Journal of Workplace Learning

Emerald Article: Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for

the firm

Kristien Van Laere, Aime´ Heene

Article information:

To cite this document: Kristien Van Laere, Aime´ Heene, (2003),"Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the

firm", Journal of Workplace Learning, Vol. 15 Iss: 6 pp. 248 - 258

Permanent link to this document:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13665620310488548

Downloaded on: 31-08-2012

References: This document contains references to 72 other documents

Citations: This document has been cited by 10 other documents

To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

This document has been downloaded 1842 times since 2005. *

Users who downloaded this Article also downloaded: *

David C. Li, "Online social network acceptance: a social perspective", Internet Research, Vol. 21 Iss: 5 pp. 562 - 580

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10662241111176371

Hui Chen, Miguel Baptista Nunes, Lihong Zhou, Guo Chao Peng, (2011),"Expanding the concept of requirements traceability: The role

of electronic records management in gathering evidence of crucial communications and negotiations", Aslib Proceedings, Vol. 63

Iss: 2 pp. 168 - 187

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00012531111135646

François Des Rosiers, Jean Dubé, Marius Thériault, (2011),"Do peer effects shape property values?", Journal of Property

Investment & Finance, Vol. 29 Iss: 4 pp. 510 - 528

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14635781111150376

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by KATOLICKI UNIWERSYTET LUBELSKI JANA PAWLA II

For Authors:

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service.

Information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit

www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

With over forty years' experience, Emerald Group Publishing is a leading independent publisher of global research with impact in

business, society, public policy and education. In total, Emerald publishes over 275 journals and more than 130 book series, as

well as an extensive range of online products and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 3 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is

a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive

preservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

Social networks as a

source of competitive

advantage for the firm

Kristien Van Laere and

Aime Heene

Introduction

Over the past 20 years, strategies which focus

on the economic consequences of firms

participating in networks have been

increasingly researched. More recently,

research on strategic blocks (Garcia-Pont and

Nohria, 1998), strategic supplier networks

(Jarillo, 1988), learning in alliances (Prahalad

and Hamel, 1990), inter-firm trust (Gulati

1995; Zaheer and Venkatraman 1995), and

network resources (Gulati, 1999) has

examined inter-firm relationships from a

variety of theoretical perspectives, levels of

analysis and outcomes (Gulati et al., 2000).

This growing research tradition in the

strategic management field attests to the

importance of inter-actor relationships.

The sum of the external contacts of a firm is

its social or informal network (Gulati, 1999).

Such a network contains all relations with

other organisations ± customers, suppliers,

competitors and other entities ± of all possible

industries and countries. Social networks may

facilitate inter-firm exchange but they can also

involve certain disadvantages. Hence,

managers need to have a profound insight

into all the elements of social networks so that

they can take an active role in managing inter-

actor ties and developing collaborative

capabilities that recognize both opportunities

and costs in embedded relations (Uzzi, 1996).

Social embeddedness matters to

organisations, because it often appears that

firms do not have to own resources in order to

reap the benefits from exploiting them

(Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978; Sanchez et al.,

1996; Dierickx and Cool, 1989; Frooman

1999). Insights from structural sociology

(Granovetter, 1985; Uzzi, 1997; Burt, 1992)

suggest that access to competitively valuable

resources is a function of the social network in

which the firm operates. Social networks are

an important source of externally controlled

resources, especially when the required

resources are highly specialized and can

therefore not be obtained through the market

(Heugens and Zyglidopoulos, 2001).

Scholars have suggested that participation

in social networks can be influential in

providing actors with access to timely

information and referrals to other actors in

the network (Burt, 1992). Especially for small

and medium-sized firms (SMEs) with a

comparable small amount of resources and

competencies, social networks can offer

The authors

Kristien Van Laere is an Assistant and Aime Heene is a

Professor, both in the Department of Management and

Organisation, Faculty of Economics and Business

Administration, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium.

Keywords

Social networks, Competitive advantage,

Strategic management, Small to medium-sized enterprises,

Competitive strategy, Network operating systems

Abstract

Globalisation is transforming the competitive environment

of small and medium-sized firms.Because these firms are

competing with their larger counterparts in an economy

where collaboration is increasingly central to

organisational effectiveness, one must pay more attention

to the social networks that organisations rely on.This

article focuses on the relational perspective and describes

the characteristics of embedded relationships that firms

have to pay attention to in order to survive.

Electronic access

The Emerald Research Register for this journal is

available at

http://www.emeraldinsight.com/researchregister

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is

available at

http://www.emeraldinsight.com/1366-5626.htm

248

Journal of Workplace Learning

Volume 15 . Number 6 . 2003 . pp.248-258

# MCB UP Limited . ISSN 1366-5626

DOI 10.1108/13665620310488548

strong opportunities for a balanced enterprise

development in a competitive environment

(Jarillo, 1988; Ring and Van de Ven, 1994;

Sanchez et al., 1996). The ability to be part of

a social network has often been cited as a

source of competitive advantage for people

and organisations alike.

The first aim of this article is to propose a

conceptual framework covering the core

issues in managing relationships of SMEs in

function of their survival. We started from the

proposition that small and medium-sized

firms need to cooperate in order to survive.

An organisation functions as a system of

interdependent actors who collectively share

some goals for creating and realizing value

through their interactions. As an open system,

the firm has to interact with the environment

in order to survive. To attract interested

actors to its activities, thereby assuring its

continued existence, an organisation must

pay attention to the relationships it has.

Second, the article focuses on a particular

way of thinking about the embedded

relationships of SMEs starting from a

relational perspective. Conclusions are drawn

about how suitable this way of analyzing

SMEs and their embedded relationships is for

further research.

Small and medium-sized firms

Competition today increasingly revolves

around globalisation. In the more segregated

competitive arenas of the past, managers of

smaller firms could remain local if they

wished, reasonably insulated from the forces

of international competition. If they chose to

expand into markets abroad, they could

acquire and internalise the resources needed

to do so incrementally over time. In the new,

intensified competitive environment, with

higher customer expectations, rapid

technological change and environmental

regulations, SMEs must define excessive and

different purposes to survive, whether or not

they actually compete globally. As a

consequence, it is increasingly difficult for

independent, small firms to survive and/or to

grow unless they are globally competitive.

