‘And if they were all one member, where were the

body? But now they are many members, but one

body.’ (I Corinthians XII, 19–20)

Introduction

Ever since the early 1980s, concepts such as

‘organizational identity’ and ‘corporate personal-

ity’ have come to the fore in organization studies,

following a surge of interest in symbolic and

ideational dimensions of organizational life (e.g.

Pondy et al., 1983) coupled with a greater atten-

tion to the role of language and metaphor in

representing organizations (Daft and Wiginton,

1979). The ‘organizational identity’ metaphor

in particular has received a huge amount of

academic interest as a device for capturing and

explaining these symbolic and ideational dimen-

sions of organizational life (e.g. Gioia, Schultz

and Corley, 2000a; Whetten and Godfrey, 1998),

but, remarkably enough, its heuristic value as a

metaphor has only marginally been explored. In

a sense, since the watershed article of Albert

and Whetten (1985, p. 293) raised the issue of

whether we can metaphorically project the idea

of an ‘identity’ upon organizations to describe

and explain their dynamics, the field of organiza-

tion studies has moved on, largely ignoring the

theoretical and methodological issues laid bare

herewith.

In fact, while a significant literature on the con-

cept has evolved in recent years (e.g. Academy of

Management Review, 2000; Albert and Whetten,

1985; Ashforth and Mael, 1989; Dutton and

Dukerich, 1991; Whetten and Godfrey, 1998), this

work concerns ‘organizational identity’ as a

metaphor only indirectly, if at all. Yet, researchers

who have acknowledged the concept’s precepts as

a metaphor have only done so in passing, refer-

ring to the ‘extensions’ from individual to organ-

izational ‘identities’ (Czarniawska-Joerges, 1994;

Gioia, Schultz and Corley, 2000b) that serve as a

means of knowledge generation. None have yet

offered a comprehensive account of the mech-

anics and validity of the ‘organizational identity’

concept as a metaphor for the subject that it

supposedly illuminates – one that starts with

developing an understanding of the role and use

of metaphor in organization studies and subse-

quently evaluates the use and heuristic value of

the ‘organizational identity’ concept.

The present article therefore reviews the use

of metaphor in organization theory with the

British Journal of Management, Vol. 13, 259–268 (2002)

© 2002 British Academy of Management

On the ‘Organizational Identity’

Metaphor

1

J. P. Cornelissen

Amsterdam School of Communications Research (ASCOR), University of Amsterdam,

Kloveniersburgwal 48, 1012 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands

This article reviews and evaluates the heuristic status of ‘organizational identity’ as

a metaphor for the generation of knowledge about the subject that it supposedly

illuminates. This is done by drawing out the general uses and utility of metaphors

within organizational theory and research, on the basis of which the article assesses the

‘organizational identity’ metaphor with the objective of providing insight into whether

this particular metaphor is warranted and has any heuristic value for our understanding

of organizational life.

1

Thanks are given to Scott Taylor, Iina Hellsten and

the editor of BJM for their valuable comments upon an

earlier version of this paper.

06_Cornel 26/11/02 1:11 pm Page 259

specific purpose of evaluating and establishing

the validity of the ‘organizational identity’ meta-

phor. The issue in question is the place of

metaphors such as ‘organizational identity’ in

theory building, and their significance in aiding

our understanding of the field of organization

studies. The intent of the exercise is to develop

a solid conceptual foundation that eliminates

observed problems that have arisen as a result of

undue attention to the metaphorical qualities

of ‘organizational identity’, and from which

further research upon the subject addressed by

the metaphor can be cultivated and guided.

The next section starts by outlining the general

use of metaphor in theory development within

the domain of organization studies, followed by

a discussion of a method for controlling and

evaluating its uses.

Metaphor in organization studies

Tied in with different schools of thought upon

metaphor and discourse within the philosophy

of language and linguistics (e.g. Davidson, 1978;

Lakoff and Johnson, 1980; Ortony, 1979a), the

initial debates upon the role and use of metaphors

in organization studies are equally clustered around

two poles. Departing from distinct ideological

positions – that is, ‘constructivism’ versus ‘non-

constructivism’ or ‘realism’ (see Ortony, 1979a) –

writers within organization studies initially adopted

distinct views of the underlying epistemology on

which the explanatory account of metaphor is

constructed leading to debates on the workings of

metaphor for (re)presenting organizational life

(see Morgan, 1980, 1983; Pinder and Bourgeois,

1982). A later article by Tsoukas (1991), however,

attempted to remedy the differences between

these earlier debates by outlining the single cog-

nitive process of metaphoric understanding that

underlies both. The method of metaphor for

organization theory that Tsoukas (1991) subse-

quently developed hinges upon a seemingly simple,

yet profound, idea of the working of metaphors

within scientific endeavours (see Bono, 1990;

Boyd, 1979): when generating a metaphor, similar

attributes of phenomena, subjects or domains are

identified to form an analogy (the implied simile),

while dissimilar attributes of the referents are

identified to produce semantic anomaly (see

MacCormac, 1985). As such, in working through

a relational comparison of not normally associated

referents, it can be asserted that a metaphor thus

always implies a statement of similarity – ‘every

metaphor may be said to mediate an analogy

or structural correspondence’ (Black, 1977/1993,

p. 31) – as well as a suggestive hypothesis of com-

parison between disparate concepts (see Morgan,

1980, 1983).

The latter suggestive conjecture that a meta-

phor implies involves its particular use as a ‘useful

heuristic device. That is, the imagery contained in

the metaphor must assist the theorist in deriving

specific propositions and/or hypotheses about the

phenomenon being studied’ (Bacharach, 1989,

p. 497). In effect, as Stepan (1986, p. 268) suggests,

metaphor in science works through evoking

associations among ‘specially constructed systems

of implications’ and its suitability for scientific

purposes comes exactly from this ‘ability to be

suggestive of new sets of implications, new hypoth-

eses, and therefore new observations’.

