CONSTRICTIVE CONSTRUCTS:

UNRAVELLING THE INFLUENCE

OF WEBER’S SOCIOLOGY

ON THERAVADA STUDIES SINCE

THE 1960S

Phibul Choompolpaisal

The present article assesses the substantial impact of Weber’s sociology upon studies

of Theravada Buddhism. In doing so, it reviews several important works on

Theravada Buddhism with a view to analysing the use, influence and implications of

Weber’s sociology in Buddhist studies. After providing a broad overview of this

influence in Theravada studies the discussion culminates with a more detailed

discussion of the impact of Weber’s sociology on the study and representation of Thai

Buddhism.

Introduction

On a global scale, as a reflection of the increasing popularity of sociology,

1

many academics in the 1950s sought to study ‘Oriental societies’

2

through

Weber’s sociological views as portrayed in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of

Capitalism (1904 – 05, translation 1930; henceforth 1930). As Bellah’s (1963) paper

‘Reflections on the Protestant Ethic Analogy in Asia’ reflects, many academics from

1949 to 1962 used Weber’s hypothesis

3

to help explain the process of socio-

economic change in Asian countries as well as the growing importance of

entrepreneurship in Asian societies (Bellah, 1963, 52). Following this sociological

trend, academics in the field of Indian studies (including Singer,

4

Elder,

5

McClelland

6

and Ames

7

) in the 1950s and the 1960s also attempted to employ

Weber’s (1930) ideas in their studies.

In the study of Theravada Buddhism, many writings in the 1950s and the

1960s by Leach,

8

Bechert, Evers, Obeyesekere,

9

Tambiah

10

and others

11

also

showed a new tendency to employ sociological theories including those of

Contemporary Buddhism, Vol. 9, No. 1, May 2008

ISSN 1463-9947 print/1476-7953 online/08/010007-51

q

2008 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/14639940802312600

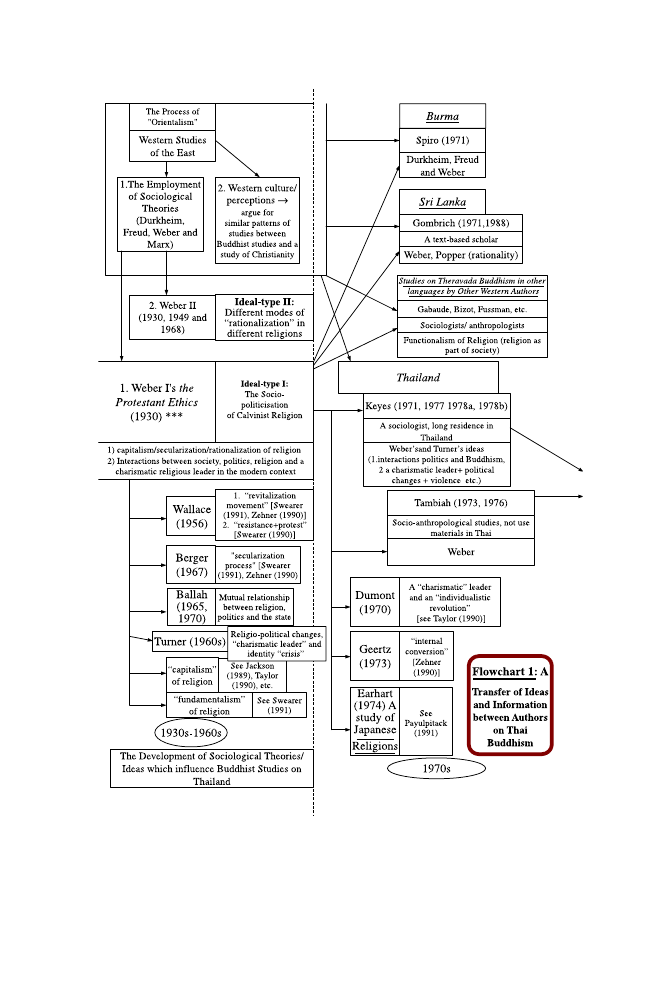

Weber’s. In turn, I contend that, through a transfer of information and ideas, most

contemporary writers on Buddhist studies on both South Asia and Southeast Asia

have been either directly or indirectly influenced by Weber’s sociology, whether

the reception of such influence on the part of these scholars is conscious or not.

Despite more than four decades of such influence, no attempt has been made to

explore how and why Weber’s sociology has become so influential to the entire

field of Buddhist studies. Nor have academics critically assessed the use of Weber’s

sociology in this field.

12

While the writing process of major works on Buddhist society can be

regarded as a process of construction or synthesis (the fusing together of

information gathered and ideas imposed behind the framing of works), this paper

may be regarded as the de-construction (or an analysis) of major works in the field.

The aim, then, of the present paper is to unravel pieces of information and

elements of ideas that underlie the construction of each work using a

hermeneutical approach.

13

In other words, I am seeking to find out or interpret

the factors, especially the conceptual frameworks, behind the construction of

each work, in order to explain how this leads the authors to construct their

representation of Theravada in particular ways. These factors (as will be illustrated

hereafter) are a combination of: (1) specific conceptual frameworks (western

sociologically theoretical worldviews, western perceptions of things, specific fixed

academic views influencing the way the research was conducted, etc.); and

(2) specific academic ways of using and representing such information. My aim is

then to deconstruct accounts of Buddhist societies and explore how each

interpretation comes about because of the fusing together of information, ideas

and methodology, whether this academic process of producing works on the part

of scholars be conscious or not. This paper then represents the first attempt to

review and critically analyse the ways in which Weber’s sociology has influenced

the construction of knowledge in Theravada Buddhist studies since the 1960s. This

paper will review several of the most influential works on Buddhist studies in both

Sri Lanka and Thailand. It will focus on how each author’s ideas, arguments,

underlying methodology, explanations and conclusion are shaped or influenced

by Weber’s sociology. In this way, the present paper will help to broaden our

understanding of academic interpretations of Theravada Buddhism by

transcending what each author says to give an analysis of how and why he/she

says this.

As already indicated, methodologically speaking, the paper will review and

analyse the creation of each academic work from a hermeneutical perspective.

From a hermeneutical view, each work, its arguments and conclusion come about

due to the fusing together of: an interpreter’s pre-understanding; information and

ideas provided by previous authors; and the interpreted’ (or the subject that an

academic is attempting to study), which in a discussion of this paper is ‘the

Buddhist societies and the lives of the native Buddhists’. Within these categories,

an interpreter’s position is determined by his/her personal ideas, interests,

academic background, expertise, theoretical considerations and preferred

8

PHIBUL CHOOMPOLPAISAL

methodology—the combination of these factors leads to an interpreter’s

pre-understanding. In undertaking research, each author also either obtains or is

partly influenced by further ideas and information as provided by other authors’

works. ‘Pre-understanding’ and the adoption of other authors’ ideas and

information, in turn, create an academic interpretation of ‘the interpreted’ as

reflected by an interpreter. Since ‘the meaning of the interpreted’ is defined by an

interpreter, it becomes a reflection of how an interpreter perceives ‘the

interpreted’. The meaning of the ‘interpreted’ is thus the product of both

interpreter and interpreted, and not necessarily the same as the interpreted itself.

In reflecting on academic works, I assume in this paper that neither

academic knowledge as constructed in the field of Buddhist studies nor insiders’

explanations necessarily portray a single reality of Buddhist societies. I agree with

Gombrich that what ‘insiders’ (or theologians) consciously explain they believe

and practise may or may not be the same as what they are unconsciously doing

(see Gombrich, 1971). However, since academics’ works are often influenced

by their own ‘pre-understanding’, sociological ideas and a transfer of ideas and

information, their resulting interpretation may not be acceptable to or even

recognisable by ‘insiders’. That is why insiders’ interpretations of Buddhist

societies are not necessarily the same as those of academic outsiders.

In this paper, an understanding of Weber’s influence and how each work is

constructed will help us to see how it can be problematic merely to take

information and ideas from other academics. This is because each interpretation of

a Buddhist society is often the by-product of some ‘pre-constructed’ sociological

ideas, and thereby has limitations due to its own ‘pre-understanding’,

methodology and theoretical underpinnings. Information and sociological ideas

as derived through an academic process can then become too specific, limited and

sometimes unrealistic to insiders, and as such may misrepresent the interpreted in

ways of which the new interpreter and his/her audience are unaware. In my view, it

is high time that we become more aware of three types of information and ideas:

(1) information and ideas as obtained and perceived through some specific

academic theoretical and methodological approach; (2) beliefs and practices as

consciously perceived by ‘insiders’; and (3) the real context of the society. This will

help us better understand: each author’s and insiders’ position; how each author

seeks to interpret the ‘sign’ (each local Buddhist community) and which approach

he/she takes to study it; how ‘the signified’ (or each interpretation of the sign)

comes about; and a contrasting picture between the ‘sign’ (each local Buddhist

community that an author studies) and ‘the signified’ (an author’s representation

of that local Buddhist community), or between ‘reality’ and ‘academic

representation’. This will, it is hoped, help raise an academic awareness about a

void within the insider – outsider dialogue (or the theologian – sociologist dialogue)

that has emerged over decades in Buddhist studies.

