The next two articles in this series are on the

visual pathways – this first article relates to

examination of the optic disc and diseases

affecting the optic nerve. The next article will

discuss diseases affecting the optic chiasm, optic

tracts and radiations and the visual cortex.

The anterior visual pathway

Difficulties in diagnosis of diseases of the

anterior visual pathway lie in two areas: firstly,

while it may be relatively easy to recognise an

optic disc appearance as abnormal, it may be

difficult to decide whether that appearance

reflects disease or is simply a variation of

normality.

Secondly, diseases of the anterior visual

pathways may be missed because of failure to

consider whether there is evidence of abnormal

optic nerve function. In the early stages of optic

neuropathy, the optic disc may appear to be

normal and the visual acuity near normal, lulling

the practitioner into a false sense of security.

This article attempts to help practitioners

decide in practical terms whether a disc

appearance is normal or abnormal, and how

to decide if there is any evidence of optic nerve

disease.

It will also discuss some of the more

common disorders encountered in

neuro-ophthalmology with emphasis on

recognition of significant signs of each which

point towards diagnosis.

When looking at a suspicious disc, or

considering the possibility of anterior visual

pathway disease, it pays to ask yourself four

questions, which are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1

Questions to ask when faced with a

suspicious disc

1) Is this disc normal or abnormal?

2) Does the history give me a

clue?

3) Is there any evidence of optic

nerve dysfunction?

4) Do I need to be worried?

Disorders of the visual pathway:

from the optic disc to the visual cortex

Diagnosis of neuro-ophthalmological disorders has been transformed over the last 20 years with the advent of

CT (computed tomography) and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scanning to examine the brain and optic

nerves. However, before these examinations are performed, someone has to detect an abnormality of

appearance of the optic disc or reduced function of the afferent visual system to warrant expensive and

in the case of CT scan x-ray radiation potentially harmful investigations. Patients will often first present to their

optometrist with vague complaints, and their practitioner must make the decision whether or not to refer.

July 28, 2000 OT

Chris Hammond MRCP, FRCOphth, Consultant in Ophthalmology, Farnborough Hospital, Bromley

www.optometry.co.uk

Disc: normal or abnormal?

The first thing to say when looking at a disc and

trying to decide, for example, whether it is

swollen or not, is that is not always easy to tell,

even experienced neuro-ophthalmologists have

difficulty sometimes. They may be able to resort

to other investigations such as fluorescein

angiography, so if you are unable to decide,

referral is obviously the next step.

Most significant abnormalities have some

evidence of optic nerve damage, however slight,

or visual field changes, if examined carefully.

Many abnormal-looking discs with normal function

are congenital abnormalities, so any evidence of

an acquired change in the disc compared to

previous records must be treated with suspicion.

Experience of close examination of normal

discs make abnormal discs easier to recognise.

Optic discs have a rather limited repertoire;

therefore when examining a disc, you should ask

yourself whether there is swelling (papillitis,

papilloedema), pallor (optic atrophy) or new

vessels (diabetes). While indirect binocular

biomicroscopy using the slit-lamp will allow

three-dimensional examination of the disc, the

direct ophthalmoscope is still useful as it provides

better magnification to look for subtle signs such

as spontaneous venous pulsation.

Is the history helpful?

Consideration of previous medical and ophthalmic

history is obviously useful, as it may give a clue

as to the causes of visual pathway disease. Changes

may be secondary, such as optic atrophy after a

longstanding retinal detachment or secondary to

retinitis pigmentosa, or dragging of vessels after

significant retinopathy of prematurity. However,

although previous history will often be important,

do not allow it to explain all new symptoms.

We recently treated a patient with a history

of residual esotropia and amblyopia from

childhood who presented with a worsening

esotropia. Although she was initially reassured by

her optometrist, it was only when she developed

ipsilateral deafness and facial nerve palsy that her

acoustic neuroma was diagnosed – the worsening

esotropia was in fact a new sixth nerve palsy.

A careful history is vital when concerned

about anterior visual pathway disease. Many

patients present to their optometrists with

headaches (“Is it due to my eyes?”) and the

The College of Optometrists has

awarded this article 2 CET credits.

There are 12 MCQs with a

pass mark of 60%.

The College of

Optometrists

ABDO has awarded

this article

2 CET credits (LV).

✓

sponsored by

practitioner must decide, especially if he or she is

unsure about the presence of swollen discs,

whether the symptoms indicate benign headaches

(e.g. tension-type) or those of raised intracranial

pressure. The latter headaches are worse in the

morning on waking or at night because of the

increase in CSF pressure when lying flat (they

may also be worse when bending over or

straining), and are often associated with nausea

and/or vomiting.

Tension-type headaches are intermittent,

come on often later in the day and are absent on

waking, and are often described as a frontal or

retro-orbital band of tightness (see CPD module 2

part 5 OT 5/05/00 for a full review of the

differential diagnosis of headaches).

Other questions to raise when considering

anterior visual pathway disease include questions

about hypopituitarism associated with chiasmal

compression (loss of secondary sexual

characteristics and impotence in men and

amenorrhoea (absent periods) in women) or

previous transient neurological symptoms such as

paraesthesiae or weakness in multiple sclerosis.

Is there an optic neuropathy?

An important component of the examination is to

look for any evidence of abnormal optic nerve

function – in early stages of disease, the visual

acuity may be only slightly decreased. Therefore,

it is important to look for reduced colour vision,

either using colour test plates or in unilateral

disease it is easy to test for subjective loss of

colour vision (“Look at this red pen top with

each eye – is there any difference between the

two eyes?”). There will be a relative afferent

pupil defect in unilateral or asymmetric bilateral

optic neuropathy, and practitioners must be able

to detect this important sign.

Visual field loss is universal with anterior

visual pathway disease, and again an ability to

perform confrontational visual fields is extremely

useful, as well as use of automated perimetry.

Field defects described include the central

scotoma of an optic neuropathy as well as the

centrocaecal scotoma (extending to include the

blind spot) seen in a toxic or heredofamilial optic

neuropathy (these may be impossible to separate

clinically). The enlarged blind spot of a swollen

optic disc (and this is often the only field

abnormality with papilloedema) may not be

28

www.optometry.co.uk

29

even down to no perception of light. This is

followed by a gradual resolution, which lasts

weeks to months. Signs to look for include loss

of colour vision, a relative afferent pupillary

defect and a central scotoma on visual field

testing.

The disc usually appears to be normal,

although there may be a papillitis, particularly

in children in whom the condition is often

bilateral and associated with viral infection.

This has a better prognosis. Rarely, Leber’s

neuroretinitis is seen after an attack of optic

neuritis: exudates involving the macula can be

seen.