The use of metaphor in organization studies, as

in other scientific fields, thus involves a strategy

for the accommodation of language with the pur-

pose of eventually revealing as yet undiscovered

features and dynamics of the world (cf. Bono,

1990; Boyd, 1979). This heuristic value of a meta-

phor, once it is granted through a sufficient degree

of similarity between the primary and secondary

concepts, is then primarily established by the

suggestive hypothesis of comparison between

disparate concepts, which in turn gives rise to

assertions and propositions concerning the identity

and dynamics of a particular organizational phe-

nomenon that are subject to further examination

and scrutiny (see also Morgan, 1980, 1983;

Tsoukas, 1991). Importantly, once these suggested

propositions and assertions have been probed and

validated through further research, a metaphor

qua metaphor might then be dispensed with as

though it were ‘a ladder to be kicked away once

the new theoretical plateau has been reached’

(Brown, 1976, p. 174). In other words, once the

suggested hypotheses and assertions have found

some validation through empirical examination, a

metaphor might evolve into a specific, declarative

model of the identity and dynamics of a particular

phenomenon – ‘every metaphor is the tip of a

submerged model’ (Black, 1977/1993, p. 30) –

reduced to and based upon a revealed structural

similarity between the source model and the

targeted subject (Indurkhya, 1992, p. 34).

260

J. P. Cornelissen

06_Cornel 26/11/02 1:11 pm Page 260

The crucial transformation here, as Weick

(1989) and Tsoukas (1991) have already pointed

out, hinges upon the difference between ‘live’ and

‘dead’ metaphors and their role and status within

theory construction and verification. Metaphors

that are entertained in a ‘live’ manner are

characterized by a metaphoric transfer and are

therefore suggestive, and not (yet) declarative, of

a particular organizational phenomenon. Naturally,

as suggested, in the process of theory construction

to verification and testing, metaphorical concepts

are gradually ‘dying’ (Hunt and Menon, 1995;

Pinder and Bourgeois, 1982; Tsoukas, 1991). That

is, in the early phases of conceptual development,

a ‘live’ metaphor acts as a precursor to theory:

as a provisional way of organizing and seeing

organizational reality that lays out the lines for

subsequent theory and observation. At this stage,

metaphor does not refer directly to observables

and empirical organizational entities, but to

hypothetical, provisionally agreed upon entities

(see Sandelands and Drazin, 1989). A trans-

formation into a ‘dead’ metaphor then surmounts

with support for the hypothesis suggested by

the initial metaphoric transfer and a further spe-

cification of the subject denoted by the metaphor.

As a result, ‘dead’ metaphors can be defined as

those concepts that have become so familiar and

so habitual in our theoretical vocabulary that

not only have we ceased to be aware of their

metaphorical precepts, but also have we stopped

to ascribe such qualities to them. Instead, such

concepts have now evolved into, and come to be

treated as established, literal terms involving a

denotation and reference to an empirical organ-

izational object that is relatively precise and

exact, and also lends itself to theory verification

or testing (Tsoukas, 1991).

The foregoing introduction to the use of meta-

phor in organization studies, and the workings of

metaphoric transfer as a vehicle for knowledge

generation in particular, have raised a number of

concerns for the conscious, directed and informed

use of metaphors in organizational theory and

research. As mentioned, pertinent to any use of

metaphor in organization studies is the recog-

nition that, when juxtaposed to a literal description,

a metaphor must go beyond such a description

and be a useful heuristic device (Bacharach, 1989;

Tsoukas, 1991; Weick, 1989). As such, the role of

any particular metaphor in organization studies

is thus not trivial, lest unconditional: the infusion

of metaphor into organization theory needs to

provide for fresh, and previously non-existent,

insights into the reality of organizational life, by

offering a plausible hypothesis of the dynamics

and identity of a particular organizational phe-

nomenon. It follows that, first, metaphors need to

be consciously ‘chosen for their aptness in captur-

ing an as yet unspecifiable range of interconnec-

tions among potential features of the empirical

world which observations lead us to believe exist’

(Bono, 1990, p. 65), and, second, that their use

and heuristic value needs to be explicated and

assessed as ‘an essential part of the task of sci-

entific inquiry’ (Boyd, 1979, p. 362). Unfortunately,

however, there has been little in the way of

methods or prescriptions of metaphor use to aid

organizational theorists in being ‘more deliberate

in the formation of these images and more respect-

ful of representations and efforts to improve

them’ (Weick, 1989, p. 529). As a result, we

observe, many metaphors within the domain

of organization studies, such as ‘organizational

identity’, have not (yet) been sufficiently ex-

plicated or assessed upon their heuristic value for

aiding our understanding of the world of organ-

izations. The present article therefore outlines

a general method of metaphor use in theory

construction within the domain of organization

studies, based upon the process of metaphoric

transfer and understanding outlined above. Aside

from its general implications for organization

theory, this method of metaphor use is of par-

ticular importance for our present concern, which

is to evaluate the aptness and heuristic value of

the ‘organizational identity’ metaphor for organ-

ization theory and research.

A method of metaphor use

To establish and guide a process of systematic

uses of metaphor in theory construction, the

article furthers prior work of Tsoukas (1991) and

Hunt and Menon (1995) amongst others. The

application of this method thus specifically con-

cerns ‘live’ metaphors, as these figure in theory

construction (Tsoukas, 1991), and as their use

needs to be harnessed, directed and controlled

in an explicit and more self-conscious manner in

order to avoid predictive and explanatory impotence

(Weick, 1989). The central thrust of this article

is thus not whether metaphor exists and should

On the ‘Organizational Identity’ Metaphor

261

06_Cornel 26/11/02 1:11 pm Page 261

be used in theory construction, but rather how

metaphorical language can be used in such a way

as to contribute to our mapping and understand-

ing of real mechanisms and identities of organ-

izational phenomena. It follows from this that

metaphors have to go beyond being merely

literary illustrations in order to use metaphorical

thinking in such a way as to eventually reveal

generic properties (e.g. Bono, 1990; Boyd, 1979;

Hesse, 1995; Montuschi, 1995). The matter here is

one of transcending the mere illustrative-cum-

rhetoric level (at which acceptance of a metaphor

is a matter of uncritical intuition and unexamined

prejudice), in order to yield knowledge, which can

be rationally assessed and accepted.

The method presented in this article dwells

upon Schön’s (1965) procedure of displacement

where a familiar concept is ‘carried over as a

projective model for a new situation’ (Schön,

1965, p. 49). As Schön (1965) and Montuschi

(1995) outline, this process of displacement, which

is at the heart of metaphoric transfer, can be

described according to a scheme articulated in

four different stages: transposition, interpretation,

correction and spelling out. In the first trans-

position stage, a concept of a source domain is

projected upon a new target situation by ‘estab-

lishing a relation of comparability between old

and new contexts’ (Montuschi, 1995, p. 317). In

the case of a metaphor, this comparability houses

in a first ‘declarative assertion of existential

equivalence’ (Hunt and Menon, 1995, p. 82)

where similar attributes of phenomena, subjects

or domains are identified to form an analogy

between the primary and secondary subject. This

is not to say that metaphor is equivalent to simile;

nonetheless, it is true that the existence of such

a similarity is presupposed by the metaphor.

