http://www.regent.edu/acad/sls/publications/conference_proceedings/servant_leadership_roundtable/2004pdf/parolini_effective_serv

ant.pdf

R E G E N T U N I V E R S I T Y

Effective servant leadership:

A model incorporating servant leadership and the competing values

framework

Servant Leadership Research Roundtable

Jeanine L. Parolini

Regent University

The concepts of servant leadership and the competing values framework are explored and brought

into a model for effective servant leadership which suggests that servant leaders enhance a firm’s

business performance, financial performance, and organizational effectiveness by prioritizing human

resources, then open systems and internal process, and lastly, rational goals. The concepts of

servant leadership and the competing values framework are joined by shared core concepts and

their focuses on people, values-centered leadership, overcoming hierarchy, and team building in

managing trade-offs. Empirical research around the competing values framework reveals that top

leaders produce the best organizational performance by focusing on people and managing multiple

and competing priorities. Proposed research may help quantify the contribution servant leaders

make to an organization.

In the United States of America, the beginnings of this century have marked a time of public crises. Financial

and sexual scandals have devastated Americans, reducing public confidence in leaders and leaving Americans

ambivalent, angry, and hungry for reform ("Americans Speak", 2002). Reform can come through leaders that

are moral servants. A review of the literature on servant leadership and the competing values framework

reveals shared core concepts between the two including being values-centered, prioritizing people for

effectiveness, being paradoxical in nature, the ability to manage team and trade-offs, and being a response to

historical leadership patterns of hierarchy and autocratic leadership.

The Barna Research Group states that “people’s reactions run the gamut from hostility to indifference—but few

Americans retain a high level of trust in the leading cultural influencers, such as corporate executives”

("Americans Speak", 2002, p. 1). The Barna Group found that only one of the seven roles investigated that of

teacher, held the public’s confidence by just over 50%. Executives of large corporations were at 12% and

elected government officials at 18%. This poll suggests that America’s trust and confidence in major leaders

has dwindled because of these crises.

Barna ("Americans Speak", 2002) suggests these crises are due to a lack of moral leadership character, which

stands in agreement with 55% of adults that suggest greed or immorality motivated the difficulties. Barna

states, “Skills can be learned but character is a reflection of the heart that is formed from a person’s early

years and emerges as they age” (p. 3).

2

Effective Servant Leadership - Parolini

According to Yukl (2002), early leadership studies conducted in the 1930s and 1940s attributed leadership

success to traits including “tireless energy, penetrating intuition, uncanny foresight, and irresistible persuasive

powers” (p. 12). Yukl suggests these studies failed to tie leadership traits to variables that influenced

leadership effectiveness and group performance. Barna ("Americans Speak", 2002) posits that a leader’s

character is the force that allows the leader to move beyond the temptation to grab for power, prestige,

publicity, or other perks that can overpower the commitment to moral virtues and eventually lead to leader

downfall. Barna suggests that leaders must demonstrate character rather than skills or abilities in order to

build back America’s trust.

Servant leadership may offer an answer to America’s leadership dilemma in that morals, ethics, and values on

the part of the leader are central to its success (Graham, 1991; Laub, 2003; Russell, 2001). At the same time,

servant leadership is considered to be fairly new in the field of leadership study and has little empirical

research to support its philosophy (Farling, Stone, & Winston, 1999; Laub, 2003; Russell & Stone, 2002). Laub

suggests that questions as to how to identify it, when it is in use and not in use, and where is the research

base to support it continue to go unanswered. This paper seeks to respond to those questions by providing a

conceptual model that identifies effective servant leadership through the use of the competing values

framework.

As organizations move from managing by instructions, objectives, hierarchy, or autocracy toward managing by

values, different leadership styles are necessary (DiPadova & Faerman, 1993; Dolan & Garcia, 2002). Servant

leaders value serving first then leading as they see to it that people’s highest priority needs are being served in

that followers are becoming “healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, and more likely themselves to become

servants” (Greenleaf, 1977, p. 27). The literature suggests that servant leaders’ skills are influenced by certain

character traits as well as their orientation toward people.

Competing values research empirically shows that effective leaders value people first, then context and

systems, and lastly productive goals (Hart & Quinn, 1993; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1981). Setting these priorities

is empirically linked to maximizing business and financial performance as well as organizational effectiveness.

The model in this paper suggests that as servant leaders bring specific character traits, a certain orientation

toward people, and a set of skills to their prioritization of people first, then context and systems, and lastly

productive goals, they will maximize business and financial performance as well as organizational

effectiveness.

Defining Servant Leadership

Greenleaf (1977) defined a servant leader as servant first in his statement:

It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to

aspire to lead. That person is sharply different from one who is leader first, perhaps because of the need to

assuage an unusual power drive or to acquire material possessions. (p. 27)

In his statement, Greenleaf points out the extreme difference between the servant-first leader and the leader-

first leader. The servant-first leader takes all precautions to make sure other people’s highest priority needs

are being served whereas the leader-first leader may forget others in his or her drive for power and

possessions. It is important to keep this in mind in looking at the variables that must be associated with a

servant leadership model in that servant leaders bring an inner character strength that is stronger than their

drive for power, position, and possessions.

Unfortunately, servant leadership has been confused with weak or subservient leadership. In Collins’ (2001a)

search for how to describe Level 5 Leadership, he and his team almost ventured to call it servant leadership,

but later backed off from the title in concern that it would appear weak or meek without expressing the

strength in humility and fierce resolve in it. Servant leadership is anything but weak or meek and is incorrectly

defined when described this way.

