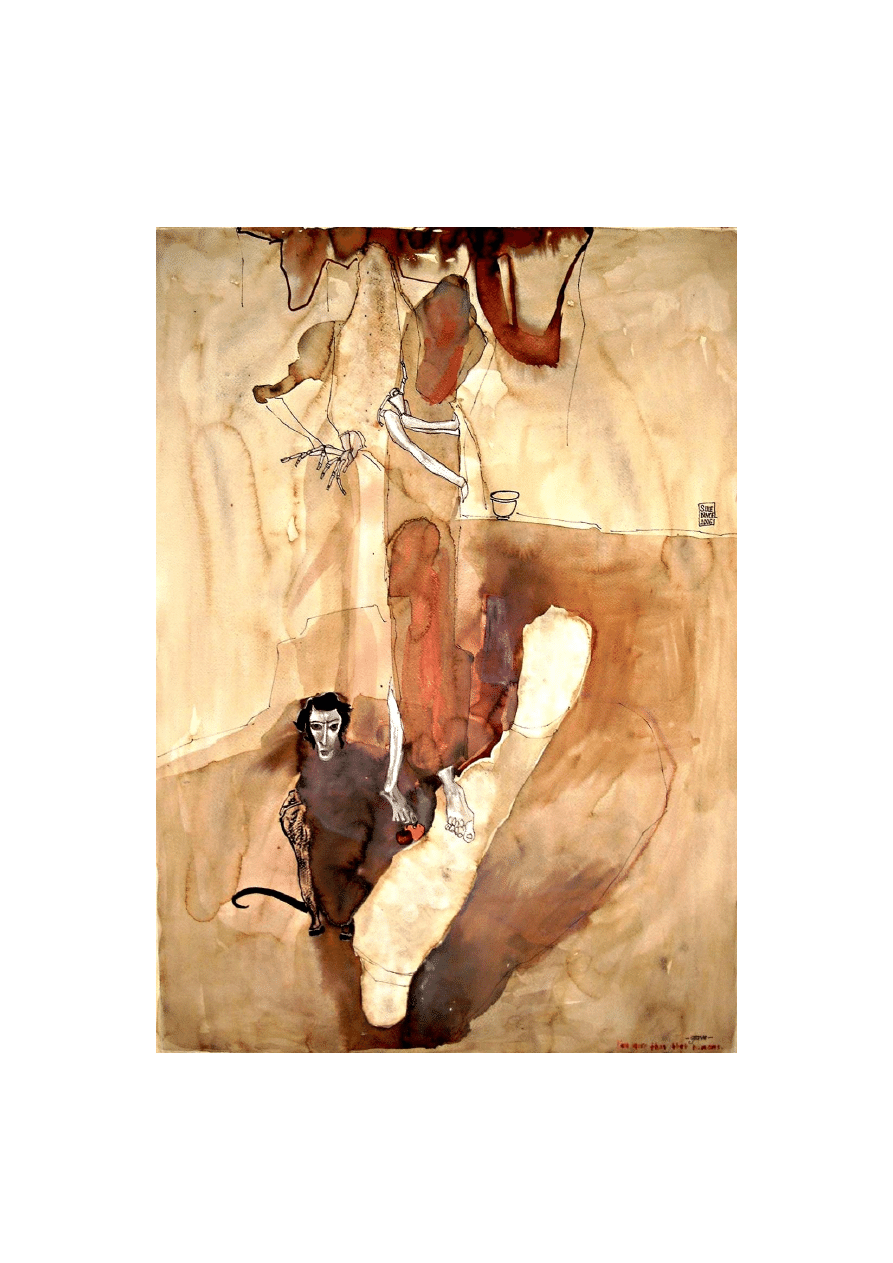

Assumptions

Of

Solution-Focused Therapy

MESSAGE FROM THE INCORPORATED SOLUTIONS TEAM

Traditionally therapists have been taught to seek the underlying causes of a client’s problem

in order to affect a “cure,” and to understand what psychodynamic “function” problems serve

before beginning to modify or ameliorate symptomatic behavior. The solution-focused

approach shifts the traditional psychotherapy framework 180 degrees, inviting both the

therapist and the client to concentrate instead on the solution.

With the solution-focused approach the therapist helps clients prioritize issues according to

their individual perceptions, and establish a clear picture of what life will be once the

presenting problem is resolved. In addition to asking problem-focused questions (which often

perpetuate feelings of disempowerment or hopelessness), the therapist emphasizes

competency-oriented questions which elicit the client’s strengths and successes. By

demonstrating interest in the existence of the client’s competence, the therapist provides a

nucleus for hope, growth and problem resolution. Clients, when encouraged to notice even the

smallest of changes, begin to make distinctions that previously went unobserved, and begin to

identify patterns in thoughts, feelings and behavior that facilitate solutions.

