C

H

A

P

T

E

R

12

P

LANNING THE

I

NSTALLATION

T H O M A S A. D O O L E Y A N D

J E R A L D R. R O U N D S

THE PROCESS OF PLANNING

Planning is one of the most important parts of any project and is particularly crit-

ical in construction. One of the characteristics of construction is that it is not

repetitive. Although specific activities such as pulling cable or making termina-

tions appear to be repetitive, each is done under different circumstances. The

cumulative result of these small differences is that jobs differ considerably. As a

result, each job must be planned in detail to take its unique characteristics into

consideration.

In manufacturing, prototypes are designed and manufactured to test the

design and the manufacturing procedures. When mistakes and oversights occur,

another prototype is developed to solve the problems. This process is repeated

many times over until both the product and the process of making that product

are flawless, at which time the product goes into production.

In the construction industry, you do not have that luxury. Designers must

design correctly the first time. Constructors must build right the first time. Errors,

either in design or construction, are costly to repair or replace and cause time

delays. Some errors are hidden and do not become obvious until the system is

operating. Then, the mistakes become not only costly and time-consuming, but

129

are disastrous to those who depend on a fully operational and properly working

system.

The only way to produce a quality job is to avoid errors, omissions, and mis-

takes by properly planning and by establishing correct installation procedures. A

side benefit of the planning process, of course, is that it improves the efficiency of

installation, which results in higher profits for a contractor. Preplanning of every

aspect of fiber optic installation is not an option; it is a necessity.

MEASURING FOR CONDUIT PULLS

Planning for proper cable lengths is extremely important in fiber optic installa-

tion for two reasons. The most important is that splices cause loss in both signal

quality and strength—this should be avoided. In fact, most designers specify

point-to-point or device-to-device runs to avoid needless signal loss due to

splices. The second reason, especially important to the contractor, is that splices

cost time and money.

Measurements must be taken by an experienced field hand who understands

the importance of correct and accurate measurements. Often, this is done by the

project engineer or the job site superintendent.

There are three ways to measure the path to be used for the fiber. They are

listed from least to most desirable.

1. Measurements taken from the set of prints. This works if you want to

invest in a great deal of extra material. The objective of design drawings

is to show generally where runs are supposed to be located. However, it

is virtually impossible for the designer to anticipate all field conditions,

and it is not the designer’s intent to do so. Thus, taking accurate mea-

surements from the design drawings is not possible and results in runs

that are, at best, marginally long or short. Long pieces of fiber must be

recut and short pieces are wasted.

2. Field measurements taken with a wheel. A site visit with a measuring

wheel and a set of drawings will yield much better accuracy. Certain

characteristics of the job site are given perspective with a field visit that

are not obvious from inspection of the drawings alone. During the site

visit, the drawings can be verified for accuracy, installation details such

as pulling locations can be noted, changes such as variations in align-

ment or elevation can be identified, obstacles that might hinder the pull

can be discovered, and termination locations can be recorded.

3. Measuring with measurement/pull tape. By far the most accurate and

efficient method of measurement is with measurement/pull tape (some-

times called mule tape). This is a flat ribbon, consecutively numbered in

feet, that is usually made with polyester or aramid yarn and sometimes

130

CHAPTER 12 — PLANNING THE INSTALLATION

coated with plastic for waterproofing. It comes in different lengths and

pull strengths.

Completing the measurement process requires adding extra length for

splices, terminations, and future access coils, if specified. The amount of addi-

tional cable needed for splicing depends on site conditions, splicing method used,

and long range plans for cable usage. Termination needs only about 7 to 10 feet

of additional cable beyond the place the terminal will be mounted. Access or

repair coils generally range in length from 30 to 50 feet per span. A good guide-

line is to allow 1 percent extra for outside plant cable and 5 to 7 percent extra for

inside cable.

SPLICING

Fusion splicing cannot be done in explosive environments such as manholes.

