Komputerowe

wspomaganie zarządzania

projektami

Prowadzący:

prof. dr hab. inż. Zenon

Ignaszak

Opracowali:

Marcin Hołysz

Jakub Jędraszak

Wojciech Szarycz

Rok 2011/2012

Bibliografia

• I. BABUSKA, L. LI, “The problem of plate modeling: Theoretical and

computational results”, Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and

Engineering, 100(2), 1992, pp. 249-273.

• K.-J. BATH, “Finite element procedures”, Prentice-Hall Editor, ISBN:

0133014584, 1982.

• Y. BENHAFID, N. TROUSSIER., N. BOUDAOUD. “Towards the use of the

design of experiments method to control the quality of structural analysis”,

Sinaia (Rômania), 18-20 September, 2002, Mediarex 21.

• Y. BENHAFID, N. TROUSSIER, N. BOUDAOUD, Z. CHERFI. “Towards a

modelling assistance method in structural analysis. Application to a

terminal system of circuit breaker”, Proceedings of the 5th International

Conference on Integrated Design and Manufacturing in Mechanical

Engineering (IDMME'04), published by the University of Bath, UK, ISBN

1857901290, 2004.

• Y. BENHAFID, N. TROUSSIER., N. BOUDAOUD. “Méthode d’aide à

l’idéalisation de modèles issus de la CAO pour le calcul de structures“,

Mécanique & Industries, EDP Sciences, vol.6, n°3, 2005, pp. 289-296.

• M. BREUER. “Numerical and modeling influences on large eddy simulations

for the flow past a circular cylinder”, International Journal of Heat and Fluid

Flow, vol. 19, n°5, 1998, pp. 512-521.

• D. CASTILLO, C. DOUGLAS, D.R. MONTGOMERY. "Modified Desirability

Fonctions for Multiple Response Optimization", Journal of Quality

Technology, vol. 28, n° 3, 1996, pp. 337-345.

• S.C. CHAPRA, R.P. CANALE. “Numerical methods for engineers”, McGraw-

Hill, Editor, ISBN: 0071244298, 2005.

• W.Y. FOWLKES, C.M. CREVELING. “Ingénierie Robuste”. Dunod ed. Paris,

ISBN: 2100038109, 1998.

• P. KUROWSKI, B. SZABO. “How to find errors in finite-element models”.

Machine design, Paul Dvorak Editor, 25th of September, 1997, pp. 93-98.

• P. SCHIMMERLING, J.-C. SISSON, A. ZAIDI. “Pratique des plans

d'expériences“. Lavoisier Paris : Technique et Documentation, France, ISBN:

2743002395, 1998.

• D.A. SCHON. “The Reflective Practitioner: how professionals think in

action”, Arena Publisher, ISBN: 1857423194, 1991.

• N. TROUSSIER, F. POURROY, M. TOLLENAERE, B. TREBUCQ. “Mechanical

models management in engineering design”, Proceedings of the 2d

International Conference on Integrated Design and Manufacturing in

Mechanical Engineering (IDMME'98), Compiègne, France, Published by

Springer, ISBN 0792360249, 1998.

The control of the simulation quality and cost

using a multi-objective optimization method

and desirability functions

Kontrola jakości symulacji i kosztów za pomocą

wielo-celowej metody optymalizacji i funkcji

użyteczności

Yassine Benhafid

Université de Technologie de Compiègne, Laboratoire ODIC, BP 60319, 60203

Compiègne cedex, France, phone : 33 3 44234423 poste 42 21, fax :

33344235229, e-mail : yassine.benhafid@utc.fr

Nadège Troussier

Université de Technologie de Compiègne, Laboratoire ODIC, BP 60319, 60203

Compiègne cedex, France, phone : 33 3 44235230, fax: 33 3 44235229, e-mail :

nadege.troussier@utc.fr

Nassim Boudaoud

Université de Technologie de Compiègne, Laboratoire ODIC, BP 60319, 60203

Compiègne cedex, France, phone : 33 3 44237941, fax: 33 3 44235229, e-mail :

nassim.boudaoud@utc.fr

Abstract:

The simulation is a widely used tool for supporting the technical products

design. Numerous models have been developed until now that enable to take

into account the different levels in the accuracy of the physical phenomena

description. In addition, the simulation, and in particular structural analysis,

can be used to reach three different goals that are corresponding to three

different design contexts for using the simulation: the use of simulation in

order to understand a badly known phenomenon, the use of simulation in

order to compare the performances of various designs and the use of

simulation in order to validate the behaviour of a design.

Streszczenie:

Symulacja jest szeroko stosowanym narzędziem wspierającym projekt

techniczny produktu. Liczne modele stworzone do tej pory umożliwiają

uwzględnienie na różnych poziomach dokładność fizycznego opisu zjawiska.

Ponadto, symulację, w szczególności analizę strukturalną można wykorzystać

w celu osiągnięcia trzech różnych celów, które odpowiadają trzem różnym

kontekstom projektowym za pomocą symulacji: stosowania symulacji w celu

zrozumienia bardzo znanego zjawiska, korzystanie z symulacji w celu

porównania wykonań w różnych wariantach i wykorzystanie symulacji w celu

weryfikacji zachowania się konstrukcji.

Nowadays, the choice of the model adequate to a specific design context is made

by using the expert judgement. However, this judgement is often difficult to

achieve. Even if there are some experienced analysts, they need several iterations

in the analysis process to adjust the model to be used to reach the simulation

goal. The paper proposes to use a multi – objective optimisation method for

assistance to choose the model according to the kind of results to be obtained,

but especially according to the available time and the required accuracy of the

results to be obtained. The control of the quality and the cost of the simulation is

based on the use of the design of experiments, and on the evaluation of some

desirability functions to solve a multi-objective optimization problems.

Obecnie wybór modelu odpowiedniego do określonego projektu wykonywany jest

za pomocą ekspertyzy. Jednak decyzja ta jest często trudna do osiągnięcia. Nawet

jeśli jest kilku doświadczonych analityków, potrzebują oni kilku iteracji w procesie

analizy aby dostosować model, który ma być używany by osiągnąć cel symulacji.

Dokument proponuje wykorzystanie wielo-celowej metody optymalizacji przy

pomocy wyboru modelu w zależności od rodzaju wyników do uzyskania, ale

przede wszystkim w zależności od dostępnego czasu i wymaganej dokładności

wyników, które mają być uzyskane. Kontrola jakości i kosztów symulacji opiera się

na wykorzystaniu projektowania badań oraz na ocenie niektórych funkcji

użyteczności do rozwiązania wielu-celowych problemów optymalizacji.

Keywords: structural analysis, modelling, design

context, design of experiments, multiobjective

optimisation, desirability function

Słowa kluczowe: analiza strukturalna,

modelowanie, projektowanie kontekstowe,

projektowanie eksperymentów, wielocelowa

optymalizacja, funkcja użyteczności

Introduction

The use of simulation in the technical product design gains greater importance

during the recent years. One of its main advantages is its power to analyse non

existent products even before they exist. Many tools are used to simulate a real

product as the structural analysis for instance. The use of this tool in mechanical

simulation requires the management of different kind of hypotheses in order to

analyse the real complex system. In structural analysis, the idealization of a real

behaviour towards a model, that can be computed and solved, is a difficult task.

For the real system, when it will be used, a lot of factors and variations can affect

its structural behaviour. For instance, the material behaviour depends not only on

the material itself, but also on the heat treatment, the process, the environment of

use and so on.