The cause of optic neuritis is demyelination

and optic neuritis is the presenting feature of

multiple sclerosis (MS) in up to 25-50% of

patients with this disease. The risk of MS long-

term is up to 70% in those who have had an

attack of optic neuritis. Around 75-80% of MS

patients may develop optic neuritis (or evidence

of a previous attack) during the course of the

disease. Therefore, optic neuritis is strongly

associated with MS and even one attack may be

a forme fruste of MS. However, there are other

causes: post-viral (particularly in children),

granulomatous infiltration (such as sarcoidosis)

or associated with adjacent sinus infection.

Investigations are not always needed in

classic optic neuritis. Identification of patients

who are more likely to develop MS is possible

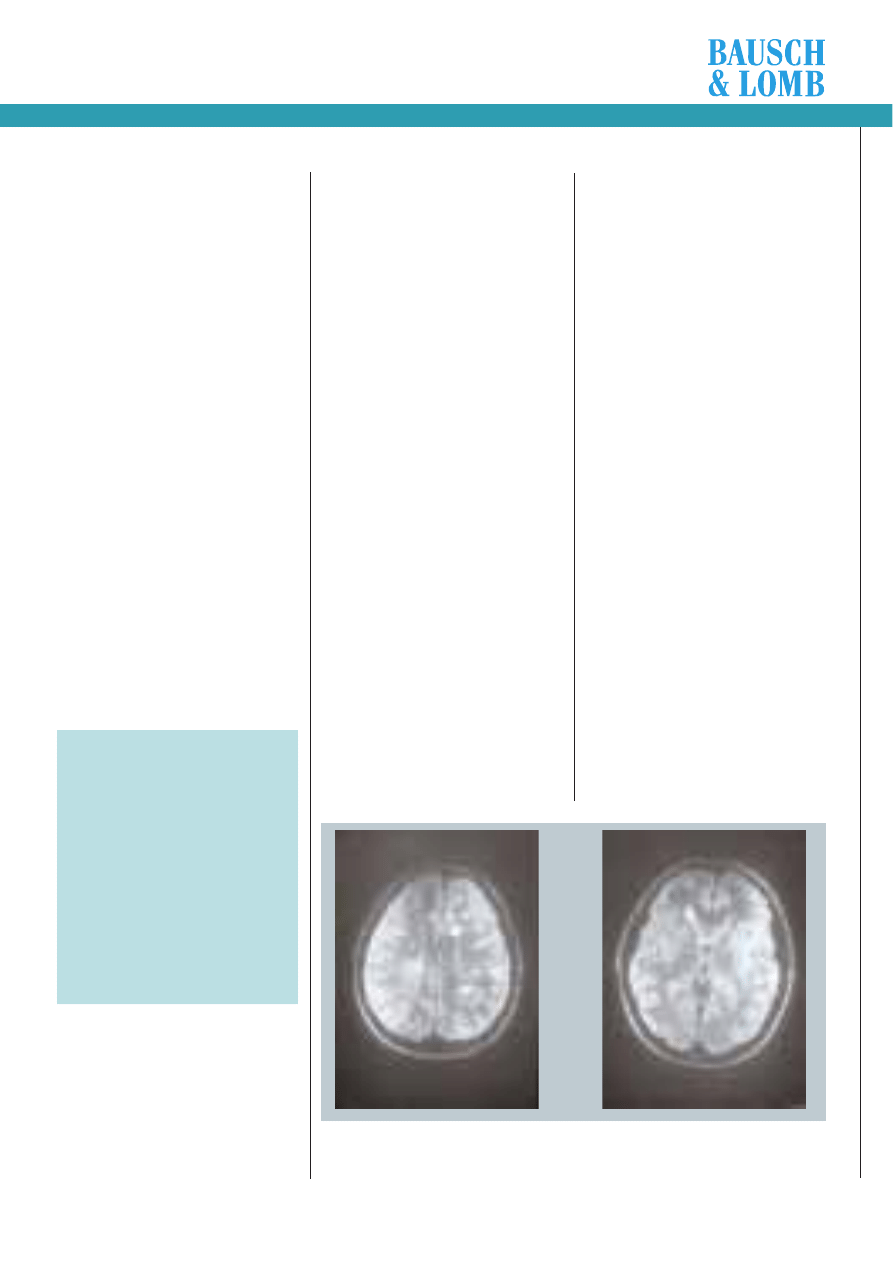

with MRI scanning. This may show white lesions

in the periventricular grey matter (Figure 1).

The dilemma is then what to tell the

patient. We cannot predict when the next

attack of demyelination will occur (if ever),

have no preventive treatment, and patients

imagine, with the diagnosis of possible MS, the

worst scenario, while in fact there is a spectrum

of disease from very mild to fatal. Therefore,

the current practice is not to discuss the

possibility of MS in a patient with optic neuritis

unless they ask or if they have had previous

neurological episodes making MS very likely.

Electrodiagnostic tests show delayed Visual

Evoked Potentials which can be useful if the

diagnosis is in doubt.

A large multicentre optic neuritis treatment

trial reported no difference in visual outcome in

those treated with oral or intravenous steroids

or placebo, although steroids speed up recovery

a little. They did initially report that

intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone)

reduced the risk of subsequent MS, although

further follow-up has shown that the long-term

risks were the same for all groups.

We await newer treatments, such as the

controversial beta interferon. This has been

shown to reduce the number of relapses in a

specific sub-group of patients with regularly

relapsing/remitting disease. Its cost (£10,000

per patient per year) has led to a

recommendation from the National Institute of

Clinical Excellence (NICE) that it should not be

routinely prescribed.

Visual outcome is on the whole good -

many patients have near normal acuity,

although there are almost always subtle colour

vision defects (and delayed visual evoked

potentials). The final acuity does not reflect

the severity of loss of visual function, and so

too, the degree of optic disc atrophy does not

reflect final vision. In particular, children may

have a very pale optic disc but an extremely

good visual acuity.

.

Anterior ischaemic

optic neuropathy (AION)

Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy is an

important diagnosis to consider, as it may herald

potentially blinding disease which needs urgent

treatment. There are two forms: the non-arteritic

form and the arteritic form. The latter is the

more serious, but the former is more common.