Elegant in its simplicity, solution-focused therapy rewards the therapist’s creative curiosity,

gentle persistence and infinite respect. It is a constructive treatment strategy that works well

with a broad range of presenting problems, and empowers clients through promoting their

pre-existing competence. We are pleased to share this perspective with you.

Cynthia K. Hansen, Ph.D.

JoAnna Henry, LC.S.W.

Stuart Levy, LC.S.W.

Phillip R. Trautmann, M.D.

© Incorporated Solutions, (503) 223-9320,

cindyh@teleport.com

Do not copy without written permission from Incorporated Solutions

Assumptions

Of

Solution-Focused Therapy

People bring to therapy natural abilities that can be utilized in interventions.

People are doing the best they can under the circumstances.

Change is inevitable.

Small changes can lead to big changes.

The cause of a problem need not be discovered in order to solve it.

Solution building is more effective than problem solving.

The Central Philosophy of

Solution-Focused Therapy

If it works, don't fix it.

If it worked once, do it again.

If it doesn't work; don't do it again-

Do Something Different.

FIVE USEFUL QUESTIONS

Adapted from Steve de Shazer/BFTC

1.

Pre-Session Change

2.

Exceptions

3.

The Miracle Question

4.

Scaling Questions

5.

Coping Questions

Pre-Session Change Question

Purpose:

To seek exceptions to the problem and find pre-existing solutions.

Values:

Creates expectation of change for the better.

Emphasizes the client as the initiator of change.

Places responsibility for change on the client.

Demonstrates that change can happen outside the therapist's office.

Example:

"People frequently tell me that between the time they make the phone call and the time

they come in for their appointment, things have already begun changing for the better.

I'm wondering how true that is for you with this problem. What has helped so far?”

EXCEPTIONS

Purpose:

To clarify conditions for change.

Value:

Implies the client's strengths and ability to solve problems.

Focuses on tangible evidence of resolution.

Reorients the client to the hope of finding solutions.

Examines resources that may have been forgotten or ignored.

Examples:

"When have you overcome this problem (or some other problem) in the past, even

briefly? What did you do differently then?"

"When were things better, even just a little?"

"When do you experience this problem the least?"

"Are there times when it could have gotten worse but didn't?"

"Are there times when things aren't quite so bad?"

MIRACLE QUESTION

Purpose:

To clarify goals and highlight exceptions to the problem.

Value: Implies the problem is solvable.

Stimulates the client to imagine the solution.

Removes real or imagined constraints in solving the problem.

Projects the client into a time or place when the problem is solved.

Focuses on tangible evidence of resolution.

Builds hope for change.

Examples:

"Suppose after you leave our meeting you go about your

normal activities until bedtime. But then tonight, after

you go to sleep a miracle happens and the problem that

brought you here is solved. But you don't know it

because you are asleep. So when you wake up tomorrow

morning what will be the first thing you notice that

tells you this miracle happened last night?"

"What will you be doing differently? What else?"

"Who else will notice that the miracle happened?"

"How will they know?"

"What's the closest you've come to anything like you've

described?"

"When was the last time a part of this miracle happened?”

Scaling Questions

Purpose:

To quantify intangibles.

Value:

Makes the abstract concrete.

Identifies movement within (and between) a session.

Underscores the significance of small change.

Increases perspective.

Helps clients and therapist know when treatment is

finished.

Examples:

"On a scale of zero to 10, where 10 means you're willing

to do anything it takes to change your situation, and zero

means the opposite, where would you place yourself

today?"

"On a scale of zero to 10, where 10 is where you want to

be when therapy is successful and zero is where you

were when you picked up the phone to make this appointment, where would

you place yourself now?"

"Where on this scale do you think others (parent, friend,

teacher) would place you?"

"What do you need to do to move a half point up the

scale?"

"On a scale of zero to 10, where 10 means you are

absolutely confident that you can continue to do what

you're doing and zero is the opposite, where would you

place yourself now?"

Coping Questions

Purpose:

To join empathetically with the client who feel hopeless or stuck.

Value:

Acknowledge the problem as well as the client's own available

resources for solution.

Re-emphasize that the client could be doing worse but isn't.

Helps therapists pace themselves.

Provides an alternative view of a difficult situation.

Highlights movement that has already occurred.