Therefore, each end coming into the splice that will finally end up in the manhole

will have to have enough length to reach a tent or van near the manhole where

the splice will actually be made. Usually, about 30 feet of extra length should be

added for each side of the splice—resulting in additional 60 feet of cable.

Mechanical splicing can be done inside manholes. Mechanical splices require

only about 10 feet of overlap, instead of the 60 feet for a fusion splice. Remember

that these measurements are in addition to whatever length will be required to

properly rack the cable within the manhole.

TERMINATIONS

When terminating fiber, it is important to place the terminal in a safe, noncon-

gested area. If the end user has no preferences, place the terminal as close as pos-

sible to the fiber optic transmission equipment. It is most important to protect the

exposed fibers, so choice of a termination location must consider a working envi-

ronment that allows adequate working space.

EFFICIENT PULLING

When installers first become involved in fiber optic installations, they can easily

become overconfident about how much cable length can be successfully pulled at

one time. This is probably because of the small size and weight of fiber optic

cable. It is better to divide a pull in half, or even thirds, usually at corners or pull

boxes, than to fail in pulling a long run.

A pulling operation must be discontinued when the pulling tension reaches

the cable limit. The discontinued pull will have to be aborted, the cable pulled

back out and replaced on the reel, and the pull started again, either with shorter

CHAPTER 12 — PLANNING THE INSTALLATION

131

runs or better lubrication or both. The cable may be reused if the pull or extrac-

tion has not damaged it.

Every effort must be made to plan the pull so that pulling locations have

plenty of work space. The knowledgeable designer will designate several appro-

priate locations for breaking up the pull. The installer must ensure that if the

designer has not indicated where multiple pulls are necessary, he or she can deter-

mine appropriate locations for intermediate pulls before work is begun in the

field. It is better to tie up one lead technician before the pulling starts than the

whole crew after it has begun.

Most point-to-point pulls can be accomplished by crews of two or three peo-

ple. One person pays the cable off the reel and into the duct in order to reduce tail

load (the term used to designate that force required to get cable off the reel and

into the duct). One or two people pull at the other end. The size of crew is deter-

mined by considerations such as:

Length of pull

Total degrees of bend

Tail loading

Use of lubricant

Use of power pulling equipment

When planning to start a pull, the installer must make sure there is enough

time to finish the job the same day. It is unwise to leave half a reel of cable, worth

anywhere from $5,000 to $375,000, lying around in unsecured areas. If a reel

must be left exposed to the public, strong consideration should be given to assign-

ing a security guard to watch over the reel. An occasional investment of $75 or

$100 to avoid theft of an expensive reel of cable, to say nothing of the distur-

bance to the job if the cable is gone when installers arrive to begin work in the

morning, is a wise investment

Exact terminating locations must be identified in advance. This obvious

though often overlooked step can lead to costly mistakes if forgotten. The cable

must be pulled all the way to where it will be terminated, not just into the room.

The designer should provide a fold-flat diagram (which results from folding out

the walls of the room as if they were the sides of a box hinged at the intersections

of the walls and the floor) for each terminating room as a part of the initial plan-

ning walkout.

ADEQUATE DUCT SPACE

Current industry practice, outside telephony, tends not to utilize available duct

space very efficiently. As a result, one often finds a 1/2-inch fiber cable as the only

cable in a 4-inch duct. As a matter of good design, cable should fill approxi-

mately 60 to 70 percent of the available duct space.

132

CHAPTER 12 — PLANNING THE INSTALLATION

Since it is difficult to pull cable into a duct that is already occupied, it is very

important to detail, on the print, where the different media will be pulled. Since

most fiber cables are 3/4-inch or smaller in diameter, for efficient use, the larger

3- or 4-inch diameter conduits should be subdivided with innerducts.