In spite of an effort being made to deal with as many works as possible in

the field of Buddhist studies in Sri Lanka and Thailand, this paper can only explore

a selection of the more important works. Many more academic ‘voices’ could have

INFLUENCE OF WEBER’S SOCIOLOGY ON THERAVADA STUDIES

9

been included had I had more space. I must also emphasise at the outset that

although this paper offers criticism and challenges many works, I nevertheless

appreciate the valuable contributions that such works have made. Indeed, it is my

very appreciation of these works that has led me to read such studies extensively

and thence to trace the genre back as far as possible to the beginnings of what

might be called ‘the Weberian sociological study of Theravada Buddhism’. Finally,

although this paper argues that academic interpretations are not always

acceptable to ‘insiders’, it does not intend to suggest that such work should be

rejected. Rather, it simply attempts to point out a void within insider – outsider

dialogue in Buddhist studies. This is because insiders and outsiders have different

worldviews and methodologies for the study of Buddhism. So academic

interpretations are valid, but only within western academic worldviews and not for

insiders inhabiting traditional Buddhist worldviews.

In organising this paper, I shall start by discussing some of Weber’s main

sociological ideas. After that, I shall look at academic works on Theravada Buddhism

in the 1960s, focusing on the important works of Bechert, Evers and Obeyesekere.

I shall then move on to explore the influence of Weber’s sociology on Buddhist

studies in Sri Lanka through an analysis of the major works of Gombrich,

Obeyesekere and Bond during the 1970s and 1980s. Finally, I will look at Weber’s

influence on even very recent Buddhist studies in Thailand, focusing on works of

Keyes, Tambiah, Suksamran, Jackson and Swearer during the 1970s and 1990s.

Weber’s sociology

I will now briefly explore Weber’s ideas as expressed in Economy and Society

(1968)

14

and The Methodology of Social Sciences (1949), as it will subsequently help

understand how Weber’s ideas have influenced Buddhist studies. Combining both

subjective and objective modes of interpretation, Weber believes it is important to

understand subjectively social behaviour/action (which is guided by the intention

to achieve a particular goal) in order to be able to objectively reconstruct the

meanings of social action. Therefore, Weber proclaims that social behaviour can

only be fundamentally understood through a subjectively empathetic investi-

gation of the individual action rather than an objective enquiry into the

collectives.

15

Weber hypothesises that an interpreter, possessing imaginatively

empathetic skills, can perfectly understand the action of the interpreted as if (s)he

himself/herself were the interpreted.

However, because of the complexities of the social world, Weber believes it

is not possible to grasp the totality of social phenomena. He therefore only seeks

to approximate social reality and explain it causally. To this end, Weber can be

seen by theorists as proposing an academic technique that became useful for

academics who seek to study (religious) societies or any social phenomenon. By

coining the phrase, ‘ideal-type’, Weber can be seen as proposing that one way to

study any specific society (Society A) was by ‘comparing and contrasting’ this

society that we wished to study (Society A) with the theoretical model society (the

10

PHIBUL CHOOMPOLPAISAL

‘ideal-type’ Society B), which we already knew about.

16

For Weber, through a

‘comparative’ method, an ‘ideal-type’ society (or an ‘ideal-type’ pattern of

behaviours of people in the model Society B) became the conceptual framework

of reference, or a yardstick. By comparing the society that we were studying

(Society A) with the ‘ideal-type’ Society B, we can then evaluate and understand

the society we are studying, or ‘the actual actions of the interpreted’ (the observed

pattern of behaviours of people in society we are studying). By this comparative

method, Weber was seen by theorists as proposing at least two kinds of ‘ideal-

type’ society: the ‘rational’ and the ‘irrational’. While the former, based on ‘rational

actions’ of people, operates a logical mode of thinking and/or in a more

modernised way, the latter—which has traditional and more archaic features—

operates on an illogical basis, driven by emotional and other human distortions.

These two modes (rational and irrational) became ‘ideal-types’, a model

conceptual framework of reference that academics could use to compare and

contrast with the actual society they were studying in order to understand and

represent it (as well as the actual actions of people in that society).

Therefore, apparent benefits that academics could take from Weber’s ideas

included the possibility of explaining a (religious) society, either by ‘comparing

and contrasting’ it with Weber’s case studies (Weber’s Society A, Calvinism, etc.), or

by using the model conceptual framework, ‘ideal-type’ Society B, as developed by

Weber from those case studies. The latter requires one to assume that there was

no major difference between Weber’s model society of Calvinism and the

particular society (any new society A) that an academic is trying to interpret

(Parkin, 1982, 30 – 31).

By this means, Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1930)

proposes that through the westernisation and modernisation process, Calvinist

society has been transformed from being ‘irrational/traditional’ into ‘rational

capitalism’. Unlike ‘traditional’ Calvinism as an ‘ideal-type’ religion in the

traditional period, reform Calvinism as an ‘ideal-type’ religion in the modern

period becomes ‘rational capitalistic’ religion. For Weber, the ‘rational capitalistic’

reform Calvinism consists of both ‘the rational spirit of capitalism’ (or ‘the

normative’) and ‘the accumulation/wealth of materials’ (or ‘the institution’), and

therefore it ‘causally’ generates and promotes capitalist economic activity. When

the followers of Calvinist religion are inspired by the Calvinist teachings,

particularly the doctrine of ‘duty’, the religious path of ‘salvation’ and the values of

inner-worldly asceticism, ‘the rational spirit of capitalism’ functions to generate

and accelerate the surplus capital by:

(1)

encouraging the labourers to perform their good duty by working hard for their

(religious) community in response to their ‘salvation anxiety’,

(2)

encouraging the capitalists to invest the capital in order to increase productivity,

and

(3)

limiting consumption through encouraging an ascetic compulsion to save.

INFLUENCE OF WEBER’S SOCIOLOGY ON THERAVADA STUDIES

11

From the above conditions, Weber’s thesis then attributes the success and spread

of Calvinism to the rise of the bourgeoisie. This is because when the bourgeoisie

financially supports the ascetic priests, the priests provide teachings for the laity;

and these teachings encourage the labour to perform their good duty by working

hard. The Protestant Ethic, historically creating the values of the ‘capitalist spirit’,

therefore becomes the mechanism that indirectly helps generate secular activities

and legitimates social power. On the whole, Weber (1930), who proposed the

central idea of ‘rational capitalism’ (or ‘rational economic’ features of religion),

makes a connection between religious beliefs (and salvation anxiety), religious

duty, the investment of capital, an increase in productivity, the limit of

consumption, the existence of a surplus, and the overall effects of religion on the

growing economy and capitalism. So, when I use the phrase, ‘rational capitalistic’

(or ‘rational economic’) hereafter, it reflects all of the above conditions of ‘rational

capitalism’ regarded by Weber as having existed in Calvinist society.

While providing an important analysis of the mutual relationship between

religion and socio-polity, Weber’s Sociology of India (1958) also indicates his

awareness of the limitations of his own work (developed in relation to Calvinism)

when applied to oriental society. As Bechert points out, Weber claims—when

writing about Indian religion

17

—that Buddhism was originally a ‘specifically

unpolitical and antipolitical class religion’ (Bechert, 1991, 181); and that the

characters of Buddhism and oriental society were traditionally ‘irrational’ in a sense

that Buddhism and other oriental religions did not instigate social, economic and

political changes,

18

and in this were thus distinct from Calvinist society (Bechert,

1991, 181 – 182). For Weber, Buddhism was ‘a “product of quite positively

privileged classes”’ (Bechert, 1991, 181 – 182). He suggests that it ‘never attempted

to alter the world’s social order’ (Bechert, 1991, 181 – 182). He thus concludes that

it ‘was unable to develop a “rational economic ethic”’ (Bechert, 1991, 181 – 182).

In other words, for Weber, his conception of ‘rational capitalism’ is only applicable

to Calvinist society in the West. Weber explains this on the grounds that, from his

studies in India and China, he finds that in oriental society neither the ‘capitalistic

spirit’ nor ‘the institution’ (the accumulation of the wealth) has been developed

properly. For Weber, unlike the West, the East is not characterised by ‘rational

capitalism’ because oriental religions cannot provide a motivational drive for the

‘rational spirit’ to build up. Thus, Weber argues that the socio-economic nature of

oriental society remains ‘irrational’. While Weber endeavours to generalise his

theory of the approximation of social and historical reality as far as possible, he is

still aware of the differences between societies, particularly between the West and

the East.