Examples:

"This must be very painful for you. How have you been able to cope with this

situation?"

"Considering how bad things are now, what have you been

doing to keep things from getting worse? What else? How has

that been helpful? How did you think of doing it that way

rather than another way?"

"How did you know what you needed to do?"

"What have you been doing to keep going? What else?"

ASSESSING CLIENT/ THERAPIST

RELATIONSHIPS

The Visitor-Type Relationship

At the end of the discussion the client and therapist either have not constructed a

complaint or a goal, or the client dies not feel there is anything he or she could do

about the problem that will make a difference. Often the problem at hand is not a

major concern, and the client has been sent by someone else.

The Complaint-Type Relationship

The therapist and client are able to identify and discuss the problem and observe and

track problem sequences, but are not able to identify the steps the client needs to take

to solve the problem. In this relationship, the client is often willing to notice things or

consider alternatives.

The Customer-Type Relationship

The client and therapist are able to identify a complaint and a goal. The client is

willing to do something different (often as an experiment) and undertake the hard

work required to make things change.

The Well-Formed Goal

The development of well-formed goals is a significant predictor of successful outcome.

Focusing on the client's most pressing need, client and therapist work together to negotiate

goals by clarifying what specific change will make a difference, and forming a tangible

picture of what that change will look like.

Well-formed goals are:

1.

Described in terms of client's interactions with others.

2.

Small rather than large.

3.

Described in specific, concrete terms.

4.

Described as the start of something rather than the end of something.

5.

Described as the presence of something rather than the absence of

something.

6.

Perceived by clients as involving their own hard work.

7.

Realistic and achievable within the client's life.

DESIGNING INTERVENTIONS

The whole therapy session becomes an intervention when we design questions that

invite the client to think about solutions rather than problems.

At the end of a session (typically after a "consultation break") a more formal

intervention can be delivered in the form of a summary which amplifies, reinforces and helps

continue the shift in thinking that has been taking place.

The following points guide the design of interventions, whether during the interview or

at the end:

1.

Address the clients pressing needs first.

2.

Agree with the client's goal.

3.

Use the client's words.

4.

Compliment what the client is doing toward his or her goal.

5.

Provide a rationale for any return appointment or therapeutic task.

("Since . . . " "I agree that . . . ")

Suggest Therapeutic Tasks (see following page)

DESIGNATING INTERVENTIONS (continued)

Therapeutic Tasks

With a Visitor-type client/therapist relationship:

After Compliments --

Offer a Return Appointment with Rationale but no task.

With a Complaint-type client/therapist relationship:

Give Compliments and Rationale --

Then offer an Observing Task (with the goal of finding

exceptions or making spontaneous exceptions deliberate).

With a Customer-type client-therapist relationship:

Give Compliments and Rationale--

Then offer a Doing Task, guided by the Central Philosophy --do

more of what is working--

or

If nothing is working, Do Something Different

(literally anything different --different time, different place,

with different people, etc.)

THERAPEUTIC COMPLIMENTS

Purpose:

Compliments are used throughout the interview. During the conversation,

indirect compliments are used to elicit more information for the therapist

detailing that the client has been doing that is helpful or useful. At the end of

the session (typically after a consultation break) direct compliments are used

formally as the first part of a therapeutic message to let clients know the

therapist has listened carefully.

Value:

Compliments shift the client and therapist’s perspective by underscoring what

the client is able to do that is helpful and useful.

Compliments highlight

something the client is doing

something that the client values

something that is productive and healthy

something that seeds the possibilities for change

Examples of Indirect Compliments:

"How were you able to do that?"

"How did you know that would work?"

"How did you figure that out?"

Examples of Direct Compliments:

(Base the compliment on what is helpful to the client in

achieving goals. Use the client's words, elicited during the

interview.)

"I'm impressed that giving the rough week you've had, you've been able to

maintain your sobriety and even walk away when a drink was offered you . . ."

THE RATIONALE

(The "Bridging Statement")

Purpose:

The Rationale provides a link between what the client wants and can do and

what the therapist suggests.

Value:

Recognize and acknowledge the client's current experiences.

Assures the client that the therapist has listened carefully to his/her words.

Increases the likelihood that the client will follow through with the task.

Relates the client's experiences with the task.

Explains the therapist's thinking and makes the task seem logical from the

client’s perspective.

Example:

"I'm impressed with how hard you've worked this week to handle your angry

feelings without hurting your spouse. Because what you've been doing has

begun to make a difference in your spouse's level of trust in you-- moving from

a 2 to a 3 -- and since we agree with you that trust is essential for a good

marriage. . ."

