American Sociological Review

http://asr.sagepub.com/content/75/1/101

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0003122409357047

2010 75: 101

American Sociological Review

Suzanne C. Eichenlaub, Stewart E. Tolnay and J. Trent Alexander

Moving Out but Not Up : Economic Outcomes in the Great Migration

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

American Sociological Association

can be found at:

American Sociological Review

Additional services and information for

http://asr.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

http://asr.sagepub.com/subscriptions

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Moving Out but Not Up:

Economic Outcomes in the

Great Migration

Suzanne C. Eichenlaub,

a

Stewart E. Tolnay,

a

and

J. Trent Alexander

b

Abstract

The migration of millions of southerners out of the South between 1910 and 1970 is largely

attributed to economic and social push factors in the South, combined with pull factors in

other regions of the country. Researchers generally find that participants in this migration

were positively selected from their region of origin, in terms of educational attainment and

urban status, and that they fared relatively well in their destinations. To fully measure the

migrants’ success, however, a comparison with those who remained in the South is neces-

sary. This article uses data from the U.S. Census to compare migrants who left the South

with their southern contemporaries who stayed behind, both those who moved within the

South and the sedentary population. The findings indicate that migrants who left the

South did not benefit appreciably in terms of employment status, income, or occupational

status. In fact, inter-regional migrants often fared worse than did southerners who moved

within the South or those who remained sedentary. These results contradict conventional

wisdom regarding the benefits of exiting the South and suggest the need for a revisionist

interpretation of the experiences of those who left.

Keywords

Great Migration, migration outcomes

The Great Migration

1

was one of the most

significant demographic events in U.S. his-

tory. Between 1910 and 1970, millions of

southerners left the South in search of better

circumstances and opportunities. At the turn

of the twentieth century, poor economic con-

ditions in the South for both blacks and

whites, along with oppressive social condi-

tions for blacks, served as a substantial

incentive for many to flee the South. At the

same time, other regions of the country, espe-

cially the Northeast and the Midwest, were

experiencing economic growth that consider-

ably expanded the employment opportunities

in those regions. Until World War I, immi-

grant labor from Europe filled many low-

wage, low- and unskilled jobs in the booming

industrial economy of the North.

2

When the

flow of European immigrants was sharply

curtailed, initially as a result of the war in

a

University of Washington

b

University of Minnesota

Corresponding Author:

Suzanne C. Eichenlaub, Department of Sociology,

Box 353340, University of Washington, Seattle,

WA 98195, USA

E-mail: eich@u.washington.edu

American Sociological Review

75(1) 101–125

Ó American Sociological

Association 2010

DOI: 10.1177/0003122409357047

http://asr.sagepub.com

Europe and later because of restrictive U.S.

immigration policies, northern employers’

search for inexpensive workers turned to

the southern United States (Collins 1997).

This created a strong economic incentive

for frustrated and ambitious southerners to

head north. The Great Migration that ensued

saw a massive exodus that effectively redis-

tributed a large proportion of the southern-

born population across the country.

Consistent with its significance as a defining

American demographic phenomenon, the

Great Migration has received a good deal of

attention from social scientists. One group of

scholars describes and interprets the many

ways in which the Great Migration, especially

the resulting growth of black communities in

large metropolitan areas, transformed northern

and western institutions, culture, and led to

increasing residential segregation in virtually

every major urban area (e.g., Boustan forth-

coming; Cutler, Glaeser, and Vigdor 1999;

Gregory

1989,

2005;

Lemann

1991;

Lieberson 1980; Massey and Denton 1993;

Philpott 1978; Wilson 1978, 1987). Others

focus primarily on the migrants’ socioeco-

nomic characteristics and how they fared eco-

nomically after leaving the South (e.g.,

Gregory 1995; Lieberson 1978b; Lieberson

and Wilkinson 1976; Long 1974; Long and

Heltman 1975; Tolnay 1997, 1998b; Tolnay

and Crowder 1999; Tolnay, Crowder, and

Alderman 2000, 2002; Tolnay and Eichenlaub

2006; Wilson 2001). The evidence suggests

that migrants who left the South tended to be

positively selected compared with those who

remained behind (Alexander 1998; Lieberson

1978a, 1980; Marks 1989; Tolnay 1998a;

Vigdor 2002). Furthermore, research docu-

ments a generally successful experience for

southern migrants in the non-South relative to

their northern-born neighbors, at least for

blacks. Despite the important contributions by

these previous efforts to understand the

macro-level

consequences

of

the

Great

Migration and the outcomes for participants

in this watershed sociodemographic event, no

study systematically explores whether leaving

the South was associated with improved cir-

cumstances for the migrants. In this article,

we examine whether southerners who left the

South benefited economically as a result of

migration by comparing them with their coun-

terparts who remained in Dixie.

BACKGROUND AND THEORY

The Great Migration

There were ample reasons to flee the South

during the early decades of the twentieth

century. The agricultural system that domi-

nated the southern economy had long pro-

duced

little

profit

and

considerable

hardship for many whites and blacks. At

the same time, retarded industrial develop-

ment in the region restricted the nonagricul-

tural employment possibilities available to

southern

workers

(Daniel

1972;

Kirby

1987; Mandle 1978; Newby 1989; Raper

1936; Raper and Reid 1941; Woofter and

Winston 1939). In addition to poor eco-

nomic prospects, blacks were also motivated

to escape the South’s oppressive social con-

ditions. The Jim Crow South provided

blacks with limited educational and occupa-

tional opportunities and virtually no politi-

cal voice (Anderson 1988; Kousser 1974;

Margo 1990; Woodward 1966). Racially

segregated and substantially inferior facili-

ties and institutions were constant reminders

of blacks’ subordinate status in southern

society. Racial violence also played a role

in encouraging out-migration from the

South in the early years of the Great

Migration (Tolnay and Beck 1992). By con-

trast, economic opportunities in the indus-

trial Northeast and Midwest held great

attraction for struggling southerners. With

the beginning of World War I, which saw

a demand for accelerated war-related indus-

trial production and a cessation of massive

European immigration, northern employers

began seeking inexpensive labor, both black

and white, from southern states (Collins

102

American Sociological Review 75(1)

1997). In addition, southern blacks’ percep-

tions of a more benign racial climate in the

North served as a powerful attraction.

In the early years of the Great Migration,

the primary migration streams out of the

South were directed to the Northeast and the

Midwest, following established transportation

routes and exploiting networks created by the

earlier migration of friends and family mem-

bers. Although a considerable proportion of

whites headed to the West from the beginning,

it was not until mid-century that blacks began

selecting western destinations, when the

booming West Coast defense industry at-

tracted black and white workers from all

over the country (Tolnay et al. 2005). In addi-

tion to migrating between regions, many

southerners moved within the South in search

of better opportunities. Especially during the

early decades of the Great Migration, there

were limited opportunities for nonagricultural

employment (e.g., mills and mines), but such

industrial opportunities did grow over time.

In addition, many mobile southerners moved

from rural areas to small southern towns and

cities in search of economic and social oppor-

tunities. Of course, many opted not to move at

all (Falk 2004).

The early and persistent images of partic-

ipants in the Great Migration were over-

whelmingly negative (Berry 2000; Drake

and Cayton 1962; Frazier 1932; Gregory

1989). This was especially true for black

migrants who were commonly portrayed as

illiterate, displaced sharecroppers, but it

was also the case for white migrants, who

became

known

as

‘‘hillbillies’’

and

‘‘Okies.’’ These images, however, did not

accurately describe all migrants, who were

a rather heterogeneous group. In fact,

many black migrants came from southern

towns and cities, not from farms, as was typ-

ically depicted (Alexander 1998; Marks

1989). Furthermore, migrants tended to be

more educated than the southerners they

left behind (Hamilton 1959; Lieberson

1978a;

Tolnay

1998a;

Vigdor

2002).

