Variation and

Morphosyntactic Change

in Greek

From Clitics to Affixes

Panayiotis A. Pappas

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

Palgrave Studies in Language History and Language Change

Series Standing Order ISBN 0–333–99009–9

(outside North America only)

You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order.

Please contact your bookseller or, in case of difficulty, write to us at the address below with

your name and address, the title of the series and the ISBN quoted above.

Customer Services Department, Macmillan Distribution Ltd, Houndmills, Basingstoke,

Hampshire RG21 6XS, England

Palgrave Studies in Language History and Language Change

Series Editor: Professor Charles Jones

This new monograph series will present scholarly work in an increasingly

active area of linguistic research. It will deal with a worldwide range of language

types and will present both descriptive and theoretically-orientated accounts of

language change through time. Aimed at the general theoretician as well as the

historical specialist, the series will seek to be a meeting ground for a wide range

of different styles and methods in historical linguistics.

Titles include:

Panayiotis A. Pappas

VARIATION AND MORPHOSYNTACTIC CHANGE IN GREEK

From Clitics to Affixes

Ghil‘ad Zuckermann

LANGUAGE CONTACT AND LEXICAL ENRICHMENT IN ISRAELI HEBREW

Forthcoming titles:

Betty S. Phillips

WORD FREQUENCY AND LEXICAL DIFFUSION

Variation and

Morphosyntactic Change

in Greek

From Clitics to Affixes

Panayiotis A. Pappas

© Panayiotis A. Pappas 2004

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this

publication may be made without written permission.

No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted

save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence

permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90

Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP.

Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication

may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published 2004 by

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN

Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010

Companies and representatives throughout the world

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave

Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom

and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European

Union and other countries.

ISBN 1–4039–1334–X

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully

managed and sustained forest sources.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pappas, Panayiotis A., 1971–

Variation and morphosyntactic change in Greek / Panayiotis A. Pappas.

p. cm. — (Palgrave studies in language history and language change)

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 1–4039–1334–X

1. Greek language, Medieval and late—Pronoun. 2. Greek language,

Medieval and late—Syntax. 3. Greek language, Medieval and late–

–Clitics. 4. Greek language, Medieval and late—Affixes. I. Title. II. Series.

PA1085.P36 2003

487’.3—dc21

2003054874

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

13

12

11

10

09

08

07

06

05

04

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham and Eastbourne

v

πáντα ε, οδèν δè μéνει

Heracleitus (Fr. 20)

This page intentionally left blank

vii

Contents

List of Figures

List of Tables

Preface

List of Abbreviations

1.

Introduction

Preliminaries

Summary of the placement of unstressed elements throughout

the history of Greek

Weak object pronoun placement in Later Medieval Greek

texts

Previous descriptions

Rollo (1989)

Mackridge (1993, 1995)

Contribution of the study

2.

Methodology

Linguistic usage vs. linguistic competence

Compiling a corpus of texts

Accountability and the linguistic variable in morphosyntactic

research

Defining the set of variants

The possessive pronouns

The definite article and relative pronouns

Conclusion

3.

Data Analysis

Raw data

Data analysis

Postverbal placement of pronouns

Preverbal placement of pronouns

Comparing postverbal and preverbal pronoun placement

Conclusion

4.

Linguistic Parameters

The distinction between

ο and ν ο

Differentiation within the factor reduplicated object

The effect of emphasis on pronoun placement

x

xi

xiii

xvii

1

1

4

6

8

8

9

12

15

15

18

22

26

26

27

29

30

30

34

35

38

41

43

44

44

51

55

viii

Contents

The effect of discourse constraints on pronoun placement

Weak object pronoun placement with non-finite forms of the

verb

Participles

Present Active

Perfect Passive

Gerund

Infinitives

Articular Infinitive

Infinitive as the complement of a verb

Imperative

Conclusion

5.

Non-linguistic Parameters

Metrical constraints and weak object pronoun placement in

LMG texts

The interaction between accent and pronoun placement

The effect of the caesura

Pronoun placement according to chronology and geography

Conclusion

6.

Previous Proposals

Previous explanations for the LMG facts

Horrocks (1990)

Philippaki-Warburton (1995)

Horrocks (1997)

Condoravdi and Kiparsky (2001)

Syntactic approaches to similar phenomena in other languages

Weak object pronoun placement in Old Spanish

Wanner (1991)

Fontana (1993)

Weak object pronoun placement in Bulgarian and Old French

Weak object pronoun placement in some Modern Greek dia-

lects

Other general approaches

Conclusion

7.

A Diachronic Perspective

Pronoun placement in 17

th

century Greek: poetry vs. prose

Examining the pattern of variation from a diachronic perspec-

tive

Further implications for Later Medieval Greek

Conclusion

57

60

61

61

62

63

63

64

64

70

72

73

73

75

81

83

89

92

92

93

93

97

99

104

104

104

106

111

113

114

116

117

117

125

132

135

Contents

ix

8.

Theoretical Implications

Are the weak object pronouns of LMG clitics or affixes?

The development of ‘atypical affixes’ in LMG and the theory of

‘grammaticalization’

