05.06.2012

Endoscopic investigation of the internal organs of a 15th-century child mummy from Yangju, Korea

1/3

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2100347/?tool=pmcentrez

Go to:

Go to:

Go to:

Go to:

J Anat. 2006 November; 209(5): 681–688.

doi:

10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00637.x

PMCID: PMC2100347

Endoscopic investigation of the internal organs of a 15th-century child mummy from Yangju, Korea

Seok Bae Kim

,

Jeong Eun Shin

,

Sung Sil Park

,

Gi Dae Bok

,

Young Pyo Chang

,

Jaehyup Kim

,

Yoon Hee Chung

,

Yang Su Yi

,

Myung Ho Shin

,

Byung Soo

Chang

,

Dong Hoon Shin

, and

Myeung Ju Kim

Author information ►

Article notes ►

Copyright and License information ►

This article has been

cited by

other articles in PMC.

Abstract

Our previous reports on medieval mummies in Korea have provided information on their preservation status. Because invasive techniques cannot

easily be applied when investigating such mummies, the need for non-invasive techniques incurring minimal damage has increased among

researchers. Therefore, we wished to confirm whether endoscopy, which has been used in non-invasive and minimally invasive studies of

mummies around the world, is an effective tool for study of Korean mummies as well. In conducting an endoscopic investigation on a 15th-

century child mummy, we found that well-preserved internal organs remained within the thoracic, abdominal and cranial cavities. The internal

organs – including the brain, spinal cord, lung, muscles, liver, heart, intestine, diaphragm and mesentery – were easily investigated by endoscopy.

Even the stool of the mummy, which accidentally leaked into the abdominal cavity during an endoscopic biopsy, was clearly observed. In addition,

unusual nodules were found on the surface of the intestines and liver. Our current study therefore showed that endoscopic observation could

provide an invaluable tool for the palaeo-pathological study of Korean mummies. This technique will continue to be used in the study of medieval

mummy cases in the future.

Keywords: endoscopy, internal organs, Korea, mummy, nodules

Introduction

We have already published several papers detailing our studies of medieval mummies from the Chosun Dynasty of Korea (1392–1910) (

Shin et al.

2003a

,

b

;

Chang et al. 2006

;

Kim et al. 2006

). As described in these previous reports, such mummies can provide invaluable data on the physical

traits of medieval Korean people. However, it should be also noted that there are many difficulties in conducting studies on mummies, in that

descendants are reluctant to permit their ancenstor/mummy to be the subject of invasive scientific investigation. Therefore, most medieval

mummies that have undergone preliminary investigations in Korea have been reburied in other locations without sufficient further investigation.

We have therefore been interested in recent reports on the development of minimally invasive tools for investigating mummies. In other countries,

researchers have attempted to develop alternative tools for examining mummies without causing unnecessary damage given the desire for the

preservation of mummies. Fibreoptic endoscopy (

Manialawi et al. 1978

;

Gaafar et al. 1999

;

Spigelman & Donoghue, 2003

;

Hagedorn et al. 2004

)

or high-quality multidetector computerized tomography (MDCT) (

Melcher et al. 1997

;

Hoffman & Hudgins, 2002

;

Hoffman et al. 2002

;

Jansen et

al. 2002

;

Cesarani et al. 2003

,

2004

;

Hughes et al. 2005

;

Winder et al. 2005

) may be effective techniques for investigating mummies without

causing significant damage, or indeed any damage at all.

The advantages of these two techniques for non-invasive or minimally invasive examination cannot be matched by other methods. In the case of

MDCT, recent progress in CT image quality and rendering techniques has enabled scientists to conduct investigations on mummies from the

operator's viewpoint without dissection. Fibreoptic endoscopy can also be a useful tool for providing additional palaeo-pathological data on

mummies, as small pathological changes in intestinal organs, not easily identified by MDCT, can be observed using this technique.

In this study we set out to determine whether fibreoptic endoscopy could also be used as an effective tool for obtaining data on the internal organs

of medieval Korean mummies. If proven to be useful in providing satisfactory data on the preservation status of, or palaeo-pathological clues to,

the internal organs of Korean mummies, this technique should be used in all future studies of Korean mummies.

Materials and methods

Our study was performed in accordance with the Vermillion Accord on Human Remains, World Archaeological Congress, South Dakota, 1989.

With regard to the child mummy investigated in this study (

Fig. 1A

), our previous studies (

Shin et al. 2003a

,

b

;

Kim et al. 2006

) offered basic data.

