that gives substantial rise to blood sugar and consequently insulin

levels.

There is a singular measure of carbohydrate that gives exactly this information - “Glycemic Index.”

is

simply a measure of a food’s propensity to raise blood sugar. Avoid high glycemic foods and you’ll avoid many, if not

most, of the ills associated with diet.

Rick Mendosa has published one of the most complete glycemic indices available anywhere with a listing of over

giving values based on glucose’s score of 100.

We can increase the ease and utility of using such a list by dividing commonly eaten foods into two groups – one of high-

glycemic foods, “bad foods”, and one of low-glycemic foods, or “good foods.” This is the rationale behind the CrossFit

Shopping List. See page 6.

You may notice that the “good foods” are typically meats, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and seeds, whereas the bad foods include

many manmade or processed foodstuffs. There are some notable exceptions, but the trend is certainly instructive.

High glycemic foods, or “bad foods”, are typically starchy, sweet, or processed foods like bread, pasta, rice, potato,

grains, and desserts.

More than a few observers have pointed out that low-glycemic foods have limited shelf life and are found on the

perimeter of the grocery store where the high-glycemic foods have a longer shelf life and are typically found within the

grocery store’s aisles.

Though this approach is an oversimplification of much of nutritional science, it has the power to deliver nearly all of what

more detailed and elaborate regimens offer such as those by Sears, Eades, Cordain, Atkins, and the Hellers. Eat more of

the “good foods” and less of the “bad foods” and you’ll garner much of what the more responsible eating plans offer.

Many of our friends have radically transformed their health through this single tool.

5

November 2002

CrossFit Shopping List

“Good Foods”

“Bad Foods”

Acorn Squash

Baked Beans

Beets

Black Eyed Peas

Butternut Squash

Cooked Carrots

Corn

French Fries

Hubbard Squash

Lima Beans

Parsnips

Peas

Pinto Beans

Potato

Refried Beans

Sweet Potato

Turnip

Banana

Cranberries

Dates

Figs

Guava

Mango

Papaya

Prunes

Raisins

Fruit Juice

Vegetable Juice

Bagel

Biscut

Bread Crumbs

Bread

Steak Sauce

Bulgar

Sweet Relich

Cereal

Cornstarch

Croissant

Crouton

Doughnut

English Muffin

Granola

Grits

Melba Toast

Muffin

Noodles

Instant Oatmeal

Pancake

Popcorn

Rice

Rolls

Taco Shell

Tortillas

Udon Noodles

Waffle

BBQ Sauce

Ketchup

Cocktail Sauce

Honey

Jelly

Sugar

Maple Syrup

Teriaki Sauce

Chocolate

Corn Chips

Ice Cream

Potato Chips

Pretzels

Saltine Crakers

Molasses

Apple

Grape

Plum

Shrimp

Mayonnaise

Plain Yogurt

Deli Meat

Ham

Soy Milk

Spirulina

Tempeh

Egg Substitute

Oil

Peanuts

Swordfish

Tuna Steak

Tomato Sauce

Spinach

Carrots

Orange

Pear

Pineapple

Brussel Sprouts

Eggplant

Sauerkraut

Hot Dogs

Chick Peas

Lamb

Pork

Dill Pickles

Soy Beans

Asparagus

Cantaloupe

Strawberry

Peach

Water

Oatmeal

Eggs

Protein Powder

Peanut Butter

Tahini

Olives

Beef

Cheese

Salsa

Black Beans

Kidney Beans

Ground Turkey

Soy Sausage

Chicken

Turkey Sausage

Salmon

Turkey

Canned Tuna

Canned Chicken

Soy Burgers

Cottage Cheese

Almonds

Macadamia Nuts

Avocado

Tofu

Tomato

Lettuce

Onion

Mushroom

Cucumber

Blueberries

Milk

Broccoli

Zucchini

6

November 2002

The CrossFit Journal is an electronically distributed magazine

(emailed e-zine) published monthly by

proven method of achieving elite fitness.

For subscription information go to:

http://www.crossfit.com/shop/enter.html

or

Send check or money order in the amount of $25 to:

CrossFit

P.O. Box 2769

Aptos CA 95001

Strategies for a Seven Minute 2K on the Concept II Rower

Our purpose here is to show specifically how a simple goal - like rowing a seven-minute two thousand meters can

not only be systematically and deliberately approached from multiple protocols, but can generally encourage similar

thinking in pursuing other fitness milestones.