Tolnay (1998a), for example, finds that

black migrants were more likely to be liter-

ate than were nonmigratory southerners in

the early years of the Great Migration. In

later years, when the census reported years

of schooling, black migrants had signifi-

cantly higher educational attainment than

did nonmigrant southerners. Despite the

positive

selection,

and

consistent

with

migration theory (e.g., Lee 1966), migrants

were less likely to be literate and had fewer

years of schooling than did their black coun-

terparts in their northern and western desti-

nations (Tolnay 1998a).

Contrary to claims supported largely by

ethnographic

evidence

(e.g.,

Drake

and

Cayton 1962; Frazier 1932, 1939), more

recent researchers generally find that partici-

pants in the Great Migration fared relatively

well

in

their

non-southern

destinations,

despite a sometimes unfriendly welcoming.

Black migrants, who were relegated to the

lowest rungs of the occupational ladder, actu-

ally fared better than the northern-born black

population in many ways. Black migrants

were more likely to be employed and enjoyed

higher incomes than did northern-born blacks

(Lieberson 1978b; Lieberson and Wilkinson

1976; Long and Heltman 1975), and they

were less likely to receive public assistance

(Long 1974). The southern migrant advantage

for blacks in the North also extended to family

patterns, with lower levels of family disrup-

tion and higher percentages of children living

with two parents (Tolnay 1997, 1998b;

Tolnay and Crowder 1999; Wilson 2001).

For white southern migrants in the non-

South, it is more accurate to say that they

fared no worse, or not much worse, than their

northern-born

counterparts

(Berry

2000;

Gregory 1995).

What If They Had Never Left?

An important assumption, stated or implicit,

of much previous research is that participants

in the Great Migration fared better, socially

and economically, in their non-southern

Eichenlaub et al.

103

destinations than they would have if they had

remained in the South. This is considered

especially true for black migrants, for whom

the non-South offered a more congenial, if

not ideal, social climate, with greater social

and political freedoms and a reduced risk of

racially motivated violence. This assumption,

however, has not been examined empirically.

To determine the extent to which southern mi-

grants benefited from leaving the South, we

need to know what would have happened to

them if they had remained in their home

region. While it is obviously impossible to

know the outcomes of choices that were not

made, we use a comparative approach to

approximate as closely as possible the hypo-

thetical experiences of southern migrants had

they not exited the region. Specifically, we

compare the migrants with their contempora-

ries who chose to remain in the South—both

those who migrated internally within the

region and those who were ‘‘sedentary.’’

3

To be sure, this is a complex issue, given

the variety of migrants’ experiences and the

multidimensional outcomes that might be

used to measure whether moving to the

North was ‘‘worth it.’’ To limit the scope of

our investigation, we use a relatively narrow

set of outcomes that is primarily economic

in nature—employment status, earnings, and

occupational prestige. Migration theory and

evidence from prior research can be used to

support competing predictions about the rela-

tive economic success of the southerners who

moved north. We refer to these as the ‘‘con-

ventional view’’ and a ‘‘revisionist view.’’

The conventional view. The widely

shared assumption that southern migrants

benefited economically by moving to the

North is consistent with the rational deci-

sion-making process fundamental to much

migration theory. Because migrants decide

to move in an effort to maximize their eco-

nomic security and social comfort, they

should fare better than their counterparts

from the same area who stay behind.

According to Lee (1966), for example,

prospective migrants weigh the attributes at

their place of origin, along with the expected

opportunities at potential destinations, against

the cost of moving. Migrants are motivated by

the balance of push factors in their place of

origin and pull factors in potential destina-

tions. Both economic and social conditions

are important in migrants’ decision-making

process. Furthermore, Lee claims that mi-

grants will be positively selected from their

place of origin, especially those who are re-

sponding to pull factors, but that they will

have lower levels of human and social capital

than will the population they join in their des-

tination. As a result, migrants’ characteristics

(e.g., their economic well-being) should fall

between those of the population at origin

and the population at destination. Other,

more macro-level theories of migration, such

as those based on regional wage differentials,

also assume instrumental motives for popula-

tion movements. Such theories suggest that

inter-regional migrants to a higher-wage area

should enjoy greater economic success than

would the sedentary population remaining in

the lower-wage area from which they moved.

The well-documented, positive educational

selection of inter-regional migrants from the

South is also consistent with the conventional

view that migrants should have fared better in

the North than did their sedentary counterparts

in the South (Hamilton 1959; Lieberson

1978a;

Tolnay

1998a;

Vigdor

2002).

Similarly, the consistent findings that black

southern migrants in the North actually en-

joyed higher levels of employment, higher

wages, lower levels of poverty, lower levels

of public assistance, and more stable families

than did their northern-born neighbors, all

suggest the economic benefits of inter-

regional mobility during the Great Migration

(Lieberson 1978b; Lieberson and Wilkinson

1976; Long 1974; Long and Heltman 1975;

Tolnay 1997, 1998b; Tolnay and Crowder

1999; Wilson 2001).

The conventional view of the benefits of

inter-regional mobility during the Great

Migration

is

also

consistent

with

the

104

American Sociological Review 75(1)

substantial regional variation in economic

conditions that prevailed throughout the first

three quarters of the twentieth century.

