35

Amharic

Grover Hudson

1 History and Society

Amharic is the second most populous Semitic language, after Arabic, with some 20 million

speakers (16 million of the 1994 Ethiopian census + expected growth rate to 2009).

Amharic has long been the lingua franca of Ethiopia, and, despite recent movement

toward local-language primary education, in most schools still the language of instruc-

tion in the early grades. (Since the late 1940s, English has been the language of sec-

ondary and higher education.) It is recognised in the 1994 constitution as the

‘working

language

’ of Ethiopian government.

Amharic is spoken as a second language by additional millions of Ethiopian urban

dwellers, and Amharic readers certainly represent the large majority of the reported

Ethiopian literacy rate of 42 per cent.

The internal grouping of Semitic languages is controversial, but three branches are

usually mentioned: northeast, northwest and south. Northwest includes Arabic, Hebrew

and Aramaic; northeast anciently known and long extinct Akkadian-Babylonian; and

southern Semitic the ancient and modern languages native to South Arabia plus

those of Ethiopia and Eritrea, of which there are some thirteen: Tigre and Tigrinya of

Eritrea, with Tigrinya also spoken by some 3.5 million in Ethiopia; in Ethiopia are

Amharic, Soddo (also known as Kistane), Mesqan, Chaha with several named dialects;

Inor also with several named dialects, Argobba a language not quite mutually intelli-

gible with Amharic, Harari (Adare), Silt

’e with several named dialects, and Zay.

Ethiopian Semitic Gafat has been extinct for some decades, and Ge

‘ez, for which there

are epigraphic records dating from perhaps 2500

BP

, survives as the liturgical language

of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Ge

‘ez seems not to be the ancestor of any modern

language.

The traditional home of Amharic is mountainous north-central Ethiopia, and Amharic

dialects are recognised in the regions of Begemder, Gojjam, Menz-Wello and Shoa.

These differ by features of pronunciation and grammatical morphology. The Ethiopian

capital city Addis Ababa, Shoa, is the centre of Ethiopian political, economic and social

life, and the Amharic variety of Addis Ababa has become recognised as prestigious.

594

There are Amharic manuscripts from the fourteenth century, and modern writings

and publication in Amharic include poetry, newspapers, literary and news magazines,

drama, novels, history, textbooks, etc. Amharic language magazines are published in

Europe and the US to serve the now considerable Ethiopian expatriate populations

there.

Amharic has borrowed words from Arabic, French, Italian, and now especially English,

but these are not prominent. Ge

‘ez is favoured as a source for new word invention.

Because other anciently known Semitic languages notably Arabic, Aramaic, Hebrew,

and Akkadian are all in the Middle East, and because there is evidence of South Arabian

presence in northeast Africa from perhaps as early as 2500

BP

, it is generally believed

that Semitic languages were brought into northeast Africa in near historic time by migra-

tions from South Arabia. However, because Semitic is only one of six branches in the

family of Afroasiatic languages, and because Africa is home to the

five non-Semitic

groups Chadic (West Africa), Berber (North Africa), Egyptian (Egypt), Omotic (Ethiopia

and eastern Sudan) and Cushitic (centred in Ethiopia), and because ancient Ethiopian

Semitic culture and the modern languages have many features not descendant from

those of South Arabia, it is also possible that Semitic origins are African and perhaps

Ethiopian.

Ethiopian Semitic, Cushitic and Omotic languages have certainly coexisted in Ethiopia

for at least two thousand years, and probably for this reason share numerous features of

an Ethiopian language type characterised by phonological, morphological and syntactic

features including glottalised ejective consonants, a special non-

finite verb for verb

sequences, verb idioms based on the verb

‘say’, and word-order characteristics of verb-

final (SOV) languages. Many Semitic languages, indeed, are verb-initial (VSO) lan-

guages, including ancient Ethiopian Semitic Ge

‘ez, but Amharic and the other modern

Ethiopian Semitic languages have some characteristics of both SOV and VSO types

(notably VSO-type prepositions), which suggests that they have changed this aspect of

their grammars under the in

fluence of Cushitic and Omotic neighbours. Similarly, most

Middle Eastern Semitic languages lack the Ethiopian areal feature of glottalised ejective

consonants. In this case, however, the presence of glottalised ejectives in Chadic, South

Arabian Semitic and some Arabic dialects suggests that in this characteristic Amharic

and Ethiopian Semitic languages preserve the original Afroasiatic type.

2 Phonology

2.1 Consonants

Amharic has the thirty-one consonant phonemes of Table 35.1, where phonetic symbols

have International Phonetic Association (IPA) values except that y = palatal glide j, c

ˇ

and

˚ˇ

= alveopalatal affricates

ʧ

and

ʤ

;

š and ž = alveopalatal fricatives

ʃ

and

Z

; n

ˇ =

palatal nasal

ɲ

; and r is a tap and long r (rr) a trill.

The series of labialised

‘velars’ k

w

, g

w

, k

w

’, and h

w

(h

w

historically a velar < x

w

)

might be considered sequences of consonant + w (which do arise in word-formation),

but three facts suggest that these are best considered to be functionally unitary: (1) the

consonant and w are never separated by vowels in word-formation processes as are

root-consonant sequences; (2) they freely occur at the beginning of words where other

AMHARIC

595

consonant sequences are absent or rare; and (3) they have special forms in the Amharic

writing system.

Labials p, p

’ and v are rare: p and p’ only in loanwords some of which like ityopp’

ɑ

‘Ethiopia’ < Greek are long established in the language, and the voiced labiodental

fricative v is only in recent borrowings such as volibol

‘volleyball’.

Consonant sequences are at most two; at the beginning of words these consist of

C+r/l as in gr

ɑ ‘left’ and blen ‘pupil of eye’, though these may also be considered gi-rɑ

and bi-len. The glottal stop

?

and labialised consonants do not occur at the end of syl-

lables (or, thus, words), and the alveopalatal nasal n

ˇ does not occur at the beginning of

native words. The glottal stop may be considered an allophonic effect of syllable-initial

vowels, as in [

?]ityopp’y

ɑ ‘Ethiopia’, s

@

[

?]

ɑt ‘hour, clock/watch’. Glottalised ejective s’

is replaced by t

’ in rural speech, and the voiced alveopalatals ž and

˚ˇ

are free or idio-

lectal variants. Voiceless released stops are slightly aspirated. The nongeminate voiced

labial and velar stops b and g are spirants [

b] and [

Ɣ

] between vowels, as in le[

b]

ɑ

‘thief’, w

ɑ[

Ɣ

]

ɑ ‘price’. The sequences k

w

’

@

and k

w

’i- vary as k’o and k’u, respectively, as

in k

w

’

@

ss

@

l

@

~k

w

’oss

@

l

@

‘he was wounded’, k

w

’i-t’i-r~k’ut’i-r ‘number’. The velar and labial

stops tend to be labialised before round vowels, e.g. b

w

ot

ɑ ‘place’, k’

w

um

‘stop/stand!’.

Between vowels the glides w, y are very lax (h

ɑyɑ [hɑ

y

ɑ] ‘twenty’). In northern dialects

except of Gondar there is palatalisation of obstruents as glide insertion before the front

vowels i and e, which vowels may in this case be centralised, thus bet > b

y

et ‘house’

and hid > h

y

i-d

‘go (Sg.2m.)!’ In the Menz dialect velars k and k’ are replaced by cˇ and

c

ˇ’ respectively before i and e.

Except for h and

?

, consonants may be long between vowels and at the end of words.

The long consonants are usually written here as sequences of like consonants, and

the glottalised consonants as CC

’ not C’C’. Grammatically significant length may be

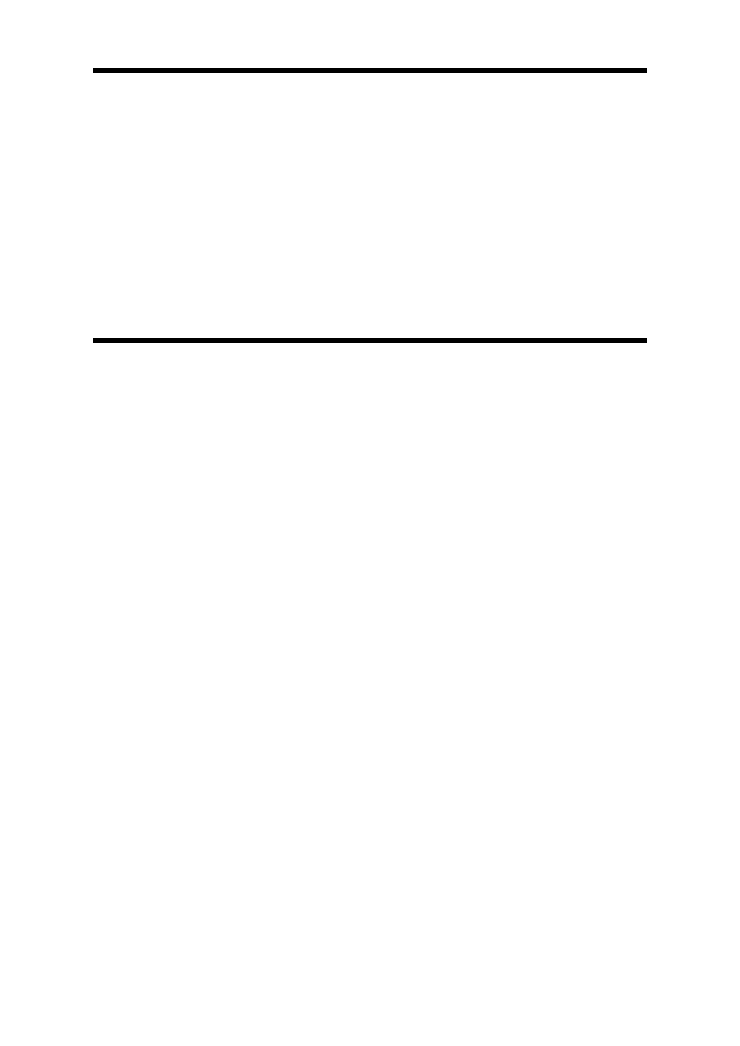

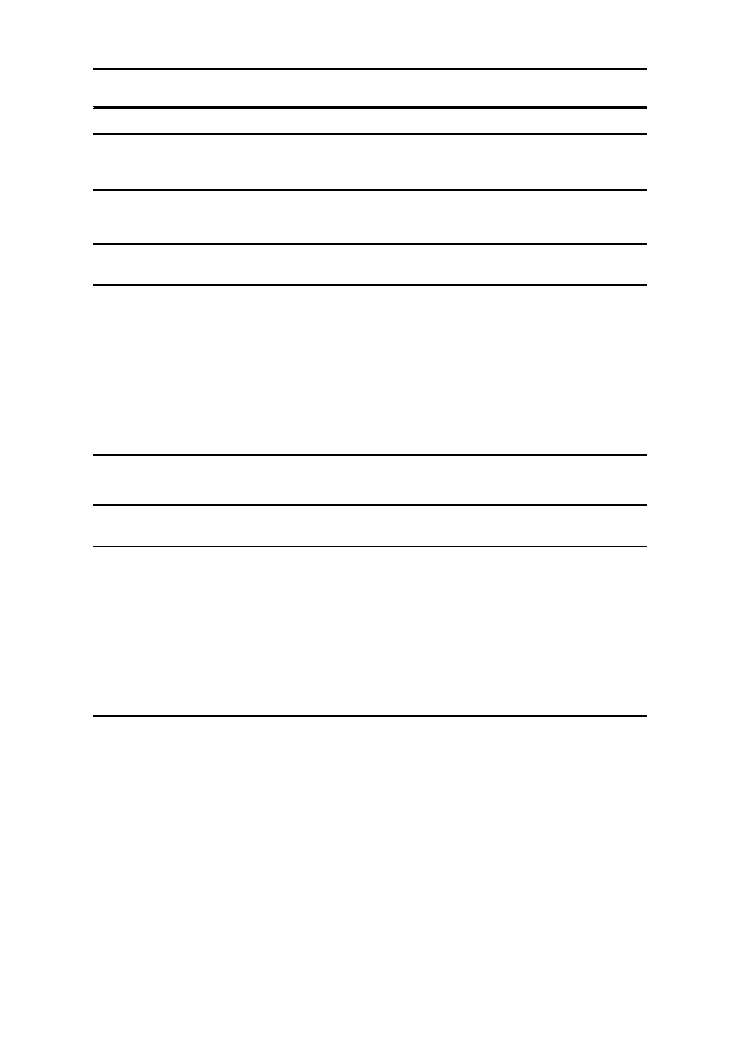

Table 35.1 Consonants

Labial

Alveolar

Alveopalatal

Velar

Glottal

Stops

vls

p

t

k, k

w

?

vd

b

d

g, g

w

gl

p

’

t

’

k

’, k

w

’

Affricates

vl

c

ˇ

vd

˚ˇ

gl

c

ˇ’

Fricatives

vl

f

s

š

h, h

w

vd

z

ž

gl

s

’

Nasals

m

n

n

ˇ

Lateral

l

Rhotic

r

Glides

w*

y

Notes: vl = voiceless, vd=voiced; gl=glottalized.

