What is typical for call centre jobs? Job

characteristics, and service interactions in different

call centres

Dieter Zapf, Amela Isic, Myriam Bechtoldt, and Patricia Blau

J. W. Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany

Call centres have been one of the few booming branches in recent years. The

main task of call centre operators is to interact with customers by telephone,

usually supported by computer systems. It has been argued that call centre

work is a modern form of ‘‘Taylorism’’, because it is characterized by routine

tasks, and low level of control for the employees. Moreover, it has been

suggested that there is a high level of stress at work, both with regard to the

work tasks and to the interactions with customers. In the present study a

sample of 375 call centre employees from eight different call centres was

compared with a sample of noncall centre workers (N = 405) in terms of job

characteristics, job stressors, and emotional labour (emotion work). The

results showed that call centre workers had worse job characteristics, but were

better off with regard to most job stressors compared to representative

comparison groups of no-service workers, service workers, and workers in

human services respectively. Moreover, compared to the other groups,

customer service representatives (CSRs) had to express less negative emotions,

but were most frequently exposed to states of emotional dissonance. A

comparison of the working conditions of the eight call centres revealed that in

most call centres the working conditions could be substantially improved. In

addition, various call centre parameters such as inbound vs. outbound, or

inhouse vs. external service centres were examined. The strongest effects were

found for the percentage of time spent on the telephone. With some

exceptions, the results support the view that the majority of call centres have

been established to organize mass service for customers, that the work in the

#

2003 Psychology Press Ltd

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/pp/1359432X.html

DOI: 10.1080/13594320344000183

Correspondence should be addressed to D. Zapf, Department of Psychology, Johann

Wolfgang Goethe-University Frankfurt, Mertonstr. 17, D-60054 Frankfurt, Germany. Email:

D.Zapf@psych.uni-frankfurt.de

An earlier version of this article was presented as a poster at the 25th International Congress

of Applied Psychology, 7 – 12 July 2002, Singapore. The present study was supported by the

German Federal Ministry of Work and Social Affairs. Overall coordination of participating

projects: Verwaltungsberufsgenossenschaft VBG. Project organization of the present study:

Rationalisierungskuratorium der Deutschen Wirtschaft RKW, Eschborn. The support of the

project organizers is gratefully acknowledged.

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF WORK AND ORGANIZATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY,

2003, 12 (4), 311–340

call centres is characterized by routine work and low task control, and that call

centre employees are required to suggest a ‘‘friendly smile’’ when they are on

the phone.

No prospering without customers—a fact of prominent importance for

service-oriented economies worldwide. Competing for customers has

inspired companies to invent new ways of service. One of these ways is a

call centre. As the name suggests, call centres are offices assigned to

telephonic contact with customers. An official definition says: Call centres

are ‘‘tools for organising communication with customers . . . with the help of

telecommunication’’ (Henn, Kruse, & Strawe, 1996, p. 14).

Call centres may either be part of the company (‘‘inhouse’’ call centres) or

be external services (‘‘service bureaux’’) usually working on behalf of several

companies. The ways call centres get in contact with customers may differ.

Whereas inbound call centres are restricted to a passive role (i.e., being

called up exclusively by customers having any questions or complaints

concerning a product), outbound call centres actively engage in phoning

people up, e.g., telemarketing call centres. However, there are also call

centres with both inbound and outbound activities. Basically, with the help

of call centres companies aim to demonstrate their customer orientation,

and try to ensure their clients’ satisfaction and commitment. From the

companies’ point of view, the advantages are manifold: lower costs in the

area of field work because even sophisticated services may be rendered by

phone; more satisfied customers because, ideally, the call centre can be

contacted 7 days a week, 24 hours a day (Henn et al., 1996; Holman, 2003).

To do his job, the customer service representative (CSR) of a call centre

usually sits at a table in front of a computer, wearing a headset for

communicating with the customer, leaving his/her hands free in order to

input data into the computer if necessary. Depending on the business, a

CSR talks to between 60 and 250 clients per 8 hour shift (Dieckhoff,

Freigang-Bauer, Schro¨ter, & Viereck, 2002; Henn et al., 1996). The more

customers are talked to, the less time is available for each of them and the

more routine (and boring) these conversations may become for the CSR.

The high rate of turnover and absenteeism in many call centres suggests

that working in call centres is a stressful experience (e.g., Baumgart et al.,

2002; Deery, Iverson, & Walsh, 2002; Holman, 2002, 2003). Although some

studies seem to suggest that working in call centres can be interesting (Batt,

2002), there are still too few studies to give a definite answer here. Therefore,

it is interesting to analyse the profile of CSRs’ jobs from a work psychology

point of view.

Recent studies suggest that most jobs in call centres can be characterized

as unskilled work, which some authors (e.g., Knights & McCabe, 1998)

called an advanced form of Taylorism (see also Dieckhoff et al., 2002).

312

ZAPF ET AL.

Relatively short-cycle routine interactions with customers mostly controlled

by automatic call distribution systems and supported by networked

information technologies allow little control of when and whom to speak

to (e.g., Holman, 2003). Moreover, CSRs are expected to be always friendly

(as if they are ‘‘smiling’’) on the telephone (Holman, 2003; Schuler, 2000)—a

fact described in literature as imposing emotional demands on the CSRs.

Thus the main research question of this article is: Can call centres be

characterized as low skilled routine jobs with little control, high job

stressors, and high emotional demands to be customer-friendly due to

organizational rules?

Several studies (e.g., Richter & Schulze, 2001; Wieland, Metz, & Richter,

2001) showed that CSRs have low levels of job control. Isic, Dormann, and

Zapf (1999) compared the working conditions of 250 call centre employees

to those in banks and administrative offices. While call centres did not stand

out in terms of job stressors such as uncertainty, organizational problems,

and time pressure, they were distinguished by very low task control and

timing control. According to that, CSRs suffered significantly more from

psychosomatic complaints than employees in banks and administrative

offices. Gerlmaier, Bo¨cker, and Kastner (2001), and Richter and Schulze

(2001) reported similar results. Metz, Rothe, and Degener (2001) analysed

37 CSR jobs with the help of experts. The experts criticized the poor decision

latitude as well as the low complexity and high division of the work: CSRs

continuously had to repeat the same activities thereby scarcely having the

opportunity to make use of their professional know-how. Most call centre

employees working in the front office do not complete a professional

training for their telephone work (Baumgart et al., 2002; Isic et al., 1999).

Therefore, to prevent inexperienced CSRs from making mistakes, complex-

ity of work is often massively restricted. For example, with the help of

standardized computer programs, employees in call centres of banks book

orders for bonds even without any comprehensive knowledge of the matter

(cf. Holman, 2003; Holman, Chissic, & Totterdell, 2002). More complicated

enquiries are diverted to the few specialists who work in the back office

(Henn et al., 1996).

Following Bowen and Schneider (1988) and Batt (2002), Holman (2003)

differentiated between two call centre models: the ‘‘mass service’’ and the

‘‘high commitment service’’ model. The mass service model aims at a high

market volume and low added value. Cost minimization is the primary goal

here. The jobs are characterized by routine work (low complexity) and low

control. Employees are often required to follow a scripted dialogue when

interacting with customers and follow highly detailed instructions (Deery et

al., 2002). Frenkel, Tam, Korczynski, and Shire (1998) argued that despite

the rhetoric of service quality, management appears to place a greater

emphasis on the quantity of calls, thus showing preference for the mass

TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CALL CENTRE JOBS

313

service model (see also Dieckhoff et al., 2002). This contrasts the high

commitment service. In this case, the market volume is low but the added

value is high. Jobs are empowered, i.e., tasks are complex and there is high

control for the service providers. The interactions with customers

correspond to the relationship model (see below). Moreover, there are

human resource incentives such as ongoing investment in training, employ-

ment security and relatively high pay (Batt, 2002).

In this study we compare employees from several call centres with a

representative sample of employees not working in call centres. This

sample consisted of three groups: employees doing manufacturing or

administrative work (the ‘‘no-service group’’), people working in the

service sector (e.g., sales or banks), and people working in the human

services (e.g., nurses). In order to analyse typical profiles of call centre

work, we first analysed whether call centre work is specific in the way

that it differs significantly from the three groups of the representative

sample (Hypothesis 1). Based on the existing studies cited above we

expected most call centres to follow the mass service model, i.e., jobs will

be characterized by lower complexity and control (task and timing

control,

participation)

in

comparison

to

the

comparison

samples

(Hypothesis 1a). Moreover, in these types of call centres employees are

supposed to handle as many call as possible. This is assumed to lead to

high time pressure and requiring considerable attention and concentra-

tion. Therefore it was hypothesized that call centre jobs are characterized

by

higher

task-related

and

organizational

job

stressors

than

the

comparison samples (Hypothesis 1b).

So far, we have discussed organizational and task aspects of call centre

jobs focusing on cognitive aspects of internal information processing.

Another aspect is the CSRs’ social interaction with the customer. As in any

social interaction, the regulation of emotions plays a central role here.

Hochschild (1983) coined the term ‘‘emotional labour’’ for this kind of job

requirement occurring in service interactions. Emotional labour or emotion

work (Zapf, 2002) refers to the quality of interactions between employees

and clients. ‘‘Client’’ refers to any person who interacts with an employee,

for example, patients, children, customers, passengers, or guests. Expressing

appropriate emotions during face-to-face or voice-to-voice interactions is a

job demand for many employees in the service industry, particularly in call

centre jobs. Hochschild drew upon the work of Goffman (1959) to argue

that while interacting, people nearly always tend to play roles and try to

create certain impressions. Impressions include the display of normatively

appropriate emotions following certain display rules. This general social

phenomenon also applies to interactions between CSRs and their customers

or clients. Certainly, CSRs cannot be assumed to be always in a good mood.