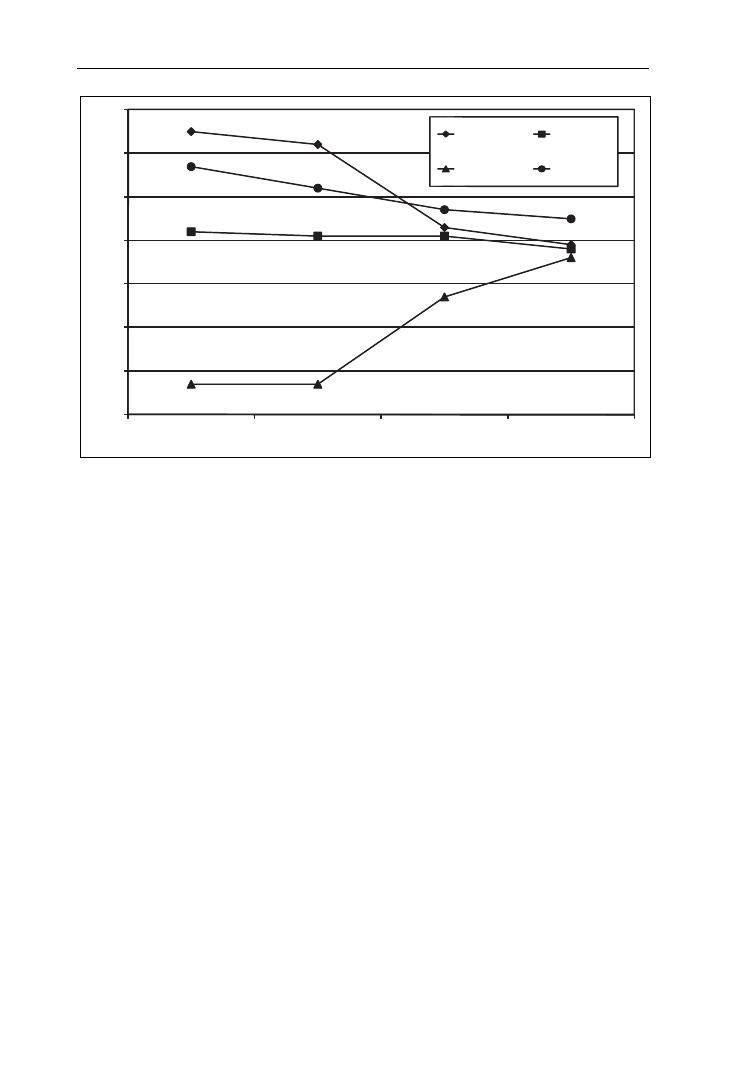

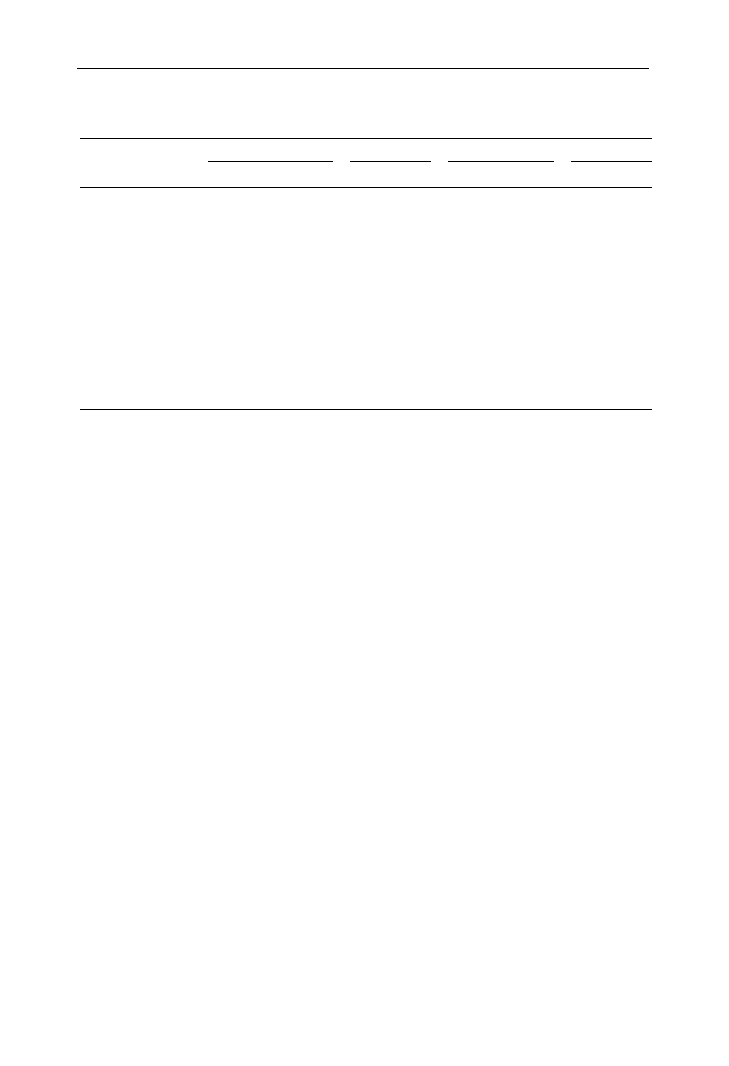

Regional income differentials are one indica-

tor of these differences. Figure 1 illustrates

regional income per capita at four time points

between 1920 and 1980, as a percentage of the

average U.S. per-capita income. This time

period encompasses most of the Great

Migration. Two important facts can be

gleaned from Figure 1. First, in all four time

periods, income was lower in the South than

in all other regions. Second, the southern

income disadvantage declined substantially

over time, especially after 1940. For example,

in 1940, per-capita income in the South was

only 67 percent of the U.S. average; by

1980, southern incomes had risen to 96 per-

cent of the national average. Despite the con-

vergence over time, there were still notable

differences in income levels in 1980, espe-

cially between the South and the West. The

existence of these regional wage differentials

alone would suggest that southerners who

left the region enjoyed higher incomes than

those who remained in the South—especially

prior to 1960. The substantial attenuation of

the differential, however, hints that the wage

advantage for southern migrants to the North

may have declined over time.

A revisionist view. It is possible that the

economic benefits from exiting the South

were neither as great, nor as universal, as

the conventional view suggests. An alterna-

tive framework, which we refer to as a ‘‘revi-

sionist view,’’ can be constructed from

migration theory and prior research that de-

scribes

possible

impacts

of

the

Great

Migration on opportunity structures in the

South and other regions.

As mentioned earlier, the neoclassical

economic theory of migration, which in-

cludes the influence of inter-regional wage

differentials on population redistribution,

suggests that, on average, migrants improve

their economic standing by moving from

low-wage to high-wage areas. However,

Todaro (1969; Harris and Todaro 1970)

notes that rural-to-urban migrants in the

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

1920

1940

1960

1980

Northeast

Midwest

South

West

Figure 1. Price Adjusted Income per Worker Relative to U.S. Average (U.S. average 5 100)

Source: Mitchener and McLean (1999:1019).

Eichenlaub et al.

105

less-developed world may actually experi-

ence a temporary decline in incomes as

they settle into their new destinations.

Such migrants are willing to tolerate this

short-term economic sacrifice as long as

they have a reasonable potential for ulti-

mately moving into better occupational po-

sitions with higher incomes (White and

Lindstrom

2005).

Important

parallels

between the Great Migration in the United

States and internal migration in the less-

developed world (e.g., the importance of

rural-to-urban movement and geographic

variation in employment opportunities and

incomes) suggest that short-term economic

sacrifices might have been required of

South-to-North migrants.

As the Great Migration progressed, both

the South and the North experienced important

changes that could have influenced the degree

to which inter-regional migrants benefited

from leaving the South. Some of these changes

can be linked directly to the Great Migration’s

demographic impact on both regions. Other

changes were less directly connected to the

Great Migration, if they were related at all.

The sheer magnitude of the regional redistri-

bution of population that resulted from the

Great Migration raises the possibility that it

affected local labor markets and wage rates.

For example, as the South lost more and more

of its labor force to out-migration, southern em-

ployers may have raised wages in an effort to

retain workers (Boustan 2009; Parr 1966), sup-

ported the expansion of educational opportuni-

ties (Margo 1991), or encouraged better

treatment of blacks (Margo 1991; Tolnay and

Beck 1992; Vigdor 2006). As a result of

improving economic and social conditions in

the South, partially triggered by the Great

Migration itself, any advantage enjoyed by

inter-regional migrants to the non-South may

have decreased over time. The convergence

of inter-regional wage differentials shown in

Figure 1 is consistent with this possibility.

Within the North, the accumulation of

southern-born migrants over time increased

the supply of workers and may have created

a downward pressure on employment and

wages (Boustan 2009; Boustan, Fishback,

and Kantor 2007; Massey 1990; Vigdor

2006). As a result, later migrants from the

South may have enjoyed a less favorable eco-

nomic opportunity structure than did their fel-

low southerners who preceded them and,

therefore, might have benefited less from leav-

ing the South. Furthermore, the population

changes produced by the Great Migration in

the North likely contributed to other major

transformations, such as ‘‘white flight’’ from

central cities to suburbs (Boustan forthcom-

ing) and the economic decline of inner cities

(Kasarda 1985, 1989), both of which had an

especially deleterious impact on northern

blacks’ economic well-being (Massey and

Denton 1993; Wilson 1987).

4

The rapid growth of the southern-born

population in the North also expanded the

social networks and contacts that newly

arrived migrants in the North, as well as

potential migrants still in the South, could

rely

on

for

information

and

support.

Migration research and theory emphasizes

the importance of family and friendship

networks

for

international

migration

(Massey

1990;

White

and

Lindstrom

2005), but the same processes operate for

internal migration as well (Tilly 1968). By

reducing the cost and difficulty of inter-

regional relocation, strengthened social net-

works could have reduced the selectivity of

migrants from the South. This is certainly

consistent with previous research findings

indicating that the positive educational

selection of migrants from the South

declined over time during the twentieth

century (Tolnay 1998a). On the one hand,

by helping migrants adapt to their new loca-

tions, stronger networks could have led to

more favorable post-migration outcomes.