Innerduct is flexible, nonmetallic conduit that is pulled in multiples into the

main conduit. It is made of polyethylene and comes with a pull rope already

installed within it. Innerduct serves a threefold purpose:

Subdividing the main duct

Protecting the fiber cable

Reducing friction

The inside of the innerduct is designed to let the cable glide smoothly within

it. This is accomplished by the use of special coatings and by the physical proper-

ties of the inner wall. Corrugated innerduct is the most popular form because of

its flexibility. A 3-inch conduit can be subdivided with up to four 1-inch

innerducts; up to six 1-inch innerducts can be placed in a 4-inch conduit.

Innerduct not only allows the initial fiber installation to be effectively accom-

plished, but allows expansion capabilities to be built into the system. This can

provide great return on investment if there is any expectation of future expansion

of the fiber system.

INITIAL PLANNING WALKOUT

Prior to the start of cable pulling, a planning walkout should be performed by the

project engineer, the lead technician, and the project superintendent. The project

engineer, responsible for system design, will be well aware of the customer’s

needs. The lead technician, an experienced fiber installer who will not necessarily

be the one who will do the installation, has the responsibility to plan and to

answer as many questions as possible before the crew is on site. The superinten-

dent can provide general project information and needs to know as much as pos-

sible about the installer’s activities to coordinate with other trades and activities

in the vicinity of the installation.