An analogy or simile simply exists as a necessary,

though not sufficient, condition for the existence

of a metaphor (e.g. Black, 1962, 1977/1993;

MacCormac, 1985; Ortony, 1979b; Tsoukas, 1991,

1993). The second stage of interpretation then

moves beyond the stated and explicated common-

places of the primary and secondary concepts

(through transposition), and suggests the pro-

jection and assignment of further implications

from the source domain to the target domain

as potentially descriptive and explanatory of the

reality and dynamics of the subject in case. As such,

once a metaphor is thus granted through a suffi-

cient degree of similarity between its implications

and the subject under investigation, the use of

it in primarily investigative or theoretical spirit

offers not a declaration but a further hypothesis of

comparison: that there are important predicates

in the relevant context for the ‘filling in’ or

specification of the metaphor – that there are,

in other words, further significant theoretical

connections to be forged between the domains

involved. The possible resistance that then might

result from transferring and matching these

further implications to the primary subject in

question (often requiring a stretching or shifting

of meaning) is called correction. Correction thus

also involves a first determination of whether

these additional features, and thus the metaphor,

are apt and fitting to the subject under con-

sideration, in turn giving rise to suggestive

assertions and hypotheses that are subject to

further critical examination. Finally, when, after

repeated testing of these further assertions and

hypotheses, a ‘concept shows itself to be perfectly

“adapted” to the new context’ and can be said to

have been ‘spelled out’ (Montuschi, 1995, p. 317),

the heuristic value of the metaphor in capturing

the reality and dynamics of organizational phe-

nomena has become evident. Alternatively, when

a metaphor fails to meet the criteria implied in

this four-stage process – i.e. a sufficient degree

of similarity in transposition, and a suggestive and

subsequently validated hypothesis of comparison

through the interpretation, correction and spelling-

out stages – it has little if any heuristic value (and

should thus be replaced by an alternative concept

or metaphor in consideration of the subject under

investigation):

‘The old theory, or a familiar concept, might func-

tion as sets of condensed expectations projected

onto a new situation. The aim is that of ‘naming’

aspects of the new situation, for which we do not

have a pre-existing terminology. The fulfillment

of expectations is the result of a step-by-step

appraisal of how appropriate, and applicable,

the old context is to a new puzzling situation.’

(Montuschi, 1995, p. 320)

The above four-stage process of metaphor use

provides for a systematic and step-wise method

for controlling, as well as explicating and evaluating,

the use of metaphors in organization studies. The

next section illustrates the use of this method

by dissecting and evaluating the ‘organizational

identity’ metaphor.

262

J. P. Cornelissen

06_Cornel 26/11/02 1:11 pm Page 262

Explicating and evaluating the

organizational identity metaphor

Against the background of the method of meta-

phor in organization theory presented, to call

organizations and organized sets of behaviour an

‘organizational identity’ is to evoke the normal

identity-system of implications (see Cassam, 1999;

Edwards and Potter, 1992; Furnham and Heaven,

1999; Goffman, 1959; Mackenzie, 1978; Popper

and Eccles, 1977) to be transferred to the group

and behaviour in question. The implications in

question thus shape our notion of the subject, i.e.

the collective beliefs and actions of an organized

group, while themselves subject to meaning change

in the process of application. In the case of the

‘organizational identity’ metaphor, the implications

brought into the comparison are derived from

social psychology engaged with the study of an

individual’s identity. Juxtaposed to the concept of

self sui generis, identity is generally seen within

social psychology to focus on the meanings com-

prising the self as an object, to give structure and

content to the self-concept, and to anchor the self

to social systems (e.g. Blumer, 1969; Cassam,

1999; Edwards and Potter, 1992; Furnham and

Heaven, 1999; Gecas, 1982; Goffman, 1959).

Correlated with such different ontological stances

(e.g. interactionism and behaviourism versus

mentalistic accounts) and conceptualizations (e.g.

social identity theory, psychodynamics, post-

modernism, symbolic interactionism) of identity

in social psychology (e.g. House, 1977), there has

also been a degree of ubiquity and variance in

the implications that have been drawn into the

comparison (Pratt and Foreman, 2000b). Table 1

presents, based upon a review of the ‘organizational

identity’ literature, the salient implications of

identity that have repeatedly been projected –

through the metaphor of ‘organizational identity’

– upon organizations.

The implications drawn into the comparison, as

mentioned in Table 1, have all been considered, to

a greater or lesser extent, suggestive of the sub-

ject of ‘organization’ under consideration. The

result of such transfers, then, is new implicative

complexes that suggest original ways of looking at

organization, namely in terms of ‘organization as

identity’ (and that, as mentioned, should normally

be followed by a specification of hypotheses

and assertions that are subject to further critical

examination). For example, the transfer of the

implications of ‘spatial and temporal continuity’

and the ‘unique (individual) character’ suggestively

turns organizations into unique, coherent and

stable sets of activities, values and people (e.g.

Albert and Whetten, 1985; Van Rekom, 1997).

However, returning to the method of metaphor

outlined above, before we can start to consider

the possible hypotheses of comparison suggested

by the ‘organizational identity’ metaphor within

the ‘interpretation’ and ‘correction’ stages, we

first need to consider the necessary element of

similarity between the primary and secondary

concepts (drawn together within the metaphor)

