0

A

RMENIAN

E

GYPTOLOGY

C

ENTRE

F

UNDAMENTAL

R

ESEARCH

P

APER

N

O

.

1

(2009)

-

ELECTRONIC FORMAT ONLY

-

S

EVERAL ANCIENT

E

GYPTIAN NUMERALS ARE COGNATES

OF

« I

NDO

-E

UROPEAN

»

AND

P

ROTO

“I

NDO

-E

UROPEAN

”

EQUIVALENTS

by Christian T. de Vartavan

Y

EREVAN

S

TATE

U

NIVERSITY

–

A

RMENIA

1

SEVERAL ANCIENT

E

GYPTIAN NUMERALS ARE COGNATES OF

« I

NDO

-E

UROPEAN

»

AND

P

ROTO

“I

NDO

-E

UROPEAN

”

EQUIVALENTS

Christian de Vartavan

1

A

BSTRACT

:

The study, using mainly comparative linguistic, establishes that several ancient Egyptian numerals are

cognates of equivalents in several “Indo-European” languages, as well as in Proto “Indo-European”; i.e. that these

numerals, some attested since the First Dynasty, share a common etymology for historical reasons which are yet to

be unravelled and which may have been decisive in the formative process of the ancient Egyptian civilisation. It also

formulates the hypothesis, despite the widely accepted ‘”African-Asiatic” (previous Hamito-Semitic”) identity of

Ancient Egyptian, that there is an “Indo-European”

2

and/or Proto “Indo-European” linguistic stratum in Ancient

Egyptian which will have to be better distinguished in the future.

In linguistic, despite attested false cognates

3

, the “comparative method” is if rules are respected a

particularly solid methodology. It is often used, for cross verification, in conjunction with the method of

“internal reconstruction” which studies the internal development of a single language over time. If these

methods are prone to much interpretation, by those who use it excessively, and have hence led to many

controversies and rectifications

4

, both have nevertheless provided during the past century unequivocal

results, for our understanding of the history and phonology of languages and opened many paths for our

study of their evolution and relations.

Where Ancient Egyptian is concerned, if the comparative methodology is now increasingly used by a

number of Egyptologists, the method of internal reconstruction is still reserved to the linguists among

them, and generally exclusively to professional linguists outside Egyptology. An understandable situation

as internal reconstruction requires knowledge of its linguistic laws, no less to express it according to

linguistic abbreviations

5

which render its results difficult of understanding, when they are not simply

unintelligible even to the most proficient linguists

6

. With the consequence that these results are hence very

often either dismissed by scholars outside of linguistics, or simply ignored. An important point as, where

Egypt is concerned, historical syntheses are made in the end by Egyptologists.

Interested since many years in the vocalisation of Ancient Egyptian, “coincidental” phonological

similarities between words of this language and their equivalents in Latin, English, French and several

other presently used languages drew the author, who first only used them for mnemonic purposes, to

recently enter the field of comparative linguistic so as to attempt to explain these recurring coincidences.

This led him, within little time, to rapidly identify dozens of words – on the regular increase - which in his

opinion and to his utter stupefaction are cognates of word existing in various modern “Indo-European”

languages, many attested since the Pyramid Texts or even the First Dynasty.

The author is fully conscious of the implications of stating that there is at such early date an “Indo-

European” stratum in Ancient Egyptian. This, not only in view of the commonly accepted African-Asiatic

1

Armenian Egyptology Centre, 7th Floor, The Rectorate, 1, Alex Manoogian Street, Yerevan State University, Yerevan 0049,

Armenia, e-mail: egyptology@ysu.am; a-egyptology.atspace.com.

2

The term “Indo-European” is deliberately left in brackets throughout the article in view of its current definition; one which in

view of the leaps currently made by linguistic may be subject to revision in the future.

3

These are comparatively rare but are recorded, such as for example between Latin “habere”, to have, and German “haben”, to

have (See for example the Online Etymology Dictionary (http://www.etymonline.com/). “Cognates” are words which have a

common etymological origin.

4

See for example Diakonoff, I.M., Kogan, L. (1996), Kogan (2002), Satzinger (S.d. 1), Satzinger (S;d. 2). In the latter publication

Satzinger stating, concerning Orel & Stolbova’s (1994) Hamito Semitic Ethymological Dictionary: “It should be mentioned that the Afroasiatic

roots elaborated for the Hamito-Semitic Ethymological Dictionary (HSED) are quite often extremely hypothetical, and the evidence of just one mistake

may make them completely worthless”. This statement, coupled to the many rectifications provided in his study (An Egyptologist’s perusal

of the [HSED] of Orel and Stobolva) not preventing Satzinger to rightly acknowledge HSED as pioneering work.

5

So as to make this text as widely understandable as possible the author has deliberately removed as much as possible in this text

linguistic signs and expressions.

6

See recently for example Bomhard (2008: 1) concerning Dolgoposky’s (2008) work.

2

(previously Hamito-Semitic) identity of the ancient Egyptian language

7

, but also in relation of the

consequences which such conclusion would have on our knowledge of the formative phases of the

ancient Egyptian civilisation. This is why the identity of nearly all the above mentioned words is

deliberately put under silence in this paper and will remain so until such time as some cross verifying

technique allowing to demonstrate their etymology and linguistic affiliations will be found. Such as

perhaps the above method of internal reconstruction; something which will be the object of separate

forthcoming studies.

Nevertheless, once he understood the above and formulated an hypothesis that there may be an “Indo-

European” stratum in Ancient Egyptian, the author looked for a solid mean to first demonstrate it. After

some research he discovered that this is possible with Egyptian numerals – as in view of their sequential

order – they precisely offer an added vertical cross-verifying mean to the horizontal comparative

phonological methodology to which they can be subjected. Main

8

Ancient Egyptian numerals, as they

have reached us, are as follow:

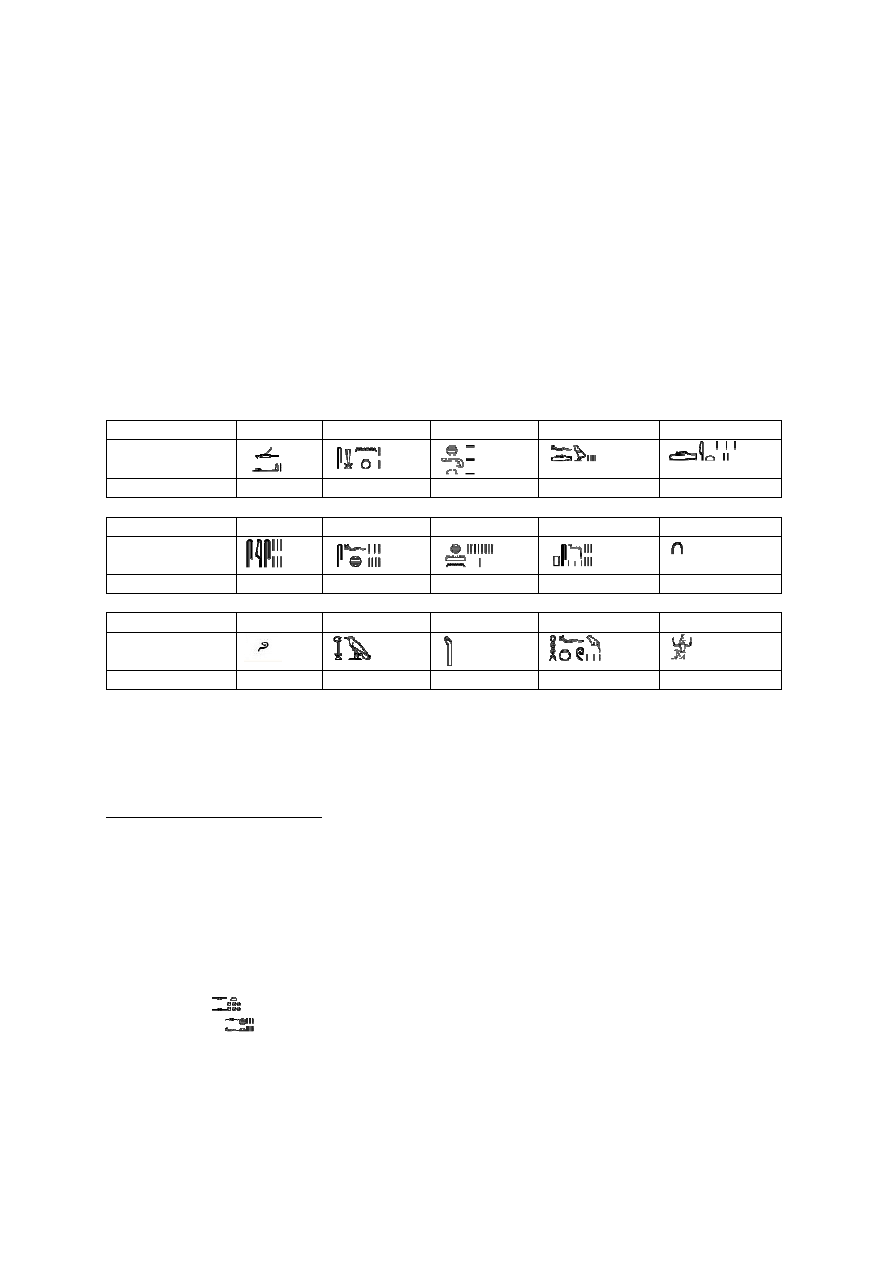

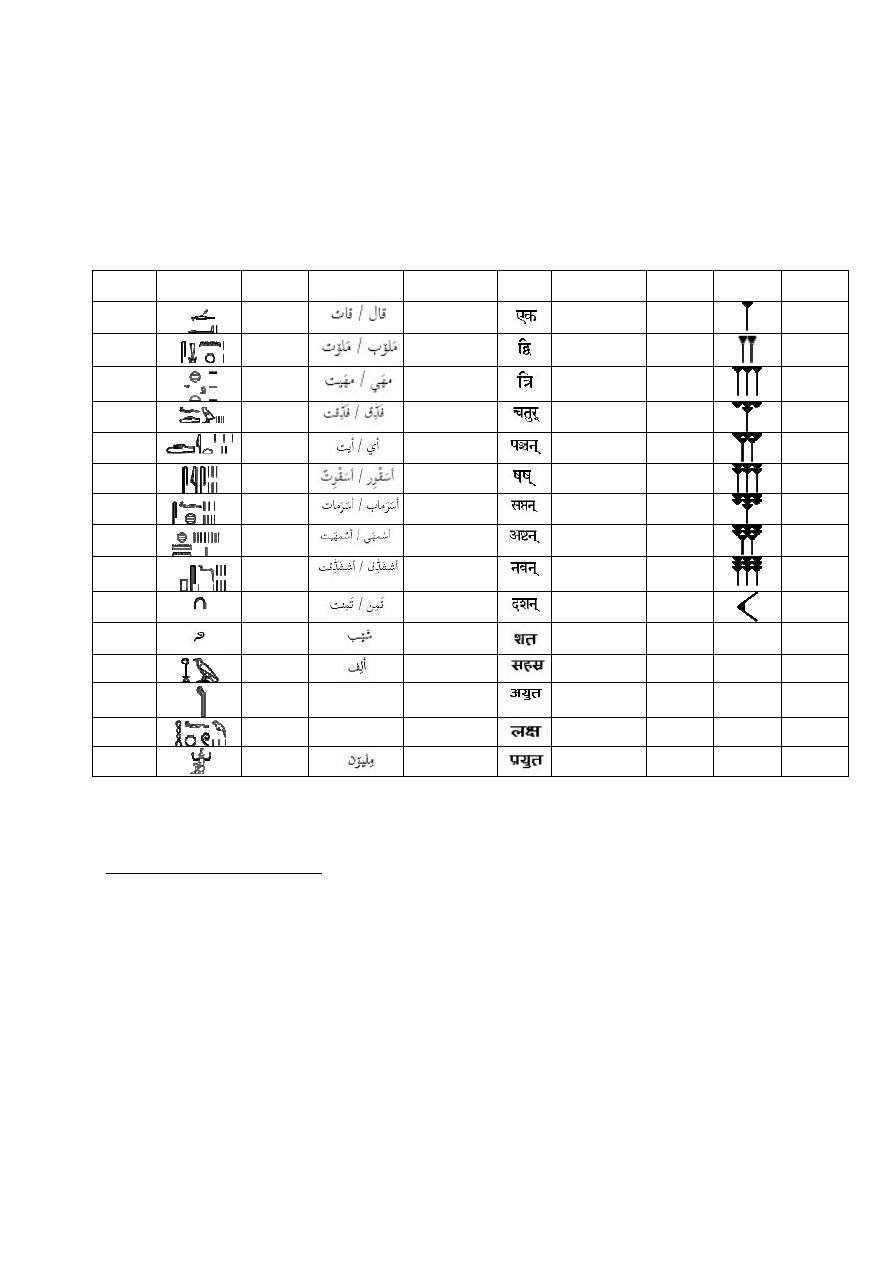

Table 1. Ancient Egyptian numerals (masculine form)

Numeral

1

2

3

4

5

Hieroglyphic

term

9

10

11

12

13

Transliteration

wa

Snwj

xmt

fdw

diw

Numeral

6

7

8

9

10

Hieroglyphic

term

14

15

16

17

18

Transliteration

sjs

sfx

xmn

psD

mD

Numeral

100

1000

10.000

100.000

1.000.000

Hieroglyphic

term

19

20

21

22

23

23

23

23

Transliteration

Snt

xA

Dba

Hfnw

HH

Hence if one uses compares (Table 2, below) Ancient Egyptian and several “Indo-European” (hereafter

often “I.E.”), it becomes unequivocally clear that at least five of the first nine Ancient Egyptian numerals

are phonologically similar, despite shifts of various kinds to their equivalents in these “I. E.” languages; in

particular for the numbers one, four, six and seven. The comparisons given below, including with Proto

7

Allen’s equally recent snapshot of our knowledge of ancient Egyptian language is a good summary of Egyptology’s current view

on the language: “Egyptian belongs to the family of North African and Near Eastern languages known as Afro-Asiatic or Hamito-Semitic. On the

African, or Hamitic side, it is related to Berber and the group of Cushitic and Chadic languages such as Beja [i.e. Bishari] and Hausa, and on the

Asiatic side to Akkadian, Hebrew, Arabic, and other Semitic tongues. Within this spectrum, Egyptian is both central and unique: it has featured

found in North African and Semitic languages but is closely allied to neither group” (Allen, 2008: 189).

8

Terms for numbers between 20 and 90, some not yet fully asserted, are known.

9

Wb 1, 273. 3.

10

Wb 4, 148.6.

11

Wb. 3, 283.8.

12

Wb 1, 582.13.

13

Wb 5, 420.9-12.

14

Wb 4, 40.7. Also

15

Wb 4, 115.15. Also

16

Wb 3, 282.10-11.

17

Wb 1, 558.10

18

Wb 2, 184. 1-2.

19

Wb 4, 497. 9-12; attested since the First Dynasty.

20

Wb 3, 219.3-220.2.

21

Wb 5, 565.13-566.4

22

Wb 3, 74.4-14.

23

Wb 3, 152.14-153.24.

3

Indo-European (hereafter often P.I.E.) since the language has now been reconstructed by linguists

24

, must

however only be considered as examples of shifts resulting in similar phonologies, and not – at least for

the time being - as attempts to prove the ancestry of modern terms with ancient Egyptian words, such as

for example with hbny for “ebony”

25

; a very important point which will shall be discussed again below.

