AFFECT, RELATIONSHIP SCHEMAS, AND

SOCIAL COGNITION: SELF-INJURING

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER

INPATIENTS

Rachel Whipple

The George Washington University

J. Christopher Fowler

The Austen Riggs Center

Psychiatric patients who engage in nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) present specific

challenges to therapists because they often lack the capacities necessary to under-

stand the social and emotional triggers for their actions. This case-control study

empirically explores psychodynamic concepts of NSSI by examining quality of

affect, object representations, and social cognition manifest in verbatim Thematic

Apperception Test narratives (Murray, 1943). Sixty-five female borderline inpa-

tients engaging in NSSI served as the case group, while 68 matched female

inpatients with BPD without NSSI served as the control group. The TAT transcripts

were rated on the Social Cognition and Object Relations Scale (Hilsenroth, Stein, &

Pinsker, 2007; Westen, 1995), then a priori hypotheses were subjected to statistical

analysis. While both groups functioned in the pathological range on all dimensions,

the NSSI group created narratives reflecting greater expectation of malevolent

treatment from others, expressed interpersonal relationships in more shallow terms

with little capacity for empathy, and had greater difficulty modulating aggressive

feelings. Their narratives also reflected greater difficulty with splitting and boundary

confusion, more primitive relationship schemas, and poorer understanding of social

causality of interpersonal interactions. Results add to a growing body of evidence

that NSSI is associated with more severe forms of BPD pathology, especially in

domains of malevolent object representations, misinterpretation of social interac-

tions, and expressions of hostility (Kernberg, 1984; Simpson & Porter, 1981;

Stolorow & Lachmann, 1980; Yeomans, Hull & Clarkin, 1994). These results

extend observations of the heterogeneity in the severity of patients diagnosed with

BPD.

Keywords: Borderline Personality Disorder, self-injury, affect, social cognition

Rachel Whipple, PsyD, Department of Psychology, The George Washington University; J. Chris-

topher Fowler, The Austen Riggs Center.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to J. Christopher Fowler, The Austen

Riggs Center, 25 Main St., Stockbridge, MA 01262. E-mail: christopher.fowler@austenriggs.net

Psychoanalytic Psychology

© 2011 American Psychological Association

2011, Vol. 28, No. 2, 183–195

0736-9735/11/$12.00

DOI: 10.1037/a0023241

183

Psychiatric patients who engage in nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) such as cutting, burning

or abrading their skin can be quite difficult to treat, in part because the behaviors serve

multiple functions (Nock & Prinstein, 2005), and as a result the behavior is relatively slow

to change over time compared to symptoms and suicide attempts (Bateman & Fonagy,

2008; Doering et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2009). Because borderline patients who engage in

NSSI have great difficulty with affect regulation and interpersonal communication, they

frequently stir intense emotional reactions in those caring for them. It is not uncommon for

therapist to experience great difficulty maintaining a therapeutic stance by being drawn away

from exploration of affective states and cognitions in an attempt to manage behaviors (Plakun,

1994; Fowler, Nolan & Hilsenroth, 2000). The complexities of treatment, the risk factors

associated with this symptom complex, and the rise in prevalence in America’s adolescents

and young adults provided the impetus for the current study.

Currently, the field is inundated with definitions and names for the phenomena under

investigation; however, the most parsimonious and widely accepted term is nonsuicidal

self-injury (NSSI). Nonsuicidal self-injury refers to the direct, deliberate destruction of

body tissue in the absence of lethal intent (Nock & Favazza, 2009; Nock, Wedig, Janis,

& Deliberto, 2008), and includes behaviors such as self-inflicted cutting, burning, or

abrading skin (not substance abuse or generally acceptable tattooing or body piercing).

Studies estimate between 14 and 39% of adolescents, and 35% of college students report

histories of NSSI (Gratz, 2001; Nock & Prinstein, 2005). Prevalence rates are far higher

among inpatients diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), with estimates

ranging from 50% (Dulit, Fyer, Leon, Brodsky, & Frances, 1994), to 90% (Zanarini et al.,

2008).

Prior research suggests early adverse events are risk factors for NSSI including

physical abuse (Gratz, Conrad, & Roemer, 2002; Simpson & Porter, 1981), early sepa-

ration/loss, and unpredictable childhood environments, (Leibenluft, Gardner, & Cowdry,

1987), and interruption in the attachment process (Simpson & Porter, 1981; Bach-Y-Rita,

1974). Researchers employing interview and self-report measures assessing current per-

sonality functioning report excessive hypervigilance, resentful attitudes, and paranoid

reactions in social and intimate relationships (Yeomans, Hull & Clarkin, 1994), as well as

greater verbal and physical aggressiveness than in other psychiatric patients (Hillbrand,

Krystal, Sharpe, & Foster, 1994; Simeon et al., 1992). This may be related to underlying

deficits in verbal and nonverbal communications skills— BPD patients engaging in NSSI

demonstrate poorer nonverbal communication skills, and have more difficulty communi-

cating and interpreting emotional information than those with BPD without NSSI

(McKay, Gavigan, & Kulchycky, 2004). The intensity and frequency of NSSI is associ-

ated with greater impulsivity, chronic anger, and somatic anxiety, while NSSI and Axis II

comorbidity is associated with greater dysphoric affect, anxiety, anger, rejection sensi-

tivity, and emptiness (Simeon et al., 1992). Borderline patients who engage in NSSI also

suffer from higher rates of de-realization and drug-free hallucinations/delusions (Soloff,

Lis, Kelly, Cornelius, & Ulrich, 1994).

While self-report and interview based studies provide crucial evidence of global

impairment, the study of NSSI is complicated by the fact that more psychologically

impaired patients who engage in the behavior may be reticent to disclose information, or

lack the basic capacity to recognize or express thoughts and emotions that precipitate an

urge to damage their bodies. Thus, relying solely on self-report or interview methods to

understand psychological vulnerabilities associated with NSSI is particularly problematic.