* Has also velar articulation.

AMHARIC

596

written C:, for example t: in m

@

t:

ɑ ‘he hit’, to emphasise that length in this case is a

function of the past conjugation and not a lexical characteristic of the verb

‘hit’.

When followed by the suf

fix -i (instrumental, agentive, Sg.2f. subject) and -e of

the Sg.1 conjunct, alveolar consonants except r are replaced by corresponding alveo-

palatals: t > c

ˇ, d >

˚ˇ

, s

’ and t’ > cˇ’, s > š, z > ž (optionally ž >

˚ˇ

), n > n

ˇ, and, except in

the Menz dialect, l > y. For example, ti-m

@

t-i > ti-m

@

c

ˇ(i) ‘you (Sg.f.) hit’, hid-i > hi

˚ˇ

(i)

‘Go

(Sg.2f.)!

’, yi-z-:e > yi-ž:e ‘I holding’. The suffix -i may be absent with these replacements.

(Sg.1 possessive -e does not have these palatalisations: bet-e

‘my house’.)

2.2 Vowels

Amharic has the seven vowels of Table 35.2, in which phonetic symbols have International

Phonetic Association values (much writing on Amharic has

ɑ

¨

and

@

respectively for

@

and i-). Mid-front e has a variant e after h as in h[

e]d

@

‘he went’. Words begin and end

in any of the vowels except that i- does not occur at the end of words except in the archaic

question suf

fix -ni-, nor

@

at the beginning of words except in the interjection

@

r

@

‘Really?’

Non-low central vowels i- and

@

are usually elided by adjacent vowels, and i- is elided

by

@

, for example b

@

-

ɑncˇi > bɑncˇi ‘by you (Sg.2f.)’ and b

@

-i-rgi-t

’ > b

@

rgi-t

’ ‘truly’ (lit. ‘in

truth

’). A sequence of like vowels is reduced to one:

ɑsrɑ-ɑnd > ɑsrɑnd ‘eleven’, yi-b

@

l

ɑ-ɑl

> yi-b

@

l

ɑl ‘he eats’.

The high central vowel i- is usually considered to be inserted (epenthesised) to sepa-

rate disallowed consonant sequences which frequently arise in word-formation, as in

y-w

@

sd-h > yi-w

@

sdi-h

‘he takes you (Sg.m.)’; most occurrences of this vowel may be

considered to be epenthetic.

Sg.2f. and Pl.3 verb-subject suf

fixes -i and -u may be replaced by y and w respec-

tively when followed by

ɑ: ti-n

@

gri-

ɑlli-š > ti-n

@

gry

ɑlli-š ‘you (Sg.f.) tell’, n

@

gg

@

r-u-

ɑt >

n

@

gg

@

rw

ɑt ‘they told her’; alternatively y/w may be inserted in these cases: ti-n

@

griy

ɑlli-š,

n

@

gg

@

ruw

ɑt. Oppositely, the Sg.3m. and Pl.3 verb-subject prefix y- is replaced by i

when it follows a consonant, as in s-y-hed > sihed

‘when he goes’.

2.3 Stress

Stress is not prominent in Amharic. Suf

fixes except the plural suffix are unstressed,

and, generally, stress is on a

final closed syllable of a stem and otherwise next to last:

m

@

skót

‘window’, mı´s

ɑ ‘lunch’, mı´sɑ-e ‘my lunch’, m

@

skót-óc

ˇcˇ ‘windows’. But stress is

advanced to the vowel before a grammatically long consonant, as in k

@

´ bb

@

d

@

‘he

broke

’, where the long consonant is a grammatical characteristic of the past tense; cf.

k

@

bb

@

´ d

@

, a male name, with next-to-last syllable stress.

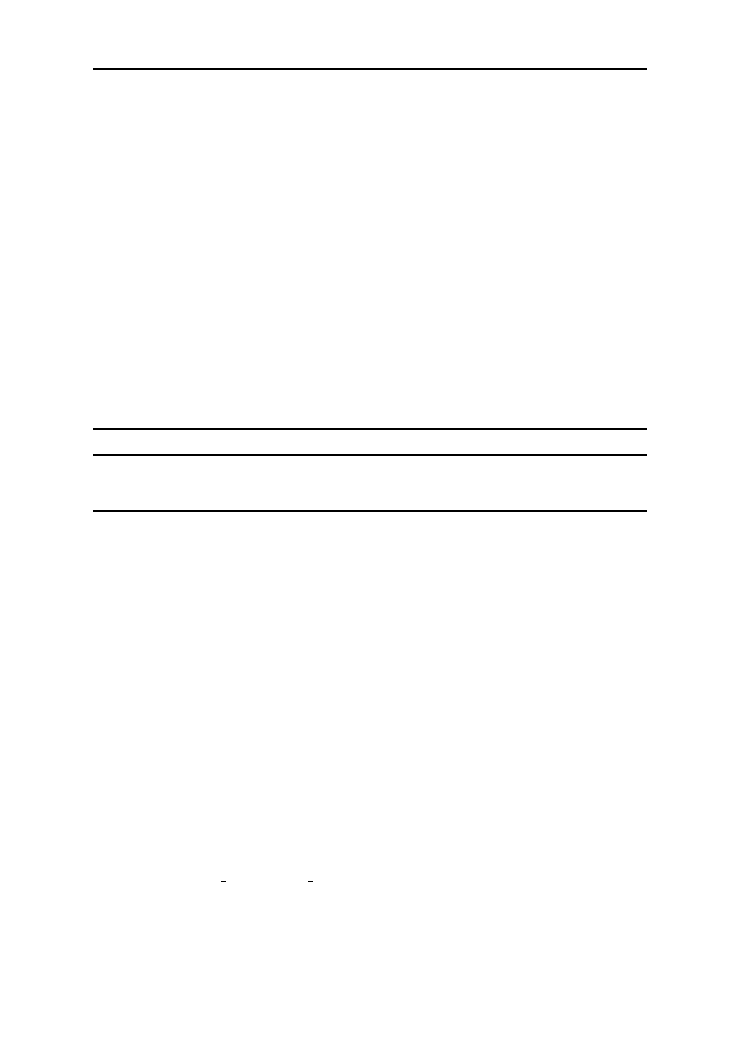

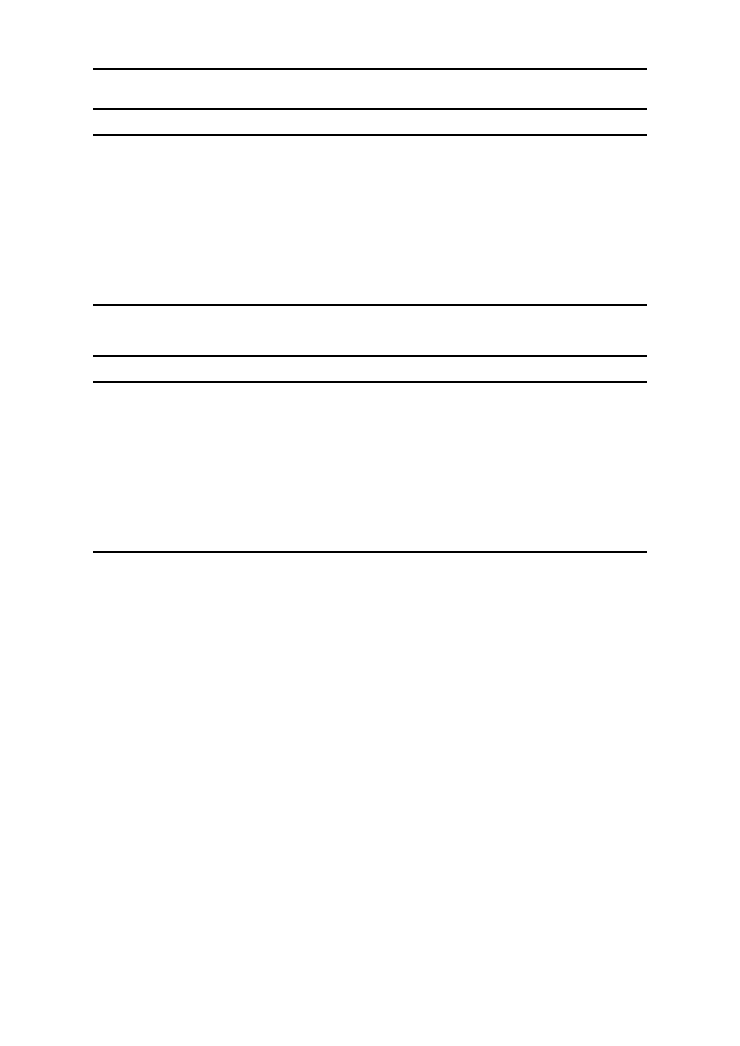

Table 35.2 Vowels

Front

Central

Back

High

i

i-

u

Mid

e

@

o

Low

ɑ

AMHARIC

597

3 Morphology

3.1 Pronouns

There are three pronoun sets (not including verb subject agreements), presented in

Table 35.3: independent, object suf

fix and possessive suffix pronouns. Object pronouns

are shown suf

fixed to the verb n

@

gg

@

r

@

‘he told’ and the possessive pronouns suffixed

to the noun bet

‘house’. Gender and politeness are distinguished in the Sg.2 and Sg.3

forms. Polite forms are for elders and adult unfamiliars.

Independent Sg.2pol.

ɑntu is common only in Wello and Gondar. The four pronouns

with i-ss each have alternate forms with i-rs: i-rs-u, i-rs-w

ɑ, i-rs-wo and i-rs-ɑcˇcˇ

@

w, re

flect-

ing the emphatic/re

flexive origin of these as possessive forms of *i-rs ‘head’ or *ki-rs

‘belly’. The Pl.2/3 independent forms reflect a plural morpheme i-nn

@

- (as in i-nn

@

-t

@

sf

ɑye

‘those associated with Tesfaye’) prefixed to the Sg.m. forms, respectively.

Pronouns are usually expressed by bound rather than independent forms, as verb subject,

object and noun possessor. The verb subject pronouns are presented with discussion of

verbs and conjugations, in Section 3.6 below.

