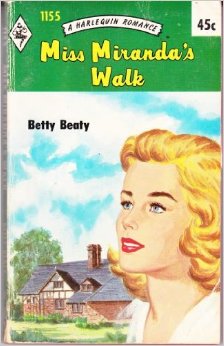

MISS MIRANDA’S WALK

Rosamund was not at all happy about the prospect of having a film unit invading her beautiful home. She could imagine only too well the chaos that would ensue. But what she had not foreseen, was the upheaval it was to cause in her private life as well.

CHAPTER I

The first warning was the stranger's voice calling out for the way to Holywell Grange. At least, I presumed he was a stranger. I didn't recognise his voice above the throb of his car engine, and if you're a schoolmistress in a place like Derwent Langley there are few people's voices you don't know. Not that I troubled about it at the time. Our home, Holywell Grange, is a small Tudor manor house, and especially in the summer, my mother, my sister Tanya (when she's home) and I get used to the odd sightseer who's done the church, and the cobbled High Street, with the smugglers' passage beside the market cross, finishing their tour with a peep over our overgrown hedge, or through the rickety gates.

More important still, I was sitting in the garden of the White Hart inn, sipping their real fruit strawberry milk shake with our neighbour Robbie Fuller. And when I'm with Robbie, I don't think I'd notice if a space ship full of green men had asked for the best route back to Mars. It's not because I'm in love with Robbie—I know a hopeless cause when I see one. It's just that he is one of the most attractive people I've ever met. He has that natural effortless charm that exudes an immediate sense of well-being. One always associates Robbie with warm sunny days—gold is somehow his colour—gold hair, tawny eyes, and as Tanya irreverently says, gold fingers too! For everything Robbie touched prospered. That particular Saturday afternoon was sunny too. There was hardly any wind, and above the high briar hedge that screened the garden from the road I could see the heat from the stranger's car shimmer up into the still air like a finger drawn across calm water. Up until then, and even for hours afterwards, I thought it was one of those days when everything goes well. I'd been up with the lark and got all my class's exercise books corrected, then I'd baked a record batch of gingerbread, and cut three dozen bunches of flowers. For though the three of us love the house dearly, it's almost impossible to keep up on my mother's pension and my schoolteacher's salary, for as Tanya has a flat up in town we can't expect her to contribute. So like lots of other householders we help out with selling produce. Every first Saturday of the month my mother takes it along to the W.I. market stall.

That's where I'd just delivered her in the horse and trap when I saw Robbie coming out of the Post Office, and he'd taken hold of Lady Jane's bridle and said, "You look all cool and pink and white in that dress. How about giving a poor thirsty driver a lift to the inn?"

That's how I came to be there, listening to the quick pant of the stranger's car, and the landlord's shouted instructions, "Down the 'igh, sir. Then left, sir, at the crossroads, sir. Then down the slope towards the river. Then you'll see it, sir, where there's a little old curl like in the river. An 'orseshoe bend. Can't mistake it, sir."

I remember Robbie raising his curious fair brows and laughing. "Must be very impressive, by the sound of old Fred. How many sirs did you count?"

I laughed. "I didn't."

"I made it five or six. Who is it, do you suppose?"

"I haven't a clue. A tourist, I expect."

Then we heard a shouted thanks. The car accelerated. I caught a quick flash of white through the screen of green, and then Robbie got up and peered over the top of the high hedge. "An American car by the look of it, Rosamund. He drives like the clappers. And it kicks up a helluva lot of dust." Robbie made an exaggerated gesture of dusting down his well-cut jodhpurs and silk shirt. He re-tied his yellow stock before coming back to sit at our table. "Maybe a rich uncle that you knew not of ? Or a cousin seven times removed who's struck oil in where-is-it-Miss Vaughan, please-teacher?"

"Texas."

"Right you are. A cousin seven times removed from Texas."

I shook my head. "No such luck," I sighed. "If he's a rich American, he'll be collecting brass rubbings. Or he'll want to look for the old passage. Or he'll want a picture of his missus and himself in Miss Miranda's Walk."

"Now you're boasting, Rosamund. They've never heard of Miss Miranda," Robbie mimicked the landlord's voice. "In li'l ole Texas."

"You'd be surprised. They put a bit about her in the National Trust guide. Anyway your rich American's out of luck. Mother's going on to see her friend Mrs. Mellor after the W.I. There's no one at home."

"Is there anybody there, said the traveller," Robbie quoted softly, "knocking on the moonlit door."

For no reason that I can think of, I shivered, as if a sudden wind had blown in over the Downs. But the afternoon was still hot and windless. No cloud had momentarily blotted out the sun. Hardly a leaf stirred on the rhododendrons, and the surface of the hotel's lily pond remained unruffled. There was not even enough breeze to disperse the white car's exhaust fumes. I could smell them faintly in the air as they mixed incongruously with the roses and the cut grass and the sharp tang of the distant sea.

Then Robbie laughed, and asked me for heaven's sake was I feeling cold? He ran his fingers playfully over my bare arm, and I shivered again, but this time with an almost apprehensive delight.

Though I promised him I wasn't in the least cold— whoever heard of anyone being cold on a sunny day in May?—he insisted on moving the little wrought-iron table directly into the sun. Although he's not more than twenty-six, and he seems to be comfortably off, and never had to worry about anything himself, Robbie is the most amazingly thoughtful person.

"Besides," he said, picking up the chairs one on either arm, "I can see you better that way."

He set them down by the table in the centre of the lawn. Then he sat down and tipped his chair backwards, folding his arms across his chest, and resting one foot nonchalantly on the crosspiece of the table. From under their light lashes his golden eyes surveyed me teasingly.

"You're looking as pretty as ever, Rosamund. That pink dress suits you. And yet, and yet..." he held his fair head on one side, "aren't those dark shadows under those lovely grey eyes? Isn't Rosamund's skin slightly wan? It's not to be wondered at, mind you. Coping with how many noisy brats is it...?"

"Thirty," I said. "And they're not brats."

"Have it your own way. Thirty-whatever-they-are." He smiled sweetly at me. "How you cope I shall never know."

He continued to stare up into my face, his eyes so full of an almost exaggerated concern that for a moment I thought "He really does care." My heart gave a sudden lurch, and so that he wouldn't read my eyes, I looked down at the table top, making patterns with my glass as bashfully as any schoolgirl.

"I tell you what," Robbie snapped his fingers together as if he'd just had a sudden inspiration. "I was only saying the other day—it's high time I got the cabin cruiser going for the summer again. I'll tell Jackson to get cracking on it. Then I'll take you out for the day, Rosamund. We'll go down river to the sea."

For a moment I said nothing simply because I couldn't really think of what to say. I'm not one of those fortunate people who have the right answer just like that, or who can fill a blank in with something polite and friendly and meaningless. Tanya is always telling me that I'd be useless in her line of business. Because a beautician has to say the right thing at the right time, which to quote Tanya is "But fast."

The reason was that an invitation from Robbie Fuller produced in me a curious mixed reaction. I suppose the crux of it was because I like him so much. Therefore I didn't want to get involved with him, when he was perhaps inviting me out of kindness or just filling in time between more eligible girls.

Although Robbie's parents had bought High Acres when Mr. Fuller retired from the city some four years ago, none of us saw Robbie for a couple of years after that. Apparently he was working as an engineer out in Malaysia, and he only came home when tragically his parents were killed in a car crash. Poor Mr. Fuller had not been much of a farmer, and the lovely rich Downland fields of High Acres had gone to ruin.

Robbie had installed a new manager, Mr. Jackson, to help him, while Mrs. Jackson did the house and the cooking, and Robbie himself had worked like a slave. Now the whole place prospered. The Fuller herd of pedigree shorthorns were quite famous. Robbie could afford to ride and ski, and keep his own boat.

I was still at teacher training college when Robbie came out of his work shell, and it was only six months ago that I first officially met him, when my mother gave an informal barbecue for my twenty-first party. Though Tanya (really it's Titania, ours being a Shakespeare-struck family—but Tanya suits her better somehow) knew him quite well. "And I promise you," she said, "be careful. He doesn't improve on acquaintance."

In the time he was here his name had been linked with quite a few girls, but I think that too was only village gossip. And though rumour had it there'd been some unhappy love affair, something told me he was the sort of man who could walk through life heart-whole and fancy-free.