Apart from Weber’s theorisation of ‘ideal-type’ and main analysis of Calvinist

society as explained above, there are other sociological ideas of Weber that are

developed as by-products of Weber’s analysis of Calvinist religion. Examples of

these ideas that also influenced subsequent scholars are Weber’s theorisation of

‘charismatic leadership’ and socio-religious – political changes. Moreover, Weber’s

analysis of primitive Buddhism and other Indian religions (which can be seen as

12

PHIBUL CHOOMPOLPAISAL

another ‘ideal-type’ different from the ‘ideal-type’ of Calvinist society) has also

influenced academic authors who sought to study Buddhism through a

sociological approach. As Bechert points out, Weber (1958) is influential in

provoking many academic thoughts; for example, the idea that changes in socio-

political conditions led to changes in religion, the mutual relationship between

Buddhism and rulers (the socio-political use of Buddhism ‘as a means of mass

domestication’, etc.), the relationship between Buddhism and social classes, and

so forth (Bechert, 1991, 186).

In my opinion, some criticisms may be directed at Weber’s ideas and

methodology. In approximating social reality, to what extent is the ‘ideal-type’

that provides a frame of reference reliable? In a case where the ‘ideal-type’

happens to be unreliable, is the whole project still reliable? If we change the ‘ideal-

type’, will we not reach completely different conclusions as to the role of religion

and its discourses? How can we assess the extent to which it is reliable to study

any religion in comparison with Calvinist society as the ‘ideal-type’ society? Is the

presupposition that the model of Calvinist society may be applicable to study

other religions acceptable? What will happen with our studies if we ignore this

Weberian idea and choose to use a different religious society to be our model for

the purpose of comparison? Is such comparison the best technique to achieve

understanding? Furthermore, can we as interpreters really imaginatively

empathise with the actual actions of the interpreted? When an interpreter

assumes that his/her empathetic skills are sufficient to fully understand ‘the

interpreted’, does he/she not overstate his/her abilities? Last but not least,

although Weber argues that his hypothesis is not applicable to explaining any

society that lacks a feature of ‘rational capitalism’, it is difficult to establish

objectively if a given society is ‘rational capitalistic’ or not. The vagueness of the

phrase, ‘rational capitalism’ can lead to several different interpretations.

Sociological writings in Buddhist studies from 1960s (Bechert,

Evers and Obeyesekere)

In the 1960s, three influential authors—Bechert, Evers and Obeyesekere—

produced pioneering works on Theravada Buddhist societies in English and

German languages by instilling western theory and/or Weber’s sociology into their

studies. While Obeyesekere, whose works will be considered later, focused

specifically in his studies on Buddhism in Sri Lanka, Bechert and Evers applied a

sociological perspective to the study of Buddhism in South and Southeast Asia

more generally. The key works of Bechert and Evers are: Bechert’s three volume

Buddhismus, Staat und Gesellschaft in den La¨ndern des Theravada Buddhismus

(1966, 1967, 1973); and Evers’ three consecutive works ‘The Formation of a Social

Class Structure: Urbanization, Bureaucratization and Social Mobility in Thailand’

(1966); ‘The Buddhist Sangha in Ceylon and Thailand. A Comparative Study of

Formal Organisations in Two Non-Industrial Societies’ (1968), and Loosely

Structured Social Systems, Thailand in Comparative Perspective (1969).

INFLUENCE OF WEBER’S SOCIOLOGY ON THERAVADA STUDIES

13

Evers categorises Buddhist studies within the field of Asian studies, and his

writings during the 1960s and 1970s owe a great deal to Weber’s hypothesis. In

contrast, Bechert regards Buddhist studies as a specific area of studies, separate

from Asian studies and from the study of Indian religions. In addition to using

Weber, Bechert also employs Marx, as appropriate to the particular aspect of

Buddhist societies on which his study focuses. Unlike Bechert and Evers,

Obeyesekere seeks to study Buddhism more locally in South Asia in the context of

Indian religions and culture. Methodologically, Obeyesekere brings together

Weber’s sociology and other theories (Durkheim, Freud, Hegel, etc.) in his studies

(as will be shown later). While Bechert (1966 – 73) and Evers (1966 – 69) obtain most

of their information from western documents, Obeyesekere bases his works more

on anthropological fieldwork. A more focused area of studies and Obeyesekere’s

greater proficiency in sociological theory enable Obeyesekere to study Buddhist

societies in greater depth and from a greater number of perspectives. This allows

him to provide an account of both socio-polity and ‘personality and culture’ in

South Asian Buddhist societies, a point to which I shall return below.

When focusing more on socio-political dimensions of Buddhism, Bechert’s

(1966, 1967, 1973) use of Marx’s ideas leads him to argue that modern Buddhism

provides a basis for political operations. This is why Evers comments in his review

of Bechert’s 1966 work that Bechert is overly concerned with ‘political doctrines,

like Marxism, socialism, democracy, nationalism and social-revolutionary ideas’

(Evers, 1967).

Elsewhere, drawing more on Weberian theory concerning the relationship

between socio-economic change and Buddhist societies, Bechert produces the

following works that focus more on socio-economic-political dimensions of

Buddhism: ‘Theravada Buddhist Sangha: Some General Observations on Historical

and Political Factors in its Development’ (1970), ‘Einige Fragen der Religionsso-

ziologie und Struktur des su¨dasiatischen Buddhismus’ (1968),

19

‘Buddhism and

Society’ (1979), and ‘Max Weber and the Sociology of Buddhism’ (1991). Under

Weber’s influence (1930, 1958), Bechert (1970) focuses on reform Buddhism and

changes in social structure and economic interests, and Bechert (1968) uses

Weber’s concepts of Buddhist historical writing and his ideas of the use of

Buddhism as a means of ‘domestication of the masses’.

20

Overall, Bechert in his

writings from the 1970s to 1991 argues that: changes in social and political

dimensions result in religious changes; in turn, social, political and religious

changes bring about economic changes;

21

and Asoka provides the ideal concepts

of kingship in Buddhist societies.

22

This last point means that the ruler is

responsible for protecting and preserving the Sangha and Buddhism. In return,

Buddhism is used as a means to exert political power over the country. The Sangha

is therefore politically significant.

23

While Bechert began to use Weber in the 1960s, it was not until 1991 that he

first attempted to explain why and to what extent Weber’s ideas were applicable

to a study of Buddhist societies. He challenges Weber’s ideas of the apolitical and

irrational (traditional) economic nature of Buddhism and argues (against Weber’s

14

PHIBUL CHOOMPOLPAISAL

own view, mentioned above) for the applicability of those ideas of Weber derived

from his study of Calvinism (Weber, 1930, 1958) to Buddhist societies. Bechert

argues that Weber’s main sources on Buddhism from the 1880s to the 1890s are

outdated, contain factual errors and do not accurately portray the nature of

Buddhism.

24

He argues that Weber was overly concerned with the spiritual and

traditional dimension of primitive Buddhism and lacked the considerations of

Buddhist teachings in ‘rationally economic terms’ (Bechert, 1991, 193). Bechert

(1991, 193) also argues for the inseparable connection between Buddhism and

rational economic factors and between Buddhism and socio-politics. Although

Bechert’s argument is very reasonable, he still has not provided enough evidence

to show how and in which way Buddhism can become ‘rational economic’ like

Calvinism. The fact that Weber’s (1958) information is outdated does not

necessarily mean that Buddhist societies can become ‘rational capitalistic’.

Evers takes a different position in his three consecutive works mentioned

above (Evers, 1966, 1968, 1969) and his Monks, Priests and Peasants: A Study of

Buddhism and Social Structures in Central Ceylon (Evers, 1972). He combines

approaching Buddhist societies sociologically through Weberian views (Weber,

1930) with the use of statistics and documents in English. In reviewing sociology

developed in relation to other continents that have been applied to Southeast

Asia, Ever writes ‘the theories of the great German sociologist Max Weber were

used to explain social and religious change in Southeast Asia’ (1980, 6). Evers

draws upon Weber’s work because he feels he ‘needs a theoretical foundation,

independent of the nature of later interpretation’ (Evers, 1968, 20). All of his works

(1966 – 1972) reflect that Evers maintains the same methodological and theoretical

stance.

25

For example, while Evers (1966) looks at the social, political and

economical processes of urbanisation in Thailand, Evers (1968) explores

comparatively the social structures of Buddhism in Ceylon and Thailand.

Employing the same Weberian view, both works (Evers, 1966, 1968) come to the

similar conclusion that:

the more formalized and strict the structure of a society, the less formalized and

strict is the structure of formal organizations, whose organizational goals are

compatible with the norms and values of that society. (Evers, 1968, 32; cf. Evers,

1966, 488)

Evers is both directly and indirectly influenced by Weber’s ideas. As a result

of Weber’s direct influence, all of Evers’ works look at the comparative social

structures of oriental societies through Weber’s views (1930) of: ‘rationality of

organizations’ (for instance, see Evers, 1968, 33 – 35) and the ‘ideal type of

bureaucracy’ (Evers, 1968, 33). Evers is occasionally indirectly indebted to Weber’s

ideas through Parsons (1960), another follower of Weber. Parsons’ influence leads

to Evers’ argument that ‘the Sangha is, therefore, also predominantly a pattern-

maintenance organization whose function is mainly expressive’ (Evers, 1968, 23).