Concrete contexts of linguistic change

Grammars with less-than-perfect-generalizations

Conclusion

Appendix: Tables showing variation by text

Notes

References

Index

136

137

141

143

146

150

152

166

170

183

x

List of Figures

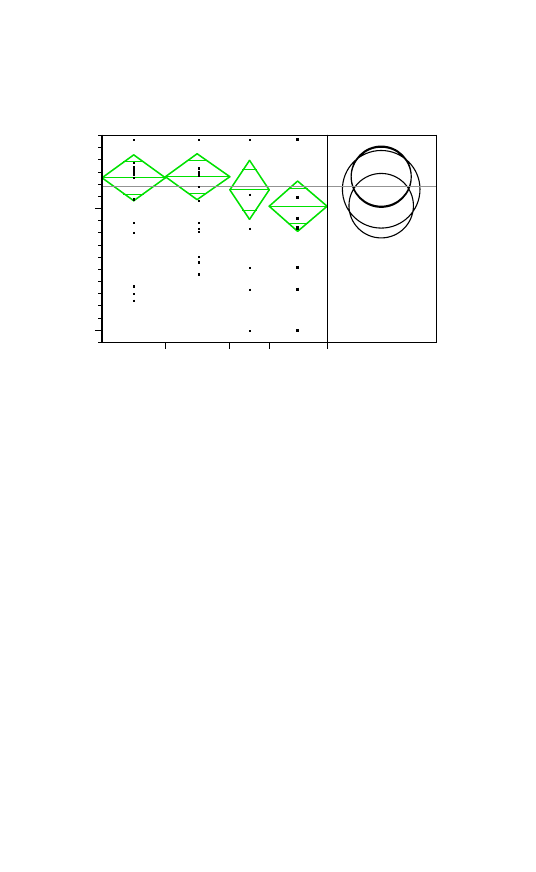

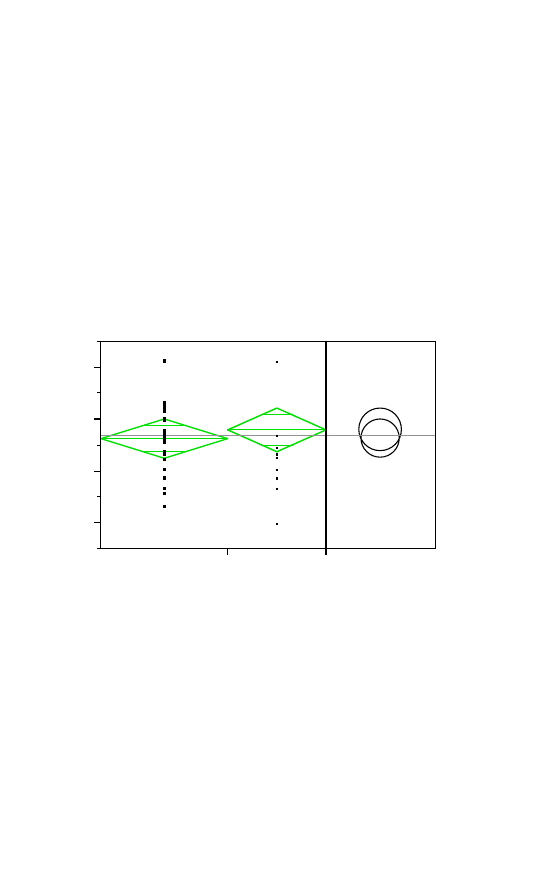

Figure 1.1

Figure 3.1

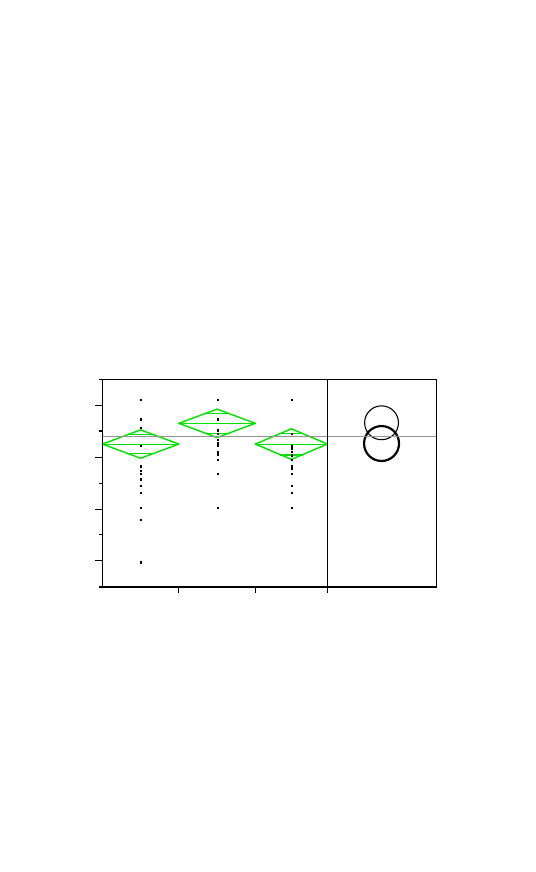

Figure 3.2

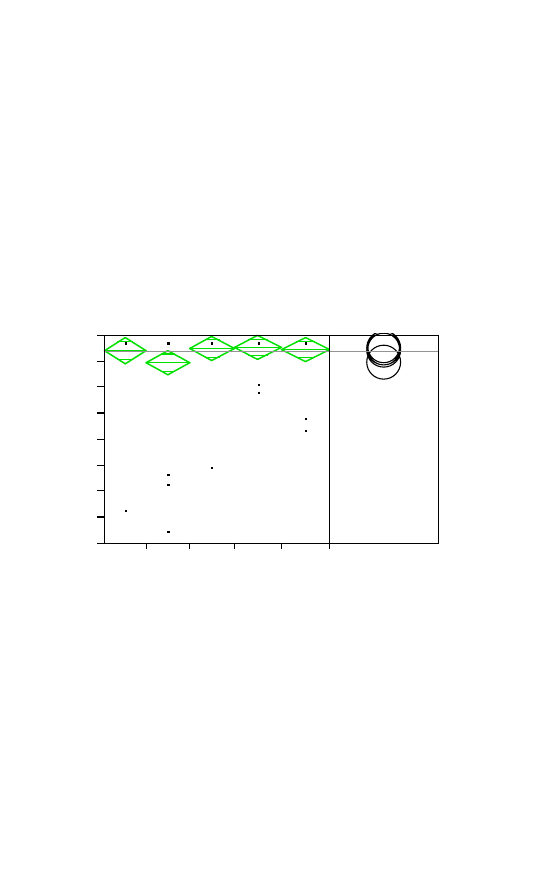

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.4

Figure 3.5

Figure 4.1

Figure 4.2

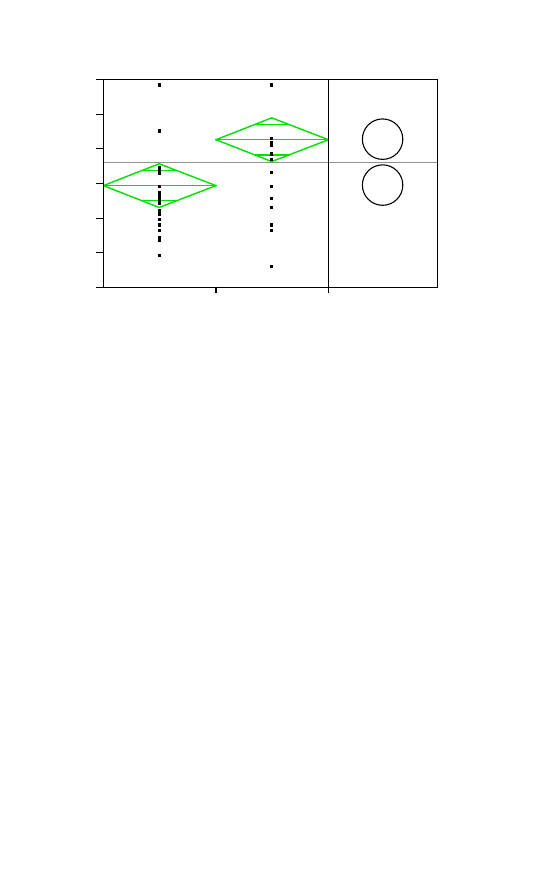

Figure 4.3

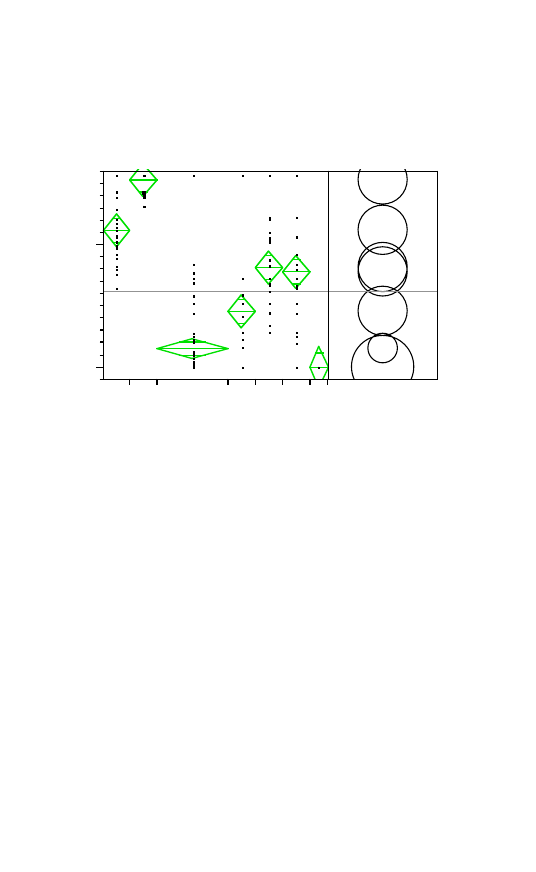

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.2

Scale of weak object pronoun placement in LMG according

to Mackridge (1993)

Postverbal pronoun placement for Group 1

Preverbal pronoun placement for Group 2

Preverbal pronoun placement for Group 3

Preverbal pronoun placement by factor

Diagrammatic ranking of pronoun placement

Comparing factors in Group 1 but excluding tokens with

λος from the factor reduplicated object

Four-part analogy schema for the change in pronoun

placement in

λος constructions

Comparing pronominal vs. nominal subjects

Comparison of the effect of metrical requirements on factors

fronted constituent vs. subject and temporal expression

Diagrammatic comparison of the initial and final description

of weak object pronoun placement in LMG

10

36

39

40

42

43

54

55

57

78

90

xi

List of Tables

Table 1.1

Table 1.2

Table 3.1

Table 5.1

Table 5.2

Table 5.3

Table 6.1

Table 7.1

Table 7.2

Table 7.3

Table A.1

Table A.2

Table A.3

Table A.4

Table A.5

Table A.6

Table A.7

Table A.8

Table A.9

Table A.10

Table A.11

Table A.12

Forms of the weak pronouns in Later Medieval Greek texts

Forms of the full pronouns in Medieval Greek

Results of token count based on Mackridge’s classification

Pronoun placement in the Cypriot chronicles

Pronoun placement in western texts according to factor

initial

Pronoun placement in western texts according to factor

coordinating conjunction

Possible verb positions in Later Medieval Greek

Pronoun placement by factor in prose texts from different

areas in 17

th

century Greek

Pronoun placement by factor in 17

th

century Cypriot texts

Pronoun placement by factor in 17

th

century Cretan poetry

Raw counts of pronoun placement for factors initial and

coordinating conjunction

Raw counts of pronoun placement for factors

διóτι and τι

Raw counts of pronoun placement for factors

ο, δé and

reduplicated object

Raw counts of pronoun placement for factors relative pro-

noun, negation, and interrogative pronoun

Raw counts of pronoun placement for factors

νá, να, and

ς

Raw counts of pronoun placement for factors tempo-

ral/comparative conjunction,

áν, ν, and πẃς

Raw counts of pronoun placement for factors object,

prepositional phrase, and non-temporal adverb

Raw counts of pronoun placement for factors subject, and

temporal expression

Raw counts of pronoun placement in the contexts

ν ο

and

ο μ

Raw counts concerning the interaction between the pres-

ence of

λος and pronoun placement

Raw counts concerning the interaction between

θéλω peri-

phrastic constructions and pronoun placement

Raw counts concerning the interaction between imperative

verb-forms and pronoun placement

2

3

33

85

88

89

109

118

119

121

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

xii

List of Tables

Table A.13

Table A.14

The effects of metrical requirements on preverbal place-

ment for factors fronted constituent vs. subject and tempo-

ral expression

Verb position by text in Later Medieval Greek

164

165

xiii

Preface

The language of popular Greek literature of the late Byzantine period (12

th

-16

th

century) displays an ordering phenomenon that can only be described as con-

founding. The weak pronominal forms that serve as arguments to a verb must be

adjacent to it, but may appear either before it or after it, as shown in examples

(1) and (2).