Then noticing my hesitation, Robbie said casually, "Bring Tanya along if she's free."

I smiled. I said I would ask her, but as he knew, Tanya hardly ever was free.

"Yes, well, it was just a thought. Not to worry." Robbie laughed engagingly. "I prefer my pretty girls singly."

I laughed back, feeling myself drawn effortlessly into Robbie's powerful aura of well-being. A peaceful, companionable silence enfolded us.

Screened somewhere in the willow, a blackbird sang, and high in the bland blue above our heads two gulls wheeled like white weightless paper. A harvester driven probably by one of Robbie's men hummed distantly from the Downland fields. Dragonfly darted and hovered in incandescent green flashes over the lily pond. Bees hummed in the herbaceous border.

The air was full of flower scent, country sounds, and bird song. All was perfect. I didn't even notice that the exhaust fumes from the white car had drifted away. Because a long time ago I had forgotten all about the stranger.

CHAPTER II

I remembered him again when I arrived back at Holywell. The old brick entrance pillars have crumbled over the centuries, so that the wrought-iron gates, themselves rickety with age, are out of true. Everyone in Derwent Langley knows you have to wedge the left-hand gate with a block of wood to make them latch shut, but today the gates hung ajar and there were big fat tyre marks all the way up the soft shingle of the drive. I remember guiding Lady Jane in their tracks like someone treading in footprints on sea-wet sand, past the overgrown azalea beds, between the two sentinel macrocarpa trees, till rounding the curve of the drive, first the clump of three ancient oaks, then the house itself came into view.

Or rather I should say floats into view. For built in solid Tudor style though it is, the elevations of rosy mellow brick seem to have an almost ethereal lightness. A lightness accentuated by the yellow-green water meadows, the river, and the position in which it stands.

Set in shallow mid-Sussex just far enough back from the South Downs to lose little sunlight in their shade, but near enough to be sheltered by their shoulders from the strong south-west winds, Holywell Grange lies snug in a horseshoe bend of the meandering river Derwent. It is the first up the estuary from the sea and has been in my father's family for centuries, and though she has been a widow for the last twenty years, wild horses, or more formidable still, bank managers presenting overdrafts, couldn't drag my mother away from it. I have the same almost fierce affection for it, but that afternoon I wondered what the stranger thought of it all, seeing my home not through my own indulgent eyes, but his.

Did he miss the beautiful mullion windows, the lovely Tudor portico, the terrace, and see only the sagging roof, the chipped entrance steps, the chimneys that leaned southward like the Tower of Pisa? Did he turn to his wife and say, "This place, my dear, needs a fortune spending on it." As in our secret hearts my mother and Tanya and I know, but don't say. Just as we know that one of these days a big repair job will have to be done, and that will be the end of it.

Then Lady Jane trotted smartly right in front of the portico, obliterating the last of the tyre marks. Still high in the south-west, the sun caught the windows, making the ancient glass glow like beaten gold, drawing out the scent of the white geraniums in their stone tubs, striking a thousand silver sparks from the river bend. I drew my usual sigh of pleasure at coming home. I had a dozen small jobs that I had to do before my mother arrived home on the bus at six. Besides, if I was going out with Robbie next week, I might try to finish the flowered summer dress I'd just cut out, or if we were going down river as far as the sea, it might be better to wear my best linen slacks and finish knitting the sweater.

With nothing more important than such small decisions on my mind, I let Lady Jane have her head past the front of the house and then sharp left through the arch to the flagged stable yard. Her shoes clipped ringingly over the flagstones, sending our pair of fantails whirring up against the square of blue sky in mock-startled flight. Then she came to a practised halt by the old-fashioned trough. I stepped down, unharnessed her, and pushed the light trap into the old shed. Then I went back and sat on the corner of the trough, rubbing Lady Jane's nose while she drank her fill, watching the fantails descend again to the yard, walking hopefully in their quaint busy way to see if I'd left the lid of the feed bin open.

It was then that I noticed a white rectangle chalked out at the far end of the stable yard. I was still staring at it, puzzled, when the little carillon of tiny brass bells set in the wall above my head shook and clamoured as someone at the front door pulled the iron handle of the front door bell.

* * *

Though I'd heard no car in the drive, I knew who it was. I even knew exactly what he looked like. He was short and stout and he was both persuasive and insistent. I shouldn't have wondered if he'd wandered right round here while we were out, and marked out that chalked rectangle as a suitable place (though not the spot I'd have chosen) for the photo he had in mind. Not that I objected to that, but I have that English failing of believing one's home is one's castle, and I don't like people poking around when one's out.

So I didn't hurry. I tethered Lady Jane and hung her hay net on the hook in front of the stable, and before I'd had time to wipe my hands, the bell rang again. This time there was no mistaking the impatience. I could hear the high metallic sound slicing through the soft silence of the house like a knife through a honeycomb while the little back door carillon, which is set off by the same mechanism, almost capsized itself like little brass boats against the sky.

"All right," I called. "I'm coming!" Though no one could have heard through our big house with its thick walls. "Probably," I said to myself, "wondering, like those people last week, if we do cream teas. Or it's that anglers' society again, wanting to fish our bit of Derwent. Or a geography student doing a thesis on rivers that have bores."

My footsteps echoed across the flagstones of the scullery, then the kitchen, through the green baize door that separates the domestic quarters from the house proper, and then less sharply but more creakingly over the ancient polished oak timbers of the hall.

Whoever was there must have heard me coming, for they didn't ring again. Yet in some odd way I could feel their impatience as I struggled with the ancient lock hoop of the heavy door. I should explain that since our resources are so small for this house my mother and I, and Tanya when she's home, live almost exclusively in the kitchen, and our friends always come through the arch and yard to the door at the back. So the front entrance is only used by strangers and those are infrequent, so opening the door takes time. But eventually I got the rusty ratchets of the mechanism into line. I pulled the great door open. And there he was.

* * *

First I remember thinking was that he was quite different from what I imagined. He was the stranger at the inn all right, for there was the big white car parked on the other side of the drive. But he was tall and slim, and though the sun was behind him, and his face was in shadow, I could see he was very dark and quite young. The next thing I noticed was that for all his easy posture, somehow he matched his impatient ringing of the bell. For there was all about him a contained aggressive energy. An energy and an impatience too, that was carefully controlled under a relaxed exterior. But there all the same.

He was casually dressed in light-coloured linen trousers, navy linen shirt, and moccasins. Yet just as his surface manner seemed to belie his inner forcefulness, so these informal clothes conveyed an impression of throwaway elegance. His bare arms and face and neck were so deeply tanned that I wondered if he might not be English, but his voice when he said "Good afternoon" was as English as Derwent Langley's apple orchards. And it was certainly the voice I'd heard over the hedge at the White Hart.

While I returned his greeting, and for seconds afterwards we seemed to stand there studying one another. I don't know whether the expression was natural to him, or whether he didn't care greatly for what he saw, but his thick black brows were drawn together in a slight frown. He had very dark eyes too, of a curious shade of gem-hard blue. In fact not only his expression but the whole bone structure of his face conveyed an inflexible determination.

Then, finishing his inspection of me, from my sun-bleached wavy hair (rag-bag hair, Tanya calls it) to the tips of my sandalled feet, the stranger said, "I presume this is Holywell Grange."

"Yes, it is."

"Good." He raised one eyebrow. "For a moment I thought I must have come to the wrong place."

"Were you...

"I've already been here a couple of times today," he said, and to my own irritation I heard myself say apologetically, "Yes. I'm sorry. I had to go out."

"That's all right." He actually gave me a frugal forgiving smile of considerable charm. He had very white even teeth and the effect on his face was quite miraculous. The tough lines seemed to melt, the hard eyes crinkled up. "You weren't to know I was coming today."

"No."

"But this is the sort of day to see a place like this."

"Yes, I suppose it is."

So he was a tourist. Later in time I was to wish most fervently that he was exactly that, but at the time for some reason I was vaguely disappointed. I watched him back a couple of paces, the better to see the portico, and then I said, "The only trouble is that it's not open to the public."

"I should hope not indeed. That wouldn't do at all." He tossed me a vague surplus-to-requirements smile. "I wouldn't look at a place that was."

"You're welcome," I said coldly, "to see the outside, of course."

"I've seen it already, thank you. Back and front. And I like it. Now it's the inside I want to see." And when he saw that this arrogance had produced a quick flush to my face, he added with what he fondly hoped would no doubt soften my mood, "Besides, I am not the public. I'm Nicholas Pemberton."