in the ‘transposition’ stage. In this first stage, as

On the ‘Organizational Identity’ Metaphor

263

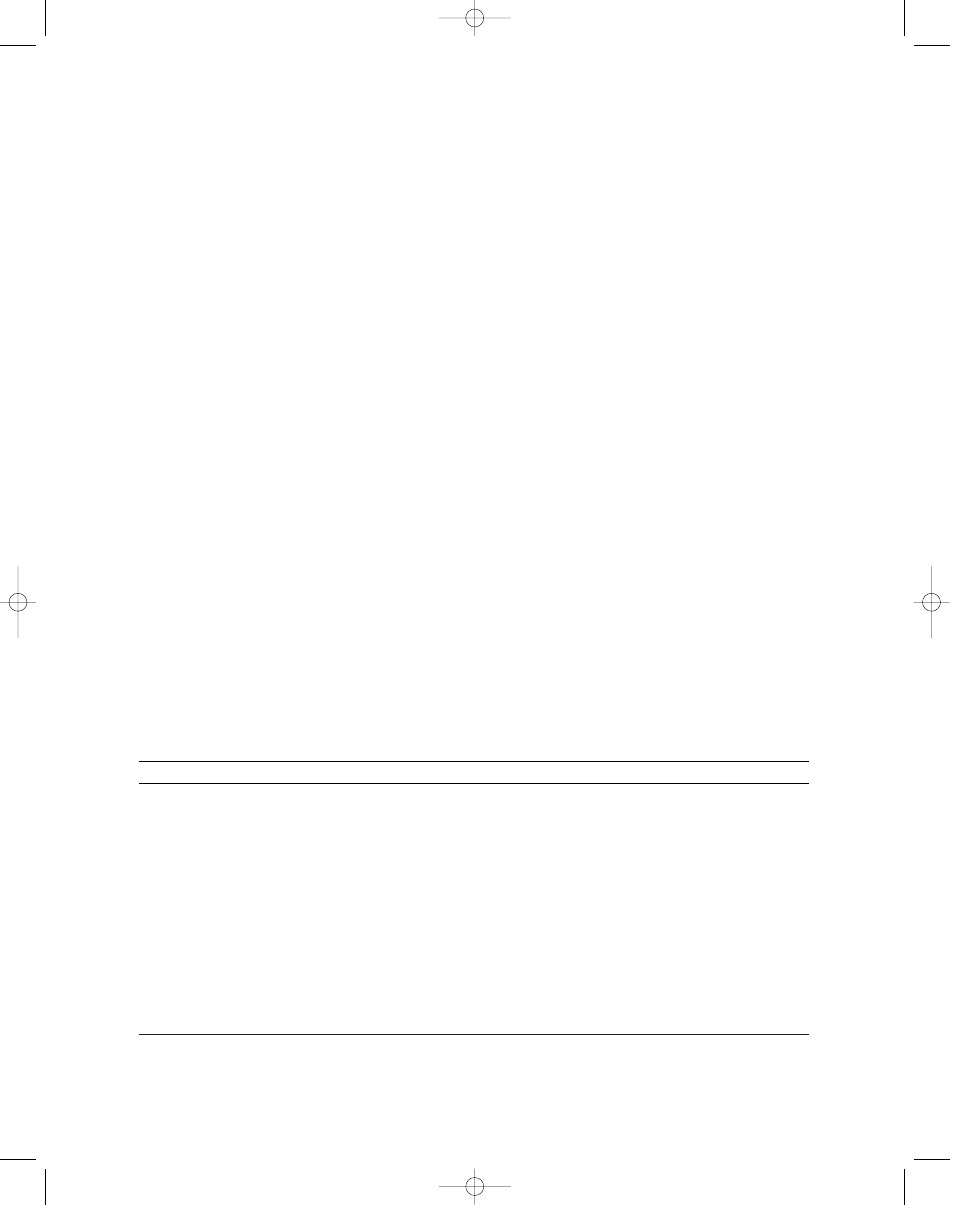

Table 1. The comparison of implication complexes in the ‘organizational identity’ metaphor

Primary subject

Secondary subject

Suggested heuristic

Selected references

ORGANIZATION IS

IDENTITY

←

Spatial and temporal

Organization as an ordered,

Christensen and Cheney (1994),

continuity in physical

unified and relatively

Albert and Whetten (1985)

features/behaviour

permanent role-system

←

Unique and distinctive

Unique characteristics and

Larçon and Reitter (1979),

(individual) character traits

features giving company

Albert and Whetten (1985)

specificity, stability, and

coherence

←

Coherence between

Predictable and coherent

Czarniawska-Joerges (1994),

individual’s experience/thought

beliefs and actions of

Gioia, Schultz and Corley

and action

organized groups

(2000a)

←

Claimed central character

Classifying/representing and

Albert and Whetten (1985),

distinguishing the organization

Albert (1998)

←

. . .

|

-Selfhood

MacKenzie (1978)

|

-. . .

Note: a distinction is made between mappable and non-mappable features, symbolised by an arrow (

←

) and a blocked line (

|

-)

respectively (three dots indicate that none of the categories is exhaustive).

06_Cornel 26/11/02 1:11 pm Page 263

mentioned, the onus lies on identifying a suffi-

cient degree of similarity between the primary

and secondary concepts that would warrant the

metaphor’s further use (through the following

phases) as a heuristic device in theory construction.

The implied simile within each metaphor (based

upon a drawing together of implications grounded

in perceived analogies of structure between two

subjects belonging to different domains) there-

fore needs to be rendered explicit – by way of

paraphrasing or converting the metaphor into a

statement of similarity (Scheffler, 1979, p. 82) –

and becomes then the proper subject for a first

determination of the appropriateness of the

metaphor in case (Pinder and Bourgeois, 1982).

Metaphors that survive such critical examination

in the transposition stage can then progress to the

interpretation and correction stages to consider

their heuristic insights into the subjects to which

they refer (based upon analysis and research pro-

voked by their further hypotheses of comparison).

When considering the ‘organizational identity’

metaphor in detail, however, it appears that

because of the little if any degree of similarity

between the primary and secondary concepts,

there is no existential warrant or ground for its

use. While, interestingly, theorists and researchers

have rushed into the interpretation (as indicated

in Table 1 by the ease with which a whole range of

suggestive comparisons have been made based

upon further salient attributes and predicates from

the secondary identity concept that supposedly

can be projected upon the target domain of organ-

ization), correction and even spelling out

2

stages,

the metaphor’s use cannot be granted in consid-

eration of the little if any degree of isomorphic

similarity between attributes of ‘organization’

and ‘identity’. Mackenzie (1978) elucidates this

observation by pointing out that it is logically

impossible to equate a collective (i.e. organization)

with an individual-level construct (i.e. identity)

and therefore to postulate a ‘collective identity’.

Undergirding this position, MacKenzie (1978)

argues that the implication of ‘selfhood’ or the

‘claimed central character’ within the psycho-

logical construct of ‘identity’, for instance, proves

impossible to transfer to a collective, brought

about by the problem of how to speak of a

singular identity in a collective, a collective self or

a singularity of collective action.

3

Any attempt

at surpassing this logical impasse then amounts

to reification of ‘organizational identity’ as a

separate entity (e.g. Gioia et al., 2000a, 2000b;

Whetten and Godfrey, 1998) – disconnecting it

from the aggregate of individual characteristics

and actions that constitute organizations, which,

it needs to be recognized, in explaining away

individual agency is not true to the real charac-

teristics and actions of individuals in an organized

group. That is, such reification of ‘organizational

identity’ then suggests that the concept has been

given a ‘metaphysical’ status (Levitt and Nass,

1994) presuming a ‘facticity’ with which this

alleged independent entity confronts individual

actors in such a way as to ignore how collectives

such as organizations are produced and reproduced

through individual actions (see also Czarniawski-

Joerges, 1994).