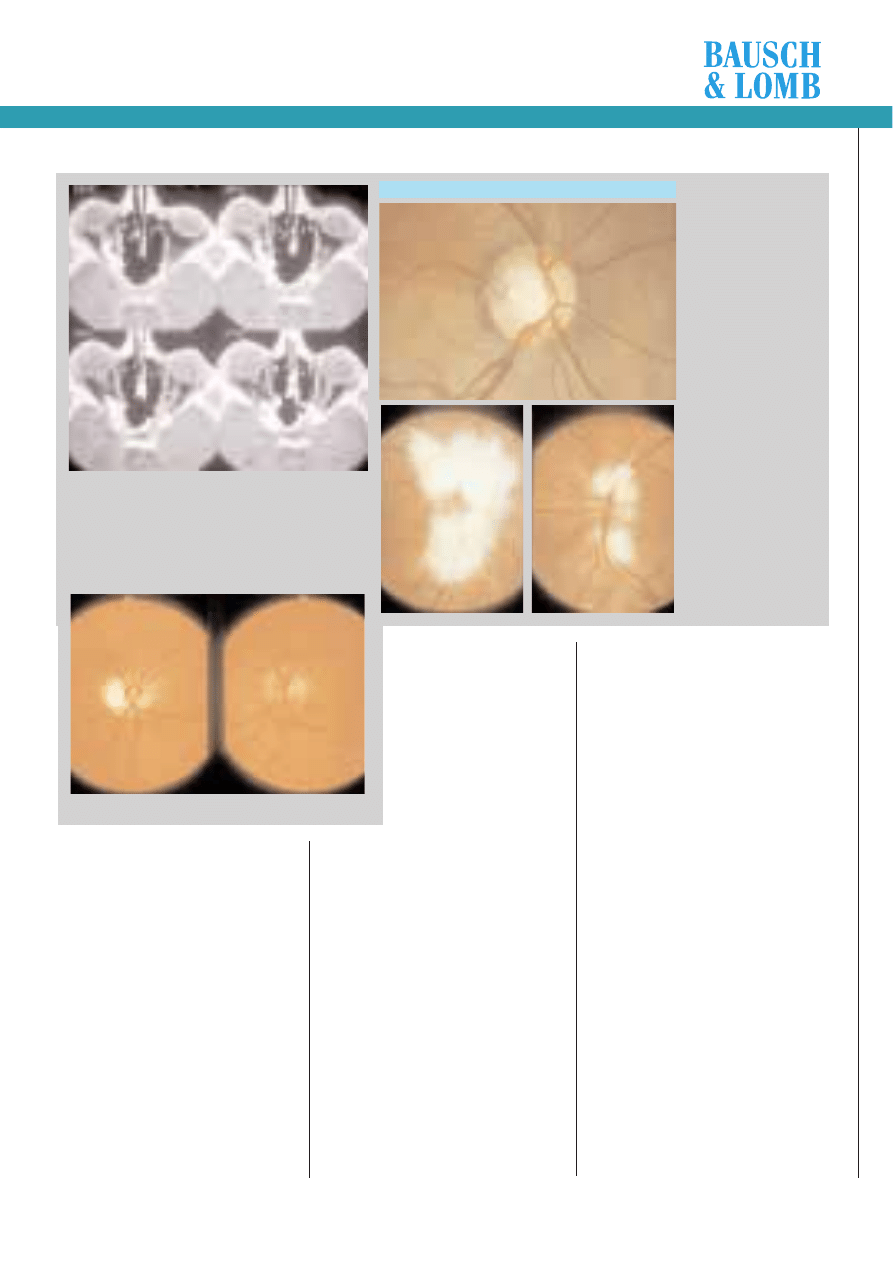

Figure 1 MRI scan

Two slices of the MRI scan of a 23-year-old patient with optic neuritis. The white lesions are typical of those

seen in the periventricular area in multiple sclerosis, and mean that this person is at high risk of developing

further neurological problems.

sponsored by

Module 2 Part 8

diagnosed by automated fields but comparison

with your own blind spot on confrontation fields

may detect it. Peripheral constriction and good

vision are observed in the optic atrophy seen

after papilloedema. An altitudinal field defect is

seen in retrolaminar vascular occlusion, such as

anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AION).

Do I need to be worried?

If the optic disc is swollen, then this may signify

raised intracranial pressure or a papillitis, both of

which may require investigation and treatment, so

urgent referral is indicated. It is important to

emphasise that visual function may be normal in

early papilloedema (apart from a slightly enlarged

blind spot which is not easy to diagnose), so this

should not put you off referral. By contrast, other

disc abnormalities with no optic neuropathy are

unlikely to be serious.

Optic atrophy does not occur overnight –

research involving transection (cutting) the optic

nerve acutely shows that optic atrophy is only

apparent four to six weeks later. Therefore a

patient presenting with pale optic discs is

unlikely to have a problem that has only just

occurred requiring immediate attention – the

problem has been brewing. However, a pale

swollen disc often does occur overnight. This

signifies an ischaemic optic neuropathy which has

been shown to be most likely to occur on waking,

possibly due to hypotension overnight

(papilloedema results in a pink swollen disc). In

this instance, the possible diagnosis of giant cell

arteritis must be considered, one of the few

neuro-ophthalmological emergencies.

First, I will discuss the acquired optic

neuropathies, which are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2 - Acquired optic neuropathies

Optic neuritis

■ Idiopathic/demyelination

■ post-viral

■ Granulomatous inflammation

■ Adjacent infection

Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy

■ Non-arteritic

■ Arteritic

Diabetic papillopathy

Toxic optic neuropathies

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy

Papilloedema

Tumours

■ Glioma

■ Meningioma

Optic neuritis

Optic neuritis is one of the commonest forms of

optic neuropathy in the population, and

typically affects young women between the ages

of 20 to 40. They may present with pain on eye

movements or retro-orbital headache, which

often resolves over a week or so, associated

with monocular progressive visual loss.

The visual loss tends to worsen over a week

to ten days, and may be slight or profound,

o

t

July 28, 2000 OT

www.optometry.co.uk

30

Arteritic AION affects people aged 60 and

older, and women more than men. The reason

why it is such an important diagnosis to

consider is that visual loss if the condition is

not treated becomes bilateral rapidly – possibly

in 65% of people within three weeks.

Therefore, the diagnosis of arteritic AION

must be considered in any elderly patient

presenting with visual loss and a swollen disc,

or systemic symptoms, and requires urgent

hospital referral. The diagnosis is suggested by a

raised ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate)

blood test, which demonstrates inflammation in

the arteries, and a temporal artery biopsy proves

the diagnosis (characteristic “giant cells” are

seen in the artery wall on microscopy).

This procedure is performed under local

anaesthetic. However, treatment is often

instituted before this, to try to control the

inflammation and prevent further visual loss.

Treatment consists of high dose oral steroids

(80mg prednisolone is often prescribed) which is

tailed off over a couple of years, according to

symptoms and blood tests. High doses of steroid

are not without complications in this group of

elderly patients, and include mood disturbances,

diabetes, hypertension and osteoporosis (bone

thinning).

Diabetic papillopathy

This is rare, and usually affects people with type

1 diabetes, often occurring in their second and

third decade. The patients present with a

swollen optic disc, which is bilateral in 75% of

cases, and often asymptomatic – there are no

symptoms of visual loss. The aetiology is

presumed to be vascular, and it does not seem

to be related to diabetic control. Diabetic

papillopathy usually resolves spontaneously with

good visual outcome, but obviously other causes

of swollen discs must be considered before

attributing it to diabetes.