Some research teams circumvent problems associated with self-report bias by applying

184

WHIPPLE AND FOWLER

performance-based methods to assess implicit psychological processes (Baity et al., 2009;

Fowler et al., 2000; Nock, & Banaji, 2007).

In light of the broad-based impairments in affect regulation, interpersonal, and

cognitive domains associated with NSSI (especially in those with comorbid BPD), we

hypothesized that underlying dimensions of social cognition and object relations represent

specific vulnerabilities to NSSI, and could best be assessed using implicit measures of

object-relations and social cognition. We chose the Thematic Apperception Test (Murray,

1943) because it represents a narrative-based implicit measure of personality functioning

that allowed us to explore quality of affect, relationship schemas, and social cognition

imbedded in narrated stories of interpersonal interactions. Applying the Social Cognition

and Object Relations Scale (SCORS: Hilsenroth, Stein, & Pinsker, 2007; Westen, 1995)

to transcribed verbatim narratives provides a unique opportunity to examine implicit

affective representations of relationship schemas, relational expectations, and social and

interpersonal impairment of NSSI.

Hypotheses

We hypothesized that female inpatients with BPD who actively engage in NSSI (the

case group) would narrate stories involving more tumultuous relationships with

others, have more malevolent expectations of relationships, and have more intense,

volatile feelings of aggression compared to a matched control group of BPD female

inpatients (control group). Utilizing ANOVA models we planned two a priori anal-

yses assessing global affective and cognitive factors of the SCORS, and six a priori

analyses of specific domains of social causality and object relations. Within the

domain of object-relations we predicted that the NSSI case group would score more

pathologically on: (a) Affect Tone of Representations, (b) Emotional Investment in

Relationships, (c) Experience and Management of Aggression, and Aggressive Im-

pulses, and (d) Self-esteem. Within the Social Cognition domain we predicted that

patients in the NSSI case group would: evidence greater pathology on the social

cognition variables: (a) Complexity of Representations of People, and (b) Understand-

ing of Social Causality. Because early experiences of trauma (physical and sexual) are

correlated with NSSI, we conducted comparisons between the groups for history of

sexual and physical abuse.

Method

Procedures

Archival records from July 1997 to July 2004 were collected for this study. Patient records

(including identification numbers, diagnostic codes, history of sexual/physical abuse, and

detailed descriptions of specific behavioral manifestations of NSSI) were masked to

disguise patient identity then downloaded from the Center’s database. Diagnoses were

assigned by a board certified and licensed psychologist and psychiatrist according to the

diagnostic criteria of the DSM–IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994)

utilizing the longitudinal expert evaluation using all data (LEAD: Pilkonis, Heape, Ruddy,

& Serrao, 1991). The diagnosis of BPD was confirmed in 100% of the cases by

independent ratings conducted by a psychiatrist or psychologist as an ongoing aspect of

the hospital’s performance improvement practice— diagnosis of BPD was determined

independent of TAT data.

185

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER AND NSSI

The first author classified behavioral records into NSSI case and control groups by

reviewing all nursing records of the BPD female subjects, prior to rating archival TAT

records. The data extracted from the medical records can be considered a reliable and

accurate representation of patients NSSI activity during hospitalization because the

nursing staff were required to record all incidences of self-inflicted lacerations and burns.

Discriminations between NSSI and suicide attempt were based on the Lethality of Suicide

Attempt Rating Scale-II (LSARS-II: Berman, Shepard, & Silverman, 2003): Suicide

attempts were not coded as NSSI. Ratings were made blind to any identifying information,

eliminating the risk of criterion contamination.

Participants

Criteria for inclusion into this study were as follows: (a) Females at least 18 years of age,

(b) Confirmed diagnosis of BPD, (c) Minimum of 60 consecutive days of hospitalization

in order to obtain a representative sample of patient behavior, (d) Complete battery of

psychological tests during the first 20 days of hospitalization. Inclusion in the NSSI group

required a minimum of two episodes of NSSI within six weeks following test adminis-

tration in order to ensure a pattern of NSSI. The control group required a total absence of

NSSI in three months prior to admission, and no incidence of NSSI during hospitalization.

Measures

The Thematic Apperception Test (Murray, 1943) was developed as a narrative test of

personality functioning consisting of 31 scenic pictorials from which subjects are in-

structed to create narratives about the scenes and human representations. The TAT is one

of the most commonly used performance-based personality assessment technique regard-

less of patient demographics or purpose of the evaluation (Archer, Maruish, Imhof, &

Piotrowski, 1991). The TAT elicits information not readily accessible with self-report

methods because the narratives developed express implicit self and object representations

(schemas), expectations or biases regarding interpersonal interactions, and competence in

understanding social interactions. Therefore, the TAT provides rich data about an indi-

vidual’s capacity for interpersonal relatedness in many situations such as family, work,

friendship, and treatment relationships. The TAT data was collected as part of the

hospital’s routine admission and assessment procedures, and used for the purposes of this

study at a later date. Eight standard TAT cards were administered during the initial

evaluation phase of treatment using the procedures and guidelines articulated by Murray

(1943). The following TAT cards were administered in the same order to all patients: 1,

5, 14, Picasso’s La Vie,

1

13MF, 12M, 2, and 18GF. All TAT narratives were tape-recorded

and transcribed. Protocols were scored blind to identifying information and group inclu-

sion, mitigating criterion contamination.

Westen, Lohr, Silk, Kerber, and Goodrich (1990) developed the Social Cognition and

Object Relations Scale (SCORS) to enable clinicians to look beyond the overt presentation

of the patient and evaluate more implicit, dynamic facets of personality functioning.