Set the rowing ergometer for two thousand meters, row, and note the time at completion. Repeated regularly, the time to

complete the two thousand meters will fall. Eventually, you may pass under the seven-minute mark and become one of

the “better rowers”. This is one obvious and common approach to training for a 7 minute 2K on a rower (2K/7).

Let’s look at another approach. Set the rower for seven minutes and row, and note the distance on completion. Gradually,

the distance for the seven minutes will increase. Eventually, you may pass the two thousand meter mark and become one

of the “better rowers”.

The two approaches, “distance priority vs. time priority”, represent distinct yet converging processes for reaching the

2K/7.

These two approaches suggest a third: hold the rate constant for as much time or as many meters as possible. With the

“rate priority” efforts, you would hold the 500 meter pace at 1:45 and note when the average 500 meter pace fell under

1:45 by either time or distance. Eventually, you may carry the 1:45 average 500 meter pace for seven minutes at which

point you’ve again become one of the “better rowers”.

Three different roads to the same end - two thousand meters in seven minutes. Each of these methods occurs at different

intensities and within different time domains, and therefore in terms of bioenergetics, they cross-train for the singular

goal of 2K/7. (The order of increasing intensity is “distance priority”, “time priority”, and “pace priority.”)

Three metabolically distinct yet convergent paths to the seven-minute goal offer great psychological and physiological

advantage over any of the individual approaches alone.

Slightly more complicated but extremely effective would be an interval approach where the two thousand meters is

rowed in ten intervals of 42 seconds. Set the rower for intervals of 42 seconds of work followed by 30 seconds of rest. If

you row 10 of these intervals and get 200 meters in each you’ll have experienced the 2K at the seven-minute pace with

the advantage of nine 30-second breaks that stopped the clock.

On the next attempt you could set the rest for only 25 seconds while leaving the work at 42 seconds and see if you can get

200 meters in each of ten intervals. You’ve now rowed the 2K at the seven-minute pace again, but this time you reduced

your resting time by 45 seconds.

(continued on page 8)

7

November 2002

With each successful run where you manage the 200 meters in each of ten intervals you can drop the rest time by 5

seconds on the next workout. Eventually, you’ll be able to eliminate the rest. At that point you’ve achieved the 2K/7,

this time by the interval approach.