Servant Leadership Research Roundtable – August 2004

3

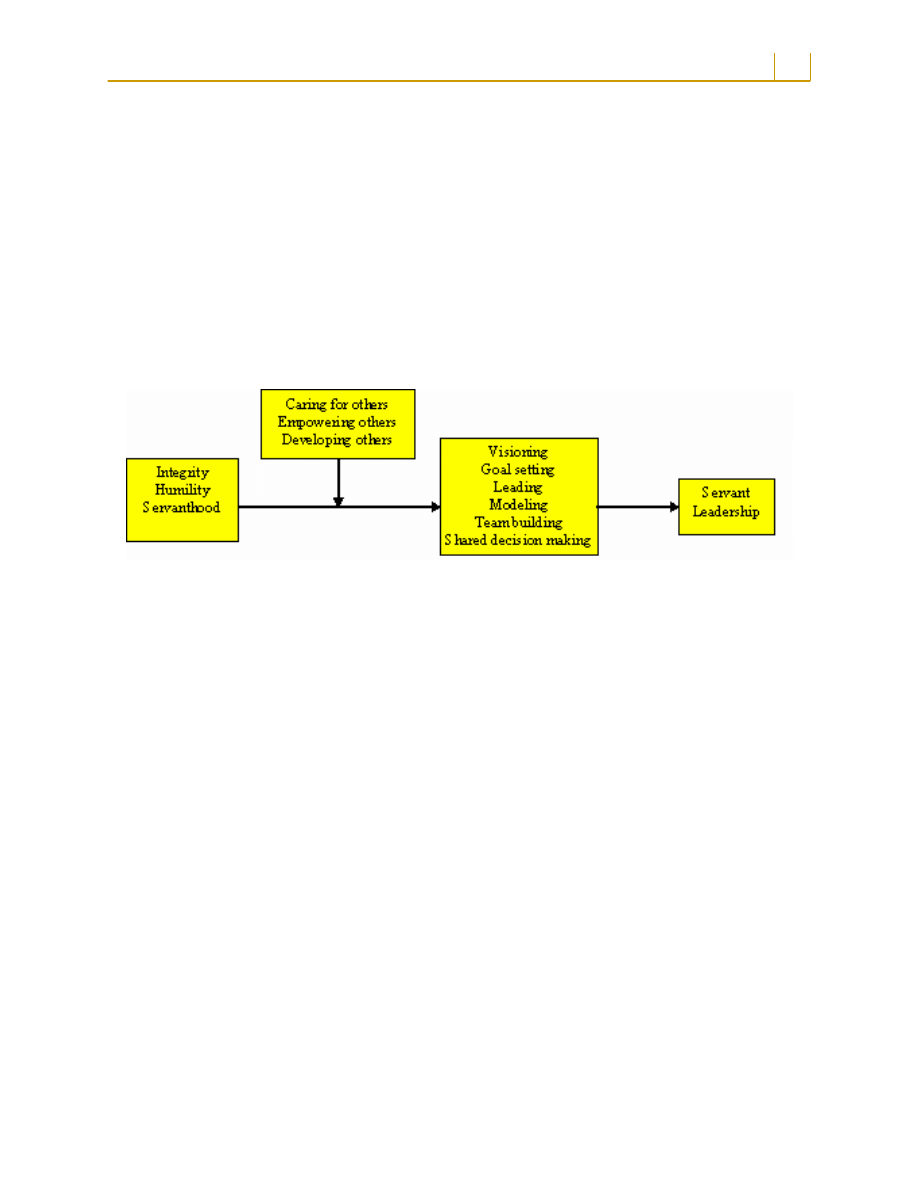

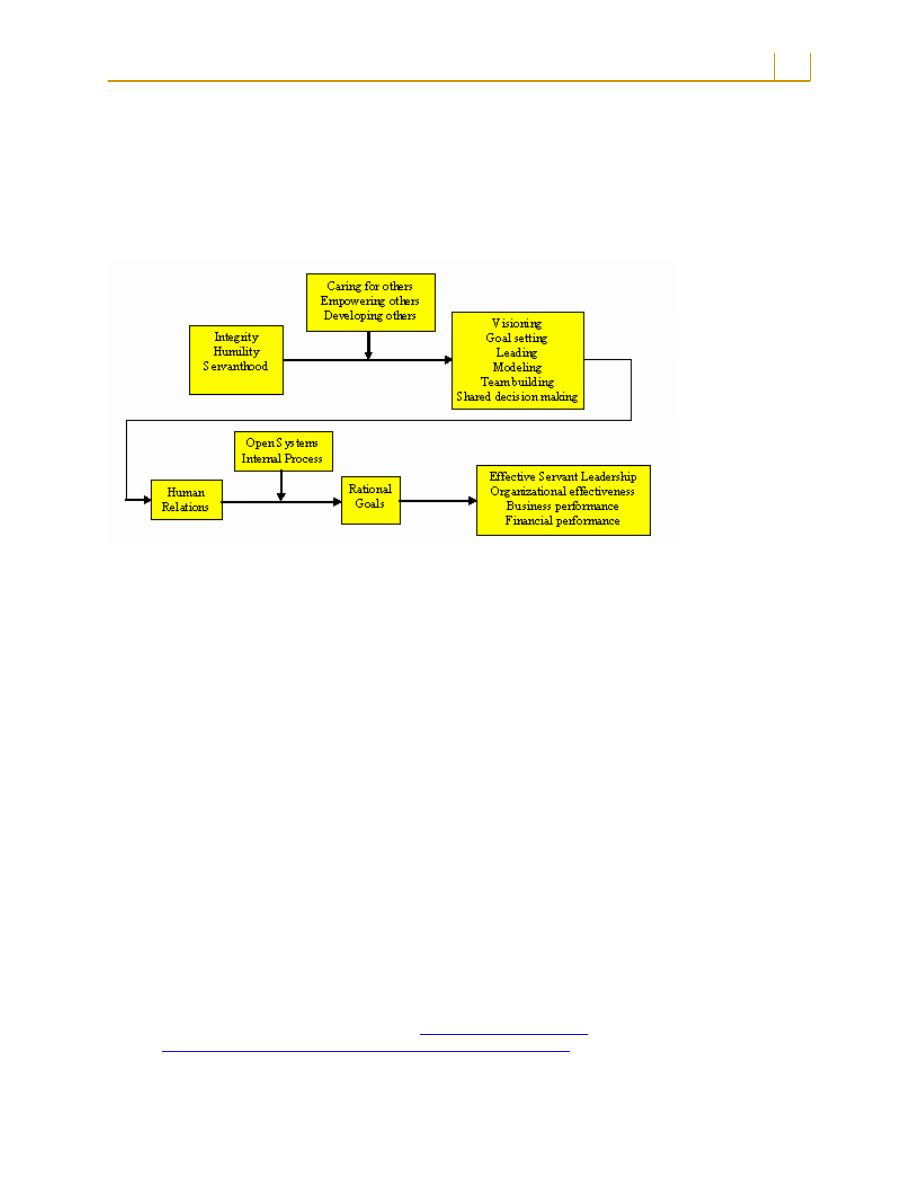

Page and Wong (2000; Russell & Stone, 2002) offer a conceptual model of servant leadership that categorizes

200 items describing servant leadership into 100 attributes and then into 12 subscales. Page and Wong’s 12

categories are similar to the 66-items categorized by Laub, which were later narrowed down to 6 with 18

subsets (Laub, 2003; Page & Wong, 2000). Page and Wong’s model also appears to incorporate the extensive

list described by Russell and Stone. Page and Wong suggest the servant leader can have impact upon society

and culture by bringing specific character traits (integrity, humility, and servanthood) to an orientation toward

people (caring, empowering, and developing), which influence the use of leadership tasks (visioning, goal

setting, and leading) and processes (modeling, team building, and shared decision making) (see Figure 1).

Page and Wong’s factor analysis yielded 8 of the 12 factors including leading, servanthood, visioning,

developing others, team-building, empowering others, shared decision making, and integrity. Dennis and

Winston (2003) conducted a factor analysis which yielded 3 factors including servanthood, visioning, and

empowering others. Based upon both analyses, it seems that the model has some merit.

Figure – 1: Parolini’s model for effective servant leadership using Page and Wong’s conceptual framework for

measuring servant leadership

Page and Wong (2003) describe the servant leader’s character and being in terms of the independent

variables of integrity, humility, and servanthood. Integrity, humility, and servanthood within the heart of the

leader make up the force by which the leader is able to overcome ego and a self-serving agenda in order to

value serving people first.