Through the use of Weber’s theories in conjunction with other sociological

theories, Obeyesekere’s works from the 1960s to 1970s deal with a wider range

INFLUENCE OF WEBER’S SOCIOLOGY ON THERAVADA STUDIES

15

of themes than Bechert and Evers, ranging from socio-economic – political,

societal, and psychological, through to paradoxically conceptual and behavioural

dimensions of Buddhism. In his paper on ‘The Great Tradition and the Little

Tradition in the Perspective of Sinhalese Buddhism’ (Obeyesekere 1963),

26

Obeyesekere explains the psychological function of Buddhism in Sri Lanka using

Weber’s concepts. This allows him to draw a dividing line between ‘the great

tradition’ (or ‘Theravada Buddhism’) and ‘the little tradition’ (or ‘Sinhalese

Buddhism’). Drawing on the terminology and interpretations of Redfield and

Slater,

27

Obeyesekere explains that belonging to ‘the Great tradition’ (Theravada

Buddhism), religious ‘virtuosos’ seriously aim at salvation and thereby claim a

logical rejection of the gods (1963, 150 – 151). Weber’s idea of the ‘motivational’

function of religion informs Obeyesekere’s argument that Buddhism has a

psychologically motivational function that benefits most Sinhalese Buddhists who

belong to ‘the little tradition’. That is why most Sinhalese Buddhists who are more

interested in worldly benefits in this or subsequent lifetimes than in the ultimate

soteriological goals of Buddhism believe in the power of the deities.

As Obeyesekere explicitly states:

The motivational explanation (as explained by Weber) would state why beliefs

that seem contradictory continue to be believed in: there is a strong human

need for these beliefs. For example, however much doctrinal Buddhism devalues

magic and the gods and divests them of power, universal human motives

require the existence of these phenomena. (Obeyesekere 1963, 150)

In his paper on ‘Theodicy, Sin and Salvation in a Sociology of Buddhism’,

Obeyesekere (1968) explores the behavioural and doctrinal concepts of Buddhism

through Weberian and Hegelian theories. Influenced by Hegel’s views of

‘dialectic’,

28

Obeyesekere uses a ‘deduction’ method to show the self-

contradictory nature of Buddhist teachings and practice. Here, Weber’s ideas

(1930)

29

help Obeyesekere formulate an argument as to the function of religion in

the context of ‘social actions’. Obeyesekere argues that, as in Christianity, in

Buddhism ‘suffering is treated as a “given” . . . it is endemic to social life’ (1968, 7).

Following Parsons—whose ideas are influenced by Weber (1930)—Obeyesekere

explains the ‘dialectic’ of Buddhism that in social life ‘there is often a discrepancy

between hope and experience, fact and wish, utopia and actuality . . . The

frustrations (suffering) . . . require alleviation through symbolic techniques (of

religion)’ (1968, 7).

In his paper ‘Religious Symbolism and Political Change in Ceylon’,

30

Obeyesekere (1970) brings together: Weber’s (1930) socio-political ideas; Warner’s

(1959, 1961) idea of ‘social space’;

31

and Durkheim’s (1915) sociological ideas.

32

In it, he aims at ‘studying the changes that have occurred in Buddhism as a result

of massive social changes, especially political changes in recent times’ with an

emphasis on ‘the urban and the city context’ (Obeyesekere 1970, 59). Following

Weber’s hypothesis, Obeyesekere argues that socio-economic – political changes

in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) brought about religious changes and the changing beliefs

16

PHIBUL CHOOMPOLPAISAL

of Sinhalese Buddhists.

33

On the one hand, Obeyesekere uses information about

political changes and the emerging middle class from Wriggins’ (1960) Ceylon:

Dilemmas of a new Nation and Singer’s (1964) The Emerging Elite to support his

Weberian argument. On the other hand, Obeyesekere supports Weber’s ideas by

taking a ‘phenomenological’ approach.

34

The latter is achieved by ‘driving a car

along and around the city of Colombo’ and reflecting on the social and cultural

changes of the Ceylonese through the ‘spatial shifts’ of symbolic/social objects

(Obeyesekere 1970, 59 – 66). Central to the idea of ‘social space’ is his argument

that the symbolic/social objects with their ‘spatial meanings’ in the public place

can represent and reflect the meanings of the social, cultural and religious lives of

the people. This ‘spatial representation’ helps explain socio-political and religious

changes in Ceylon, and helps Obeyesekere to communicate Weber’s ideas in a

descriptive, easy-to-understand way. Obeyesekere’s reflections on the ‘spatial

meanings’ of symbolic objects, as well as other evidence, lead to his Weberian

argument that, due to a cultural shift, a new model of contemporary Buddhism

can be called ‘Protestant Buddhism’ because: through ‘rationalization’, ‘many of its

norms and organizational forms are historical derivatives from Protestant

Christianity’; and it is ‘a protest against Christianity and its associated Western

political dominance prior to independence’ (Obeyesekere 1970, 59 – 63).

In his paper on ‘Personal Identity and Cultural Crisis. The Case of Anagarika

Dhammapala of Sri Lanka’, Obeyesekere (1976) again adopts Weber’s (1930) ideas

to explore through psychological, individual-behavioural and socio-political

dimensions the influence of a charismatic leader’s actions and role upon society.

As in his earlier work (1970), Obeyesekere is explicit that:

The interpretation and frame of analysis are influenced strongly by Erik Erikson

and Max Weber. I [Obeyesekere] have in a sense attempted to relate Erikson’s

psychological orientation to Weber’s sociological one. (1976, 250, note 3)

This leads to Obeyesekere’s conclusion that:

The role, and the individual playing it, could only have been effective at a

certain juncture in history . . . A charismatic leader’s influence on the group

makes sense only . . . [when] the groups wants to be influenced. (1976,

249 – 250)

In other words, in a specific event, social circumstances result in the eruption of a

charismatic leader, whose actions and ideas in turn lead to social changes.

While we can see Weber’s influence on several of Obeyesekere’s works as

discussed in relation to some of his other writings above, Obeyesekere prefers to

draw on the ideas of Freud and Durkheim to deal in more depth with the

psychological theme of ‘personality and culture’ (through ritual, myth, personal

symbols and culture). Works that use this approach include Obeyesekere’s

Medusa’s Hair: An Essay on Personal Symbols and Religious Experience (1981),

The Cult of the Goddess Pattini (1984), and ‘The Ritual Drama of the Sanni Demons’

(1969).

INFLUENCE OF WEBER’S SOCIOLOGY ON THERAVADA STUDIES

17

The way in which Obeyesekere draws on Freud and Durkheim is explained

in his The Work of Culture. Symbolic Transformation in Psychoanalysis and

Anthropology (1982).

35

Obeyesekere accepts that he is influenced by Freud’s ideas

through Jacob and Spiro,

36

and by Durkheim’s ideas through Leach.

37

In favour of

Freud, he argues that ‘the minds of the people’ create and recreate ‘symbolic

forms’ (Obeyesekere 1990, xix). In other words, ‘the unconscious’ (or ‘the deep

motivation’) creates and recreates ‘the public’ (or ‘the culture’). Aligning himself

with the social anthropologists Spiro and Leach,

38

Obeyesekere argues that ‘belief

is central to the authenticity of the experience, as it is to the public legitimation of

that experience’. In other words, because ‘one shares the experiences (and beliefs)

with others’, ‘true beliefs’ are public and shared by the community. For

Obeyesekere, in expressing solidarity, ‘the collective representations’ including the

‘performance’, ritual and other forms of religious congregation (as an act of

‘externalization’) function to allow ‘the individual to view what is within himself as

a cosmic drama’ (1990, 26 – 27).

Overall, Obeyesekere’s investigation into both the personal and social lives

of the people helps provide a more thorough multi-dimensional understanding of

Buddhist societies. Obeyesekere’s pioneering works (1960s – 1970s) have

influenced subsequent authors by providing conceptual ideas of how to study

Buddhist societies and lives of the people, and by providing necessary information

for further investigation into Buddhist studies in South Asia. Gombrich’s works

from 1970s onwards, which I shall discuss in more detail below, are not only

influenced by Obeyesekere’s ideas and information, they are also created in a

similar vein to Obeyesekere’s works. We can find many similarities and links

between Obeyesekere’s (1970, 1976) papers and Gombrich’s (1988; Gombrich and

Obeyesekere 1988) works—the most notable being that: Gombrich and

Obeyesekere share their interests in studying ‘religious changes’ and their

interactions with socio-economic changes in the urban context; influenced by

Obeyesekere (1970), Gombrich (1988; Gombrich and Obeyesekere 1988) uses the

term ‘Protestant Buddhism’, and in using this term Gombrich studies Buddhism in

a way similar to how ‘Protestant Christianity’ has been studied; and Obeyesekere

(1970) provides useful information for Gombrich (1988; Gombrich and

Obeyesekere 1988).