Fig. 1

(A) Fifteenth-century child mummy. (B) Endoscopic examination. (C) A hole (red arrow) was made in

the substernal region for inserting the fibreoptic endoscope into the body cavity.

In order to view the internal organs of the mummy while incurring minimal damage to the surface of his skin, we performed fibreoptic endoscopy

at Dankook University Hospital (

Fig. 1B

). The fibreoptic endoscope (GIF XQ230, Olympus Co., Japan) was inserted through an incision made in

the epigastric area of the mummy to examine the remains of the organs within the abdominal cavity (

Fig. 1C

). To investigate the thoracic cavity,

an incision was made in the skin, on the right chest. The organs within the cranial cavity and vertebral canal were observed through holes made in

the occipital region of the skull and on the lower back, respectively.

During endoscopic investigation, photographs and videos were taken to record our findings. The videos, recorded from analog signals, were

reformatted to a digital multimedia file.

Results

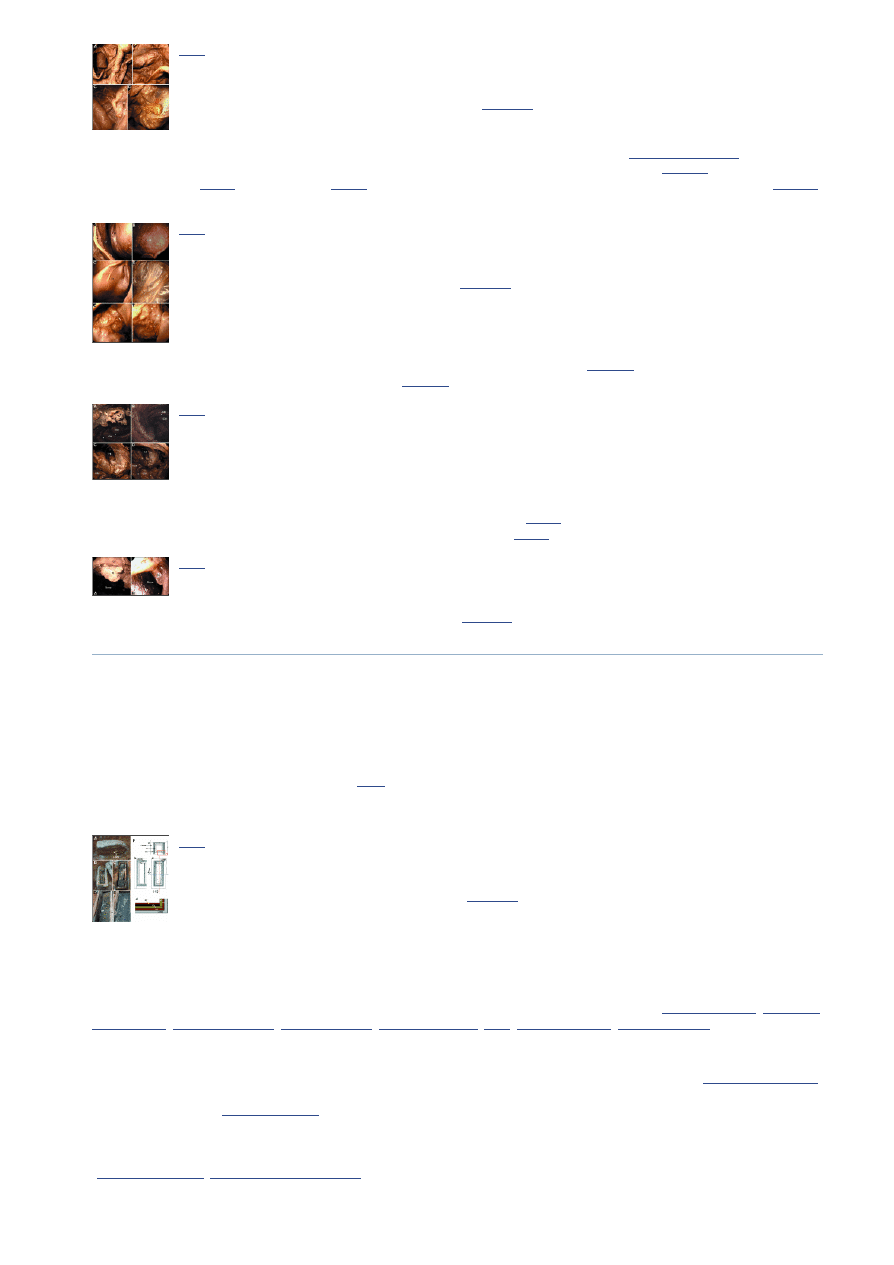

In the course of our endoscopic investigation, we observed dark-brown internal organs within the abdominal, thoracic, cranial and spinal cavities.