The bound Sg.3m. object pronoun -w (Table 35.3) is replaced by -t after round

vowels as in n

@

gg

@

ru-t

‘they told him’ and n

@

gro-t

‘he, telling him’. The Sg.1, Sg.3m.

and Pl.1 object suf

fixes have an initial vowel

@

when they follow consonants other than

alveopalatals; thus n

@

gg

@

r-k-

@

n

ˇnˇ ‘you (Sg.m.) told me’ vs n

@

gg

@

r-

š-i-nˇnˇ ‘you (Sg.f.) told

me

’, and wi-s

@

d-

@

w

‘you (Sg.m.) take it/him!’ vs wi-s

@

˚ˇ

-i-w

‘you (Sg.f.) take it/him!’ The

object and possessive Pl.2, Pl.3, and possessive Pl.1 suf

fixes include a plural morpheme

-

ɑcˇcˇ probably cognate with the noun plural suffix -ocˇcˇ.

Two prepositions -bb-

‘at, on’ and -ll- ‘to, for’ are suffixed to verb stems and take

object suf

fixes as their objects, except that of Sg.3m. is -

@

t (not -

@

w) for example

f

@

rr

@

d

@

-bb-

@

n

ˇnˇ ‘he judged against me’, yi-f

@

rd-i-ll-

@

t

‘he judges for him’ (the i- is epen-

thetic). (When not suf

fixed to verb stems, prepositions accept independent pronouns as

their objects, as in b

@

ne (< b

@

-i-ne)

‘by/on me’, l

ɑncˇi (< l

@

-

ɑncˇi) ‘for you (Sg.f.)’.)

The bound Sg.3m. possessive pronoun -u

‘his’ is replaced by -w after vowels, for

example b

@

k

’lo-w ‘his mule’. The vowel i- of Sg.2m. and Sg.2f. possessive suffixes is

not epenthetic, as shown by the contrast of bet-i-

š ‘your (Sg.f.) house’ and mot-š ‘you

(Sg.f.) died

’, the latter with vowelless object -š and no epenthesis.

Table 35.3 Three pronoun sets

Independent

Verb object

Possessive

Sg.

1

i-ne

n

@

gg

@

r

@

-n

ˇnˇ

*

bet-e

**

2

m

ɑnt

@

n

@

gg

@

r

@

-h

bet-i-h

f

ɑncˇi

n

@

gg

@

r

@

-

š

bet-i-

š

pol

i-sswo ~

ɑntu

n

@

gg

@

r

@

-wo(t)

bet-wo

3

m

i-ssu

n

@

gg

@

r

@

-w

bet-u

f

i-ssw

ɑ ~ i-ss

w

ɑ

n

@

gg

@

r-

ɑt

bet-w

ɑ

pol

i-ss

ɑcˇcˇ

@

w

(=Pl.3)

(=Pl.3)

Pl.

1

i-n

ˇnˇ

ɑ

n

@

gg

@

r

@

-n

bet-

ɑcˇcˇi-n

2

i-nn

ɑnt

@

n

@

gg

@

r-

ɑcˇcˇi-hu

bet-

ɑcˇcˇi-hu

3

i-nn

@

ssu

n

@

gg

@

r-

ɑcˇcˇ

@

w

bet-

ɑcˇcˇ

@

w

Notes: * ‘He told me’; ** ‘my house’.

AMHARIC

598

Re

flexive-emphatic pronouns are formed as possessives of r

ɑs ‘head’, for example

r

ɑs-e ‘I myself’, rɑs-ɑcˇcˇi-n ‘we ourselves’ (i-ne rɑse m

@

tt

’

ɑhu ‘I myself came’).

Interrogative pronouns include m

ɑn ‘who’, mi-n ‘what’ (mi-ndi-r in mi-ndi-r n

@

w

(> mi-ndi-nn

@

w)

‘What is it?’), m

@

c

ˇe ‘when’, and y

@

t

‘where’. These are suffixed by -m

(-i-m with epenthesis) to provide negative inde

finite pronouns: m

ɑn-i-m ɑlm

@

tt

’

ɑm

‘nobody came’, y

@

t-i-m

ɑlhedi-m ‘I won’t go anywhere’. Other question words are

y

@

ti-n

ˇnˇ

ɑw ‘which’, si-nt ‘how much’, l

@

mi-n

‘why’ (lit. ‘for what’), i-nd

@

-mi-n

‘how’ (i-nd

@

‘like’), and i-ndet ‘how’ (< i-nd

@

-y

@

t

‘like where’).

3.2 Nouns

3.2.1 Gender

The gender of a noun is apparent in its choice of pronoun, agreement with the verb,

demonstrative, and de

finite article suffix. There is no neuter, and the feminine class is

mostly natural, except for a few inanimate nouns including the sun and moon, names of

countries, and small animals such as cats and mice, perhaps re

flecting a diminutive

usage of the feminine. Many feminine human nouns end in an archaic and non-productive

feminine t, including i-nn

ɑt ‘mother’, i-hi-t ‘sister’, ni-gi-st ‘queen’ (cf. ni-gus ‘king’), and a

few nouns have feminine suf

fix -it, including

ɑrogit ‘old woman’ (ɑroge ‘old’) and

ɑndit ‘a little one (f.)’ (ɑnd ‘one’) (this also in the fem. definite article -it-u).

3.2.2 Definiteness

De

finite common nouns have suffixes -u/-w (-w after vowels) for masc. and -w

ɑ or less

commonly -itu for fem. Masc. -u and -w

ɑ are identical to Sg.3m. possessives: wi-šɑ-w

‘the dog (m.)’ (or ‘his dog’), di-mm

@

t-w

ɑ ‘the cat (f.)’ (or ‘her cat’) or di-mm

@

t-itu

‘the

cat (f.)

’. The definite suffix is mutually exclusive with the possessives. Nouns s

@

w

‘man’ and set ‘woman’ have special definite-specific forms s

@

w-i-yye-w

‘the man’,

set-i-yyo-w

ɑ ‘the woman’.

3.2.3 Indefinite Article

The numeral

ɑnd ‘one’ functions as an indefinite-specific article, as in ɑnd bet t

@

k

’

ɑtt’

@

l

@

‘a (certain) house burned down’. Repetition of

ɑnd expresses plural indefinite ‘some,

various, a few

’:

ɑndɑnd bet t

@

k

’

ɑtt’

@

l

@

‘a few houses burned down.’

3.2.4 Plurality

The regular noun plural suf

fix is -ocˇcˇ: bet-ocˇcˇ ‘houses’, s

@

w-oc

ˇcˇ ‘people’. After nouns

ending in i or e, y may be inserted: g

@

b

@

re-yoc

ˇcˇ ‘farmers’ (or reflecting o of the suffix,

g

@

b

@

re-woc

ˇcˇ), and w after u and o; b

@

k

’lo-wocˇcˇ ‘mules’. Suffix o may elide the noun-

final vowel: m

@

kin

ɑ-ocˇcˇ > m

@

kinoc

ˇcˇ ‘cars’, b

@

k

’lo-ocˇcˇ > b

@

k

’locˇcˇ ‘mules’. There are

some irregular plurals in -

ɑt and -ɑn, probably Ge‘ez or pseudo-Ge‘ez formations,

including k

’

ɑl-ɑt ‘words’ and k’i-ddus-ɑn ‘saints’. With plural quantifiers, the plural

suf

fix may be absent: bi-zu s

@

w

‘many people’, hul

@

t li-

˚ˇ

‘two children’. Adjectives (see

below) may also be pluralised. Other suf

fixes attach to the plural: bet-ocˇcˇ-u ‘the

houses

’, bet-ocˇcˇ-

ɑcˇcˇi-n ‘our houses’.

AMHARIC

599

3.2.5 Genitive

Possessive or genitive nouns and pronouns are pre

fixed by y

@

-: y

@

-ssu bet

‘his house’,

y

@

-k

@

t

@

m

ɑ li-

˚ˇ

‘a town boy’, y

@

-bet k

’ulf ‘lock of a house/house lock’. This prefix is

absent following another pre

fix: l

@

-ssu bet

‘for his house’. Familiar such relations may

be expressed by simple juxtaposition, as in t

@

m

ɑri bet ‘school house’. This prefix also

marks relative clauses (see below).

3.2.6 Definite object

De

finite objects of verbs (also indefinites sometimes in older writing), are suffixed by

-n: bet-u-n w

@

dd

@

d

@

‘he liked the house’,

ɑbbɑt-e-n ɑyy

@

-hu

‘I told my father’. Definite

objects optionally and typically topicalised de

finite objects, which precede the sentence

subject, are marked as

‘resumptive’ verb-object pronouns, as in leb

ɑ-w-n polis-ocˇcˇu

y

ɑzzu-t ‘policemen caught the thief’ (-t ‘him’).

3.2.7 Topicaliser

Nouns raised as topics, including those contrasted with others, are suf

fixed by m, as in

t

’w

ɑt yohɑnni-s-i-m d

@

ww

@

l

@

-n

ˇnˇ ‘in the morning YOHANNIS called me’, and yoh

ɑnni-s-i-m

yi-m

@

t

’

ɑl ‘As for Yohannis, he will come’ or ‘Yohannis will come too’. In questions an

equivalent morpheme is -ss:

ɑnt

@

-ss?

‘What about you (Sg.m.)?’ (This suffix is histori-

cally mm, but the length is now rarely heard. A cognate suf

fix has become obligatory

on negative main verbs.)

3.2.8 Derived Nouns

There are a number of ways to derive nouns from verbs and other nouns. An instru-

ment or location is formed on the verb in

finitive by suffixing -iy

ɑ: m

@

t

’r

@

g-iy

ɑ ‘broom’

(t

’

@

rr

@

g

@

‘he swept’), m

@

c

ˇ

@

rr

@

š-

ɑ (< m

@

c

ˇ

@

rr

@

s-iy

ɑ) ‘finish, conclusion’ (cˇ

@

rr

@

s

@

‘he fin-

ished

’). An agent of a verb is expressed by a special stem suffixed by -i; verbs with

three or four root consonants have

ɑ after the next to last: n

@

g

ɑri ‘teller’ (root ngr),

t

@

rg

w

ɑmi ‘translator’ (trg

w

m); a derivation with a two-consonant root is s

@

mi

‘hearer’

(root sm

ɑ). Historical y or w appears in the agent of a two-consonant root whose basic

form has e < y or o < w: hiy

ɑ

˚ˇ

(i)

‘goer’ (hed

@

‘he went’), k’

@

w

ɑmi ‘stander’ (k’om

@

‘he

stood

’). An agent based on a noun is formed on the noun suffixed by -

@

n

ˇnˇ

ɑ: k’

@

ld-

@

n

ˇnˇ

ɑ

‘joker’ (k’

@

ld

‘joke’), f

@

r

@

s-

@

n

ˇnˇ

ɑ ‘horseman’ (f

@

r

@

s

‘horse’). (This suffix also forms

ordinal from cardinal numerals; see below.) Nationality is expressed by a place-name

and the suf

fix -

ɑwi: ingliz-ɑwi ‘English(man)’; also in ɑm

@

t-

ɑwi ‘annually’ (ɑm

@

t

‘year’).

An abstract noun of quality has the suf

fix -nn

@

t: set-i-nn

@

t

‘womanhood’ (set ‘woman’),

di-h

ɑ-nn

@

t

‘poverty’ (di-h

ɑ ‘poor’).