On the other hand, stronger networks of

family and friends, by weakening the

migrant selection process, may have con-

tributed to worse post-migration outcomes.

To be sure, these conflicting perspectives

could be used to support substantially

106

American Sociological Review 75(1)

different

predictions

about

the

relative

economic well-being of southern migrants

in

the

North

versus

southerners

who

remained in the South. Yet, by distinguishing

between short- and long-term comparisons of

migrants who left the region and those who

stayed in the South, and by taking time

period into consideration, we believe that

the conventional and revisionist views can

be combined to yield a coherent set of gen-

eral hypotheses faithful to both migration

theory and our current understanding of the

Great Migration. First, other things being

equal, we expect to find that southern mi-

grants enjoyed an economic advantage over

southerners who remained in their home

region. Second, among southerners who did

not leave the region, those who migrated

within the South should compare more favor-

ably with the inter-regional migrants than

will those who did not migrate. Third, the

long-term benefits of migration should be

greater than the short-term benefits. Fourth,

because of changing social and economic

conditions in the North and South, some of

which resulted directly or indirectly from

the Great Migration, we expect the economic

benefits of inter-regional migration to have

been greater during the earlier stages of the

Great Migration than near its culmination.

DATA, VARIABLES, METHOD

Data

Data for this study come from the public use

microdata samples (PUMS) of the decennial

U.S. population censuses (Ruggles et al.

2004) for 1940, 1950, 1970, and 1980.

5

Using

data from these years, we compare economic

outcomes across three groups of southern-

born males: (1) South-to-North/West inter-

regional migrants, (2) southern intra-regional

migrants (i.e., those who moved across state

lines within the South), and (3) the sedentary

southern population. We use the 1940 and

1970 files to examine the short-term benefits

of migration for recent migrants (i.e., migrants

who moved within a five-year period preceding

the census). These samples are restricted to

southern-born white and black males who

were 25 to 60 years old

6

at the time of enumer-

ation and were living in the South five years

before the census. We use the 1950 and 1980

PUMS data to estimate long-term benefits of

migration. For the latter analysis, we restrict

our samples to southern-born white and black

males who were 35 to 60 years old and living

in their state of enumeration five years before

the census for 1980, or one year before the cen-

sus for 1950.

7

This sample provides a rough

approximation of the long-term benefits for

the migrants in our primary analyses for 1940

and 1970. For all years, we exclude individuals

who reported that they were currently enrolled

in school or serving in the military. For the pur-

poses of the analyses, we define the South as the

11 states of the confederacy, plus Kentucky and

Oklahoma. We use the census definitions for

the West, Northeast, and Midwest regions,

which we collapse into one region that we refer

to as the North. In addition to the states that fall

into the census definition of Northeast and

Midwest, we include Delaware, Maryland,

Washington, DC, and West Virginia, which

the census defines as southern, in our North

category.

8

Our analyses are limited to men only.

While women played an important role in

the decision to migrate, their migration behav-

iors were often tied to those of their husbands.

Recent research indicates that during the Great

Migration, women’s outcomes were shaped by

marital status and, for married women, related

to their husbands’ outcomes (White et al.

2005). Given the importance of ‘‘tied migra-

tion’’ to women’s mobility experiences, espe-

cially before 1970, a useful exploration of the

economic

benefits

following

the

inter-

regional migration of southern women would

require its own thorough investigation.

Variables

Dependent variables. We use four depen-

dent variables to measure the economic and

Eichenlaub et al.

107

occupational benefit of migration in this anal-

ysis: employment status, income, relative

income, and occupational status. Employment

status is a dichotomous variable that distin-

guishes those who reported being in the labor

force and employed from those who reported

being in the labor force and unemployed dur-

ing the week prior to census enumeration.

9

The second dependent variable is absolute

income. For 1940, this variable includes

income from wages, salaries, cash bonuses,

tips, and other money from a respondent’s

employer during the preceding calendar

year. For 1950, 1970, and 1980, we add

income from personal business and farm

activity to the original income variable.

10

To account for regional variation in income

and cost of living, the third dependent vari-

able is an alternative measure of income.

We measure relative income as the differ-

ence between individuals’ reported income

and the state-level median value of income

for males of their own race (black or white).

Positive values on this variable indicate that

a respondent earned an income higher than

his race’s median income in that state.

Negative values indicate that a respondent’s

reported income was lower than his race’s

median income in that state.

11

The fourth

dependent variable is occupational status, as

measured by the Duncan Socioeconomic

Index (SEI), which assigns a prestige score

for occupations based on the income and

educational attainment associated with par-

ticular occupations in 1950 (Duncan 1961).

Scores range from 3 to 96, with higher scores

representing occupations with greater levels

of prestige. Using a variety of economic out-

come measures, rather than a single indica-

tor, allows us to more thoroughly explore

the relative advantage or disadvantage expe-

rienced by individuals who left the South

during the Great Migration.

Independent variables. The key inde-

pendent variables describe an individual’s

migration history. For the analysis of short-

term benefits of migration in 1940 and

1970, we identify two groups of inter-

regional migrants—individuals who moved

from a southern state to the North or

Midwest, migrants to the North, and those

who moved from a southern state to the

West, migrants to the West. Among individ-

uals who remained in the South, we differen-

tiate migrants within the South, who moved

between southern states between 1935 and

1940 or between 1965 and 1970, from seden-

tary southerners, who remained in the same

state during the same five-year intervals.

12

For the analysis examining long-term out-

comes of migration in 1950 and 1980, we

use a different measure of migration history.

All men in this analysis are southern-born,

but we limit our sample to those who were liv-

ing in their state of enumeration one year prior

to the census in 1950 and five years prior to the

census in 1980. For example, a southern-born

man who was enumerated in New York in

1950 and also lived in New York in 1949

would be included in the migrant to the

North group. If this man lived in any state

other than New York in 1949, southern or oth-

erwise, he would not be included in the analy-

sis. We use this same approach to define

migrants within the South and migrants to

the West. Sedentary southerners, for this anal-

ysis, are identified as those who were living in

their state of birth at the time of enumeration

and at the prior time point (i.e., one year earlier

for the 1950 census and five years earlier for

the 1980 census). Men who moved across state

boundaries between 1949 and 1950 or

between 1975 and 1980 are excluded from

the analysis. Throughout the article, migrants

within the South serves as the reference cate-

gory. In supplementary analyses, we shifted

the reference category to sedentary southern-

ers to test for the significance of differences

between this group and inter-regional mi-

grants. Although we do not present full results

from the auxiliary analyses here, we use these

results to denote the statistical significance of

differences between groups in the tables.

In addition to these key independent

variables, we include a limited number of

108

American Sociological Review 75(1)

control variables in the analyses to avoid

drawing incorrect conclusions that reflect

compositional differences among the vari-

ous groups. That is, these variables may

affect economic outcomes for migrants

while also varying by migration history.

We include six control variables in models

examining both short-term (in 1940 and

1970) and long-term (in 1950 and 1980)

outcomes for migrants. To account for

a possible curvilinear effect of age on eco-

nomic outcomes, we include both age

(in years) and its square, age

2

. We also con-

trol for the effect of co-residing with

a spouse, which may reflect greater family

obligations or the possibility of a positive

selection into marriage. Unmarried men

and married men who were not living with

their

spouse

serve

as

the

referent.

Education, as measured by years of school-

ing completed, is an important predictor of

economic outcomes and is also included in

the

models.

13

Finally,

we

distinguish

between individuals who were residing in

metropolitan areas at the time of enumera-

tion and those who were not (the reference

group), as well as those who were living

on a farm at the time of enumeration versus

those who were not (the reference group).

In addition to these six variables, in our

models predicting relative income, we

include a seventh covariate, race-specific

state median income, to control for the

absolute level of income for each state.