(1)

πáλε σς

λαλ

palE

sas

lalo

again

you–IOpl WP

say–1sg Pres

‘Again I say to you’ (Moreas, 715)

(2)

πáλιν

λéγω

σας

palin

lEVo

sas

again

say–1sg Pres

you–IOpl WP

‘Again I say to you’ (Digene

¤

s, 1750)

The present study is a reevaluation of this phenomenon that challenges not

only the analyses that have been proposed so far, but also some important as-

pects of the description of the facts. Up until the last ten years or so, this phe-

nomenon was noticed mainly by those working on critical editions of manu-

scripts, and they only offered descriptive lists for the particular text at hand. In

1989, Antonio Rollo published an article, which took a closer look at the phe-

nomenon and noted certain similarities between the variation in Later Medieval

Greek (LMG) and what has become known as the Tobler-Mussafia ‘Law’ in the

Romance languages. In 1990, a brief description of the facts and a tentative pro-

posal to account for them appeared in Horrocks’ survey of clitic position in the

history of Greek. It was, however, Mackridge’s (1993, 1995) work that brought

the phenomenon to prominence by providing a detailed examination of the

variation and proposing a set of ‘rules’ to account for it. Since then, Mackridge’s

description of the phenomenon has been accepted as the standard.

The factual challenges presented in this book arise from the use of a different

methodology, which combines the traditional belief that ‘every attestation

counts’ with the use of statistical tools to determine which patterns of variation

are significant. The crucial change in perspective is that although the belief in the

validity of under-represented constructions is not totally abandoned, it is also

acknowledged that the evidence in texts represents linguistic performance—not

linguistic competence—and may include ungrammatical or less-than-grammati-

xiv

Preface

cal constructions (recognizing that grammaticality is not necessarily a binary

phenomenon). Arriving at an accurate description is thus a delicate exercise in

weighing the relative importance of various observations; the researcher’s intui-

tion and the power of statistical analysis, in the ideal case, work together to pro-

vide the most illuminating results.

Furthermore, this research goes beyond the work of Mackridge in that it pre-

sents the facts for non-finite forms (the gerund and the infinitive), as well as for

the imperative; these verb-forms are only briefly mentioned in his work. In addi-

tion, several subparts to the general problem of weak object pronoun placement,

which had up to now puzzled researchers, are explained in a principled way that

takes into account not only the synchronic data but also the diachronic develop-

ment of such constructions. Another first for this project is the serious considera-

tion given to the possibility that metrical requirements may influence the place-

ment of the pronoun, a critical observation since much of the evidence comes

from poetic texts. Finally, it is shown that, contrary to standard opinion, there is

indeed some dialectal difference regarding this phenomenon.

Besides establishing a well-documented description of the facts of pronoun

placement variation in LMG texts, which could serve as a credible reference for

any future researchers that become interested, this study also provides an as-

sessment of analyses previously proposed as possible explanations for the phe-

nomenon. In doing this, it reaches beyond the narrow realm of explanations pro-

posed strictly for LMG, and examines viable accounts that have been put for-

ward for other languages which display a similar variation in weak object pro-

noun placement, most notably in Old Romance languages (Old French, Old

Spanish, Old Italian). Most of these attempts have been framed within the Prin-

ciples and Parameters program of research into Universal Grammar and depend

crucially on the mechanism of ‘verb movement’.

However, none of these approaches can explain the entire pattern of variation.

The discussion provided here shows clearly that although these analyses can

account for the basic facts, they break down in the face of complex variation, and

either propose ad hoc solutions or diminish the importance of some exceptions to

the predictions that they make. Moreover, the key problematic aspects of the

variation are identified and it is shown that the very nature of the problem is such

that it cannot be explained in the ways promoted so far. On the basis of evidence

from the 17

th

century, where a clear distinction can be seen between pronoun

placement in poetry and pronoun placement in prose, it is argued that the stabil-

ity of the pattern of variation is the result of a stylistic effect which formalized a

pattern of ongoing change. Thus, it is further argued that, although this phe-

nomenon is perplexing from a synchronic perspective, it can be accounted for

diachronically.

The account developed here takes into consideration the fact that weak object

pronouns in the Koiné and Early Medieval Greek period appear rather systemati-

cally after the head of the phrase (noun or verb) and proposes that the change to

Preface

xv

preverbal placement evident in LMG began when a particular preverbal marker

was reinterpreted as the head of the verbal phrase. The spread of the innovative

pattern is explained as a gradual process based upon the linear order relation-

ships between certain elements and the verb. Once preverbal pronoun placement

was established in this core group of contexts, the spread may have halted for a

period (as evidenced in the data from Cyprus) but eventually came to cover all

instances of finite (non-imperative) verb-forms. As a result of this ongoing

change, grammars emerged in which there is no generalization that captures all

the facts about weak object pronoun placement in LMG, an unexpected and sig-

nificant conclusion.

The final chapter presents a discussion of the theoretical implications of this

study. It is argued that the data presented here and their analysis provide further

evidence that the commonly made three-way distinction among ‘word’, ‘clitic’

and ‘affix’ is uninformative and that a bipartite categorization of ‘word’ vs. ‘af-

fix’ (albeit with atypical members in each category) provides better insight into

the subtleties of the morphosyntactic continuum. Furthermore, it is argued that

under this analysis a change from typical to atypical affix is suggested for the

period of Medieval Greek, providing yet another counterexample to the ‘unidi-

rectionality’ hypothesis of recent ‘grammaticalization’ proposals. In addition, it

is demonstrated that the change from postverbal to preverbal pronoun placement

in Later Medieval and Early Modern Greek provides a robust counterexample to

Kroch’s (1989) claim that the contexts involved in syntactic change are abstract.

Finally, the fact that there is no generalization that covers LMG pronoun place-

ment is discussed from the synchronic perspective, and some thoughts are of-

fered about the possibility of writing grammars with less-than-perfect generali-

zations.

A note about the style of the thesis is also in order. The potential readers of

this work may have various interests and, thus, different backgrounds. Some may

read it out of a simple interest in the Greek language, others may approach it as a

study of language change, while others still may be interested in the particulars

of the variationist analysis or the more general morphosyntactic issues. The aim

of the expository style is to be accessible to those with little or no training in the

technical aspects of the analysis, while at the same time providing a detailed

description of the facts for the satisfaction of the more technically oriented read-

ers. The result is a compromise with a number of clarifications which may seem

redundant to some, as well as a level of technical discussion and terminology

that may present difficulty for others; it is my hope, though, that this compro-

mise will prove successful in helping this work reach a wider audience.

Finally, I would like to thank those whose expertise and support have made

this book possible. To professor Brian Joseph, who patiently and diligently read

through several drafts of this study providing references, pointing out problems,

and offering possible solutions, who has led me by the example of his own work,

I will never be able to fully express my gratitude.

xvi

Preface

I would also like to thank professors Don Winford and Carl Pollard—the

members of my dissertation committee—for their helpful comments, as well as

professor Keith Johnson, who helped me better understand the results of the

statistical analysis. In addition, professors Peter Mackridge and Geoffrey Hor-

rocks were more than willing to communicate via e-mail, and provided me with

some very important information and encouragement. An anonymous reviewer

offered some very helpful suggestions. I, of course, am solely responsible for

any errors. Much of this research was conducted under a National Science Foun-

dation fellowship, a Foreign Language and Areal Studies fellowship or The Ohio

State University Presidential fellowship, all of which I appreciate greatly.

Thanks also go to Steve Hartman Keiser and Jennifer Muller for their support

as fellow doctoral candidates, the Changelings reading group for providing a

forum to test new ideas, and the OSU Linguistics Department for promoting

graduate student scholarship in all possible ways. At Simon Fraser University,

the Department of Linguistics and the Chair in Hellenic Studies have been won-

derful in helping me adjust and in encouraging me to pursue my academic goals.

I am indebted to my editor, Jill Lake, for supporting the project, and for her in-

valuable advice about publishing. Finally, I thank my parents and the rest of my

family on both sides of the Atlantic for their emotional and financial support,

especially during my tour of duty with the Hellenic Navy; and Robin, whose

relentless quest for knowledge is a constant source of inspiration.