Even if SMEs are faced with high

competition, current interest in small

manufacturing firms is still enormous because

they are an important source of job growth.

Small and medium-sized firms capture an

important place in the Belgian economy.

More than 97 per cent of all firms in Belgium

are small or medium-sized (Van Gils, 2000).

Moreover, SMEs are responsible for a large

percentage of the gross national product and

of national employment (Van Gils, 2000).

Among researchers in small business, small

firms are not considered simply to be ``smaller

copies of big ones'' and there is a recognized

need for concepts of strategic management

that address the special characteristics and

situations of small firms (Borch and Huse,

1993; Dandridge, 1979). SMEs are

characterized by diversity, small scale,

personality and independence (Nooteboom,

1994). According to Van Gils (2000), each of

these characteristics lies at the basis of

important strengths such as flexibility,

motivation, customisation and unique

competences, but also of some weaknesses,

like lack of functional expertise, diseconomies

of scale and little spread of risks.

Flexibility to adapt quickly to

environmental changes, for example, is cited

as an important advantage of smaller firms.

Many small firms, however, find themselves

in positions in which larger intermediary firms

are the only firms that come in direct contact

with end-user markets (Bonaccorsi, 1993). As

small firms lack contact with end-user

markets, good market information, necessary

for identifying future opportunities and for

the creation of competence, does not reach

them and puts larger firms in a powerful

position based on superior information and

expertise (French and Raven, 1959; Stern and

El-Ansary, 1992).

The perceived disadvantages of small firms

versus larger firms often seem to outweigh the

perceived advantages of small firms (Sanchez

et al., 1996). Limited possibilities of economies

of scale, for example, give small firms cost

disadvantages. Small firms also suffer from

limited management resources. Small, single

firms (within fragmented industries) will rarely

have an R&D department, a marketing

department for developing a national or

international profile, well controlled

distribution channels or the financial strength

to launch long-term programmes. Small firms

are often more affected by a wider range of

environmental factors and environmental

changes than larger firms.

To exploit the main strengths and to

overcome the weaknesses, SMEs typically

pursue an innovation or niche strategy. Many

249

Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

Kristien Van Laere and Aime Heene

Journal of Workplace Learning

Volume 15 . Number 6 . 2003 . 248-258

small firms may maintain their positions in

specific market niches, when these markets are

unattractively small for bigger companies or

when competition in a niche does not depend

importantly on larger companies' sources of

competitive advantage (Grant, 1991).

Need to cooperate with others

Many SMEs try to address the increasing

pressure of globalisation and rising customer

requirements with cost cutting programmes

and concentration on core competencies

(Prahalad and Hamel, 1990). At the same

time, these enterprises are forced to protect

their long-term competitive capability, to find

new benefit potentials, and to get into

promising positions. Like their large

counterparts, SMEs need to concern

themselves with their market position, their

technological trajectories, their competence

building and their organisational processes.

Especially for SMEs with a comparably

small amount of resources and competencies,

cooperating with other firms is a very

promising strategy which can resolve the

apparent contradiction between ``shrinking to

fit'' and expanding into new markets (Hamel et

al., 1989; Kogut, 1988; Lorange and Roos,

1992). Through cooperation, a small or

medium-sized firm may have possibilities to

access necessary assets outside the firm, which

points to firm-addressable assets (Sanchez et

al., 1996). Cooperative relationships can help

SMEs gain new competences, conserve

resources and share risks, move more quickly

into new markets, and create attractive options

for future investments (Hamel et al., 1989;

Hennart, 1991; Ohmae, 1989; Doz, 1996;

Kogut, 1991).

Thus, it would be appropriate to state that

companies, and especially SMEs, increasingly

compete through cooperation; the familiar

model of the single, independent,

autonomous company is dying out. Strategic

alliances are becoming an essential feature of

companies' overall organisational structure,

and competitive advantage increasingly

depends not only on a company's internal

capabilities but also on the types of its

alliances and the scope of its relationships

with other companies. Being a good partner,

which depends on the duration and objectives

of the relationships, has become a key

corporate asset. Moreover, according to

Kanter (1994), a good partnership is a

collaborative advantage and a genuine ability

to establish and sustain fruitful collaboration

gives companies a significant competitive

advantage.

In order to survive

Many of a company's relationships are vital

for its continuing competitive survival, and

each relationship may involve a substantial

commitment of resources that cannot be

easily used elsewhere. A company's decisions

on what action to take in each relationship are

of great importance to the development of its

overall portfolio of relationships and its

competitive success.

For the purpose of this paper we claim that

a company develops its own relationships and

we see these relationships as tools used by the

company. This way of examining the interface

between the company and the relationships is

a typical managerial approach and it points to

the importance of a company's development

of its relationships (Sanchez et al., 1996).

The stakeholder management rationale

envisions organisations at the centre of a

network of stakeholders. A firm's stakeholders

are any group of individuals who can affect or

are affected by the firm (Freeman, 1994),

including its investors, suppliers, employees,

customers, competitors, local communities in

which it operates, regulatory agencies and so

on.

A common perspective found in the

stakeholder literature is that organisations are

vehicles for coordinating stakeholder interests

(Freeman, 1994). This perspective is based

on the notion that organisations are, by

nature, cooperative systems (Lando et al.,

1997; Barnard, 1938). As a result of their

cooperative nature, organisations are inclined

to form coalitions with stakeholders to

achieve common objectives (Axelrod et al.,

1995). These coalitions are variously referred

to as constellations and (strategic) networks

(Jarillo, 1988; Borgatti, 1997). These

cooperative relationships can be a powerful

mechanism for aligning stakeholder interests

and can also help a firm reduce environmental

uncertainty (Kraatz and Zajac, 1998). SMEs

have to pay attention to the relationships with

their stakeholders to safeguard their

continuity.

Strategic management and the ``circle of

continuity''

Strategic management theory, developed on

the base of classical economic theory, will

250

Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

Kristien Van Laere and Aime Heene

Journal of Workplace Learning

Volume 15 . Number 6 . 2003 . 248-258

proclaim ``the maximization of shareholder

value'' as the firm's main objective.