Toxic optic neuropathy

This condition has been labelled with various

names such as toxic amblyopia and tobacco-

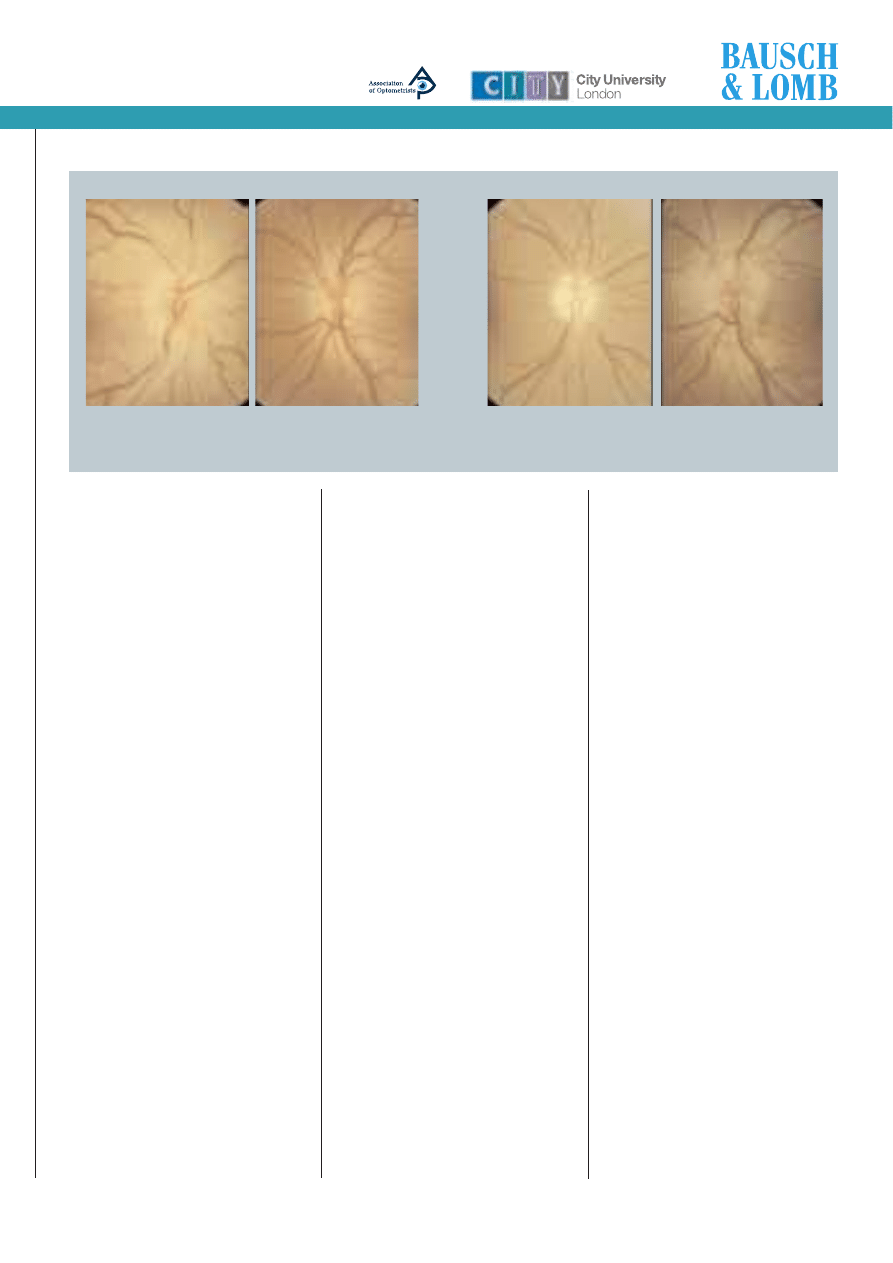

Non-arteritic AION

This typically affects men, aged from 50 to 70.

They present with a sudden, painless visual loss,

usually one-off, although a small proportion may

develop stepwise loss of vision. The actual extent

of the acuity and colour vision loss is variable.

Commonly, there is an altitudinal field defect, i.e.

the field loss is either the upper or the lower

field. Acutely, sectoral infarction of disc is seen:

the optic disc appears swollen and pale,

especially in the area that has infarcted (Figure

2 a,b).

Subsequently, the disc is atrophic. We now

recognise that people susceptible to AION have a

“disc at risk” – a small hypermetropic-looking

disc. This has led to a belief that these discs are

at risk because of an anatomical predisposition

to infarction of the short posterior ciliary

arteries.

A general medical referral is appropriate in

patients with non-arteritic AION because some

series report up to 40% of patients with

hypertension, and 20% diabetes. There is no

known treatment to limit the amount of visual

loss and to prevent future loss of vision in the

fellow eye, which seems to have up to a 40% risk

of visual loss, occurring months or even years

later. Some authors have suggested that aspirin

might have a role.

Arteritic AION

This disease associated with giant cell arteritis

results in the same optic disc appearance, that of

acute infarction, so the disc is swollen and pale.

There may be associated nerve fibre layer

haemorrhages or even choroidal infarcts.

However, the visual loss tends to be more severe.

In addition to the visual loss, there are usually

systemic features of headache (often severe and

associated with scalp tenderness), malaise,

fever, weight loss and jaw claudication. This

causes pain in the jaw during chewing or

talking such that the person has to stop

chewing until the pain subsides – the jaw

muscles are ischaemic, as the artery is critically

narrowed.

alcohol amblyopia. The latter name gives a clue

as to the patients who present with this

problem: they are often heavy drinkers and

smokers with poor nutrition. Always consider

this diagnosis in people who neglect themselves

who present with unexplained visual loss.

Various agents may cause a toxic optic

neuropathy, including thiamine deficiency

(vitamin B1), vitamin B12 deficiency (seen in

bowel absorption problems), drugs (e.g.

ethambutol and isoniazid used in the treatment

of tuberculosis), and ingestion of methanol and

ethylene glycol (antifreeze).

The patients present with a centro-caecal

scotoma and progressive loss of vision.

Smoking cigarettes exposes an individual to

cyanides which may play a role in this disease –

another reason (if one were needed!) not to

smoke.

Some of the effects may be reversible,

particularly in that related to ethambutol

ingestion for TB treatment (these patients are

usually warned about visual loss, but anyone

presenting requires urgent referral).

For the other forms of toxic neuropathy,

referral is not as urgent: vitamin replacement is

attempted using thiamine infusions or vitamin

B12 injections, often without much success.

LeberÕs hereditary

optic neuropathy

This is an interesting, but rare, cause of optic

neuropathy. It is inherited through

mitochondrial mutations, which means that the

inheritance is through the maternal side.