Wprowadzenie

Zastosowanie symulacji w projekcie technicznym produktu nabiera większego

znaczenia w ostatnich latach. Jedną z głównych zalet symulacji jest możliwość

analizy produktu przed jego wprowadzeniem. Do symulacji wykorzystywanych jest

wiele narzędzi, jak na przykład analiza strukturalna. Wykorzystanie tego narzędzia

w symulacji wymaga od kierownictwa różnego rodzaju hipotez w celu analizy

złożonego systemu. W analizie strukturalnej, idealizacja zachowania w stosunku do

modelu, który można obliczyć i rozwiązać, jest trudnym zadaniem. Dla systemu,

kiedy będzie używany, wiele czynników i wahań może mieć wpływ na zachowanie

jego konstrukcji. Na przykład zachowanie tworzywa zależy nie tylko od rodzaju

materiału, lecz także od obróbki cieplnej, procesu, środowiska użytkowania itp.

However, it is nowadays impossible to take into account all these interactions

in an existing structural analysis model and choices have to be done.

Moreover, in an industrial context, the duration of the simulation, the

resources and the quality to be reached, influence these choices. The same

kind of choices among complex interactions between the technical system and

its environment all along its lifecycle leads to some idealization difficulties for

the boundary conditions, the geometrical simplifications, and the kind of

analysis (static or dynamic, linear or not). These simplifications choices imply

errors on the results obtained and must be controlled.

Obecnie jest jednak niemożliwe, aby brać pod uwagę wszystkie oddziaływania

w istniejącym modelu analizy strukturalnej, należy wybrać te, które muszą być

wykonane. Ponadto, w kontekście przemysłowym, czas trwania symulacji,

zasoby i jakość do osiągnięcia, mają wpływ na te decyzje. Ten sam rodzaj

wyborów wśród złożonych powiązań między systemem technicznym a jego

środowiskiem na każdym etapie cyklu jego życia prowadzi do pewnych

trudności idealizacji dla warunków brzegowych, uproszczenia geometrii i

rodzaju analizy (statyczne lub dynamiczne, liniowe lub nie). Te uproszczone

wybory oznaczają błędy w otrzymanych wynikach, co musi być kontrolowane.

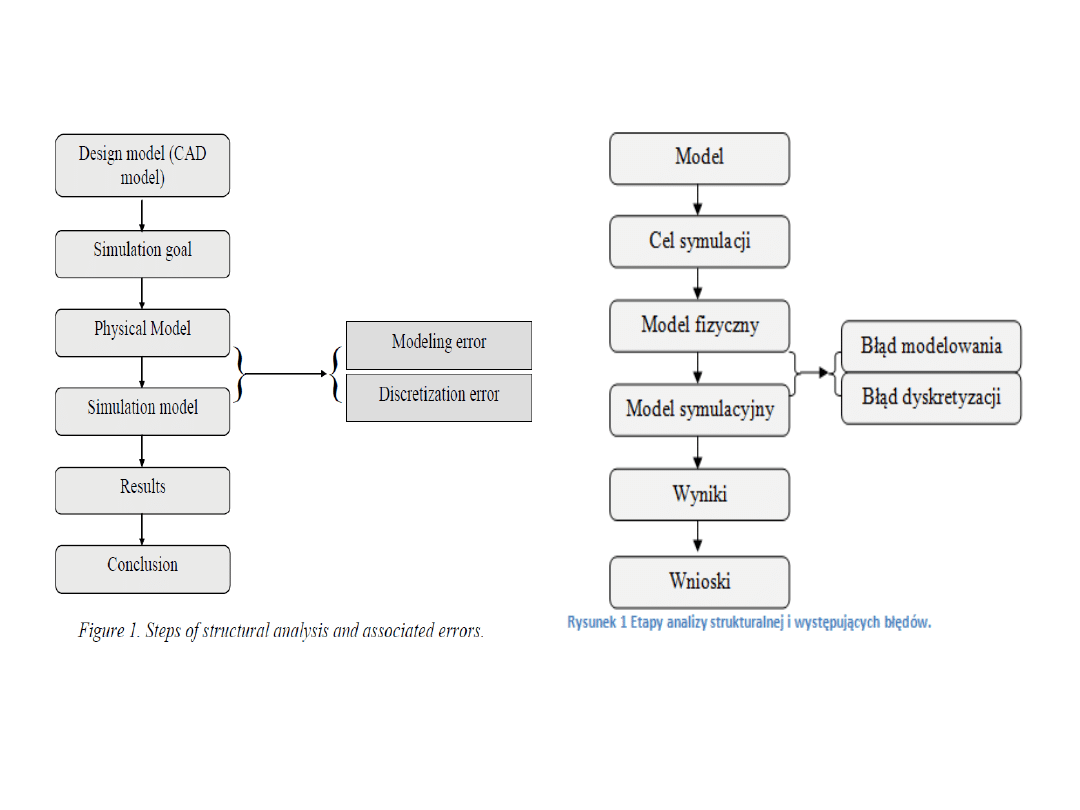

A first step of idealization aims at answering the following

question: what is the physical law that has a mathematical

formulation or that has a suitable model available? A second

step remains after considering the feasibility of the computation

of the physical model, with analytical or discrete methods. These

two steps correspond to the construction of the physical model

and to the construction of the simulation models presented in

Figure 1:

Pierwszy krok idealizacji ma na celu odpowiedzieć na następujące

pytanie: czym jest prawo fizyczne, które ma matematyczne

sformułowanie lub które posiada odpowiedni dostępny model?

Drugim krokiem pozostaje, po uwzględnieniu możliwości

obliczania modelu fizycznego, wybór metod analitycznych lub

dyskretnych. Te dwa kroki są zgodne z budową modelu fizycznego

oraz konstrukcją modeli symulacyjnych przedstawionych na

rysunku 1:

The structuring of the simulation process, presented in Figure 1,

points out two principal kinds of systematic errors involved in

the simulation process: the modelling error and the

discretization error. In order to achieve the discretization, some

authors propose methods and approaches allowing to control

these errors. However, the modelling error which needs to be

assessed by analysts. Nowadays, only human expertise can

help to control the modelling error control.

Strukturyzacja procesu symulacji, przedstawiona na rys. 1,

wskazuje dwa główne rodzaje błędów systematycznych

zaangażowanych w proces symulacji: błąd modelowania i błąd

dyskretyzacji. W celu osiągnięcia dyskretyzacji, niektórzy

autorzy zaproponowali metody i sposoby pozwalające

kontrolować te błędy. Jednak błąd modelowania, musi być

oceniany przez analityków. Obecnie tylko ludzka wiedza może

pomóc kontrolować błędy modelowania.

Physical modelling in the simulation

The first stage of a simulation skill is to idealize the real system towards a modelled

system. In other words, the analyst has to simplify the real system to be able to

model it by mathematical equations that can be solved by computational tools. In

this paper, we are focused on the necessary simplification of behaviour compared

with the real complex behaviour. The whole of these physical simplification

hypotheses of a studied system are chosen and formalized in the physical model,

depending on the aim of the simulation and the design context.