At that point I felt my second pang of disappointment in him. If there is one sort of person I dislike it is the self-important variety. Then I noticed the stranger looked at me expectantly. After a second's pause he said softly,

"You don't know me?"

"To the best of my knowledge I've never met you in my life."

"All right," he shrugged his shoulders. "There's no need to sound so indignant." His voice was mildly amused.

"I'm sorry," I said, "but there it is. There's nothing of interest to see in the house. And anyway, my mother doesn't like..."

"So you're Miss Vaughan?" It wasn't so much a question as a statement. "You're Rosamund, in fact."

"Yes."

And though anyone in the village—Fred at the White Hart for instance, or Mrs. Peabody at the Post Office, could have told him that it was Tanya, the elder, the glamorous one who had the flat in London, yet his knowledge seemed to arm him against me.

"I didn't realise at first. You don't look like a school-marm." He made it sound a very unpleasant thing both to look like and not to look like.

"Really."

"Though perhaps," he smiled teasingly, "you sound a little like one." He paused, swinging himself back on his heels, tucking his thumbs into the waistband of his trousers, while he surveyed me at leisure. "So you're the one this place couldn't function without?"

"I wouldn't say that."

"Now don't be modest. Your mother says that."

"My mother?"

I felt rather relieved. Now I began, or I thought I began, to understand. Mr. Pemberton was the friend of a friend, or he knew a distant member of the family. The kind of person to whom you say oh, if you're on holiday in Sussex look up Mrs. Vaughan. I haven't seen her for donkey's years, and they have an interesting old place they'd like to show you around. In fact Mother and I had had such summer visitors before.

"Oh, that's why you said you weren't the public. I'm awfully sorry, Mr. Pemberton. I thought you were a tourist." This time my face was flushed in embarrassment. "I didn't know you knew my mother."

"But I don't."

"Well then, you know a friend of hers. Or a relation. I do apologise..."

But the stranger was enjoying himself. "I know you a little, that's all. On the other hand, I'm looking forward to making your mother's acquaintance."

"But she is expecting you?"

I felt so confused by this time, wondering who on earth he was and why my mother hadn't mentioned him, that I actually contemplated just asking him outright who exactly he was and what on earth he was doing here. And the sheer rudeness of that made me remember the rest of my manners. I stood back, and opened the door wide.

"She's not exactly expecting me, Miss Vaughan. Let's say she knew I was coming to see her. But she didn't know the precise date."

"Then perhaps you'd come in and wait for her. Tanya will be picking her up round about six." I waved a hand in belated hospitality. "If I'm permitted."

Half in self-justification, half in apology, I said,

"I'm sorry, Mr. Pemberton, but this is the first I've heard about your visit."

He made no comment on that. I doubt if he even heard me. He was staring down at the entrance steps. Almost as if now that he was invited inside he couldn't wait to take over, he said in a matter-of-fact, master-to-servant voice:

"Someone will break their ankle on these, Miss Vaughan. They'll have to be fixed for a start."

He shrugged his shoulders as if after all I couldn't be expected to understand, and then he gave a quick backwards glance at the terrace rose beds, the lawn, and beyond the water meadow, the glittering horseshoe bend of the river, before turning to come inside. I shall always remember that moment, just as he stepped into the house. For then the sun, aslant in the south-west sky, threw his long dark shadow ahead of him, over the threshold, and on to the sunlit boards of the hall. And suddenly I didn't want to close the door behind him, because I knew that from then on things would never be the same again.

CHAPTER III

My sister Tanya always says that I'm over-imaginative, but I'm sure that houses, especially old, much-lived-in houses, have different atmospheres for different people. And from the start I'm certain that the house resented him. It wasn't just the change from bright sunlight to the cool interior. It was something more. I had never till then noticed the silence of the hall. Beyond the thick walls and door, high summer with its country sounds and bird song was shut out. Within, no timbers creaked, not even a tap dripped. The only sound was our own breathing.

But if the house didn't resent him, I did.

"Ah, yes," he said. "Not bad. Not bad at all." He stood with his arms folded, surveying every detail, not in the polite indulgent way a guest might do, but as if he was memorising every detail, each crack, each warped window frame, each worm-eaten timber. "Now let's see..." He was thinking aloud, not bothering to address his remarks to me. "I’m six feet two ... if I stretch my arm, that's another couple of feet at least... mmm, not bad, I suppose."

"It's very good indeed. For the period, quite exceptional."

"Really? You of course being a schoolmarm would know. Historically I'm sure it's all you say, but for my purpose ..." He frowned.

"Just what is your purpose, Mr. Pemberton?"

But he had very convenient hearing, this stranger. I might never have spoken. He walked over to the window on the left of the door, and measured the depth of the sill with a quick expert hand. "Does it get much light in the morning?" he threw at me over his shoulder.

"Hardly. It faces west."

"Pity. Still, it's quite effective. So's the staircase ... wide...." He narrowed his eyes. "Couple up, couple down.

Yes. It could hardly be better."

After a few seconds' further contemplation, he started to walk toe to toe across the hall, and in a conversational voice, as if I were his willing ally in all he did, "One, two, three, four, five ... though I'd say my feet were bigger than twelve inches, wouldn't you, Miss Vaughan?"

"Much bigger." Then a new and disturbing idea suddenly blossomed in my mind. "Tell me, Mr. Pemberton," I asked breathlessly, "you're not by any chance an estate agent, are you?"

"Good heavens, no. Do I look like an estate agent?"

"I don't know. I've no idea what an estate agent is supposed to look like."

"Well, I'll tell you. They're very fearful-looking gentlemen, with long noses to smell out dry rot. Like you have here. And big eyes to spy out decaying beams." He stood on tiptoe, prodded the oak with his forefinger and a thimbleful of wood dust sifted across the sunlight down to the floor.

"But you're acting like one."

"Nonsense." He stared up now at the small minstrels' gallery, with its exquisitely carved balustrade and shallow alcoves of decorative plaster containing the oil paintings of some of our ancestors. "That looks a bit rocky to me. Wouldn't stand enough weight, I'd say. Besides, Miss Vaughan, an estate agent would have all sorts of gubbins to measure with. Slide rules, spirit levels, and what have you."

"So you're not actually an estate agent, but are you by any chance imagining this house is for sale?" The very words "for sale" made my voice tremble. But the stranger didn't notice. He actually laughed outright—a short burst of such unfeigned amusement which at any other time I might have thought attractive. Then he made one of those private jokey remarks to himself, which the solitary hearer is never expected to understand.

"You know at one time I thought that, too. When the price was mentioned I thought, She means me to buy it, lock stock and hold-up gunbarrel."

"Price?" I said. "Price of what?"

But once again he ignored me. Not deliberately perhaps because he was still absorbed. Then he shrugged his shoulders, and looked around. Unsmiling this time, he said, "No, Miss Vaughan, let me put your mind at rest. The thought of buying all this would never occur to me. Not even in my wildest dream. Or to be more accurate, shouldn't I say," he paused, "nightmare?"

"Then," I placed myself squarely in front of him, "before you go any further, I must ask you to explain what your purpose is."

"Explain what my purpose is." He repeated my words like Mr. Backhouse, our head teacher, does, with the questions of particularly inept pupils. "Oh, come now, Miss Vaughan, I don't think it would be proper for me to answer that. My purpose, after all, is with your mother."

"But I've let you in."

"Yes, of course you have. And if that's what's worrying you," he turned round, "I can always wait for her on the doorstep."

"No," I said, smiling reluctantly in response to his. "Of course not."

"Well then," he said, "let's call it a day, shall we? You agree to swallow your curiosity till your mother returns. And I'll promise not to do anything to get you worried. In fact I'll go so far as to say what I have in mind will help you keep the house. Now, how's that?" He smiled down at me this time like a kindly uncle towards a fractious child.

I don't know why I should have been so won over, but I was. I took the hand that he held out to me. It had a pleasant, firm, dependable grip. And when he said, "Is it a bargain, then?" I echoed the last word.

"A bargain it is," I said.

Then I led the way through the arch at the end of the hall and to the left, and showed him into the drawing room. "Sit down," I said. "The chairs are rather rickety, but they're quite comfortable." And I hurried along to the kitchen to make up for my rather rude reception by giving him a tray of tea.