It follows that the use of the ‘organizational

identity’ metaphor, despite its apparent beguil-

ingly suggestive nature (e.g. Academy of Manage-

ment Review, 2000) as well as its continuing and

widespread use (e.g. Whetten and Godfrey, 1998),

is not granted and should thus be replaced by an

alternative concept or metaphor (e.g. ideology,

264

J. P. Cornelissen

2

Gioia, Schultz and Corley (2000b) recently argued

that the ‘organizational identity’ concept should now

be disconnected in theory and research from individual

identity as the covering or secondary concept, and that

the field should as such progress beyond metaphorical

‘as if’ transfers and comparisons for knowledge gen-

eration towards considering ‘organizational identity’ as

a separate model involving a structural similarity with

the subject of organizations and organizational behav-

iour. This suggestion implies, as is characteristic of the

‘spelling-out’ stage, that whereas initially while enter-

tained as a ‘live’ metaphor organizational behavior and

individual and collective sense-making were essentially

described and explained ‘as if’ or ‘as like’ ‘identities’,

aspects and dimensions of organizations should now

come to be seen ‘as’ identities (see also Whetten and

Godfrey, 1998).

3

Following MacKenzie’s (1978) analysis, the claim here

concerns the existential incompatibility between the

individual identity and collective organization con-

structs, which is something different from saying that it

is reasonable and legitimate for organizations to create

narratives that imply a unified whole or an ‘identity’

(e.g. Cheney, 1991; Martin et al., 1983). The crucial

difference here, as Levitt and Nass (1994, p. 240) have

already outlined, is that although such narratives of

‘identity’ might be construed and issued by organ-

izations, an organization cannot ‘narrate itself into

‘personhood’: ‘organizations that refer to themselves as

entities with the same ontological status or character-

istics as “persons” are a priori employing non sequiturs’.

06_Cornel 26/11/02 1:11 pm Page 264

‘gemeinschaft’, society) that not only provides

for insights into the explanandum targeted by the

‘organizational identity’ metaphor, i.e. the mean-

ing and interlocking of ideational and behavioural

aspects of organizational life, but is also based

upon a degree of ‘existential equivalence’ (Hunt

and Menon, 1995, p. 82) that makes the drawing

of the metaphor possible in the first place.

To illustrate this point, and by implication the

need for a metaphor to meet the necessary criterion

of a sufficient degree of structural similarity (in

the transposition stage) (before entering into

the stages concerning the transfer of further

implications that may be suggestive of the target

domain involved), Table 2 presents an explication

of the ‘relationship marketing’ metaphor. This

‘relationship marketing’ metaphor is, in contrast

to the ‘organizational identity’ metaphor, indeed

grounded in a sufficient degree of similarity

between interpersonal relationships (in the source

domain) and the targeted subject of interactions

and behaviors between selling and buying parties

in commercial settings (as made explicit and

symbolized by an open line in Table 2) (see

Iacobucci and Ostrom, 1996, p. 55). Beyond these

structural analogies or isomorphisms between

the domains of marketing and interpersonal

relationships, warranting the conjoining of im-

plications of both subjects within the ‘relationship

marketing’ metaphor, the interpersonal relation-

ship literature has also brought with it a number

of suggestive implications (symbolized by an

arrow in Table 2) that have generated imaginative

conjectures about marketing practices in many

commercial settings in the post-industrial age

(e.g. Sheth and Parvatiyar, 1995). Through these

conjectures that revolve around the notion of a

‘social structure’ existing between individuals or

parties (within friendships, marriages, families

etc.) that carries beyond the manifest, behavioural

exchanges between them, the metaphor has upon

further analysis effectively started to shed light

upon the types of ‘relationships’ existing in many

commercial settings including industrial or busi-

ness marketing (i.e. business-to-business) (e.g.

Kothandaraman and Wilson, 2000), services

marketing (i.e. service provider-to-client) (e.g.

Iacobucci and Ostrom, 1996), and consumer

marketing (i.e. business/brand-to-consumer)

(e.g. Fournier, 1998).