3.3 Adjectives

There are words whose usual function is as attribute to nouns including in comparisons,

such as ti-lli-k

’ ‘big, important’ and

ɑroge ‘old (non-human)’: ti-lli-k’ s

@

w

‘big (important)

person

’,

ɑroge bet ‘old house’. These may be nouns in fact (and only incipiently

adjectives), understood as ti-lli-k

’ ‘a big one’,

ɑroge ‘an old one’; they take the definite

AMHARIC

600

article, de

finite object, and plural suffixes: ti-lli-k’-u ‘the big one (m.)’, ti-lli-k’-ocˇcˇ ‘big

ones

’, k’on

˚ˇ

o-w

ɑ ‘the pretty one (f.)’, k’on

˚ˇ

o-woc

ˇcˇ ‘pretty ones’, k’on

˚ˇ

o-w

ɑ-n m

@

kin

ɑ

š

@

t

’

@

‘he sold the pretty car (f.).’ As in the previous example, the definite suffix attaches

to the adjective; but a possessive suf

fix attaches to the noun: ti-lli-k’-u bet ‘the big house’

vs ti-lli-k

’ bet-u ‘his big house’. The plural suffix attaches to the noun: k’on

˚ˇ

o m

@

kin-oc

ˇcˇ

‘pretty cars’ but optionally to the adjective: k’on

˚ˇ

-oc

ˇcˇ m

@

kin-oc

ˇcˇ. The quantifier hullu

‘all’ may follow its noun: s

@

w hullu

‘all the people’.

Adjectives may duplicate their middle consonant, which is followed or not by

ɑ, to

form a plural of

‘variousness’, as in ti-li-lli-k’ li-

˚ˇ

oc

ˇcˇ ‘various big children’ (ti-lli-k’ ‘big’),

r

@

˚ˇ

ɑ

˚ˇ˚ˇ

i-m w

@

tt

ɑdd

@

roc

ˇcˇ ‘various tall soldiers’ (r

@

˚ˇ˚ˇ

i-m

‘tall’). Like nouns these may be

pluralised: r

@

˚ˇ

ɑ

˚ˇ˚ˇ

i-m-oc

ˇcˇ n

ɑcˇcˇ

@

w

‘They are tall (ones)’.

An adjective meaning

‘having particularly or excessively a quality of a noun’ is the

noun suf

fixed by -

ɑm: hod-ɑm ‘greedy, gluttonous’ (hod ‘stomach’), m

@

lk-

ɑm

‘attractive, nice’ (m

@

lk

‘appearance’). An adjective of similar but intensified meaning

has the suf

fix -

ɑmmɑ: fi-rey-ɑmmɑ ‘fruitful’ (fi-re ‘fruit’), t’en-ɑmmɑ ‘healthy’ (t’enɑ

‘health’).

Comparison with an adjective is expressed by a prepositional phrase with k

@

- or t

@

-

‘from’ (t

@

- in northern dialects), as in k

@

-ssu i-ne di-h

ɑ n

@

n

ˇnˇ ‘I am poorer than he’ (lit.

‘from him I am poor’). Adjectives often have cognate verbs with which comparisons

may also be expressed: k

@

-ssu i-ne r

@

˚ˇ˚ˇ

i-m n

@

n

ˇnˇ or k

@

-ssu i-ne i-r

@

zzi-m

ɑll

@

hu

‘I am taller

than he

’ (r

@

zz

@

m

@

‘he grew tall’). Comparisons may be reinforced by a fixed-form

(lacking subject agreement) simple non-past verb such as yi-li-k

’ (l

ɑk’

@

‘he/it surpassed’)

or yi-b

@

lt

’ (b

@

ll

@

t

’

@

‘he/it exceeded’), as in:

h

ɑylu k-ɑnt

@

yi-b

@

lt

’ b

@

t

’

ɑm k’

@

c

ˇcˇ’i-n n

@

w

haylu from-you.Sg.m. more very thin is.he

‘Hailu is much thinner than you.’

A predicative superlative is a comparative in relation to hullu

‘all’: k

@

-hullu i-nn

@

ssu

di-h

ɑ nɑcˇcˇ

@

w

‘they are poorer than all’. Comparatives are discussed below in the section

on syntax.

3.4 Demonstratives

See the demonstratives in Table 35.4; these distinguish singular and plural and near

(proximal) and far (distal). Plural demonstratives consist of the plural pre

fix i-nn

@

- plus

locatives i-zzih

‘here’ and i-zzy

ɑ ‘there’. The demonstratives may be attributive as in yi-h

bet

‘this house’ or pronominal as in y

ɑ n

@

w

‘that’s it’.

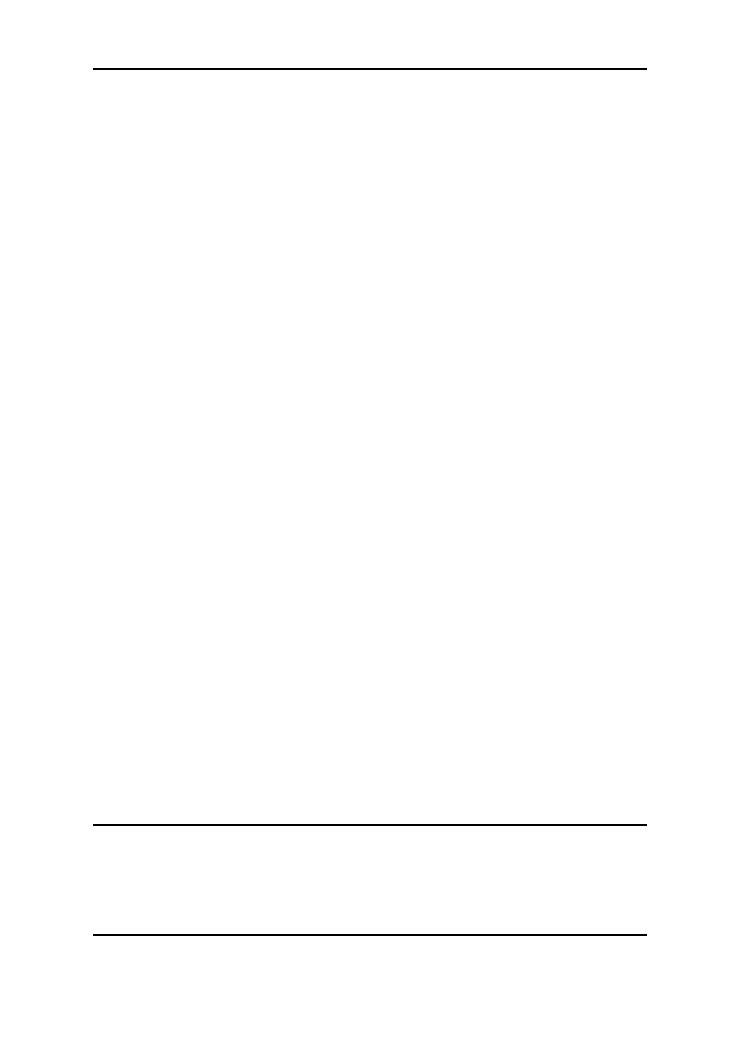

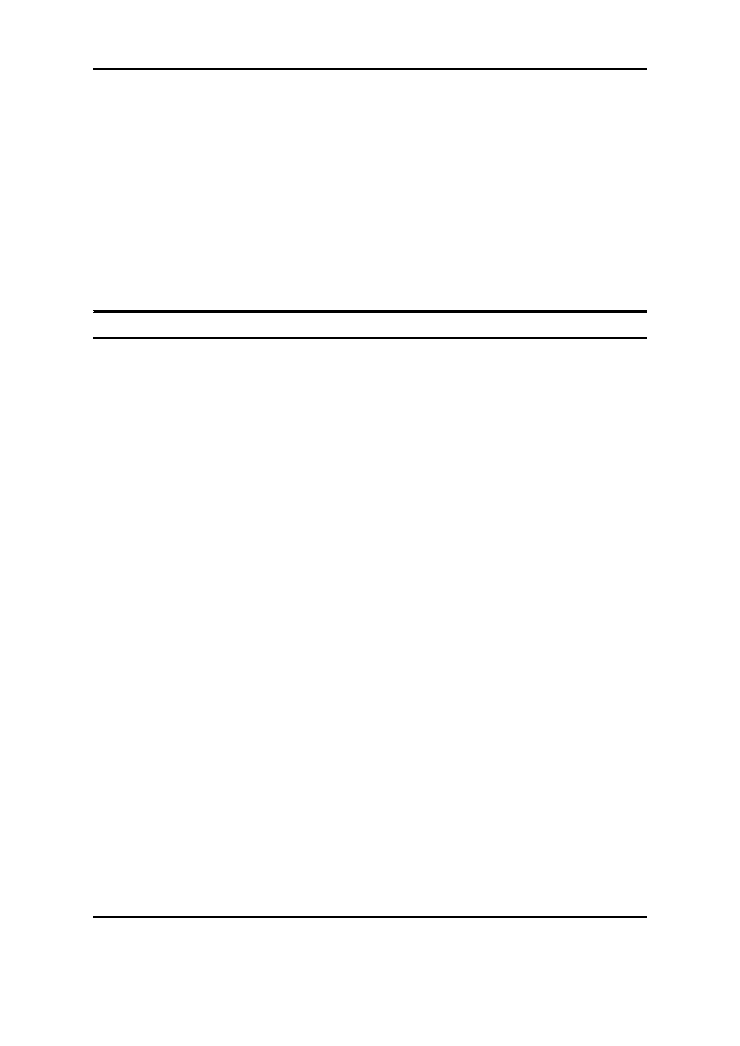

Table 35.4 Demonstratives

Singular

Near

m.

yi-h

f.

yi-(hi-)c

ˇcˇ(i)

Far

m.

y

ɑ

f.

y

ɑcˇcˇ(i)

Plural

Near

i-nn

@

-zzih

Far

i-nn

@

-zzy

ɑ

AMHARIC

601

3.5 Numerals

See cardinal numerals in Table 35.5. Ordinals are the cardinals suf

fixed by -

@

n

ˇnˇ

ɑ (a suffix

which also forms noun agents):

ɑnd-

@

n

ˇnˇ

ɑ ‘first’, hɑyɑ hul

@

t-

@

n

ˇnˇ

ɑ ‘twenty-second’. In royal

titles

‘first’ is k’

@

d

ɑm-ɑwi (root k’

@

dd

@

m

@

‘he preceded’) and ‘second’ d

ɑgm-ɑwi (d

@

gg

@

m

@

‘he repeated’): k’

@

d

ɑmɑwi hɑyl

@

si-ll

ɑsi ‘Haile Sellasie I’, dɑgmɑwi mi-nili-k ‘Menelik II’.

Calendar years are expressed as in

ši z

@

t

’

@

n

ˇ m

@

to si-ls

ɑ sost (thousand nine hundred

sixty-three)

‘nineteen-sixty-three’.

3.6 Verbs

A verb is a stem plus (except in Sg.2m. imperative forms) a subject af

fix, and perhaps

other af

fixes.

3.6.1 Roots and Stems

Semitic verbs are traditionally thought of as consonantal or largely consonantal roots com-

pleted as stems by a pattern of vowels and sometimes additional consonants. Amharic stems

of representative verbs in the four main verb conjugations past, nonpast, imperative, and

conjunct, and the in

finitive, are exemplified in Table 35.6, where hyphens show the place of

obligatory subject suf

fixes (of the past and conjunct conjugations) or prefixes (nonpast).

The 12 verbs are representative of the 12 most common types, which differ by the

structure of their roots. Roots are minimal forms, thus material of the imperative column

less vowels

@

(supplied by verbal grammar) and (epenthetic) i-. Some roots, the B-types,

have long consonants shown as

‘:’ and exemplified by the second verbs of the first

three pairs in Table 35.6.