* * *

When I carried it through into the sitting room, Mr. Pemberton was standing by the open french windows. Our sitting room is one of the loveliest parts of the house. It runs almost the entire length of it, so that cm the west there are windows which give a view of the drive, and on the south-east you can see the long fertile valley flooded with golden light, and the swell of the South Downs darkening sombrely as the sun slides into late afternoon. This is the garden side too, and the french doors set in the middle of the window open on to a circular flight of steps which lead to the lily pond and Miss Miranda's Walk.

"I was just admiring your lovely garden," Mr. Pemberton said. "Who does all this?"

"We all give a hand." I set the tray down on the deep windowsill and poured him a cup. He took it from me without moving from the window. I watched his eyes as he stood there admiring the pretty little complexities of our old-fashioned garden—the green cushions of London Pride with their straight flower stems and pink fairy hats, the crazy-paved paths, their cracks filled in with emerald moss, the pond, covered now from bank to bank with water lilies. But he was not just drinking in the beauty, of that I was certain.

"Takes you back a couple of centuries. Perfect! Absolutely perfect!"

I listened to the droplets of the fountain in the centre of the lily pond as they whispered and creaked on the lilies' polished leathery pads. Sometimes the sunlight split those droplets as they fell, made a quick rainbow, which vanished almost immediately. And my anxiety stirred like that and was gone as quickly again.

Instead, I took pleasure in his pleasure, seeing his careful unhurried gaze travel down the garden, and hover over the little stump of stone with the flat plate-shaped top and the scarcely decipherable inscription. Time and Derwent Langley weather had worn some of the letters away altogether, but the date—1609—still remained.

It is what Tanya and I called the sundial-that-isn't-a-sundial. For though it looks very like one, it is in the wrong position to tell the hours, and apart from the inscription at one corner, its round face has none of the figures of a dial.

I expected Mr. Pemberton to ask me what it was, and I had my little piece ready—how no one really knew what it was, but it had stood there as long as anyone could remember. It seemed to serve no useful purpose now, and though there was some sort of rusty mechanism at the base of the plate-shaped top, it had long since jammed or been broken. But his eyes slowly travelled further.

"Tell me, Miss Vaughan," he sipped his tea and nodded towards the far end of the garden, "what on earth is that place over there? It looks like a covered pathway. But it could be a loggia."

"Oh, that," I smiled, for this was one of my favourite subjects. "That leads all the way down to the river. It's called Miss Miranda's Walk."

"Ah, yes. Your mother did mention it." He thrust his hand into his trouser pocket and produced a leather notebook, and from a slot at the back brought out a thin packet of letters. There was no mistaking my mother's large and stylised handwriting. Nor was there any mistaking the photograph of Holywell on the other side, which I'd taken myself last summer. "In her second letter. That's right. There's a ghost story about it, isn't there?"

I said there was, and Mr. Pemberton made some remark about hoping the ghost wasn't around now, and I said no, she only appeared when, for some reason, the house was menaced. He then made one of those sarcastic little jokes to which he appeared prone, to the effect that the house was menaced right now—by woodworm and dry rot. And I almost asked him if he was the representative of one of those dry rot firms who do your house up in exchange for allowing them to use your house in their advertisements. But a truce was a truce, so I just, albeit feebly, smiled.

"Tell me more about Miss Miranda, then. I know you're dying to."

"Well, there's not much to tell. She was very beautiful, for one thing. There's a portrait of her in the minstrels' gallery—but not by anyone famous, unfortunately. She's not been seen for a very long time. She was supposed to appear when the Roundheads surrounded the place. And once when there was a bad fire. They say she came in the winter flood of 1609, when the Derwent burst its banks, and when the Great Bore sweeps up. But that only comes every once in an age."

"I see. She comes for hell and high water." Mr. Pemberton helped himself to another cup of tea. "Who was she, anyway?"

"A daughter of the house. Some ancestress of mine, I think. Her father had squandered her money, and he wanted her to marry a rich neighbour."

Mr. Pemberton ducked his tongue and sipped his tea. He didn't interrupt.

"But she ... Miss Miranda ... was in love with someone else ... a young fisherman. People said he was a smuggler on the side."

"People in italics have a knack of being right."

"Yes, well, Mr. Pemberton, they were about him. Anyway, smuggler or not, the family didn't approve."

"Quite right."

"And so they met in secret. He used to come down river from the coast, and tie up at the mooring. She'd signal him with a lantern if it was dangerous. Then they'd meet in the covered walk. Sometimes if he couldn't come up here, he'd send a message by a travelling tinker and she'd ride over the Downs to meet him. Then for weeks he didn't come. There was no message. So in the dead of night she saddled up and rode off to the coast. There they told her he'd been killed, shot by militiamen. And riding back Miss Miranda's horse fell in one of the chalk holes, and she broke her neck."

"Well, that's a grim story, if I may say so. What happened to her poor penniless father? I take it he didn't get a rich son-in-law? Or did he have another pretty daughter?"

"No. There was a young brother, that's all."

"But Father didn't die in a debtor's gaol, if they had them then?"

"Indeed no. Miss Miranda had left a will saying she wanted to be buried in the Walk, and when they dug it up, they found all the smuggler's loot."

Mr. Pemberton gave a disbelieving snort. "What's much more likely is that the whole family were engaged in smuggling, and they made up the story to explain a lot of stuff that shouldn't be found in any self-respecting landowner's back garden."

I said, "Well, maybe. Most families appear to have had a hand in it, then."

"And you, my dear schoolmarm, probably have smugglers' blood in your veins."

He touched my hand and smiled at me, and I smiled back at him. Then he was oblivious of me again, lost in whatever had brought him here. "Either way, though," he said enthusiastically, "it somehow adds authenticity to the story...."

And then I didn't listen any more. I didn't even look at him. I covered my eyes with my hands, the better to think. Now I knew. It was as if all along I'd been picking up tiny clues, jigsaw fragments. And that last unintentional remark of his was the final piece, the vital key.

"Pemberton," I said softly, under my breath. "Nicholas Pemberton." I actually saw the name in letters on the darkened retina of my eyes, as if my eyes were a wide cinema screen. For that was where I had seen the name before. In big credits at the beginning of a film. My eyes flew open. In a loud voice I said, "The Fly in the Amber. That was the film. You're Nicholas Pemberton. The Nicholas Pemberton, the film director. But what are you doing down here, Mr. Pemberton? ..."

And even before I'd got the question properly out, I answered myself. "Oh, I know now. I remember reading it in the paper. You're making a new film from some period novel ... The Moon Riders, isn't it?" My voice faded. I felt as if the floor was shaking under my feet. "You're looking for a setting, is that it?"

"Yes."

"An old house?"

"In fact I've found one."

"This?"

"Yes."

"You mean you want this house. Our house?"

"That is roughly the idea. "

"You intend to move a film company actually in here?"

He nodded.

"Take complete possession?"

"Yes."

I drew a long deep breath. It was as if my lungs were an old rusty pump handle and only a little breath could come up from deep down in the ground.

"Mr. Pemberton, you must see it's quite out of the question. We live here. This house is our home. We couldn't possibly do with a film unit here. Really, I can tell you here and now. You're wasting your time. My mother will say exactly the same." I picked up the tray in what was meant to be a gesture of dismissal, but the cups rattled so much that I put it down again.

And then I saw that Mr. Pemberton had brought out his horrid leather notebook again, and my mother's bundle of letters which somehow I'd forgotten all about. And this time he brought out another very official-looking document, and he spread it out in front of him.

"I'm afraid," he said softly, "that it's you, Miss Vaughan, who is wasting her time. Your mother has already given permission for us to use the house. Provided only that it proves satisfactory."

I said nothing, for the simple reason that I had neither anything to say nor breath to say it in. And even if I had, no words could have done justice to my feelings. Now it felt as if the floor gaped under my feet, as if the whole house was slowly subsiding. I was so shocked that when I heard the faint sound in the drive, I wouldn't have been surprised to see the ghostly Miss Miranda galloping her warning at top speed, and for ghostly lights to blossom even in the sunshine.

But the sound deepened to the note of a car engine. The only light was the sunshine glinting on the windscreen of Tanya's red Mini. Still in a disbelieving gaze, I followed Mr. Pemberton to the west window, the better to see my mother and Tanya alight from the car. He put the leather notebook on the table and leaned his hand against the stone mullions of the window.