Discussion

The use of analogies and metaphors to point

out the awareness of resemblances serves ‘the

purposes of science’ (Kaplan, 1964, p. 265), and it

is this recognition that has led to increased

On the ‘Organizational Identity’ Metaphor

265

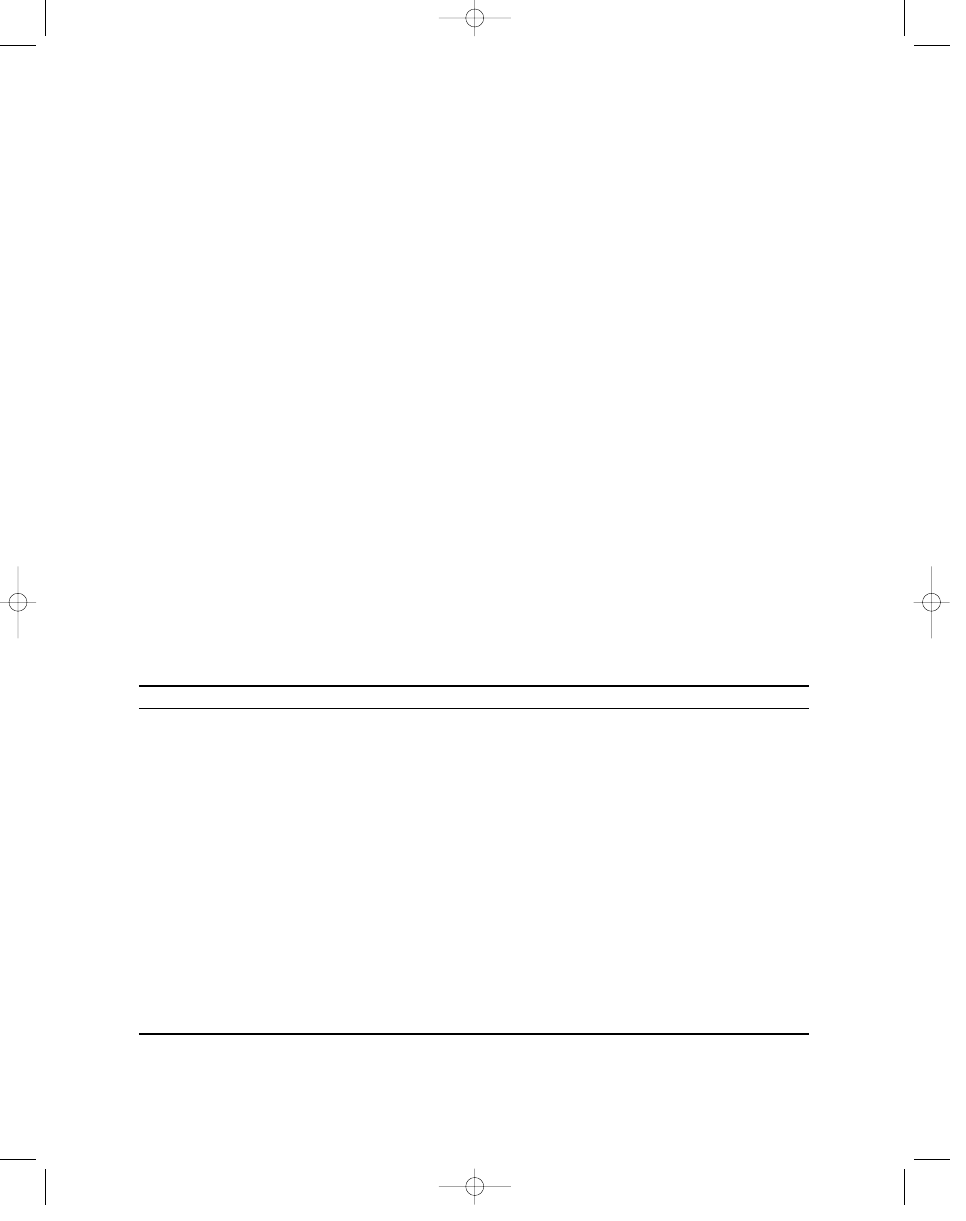

Table 2. The comparison of implication complexes in the ‘relationship marketing’ metaphor

Primary subject

Secondary subject

Suggested heuristic

Selected references

MARKETING IS

RELATIONSHIPS

–interactions between

–interactions between parties

Morgan and Hunt (1994)

parties

–symmetry-asymmetry

–symmetry-asymmetry of roles,

Iacobucci and Ostrom (1996)

of roles, valence,

valence, interdependence,

interdependence, social-

social- or work-related basis

or work-related basis

–. . .

←

social contract

Relationship between parties

Saren and Tzokas (1998)

in commercial settings stretches

beyond the mere interactions

and exchanges between them

←

commitment, trust and

Emotional disposition of

Morgan and Hunt (1994),

emotional bonding

parties towards one another,

Fournier (1998)

inclination to nurture and retain

the commercial relationship

←

cooperation and partnering

Inter-dependence and mutuality

Sheth and Parvatiyar (1995),

between parties in the

Kothandaraman and Wilson

commercial relationship

(2000)

←

. . .

|

-. . .

Note: a distinction is made between pre-existent, mappable and non-mappable features, symbolized by an open line (–), an

arrow (

←

) and a blocked line (

|

-) respectively (three dots indicate that none of the categories is exhaustive).

06_Cornel 26/11/02 1:11 pm Page 265

attention within organization studies to the role

of metaphor in theory development (Hunt and

Menon, 1995; Tsoukas, 1991, 1993; Weick, 1989).

Despite this increased attention, however, there

has been little, if any, prescription to aid theorists

in the use of metaphor when studying and

theorizing about organizations (Weick, 1989).

Therefore, the article has outlined a method of

metaphor in theory construction and has

illustrated its use through an evaluation of the

‘organizational identity’ metaphor. At the heart

of this method lies the perspective that in working

through a relational comparison of not normally

associated referents, a metaphor always implies a

statement of similarity (similar attributes of

phenomena, subjects or domains are identified to

form an analogy), as well as a hypothesis of

comparison (dissimilar attributes of the referents

are identified to produce semantic anomaly)

between disparate concepts. Upon evaluation, the

‘organizational identity’ metaphor has not

passed both hurdles, as there is little if any degree

of isomorphic similarity between the individual-

level construct of identity and the collective-level

construct of organization, making its further use

for theory and research within organization

studies unwarranted.

One obvious suggestion coming out of the

analysis presented is that once paraphrased into a

statement of similarity and comparison, each of

the implications within a metaphor in the organ-

izational field needs to be tested on its own merits

(in account of the subject under consideration)

through further analysis and research, and not

simply assumed to hold because it holds in or is

associated with the metaphor (Pinder and Bourgeois,

1982, p. 643). This continuous assessment of the

selection of salient properties and implications

accompanying a metaphor proves essential, as at

times the beguiling nature of metaphors and the

connotations of the metaphorical term have proven

more important than its actual denotation, and as

metaphors can thus be misleading when they

interrelate entities that not only have no bearing

of similarity with one another, but are also not

suggestive of the subject under consideration.

The notion of a contingency perspective has

emerged at various points in the above analysis.

This viewpoint is theoretically respectable in

the light of the method of metaphor presented,

where metaphors can be evaluated and used in a

reasonably systematic, directed and thoughtful

manner on the basis of the process and criteria

presented (a sufficient degree of isomorphism

premised on the implied simile and the heuristic

value given in by the comparison that it draws

between disparate concepts). In this article, we

have illustrated the use of this method by dissect-

ing and evaluating the ‘organizational identity’

metaphor within organization studies, and, by

doing so, have shown the wider relevance and

utility of this method for evaluating and assessing

new and existing metaphors in organization theory.

Apart from their predictive and explanatory

potency for organization theory and research

within the confines of the academic world, we also

want to raise attention to the political and social

consequences of metaphors when transferred to

and adopted within the managerial arena. As

Stepan (1986) notes, metaphors that have origin-

ally been considered upon their intellectual or

cognitive roles in science, might also carry ‘social

and moral consequences’ (Stepan, 1986, p. 275).