It affects men far more than women (9:1)

and the peak incidence is in the teens. There is

a rapid onset of unilateral loss of central vision,

followed by the other eye within a year, often

in the context of a family history.

Examination acutely shows pseudo-disc

oedema (the disc looks swollen, but does not

leak on fluorescein angiography) and

circumpapillary telangiectasia (web-like dilated

blood vessels). Visual loss is variable but often

severe.

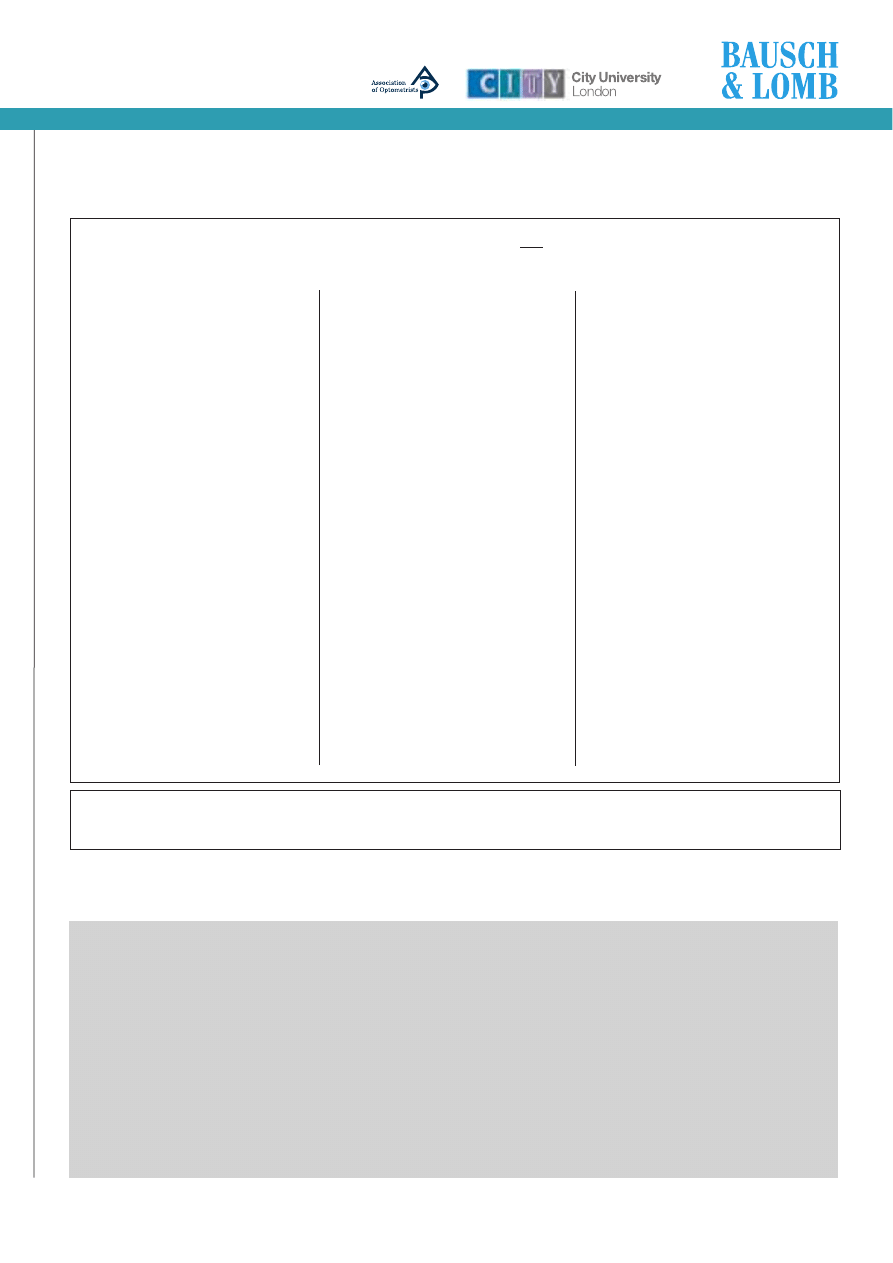

Figure 2 Anterior Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy

Figure 2a shows the discs of a 48 year-old man with AION affecting his

right eye, with a classic pale swollen disc associated with a nerve fibre layer

haemorrhage, and the small “disc at risk” can also be noted in the left.

Figure 2b shows the same patient’s discs photographed 9 months later: he

has optic atrophy in the right disc but has unfortunately presented with

vision loss in his left eye and has AION affecting this eye now.

sponsored by

www.optometry.co.uk

31

Module 2 Part 8

sponsored by

Papilloedema

Papilloedema is defined as swollen optic discs

due to raised intracranial pressure, and it is

very important to recognise the signs. If

papilloedema is detected, emergency referral is

required. Many patients will present with

headache, and it is important to be able to

exclude swollen discs. The history will often

help, as detailed above, and sometimes

patients may complain of obscurations, sudden

blanking of the vision lasting seconds, often

with postural changes or the valsalva

manoeuvre (which increases intracranial

pressure).

The practitioner must try to differentiate

papilloedema from pseudopapilloedema, the

causes of which are discussed below.