Without meaning in any way to pry, but rather in the fascinated way that one stares at something which has brought bad news, I glanced down at the notebook. It had fallen open, not this time at Mother's letters, or the official-looking document, but at a photograph—that of a lovely redheaded girl.

A moment ago I would have sworn that nothing could have increased the apprehension which mingled with my anger. But the sight of the photograph did just that. Not because she was perhaps the most beautiful girl I have ever seen, but because in some curious way she bore such an uncanny resemblance to the painting in the minstrels' gallery of Miss Miranda herself.

CHAPTER IV

By nightfall the battle for Holywell Grange was over. Because the battle had never really begun. I had been disarmed, all my arguments discounted by that expression on my mother's face. It was a curious mixture of her tender maternal look, and triumph slightly tinged with disappointment. It was the expression of a parent about to hand over a marvellous present, only to find that the inquisitive offspring has already peeped into the parcel.

"The awful thing was, Mother expected us both to be delighted." I was perched on the edge of Tanya's bed while she sat at her dressing table, trying out some new La Pompadour preparation. Outside, beyond the undrawn curtains, the night was warm and sweet-scented, heavy with thunder to come.

"Well, I was, my love. Absolutely thrilled!" Tanya dabbed the end of her perfectly shaped nose with some stick foundation, and then held her head on one side to assess the effect. "It was a brilliant idea. And to think she kept it all to herself! I can just see her tearing out the advert and writing up. And never breathing a word. Who says women can't keep secrets?"

"She always was a great schemer for us, wasn't she?" I said softly.

"I'll say! And an avid reader of personal columns. And catalogues."

"It's rather like the time she got us Lady Jane. That was a personal column ad too. We didn't know anything about it till Lady Jane was delivered, d'you remember?"

"Will I ever forget? 'Free to good home,'" Tanya quoted, " 'spirited grey mare. Ride or drive. Needs some handling.' And we didn't even know how to begin. Well, we handled her. Or rather you did." Tanya's lovely greeny blue eyes met mine in the mirror. They sparkled mischievously. "Let's hope you can handle the film unit equally well."

"I think they'll be rather a different proposition."

"They?" Tanya asked innocently. "Or he?"

But I didn't rise to the bait. I asked her if she remembered the time Mother had ordered huge walkie-talkie dolls for our Christmas, the ones that were supposed to be so cheap because they were fire-damaged stock.

"Heavens, yes. And I'd been hoping for a lipstick and a manicure set, and you were wanting a snaffle bridle or something horsy."

I laughed for the first time since Air. Pemberton's arrival.

"Mind you," Tanya went on, "I could have told her that a home-bird like you would have set up a squawk. About the film unit, I mean."

"Well, I didn't, did I? I kept quite quiet."

"Yes. But all the same I could tell by the expression on Mr. Pemberton's face that you'd had your say before we arrived."

"Possibly I did. But then it was a bit of a shock. The whole idea takes a lot of getting used to."

"All the better." This time Tanya waved a brush dipped in a brilliant copper-coloured mascara. "You need to get out of the rut. To see a bit of life, my love. Think of all the interesting people you'll meet—film stars, extras, camera teams, technicians, press men."

"I've already met one of them," I said dryly. To not mad keen to meet the rest."

Tanya raised her brows, and then laughed. "Yes, I gathered it wasn't exactly love at first sight."

I said that was what was known as the understatement of the year, and Tanya said, "I should have thought a man who handles temperamental stars could make mincemeat out of a country schoolteacher."

We both laughed, and I said, "Well, I suppose in a way he did. I felt as if I'd been through a wringer, if that's what you mean." And then to tease her back, I said, "Anyway, he was different altogether to you and Mother. He seemed to like the look of you all right."

But her quickly indrawn breath made me look closely at her reflection in the mirror. I suppose it seemed strange that I should feel protective towards her. After all, she is eighteen months older than I am, and on the surface, much more sophisticated.

But Tanya has that vivid apparently gem-hard attractiveness that doesn't always make for happiness. She has a model's figure, tall and very thin, and an oval face with high cheekbones and good features. Her skin is a creamy white, and she wears her thick dark brown hair in a french pleat.

Of course, Tanya would say the whole effect is greatly enhanced by Madame Pompadour's beauty preparations, whose representative she is. Yet without the heavy makeup, the manicures, and hair rinses, she is just as attractive, but to me infinitely more vulnerable. For in some way, that eye-catching appearance attracts the wrong sort of man.

Now in the mirror I saw her curiously shaped eyes narrow. The hand upraised with the mascara brush halted in mid-air. I thought I saw a faint colour creep under her skin. Then she lowered her eyes and muttered something about having spilled the mascara. While she mopped up the non-existent drops, she obviously thought something out and came to some decision, for she swung round on the dressing-table stool and faced me.

"Do you really think he did?" she asked softly. "Like the look of me?"

"I'm quite sure he did."

"I," she said softly, "liked the look of him."

"So I noticed."

"Well, after all, someone had to be nice to him. Mother was all flustered. And I saw straight away that you hadn't exactly rolled out the red carpet. But"—she sighed as she watched my reflection in the mirror—"looking back, I think perhaps he, Mr. Pemberton I mean, was quite the most attractive man I've ever met." And for the life of me I couldn't tell whether she was teasing me or not. For Tanya can most devastatingly alternate utter seriousness with joking, frankness with deadly secrecy. Though I think I know Tanya as well as anybody else, I can never be quite sure what she feels.

Though I think I have always felt at the back of my mind, that when for a change she falls in love with a man instead of men falling in love with her, somehow it might well be the wrong one. But I think I had only a sixth sense to go on that Nicholas Pemberton was the wrong man.

Partly to test her feelings, and partly because the likeness still fascinated me, I told her about the photograph Mr. Pemberton carried.

"Oh, I know who that will be," she said. "That rings a bell. That must be Sylvia Sylvester. I read all about her in the Film Monthly. You know, the one we get at the salon for all the latest hair trends. This film is her big chance. They did a special interview on her. It's very touching really. Or you would find it so. Nicholas Pemberton discovered this fairly unknown actress, fell in love with her, and is going to make her a star. Mind you, I believe she's quite a girl. She's got a temper to match the red hair. I saw it in some other magazine. Since she was discovered, they call her The Temperament."

"In that case, they should be very well matched, Nicholas Pemberton and her."

"Always supposing that it comes to anything," Tanya said very softly, very thoughtfully.

"Tanya, what d'you mean?" And when all she did was smile, "Tanya, you wouldn't!"

"Why ever not? All's fair in love."

"If it is love. Even sometimes, not then."

"Now you're being very schoolmistressy. After all, it was you that gave me the idea."

"I did not!"

"Yes, you did. You said he obviously liked me."

"That's very different from..." I began. And then I said indignantly, "Oh, for goodness' sake, Tanya! What's got into you? Are you just teasing again? You can't be serious! You can have any man you choose. Why set your cap at someone who's engaged? And someone like Nicholas Pemberton. There are loads of men around here, decent types..."

I broke off in mid-sentence. Suddenly I remembered Robbie. In the midst of all the upheaval of this afternoon and evening, I had forgotten all about his invitation. Now it stood out in the confusion like a veritable lighthouse beam.

"And that reminds me, I saw Robbie Fuller this morning. He wants to take us both out in his boat on Saturday. Tanya, do try to come."

But whatever the invitation did to me, it only served to infuriate Tanya. She stood up. In fact, she actually stamped her foot. "Do you honestly mean to compare Nicholas Pemberton to Robbie Fuller? And do you have the nerve to say to me that Robbie is the decent type? You have absolutely no idea. No, thank you!" She tossed her head. "I wouldn't set foot on his rotten boat. And if you take my advice, you won't either."

And then I was angry too.

"Now you're just being beastly," I said.

We both stood facing each other, faces flushed, eyes sparkling. Tanya had shaken her head so vehemently that a wisp of her beautifully groomed hair had come loose. It hung over her pale face. She suddenly looked very young, a child in fact again. My mood melted. I said gently, "I'm sorry, Tanya, I didn't mean to get you worked up." I touched her arm and she smiled back at me.

Then I walked to the window, and leaned my arms on the ledge, staring out, gaining peace from the garden and the countryside beyond.

Though my anger had vanished, I still felt a curious almost physical ache inside. The film unit had not yet arrived, but already Tanya and I were tangled up in it. And we, who seldom even argued, had just been on the brink of a quarrel.