Integrity

Integrity is defined as the firm adherence to a code of moral values, which results in incorruptibility,

soundness, and completeness in terms of being undivided (Merriam-Webster, 2004). Honesty, which according

to Merriam-Webster is the synonym of integrity, implies a refusal to lie, steal, or deceive and results in fairness

and straightforwardness of action, sincerity, and adherence to the facts. Integrity incorporates aspects of

ethics, values, morals, honesty, and trust (Russell & Stone, 2002). Becker (1998) distinguishes between moral

integrity over personal integrity in that moral individuals are committed to a rational and objective set of

principles that support the greater good over personal subjectivism. He suggests society without moral values

and principles could be subject to a twisted form of integrity based upon personal subjectivism where leaders

have integrity to a set of principles that are out for their own interests and potentially harmful to others, such

as in the case of Adolph Hitler. Clawson (1999; Patterson, 2003) posits that integrity in effective leadership is

based upon the four values of truth-telling, promise-keeping, fairness, and respect for the individual. Lewicki

and Wiethoff (2000) define trust as an individual’s ability to be consistent in words and actions as well as in

the ability to understand and appreciate the wants of others. Integrity is summed up as the leader’s

commitment to an objective set of moral values that result in an inward and outward honesty, trustworthiness,

and fairness that serves the greater good.

Humility

Humility is a display of character that supports leaders in overcoming egotistical tendencies of thought, feeling,

and action. Collins (2001b) describes humility as a duality of inward fierceness and outward modesty that

when combined, refrain one from letting ego interfere with making the best decisions. Hare (1996) describes

humility as a tendency to not over-value one’s self so that the ability to value the worth of others is enabled.

According to Sandage and Wiens (2001), humility is the ability to focus on others, from a position of self-

Published by the School of Leadership Studies, Regent University

4

Effective Servant Leadership - Parolini

acceptance, by keeping one’s abilities in perspective. Humility within the leader counteracts and limits the

negative effects of too much self-interest (Patterson, 2003). Humility enables the leader to truly serve others.

Service

Servant leaders are motivated to serve first then lead (Greenleaf, 1977). Block (1993) posits servant leaders

choose service over self interest. Winston (2003) suggests the desire to serve is motivated by a focus on

serving as compared to a sense of servitude or requirement. Page and Wong’s (2000) servant leadership self-

assessment describes the contentment, enjoyment, willingness, personal sacrifice, fortitude, and fairness that

servant leaders experience as they act in service toward others, and because of this, servant leaders inspire

others to serve. In a broadcast of Dateline NBC (Phillips, 2004), Larry Spears described the toughness and

strength of character that motivates sacrifice and service in servant leaders. This definition of service

describes the leader’s choice and desire to serve, which is part of the leader’s character. If the leader’s choice

and desire is left out of the definition of servant leadership then the underlying motives of a servant leader

could be misinterpreted as weak or subservient. Choi and Mai-Dalton (1998) propose that followers respond to

a leader’s sacrifice and service in reciprocal ways.

The servant leader’s being, comprised of the independent variables of integrity, humility, and service,

influences and is influenced by the moderating variables of caring for, empowering, and developing followers

(Wong & Page, 2003). Buchen (1998) posits that the servant leader has worked though personal egotism so

as to be able to build into people and relationships.

Care

Servant leaders care for others in that they are listeners, understanding, accepting, and empathic (Greenleaf,

1977). Greenleaf posits that leaders naturally serve in making listening an automatic response to people and

problems. Listening helps leaders get to a significant place of understanding. Servant leaders, according to

Greenleaf, accept what the follower brings to the relationship while sometimes refusing to accept some of the

follower’s effort or performance as good enough. Empathy on the part of the leader toward the follower can

help the follower to feel cared about even in the midst of confronting issues of effort or performance. A study

by Kellett, Humphrey, and Sleeth (2002) suggests that empathy, as one of several emotional abilities, is linked

with perceived effective leadership.

Empower

Buchen (1998) describes the reciprocity of power that takes place in the servant leader’s most important

mission of empowering others. Winston (2003) suggests servant leaders empower through providing the

follower with authority, accountability, responsibility, and resources, as well as power, to achieve what the

follower wants in relation to the vision. Melrose (1995) elaborates on empowerment by explaining that it sets

clear expectations, goals, and responsibilities while allowing followers to self-direct and fail. Servant leaders

empower by encouraging followers to do their own thinking and not be overtaken by appealing to power or

position, which actually increases the potential for moral reasoning within the organization (Graham, 1995). In

a case study, Winston found some correlation between empowerment and followers’ perception of being

respected.

Develop

Kotter (2001) posits that the goal of empowerment is to create leaders at multiple levels within the

organization, which is a component of developing others. Buchen (1998) believes that the goal of servant

leaders is to develop other leaders within the organization through dealing with their own ego, empowering and

sharing knowledge, serving first, building relationships, and looking to the future and future generation of

leaders. Servant leaders look for the hidden talents in followers, bring out the best in followers, forgive and

help followers to learn from failures, invest time and energy in equipping followers, and raise up successors

(Page & Wong, 2000).

The servant leader’s care, empowerment, and development of people moderates his or her ability to get things

done through the mediating variables of visioning, goal setting, leading, modeling, team-building, and shared

decision making (Wong & Page, 2003).

Servant Leadership Research Roundtable – August 2004

5

Visioning

The servant leader is both able to inspire vision within the organization and its individual members. Page and

Wong (2000) suggest this ability is measured through a strong sense of personal mission, calling, and values.

Greenleaf (1977) describes servant leaders’ foresight and ability to conceptualize in his statement that they

need to “have a sense for the unknowable and be able to foresee the unforeseeable” (p. 22). The servant

leader is able to provide a strategic vision for the organization as well as inspire, motivate, and move others

toward it, according to Greenleaf. Along with vision for the organization, the servant leader is an empowerer

and developer seeking to inspire followers toward their best fit in fulfilling the vision. Winston (2003) suggests

that servant leaders support followers in finding their purpose and inspire them toward it.

Goal Setting

Servant leaders bring the discipline necessary to set goals in guiding people and the organization toward the

vision. Page and Wong (2000) suggest serving leaders bring focus, discipline, clarity, and realism to goal

setting. Giampetro-Meyer, Brown, Browne, and Kubasek (1998) challenge servant leaders to consider business

goals and efficiency in their leadership, especially considering today’s global market and strict competition.

Servant leaders see their first goal as serving people first (Greenleaf, 1977) and getting the right people on

board (Collins, 2001a). Overall personal values direct the servant leader’s goals, priorities, and performance

(Page & Wong, 2000).

Leading

Servant leaders lead by inspiring and persuading others to move toward the vision, while keeping service at the

forefront of their motives and message. Huey (1994) suggests leaders must derive their influence from values,

which Malphurs (1996) says must come from within the leader in knowing his or her own value system in order

to transmit it through inspiring and persuading others. Servant leaders are effective problem solvers, able to

take input and carefully weigh the options, have a good understanding of what is happening within the

organization, are able to communicate ideas effectively, give power to others, and are able to move different

types of people forward in achieving results (Page & Wong, 2000).