General Flow of the Interview

Pre-Session:

Invite everyone who might be useful to come to the first session.

First Session:

Join clients' view of the problem

Miracle Question

Search for Exceptions

Ask about Pre-Session Change

Clarify progress and confidence in motivation with Scaling

Break For Consultation (with team or with self)

Deliver Message:

Visitor-type relationship

---> Compliment and Rationale

Complainant-type relationship ---> Compliment and Rationale plus

Observing Task

Customer-type relationship ---> Compliment and Rationale plus Doing

Task

General Flow of the Interview

(continued)

Subsequent Sessions

Report of client's experience

Standard first question: "So what is better since the last time we met?"

Focus on any positive change

Amplify positive changes (who, what , when, where?).

Ultimately underscore the significance of change

(Is it enough change?")

Break for Consultation (with team or with self)

Deliver Message

Visitor-type relationship :

----> Compliment and Rationale

Complainant-type relationship:

---> Compliment and Rationale,

plus Observing task

Customer-type relationship:

----> Compliment and Rationale,

plus Doing task

Interviewing Activities Sheet

- The questions listed here are ones the therapist needs to consider in order to generate an intervention.

These are not questions that clients answer directly and they do not need to be addressed in any

particular order.

1. Is there a joint work project?

[ ] Yes

[ ] No

2. Is there an exception?

[ ] Yes

[ ] No

If Yes, is the exception

[ ] Deliberate

[ ] Spontaneous

3. Is there a goal?

[ ] Yes

[ ] No

If Yes, is the goal

[ ] Well- defined?

[ ] Vague?

4. Are the goal and the exception related?

[ ]Yes

[ ] No

5. What is the client- therapist relationship?

[ ] Visitor-type

[ ] Complainant-type

[]Customer-type

Compliment

Bridging Statement

Task

Solution Identification Scale S-Id

Name

Date

Rated By:

Not at allJust a littlePretty MuchVery Much1. Respectful to grown-ups2. Able to make/keep friends3. Controls

excitement4. Cooperates with ideas of others5. Demonstrates ability to learn6. Adapts to new situations7. Tells the truth8.

Comfortable in new situations9. Well behaved for age10. Shows honesty11. Obeys adults12. Handles stress well13.

Completes what is started14. Considerate to others15. Shows maturity for age16. Maintains attention17. Reacts with proper

mood18. Follows basic rules19. Settles disagreements peacefully20. Gets along with brothers/sisters21. Copes with

frustration22. Respects rights of others23. Basically is happy24. Shows good appetite25. Sleeps OK for age26. Feels part of

the family27. Stands up for self28. Is physically healthy29. Can wait for attention/rewards30. Tolerates criticism well31. Can

share the attention of adults with others32. Is accepted by peers33. Shows leadership34. Demonstrates a sense of ìfair

playî35. Copes with distractions36. Accepts blame for own mistakes37. Cooperates with adults38. Accepts praise well39.

Able to ìthinkî before acting

40. Comments:

Bibliography

Berg, Insoo, (1991). Family Based Services: A Solution- Focused Approach.

New York: Norton. Written for social service program addresses in-

home consultations. A concise description of the model applied to

multi- problem mandated families.

Berg, Insoo Kim, and Miller, Scott(1992). Working with the Problem Drinker.

New York: Norton. A practical and thorough description of solution

focused therapy, illustrated with applications to problem drinkers .

Berg, Insoo Kim and Dolan, Yvonne(2001). Tales of Solutions. New York:

Norton. An inspiring collection of stories illustrating applications of

solution focused therapy in a variety of clinical settings by therapists

from around the world

Berg, Insoo Kim, and Kelly, S.(2000) Building Solutions in Child Protective

Services. New York: Norton. Addresses the complexities and

idiosyncracies of applying solution focused principles to child

protective services.

Berg, Insoo Kim and Reuss, Norm(1997).Solutions Step-by-Step: Substance

Abuse Treatment Manual. A manual for learning solution-focused

strategies when applied to people with substance abuse problems.

Berg, Insoo Kim and Steiner, Therese(2003) Children’s Solution Work. New

York: Norton. A warm, wonderful book describing solution focused

strategies applied to therapy with children.

Cade, Brian, and O'Hanlon, William(1993). A Brief Guide to Brief Therapy.

New York: Norton. Reviews the different approaches to brief therapy

derived from the traditions of family therapy and the work of Milton

Erickson. Describes therapeutic strategies basic to this work.