Because all of the investigated organs were dehydrated or shrunken, we could not easily differentiate one from the other. When we inserted the

endoscope into the abdominal cavity, the intestines could be identified (

Fig. 2A–C

). During a biopsy of the intestines, possible stool material

escaped from the intestinal lumen (

Fig. 2D

).

1

1

2

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

4

9

05.06.2012

Endoscopic investigation of the internal organs of a 15th-century child mummy from Yangju, Korea

2/3

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2100347/?tool=pmcentrez

Go to:

Fig. 2

Intestine observed by fibreoptic endoscopy. (A–C) When the endoscope was inserted into the

abdominal cavity, the intestine could be identified. Because the intestine was severely dehydrated or

shrunken, subsections of intestine could not be differentiated.

(more ...)

When the endoscope was turned upwards, the liver and diaphragm were observed. The multimedia file (see

supplementary Fig. S1

) shows our

endoscopic findings on the intestine, liver and diaphragm. Unusual nodules were noted on the surface of the liver (

Fig. 3A,B

), but not on the

adjacent diaphragm (

Fig. 3C

) and mesenteries (

Fig. 3D

). Similar nodules were also observed on the serosal surface of the intestinal wall (

Fig. 3E,F

).

Fig. 3

(A,B) Liver (Lv) and diaphragm (Di) observed by fibreoptic endoscopy. Unusual nodules were spread

on the surface of the liver. The diaphragm (C) and mesenteries (D) did not exhibit such surface

nodules. (E,F) Similar nodules were also observed on the

(more ...)