Competence-based strategic management

theory complements this traditional view with

a holistic perspective and redefines the firm's

primary objective as ``mediating between the

multiple interests of the firm's stakeholders''

to guarantee the sustainability of the firm's

processes of value creation and distribution.

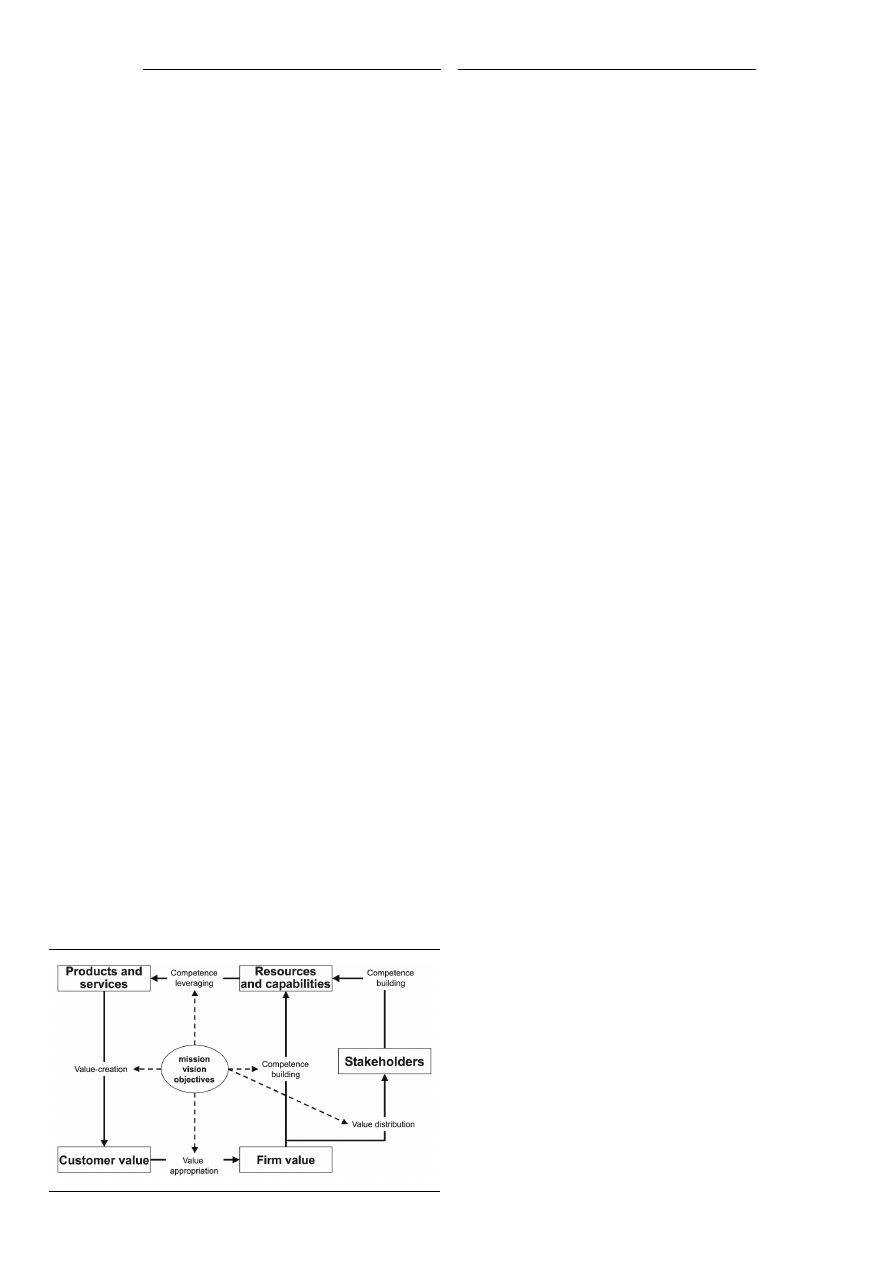

To answer the question what an

organisation needs to do in order to safeguard

its longevity, we propose the ``circle of

continuity'' (Figure 1):

.

Step 1: Competence leveraging[1]: form and

content of product design, product

development, production and product

offering in the market are the result of the

way a company uses its resources,

structures and processes. A company's

resources are ultimately considered the

``sources of products and services''.

Conversely, products are an ``external

translation'' of the resources a company

can put to use.

.

Step 2: Value creation: products or services

allow the organisation to serve the

customer's needs and preferences. It is

only when the customer perceives the

firm's offering as ``valuable'' that he will

be willing to use and to pay for the firm's

offerings.

.

Step 3: Value appropriation: the results of

value creation need to be appropriated by

the value creating firm. Appropriating is

the capacity of the firm to retain the

added value it creates for its own benefit.

Who benefits from the firm's success in

adding value depends partly on the

decisions of the firm, partly on the

structure of the markets and partly on the

sources of the added value (Kay, 1993).

Powerful clients, who confront the firm

with a list of demands and who have

furthermore a strong negotiating position,

could obstruct the supplier to appropriate

the rewards of his efforts for value

creation.

.

Step 4: Value distribution and

step 5: Competence building, allow the firm

to develop stakeholders and in that way

tap new resources or reorganise the

existing resources.

In most cases the distribution or

division of added value is a matter of

agreement or decision, not legislation.

According to Kay (1993) two factors are

critical in determining the way in which

added value is divided between various

stakeholders. One is the degree to which

any or all of them have contributed to the

achievement of the added value. The

other is their (negotiating) power.

Firm value distribution enables the

company to obtain new resources or to

qualitatively change existing resources.

These in turn are the source of new

products and services. Customer value

creation and sustaining competitive

advantage thus requires a balance

between building and leveraging

competences. For the first activity, we

argue that relationships with stakeholders

are the necessary condition to renew

resources, structures and processes. In

function of competence leveraging one

can argue that good relationships can

result in working together to create,

produce and deliver products and services

to customers.

The mission, vision and goals of a firm,

inspire all the decisions taken within the

framework of the circle of continuity. These

elements give direction to the way the

different components in the circle of

continuity have to be developed and

deployed.