Considering the works of Obeyesekere, Bechert and Evers together, these

writings reflect that there are at least three possible sociological ways of how to

explore the umbrella theme of ‘Buddhism, State and Society’ used during this

period: namely, by studying various dimensions of Buddhist society in-depth

through Weber’s worldviews; by employing other theories to help formulate the

main ideas and use Weber’s ideas as a subsidiary hypothesis, or vice versa; and by

employing other theories without Weber’s ideas. Using these three means,

authors can deal with ‘Religion and Society’ multi-dimensionally, looking at, for

example, socio-political – economic (Weber and Marx), internally mystical and/or

externally ritualistic (Weber and Durkheim), psychological and behavioural (Weber

and Freud), and phenomenological (Weber and phenomenological) aspects.

18

PHIBUL CHOOMPOLPAISAL

Theravada Studies since the 1970s with special reference to Sri

Lanka: the writings of Gombrich, Obeyesekere and Bond

In the 1970s, western writings on Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia showed a

new tendency that sought to employ sociological theories in exploring the socio-

political aspect of Buddhism in the modern context. Three well-known examples

of this tendency, which continue as popular resources to this day, are Gombrich

(1971), Tambiah (1976) and Spiro (1971). During this period each of these authors

broke new ground by publishing works under the main theme of ‘Buddhism and

Society’ in three different Theravadin countries: Sri Lanka, Thailand and Burma,

respectively. These pioneering works are: Gombrich’s Buddhism. Precept and

Practice: Traditional Buddhism in the Rural highlands of Ceylon (1971); Tambiah’s

studies on Thai Buddhism in ‘Buddhism and This Worldly Activity’ (1973) and

World Conqueror and World Renouncer: A Study of Buddhism and Polity in Thailand

against a Historical Background (1976); and Spiro’s Buddhism and Society: a Great

Tradition and Its Burmese Vicissitudes (1971).

Behind the creation of these three works lies the fusing together of different

areas of academic expertise with the use of Weber’s sociological ideas and other

western theory. In Gombrich (1971), Gombrich—with a background in both

Indology (and so the study of Pali texts) and anthropology—approaches his study

of Buddhism in Sri Lanka through the use of the philosopher Karl Popper’s

scientific ideas of ‘the rationality principle’ and Weber’s sociological ideas.

39

For

Gombrich, ‘the rationality principle’ as ‘the basic assumption of the social sciences’

is required to understand Buddhist society (1971, 14). Following Weber, Gombrich

argues that ‘people often really do things—perform ceremonies etc.—because of

what they believe to be the case’ (1971, 11 – 12), and that ‘“charismatic” individuals

and individual actions bring about many (religious and social) changes’ (1971, 13).

In his work on Burmese Buddhism, because of his position as a sociologist, Spiro’s

main argument portrays Durkheim’s idea that ‘religious ideas deal with the very

guts of life’ (Spiro, 1971, 6).

40

He brings together the ideas of Durkheim, Freud and

Weber.

41

While Tambiah (1973, 1), on Thai Buddhism, argues following Weber that

there exists ‘the relation between kinds of religious ethic and economic (and

political) activity’.

In the broader context of Buddhist studies in Europe, not only English-

language authors, but also—according to Gabaude’s (2000) paper ‘Buddhist

Studies in France, Belgium and Switzerland 1971 – 1997’—other western authors

(such as Gabaude, Bizot and Fussman) writing in French and German sought to

employ sociological and/or ethnographic methods in their Buddhist studies.

According to Gabaude, the writings of Buddhist studies in the West have become

the construction of a westernised reading of the East while native worldviews

have been overlooked. This can be clearly seen, as Gabaude points out, from the

fact that: firstly, the academic pattern of Buddhist studies in the West is similar to

the pattern of how the academic knowledge of Christianity has been constructed;

and secondly, looking at western studies on Buddhism from an outsider’s point

INFLUENCE OF WEBER’S SOCIOLOGY ON THERAVADA STUDIES

19

of view, one sees that western authors are often more concerned with social sides

of Buddhism (social, political, historical and economic aspects of Buddhist

societies) rather than religious sides of Buddhism (the doctrines and real practices

of the real people in society and the mystical/otherworldly life aspects of Buddhist

teachings) (Gabaude, 2000, 229 – 234). By looking at the works of Lamotte, Bareau,

Fussman and Bizot, Gabaude recapitulates four main ways of approaching

Buddhist studies as practised by French speaking scholars. The four approaches

are to study: textual context (Lamotte), social context (Bareau), historical context

(Fussman) and ritual context (Bizot) (Gabaude, 2000, 233 – 236). Gabaude then

argues that there has been a tendency for academics to study Buddhism from the

sociological, anthropological and historical worldview of ‘outsiders’. Gabaude

concludes that:

In France, (all the institutions) with the exception of the E´cole Pratique des

Hautes E´tudes School, the teaching and research about Buddhism was scattered

according to other disciplines: anthropology, history, sociology . . . They may

have never studied Buddhism in terms of its doctrines. They pretend to study

Buddhism ‘as it is here and now’ while, for them, philologists study Buddhism ‘as

it is nowhere’ . . . Buddhism is just a part of social life. (2000, 235 – 236)

I will now look at the influence of Weber’s sociology on Buddhist studies in

Sri Lanka in the 1970s and 1980s by reviewing the most influential works of

Gombrich (1971, 1988), Gombrich and Obeyesekere (1988), and Bond (1988).

In his 1971 and 1988 studies, Gombrich deals with the question of ‘religious

changes’ in Buddhist societies on both individual-behavioural and societal levels

through anthropological, textual, doctrinal, historical and sociological approaches.

While Gombrich (1971) focuses on an interpretation of people’s behavioural

beliefs and practice in a traditional Theravadin society, Gombrich (1988) provides

the broader context of the social history of (Theravada) Buddhism. Both works

focus on ‘religious changes’ because, Gombrich believes, to understand the

religion we need to study Buddhism from the past to the present in order to be

able to ‘speculate on the causes (of religious changes)’ (1971, 14). Doing this,

Gombrich studies the origins of Buddhism from historical and textual evidence,

but studies the present through the anthropological fieldwork-based methods.

On an individual-behavioural level, following Tylor and Weber, Gombrich

(1971, 13) argues that (changing) beliefs lead to (changing) practice, or in his

words, that ‘people often really do things—perform ceremonies . . . —because of

what they believe to be the case’. In this behavioural and psychological context,

Gombrich moves beyond Weber’s sociology to explain that there are distinctions

between ‘cognitive (or conscious) behaviour’, or ‘what they really believe and say

they do’, and ‘affective (or unconscious) behavior’, or ‘what they really believe and

really do’ (Gombrich, 1971, 5). However, on a societal level, Gombrich (1988)

argues following Popper and Weber that it is the social context that influences

people’s actions and beliefs. On the whole, Gombrich’s Popper – Weberian analysis

is persuasive because he is able to draw on a wealth of primary sources to support

20

PHIBUL CHOOMPOLPAISAL

his arguments. The following are Gombrich’s assumptions, which will illustrate

how Gombrich is influenced by Weber and Popper:

(1)

In explaining how to study religion, Gombrich follows Popper’s ‘method of

conjecture and refutation’, and so conducts his analysis by formulating a

hypothesis and testing it. If a hypothesis is falsified by any evidence, a new

hypothesis has to be formulated. If a hypothesis can correctly explain information

as obtained, it becomes ‘the (social) truth’ (Gombrich, 1971, 3). In both works

(1971, 1988), Gombrich explains the concepts of ‘religious changes’ and

‘unintended consequences’ in the first chapter. These concepts seem to serve as

his ‘hypothesis’, which is then tested through the subsequent chapters.

(2)

In presenting his understanding of what regulates an individual’s action,

Gombrich follows Popper’s concept of ‘the rationality principle’ and believes

that an ‘action (is) based on the beliefs and directed to the aims’.

42

(3)

Introducing the concept of ‘charismatic leadership’, a charismatic leader’s

actions in relation to social changes, Gombrich draws again on Weber to argue

that a charismatic leader’s actions ‘bring about many (social) changes’ (1971, 15).

He adds that these ‘social changes come about as the unintended or the

intended consequences of the actions and utterances of individuals’. This leads

to the following assumptions (itemised as (4) and (5)).

(4)

In presenting his understanding of what regulates social actions, or behaviour of

human collectivities, Gombrich studies ‘social changes’ in Buddhism by weaving

together Weber’s ideas in (3), with Popper’s strategy of ‘problem situation’,

Popper’s principle of ‘methodological individualism’ and Popper’s concept of

‘unintended consequences’. As Gombrich argues, there are always interactions/

communications between an individual person and socio-economic – historical

circumstances through ‘language’. Through these interactions:

4.1.