P. A. P.

xvii

List of Abbreviations

Acc

accusative case

Dat

dative case

DO

direct object

fem

feminine

Fut

future marker

Gen

genitive case

Impf

imperfective past tense

Impv

imperative

Infin

infinitive

IO

indirect object

msc

masculine

neut

neuter

Nom

nominative case

Part

particle

Pass

passive

Past

perfective past tense

Perf Pass Prcle (PPP)

perfect passive participle

pl

plural

Pres

present tense

Pres Act Prcle

present active participle

PS

possessive pronoun

Rel prn

relative pronoun

sg

singular

Subjun

subjunctive marker

WP

weak pronoun

1

1

Introduction

In this chapter, I provide some background information that will help

readers understand the problem of Later Medieval Greek weak object

pronoun placement and its significance for linguistic theory in general.

First, I discuss the reason behind the use of the term ‘weak object pro-

noun’ as opposed to the more common term ‘clitic’, and I give an over-

view of the development of these forms in the history of Greek. In the

second section, I present the details of two previous descriptions of the

phenomenon, and discuss the discrepancies between them, which sug-

gest that a more rigorous evaluation of the phenomenon is needed. Fi-

nally, I discuss why the results of this study have implications that go

beyond Greek, affecting our understanding of such issues as the nature

of clitics and the scope of generalizations in linguistic theory.

Preliminaries

The term ‘weak object pronouns’ is used in this study to refer to a sys-

tem of forms associated with a corresponding system of personal pro-

nouns. These forms are referred to as ‘weak’ because they do not carry

independent stress as the full pronouns do, but are instead always pho-

nologically dependent on an adjacent word which either precedes or

follows them. Forms like these are usually referred to as ‘clitics’ (as is

indeed the case for most of the literature on this specific set of forms),

but that term is avoided here, at least in the description of the phenome-

non, because it is not theory-neutral. Instead, ‘clitic’ has been used in the

literature as a theoretical term, which means that for many readers its use

would lead them to expect a certain pattern of behavior for these ele-

2

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

ments. However, the various uses of the term in the literature are many

times discordant with each other, a fact that has deprived the term of any

meaning and has rendered it a point of confusion instead of illumination

(cf. Zwicky 1994). The term ‘weak pronoun’, on the other hand, does

not carry such theoretical baggage, and appears to be the best term to

employ for the description of the variation. The weak pronouns used in

the corpus of texts as objects of the verb are presented in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1

Forms of the weak pronouns in Later Medieval Greek texts

First

Second

Third (msc–fem–neut)

Singular

Acc

μé

σé

τóν-τν-τó

mE

sE

ton

–tin–to

Gen

μο

σο

το-τς-το

mu

su

tu

–tis–tu

Plural

Acc

μς

σς

τοúς-τíς, τéς, τáς-τá

mas

sas

tus

–tis, tEs, tas–ta

Gen

μς

σς

τν

mas

sas

ton

These are the most commonly found forms. However, in Cypriot and

Cretan texts, one can also find the forms

τσ /tsi/ for feminine genitive

singular and

τσí /tsi/ for the accusative plural in all genders. Also, in

some texts the form

τως /tos/ is found for the genitive plural of the third

person. Dative forms of the pronouns are extremely rare, but a few ex-

amples of the dative case are found in the corpus, mostly

μοι /mi/ (first

person singular) and

σοι /si/ (second person singular). It should also be

noted here that, according to Jannaris (1968: §538, 561), the variants

τíς,

τéς, τáς that one finds in the third person feminine accusative plural

were created by analogy to the feminine accusative plural forms of the

definite article.

Direct objects in Later Medieval Greek usually appear in the accusa-

tive, although there are certain verbs (

νθυμομαι /EnTimumE/ ‘I re-

member’,

διαφéρω /DiafEro/ ‘I differ’, ντρéπομαι /EndrEpomE/ ‘I am

ashamed’) that take a direct object in the genitive case in Ancient and

Hellenistic Greek, and do so to some extent in LMG as well. In Standard

Modern Greek, these verbs take objects in the accusative, which has be-

come the default direct object case, via an accusative-for-genitive

change that had already begun in Medieval times—cf. Jannaris (1968:

Introduction

3

§1242-1299). Indirect objects, which appeared in the dative case in An-

cient Greek appear either in the genitive or the accusative in LMG. (In

Standard Modern Greek only genitive forms are accepted as indirect

objects, although in the north-eastern dialects the accusative is used as

well—cf. Newton 1972, Browning 1983). Thus it is safe to say that in

Later Medieval Greek the forms

μο, σο, το-τς-το, τν are geni-

tive in form, but function as both direct and indirect object (henceforth

DO and IO), while the forms

μé, σé, τóν-τν-τó are accusative in form

but function both as DO and IO also. Finally, the plural form

τους is

accusative in form but functions as a DO, IO or as a possessive pronoun

(PS).

Table 1.2

Forms of the full pronouns in Medieval Greek (after Browning

1983: 62-63)

First

Second

Third (msc–fem–neut)

Singular

Nom

γẃ

σú

ατóς-ατ-ατó

EVo

Esi

aftos, afti, afto

Acc

μé!να"

σé!να" ατóν-ατν-ατó

EmE[na]

EsE[na]

afton

–aftin–afto

Gen

μο

σο

ατο-ατς-ατο

Emu

Esu

aftu

–aftis–aftu

Plural

Nom

μες

σες

ατοí-αταí-ατá

Emis

Esis

afti

–aftE–afta

Acc

μς

σς

ατοúς-ατéς ατáς-ατá

Emas

Esas

aftus

–aftEs aftas–afta

Gen

μν

σν

ατν

Emon

Eson

afton

The full pronouns, which are associated with the forms in Table 1.1

were rare in use, and were employed mainly for emphasis (Jannaris

1968: §525 ff. see also Table 1.2). This system of full personal pronouns

emerged in the Early Medieval Greek stages with the extension of /E/

from the first person singular to the second (

σú /sy/ in Hellenistic

Greek), then to second plural, and finally to first plural (replacing forms

such as

σé /sE/ second singular accusative, #μς /ymas/ second plural

accusative, and

$μς /imas/ first plural accusative—Horrocks 1997:

126-127). In addition, the weak forms of the third person are a creation

belonging entirely to this period; the full forms had alternants without /f/

(e.g.,

%τóν /aton/) from which—it is usually claimed (cf. Browning

4

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

1983, Horrocks 1997)—the weak pronouns developed via aphaeresis of

pretonic initial vowels, a general phonological change of the time. Ac-

cording to Dressler (1966: 57), this hypothesis is untenable because, in

his research of the relevant textual evidence, aphaeresis is common with

prepositions and relative pronouns but not with third person pronouns.

Joseph (in preparation) further points out that aphaeresis with initial /a/

was sporadic and, therefore, could not have played a seminal role in this

development. Instead, he suggests that it was the Koiné and Ancient

Greek pronominal usages of the article

τóν—a carryover from its Ho-

meric usage and Indo-European origin—together with the emergence of

the third person relative pronoun

τó that were the key factors in the de-

velopment of the weak pronoun system for the third person.

Summary of the placement of unstressed elements throughout the

history of Greek

The position of unstressed elements in the clause has been extensively

researched for Ancient Greek (Homeric and Classical), as interest was

generated by the statement of the well-known ‘law’ of Wackernagel

(1892), which stated that, in Indo-European languages, clitic elements

occupied the second position in a clause. Recent research has demon-

strated that in some languages this position can also be defined as the

second daughter in a clause (Halpern 1995). Horrocks (1990) considers

the position of clitic elements in Greek from a diachronic perspective.

He claims that these elements have moved from second position in the

earliest attested Greek (9

th

-6

th

century BC, example 1), to a ‘mixed’

situation in Classical Greek (5

th

-3

rd

century BC), where clitics show both

an affinity for second position and a tendency to attach to the head con-

stituents that select them as arguments (see examples 2 and 3 below).

(1)

καì σφι

ε'δε

(πασι

τéκνα

kai

sphi

EidE

hapasi

tEkna

and

he–Dat pl

see–3sg Past

all–Dat pl

child–Acc pl

‘And (he) saw children (born) for all of them’ (Hdt. I, 30, 4—from Hor-

rocks 1990: 36)

(2)

πυρετοì

παρηκολοúθουν

μοι

συνεχες

pyretoi

pare…kolu…thu…n

moi

sunekhe…s

fevers

follow–3pl Pres

I–Datsg

continual–Nom pl

‘But continual fevers hounded me’ (Dem. 54.11—ibid: 40)

Introduction

5

(3)

καì μοι

λéγε

kai

moi

lege

and

I–Dat sg

tell–2sg Impv

‘And tell me’ (Dem. 37.17—ibid: 40)

During the Koiné and Early Medieval Greek period (2

nd

century BC-

10

th

century AD, cf. example 4) ‘most clitic pronouns follow immedi-

ately after the verbs or nouns that govern them …’ (Horrocks 1990: 44).

