1

Elżbieta Płóciennik, Ph. D.

Departament of Pre-school and Early – learning Pedagogy

Faculty of Educational Sciences

the University of Lodz

Dynamic Picture in Advancement of Early Childhood Development

Published in: Sobczak, A., Znajmiecka – Sikora M. (eds.), 2012, Development in the

perspective of the human science – opportunities and threats, Lodz: Wydawnictwo UŁ, (pp.

115-128)

The beginning of school education marks the opening of a pivotal chapter in every

person’s life, a period which affects further success or failure in adulthood. It is from school

and their families that young people acquire knowledge and abilities which enable them to

accomplish their future goals successfully.

The educational atmosphere, as well as social and material conditions, constitute the most

significant factors which contribute to the positive development of an individual. The

educational atmosphere ought to be based on friendliness and the acceptance of the individual

skills, capabilities, interests and needs of every person. Such an atmosphere encourages not

only shaping and maintaining high self-esteem and self-confidence based on major as well as

minor accomplishments, but also a successful development and acquiring more and more

complex abilities. It also encourages the differentiation of requirements and motivation. This in

turn stimulates an individual’s high activity and enables individual capabilities to be utilized in

the educational process.

However, not every individual is a success at school and in life up to the standards of

their own potential and developmental capabilities. Such is the case of the underachievement

syndrome. Significantly, the basis and the main cause of this problem, which affects intelligent

and gifted individuals, does not lie in the lack of abilities. It lies in the lack of opportunity to

utilize those abilities for various reasons.

1. Underachievement syndrom

The underachievement syndrome is often confined only to the school environment. There

it takes the form of a discrepancy between student’s grades or school behaviour, and his or her

high potential, intelligence and creativity assessed through standardized testing and the

2

opinions of teachers and parents (Ekiert-Grabowska, 1994). As pedagogical research shows,

the underachievement syndrome can affect up to 10% of the student population (Karpińska,

2002).

The underachievement syndrome is believed to be caused by the following activators:

educational methods, school organization, social environment at school and certain attitudes of

teachers. These can include the preference for imitative rather than creative students, the

promotion of conformity and convergence skills, and the suppression of initiative,

independence and the originality of thinking by using traditional and verbal methods of

teaching (sf.: Wiechnik, 1987; Dyrda, 2007). On the basis of my own observations and

experience I can find the same factors (either activating or escalating the problem of

underachievement or suppressing the natural activity of a child) in the kindergarten

environment unless the process of education follows the rules of support, inclusion, integration

and comprehensive development.

A school grade can be also an activating factor of the underachievement syndrome. A

nominal grade, as opposed to a supporting assessment or a formative assessment, may lower

student’s motivation to learn if it is unfair, if its main goal is to criticize the student in front of

the class, or if it is overused and utilized as an educational or statistical measure. What is more,

a traditional (nominal) grade usually indicates the extent of student’s inability to perform

certain tasks or lack of certain knowledge. Such a situation necessitates focusing on student’s

mistakes and failure rather than accomplishments and success. What is more, the nominal

grade does not constitute a component of an appropriate pedagogical diagnosis-it does not

reflect student’s skills and capabilities and does not indicate his or her problems. As a result,

the planning of any therapeutic and compensatory actions, which are aimed at filling in the

gaps of knowledge and practical skills, are significantly hampered. According to B. Niemierko

(2002), the system of grading students’ educational achievements is the most neglected field of

didactics and makes following generations question the validity and objectivity of nominal

assessment. And it is the lack of objectivity that leads to students’ low self-esteem and

disrespect for both the teacher and the students’ responsibilities.

Although nominal grades are not used in kindergartens, there still is a problem of the

correct assessment of a child’s achievements in accordance with his or her abilities and skills.

The assessment should be based on systematic and accurate diagnosis of the child’s

competences made by a teacher through observation, registering and analysis of the child’s

behaviour in all the fields of his or her skills and activities. Nevertheless, such assessment

should not only aim at informing the child about his or her abilities and skills, but first of all it

3

should help to develop educational process taking into account of operational aims and

monitoring the child’s progress, his or her self-esteem, being active and involved in achieving

further competences.

Self-confidence and self-acceptance play a key role in the processes of building self-

esteem and motivation to overcome learning difficulties because they shape students’

behaviour in task situations, their motivation and the effort they put into working. For that

reason, they also affect carrying out school responsibilities and learning success. Low self-

esteem can also influence student’s non-school interpersonal relationships, satisfying safety

and identity needs, as well as the attitude towards new situations and reluctance to take risk. As

a result, student’s aspirations for success both at school and in life may become considerably

lowered (Dyrda, 2000, s. 134-135). According to the research by B. Dyrda (2007), most

students afflicted by the underachievement syndrome demonstrated disproportionate self-

esteem in relation to their intellectual capabilities.

The psycho-pedagogical literature suggests various measures to prevent this phenomenon

from expanding, such as therapeutic programs based on redefining the role of a teacher in the

classroom. A teacher-expert would then transform into an advisor, an animator, an observer, a

listener and, finally, a partner. Such a teacher automatically and quite naturally activates

processes which prevent the underachievement syndrome similarly to the model of therapy for

the underachievement syndrome based on successoriented education, as devised by S.M.

Baum, J. Renzulli, T. P. Hebert (Dyrda, 2000). The therapy, which predisposes students

towards success, engenders the self-fulfilling prophecy mechanism: while utilizing their

cognitive and creative capabilities, students explore their awareness and motivation to act and