Consonant length of the historical next-to-last consonant is a characteristic of stems

in the past, and in the nonpast of verbs of the types of -b

ɑr:i-k, -m

@

s

@

k:i-r, and -f

@

n

@

d:

ɑ.

The historical regularity was obscured by loss of the last or next-to-last consonant,

usually leaving a vowel as re

flex. In the column of the past these are the types of k’om,

hed and s

ɑm which lost their next-to-last consonant, the types of b

@

l:

ɑ, l

@

k:

ɑ, and

f

@

n

@

d:

ɑ which lost their last consonant, and the types of k’

@

r:

@

and l

@

y:

@

which lost a

final consonant without leaving a vowel reflex. Verbs whose conjunct and infinitive

stems are augmented by -t are those which lost the

final consonant, for which the t

substitutes. In

finitive stems of Table 35.6 are shown with the infinitive prefix m

@

-.

Table 35.5 Cardinal Numbers

1

ɑnd

12

ɑsrɑ-hul

@

t

2

hul

@

t

20

h

ɑyɑ

3

sost

30

s

@

l

ɑsɑ

4

ɑrɑt

40

ɑrbɑ

5

ɑmmi-st

50

h

ɑmsɑ

6

si-ddi-st

60

si-ls

ɑ

7

s

@

b

ɑt

70

s

@

b

ɑ

8

si-mmi-nt

80

s

@

m

ɑnyɑ

9

z

@

t

’

@

n

ˇ

90

z

@

t

’

@

n

ɑ

10

ɑssi-r

100

m

@

to

11

ɑsr-ɑnd

1000

ši

AMHARIC

602

The 12 verb types have no meaning associations, but B-types tend to be transitive.

The type of b

ɑr:

@

k, with

ɑ after the first consonant, is often termed ‘C-type’. The first-

row triconsonantal type of k

@

f:

@

l is the most numerous. In Shoan or Addis Ababa

Amharic, the conjunct stems of biconsonantal verbs with a back-round vowel characteristic

are k

’om for k’um of the table and hed for hid.

Stems with initial

ɑ: some stems have initial ɑ, the vowel reflex of a lost (pharyngeal or

laryngeal) stem-initial consonant. Table 35.7 shows exemplary

ɑ-initial verbs corresponding

to the types of rows 1

–4 and 11 of Table 35.6.

So-called

‘doubled verbs’ have a repeated consonant in the pattern C

1

C

2

C

2

or

C

1

C

2

C

3

C

3

. Table 35.8 shows exemplary stems of doubled verbs corresponding to the

types of rows 1, 2 and 11 of Table 35.6. The doubled verb characteristic is shown in the

table as repetition of a consonant, not to be confused with long consonants which

characterise stems and shown with

‘:’.

3.6.2 Four Basic Conjugations

The past, nonpast, imperative, and conjunct conjugations are exempli

fied in Tables 35.9

and 35.10, by forms of the root ngr

‘tell’.

In the past, Sg.1 suf

fix -ku and Sg.2.m. suffix -k have forms with h (from historical

spirantisation of k) when the stem ends in a vowel (as so for

five verb types in Table

35.6), for example b

@

ll

ɑ-hu ‘I ate’, k’

@

rr

@

-h

‘you (Sg.2.m.) remained’. But Sg.1 -hu

may also appear after stem-

final consonants: k

@

ff

@

l-hu

‘I paid’, and in Amharic writing

-hu/-h may be written even when -ku/-k is read.

Table 35.7 Verb Stems with Initial

ɑ

Type

Past

Nonpast

Imper.

Conjunct

In

finitive

Gloss

A

ɑl:

@

f-

-

ɑlf

i-l

@

f

ɑlf-

m-

ɑl

@

f

‘pass’

B

ɑd:

@

n-

-

ɑd:i-n

ɑd:i-n

ɑd:i-n-

m-

ɑd:

@

n

‘hunt’

ɑy:

@

-

ɑy

i-y

ɑy-t-

m-

ɑy

@

-t

‘see’

ɑm:ɑ

-

ɑmɑ

i-m

ɑ

ɑm-t-

m-

ɑmɑ-t

‘slander’

ɑn

@

k:

@

s-

-

ɑn

@

k:i-s

ɑnki-s

ɑnki-s-

m-

ɑnk

@

s

‘limp’

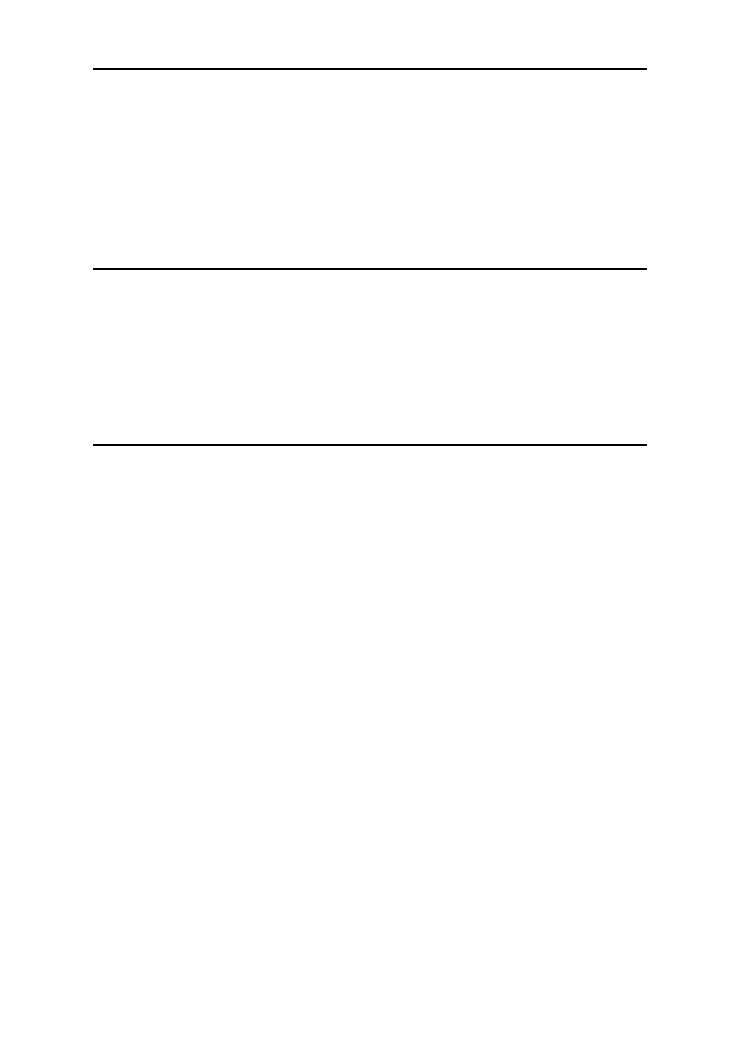

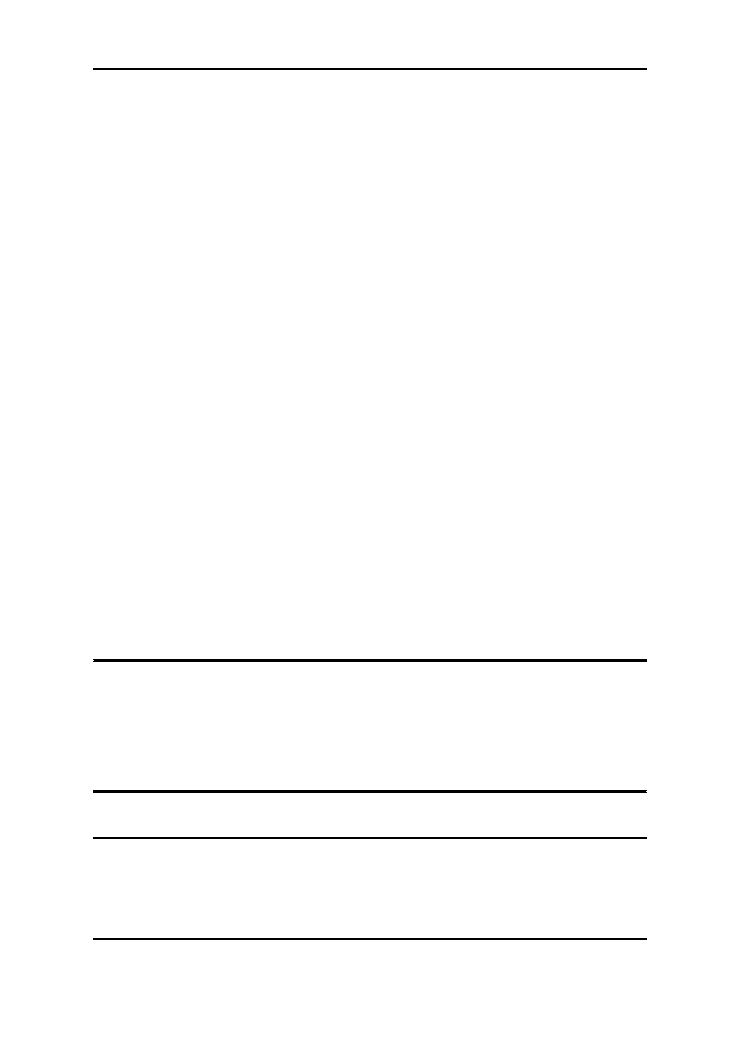

Table 35.6 Verb Stems of 12 Root Types

Type

Past

Nonpast

Imper.

Conjunct

In

finitive

Gloss

A

k

@

f:

@

l-

-k

@

fl

ki-f

@

l

k

@

fl-

m

@

-kf

@

l

‘pay’

B

f

@

l:

@

g-

-f

@

l:i-g

f

@

l:i-g

f

@

l:i-g-

m

@

-f

@

l:

@

g

‘want’

A

k

’

@

r:

@

-k

’

@

r

k

’i-r

k

’

@

r-t-

m

@

-k

’r

@

-t

‘remain’

B

l

@

y:

@

-l

@

y:

l

@

y:

l

@

y:-i-t-

m

@

-l

@

y:

@

-t

‘separate’

A

b

@

l:

ɑ

-b

@

l

ɑ

bi-l

ɑ

b

@

l-t-

m

@

-bl

ɑ-t

‘eat’

B

l

@

k:

ɑ

-l

@

k:

ɑ

l

@

k:

ɑ

l

@

k:-i-t-

m

@

-l

@

k:

ɑ-t

‘measure’

k

’om-

-k

’om

k

’um

k

’um-

m

@

-k

’om

‘stand’

hed-

-hed

hid

hid-

m

@

-hed

‘go’

s

ɑm-

-si-m

s

ɑm

si-m-

m

@

-s

ɑm

‘kiss’

b

ɑr:

@

k-

-b

ɑr:i-k

b

ɑrk

b

ɑrk-

m

@

-b

ɑr

@

k

‘bless’

m

@

s

@

k:

@

r-

-m

@

s

@

k:i-r

m

@

ski-r

m

@

ski-r-

m

@

-m

@

sk

@

r

‘testify’

f

@

n

@

d:

ɑ

-f

@

n

@

d:

ɑ

f

@

nd

ɑ

f

@

nd-i-t-

m

@

-f

@

nd

ɑ-t

‘burst’

AMHARIC

603

The vowel of Sg.1 -ku/-hu is voiceless when word-

final, n

@

gg

@

r-ku

˚

, but is voiced if

an object suf

fix follows: n

@

gg

@

r-ku-t

‘I told him’. Pl.2 -

ɑcˇcˇi-hu reflects a plural suffix

-

ɑcˇcˇ ‘plural’. Stem-final vowels are absent with -u of Pl.3 (and equivalent polite forms),

as in b

@

ll-u

‘they ate’ (< b

@

ll

ɑ-u); otherwise the usual vowel elisions apply: k’

@

rr

@

-

@

>

k

’

@

rr

@

‘he remained’, l

@

kk

ɑ-

@

> l

@

kk

ɑ ‘he measured’.