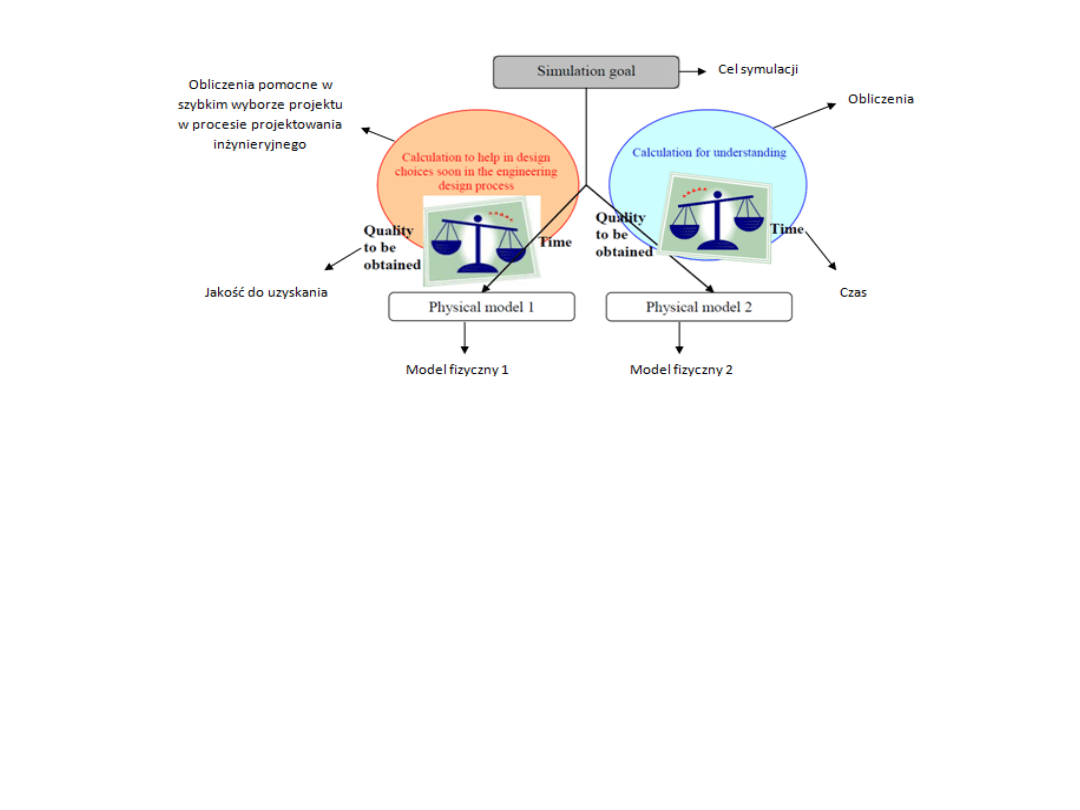

The aim of the simulation and the design context are characterized by three

parameters:

• the result to be obtained and the evaluation criterion that is associated to this

result,

• the quality level on the result to be obtained,

• the associated cost (the duration of the simulation).

Modelowanie fizyczne w symulacji

Pierwszym etapem umiejętności symulacji jest idealizowanie prawdziwego systemu

ku systemowi modelowemu. Innymi słowy, analityk ma na celu uproszczenie

prawdziwego systemu, aby mógł być modelowany przez równania matematyczne,

które mogą być rozwiązane przez narzędzia obliczeniowych. W niniejszym artykule

koncentrujemy się na koniecznych uproszczeniach zachowań w porównaniu z

rzeczywistym zachowaniem złożonym. Całość tych fizycznych hipotez

upraszczających badanego systemu jest wybierana i formalizowana w modelu

fizycznym, w zależności od celu symulacji i kontekstu projektu.

Cel symulacji i kontekstu projektowania charakteryzują trzy parametry:

• wynik do uzyskania i kryterium oceny, które wiąże się z wynikiem,

• poziom jakości wyniku do uzyskania,

• związany koszt (czas trwania symulacji).

Figure 2 Impact of the design context on the building of the physical model.

Rysunek 2 Wpływ kontekstu projektowania na budowę modelu fizycznego.

The Figure 2 shows that two different contexts of use for the simulation lead to two different

physical models. The objective is to have the result as fast as possible, with a quality on this

result that just enables the qualitative evaluation of designs. On the other hand, some other

simulations are driven to understand precise phenomena and are controlled by the quality of

the results to be obtained. Thus, the physical model to be chosen should provide a maximum

level of quality, even if the simulation is time spending.

Rysunek nr 2 pokazuje, że dwa różne konteksty wykorzystania symulacji prowadzą do dwóch

różnych modeli fizycznych. Celem jest, aby wynik był otrzymany tak szybko jak to możliwe, z

takim skutkiem jakości, że po prostu umożliwia jakościową ocenę projektów. Z drugiej strony,

niektóre symulacje są napędzane zrozumieniem precyzyjnych zjawisk i są kontrolowane przez

jakość wyników, które mają być uzyskane. Tak więc, wybrany model fizyczny powinien

zapewnić maksymalny poziom jakości, nawet jeśli symulacja jest czasochłonna.

The method which is presented in this article, aims at helping

in the choice of the models to be simulated by taking into

account the engineering design context, by using the quality

and cost (duration) specifications to be obtained.

Metoda, która jest przedstawiona w tym artykule, ma na celu

pomoc w wyborze modeli do symulacji biorąc pod uwagę

kontekst projektu technicznego, przy użyciu jakości i kosztów

(czas trwania), jakie mają być uzyskane.

Our approach. The choice of the physical model to answer the

goal of simulation requires at the same time some knowledge

on the methods and tools specific to the structural analysis

and the experiment of the professional according to [12]. The

use

of

knowledge

developed

on

a

previous simulation case is a way commonly used by the

analysts: this has been observed during a one year

experiment carried out in an industrial company. This

observation is the base of our approach that proposes to

develop a reference case and to use it for all the similar

simulation cases that have to be analysed (Figure 3).

Nasz sposób

Wybór fizycznego modelu odpowiadający celowi symulacji

wymaga w tym samym czasie pewnej wiedzy na temat metod

i narzędzi do analizy strukturalnej i profesjonalnych

doświadczeń zgodnie z [12]. Korzystanie z wiedzy

opracowanej w poprzednim przypadku symulacji jest

sposobem powszechnie używanym przez analityków: to

zaobserwowano

podczas

jednego

roku

doświadczenia

przeprowadzonego przez firmę przemysłową. Jest to

podstawą naszego twierdzenia, które proponuje opracowanie

przypadku odniesienia i używanie go we wszystkich

przypadkach podobnej symulacji, które mają być analizowane

(rysunek 3).

As described in the Figure 3, the references cases

are recurring cases which can provide knowledge on

the physical model to be chosen for a lot of similar

cases.

The similar cases are those which can be similar to

cases already analyzed and which can use

knowledge provided by the reference cases.

Jak opisano w rysunku trzecim, w owych

przypadkach występuję powtarzalność, która może

dostarczyć wiedzy na temat modelu fizycznego

wybieranego do wielu podobnych przypadkach.

Podobne przypadki to takie, które mogą być

podobne do analizowanych przypadków i które

opierają się na wiedzy z przypadków

The industrial experiment:

a recurrent knowledge for the choice of physical model

for various simulations during a one year period in an

automobile supplier firm, some observations have been made

in a Research and Development department and in a

specialized simulation department.

One of the most important points deals with the fact that the

knowledge of the physical model choice influence on the

result provided by the simulation is generic and appears

frequently in different simulations.