Rather, they frequently encounter situations where anger is likely to be the

314

ZAPF ET AL.

dominant emotion (Deery et al., 2002; Grandey, Dickter, & Sin, 2002).

Emotion work as part of the job, however, implies the display of

organizationally desired emotions even in such unpleasant situations.

Accordingly, emotion work can be defined as the psychological processes

necessary to regulate organizationally desired emotions as part of one’s job

(Grandey, 2000; Zapf, 2002).

In the service sector, customer orientation is a label for such norms, rules,

and standards of behaviour in service interactions that require to regulate

emotions (Zeithaml & Bitner, 2000). In the case of a call centre where

employees interact with customers by telephone, there may be rules such as:

talking to customers should not exceed 5 minutes; customers should be

addressed by their names; or customers should be talked to in a friendly tone

throughout the interaction which means to display certain (usually positive)

emotions towards clients.

Recent studies have differentiated various dimensions of emotion work.

Most of them comprise the frequency of emotion expression and emotional

dissonance (e.g., Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Bu¨ssing & Glaser, 1999;

Grandey, 2000; Morris & Feldman, 1996; Schaubroeck & Jones, 2000). This

also applies to the concept used in the present study. Zapf, Vogt, Seifert,

Mertini, and Isic (1999) differentiated the following aspects of emotion

work: (1) the requirement to display positive emotions (abbreviated as

‘‘positive emotions’’), (2) the requirement to display and handle negative

emotions, which also implies a high variety of emotions (‘‘negative

emotions’’), (3) the requirement to sense the interaction partner’s emotions

(‘‘sensitivity requirements’’), and (4) the dissonance between felt and

displayed emotions (‘‘emotional dissonance’’).

In line with most empirical studies (e.g., Adelmann, 1995; Brotheridge &

Lee, 2003; Morris & Feldman, 1997) the frequency of emotional display is

considered to be an important aspect of emotion work. Factor analyses

(Zapf et al., 1999) demonstrated the necessity of distinguishing between

showing positive and showing negative emotions. Having to display positive

and negative emotions usually implies demonstrating a high variety of

emotions because positive emotions have to be shown in most of the jobs.

Therefore, the requirement to display negative emotions comes close to the

concept of variety of emotion display suggested by Morris and Feldman

(1996).

The expression of organizationally desired emotions is not an end in

itself. Emotions are shown to have an influence on clients (Kruml & Geddes,

2000). Expressing emotions is one possible way to influence the clients’

emotions. To be able to do so, their accurate perception is an important

prerequisite. Therefore, sensitivity requirements as the necessity to be

sensitive and to consider the clients’ emotions is another aspect of the

emotion work concept (Zapf et al., 1999).

TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CALL CENTRE JOBS

315

Finally, as most of the other studies of emotion work, we included the

concept of emotional dissonance (e.g., Brotheridge & Lee, 2003; Bu¨ssing &

Glaser, 1999; Kruml & Geddes, 2000; Morris & Feldman, 1996, 1997;

Nerdinger & Ro¨per, 1999; Zapf et al., 1999). Emotional dissonance occurs

when an employee is required to express emotions that are not genuinely felt

in the particular situation. A person may feel neutral while required to

display a particular emotion, or alternatively the display rule may require

the suppression of undesired emotions and the expression of neutrality or a

positive emotion instead of a negative one. Studies on emotional dissonance

consistently found correlations with emotional exhaustion (e.g., Morris &

Feldman, 1997; Nerdinger & Ro¨per, 1999; Schaubroeck & Jones, 2000).

Based on Gutek (1997), Holman (2003) classified customer – employee

interactions in call centres as ‘‘relationships’’ and ‘‘encounters’’. Encounters

involve single short interactions between strangers and are standardized

with little room for authentic emotional expression. Contrary to that,

persons in relationships know each other and share a common history. Trust

and loyalty are important elements of these relationships. Applying the

concept of emotion work, it can be assumed that the expression of positive

emotions (the friendly ‘‘smile’’) is the predominant requirement in the

encounter. Since encounters involve short interactions between strangers

having no shared history in common, requirements to express negative

emotions are unlikely. Of course, both interaction partners may have

negative feelings; for example, the CSR might feel impatient, the customer

dissatisfied or angry at the quality of service. However, the CSR is always

expected to react in a positive manner and to ‘‘appear happy, nice and glad

to serve the customer’’ (Erickson & Wharton, 1997, p. 188). This may lead

to a high level of emotional dissonance, which is the discrepancy between

expressed and felt emotions. Gutek (1997) argued that relationships serve as

a model for encounters because of their positive features and that

organizations try to emulate some of the qualities of relationships by

developing ‘‘pseudo-relationships’’. By showing interest and concern, CSRs

may create the impression of a trusting relationship to customize the service.

This may be supported by customer-relationship systems that track

customers’ interaction with the organization (Holman, 2003) and provide

information about the customers’ service histories and their needs. Thus

there may be relatively high requirements to be sensitive to the needs and

emotions of customers compared to what one would normally expect from

impersonal short-cycle encounters.

With regard to our study we expected that most call centres follow the

encounter model implying a high requirement to express positive emotions

(Hypothesis 1c), but a low requirement to express negative emotions

(Hypothesis 1d). Expectations for sensitivity requirements were unclear;

however, emotional dissonance was expected to be high (Hypothesis 1e).

316

ZAPF ET AL.

The reason for this is that in the encounter model the interaction is only

superficial and comprises just a few cues to elicit the expected positive

emotion. The room for authenticity is assumed to be limited in these

interactions, i.e., adequate negative emotion may hardly be expressed. Being

strictly required to show positive emotions in situations where one would

normally show negative ones leads to emotional dissonance.

Moreover, to further analyse what is typical for call centres, we were

interested in comparing the various call centres under study. Although it is

likely that most of the call centres follow the mass service model, there may

be some call centres following the customer relationship service model or

some hybrid model. Therefore, we expected diversity among the call centres

with regard to complexity and control. That is, although the majority of call

centres may be characterized by unskilled work, there may be a few call

centres with complex tasks and high control (Hypothesis 2a). Moreover, we

expected no or only minor differences among the call centres with regard to

the emotion work variables because the various call centres claimed to have

similar degrees of customer orientation and numbers of CSR – customer

interactions (Hypothesis 2b).

We were also interested in explaining the differences among the call

centres. Therefore we looked at various organizational variables that were

hypothesized to cause such differences. We compared inhouse call centres vs.

service bureaux, providing simple information vs. simple counselling vs.

complex counselling, percentage of frontline work, inbound vs. outbound

vs. both, leadership responsibilities, mean call time, and number of

customers per hour as covariates. If these covariates reduced the variance

between the call centres then the differences could be mainly attributed to

these variables.

Finally, we were interested to compare call centre jobs with regard to the

organizational call centre variables. First, we expected differences between

inhouse call centres and service bureaux. We assumed inhouse CSRs to be

better off while they could have the opportunity to combine telephone work

with other, more challenging, work. In service bureaux such work might

often be not available. Apart from that, the CSRs may have worked in other

departments of the organization and may, therefore, be familiar with a

variety of these tasks. Service bureaux usually work for different clients,

which would probably not be effective if the tasks they take over are very

complex, because that would require high training efforts. Therefore,

complexity and control should be higher in inhouse call centres compared to

service bureaux (Hypothesis 3a). Moreover, the studies of Bongard and

al’Absi (2003) suggest that emotional display rules are less rigid the more

familiar the situation is. Therefore, we expected that service bureaux were

more rigid with regard to their display rules, whereas CSRs dealing with

customers of their own company may be allowed to be somewhat more

TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CALL CENTRE JOBS

317

authentic. This usually implies that they are allowed to express negative

emotions in certain situations, e.g., if the customer shows negative

behaviours. Agents in service bureaux, in contrast, are required to express

positive emotions even in such situations. Therefore, we expected that the

requirement to express negative emotions was higher in inhouse call centres

compared to service bureaux (Hypothesis 3b). As a consequence emotional

dissonance was expected to be higher in service bureaux (Hypothesis 3c).

The nature of the tasks in the call centre is believed to affect the working

conditions of the CSRs. CSRs whose main task is to pass on simple

information and to book orders as well as to do simple counselling were

expected to have jobs of low complexity and control (Hypothesis 4a).

However, they were also expected to have less job stressors, because it is a

typical finding that high task complexity goes along with more job stressors

(e.g., Dormann, Zapf, & Isic, 2002; Zapf, 1993, Zapf et al., in press)

(Hypothesis 4b). Also as for inhouse call centres we expected less strict

display rules and more possibilities to be authentic for CSRs with complex

counselling tasks. Displaying of negative emotions was, therefore, expected

to be higher for CSRs with complex counselling tasks (Hypothesis 4c) and

emotional dissonance was expected to be lower (Hypothesis 4d).

We also compared participants with leadership responsibilities (team

leaders) vs. CSRs who had no leadership role. Team leaders were expected

to be confronted with more complex tasks and to have more control

(Hypothesis 5a). In addition, we also expected that they would be more

exposed to job stressors, since they were supposed to be in charge for all the

unusual tasks that lack clear procedures how to be handled and that are

unpredictable with respect to outcomes and time required (Hypothesis 5b).