Integrating social, cognitive, and psychoanalytic theories, the SCORS assesses social,

affective, and self/object representations. The SCORS is one of the most widely studied

rating system for the TAT. Construct validity of the SCORS dimensions is well estab-

lished (Ackerman, Hilsenroth, Clemence, Wetherill & Fowler, 2001). Convergent validity

1

Following David Rapaport’s original guidelines, the fourth card in the sequence administered

at Austen Riggs is a reproduction of Pablo Picasso’s La Vie.

186

WHIPPLE AND FOWLER

of the SCORS has been established comparing studies of normal and clinical samples

diagnosed with DSM–IV Axis II personality disorders (Barends, Westen, Byers, Leigh, &

Silbert, 1990). Moreover, SCORS ratings effectively differentiate DSM–IV personality

disorders, with BPD subjects scoring in the more pathological range on nearly every

variable when compared to other Cluster B and Cluster C groups (Ackerman, Clemence,

Weatherill, & Hilsenroth, 1999). The SCORS dimensions are predictive of psychotherapy

termination and continuation (Ackerman, Hilsenroth, Clemence, Weatherill, & Fowler,

2000), demonstrate good to excellent ecological validity with global relationship func-

tioning scores (Peters, Hilsenroth, Eudell-Simmons, Blagys, & Handler, 2006) and change

in predictable directions over the course of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy

(Fowler et al., 2004; Porcerelli et al., 2006).

The most recent version of the SCORS (Hilsenroth, Stein & Pinsker, 2007) was used

in this study and is made up of eight variables scored on a 7-point global rating. Lower

scores (e.g., 1 or 2) indicate severe pathological responses, whereas higher scores (e.g., 6

or 7) are indicative of healthy functioning. Ratings for each SCORS variable were

averaged across eight narratives to create mean score. The following SCORS dimensions

were rated:

Affect-Tone of Representations (AT) assesses an individual’s expectations from others

in relationships and how the patient describes significant relationships. Capacity for

Emotional Investment in Relationships (EIR) assesses the degree to which representations

reflect a need-gratifying, narcissistic orientation versus an orientation of mutuality and

reciprocity. The Emotional Investment in Values and Moral Standards (EIM) assesses

morality along a continuum from TAT narratives articulating characters who “behave in

selfish, inconsiderate, or aggressive ways without any sense of remorse or guilt” from

those who “think about moral questions in a way that combines abstract thought, a

willingness to challenge or question convention, and genuine compassion and thought-

fulness in actions.” Experience and Management of Aggressive Impulses (AGG) assesses

narrative accounts of character’s ability to control and appropriately express aggression.

Self-esteem (SE) assesses representations of characters in TAT narratives along a contin-

uum from self-loathing to relatively positive without appearing grandiose. Identity and

Coherence of Self (ICS) assesses the coherence and articulation of character identity from

fragmented and poorly articulated to well-integrated characters with a stable and enduring

sense of purpose. Complexity of Representations (COM) assesses a patient’s psycholog-

ical capacity to represent self and others along a continuum from a lack of differentiation

of self and others, to “split” representations along good and bad dimensions, to integration

of positive and negative attributes of self and others in complex ways. Understanding

Social Causality (SC) assesses narratives for coherence of characters’ thoughts, feelings

and behavior as logical, accurate, and psychologically minded. In addition to single

dimensions, we computed overall mean scores for the affective/relationships component

(AT

⫹ IER ⫹ AGG) and social cognition component (COM ⫹ SC).

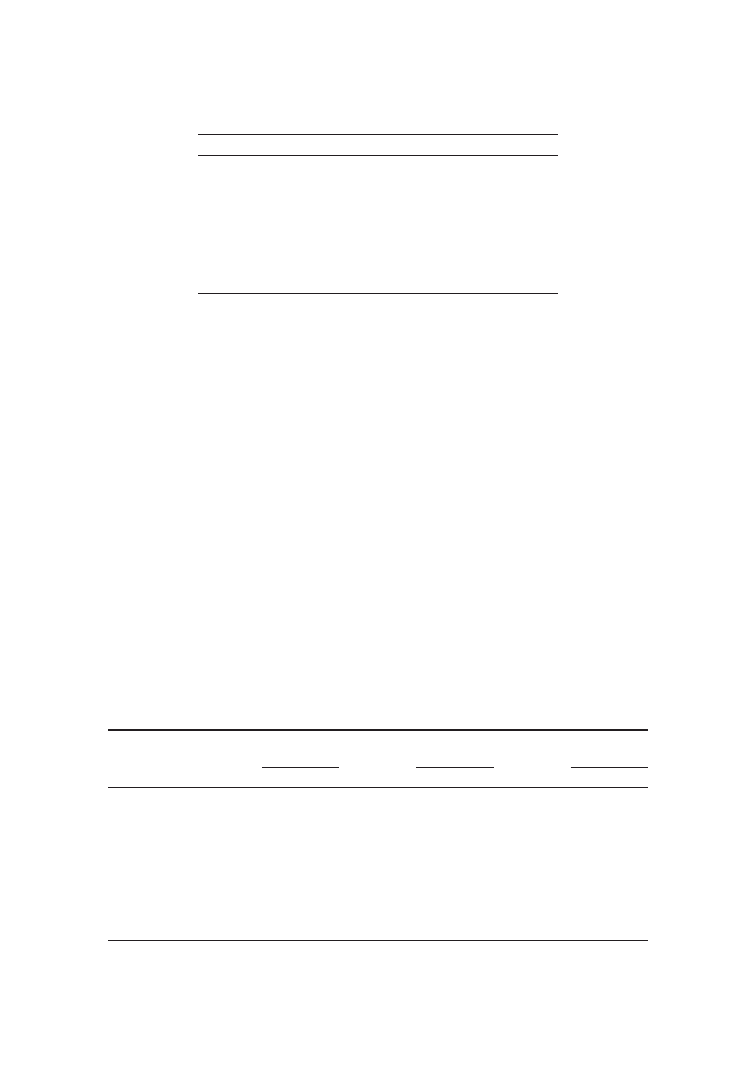

Four raters with varying levels of experience (Undergraduate to PhD psycholo-

gists) performed 10 hours of SCORS training (Hilsenroth, Stein & Pinsker, 2007).