Doświadczenie przemysłowe:

powtarzająca się wiedza przy wyborze fizycznego modelu dla

różnych symulacje w okresie jednego roku w przedsiębiorstwie

dostawcy samochodów, niektóre obserwacje zostały dokonane

w

dziale

badawczo

-rozwojowym

oraz

w

dziale

specjalistycznych symulacji. Jednym z najważniejszych

punktów jest fakt, że poznanie fizycznego modelu wyborów

wpływ na wynik, który przewiduje symulacja jest i często

pojawia się w różnych symulacjach

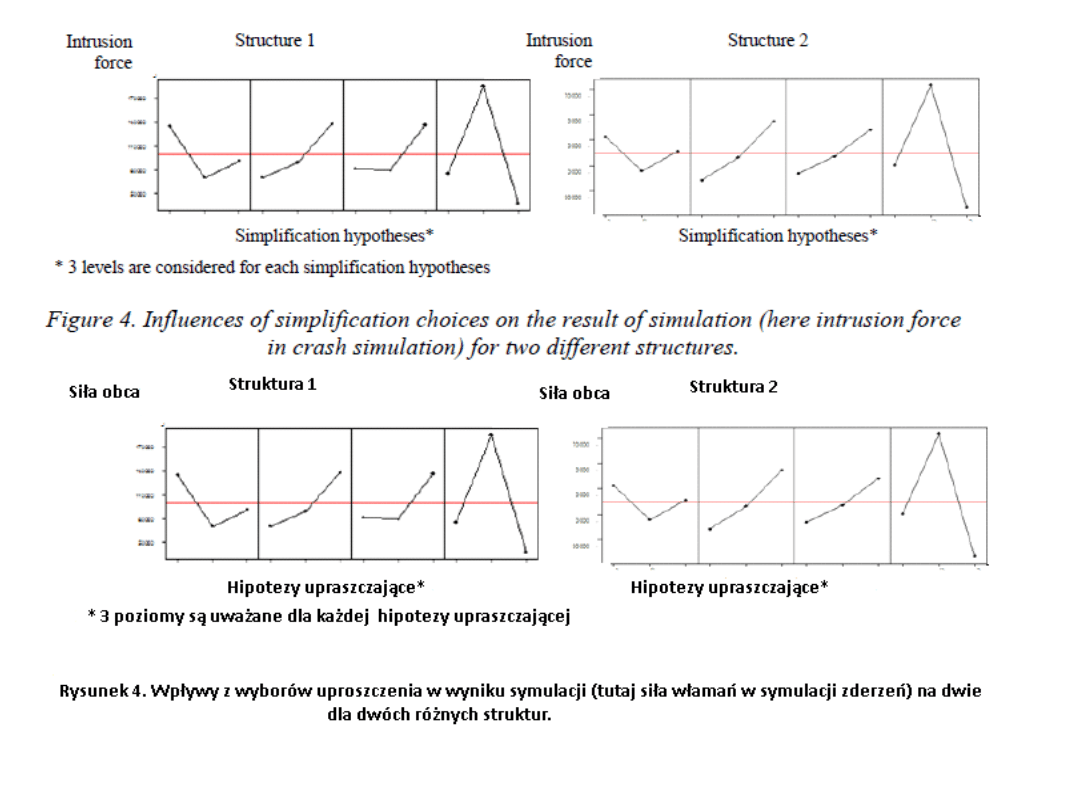

The Figure 4 shows the representation of the effect of different

simplification levels for different hypotheses (the boundary

conditions, the geometrical simplifications, the material behaviour)

on the intrusion force in crash simulation of two different structures.

It appears that the effect of the physical model choice is the same for

structure 1 and structure 2. In other words, the knowledge of the

effect of the hypotheses choices on the intrusion force can be used to

find a priori the physical model for simulating structure 2 and to

reach a good estimation of the intrusion force. The same kind of

representations of the influence of hypotheses on duration of

simulation has been made and leads to the same conclusion.

Rysunek 4 wskazuje efekty różnych uproszczeń na różnych

poziomach hipotezy (warunki brzegowe, geometryczne uproszczenia,

zachowanie materiału) na obce siły w symulacji zderzeń dwóch

różnych struktur. Wydaje się, że efekt wyboru fizycznego modelu jest

taki sam dla struktury 1 i struktury 2. Innymi słowy znajomość efektu

wyborów hipotezy sił obcych może służyć do znalezienia fizycznego

modelu dla symulacji struktury 2 i osiągnięcia dobrej oceny tych sił.

Tego samego rodzaju przedstawienie wpływu hipotez na czas trwania

symulacji zostały zrobione i doprowadziły do tych samych wniosków

The use of a reference case for helping in modelling choices

for a new similar case. In product design process, the

optimization of performances must take into account several

objectives to be reached. The aim of the optimization is then

to find the best compromises to fulfil the whole of the

objectives [8]. The formulation of optimization problems is

usually reduced to one objective function to be optimized

under several constraints. This objective function is built by

the combination of the different objective functions in the case

of a multi-objectives optimization.

Stosowania przypadku odniesienie pomaga w modelowaniu

wyboru nowych podobnych przypadków.

W

procesie

projektowania

produktu,

optymalizacja

parametrów musi być brana pod uwagę do osiągnięcia kilku

celów. Celem optymalizacji jest następnie znalezienie

najlepszych kompromisów do wypełnienia całościowego celu

[8]. Formułowanie problemów zazwyczaj redukuje do jednej

funkcji zoptymalizowanie kilku ograniczeń. Obiekt funkcji jest

zbudowany z kombinacji różnych funkcji celu w przypadku

wiele- obiektowej optymalizacji.

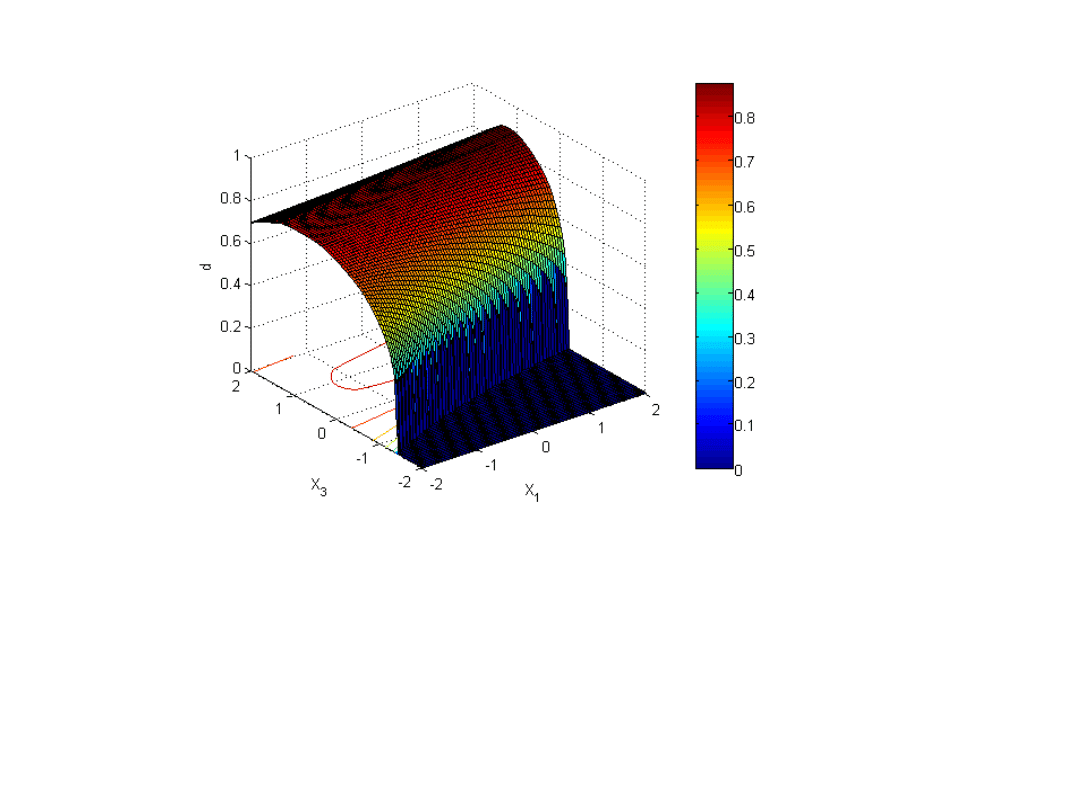

This combination is usually a weighted linear combination of the different

objectives functions. Other combination forms exist (loss functions, cost

functions, desirability functions). However, in our case, the desirability

function is an easily understandable concept because it corresponds to a

wish: to obtain a certain level of quality and of duration for the

simulation. This function is limited between 0 (minimum satisfaction

level) and 1 (maximum satisfaction level). In other words, the desirability

function makes possible to the user to subjectively evaluate the

relevance of the proposed optimums. For each objective function under

consideration, a desirability function is associated. By a combination of

each desirability functions, a global desirability is built (Figure 5). The

multi-objectives optimization problem is then to maximize the global

desirability.