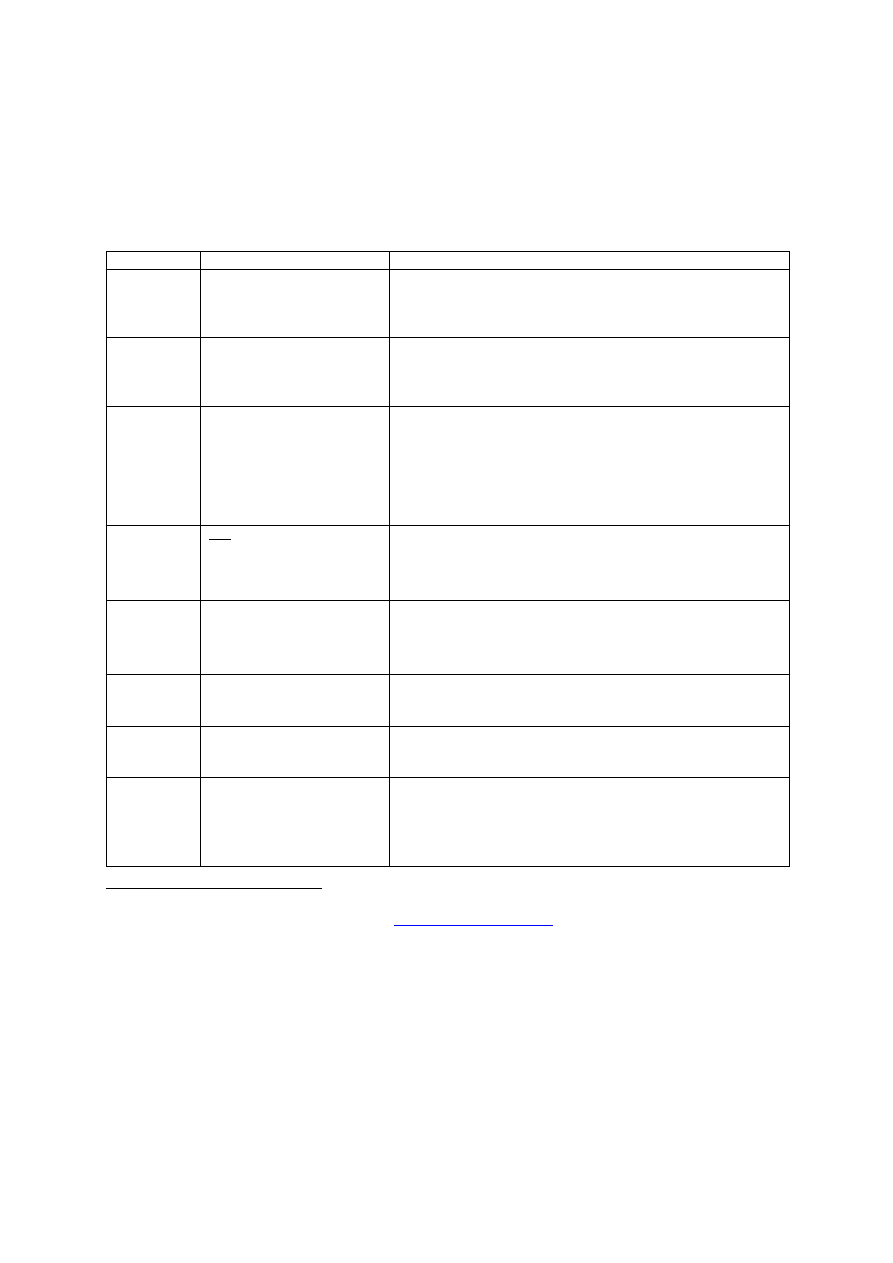

Table 2. Comparenda of the phonology of ancient Egyptian numerals with the phonology of various “Indo-

European” languages, Proto “Indo-European” and other languages

Numeral

Ancient Egyptian

Remarks

One

wa

wa

wa

wa

“Oua

26

”. Phonologically very close to one in English, un

(French), uno (Spanish), from ûnus (ûna, ûnam, Latin),

from the Proto Indo-European *oinos," Old Persian

“aivam, etc…)

27

. Coptic: oua (wa)

Two

Snw

Snw

Snw

Snwiiii

“Shnw[a]i” – Phonologically close to

zwei

in German, or

Proto Germanic *twai, shifting for example to Old High

German

zwene

,

zwo

, from P.I.E. *duwo, from where also

shifted Latin

duo

and

two

in English. Coptic: snau (snaï)

Three

xmt

This phonology the author cannot explain for the time being,

neither from P.I.E. *trei, nor under the light of “Semitic”

languages (see below) despite a possible shift from x to š, as

demonstrated by is later Coptic cognate: 0omnt(“shomnt”).

Moreover, although a pillar “t” is present, the term seems very far

from from PIE *trejes (or. Sanskrit: Trayas. Avestan: thri, Greek:

“treis/tria”, etc…).

Four

fdw

fdw

fdw

fdw

Phonologically very close to “four” in English, itself from

Proto High Germanic *petwor (O. Saxon fiwar, O. Frisian

fiuwer), with a lawful shift from “p” to “f”, and from P.I.E

*qwetwor

28

/*k

etwor-/*ketur-. Coptic: ftoo

ftoo

ftoo

ftoou

u

u

u

(ftwou)

Five

diw

This phonology the author cannot explain either, neither from

P.I.E. *penk

e, nor under the light of “Semitic” languages.

However Coptic +ou (tou) is phonologically close – confirming

the original phonology of this A.E. numeral.

Six

ssssiiiissss

Phonologically identical to “seis” (Spanish), six (pronounce

“seese” – French), sex/sextus (Latin), shifts from P.I.E.

*seks. Coptic: so (so).

Seven

sfx

sfx

sfx

sfx

“sefekho”. Phonologically very close to

seven

(English),

sept

(French), from

septem/septimus

(Latin), etc…, shifts

from P.I.E. *septm. Coptic: sa0f (“shasf”).

Eight

xmn

xmn

xmn

xmn

This would seem different from “eight”,

octo

(Latin), but in

fact comes from P.I.E. *h eḱtou/*h eḱtō or *oḱtō, /*oḱtou,

in French “huit” where a soft “h” is also present; although

also clearly a cognate of Akkadian samānā*, and as already

pointed out by Allen

29

rightly relates it to “Middle

24

See Silher (1995) or Beekes (1995) for example.

25

See gain for example the Online Etymology Dictionary (

http://www.etymonline.com/

) which demonstrates that the remote origin

of the word ebony is now considered as an accepted fact. There are other examples such as the words adobe, oasis, etc…

26

The author is also not using the International Phonetic Alphabet, but simple Latin letters so as to again make the present article

widely understandable; this, besides the fact that where Ancient Egyptian is concerned the exact phonetic of key signs is still a

matter of debate.

27

This does not exclude a link with د (wahed) in Arabic – see the discussion below.

28

Allen (2008 : 194) states that : “Others [cognates] however, are African, such as the adjective nfr « good » (Beja nafir) and the numeral fdw

“four” (Hausa fudu)”. Aside from the fact that in Hausa, four is not – to the knowledge of the author - fudu but hudu, the numerals

from one to ten bear, except perhaps for six which may be like hudu coincidental, seemingly no phonological relation with ancient

Egyptian, hence: One (Daya) , Two (Biyu), Three (Uku), Four (Hudu), Five (Biyar), Six (Shidda), Seven (Bakwai), Eight

(Takwas), Nine (Tara), Ten (Goma). This is further demonstrated by for example “hundred” (Dari) or “thousand” (Dubu).

Moreover, it must be taken in consideration that if ancient Egyptian numerals are to be found in Afro-Arabic languages, within

the sphere of the ancient Egyptian civilisation these numbers may be legation from the ancient Egyptian civilisation; as for

example Beja (Bishari) numerals which have a clear link with ancient Egyptian ones, save the word “million” which the Beja

language recuperated at some point in more recent time.

29

Allen, 2008: 193.