Modeling

Merriam-Webster (2004) defines modeling as forming or planning after a pattern. Kouzes and Posner (1995)

describe modeling as providing a personal visible example for followers as well as a way to instill vision, values,

and ethics into the organization. Briner and Prichard (1998) suggest that the servant leader model attracts

followers into commitment, dedication, discipline, and excellence. Winston (2003) found a correlation between

leader modeling and follower respect for leader values, which implies that followers can focus on leader

ontology as much as task accomplishment in determining whether to follow the leader’s model. Servant

leaders lead by example (Page & Wong, 2000), which demonstrates a value for integrity on the part of the

leader.

Team-building

Servant leaders build community and foster cooperation (Page & Wong, 2000; Spears, 1996). In the servant

lead organization, people work together well in teams and prefer collaboration over competition (Laub, 2003).

Gardner (1990) states, “[S]kill in the building and rebuilding of community is not just another of the

innumerable requirements of contemporary leaders. It is one of the highest and most essential skills a leader

can command” (p. 118). He encourages leaders to develop community that nurtures its members, fosters

trust, respects one another, and has shared values. Page and Wong (2000) add that times of celebration,

creative and constructive ways to work through conflict, and embracing differences and each team member’s

unique contribution are ways to foster teamwork. Gardner posits that good leaders are able to foster trust and

dependency among team members.

Shared Decision Making

Gardner (1990) says, “The taking of responsibility is at the heart of leadership. To the extent that leadership

tasks are shared, responsibility is shared” (p. 152). He goes on to create a picture of how the wider sharing of

tasks and responsibility lower barriers to leaders and begin to offer more leaders the chance to test their skills,

the enjoyment of greater freedom, and the opportunity for increased purpose and responsibility. Gardner

suggests that this sharing of responsibility can actually build self-confidence and inclusion. Greenleaf (1977)

posits that servant leaders share power in decision making. In servant organizations, Laub (2003) describes

Published by the School of Leadership Studies, Regent University

6

Effective Servant Leadership - Parolini

that people are encouraged to provide leadership at all levels of the organization in that power and leadership

are shared so that most people can contribute to decisions.

Figure 1 sums up the outcome of servant leadership as bringing humility, integrity, and servanthood to caring

for, empowering, and developing others in living out the skills of visioning, goal setting, leading, modeling,

team-building, and shared decision making.

Defining the Competing Values Framework

Quinn developed the competing values framework to describe perceptions that are the foundation of social

action (Hunt, Hosking, Schriesheim, & Stewart, 1984). He suggests that social action is reflective of three core

value dimensions, which support four paradigms or worldviews. Quinn’s structured analysis indicates that

people tend toward one main paradigm of action more than any of the others.

At the same time, Quinn and MacGrath (1982) have not meant to suggest one single-solution framework for

organizational success. In fact, they argue that organizational development has suffered from single-solution

frameworks that are not comprehensive enough to explain the complexities of organizational processes. The

authors believe the competing values framework can meet the needs for complex diagnostic and change

processes within organizations or smaller groups.

Initially, Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983) created a program of research to investigate organizational

effectiveness criteria by asking successive panels of experts in organizational theory to make judgments about

the similarity or dissimilarity of effectiveness criteria. In the exploratory phase, six of the seven experts

presented published papers on the topic and were asked to participate in a two-stage judgment process to

reduce Campbell’s (1977) list of 30 organizational effectiveness criteria. Using multidimensional scaling, three

dimensions emerged for measuring organizational effectiveness. At the conclusion of the exploratory study,

another panel of experts was used in conjunction with multidimensional scaling to attempt to replicate the

results with a larger, more diverse group of active theorists and researchers.

Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983) found that researchers shared an implicit theoretical framework on

organizational effectiveness and could be sorted according to the three value dimensions of focus, structure,

and means and ends. Focus is the value for an internal (micro) emphasis on the well being and development of

people within the organization or an external (macro) emphasis on the well being and development of the

organization itself. The second value dimension of structure is defined as an emphasis on stability on one end

of the continuum to an emphasis on flexibility on the other end. The last dimension, means and ends, on one

end has to do with an emphasis on the processes that will reach the end goal (e.g., planning and goal setting),

to the other end of productivity. The three value dimensions resulted in naming four constructs of

effectiveness.

Quinn (1988) describes the human resources model as focused on internal flexibility with cohesion, morale,

and training as the means to reaching development of human resources. Teamwork is important to this model

as concern for people, commitment, discussion, participation, and openness are valued.

The open systems model is also high on flexibility but from an external perspective in that organizational

flexibility and readiness are focuses to reach growth and resource acquisition (Quinn, 1988). Quinn posits that

insight, innovation, and adaptation are valued in an attempt to secure external support, resource acquisition,

and transformational growth.

The rational goal model is externally focused to ensure a competitive position in that accomplishment,

productivity, profit, and impact are valued (Quinn, 1988). Planning, goal clarification, direction setting and

decision making processes are encouraged to gain control in maximizing output, productivity, and efficiency.

The internal process model is internally focused on information management and communication to reach

stability, continuity, and control. Quinn (1988) suggests that measurement, documentation and management

of information are central to the internal process model.

Servant Leadership Research Roundtable – August 2004

7

The competing values framework has been well received and has empirical research to support it.

Organizational effectiveness research has tended to impose values systems on research and concepts

whereas the competing values approach brings values choices to the forefront and engages organizations in

making conscious choices in diagnosis and change to reach greater effectiveness (Rohrbaugh, 1983). In using

the tool for diagnosis and change, Quinn and McGrath (1982) found that “operating managers are particularly

drawn to this tension-based framework” (p. 470) and quickly adopt the language and ability to interpret their

profile (DiPadova & Faerman, 1993).

Quinn and Cameron (1983) discussed the relationships between stages of development in organizational life

cycles and organizational effectiveness and found the competing values framework to help predict the

changes in major criteria of effectiveness as young organizations develop through their life cycles. Organization

theorists and researchers are finding that leaders must assume multiple contradictory roles to meet the

emerging needs of organizational lifecycles and changes (Buenger, Draft, Conlon, & Austin, 1996; Denison,

Hooijberg, & Quinn, 1995; Rohrbaugh, 1981; Sendelback, 1993).

Buenger et al. (1996) confirm the existence of the framework within organizations and suggest that value

patterns differ within environmental and technological contexts, indicating the need for value tradeoffs based

upon where the organization needs to go. Researchers have found support for use of the competing values

framework in understanding, comparing, and evaluating organizational cultures as well as establishing

organizational direction (Brown & Dodd, 1998; Hooijberg & Petrock, 1993; Howard, 1998; Panayotopoulou,

Bourantas, & Papalexandris, 2003; Sendelback, 1993)

The framework has also been used to explain how managers and leaders can allow their strengths to put them

at risk by getting trapped in one area of the model while the organization needs to attend to another set of

values (Quinn, 1988). Quinn states:

The more that success is pursued around one set of positive values, the greater will be the pressure to take

into account the opposite positive values. If these other values are ignored long enough, crisis and

catastrophe will result. (p. 72)