Ta kombinacja jest zazwyczaj kombinacją liniową ważonej funkcji różnych

celi. Inne istniejące formy kombinacji (funkcje stracone, funkcje kosztu,

funkcje celu). Jednakże w naszym przypadku funkcja celu jest zrozumiałą

koncepcją, ponieważ odpowiada za: uzyskanie pewnego poziomu jakości i

czas trwania symulacji. Ta funkcja jest ograniczona między 0 (minimalny

zadowalający poziom) i 1 (poziom zadowolenia maksymalnego). Innymi

słowy funkcja celu umożliwia użytkownikowi ocenić subiektywnie

znaczenie proponowanego optimum. Dla każdej funkcji cel rozważanej

funkcji celu jest powiązany. Przez kombinację każdej funkcji celu, globalny

cel jest zbudowany (rysunek 5). Problem optymalizacji wiele- obiektowej

jest następnie zmaksymalizowany do globalnego celu.

Figure 5. Illustration of the global desirability function in the

case of two responses.

Rysunek 5. Ilustracja funkcji globalnych celów w przypadku

dwóch odpowiedzi.

To solve this problem, using the previous considerations, the methodology

follows several steps:

• step 1: To give the target (objectives levels) to be reached in terms of quality

and cost (duration for the simulation) and to formulate the associated

desirability functions,

• step 2: To simulate all the different physical models by using the

mathematical

functions that are provided by the reference case, and to evaluate the global

desirability of each physical model,

• step 3: To propose the physical models that correspond to an acceptable

level of the global desirability evaluation in order to achieve the new case of

simulation.

In the following section, an illustration is provided to show more precisely how

to build a reference case and how to use it to help to achieve the modelling

choices on a new case, similar to the reference one.

Aby rozwiązać ten problem, za pomocą wcześniejszego rozważania, należy

wykonać kilka kroków:

• krok 1: ustalić cel (poziomy celu), który zostanie osiągnięty pod względem

jakości i kosztów (czas trwania symulacji) i formułowanie funkcji skojarzonych

celów,

• krok 2: aby symulować wszystkie różne modele fizyczne za pomocą funkcji

matematycznych, które są świadczone przez przypadek odniesienia oraz do

oceny globalnego celu każdego fizycznego modelu,

• krok 3: zaproponowanie fizycznych modeli, które odpowiadają

akceptowalnego poziomu oceny celu globalnego w celu osiągnięcia nowego

przypadku symulacji. W poniższej sekcji ilustracji znajduje się bardziej

dokładnie jak budować przypadek odniesienia i jak go używać, aby pomóc w

osiągnięciu modelowanych wyborów jako nowy przypadek, podobne do

odniesienia pierwszego

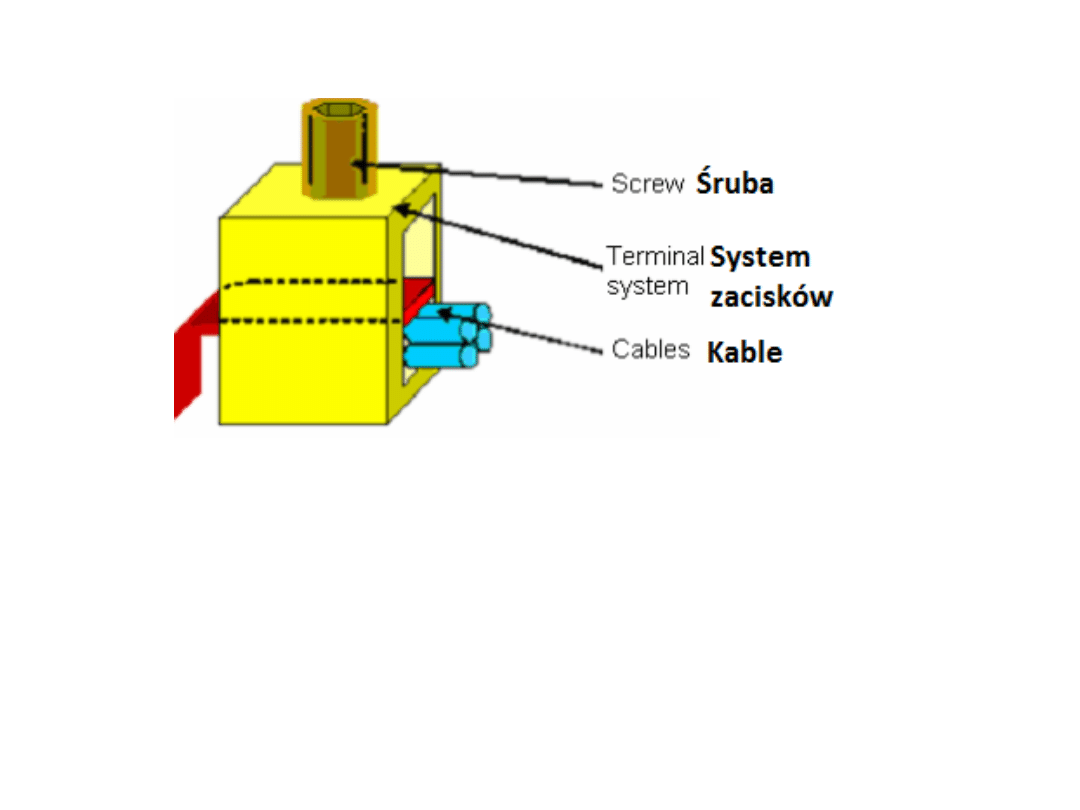

The application example of the modelling approach presented in this paper is

a terminal system of circuit breaker (Figure 6). In a circuit breaker, the

terminal system is used to connect electrical wires to the circuit breaker. The

several difficulties in the maintaining of the terminal system in a circuit

breaker are due to the resistance to the different electrical and mechanical

excitations. This work is focused on the study of torsion and traction

excitations applied on the terminal system. The objective of this work is to

guide an analyst to carry out his choices of the hypotheses of the physical

modelling in the analysis of the terminal systems.

Przykład zastosowania tego podejścia do modelowania, przedstawiony w

niniejszym opracowaniu jest system zacisków (Rysunek 6). W wyłączniku,

system zacisków służy do podłączenia przewodów elektrycznych do

wyłącznika. Kilka trudności w utrzymaniu systemu zacisków w wyłączniku

wynika ze względu na odporność dla różnych wzbudzeń mechanicznych i

elektrycznych. Praca ta koncentruje się na badaniu skręcania i trakcji

wymuszeń stosowanych w systemie zacisków. Celem tej pracy jest

poprowadzenie analityka do dokonania swoich wyborów hipotez fizycznego

modelowania w analizie systemu zacisków.