Method

The primary focus of our study is the compar-

ison of economic outcomes between those

who left the South and those who remained

behind. We use binary logistic regression for

our models predicting employment status,

a dichotomous measure. For models predict-

ing income, relative income, and occupational

status, all continuous variables, we use ordi-

nary least squares regression. For both meas-

ures of income, we limit our analysis to

respondents who reported a non-zero income

for the year prior to the census. For SEI, we

limit our analysis to respondents who were

in the labor force and reported an SEI score,

whether or not they were employed at the

time of enumeration.

FINDINGS

Short-Term Benefits of Migration

for Recent Migrants

The bivariate relationships between migra-

tion history and post-migration economic

outcomes are described in Table A1 of the

Appendix. Because they are more appropri-

ate for answering our central research ques-

tions, we move directly to the results from

our multivariate analyses to determine the

net differences by migration history in eco-

nomic outcomes.

1940. Table 1 presents the findings from

our analysis of all post-migration dependent

variables for both blacks and whites in

1940. Results from the analysis of economic

outcomes for blacks are displayed on the left-

hand side of the table. For current employ-

ment status, we find that migrants to the

West were less likely to have been employed

the week prior to census enumeration than

were migrants within the South and seden-

tary southerners. Migrants to the North

were no more likely to have been employed

than were migrants within the South, and

they were significantly less likely to have

been employed when compared with seden-

tary southerners.

Turning to the evidence for income differ-

entials, we find that despite a large regional

variation in income in 1940 (see Figure 1),

black migrants to the West did not enjoy an

income advantage over blacks who moved

within the South during the same time period

or over sedentary southerners. Migrants to

the North, by contrast, reported significantly

higher incomes than both groups who re-

mained in the South, consistent with the evi-

dence reported in Figure 1.

Eichenlaub et al.

109

Table

1.

Results

from

Regression

Analysis

of

Selected

Economic

Characteristics

for

Southern-Born

Males,

Age

25

to

60

Years,

1940

Blacks

Whites

Employment

Status

Income

Relative

Income

SEI

Employment

Status

Income

Relative

Income

SEI

Migrants

to

West

–.44

*

z

21.93

–153.88

*

z

–3.90

z

–.92

*

z

–228.18

*

z

–379.96

*

z

–10.60

*

z

(.20)

(59.03)

(58.37)

(1.96)

(.11)

(54.10)

(95.41)

(1.11)

Migrants

to

North

–.34

z

113.33

*

z

–91.58

–.69

–.34

z

–22.64

–175.64

*

–4.71

*

z

(.24)

(34.55)

(69.61)

(1.04)

(.18)

(63.99)

(74.52)

(1.03)

Sedentary

Southerners

.07

–22.67

–15.92

–.13

.06

–92.20

*

–93.12

*

–.61

(.18)

(21.29)

(22.26)

(.65)

(.09)

(21.68)

(22.62)

(.50)

Age

.07

*

17.59

*

17.87

*

.44

*

.04

*

82.96

*

82.91

*

.99

*

(.02)

(2.25)

(2.10)

(.08)

(.01)

(7.15)

(7.00)

(.06)

Age

2

–.00

*

–.19

*

–.19

*

–.00

*

–.00

*

–.84

*

–.84

*

–.01

*

(.00)

(.03)

(.03)

(.00)

(.00)

(.09)

(.09)

(.00)

Married

1.03

*

63.60

*

67.48

*

.34

1.29

*

225.18

*

230.01

*

.80

*

(.06)

(8.11)

(7.71)

(.19)

(.04)

(14.25)

(14.53)

(.22)

Education

.06

*

18.65

*

18.48

*

1.13

*

.11

*

95.66

*

95.89

*

2.76

*

(.01)

(1.75)

(1.53)

(.07)

(.01)

(2.18)

(1.86)

(.04)

Metropolitan

Status

–.02

111.51

*

102.48

*

–.29

.11

*

320.36

*

306.18

*

3.28

*

(.09)

(11.05)

(10.14)

(.30)

(.05)

(16.93)

(13.82)

(.29)

Farm

Status

1.70

*

–160.90

*

–153.91

*

–.45

.95

*

–336.48

*

–325.00

*

–12.16

*

(.08)

(9.85)

(10.06)

(.35)

(.05)

(15.91)

(15.97)

(.59)

Median

State

Income

–.41

*

–.55

*

(.14)

(.10)

Intercept

–.71

*

–67.45

–294.04

*

–2.52

–.32

–1771.29

*

–2149.74

*

–15.92

*

(.31)

(51.19)

(77.81)

(2.24)

(.27)

(141.53)

(149.84)

(1.24)

Pseudo

R

2

/R

2

.11

.16

.15

.10

.10

.33

.33

.38

N

18,193

11,723

11,723

16,968

52,803

33,132

33,132

49,795

Note:

Robust

standard

errors

are

in

parentheses

and

are

clustered

on

current

state

of

residence.

*

p

\

.05

(two-tailed

tests);

z

denotes

coefficient

is

significantly

different

(p

\

.05)

from

coefficient

for

sedentary

southerners.

110

When we account for interstate variation

in median income levels, we find that mi-

grants to the West experienced a significant

income disadvantage compared with both

migrants within the South (the reference

group)

and

sedentary

southerners.

The

advantage in absolute income for migrants

to the North that we noted in the prior model

disappears when we adjust for variation in

mean incomes across states. We find no dif-

ferences between relative income for mi-

grants to the North and either group that

remained in the South.

Finally, turning to the model predicting

occupational status as measured by Duncan’s

SEI score, we continue to find that, in the

short-term, inter-regional black migrants in

1940 did not enjoy an advantage compared

with their contemporaries who remained in

the South. Adjusted SEI scores for both groups

of inter-regional migrants are statistically

equivalent to SEI scores for migrants within

the South. Furthermore, migrants to the West

reported significantly lower SEI scores than

did sedentary southerners.

The right-hand side of Table 1 presents re-

sults from parallel analyses for whites in

1940. Similar to blacks, white men who left

the South between 1935 and 1940 did not

experience short-term economic benefits

from migration. White migrants to the West

were significantly less likely to have been

employed than were migrants within the

South, the reference group (odds ratio of

.40), and sedentary southerners (odds ratio

of .38).

14

White migrants to the North were

also less likely to have been employed than

were sedentary southerners (odds ratio of

.67), but they are statistically equivalent to

migrants within the South.

White inter-regional migrants did not enjoy

an advantage in absolute income when com-

pared with migrants within the South or seden-

tary southerners, a surprising result given the

considerable variation in regional income lev-

els reported in Figure 1. Migrants to the West

actually earned less than migrants within the

South and sedentary southerners (b 5 –$228

and –$136 annually, respectively). The median

income for white men in the 1940 sample was

only $800, so these income differentials are

substantial. When we control for interstate

income variation, we find that both inter-

regional migrant groups earned significantly

less compared with their race-specific state

median income than did the reference group,

migrants within the South. Additionally, we

find that migrants to the West, compared with

sedentary southerners, experienced lower rela-

tive income.

Finally, the last column of Table 1 reveals

no advantage in occupational status for whites

who left the South between 1935 and 1940. In

fact, we find that migrants to both the West

and the North had lower SEI scores compared

with migrants within the South (b 5 –10.60

and b 5 –4.71, respectively), with a mean

value for SEI of 27.25 for whites in 1940.

Both inter-regional migrant groups also re-

ported significantly lower occupational status

than Southerners who did not move.

Overall, our findings indicate that, on aver-

age, migrants of both races who left the South

for either the North or the West between 1935

and 1940 did not benefit in terms of employ-

ment status, income, or occupational status,

at least in the short run. In many instances,

we find that inter-regional migrants actually

were worse off than those who migrated within

the South and those who did not migrate.