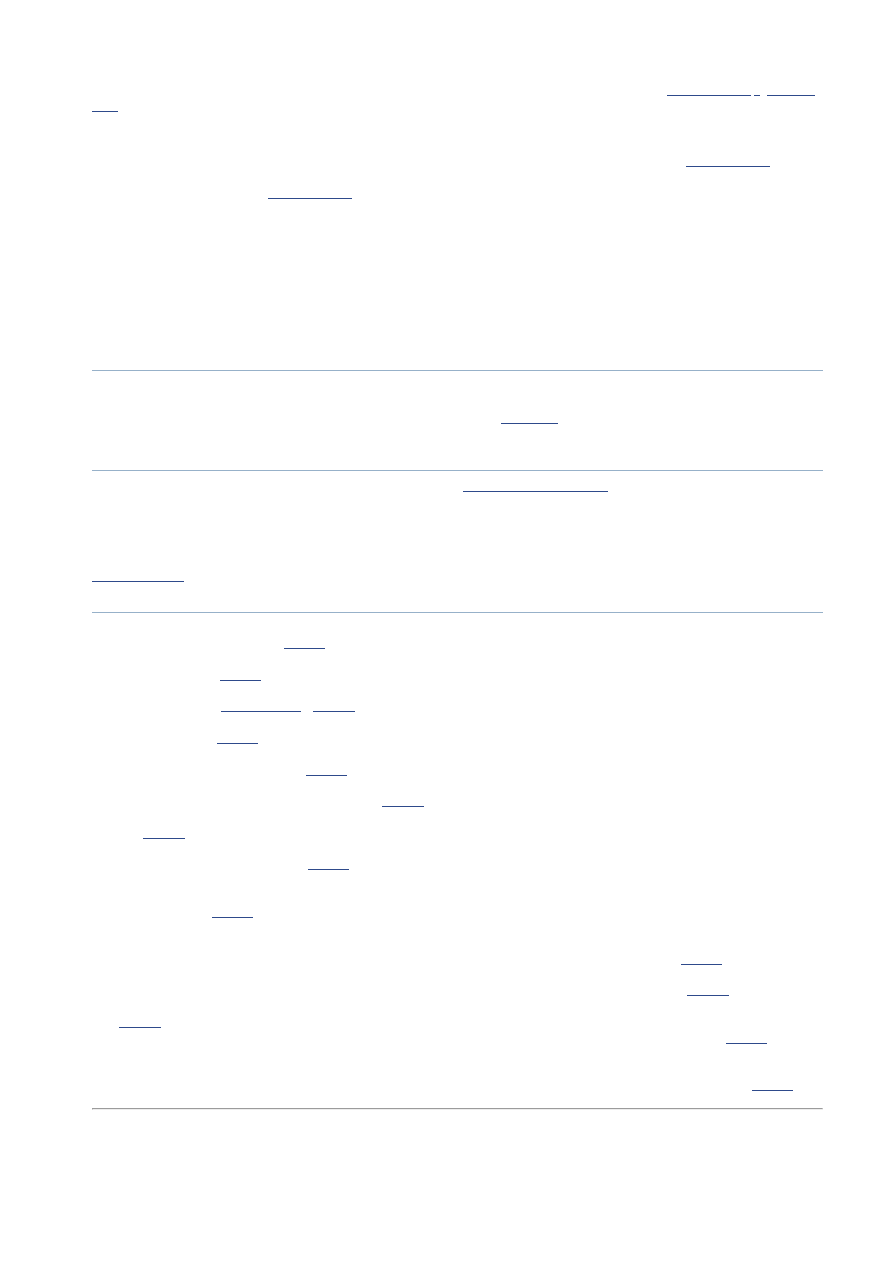

In the thoracic cavity, the remains of the lungs, ribs and intercostal muscles were clearly observed (

Fig. 4A,B

). Even a heart remnant was found

within the thoracic cavity, although it was notably shrunken (

Fig. 4C,D

).

Fig. 4

Thoracic cavity observed by fibreoptic endoscopy. (A,B) Remants of the lung (Lu), ribs (asterisks) and

intercostal muscles (ICM). (C,D) The heart remnant (Ht) was also found within the thoracic cavity,

though the organ was markedly shrunken.

Finally, we investigated the brain and spinal cord within the skull and vertebral canal, respectively. In the cranial cavity, the contracted brain

remnant was observed with heavy calcification-like substances spread over its surface (

Fig. 5A

). On inserting the endoscope into the hole made via

a laminectomy of vertebra, the spinal cord was identified within the vertebral canal (

Fig. 5B

).

Fig. 5

Brain and spinal cord observed by fibreoptic endoscopy. (A) Within the skull, a shrunken brain

remnant (Br) was observed with heavy calcification-like substances (asterisk) spread over its surface.

(B) When the endoscope was inserted into the hole made

(more ...)

Discussion

Medieval Koreans did not believe in resurrection or immortality of the soul. Instead, they thought that misfortune might accompany the

incomplete disintegration of the corpses of their ancestors. Therefore, they chose graveyards in which their ancestors’ corpses and the

accompanying burial materials would decay completely. In addition, medieval documents such as The National Code for the Five Rituals

(Gukjooryeiui in Korean) or The Family Rituals of Chu-si (Jujagarye in Korean), by which the construction of tombs during the Chosun Dynasty

was strictly regulated, do not contain any mention of intentional or non-intentional treatments for artificial mummification, and therefore

mummification in Korea seems not to have involved artificial mummification processes. Given that the climate of Korea is not appropriate for

natural mummification, the Korean mummification process has thus remained unresolved. Considering that Korean mummies have only been

found in tombs where the lime–soil mixture barrier (

Fig. 6

) was not broken until they were found, we speculate that the separation of the inner

space of the coffins from the outer space by the lime–soil mixture barrier may play a crucial role in mummification in these cases. However, the

exact cause of mummification in Korea will be elucidated in forthcoming studies.

Fig. 6

Structure of a medieval tomb with lime–soil mixture, from the Chosun Dynasty, found in Hadong,

Korea, in April 2006. The burial conditions associated with this case are representative of other

medieval tombs, including those in which mummies have

(more ...)

Whatever the principal cause of mummification in Korea, the development of tools for investigating mummies with minimal damage is crucial for

researchers in Korea because descendants will not readily consent to invasive scientific investigations. The development of non-invasive or

minimally invasive techniques for investigation of mummies has been actively pursued by researchers around the world. Two of the most

successful techniques have been fibreoptic endoscopy and high-quality MDCT scanning. In the case of MDCT scans, virtual reconstructions of

hard-to-access internal organs or heavily wrapped faces of Egyptian mummies have been conducted successfully (

Melcher et al. 1997

;

Hoffman &

Hudgins, 2002

;

Hoffman et al. 2002

;

Jansen et al. 2002

;

Cesarani et al. 2003

,

2004

;

Hughes et al. 2005

;

Winder et al. 2005

).