4

Babylonian” x

x

x

x

amana

, Neo-Assyrian *x

x

x

x

y

yy

y

em

em

em

emùn

n

n

n (

(

(

(

see the

discussion below). Coptic: 0moun

0moun

0moun

0moun

(shmoun).

Nine

psD

Very far from P.I.E. e(e)newn, from which derives Sanskrit

“nava”; etc… Linked to Akkadian tiše, and Arabic “”tisa”.

Coptic: 2is

(“psise”)

Ten

mD

mD

mD

mD

Phonologically deceptive as owning the pillar consonant

“d” of

decem

(Latin), from the P.I.E. *dekm/*deḱm̥(t).

Coptic: mht

mht

mht

mht

(meet). It seems interesting to note that in Beja

(Bishari), “ten” is

tamin

.

Had each ancient Egyptian numeral been examined separately, demonstrating them as cognates of “Indo-

European” numerals would have required another method. However since they are numbers, their vertical

sequence combined to their horizontal repetitive phonological similitude confirms them to be cognates of

these “IE” numerals; a conclusion which can be ascertained if the analysis is pushed further.

Now other numerals complete these phonological similarities, starting again and very markingly with the

ancient Egyptian term for “hundred”:

Hundred: Snt

Snt

Snt

Snt

(“shent”) clearly a cognate of French cent (hundred), itself in turn from Latin

centum/centênsimus/centênî/centiêns, in turn shifts from P.I.E. *kmtom, from which also

came Sanskrit: satem, and from which shifted Greek hekaton, later English hundred. Coptic:

0e

(“shé”) or 0ht (“sheet”).

The common etymology between English hundred and French cent becoming only obvious through such

linguistic demonstration, an example in passim of the phonological distance which cognates can take. In

fact the way of writing a “hundred” is what distinguishes to this day – for the better or worse – Indo-

European languages. Languages of the “Centum” group include Latin, French, Spanish, etc… those of the

“Satem” group, usually Indo-Iranian (including Sanskrit), Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Albanian, etc… as also

discussed below.

Proceeding further, it became apparent that the ancient Egyptian term for thousand is also “Indo-

European”, hence:

Thousand:

xA

xA

xA

xA

(kha) is evidently “thousand” as in languages of the “Satem” group where the

“kha/ha” is found, as in Armenian: hazar (

faxae

) or Sanskrit sahasra (

)

, or in the

“Centum” group Greek khil(ias) (χιλ) where the “kh” of Ancient Egyptian is also

found. Coptic:

0o

(sho), with an easily understandable shift from “kh” (x

x

x

x))))

to “sh” (

0)

, as

well as Latin milia which is in fact very close to Greek despite another type of shift.

At his stage one could hastily conclude that if Ancient Egyptian has any link with “Indo-European”

languages, it should be classified - in view of the way ancient Egyptian pronounced “hundred”, i.e. Snt,- in

the “Centum” group. However, the equally close similitude of the word “thousand” with the terms used

in the “I.E.” languages of the Satem group, added to the presence of at least one numeral unequivocally

found in Akkadian – xnmw – betrays a far more complex situation. In fact if one juxtaposes (Table 3,

below) Ancient Egyptian numerals to Akkadian numerals, one notices blatant phonological similarities and

dissimilarities. As if their phonologies had evolved all together in different directions from not only

Semitic but “Indo-European” as well – another very important point; whereas some numbers moreover

appear clearly different. Hence:

5

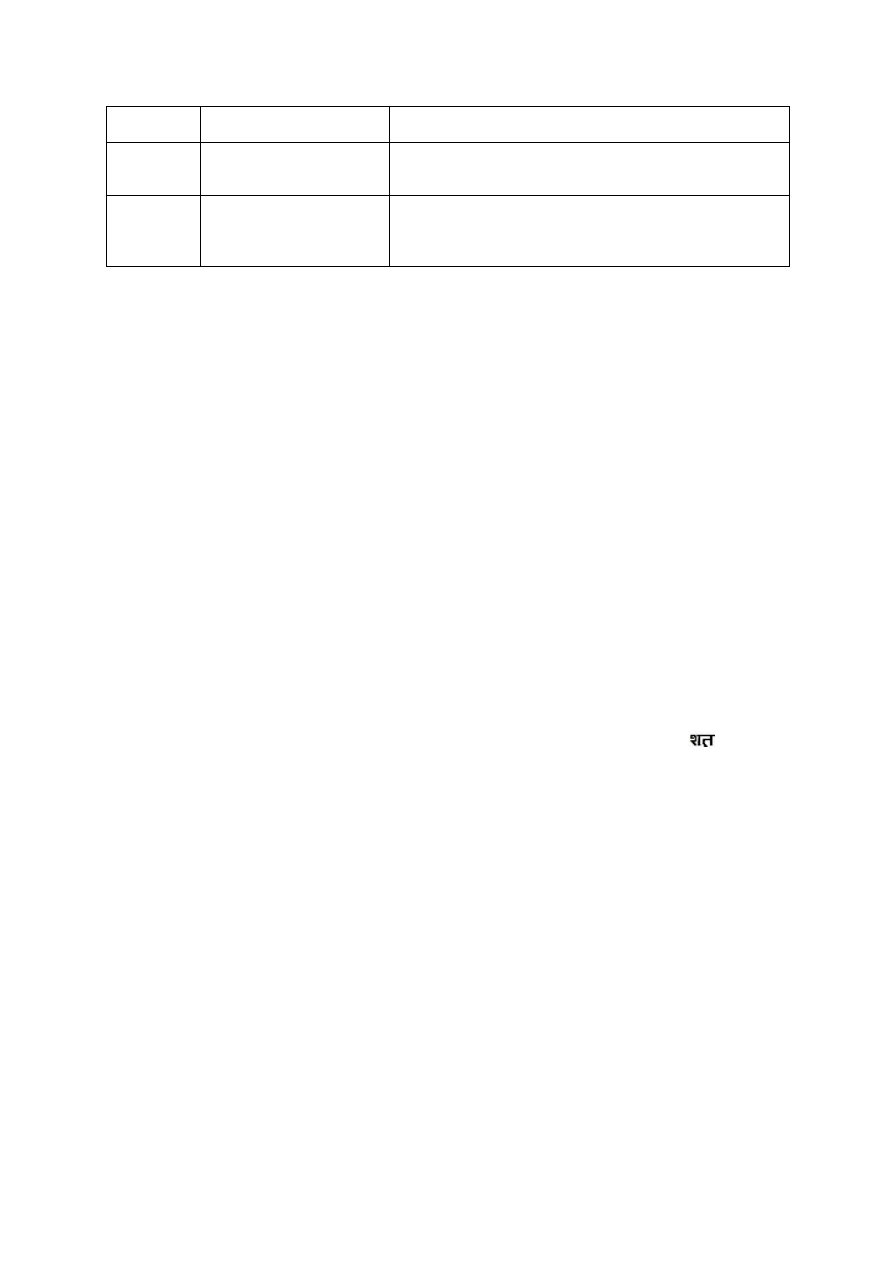

Table 3. Comparenda of the phonology of Ancient Egyptian and Akkadian numerals

Numerals

Ancient Egyptian

numerals

Akkadian

numerals

30

Remarks

One

wa

išten

Seemingly, no phonological similitude with

Ancient Egyptian (hereafter A.E.)

Two

Snw

Snw

Snw

Snwiiii

šina

Phonologically very close with A.E.

Three

xmt

šalaš

Phonologically extremely distant, despite a

possible shift from x to š is possible (as

stated above).

Four

fdw

erbe

No phonological similitude, clearly a

cognate of for example arbaa (رأ) in

Arabic

Five

diw

x

amiš

No phonological similitude

Six

ssssiiiissss

šeššet

Phonologically very close

Seven

sfx

sfx

sfx

sfx

sebe

Phonologically close, as shift from “f”

to “b” is well attested

Eight

xmn

xmn

xmn

xmn

samānā*

Phonologically very close with A.E.

Nine

psD

psD

psD

psD

tiše

Phonologically relatively close.