Raters scored a random sample of 25 study protocols consisting of 200 narratives.

Table 1 reports individual subscale reliabilities (ICC

1,1

; Shrout & Fliess, 1979).

Reliability estimates were considered in the “good” to “excellent” range for the

subscales used for assessing hypotheses. Two subscales (Emotional Investment in

Morals and Identity and Self-Coherence) had fair reliability and were therefore were

not included in the analyses.

187

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER AND NSSI

Results

The initial sample consisted of all 141 female borderline patients admitted to the Austen

Riggs Center between July 1997 and July 2004. While all patients with a BPD diagnosis

had multiple Axis I and Axis II disorders, those patients with a comorbid Axis I psychotic

disorder were excluded from the study (n

⫽ 2) as were those who declined the TAT (n ⫽

6). The final sample consisted of 133 female with BPD (65 NSSI case and 68 control) who

were predominantly Caucasian (n

⫽ 128), with three Asian Americans, and two African

Americans. Ninety-eight (73%) patients were single, 28 (21%) were married, and seven

(6%) divorced or widowed. Table 2 provides data on demographic and diagnostic

variables for each group and the total sample. Average age at admission was 30.2 years

(SD

⫽ 9.6). Level of education completed was 14.9 years (SD ⫽ 2.6), mean full scale IQ

was 108 (SD

⫽ 14.5). The sample manifest a high degree of comorbidity with an average

of 4.2 Axis I and II diagnoses (SD

⫽ 1.5). Thirty-three (25%) patients had comorbid

diagnoses of BPD and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and 119 (89%) patients were

diagnosed with comorbid BPD and Major Depressive Disorders. Global Assessment of

Table 2

Demographic and Diagnostic Variables

NSSI BPD

BPD control

Total sample

(n

⫽ 65)

(n

⫽ 68)

(N

⫽ 133)

Mean (SD) (%)

Mean (SD) (%)

Mean (SD) (%)

Age

29.0 (9.3)

31.8 (9.7)

30.2 (9.6)

Education

15.3 (2.9)

14.5 (2.2)

14.9 (2.6)

FSIQ

107 (15.7)

108 (13.0)

108 (14.5)

Total DX

4.3 (1.7)

4.1 (1.3)

4.2 (1.5)

GAF

40.0 (7.1)

39.9 (7.1)

40.0 (7.1)

MDD

55 (85%)

64 (94%)

116 (89%)

PTSD

13 (31%)

20 (29%)

33 (25%)

Physical Abuse

19 (29%)

18 (26%)

37 (28%)

Sexual Abuse

19 (29%)

20 (29%)

39 (29%)

Note.

FSIQ

⫽ Wechsler Full Scale IQ; Total DX ⫽ Total Diagnosis; GAF ⫽ Global Assessment of

Functioning; MDD

⫽ Major Depressive Disorder; PTSD ⫽ Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Table 1

Interrater Reliability of SCORS Variables (n

⫽ 25)

SCORS variable

ICC

Complexity of Representations

.73

Affect-Tone

.81

Emotional Investment in Relationships

.77

Emotional Investment in Morality

.61

Understanding Social Causality

.70

Understanding and Containing Aggressive Impulses

.70

Self-Esteem

.72

Identity and Coherence of the Self

.58

Note.

ICC

⫽ Two-way random effects model Intraclass Correlation

Coefficients.

188

WHIPPLE AND FOWLER

Functioning (GAF: American Psychiatric Association, 1994) score at admission indicated

severe functional disturbance (M

⫽ 40; SD ⫽ 7.1).

Analysis of variance contrasting age, years of education, full scale IQ, total number of

diagnoses, and GAF yielded no significant differences between the two groups. Goodman

and Kruskal’s gamma tests were performed on categorical and dichotomous variables to

detect the association among NSSI and major depressive disorders, PTSD, reports of past

sexual and physical abuse. No significant findings emerged for comorbid diagnoses or

history of past trauma.

A series of one-way ANOVAs were conducted to test a priori hypotheses (see Table

3). In addition to F statistic and significance level, we calculated effect sizes, utilizing

Cohen’s d—values approximating .2, .5, and .8 represent small, medium, and large

effects, respectively (Cohen, 1977).

Hypothesis 1

The NSSI group will manifest greater expectation of malevolence in relationships (AT),

express less investment in relationships (EIR), and have greater difficulty modulating

expression of aggression (AGG). The NSSI case group demonstrated greater pathology on

the overall affective factor (F

(1, 131)

⫽ 9.5, p ⬍ .003; Cohen’s d ⫽ .53, 95% CI ⫽

.44 –.63), created narratives that expressed more malevolent expectations and experiences

of relationships (AT: F

(1, 131)

⫽ 7.4, p ⬍ .008; Cohen’s d ⫽ .49, 95% CI ⫽ .36–.61), less

depth and commitment to emotionally investing in relationships (EIR: F

(1, 131)

⫽ 10.7,

p

⫽ .001; Cohen’s d ⫽ .58, 95% CI .45–.70), and expressed greater intensity of

unmodulated hostility and aggression in narrating interpersonal relationships (AGG:

F

(1, 131)

⫽ 6.4, p ⬍ .01; Cohen’s d ⫽ .44, 95% CI .34–.53). The NSSI case group also

manifested greater difficulty with feelings of self-loathing or grandiosity than the control

group (SE: F

(1, 131)

⫽ 4.9, p ⬍ .03; Cohen’s d ⫽ .40, 95% CI .29–.50).