Because team leaders were hypothesized to have more other tasks than

interacting with customers, they were supposed to be less involved in

emotion work (Hypothesis 5c).

Next, we asked for the percentage of telephone work (frontline work in

comparison to backstage work). In the study by Metz et al. (2001), working

conditions in the back office were rated more favourably because people

working there are dealing with specialist, administrative, and managerial

tasks that are much more challenging and less restricted. These employees

do not interact with customers, so they are not directly controlled by them.

Consequently they had more timing and task control and the tasks were in

average more complex. Also people in the back office are believed to have

more control because the affairs they are dealing with can hardly be

managed within a few minutes—the time employees in the front office have

available. Similar results were reported by Baumgart et al. (2002). Therefore,

we hypothesized that less telephone work should imply higher complexity

and control (Hypothesis 6a). With less interactions with customers, there

should be less emotion work, too (Hypothesis 6b).

318

ZAPF ET AL.

Finally, we also compared inbound and outbound activities. In the

inbound service customers are making the call, which means that the CSRs

are in control neither of time nor action (timing control and task control, see

Method section)—they have no choice but to accept the call. We, therefore,

expected that inbound activities would be characterized by the lowest job

control (Hypothesis 7).

METHOD

Sample

A sample of employees working in different call centres was compared

with a random sample of employees of two German cities. A variety of

call centres were contacted, e.g., both inhouse call centres and external

service bureaux, call centres with inbound and outbound activities, etc.

The majority of the call centre sample was located in Hessen (a federal

state of Germany). In total, nine call centres agreed to take part in this

study. From the 506 questionnaires that were distributed, 375 ques-

tionnaires were returned. The response rate was 71%. From one call

centre only very few questionnaires were returned; this call centre was left

out of the comparison of call centres. The data was included in other

analyses. Eight call centres, representing different types of call centres,

could therefore be compared. Participation was voluntary and anonymity

was guaranteed. Two thirds of the sample (66.8%) was women. Mean

age was 31.9 years, ranging from 18 to 59 years. There were 44.1% who

had some kind of high school degree, 37.3% who had attended modern

secondary school (middle stream school-leaving certificate), and 16.6%

having a lower stream school-leaving certificate. Only 8% were in

possession of some kind of university degree. There were 59.6% persons

reporting to have completed a professional training, while 25.4% had

not. However, more than half (50.9%) of the persons with professional

training had no specific training concerning working in call centres.

Instead, they had changed their vocation and started working as CSRs

without special experience. On average, persons had more than 5 years

but no longer than 10 years work experience, but they had not been

employed for longer than 6 – 12 months by their current call centre at the

time of study.

The jobs of the call centre employees consisted of providing information

on the phone (33.2%) or simple counselling (46%); 19.5% were specialists

responsible for complex counselling. Eighty-five per cent of the persons

worked as CSRs without leadership responsibilities, 10.5% were head of a

team. Sixty-six per cent of the sample worked in service bureaux, the rest in

inhouse call centres. More than half (54.8%) of the persons did inbound

TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CALL CENTRE JOBS

319

calls only, 12.3% outbound calls only, and 32.6% were engaged in both.

Call centre 1 was a telemarketing call centre with outbound activities only.

In Call centres 4 and 6, only inbound activities were carried out, whereas all

the other call centres combined both inbound and outbound activities. Call

centres 2, 5, and 6 were inhouse call centres; the others were external service

bureaux. On average the participants reported a single call to last between 3

and 5 minutes (range: 1 to more than 15 minutes). Per hour, they talked to

6 – 10 clients, ranging from 1 to more than 20.

The comparison sample was a random sample of persons from two large

German cities who worked for at least 30 hours a week, who were not self-

employed, and whose German was reasonably good so that they were able

to fill in the questionnaire. Participants were randomly chosen from a citizen

database. They received a letter inviting them to participate. After some

days the potential participants were contacted by telephone. Many people

were excluded because they did not fulfil the criteria mentioned above. We

contacted 767 persons who met the criteria for participation, and 405

persons returned the questionnaire (anonymously), which corresponds to a

response rate of 52.8%. This estimation is the lower bound of the response

rate, because among the 767 persons contacted some refused to take part in

the study and finished the telephone call before the researchers received all

information to decide whether the person would have fulfilled all criteria to

participate.

The mean age of the control sample was 40.9 years, ranging from 19 to 73

years; 37.8% were women. There were 55.9% who had some kind of high

school degree, 23% who had attended modern secondary school, and 19.8%

had a lower stream school-leaving certificate. Few (1.8%) had no certificate

at all, and 35.6% had some kind of university degree. Seventy-nine per cent

of the persons reported to have completed a professional training relevant

for their current job. On average (median category), persons had worked for

15 – 20 years, of which 2 – 5 years were in their current job.

For some of the analyses the comparison sample was divided into

subsamples: service employees not working in the service sector (N = 217,

e.g., manufacturing, repair, administrative work), employees working in the

service sector (N = 131, e.g., sales, banks, insurance, transportation, hotels

and restaurants), and human service workers (N = 52, e.g., nurses,

physicians, teachers, social workers).

Instruments

The items used in the present study were part of a more wide-ranging

questionnaire. Time to fill in the whole questionnaire took from 45 to 90

minutes. The Instrument of Stress Oriented Job-Analysis (ISTA 6.0;

Semmer, Zapf, & Dunckel, 1995, 1998, 1999) was used to examine

320

ZAPF ET AL.

differences concerning complexity, control, and job stressors. All ISTA

scales, except the one measuring ‘‘participation’’, consisted of five items and

used various response formats ranging from 1 to 5, with 1 = ‘‘very seldom/

never’’ to 5 = ‘‘very often’’. Some items required a response on a 5-point

scale that ranged from 1 = ‘‘very few’’ to 5 = ‘‘very much’’. For some items

we used the ‘‘A vs. B’’-format (e.g., ‘‘‘A’ has documents and information

that are always correct and up to date—‘B’ has documents and information

that are often incomplete and out of date. What is your job like?’’). Items

using the ‘‘A vs. B’’ format required a response on a 5-point scale from

1 = ‘‘exactly like ‘A’’’ to 5 = ‘‘exactly like ‘B’’’. The aspects considered were

as follows.

Complexity

.

This assessed the complexity of decisions and planning

processes required to fulfil the task, how often difficult tasks have to be

accomplished, and if the job offers the chance for enlarging one’s

professional know-how. An example item is: ‘‘Colleague A has to plan in

detail how the task can be solved. Colleague B’s tasks do not require any

planning processes. Which job is more similar to yours?’’

Task control

.

This referred to the number and kind of decision

possibilities concerning the tasks (e.g., ‘‘Is it possible in your job to make

one’s own decisions how to carry out the tasks?’’).

Timing control

.

This referred to decision possibilities with regard to time

aspects of the task, for example, if the person is allowed to choose his or her

own pace and take a break when feeling for it (e.g., ‘‘To what extent can you

decide how long to work on a certain task?’’).

Participation

.

This referred to more general decision possibilities with

regard to planning vacations or shifts, employing new staff, or composition

of the team. The scale consisted of seven items and asked to what extent the

person may take part in these decisions.

Organizational problems

.

This asked about problems in the work

organization that typically cause additional effort to perform the tasks

(e.g., ‘‘‘A’ has to use tricks to be able to fulfil his/her work. ‘B’ is equipped in

such a way that he/she can manage without additional effort. Which job is

similar to yours?’’). This scale bears resemblance to the constraints scale of

Spector and Jex (1998).

Uncertainty

.

This aimed at unclear or contradictory goals, conditions,

or outcomes of actions and included contradictory or unclear external tasks

of the organization (e.g., ‘‘How often do you get contradictory orders?’’).

TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CALL CENTRE JOBS

321

Time pressure

.

This described quantitative aspects of the job and

referred to problems caused by speed and quantity of information

processing so that tasks cannot be executed within a given time frame

(e.g., ‘‘How often do you have to work during your break because there is so

much work?’’).

Concentration demands

.

This referred to the problem of informational

overload of the working memory during action execution. In this case, too

much concurrent information is required to be available in the working

memory to accomplish the task (e.g., ‘‘Do you have to make mental notes of

things that are difficult to remember (number of units, names, addresses,

codes, file names, folders, etc.)?’’).

Cooperation demands

.

The necessity of cooperating with other persons

to accomplish one’s tasks may cause stress if these persons cannot be relied

on. This is why proximity of cooperation was considered to be a potential

job stressor. The scale asked if one’s process of work is hindered by

colleagues or team members.

Emotion work or emotional labour

.

This was measured using the

Frankfurt Emotion Work Scales (FEWS 4.0; Zapf, Mertini, Seifert, Vogt,

Isic, & Fischbach, 2000; Zapf et al., 1999). Response formats corresponded

to those of the ISTA instrument.

Positive emotions

.

This scale referred to the requirement to display

pleasant emotions (e.g., ‘‘In your job how often does it occur that you have

to display pleasant emotions towards your clients?’’).

Negative emotions

.

This asked for the necessity of displaying and

dealing with unpleasant emotions (e.g., ‘‘How often does it occur in your job

that you have to display unpleasant emotions towards your clients?’’).

Sensitivity requirements

.

This examined whether empathy or knowledge

about clients’ current feelings are required by the job (e.g., ‘‘Does your job

require paying attention to the feelings of your clients?’’).

Emotional dissonance

.

This referred to the display of unfelt emotions

and to the suppression of felt but (from an organizational perspective)

undesired emotions (e.g., ‘‘How often does it occur in your job that one has

to display positive emotions that do not correspond to what you feel in this

situation?’’)