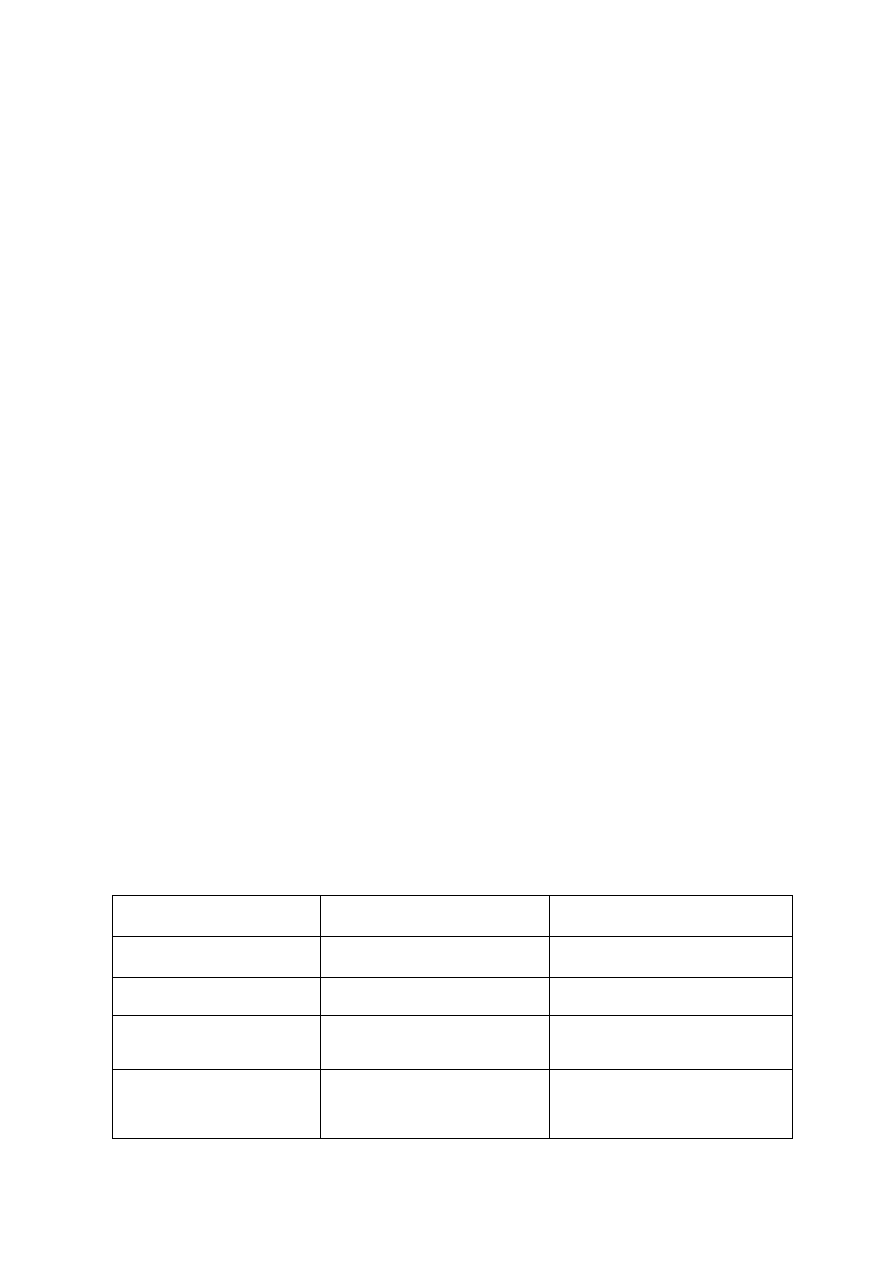

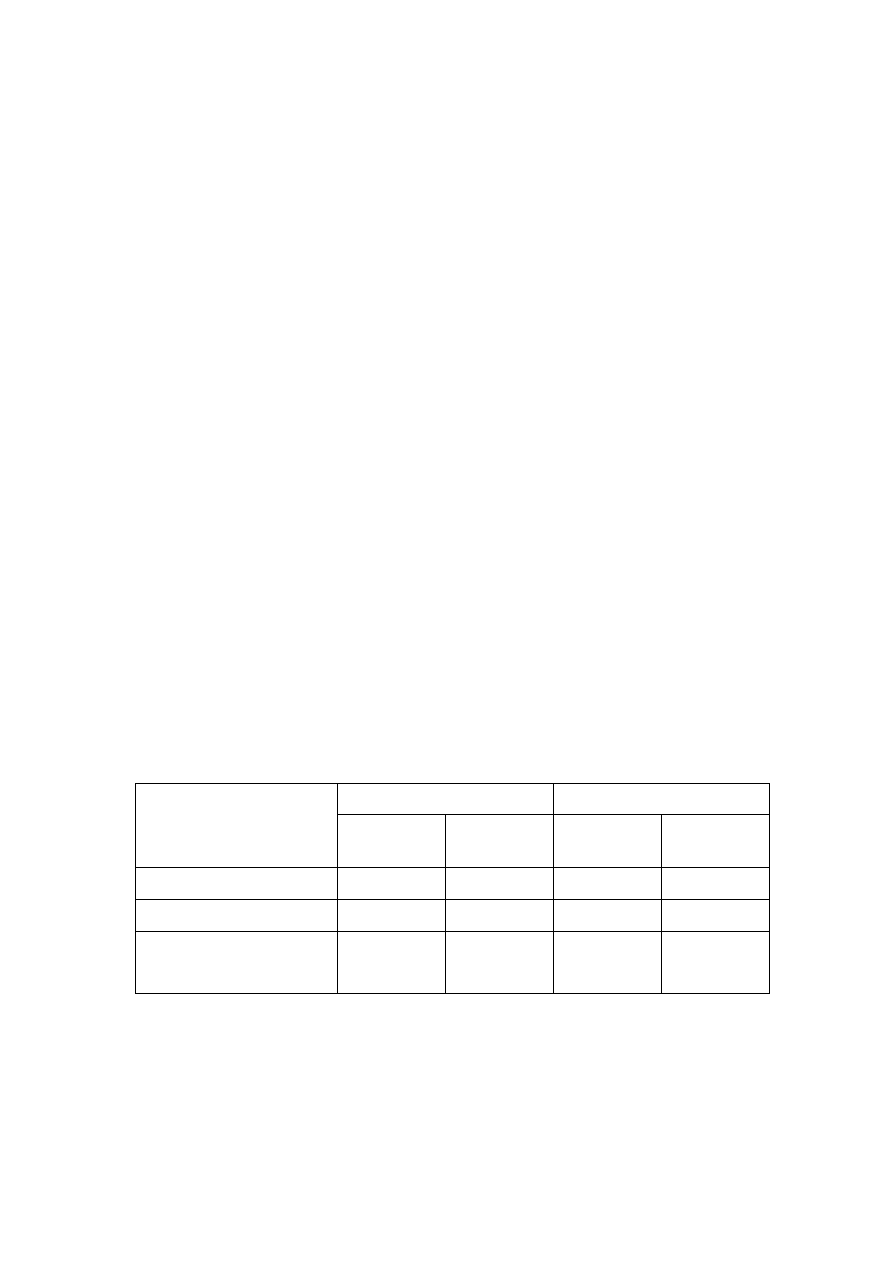

take effort to achieve given goals. The following table presents this model with the possible

results of the underachievement syndrome therapy:

Table Nr 1. Underachievement Syndrome Therapy by S.M. Baum, J. Renzulli, T.P. Hebert.

Underachievement

Syndrome

Therapy, influence,

intervention

Satisfactory school

results

Emotional problems

Teacher as a mentor

(advisor)

Understanding oneself

and one’s needs

Learning problems

Developing student’s

interests

Self-regulation

Social functioning problems

Focusing on student’s

strong points, developing

high self-confidence

Positive relations with

adults, positive influence

of peer group

Inadequate curriculum

Mutual respect, teacher

and student are

subjects in nurturing

and learning

Curriculum adjusted

to student’s capabilities

4

Inadequate teaching

methods

Activating teaching

methods, problem

based methods

Student motivated

to learn

Source: Dyrda, 2000.

However, as people are unable to succeed up to their potential in many areas of life, the

underachievement syndrome should not be limited only to the school context. The factors

which activate the underachievement syndrome can also be found among the changes which

occur in the modern society. The psycho-pedagogical literature suggests the following causes

of this problem, all of which are of social origin: unstable family model, overworked parents,

the disorganization of the family rules and principles, the liberalization of moral norms,

incoherent influence of each of the parents. Other factors which are believed to have an

adverse effect on the achievements of an individual could include the consumerist lifestyle and

models for success promoted by the media, but also the modern society competitiveness

pressure which provokes mental tension and stress. Still different causes can be found in the

family environment: the standards of behaviour, single parentage, sibling rivalry,

overprotective attitude towards a longed-for or a frail child and disproportionate expectations

(too high or too low) of child’s achievements may all contribute to the underachievement

syndrome (sf.: Rimm, 1994; Dyrda, 2000, 2007).

The characteristics of a pre-schooler’s development may play a vital role in building the

child’s behaviour model in the social environment since it is a family that sets the most

important example of behaviour and establishes norms of conduct, very often imprinted in the

personality for the whole life and influencing the individual’s educational success and failures.

The examples of internal factors which hamper the accomplishments of an individual

include: disturbance or damage of the central nervous system, emotional disorders, physical

defects and somatic disease. All the above factors hinder the functioning of an individual at

school and in the society (absences at school, numerous sick leaves, frequenting hospitals,

medical rehabilitations, sanatoriums, the meetings of occupational therapy, etc.) and thus

constitute the root of all the problems, including educational problems. The underachievement

syndrome can also be activated by low self-esteem, lack of self-acceptance or lack of others’

recognition-the effects of health and school problems, as well as failure in building social

relations, which may result from disturbed relationships with peers, parents or teachers. What

is more, the disproportion between expectations and actual achievements may be influenced by

special talents and creative abilities. A gifted child/student can display oversensitivity in some

of the following spheres (Dyrda, 2007, s. 22-23):

5

– intellectual (sensitivity is exhibited by changeability, impatience, inquisitiveness,

etc.),

– emotional (excessive sensitivity leads to impulsiveness, obstinacy, withdrawal,

etc.),

– psychomotor (oversensitivity causes heightened tension, impatience, agitation,

heightened activity, etc.),

– imaginary (high sensitivity leads to absent-mindedness, seclusion, fantasizing,

daydreaming),

– sensory (oversensitivity causes excessive facial expression and gesticulation,

twitches, inadequate reactions).