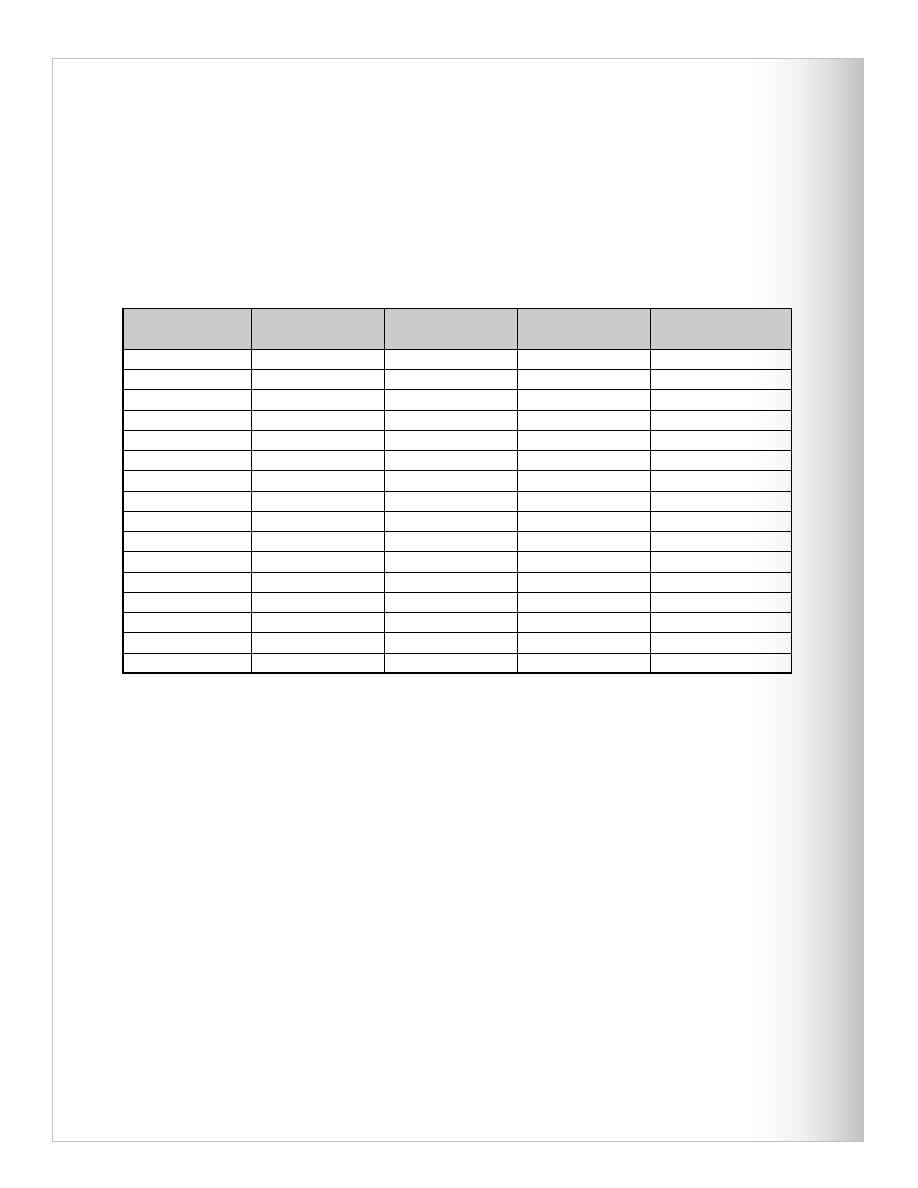

Here’s yet another interval regimen towards the 2K/7. Start with 42 intervals of 10 seconds each followed by thirty

seconds rest. If you’re able to manage 48 meters in each of the 42 intervals, in your next workout try 35 intervals of 12

seconds each followed by thirty seconds rest. If you’re able to manage 57 meters in each of the 35 intervals, then you’re

ready for the next interval in the progression where the work interval increases, the number of intervals diminishes and

the rest remains thirty seconds. The following table shows the progression from easy to tough.

Number of

Intervals

Duration of Work

(Seconds)

Duration of Rest

(Seconds)

Meters in Each

Interval

Total Time for

Workout (min:sec)

42

10

30

48

27:30

35

12

30

57

24

30

14

30

67

21:30

28

15

30

71

20:30

21

20

30

95

17

20

21

30

100

16:30

15

28

30

133

14

14

30

30

143

13:30

12

35

30

166

13

10

42

30

200

11:30

7

60

30

286

10

6

70

30

333

9:30

5

84

30

400

9

4

105

30

500

8:30

3

140

30

667

8

2

210

30

1000

7:30

More important than the particulars of any approach is the variety or breadth of stimulus in moving towards your

target. You’re limited only by your imagination and will power. Each distinct approach adds a unique advantage to your

overall strategy.

This particular goal of two thousand meters in seven minutes is a prominent benchmark in an athlete’s development.

The Concept II Rowing Ergometer is particularly amenable to interval training because of its marvelously flexible

console, allowing for customizable inputs for intervals. However, don’t lose sight of the more general lesson of

incremental, metabolically distinct, and converging methods contributing to an efficient strategy for success.

8

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Crossfit vol 15 Nov 2003 FOOD

Diet, Weight Loss and the Glycemic Index

Mathematics HL Nov 2002 P1 $

Mathematics HL Nov 2002 P2

Crossfit vol 19 Mar 2004 WHAT IS CROSSFIT

Crossfit vol 10 Jun 2003 METABOLIC CONDITIONING

History HS Nov 2002 P1

Mathematics HL Nov 2002 P1

Crossfit vol 16 Dec 2003 COMMUNITY

History HS Nov 2002 P2

Nov 2002 History HL Paper 3

Mathematics HL Nov 2002 P2 $

History HS Nov 2002 P1 $

History HS Nov 2002 P2 $

Diet, Weight Loss and the Glycemic Index

Mathematics HL Nov 2002 P1 $

więcej podobnych podstron