Following the reasoning in the continuity

circle, the capacity to collaborate is becoming

a core competence of an organisation (Doz

and Hamel, 1998). SMEs have to develop

partnerships with those stakeholders who are

essential for their survival and, more

specifically, with those actors who possess

information and other resources they are not

able to get without them.

Figure 1 The circle of continuity

251

Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

Kristien Van Laere and Aime Heene

Journal of Workplace Learning

Volume 15 . Number 6 . 2003 . 248-258

Despite their promise, partnerships fail to

meet expectations because little attention is

given to nurturing the close working

relationships and interpersonal connections

that unite the partnering organisations (Hutt

and Stafford, 2000). Economic theories of

exchange virtually ignore the role of people

and their importance in the management of

interorganisational relations (Weitz and Jap,

1995).

The goal for SMEs is clearly to achieve a

balance in which the firm maintains good

relations with its stakeholders, and yet

diversifies products and sales. This balance is

not easy to strike, considering the investment

in time, expertise and resources that goes into

good relations with stakeholders. Therefore,

we take into consideration in the following

section the relational perspective and draw

some conclusions for SMEs.

The relational perspective

The industry structure view, associated with

Porter (1980), suggests that supernormal

rents are primarily a function of a firm's

membership in an industry with favourable

structural characteristics (e.g. relative

bargaining power, barriers to entry and so

on). Consequently, many researchers have

focused on the industry as the relevant unit of

analysis. The resource-based view (RBV) of

the firm argues that differential firm

performance is fundamentally due to firm

heterogeneity rather than to industry

structure (Barney, 1991; Rumelt, 1984;

Wernerfelt, 1984).

Although these two perspectives have

contributed greatly to our understanding of

how firms achieve above-normal returns, they

overlook the important fact that the

(dis)advantages of an individual firm are often

linked to the (dis)advantages of the network

of relationships in which the firm is

embedded. Proponents of the RBV have

emphasized that competitive advantage

results from those resources and capabilities

that are owned and controlled by a single

firm. Consequently, the search for

competitive advantage has focused on those

resources that are housed within the firm.

Recently, however, an alternative

perspective has become available ± one that

holds that the search for value-creating

resources and capabilities should be extended

beyond the boundaries of the firm (Dyer and

Singh, 1998; Gulati, 1999; Gulati et al., 2000;

Sanchez et al., 1996). Heugens and

Zyglidopoulos (2001) labelled this

perspective, which traces the sources of

competitive advantage to the network of a

firm's relationships, the relational

competence perspective.

The importance of a firm's internal

resources is widely accepted in the strategy

literature in general (Barney, 1991; Manoney

and Pandian, 1992) and the competitive

dynamics literature in particular (Smith and

Grimm, 2000). According to Gnyawali and

Madhavan (2001) we consolidate four sets of

arguments to establish that resources also

reside in the firm's social network and are

important to a firm. First, relationships in a

network are potential conduits to internal

resources held by connected actors (Nohria,

1992). Second, external economies ± that is,

``capabilities created within a network of

competing and cooperating firms'' ± often

complement firms' internal resources

(Langlois, 1992). Third, the rate of return on

internal resources is determined by how well

structured the firm's network is (Burt, 1992).

And fourth, a firm's position in a network

contributes to its acquisition of new

competitive capabilities (McEvily and Zaheer,

1999), which, in turn, enhances its ability to

attract new ties (Powell et al., 1996).

Gulati (1999) refers to the sources of value-

creating resources and capabilities that extend

beyond the boundaries of the firm, as

``network resources''. Thus, from the novel

perspective on the RBV, an important source

for the creation of inimitable value-generating

resources lies in a firm's network of

relationships. And any evaluation of the

relational perspective necessarily starts with

the recognition of embedded relationships as

an important locus of competitive advantage

(Dyer and Singh, 1998; Zajac and Olsen,

1993).

Embedded relationships

Based on the transaction cost economy

(Williamson, 1985), Uzzi (1997) argued that

the relationships that a firm has with its

surrounding organisations could be

summarised in two categories: ``market

relationships'' and ``close, special or

embedded relationships''. Market

relationships, or ``arm's-length ties'', are

characterized by a lack of reciprocity, a lack of

252

Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

Kristien Van Laere and Aime Heene

Journal of Workplace Learning

Volume 15 . Number 6 . 2003 . 248-258

social content, the non-repeated nature of the

interaction and a narrow focus on economic

matters. The vast majority of any

organisational field's activities involve arm's-

length ties. But market transactions may fail

and that's why embedded relationships can be

so important. Much of embeddedness

research seeks to demonstrate that market

exchange is embedded in, and defined by,

larger and more complex social processes

(Granovetter, 1985; Zukin and DiMaggio,

1990; Portes and Sensenbrenner, 1993).

Mintzberg (1979) has demonstrated that even

the most formal organisations have an

``informal'' nature based on friendship,

personal ties, and strategically negotiated

inter-firm coalitions and ties.

While scholars developing the resource-

based perspective have highlighted the

importance of social factors, no attention has

been given to network resources that emerge

from firms' participation in the network of

embedded relationships.

From a relational perspective, it is precisely

the ``special or embedded relationships''

between firms that are of interest, because

even though they are fewer in number, they

usually characterize the critical exchange

relationships of the firm (Uzzi, 1997). Uzzi

(1997) showed further that embedded

relationships have three main components or

characteristics that regulate the expectations

and behaviours of exchange partners, notably

trust, fine-grained information transfer and

joint problem-solving arrangements.

According to Heugens and Zyglidopoulos

(2001) we add durability and collaboration

under the broader notion of incorporate joint

problem-solving arrangements.

SMEs have to pay attention to their

embedded relationships in order to survive.

Following what is explained in the circle of

continuity, we argue that a firm's

relationships with stakeholders are the

necessary condition to renew resources,

structures and processes. The manager-owner

of a firm has to analyze the firm's position in

terms of its specific relationships and its own

and other's resources, rather than in terms of

a set of products, markets and competitors.