Although MDCT scans can provide invaluable data on the internal organs of mummies without any damage to the surface of the mummy,

fibreoptic endoscopy has an advantage that is not easily attainable by MDCT: direct visualization of internal organs and their small pathological

changes, which is crucial for deducing the pathophysiolocial states of the mummies. For example, the endoscopic study by

Hagedorn et al. (2004)

successfully showed dentogenic sinusitis and chronic middle-ear infections with intracranial perforation in mummies from Upper Egypt. Other

nasal endoscopic trials by

Gaafar et al. (1999)

also showed evidence of brain removal during artifical mummification in ancient Egypt. Because

they found an enlarged conduit between the cranial and nasal cavities in all of the mummies investigated, they concluded that brain removal in

Egypt was likely to have been performed by well-trained personnel with specially designed instruments for endonasal craniotomy. Therefore, it

was shown that endoscopic examinations could provide meaningful data on mummies that are not as easily acquired using other techniques

(

Manialawi et al. 1978

;

Spigelman & Donoghue, 2003

).

Most descendants of Koreans whose bodies have been mummified are opposed to invasive examinations of their mummified ancestors, but using

fibreoptic endoscopy to examine the internal organs of Korean mummies may turn out to be more acceptable, if endoscopy can be proved to be a

05.06.2012

Endoscopic investigation of the internal organs of a 15th-century child mummy from Yangju, Korea

3/3

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2100347/?tool=pmcentrez

Go to:

Go to:

Go to:

useful non-invasive or minimally invasive technique. In this regard, our current endoscopic study on the internal organs of a previously examined

child mummy could be the basis for future investigations into medieval Korean mummies.

We have already published a brief profile of the 15th-century child mummy that is the subject of the present study (

Shin et al. 2003a

,

b

;

Kim et al.

2006

). To summarize, the child mummy was found in a wooden coffin with the outermost lime–soil mixture barrier intact; the child had been

alive at some time during the period from 1411 to 1442

AD

; the child had died at about 4.5–6.6 years of age, possibly due to asphyxia by massive

respiratory bleeding; and the histological conservation pattern was similar to those in cases reported from other countries.

Among the previously acquired data on the child mummy, the finding that is most relevant here is a radiographic one (

Shin et al. 2003a

). That is,

plain X-ray and CT scans showed that the brain, spinal cord, liver, back muscles, and the residues of the spleen, heart and lung seemed to be well

preserved within the body cavities (

Shin et al. 2003a

). However, because direct visualization of the preserved organs was not attempted in our

previous studies, we subsequently performed an endoscopic study to reveal the state of preservation of the internal organs. In our current

endoscopic study, we showed that the liver, heart, brain, spinal cord, diaphragm and mesentery were well preserved, despite considerable

shrinkage of the organs. In the course of our investigation, clues to the palaeo-pathological changes in some of the mummified organs could be

observed, and we confirmed the presence of unusual nodules on the surface of the liver and intestine. Given that there were no such nodules on

any of the other organs, these nodules on the liver or intestinal surface might have been caused by unknown pathological changes resulting from,

for example, secondary tumour metastasis, tuberculosis or hydatid disease. However, we are cautious in suggesting the possibility of pathological

changes as the exact cause of the changes could not be clearly elucidated, and because the nodules might have been formed as a result of the

mummification process. As fibreoptic endoscopy evidently is a useful tool for collecting palaeo-pathological clues in Korean mummies, endoscopic

investigation will be performed in all future studies, if descendants allow minimal incisions to the skin to be made.

Acknowledgments

All of the investigations into and examinations of the mummy found in Y angju were superintended principally by the Seok Ju Seon Memorial

Museum and the Institute for Oriental Studies, Dankook University. We thank, in particular, Ki Rok Choi, a producer for the Korean Broadcast

System (KBS), for his devotion to the preservation of medieval Korean mummies.

Figure 1(A)

is included with the generous consent of the staff of

KBS, who took the photograph. This study was supported by Korea Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2003-I01485-E00006).

Supplementary material

The following supplementary material is available for this article online at

www.blackwell-synergy.com

:

Video Clip S1

Endoscopic observations of the 15th-century child mummy. Details of the intestine, liver and diaphragm can be seen. Suction and tissue sampling

are also recorded in this file.

Click here to view.

References

Cesarani F, Martina MC, Ferraris A, et al. Whole-body three-dimensional multidetector CT of 13 Egyptian human mummies. Am J

Roentgenol. 2003;180:597–606. [

PubMed

]

Cesarani F, Martina MC, Grilletto R, et al. Facial reconstruction of a wrapped Egyptian mummy using MDCT. Am J Roentgenol.