High sensitivity of a gifted and creative individual may result in behaviour differently

interpreted by parents, teachers and peers. While in certain situations such behaviour will be

approved, in others it may be regarded as antisocial, egotistic or aggressive. The possible

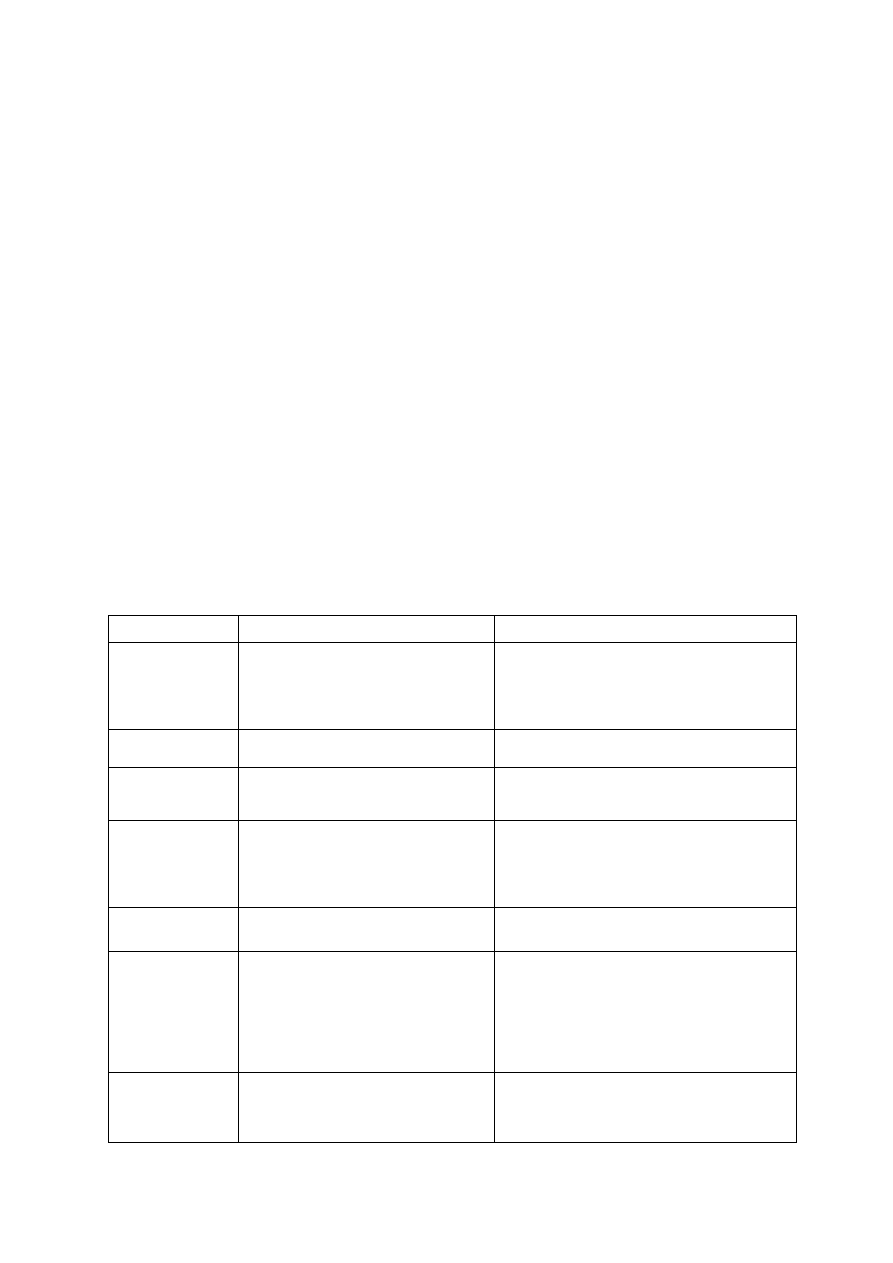

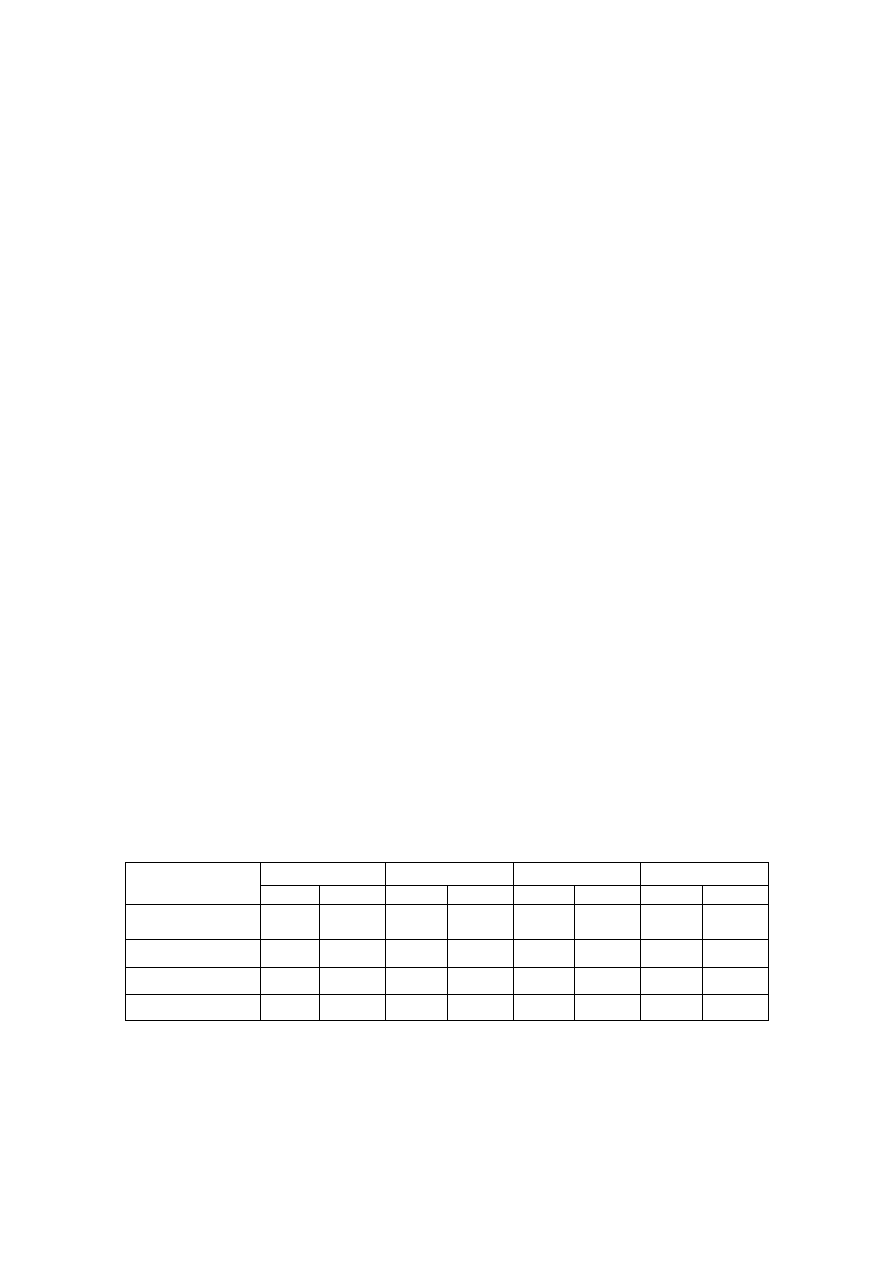

differences of the social reception of such behaviour are contrasted in the table Nr 2:

Table Nr 2. Behaviour of a gifted individual

Feature

Positive reception

Negative reception

activity

motivation-driven,

energetic, has wide

interests

overactive, stubborn and

intransigent, may be

disorganized, focuses excessively

on one field of interest,

has concentration difficulties

creativity

predisposed towards

problem solving

does not like routine activities

communicative

competence

has rich vocabulary,

can debate, argue and

persuade with ease

tends to manipulate people

around, is quarrelsome, intransigent,

invents endless excuses

independence

independent, prefers

to work individually

nonconformist, is quarrelsome,

may be noisy and pretentious,

lacks discipline and opposes

instructions of parents or teachers,

has teamwork problems

sensitivity

sensitive and empathic

oversensitive to criticism and

judgment, egocentric

cognitive skills

fast learner, learns new

things willingly and

with ease, enjoys

challenges connected

to interests, vast but

often “non-school”

knowledge

impatient, gets bored fast, does

not complete assignments

which are too easy or not

connected to interests, puts

minimal effort into schoolwork,

focused on individual interests

and problems

responsibility

high expectations

of self and others

perfectionist, intolerant, does

not finish work which

is imperfect, often gives up

after first failure

6

morality

high level of moral

judgment

does not acknowledge authority

and nurturing rules

cognitive

curiosity

interested in the world

around, has many

interests

asks many questions at the

same time, diversified interests

prevent focus on specialization

sense

of humour

good sense of humour

may exaggerate in making fun

of others, may be cynical

imagination

developed visual or

spatial thinking, tends to fantasize and

daydream

makes things up, lives

in a world of his/her own,

secludes him/herself

Source: compilation by the author based on the sources: Rimm, 1994; Dyrda 1997, 2000.

Many psycho-pedagogical sources draw attention to the fact that school education which

does not develop students’ creativity, only lowers their cognitive curiosity and blunts their

interests. Such school does not encourage question-based thinking (Szmidt, 2006). Moreover, it

provides strong negative reinforcement based on negative messages, such as “wrong!,” “don’t

fantasize!,” “don’t be clever!” Additionally, it hinders imagination, as well as intuitive and

divergent thinking. As a result, student’s independence, openness, creativity and self-

confidence are hampered (sf.: Dobrołowicz, 1995), which may ultimately lead to a negative

attitude towards school in general.

In Poland there are no universally operating schools which develop students’ special

abilities, as there is no system of supporting gifted students in the pursue of their individual

goals and unique (artistic and social) interests. On the contrary, the school system demands

high results in typical school subjects without considering students unique needs regarding

their interests and education, as well as their diverse ways of learning. One cannot say that

such a school exists for the student, for it is the student who is to adapt to the school model of

functioning and education.

Still educators and professionals involved in the development and education of children

at a pre-school age are seeking ideas and methods which will help them to prepare the child for

the next stages of education in an optimum way. Creating proper conditions for identifying and

stimulating imagination as well as creative thinking and skills of the child when performing

various development tasks may therefore be essential for the preparation of the individual for

an active and creative life (sf.: Szmidt, 2007).

2. A dynamic pictures technique as a stimulus for imagination and thinking

development

7

A specific and indispensible means in the educational process of a pre-schooler are

various illustrations and pictures wildly used by teachers as substitute examples of the

surrounding reality.

Pictures activate the situation, they evoke curiosity ant the ability to carry out tasks on

one’s own. To understand an illustration, you should see many things which are not visible in

it. The illustration is a fragment of life (or a fantasy novel), stationary at some point in its

lifetime - you have to imagine the movements and actions of a person being motionless in the

picture, guess what proceeded the depicted moment in order to draw right conclusions on the

topic, content, and “thoughts” of the presented image. Its understanding is therefore the result

of perception as well as completion of the content by imagination, abstract thinking and

reasoning.

As perceived S. Szuman (1951) children do not limit their perception of a picture to bare

naming the depicted object and creatures. They imagine different events and situations

connected with the picture in which both the objects or creatures act, reason and investigate

against the background. The mind of a small child does not only copy the picture’s individual

elements, but explores the image - notices different things, classifies and combines them which

finally makes the child create his/her own ideas and conclusions (Szuman, 1936/1937). Thus

work with the picture should be directed to “explain” the image (and not just enumerate the

objects or describe and name the activities of the people), which means spotting the details,

making comparisons, detecting possible relations and the main and most important subject of

the picture.

Images teach concentration, memorizing and reasoning which support the intellectual

development of a child. They provide the material for creative work and stimulate the

motivation to use the material to do something original. Tests, trainings and techniques applied

in psychometrics which incorporate the elements of perception, reproduction and

transformation of images, show the importance of imagination and visual thinking used for

determining the individual’s current level of the development of their abilities (sf.: Matczak,

1994; Karwowski, 2006; Szmidt, 2008). The above mentioned abilities and skills are being

developed primarily by dynamic pictures. These are the images of situations in which the

content may change under the influence of imagination (Młodkowski, 1998).

a. The dynamic pictures technique

8

The technique of dynamic pictures developed by me is a set of images, some of them

depicting scenes or events whose content may change under the influence of imagination. Due

to the partial indeterminacy, ambiguity and allusion in the content of these images, they require

not only description, but also the explanation of the cause-effect relationships, some

interpretation and completion. With the above mentioned advantages these pictures can be a

stimulus for a child to create his/her own stories on the basis of imagined or anticipated events,

which initiate or determine the illustrated situation. What is more, they may also inspire the

child to invent their own titles, characters, stories, adventures, unusual architectural features,

vehicles, objects and events (Płóciennik i Dobrakowska, 2009).

When implementing this technique, I noticed that creating an image-inspired stories by

children can provide a teacher with some information about the child’s vocabulary, speech

making abilities, attention span, memory, and above all - about the child’s understanding of the

visual content, the degree of his/her imagination being stimulated, cause and effect thinking

and the involvement in the content perceived in the picture.

The dynamic pictures technique which I developed has become an essential element of

the pedagogical experiment. The main objective of this pedagogical research was to investigate

and describe the effect of the dynamic pictures technique on the development of creative

abilities in a child in their late pre-school age. Therefore I formulated the following research

problem: “What is the impact of the dynamic pictures technique on the development of

selected creative abilities of 5 and 6 year old children?” This problem has been divided into

more specific issues: “What impact does the dynamic pictures technique have on the

development of the abilities of generalization of verbal and visual content (logical thinking),

inference (logical thinking), to give reasons (critical thinking), imaginative capacities

(imagination), commitment and perseverance in the task (motivation), the readiness to take

cognitive risk (motivation), flexibility, originality, and elaboration (divergent thinking).

The research, whose main aim was to verify the effectiveness of the dynamic picture

technique in developing creative abilities of a pre-schooler, confirmed that creativity should be

developed and diagnosed among all school children because revealing and activating potential

abilities is only possible when they are being stimulated in accordance with the dynamics of

their development in different fields and different areas of the undertaken activity. In addition,

the studies also confirmed the dependence of divergent thinking on other skills and motivation

- their development is through the use of different and varied methods of problem and heuristic

learning that foster integration and development of all cognitive processes and mechanisms on

9

the foundation of motivation to act (Płóciennik, 2010). The studies confirm the findings of

other studies that were conducted in the past on:

– the effectiveness of training works to increase the flow of ideational (number of

ideas),

– the effectiveness of wider integration of creative abilities and environmental

conditions for improving product quality,

– the effectiveness of the environmental conditions to stimulate thinking in relation to

pre-school children,

– improving the results of “image-visual” thinking through the integration of imagery

and verbal systems during tests,

– the effectiveness of creativity training in relation to creative competences acquired by

pre-school children in the course of learning,

– selection of learning conditions for a child to match goals or objectives set or planned

by a teacher of elementary education and ways to monitor children’s work and

activate them (Płóciennik, 2010, s. 185-186).