Verbs of stative and active meaning are interpreted differently in the past: stative

verbs may be understood as present: k

’

@

rr

@

‘he remained ~ he remains’; s

@

kk

@

r

@

‘he

was/got drunk ~ he is drunk

’; whereas actives are past.

Negative past has a pre

fix

ɑl- and, as a main verb, a suffix -m(m): k-ɑl-n

@

gg

@

r-ku

‘if I

don

’t tell’ (minor verb with k- expressing ‘if’ and without -m),

ɑl-n

@

gg

@

r-ni--m

‘we

didn

’t tell’ (main verb).

Table 35.8 Stems of ‘Doubled’ Verbs

Type

Past

Nonpast

Imper.

Conjunct

In

finitive

Gloss

A

b

@

r:

@

r-

-b

@

rr

b

@

rr

b

@

rr-

m

@

-br

@

r

‘fly’

B

d

@

l:

@

l-

-d

@

l:i-l

d

@

l:i-l

d

@

l:i-l-

m

@

-d

@

l:

@

l

‘cajole’

d

@

n

@

g:

@

g-

-d

@

n

@

g:i-g

d

@

ngi-g

d

@

n

@

g:i-g-

m

@

-d

@

ng

@

g

‘decree’

Table 35.9 Past and Nonpast Conjugations

Past

Nonpast

minor verb

Nonpast

main verb

Sg.

1

n

@

gg

@

r-ku

i--n

@

gr

i--n

@

gr-

ɑll

@

hu

2

m.

n

@

gg

@

r-k

ti--n

@

gr

ti--n

@

gr-

ɑll

@

h

f.

n

@

gg

@

r-

š

ti--n

@

gr-i

ti--n

@

gr-i-

ɑll

@

š

pol.

(=Pl.3)

(=Pl.3)

(=Pl.3)

3

m.

n

@

gg

@

r-

@

yi--n

@

gr

yi--n

@

gr-

ɑl

f.

n

@

gg

@

r-

@

c

ˇcˇ

ti--n

@

gr

ti--n

@

gr-

ɑll

@

c

ˇcˇ

pol.

(=Pl.3)

(=Pl.3)

(=Pl.3)

Pl.

1

n

@

gg

@

r-(i-)n

i-n(ni-)-n

@

gr

i-n(ni-)-n

@

gr-

ɑll

@

n

2

n

@

gg

@

r-

ɑcˇcˇi-hu

ti--n

@

gr-u

ti--n

@

gr-

ɑllɑcˇcˇi-hu

3

n

@

gg

@

r-u

yi--n

@

gr-u

yi--n

@

gr-

ɑllu

Table 35.10 Jussive and Conjunct Conjugations

Jussive

Minor verb

conjunct

Main verb conjunct

Sg. 1

li--ng

@

r

n

@

gi-r-:e

n

@

gi-r-:e-

ɑll

@

hu

2

m.

ti--ng

@

r

n

@

gr-

@

h

n

@

gr-

@

h-

ɑl

f.

ti--ng

@

r-i

n

@

gr-

@

š

n

@

gr-

@

š-

ɑl

pol.

(=Pl.3)

(=Pl.3)

(=Pl.3)

3

m.

yi--ng

@

r

n

@

gr-o

n

@

gr-o-(w)

ɑl

f.

ti--ng

@

r

n

@

gr-

ɑ

n

@

gr-

ɑll

@

c

ˇcˇ

pol.

(=Pl.3)

(=Pl.3)

(=Pl.3)

Pl.

1

i-n(ni-)-ng

@

r

n

@

gr-

@

n

n

@

gr-

@

n-

ɑl

2

ti--ng

@

r-u

n

@

gr-

ɑcˇcˇi-hu

n

@

gr-

ɑcˇcˇi-hu-ɑl

3

yi--ng

@

r-u

n

@

gr-

@

w

n

@

gr-

@

w-

ɑl

AMHARIC

604

An object suf

fix pronoun follows the subject suffix and precedes -m: n

@

gg

@

r-

@

c

ˇcˇ-i-h

‘she told you (Sg.m.)’,

ɑl-n

@

gg

@

r-ku-t-i-m

‘I didn’t tell him’.

The nonpast conjugation has subject pre

fixes plus the Sg.2.f. suffix -i and Pl.3 (and

polite form) -u; see Table 35.9, again exempli

fied by ‘tell’ (nonpast stem -n

@

gr).

Nonpast subject pre

fix t- may be geminated when it follows an adverb-clause prefix

such as s-

‘when’ (with which there is epenthesis): s-t-n

@

gr-i > si-t(ti-)n

@

gri

‘when you

(Sg.f.) tell

’. Subject prefix y- after consonants is replaced by i: s-y-hed > sihed ‘when

he goes

’. Stem-final alveolar consonants except r when followed by Sg.2f. suffix -i are

replaced by alveopalatals as discussed in the above section on consonants.

Verbs of stative and active meaning are interpreted differently in the nonpast: active

verbs in the nonpast may be understood as present or future: yi--n

@

gr

‘he tells ~ will

tell

’, whereas statives are only future: yi--s

@

kr

‘he will be (get) drunk’ (or sometimes

habitual present meaning).

Negative nonpasts have a pre

fix

ɑ- and, as main verbs, suffix -m(m): ɑ-y-n

@

gr-i-m

‘he

won

’t tell’, b

ɑ-n(ni-)-n

@

gr

‘if we don’t tell’. Negative nonpast Sg.1 prefix is l- instead of

i-- of the af

firmative:

ɑ-l-hed-i-m ‘I won’t go’. Subject prefix t- is usually lengthened

after the negative pre

fix:

ɑ-tti--n

@

gi-r

‘she doesn’t tell’.

The nonpast af

firmative main verb (except when suffixed by -nn

ɑ ‘and’ in compound

verbs) has auxiliary-verb suf

fixes historically forms of the verb of presence (

ɑl- + suf-

fixes, see below). The final vowel of the Sg.1 auxiliary -

ɑll

@

hu is voiceless when word

final, so this sounds like

ɑll

@

w

˚

. The Pl.2/3 suf

fix -u of the simple nonpast is absent upon

suf

fixation of the plural auxiliary verb, unless Pl.3 (and polite-form) -u is followed by an

object suf

fix, in which case the auxiliary verb is -

ɑl not -ɑllu: for example yi--n

@

gr-u-t-

ɑl

‘they tell him’.

As in the above example, an object pronoun precedes the suf

fixed auxiliary: yi--n

@

gr-

ɑcˇcˇ

@

w-

ɑl ‘he tells them/him.pol.’, i--n

@

gr-i-

š-

ɑll

@

hu

‘I tell you.Sg.f.’.

The imperative(-jussive) conjugation is exempli

fied in Table 35.10, again with ‘tell’

(jussive stem -ng

@

r). The jussive expresses a wish or polite command/request as in yi--mt

’

ɑ

‘let him come’, yi--ng

@

r-i-h

‘may (it be so that) he tell you.Sg.m.’, with 1st and 3rd-

person jussives typically understood as

‘let V’, for example i-nni--hid ‘let us go’. The

jussive is the imperative stem plus pre

fixes and suffixes of the nonpast except that

instead of Sg.1 i-- the jussive has l- (as also in the negative nonpast).

The jussive is absent in minor clauses. Negative jussives like negative nonpasts are

pre

fixed with

ɑ- and, as in the negative nonpast, 2nd-person negative jussives may have

lengthening of subject pre

fix t-:

ɑ-t(ti-)-hid-u ‘don’t go! (Pl.2)’.

Imperatives are 2nd-person jussive stems, respectively ni-g

@

r, ni-g

@

r-i, ni-g

@

r-u (all

having i--epenthesis)

‘tell! (Sg.m., Sg.f., Sg.pol./Pl.)’. Stem-final alveolar consonants of

Sg.2f. have the usual palatalisations as in wi-s

@

˚ˇ

(i)

‘take! (Sg.f.)’ vs wi-s

@

d, Sg.m. The

negative imperative is expressed by 2nd-person negative jussives pre

fixed by nega-

tive

ɑ-, in which 2nd-person subject prefix t- is usually lengthened: ɑ-tti--ng

@

r

‘don’t

tell! (Sg.m.)

’.

The conjunct conjugation (sometimes termed

‘gerundive’ or ‘converb’) is exempli-

fied in Table 35.10, as both minor and main verbs, again with forms of ‘tell’, stem n

@

gr.

The minor-verb conjunct expresses all but the last of a sequence of states or events, the

main verb being of any form, for example k

@

fl-

@

n w

@

tt

’

ɑn ‘they paid and left’ (‘having

paid, they left

’, with main verb in the past), k

@

fl-

@

n i-nni-hed

ɑll

@

n

‘we will pay and go’

(

‘having paid, we will go’, main verb nonpast). Subjects of the conjunct and main verb

need not be the same: s

@

rk

’-o

ɑss

@

r-u-t

‘he having robbed, they imprisoned him’.

AMHARIC

605

The conjunct is a stem and subject suf

fixes. Conjunct stems are similar to but dif-

ferent from those of the nonpast (Table 35.6). A stem-

final consonant is lengthened in

Sg.1 necessitating epenthesis before the long consonant, e.g. n

@

gi-r-:e-w w

@

tt

’

ɑhu ‘I told

him and left

’, which if alveolar other than r has the usual palatalisations, for example

w

@

si-

˚ˇ

-:e

‘I taking’ (stem w

@

sd). Stem augment t is palatalised too: m

@

t

’i-cˇ-:e ‘I coming’

(stem m

@

t

’-t).

The conjunct lacks negative forms except in the Gojjam dialect, in which the negative

conjunct like the past is pre

fixed by

ɑl- and suffixed by -m.

The main-verb conjunct like the main-verb nonpast combines with an auxiliary verb

suf

fix based on the verb of presence to express a past event with still-present effects,

like an English

‘present perfect’: n

@

gr-o-

ɑl ‘he has told’. As in the nonpast, an object

suf

fix precedes the auxiliary verb: n

@

gr-o-n

ˇnˇ-

ɑl ‘he has told me’.

The in

finitive is a deverbal noun, a stem prefixed by m

@

- as in m

@

-ng

@

r gi-dd n

@

w

‘to

tell is a necessity

’, m

@

-hed yi-w

@

dd

ɑl ‘he likes to go’. Where purpose is expressed, the

in

finitive is prefixed by l

@

-: l

@

-m

@

-hed yi-f

@

lli-g

ɑl ‘he wants to go’. In ɑ-initial stems,

@

of

m

@

- is elided: m-

ɑd

@

r

‘to spend the night’, m-

ɑy

@

t

‘to see’. A negative infinitive is pre-

fixed by

ɑl

@

-:

ɑl

@

-m

@

-ng

@

r

‘not to tell’. The infinitive may take the possessive pronoun

suf

fixes (Table 35.3) as subject: m

@

-ng

@

r-w

ɑ ‘her telling’, m

@

-hed-

ɑcˇcˇi-n ‘our going’.