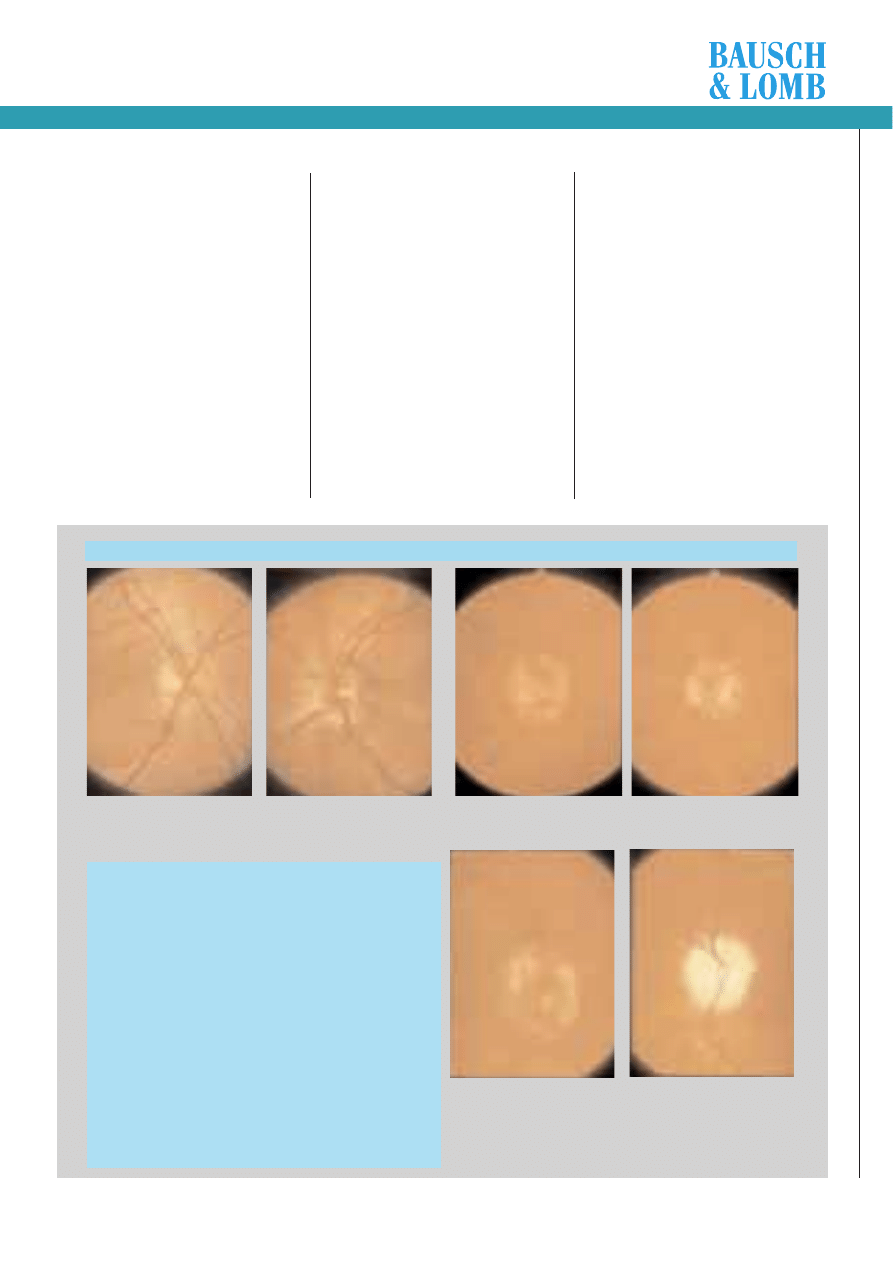

Papilloedema has been divided into early,

acute, chronic and vintage stages – the latter

stages are usually extremely obvious, but it is

the early changes that may be difficult to

detect (Figure 3 a,b,c). Remember that

children can also present with papilloedema, so

attempt to examine their discs when they

present with headaches.

The signs of papilloedema can be divided

into mechanical and vascular, and they are

detailed in Table 3. The early signs are the

important ones: blurring of the optic disc

margins as nerve axons swell, hyperaemia of

the disc and loss of spontaneous venous

pulsation. This is an important sign, as when

spontaneous venous pulsation is present, raised

intracranial pressure is extremely unlikely. The

best way of observing this is with the direct

ophthalmoscope, and to look at a vein just as

it leaves the disc margin. In 80% of normal

subjects, the veins can be seen to pulsate.

Although it is not present in 20% of normals, it

can sometimes be induced by gentle pressure

on the side of the globe.

The two main causes of pseudo-papilloedema

are hypermetropic discs, which are small and

crowded and therefore may appear swollen with

an absent optic cup, or myopic tilted discs which

appear swollen superonasally (Figure 4 a,b).

Obviously hypermetropes can get papilloedema,

so in these patients where spontaneous venous

pulsation is absent and there is a suggestive

history, referral may be required. The other main

diagnostic confusion is with buried disc drusen,

which are discussed later. These are commonly

associated with abnormal retinal vasculature, in

particular trifurcation of retinal vessels at the

disc, so look at the vascular pattern when

querying the diagnosis of papilloedema. Finally,

papilloedema is often associated with secondary

vascular changes as detailed in Table 3.

Table 4 details a systematic approach to

whether papilloedema is present or not.

Once a diagnosis of papilloedema has been

made, particularly with symptoms in keeping

with the diagnosis (headache and obscurations),

and visual field analysis showing an enlarged

blind spot, other neurological signs can be

looked for. These include a sixth nerve palsy (‘a

Figure 3a shows blurring of the nasal optic disc margin and a hyperaemic

disc, and it would be important to look for lack of spontaneous venous

pulsation to confirm the suspicious appearance.

Table 3 Signs of Papilloedema

Mechanical

■ elevation of optic nerve head

■ Blurring of optic disc margins

■ Filling in of physiological cup

■ Oedema of peripapillary nerve fibre layer

■ Retinal and/or choroidal folds

■ Vintage: early pallor and white refractile bodies on disc surface

Vascular

■ hyperaemia of the disc

■ Loss of spontaneous venous pulsation

(20% of normals)

■ Anomalous vessels not present

■ Peripapillary haemorrhages (flame haemorrhages)

■ Exudates in the disc or peripapillary area

■ Nerve fibre layer infarcts (cotton wool spots)

Figure 3b shows established papilloedema with elevated nerve head and

loss of the optic disc cup.

Figure 3c shows vintage papilloedema in the right disc with some

refractile white crystals on the surface, and the left disc is already

atrophic due to chronic papilloedema – this eye has already lost

significant vision in a 24-year-old patient with idiopathic intracranial

hypertension.

These three sets of optic disc photographs show early, established and chronic papilloedema.

o

t

June 30, 2000 OT

www.optometry.co.uk

32

pseudo-localising sign’ – the nerve is

stretched by the raised intracranial

pressure) resulting in diplopia. Again, it

is important to note that visual function

in papilloedema is often normal, and

visual field constriction only occurs in the

late stages.