These findings fail to support our hypothesis

that migrants who left the South during this

earlier time period fared better than those

who remained in the South.

1970. Table 2 presents the findings from

analyses for recent migrants in 1970. The

findings for black males reveal that migrants

to the West were less likely to be employed

than were both migrants within the South

(odds ratio of .74) and sedentary southerners

(odds ratio of .58). The likelihood of employ-

ment for migrants to the North is statistically

equivalent to that for migrants within the

South, although it is significantly lower

than the likelihood of employment for

Eichenlaub et al.

111

Table

2.

Results

from

Regression

Analysis

of

Selected

Economic

Characteristics

for

Southern-Born

Males,

Age

25

to

60

Years,

1970

Blacks

Whites

Employment

Status

Income

Relative

Income

SEI

Employment

Status

Income

Relative

Income

SEI

Migrants

to

West

–.30

*

z

798.52

*

z

–510.76

–1.23

–.42

*

z

282.97

–748.97

*

z

–2.34

*

(.15)

(216.59)

(336.64)

(1.20)

(.14)

(204.03)

(257.49)

(1.06)

Migrants

to

North

–.03

z

1196.19

*

z

–106.61

.60

z

.05

z

884.94

*

z

–132.38

–1.86

(.15)

(246.50)

(341.81)

(1.49)

(.11)

(198.93)

(171.55)

(1.39)

Sedentary

Southerners

.25

*

–38.51

–27.55

–2.18

*

.28

*

153.68

147.83

–2.82

*

(.11)

(187.96)

(182.38)

(.86)

(.05)

(93.83)

(114.38)

(.38)

Age

.10

*

168.80

*

165.50

*

.28

*

.12

*

649.69

*

646.91

*

1.01

*

(.01)

(11.92)

(11.76)

(.07)

(.01)

(22.23)

(22.36)

(.05)

Age

2

–.00

*

–1.84

*

–1.82

*

–.00

*

–.00

*

–6.82

*

–6.80

*

–.01

*

(.00)

(.16)

(.16)

(.00)

(.00)

(.24)

(.24)

(.00)

Married

1.46

*

1100.54

*

1105.90

*

1.75

*

1.70

*

2106.35

*

2135.13

*

2.13

*

(.06)

(64.13)

(61.82)

(.20)

(.05)

(53.83)

(51.38)

(.18)

Education

.09

*

245.22

*

237.78

*

2.05

*

.16

*

689.19

*

685.47

*

3.74

*

(.00)

(6.67)

(6.88)

(.03)

(.01)

(10.35)

(10.85)

(.04)

Metropolitan

Status

.09

866.00

*

770.05

*

.91

*

.18

*

1373.63

*

1240.12

*

2.81

*

(.05)

(63.28)

(67.28)

(.35)

(.06)

(66.39)

(92.46)

(.32)

Metropolitan

Status

Missing

.01

440.23

*

418.06

*

.71

*

–.06

671.11

*

630.20

*

1.13

*

(.04)

(114.16)

(96.19)

(.28)

(.09)

(142.40)

(126.24)

(.56)

Farm

Status

.03

–865.23

*

–776.00

*

–1.36

*

.02

–992.15

*

–851.60

*

–11.11

*

(.09)

(100.49)

(68.52)

(.39)

(.05)

(88.47)

(82.03)

(.82)

Median

State

Income

–.48

*

–.30

*

(.08)

(.06)

Intercept

–1.87

*

–2431.89

*

–4453.93

*

–4.60

*

–2.56

*

–16133.62

*

–21296.88

*

–25.48

*

(.24)

(312.09)

(297.86)

(1.56)

(.24)

(575.77)

(998.94)

(1.19)

Pseudo

R

2

/R

2

.11

.16

.14

.21

.16

.20

.20

.36

N

49,433

44,114

44,114

42,546

226,369

212,834

212,834

208,740

Note:

Robust

standard

errors

are

in

parentheses

and

are

clustered

on

current

state

of

residence.

*p

\

.05

(two-tailed

tests);

z

denotes

coefficient

is

significantly

different

(p

\

.05)

from

coefficient

for

sedentary

southerners.

112

sedentary southerners (odds ratio of .76).

Black inter-regional migrants earned signifi-

cantly higher absolute incomes than did

both groups who remained in the South,

which is consistent with the regional varia-

tion in income demonstrated in Figure 1.

When controlling for interstate variation in

income, however, the observed income

advantage disappears for both groups who

left the South. Finally, the Duncan SEI scores

of black migrants who left the South between

1965 and 1970 are statistically equivalent to

those observed for blacks who moved within

the South.

The comparable results for whites in 1970

are reported in the right-hand side of Table 2.

Leaving the South between 1965 and 1970 re-

sulted in no employment advantage for whites.

In fact, migrants to the West fared signifi-

cantly worse than both sedentary southerners

and migrants within the South. The results

for absolute income indicate a significant

advantage for white migrants to the North,

who earned significantly higher annual in-

comes than both migrants within the South

(b 5 $885) and sedentary southerners

(b 5 $731). This was a substantial income ad-

vantage, given that the median income for this

sample of white men in 1970 was $7,450.

Migrants to the West, by contrast, enjoyed

no income advantage compared with individu-

als who remained in the South—migrants or

nonmigrants. Controlling for interstate differ-

ences in median income levels erases the

income advantage for white migrants to the

North. In addition, the relative income level

for migrants to the West drops below that for

both migrants within the South (b 5 –$749)

and sedentary southerners (b 5 –$897). The

findings for occupational status reveal a signif-

icant disadvantage for migrants to the West (b

5 –2.34) compared with men who moved

within the South.

In summary, we again find no substantial

short-term advantage for migrants who left

the South compared with migrants within

the South between 1965 and 1970. The

only exceptions are the significantly higher

absolute incomes enjoyed by black inter-

regional migrants and white migrants to the

North, neither of which holds after adjusting

for interstate differences in median income

levels. In all other cases, inter-regional mi-

grants, both black and white, were either sta-

tistically equivalent to migrants within the

South or fared worse than those who moved

within Dixie during the same time period.

Long-Term Benefits of Migration

The finding that short-term economic bene-

fits did not accompany inter-regional migra-

tion for either 1940 or 1970 raises the

interesting question of comparable benefits

(or lack of them) over the long term.

Perhaps the findings in Tables 1 and 2 reflect

a penalty that recent migrants must pay for

the disruptive consequences of their inter-

regional relocation. That is, realizing the

benefits of migration may require the passage

of time.

15

To examine this possibility, we

moved our analysis forward 10 years and

restricted our sample to southern-born men

who had been living in the same state for at

least one year before the 1950 census and

at least five years before the 1980 census.

We also restricted our sample to men ages

35 to 60 in an attempt to roughly estimate

long-term benefits for those in our 1940

and 1970 samples.

16

An important caveat

must be made regarding our analysis of the

long-term benefits of inter-regional migra-

tion: Although some of the recent migrants

included in our analyses of the short-term

benefits from inter-regional migration in

1940 and 1970 may also be included among

the samples used to investigate the long-term

benefits, the alignment of cohorts is obvi-

ously imperfect. Nevertheless, we believe

that these supplementary findings are at least

suggestive, if not definitive, regarding the

possible long-term benefits accruing from

movement out of the South.

1950. Table 3 shows results from analy-

ses for blacks and whites using the same

Eichenlaub et al.

113

Table

3.