‘People’s thoughts and actions become largely the product of their

education and social circumstance.’

4.2.

An individual person’s feedback and patterns of ideas in response

to social problems are attempts to offer better viable solutions to

society. A ‘charismatic leader’ is capable of providing ideas that are

accepted by society.

4.3.

Individuals are influenced by the innovative ideas of a ‘charismatic

leader’. This leads to changes in the individuals’ patterns of behaviours,

and in turn it leads to ‘unintended consequences’ (or ‘religious

changes’), which are an historical innovation (Gombrich, 1988, 9– 18).

(5)

Leading on from (4), Gombrich therefore argues that Weber ‘scored one great

success when he showed the historical association of Protestant Puritanism

(chiefly Calvinism) with the rise of capitalism’ (1988, 13). This influences

Gombrich’s arguments in dealing with socio-economic aspects of Buddhism,

particularly in Chapter 7 (‘Protestant Buddhism’) and Chapter 8 (‘Current trend’)

in Gombrich (1988).

INFLUENCE OF WEBER’S SOCIOLOGY ON THERAVADA STUDIES

21

In Chapter 7 (‘Protestant Buddhism’) in Gombrich (1988), the author deals with

Weberian aspects of Buddhism by taking information from Malalgoda (1976),

Bechert (1966, 1967) and Obeyesekere (1970). Gombrich’s use of the phrase,

‘Protestant Buddhism’ indicates a transfer of information and ideas from the above

academics’ works to Gombrich (1988). The phrase ‘Protestant Buddhism’ reflects

Weber’s influence on Obeyesekere (1970), Malalgoda (1976), Gombrich (1988), and

Gombrich and Obeysekere (1988). The phrase also portrays some of the perceived

new features of Buddhism in response to modernity, as reflected and agreed by

most contemporary authors. These features, which shed light on the socio-

political interactions between Buddhism and politics, are what Bechert collectively

terms ‘buddhistische Modernismus’ (or ‘Buddhist modernism’).

43

Obeyesekere’s

phrase ‘Protestant Buddhism’ appears to be a virtual synonym of this. Although

the use of these two phrases is very close in application to each other, their

meanings paint two different pictures of the study of Buddhist societies. While

Buddhist modernism is a broader term that encapsulates modern developments

in oriental societies, and consequently their forms of Buddhism, as influenced by a

modernity that originated in the West, the term Protestant Buddhism is very

specific in that it attributes a great role to direct western influence and especially

to Christianity in transforming Buddhism in the East.

Two other publications on Buddhism in Sri Lanka contemporaneous with

Gombrich (1998) similarly reflect the influence of Weber’s sociological ideas:

Gombrich and Obeyesekere’s (1988) Buddhism Transformed. Religious Change in Sri

Lanka; and Bond’s (1988) The Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: Religious Tradition,

Reinterpretation and Response. Under Weber’s influence, the three works share the

following features:

(1)

Gombrich (1988), Gombrich and Obeyesekere (1988) and Bond (1988) are

interested in the question of what Bellah (1965) calls ‘religion and progress’, or

‘Buddhist identity’ and ‘religious changes’.

44

Here, while Gombrich (1988) and

Gombrich and Obeyesekere (1988) are directly influenced by Weber, Bond

(1988) is indirectly influenced by Weber (1930) through Bellah (1965).

(2)

Unlike Bechert (1966, 1967) and Evers (1960s – 1970s), these writings examine

the place of Buddhism in the contemporary world by placing recent religious

and socio-economic – political changes in the context of the modern religious

history of South Asia. Like Tambiah (1976), Gombrich and Bond are ambitious to

cover a long period of history.

45

However—unlike Tambiah (1976)—Gombrich

(1988), Gombrich and Obeyesekere (1988) and Bond (1988) focus on modern

history in looking at Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

(3)

Influenced by Weber’s (1930) ideas, they argue that western influence,

modernisation and Protestant Christianity have led to the emergence of

‘Protestant Buddhism’ with its ‘rational’ features. ‘Protestant Buddhism’, for

Gombrich, Obeyesekere and Bond, lies in its double meanings:

3.1.

Protestant Buddhism is a protest against British colonialism and

Protestant Christianity. As the three authors argue, Sinhalese

22

PHIBUL CHOOMPOLPAISAL

Buddhists believe it is everyone’s responsibility to preserve and fight

for the survival of Buddhism. This results in the blurred distinction

between the monastic role and the role of the laity in leading

religious activities.

3.2.

Protestant Buddhism further displays new salient features of

Buddhist society that are similar to those of Calvinist society, as

portrayed by Weber. Such features include the emergence of

‘charismatic leaders’ and the reform of society, the growth of an

urban middle class in Buddhist society, the development of modern

education, an expanding economy, the growth in publication of

Buddhist literatures, and the study of religion through texts.

(4)

These works all present modern Theravada Buddhism as facing religious

‘dilemmas’ (or ‘dialectic,’ reminding us of Hegel’s concept of ‘dialectic’ as

portrayed through Weberian ideas in relation to Buddhism by both Obeyesekere

and Tambiah in Leach (1968)). They see conflict or dialectic between two

fundamentally opposed religious orientations in Buddhism—namely worldly and

other-worldly values; between the logical doctrine of karma in the Pali canon as

opposed to the devotional and/or magical beliefs and practices of the masses.

Despite the above similarities, Gombrich (1988) and Bond (1988) provide two

different interpretations of the characteristics of religious changes in Sri Lanka.

This is due to Bond (1988) being strongly influenced by Bellah (1965). While

Gombrich and Obeyesekere (1988) argue that religious changes have caused

‘confusion and discontinuity’ between the traditional and the present forms of

Buddhism,

46

Bond (1988), like Bellah (1965), sees such changes, which become the

reinterpretations and revival of Buddhism, as being ‘continuous’ and progressive

rather than disruptions. Examining the role of the laity, Gombrich and

Obeyesekere (1988) regard the rise of the social uplift movement Sarvodaya

and the practice of meditation led by the laity as distortions of the traditional

Buddhist ideals. However, Bond (1988), while agreeing that these developments

are new, argues that these two practices show the progressive and adaptable

characteristics of modern Buddhism because their reinterpretation of Buddhist

teachings helps people cope with the stress of modernity.

Furthermore, since Gombrich (1988) and Bond (1988) make use of different

terminologies (taken from different sources), they portray similar patterns of

religio-socio – political changes in Sri Lanka differently. While Gombrich (1988)

terms perceived developments in Buddhism with three phrases (‘spirit religion’,

‘Protestant Buddhism’ and ‘Post-Protestant Buddhism’), Bond (1988) categorises

religious changes into two types (‘reformism’ and ‘neo-traditionalism’), again

following Bellah. According to Gombrich and Obeyesekere (1988), ‘spirit religion’,

which is based on traditional practices of devotion and animism, emphasises the

different religion appropriate to the laity and the Sangha, the latter being

detached from spirit religion. In contrast, ‘Protestant Buddhism’ (or ‘Buddhism

proper’) with its ‘rationality’ in the Weberian (1930) sense, in providing a new set

INFLUENCE OF WEBER’S SOCIOLOGY ON THERAVADA STUDIES

23

of values for the urban middle-class in the modern context, undermines the

difference between the laity and the Sangha.

Gombrich and Obeyesekere (1988, 14) argue that ‘Protestant Buddhism’

develops out of the modern ‘rational’ socio-cultural context, and that this

development eventually brings ‘confusion’ to the minds of many ‘irrational’

people from a traditional background.

47

This leads the co-authors to adopt

another of Weber’s terms, ‘remystification’. They argue that in ‘remystifying’ a

society, the uneducated and socially/economically uncomfortable find the new

‘rationality’ of the socio-cultural context incompatible and so withdraw from or

evade society by practising meditation or devotion. In addition, through the same

‘remystification’ process, the middle classes with their ‘rational’ minds attempt to

live in this world, while following the logical doctrines of karma and practising

meditation.

48

On some occasions, the co-authors find Weber’s ideas alone are insufficient

to explain the psychological – behavioural aspects of Buddhism. They therefore

borrow ideas and terminology from other scholars to help explain on a more

psychological level practitioners’ experience of religious changes. Explaining the

relationship between meditation and possession, Gombrich (1988) adopts Lewis’

ideas

49

and Eliade’s terms (‘ecstasy’ and ‘enstasis’) in conjunction with Weber’s

ideas to help explain the practitioners’ experience. This is why Gombrich explains

that, because of the irrational minds of the uneducated, they evade social life and

practise meditation in ‘ecstatic’ emotion. In contrast, because the middle class can

possess a heightened awareness of their own experience, they can perform a

meditation practice in ‘enstasis’ (1988, 14 – 15, 452 – 454).