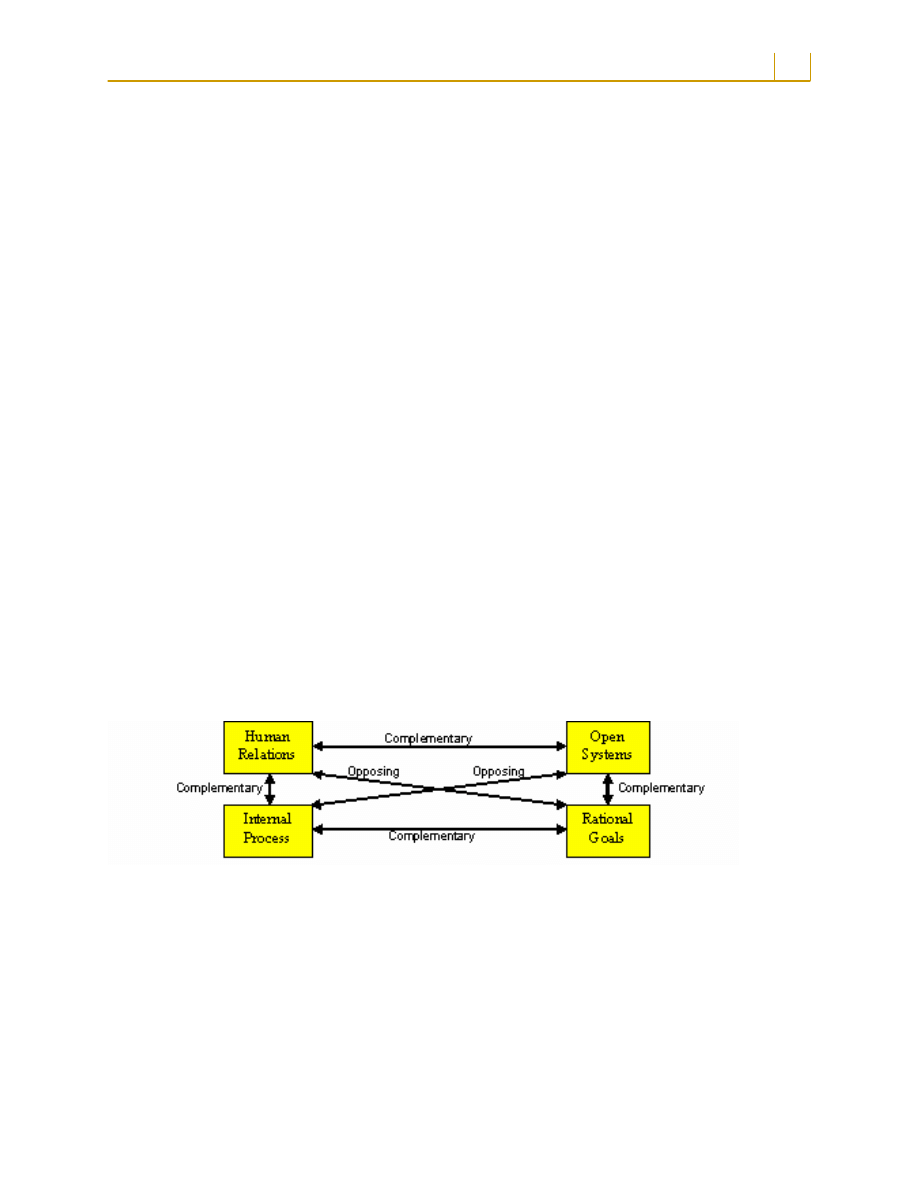

In fact, Quinn found the models to be interwoven. He found one model to be the opposite of one of the others

and a complement to the two that remain (see Figure 2). During a staff development time, the author of this

paper took 58 staff members through Quinn’s values questionnaire and grid to find that this was true with 57

staff members or 98% of the staff.

Figure 2. Quinn’s theory on the complementary and oppositional nature of the competing values framework