After applying the dynamic pictures technique higher ideational fluency and originality

of children’s ideas in comparison with the group has been noticed in posttest studies. It was

visible both when the children invented titles, formed associations to the content of the

pictures, came up with epithets, analogies and comparisons of selected objects as well as when

they developed interesting ideas to complete the content of the pictures with probable and

improbable events.

b. Supporting the child’s development – the analysis of individual cases

Further analysis of my previous research have revealed the possibility of applying the

dynamic picture technique both in therapy and supporting the child’s development. Below I

present the description of individual cases which show examples of reducing the level of

difficulties in performing certain tasks and activities.

A child with an identification number E-1/KW/19

He is a six-year old boy, an only child brought up in a two-parent family, attending the

kindergarten for two years. Both parents have secondary education (mother is a nurse, father- a

10

knitter). They have pointed out in the survey that they do not devote enough time to their child

and the child’s main occupation at home is watching cartoons and playing with blocks. They

have also admitted that their son is very keen on playing and talking with adults as well as

being read books by them.

As for his developmental achievements, the parents have noticed his spontaneous

curiosity, eagerness to play and reluctance to stop. However, as for his developmental

problems, the parents have mentioned difficulties in clear articulation of sounds, shyness, lack

of interest in doing jigsaws and a tendency to get easily tired while performing tasks which

need more concentration. The survey also shows that the child must have suffered from some

health disorders as the mother consulted various specialists such as a pulmonologist, an

allergist and a gastroenterologist.

Teachers in the kindergarten have noticed that the boy most often chooses only

construction games. Among his developmental achievements they point out his friendliness

towards peers and a lot of skills in a perceptive-cognitive sphere: intense concentration on a

task, the ability to analyze and synthesize, to notice the differences and similarities and to build

cause-result relations as well as good memory and fast remembering things. However, the

teachers have also observed the boy’s manual and communication problems, the dislike of

artistic and expressive activities, shyness, lack of self-confidence, unwillingness to participate