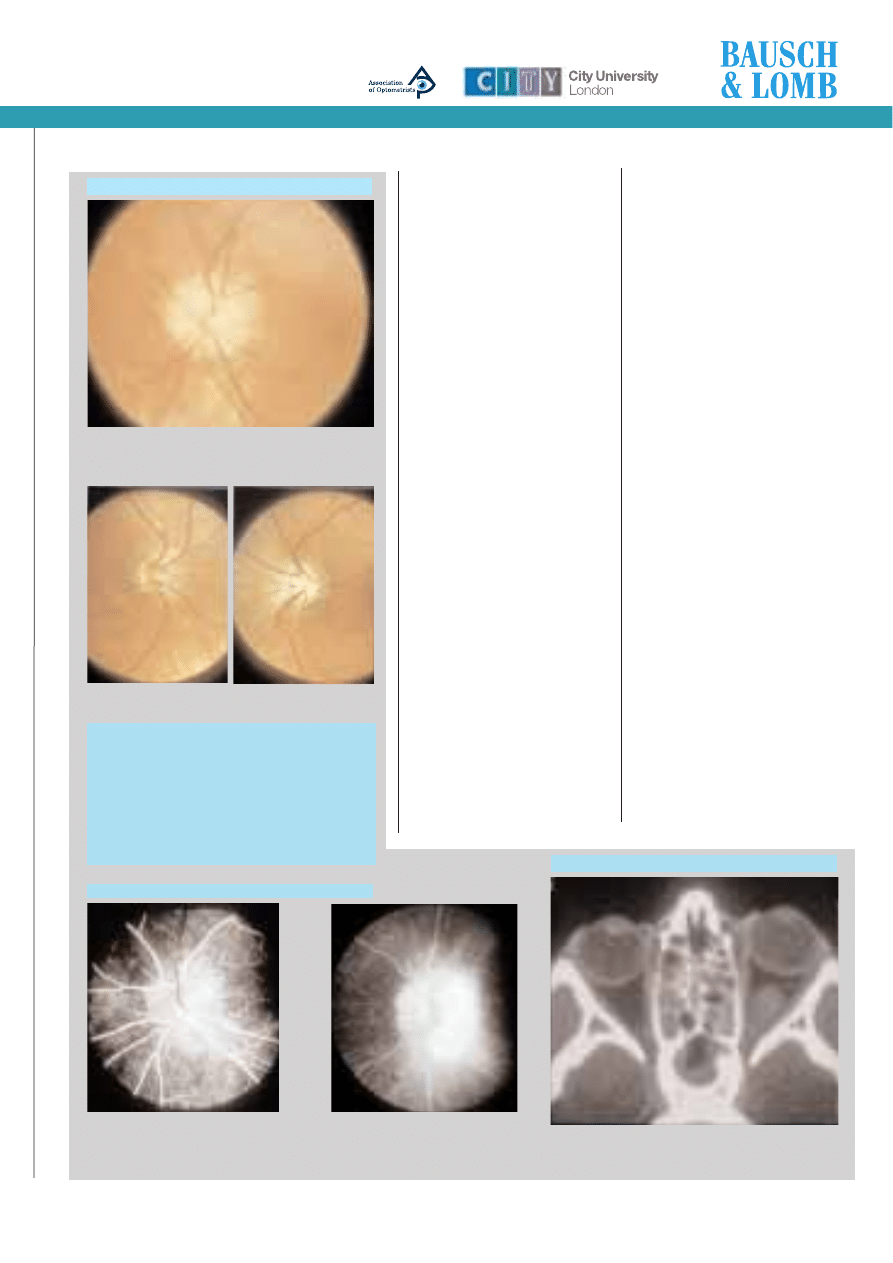

If there is doubt about the presence

of swollen discs, fluorescein angiography

is helpful (Figure 5 a,b). The early

angiogram shows a dilated capillary

network over the disc, and the late

angiogram shows leakage of fluorescein

from the disc.

The causes of papilloedema include

intracranial mass lesions (brain tumours,

both benign and malignant),

hydrocephalus (blockage of the flow of

cerebrospinal fluid), meningitis and

idiopathic intracranial hypertension

(pseudotumor cerebri).

CT or MRI brain scanning will usually

point towards a diagnosis, and a lumbar

puncture is sometimes required, to

examine the cerebrospinal fluid.

Idiopathic intracranial

hypertension

(Benign intracranial hypertension)

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH)

was previously known as benign

intracranial hypertension, but it is not

benign as its main complication is

blindness. The American term for the

condition is pseudotumor cerebri. IIH

presents with headache and raised

intracranial pressure, but is not due to a

brain tumour.

The typical person affected is an

obese, young woman, with no other

neurological problems. Other associations

have been reported including

tetracyclines, steroid use/withdrawal, and

vitamin A, but the commonest is recent

Pseudopapilloedema

Figure 4a shows buried disc drusen. The disc looks swollen,

but note the irregular “lumpy” edge to the disc, the

anomalous retinal vessels and the yellowish appearance.

Figure 4b illustrates tilted small discs, which are sometimes

confused for swollen discs, especially the temporal edge.

Table 4.

Questions to ask when querying papilloedema

■ Is there a headache suggestive

of raised intracranial pressure?

■ What is the refraction of the eye?

■ Is there spontaneous venous pulsation?

■ Is there an anomalous retinal vascular pattern?

■ Are there other retinal vascular changes

(eg haemorrhages, exudates)?

Figure 5b shows the late photograph of

this disc with fluorescein leakage from

the optic disc.

Fluorescein angiogram of an optic disc with papilloedema

Figure 5a is the early arterial phase of the dye

transit and shows dilated capillaries over the

surface of the optic disc. The arteries are filled

with dye (white) and the veins still empty (black).

weight gain. The cause of the raised

intracranial pressure is unknown, but

probably involves reduced CSF drainage. A

venous sinus thrombosis can mimic IHH

and so a MRI scan is often performed to

exclude this condition. By definition,

patients suffering from IIH reveal normal

scans.

Treatment usually includes advice and

support about weight loss, which may

cure the raised intracranial pressure,

although this is often unsuccessful

because of the patients’ difficulty in

losing weight. Acetazolamide (Diamox)

reduces CSF production (as well as

aqueous secretion) and often improves

headache and pressure, but if there is

evidence of visual field constriction on

serial field measurements, shunting or

optic nerve sheath fenestration may be

required.

Shunting involves a neurosurgical

procedure to divert CSF from the lumbar

region into the peritoneum

(lumboperitoneal) or from the brain’s

ventricles into the peritoneum

(ventriculoperitoneal). An optic nerve

sheath fenestration involves slitting the

optic nerve sheath behind the globe to

create a window to allow CSF to leak, and

to also form a band of scar tissue to

protect the optic nerve head from further

damage.

Compressive

optic neuropathies

There are two main tumours which cause

visual loss by compressing the optic

nerve: the optic nerve glioma and the

optic nerve sheath meningioma

(Figure 6 a, b). 75% of gliomas present

with visual loss in first decade of life and

90% by the age of 20, so it is a disease

of young people, although there is a more

Compressive optic neuropathies

Figure 6a shows the CT scan of a child with a swelling of

the optic nerve which is an optic nerve glioma.

sponsored by

Congenital disc

anomalies

Congenital disc anomalies are

common, and are often confused

with papilloedema. They may also

give rise to visual field defects, or

be associated with central nervous

system defects and may cause

macular problems. The most

common anomaly that causes

confusion with papilloedema is

buried optic drusen.

Optic disc drusen

Optic disc drusen occur commonly, affecting

0.3% to 1% of the population. In this condition,

calcified hyaline-like material is deposited at the

optic nerve head for unknown reasons. It may be

inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, and

is usually bilateral (75% of individuals). It is

usually asymptomatic, but may cause visual field

defects. The diagnosis is usually obvious when

the drusen have appeared on the surface of the

disc, and a characteristic white, lumpy

appearance is seen, but when they are buried

there may be considerable confusion.