Ten

mD

ešer

No phonological similitude, clearly a

cognate of ashar (ة) in Arabic

Hundred

Snt

me'at

No phonological similitude, but the word

may in fact distantly related (see below)

Thousand

xA

līmu

No phonological similitude but the words

are in fact very distant cousins through

successive shits (see below).

Ten thousand

Dba

ešer līmi

No phonological similitude

Hundred thousand

Hfnw

meat līmi

No phonological similitude

Million

HH

lim

No phonological similitude

So many dissimilitudes are present in Table 3 that it is quite clear that the numerals of Ancient Egyptian

and Akkadian belong to two different linguistic groups; a marking conclusion in view of the commonly

assumed exclusive African-Asiatic appurtenance of Ancient Egyptian.

As just stated, it is moreover as if both languages had borrowed elements from one and the other, but in

different ways. Ever since he noticed them, these similarities and dissimilarities considerably disturbed the

author as aside from the fact that xA would be a cognate to the term “thousand” in “Satem” languages –

when “hundred” belongs to the “Centum” group - on the other hand Akkadian is according to our

current classification a “Semitic” language

31

. What the Akkadian numerals for “100” and “1000” confirm

in view of their obvious phonological breaks in Table 3 with their equivalent Ancient Egyptian and

seemingly “Indo-European” numerals. So as to attempt to clarify further this disturbing state of affair, the

author decided to systematically compare the terms

32

for numerals in additional Afro-Asiatic, Indo-

European and Semitic languages

33

, plus Proto Indo-European – obtaining Table 4 (below). Of course

comparenda between Indo-European and Semitic languages of columns to the right of Proto-Indo-

European in Table 4 have since long been done, but the author is nor aware that Indo-European numerals

30

Source: Association Assyrophile de France: Online dictionary:

http://www.premiumwanadoo.com/cuneiform.languages/dictionary/index_en.php

31

Akkadian is attested in names since around 2800 B.C. and in full text around the mid third millennium (George, 2007: 31-71).

32

The terms, i.e the names of the numerals and not the signs which are used to express them in several of the above listed

languages.

33

Ancient Egyptian, Coptic and Beja are first tabulated since they are parent languages. Proto Indo-European is inserted for

comparison, then three Indo European languages are tabulated from Sanskrit, the older to Greek and Latin which are – in this

order – more recent; note than an array of other “I.E.” languages could have been also tabulated. Then two Semitic languages are

present in the final columns; first Akkadian which is very ancient, and finally Arabic which is comparatively recent. In between,

intermediate Semitic languages could also have been tabulated such as Aramaic or Hebrew, but for lack of space only two

examples of Semitic languages are listed.

6

of the listed languages - i.e. Sanskrit, Latin and Greek - have been compared to Ancient Egyptian (itself

in company of Coptic and Beja) for a transverse comparenda aiming to establish the “I.E.” and “P.I.E.”

etymology of some of the Ancient Egyptian numerals:

Table 4. Comparenda of the terms for the numerals of a selection of “Afro-Asiatic”, “Indo-European” and “Semitic”

languages with Ancient Egyptian numerals

34

No.

Egyptian

Coptic

Beja

35

P.I.E.

Sansk

rit

36

Greek

Latin

Akkadian

Arabic

1

Oua

*Hoi-wo

37

ένα

unus

د

2

snau

*d(u)wo

δύο

duo

نا

3

0omnt

*trei

38

τρία

trēs

4

ftoou

*k

etwor

39

τέσσερα

quattuor

رأ

5

+ou

*penk

e

πέντε

quīnque

6

soou

s(w)eḱs

40

έξι

sex

7

Sa0f

*septm̥

επτά

41

septem

8

0moun

*h

eḱtou

42

οκτώ

octō

9

2it

*(h

)newn̥

εννέα

novem

10

mht

*deḱm̥(t)

δέκα

decem

ة

100

0e

*ḱm̥tom

εκατό

centum

#

1000

0o

*

eslo

χιλ

mille

#

أ

10.000

tba

-----

[b[i]gê]?

43

----

----

#

----

100.000

-----

-----

?

----

----

#

----

1 M

-----?

44

?

εκατοµµύριο

milio

#

ن

As a next analytical step, and so as to lift the walls created by these languages’ respective alphabets, the

phonology of each term is transliterated in common Latin letters

45

in the additional Table 5 (below).

34

Where no specific sign or term exist for a numeral “----“ is indicated ; of course the numeral may be expressed in any language

by combining numerals.

35

Source: Wedekind & al. (2005)

36

The Sanskrit is in Devaganari form. The terms in the table are the written-pronounced form of the numerals, not the signs

representing each individual number which also exist.

37

Also *Hoi-no-//*Hoi-k(

)o, the author has selected that which is closer of A.E. of the three reconstructions.

38

*trei- (full grade) / *tri- (zero grade).

39

*k

etwor- (o-grade) / *ketur- (zero grade)

40

s(w)eḱs; originally perhaps *weḱs

41

Shaded in grey as the “s” disappeared, but clearly a cognate of A.E.

42

Also *oḱtō, *oḱtou – clearly showing the different shifts towards which both Ancient Egyptian and Greek went.

43

Nostratic Dictionary 03ND #178 & 19D #178. Dolgoposky lists [b[i]gê] “much”, as in Hamito-Semitic (Ch:CCh:FIM) b3w as

well as Avestan baē-var, baē-van, New Persian bivär “ten thousand, myriad”, etc… A link with A.E.

Dba

and hence Coptic tba

seems very likely.

44

The author could not find the term for “million” in Coptic, including in Crum (1939)’s dictionary.

45

Readers versed in linguistics will allow, for the purpose of the experiment, a simplification for sounds/diacritics absent from

English and/or other modern I.E. languages.