Personal relationships provide an alternative

route for resolving conflicts and form the basis

of an informal understanding that clarifies the

commitments made by the parties (Hutt and

Stafford, 2000).

Embedded relationships between SMEs

and their counterparts

Embedded relationships must develop and

supplement formal relationships. Frequent

and more personal interactions with large

firms, who are often the top-customers of

SMEs, can resolve conflict, build trust, speed

decision-making and uncover new

possibilities for the partnership.

Taking the difficult position of SMEs in the

intensified competitive environment into

account, one can argue that these firms have

to pay special attention to their critical

exchange relationships with other firms.

Many of a company's customer or supplier

relationships are vital for its continuing

competitive survival and each may involve a

substantial commitment of resources that

cannot be easily used elsewhere. Taking the

characteristics of embedded relationships,

which regulate the expectations and

behaviour of exchange partners, into account,

we present the relationships between SMEs

and their large counterparts.

Trust

Actors in a network gradually build

dependency on resources controlled by others

in the network and position themselves to

make future use of these resources (Johanson

and Mattsson, 1987). An increased mutual

dependency and adaptation is heavily

dependent on the parallel creation of trust

between the firms: ``Single exchanges are in

this case integral parts of a process in which

the parties gradually build up a mutual trust

in each other. In supplier-customer

relationships for instance, business exchange

is an important aspect of this social exchange

process'' (Johanson and Mattsson, 1987).

Uzzi (1997) found that trust is the most

important feature of embedded ties. Trust in

interorganisational relationships is generated

by the reciprocation of special efforts on

behalf of both parties ± in other words, by the

exchange of favours. Trust acts like a heuristic

device enabling firm members to make quick

decisions and process more complex

information than would be possible without

trust (Uzzi, 1997). Both the enhanced speed

of decision-making and the improved ability

to handle complex information are posited to

have a significant positive impact on the

development of competitively valuable

competences.

253

Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

Kristien Van Laere and Aime Heene

Journal of Workplace Learning

Volume 15 . Number 6 . 2003 . 248-258

The partners within a network must rely on

each other to share unforeseen benefits and

costs of the exchange. Such mutual trust can

be achieved through the extension of

exchange relations to incorporate deeper

personal commitments among the

participants. Shared values, norms,

interpersonal affiliation and respect, that have

been found important to help the single firm

cope with increased complexity and

uncertainty, need now to be extended to

inter-firm contractual relations (Macneil,

1980). Relation-based coordination can

reduce uncertainty, and thereby the

transaction costs associated with inter-firm

exchange (Jarillo, 1988; Williamson, 1986).

This is of special importance when it comes to

high investments in one specific relation. In a

competitive environment a firm needs to

beware of opportunistic action from its

exchange partner: it may be impossible to

predict all the conditions under which a

contract will have to be carried out, or to

know precisely all the specifications a piece of

equipment will have to meet (Borch and

Arthur, 1995).

Because of complexity and turbulence, the

formalized, legal contract is not sufficient to

coordinate and control such transactions.

Within transaction-cost economics,

ownership and internal control are

recommended as a solution to the uncertainty

and opportunism problems (Williamson,

1985). Smaller business firms lack market

power for negotiation, and formal hierarchy

may be antagonistic towards the advantages

of a simple, organisational structure such as

flexibility and short communication lines.

Informal networks may be particularly suited

to these kinds of firms by creating a

transaction-cost efficient and supportive

environment (Borch and Huse, 1993; Golden

and Dollinger, 1993).

Smaller firms have relatively simple organic

structures, and an oral, direct management

style anchored in the behavior of the leader

(Dandridge, 1979; Mintzberg, 1983).

Because of these characteristics, high-trust

person-centered governance structures may

be more important in small firms than in

larger corporations (Dubini and Aldrich,

1991) and may be similarly emphasized in

small firms' external relations.

Durability

Because trust between SMEs and their larger

counterparts cannot be generated

immediately, a certain degree of durability in

the relationship between the two parties is

required. Therefore, one of the characteristics

of embedded relationships between firms, in

contrast to market relationships, is that they

tend to be of much longer duration (Heugens

and Zyglidopoulos, 2001). In combination

with trust, durability enhances the relational

evolution of competences because it promotes

the willingness of managers to make

relationship-specific investments that are

necessary to build competitively valuable

competences (Dyer, 1997). When a durable

relation is established, predictability will be

enhanced and the uncertainty about

commitment of the other actors will decrease

(Dubini and Aldrich, 1991).

Many small or medium-sized firms'

customer or supplier relationships are vital for

their continuing competitive survival, and

each may involve a substantial commitment

of resources that cannot be easily used

elsewhere.

Because SMEs often produce special

products, do custom work, respond to

changing specifications, make complex

negotiation orders, and fill orders on short

notice, this business, more than others, lies

under competition. SMEs have to supply

special rather than standard products and do

custom work; in the mean time they have to

maintain good and enduring relations with

their top large-firm customers. Achieving a

balance between those two tasks is an

important subject for SMEs and a continued

investment in good relationships is of high

importance.

It takes some time before a sequence of

interactions can be labelled as an effective and

durable personal relationship. Because of the

great importance to the development of their

overall portfolio of relationships and its

competitive success, SMEs have to think

twice on what decisions they will take in each

relationship.

Besides, SMEs have to consider the concept

durability in terms of their strategy. Often

SMEs have only a short time perspective and

are in general just concentrated on

performing everyday operations (Bennis,

2001; Van Gils, 2000). Because of a lack of

vision for the long run, they need to be

254

Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

Kristien Van Laere and Aime Heene

Journal of Workplace Learning

Volume 15 . Number 6 . 2003 . 248-258

conscientious about the durability of the

relationships they have.

Fine-grained information transfer

Duration of relationships, in combination

with trust, reflects the strength of using

learning effects and built-in skills for mutual

benefits. Trust is developed over time and

there must be a certain level of trust before

any deeper learning can take place. Herewith

we arrive at explaining the third characteristic

of embedded relationships, more specific fine-

grained information transfer (Uzzi, 1997).

Fine-grained information transfers benefits

between networked firms by allowing learning

from one another and allows them to

communicate and interpret tacit information

in a relatively holistic way (Uzzi, 1997;

Larson, 1992).