Moreover, we used single items to measure characteristics of the call

centres. We asked whether the participants worked in inhouse call centres or

322

ZAPF ET AL.

in service bureaux, whether they worked inbound, outbound, or both,

whether their main task was to give information or to do simple order

bookings, simple counselling, or complex counselling, whether they had

managerial responsibility, and the percentage of time spent at the telephone.

Means and standard deviations of the above-mentioned scales are presented

in Table 1; the intercorrelations are presented in Table 2.

RESULTS

First, we analysed whether the overall call centre sample significantly

differed from the three groups of the comparison sample. Corresponding

analyses are presented in Table 3. The call centre sample was characterized

by significantly less complexity, task control, timing control, and participa-

tion than all other groups. This result was in line with previous studies and

supported Hypothesis 1a. As far as job stressors are concerned, no

differences were found for ‘‘uncertainty’’. For all other job stressors, the

call centres scored better, although there was no significant difference with

the human services group regarding the ‘‘cooperation demands’’. Thus,

Hypothesis 1b that job stressors would be higher in call centres compared to

other organizations was rejected. Third, we investigated the emotion work

variables. Again, substantial differences occurred across groups. With

regard to the requirement to express positive emotions, all groups differed

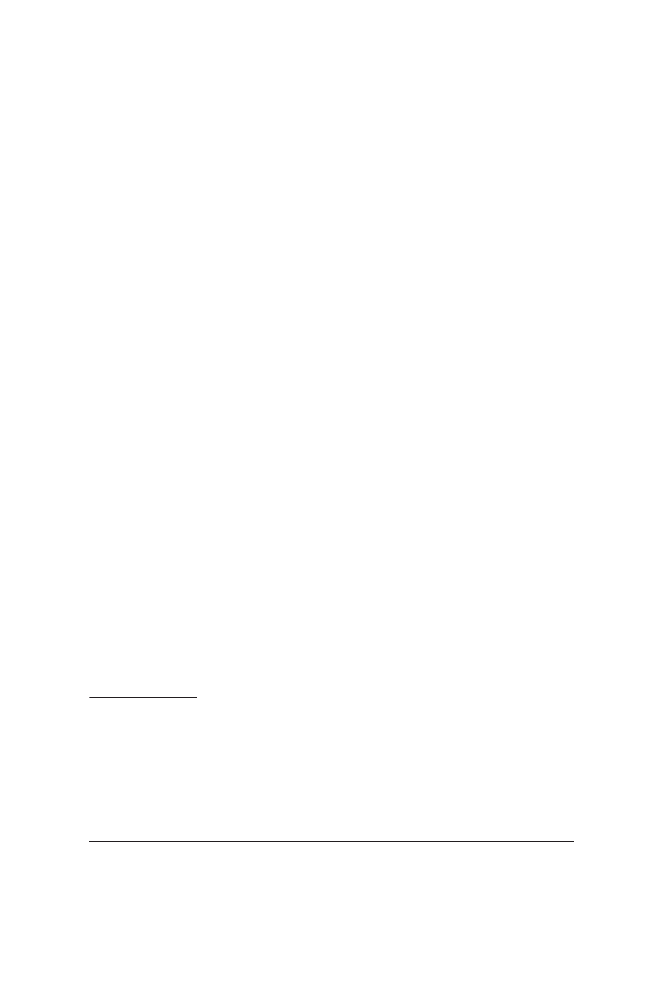

TABLE 1

Psychometric data of study variables

No. of

Call centres

Comparison groups

items

Range

Mean

SD

Coeff.

a

M

SD

Coeff.

a

Age

1

18 – 73

31.91

10.40

—

40.86

11.21

—

Gender

1

1 – 2

1.33

0.47

—

1.62

0.49

—

Complexity

5

1 – 5

2.92

0.79

.71

3.67

0.77

.77

Task control

5

1 – 5

2.75

0.93

.78

3.68

0.76

.78

Timing control

5

1 – 5

2.75

0.89

.80

3.53

0.96

.81

Participation

7

1 – 5

2.51

0.74

.75

3.37

1.02

.82

Organizational problems

5

1 – 5

2.20

0.67

.72

2.48

0.75

.76

Uncertainty

5

1 – 5

2.27

0.68

.65

2.34

0.76

.71

Time pressure

5

1 – 5

2.69

0.89

.79

3.14

0.89

.84

Concentration demands

5

1 – 5

2.84

0.85

.70

3.21

0.82

.74

Cooperation demands

5

1 – 5

2.57

1.00

.84

2.97

0.99

.86

Positive emotions

3

1 – 5

3.34

0.77

.61

2.58

1.08

.79

Negative emotions

4

1 – 5

1.70

0.55

.65

2.42

0.89

.75

Sensitivity requirements

3

1 – 5

3.37

1.10

.87

2.73

1.29

.73

Emotional dissonance

5

1 – 5

3.42

0.86

.79

2.77

0.93

.85

Gender: female = 1, male = 2.

TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CALL CENTRE JOBS

323

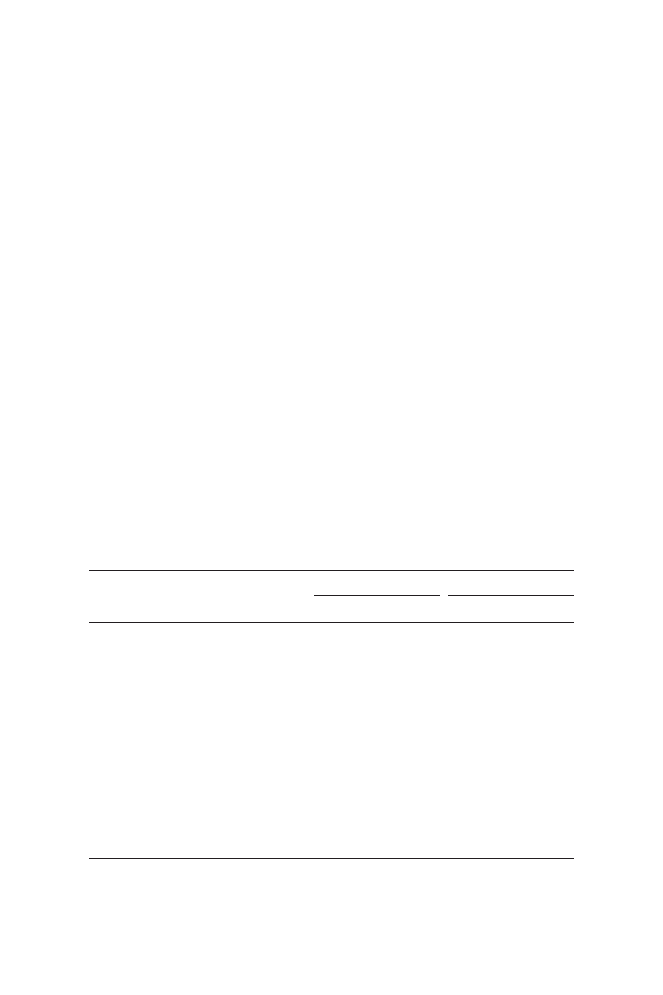

TABLE 2

Intercorrelation of study variables

Age

Gender

Comp

Task C

Partic

Tim C

Org P

Uncert

Concen

Time P

Coop

Pos E

Neg E

Sens R

Em Dis

Age

—

.03

.06

.23**

.16**

.01

7.11*

7.25**

.06

.08

7.13**

.08

.03

.07

7.06

Gender

.07

—

.04

.06

.05

.06

.03

.10*

7.01

7.06

.11*

7.16**

.05

7.14** 7.11

Complexity

.09

.18**

(.78)

.41**

.40**

.25**

.12*

.16**

.42**

.46**

.28**

.21**

.22**

.27**

.12*

Task control

7.09

.06

.45**

(.85)

.55**

.54**

7.16** 7.26**

.13**

.14**

.03

.13**

.15**

.14**

7.02

Participation

7.12*

.14**

.27**

.49**

(.83)

.58**

7.14** 7.18**

.15**

.16**

.17**

.05

.07

.10

7.03

Timing control

7.05

.01

.32**

.59**

.50**

(.83)

7.19** 7.17** 7.11*

7.18**

.02

7.16** 7.07

.00

7.24**

Organizational problems

.01

.12*

.06

7.11*

7.10

7.11

(.75)

.50**

.30**

.28**

.25**

.15**

.14**

.17**

.18**

Uncertainty

7.07

.13*

.10

7.03

7.01

7.03

.41**

(.67)

.32**

.32**

.36**

.14**

.14**

.16**

.25**

Concentration demands

.12

.17**

.40**

.13*

.09

.12

.22**

.28**

(.73)

.57**

.29**

.36**

.34**

.38**

.34**

Time pressure

.15**

.17**

.40**

.05

.11*

.01

.25**

.23**

.52**

(.80)

.32**

.39**

.30**

.41**

.40**

Cooperation demands

.01

.01

.34**

.16**

.20**

.17**

.16**

.20**

.39**

.47**

(.86)

.13**

.20**

.19**

.17**

Positive emotions

7.04

7.11*

.07

7.03

7.15** 7.10*

7.04

.02

.09

.15**

.01

(.77)

.55**

.60**

.55**

Negative emotions

7.11*

.10

.25**

.14**

7.01

.09

7.01

.04

.18**

.20**

.18**

.13*

(.72)

.45**

.41**

Sensitivity requirements

.00

.06

.18**

.06

.02

.08

.04

.12*

.23**

.27**

.18**

.49**

.19**

(.79)

.47**

Emotional dissonance

7.09

.05

.04

7.12

7.07

7.14**

.14**

.26**

.23**

.30**

.19**

.28**

.02

.46**

(.85)

Cronbach’s

a (total sample) = diagnonal (in parentheses); call centres (n = 375) = lower triangle; control groups (n = 405) = upper triangle;

*p

5 .05; **p 5 .01. Gender: female = 1, male = 2.