Figure 6. Description of the terminal system of circuit breaker.

Rysunek 6. Opis systemu zacisków wyłącznika.

The example shows the main steps for the exploitation of the results of a

reference case. The Figure 7 - A presents the reference case and the Figure 7

- B, the similar case for which the physical model to be implemented has to

be chosen.

Przykład pokazuje główne etapy dla eksploatacji wyników w przypadku

odniesienia .

Rysunek 7 – Przedstawia przypadek odniesienia i Rysunek 7 - B, podobna

sytuacja, w której model fizyczny do realizacji ma być wybrany.

Figure 7. The reference case and the similar case used for the illustration.

Rysunek 7.Przypadek odniesienia i podobny przypadek wykorzystany do

ilustracji.

Tabela 1.Ujednolicenie poziomów związanych z

poszczególnymi hipotezami fizycznych modeli.

Typ materiału

MA

Zachowanie izotropiczne

1

Zachowanie orotropiczne

2

Geometryczne

uproszczenie promieni

SDG1 Usunięcie promieni

1

Branie pod uwagę promieni 2

Geometryczne

uproszczenie gwintów

SDG2 Usunięcie otworu

karbowania

1

Branie pod uwagę otworu

karbowania

2

Geometryczne

uproszczenie niskiej formy

SDG3 Pełna forma niskiej części

systemu zacisków

1

Rzeczywista geometryczne

forma małej części systemu

zacisków

2

Geometryczne

uproszczenie wysokiej

formy

SDG4 Prosta forma dużej części

systemu zacisków

1

Rzeczywista forma dużej

części systemu zacisków

2

Uproszczenie sposobu

reprezentowania trakcji

(przyczepności) systemów

zacisków (systemów trakcji)

CL1

Dokładne obciążenie

(rozciąganie)

1

Punktowe obciążenie

(rozciąganie)

2

Powierzchniowe obciążenie

(rozciąganie i skręcanie)

3

Reprezentacja utrzymania

kondycji ze strony

CL2

Punktowe utrzymanie

1

Powierzchniowe utrzymanie 2

Reprezentacja kontaktu

pomiędzy liniami

CL3

Kontakt punktowy

1

Naciski powierzchniowe

2

Przemyślenia (rozważania)

na temat geometrycznej

nieliniowości

LG

Geometryczna liniowość

1

Geometryczna nieliniowość 2

Rozważania na temat

zachowania nieliniowości

materiału

LM

Liniowość materiału

1

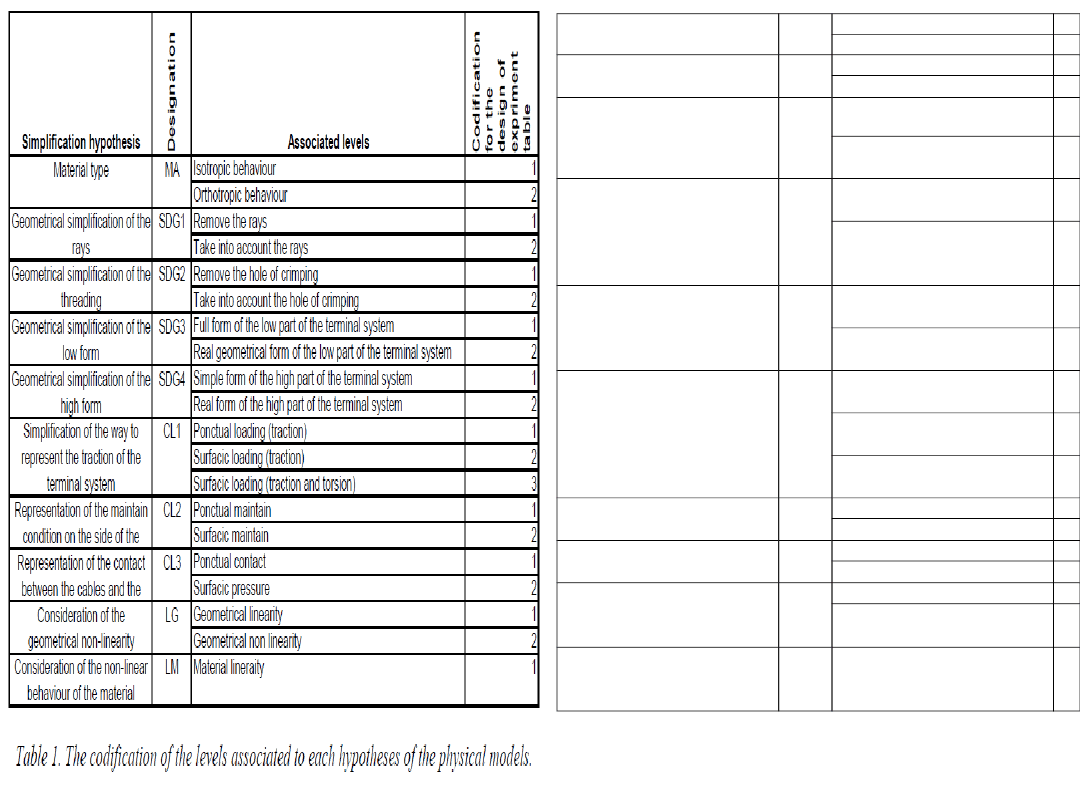

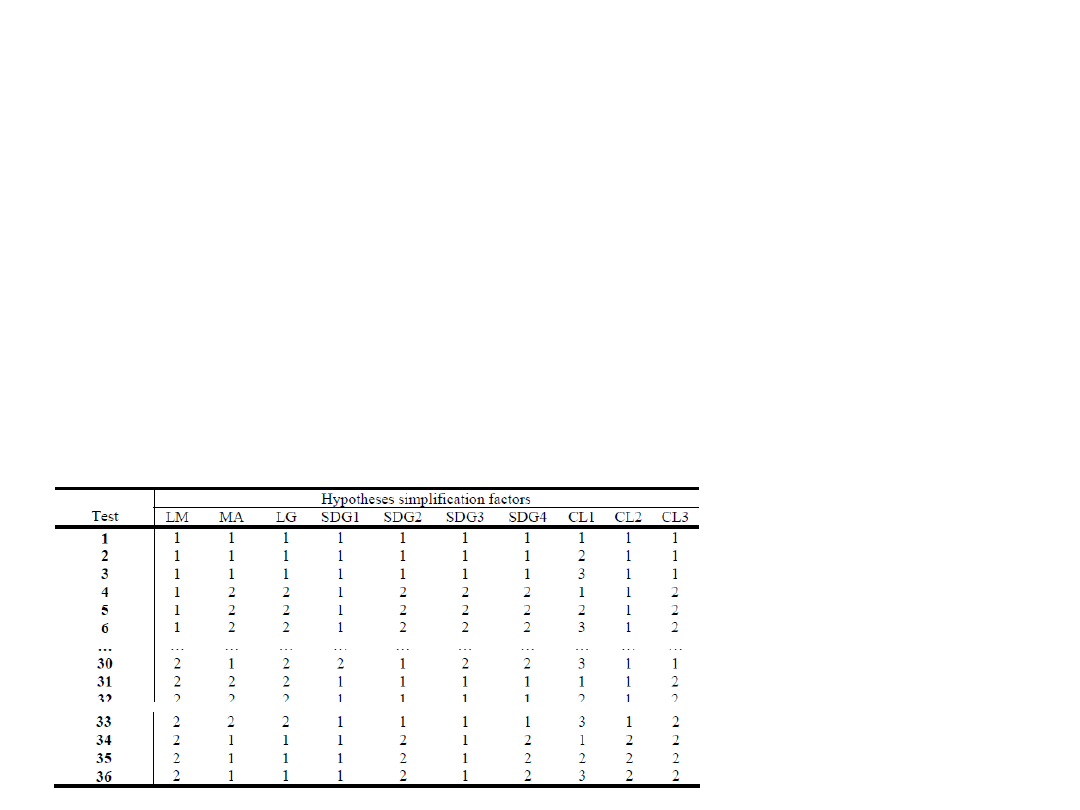

For the reference case (Figure 7 - A), an experimental table (Table 2) is achieved.