The moon had risen clear of the shoulder of the Downs. I watched it spangle the tiny ripples of the river bend, and flood the valley and the garden with its pale light. I could pick out each detail, every path, every shrub.

Only Miss Miranda's Walk baffled its radiance and lay secret as our future, under its impregnable shroud of matted ivy leaves.

CHAPTER V

That following Saturday must have been the first time for years that our old mooring jetty was used. Robbie brought Sea Nymph down river just before noon, and tied her up at one of the old posts.

Mother and I were at the back of the house, in the scullery, making an inventory of all the household items that would have to be put up in the attic to store when the film unit moved in, so we didn't see Robbie arrive. But we did hear him sound the little ship's bell, so we downed tools and strolled through the garden and Miss Miranda's Walk to meet him.

Though it had rained most of the week, it was a fine clear morning and the sun was drawing forth the smell of the earth and of fresh growing things. Cobwebs jewelled with dew festooned the box hedges. Strolling down Miss Miranda's Walk was like moving through a tunnel of translucent green light, and the air was as cold as a watercress stream. Even in our summer shoes, our footsteps echoed over the worn flagstones, the same flagstones that had been there when Miss Miranda herself had flitted at night down to the river to meet her shady lover. How different it was, I remember thinking, for me, in day and by sunlight! And I though Robbie Fuller isn't in love with me, he's a much more satisfactory companion than poor Miranda's smuggler.

I've never been sure just how much Mother likes Robbie. It's very difficult to judge because Mother is one of those people who literally likes everybody. This may partly account for the fact that everyone likes her, and for the way unpleasant people like Mr. Pemberton change character and eat out of her hand.

But even with Mother there are degrees of liking people, and I'm sometimes curious to know whether those benign grey eyes of hers regard Robbie with a high, medium, or low degree of liking. When I mentioned earlier this week that I'd be off sailing with him, she had seemed pleased enough, although she herself hates the water. My father was in the Navy and he was killed at sea when I was less than a year old, so it's understandable, really.

"Tell Robbie to watch the weather, darling," she had said. "These storms blow up so quickly, you know."

She repeated this to Robbie and me as he leapt nimbly on to the jetty to help me aboard.

"Don't worry, Mrs. Vaughan," he said. "I'm an experienced sailor. And the forecast's very good."

"But the locals never like too bright a June morning. Especially when the Downs are standing so clear."

Robbie laughed. "The locals never like anything, Mrs. Vaughan, as well you know!" He is a very good mimic, and he took off the rich Sussex burr. "They don't 'old with none of them lil' ole gadgets for telling the weather an' all. Wireless an' such like. They can do it all proper wi' a lil' ole finger an' a drop o' spit like."

Mother laughed and reminded him that we were locals, too, and enough of his nonsense. And Robbie promised he would take every care, not because the Downs were moving in like Birnam Wood to Dunsinane, but because he had precious cargo aboard. To emphasise his point, he slipped his arm for a moment round my shoulders and gave me a brief, almost brotherly hug.

I thought then that Mother in fact must like him very much, because she asked him to stay for supper when we got back and not to be late. Seven-thirty-ish we usually eat.

Then Robbie untied Sea Nymph, pushed clear of the landing stage, and started up the engine. Her screw kicked up a froth of white and sent small ripples slapping against the landing stage and the banks. The sleek lines of the little vessel vibrated under its power as Robbie turned the wheel and guided her into mid-stream.

Until we had rounded the horseshoe bend of the river, Mother stood, a slim girlish figure for all her white hair blowing in the wind, and waved.

My heart warmed to Robbie when he said, "You know, I adore your mother. I only wish I had one like her!"

I said yes, Tanya and I were very lucky.

I suppose it was natural then that he should say, "Talking of Tanya, I presume she couldn't or wouldn't make it? The trip today?"

"She didn't come down this week-end at all. She said she had some special demonstration to give. ’I’m terribly sorry."

"Well, don't be. I'm not." Robbie smiled as if he meant it, and that was all that was said.

The air was very still, and the river full, its surface smooth as silk. It's a glorious trip to the estuary because not one single habitation stands at the water's edge between Holywell Grange and the sea.

Just along here, the banks widen, and are lined with reeds and marsh grass. The steady putter of our motor filled the quiet, sending a reed-warbler chattering up into the sky, and echoing under the old stone bridge near Castle Langley.

From far away in its fold in the Downs, the village church chimed the half-hour.

"Isn't it marvellous?" Robbie said, taking a hand off the wheel and touching mine. "Everything is so uncluttered and peaceful! Everything is just the same as it's always been for centuries! That's what I like about this place."

It seemed somehow the cue to tell him about Mr. Pemberton and the film unit. So I said, "You're wrong, Robbie. Things aren't just the same as they've been for centuries. Or at least, if they are, they're not going to be for much longer."

"Don't tell me you're going to do a Tanya on us, and go off to find life in the big city?"

"No, I'm staying right here. It's life that's coming to find me. Or rather us."

"Rosamund ... whatever do you mean?"

"Just this..."

And I began the story of how Mother had read the advertisement that Nicholas Pemberton had put in the personal column for a period house, preferably with atmosphere. A house which might be a suitable background for shooting a script of The Moon Riders, the best-selling period novel about highwaymen. And how Mr. Pemberton ...

"By Mr. Pemberton," Robbie interrupted me, "I presume you mean Nicholas Pemberton, the director chap?"

"As a matter of fact, yes. But how did you know?"

"Oh, I've been around." Robbie smiled, took one hand off the wheel and tilted my chin playfully. "I've lived in the big world too, don't forget!"

I said yes, but somehow I always thought of him as being Sussex bred and born. And I remember thinking just then that oddly enough, although he was our neighbour, I really knew very little about Robbie.

Then Robbie said, "Well, go on! Don't suddenly come to a full stop! Nicholas Pemberton chose Holywell Grange, I presume, and has offered a tidy sum for the use thereof. Is that it in the proverbial nutshell?"

I smiled. 'It is, indeed!"

"But you're not going to accept?"

I didn't look directly at Robbie. I let my hand trail over the side, feeling the current catch at my fingers like tentacles. For one brief second I longed to tell Robbie how much I disliked the scheme, however necessary it might be. How Tanya and I had really known nothing about it, and how I feared that Mother would, in the end, be taken advantage of by this tough go-ahead character who had worked himself up in an industry famous for its ruthlessness. But the well-known Vaughan family loyalty would never allow me to breathe a word. After a while, I lifted my eyes to Robbie's face. He was looking down at me, his brows drawn together in a curious intent stare.

As lightly as I could, I said, "No, Robbie, we're not going to accept. We have accepted."

His face, which had just begun to clear, darkened again. An unnatural angry flush crept up under his skin. I remember thinking that I had no idea that the countryside, and Holywell Grange in particular, meant so much to him. Then he said softly, "I just don't believe it. I just can't believe it."

I folded my hands in my lap. "It's quite true."

"But you must be mad! Have you thought of what it will mean? The whole village will be inundated with them. They'll simply take over. Can you imagine it? The place won't be the same again I"

They were so much my own thoughts put into words that I said nothing. I just stared down at my hands, feeling the sun warm on my back.

"And Holywell Grange!" he exclaimed. "Once the peace of a place like that has gone, you never get it back! There'll be lorries all over the garden, churning up the lawns! Ramps made up the steps! Walls torn down! Doors made bigger! When you move back in you won't recognise your own home."

"We're not moving out," I said.

"You're not what?"

"Moving out. We're staying at Holywell. Mr. Pemberton promised Mother he'd make us a flat on the first floor. Two or three of the upstairs rooms that he doesn't want."

Now it was Robbie's turn to say nothing. He seemed to hold his breath for minutes on end, and then to let it out in a sudden explosion of righteous indignation.

"Mr. Pemberton has promised, has he?" Robbie said, using almost exactly the same words I had used to Tanya only a week ago. "How very kind of him! He's going to allow you a few rooms he doesn't want, in your own home I"

Suddenly I wanted to cry. The misery of agreeing with every word that Robbie said, and yet not really being able to say so, made my voice when I spoke both cold and terse.

"Well, it is our own home, as you say, Robbie. And we have to do with it what we feel best."