Hypothesis 2

The NSSI group will create narratives that expressed greater boundary confusion between

self and others (COM) and will manifest greater difficulty understanding interpersonal

interactions (SC). The NSSI case group demonstrated greater pathology on the overall

Table 3

Analysis of Variance for SCORS Variables

NSSI case

BPD control

(N

⫽ 65)

(N

⫽ 68)

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

F

p

ES

95% CI

Affect Factor

3.08

.52

3.39

.64

9.5

.003

.53

.44–.63

Affect Tone

2.99

.65

3.35

.83

7.4

.008

.49

.36–.61

Emotional Investment

2.48

.63

2.90

.82

10.7

.001

.58

.45–.70

Aggression

3.19

.54

3.44

.61

6.4

.01

.44

.34–.53

Cognitive Factor

2.82

.66

3.20

.95

6.9

.01

.47

.33–.61

Complexity

2.93

.64

3.27

.91

6.2

.01

.42

.28–.56

Social Causality

2.72

.71

3.12

1.02

7.0

.009

.46

.31–.61

Post-Hoc Analysis

Self-Esteem

3.22

.53

3.46

.68

4.9

.03

.40

.29–.50

Note.

ES

⫽ Cohen’s d effect size.

189

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER AND NSSI

cognitive factor (F

(1, 131)

⫽ 6.9, p ⫽ .01; Cohen’s d ⫽ .47, 95% CI .33–.61), created

narratives that expressed greater boundary confusion between self and others, and more

difficulty integrating positive and negative aspects of self and others (COM:

F

(1, 131)

⫽ 6.2, p ⬍ .01; Cohen’s d ⫽ .42, 95% CI ⫽ .28–.56), and were less skilled in

understanding interpersonal exchanges, reflecting on possible motivations responsible for

others’ behaviors, and predicting how their behaviors may impact others (SC:

F

(1, 131)

⫽ 7.0, p ⬍ .009; Cohen’s d ⫽ .46, 95% CI ⫽ .31–.61).

These findings support the distinctions between BPD inpatient subgroups, and provide

strong evidence in support of psychodynamic formulations of the correlates of NSSI;

however, it could be argued that these differences would not hold up when comparing

SCORS to outpatient BPD records. While we did not have access to an outpatient sample,

we were able to compare the NSSI case group to a BPD outpatient sample served by a

university-based clinic (Ackerman et al., 1999). We computed effect sizes from Acker-

man’s mean and standard deviations and our NSSI case group data. While both groups of

BPD patients functioned in the pathological range, the NSSI group demonstrated greater

pathology on all SCORS dimensions with large effect size (Cohen’s d ranging from 1.0

to 1.6) for all variables except Aggression that demonstrated a medium effect size

(Cohen’s d

⫽ .66). Still further, could the differences in social causality and object

relations evaporate when comparing clinical and nonclinical samples? To address this

question we computed effect sizes from the means and standard deviations

2

from an early

study by Westen and colleagues (Westen, Lohr, Silk, Gold, & Kreber, 1990) examining

Affect Tone, Emotional Investment in Relationships, Complexity of Representations, and

Social Causality from 30 normal controls comprised of screened for serious psychopa-

thology. Here the differences were far more striking with normal controls creating more

positive and benign narratives whereas the NSSI borderline group demonstrated malev-

olently tinged interpersonal narratives (AT: Cohen’s d

⫽ 2.9). Similar large effect size

differences were observed between normal controls and our NSSI inpatient sample on the

dimension of emotional investment in relationships (EIR: Cohen’s d

⫽ 2.3), understand-

ing social interactions (SC: Cohen’s d

⫽ 2.5), and the degree to which characters were

understood to have complex internal thoughts and feeling and were differentiate from one

another (COM: Cohen’s d

⫽ 2.9). In addition to large effect size differences, the group

means for the normal controls were in the healthy range of functioning, whereas the BPD

NSSI group means were clearly in the pathological range of functioning on all dimensions.

Discussion

Individuals living with borderline personality disorder suffer from impairments in impulse

control, emotional lability, self and other differentiation, and interpersonal deficits con-

sisting of impairments in empathy, intimacy, and complexity and integration of represen-

tations of others (Skodol, 2009). We anticipated that our BPD inpatients’ would narrate

stories dominated by themes of stormy, chaotic, and often violent relationship themes with

little capacity to describe the characters in complex or well-differentiated ways. What was

surprising to us was the degree to which those patients who engaged in self-injury during

treatment were significantly more impaired on every SCORS dimension assessed than a

2

Using Dawes’ (2008) formula, we converted the SCORS variables to a 10-point scale due to

unequal scaling of the SCORS—the original SCORS was a 4-point scale, while the 2007 version is

a 7-point scale.

190

WHIPPLE AND FOWLER

well-matched comparison group, yet did not have more Axis I & II disorders, suffer from

greater impairment in symptom functioning (GAF), nor higher rates of sexual or physical

abuse.

Those who engaged in cutting, burning, or abrading their skin manifested greater

expectations of malevolence from others, expressed less investment in interpersonal

relationships, and manifest more blatant hostility and aggression in their relationship

narratives. Expressions of hostility may be related to NSSI patients’ cognitive bias toward

perceiving others as capricious and rejecting. This cycle may ultimately contribute to

increased incidents of NSSI, because these patients have difficulty tolerating emotions and

rely on self-harming as a pathological way to regulate their affect (Haines, Williams,

Brain, & Wilson, 1995; Ivanoff, Linehan, & Brown, 2001; Kemperman, Russ & Shearin,

1997). Researchers and clinicians have suggested that patients may also use self-injury to

discharge anger or rage toward themselves (Freud, 1949; Soloff et al., 1994) or toward

others (Kernberg, 1984; Simpson & Porter, 1981).