According to Heugens and Zyglidopoulos

(2001) this kind of fine-grained information

transfer impacts the relational evolution of

competences in at least two ways. First, it

sheds benefits on the firm by increasing its

behavioural options and its predictive

capacity (Uzzi, 1997). Secondly, since

competences are characterized by a large tacit

component (Sanchez et al., 1996), fine-

grained information transfer facilitates the

interorganisational learning, which is essential

for competence evolution to occur (Hamel

et al., 1989).

Because SMEs are characterized by the use

of tacit knowledge, they have to take care in

their relationships with others, to interchange

exact and clear information in order to get the

partner in an enduring relation. An overly

restrictive information policy will damage

trust, hamper learning and impede the

development of interpersonal relationships

across organisations. Frequent interactions

and the timely exchange of information across

organisations resolve conflict, build trust,

speed decision-making and uncover new

possibilities for the partnership (Hutt et al.,

2000).

Collaboration

Following what Heugens and Zyglidopoulos

(2001) have proposed, we discuss the last

characteristic of special or embedded

relationships: the extensive inter-firm

collaboration (Gray, 1989). Uzzi (1997)

found that embedded ties accommodate

actors with problem-solving mechanisms that

enable them to coordinate interactions and

work out problems. These arrangements

typically consist of routines of negotiation and

mutual adjustment that flexibly resolve

problems. Joint problem-solving

arrangements are mechanisms of voice (Uzzi,

1997). One can argue that people are more

likely to use voice rather than exit in response

to problems.

In that sense it is very important for SMEs

to make their complaints known and to

negotiate over them, rather than withhold

them. They have to search within their

relationship to find a solution. But also the

other way around is very important: SMEs

have to accommodate their embedded

relationships with possibilities of problem-

solving. They have to replace the simplistic

exit-or-stay response of the market and enrich

the network, because working through

problems promotes learning and innovation

(Uzzi, 1997). Collaboration between firms

often leads to exciting and rewarding results

which none of the participants could achieve

on their own.

Being a good partner in embedded

relationships has become a key corporate

asset. We can call it a company's collaborative

advantage. And as we move further into an

economy where collaboration is increasingly

central to organisational effectiveness, we

must pay more attention to the sets of

relationships that organisations rely on.

Conclusion

Globalisation creates imperatives for firms to

consider participating in networks and to

reflect upon the strategic importance of social

networks for the firm. Networks have become

crucial to the competitive success of SMEs in

the fast-changing and highly competitive

global markets. The ability of SMEs to own or

control assets or resources is normally more

restricted than for large firms. More than

ever, many of the skills and resources essential

to SMEs' prosperity lie outside the firm's

boundaries. That is why the capacity to

collaborate is becoming a core competence of

an organisation. SMEs have to develop

embedded relationships with these

stakeholders who are essential for their

survival.

We began this article developing a

contextual framework to explain the

importance of cooperation for the survival of

small and medium-sized firms. Then starting

255

Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

Kristien Van Laere and Aime Heene

Journal of Workplace Learning

Volume 15 . Number 6 . 2003 . 248-258

from a relational perspective we described the

characteristics of embedded relationships

which SMEs have to be aware of while

interacting with their stakeholders.

The most interesting finding was a

considerable and growing research tradition

in the strategic management literature that

focuses on inter-firm networks. This attests to

the importance of inter-actor relationships

generally within the conversation of strategic

management, and highlights the need for

coalescing and focusing the research in this

area.

Further research that explores the

characteristics of the embedded relationships

between firms and their stakeholders is

necessary to propose rules to firms on how to

behave in their relationships with their

stakeholders. Relatively little theory has been

advanced in the empirical realm which relates

to how managers actually deal with the

relationships with their stakeholders. We

suggest that an extensive research should be

undertaken to study how firms should react

on and manage the expectations and

behaviours of exchange partners. What is the

interplay between trust and durability on the

one hand and joint problem-solving on the

other hand within relationships? How

extended must the interchange of information

be? Or when do firms have a collaborative

advantage through cooperation?

Embedded networks offer competitive

advantages for SMEs. This implies that future

research also might examine how markets

function and competitive dynamics unfold

when organisations compete on the basis of

their ability to access and reconfigure an

external pool of resources and partners rather

than firm-based competences.

Note

1 The circle of continuity is a ``closed'' circle, in which

every element is at the same time cause and effect.

There is no starting or ending point.``Step 1'' means

in this context that we will start with this step for

pedagogical reasons, but it is by no means meant to

represent a hierarchy.

References

Axelrod, R., Mitchell, W., Thomas, R.E., Bennett, D.S. and

Bruderer, E.(1995), ``Coalition formation in

standard-setting alliances'',

Management Science,

Vol.41, pp.1493-513.

Barnard, C.(1938),

The Functions of the Executive,

Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Barney, J.B. (1991), ``Firm resources and sustained

competitive advantage'',

Journal of Management,

Vol.17, pp.99-120.

Bennis, W.(2001), ``Big or small?'',

Executive Excellence,

Vol.18 No.6, pp.7-10.

Bonaccorsi, A.(1993), ``What do we know about

exporting by small Italian manufacturing firms'',

Journal of International Marketing, Vol.1 No.3,

pp.49-75.

Borch, O.J. and Arthur, M.B. (1995), ``Strategic networks

among small firms: implications for strategy

research methodology'',

Journal of Management

Studies, Vol.32 No.4, pp.419-42.

Borch, O.J. and Huse, M. (1993), ``Informal strategic

networks and the board of directors'',

Entrepreneurship.Theory & Practice, Vol.18,

pp.23-36.

Borgatti, S.P. (1997), ``Clique centrality'', working paper,

Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA.

Burt, R.S. (1992),

Structural Holes: The Social Structure of

Competition, Harvard University Press, Cambridge,

MA.

Dandridge, T.C. (1979), ``Children are not little grown-ups.

Small business needs its own organizational

theory'',

Journal of Small Business Management,

Vol.2.

Dierickx, I.and Cool, K.(1989), ``Asset stock accumulation

and sustainibility of competitive advantage'',

Management Science, Vol.12.