7

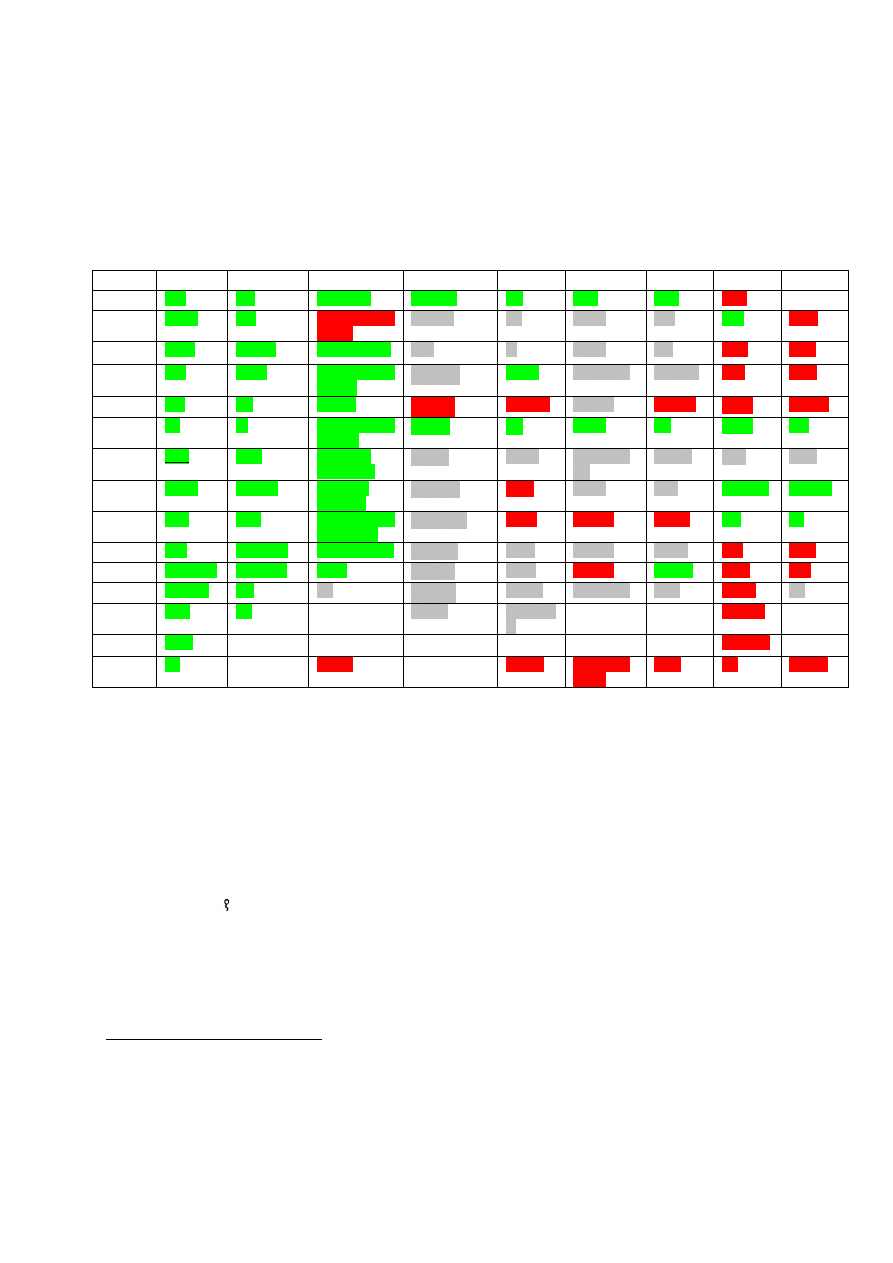

Thereafter, systematically comparing each time with the Ancient Egyptian numeral of column 1, cognates

of the various listed languages are underlined: in green when they are close to their Ancient Egyptian

equivalent, grey when they are mid to distant ones, red when they are phonologically very distant or have

no phonological relation; an experiment aiming to see if some grouping could be revealed.

Table 5. Comparenda of the simplified transliteration of numerals for the languages presented in Table 4

No.

Egyptian

Coptic

Beja

P.I.E.

Sanskrit

46

Greek

Latin

Akkadian

Arabic

1

oua

oua

gaal / gaat

*Hoi-wo

éka

ena

unus

išten

wahed

2

shnwï

snaï

maloob

/

maloot

*d(u)wo

dvi

thio

duo

šina

etnen

3

khmt

shomnt

mhay / mhayt

*trei

trí

tria

trēs

šalaš

talata

4

fdw

ftwou

fadhig

/

fadhigt َ

*k

etwor

chatúr

tessera

quattuor

erbe

arbaa

5

dïw

tou

ay / ayt

*penk

e

pañchán

pente

quīnque

ḫamiš

khamsa

6

sïs

so

asagwir

/

asagwitt

s(w)eḱs

ṣáṣ

eksi

sex

šeššet

seta

7

sfkh

shasf

asaramaab

/asaramaat

*septm̥

saptán

efta/ep

ta

septem

sebe

sabaa

8

khmn

shmoun

asumhay/

asumhayt

*h

eḱtou

aṣṭán

okto

octō

samānā*

tamanya

9

psdj

psise

ashshadhig /

ashshadhigt

*(h

)newn̥

návan

ennia

novem

tiše

tsa

10

mdj

meet/djet

tamin / tamint

*deḱm̥(t)

dasán

theka

decem

ešer

ashar

100

shnt (Snt)

shé/sheet

sheeb

*ḱm̥tom

satam

ekato

centum

me'at

mi’a

1000

kha (xA)

sho

alif

*

eslo

sahasra

khillia

mille

limu

47

alif

10.000

djba

tba

-----

[b[i]gê]

dasasahas

ra

-----

----

ešer līmi

-----

100.000

hfnw

-----

-----

?

-----

----

meat līmi

-----

1 M

hh

-----?

million

---

kotizah

ekatomu

rrio

milio

lim

millyun

Once distance between cognates are expressed in colours, it becomes suddenly unequivocal that Ancient

Egyptian numerals bear similitudes not only to Semitic languages such as Akkadian or Arabic – the latter

not being surprising in view of their classic Afro-Asiatic identity of AE - but also to the two different

“Centum/Satem” classes of “IE” languages. In the latter respect, the consistence, throughout all

languages, of the phonology of the numeral “six” is undisputable. Whereas the phonological similitude

between Ancient Egyptian and Sanskrit numerals for “four”, i.e. fdw/chatúr

48

and “six”, i.e. sïs/ṣáṣ is

fascinating

49

.

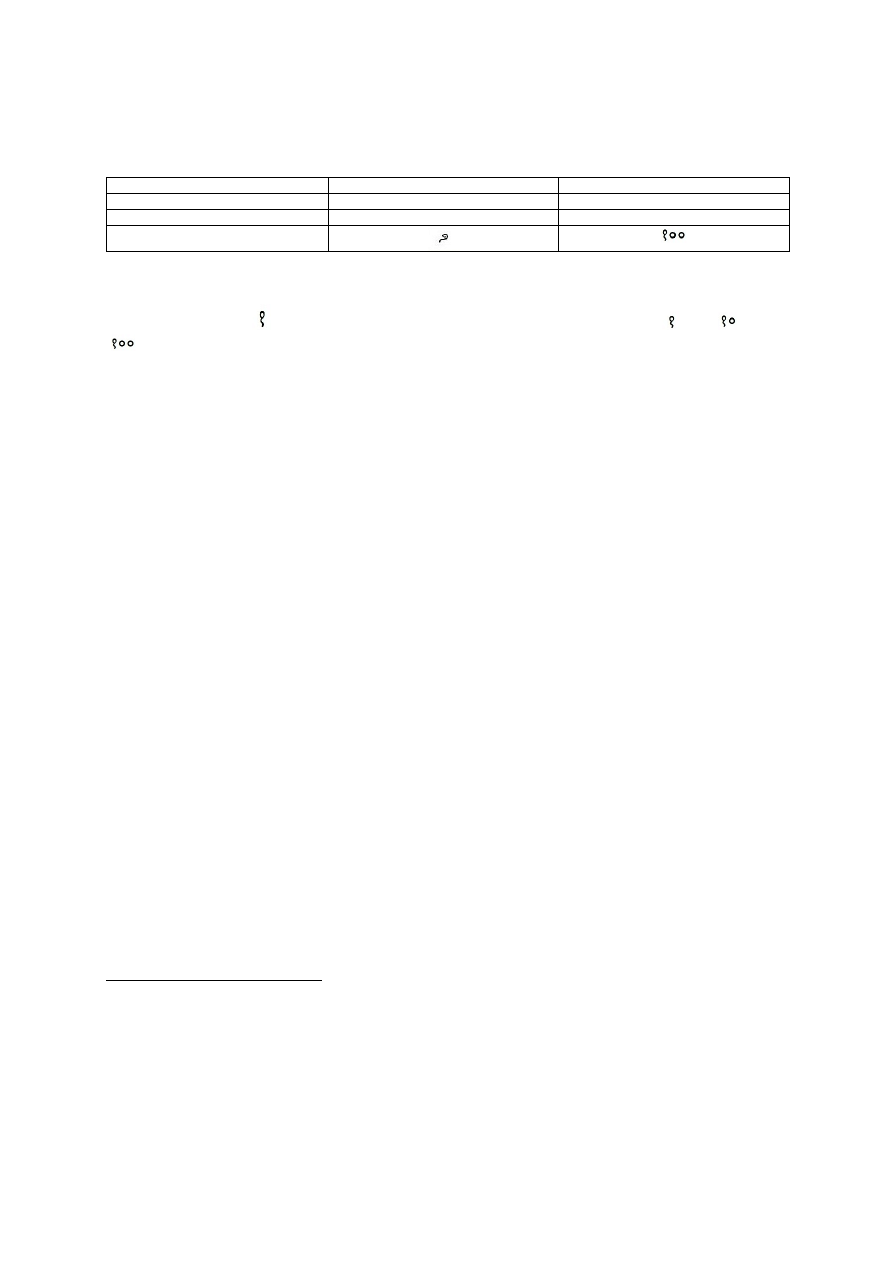

Where Sanskrit is again concerned, not least interesting is the “coincidence” that the numeral “100” is

started by a sign

which is so much looking to the sign “100” (Gardiner: V1). A sign attested in Egypt

since the first dynasty

50

, allowing the following Table 6 if value, phonology and symbolism are put in

parallel:

46

The Sanskrit is in Devaganari form.