3.6.3 Other Conjugations

Verbs with other aspectual and modal meanings are constructed of one of the above as

main verb plus an auxiliary verb. Some of these are: (1) a

‘past perfect’ for an event in

the past prior to another, which is a minor-verb conjunct with auxiliary verb n

@

bb

@

r: i-ne

s-i--m

@

t

’

ɑ hed-o n

@

bb

@

r

‘When I came, he had gone’, b

@

lt-

@

n n

@

bb

@

r

‘we had eaten’;

(2) for possibility or probability a minor-verb conjunct with nonpast yi--hon-

ɑl (hon

‘become’): k’

@

t

’

@

ro-w-n r

@

si-c

ˇ-:e yi-hon

ɑl ‘I might have (must have) forgotten the

appointment

’ (r

@

ss

ɑ ‘he forgot’); (3) for ‘imminence, an event about to happen’, a

minor verb nonpast pre

fixed by l- with a form of ‘say’ prefixed by s- ‘when’: l-i-hed s-i-l

‘when he was about to go’ (i- of s-i the postconsonantal form of the Sg.3m. y-, and

-l the nonpast stem of

‘say’); (4) for obligation an infinitive with the verb of pre-

sence (below) suf

fixed by -bb- and an object suffix: m

@

bl

ɑt ɑll

@

-bb-i-n

ˇnˇ ‘I have to eat’,

m

@

hed y

@

ll

@

-bb-i-

š-i-m ‘you (Sg.f.) don’t have to go’; (5) for habitual or conditional past

the simple nonpast with n

@

bb

@

r: yi--n

@

gi-r n

@

bb

@

r

‘he used to tell’/‘he would have told’; (6)

for progressive aspect i-yy

@

- pre

fixed to the past plus the copula (for which see below) in

the nonpast and conjugated forms of n

@

bb

@

r in the past: i-yy

@

-f

@

ll

@

g

@

-w n

@

w

‘he is

looking for it

’, i-zziy

ɑ i-yy

@

-s

@

rr-

ɑcˇcˇ n

@

bb

@

r-

@

c

ˇcˇ ‘she was working there’.

3.6.4 The Copula

This is an irregular verb of being, with only the non-past forms seen in Table 35.11. The

copula is a stem n- conjugated with object suf

fixes, except for alternative to Sg.3f. n-

ɑt, with

an object suf

fix, n-

@

c

ˇcˇ with the subject-suffix of the past. In fact n

@

c

ˇcˇ is more common.

The negative nonpast copula is negative pre

fix

ɑy-, the stem d

@

ll

@

(doll

@

in Gojjam

dialect), and suf

fixes of the regular past (Table 35.11). In the past, the be-verb is regular

past forms of n

@

bb

@

r-, for example n

@

bb

@

r-ku

‘I was’, n

@

bb

@

r-k

‘you (Sg.m.) were’, with

regular negatives,

ɑl-n

@

bb

@

r-ku-m

‘I was not’, etc. In the future, the be-verb is regular

nonpast forms of -hon

‘be/become’, for example i--hon ‘I will be’, yi--hon ‘he will be’.

AMHARIC

606

3.6.5 Verb of Presence

There is an irregular verb for locative sentences and presentatives such as

‘there is a _ ’;

see Table 35.12. The stem is

ɑll

@

conjugated as a past although the meaning is present.

The negative nonpast verb of presence as a main verb has the stem y

@

ll

@

with subject

suf

fixes of the past plus -m, as in y

@

ll

@

-hu-m

‘I am not present’. If there are locative

adverbs, the copula may replace the verb of presence: i-zzih n

@

w ~ i-zzih

ɑll

@

‘he/it is

here

’ (or ‘here he/it is’).

In the past the verb of presence and be-verb are nondistinct, for example n

@

bb

@

r-ku

‘I was (present)’, n

@

bb

@

r-k

‘you (Sg.m.) were (present)’. The verb of presence in the

future employs the stem nor (< *n

@

br): yi--nor-

ɑl ‘he/it will be’ (which stem in the past

means

‘reside, live’: i-zzy

ɑ nor-

@

c

ˇcˇ ‘she lived there’).

3.6.6 Possession

Possession is expressed by the verb of presence with object suf

fixes as possessor and

the verb stem ordinarily agreeing in gender and number with the thing(s) possessed:

m

@

kin

ɑ ɑll

@

-n

ˇnˇ ‘I have a car’ (car is-to.me), i-hi-te bi-zu li-

˚ˇ

oc

ˇcˇ

ɑllu-ɑt ‘My sister has many

children

’, i-hi-t

ɑll

@

c

ˇcˇ-i-w ‘he has a sister’. For possession in the past the stem is n

@

bb

@

r

with the object suf

fixes: b

@

k

’i g

@

nz

@

b n

@

bb

@

r-

ɑt ‘she had enough money’. Amharic has

Table 35.11 Copula

Af

firmative

Negative

Sg.

1

n

@

-n

ˇnˇ

ɑy-d

@

ll

@

-hu-m

2

m.

n

@

-h

ɑy-d

@

ll

@

-h-i-m

f.

n

@

-

š

ɑy-d

@

ll

@

-

š-i-m

pol.

n

@

-wot

(=Pl.3)

3

m.

n

@

-w

ɑy-d

@

ll

@

-m

f.

n

@

-c

ˇcˇ ~ n-

ɑt

ɑy-d

@

ll

@

-c

ˇcˇ-i-m

pol.

(=Pl.3.)

(=Pl.3)

Pl.

1

n

@

-n

ɑy-d

@

ll

@

-n-i-m

2

n-

ɑcˇcˇi-hu

ɑy-d

@

ll-

ɑcˇcˇi-hu-m

3

n-

ɑcˇcˇ

@

w

ɑy-d

@

ll-u-m

Table 35.12 Verb of Presence

Af

firmative

Negative

Sg.

1

ɑll

@

-hu

y

@

ll

@

-hu-m

2

m.

ɑll

@

-h

y

@

ll

@

-h-i-m

f.

ɑll

@

-

š

y

@

ll

@

-

š-i-m

pol.

(=Pl.3)

(=Pl.3)

3

m.

ɑll

@

y

@

ll

@

-m

f.

ɑll

@

-c

ˇcˇ

y

@

ll

@

-c

ˇcˇ-i-m

pol.

(=Pl.3)

(=Pl.3)

Pl.

1

ɑll

@

-n

y

@

ll

@

-n-i-m

2

ɑll-ɑcˇcˇi-hu

y

@

ll-

ɑcˇcˇi-hu-m

3

ɑll-u

y

@

ll-u-m

AMHARIC

607

other such

‘impersonal’ verbs, which take as their object the subject of their usual

translation equivalent, including the verbs for being hungry and thirsty: r

ɑb

@

-n

ˇnˇ ‘I am

hungry

’ (it.hungers-me), t’

@

mm-

ɑcˇcˇ

@

w

‘they are thirsty’ (it.thirsts-them).

3.6.7 Derived Verbs

Fully productive are two causatives with pre

fixes

ɑ- and ɑs- and a passive-reflexive

with pre

fix t(

@

)-.

Causatives of intransitive verbs are typically formed with the pre

fix

ɑ-, for example

ɑ-f

@

ll

ɑ ‘he boiled (caused to boil)’ (f

@

ll

ɑ ‘it boiled’); y-ɑ-w

@

dk

’ ‘he makes fall’ (yi--w

@

dk

’

‘he falls’). Some transitives whose meanings involve benefit to the self including ‘eat’,

‘drink’ and ‘dress’ form causatives with

ɑ-: ɑ-b

@

ll

ɑ ‘he caused to eat’, y-ɑ-l

@

bs

‘he

causes (others) to dress

’. Both intransitive and transitive verbs having

ɑ-initial stems

form causatives with

ɑs-, such as ɑs-ɑmm

@

n

@

‘he causes to believe’. Imperative-jussive

and conjunct stems of

ɑ-causative stems of triconsonantal verbs differ from the basic

stem as in

ɑ-ski-r ‘cause to get drunk! (Sg.m.)’ (cf. basic stem si-k

@

r),

ɑ-ski-r-o ‘he,

causing to get drunk

’ (cf. basic s

@

kr-o). The imperative-jussive

ɑ-causative stem of

verbs of the s

ɑm

@

type (Table 35.6) also differs from the basic stem, as in

ɑ-si-m ‘cause

to kiss (Sg.m.)!

’ (basic s

ɑm ‘kiss (Sg.m.)!’).

Causatives, or factitives, of transitive verbs are formed with the pre

fix

ɑs-, for

example

ɑs-g

@

dd

@

l

@

‘he caused to kill’, y-

ɑs-f

@

lli-g

‘it is necessary’ (lit. ‘it causes to

want/seek

’). The

ɑs-causative of an intransitive is an ‘indirect’ causative perhaps with

two agents, for example

ɑs-m

@

tt

’

ɑ ‘he caused someone to bring (something)’ (cf. m

@

tt

’

ɑ

‘he came’ with

ɑ-causative ɑ-m

@

tt

’

ɑ ‘he brought (caused to come)’). Both objects of the

causative verb, if de

finite, are suffixed by the definite object suffix -n. As-causatives of

A-type (non-geminating) stems are formed as B-types, having a long consonant; for

example nonpast

ɑs-causative of A-type root sbr ‘break’ is y-ɑs-s

@

b:i-r, with long b. The

imperative-jussive

ɑs-causative stem of verbs of the sɑm

@

type (Table 35.6) also differ

from the basic stem, as in

ɑs-li-k-u ‘cause to send!’ (cf. basic lɑk ‘send!’).

Passive-re

flexive verbs are formed with the prefix t(

@

)- and stem-changes, for exam-

ple t

@

-b

@

ll

ɑ ‘it is eaten’. See passive-reflexive stems of the nonpast, imperative, and

in

finitive, some different from basic stems, in Table 35.13. Some of these derivatives

express a re

flexive, for example t-

ɑtt’

@

b

@

‘he washed himself’ (

ɑtt’

@

b

@

‘he washed’), or

the intransitive of a transitive, for example t

@

-m

@

ll

@

s

@

‘he returned (vi)’ (m

@

ll

@

s

@

‘he

returned (vt)

’).

Passive-re

flexive nonpast and conjunct stems of A-type (non-geminating) verbs are

formed as B-types, with a long consonant, for example, the nonpast t-passive of A-type

root kft

‘open’ is yi--k:

@

f:

@

t

‘it is opened’, with long f of the B-type. In the nonpast the

stem-initial consonant is long as the result of assimilation of the passive pre

fix t, thus

yi--k:

@

f:

@

t < yi--tk

@

f:

@

t. Re

flexive-passive t- of a nonpast, jussive, or infinitive of a verb

with initial

ɑ is lengthened, as in yi--tt-ɑmm

@

n

‘it is believed’, m

@

-tt-

ɑl

@

f

‘to be passed’.

A derived verb expressing reciprocity has the pre

fix t(

@

)- and the vowel

ɑ after the

first stem consonant: t

@

-n

ɑgg

@

ru

‘they conversed (told to each other)’ (n

@

gg

@

r

@

‘he

told

’), t

@

-m

ɑttu ‘they hit each other’ (m

@

tt

ɑ ‘he hit’). This derivative may also express a

habitual, as in t

@

b

ɑll

@

‘he habitually ate’ (b

@

ll

ɑ ‘he ate’). The causative of this derivative

is an adjutative (

‘help to V’) as in

ɑ-ffɑll

@

g

@

‘he helped to seek’ (f

@

ll

@

g

@

‘he sought,

wanted

’),

ɑ-wwɑll

@

d-

@

c

ˇcˇ ‘she helped to give birth (as midwife)’ (w

@

ll

@

d-

@

c

ˇcˇ ‘she gave

birth

’), the stem-initial long consonant resulting from assimilation of t-.

AMHARIC

608

Some verbs with

ɑ-initial basic stems take the compound prefix ɑs-t- to form a causative

of the passive:

ɑs-t-ɑww

@

k

’

@

‘he notified, announced’ (

ɑww

@

k

’

@

‘he knew’),

ɑs-t-ɑrr

@

k

’

@

‘he reconciled’ (t-

ɑrr

@

k

’u ‘they were reconciled’).