Doz, Y.(1996), ``The evolution of cooperation in strategic

alliances: initial conditions or learning processes'',

Strategic Management Journal, Vol.17, pp.55-83.

Doz, Y.L. and Hamel, G. (1998),

Alliance Advantage,

Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Dubini, P.and Aldrich, H.(1991), ``Personal and extended

networks are central to the entrepreneurial

process'',

Journal of Business Venturing, Vol.6,

pp.305-13.

Dyer, J.H. (1997), ``Effective interfirm collaboration: how

firms minimize transaction costs and maximize

transaction value'',

Strategic Management Journal,

Vol.18, pp.535-56.

Dyer, J.H. and Singh, H. (1998), ``The relational view:

cooperative strategy and sources of

interorganizational competitive advantage'',

Academy

of Management Review, Vol.23, pp.660-79.

Freeman, R.E. (1994),

Ethical Theory and Business,

Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

French, J.R.P. and Raven, B. (1959), ``The basis for social

power'', in Sanchez, R., Heene, A. and Thomas, H.

(Eds),

Dynamics of Competence-based Competition,

Elsevier Science Ltd, Oxford.

Frooman, J.(1999), ``Stakeholder influence strategies'',

Academy of Management Review, Vol.24 No.2,

pp.191-206.

Garcia-Pont, C.and Nohria, N.(1998), ``Local versus

global: the dynamics of alliance formation in the

automobile industry'',

Strategic Management

Journal.

Gnyawali, D.R. and Madhavan, R. (2001), ``Cooperative

networks and competitive dynamics: a structural

256

Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

Kristien Van Laere and Aime Heene

Journal of Workplace Learning

Volume 15 . Number 6 . 2003 . 248-258

embeddedness perspective'',

Academy of

Management Review, Vol.26 No.3, pp.431-46.

Golden, P.A. and Dollinger, M. (1993), ``Cooperative

alliances and competitive strategies in small

manufacturing firms'',

Entrepreneurship; Theory &

Practice, Vol.17 No.4, pp.43-57.

Granovetter, M.(1985), ``Economic action and social

structure: the problem of embeddedness'',

American

Journal of Sociology, Vol.91, pp.481-510.

Grant, R.B. (1991), ``The resource-based theory of

competitive advantage: implications for strategy

formulation'', in Sanchez, R.and Heene, A.and

Thomas, H.(Eds.),

Dynamics of Competence-based

Competition, Vol.3, Elsevier Science Ltd, Oxford.

Gray, B.(1989),

Collaborating: Finding Common Ground

for Multiparty Problems, Jossey-Bass,

San Francisco, CA.

Gulati, N.(1999), ``Network location and learning: the

influence of network resources and firm capabilities

on alliance formation'',

Strategic Management

Journal, pp.397-420.

Gulati, N.and Zaheer, A.(2000), ``Strategic networks'',

Strategic Management Journal, pp.203-15.

Gulati, R.(1995), ``Does familiarity breed trust? The

implications of repeated ties for contractual choice

in alliances'',

Academy of Management Journal,

Vol.38, pp.85-112.

Hamel, G., Doz, Y. and Prahalad, C.K. (1989), ``Collaborate

with your competitors and win'',

Harvard Business

Review, Vol.89 No.1, pp.133-9.

Hennart, J.(1991), ``The transaction costs theory of joint

ventures: an empirical study of Japanese

subsidiaries in the United States'',

Management

Science, Vol.37, pp.483-97.

Heugens, P.and Zyglidopoulos, S.C.(2001),

Embedded

Competences? The Value-added of a Relational

Resource-based Perspective.

Hutt, M.D. and Stafford, E.R. (2000), ``Defining the social

network of a strategic alliance'',

Sloan Management

Review, Vol.41 No.2, pp.51-63.

Hutt, S., Walker and Reingen (2000), ``Defining the social

network of a strategic alliance'',

MIT Sloan

Management Review, pp.51-62.

Jarillo, J.C. (1988), ``On strategic networks'',

Strategic

Management Journal, Vol.9, pp.31-41.

Johanson, J.and Mattsson, L.G.(1987),

``Interorganizational relations in industrial systems:

a networks approach compared with the

transaction-cost approach'',

International Studies of

Management & Organization, Vol.17, pp.34-48.

Jones, T.M., Hesterly, W.S. and Borgatti, S.P. (1997), ``A

general theory of network governance: exchange

conditions and social mechanisms'',

Academy of

Management Review, Vol.22, pp.911-45.

Kay, J.(1993),

Foundations of Corporate Success: How

Business Strategies Add Value, Oxford University

Press, Oxford.

Kogut, B.(1988), ``Joint ventures: theoretical and

empirical perspectives'',

Strategic Management

Journal, Vol.9, pp.310-32.

Kogut, B.(1991), ``Joint ventures and the option to

expand and acquire'',

Management Science, Vol.37,

pp.19-23.

Kraatz, M.S. and Zajac, E.J. (1998), ``How organizational

resources affect strategic change and performance

in turbulent environments: theory and evidence'',

working paper, J.L. Kellogg Graduate School,

Evanston, IL.

Lando, A.A., Boyd, N.G. and Hanlon, S.C. (1997),

``Competition, cooperation and the search for

economic rents: a syncretic model'',

Academy of

Management Review, Vol.22, pp.110-41.

Langlois, R.N. (1992), ``External economics and economic

progress: the case of the microcomputer industry'',

Business History Review, Vol.66 No.1, pp.31-41.

Larson, A.(1992), ``Network dyads in entrepreneurial

settings: a study of the governance of exchange

relationships'',

Administrative Science Quarterly,

Vol.37, pp.76-104.

Lorange, P.and Roos, J.(1992),

Strategic Alliance:

Formation, Implementation and Evolution,

Blackwell, Oxford.

McEvily, B.and Zaheer (1999), ``Bridging ties: a source of

firm heterogeneity in competitive capabilities'',

Strategic Management Journal, Vol.20 No.12,

pp.1133-57.

Macneil, I.R. (1980),

The New Social Contract: An Inquiry

into Modern Contractual Relations, Yale University

Press, New Haven, CT, and London.