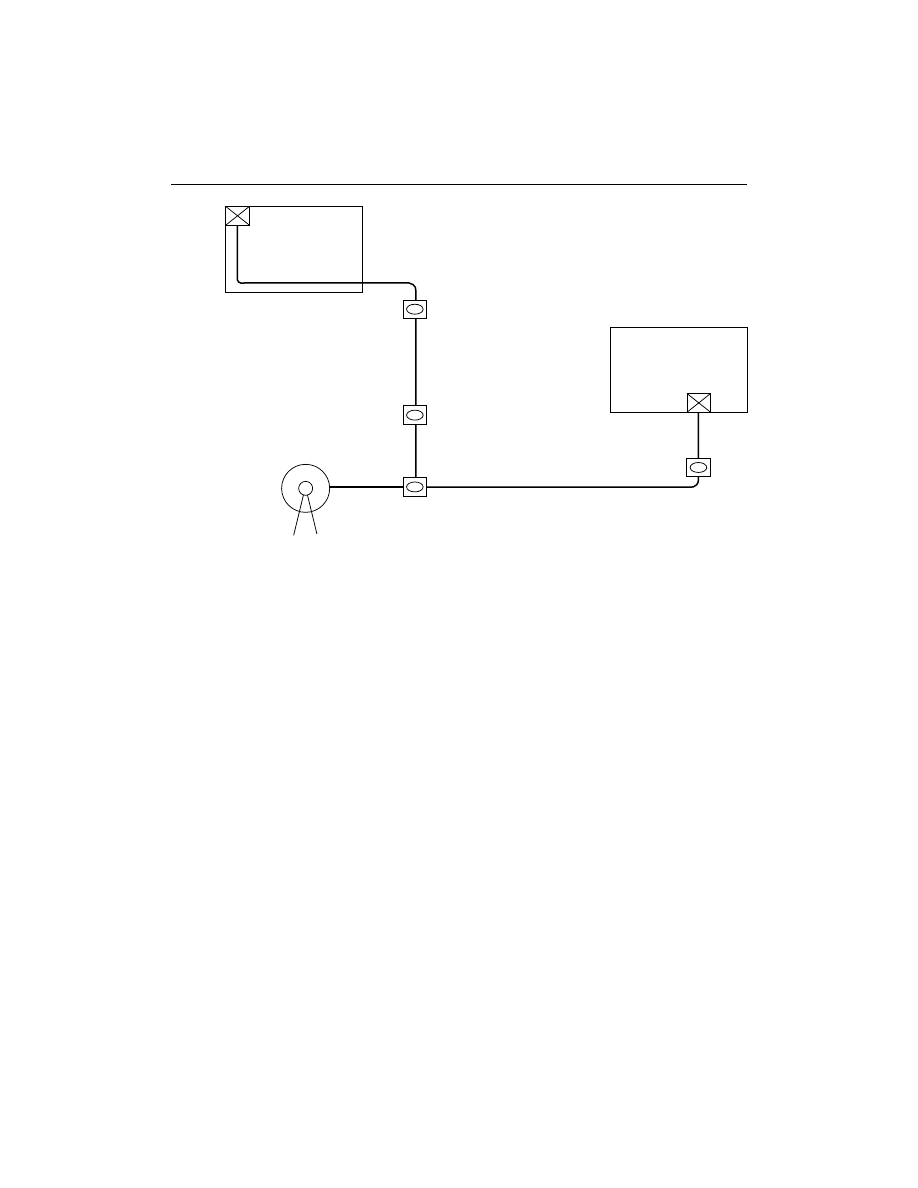

The walkout should start at one termination site (Figure 12-1). This location

will be designated with a clearly stated name, such as “#12 Communication

Room.” A rough fold-flat sketch will identify the fiber terminal location and

locations of other major system components, as well as other relevant features in

the room. The floor and walls will be marked with a pencil to indicate approxi-

mate locations of terminations. Notes should be made on the sketch concerning

conduit type and size, as well as whether pull string or measurement/pull tape has

been used. Verification of whether multiple ducts are involved is requested from

the superintendent.

CHAPTER 12 — PLANNING THE INSTALLATION

133

Figure 12-1

Preplanning walkout sketch.

Identification should be made defining which conduits go where either by

visual inspection or by tugging on the pull tape. The path of the conduit should

then be walked, making note on the diagram of any pull boxes, manholes, or

other abnormalities. This process must be carried out for each run on the job.

The more information the engineer provides on the print, the faster the

installation will progress. Remember, the object of this planning walkout is to

prevent the entire pulling crew from being idle while the lead technician tries to

track down the engineer or superintendent for clarifications or additional infor-

mation.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. The most accurate method of measuring for conduit pulls is ___________

a. from a set of prints.

b. field measurements taken with a wheel.

c. measuring with a pull tape.

134

CHAPTER 12 — PLANNING THE INSTALLATION

1

2

3

4

5

1 Room Location for Terminations

2 Bends

3 Conduit Size

4 Manholes

5 Pull Locations

2. How much extra cable must be added to make a fusion splice in a man-

hole?

a. 30 feet

b. 1 percent

c. 30 feet for each side of the splice

d. 10 feet

3. Subdividing larger conduits with innerducts _____________

a. efficiently uses duct space.

b. allows for future expansion.

c. offers additional protection to the fiber optic cable.

d. all of the above

4. The purpose of a planning walkout is to _____________

a. get a rough idea of the installation.

b. measure the conduit run.

c. clarify all the final details.

d. none of the above

CHAPTER 12 — PLANNING THE INSTALLATION

135

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

12 kontrola podzespołów instalacji powietrznej hamulców

2 BEFORE BEGINNING THE INSTALLATION

12 Put the verb into the correct form

Guide to the installation of PV systems 2nd Edition

12 kontrola podzespołów instalacji powietrznej hamulców

Kenyon, Sherrilyn Dark Hunter 12 Seize the Night

12 Rozwiązania materiałowe i instalacyjne systemów odprowadzania ścieków z budynków wraz z przykanal

11 12 vocab THE IMPOSIBLY CURVY BODY

12 on the Augustan Age and the Age of Sensibility

12 kontrola podzespołów instalacji powietrznej hamulców

Instructions for the installer S

39 zalacznik nr 12 specyfikacja tech instal co

Planning the Off Season 5 Key Messages

Charlie Richards Kontra s Menagerie 12 Ruffling the Peacock s Feathers

12 Can u the pride in the panther[Czy widzisz dumę w panter

Chapter 8 10 Planning the Active Directo

więcej podobnych podstron