Results

from

Regression

Analysis

of

Selected

Economic

Characteristics

for

Southern-Born

Black

and

White

Males,

Age

35

to

60

Years,

Who

Were

Living

in

Their

Current

State

of

Residence

One

Year

Earlier,

1950

Blacks

Whites

Employment

Status

Income

Relative

Income

SEI

Employment

Status

Income

Relative

Income

SEI

Migrants

to

West

–.53

*

z

646.03

*

z

125.38

.66

.01

–150.05

–511.47

*

–7.03

*

z

(.18)

(121.05)

(118.59)

(1.42)

(.24)

(134.12)

(184.62)

(1.01)

Migrants

to

North

–.07

z

503.93

*

z

5.76

.92

.53

*

z

–27.68

z

–329.22

*

–4.84

*

z

(.20)

(72.84)

(92.77)

(1.04)

(.15)

(112.22)

(109.01)

(.93)

Sedentary

Southerners

.37

*

–77.31

*

–49.26

1.08

.21

*

–331.62

*

–308.11

*

–2.21

*

(.18)

(25.69)

(32.35)

(.76)

(.08)

(73.94)

(75.51)

(.60)

Age

.24

*

84.90

*

78.16

*

.29

.30

*

164.02

*

160.72

*

.93

*

(.09)

(31.97)

(31.35)

(.44)

(.08)

(30.20)

(29.89)

(.39)

Age

2

–.00

*

–.95

*

–.88

*

–.00

–.00

*

–1.65

*

–1.62

*

–.01

(.00)

(.35)

(.34)

(.00)

(.00)

(.33)

(.33)

(.00)

Married

1.21

*

379.61

*

383.03

*

1.22

1.59

*

689.60

*

701.53

*

3.74

*

(.10)

(40.79)

(39.42)

(.61)

(.08)

(77.08)

(77.74)

(.86)

Education

.05

*

41.88

*

39.20

*

1.18

*

.12

*

208.78

*

208.72

*

2.85

*

(.02)

(6.23)

(6.19)

(.12)

(.01)

(8.66)

(7.98)

(.07)

Metropolitan

Status

.35

*

300.30

*

271.64

*

.66

.08

473.98

*

420.98

*

2.14

*

(.17)

(36.90)

(37.23)

(.65)

(.12)

(48.27)

(54.99)

(.62)

Farm

Status

1.77

*

–491.90

*

–452.63

*

–1.52

*

1.08

*

–664.69

*

–629.84

*

–13.77

*

(.28)

(59.77)

(58.97)

(.63)

(.10)

(61.90)

(59.52)

(.76)

Median

State

Income

–.51

*

–.56

*

(.07)

(.06)

Intercept

–4.98

*

–983.60

–1414.40

–1.48

–6.60

*

–3336.21

*

–4323.11

*

–15.75

(2.09)

(702.90)

(713.97)

(9.96)

(1.77)

(710.11)

(745.31)

(8.66)

Pseudo

R

2

/R

2

.11

.26

.13

.09

.15

.23

.22

.33

N

5,077

4,545

4,545

4,589

13,938

12,671

12,671

12,915

Note:

Robust

standard

errors

are

in

parentheses

and

are

clustered

on

current

state

of

residence.

*

p

\

.05

(two-tailed

tests);

z

denotes

coefficient

is

significantly

different

(p

\

.05)

from

coefficient

for

sedentary

southerners.

114

economic

outcomes

considered

earlier.

Despite having lived in their state of resi-

dence for at least one year, black inter-

regional migrants were still less likely to

have been employed than were sedentary

southerners. Migrants to the West were

also significantly less likely to have been

employed compared with migrants within

the South (odds ratio 5 .59). Black migrants

to the North were no more or less likely to

have been employed than the reference

group. Black inter-regional migrants did,

however, enjoy a significant and substantial

absolute income advantage compared with

both groups that remained in the South.

Again, however, this income advantage is

to be expected, given the large regional

wage differentials during this time period.

In fact, after adjusting for these differen-

tials, we find no advantage in relative

income for inter-regional migrants. Finally,

we see that in terms of occupational status,

blacks who left the South fared no better

(and no worse) than either those who moved

within the South or those who did not move.

Parallel results for whites are presented in

the right-hand side of Table 3. Migrants to

the North were more likely to have been em-

ployed than were both migrants within the

South (odds ratio 5 1.70) and sedentary

southerners (odds ratio 5 1.38). Migrants to

the West, by contrast, did not enjoy an

employment

advantage

when

compared

with either group that remained in the

South. While white migrants to the North

were more likely to have been employed in

1950, they earned no more than did those

who migrated within the South during this

time period, despite large regional income

differentials. The same holds true for whites

who moved to the West, compared with

those who chose destinations within the

South. Whites who moved north did enjoy

a significant income advantage over the sed-

entary southern group. When we adjust for

interstate income differences, however, both

groups of inter-regional migrants fared sig-

nificantly worse than did those who moved

within the South. There are no differences

in relative income between either inter-

regional

migrant

group

and

sedentary

Southerners. Finally, both groups of white

migrants who left the South reported signifi-

cantly lower SEI values than did migrants

within the South and sedentary southerners.

Consistent with our findings for 1940, the

evidence from this supplementary analysis of

possible long-term benefits for inter-regional

migrants points to no consistent or significant

economic advantage gained by leaving the

South in the mid-twentieth century. If any-

thing, the results, like those for 1940, are

consistent with a modest disadvantage asso-

ciated with inter-regional migration versus

intra-regional migration.

1980. Table 4 presents results from a simi-

lar analysis of the long-term benefits of inter-

regional migration for southern-born males in

1980. Consistent with the general thread of

evidence that has emerged thus far from our

statistical analyses, we find that black inter-

regional migrants were less likely to have

been employed than migrants within the

South and sedentary southerners. Both inter-

regional migrant groups enjoyed a statistically

significant, absolute income advantage com-

pared with migrants within the South (b 5

$2,411 annually for migrants to the West; b

5 $2,230 for migrants to the North). These

are substantial differences given that the

median income for blacks in the 1980 analysis

was $12,005. When we turn to the results for

relative income, however, the advantage

once again disappears. In fact, both groups

of blacks that left the South now fare signifi-

cantly worse than the reference group.

Finally, black migrants who left the South

before 1975 failed to enjoy an advantage com-

pared with migrants within the South in terms

of occupational status.

Turning to the analyses for whites in

1980, we find that neither inter-regional

migrant group enjoyed an employment

advantage compared with either migrants

within the South or nonmigrants. White

Eichenlaub et al.

115

Table

4.

Results

from

Regression

Analysis

of

Selected

Economic

Characteristics

for

Southern-Born

Black

and

White

Males,

Age

35

to

60

Years,

Who

Were

Living

in

Their

Current

State

of

Residence

Five

Years

Earlier,

1980

Blacks

Whites

Employment

Status

Income

Relative

Income

SEI

Employment

Status

Income

Relative

Income

SEI

Migrants

to

West

–.50

*

z

2411.00

*

z

–792.56

*

.56

z

–.34

*

z

318.21

z

–1445.81

*

–2.96

*

z

(.08)

(442.70)

(349.62)

(.57)

(.10)

(520.29)

(361.39)

(.39)

Migrants

to

North

–.44

*

z

2229.62

*

z

–693.72

*

–.23

–.06

1149.57

z

–477.14

–3.74

*

z

(.10)

(614.75)

(327.42)

(.64)

(.10)

(604.15)

(410.66)

(.79)

Sedentary

Southerners

–.14

*

–742.90

*

–662.87

*

–.57

.01

–1012.08

*

–1113.54

*

–1.54

*

(.07)

(342.16)

(299.58)

(.47)

(.04)

(316.41)

(225.98)

(.29)

Age

.20

*

352.15

*

341.38

*

.41

*

.23

*

1234.61

*

1230.80

*

.83

*

(.02)

(102.93)

(104.10)

(.19)

(.02)

(72.11)

(70.54)

(.11)

Age

2

–.00

*

–3.54

*

–3.46

*

–.00

–.00

*

–12.51

*

–12.48

*

–.01

*

(.00)

(1.07)

(1.09)

(.00)

(.00)

(.75)

(.74)

(.00)