The NSSI patients’ underlying vulnerability to blurring self and other boundaries, and

significant deficits interpreting the motivations of others may predispose them to misin-

terpret many interpersonal interactions as hostile, rejecting, and confirming expectations

of malevolence. The cyclical pattern of interpreting other’s ambiguous behavior as

evidence of cruelty, capriciousness, and rejection may represent what Bateman and

Fonagy (2004) refer to as the cognitive mode of psychic equivalence in which fantasies

and personal expectations are experienced as if they are external reality. This may help to

explain the consistent clinical observations that NSSI patients are more sensitive to

rejection (Simeon et al., 1992), frequently resentful, hypervigilant, and paranoid in their

interactions with others (Yeomans et al., 1994) and experience greater difficulty commu-

nicating and understanding emotion-laden communications (McKay et al., 2004).

Our findings related to deficits in affect competence (AT, IER, and AGG) are

consistent with Rosenthal’s (Rosenthal, Rinzler, Wallsh, & Klausner, 1972) interviews

with individuals immediately following an episode of cutting who described an inability

to deal with specific feelings, leading to a state of depersonalization. The subjects in

Rosenthal’s study cut themselves in an effort to reintegrate, and seemed to understand that

cutting helped to reestablish a coherent sense of self.

So what might a clinician take away from the study findings, and what specific

interventions might help the patient deal more effectively with the symptom of self-

injury? First, therapists will be well-served to keep in mind that self-injury tends to change

slowly in comparison to many other symptoms (Perry et al., 2009), in part because the

behavior serves multiple functions, and is likely to be triggered by upsetting interpersonal

events, emotional upheaval, and misinterpretation of interpersonal interactions—some of

which inevitably represent ruptures in reaction to the therapist’s interventions (Safran &

Muran, 2000).

While NSSI is relatively slow to change in comparison to other symptoms, there is

clear and compelling evidence from well-designed randomized clinical trials that several

forms of psychotherapy help borderline patients decrease the frequency of NSSI and other

self-destructive behaviors (Bateman & Fonagy, 2008; Clarkin, Levy, Lenzenweger, &

Kernberg, 2007; Doering et al., 2010; Levy et al., 2006; Linehan et al., 2006). Psychody-

namic treatment protocols emphasize different mutative interventions for the treatment of

NSSI (Levy, Yoemans, & Diamond, 2007); yet, deconstruction studies assessing specific

interventions impact on rates of NSSI and suicide attempts have not been completed.

Despite the current limitations of our knowledge, we can imagine the potentially palliative

effects on social relationships, as well as decrease in NSSI for BPD patients when

191

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER AND NSSI

interventions successfully enhance the patient’s capacity for: (a) self-reflection and

curiosity about emotional precipitants for NSSI, (b) affect modulation during affect

storms, especially in the context of alliance ruptures, (c) alternative explanations for the

internal motivations for the other’s behaviors beyond the patient’s cognitive bias, (d)

stronger self-other boundary differentiation, and (e) thought experiments to consider the

patient’s influence on social exchanges that are problematic. Given the clear impairments

in the BPD, and especially the NSSI case group’s capacity for understanding complex

social interactions, it may be particularly counterproductive to make complex interpreta-

tions of social exchanges or the patient’s mental states when the patient is affectively

overwhelmed, or when they lack the basic capacities to understand complex social

exchanges.

Several manualized treatments are tailored to enhance the above mental skill sets, and

psychodynamic psychotherapy, more broadly conceived, aims to increase self-awareness,

curiosity, and greater understanding of interpersonal relationships; however, to the best of

our knowledge, only Bateman and Fonagy’s (2004) mentalization-based treatment ex-

plicitly targets the specific deficits of affect regulation, and social causality through four

specific strategies: (a) enhancing mentalization

⫺the ability to understand the mental states

of self and others and how those states influence overt behavior, (b) bridging the gap

between affects and their representations, (c) working mostly with current mental states,

and (d) keeping in mind the patient’s deficits (Bateman & Fonagy, 2004, p. 203). Our

findings of the underlying psychological deficits associated with NSSI highlight the

necessity of treatments to enhance these deficits in order to increase the likelihood of

sustained remission and recovery. Recent evidence (Bateman & Fonagy, 2008) supports

this contention—BPD patients in an 18-month mentalization-based treatment arm dem-

onstrated sustained improvements in functioning (suicide attempts, service use, global

psychiatric functioning, and ratings of borderline functioning) at 5-years postdischarge.

This is particularly promising given that most positive effects of psychotherapy treatment

tend to diminish over time.

Transference-Focused Psychotherapy (TFP) has also proven effective in decreasing

self-destructive behavior in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder

(Clarkin et al., 2007; Doering et al., 2010). Importantly, TFP transforms underlying

representational structures—Levy and colleagues (Levy et al., 2006) found that patients

randomized to a TFP condition evidenced increased attachment coherence and improved

reflective functioning after one year of treatment, whereas patients randomized to a DBT

or supportive psychodynamic psychotherapy did not. This finding suggesting that TFP

interventions of transference interpretations, embedded in the therapy process, specifically

helps to bring about greater integration of disparate or split-mental representations and

their accompanying affects. Both Mentalization-Based Treatment and Transference-

Focused Psychotherapy appear to be effective treatments for reducing self-destructive

behavior in borderline patients. The mounting evidence for effective psychodynamic-

based treatments in reducing self-destructive behaviors and improving social causality and

quality of object representations for patients with borderline personality disorder is

promising for patients suffering with borderline personality disorders.

Conclusions

This study provides empirical support for specific impairments in NSSI patients object

relations and ego functions. In addition to providing support for the clinical observations

192

WHIPPLE AND FOWLER

and theories about NSSI, these results support the utility and sensitivity of the SCORS

measure in assessing the object relations and social cognition of these complex individ-

uals, as well as supporting the value of attending to patient narratives in order to

understand the underlying dynamics of NSSI. Additionally, findings from this study

demonstrate the vast heterogeneity within the BPD category (Oldham, 2006; Skodol &

Bender, 2009).

References

Ackerman, S. J., Clemence, A. J., Weatherill, R., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (1999). Use of the TAT in the

assessment of DSM–IV Cluster B personality disorders. Journal of Personality Assessment, 73,

422– 442.