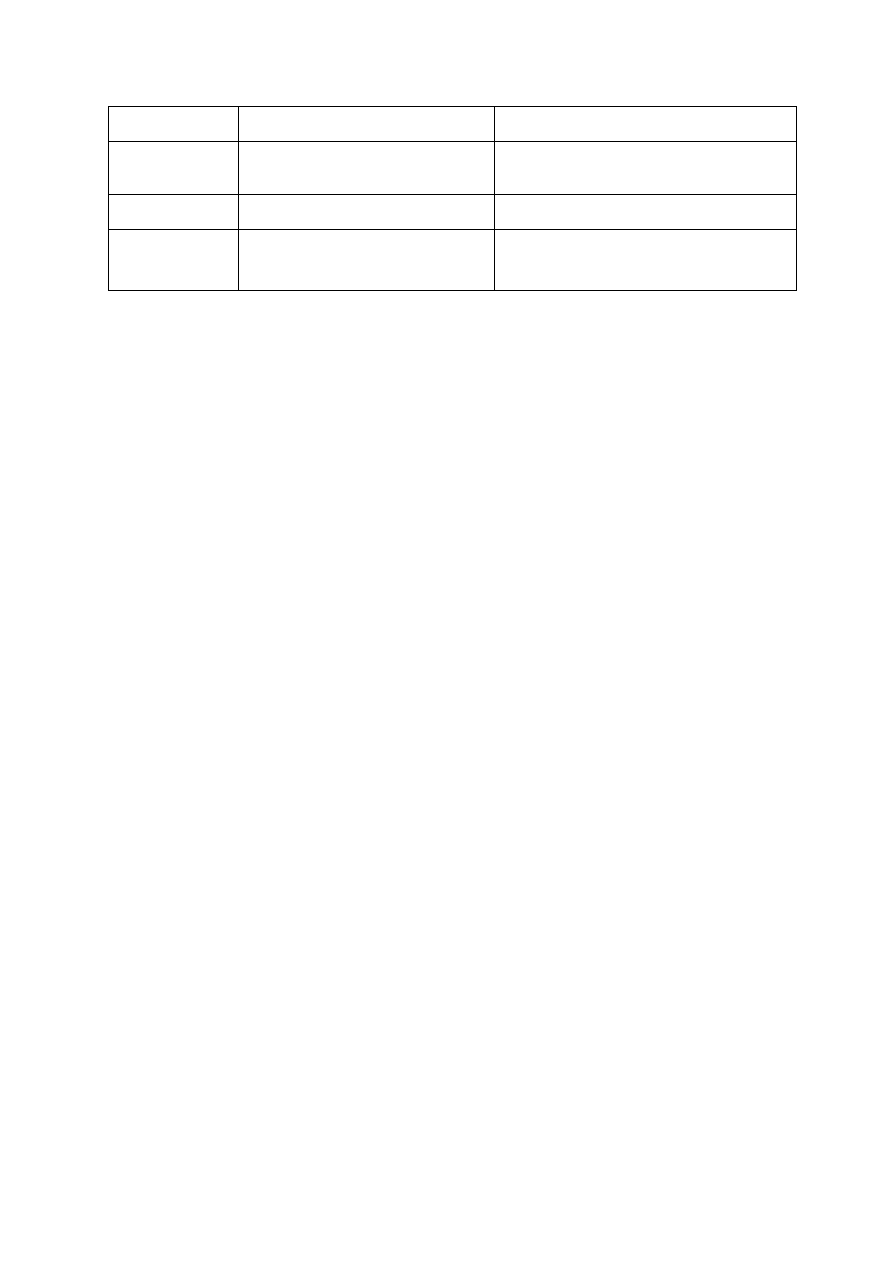

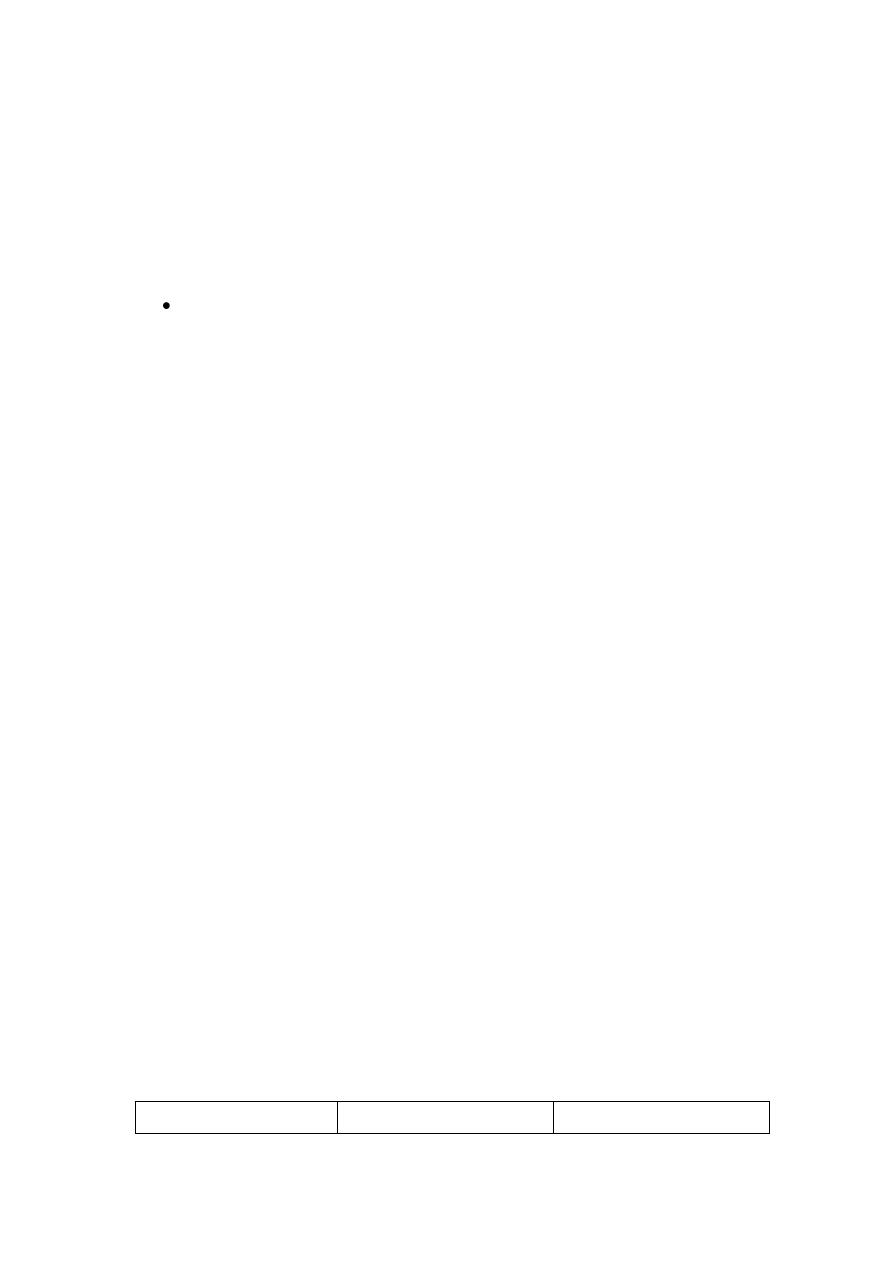

in new and more difficult tasks. You may find the comparison of raw results achieved by the

child in a table below.

Table nr 3. The comparison of pre-test and post-test raw results of a child from an experimental group with the

highest increase of an artistic skill indicator.

The source: own study based on the results of own research (Płóciennik, 2010).

In the pre-test phase the child chose a task from a box “easy tasks”, however, in the post-

test he picked “more difficult tasks”. When thinking up a title for a picture, in both the pre-test

and post-test the child came up with one title, however, as for the titles for stories, in the pre-

test he put forward one idea whereas in the post-test - several ideas. When creating a picture

group of the variables

Pre-test

Post-test

raw results of

a child

avarage results

of a group

raw results of

a child

avarage results

of a group

general abilities

10

9,74

19

14,3

task commitment

10

12,5

17

13,1

creative skills

23

(including 6

original ideas)

22

(with average

7.5)

63

(including 22

original ideas)

32,5

(with average

14.0)

11

story, in the pre-test he mixed up the pictures while in the post-test he put them correctly. Both

in the pre-test and post-test the boy was able to explain logically the order of the pictures and

create the content of the story. When completing a picture, in the pre-test he added 6 extra

elements to the original and in the post-test – 7. Both in the pre-test and post-test the boy

painted science-fiction reality (in the pre-test: “little rainbow people”, “little monsters”,

“volcanoes”, in the post-test: “a dessert man”, “a snake called Water”, “a town which is

opening out”, “a volcano on a snow island”). Despite some manual difficulties, the boy was

able to express his thoughts in the picture. There was a small

disproportion

in the scope of

ideas used for describing the picture (in the pre-test – 3 epithets, in the post-test – 2).

Nevertheless, there was a discrepancy in a task involving making up rhymes for a given word

(in the pre-test – no ideas, in the post-test – 9 rhymes including 6 neologisms: koty > “oty,

moty, toty, soty, zoty, egzoty”). As for finding similar patterns in the pictures, in the pre-test the

boy put 13 pairs together and three pictures in a row for two times according to the “colour”

category. However, in the post-test he put together one row of two elements and four three-

element rows according to the “geometric figures” class. When making transformations and

specifying geometric figures in the pre-test the boy drew two objects on the basis of a circle

belonging to two categories, but in the post-test he created ten objects based on a rhomb

belonging to eight different categories. During the assessment phase of the task in the pre-test

the boy admitted that he had liked the task because “he was happy” while in the post-test he

explained that “he liked all the tasks because they were nice”. The

disproportion

between

painted pictures and created titles

was

also noticed by a competent jury and their grades are

presented in a table below.

Table nr 4. Comparing the grades given by a competent jury to the child from an experimental group with the

highest growth of an creative skill indicator.

The source: own study based on the results of own research (Płóciennik, 2010).

As the table shows the jurors assessed the output in post-test lower (the average 0,82)

than in the pre-test (the average 1,11). The analysis of the child’s achievements may indicate

the output

1 juror

2 juror

3 juror

4 juror

Pre-test Post-test Pre-test Post-test Pre-test Post-test Pre-test Post-test

the title of the

picture

0

0,25

1

1

0,25

0,25

0,25

0,5

the title of the story

1,5

0,8

1,75

1,35

1,25

1,05

1,25

1,35

transformations

0,5

0

1

1

0,5

0

0,5

0

elaboration

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

0

12

that the big

disproportion

between the raw results of the pre-test and the post-test does not

comply with the assessment provided by the competent jury. In the case of this child there was

an improvement of abilities in the scope of the variables groups (with the ideational fluency

being the leading one), and first of all in presenting original ideas compared to other children in

the same group (as far as 22 ideas created by the boy in the set of post-test tasks were not

repeated in E1 group).

A child with identification number E-1/PZ/23

He is a six-year boy, an only child from a single-parent family, attending a kindergarten

for the second year. His mother is a shop assistant with secondary education. In a survey she

admits spending four hours a day with her son.

At home the child is mostly keen on playing with toy cars, stuffed toys, mechanical and

construction toys, he also draws and paints, watches cartoons, does jigsaws and plays with

blocks. The child also likes the company of adults. The mother also points out that her son is

skillful at painting, constructing and dancing. In addition he has a sense of humor, asks a lot of

questions, tries to solve problems by himself, is eager to play and reluctant to stop. As for his

developmental problems she mentiones difficulties in counting, correct articulating of sounds

and focusing on one activity only, as well as aversion for mental effort and playing outdoor.

He also withdraws from new and difficult tasks. She also stresses the child’s misbehaviour and

not obeying the instructions. The mother consulted specialists (a psychologist and speech

therapist) who gave the diagnosis of hyperactivity as a result of premature birth (the boy was

born in the 25

th

week of pregnancy).

Teachers at the kindergarten have observed that the child is eager to take up different

artistic and constructive-manual activities. They have noticed only two developmental

achievements (his being friendly towards peers and perceptive skills). In addition, they have

also mentioned numerous developmental problems: verbal, communicative, difficulty in

verbalizing thoughts and following instructions, being often distracted and unwilling to do

mental or expressive activities and cooperate with the group. What is more, the boy has been

described as shy, lacking in self-confidence, able to withdraw easily and having difficulties in

presenting both his outputs and himself to others. You may find the comparison of raw results

achieved by the child in a table below.