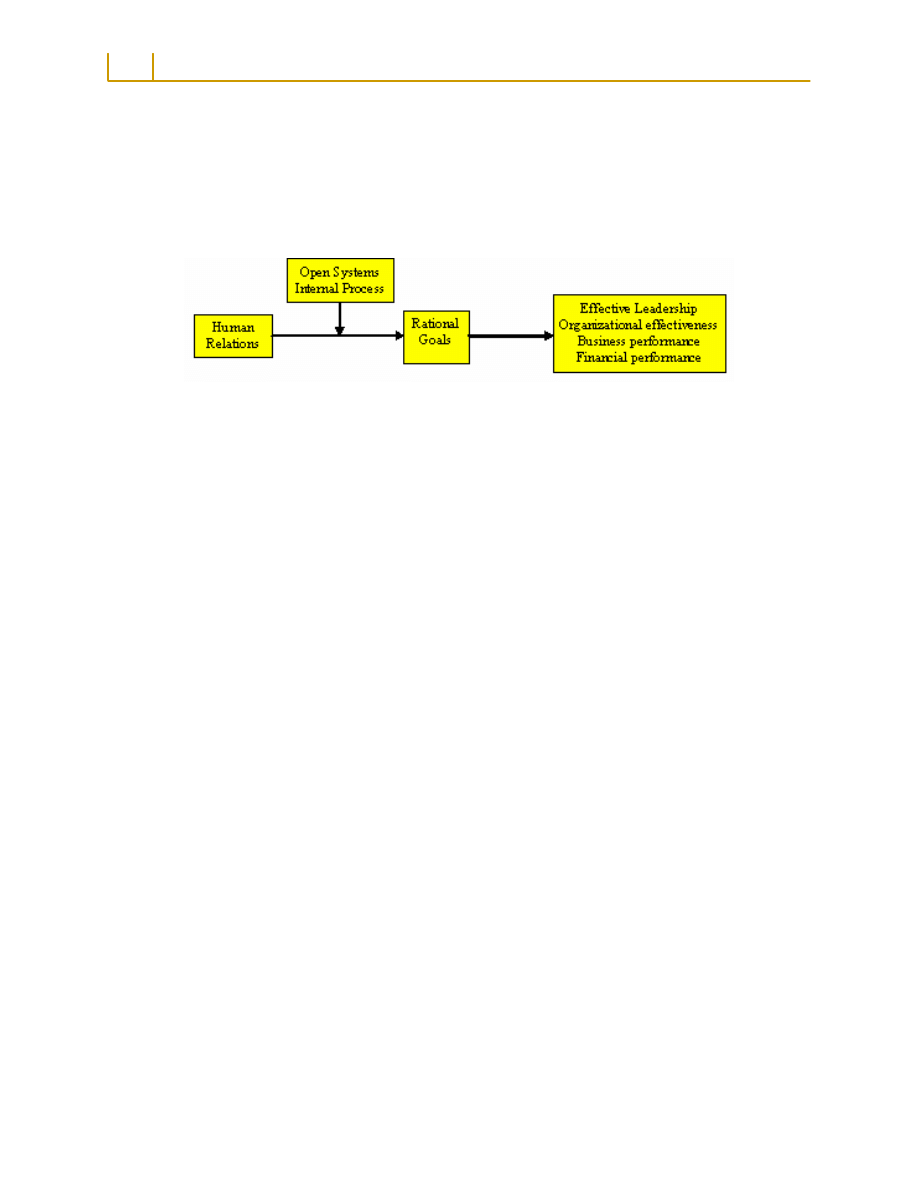

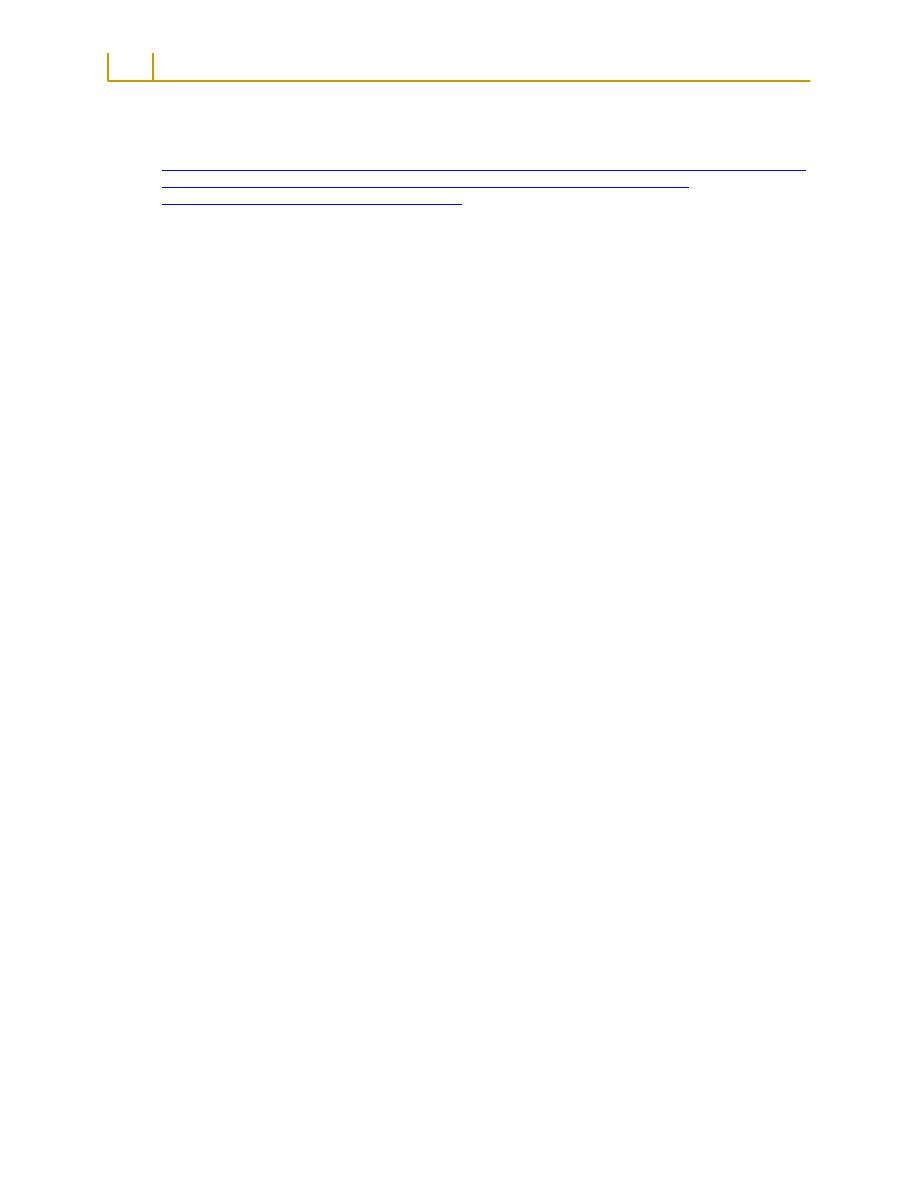

Hart and Quinn (1993) used the framework to show that CEOs with the capacity to play multiple, competing

roles produce the best corporate performance. The moderator or human resources model was the only one of

the four which predicted all three dimensions of performance including business and financial performance as

well as organizational effectiveness. The vision setter or open systems model was predictive of business

performance and organizational effectiveness whereas the analyzer role or internal process model was also

predictive of both but less than the vision setter. Surprisingly, although executives who responded most

frequently played the taskmaster or rational goal role, it was not predictive of performance on any dimension.

Hart and Quinn’s research of the 916 top managers using Venkatraman and Ramanujam’s (1986) framework

for evaluating firm performance, reveals that those managers that focus on people were found to perform best

in terms of business and financial performance as well as organizational effectiveness. Additional research

suggests effective leadership comes through valuing and prioritizing human resources (Brown & Dodd, 1998;

Published by the School of Leadership Studies, Regent University

8

Effective Servant Leadership - Parolini

Denison et al., 1995; Greenleaf, 1977; Panayotopoulou et al., 2003; Polleys, 2002; Sendjaya & Sarros, 2002).

The research proposes that those leaders that embrace multiple values tensions by prioritizing human

resources first, then internal processes and or open systems, and lastly rational goals direct the organization

toward its best performance in terms of business and financial performance as well as organizational

effectiveness (Hart & Quinn, 1993; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1981) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effective leadership based on Hart and Quinn’s research

The Integration of Servant Leadership and Competing Values

Dolan and Garcia (2002) posit that organizations are moving from managing by instructions and objectives to

managing by values. A system of values is vital to organizational integrity and growth (Dolan & Garcia, 2002;

Edgeman & Scherer, 1999; Rohrbaugh, 1983). Both servant leadership and the competing values framework

bring the core values and worldview of the leader to the surface. This paper suggests, through the use of Page

and Wong’s (2000) conceptual model, that servant leaders bring the values of integrity, servanthood, and

humility to their leadership.

Leader character and integrity is the ability to hold to a set of rational values and live them out, enhancing

them as knowledge increases (Becker, 1998). Both servant leaders and effective leaders, through research

using the competing values framework, act from a consistent awareness of the greater needs of people and

the organization in choosing the best alternatives (Denison et al., 1995; King, 1994; Lee & Zemke, 1993;

Pepper, 2003; Pollard, 1997; Quinn, Hildebrandt, Rogers, & Thompson, 1991; Rohrbaugh, 1981; Sendjaya &

Sarros, 2002; Yang & Shao, 1996).

As organizations support the importance of managing by values, there is a trend toward flatter organizational

structures and the need for facilitators rather than “bosses” (Dolan & Garcia, 2002). The gap between the two

groups—labor and management—is being closed and the barriers that have kept hierarchical levels separate

are being broken down (DiPadova & Faerman, 1993). Instead of looking to the old paradigms of leadership

which include dynamic, charismatic, force-of-personality characteristics, Polleys (2002) states, “The call for

servant leaders looks instead to traits that flow naturally from deeply held beliefs about the worth of persons”

(p. 121). Both servant leaders and effective competing values leaders recognize the importance of

empowering, team building, and shared decision making to manage all the needs of today’s organizations.

Over the years, observers have become sensitive to the nature of change, contradictions, and chaos in

effective management and organizational behavior (Cameron & Quinn, 1988). Both the terms servant leader

and competing values hold paradoxes within their definitions. Managing paradox and trade-offs is key to

effective leadership today (Buenger et al., 1996; Quinn, 1988) Van de Ven and Poole (1988) describe paradox

as “the simultaneous presence of two mutually exclusive assumptions or statements; taken singly, each is

incontestably true, but taken together they are inconsistent” (p. 21). The need to manage paradox, competing

roles, and competing values has caused the emergence of team in that a team of people is required to meet

all of these emerging demands (DiPadova & Faerman, 1993; Martin & Simons, 2002; Yang & Shao, 1996).