This table is a fractional experimental design composed of 36 physical models.

Therefore, the realization of this table gives us 36 results on Von Mises stress (at the

critical point : top level of the circuit breaker) and 36 results on computation

duration. The different hypotheses under consideration are those on material

behaviour, X MA (isotropic (1) or orthotropic (2)), on material linearity, X LM (linear

(1) or bilinear (2)), and so on (geometric linearity, geometrical details

simplifications, Boundary conditions…), as described in Table 1.

Dla przypadku odniesienia (Rys. 7 -), została wykonana eksperymentalna tabela

(tabela 2). Ta tabela jest ułamkowa, eksperymentalny projekt składa się z 36 modeli

fizycznych. Dlatego też realizacja tej tabeli daje nam 36 wyników na naprężenia von

Misesa w punkcie krytycznym: (górny poziom wyłącznika) i 36 wyników na czas

obliczeń. Różne hipotezy rozważane są na zachowania materiału, X MA (izotropowy

(1) lub ortotropowe (2)), na liniowość materiału, X LM (liniowy (1) lub dwuliniowy

(2)), i tak dalej (geometryczny liniowość, geometryczne detale uproszczeń, warunki

brzegowe...), jak opisano w tabeli 1.

Table 2. Extract of the

experiments table (table L36).

Tabela 2. Wyciąg z

eksperymentalnej tabeli

(tabela L36).

czynnik uproszczenie

hipotezy

test

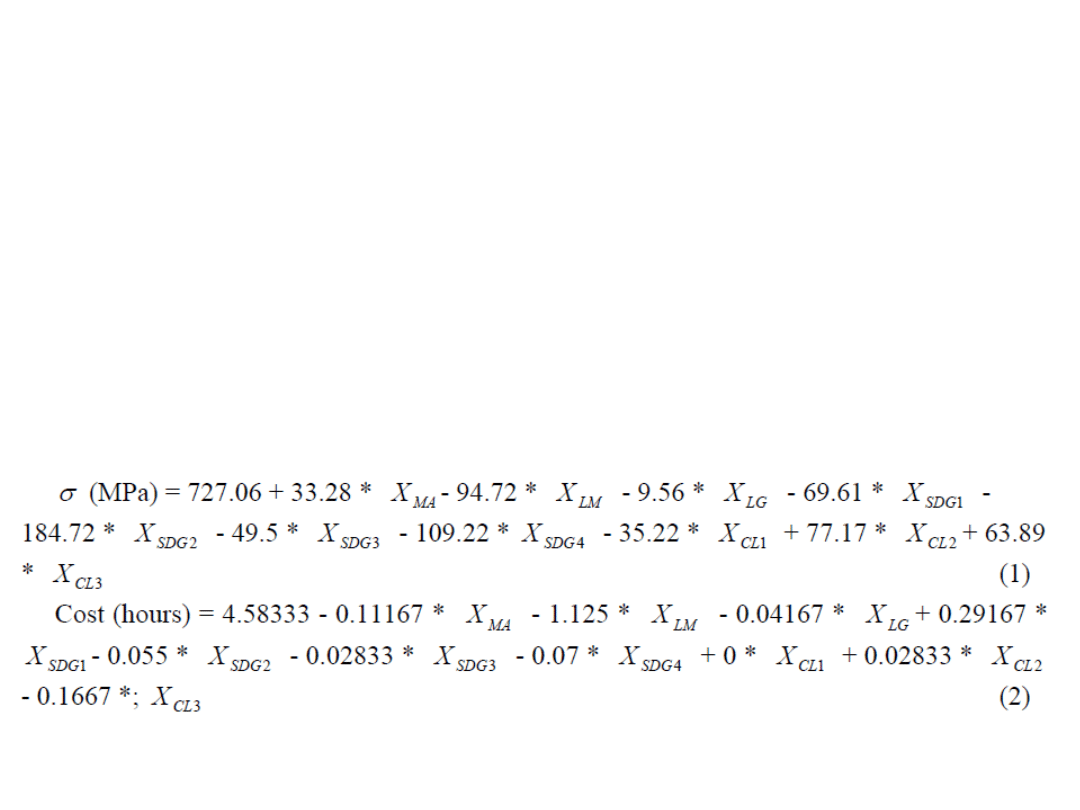

The equations (1) and (2) are the polynomial models developed with the 36 results

which are obtained by the simulations. The equation (1) is dealing with the Von Mises

stress evaluation at the critical point (top level of the circuit breaker), and the equation

(2), the cost evaluation (in terms of duration). Owing to the fact that the equations (1)

and (2) summarize the results of the influence study for the reference case (Figure 7 -

A), the physical model for a similar case (Figure 7 - B) can be selected, based on these

equations.

Równania (1) i (2) to wielomianowe modele opracowane z 36 wyników, które

otrzymywane są przez symulacje. Równanie (1) ma do czynienia z oceną naprężeń von

Misesa w punkcie krytycznym (górny poziom wyłącznika) oraz równania (2), ocena

kosztów (w zakresie czasu trwania). Ze względu na fakt, że równania (1) i (2)

podsumowanie wyników badań wpływu dla przypadku odniesienia (Rys. 7 -), model

fizyczny dla podobnej sprawy (Rysunek 7 - B) może być wybrany w oparciu na tych

równaniach.

For the new simulation case, by using the mathematical models (1) and (2), the whole

of the results for the possible physical models is generated. In our case, 1536 results

were generated in a very short time (less than one second on a basic office computer)

(Figure 8).

Dla nowego przypadku symulacji, za pomocą modeli matematycznych (1) i (2),

generowana jest całość wyników dla możliwych modeli fizycznych. W naszym

przypadku 1536 wyników zostało wygenerowanych w bardzo krótkim czasie (mniej niż

jedna sekunda na podstawowym komputerze biurowym) (rys. 8).

Figure 8. Distribution of results for

the terminal of circuit breaker:

complete field

Real tests of computations,

starting

from

a

mathematical

model.

Rysunek 8. Rozkład wyników dla

zacisku wyłącznika:

pełne pole

Prawdziwe

testy

obliczeń,

począwszy

od

modelu

matematycznego.

The context of simulation is then used via the specification of the objective functions.

The first objective function relates to the quality Q = 75% and the second objective

function relates to the cost (duration) of the simulation T<4 hours.

Konteksty symulacji są następnie wykorzystywane przez specyfikację funkcji celu.

Pierwsza funkcja celu odnosi się do jakości Q = 75% i druga funkcja celu odnosi się do

kosztów (czas trwania) symulacji T <4 godziny.

Figure 9. The different desirability functions : desirability function for the quality and for

the cost

Rysunek 9. Różne cele funkcji: funkcja użyteczności dla jakości i dla kosztów

The maximum value of the total desirability given by the

product:

*

is finally researched among the 1536 values of possible d. The optimal

model to be implemented is then the one which corresponds to the

maximum of d. In other words, it is the model which answers the best the

objectives of cost of simulation and quality on the Von Mises stress.