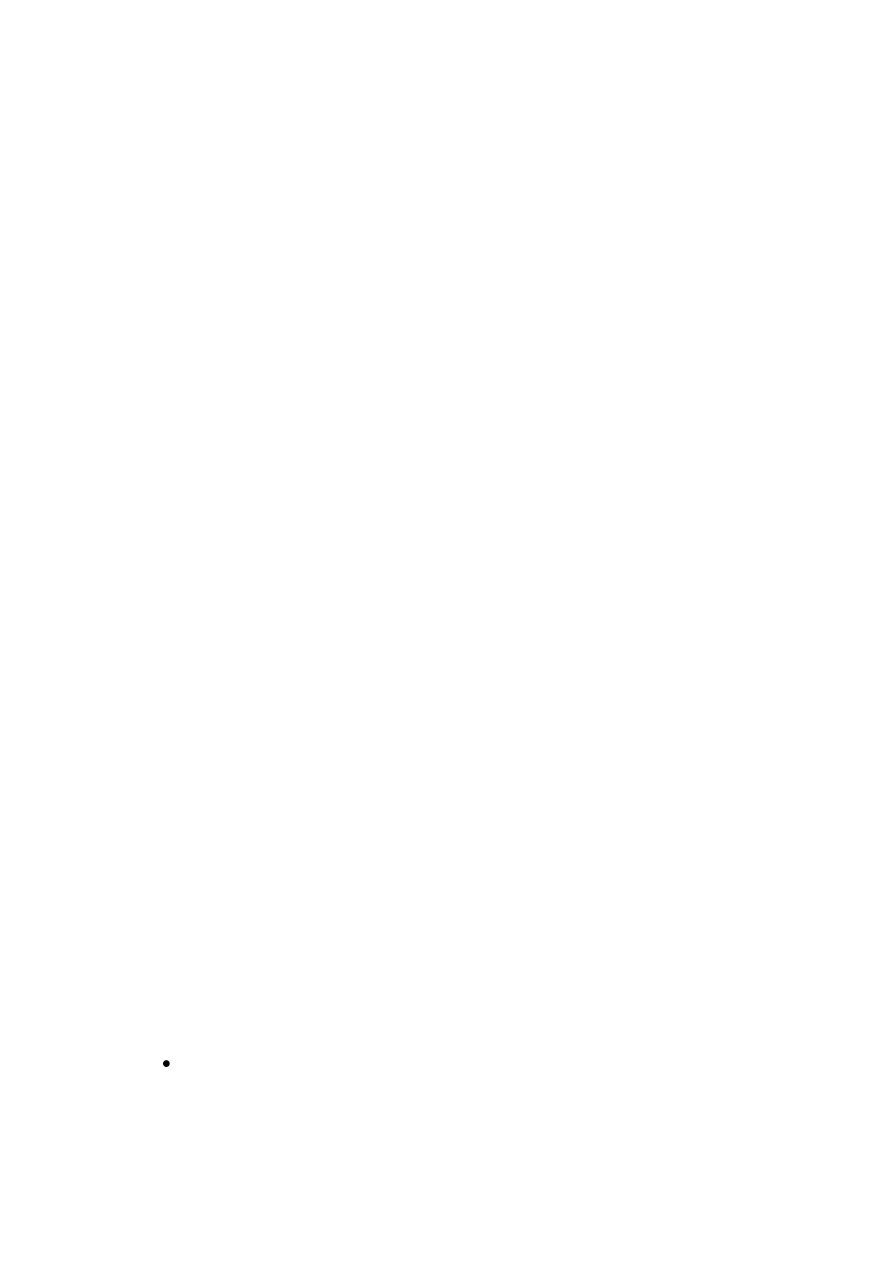

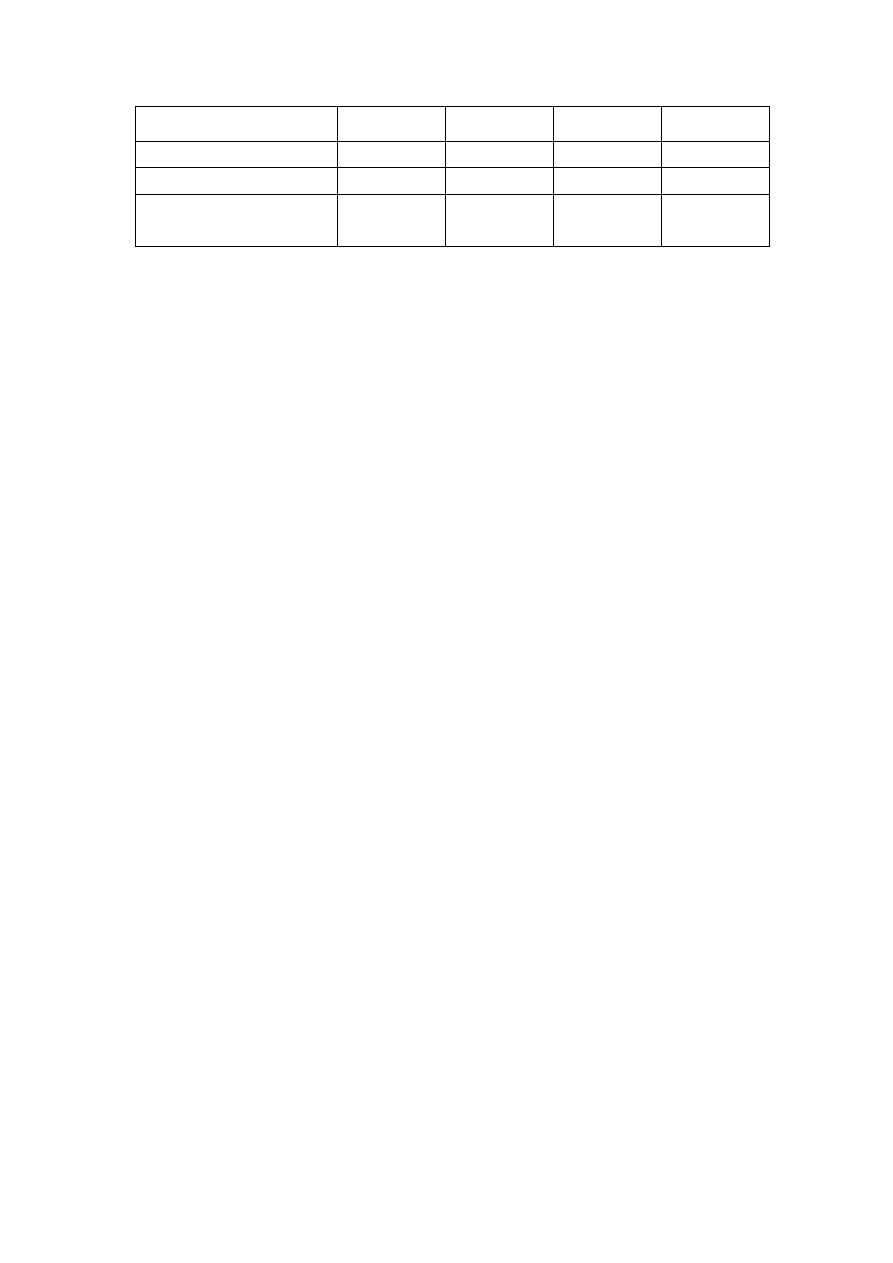

Table nr 7. Comparison of raw results achieved by the child ( from an experimental group) with a significant

increase in a quality and quality of the his outputs.

Pre-test

Post-test

13

The source: own study based on the results of own research (Płóciennik, 2010)

In the pre-test phase the child chose the tasks from a box “most difficult tasks” with a

view to completing them. However, in the post-test he picked a set of tasks from a box “more

difficult tasks”. When thinking up the titles for a picture, the boy came up with one title both in

the pre-test and post-test (in the pre-test: in a descriptive form, in the post test: in a concise

form). As for creating the titles for a story, he gave one title in the pre-test and two in the post-

test, both in a concise form. While building a picture story, in the pre-test the boy put all the

pictures together with one mistake (putting the third picture as the last one), but he was able to

combine only two pictures logically. However, in the post-test he did not put the pictures

correctly and did not want to say what was happening in them. When completing the pictures,

in the pre-test he added only four elements in a very simple and schematic way not using the

whole space on the paper. In the post-test, despite the fact that the tests were held in April, the

boy used the basic elements to build a Christmas tree with presents adding only 5 extra

elements. As for giving epithets for the provided object, both in the pre-test and post-test he

came up with only one correct term, however, in a “rhyming task” he was not able to think of

any rhymes. As for finding similar patterns in the pictures, in the pre-test he managed to put

one pair together and one set of five pictures. When looking at the pictures he paid attention to

more distant similarities (“the stripes”). Nevertheless, in the post-test he put together four two-

element rows and one four-element row belonging to two different categories.