A derived verb expressing repetition and attenuated action has reduplication of the

historical next-to-last consonant preceded by stem-vowel

ɑ, for example sɑsɑm

@

‘he

kissed repeatedly/a little

’ (s

ɑm

@

‘he kissed’), n

@

k

ɑkkɑ ‘he repeatedly/barely touched’

(n

@

kk

ɑ ‘he touched’).

There are so-called

‘defective verbs’, which lack basic stems and occur only as a

derivational type, for example, in the absence of verbs d

@

rr

@

g

@

or k

’

@

mm

@

t

’

@

there are

ɑ-d

@

rr

@

g

@

‘he did’, t

@

-d

@

rr

@

g

@

‘it was done’,

ɑs-k’

@

mm

@

t

’

@

‘he put, placed’, and

t

@

-k

’

@

mm

@

t

’

@

‘he was seated (seated himself)’. A non-productive prefix n- appears in a

number of defective verbs, especially quadriconsonantal and reduplicatives, always

with one of the pre

fixes

ɑ- or t-, for example t

@

-n-b

@

r

@

kk

@

k

@

‘he knelt’,

ɑ-n-s’

@

b

ɑrr

@

k

’

@

‘it glittered’.

3.6.8 Denominal Verbs

Verbs may be derived from nouns, though not freely, by abstracting the consonants of

the noun and assigning the resulting consonantal root to a verb type, often B-type, for

example from m

@

rz

‘poison (n.)’ yi--m

@

rri-z

‘he poisons’ (with long r), and from cˇ’

ɑmmɑ

‘shoes’ t

@

-c

ˇ

ɑmmɑ ‘put on shoes’.

3.6.9 ‘Say-verbs’

A peculiarity of Ethiopian languages and especially Amharic is verbs consisting of an

often seemingly ideophonic word with a

final long consonant and a conjugated form of

the verb

‘say’ (with forms

ɑl

@

‘he said’ yi--l ‘he says’, b

@

l

‘say!’, bi-l-o ‘he saying’, m-

ɑl

@

-t

‘to say’), for example bi-kk’

ɑl

@

‘he appeared’, k’ucˇcˇ’

ɑl

@

‘he sat down’, and zi-mm

ɑl

@

‘he was quiet’. Transitive verbs employ ‘do’ instead of ‘say’: bi-kk’

ɑd

@

rr

@

g

@

‘he caused to

appear

’, li-bb

ɑdi-rg ‘look out!’ Two somewhat productive derivations of ‘say’ compound

verbs are an attenuative exempli

fied by w

@

dd

@

kk

’

ɑl

@

‘he fell a little’, and an intensive

exempli

fied by wi-di-kk’

ɑl

@

‘he fell hard’, both derived from the root wdk’ ‘fall’.

Table 35.13 Reflexive-passive Stems of Verbs of the 12 Types

Nonpast

Imperative

In

finitive

Gloss

-k:

@

f:

@

t

t

@

-k

@

f

@

t

m

@

-k:

@

f

@

t

‘be opened’

-f:

@

l:

@

g

t

@

-f

@

l

@

g

m

@

-f:

@

l

@

g

‘be sought’

-f:

@

˚ˇ:

t

@

-f

@

˚ˇ

m

@

-f:

@

˚ˇ

@

-t

‘be consumed

-l:

@

y:

t

@

-l

@

y

m

@

-l:

@

y

@

-t

‘be separated’

-b:

@

l:

ɑ

t

@

-b

@

l

ɑ

m

@

-b:

@

l

ɑ-t

‘be eaten’

-l:

@

k:

ɑ

t

@

-l

@

k

ɑ

m

@

-l:

@

k

ɑ-t

‘be measured’

-s:

ɑm

t

@

-s

ɑm

m

@

-s:

ɑm

‘be kissed’

-

š:om

t

@

-

šom

m

@

-

š:om

‘be appointed’

-g:et

’

t

@

-get

’

m

@

-g:et

’

‘be adorned’

-b:

ɑr:

@

k

t

@

-b

ɑr

@

k

m

@

-b:

ɑr

@

k

‘be blessed’

-m:

@

z

@

g:

@

b

t

@

-m

@

zg

@

b

m

@

-m:

@

zg

@

b

‘be recorded’

-z:

@

r

@

g:

ɑ

t

@

-z

@

rg

ɑ

m

@

-z:

@

rg

ɑ-t

‘be stretched’

AMHARIC

609

4 Syntax

4.1 Basic Word Order

The verb is

final in its clause with rare exception (cleft sentences, below), for example:

t

@

m

ɑri-w t’i-yyɑk’e t’

@

yy

@

k

’

@

student-the question asked.he

‘the student asked a question’

Typically, the subject is

first in its clause (SOV), as above, but when the verb object is

de

finite and topicalised (or backgrounded) this usually precedes the subject, in which

case the verb has a

‘resumptive’ object pronoun suffix, for example:

yi-h-i-n w

@

mb

@

r yoh

ɑnni-s s

@

rr

ɑ-w

this-Obj chair Yohannes made.he-it

‘Yohannes made this chair’

A clause-initial instrumental prepositional phrase is similarly resumptively expressed as

a suf

fix on the verb.

b

@

-m

@

t

’r

@

giy

ɑ-w seti-yye-wɑ bet-u-n t’

@

rr

@

g-

@

c

ˇcˇ-i-bb-

@

t

with-broom-the woman-the house-the-Obj swept-she-with-it

‘the woman swept the house with a broom’

Interrogative pronouns are not fronted but are preverbal: yoh

ɑnni-s mi-n n

@

gg

@

r

@

‘What

(mi-n) did Yohannis say?

’, li-

˚ˇ

oc

ˇcˇu l

@

mi-n y

ɑl

@

k

’s

ɑllu ‘Why (l

@

mi-n) do the children cry?

’

4.2 Yes

–No Questions

These may have rising intonation or less often sentence-

final question words i-nde

‘really?’, w

@

y, or the literary archaic verb suf

fix -ni-; for example

ɑster ti-hedɑl

@

c

ˇcˇ w

@

y,

ɑster

ti-hed

ɑl

@

c

ˇcˇ i-nde,

ɑster ti-hedɑl

@

c

ˇcˇ-i-ni- ‘Will Aster go?’ A one-word ‘reprise’ question has

the clause-

final suffix -ss:

ti-hed

ɑlli-h (w

@

y)

–

ɑwon. ɑncˇi-ss

‘Will you (Sg.2m.) go? – Yes. And you (Sg.2f.)?’

4.3 Noun Phrases

The head noun is typically

final in its phrase: t’i-ru m

@

ls

‘a good answer’, y-

ɑbbɑte ɑddis

m

@

kin

ɑ ‘My father’s new car’. In a few idioms borrowed from or modelled on Ge‘ez,

this order is reversed and

@

is suf

fixed to the head noun: bet

@

m

@

s

’

ɑhi-ft ‘library’ (lit.

‘house-of books’), bet

@

m

@

ngi-st

‘palace’ (lit. ‘house-of government’).

4.4 Prepositions

Frequent prepositions include b

@

-

‘at, on’, i-- ‘at, in’, l

@

-

‘for’, k

@

-

‘from’ (t

@

- in northern

dialects), si-l

@

-

‘about’, i-nd

@

-

‘like’ (the latter two may be written as separate words),

AMHARIC

610

and w

@

d

@

‘to, towards’ (always a separate word). Some positional relations are expres-

sed with postpositional words historically nouns, including l

ɑy ‘top’, wi-st’ ‘interior’, fit

‘face’ and h

w

ɑlɑ ‘back’, for example ɑlgɑ lɑy ‘on the bed’, hod wi-st’ ‘in the belly’.

Sometimes postpositions co-occur with prepositions, for example (b

@

-)bet wi-st

’ ‘in the

house

’, k

@

-ssu b

@

-

fit ‘in front of him’, k

@

-ne b

@

-h

w

ɑlɑ ‘after/behind me’.

4.5 Coordination

Nouns are coordinated with -nn

ɑ suffixed to the next-to-last: bɑl-i-nnɑ mist ‘husband and

wife

’, s

@

w-i-nn

ɑ set ‘man and woman’. Verbs may be coordinated with -nnɑ if the verb

suf

fixed by -nn

ɑ is a past, minor-verb nonpast or imperative: t

@

n

@

ssu-nn

ɑ w

@

tt

’u ‘they got

up and left

’, yi-m

@

t

’

ɑ-nnɑ yɑyɑl ‘he will come and see’, hid-i-nnɑ i-y ‘go (Sg.m.) and see!’

Alternatives are coordinated with w

@

y suf

fixed by -m(m) in statements (-m(m) the

historical contrastive-topicalising suf

fix) and -ss in questions (-ss the contrast-question

suf

fix): i-zzih w

@

y-m i-zzy

ɑ ‘here or there’, i-zzih w

@

y-ss i-zzy

ɑ ‘here or there?’ Alternatives

may be simply juxtaposed: m

@

hon

ɑl

@

-m

@

hon

‘to be or not to be’. Coordinated clauses

are usually expressed by use of conjunct verbs, which need no conjunction, for exam-

ple b

@

lto t

’

@

tt

’

ɑ ‘he ate and drank’, t’wɑt w

@

t

’i-cˇcˇe m

ɑtɑ d

@

rr

@

sku

‘I left in the morning

and arrived in the evening

’. Contrast clauses are coordinated with gi-n, n

@

g

@

r gi-n, or

(somewhat literary) d

ɑru gi-n ‘but’: m

@

tt

’

ɑhu gi-n ɑlb

@

ll

ɑhum ‘I came but I didn’t eat’.

4.6 Adjective (Relative) Clauses

These precede the noun they modify, and y

@

- (identical to the possessive pre

fix of

nouns) is pre

fixed to the verb in the past and y

@

-mm- in the nonpast. In Gojjam dialect

the pre

fix for nonpast verbs may be simply m- and in Menz and Wello dialects i-mm-,

the latter also seen in old Amharic literature.

b

@

-sid

ɑmo y

@

-t

@

g

@

n

ˇnˇ

@

h

ɑwlt

in-Sidamo Rel-was.found.it statue

‘a statue which was found in Sidamo’

si-l

@

-tege t

’

ɑytu y

@

mm-i-n

@

gi-r t

ɑrik

about-Empress Taitu Rel-it-tell history

‘history which tells about Empress Taitu’

If the head noun of an adjective clause is object of a preposition

‘on/at’ (b

@

-) or

‘for’

(l

@

-), this appears as a pronoun suf

fixed to -bb- or -ll-, respectively, within the verb:

yi-h y

@

-t

@

-w

@

ll

@

d-ku-bb-

@

t bet n

@

w

this Rel-Pas-born-I-in-it house is

‘this is the house I was born in’

If the clause is object of a preposition, the verb of the clause may be pre

fixed by the

preposition in which case the relative verb pre

fix y

@

- is absent: si-l

@

-t

’

ɑytu b

@

-mm-i-n

@

gi-r

m

@

s

’i-h

ɑf ‘in a book which tells about Taitu’. In the dialect of Gojjam and in old

Amharic literature, the plural verb of an adjective clause may take the noun-plural

suf

fix -ocˇcˇ, for example y

@

-m

@

tt

’-ocˇcˇ s

@

w-oc

ˇcˇ ‘people who came’.

AMHARIC

611

For cleft sentences, also constructed with relative verbs, see below.

4.7 Noun Clauses

These may be formed on the verb in the nonpast, where the noun-clause and main-clause

subjects are the same, with verb-pre

fix l-:

l-i-w

@

sd-

ɑcˇcˇ

@

w

ɑ-l-f

@

ll

@