Today’s leaders are being required to diligently develop their human resources so as to meet these emerging

needs (Brown & Dodd, 1998; Panayotopoulou et al., 2003). Servant leaders manage paradox and trade-offs by

developing and empowering others on their team to help manage all the competing values.

The following hypotheses predict how effective servant leadership is carried out in organizations as well as how

it can be most effective to the organization.

Servant Leadership Research Roundtable – August 2004

9

Hypothesis 1: Servant leaders are defined by their ability to bring integrity, humility, and servanthood

into caring for, empowering, and developing of others in carrying out the tasks and processes of visioning, goal

setting, leading, modeling, team building, and shared-decision making.

Hypothesis 2: Servant leaders first prioritize human resources, then open systems and internal

processes, and lastly, rational goals in bringing the best overall business performance, financial performance,

and organizational effectiveness to their firms.

Figure 4. Parolini’s model for effective servant leadership using Page and Wong’s conceptual framework and

the competing values framework

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper seeks to further explain the specific character, people, task, and process traits associated with

servant leadership, as well as how effective leadership is defined through the use of the competing values

framework. Two hypotheses are suggested for further research to confirm that effective servant leaders bring

these skills to their leadership in valuing human resources first, then open systems and internal processes,

and lastly, rational goals to ultimately contribute to the firms business performance, financial performance,

and organizational effectiveness.

Further research is suggested by analyzing 10 organizations from these three aspects: (a) evaluating their

leadership from the perspective of servant leadership; (b) evaluating their organization from the perspective of

the competing values framework; and (c) analyzing their business and financial performance, as well as

organizational effectiveness using Venkatraman and Ramanujam’s (1986) framework. Servant leadership

would be investigated using both qualitative and quantitative research in performing interviews as well as

using Page and Wong’s (2000) Revised Servant Leadership Profile or Laub’s (2003) Organizational Leadership

Assessment. Qualitative research would be performed through the use of interviews and analysis around

Quinn’s (1988) tools to measure competing values. A quantitative assessment would be provided through one

of Quinn’s tools or developed from the qualitative interviews. Organizations’ records would be analyzed based

upon Venkatraman and Ramanujam’s framework to determine business and financial performance as well as

organizational effectiveness. All 3 sets of information would be further analyzed on the 10 organizations to

investigate servant leadership in the context of living out the priorities of competing values and how this

affects firm performance.

From the perspective of this author, this research could define effective servant leadership in a way that would

contribute to a greater understanding of its value upon the organization’s performance.

References

Americans speak: Enron, WorldCom and others are a result of inadequate moral training by families. (2002,

July 22). Retrieved March 6, 2004, from

bin/PagePressRelease.asp?PressReleaseID=117&Reference=B

Published by the School of Leadership Studies, Regent University

10

Effective Servant Leadership - Parolini

Becker, T. E. (1998). Integrity in organizations: beyond honesty and conscientiousness. Academy of

Management Review, 23(1), 154-162.

Block, P. (1993). Stewardship: Choosing service over self-interest. San Francisco: Berett-Koehler.

Briner, B., & Pritchard, R. (1998). More leadership lessons of Jesus: A timeless model for today's leaders.

Nashville, TN: Broadman and Holman.

Brown, F. W., & Dodd, N. G. (1998). Utilizing organizational culture gap analysis to determine human resource

development needs. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 19(7), 374-382.

Buchen, I. H. (1998). Servant leadership: A model for future faculty and future institutions. The Journal of

Leadership Studies, 5(1), 125-134.

Buenger, V., Draft, R. L., Conlon, E. J., & Austin, J. (1996). Competing values in organizations: Contextual

influences and structural consequences. Organizational Science, 7(5), 557-576.

Cameron, K., & Quinn, R. E. (1988). Organizational paradox and transformation. In R. E. Quinn & K. Cameron

(Eds.), Paradox and Transformation: Toward a Theory of Change in Organization and Management

(pp. 2-18). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Ballinger Publishing.

Campbell, J. P. (1977). On the nature of organizational effectiveness. In P. S. Goodman & J. M. Pennings

(Eds.), New Perspectives on Organizational Effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Choi, Y., & Mai-Dalton, R. R. (1998). On the leadership function of self-sacrifice. Leadership Quarterly, 9(4),

475-501.

Clawson, J. G. (1999). Level three leadership: Getting below the surface. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Collins, J. (2001a). Good to great. New York: HarperCollins.

Collins, J. (2001b). Level 5 leadership: The triumph of humility and fierce resolve. Harvard Business Review,

79(1), 67-76.

Denison, D. R., Hooijberg, R., & Quinn, R. E. (1995). Paradox and performance: Toward a theory of behavioral

complexity in managerial leadership. Organizational Science, 6(5), 524-540.

Dennis, R., & Winston, B. E. (2003). A factor analysis of Page and Wong's servant leadership instrument.

Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 24(8), 455-459.

DiPadova, L. N., & Faerman, S. R. (1993). Using the competing values framework to facilitate managerial

understanding across levels of organizational hierarchy. Human Resource Management, 32(1), 143-

174.

Dolan, S. L., & Garcia, S. (2002). Managing by values: Cultural redesign for strategic organizational change at

the dawn of the twenty-first century. The Journal of Management, 21(2), 101-118.

Edgeman, R. L., & Scherer, F. (1999). Systemic leadership via core values deployment. Leadership &

Organization Development Journal, 20(2), 94-98.

Farling, M. L., Stone, G. A., & Winston, B. E. (1999). Servant leadership: Setting the stage for empirical

research. Journal of Leadership Studies(Wntr-Spring), 49-69.

Gardner, J. W. (1990). On leadership. New York: The Free Press.

Giampetro-Meyer, A., Brown, T., Browne, S. J. M. N., & Kubasek, N. (1998). Do we really want more leaders in

business? Journal of Business Ethics, 17(15).

Servant Leadership Research Roundtable – August 2004

11

Graham, J. W. (1991). Servant-Leadership in organizations: Inspirational and moral. Leadership Quarterly,

2(2), 105-119.

Graham, J. W. (1995). Leadership, moral development, and citizenship behavior. Business Ethics Quarterly,

5(1), 43-55.

Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. New

York: Paulist Press.

Hare, S. (1996). The paradox of moral humility. American Philosophical Quarterly, 33(2), 235-242.

Hart, S. L., & Quinn, R. E. (1993). Roles executives play: CEO's, behavioral complexity, and firm performance.

Human Relations, 46(5), 543-574.

Hooijberg, R., & Petrock, F. (1993). On cultural change: Using the competing values framework to help leaders

execute a transformational strategy. Human Resource Management, 32(1), 29-50.

Howard, L. W. (1998). Validating the competing values model as a representation of organizational cultures.

International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 6(3), 231-251.

Huey, J. (1994). The new post-heroic leadership. Fortune (February 22), 42-50.