47

Distant from ancient Egyptian, but very close to Greek and Latin.

48

If for sïs/ṣáṣ the phonological shift will be obvious to non-linguists, for the comparenda fdw/chatúr the shift may not be so

much. However the shifts: f< >ch & d< >t & w< >ú seem reasonable without presuming of the ancestry of one term over the

other, i.e. of the chronological direction/evolution of the shift (hence indicated here as < >).

49

Even if the Ancient Egyptian term is hiding a vowel.

50

Wb 4, 497.9-12.

8

Table 6. Comparenda of the values, transliterations and symbolisms of the numeral for “100” in Ancient

Egyptian and Sanskrit

Ancient Egyptian

Sanskrit

Numeral (i.e. value)

100

100

Transliteration (i.e. phonology)

shnt (Snt)

satam

Sign (i.e. symbolism)

Such similitudes are made even more disturbing when it is remembered that Ancient Egyptian numerals

like Sanskrit are based on a decimal system – unlike Akkadian where the system is sexagesimal (60) - and

that therefore the sign

is precisely the same used in Sanskrit to start the numbers 1 (

), 10 (

) or 100

(

), as well as all numbers between 11 to 19. Since the zero does not exist among Ancient Egyptian

numerals

51

, so it can perhaps be surmised that if any borrowing occurred the two “00” would not be

written – as it the case for Akkadian/Babylonian. This series of coincidences could not be left unnoticed

by the author and will have in the future to be clarified. Particularly as if a decimal system and its attached

numbers were adopted from abroad by Ancient Egyptian, one can easily tentatively imagine that even if

they ever re-adapted the signs to fit their own hieroglyphic system and taste, it would be possible that they

might have kept an element of the initial notation

52

. The problem is that Vedic Sanskrit numbers,

according to this language’s present history, would date at the earliest of the mid-second millennium B.C.

whereas the Egyptian sign for hundred is attested since the First dynasty, hence around 3030-2800 B.C.

53

;

a discrepancy of up to a millennium and half.

Now aside from the fact that the Centum/Satem division of Indo-European languages is already regarded

as tenuous because too rigid by many linguists, the author had on his own asked himself if some remote

language could not have been at the origin of these common similitudes. Particularly as ancient Egyptian

numerals which are cognates of “I.E” languages give – as already stated above - the impressions of having

endured a global separate phonological shift and evolutionary path. A conclusion which the author

reached alone unaware that shortly before putting his thoughts in the present text some linguists of the

Nostratic school

54

had started to precise the genealogical and evolutionary tree of the various languages

composing the Nostratic group. Concluding independently that Afro-Asiatic (Hamito-Semitic) once

followed a distinct linguistic evolutionary path

55

; hence as Bomhard

56

just stated:

“Some scholars would like to remove Afroasiatic (Hamito-Semitic) from Nostratic proper and make it a sister

(“coordinate”) language, while others, including Dolgoposky, Illiê-Svityê, and Bomhard [the author refers to himself],

see it as a full-fledged branch of Nostratic. However, this is not necessarily an “either/or” issue. Another explanation is

possible, namely, the recognition that not all branches of Nostratic are on equal footing. Afroasiatic can be seen at the first

branch to have become separated from the main speech community, followed by Dravidian, then by Kartvelian, and finally, by

Grenber’s Eurasiatic which was the last branch to become differentiated into separate languages and language families”.

51

The term nfr sometimes used sometimes at the end of Ancient Egyptian calculations is not equal to the “zero”, but means

“good” in the sense of “even”.

52

As is the case for the creation of many known alphabets, particularly for Indo-European languages, the authors have sometimes

slightly modified letters existing in previous alphabetical systems.

53

As per UEE Chronology (http://uee.ucla.edu/contributors/chronology.htm).

54

One only needs to quote Renfrew’s introduction of Dolgoposky’s gigantic Nostratic Dictionary (2008)

54

to explain the

Nostratic hypothesis, i.e.: “that several of the world’s best-known language families are related in their origin, their grammar and their lexicon, and

that they belong together in a larger unit, of earlier origin, the Nostratic macrofamily”. This macrofamily usually includes Afroasiatic, Uralic,

Altaic, Kartvelian, Dravidian and of course Indo-European languages (Renfrew, 2008: V.).

55

Dolgoporsky, 2008 : 28-33; Bomhard, 2008 : 7.

56

Bohmard (2008: 7).

9

Conclusion

The two main conclusions resulting from the above analysis

57

are:

a/ - that several ancient Egyptian numerals are cognates of equivalents in “I.E” languages, as well as in

Proto “Indo-European”

58

; which is to say that several Ancient Egyptian and modern “Indo-European”

numerals share a common etymology.

b/ - that there is an “Indo-European”

59

and/or Proto “Indo-European” linguistic stratum in ancient

Egyptian which will have to be better distinguished in the future. Particularly as numerals – aside from

their specific utilitarian nature - which may have caused them to be introduced under special historical

circumstance - only offer a window in what is a major linguistic issue, and one evidently requiring

substantial additional work where Ancient Egyptian vocabulary and grammar as a whole is concerned.

Point “a/-” is novel in so far as the author is not aware that may be found anywhere in the Egyptology

literature that ancient Egyptian numerals are cognates of “I.E.” numbers. However, as the author closed

this manuscript, he found that similitudes between the grammars of Ancient Egyptian and “Indo-

European” languages have already been noted four times in passim by Loprieno (1995), since he wrote:

•

Page 82: “The evolution from a semantic to a sytactic mood, from a verbal category whose choice depends only the

speaker's attitude tot he predication to a form only used in a set of subordinate clauses, is know from Indo-

European and Afro-Asiatic languages”.

•

Page 100: “wnt is a feminine derivative from the root wnn "to be", ntt is the feminine, i.e. neuter form of the

relative pronoun ntj, according to a pattern of evolution also known in Indo-European languages: see Greek

Ôti

,

Latin quod, English that”.

•

Page 127: “From an etymological point of view, nn is presumably the result the result of the addition of an

intensifier to the nexal nj, much in the same way in which similar predicate denial operators developed in Indo-

European languages: Latin non <*ne-oenum "not one", English not, German nicht *ne-wicht "not-something",

etc...”.

•

Page 249: “nfr Hr "the man whose face is beautiful" <*"the man - the face is beautiful." This pattern is similar

to the so-called bahuvrihi constructions in Indo-European and to Semitic patterns such as...[etc..]”.

Aside from a single other mention p. 51 and three mentions in notes

60

, this is the only times when the

term “Indo-European” is mentioned by Loprieno in his now classic textbook and nowhere in relation to

numerals

61

concerning which Loprieno states “…Egyptian words for numbers show a wide array of correspondences

with other Afroasiatic languages, most notably with Semitic and Berber"

62

. Where the link of ancient Egyptian

language with “Indo-European” languages is concerned – point “b/-” Satzinger (S. (2): 8 & 13) in his study

of the etymology of the Coptic word “ashes” – admittedly hence late - did not hesitate to investigate

“Indo-European” terms, posing in the end of his study the following question: “Could the word be loaned

from any other language of those mentioned above? Indo-European has much evidence of the simplex root KR “fire”, “to

burn”? Egyptian contacts with Altaic languages may be excluded. Among the Nilo-Saharan languages, Nubian is the only

one that may be considered from a historian’s standpoint, but the evidence for the root in question is absent, both in Old

57

Supplemented by the vocabulary mentioned at the beginning of the study.

58

Aside from also recognised words/lexemes and grammatical forms.