2004;183:755–758. [

PubMed

]

Chang BS, Uhm CS, Park CH, et al. Preserved skin structure of a newly found Fifteenth century mummy in Daejeon, Korea. J Anat.

2006;209:671–680. [

PMC free article

] [

PubMed

]

Gaafar H, Abdel-Monem MH, Elsheikh S. Nasal endoscopy and CT study of Pharaonic and Roman mummies. Acta Otolaryngol.

1999;119:257–260. [

PubMed

]

Hagedorn HG, Zink A, Szeimies U, Nerlich AG. Macroscopic and endoscopic examinations of the head and neck region in ancient Egyptian

mummies. HNO. 2004;52:413–422. [

PubMed

]

Hoffman H, Hudgins PA. Head and skull base features of nine Egyptian mummies: evaluation with high-resolution CT and reformation

techniques. Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:1367–1376. [

PubMed

]

Hoffman H, Torres WE, Ernst RD. Paleoradiology: advanced CT in the evaluation of nine Egyptian mummies. Radiographics. 2002;22:377–

385. [

PubMed

]

Hughes S, Wright R, Barry M. Virtual reconstruction and morphological analysis of the cranium of an ancient Egyptian mummy. Australas

Phys Eng Sci Med. 2005;28:122–127. [

PubMed

]

Jansen RJ, Poulus M, Taconis W, Stoker J. High-resolution spiral computed tomography with multiplanar reformatting, 3D surface- and

volume rendering: a non-destructive method to visualize ancient Egyptian mummification techniques. Comput Med Imaging Graph.

2002;26:211–216. [

PubMed

]

Kim MJ, Park SS, Bok GD, et al. A case of Korean medieval mummy found in Y angju: an invaluable time capsule from the past. Archaeol

Ethnol Anthropol Eurasia. 2006 in press.

Manialawi M, Meligy R, Bucaille M. Endoscopic examination of Egyptian mummies. Endoscopy. 1978;10:191–194. [

PubMed

]

Melcher AH, Holowka S, Pharoah M, Lewin PK. Non-invasive computed tomography and three-dimensional reconstruction of the dentition of

a 2800-year-old Egyptian mummy exhibiting extensive dental disease. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1997;103:329–340. [

PubMed

]

Shin DH, Choi Y H, Shin KJ, et al. Radiological analysis on a mummy from a medieval tomb in Korea. Ann Anat. 2003a;185:377–382.

[

PubMed

]

Shin DH, Y oun M, Chang BS. Histological analysis on the medieval mummy in Korea. Forensic Sci Int. 2003b;137:172–182. [

PubMed

]

Spigelman M, Donoghue HD. Paleobacteriology with special reference to pathogenic mycobacteria. In: Greenblatt C, Spigelman M, editors.

Emerging Pathogens: Archaeology, Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 175–188.

Winder RJ, Glover W, Golz T, et al. ‘Virtual unwrapping’ of a mummified hand. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2005;119:577–582. [

PubMed

]

Articles from Journal of Anatomy are provided here courtesy of Anatomical Society of Great Britain and Ireland

(42M, wmv )

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Zabreiko P P , Krawcewicz W New Applications of mathematics Investigation of the Co

Investigating the Afterlife Concepts of the Norse Heathen A Reconstuctionist's Approach by Bil Linz

Integration of the blaupunkt RC Nieznany

Biogenesis of the gram negative Nieznany

Multistage evolution of the gra Nieznany

asm state of the art 2004 id 70 Nieznany (2)

An analysis of the European low Nieznany

A History of the Evolution of E Nieznany (2)

DYNAMIC BEHAVIOUR OF THE SOUTH Nieznany

The Three Investigators 03 The Mystery of the Whispering Mummy us

Results of the archaeozoological investivgations

The Three Investigators 31 The Mystery Of The Scar Faced Beggar

The Three Investigators 10 The Mystery of the Moaning Cave us

The Three Investigators 27 The Mystery Of The Magic Circle us

The Three Investigators 26 The Mystery of the Headless Horse us

The Three Investigators 21 The Secret Of The Haunted Mirror us

Ritter Investment Banking and Securities Insurance (Handbook of the Economics of Finance)(1)

Being Warren Buffett [A Classroom Simulation of Risk And Wealth When Investing In The Stock Market]

więcej podobnych podstron