Hunt, J. G., Hosking, D.-M., Schriesheim, C. A., & Stewart, R. (1984). Leaders and Managers: International

Perspectives on Managerial Behavior and Leadership. New York: Pergamon Press.

Kellett, J. B., Humphrey, R. H., & Sleeth, R. G. (2002). Empathy and complex task performance: two routes to

leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 13, 523-544.

King, S. (1994). What Is the Latest on Leadership. Management Development Review, 7(6), 7-9.

Kotter, J. P. (2001). What leaders really do. Harvard Business Review, 79(11), 85-91.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (1995). The leadership challenge. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Laub, J. (2003). From paternalism to the servant organization: Expanding the organizational leadership

assessment (OLA) model. Paper presented at the Regent University Servant Leadership Roundtable,

Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Lee, C., & Zemke, R. (1993). The search for spirit in the workplace. Training, 30(6), 21-29.

Lewicki, R. J., & Wiethoff, C. (2000). Trust, trust development, and trust repair. In M. Deutsch (Ed.), The

Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice (pp. 86-107). San Francisco, California: Jossey

Bass.

Malphurs, A. (1996). Values-driven leadership: Discovering and developing your core values for ministry.

Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

Martin, J., & Simons, R. (2002). Managing Competing Values: Leadership Styles of Mayors and CEOs.

Australian Journal of Public Administration, 61(2), 65-75.

Melrose, K. (1995). Making the grass greener on your side: A CEO's journey to leading by serving. San

Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Merriam-Webster. (2004). Retrieved March, 2004, from

.

Published by the School of Leadership Studies, Regent University

12

Effective Servant Leadership - Parolini

Page, D., & Wong, P. (2000). A conceptual framework for measuring servant-leadership. Retrieved March 7,

2004, from

http://216.239.41.104/search?q=cache:AqQWgg0gLQsJ:www.twu.ca/Leadership/ConceptualFrame

workforServantLeadership.pdf+a+conceptual+framework+for+measuring+servant-

leadership,+page+and+wong&hl=en&ie=UTF-8

Panayotopoulou, L., Bourantas, D., & Papalexandris, N. (2003). Strategic human resource management and

its effects on firm performance: an implementation of the competing values framework. International

Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(4), 680-699.

Patterson, K. (2003). Servant leadership: A theoretical model. Paper presented at the Regent University

Servant Leadership Roundtable, Virginia Beach Virginia.

Pepper, A. (2003). Leading professionals: A science, a philosophy and a way of working. Journal of Change

Management., 3(4), 349-356.

Phillips, S. (Writer) (2004). Can humility, faith be good for business. In NBC (Producer), Dateline NBC. USA:

NBC News.

Pollard, C. W. (1997). The leader who serves. Strategy & Leadership, 25(5), 49-51.

Polleys, M. S. (2002). One university's response to the anti-leadership vaccine: Developing servant leaders.

Journal of Leadership Studies, 8(3), 117-131.

Quinn, R. E. (1988). Beyond Rational Management. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass.

Quinn, R. E., & Cameron, K. (1983). Organizational Lifecycles and shifting criteria of effectiveness: Some

preliminary evidence. Management Science, 29(1), 33-51.

Quinn, R. E., Hildebrandt, H. W., Rogers, P. S., & Thompson, M. P. (1991). A competing values framework for

analyzing presentational communication in management contexts. Journal of Business

Communication, 28(3), 213-233.

Quinn, R. E., & McGrath, M. R. (1982). Moving beyond the single-solution perspective: The competing values

approach as a diagnostic tool. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 18(4), 463-472.

Quinn, R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1981). A competing values approach to organizational effectiveness. Public

Productivity Review, June, 122-140.

Quinn, R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values

approach to organizational analysis. Management Science, 29(3), 363-367.

Rohrbaugh, J. (1981). Operationalizing the competing values approach: Measuring performance in the

employment service. Public Productivity Review (June), 141-159.

Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). The competing values approach: Innovation and effectiveness in the job service. In R. H.

Hall & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Organizational Theory and Public Policy.Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Russell, R. F. (2001). The role of values in servant leadership. Leadership & Organization Development

Journal, 22(2), 76-83.

Russell, R. F., & Stone, G. A. (2002). A review of servant leadership attributes: developing a practical model.

Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 23(3), 145-157.

Sandage, S. J., & Wiens, T. W. (2001). Contextualizing models of humility and forgiveness: A reply to Gassin.

Journal of Psychology and Theology, 29(3), 201-216.

Servant Leadership Research Roundtable – August 2004

13

Sendelback, N. B. (1993). The competing values framework for management training and development: A tool

for understanding complex issues and tasks. Human Resource Management, 32(1), 75-99.

Sendjaya, S., & Sarros, J. C. (2002). Servant leadership: Its origin, development, and application in

organizations. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 9(2), 57-64.

Spears, L. (1996). Reflections on Robert K. Greenleaf and servant-leadership. Leadership & Organization

Development Journal, 17(7), 33-38.

Van de Ven, A. H., & Pool, M. S. (1988). Paradoxical requirements for a theory of organizational change. In R.

E. Quinn & K. Cameron (Eds.), Paradox and Transformation: Toward a Theory of Change in

Organization and Management (pp. 19-63). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Ballinger Publishing.

Venkatraman, N., & Ramanujam, V. (1986). Measurement of business performance in strategy research: A

comparison of approaches. Academy of Management Review, 11, 801-814.

Winston, B. E. (2003). Extending Patterson's servant leadership model: Coming full circle. Paper presented at

the Regent University Servant Leadership Roundtable, Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Winston, B. E. (2003). Servant leadership at Heritage Bible College: A single case-study.Virginia Beach, VA:

Regent University.

Wong, P., & Page, D. (2003). Servant leadership: An opponent-process model and the revised servant

leadership profile. Paper presented at the Regent University Servant Leadership Roundtable, Virginia

Beach, Virginia.

Yang, O., & Shao, Y. E. (1996). Shared leadership in self-managed teams: A competing values approach. Total

Quality Management, 75(5), 521-535.

Yukl, G. A. (2002). Leadership in organizations. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Published by the School of Leadership Studies, Regent University

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

How to be an Effective Group Leader

How to be an Effective Group Leader

Time Mastery How Temporal Intelligence Will Make You a Stronger More Effective Leader 1

ties, leaders and time in teams strong interference about network structure effect on teamt vialibil

Time Mastery How Temporal Intelligence Will Make You a Stronger More Effective Leader

Self Leadership and the One Minute Manager Increasing Effectiveness Through Situational Self Leaders

Self Leadership and the One Minute Manager Increasing Effectiveness Through Situational Self Leaders

Istota , cele, skladniki podejscia Leader z notatkami d ruk

Leaders

Market Leader 3 Intermediate exit test

Fallow the Leader

Effect of long chain branching Nieznany

[30]Dietary flavonoids effects on xenobiotic and carcinogen metabolism

Market Leader 3 Intermediate entry test

Market Leader 3 Intermediate progress test 01

ISO128 22 leader and reference lines

Effect of Kinesio taping on muscle strength in athletes

Basic setting for caustics effect in C4D

więcej podobnych podstron