I stood up, I suppose on some sort of gesture of making that the final word on the whole subject. But the wheel-house deck of Sea Nymph is small, and we were in the shallow waves of the estuary. Our faces were very close together.

Swiftly, and almost totally without tenderness, Robbie bent and kissed my mouth. Then he said in a cold and level voice like my own, "On the contrary, Rosamund, it is not only your own concern. It's your neighbours' concern, too. The whole village's, for that matter."

He put his hand under my chin and tilted my face. Quite softly and studying the effect of his words carefully as he spoke, he said, "Come off it, Rosamund! I can't really believe you'd approve. Not of that sort of hare-brained scheme. Tanya, perhaps. It's right up her street. But not you!"

I don't know if he saw the tears come into my eyes. But if he did, I counteracted them by saying stubbornly, "Well, I do. I approve. We've given our promise ... Mother's signed the agreement. And that's that!"

I saw Robbie's full lips tighten. He stared at me baffled, as if I were a vandal. A cold silence like a drench of spray lapped over us. The day's outing, only an hour or so old, disintegrated.

I felt my heart thudding with disappointment. And once more the thought hammered in my mind. My first real date with Robbie, and we were quarrelling. And as with Tanya, it was the film unit that had caused it.

Again.

CHAPTER VI

I suppose if it had been anyone else but Robbie, the disagreement would have spoiled the whole day. But nothing can really sour the sweetness of Robbie's temperament. I don't know how long the cold estranged silence continued. What I do know is that it was sufficiently long for Robbie to lose his concentration on Sea Nymph.

For suddenly a wave, not an estuary wave this time, but a real sea roller, caught us beam on. The wheel spun, and we were drenched, this time in a real cold salty spray.

Robbie let out a quick shout, which being Robbie, toppled as suddenly into laughter. "Heavens! I didn't see we'd passed the harbour bar." He caught hold of the wheel, and turned Sea Nymph neatly back, nosing into the green waves. And as suddenly he flung out his free arm and caught me to him.

When he kissed me this time, it was very gently and both our faces were as wet and salty as if we'd been crying. It gave that kiss, to me anyway, a special significance of real reconciliation.

"There!" said Robbie at last. "I'm sorry. It is nothing to do with me. It is your concern. Or rather your mother's. But I love Holywell Grange too. I... oh, well, never mind what I was going to say about that. Let's just forget all about it. Let's enjoy ourselves. Mrs. Jackson's packed a very special picnic. She's got a soft spot for you. First of all, I'm going to turn up coast a bit and find a little inlet I know where we can anchor."

He kissed the top of my head, and then used both his hands to turn Sea Nymph's wheel hard to port. We bumped about a bit as we chugged across the waves at the foot of the chalk cliffs.

"Mind you," Robbie said, concentrating on the sea and not, apparently, on my face, "you can deny it as much as you want. But I know you hate the scheme as much as I do. More, in fact. But you being you are just too nice to say so."

Though he wasn't looking at me, he seemed to see me open my mouth to protest, because he held up his hand, and said, "No! Positively no! I won't let you deny it! I'm having the last word on the subject today. And that is that! If you say one word I'll let the wheel go and come and kiss you. And those cliffs are mighty near!"

So I just had to let it go at that. And at that, there was some queer comfort in it, as I think Robbie had meant there to be. He didn't speak again for a while. He just hummed under his breath, while smooth green hillocks of water on one side and white cliffs on the other fled past us. Seagulls flew out of crevices in the rock and soared high into the blue. The air was still, and on the other side of the horizon, high white cumulus build-ups had grown like matching white cliffs.

Then, ahead of us, the cliffs became lower and seemed to back away. "Actually," Robbie said, pointing to it, "that's caused by a cliff fall. But it makes a sheltered bay. And it's got shallow water to anchor in."

He throttled back Sea Nymph's engine to a soft lazy putter. Then he showed me where the anchor was stowed, and I helped him slide it over the side. When he cut off the engine, we seemed enfolded in a small cell of quiet.

On either side of us, the white cliffs acted like the shelter of a huge armchair. And within the sheltering arms, the smooth green rollers diminished to lakeshore size. They flopped lazily against the shingle of the sun-drenched beach, with soft hissing sighs, rocking us gently up and down as they came and went. Although it was Saturday, the inlet was deserted.

"It's virtually impossible to get down to it from the landward side. And not many people know about it, anyway," Robbie explained.

We toyed with the idea of wading ashore, but we finally settled for picnicking on board. Robbie pulled down a red-and white-striped deck awning, and I lay under that while he produced Mrs. Jackson's provisions.

I had never had a meal at High Acres, but I'd heard in the village that Robbie's housekeeper was an excellent cook. And certainly that day she had excelled herself. There were shrimp patties and asparagus rolls, chicken in aspic, stuffed tomatoes, and a tossed salad, crisp from the ship's tiny refrigerator.

With these she had packed sticks of morning-baked bread, and their own freshly churned butter. And all this was followed with fluted strawberry tartlets, topped off with whipped cream.

"It's as well we're not expected to swim after all that," I said, pouring the coffee. "I don't think I've ever had such a lovely picnic."

"Well, there'll be lots more, I promise you. We'll need these outings all the more, you and me, when the film unit comes. We birds of a feather," he grinned, "must fly away together."

And that was all he mentioned about the film unit again that day. Without having to put it into words, we had come to an agreement. The less said about the film unit the better.

So we lazed on deck, chatting about safe subjects like my class at school, and what the headmaster had said to the Ministry Inspector, and how I hoped that Tim Brocklebank (whose father is the village blacksmith) would get to a Technical School, and how Lady Jayne was a bit nappy these days because she wasn't getting enough exercise. And then we talked about Robbie's shorthorns and the funny remarks Mr. Jackson made. ...

Then Robbie stood up and said, "Damn, the sun's gone in! We can't sit and sunbathe without the sun." He helped me to my feet and scanned the sea. A small smile played around his lips. "I know," he said. "It's just the weather! A slight swell, but no white horses. Let's take Sea Nymph out into deeper water. And you can watch me put her through her paces."

I said I was game, and while he hoisted and stowed the anchor I went down into the tiny cabin and washed the plates and cups and put them away.

Down there you could feel more rocking from the tiny inlet waves. Or maybe it was just that they'd increased in strength with the rising of the tide. I heard Robbie start up Sea Nymph. Before I climbed the three steps back on to deck again we were turning out to sea, to where now the white cumulus towers filled the sky like a medieval citadel.

Once out of the shelter of the cliffs, Sea Nymph bucked like a young filly. Then Robbie had her slicing through the tide, taking each smooth green roller with just an economical dip and rise. Then he accelerated and the great bow wave rose up on either side of us like white wings.

White wings we really seemed to have, skimming over rather than through the water, blinded with wind and sea, and the thud of each wave regular and steady as a heartbeat. After ten minutes of that Robbie put his mouth to my ear and shouted, "We could be over in France in another hour. Are you game?"

In some odd way, I knew it was a little test. Despite the wind and the spray, I was aware that he was watching me.

It was as if, after the business of the film unit, he was giving me another chance to be his sort of girl. All the same, I shook my head and I waved my hand to get him to slow her up.

"Sorry," I said breathlessly, as the engine note lowered and our sea waves subsided, "but I did say we wouldn't be all that late. Mother worries a bit."

"Well, you're a big girl now. You can look after yourself."

"Oh, it's not that, Robbie. She knows I can. She never stops me doing anything. I simply don't like her to be worried. Especially," I added, "as the weather isn't so good."

I said that last sentence before I actually looked around. When I did, I frowned. The sky now was heavily overcast, and those white towers had turned a formidable grey, and flattened themselves into what every Downs dweller knows are the anvil heads of thunderclouds. All around us the now grey rollers had risen in strength, and that ominous sneaky wind that precedes a storm was blowing off the land behind us and whipping a thin spume off their rising tops.

At least, I thought of it as the land behind us, but when I turned, the coast had gone, blotted out by distance and diminishing visibility.

Luckily, Robbie is no fool. I saw him look around as well, and although no frown wrinkled his brow, I noticed a new alertness in his expression.

"Mmm, yes—well, maybe you're right at that!" He gave me one of his broad sweet smiles. "As usual. Five minutes more and I'll turn her around. It's high tide now or thereabouts. It'll turn any minute, then we'll be into tide again, and it'll be that much more fun."

It seemed churlish to grudge him five more minutes, though I kept glancing all the time, first at my watch, which moved so slowly, and then up and behind and in front, at the clouds which gathered so fast.