59

The term Indo-European is deliberately left in brackets throughout the article in view of its current definition; one which may

be subject to revisions in the future.

60

Aside from bibliographical references where the terms appear in titles.

61

This is also true of Allen (2001 : 98-104) in his Middle Egyptian Grammar in the chapter on numbers, and too any other sources

to be cited here. As the literature concerning Ancient Egyptian is vast, the author does not – as a reserve - exclude that such link

could have been made but if it has, the arguments presented evidently did not alter the commonly established view of Egyptology

on the Afro-Asiatic (Hamiot-Semitic) identity of Ancient Egyptian.

62

Loprieno (1995: 71).

10

Nubian and in the modern Nile and Mountain Nubian languages.” [Etc...]”. Satzinger finally reverting to Ancient

Egyptian for a more plausible explanation despite “much evidence”, as he says, for the root in I.E. The

author quoting the above not to support or refute Satzinger’s etymology of the word “ashes”, but to

underline his methodology which does not hesitate to examine, among others, the possibility of an “I.E”

origin for the studied term within the frame of the Nostratic theory. Hence Satzinger’s choice of “The

Ethymology of Coptic “Ashes: Chadic or Nostratic?” for his study. In fact the Nostratic theory had already found

conscious or unconscious adherents among Egyptologists, since as the author equally discovered while

finishing this article El Daly recently pertinently stated:

“Some native Egyptian writers were familiar with Coptic, Greek and Arabic (Atiya 1986: 92). This process was

undoubtedly helped by the fact that the ancient Egyptian and Arabic languages have so many roots and features in common

that it has even been suggested that ancient Egyptian was the basis of Arabic (Kamal, 1917: 331). That ancient Egyptian

and Arabic are related (cf. Youssef 2000) should not be more surprising than that Egyptian and Hittites are related. As

John Ray has suggested "It is becoming more and more likely that the Semitic, Hamitic and Indo-European languages were

originally one" (Ray, 1992: 132), a view supported by earlier extensive research on the relationship of Arabic to other

language groups (Ismail, 1989; Kubaissi, 2000)...[etc..]"

63

.

The presence as early as the Pyramid Texts or the First Dynasty of numerals which are cognates of “IE”

languages – as well as as Proto “Indo-European”, demonstrates a linguistic input at the times of the

formation of the Ancient Egyptian civilisation. As otherwise it would need to be established that the

decimal system was born in Egypt, and then in view of the phonological similarities described above, that

it spread into other languages. Something which our present knowledge of numbers – also widely assumed

to come from the Indian continent but which recent research seem to show as coming from the very Far

East – makes unlikely. Where ancient Egyptian vocabulary as a whole is concerned the situation may even

be more complex, as phonological similarities with Proto “Indo-European” as well as Proto “Afro-

Asiatic”

64

will have to examine; unless this was originally a same language which, at one point in time, split

In this respect, the author is more and more compelled to admit, including in view of his own analyses

such as here presented, that the conclusion of Nostratic theorists concerning a common vanished proto-

language which existed 12.000 years ago or far earlier and which was the ancestor of many existing

languages of the ancient world - including Ancient Egyptian – makes increasingly sense

65

.

63

El Daly, 2005: 64. The author was yet again not aware of this conclusion until closing his manuscript.

64

See for example Ehret (1995).

65

As the author closes his manuscripts, he notices that Dolgopolsky (2008: 426) has made a linguistic link between

Snwi

“two” in Ancient Egyptian and Nostratic *čìń

“other”, from which he derives Hamito-Semitic *θin- “two”,

etc… as well as Kartvelian (an non “Indo-European” Ibero-Caucasian language) *č|š

, among other proposed

etymologies. Other such interesting links may exist in his Nostratic Dictionary, the size and extremely dense – not to

say difficult – format of which will require some time to discover.

11

B

IBIOGRAPHY

ALLEN, J. P. Middle Egyptian, An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge; 2001

ANDREW G. "Babylonian and Assyrian: A History of Akkadian", In: Postgate, J. N., (ed.), Languages of Iraq, Ancient

and Modern. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq: 31-71; 2007

BEEKES, R. S. P. Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Comrie, B., 1993

BOMHARD, A. R. (2008). A Critical Review of Dolgopolsky's Nostratic Dictionary. Available online at:

http://www.nostratic.ru/books/(287)bomhard-dolgopolsky.pdf; 2008

CRUM, E. A Coptic Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1939

DIAKONOFF, I.M., KOGAN, L., 1996. Addenda et corrigenda to the Hamito-Semitic etymological dictionary

(HSED)by V. Orel and O. Stolbova.. Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenländischen Gesellschaft 146: 25–38.

DOLGOPOSKY A. Nostratic Dictionary. MacDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge University.

Available online at:

http://www.dspace.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/196512

; 2008

EHRET, C. Reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic (Proto-Afrasian): vowels, tone, consonants, and vocabulary. University of California

Press; 1995.

EL DALY, O. Egyptology: The Missing Millennium. Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. UCL Press, London; 2005

SATZINGER, H. The Etymology of Coptic “Ashes”: Chadic or Nostratic?. Available online at:

http://homepage.univie.ac.at/helmut.satzinger/Texte/Ashes.pdf

; S. D. (1)

SATZINGER, H. An Egyptologist's perusal of the Hamito-Semitic Etymological Dictionary of. Orel and Stolbova. ,

Wien; available online at:

http://homepage.univie.ac.at/helmut.satzinger/Texte/OrelStol.pdf

; S.D. (2)

KOGAN, L., 2002. Addenda et corrigenda to the Hamito-Semitic etymological dictionary (HSED) by V. Orel and

O.Stolbova (II). Journal of Semitic Studies 47, 183–202.

LOPRIENO, A. Ancient Egyptian, a linguistic introduction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 1995

STOLBOVA O. V. and OREL V. E. Hamito-Semitic Etymological Dictionary. Materials for a Reconstruction. Brill

Academic Publishers; 1994

RAY, J. Are Egyptian and Hittite Related? In: Lloyds AB (ed.). Studies in Pharaonic Religion and Society in Honour

of Gwyn Griffiths. EES, London; 1992

RENFREW, C. Preface. In: Dolgoposky A. Nostratic Dictionary. MacDonald Institute for Archaeological Research: V-

VIII. Available online at:

http://www.dspace.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/196512

; 2008

SIHLER, A. L. New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin. Oxford University Press; 1995

TAKÁCS, G. Etymological Dictionary of Egyptian, Vol. I – A Phonological Introduction. (Handbuch der Orientalistik, I.

Abteilung: Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten, Band 48). pp. xix, 471. Leiden, Brill, 1999.

WEDEKIND, K. WEDEKIND, C. MUSA, A., Beja Pedagogical Grammar Introduction. Aswan 2004 - Asmara

2005

Available

online:

http://www.afrikanistik-

online.de/archiv/2008/1283/beja_pedagogical_grammar_final_links_numbered.pdf

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

The?nign?velopment of Ancient Egyptian Patriarchy

Body language is something we are aware of at a subliminal level

There are a lot of popular culture references in the show

Why Are Amercain?raid of the Dragon

fitopatologia, Microarrays are one of the new emerging methods in plant virology currently being dev

ANCIENT EGYPTIANS AND MODERN MEDICINE

Body language is something we are aware of at a subliminal level

16 Egyptian (Beyond Babel A Handbook of Biblical Hebrew and Related Languages)

Simon Aronson Memories Are Made of This

Lee Brazil Chances Are 4 Ghost of A Chance

Ancient Egyptian

Self Identification with Diety and Voces in Ancient Egyptian and Greek Magick by Laurel Holmstrom

Memories Are Made Of This

05 WoW War Of The Ancients Trilogy 01 The Well of Eternity (2004 03)

ATM SEQUENCE VARIANTS ARE PREDICTIVE OF ADVERSE RADIOTHERAPY RESPONSE AMONG PATIENTS TREATED FOR PRO

więcej podobnych podstron