The features of optic disc drusen include an

irregular disc margin, an absent optic cup, with

anomalous branching of retinal vessels on the

disc surface (often a trifurcation of the retinal

vessels at the disc (Figure 4a)). The disc

appears pink/yellow, not hyperaemic as in

papilloedema. In addition, as opposed to

papilloedema, the veins are not dilated or

obscured by the swollen nerve axons.

No treatment is needed, but if doubt exists

www.optometry.co.uk

Module 2 Part 8

sponsored by

aggressive variant which can affect older people.

The glioma may be associated with

neurofibromatosis, a disease causing neuromas

(benign nerve tumours) on many nerves

throughout the body. The disease follows a

benign course and cannot be removed without

severing the optic nerve, so the usual

management is conservative. Occasionally surgery

is performed for cosmetic reasons in a blind eye.

It may behave in a more aggressive way in

adults and require more aggressive treatment.

Optic nerve sheath meningiomata,

meanwhile, affect adults, typically middle-aged

women, and present with a ‘classic’ triad of

visual loss, optic atrophy, and optociliary shunts.

These are shunt vessels between the posterior

ciliary and retinal circulation on the disc. If the

meningioma is intra-orbital, the patient may

present with proptosis. Some of these tumours

are hormone-dependent, so treatment is directed

to this end, and radiotherapy may slow down

spread. Surgery is difficult, as the tumour can

rarely be removed.

Figure 7b displays

myelinated nerve fibres,

and are commonly

misdiagnosed as

exudates.

Figure 6b shows the CT scan of a patient with an optic nerve

sheath meningioma which can be seen on the different cuts

as the tortuous thickened and calcified nerve sheath of the

right optic nerve (seen on the left of the picture). The optic

discs of this patient are seen in Figure 6c; the left disc is

normal but the right disc displays the classic triad of signs of

optic atrophy, disc swelling and optociliary shunt vessels.

as to whether there are drusen present (or if

there is papilloedema), their presence can be

confirmed on ultrasound (a dense shadow will be

visible) or on CT scan (a white calcium deposit

at the nerve head will be visible). Fluorescein

angiography shows autofluorescence

(fluorescence before the dye is injected into a

vein) and no late leakage.

Other congenital anomalies

Tilted optic discs and the small discs associated

with hypermetropia may cause confusion with

papilloedema (Figure 4b).

The important thing is to consider the

questions raised in Table 4, to ask yourself

whether these discs are in fact swollen or not.

Other congenital anomalies seen include optic

disc pits (which may cause a serous elevation of

the macula with subretinal fluid – Figure 7a),

myelinated nerve fibres (Figure 7b), which are

often confused with exudates, and colobomas

both of the optic nerve head as well as larger

ones involving the inferior retina due to

incomplete closure of the optic cup in utero.

In conclusion, the important points to

remember when diagnosing anterior visual

pathway disease are firstly to consider the

diagnosis, secondly to be able to discriminate

between congenital abnormalities of the optic

disc and papilloedema, and thirdly to be able to

look for signs of an optic neuropathy and to

consider the possible causes of this so that the

relative urgency of referral can be established.

The next instalment will consider disorders of

the optic chiasm and further back along the

visual pathway up to the visual cortex.

Congenital disc abnormalities

Figure 7a is an example

of an optic disc pit (a

small pit on the temporal

edge of the disc) which

may result in visual loss

due to serous fluid

leaking underneath the

macula.Figure 7a is an

example of an optic disc

pit (a small pit on the

temporal edge of the

disc) which may result in

visual loss due to serous

fluid leaking underneath

the macula.

33

Figure 6c

o

t

July 28, 2000 OT

www.optometry.co.uk

sponsored by

1. Signs of an optic neuropathy may

include all of the following except:

a.

central scotoma

b.

slightly reduced visual acuity

c.

relative afferent pupil defect

d.

absent spontaneous venous pulsation

2. Adult patients with optic neuritis

usually present with which one of the

following?

a.

peripheral field constriction

b.

pain on eye movements/headache

c.

a swollen optic disc

d.

bilateral visual loss

3. Which one of the following is correct

regarding non-arteritic anterior

ischaemic optic neuropathy?

a.

It typically affects females

b.

It occurs in large myopic “discs at risk”

c.

It may produce an altitudinal field defect

d.

Visual loss is always confined to one eye

4. Which one of the following is correct

regarding diabetic papillopathy?

a.

It is common

b.

It generally affects people with Type II

diabetes

c.

Bilateral swelling of the optic disc occurs

in 75% of cases

d.

Patients will generally complain of

extensive visual loss

5. Causes of toxic optic atrophy include all

of the following except:

a.

Vitamin C deficiency

b.

Vitamin B12 deficiency

c.

Methanol

d.

Vitamin B1 deficiency

6. Which one of the following regarding

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy is

incorrect?

a. It affects males more than females

b.

The peak incidence of the condition

occurs in the teens

c.

At the initial stages, patients suffer a

bilateral loss of vision

d.

Inheritance is through the maternal side

7. Patients with early papilloedema

usually present with which one of the

following?

a.

a central scotoma

b.

enlarged blind spots

c.

a relative afferent pupillary defect

d.

severe loss of vision

8. Clinical signs of early papilloedema

include which one of the following?

a.

optociliary shunt vessels

b.

retinal and choroidal folds

c.

loss of spontaneous venous pulsation

d.

venous sheathing

Multiple choice questions -

Disorders of the visual pathway: from the optic disc to the visual cortex

9. Symptoms of raised intracranial

pressure may include all the following

except:

a.

obscurations

b.

nausea and vomiting

c.

diplopia

d.

ptosis

10. Optic nerve sheath meningioma:

a.

peaks in incidence in the second decade

of life

b.

may cause proptosis

c.

rarely causes visual loss

d.

is associated with Neurofibromatosis

11. Optic disc drusen affects

approximately what proportion of the

population?

a.

1%

b.

5%

c. 10%

d.

50%

12. Optic disc drusen are usually:

a.

unilateral

b.

the cause of reduced visual acuity

c.

associated with anomalous retinal

branching

d.

caused by myelinated nerve fibres

An answer return form is included in this issue.

It should be completed and returned to: CPD Initiatives (NOE8),

OT, Victoria House, 178Ð180 Fleet Road, Fleet, Hampshire, GU13 8DA by September 6.

About the author

Chris Hammond trained as a senior registrar at St Thomas’s Hospital and the National Hospital for Neurology.

He has recently been appointed Consultant at Farnborough Hospital, Bromley NHS Trust.

Please note there is only ONE correct answer

Correction

Due to a typographical error, in CPD module 2, part 6, OT 2/06/00 page 34 under ‘Aetiology of nerve lesions’, the separation between the two images

increases in the direction opposite the side of the palsy ”and with” head tilt towards the side of the palsy.

34

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

więcej podobnych podstron