50

In contrast, as previously noted, Bond (1988) is influenced by Weber’s (1930)

ideas mainly through Bellah (1965) and partially through Tambiah (1976). Tambiah

(1976) enables Bond to argue for the applicability of Weber’s socio-political ideas

in Buddhist studies. In portraying social, political, economical and religious aspects

of Buddhism (Bond, 1988, 11 – 21), Bond (like Tambiah and Bechert) argues that

‘Weber undoubtedly overstated the extent to which early Buddhism was limited

to ascetics’ who ‘sought the true goal of religion’ (1988, 23). Bond’s adoption of

Weber’s (1930) ideas then allow him to support Bellah’s ideas, which in turn lead to

Bond’s portrayal of ‘the Dhamma for social action’, or the dialectic relationship

between ‘social context’ and ‘cosmologies’ (in Chapter 7). Bellah’s influence on

Bond (1988) is so substantial that most of Bond’s core arguments and ideas

depend on Bellah. To understand Bellah’s influence on Bond (1988), I will now

briefly look at Bellah’s ideas and position.

Like Obeyesekere and Gombrich later, Bellah regards ‘identity’, ‘continuity’

and ‘changes’ (or ‘religion’ and ‘progress’) as being central to the survival and

development of all religion through its history.

51

Drawing on Eliade’s explanation

of ‘spatio-temporal identity’, Bellah explains that the identity of each religion can

only be specified according to its own local and historical context (i.e. in a

particular area and at a specific time) (Bellah, 1965, 174 – 175). Influenced by

the ideas of Weber and of Geertz (1964), Bellah explains that ‘evolution’

24

PHIBUL CHOOMPOLPAISAL

is ‘the rationalization of religious symbolism’ (1965, 176 – 177). Through evolution,

Buddhism has ‘progressed’ from being ‘primitive’ to being ‘traditional’ (or

‘historic’) and then ‘modern’ (Bellah, 1965, 176 – 178). Explaining ‘primitive

societies’, Bellah adopts Durkheim’s idea that ‘religious roles, with few exceptions,

are embedded in the whole society’ (1965, 177). In contrast, in explaining ‘historic’

societies, like Obeyesekere and Gombrich, Bellah argues in favour of Weber (1930)

that ‘historic’ religion ‘provides the possibility of personal thought and action’

(Bellah, 1965, 177). From Bellah’s view, like Calvinistic society in the historic period,

Buddhism in the historic period with its ‘rational’ features is thus seen as

functioning to provide ‘fixed beliefs’ and ‘religious disciplines’, particularly the

doctrines of ethical ‘duty’. For Bellah and Weber, these beliefs psychologically

provide ‘motivation’ for people, and encourage people to work hard. The result is

the ‘progress’ of Buddhism through its history and the accumulation of worldly

benefits in Buddhist society. At the same time, while ‘progressing’ towards the

future, religion has to maintain its own ‘identity’ by ‘returning to the past’, or

going back to the original teachings of Buddhism (Bellah, 1965, 180 – 186).

Bellah follows Weber (1930) to argue that ‘Protestant Christianity’ in the

modern period is ‘undoubtedly the first religious movement to make a significant

contribution to modernization’ (1965, 198). According to Bellah, the ‘modern’

culture of Protestantism is characterised by the culmination of ‘rationalization’ and

the increase of ‘learning capacity in individual personalities’. At this end of

‘rationalization’, Protestantism implicates itself in this worldly society to the extent

that ‘ascetic religious motivation’ has been channelled ‘into economic and

political roles’ and the consequences are ‘the emergence of capitalistic and

democratic institutions’. In this situation, ‘religious obligation has primarily to do

with human welfare’ (Bellah, 1965, 194 – 199). As a response to modernity and

‘Protestant Christianity’, religion has to adapt itself. There are four possible ways to

adapt itself (or ‘four types of responses’): ‘conversion’, ‘reformism’, ‘neo-

traditionalism’ and ‘traditionalism’ (Bellah, 1965, 198 – 215).

The following three main arguments by Bond are the obvious result of the

influence of Bellah’s work (1965) upon his (Bond, 1988):

(1)

Like Bellah, and later Obeyesekere and Gombrich, Bond explains that the

‘progress’ of religion can be understood in terms of ‘identity, continuity and

changes’. Unlike Obeyesekere and Gombrich, Bond following Bellah sees the

progress of Buddhism as being ‘continuous’, or ‘the dynamic of the revitalization

process’ (Bond, 1988, 299). In other words, the history of Buddhism, for Bond, is

‘the living process through which people represented an ancient religious

tradition in modern times’ (1988, 299).

(2)

Like Obeyesekere, Gombrich and Bellah, Bond draws on Weber’s (1930) ideas to

frame his theory that there has been a change from ‘primitive’ to ‘modern’

societies through ‘rationalization’. Moreover, Weber’s ideas enable Bond to

exemplify and reinterpret specific dialectical relations between ‘social context’

and ‘cosmology’ (Bond, 1988, 299).

INFLUENCE OF WEBER’S SOCIOLOGY ON THERAVADA STUDIES

25

(3)

Unlike Obeyesekere and Gombrich, Bond draws on Bellah’s typology to argue

that there have been two patterns of responses of Buddhist society in Sri Lanka

towards modernity: ‘neo-traditionalism’ and ‘reformism’. In chapter two, Bond

explains that reformism has appeared since the mid-eighteenth century

(a reference to the activities and achievements of, in particular, the Sri Lankan

reform monk Saranamkara) and that the lay Buddhist associations (organised by

Olcott and Dharmapala) can be seen as the major vehicle of revival. In Chapters

3 – 7, Bond discusses in great detail the emergence of ‘neo-traditionalism’ and

how it becomes a more viable means to cope with pluralistic modern societies.

To sum up, I have included here, before turning to studies on Thailand, an

overview of the direct and indirect use of Weber in the study of Sri Lankan

Buddhism, not in order to criticise but to show how pervasive it is in studies of the

two Theravada countries most studied by western anthropologists in the postwar

period—most studied because of their relative security and openness.

52

I am

interested to observe that, in spite of the very different histories of these two

countries, and in the relationship between their respective secular authorities and

Sangha, the overall Weberian analyses developed regarding them are strikingly

similar. My own expertise is in Thai Buddhism, to which I now turn, for a more

detailed and analytical exploration of Weber’s influence in Buddhist studies.

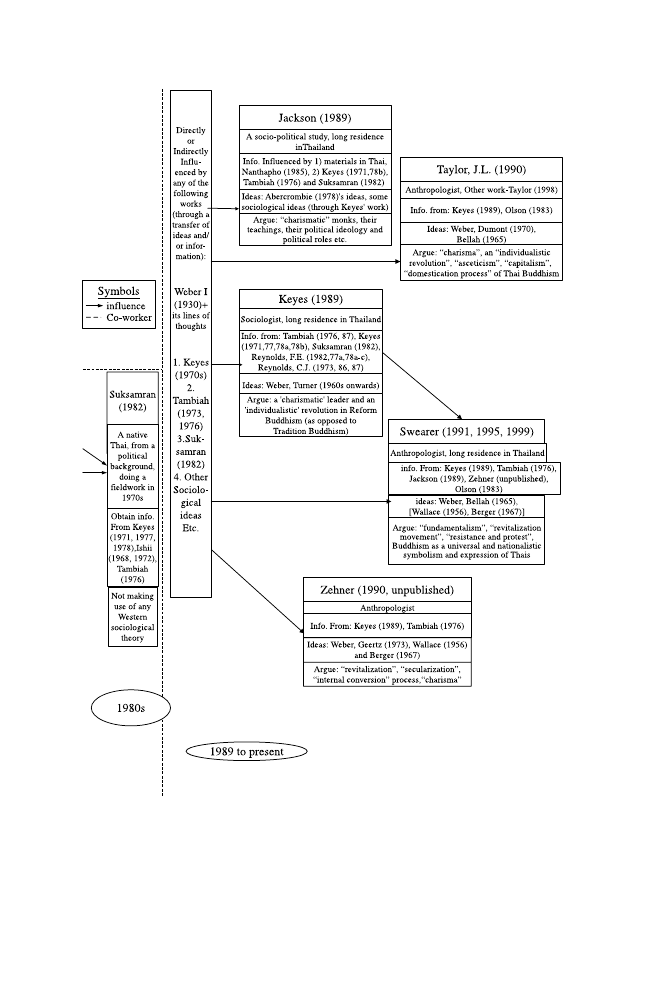

Studies of Thai Buddhism in the West

In the field of Thai Buddhism, Keyes and Tambiah produced their writings in

the 1970s and 1980s under the umbrella theme of ‘Buddhism, State and Society’ by

employing Weber’s (1930) sociological ideas.

53

Written before he became

influenced by Weber, Keyes’ (1971) ‘Buddhism and National Integration in Thailand’

can be seen as a pioneering academic work in the field of Thai Buddhist studies

with its portrayal of the mutual relationship between Buddhism and kingship.