Chevalier, A.J. (1995). On the Client's Path: A Manual for the Practice of

Solution- Focused Therapy. California: New Harbinger. Written by a

professor who studied six years at BFTC to provide a format for

teaching students the solution-focused model.

de Shazer, Steve (1985). Keys to Solution in Brief Therapy. New York:

Norton. AN in depth discussion of "skeleton-key interventions" and

traces the initial shift from problems solving to solution building.

Perhaps de Shazer's most accessible book.

de Shazer, Steve (1988) Clues: Investigating Solutions in Brief Therapy. New

York: Norton. Includes a clinical road map for using the model as well

as a BFTC research summary.

de Shazer, Steve (1991). Putting Difference to Work. New York: Norton. The

most philosophical look at the model and the therapeutic use of

language.

de Shazer, Steve (1994). Words Were Originally Magic. New York: Norton. de

Shazer's latest thinking on the therapeutic implications of language.

Analysis of transcripts from actual therapy sessions.

DeJong, Peter and Berg, Insoo(1998) Interviewing for Solutions. A textbook

and practice manual for teaching students solution-focused therapy in a

university setting.

Dolan, Yvonne (1991). Resolving Sexual Abuse. New York: Norton.

Working with adult survivors using solution- focused and Ericksonian

hypnotic approaches.

Furman, Ben and Tapani, Ahola (1992). Solution Talk: Hosting Therapeutic

Conversions. New York: Norton. A multicultural perspective with

innovative ideas for consultation.

Kral, Ron (1995). Strategies that Work: Techniques for Solutions in Schools.

Milwaukee: BFTC Press. Written for consultation and intervention in

schools. Practical description of the model.

Lipchik, Eva (1994). The rush to be brief. The Family Therapy Networker.

March/April, 35-39. Addresses importance of pacing with clients, the

danger of pursuing content at the expense of process.

Metcalf, Linda(1995). Counseling Toward Solutions. Center for Applied

Research in Education. West Nyack, N.Y. 10994. The most recent book

written for school professionals applying competency-based models to

their work (solution- focused and narrative). Great worksheets and

handouts for groups, IEP meetings and classroom use.

Miller, Gale(1997). Becoming Miracle Workers. New York: Walter deGruyler,

Inc. A fascinating sociological and constructivist perspective on the

training and mindset of solution focused therapists.

Nylund, David, and Corsigila, Victor(1994). Becoming solution-forced in brief

therapy. Journal of Strategic Therapy. 13, 1, p.5-11. A tongue in cheek

article highlighting the inadequacies of a cookbook approach to

employing solution- focused questions.

O'Hanlon, William and Weiner-Davis, Michele(1989). In Search of Solutions:

A New Direction in Psychotherapy. New York: Norton. Easy reading.

"The first book to read" on solution-focused therapy.

O'Hanlon, William and Hudson, Patricia (1991). Rewriting Love Stories. New

York: Norton. Describes a solution- focused approach to marital

therapy. Very readable.

Prew, Cheryl, et al. Post-Adoption Family Therapy: A Practice Manual.

Adoption Services, Services for Children and Families, 1988

Commercial St. S.E., Salem, OR 97310-0450. A practical solution-

focused guide for adoptive foster and mixed families.

Walter, John and Peller, Jane 9 (1992). Becoming Solution- Focused in Brief

Therapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel. Useful for the clinician who is

learning to shift from problem-focused to solution focused therapy.

Details therapeutic process. Q and A sections address common

struggles, suggest exercise.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Be Wary of Simoncini?ncer Therapy

Betty Grover Eisner, Ph D Remembrances of LSD Therapy Past (2002)

Modern progress of mechanism of moxibustion therapy

Borderline Pathology An Integration of Cognitive Therapy and Psychodynamic Thertapy

The Benefits of Massage Therapy

20979544 Application of Reality Therapy in clients with marital problem in a family service setting

(IV)The effect of McKenzie therapy as compared with that of intensive strengthening training for the

Elizabeth Brooks Assumption Of Desire

The Physical Benefits of Massage Therapy

Evidence for Therapeutic Interventions for Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain During the Chronic Stage of Stro

Kinesio taping compared to physical therapy modalities for the treatment of shoulder impingement syn

Fundamentals of Therapy

ASSUMPTIONS AND PRINCIPLES UNDERLYING STANDARDS FOR?RE OF T

The term therapeutic relates to the treatment of disease or physical disorder

Ferrell Gerson Therapy for Those Dying of Cancer

Hypothesized Mechanisms of Change in Cognitive Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder

or The Use of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy to Improve Fracture Healing

więcej podobnych podstron