324

significantly from each other. They were lowest for the ‘‘no-service’’ group

followed by the service, call centre, and human service groups, thus partly

supporting Hypothesis 1c. The same result was found for sensitivity

requirements. In line with Hypothesis 1d, the call centre group was

significantly less required to express negative emotions than all other groups.

Finally, the ‘‘no-service’’ group experienced the least emotional dissonance,

whereas the call centre sample reported the highest emotional dissonance.

Although the call centre scores were not statistically different from the

human service group, this finding is in line with Hypothesis 1e.

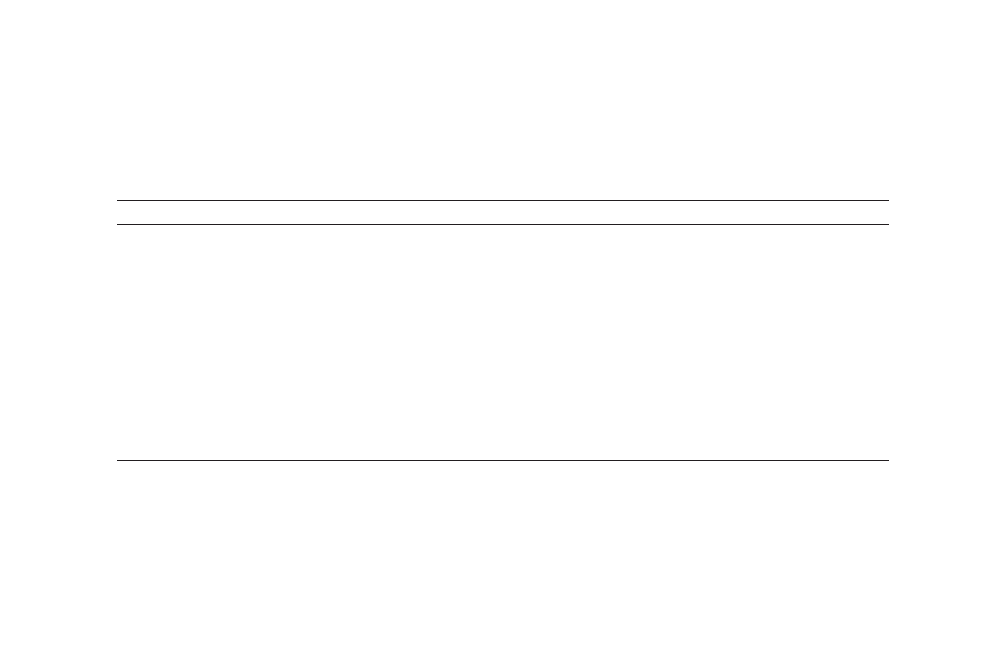

Next, we compared the eight call centre samples with the comparison

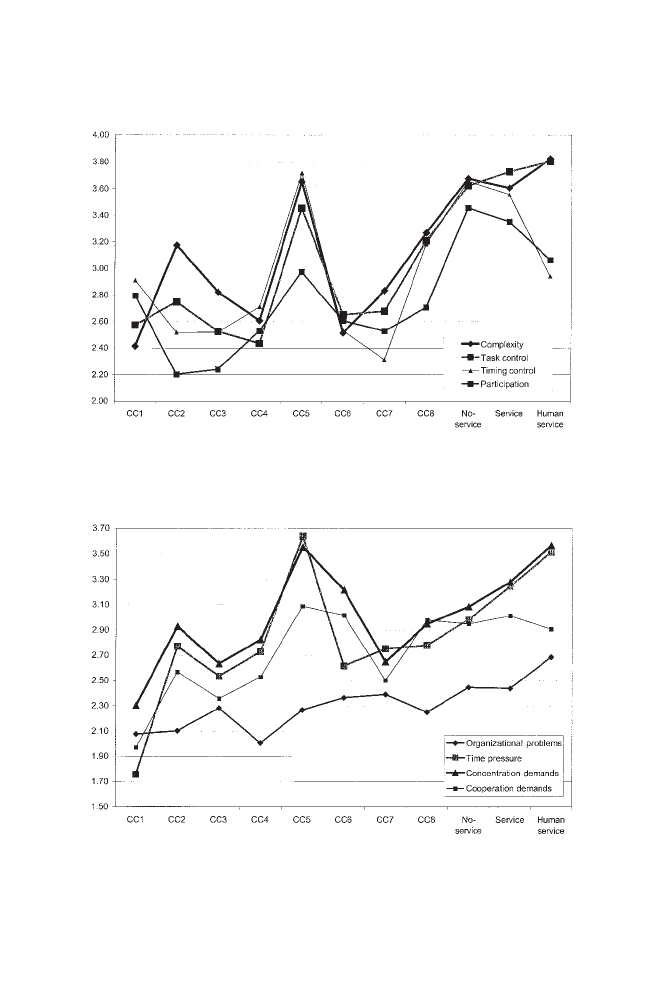

samples (Figures 1 – 3). Differences were tested with analyses of variance

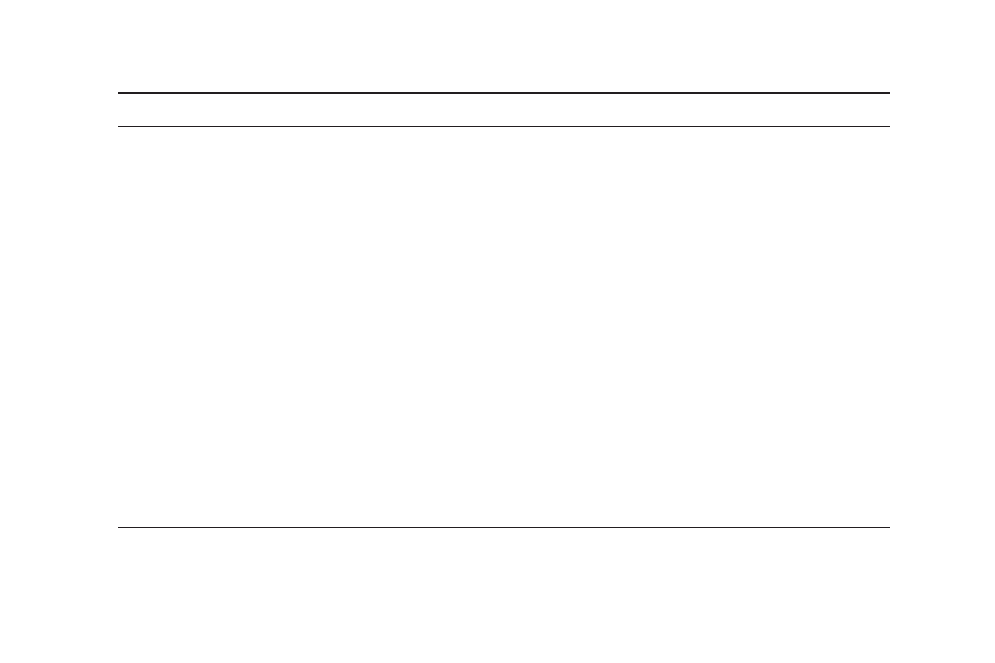

(with post hoc Bonferroni tests; see Table 4). As can be seen in Figure 1,

complexity and control were generally lower for call centres than for the

comparison groups. However, there were exceptions. Call centre 5, a

computer hotline for technical assistance, was comparable to the compar-

ison groups except for participation. In all, 11 of 28 possible mean

differences among the call centres were significant for complexity, 9 for task

control, 8 for timing control, and 2 for participation (cf. Table 4). Thus

Hypothesis 2a was partly supported.

With regard to job stressors, no significant differences were found for

‘‘uncertainty’’ (therefore not displayed in Figure 2). Two call centres differed

from the human service group with regard to organizational problems, but

not from the service group (Table 4 and Figure 2). Moreover, the eight call

TABLE 3

Comparison of the total call centre sample with comparison groups

Call

centres

No-service

group

Service

group

Human

service group

F

(df = 3)

Complexity

2, 92

a

3, 68

b

3, 61

b

3, 82

b

61, 09**

Task control

2, 74

a

3, 62

b

3, 73

b

3, 80

b

79, 16**

Timing control

2, 75

a

3, 66

b

3, 56

b

2, 94

a

55, 10**

Participation

2, 51

a

3, 46

c

3, 35

b,c

3, 06

b

61, 92**

Organizational problems

2, 20

a

2, 45

b

2, 44

b

2, 69

b

11, 53**

Uncertainty

2, 27

a

2, 32

a

2, 42

a

2, 23

a

1, 62

n.s.

Time pressure

2, 69

a

2, 99

b

3, 25

c

3, 52

c

23, 22**

Concentration demands

2, 84

a

3, 09

b

3, 28

b,c

3, 57

c

18, 54**

Cooperation demands

2, 57

a

2, 95

b

3, 02

b

2, 91

a,b

10, 32**

Positive emotions

3, 34

c

2, 16

a

2, 84

b

3, 71

d

102, 07**

Negative emotions

1, 70

a

2, 23

b

2, 37

b

3, 34

c

104, 35**

Sensitivity requirements

3, 37

c

2, 28

a

2, 88

b

4, 20

d

63, 56**

Emotional dissonance

3, 42

c

2, 45

a

3, 11

b

3, 26

c

59, 04**

**p

5 .01; n.s.: not significant; variance analyses with Bonferroni post hoc analyses; groups

with different letters are significantly different (p

5 .05).

TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CALL CENTRE JOBS

325

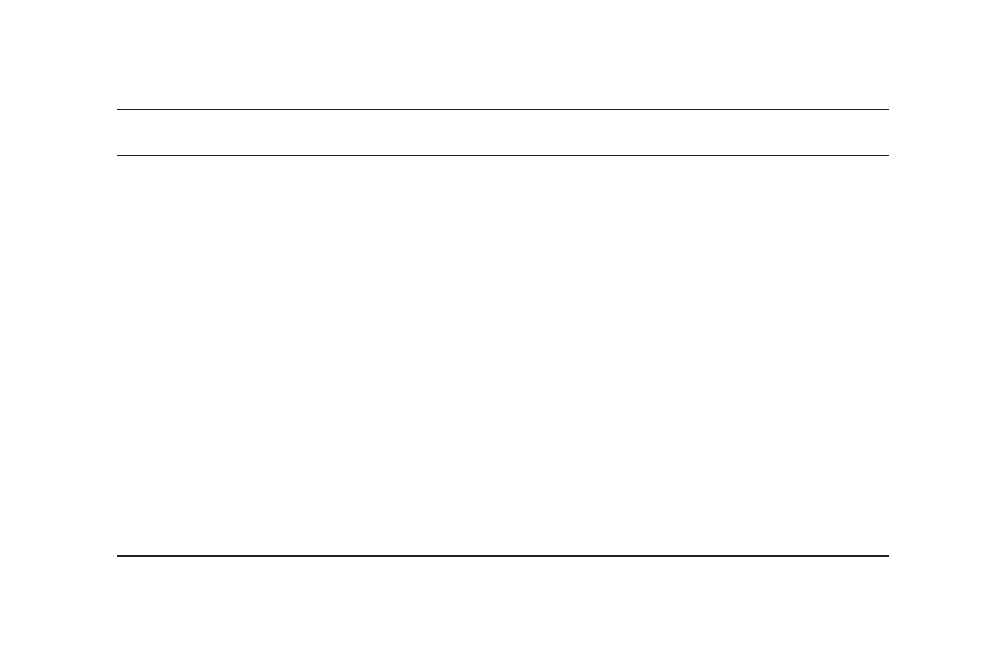

Figure 2.

Comparison of means of eight call centres and comparison groups of job stressors.

Figure 1.

Comparison of means of eight call centres and comparison groups of job

characteristics.

326

ZAPF ET AL.

centres were not significantly different from each other. In contrast, time

pressure was significantly lower in Call centre 1 (the only outbound call

centre) than in the other call centres and significantly higher in Call centre 5

than in the other call centres. In half of the call centres time pressure was

lower than in the service and human service group. Similar but less

pronounced results were found for concentration and cooperation demands.

In all, there were no significant differences among call centres for

uncertainty and organizational problems, but 12 significant differences for

time pressure, 7 for concentration demands and 5 for cooperation demands

(see Table 4: Group means with different letters are significantly different).

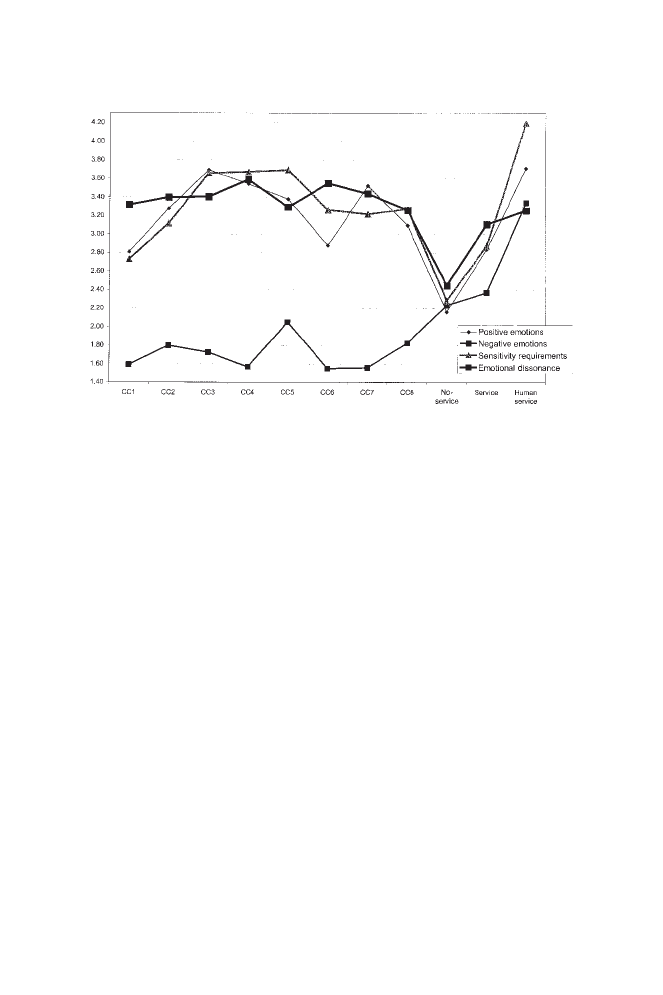

With regard to the emotion work variables (Figure 3) differences

occurred for the requirements to express positive emotions which might

be attributed to varying degrees of customer contacts. Similar results were

found for sensitivity requirements. In contrast, all call centres were

characterized by lower requirements to express negative emotions, whereas

they featured a higher level of emotional dissonance at the same time—

although not statistically different from the service and human service

group. Among the call centres, there were five significant differences for the

expression of positive emotions, and two for sensitivity requirements. No

significant differences were found for the expression of negative emotions

and emotional dissonance. Thus there was support for Hypothesis 2b only

with regard to negative emotions and emotional dissonance.

Figure 3.

Comparison of means of eight call centres and comparison groups of emotion work

variables.

TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CALL CENTRE JOBS

327

TABLE 4

Comparison of eight call centres with comparison groups

Call

centre

1

(

N = 32)

Call

centre

2

(

N = 59)

Call

centre

3

(

N = 75)

Call

centre

4

(

N = 57)

Call

centre

5

(

N = 27)

Call

centre

6

(

N = 23)

Call

centre

7

(

N = 43)

Call

centre

8

(

N = 44)

No

service

group

(

N = 217)

Service

group

(

N = 131)

Human

service

group

(

N = 52)

F

(df = 10)

Complexity

2, 42

a

3, 18

a,b

2, 82

a

2, 61

a

3, 65

c,d

2, 51

a

2, 83

a

3, 27

b

3, 68

c,d

3, 61

c,d

3, 82

d

27, 86**

Task control

2, 58

a

2, 75

a,b

2, 53

a

2, 44

a

3, 45

c,d

2, 65

a,b

2, 68

a,b

3, 21

b,c

3, 62

c,d

3, 73

d

3, 80

d

30, 84**

Timing control

2, 91

b

2, 52

a,b

2, 52

a,b

2, 71

b

3, 71

c,d

2, 53

a,b

2, 31

a

3, 18

b,c

3, 66

c,d

3, 56

c,d

2, 94

b

22, 21**

Participation

2, 80

a,b,c

2, 20

a

2, 24

a

2, 53

a,b

2, 97

b,c,d

2, 61

a,b

2, 53

a,b

2, 71

b

3, 46

d

3, 35

c,d

3, 06

b,c,d

25, 22**

Organizational

problems

2, 08

a,b

2, 10

a,b

2, 28

a,b,c

2, 08

a,b,c

2, 27

a,b,c

2, 37

a,b,c

2, 39

a,b,c

2, 25

a,b,c

2, 45

b,c

2, 44

b,c

2, 69

c

2, 73**

Uncertainty

2, 54

a

2, 08

a

2, 46

a

2, 01

a

2, 36

a

2, 48

a

2, 18

a

2, 15

a

2, 32

a

2, 42

a

2, 23

a

4, 51**

Time pressure

1, 76

a

2, 77

b,c

2, 54

b

2, 73

b

3, 64

e

2, 62

c,d

2, 76

c,d

2, 78

c,d

2, 99

c,d

3, 25

d,e

3, 52

e

10, 53**

Concentration demands

2, 30

a

2, 93

a,b,c

2, 63

a

2, 83

a,b

3, 56

b,c,d

3, 22

b,c,d

2, 65

b,c

2, 95

b,c

3, 09

b,c

3, 28

c,d

3, 57

d

15, 56**

Cooperation demands

1, 97

a

2, 57

a,b,c

2, 36

a,b

2, 53

a,b,c

3, 09

c

3, 02

b,c

2, 50

c

2, 98

c

2, 95

c

3, 02

c

2, 91

b,c

6, 77**

Positive emotions

2, 81

b

3, 28

c

3, 69

c

3, 54

c

3, 38

b,c

2, 88

b

3, 52

b

3, 10

b

2, 16

a

2, 84

b

3, 71

c

37, 06**

Negative emotions

1, 59

a

1, 80

a

1, 72

a

1, 57

a

2, 05

a,b

1, 55

a

1, 56

a

1, 82

a

2, 23

b

2, 37

b

3, 34

c

32, 35**

Sensitivity requirements

2, 73

b

3, 12

b

3, 66

b

3, 67

c

3, 69

c

3, 26

c

3, 22

b

3, 27

b

2, 28

a

2, 97

b

4, 19

c

22, 36**

Emotional dissonance

3, 32

b,c

3, 40

b,c

3, 41

b,c

3, 59

c

3, 29

b,c

3, 55

b,c

3, 44

b,c

3, 26

b,c

2, 45

a

3, 11

b

3, 26

b,c

17, 93**

**p

5 .01; variance analyses with Bonferroni post hoc analyses; groups with different letters are significantly different (p 5 .05).