Ackerman, S. J., Hilsenroth, M. J., Clemence, A. J., Weatherill, R., & Fowler, J. C. (2000). The

effects of social cognition and object representation on psychotherapy continuation. Bulletin of

the Menninger Clinic, 64, 386 – 408.

Ackerman, S. J., Hilsenroth, M. J., Clemence, A. J., Weatherill, R., & Fowler, J. C. (2001).

Convergent validity of Rorschach and TAT scales of object relations. Journal of Personality

Assessment, 77, 295–306.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

(4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Archer, R. P., Maruish, M., Imhof, E. A., & Piotrowski, C. (1991). Psychological test usage with adolescent

clients: 1990 survey findings. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 22, 247–252.

Bach-Y-Rita, G. (1974). Habitual violence and self-mutilation. American Journal of Psychiatry,

131, 1018 –1020.

Baity, M. R., Blais, M. A., Hilsenroth, M. J., Fowler, J. C., & Padawer, J. R. (2009). Self-mutilation,

severity of borderline psychopathology, and the Rorschach. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 73,

203–225.

Barends, A., Westen, D., Leigh, J., Silbert, D., & Byers, S. (1990). Assessing affect-tone in

relationship paradigms from TAT and interview data. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of

Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2, 329 –332.

Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2008). 8-year follow-up of patients treated for borderline personality

disorder: Mentalization-based treatment versus treatment as usual. The American Journal of

Psychiatry, 165, 631– 638.

Bateman, A. W., & Fonagy, P. (2004). Psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Men-

talization based treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berman, A. L., Shepard, G., & Silverman, M. M. (2003). The LSARS-II: Lethality of suicide

attempt rating scale-updated. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 33, 261–276.

Clarkin, J. F., Levy, K. N., Lenzenweger, M. F., & Kernberg, O. F. (2007). Evaluating three

treatments for borderline personality disorder: A multiwave study. American Journal of Psychi-

atry, 164, 922–928.

Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York:

Academic Press.

Dawes, J. (2008). Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An

experiment using 5-point, 7-point and 10-point scales. International Journal of Market Re-

search, 50, 61–77.

Doering, S., Hörz, S., Rentrop, M., Fischer-Kern, M., Schuster, P., Benecke, C., Buchheim, A.,

Martius, P., & Buchheim, P. (2010). Transference-focused psychotherapy v. treatment by

community psychotherapists for borderline personality disorder: Randomised controlled

trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 196, 389 –395.

Dulit, R. A., Fyer, M. R., Leon, A. C., Brodsky, B. S., & Frances, A. J. (1994). Clinical correlates

of self-mutilation in borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152,

1305–1311.

193

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER AND NSSI

Fowler, J. C., Hilsenroth, M. J., & Nolan, E. (2000). Exploring the inner world of self mutilating

borderline patients: A Rorschach investigation. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 64, 365–385.

Fowler, J. F., Ackerman, S. J., Speanburg, S., Bailey, A., Blagys, M., & Conklin, A. C. (2004).

Personality and symptom change in treatment-refractory inpatients: Evaluation of the phase

model of change using Rorschach, TAT, and DSM–IV Axis V. Journal of Personality Assess-

ment, 83, 306 –322.

Freud, S. (1949). An Outline of Psychoanalysis. New York: Norton.

Gratz, K. (2001). Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the deliberate self-harm

inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23, 253–263.

Gratz, K. L., Conrad, S. D., & Roemer, L. (2002). Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among

college students. American Board of Orthopsychiatry, 72, 128 –140.

Haines, J., Williams, C. L., Brain, K. L., & Wilson, G. V. (1995). The psychophysiology of

self-mutilation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 471– 489.

Hillbrand, M., Krystal, J. H., Sharpe, K. S., & Foster, H. G. (1994). Clinical predictors of self-mutilation

in hospitalized forensic patients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 182, 9 –13.

Hilsenroth, M., Stein, M., & Pinsker, J. (2007). Social Cognition and Object Relations Scale: Global

Rating Method (SCORS-G; 3rd ed.). Unpublished manuscript, The Derner Institute of Advanced

Psychological Studies, Adelphi University, Garden City, NY.

Ivanoff, A., Linehan, M. M., & Brown, M. (2001). Dialectical Behavior Therapy for impulsive

self-injurious behaviors. In Simeon, D. & Hollander, E. (Eds.), Self-injurious Behaviors: As-

sessment and Treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Kemperman, I., Russ, M. J., & Shearin, E. (1997). Self-injurious behavior and mood regulation in

borderline patients. Journal of Personality Disorders, 11, 146 –157.

Kernberg, O. F. (1984). Severe personality disorders: Psychotherapeutic strategies. New Haven:

Yale University Press.

Leibenluft, E., Gardner, D. L., & Cowdry, R. W. (1987). The inner experience of the borderline

self-mutilator. Journal of Personality Disorders, 1, 317–324.

Levy, K. N., Meehan, K. B., Kelly, K. M., Reynoso, J. S., Weber, M., Clarkin, J. F., & Kernberg,

O. F. (2006). Change in attachment patterns and reflective function in a randomized control trial

of transference-focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Consulting

and Clinical Psychology, 74, 1027–1040.

Levy, K. N., Yeomans, F. E., & Diamond, D. (2007). Psychodynamic treatments of self-injury.

Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 1105–1120.

Linehan, M. M., Comtois, K. A., Murray, A. M., Brown, M. Z., Gallop, R. J., Heard, H. L.,

Korslund, K. E., Tutek, D. A., Reynolds, S. K., & Lindenboim, N. (2006). Two-year randomized

controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs. therapy by experts for suicidal

behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 757–766.