In Later Medieval Greek, weak pronoun placement depends on the type

of phrase. In noun-phrases the pronouns are placed after the noun (as in

example 5) almost categorically.

1

In verb-phrases, on the other hand,

they appear mostly before the verb (example 6), yet the number of cases

in which the pronouns appear after the verb is by no means negligible

(example 7).

(4)

το ο+νου

ο.

/γραψéς

μοι

tu… ynu

u

EVrapsEs

my

the wine–Gen sg

which–Gen sg

write–2sg Past

I–Dat sg

‘The wine of which you wrote me’ (P. Oxy. 1220—ibid: 44)

(5)

γυρεúουσι

τà ταíρια

τους

VirEvusi

ta tErja

tus

search–3pl Pres

the mates–DOpl

they–PSpl WP

‘They search for their mates’ (Katalogia, 708)

(6)

πáλε σς

λαλ

palE

sas

lalo

again

you–IOpl WP

say–1sg Pres

‘Again I say to you’ (Moreas, 715)

(7)

πáλιν

λéγω

σας

palin

lEVo

sas

again

say–1sg Pres

you–IOpl WP

‘Again I say to you’ (Digene¤s, 1750)

Finally, in Standard Modern Greek the position of pronouns in verb-

phrases becomes fixed as pronouns appear before the verb (example 8)

except when the verb is of imperative (example 9) or gerund form (ex-

6

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

ample 10). For the sake of consistency, I use the polytonic system of

orthography throughout the book.

(8)

μς

μιλ

mas

mila

we–IOpl WP

talk–3sg Pres

‘S/He is talking to us’

(9)

μíλα

μας

mila

mas

talk–2sg Impv

we–IOpl WP

‘Talk to us!’

(10)

μιλẃντας

μας

milondas

mas

talk–Gerund

we–IOpl WP

‘Talking to us’

Weak object pronoun placement in Later Medieval Greek texts

This section provides an initial description of the facts concerning the

position of weak object pronouns in LMG texts. The first observation

one makes is that the pronouns must appear adjacent to the verb. There

are a few counterexamples to this (example 11) but they are considered

archaic formulations, reflecting the freer position of pronouns in earlier

periods of the language (cf. Mackridge 1993).

(11)

καì μè

1 νος

σéβασεν

kE

mE

o nus

EsEvasEn

and

I–DOsg WP

the mind–Nom sg

put–3sg Past

‘And (my) mind put me’ (Thre¤nos, 1000)

Second, if both the direct and the indirect object of the verb have been

pronominalized, both pronouns appear on the same side of the verb with

the indirect object pronoun preceding the direct object pronoun (see ex-

amples 12 and 13).

(12)

3σàν

σè

τò

%φηγομαι

osan

sE

to

afiVumE

as

you–IOsg WP

it–DOsg WP

narrate–1sg Pres

‘As I am narrating it to you’ (Moreas, 630)

Introduction

7

(13)

λ4

%φηγθη

τς

τα

ola

afiViTi

tis

ta

all–DOpl

narrate–1sg Past

she–IOsg WP

they–DOpl WP

‘All things, I narrated them to her’ (Lybistros, 1847)

The position, however, of the pronouns with respect to the verb (pre-

verbal or postverbal) is not fixed, and at first glance seems to be uncon-

strained. For example, in sentences (14) and (15) the pronouns are pre-

verbal and postverbal respectively despite the fact that the syntactic en-

vironment and even the content of the clauses are the same. The same is

true for examples (6) and (7) in the previous section, and in examples

(12) and (13) just above.

(14)

1 δοùξ

τοùς

%ποδéχθηκεν

o Duks

tus

apoDExTikEn

the duke–Nom sg

they–DOpl WP

receive–3sg Past

‘The duke received them’ (Phlo¤rios, 304)

(15)

κι 1 βασιλεùς

δéχθην

τους

kj o vasilEfs

EDExTin

tus

and the king–Nom sg

receive–3sg Past

they–DOpl WP

‘And the king received them’ (Phlo¤rios, 939)

This pattern of variation does not seem to be affected by the type of

verb-form that is used in the construction. Even if an imperative verb-

form or a participle is used, both preverbal and postverbal pronoun

placement are possible (examples 16 and 17, and 18 and 19 respec-

tively).

(16)

6γíα τ7ν

ε8πé

aVia

tin

ipE

holy

she–DOsg WP

call–Impv sg

‘Call her holy’ (Thre¤nos, 35)

(17)

ε8ς τ7ν καρδíα σου

θéς

το

is tin karDia su

TEs

to

in the heart your

place–Impv sg

it–DOsg WP

‘Place it in your heart’ (Spaneas, 135)

8

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

(18)

καì σον

σè

φυλáττων

kE soon

sE

filaton

and safe–Acc sg

you–DOsg WP

keep–Pres Act Prcle

‘And keeping you safe’ (Glykas, 341)

(19)

τòν

καταφλéξαντá

σε

ton

kataflEksanda

sE

the–Acc sg

burn thoroughly–Pres Act Prcle

you–DOsg WP

‘The one who burnt you thoroughly’ (Achilleid, 1410)

Despite this first impression, however, some strong tendencies for the

placement of these pronouns can be detected. The issue was briefly dis-

cussed by Joseph (1978/1990) and Gemert (1980), while Horrocks

(1990) also dealt with it in his review of clitic placement throughout the

history of Greek. However, it was Rollo (1989) and Mackridge (1993,

1995) who gave the first detailed descriptions of the phenomenon and

who posited the hypothesis that the placement of the pronoun is influ-

enced by the nature of the element which immediately precedes the

verb–pronoun (or pronoun–verb) complex. In fact, Mackridge’s descrip-

tion is accepted as the standard for understanding this phenomenon (cf.

Philippaki-Warburton 1995, Janse 1994 and 1998, Horrocks 1997, Jans-

sen 1998), so in a sense it falls under the rubric of general knowledge

concerning the placement of the pronouns. In the next section I provide

summaries of the descriptions given by Rollo and Mackridge.

Previous descriptions

Rollo (1989)

In this brief paper, Rollo draws comparisons between the ‘use of enclisis

in vulgar Greek’ and the ‘law’ of Tobler-Mussafia, which describes the

pattern of preverbal and postverbal pronoun placement in Old Romance

(Old French, Old Italian, Old Spanish, and their dialectal varieties).

Rollo describes the Late Byzantine pattern thus: The pronoun is placed

after the verb when the immediately preceding element is a subject, a

‘declarative conjunction’ such as

τι /oti/ or διóτι /Dioti/, a verbal argu-

ment whose information is repeated by a ‘pleonastic’ pronoun, an ad-

verb, a verbal argument, the negative marker

ο /u/, or the conjuntion

καí /kE/ meaning ‘also’. The pronoun is placed preverbally when the

immediately preceding element is a ‘subordinating conjunction’, the

Introduction

9

‘particle’

νá /na/, the hortative ς /as/, any of the relative and interroga-

tive pronouns, or negatives other than

ο. These descriptions are stated

in absolute terms although Rollo offers several cases for which there are

exceptions, most notably, for preceding subjects, complements and ad-

verbs where one finds some examples of preverbal pronoun placement.

Mackridge (1993, 1995)

Working without knowledge of Rollo’s research, Mackridge (1993,

1995) presents a much more detailed look at weak pronoun (which he

calls ‘clitic pronoun’) placement, mainly in the Digene¤s text, although he

discusses a few examples from other texts as well. He successfully

shows that this position is not a ‘free for all’, as was previously assumed

by editors who would change the position of a weak pronoun in order to

satisfy metrical requirements. Instead, he demonstrates that there is a

strong correspondence between the nature of the element that immedi-

ately precedes the verb–pronoun complex and the pronoun’s position.

He identifies these correspondences as lists of environments, which enter

into rule formulations as parameters determining the placement of the

pronoun. These rules describe a scale of pronoun placement, which

ranges from obligatory postverbal order to obligatory preverbal order.

The environments that he associates with ‘more or less’ obligatory

postverbal pronoun placement are: a) when the verb is in clause-initial

position, or b) if the verb is immediately preceded by one of the follow-

ing elements: a coordinating conjunction (

καí /kE/ ‘and’, %λλá /ala/, μá

/ma/,

%μ /ami/ ‘but’, οδé /uDE/, μηδé /miDE/ ‘neither’, 9 /i/ ‘or’), a

reduplicated object,

2

the negative marker

ο(κ) /uk/

3

‘not’, the comple-

mentizer

τι /oti/ ‘that’, the causal conjunction διóτι /Dioti/ ‘because’,

and the conditional conjunction

ε8 /i/ ‘if’.