Maksymalna wartość całkowitej celowości dana przez

produkt:

*

jest ostatecznie zbadana pośród 1536 możliwych wartości d. Optymalny

model realizowany jest wtedy gdy jeden z nich odpowiada maksymalnej d.

Innymi słowy, jest to model, który najlepiej odpowiada celom kosztów

symulacji i jakość na naprężenia von Misesa.

In the case of the terminal, we find the results following with Q for the quality and T

for the cost: Q=76%,

T = 3 hours. The corresponding model to these values is defined by the levels of the

following hypotheses: isotropic material (MA=1), large displacements, large

deformations (LG=2), law of nonlinear behaviour (LM=2), consider the hole of

setting (SDG2=2), real shape of the geometry of the top of the terminal (SDG3=2),

real shape of the geometry of the bottom of the terminal (SDG4=2), surface effort

applied in top of the terminal (CL1=2), punctual effort applied in bottom of the

terminal (CL3=1).

W przypadku zacisku, znajdujemy następujące wyniki z Q dla jakości i T dla kosztów:

Q = 76%, T = 3 godziny Odpowiedni model do tych wartości jest określony przez

poziom następujących hipotez: izotropowy materiał (MA = 1), duże

przemieszczenia, duże deformacje (LG = 2), prawo zachowania nieliniowości (LM =

2), należy rozważyć otwór ustawienia (SDG2 = 2), rzeczywisty kształt geometrii

góry zacisku SDG3 = 2), rzeczywisty kształt geometrii dołu zacisku SDG4 = 2),

wysiłek powierzchni stosowany w górnej części zacisku CL1 = 2), ,Nacisk punktowy

stosować w dolnej części terminala CL3 = 1).

Conclusion

A methodology for assistance of modelling choice for mechanical structural

analysis has been proposed. It is based on the use of similarity properties

between different simulation cases [5]. The design of experiments is used for

structuring some reference cases, and the use of desirability functions and

multi-objective optimization provide some indication for a new simulation case,

similar to the reference one. The automatic treatment of the reference case in

order to provide the physical models acceptable for the new case has been

developed with MATLAB® software.

Wnioski

Metodologia pomocy wyboru modelowania mechanicznej analizy strukturalnej

została zaproponowana. Opiera się na wykorzystaniu właściwości podobieństwa

pomiędzy różnymi przypadkami symulacji [5].Projektowanie eksperymentów jest

używane do strukturyzacji niektórych przypadków odniesienia, a korzystanie z

funkcji użyteczności i wielocelowej optymalizacji prowadzi do dostarczenia

pewnych wskazówek dla nowego przypadku symulacji, podobny do tego

odniesienia. Automatyczne obróbka przypadku odniesienia prowadzona jest w

celu zapewnienia fizycznych modeli akceptowanych dla nowego przypadku który

został opracowany z oprogramowaniem MATLAB ®.

References /Odnośniki

[1] I. BABUSKA, L. LI, “The problem of plate modeling: Theoretical and computational results”,

Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 100(2), 1992, pp. 249-273.

[2] K.-J. BATH, “Finite element procedures”, Prentice-Hall Editor, ISBN: 0133014584, 1982.

[3] Y. BENHAFID, N. TROUSSIER., N. BOUDAOUD. “Towards the use of the design of

experiments method to control the quality of structural analysis”, Sinaia (Rômania), 18-20

September, 2002, Mediarex 21.

[4] Y. BENHAFID, N. TROUSSIER, N. BOUDAOUD, Z. CHERFI. “Towards a modelling assistance

method in structural analysis. Application to a terminal system of circuit breaker”,

Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Integrated Design and Manufacturing in

Mechanical Engineering (IDMME'04), published by the University of Bath, UK, ISBN

1857901290, 2004.

[5] Y. BENHAFID, N. TROUSSIER., N. BOUDAOUD. “Méthode d’aide à l’idéalisation de modèles

issus de la CAO pour le calcul de structures“, Mécanique & Industries, EDP Sciences, vol.6,

n°3, 2005, pp. 289-296.

[6] M. BREUER. “Numerical and modeling influences on large eddy simulations for the flow

past a circular cylinder”, International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, vol. 19, n°5, 1998, pp.

512-521.

[7] D. CASTILLO, C. DOUGLAS, D.R. MONTGOMERY. "Modified Desirability Fonctions for Multiple

Response Optimization", Journal of Quality Technology, vol. 28, n° 3, 1996, pp. 337-345.

[8] S.C. CHAPRA, R.P. CANALE. “Numerical methods for engineers”, McGraw-Hill, Editor, ISBN:

0071244298, 2005.

[9] W.Y. FOWLKES, C.M. CREVELING. “Ingénierie Robuste”. Dunod ed. Paris, ISBN:

2100038109, 1998.

[10]P. KUROWSKI, B. SZABO. “How to find errors in finite-element models”. Machine design,

Paul Dvorak Editor, 25th of September, 1997, pp. 93-98.

[11]P. SCHIMMERLING, J.-C. SISSON, A. ZAIDI. “Pratique des plans d'expériences“. Lavoisier

Paris : Technique et Documentation, France, ISBN: 2743002395, 1998.

[12]D.A. SCHON. “The Reflective Practitioner: how professionals think in action”, Arena

Publisher, ISBN: 1857423194, 1991.

[13]N. TROUSSIER, F. POURROY, M. TOLLENAERE, B. TREBUCQ. “Mechanical models

management in engineering design”, Proceedings of the 2d International Conference on

Integrated Design and Manufacturing in Mechanical Engineering (IDMME'98), Compiègne,

France, Published by Springer, ISBN 0792360249, 1998.

Document Outline

- Slide 1

- Slide 2

- Slide 3

- Slide 4

- Slide 5

- Slide 6

- Slide 7

- Slide 8

- Slide 9

- Slide 10

- Slide 11

- Slide 12

- Slide 13

- Slide 14

- Slide 15

- Slide 16

- Slide 17

- Slide 18

- Slide 19

- Slide 20

- Slide 21

- Slide 22

- Slide 23

- Slide 24

- Slide 25

- Slide 26

- Slide 27

- Slide 28

- Slide 29

- Slide 30

- Slide 31

- Slide 32

- Slide 33

- Slide 34

- Slide 35

- Slide 36

- Slide 37

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Ebsco Gross The cognitive control of emotio

The Hormonal Control of Sexual?velopment

Ebsco Gross The cognitive control of emotio

Microwave irradiation of hazelnuts for the control of aflatoxin producing Aspergillus parasiticus

The Discrete Time Control of a Three Phase 4 Wire PWM Inverter with Variable DC Link Voltage and Bat

the struggle over control of kievdimnik

The Discrete Time Control of a Three Phase 4 Wire PWM Inverter with Variable DC Link Voltage and Bat

Domjan M , Cusato B Pavlovian feed forward mechanisms in the control of social behavior

Kim Control of auditory distance perception based on the auditory parallax model

Ebsco Gross The cognitive control of emotion

Farina, A Pyramid Tracing vs Ray Tracing for the simulation of sound propagation in large rooms

Who s Pulling Your Strings (How To Break The Cycle Of Manipulation And Regain Control Of Your Lif

Pfeffer The external control of organizations

Barrow, John D Living in the Simulated Universe

Bostrom, Nick The Simulation Argument Some Explanations

Johnson, David Kyle Natural Evil and the Simulation Hypothesis

Bostrom, Nick; Kulczycki, Maciej A Patch For the Simulation Argument

więcej podobnych podstron