Manoney, J.T. and Pandian (1992), ``The resource based

view within the conversation of strategic

management'',

Strategic Management Journal,

Vol.13, pp.363-80.

Mintzberg, H.(1979),

The Structuring of Organizations,

Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Mintzberg, H.(1983),

Structure in Fives: Designing

Effective Organizations, Prentice-Hall, Englewood

Cliffs, NJ.

Nohria, N.(1992), ``Is a networks perspective a useful way

of studying organizations?'', in Nohria, N.and

Eccles, R.G. (Eds),

Networks and Organizations:

Structure, Form and Action, Harvard Business

School Press, Boston, MA.

Nooteboom (1994), ``Innovation and diffusion in small

firms: theory and evidence'', in Van Gils, A.E.J. (Ed.),

Cooperative Behavior in Small and Medium-sized

Enterprises: The Role of Strategic Alliances.

Ohmae, K.(1989), ``The global logic of strategic

alliances'',

Harvard Business Review, Vol.67,

pp.143-54.

Pfeffer, J.and Salancik, G.(1978),

The External Control of

Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective,

Harper & Row, New York, NY.

Porter, M.E. (1980),

Competitive Strategy: Techniques for

Analyzing Industries and Competitors, Free Press,

New York, NY.

Portes, A.and Sensenbrenner, J.(1993), ``Embeddedness

and immigration: notes on the social determinants

of economic action'',

American Journal of Sociology,

Vol.98, pp.1320-50.

Powell, W.W., Koput, K.W. and Smith-Doerr, L. (1996),

``Interorganizational collaboration and the locus of

innovation: networks of learning in biotechnology'',

Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol.41, pp.116-45.

Prahalad, C.K. and Hamel, G. (1990), ``The core

competence of the corporation'',

Harvard Business

Review, Vol.68, pp.79-91.

Ring, P.S. and Van de Ven, A.H. (1994), ``Developmental

processes of cooperative interorganizational

relationships'',

Academy of Management Review,

Vol.19, pp.90-118.

257

Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

Kristien Van Laere and Aime Heene

Journal of Workplace Learning

Volume 15 . Number 6 . 2003 . 248-258

Rumelt, R.P. (1984), ``Towards a strategic theory of the

firm'', in Lamb, R.B. (Ed.),

Competitive Strategic

Management, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ,

pp.556-71.

Sanchez, R., Heene, A.and Thomas, H.(1996),

Dynamics

of Competence-based Competition: Theory and

Practice in the New Strategic Management, Elsevier

Science Ltd, Oxford.

Smith, Y.G. and Grimm, K.G. (2000), ``Multimarket contact

and resource dissimilarity: a competitive dynamics

perspective'',

Journal of Management, Vol.26 No.6,

pp.1217-37.

Stern, L.W. and El-Ansary (1992), ``Marketing channels'',

in Sanchez, R., Heene, A. and Thomas, R.E. (Eds),

Dynamics of Competence-based Competition,

Elsevier Science Ltd, Oxford.

Uzzi, B.(1996), ``The sources and consequences of

embeddedness for the economic performance of

organizations: the network effect'',

American

Sociological Review, Vol.61, pp.674-98.

Uzzi, B.(1997), ``Social structure and competition in

interfirm networks: the paradox of embeddedness'',

Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol.42 No.1,

pp.35-67.

Van Gils, A.E.J. (2000),

Cooperative Behavior in Small and

Medium-sized Enterprises: The Role of Strategic

Alliances, Rijksuniversiteit, University

Press, Groningen.

Weitz, B.A. and Jap, S.D. (1995), ``Relationship marketing

and distribution channels'', in Hutt, M.D. and

Stafford, E.R. (Eds),

Defining the Social Network of

a Strategic Alliance, Sloan Management Review,

Vol.41.

Wernerfelt, B.(1984), ``A resource-based view of the

firm'',

Strategic Management Journal, Vol.5,

pp.171-80.

Williamson, O.(1985), ``The economic institutions of

capitalism'', unpublished manuscript, New York,

NY.

Williamson, O.(1986),

Economic Organization.Firms,

Markets, and Policy Control, New York University

Press, New York, NY.

Zaheer, A.and Venkatraman, N.(1995), ``Relational

governance as an interorganizational strategy: an

empirical test of the role of trust in economic

exchange'',

Strategic Management Journal, Vol.16,

pp.373-92.

Zajac, E.J. and Olsen, C.P. (1993), ``From transactional cost

to transactional value analysis: implications

for the study of interorganizational strategies'',

Journal of Management Studies, Vol.30,

pp.131-45.

Zukin, S.and DiMaggio, P.(1990),

Structures of Capital:

The Social Organization of the Economy, Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, MA.

258

Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

Kristien Van Laere and Aime Heene

Journal of Workplace Learning

Volume 15 . Number 6 . 2003 . 248-258

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Accounting Recording and Firm Reporting as Source of Information for Users to Take Economic Decision

Emotion Work as a Source of Stress The Concept and Development of an Instrument

Kołodziejczyk, Ewa Literature as a Source of Knowledge Polish Colonization of the United Kingdom in

23 Contact as a Source of Language Change

Hutter, Crisp Implications of Cognitive Busyness for the Perception of Category Conjunctions

Vlaenderen A generalisation of classical electrodynamics for the prediction of scalar field effects

Validation of a test battery for the selection of call centre operators in a communications company

Rewicz, Tomasz i inni Isolation and characterization of 8 microsatellite loci for the ‘‘killer shri

Evaluation of HS SPME for the analysis of volatile carbonyl

British Patent 2,812 Improvements in Methods of and Apparatus for the Generation of Electric Current

Canadian Patent 29,537 Improvements in Methods of and Apparatus for the Electrical Transmission of P

Basic Principles Of Perspective Drawing For The Technical Illustrator

Energetic and economic evaluation of a poplar cultivation for the biomass production in Italy Włochy

Reading Price Charts Bar by Bar The Technical Analysis of Price Action for the Serious Trader Wiley

THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL NETWORK SITES ON INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION

the state of organizational social network research today

Grosser et al A social network analysis of positive and negative gossip

social networks and the performance of individualns and groups

więcej podobnych podstron