Now the thump of the waves seemed not like a heartbeat, but a series of heavy body blows. I'm not a nervous person, but I have the countrywoman's healthy respect for wind and weather, and I couldn't help remembering that Robbie was town born and bred, and only a recent sailor. Finally, breathless himself, Robbie said, "All right, let's call it a day." He laughed, as he throttled back the engine. "Or night, should I say?" He squinted up at the black clouds and shrugged.

Now that the engine note was no longer blotting out every other sound, I heard the sea echo with the none-too-distant rumble of thunder. And from the furthest anvil cloud came a quick blue flicker of lightning.

The first heavy splash of rain fell almost immediately, isolated large drops that herald the beginning of a thunder downpour. Then I didn't notice it for a moment because Sea Nymph was away on my side, as Robbie wrenched her round towards home.

He'd been right about one thing, and that was the tide. It had turned all right. The swell was rising and a heavy ebb tide flowing. I could feel it shoving us back as Robbie gave Sea Nymph all the power he dare.

"Don't worry," Robbie said, as the real rain now came down, rattling on the deck and dimpling the troughs of the grey-green waves. "It's just a harvest storm."

"It isn't harvest time."

"Then it's a lambing storm."

"That's ages ago." I had to shout above a crack of thunder. But Robbie just laughed.

"This is one that got left behind."

Then a huge flash of lightning seemed to split the sky ahead of us. Vivid corkscrews of white light touched the sea and our faces, illuminating the waves in their eerie radiance. I felt my own face tense with fright, and I glanced at Robbie. I must admit that the thing I feared then, above anything else, was that I'd see Robbie himself, the townsman, suddenly confronted with the elements, baffled, and therefore afraid.

But nothing seemed to alter Robbie's expression. That slight smile was still there. His face was covered in sea spray and rain, and he lifted one hand just briefly off the wheel to wipe his eyes clear. Feeling me watching him, he said, still in that good-tempered voice of his, "Rosamund, be a dear. There are oilskins stowed under the for'ard bunk. Get them, will you, darling?"

It says rather little for my courage that it was only afterwards I remembered he'd called me darling. And then it seemed more important to find the oilskins in the darkness of the lurching cabin than to register the endearment. I got them as quickly as I could, because down there it was stuffy and sickly.

I'd just got my foot on the first step of the ladder up when the engine note went soft. And for one glorious moment I thought miraculously we'd made the estuary already. I bounded up the next two, and heard Robbie swearing softly under his breath.

"Put that oilskin on, darling! Here, give me the other. Do it fast as you can, sweetie, then take the wheel. Here! No, hold it very steady! You have to wrestle a bit, old thing. Yes, that's it! While I tinker with the engine. She's done her best. But there's a spot of wet got in."

I suppose it was the jolly conversational tone of his voice that made me momentarily blind to danger—an engine failing miles off land in heavy weather, in a little pleasure boat with no radio, and an ebb tide shoving us out to sea and thunder all around. That and the fact that the wheel and I seemed to fight all the way. I hadn't time to don the sou'wester, and the rain drenched my hair, gumming most of it to my face while the wicked wind whipped loose ends like a wet towel against my cheeks. Any energy I had left over I kept for peering ahead for those blessed white cliffs, looming out of the rain mist ahead.

Then the soft faltering engine note gave a short, sharp bark, faltered once more, and then gained strength. Finally it settled on a firm steady note.

"That's the girl," Robbie shouted. "For a moment she had me worried." This time I think it was sweat he wiped from his face. "Here, let me have that now!" He took the wheel from me. "I'm going to give her all she's got. I've got to risk her conking out. Because if we don't make the estuary before nightfall, we may not find it. And I haven't the gas to look indefinitely."

He wrinkled up his face as he said this, in a humorous deprecating way. He might have been talking about booking for the theatre or which way we should go for an afternoon drive. Then he put his arm round my shoulders and gave me a quick squeeze.

About half an hour later, only the night seemed to have advanced. Not us. We were still surrounded by dark grey running waves. I looked at Robbie's face, and meeting my eyes, he said, "You ought to go in the cabin. You're soaked."

But I shook my head. "I'd rather stay up here."

"Just the two of us." He smiled wryly. Then he said, "Don't worry. I'll get you home, I promise you."

And then, after that, I stopped worrying.

It was just about nine-thirty and dusk when I saw a blob of light seemingly floating on the tip of an oncoming wave. Then Robbie saw it too. He let out a yell and hugged me to him.

"Home!" He laughed. "Ten more minutes and we'll be in the lee of the cliffs. You feel the shelter then, my love! Not that our troubles'll be over." He laughed triumphantly. "But we'll live!"

Ahead the squalling rain mist seemed suddenly to solidify. Up loomed the chalk cliffs, with their white froth of breakers. And to port were the little vee of lights on either side of the estuary, and the smooth waters of the river. Even then we had to fight hard to get in against the tide and the swollen outpouring of the Derwent. I remember hearing the church clock of Seahaven, which is high on the headland, chiming as we at last hit the calm of inland water. And it again says little for my courage that my first thought was that we were safe, and how lovely to hear the country sound of chimes instead of the howl of the sea and the crack of thunder. Then I counted the chimes. Eleven. And my relief turned to dismay.

"It's all right," Robbie said. "I'll get you home in another hour."

"Midnight!"

"Sorry, can't make it earlier. The Derwent has a strong current at the best of times. Now it's swollen. And the engine's taken a beating."

I suppose I must have looked horrified, because from then on Robbie kept tinkering with the engine trying to get more out of her. The thunder had died away, and the night air was cold. I leaned over the rail, clutching the oilskins round me against the wind. Suddenly I was glad of this hour to calm down. I watched the black waters running by, knowing that a different person, perhaps two different persons, watched them from the two who had set out in sunlight.

A new dimension had been added to my idea of Robbie. I saw him now as someone foolish perhaps, but devil-may-care courageous, and infinitely lovable. Then suddenly he came behind me, cupped my wet face in his hands, and I wanted him to say only three words.

"I'm sorry," he whispered. But those weren't them. "I was a fool;' he went on. "Thanks for being so decent and for taking it -so well. I can't think of many girls who'd have been so cool. You're an absolute pipper." He dropped his hands and took hold of the wheel with one, and the other he kept round my shoulders.

"You weren't so bad yourself."

"Oh, I don't matter. Or do I?"

"You do."

"Bless you! D'you really mean that? Anyway, I'd have got you home. You know that. Because..." He had to put both hands on the wheel now to turn us round the river bend of Derwent Langley itself. We were in the home stretch. The next curve was the horseshoe bend. Now Sea Nymph seemed to fly against the current.

"Because...?" I prompted.

"Because I ‑" His soft whisper was cut off, drowned by a loud megaphone hail. A huge giant voice echoed like the very manifestation of the thunder across the river and round the bend.

""Sea Nymph ahoy ... ahoy ... is that Sea Nymph?"

Robbie dropped the wheel and put both hands to his lips. "Ye-es!"

Again the monster voice boomed. "And about time!"

Then we rounded the horseshoe bend, and there was our little landing stage dancing with lights. And silhouetted against the lights was a tall figure holding a megaphone to his lips, while other lesser figures stood in the garden. I remember thinking it was like a caricatured version of the arrival of Miss Miranda's lover.

"Where in heaven's name have you been?"

And then I recognised the voice.

"Who are you yelling at?" Robbie shouted back.

"You!"

I heard Robbie's angry mutter as he guided Sea Nymph in and tied her up.

We jumped ashore and Mr. Pemberton and Robbie came face to face.

"I suppose you realise that everyone thought you were adrift at sea? Or drowned?" Mr. Pemberton said. "Mrs. Vaughan has been extremely worried. We had a report that you'd been seen heading out, after the storm cone was hoisted."

"Now just a moment, who do you think you are ..."

The quarrel was just starting when a figure detached itself from the shadows of the garden. I saw her face in the dancing lantern light. The face in the photograph.

Her voice when she spoke was as lovely as her face, and I really can't think of any higher praise than that.

"Nicholas darling," she said, coming forward and laying a hand on his arm, "they've both had a bad fright. Don't start in on them now! Mrs. Vaughan was sensible, and put the coffee on as soon as she heard the engine. Let us be sensible too. All's well now. Let's go inside. We can talk then."