Married

1.18

*

3015.50

*

2998.84

*

2.22

*

1.25

*

4181.63

*

4213.30

*

2.77

*

(.04)

(110.08)

(107.79)

(.27)

(.03)

(126.15)

(120.80)

(.16)

Education

.10

*

619.02

*

609.72

*

2.37

*

.15

*

1376.99

*

1371.72

*

3.49

*

(.01)

(30.94)

(33.38)

(.09)

(.01)

(25.77)

(23.60)

(.04)

Metropolitan

Status

.19

*

1798.52

*

1284.91

*

1.34

*

.35

*

2824.49

*

2369.95

*

2.66

*

(.06)

(196.36)

(192.24)

(.47)

(.08)

(307.88)

(220.45)

(.36)

Metropolitan

Status

Missing

.04

209.53

45.38

.20

.06

615.03

*

452.90

*

–.09

(.09)

(193.58)

(225.82)

(.57)

(.08)

(286.96)

(220.29)

(.31)

Farm

Status

.49

*

354.66

412.25

–3.39

*

.45

*

287.12

363.13

–9.43

*

(.20)

(689.19)

(663.17)

(1.13)

(.06)

(193.37)

(187.35)

(.65)

Median

State

Income

–.35

*

–.39

*

(.06)

(.07)

Intercept

–4.23

*

–5757.15

*

–11693.97

*

–11.78

*

–4.76

*

–31099.68

*

–41010.44

*

–25.33

*

(.48)

(2600.33)

(2631.70)

(4.56)

(.38)

(1889.84)

(2016.05)

(2.77)

Pseudo

R

2

/R

2

.10

.16

.10

.19

.13

.17

.16

.31

N

45,971

36,867

36,867

36,831

154,039

137,453

137,453

135,667

Note:

Robust

standard

errors

are

in

parentheses

and

are

clustered

on

current

state

of

residence.

*p

\

.05

(two-tailed

tests);

z

denotes

coefficient

is

significantly

different

(p

\

.05)

from

coefficient

for

sedentary

southerners.

116

migrants to the West, in fact, were less

likely to have been employed than both

groups

that

remained

in

the

South.

Although inter-regional migrants earned

more than whites who remained in the

South and did not move, their incomes in

1980 are statistically equivalent to the ref-

erence group’s, those who moved within

the South. Once we adjust for state differen-

ces in median income, however, we find

that whites who moved west earned signif-

icantly less than the reference group (b 5

–$1,446).

Finally,

both

inter-regional

migrant groups have lower average occupa-

tional status scores than do both migrants

within the South and sedentary southerners.

Consistent with the evidence for 1950, the

findings for both blacks and whites in 1980

indicate that southern males who moved to

the North or the West enjoyed no long-term

benefits to migration, on average, when com-

pared with migrants within the South. The

main exception to this general pattern is for

black inter-regional migrants in 1950 and

1980, who earned higher incomes than indi-

viduals who moved within the South. In all

cases,

however,

the

income

advantage

disappears when we adjust for interstate

wage differentials. In fact, as we found for

short-term outcomes (see Tables 1 and 2),

in many cases inter-regional migrants fared

worse in the long-term than did those who

migrated within the South and, in some

cases, those who did not move at all.

Synopsis

The statistical evidence presented in Tables 1

through 4 is extensive, involving four sepa-

rate time periods for short- and long-term

benefits, two races, two groups of inter-

regional migrants, and four post-migration

dependent variables. To help distill the evi-

dence, and to facilitate a general conclusion,

Table 5 summarizes our results by concen-

trating on the comparisons between inter-

regional migrants and intra-regional mi-

grants, who represent the most appropriate

comparison group. A general conclusion

can be gleaned from a quick review of

Table 5: that is, the cells are overwhelmingly

dominated by zeroes and minuses (indicating

a nonsignificant difference or a statistically

significant disadvantage, respectively, for

Table 5. Summary of Advantage and Disadvantage Experienced by Inter-regional Migrants

Compared with Migrants within the South

Employment Status

Income

Relative Income

SEI

Black

White

Black

White

Black

White

Black

White

Short-Term Benefits

1940

To West

–

–

0

–

–

–

0

–

To North

0

0

1

0

0

–

0

–

1970

To West

–

–

1

0

0

–

0

–

To North

0

0

1

1

0

0

0

0

Long-Term Benefits

1950

To West

–

0

1

0

0

–

0

–

To North

0

1

1

0

0

–

0

–

1980

To West

–

–

1

0

–

–

0

–

To North

–

0

1

0

–

0

0

–

Note: ‘‘1’’ represents a significant advantage (p \ .05) for inter-regional migrant group; ‘‘–’’ represents

a significant disadvantage (p \ .05) for inter-regional migrant group; ‘‘0’’ represents the absence of

a significant difference between inter-regional migrant group compared with migrants within the South.

Eichenlaub et al.

117

inter-regional migrants), with considerably

fewer pluses (indicating a statistically signif-

icant advantage). Out of 64 possible relation-

ships summarized in Table 5, only nine (14

percent) suggest an economic advantage for

inter-regional migrants. By contrast, 30 rela-

tionships (47 percent) indicate a statistically

nonsignificant association, and 25 (39 per-

cent) indicate a significant economic disad-

vantage

for

inter-regional

migrants.

Furthermore, eight of the nine statistically

significant advantages reported in this table

represent income benefits that are not

adjusted for regional differences in wages.

Overall, we find that the main difference

between the findings for blacks and whites

is the substantially greater percentage of sig-

nificantly negative relationships for whites

than for blacks—53 and 25 percent, respec-

tively. While we are unable to draw conclu-

sions directly comparing the experiences of

black and white migrants, our results indicate

that white inter-regional migrants experi-

enced a greater disadvantage compared with

white intra-regional migrants than did blacks.

Overall, our statistical findings tell a consis-

tent and powerful story of economic sacrifice

by migrants who left the South during the

Great Migration, especially for whites, rather

than a tale of economic advantage.

CONCLUSIONS

Scholars studying the Great Migration funda-

mentally assume, explicitly or implicitly, that

individuals who left the South for the North

or the West benefited economically from their

decision to relocate. Certainly, many who

migrated enjoyed substantial success in their

destinations—enough success to stay and to

provide an impetus for many of their southern

contemporaries to follow. The assumption

that migrants generally benefited economically

is not unreasonable, given the predictions and

explanations of traditional ‘‘push-pull’’ theo-

ries of migration. That is, if migrants move to

maximize

their

social

and

economic

opportunities, then we would expect their

post-migration outcomes to be more favorable

than the corresponding, ‘‘unmeasurable’’ out-

comes that they would have experienced if

they had not moved. Such an assumption is

also consistent with prior evidence that south-

ern migrants, especially African Americans,

fared quite well on a variety of social and eco-

nomic characteristics when compared with

their northern-born neighbors. Perhaps because

of the apparent validity of this assumption, little

effort has been devoted to examining it

empirically.

In this analysis, we used a comparative

approach to assess the economic standing of

inter-regional migrants from the South in rela-

tion to two groups of southerners who remained

in the region: (1) those who stayed in the South

and also migrated across a state line and (2)

those who stayed in the South but did not

migrate (at least not during the five years before

the census). The evidence is clear, and

extremely consistent, in the conclusions that it

yields. Specifically, individuals who left the

South during the Great Migration, on average,

fared no better than those who stayed behind;

in fact, based on some criteria, they may have

done worse. These somewhat surprising con-

clusions are true whether we consider black or

white migrants, short- or long-term economic

outcomes, or earlier or later stages in the

Great Migration.

17

It is also true whether we

compare the inter-regional migrants with those

who remained in the South but migrated across

state lines or, in many cases, with those who

were sedentary.

Our findings cast doubt on the widely

shared assumption that southern migrants