One particular concern in this regard is that

managers, when adopting a metaphor or concept

from organization theory, tend to shape and com-

modify its original scientific content into a simple

set of ideas, thereby compromising the original

and nuanced conceptualization of the metaphor

in case (Astley and Zammuto, 1992). When again

considering the ‘organizational identity’ meta-

phor, managers might reduce this metaphor to

the single extension of ‘a monolithic structure of

feeling and thought’, which, when conceived in

that way, can then be used as a rhetorical and

political device, as a matter of managerial

manipulation, venturing delicately to put people

together in a bundle. In such a managerial trans-

lation of the ‘organizational identity’ metaphor,

an overarching set of values and beliefs is

presumed to exist and to transcend individual

members of the organization, perhaps from such

a managerialist perspective with the aim of giving

them some sense of purpose and directing their

creative energies towards the realization of cor-

porate objectives. Willmott (1993) considers such

an approach as ‘totalitarian’: in such a man-

agerialist account, ‘organizational identity’ offers

a self-disciplining form of employee subjectivity

by asserting that ‘practical autonomy’ is conditional

upon the development of strong ‘collective

identities’ and, to that end, promotes employee

commitment to a monolithic structure of feeling

and thought. Following Willmott’s (1993) analysis,

266

J. P. Cornelissen

06_Cornel 26/11/02 1:11 pm Page 266

rather than offering individuals free choice

of values and identifications, the managerially

induced and overarching ‘organizational identity’

might then come to dictate the source(s) of

identification in an attempt to hamper an

individual’s ‘misdirected’ identification with rival

ends or values and to impute and maintain a sense

of organizational coherence and co-operation

(see also Albert, 1998).

Concluding comments

The article has argued that as organization theorists,

we need to fully appreciate the connection between

observable phenomena and the use of language,

metaphors and theoretical concepts if we are to

avoid the confusion that can result from borrow-

ing or mindlessly applying metaphors. Through-

out our discussion, we have recognized that the

difference between metaphorical language and

literal language is one of degree rather than kind

(Lakoff and Johnson, 1980; Pinder and Bourgeois,

1982), and that it is virtually impossible to avoid

metaphors altogether. Nonetheless, the article has

emphasized that metaphor always implies a state-

ment of similarity and a hypothesis of comparison

between disparate concepts which can be

rendered explicit and evaluated to determine the

appropriateness and heuristic value of the meta-

phor in case. When indeed warranted and judged

insightful to the subject investigated, metaphors

can prove enormously productive of further

theoretical advances and empirical observations

within organization studies (Burrell and Morgan,

1979): by sparking off inquiry and directing

researchers to explore links that would otherwise

remain obscure. However, following in Gouldner’s

(1970, 31ff) footsteps, although we must consider

the fresh insights that each metaphor may bring

us, involving its heuristic potential for theory

development, we must equally be aware that each

metaphor may smuggle hidden or unconscious

assumptions into organizational theory from its

domain of origin, and that it may even carry a

hidden cargo of dubious implications.

References

Academy of Management Review (2000). Special Topic

Forum on Organizational Identity and Identification, 25(1).

Albert, S. (1998). ‘The Definition and Metadefinition of

Identity’. In: D. A. Whetten and P. C. Godfrey (eds), Identity

in Organizations: Building Theory Through Conversations,

pp. 1–13. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Albert, S. and D. A. Whetten (1985). ‘Organizational Identity’.

In: L. L. Cummings and B. M. Shaw (eds), Research in

Organizational Behavior, pp. 263–295. AI Press, Greenwich.

Ashforth, B. and F. Mael (1989). ‘Social identity theory and

the organization’, Academy of Management Review, 14,

pp. 20–39.

Astley, W. G. and R. F. Zammuto (1992). ‘Organization

Science, Managers, and Language Games’, Organization

Science, 3, pp. 443–460.

Bacharach, S. B. (1989). ‘Organizational Theories: Some

Criteria for Evaluation’, Academy of Management Review,

14, pp. 496–515.

Black, M. (1962). Models and Metaphors. Cornell University

Press, Ithaca.

Black, M. (1979/1993). ‘More about Metaphor’. In: A. Ortony

(ed.) (1979/1993), Metaphor and Thought, pp. 19–43.

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and

Method. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Bono, J. J. (1990). ‘Science, Discourse and Literature: The

Role/Rule of Metaphor in Science’. In: S. Peterfreund (ed.),

Literature and Science, pp. 59–89. Northeastern University

Press, Boston, MA.

Boyd, R. (1979). ‘Metaphor and Theory Change’. In

A. Ortony (ed.), Metaphor and Thought, pp. 356–408.

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Brown, R. H. (1976). ‘Social theory as metaphor: On the

logic of discovery for the sciences of conduct’, Theory and

Society, 3, pp. 169–197.

Burrell, G. and G. Morgan (1979). Sociological paradigms

and organizational analysis: Elements of the sociology of

corporate life. Heineman Educational Books, London.

Cassam, Q. (1999). Self and World. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Cheney, G. (1991). Rhetoric in an organizational society:

Managing multiple identities. University of South Carolina

Press, Columbia, SC.

Christensen, L. T. and G. Cheney (1994). ‘Articulating Identity

in an Organizational Age’. In S. A. Deetz (ed.), Communi-

cation Yearbook, pp. 222–235. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Czarniawska-Joerges, B. (1994). ‘Narratives of Individual

and Organizational Identities’. In S. A. Deetz (ed.),

Communication Yearbook, pp. 193–221. Sage, Thousand

Oaks.

Daft, R. L. and J. C. Wiginton (1979). ‘Language and Organ-

ization’, Academy of Management Review, 4, pp. 179–191.

Davidson, D. (1978). ‘What metaphors mean’, Critical Inquiry,

5, pp. 31–48.

Dutton, J. E. and J. M. Dukerich (1991). ‘Keeping an eye

on the mirror: image and identity in organizational

adaptation’, Academy of Management Journal, 34,

pp. 517–554.

Edwards, D. and J. Potter (1992). Discursive Psychology. Sage

Publications, London.

Fournier, S. (1998). ‘Consumers and their brands: Developing

relationship theory in consumer research’, Journal of

Consumer Research, 24, pp. 343–373.

Furnham, A. and P. Heaven (1999). Personality and Social

Behavior. Arnold, London.

On the ‘Organizational Identity’ Metaphor

267

06_Cornel 26/11/02 1:11 pm Page 267

Gecas, V. (1982). ‘The Self-Concept’, Annual Review of

Sociology, 8, pp. 1–33.

Gioia, D. A., M. Schultz and K. G. Corley (2000a).

‘Organizational Identity, Image and Adaptive Instability’,

Academy of Management Review, 25, pp. 63–81.

Gioia, D. A., M. Schultz and K. G. Corley (2000b). ‘Where Do

We Go From Here?’, Academy of Management Review, 25,

pp. 145–147.

Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.

Doubleday, New York.

Gouldner, A. (1970). The Coming Crisis of Western Sociology.

Basic Books, New York.

Hesse, M. (1995). ‘Models, Metaphors and Truth’. In:

Z. Radman (ed.), From a Metaphorical Point of View:

A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Cognitive Content of

Metaphor, pp. 351–372. DeGruyter, Berlin.