328

Next we were interested in how far some of the organizational call centre

variables were able to explain the differences described in Figures 1 – 3. In

Table 5, results of covariance analyses with call centres as the independent

variable, stressors, resources, and emotion work as the dependent variables

and the organizational call centre variables as covariates are shown.

Z

2

refers

to the variance between call centres and

DZ

2

refers to the variance between

call centres after controlling for the organizational call centre variables

inhouse vs. external services, percentage of telephone work, leadership

responsibilities, task type, inbound vs. outbound, call time, and number of

customers per hour. As can be seen from Table 5, the variance between call

centres was significantly reduced for complexity and control, most

substantially for task control. Similar results were found for time pressure,

concentration, and cooperation demands, whereas the stressors uncertainty

and organizational problems were not or only little affected. The covariates

reduced the variance between call centres by 50% for positive emotions, but

had little effect on the other variables. In all cases, the percentage of

telephone time was the most influential variable.

Complexity and task control were higher in inhouse call centres, thus

partly supporting Hypothesis 3a (Table 6). No differences were found for

timing control and participation. Time pressure, concentration demands,

and cooperation demands were also higher in inhouse call centres.

Moreover, in line with Hypothesis 3b, CSRs in external service bureaux

were more frequently required to show positive emotions and less frequently

to show negative emotions. However, no differences were found for

sensitivity requirements and emotional dissonance, thus partly rejecting

Hypothesis 3b.

Not surprisingly, CSRs reporting to do complex counselling also reported

higher complexity and control (Hypothesis 4a) as well as job stressors except

uncertainty (Hypothesis 4b). Positive emotions and sensitivity requirements

were highest and negative emotions were lowest for simple counselling

(Hypothesis 4c), whereas no differences occurred for emotional dissonance.

Thus, Hypothesis 4d was rejected.

Also in line with expectations, team leaders reported higher complexity

and control (Hypothesis 5a) as well as time pressure, concentration

demands, and cooperation demands (Hypothesis 5b). No differences were

detected for the other stressors and emotion work (Hypothesis 5c). Thus

Hypothesis 5a was fully supported, Hypothesis 5b was partly supported,

whereas Hypothesis 5c was rejected. The effects for task and timing control,

however, disappeared when controlling for the other organizational call

centre variables, primarily due to the percentage of telephone time (Table 6).

Thus, the data suggest that team leaders have more task control and timing

control which might be explained by the fact that they spend less time

interacting with customers on the phone.

TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CALL CENTRE JOBS

329

TABLE 5

Job stressors and resources and characteristics of call centres

Z

2

DZ

2

Inhouse/

external

Inbound

Outbound

Information

Simple

counselling

Leader

% Time at

phone

Call time

Customer/

hour

R

2

Complexity

18.9 **

5.0 **

7.16 **

.00

7.15 **

7.22 **

7.25 **

.26 **

7.15 *

.17 **

7.08

33.9 **

(

7.18 **)

(.00)

(

7.20 **)

(

7.06)

(

7.21 **)

(.39 **)

(

7.44 *)

(.22**)

(

7.16**)

Task control

11.1 **

2.5

7.08

7.08

7.07

7.12

7.14

.06

7.31 **

.08

7.01

19.6 **

(

7.11 *)

(

7.09 *)

(

7.10 *)

(

7.07)

(

7.13 **)

(.26 **)

(

7.40**)

(.13**)

(

7.15**)

Timing control

18.3 **

6.1 **

7.06

7.13 *

7.09

7.07

7.10

7.03

7.46 **

.09

7.02

29.4 **

(

7.08)

(

7.14 *)

(

7.09 *)

(

7.09)

(

7.12 *)

(.27 **)

(

7.51**)

(.17**)

(

7.22**)

Participation

11.3 **

8.0 **

.04

7.02

7.04

7.22 **

7.20 **

.20 **

7.27 **

7.08

7.03

26.9 **

(

7.01)

(

7.05)

(

7.08)

(

7.14 *)

(

7.08)

(.40 **)

(

7.46**)

(.01)

(

7.18**)

Organizational problems

3.8

a

5.2 **

.03

7.05

7.04

7.19 *

7.15

7.03

7.03

.08

.13

3.8

n.s.

(.02)

(

7.06)

(

7.02)

(

7.08)

(

7.03)

(

7.01)

(

7.02)

(.10 *)

(.03)

Uncertainty

6.7 **

7.4 **

7.05

.03

.00

7.02

.12

7.04

7.13

.18 **

.12

4.8

n.s.

(

7.02)

(

7.02)

(.01)

(

7.07)

(.07)

(.06)

(

7.08)

(.15 **)

(.03)

Time pressure

19.6 **

8.7 **

7.04

7.02

7.14 *

7.13

7.13

.16 *

7.10

.11 *

.09

12.2 **

(

7.10)

(.03)

(

7.16 **)

(

7.02)

(

7.13 **)

(.24 **)

(

7.23**)

(.11 *)

(.01)

Concentration demands 11.9 ** 3.9

7.10

.01

7.22 **

7.10

7.14 *

.07

7.13 *

.14 *

.12

15.5 **

(

7.17 **)

(.11 *)

(

7.28 **)

(.08)

(

7.22 **)

(.14 **)

(

7.17**)

(.10 *)

(.09 *)

Cooperation demands

9.7 **

3.0

.02

.11

7.10

7.21 **

7.22 **

.14 *

7.18 *

.04

.13 *

16.7 **

(

7.09 *)

(.15 **)

(

7.22 *)

(.01)

(

7.18 **)

(.26 **)

(

7.28**)

(.03)

(.04)

Positive emotions

14.7 **

7.4 **

.14 *

.00

.08

7.02

.10

.08

.15 *

.07

.07

9.0 **

(.19 **)

(

7.07)

(.16 **)

(

7.13 **)

(.19 **)

(

7.02)

(.15**)

(.08)

(.03)

Negative emotions

6.8 **

3.6 *

7.10

.02

7.08

7.04

7.11

7.03

7.10

.13 *

7.06

7.1 **

(

7.11 *)

(.02)

(

7.12 *)

(

7.04)

(

7.15 **)

(.05)

(

7.15**)

(.14 **)

(

7.08)

Sensitivity requirements

7.4 **

5.2 **

.05

.02

7.03

7.04

.09

.09

.00

.04

.06

2.7

n.s.

(.07)

(

7.01)

(.01)

(

7.10 *)

(.12 *)

(.09)

(

7.03)

(.04)

(.01)

Emotional dissonance

1.5

1.1

.05

.08

7.05

7.11

.04

.03

.00

.05

.18 **

4.3

n.s.

(.02)

(.08)

(

7.06)

(

7.06)

(.07)

(.03)

(.03)

(.01)

(.13 **)

**p

5 .01; *p 5 .05;

a

p

= .06.

Z

2

: variance between call centres;

DZ

2

: variance between call centres after controlling for organizational call centre

variables; columns 3 – 11, line 1: results of multiple regressions: betas with stressors and resources as dependent variables; line 2, numbers in parentheses:

zero order correlations; column 12: explained variance; columns 4 – 8: dummy coded variables (cf. Table 6).

330

TABLE 6

Job stressors and resources and characteristics of call centres: Comparison of means

Inhouse

(

N = 127)

External

service

(

N = 247)

T-value

Inbound

(

N = 205)

Outbound

(

N = 45)

Both

(

N = 122)

F

(df = 2)

Information

(

N = 124)

Simple

counselling

(

N = 171)

Complex

counselling

(

N = 72)

F

(df = 2)

CSRs

(

N = 318)

Team

leader

(

N = 44)

T-value

Complexity

3.15

2.80

4.23 **

2.95

b

2.57

a

2.99

b

5.11 **

2.83

a

2.76

a

3.42

b

20.42 **

2.70

3.74

7 8.02 **

(.81)

(.76)

(.76)

(.95)

(.76)

(.76)

(.78)

(.69)

(.74)

(.70)

Task control

2.88

2.68

2.06 *

2.66

a

2.53

a

2.96

b

5.55 **

2.63

a

2.62

a

3.21

b

12.58 **

2.64

3.39

7 5.26 **

(1.01)

(.88)

(.96)

(.96)

(.82)

(.93)

(.86)

(.96)

(.89)

(.93)

Timing control

2.82

2.80

1.07

2.63

a

2.52

a

3.04

b

10.52 **

2.64

a

2.64

a

3.19

b

11.48 **

2.66

3.39

7 5.28 **

(.91)

(.88)

(.89)

(.91)

(.80)

(.80)

(.84)

(1.03)

(.84)

(.96)

Participation

2.48

2.53

7 0.59

2.45

a

2.34

a

2.68

b

5.33 **

2.37

a

2.46

a

2.87

b

11.96 **

2.40

3.26

7 5.29 **

c

(.82)

(.69)

(.73)

(.81)

(.69)

(.65)

(.73)

(.80)

(.62)

(1.05)