McKay, D., Gavigan, C. A., & Kulchycky, S. (2004). Social skills and sex-role functioning in

Borderline Personality Disorder: Relationship to self-mutilating behavior. Cognitive Behavioral

Therapy, 33, 27–35.

Murray, H. A. (1943). Thematic Apperception Test: Manual. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Nock, M. K., & Banaji, M. R. (2007). Prediction of suicide ideation and attempts among adolescents

using a brief performance-based test. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 707–715.

Nock, M. K., & Favazza, A. (2009). Non-suicidal self-injury: Definition and classification. In M. K.

Nock (Ed.), Understanding non-suicidal self- injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment (pp.

9 –18). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2005). Contextual features and behavioral functions of self-

mutilation among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 140 –146.

Nock, M. K., Wedig, M. M., Janis, I. B., & Deliberto, T. L. (2008). Self-injurious thoughts and

behaviors. In J. Hunsely & E. Mash (Eds.), A guide to assessments that work (pp. 158 –177). New

York: Oxford University Press.

194

WHIPPLE AND FOWLER

Oldham, J. M. (2006). Borderline Personality Disorder and Suicidality. American Journal of

Psychiatry, 163, 20 –26.

Perry, C. J., Fowler, J. C., Bailey, A., Plakun, E. M., Speanburg, S., Zheutlin, B., & Clemence, A. J.

(2009). Improvement and recovery from suicidal and self-destructive phenomena in treatment-

refractory disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197, 28 –34.

Peters, E. J., Hilsenroth, M. J., Eudell-Simmons, E. M., Blagys, M. D., & Handler, L. (2006).

Reliability and validity of the Social Cognition and Object Relations Scale in clinical use.

Psychotherapy Research, 16, 606 – 614.

Pilkonis, P. A., Heape, C. L., Ruddy, J., & Serrao, P. (1991). Validity in the diagnosis of personality

disorders: The use of the LEAD standard. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting

and Clinical Psychology, 3, 46 –54.

Plakun, E. M. (1994). Principles in the psychotherapy of self-destructive borderline patients. Journal

of Psychotherapy Practice & Research, 3, 138 –148.

Porcerelli, J. H., Shahar, G., Blatt, S. J., Ford, R. Q., Mezza, J. A., & Greenlee, L. M. (2006). Social

Cognition and Object Relations Scale: Convergent validity and changes following intensive

inpatient treatment. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 407– 417.

Rosenthal, R. J., Rinzler, C., Wallsh, R., & Klausner, E. (1972). Wrist-cutting syndrome: The

meaning of a gesture. American Journal of Psychiatry, 128, 1363–1368.

Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance. New York: Guilford

Press.

Shrout, P., & Fleiss, J. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psycho-

logical Bulletin, 86, 420 – 428.

Simeon, D., Stanley, B., Frances, A., Mann, J. J., Winchel, R., & Stanley, M. (1992). Self-mutilation

in personality disorders: Psychological and biological correlates. American Journal of Psychi-

atry, 149, 221–226.

Simpson, C. A., & Porter, G. L. (1981). Self-mutilation in children and adolescents. Bulletin of the

Menninger Clinic, 45, 428 – 438.

Skodol, A. E. (April, 2009). Report of the DSM-V Personality and Personality Disorders Work

Group. Retrieved from http://www.psych.org/MainMenu/Research/DSMIV/DSMV/

DSMRevisionActivities/DSM-V-Work-Group-Reports/Personality-and-Personality-

Disorders-Work-Group-Report.aspx

Skodol, A. E., & Bender, D. S. (2009). The Future of Personality Disorders in DSM-V? American

Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 388 –391.

Soloff, P. H., Lis, J. A., Kelly, T., Cornelius, J., & Ulrich, R. (1994). Self-mutilation and suicidal

behavior in Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 8, 257–267.

Stolorow, R. D., & Lachmann, F. M. (1980). Psychoanalysis of Developmental Arrests: Theory and

Treatment. New York: International Universities Press, Inc.

Westen, D. (1995). Social Cognition and Object Relations Scale: Q-sort for projective stories.

Unpublished manuscript, Harvard University Medical School, Boston, MA.

Westen, D., Lohr, N., Silk, K., Gold, L., & Kreber, K. (1990). Object relations and social cognition

in borderlines, major depressives, and normals: A Thematic Apperception Test analysis. Psy-

chological Assessment, 2, 355–364.

Yeomans, F. E., Hull, J. W., & Clarkin, J. C. (1994). Risk factors for self-damaging acts in a

borderline population. Journal of Personality Disorder, 8, 10 –16.

Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Reich, D. B., Fitzmaurice, G., Weinberg, I., & Gunderson, J. G.

(2008). The 10-year course of physically self-destructive acts reported by borderline patients and

Axis II comparison subjects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 117, 177–184.

195

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER AND NSSI

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

(psychology, self help) Shyness and Social Anxiety A Self Help Guide

(autyzm) Hadjakhani Et Al , 2005 Anatomical Differences In The Mirror Neuron System And Social Cogn

Revealing the Form and Function of Self Injurious Thoughts and Behaviours A Real Time Ecological As

Human Relations and Social Responsibility

Making Contact with the Self Injurious Adolescent BPD, Gestalt Therapy and Dialectical Behavioral T

Family and social life Relationship Frendship, love and sex (tłumaczenie)

Political Conservatism as Motivated Social Cognition Jost, Glaser,Kruglanski and Sulloway

Self Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview

Family and social life Relationship Marriage (55)

cognitive and social sides of epistemology

Physiological Arousal, Distress Tolerance, and Social Problem Solving Deficits Among Adolescent Self

Family and social life Relationship Marriage (tłumaczenie)

Culture, Trust, and Social Networks

Bussey, Bandura Social Cognitive Theory Gender Development

business groups and social welfae in emerging markets

No Man's land Gender bias and social constructivism in the diagnosis of borderline personality disor

The Relationships?tween Semiotics and The Quaker Company

więcej podobnych podstron