Next, Mackridge states that when the verb complex is immediately

preceded by a temporal adverb, the placement of the pronoun can vary

freely between preverbal and postverbal position. The position of the

pronoun is more likely to be preverbal when the preceding element is a

subject. Preceding ‘semantically emphasized’ constituents (such as an

object, a non-temporal adverb or a predicative argument) are even more

strongly associated with preverbal pronoun placement. Mackridge calls

this ordering ‘almost obligatory’. Finally, he describes the position of the

pronoun as ‘more or less obligatorily’ preverbal in those cases where the

complex is immediately preceded by any one of the following: the sub-

junctive marker

νá /na/, the hortative particle ς /as/, the future marker

θá /Ta/, the negative markers μ /mi/, μηδéν /miDEn/, δéν /DEn/, οδéν

10

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

/uDEn/ ‘not’, the interrogative pronouns and adverbs (

τíς /tis/, ποιóς

/pios/ ‘who’,

+ντα /inda/ ‘what’, πς /pos/ ‘how’, διατí/γιατí /Djati/

/jati/ ‘why’,

πο /pu/ ‘where’, πóσος /posos/ ‘how much’), the relative

pronouns (

που /opu/, 1ποú /opu/, ποú /pu/ ‘which’, ς /os/, τóν /ton/

‘who’

,σος /osos/ ‘which amount’, στις/ποιος/ε+τις /ostis/ /opjos/

/itis/ ‘whoever’), the complementizer

πẃς /pos/ ‘that’, the temporal and

comparative conjunctions (

πεí /Epi/, ποτε /opotE/, ταν/ντε/ντας

/otan/ /ondE/ /ondas/ all meaning ‘when’,

προτο /protu/ ‘before’, πρíν

/prin/ ‘before’,

%φο/%φóτου/%φẃν /afu/ /afotu/ /afon/ ‘since’, (μα

/ama/ ‘when’,

3ς /os/, 3σáν /osan/, σáν /san/ all meaning ‘when, as’

καθẃς /kaTos/ ‘as’), the final conjunction να /ina/ ‘in order to, to’, and

the conditional conjunctions

ν /an/, áν /Ean/ ‘if’. Figure 1.1 below

provides a diagrammatic summary of Mackridge’s description of the

variation.

preverbal

almost preverbal

normally preverbal

free variation

postverbal

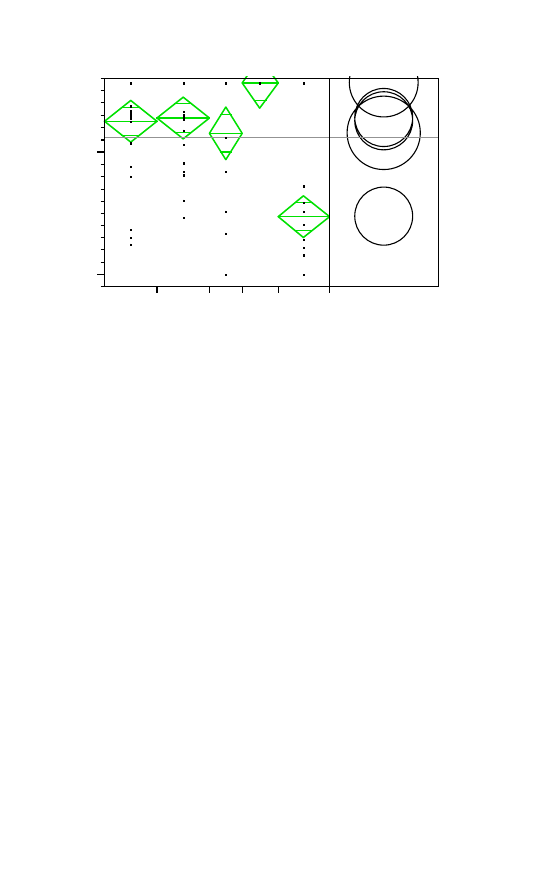

Figure 1.1

Scale of weak object pronoun placement in LMG according to

Mackridge (1993)

Obviously, Mackridge’s description is much more detailed and intri-

cate than that of Rollo, which would lead us to believe that it is also

more accurate. On the other hand, since Mackridge mostly concentrates

on one text (the epic of Digene¤s) and Rollo utilizes examples from many

different texts, the discrepancies between the two descriptions may be

the result of differing databases. This, on its own, emphasizes the need

for a quantitative study of the phenomenon which will include as many

of the available texts, and will draw tokens from each text in as repre-

Introduction

11

sentative a way as possible. Another aspect of Mackridge’s description

that invites the use of a quantificational analysis is that he recognizes

differences in the effect that each environment has on pronoun place-

ment. For example, preverbal pronouns are ‘almost obligatory’ when the

complex is preceded by an object, but such placement is only ‘normal’

when the complex is preceded by a subject. But what exactly do these

terms mean? Certainly, we will gain greater insight into the pattern of

variation if we are able to quantify these rankings.

Whether or not these differences are confirmed, the emerging pattern

of variation presents us with a linguistic phenomenon that requires ex-

planation. What are the structural reasons for this variation? According

to Mackridge (1993: 329), the explanation is two-fold. Part of the place-

ment pattern can be explained in ‘purely syntactical terms’: ‘there are

certain words or classes of words that are followed by V + P … while

there are others that are followed by P + V.’ But how can a descriptive

list such as the one that he provides be a ‘purely syntactical’ explana-

tion? One wonders whether it is possible to state a generalization that

covers all these separate words and word classes in a principled way,

instead of simply listing them. Most linguists would expect the former,

but if the latter proves true, then that in itself is interesting and impor-

tant. Even if it is so, however, one should still try to explain why it is this

particular set of words that is associated with preverbal pronoun place-

ment, and not another. In essence, Mackridge’s rules are mostly stipula-

tive, and do not help us understand the variation.

The other part of the placement pattern is explained as ‘cases where

the pronoun precedes the verb because some constituent is placed before

the verb-phrase for reasons of emphasis.’ Indeed, Mackridge attributes

great significance to semantically emphasized elements ‘attracting’ the

pronouns to their position. In fact, he maintains that the distinction

among the classes of elements seen in Figure 1.1 is based on the fact that

preverbal objects are more emphatic than preverbal subjects which in

turn are more emphatic than preverbal temporal adverbs. However, he

does not go into detail about the nature of emphasis or the mechanism of

‘attraction’. Given the weight that both of these terms are given in the

exposition it is unfortunate that they are not explained more fully.

These questions show that despite Mackridge’s contribution, the phe-

nomenon of weak object pronoun placement variation in Later Medieval

Greek has not been thoroughly explained. At most, it has been ade-

quately described. In the subsequent chapters, I will propose a method-

12

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

ology to be employed in the investigation of the variation, and then seek

empirical confirmation of Mackridge’s description. Once the facts have

been disclosed in detail, I will attempt to explain the pattern of variation.

Contribution of the study

The effort to arrive at a better understanding of weak object pronoun

placement in Later Medieval Greek has implications that go beyond

solving a puzzle for a brief period in the history of a single language.

Rather, the results of this study expand our knowledge in several ways

which impact the field of Greek Linguistics, research on clitics, as well

as our views about the nature of generalizations.

Although Greek is a language that has been researched in depth, our

knowledge of Medieval Greek is particularly limited, especially since

there is a genuine lack of texts or other documents that record the ver-

nacular of the time. This is indeed unfortunate because many of the more

interesting constructions in Modern Greek—such as the replacement of

infinitival complementation by finite subordinate clauses, the use of a

periphrastic future and perfect, and the placement of weak pronouns (as

verbal and nominal arguments)—have their origin, or become estab-

lished in Medieval Greek. As will be demonstrated in a later chapter,

there is considerable amount of interaction among these constructions,

and the topic at hand—weak object pronoun placement—is the least

understood of the three.

4

Apart from providing an important missing

piece of Medieval Greek syntax, an account of this phenomenon also

plays a major role in understanding the eventual development of Greek

dialects, which are differentiated on the basis of pronoun position, as

was clearly demonstrated in Condoravdi and Kiparsky (2001). Although

I disagree with the specifics of their proposal for LMG pronoun place-

ment (cf. Chapter 6), I concur that these facts are pivotal to our under-

standing of the eventual division of Greek into dialects with (mostly)

preverbal pronoun placement on the one hand, and dialects with postver-

bal pronouns on the other.