Organizational

2.19

2.21

7 0.22

2.18

2.18

2.25

0.45

2.11

a

2.19

2.38

b

3.68 *

2.20

2.22

7.20

problems

(.68)

(.66)

(.69)

(.76)

(.58)

(.65)

(.73)

(.80)

(.67)

(.63)

Uncertainty

2.27

2.27

0.02

2.23

2.27

2.35

1.22

2.20

2.33

2.27

1.36

2.25

2.37

7 1.08

(.72)

(.66)

(.67)

(.67)

(.71)

(.72)

(.69)

(.60)

(.69)

(.63)

Time pressure

2.89

2.58

3.20 **

2.77

b

2.40

a

2.65

3.53 *

2.64

a

2.58

a

3.04

b

7.39 **

2.61

3.28

7 4.91 **

(.89)

(.87)

(.82)

(.81)

(.99)

(.89)

(.85)

(.90)

(.86)

(.84)

Concentration

3.08

2.71

4.05 **

2.94

b

2.28

a

2.88

b

11.93 **

2.93

b

2.65

a

3.11

b

9.05 **

2.80

3.14

7 2.48 *

demands

(.80)

(.85)

(.82)

(.78)

(.86)

(.89)

(.84)

(.70)

(.87)

(.66)

Cooperation

2.74

2.49

2.28 *

2.73

b

2.06

a

2.50

b

9.15 **

2.54

a

2.37

a

3.09

b

14.46 **

2.47

3.28

7 5.12 **

demands

(1.05)

(.96)

(.98)

(.90)

(1.01)

(.96)

(.97)

(.98)

(.99)

(.84)

Positive

3.21

3.40

2.35 *

3.34

a

3.66

b

3.20

a

6.12 **

3.17

a

3.49

b

3.24

7.10 **

3.35

3.32

.39

c

emotions

(.69)

(.80)

(.76)

(.72)

(.76)

(.75)

(.80)

(.67)

(.80)

(.44)

Negative

1.79

1.66

2.24 *

1.73

1.53

1.73

2.67

1.71

1.63

a

1.89

b

5.91 *

1.70

1.76

7.74

emotions

(.58)

(.53)

(.56)

(.50)

(.53)

(.56)

(.51)

(.58)

(.55)

(.56)

Sensitivity

3.25

3.28

7 0.33

3.30

3.31

3.22

0.27

3.10

a

3.41

b

3.25

3.38 *

3.24

3.48

7 1.73

c

requirements

(1.04)

(1.02)

(1.04)

(1.04)

(1.01)

(1.04)

(1.05)

(.93)

(1.05)

(.84)

Emotional

3.41

3.42

7 0.16

3.47

3.24

3.39

1.45

3.37

3.46

3.39

0.46

3.40

3.43

7.23

dissonance

(.87)

(.85)

(.88)

(.92)

(.80)

(.83)

(.91)

(.82)

(.86)

(.94)

**p

5 .01; *p 5 .05; variance analyses with Bonferroni post hoc analyses: line 1: means; SD in parentheses;

a

and

b

: groups with different letters are

significantly different (p

5 .05);

c

imhomogeneous variance, T-test for pooled variances used.

331

Table 5 also shows correlations between the percentage of time working

on the telephone. As expected there were substantial negative correlations

between complexity and control and telephone time, with the highest

correlation for timing control (hypothesis 6a). Negative correlations were

also found for time pressure, concentration, and cooperation demands. As

expected, there was a positive correlation with positive emotions; however,

contrary to expectations, a negative correlation with the frequency to

express negative emotions occurred and no correlation was detectable for

sensitivity requirements and emotional dissonance. Thus Hypothesis 6b

could only be supported for one of the four emotion work variables.

With regard to inbound vs. outbound activities, those jobs with both

inbound and outbound activities were distinguished by the highest

complexity and control, whereas inbound calls only and outbound calls

only were not statistically different (Hypothesis 7). Outbound activities were

characterized by less job stressors than inbound activities as well as the

combination of both. Only for uncertainty no differences were found.

Finally, positive emotions were higher for outbound activities but no

differences were realized for the other emotion work variables.

In addition, Table 5 also reports results of multiple regressions with

resources, job stressors, and emotion work as the dependent variables and

the organizational call centre variables as the independent variables. The

table shows that the call centre variables explain considerable variance for

complexity and job control and they explain least variance for the emotion

work variables. The most important independent variable in these analyses

is percentage of telephone time, which significantly contributes to complex-

ity and all control variables, concentration and cooperation demands, and

the requirement to display positive emotions. All other call centre variables

are only occasionally significant in these analyses.

DISCUSSION

Call centres are among the few booming operations in recent years. The

main task in call centres is to interact with customers by telephone, usually

supported by computer systems used to organize and automate parts of the

job. In this article we compared complexity, control, job stressors, and

emotion work in a sample of call centre employees and in a comparison

group consisting of service workers, human service workers, and workers

who had no service jobs (mainly blue collar jobs and administrative jobs).

We found that jobs in call centres were characterized by lower complexity

and control, but call centre workers were better off with regard to most job

stressors compared to the comparison groups. These effects become even

stronger when CSRs without leadership responsibilities are considered only

(cf. Table 6, column 9). Moreover, CSRs had to express less negative

332

ZAPF ET AL.

emotions but were most frequently exposed to emotional dissonance

although the statistical differences were not all significant for the single

call centres. Concerning requirements to express positive emotions and to

demonstrate sensitivity they were between other service workers, the group

they are most comparable with, and human service workers. Looking at the

differentiated results of eight call centres revealed job-related deficits in most

but not all call centres. Mixed results arose from the analysis of job stressors.

The percentage of time working with customers on the telephone explained a

substantial part of the differences among call centres. The percentage of

telephone time was negatively correlated with complexity and control as well

as with some of the job stressors and it was positively correlated with the

requirement to display positive emotions.

The present results support the view that the majority of call centres—

that is both inbound and outbound call centres with relatively simple

tasks—have been established to organize customer mass service (Holman,

2003). However, there are also call centres in our study that belong to the

‘‘customer relationship’’ type, at least with regard to complexity and

control. This applies for Call centre 5, which is a hotline for technical

questions where people perform relatively complex tasks. Similar but less

pronounced results were found for Call centre 2, which is an inhouse call

centre in the tourism sector. Contrary to many expectations, the job

stressors in some call centres were lower than in the comparison groups.

This was especially so in Call centre 1, the only outbound call centre.

Looking at the various call centres substantial differences between the call

centres were revealed. Workers in Call centre 5 scored maximally with

regard to time pressure and concentration demands, as did people in human

service work. Again, similar, but less pronounced results were found for Call

centre 2. On the other hand, three call centres had significantly less

organizational problems and two call centres had significantly lower

cooperation demands than all comparison groups. Our results do not

support the conclusion that call centre jobs are generally more stressful with

regard to job stressors. The results for job complexity, control, and job

stressors support the findings of an earlier study (Isic et al., 1999). Call

centres seem to be well organized as indicated by the low levels of

uncertainty and organizational problems, certainly in comparison with

many other service organizations. This may be the result of relying heavily

on information technology supporting the distribution of calls and directing

the course of CSR – customer interactions. However, the data also show that

this leads to lower control and participation by the CSRs. Thus it can be

concluded that the problem in many call centres is not the high level of job

stressors but the low level of resources that could help to buffer the negative

effects of stressors (Hobfoll, 2001; Lazarus, 1999; Zapf & Semmer, in press).

This conclusion has to be validated, however, because although we

TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CALL CENTRE JOBS

333

measured a variety of stressors, we were not able to measure all stressful

aspects of the job. For example, we did not check whether performance was

monitored electronically, which appeared to be a stressor in the study by

Holman (2002).

With regard to emotion work, there usually are strict display rules.

Observing these rules is often enforced by electronic performance monitor-

ing in many call centres (Baumgartner, Good, & Udris, 2002; Holman, 2003;

Schuler, 2000). The frequency of customer contacts in call centres is

generally higher than in other service jobs. This could explain the fact that

CSRs are more often required to express positive emotions in comparison to

other comparable service professions. However, the absence of having to

display negative emotions seems to be specific for all call centres. Indeed,

CSRs’ tasks do not seem to include the demonstration of negative emotions

(the mean is between ‘‘almost never’’ and ‘‘once a month’’). This is in

contrast to the jobs of human service workers. A social worker, for example,

sometimes has to express negative emotions to reach certain goals. Being

allowed to display a variety of emotions may sometimes alleviate the task

for human service workers (Zapf, Seifert, Schmutte, Mertini, & Holz, 2001).

The display rules for human service workers are much less restrictive. In

most call centres CSRs are expected to display friendliness and politeness

(see, e.g., the study of Deery et al., 2002). The organizational display rules

do not allow the display of any negative emotion. This could explain why

emotion work in human services jobs seems to be more frequent and more

intensive compared to work in call centres, although emotional dissonance

seems to be higher in call centres.

The organizational call centre variables have relatively little effect on

emotion work. Only a few relations were significant, supporting the view

that a high level of the requirement to express positive emotions, a very low

level to express negative emotions, and a relatively high level of emotional

dissonance resulting from both seem to be typical for call centres in general,

almost independent of the specific call centre organization.

When considering organizational and task characteristics of the call

centres, it turns out that the percentage of time spent at the telephone

interacting with customers is one of the key variables. The more time CSRs

spend on the telephone the less complex the tasks are and the less control

they have. However, there is also an increase of time pressure, concentration

requirements, and cooperation demands. It is a frequent finding in our