When transforming and specifying geometrical figures in the pre-test the boy drew four

objects on the basis of a circle belonging do class one (“the vehicles”), all four vehicles being

drawn on the basis of two or more circles. The boy did not colour his pictures. However, in the

post-test he created 15 objects based on a rhomb belonging to eleven different groups of

objects. All the pictures contained many details, were accurately finished and beautifully

coloured. In the pre-test the boy justified his highest note for the tasks suggested by a tester

saying “because it was nice to draw something”. In the post-test he also rated the suggested

tasks highly and admitted “because I had many ideas and felt like drawing”. In the pre-test the

group of the variables

raw results of

a child

avarage results

of a group

raw results of

a child

general abilities

9

9,74

10

14,3

task commitment

15

12,5

16

13,1

creative skills

18

(including 4

original ideas)

22

(with average

7.5)

47

(including 12

original ideas)

32,5

(with average

14.0)

14

boy went back to the transformations (task 8) but he did not add any elements. However, in the

post-test he used additional time when completing the picture.

The

disproportion

between the quality of the painted pictures and created titles

was

also

noticed by a competent jury. A table below presents the comparison of the jurors’ grades given

for the boy’s output in the pre-test and post-test phase.

Table nr 8. Comparison of the grades given for the output of the child (from an experimental group) with a

significant increase in quantity and quality of the output.

The Source: own study based on overall results of own research (Płóciennik, 2010)

Although his manual skills have improved significantly, they were not specified as the

indicator of “general abilities” but as a variable of elaboration in “creative skills”.

Nevertheless, the most outstanding abilities may be noticed in making transformations and

working out the base object, in this case geometric figures. This task was highly scored in the

post-test and received average grades in the pre-test. The competent jurors gave it good grades

both in the pre-test and post-test. I have also observed that the boy had more difficulties in

expressing his thoughts graphically rather than verbally.

* * *

My research confirmed the role of the individual experience, education and culture in

cognitive development. It also proved the thesis that the development and identification of

potential creativity is relatively easy if you use heuristic techniques, ask questions, stimulate

curiosity, and make associations. The child’s mind was stimulated by transformation of ideas

and images, handling issues from different perspectives, playing with ideas, information, and

inventing new and unusual things. As a result it improved and developed during the course of

experimental activities, especially in the capacity to perceive relationships, understand the

hidden meanings, reason with the use of inductive, deductive and divergent thinking.

the output

1 juror

2 juror

3 juror

4 juror

Pre-test Post-test Pre-test Post-test Pre-test Post-test Pre-test

Post-

test

the title of the

picture

0,25

0,5

1

1,5

0,25

1

0,25

1,25

the title of the story

0,5

0,63

1,25

1,5

0,75

1,13

0,5

1,75

transformations

2

2

2

2

1

2

2

2

elaboration

0

0

0,75

1,25

0,25

1

0

0,75

15

Bibliography:

1. Dobrołowicz W., Psychodydaktyka kreatywności, WSiP, Warszawa 1995.

2. Dyrda B., Zjawiska niepowodzeń szkolnych uczniów zdolnych. Rozpoznawanie i

przeciwdziałanie, Oficyna Wydawnicza „Impuls”, Kraków 2007.

3. Dyrda B., Syndrom nieadekwatnych osiągnięć jako niepowodzenie szkolne uczniów

zdolnych. Diagnoza i terapia, Oficyna Wydawnicza „Impuls”, Kraków 2000.

4. Ekiert-Grabowska D., Syndrom Nieadekwatnych Osiągnięć Szkolnych, „Życie Szkoły”,

1994, Nr 3.

5. Karpińska A., Niepowodzenia szkolne jako kategoria edukacyjnego dialogu [in:] A.

Karpińska (eds.), Edukacja w dialogu i reformie, Wyd. Trans Humana, Białystok 2002.

6. Karwowski M. (eds.), Identyfikacja potencjału twórczego. Teoria – metodologia -

diagnostyka, Wyd. Psychopedagogiczne Transgresje, Warszawa 2006.

7. Matczak A., Diagnoza intelektu, Wydawnictwo Instytutu Psychologii PAN, Warszawa

1994.

8. Młodkowski J., Aktywność wizualna człowieka, PWN, Warszawa 1998.

9. Niemierko B., Między oceną szkolną a dydaktyką. Bliżej dydaktyki, WSiP, Warszawa 2000.

10. Płóciennik E., Dobrakowska A., Zabawy z wyobraźnią. Scenariusze i obrazki o charakterze

dynamicznym rozwijające wyobraźnię i myślenie twórcze dzieci w wieku przedszkolnym i

wczesnoszkolnym, Wydawnictwo AHE, Łódź 2009.

11. Płóciennik E., Stymulowanie zdolności twórczych dziecka. Weryfikacja techniki obrazków

dynamicznych, Wydawnictwo UŁ, Łódź 2010.

12. Rimm S., Bariery szkolnej kariery. Dlaczego dzieci zdolne mają słabe stopnie?, WSiP,

Warszawa 1994.

13. Szmidt K.J., Teoretyczne i metodyczne podstawy rozwijania zdolności myślenia pytajnego

[in:] W. Limont i J. Cieślikowska (eds.) Dylematy edukacji artystycznej, tom II, Oficyna

Wydawnicza „Impuls”, Kraków 2006.

14. Szmidt K.J., Pedagogika twórczości, GWP, Gdańsk 2007.

15. Szmidt K.J., Trening kreatywności. Podręcznik dla pedagogów, psychologów i trenerów

grupowych, Wydawnictwo Helion, Gliwice 2008.

16. Szuman S., Jak dzieci oglądają obrazki i co one im dają, „Przedszkole” 1936/1937, nr 4/5.

17. Szuman S., Ilustracja w książkach dla dzieci i młodzieży, Wiedza- Zawód-Kultura. Tadeusz

Zapiór, Kraków 1951.

18. Wiechnik R., Intelektualne uwarunkowania powodzenia w nauce młodzieży szkolnej w

wieku 12-18 lat w świetle badań empirycznych [in:] S. Popek (eds.) Z badań nad

zdolnościami i uzdolnieniami specjalnymi młodzieży, Wydawnictwo UMSC, Lublin 1987.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Płóciennik, Elżbieta Teaching for wisdom in modern early education (2013)

Gorban A N singularities of transition processes in dynamical systems qualitative theory of critica

Taylor & Francis The Problems of the Poor in Tudor and Early Stuart England (1983)

IMPORTANCE OF EARLY ENERGY IN ROOM ACOUSTICS

Antonović Malachite finds in Vinca culture evidence of early copper metalurgy in Serbia

The Contribution of Early Traumatic Events to Schizophrenia in Some Patients

Chirurgia wyk. 8, In Search of Sunrise 1 - 9, In Search of Sunrise 10 Australia, Od Aśki, [rat 2 pos

Nadczynno i niezynno kory nadnerczy, In Search of Sunrise 1 - 9, In Search of Sunrise 10 Austral

Harmonogram ćw. i wyk, In Search of Sunrise 1 - 9, In Search of Sunrise 10 Australia, Od Aśki, [rat

Effect of?renaline on survival in out of hospital?rdiac arrest

cambridge certificate in advanced english 4 tests 7V63YSU4THUF5Y2CZPN62J7CSAAOCBX6QILXRDI

Certificate in Advanced English III

chirurgia wyk 7, In Search of Sunrise 1 - 9, In Search of Sunrise 10 Australia, Od Aśki, [rat 2 pose

fitopatologia, Microarrays are one of the new emerging methods in plant virology currently being dev

Poland to Take Part in Administration of Iraq

In pursuit of happiness research Is it reliable What does it imply for policy

Chirurgia wyk. 5, In Search of Sunrise 1 - 9, In Search of Sunrise 10 Australia, Od Aśki, [rat 2 pos

więcej podobnych podstron