The results of this study also contribute to the general knowledge

about clitics. Despite the vast amount of research that has been con-

ducted on these nefarious elements in the past 110 years, it seems that

the amount of variation within this category (if indeed it is a separate

category) is inexhaustible. Thus, after the initial classification of clitics

into simple clitics, special clitics, and bound words by Zwicky (1977),

subsequent research proliferated the different types of elements that be-

Introduction

13

long to each of these classes, especially for special clitics. Halpern

(1998), for example, subdivides special clitics into second-position

clitics which must appear second in a domain that is differently deter-

mined for individual languages, and verbal clitics, which must appear

adjacent to a verb. Moreover, he separates this latter group into verbal

clitics, which behave as inflectional affixes (these have a fixed position

with relation to the verb), and verbal clitics which resemble second-po-

sition clitics in that they sometimes appear before the verb and some-

times after it, depending on the nature of the element that precedes them.

At first glance, this seems to be the exact same situation that we have

in LMG, except that, as will be argued later, LMG weak pronouns are

always phonologically attached to the verb, either as enclitics or pro-

clitics, whereas the ‘Tobler-Mussafia Law clitics’ have been character-

ized as enclitics. These elements thus present us with a new case of spe-

cial clitic, and a detailed investigation of their behavior undoubtedly will

have significant theoretical implications. For example, Condoravdi and

Kiparsky’s (2001) typological study of clitic pronouns in Post-Hellenis-

tic Greek brought them to the conclusion that, on the one hand, the dis-

tinction between clitics and affixes is not a gradient one (so Janse 1998),

but, on the other, the bipartite classification of X

max

and X

0

clitics pro-

posed by Halpern and Fontana (1994) is not sufficient either. Instead

they argue for a three-way classification which includes X

max

clitics, X

0

lexical clitics but also X

0

syntactic clitics. The detailed investigation of

LMG weak pronouns presented here will provide the necessary data to

assess this new proposal. It is interesting to note here that while Zwicky

(1977) claims that a typology of clitics provides insight into historical

change, studies such as the ones cited above and the one presented in

this book prove that examinations of the historical development of clitics

are equally informative about the nature of these elements.

Perhaps the most significant issue addressed by the results of this

study is the role of generalizations in linguistic theory. It is not an exag-

geration to state that discovering the generalizations that govern linguis-

tic knowledge has been the holy grail of linguistics. In using this meta-

phor, I am aware of and wish to allude to all its implications, since there

has not yet been a description of a language that depends solely on gen-

eralizations. Instead, many patterns have to be specified for particular

classes of lexemes or even individual ones. Nonetheless, linguists still

hold on to the belief that these generalizations exist, that we just lack the

theoretical tools to state them, and they are optimistic that the formula-

14

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

tion of such a theory cannot be too far away. In this light, the results of

this study are surprising since they lead to the conclusion that no gener-

alization can capture the entirety of the phenomenon. As will be demon-

strated, this failure to generalize over the data is brought about by the

fact that the position of the pronoun in Later Medieval Greek depends on

the surface characteristics of the element that immediately precedes the

verb and not the structural ones. In fact, many of the elements that affect

the placement of the pronoun in a similar way do not fall under any natu-

ral classification, while others, which would be expected to pattern in the

same way, do not. Consequently, this study joins a number of other re-

search efforts that have arrived at less-than-perfect generalizations and

explores the alternative ways in which we can model linguistic knowl-

edge.

Introduction

15

1

When the noun is preceded by an adjective the pronoun may appear after the

adjective and before the noun, a pattern that Horrocks views as a residual of the

‘clitic second’ tendency transferred to the phrasal level.

2

Mackridge’s exact formulation is ‘when the verb-phrase is preceded by an

object with the same referent as that of the clitic pronoun (i.e., when the pronoun

is resumptive or doubling).’ However, by verb-phrase Mackridge means the

verb-pronoun complex, not the VP of generative syntax. It must also be noted

that, according to Haberland and van der Auwera (1993) doubling and

resumptive clitics (pronouns) are not the same.

They reserve the term

resumptive for those pronouns that appear in relativized clauses representing the

antecedent, and use the term doubling for the situation that Mackridge describes.

3

The velar stop is retained only before vowels and becomes a velar fricative if in

Classical Greek the following vowel was aspirated. Later Medieval Greek

orthography still reflects this change (

ουηχ ευΗριςσκω τον, Achilleid 1616)

even though the vowels are no longer aspirated.

4

For the loss of the infinitive see Joseph (1983a), while for the future and perfect

periphrases see Horrocks (1997) and Joseph and Pappas (2002).

15

2

Methodology

This chapter deals with methodological issues concerning the investiga-

tion of morphosyntactic phenomena when the only available evidence

comes to us from texts. It is argued that even though such data constitute

observations of performance, a statistical analysis can allow one to de-

duce linguistic competence from them if a truly representative sample of

texts is used. At the same time, it is cautioned that in cases such as this

where the body of texts has been arbitrarily culled by the passage of

time, one should pay careful attention even to singular occurrences. An-

other major methodological concern addressed in this chapter is whether

a variationist analysis of morphosyntactic phenomena is even possible as

well as the definition of the particular linguistic variable that is investi-

gated in this study. A detailed list of the works used to complile the da-

tabase is also presented.

Linguistic usage vs. linguistic competence

Analyzing syntactic phenomena of an earlier stage of a language where

the evidence comes overwhelmingly from documents such as texts pre-

sents a challenge that should not be underestimated. Texts give us exam-

ples of language usage, whereas the prevalent way of analyzing syntactic

structures is to test our intuitions (Chomsky 1965, 1995), especially

about ungrammatical sentences, which are rarely available from texts in

the typical case. It would seem then impossible to work in historical

syntax within the generative framework, without finding some method

of deducing competence by observing performance. Sometimes we are

helped in this respect by grammarians of the period who describe the

16

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

language of their time. For example, Browning (1983: 52-53) reports on

the observations of the Atticist lexicographer Phrynichus and his com-

ments on the ‘errors’ of his students who were using Koiné constructions

and vocabulary instead of the Classical ones. In Early Modern Greek we

even find grammars of the spoken language (e.g., the 1555 grammar of

Sofianos (Papadopoulos 1977), or the early 17

th

century grammars of

Germano (1622, in Pernot 1907) and Portius (1638, in Meyer 1889)).

However, there are no contemporary descriptions of the Later Medieval

Greek (i.e., before 1550) stage of the language (Joseph 1978/1990: 4).

So this is a case where only the texts themselves can provide information

about the grammar.

However, deducing grammaticality judgements from textual evidence

is not an easy task. As Lightfoot (1979: 5) has stated:

Usually [in diachronic syntax] one has no knowledge of ungrammati-

cal ‘sentences’, except in the rare instances where a contemporary

grammarian may report that certain forms and constructions are not

used; one is thus in the position of a child acquiring its first language,

who hears sentences being uttered but does not know whether certain

other hypothetical sentences are not uttered because they would be

grammatically deviant in some principled way or because they have

not occurred in his experience as a function of chance.

Lightfoot offers two methodological suggestions that may help over-

come this inherent problem in the collection of data for diachronic syn-

tax. The first one is that one must examine as many texts as possible

covering as many genres as possible, in order to make sure that what we

are describing is not the grammar of a particular individual or of a single

literary style. Lightfoot’s second suggestion is that the ‘… linguist [must

be] prepared to use his own intuitions where obvious generalizations can

be made’ (1979: 6). So, even in cases where certain constructions are not

attested, we should not immediately assume that they are ungrammatical,

but question ourselves if their non-occurrence is simply a matter of

chance. One has to be very cautious since not all intuitions about earlier

stages will be the same, or even valid.

Another method to remedy the paucity of negative data in diachronic

syntax is offered by Joseph (1978/1990: 2): ‘when there is sufficient

attestation, textual evidence allows for the use of statistical counts in

making judgements of acceptability. This is especially so when a dia-

Methodology

17

chronic change is reflected in a significant variation in the ratio of the

use of one surface configuration to another.’ This is precisely the goal of

variationist studies, a program spear-headed by Labov (1963) in order to

understand how sociolinguistic variation may lead to linguistic change.

The methodology of this program was originally employed in studies of

phonological and morphophonological variation, and with the work of

Kroch (1982/1989) it has also been employed in understanding syntactic

variation and syntactic change. The basic assumption as stated by Taylor

(1994: 19) is that there is ‘… a fairly direct connection between gram-

mar and usage such that the organization of the grammar is reflected in

the patterns of usage.’ The word ‘reflected’ is used because, while gen-

eral usage will follow the syntactic rules of the grammar, there will also

be tokens of usage that do not. One has to ask then, what the import of

such non-conforming examples is, especially when their relative num-

bers are small.