Centring on a socio-political aspect of Buddhism, Keyes (1971, 22–34) portrays the

political ideology that King Rama V uses the Sangha as a means to help create

national unity. On the same theme, Keyes’ (1987) Thailand: Buddhist Kingdom as

Modern Nation-State portrays the formation of Thailand as a modern nation. Some

parts of this latter work are produced under the direct influence of Weber (e.g.

Keyes’ interpretation of the doctrine of karma),

54

while some are under the indirect

influence of Weber through Turner’s ideas (particularly the concept of ‘charismatic

leaders’, political Buddhism and social changes).

55

In this work, Keyes explains the

modernisation process in Thailand through a legitimating ideology based on the

revitalised role of Buddhism and that of monarchy. Keyes depicts, on the one hand,

a mutual interaction between religion and polity creating social unity, and, on the

other hand, a tension behind the fac¸ade of unity. In Keyes’ (1978b) work on

‘Political Crisis and Militant Buddhism in Contemporary Thailand’, Keyes is very

much influenced by Turner’s Weberian ideas in attributing the rise of militant

Buddhism to the political crisis of the 1970s. Using Turner enabled Keyes to develop

26

PHIBUL CHOOMPOLPAISAL

his theory regarding a connection between the emergence of a ‘charismatic leader’,

socio-religious and socio-political changes and religious violence.

Not long before Keyes, Tambiah had similarly followed Weber’s conceptions

of the relationship between religion and secular activities, in producing his

‘Buddhism and This Worldly-Activity’ (1973) and World Conqueror and World

Renouncer (1976). In the former, Tambiah attempts to demonstrate the

applicability to the study of Buddhist societies of Weber’s paradigmatic idea of

the historical development from Protestant ethic to capitalism. Influenced by

Weber’s (1930, 1958) ideas, the latter gives an extensive account of Thai Buddhist

society in comparison with Buddhist societies in Burma, Sri Lanka and early India,

as well as with Brahmanical conceptions of world and societal order. At the outset

of Tambiah’s work (1973, 1), he explicitly accepts that ‘I (Tambiah) am an admirer

of Weber . . . (there exists) the relation between kinds of religious ethic and

economic (and political) activity’. Here, Tambiah establishes that a study of

modern Buddhism in Sri Lanka and Thailand can demonstrate the applicability of

Weber’s paradigmatic ideas of the relationship between religion and socio-polity

to modern oriental societies. Like Bechert, 1991, Tambiah contends that, because

Weber’s sources on Buddhism are outdated, Weber’s conclusion that his

sociological ideas of religious studies are not applicable to a study of the East is

unfounded. Tambiah’s (1973) work begins by exploring Weber’s ideas, and

thereafter argues for the development of Buddhism from ‘Ancient Buddhism’ to

‘semi-transformed Buddhism’ in Asoka’s period and ‘transformed Buddhism’ in the

modern period. Tambiah explains that the socio-politicisation of Asoka’s

Buddhism (as the exemplary Buddhism) initiated the historical transformation of

Buddhism. Consequently, the new tendency of Buddhism, which features the

mutual support between kingship and religion, has proved the applicability of

Weber’s Calvinist-religion model, more specifically an ‘ideal-type’ model of the

relationship between religion and society, to ‘transformed’ Buddhist societies. Like

Bechert, Tambiah argues that, because of the process of colonisation in Sri Lanka

and that of modernisation in Thailand, both Sri Lanka and Thailand have

undergone a process of transformation through which new oriental societies

possess the ‘rational spirit of capitalism’ as did Calvinist society.

Pursuing the same Weberian ideas, Tambiah (1976), like Bond (1988) later,

highlights both the ‘continuities’ of Buddhism in Southeast Asian Buddhist

societies across time and locality, and the ‘tensions’ between religion and polity.

Tambiah proposes that Buddhism includes a conception of proper political action

and structure with ‘kingship as the ordinating principle of the polity cum society’

(1976, 515). Tambiah’s (1976) work is problematic because it uses a single

Weberian theory to deal with a vast array of topics over a very long period of time.

As portrayed in both Tambiah (1973) and (1976), the historical development of

Buddhism and the emergence of modernised Buddhism are very similar to the

historical accounts of Calvinist religion in terms of the mutual interactions and

tensions between religion and socio-polity. Tambiah’s overriding concerns with

Weber’s ideas, coupled with his limited ability in any Thai language, results

INFLUENCE OF WEBER’S SOCIOLOGY ON THERAVADA STUDIES

27

in an absence of Thai materials in his lengthy work. This is problematic because

Tambiah’s overemphasis on a theoretical angle leads him to ignore the practical

dimensions of Thai polity. His work is then slanted heavily towards western theory,

thoughts and materials. His ‘macroscopic . . . panoramic and telescopic view of

the society’ (Tambiah, 1976, 3) reflects a lack of concern for context, here ignoring

how the native society functions in its own socio-cultural context.

There are a few exceptions where Tambiah does not seek to apply Weberian

theory and does seek to pay attention to context. These are his studies focusing

on: the purely doctrinal and cosmological aspects of Buddhism; and the

interweaving of cosmological ideas with village life, a society that in his view can

be regarded as being ‘archaic’ or ‘apolitical’. These exceptions can be seen in

Tambiah’s (1970) Buddhism and the Spirit Cults in North-east Thailand; and in his

analysis of ‘the Brahmanical Theory of Society and Kingship’ (Chapter 2) and ‘Early

Buddhist Concepts of World, Dhamma and Kingship’ (Chapter 3) in Tambiah

(1976). While the themes still derive from the socio-political agenda, we see here

Tambiah’s intention to investigate religious texts and societies through their own

religious context.

Produced not long after these works by Keyes and Tambiah, Suksamran’s

(1982) Buddhism and Politics in Thailand: A Study of Sociopolitical Change and

Political Activism in the Sangha reflects the indirect influence of Weber’s sociology

through Keyes and Tambiah. As a native Thai with a background in political

science, Suksamran, unlike Keyes and Tambiah, does not intend to make use of

any western, let alone Weberian, theory to structure his study. As he says,

‘I [Suksamran] do not fully comprehend the issues in dispute in the sociological

and anthropological theories, for they are largely outside my field of interest’

(Suksamran, 1982, 4). This suggests that, since he does not understand sociological

theories, he is not directly influenced by these theories. Yet, while we might posit a

generalised influence of western thought through his background in political

science, it is Weber who most clearly does enter his work through Keyes and

Tambiah. Influenced by Keyes’ idea of the politicalisation of the Sangha, Suksamran

argues that ‘under certain socio-economic and political circumstances Buddhism

could be manipulated to provide legitimacy for rebellious or revolutionary

ideologies’ (1982, 5). This formulation of the socio-political ideas coupled with

Suksamran’s unrestricted use of materials in Thai enable him to go far deeper than

Keyes and Tambiah in analysing ideologically diverse political monks, both left-

wing and right-wing, in the dramatic changes emerging from 1973.

Unlike most western scholars, rather than focusing on politics and Buddhism

as inevitably set at odds with each other, Suksamran represents Thailand

positively, as having achieved the appropriate balance between politics and

Buddhism, in comparison with the neighbouring Buddhist countries of Southeast

Asia. Nevertheless, it could be argued that Suksamran, being an insider, does not

see potential alternative models outside this context. While Suksamran’s writing

reflects his main focus on the relationship between socio-politics and Thai

Buddhism from the perspective of a native Thai patriot, it fails to take into

28

PHIBUL CHOOMPOLPAISAL

consideration the broader context beyond Thailand: the socio-political changes in

the whole of Southeast Asia, in part reflecting global transformations, and the

effects of these on the changing role of religion; the influence of western

processes of colonialisation and hegemony; and the impact of modernisation and

the introduction of extreme consumerism to Southeast Asia. The above factors

have led to structural changes in politics, economics and religion in the whole of

Southeast Asia. This has also led to the transformation of Buddhism in Thailand

and neighbouring countries. Thailand, although not colonised by either France or

Britain, became a Cold War front, due to its geographical location, resulting in

modernisation and the rapid implementation of capitalism that in turn have

transformed Buddhism.

56

Western academics might question whether it is really

possible to have an ‘ideal/perfect’ balance between religion and politics.

On the whole, the most important influence of Keyes’ and Tambiah’s writings

during the 1970s and 1980s seems to be that they laid the foundation of knowledge

in this field, namely that: throughout the long history of Thailand there has always

been a mutual relationship between kingship/macro-politics and religion; and like

the reform in a Calvinist society, the reform in Thai society and Reform Buddhism (as

opposed to Tradition Buddhism) was politically initiated by King Mongkut. In a

religious sphere, as discussed in Tambiah’s (1976) writing, Buddhadasa’s work

initiates Reform Buddhism in Thailand with its provision of the highly philosophical