House, J. S. (1977). ‘The three faces of social psychology’,

Sociometry, 40, pp. 161–177.

Hunt, S. D. and A. Menon (1995). ‘Metaphors and

Competitive Advantage: Evaluating the Use of Metaphors

in Theories of Competitive Strategy’, Journal of Business

Research, 33, pp. 81–90.

Iacobucci, D. and A. Ostrom (1996). ‘Commercial and

interpersonal relationships: Using the structure of interper-

sonal relationships to understand individual-to-individual,

individual-to-firm, and firm-to-firm relationships in com-

merce’, International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13,

pp. 53–72.

Indurkhya, B. (1992). Metaphor and Cognition. Kluwer

Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

Kaplan, A. (1964). The Conduct of Inquiry. Chandler

Publishing Company, San Francisco.

Kothandaraman, P. and D. T. Wilson (2000). ‘Implementing

relationship strategy’, Industrial Marketing Management,

29, pp. 339–349.

Lakoff, G. and M. Johnson (1980). Metaphors We Live By.

University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Larçon, J. P. and R. Reitter (1979). Structures de pouvoir et

identité de l’enterprise. Nathan, Paris.

Levitt, B. and C. Nass (1994). ‘Organizational Narratives

and the Person/Identity Distinction’. In: S. A. Deetz (ed.).

Communication Yearbook, pp. 236–246. Sage, Thousand

Oaks.

Mackenzie, W. J. M. (1978). Political Identity. Penguin Books,

Harmondsworth.

MacCormac, E. R. (1985). A cognitive theory of metaphor.

MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Martin, J., S. M. Feldman, M. J. Hatch and S. B. Sitkin (1983).

‘The Uniqueness Paradox in Organizational Stories’,

Administrative Science Quarterly, 28, pp. 438–453.

Montuschi, E. (1995). ‘What is Wrong with Talking of

Metaphors in Science?’. In: Z. Radman (ed.), From a

Metaphorical Point of View: A Multidisciplinary Approach

to the Cognitive Content of Metaphor, pp. 309–327.

DeGruyter, Berlin.

Morgan, G. (1980). ‘Paradigms, metaphors and puzzle solving

in organizational theory’, Administrative Science Quarterly,

25, pp. 605–622.

Morgan, G. (1983). ‘More on metaphor: why we cannot

control tropes in administrative science’, Administrative

Science Quarterly, 28, pp. 601–607.

Morgan, R. M. and S. D. Hunt (1994). ‘The commitment-trust

theory of relationship marketing’, Journal of Marketing, 58,

pp. 20–38.

Ortony, A. (ed.) (1979a). Metaphor and Thought. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge.

Ortony, A. (1979b). ‘The Role of Similarity in Similes and

Metaphors’. In A. Ortony (ed.), Metaphor and Thought,

pp. 186–201. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Pinder, C. and V. W. Bourgeois (1982). ‘Controlling Tropes in

Administrative Science’, Administrative Science Quarterly,

27, pp. 641–652.

Pondy, L. R., P. J. Frost, G. Morgan and T. C. Dandridge (1983).

Organizational Symbolism. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT.

Popper, K R. and J. C. Eccles (1977). The Self and its Brain:

An Argument for Interactionism. Springer Verlag, Berlin.

Pratt, M. G. and P. O. Foreman (2000a). ‘Classifying Man-

agerial Responses to Multiple Organizational Identities’,

Academy of Management Review, 25, pp. 18–42.

Pratt, M. G. and P. O. Foreman (2000b). ‘The Beauty of and

Barriers to Organizational Theories of Identity’, Academy

of Management Review, 25, pp. 141–152.

Sandelands, L. and R. Drazin (1989). ‘On the Language of

Organization Theory’, Organization Studies, 10(4),

pp. 457–478.

Saren, M. J. and N. X. Tzokas (1998). ‘Some dangerous axioms

of relationship marketing’, Journal of Strategic Marketing, 6,

pp. 187–196.

Scheffler, I. (1979). Beyond the Letter: A Philosophical Inquiry

into Ambiguity, Vagueness and Metaphor in Language.

Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Schön, D. A. (1965). Displacement of Concepts. Tavistock

Publications, London.

Sheth, J. N. and A. Parvatiyar (1995). ‘The evolution of

relationship marketing’, International Business Review, 4,

pp. 397–418.

Stepan, N. L. (1986). ‘Race and gender: The Role of Analogy

in Science’, Isis, 77, pp. 261–277.

Tsoukas, H. (1991). ‘The Missing Link: A Transformational

View of Metaphors in Organizational Science’, Academy of

Management Review, 16, pp. 566–585.

Tsoukas, H. (1993). ‘Analogical Reasoning and Knowledge

Generation in Organization Theory’, Organization Studies,

14(3), pp. 323–346.

Van Rekom, J. (1997). ‘Deriving an operational measure of

corporate identity’, European Journal of Marketing, 31,

pp. 410–422.

Weick, K. E. (1989). ‘Theory Construction as Disciplined

Imagination’, Academy of Management Review, 14,

pp. 516–531.

Whetten, D. A. and P. C. Godfrey (eds) (1998). Identity in

Organizations: Building Theory Through Conversations.

Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Willmott, H. (1993). ‘Strength is Ignorance; Slavery is

Freedom: Managing Culture in Modern Organizations’,

Journal of Management Studies, 30, pp. 515–552.

268

J. P. Cornelissen

06_Cornel 26/11/02 1:11 pm Page 268

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

09 on the Metaphysical Poets

The Dynamics of Organizational Identity 2002

On the Adaptations of Organisms and the Fitness of Types

organizational identification during a merger determinant of employees expected identification with

Parzuchowski, Purek ON THE DYNAMIC

Enochian Sermon on the Sacraments

GoTell it on the mountain

Interruption of the blood supply of femoral head an experimental study on the pathogenesis of Legg C

CAN on the AVR

Ogden T A new reading on the origins of object relations (2002)

On the Actuarial Gaze From Abu Grahib to 9 11

91 1301 1315 Stahl Eisen Werkstoffblatt (SEW) 220 Supplementary Information on the Most

Pancharatnam A Study on the Computer Aided Acoustic Analysis of an Auditorium (CATT)

Newell, Shanks On the Role of Recognition in Decision Making

BIBLIOGRAPHY I General Works on the Medieval Church

Chambers Kaye On The Prowl 2 Tiger By The Tail

On The Manipulation of Money and Credit

Dispute settlement understanding on the use of BOTO

Fly On The Wings Of Love

więcej podobnych podstron