The first and most obvious answer would be that we do not expect the

grammars that we construct for past stages of a language to have the

same descriptive adequacy as contemporary grammars should have. Af-

ter all, we are examining data of language usage, not of linguistic intui-

tions. Thus, we can explain rare counterexamples to otherwise regular

patterns as simple slips of attention. There is also, however, a parallel

that can be drawn between diachronic and synchronic syntactic studies if

we consider the possibility that the deviations come from an area of the

grammar that is undergoing change (i.e., from postverbal placement of

the pronoun to preverbal placement). It is possible that the ongoing

change creates a certain level of uncertainty within the speaker/writer.

Linguistic intuitions of uncertainty are not uncommon in synchronic

syntax either. In fact there is ample evidence concerning ‘question

mark’

5

judgements of grammaticality where there is hesitation about the

well-formedness of a construction or maybe even disagreement about the

well-formedness of the construction between different speakers. In gen-

eral, if such counterexamples in the texts are rare and do not form sig-

nificant patterns, they can be set aside without much consideration, es-

sentially being treated as curiosities, much as ‘question mark’ construc-

tions are treated in synchronic syntax.

Admittedly, it is much harder to dismiss evidence that turns up in his-

torical research, because we are always operating under the insecurity

that there are other, linguistically non-related reasons for the rarity of a

pattern in a corpus. More important, perhaps, is the recognition that, ex-

18

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

cept in rare cases, everything that occurs in a text is a possible utterance

(or construction) and thus cannot simply be dismissed. As a result, the

historical syntactician is obliged to look at every rare pattern carefully,

and to decide whether or not it should be accounted for as part of the

grammar.

Compiling a corpus of texts

The preceding remarks are general in nature, issues that would be en-

countered in any historical text-based syntactic study. However, in Later

Medieval Greek (indeed, in Medieval Greek in general) we are faced

with an additional problem: the influence of the puristic model of Greek

that many writers adopted in Post-Classical times and which has been

influential in the development of the language up until now. As Joseph

(1978/1990: 5) writes:

Because of the overwhelming cultural influence of Classical Greece,

Greek writers in Post-Classical times felt compelled to emulate the

language and style of the Classical writers. This Atticizing drive re-

sulted in the writing of many Medieval texts, in what can be called a

‘learned’ style, which were virtually indistinguishable linguistically

from the Greek of over 1,000 years before their time.

Another potential source of influence on the language of these texts

came from the Romance languages, especially in the period after the

conquest of Constantinople by the crusaders in 1204, and the establish-

ment of Romance-speaking (mainly Italian and French) feudal lords in

Byzantine territory. This concern is mostly voiced about the language of

romantic poetry where many of the themes are common to both the Byz-

antine and the Romance literature and sometimes the origin of a poem

may be unclear. Some poems may be Romance originals translated into

Greek, raising the possibility that the language of these texts may not

represent the spoken Greek of the time but, instead, show the effects of

translation syntax.

It can also be problematic to place these texts chronologically. As I

assume is usually the case with textual evidence from the Middle Ages,

there exist several manuscript traditions and it is not always easy to as-

certain which manuscript is closest to the original writing or the oral

tradition upon which a particular work is based. This problem is com-

pounded by the liberal copying process (so say both Browning 1983 and

Methodology

19

Horrocks 1997) of Byzantine scribes who felt free to ‘emend’ the texts

they were copying according to their idiom. Joseph (2000) discusses a

similar problem concerning three infinitival constructions of Medieval

Greek, the circumstantial infinitive, the periphrastic future with

θéλω

/thElo/ ‘I want’ plus infinitive and the periphrastic perfect with

/χω /Exo/

‘I have’ plus infinitive whose authenticity has been questioned by other

scholars. Even though Joseph shows that these constructions have a

‘good claim to legitimacy and authenticity’, it is evident that painstaking

philological work is required in the collection of data from Medieval

Greek in order to determine which texts can be used as valid representa-

tives of the spoken language of the time. In the following list, I provide

the names of the texts that make up the database as well as the relevant

philological information about them that I have compiled from the works

of Beck (1993), Browning (1983) and Horrocks (1997), and Joseph

(1978/1990); the texts are listed in the rough chronological order of their

(estimated) composition. If a text was not included in the database in its

entirety, the specific lines examined are indicated in parentheses.

Basileios Digene¤s Akrite¤s. This is an epic poem recounting the ex-

ploits of the hero Digene¤s, a legendary border defender (Akrite¤s) of the

empire, who was the son of a Muslim father and a Christian mother (Di-

gene¤s: Two-race). Despite the fact that many aspects of the manuscript

traditions are disputed, and although there are several questions about

the ultimate source and language of the original, it is generally acknowl-

edged that the language of the manuscript of Escorial (15

th

century) is

the earliest extended version of spoken Greek of the Later Medieval pe-

riod which reflects linguistic behavior of the 11

th

or even 10

th

century.

Pto¤khoprodromika. A collection of satirical poems written in the 12

th

century, attributed to Theo¤doros Prodromos, a member of the Byzantine

court who had fallen out of favor (Pto¤kho/prodromos: Poor/Prodromos).

Not everyone agrees that all the poems have the same author. There is

also some dispute as to whether another short poem, entitled Philosophia

tou Krasopateros, which displays many more modern characteristics

should be included in this collection. I did not include it in the database.

Spaneas. Another poem of disputed authorship, in which a father ad-

vises his son. Most scholars agree that it comes to us from the 12

th

or

13

th

century.

Glykas. Best known for his Chronography, a work in the Koiné,

Glykas also penned this largely vernacular poem while he was impris-

oned by the emperor Manuel 1

st

(13

th

century).

20

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

Poulologos. An allegorical poem of unknown authorship about a feast

of different birds. Most scholars agree that it has its origin in a Byzantine

court (perhaps from Nicæa) and that it was composed in the 14

th

century.

Physiologos. A list of animal descriptions written in the 14

th

century

based on a much larger work written in the Hellenistic Koiné.

Die¤ge¤sis Paidiophrastos (lines 1-121, 740-1082). Another poem with

anthropomorphized animals belonging to the middle of the 14

th

century.

Die¤ge¤sis Akhilleo¤s (Achilleid). Despite the name of its protagonist

(Achilles) this work has nothing in common with the Iliad. Rather, its

motif is the same as all other romances of the period. It was probably

penned in the 14

th

century.

Khronikon tou Moreo¤s (lines 125-1625). A chronicle of the conquest

of the Moreas province of the Peloponnese by the Franks, attributed to a

Greek-speaking descendant of the conquerors. The version used in this

study was composed, according to most scholars, near the end of the 13

th

century.

Historia tou Belisariou. A poem based on the exploits of a real-life

Byzantine general. Several different manuscripts of this work exist; I

chose the version given by Bakker and Gemert (1988) as the closest ap-

proximation to the original, which was probably composed at the begin-

ning of the 15

th

century.

Kallimakhos kai Khrysorrhoe¤ (lines 500-2000). A story in the chival-

ric tradition written in verse sometime in the 14

th

century. Although it

bears similarities with similar works from the western romance tradition,

scholars are certain that this poem has its ultimate origin in the Byzan-

tine literary tradition.

Lybistros kai Rhodamne¤, (lines 1500-3000). Similar to Kallimakhos

kai Khrysorrhoe¤.

Die¤ge¤sis Apollo¤niou. This romantic poem is also considered a work of

the 14

th

century. Unlike the two previous ones, however, it is thought to

be a translation of an Italian poem that occurred in the western territories

of the Byzantine empire.

Phlo¤rios kai Platziaphlore¤ (lines 1-1500). A romantic poem similar to

Die¤ge¤sis Apollo¤niou.

Thre¤nos Ko¤nstantinoupoleo¤s. An elegy for the fall of Constantinople

composed around that time (1453) by someone living in the area.

Thanatikon te¤s Rhodou. Another elegy recounting the plague that be-

fell the city of Rhodes (1499), composed by native poet Geo¤rgillas

shortly after the event of the plague.

Methodology

21

Katalogia. A collection of love songs from the island of Rhodes, com-

piled before the end of the 15

th

century.

Phalieros. The database includes two works of Marinos Phalieros, a

member of the Venetian aristocracy of Crete. They were both written

during the first half of the 15

th

century.

Spanos. A quite explicit satire of a Byzantine liturgy, composed during

the 15

th

century. It contains many archaistic elements (which is to be

expected because the ecclesiastical language was highly stylized),

though the pronoun placement patterns seem unaffected.

Homilia tou nekrou basilia. A poem in the long tradition of encounters

with the dead, Homilia recounts the story of a traveler happening upon

the remains of a dead king, who warns him about the ephemeral nature

of earthly gains. It was probably composed in Crete during the second

half of the 15

th

century.

Apokopos. Another Cretan poem of the 15

th

century recounting a trip

to Hades. This time, though, the reader is advised to enjoy life, for the

dead are quickly forgotten.

Khroniko to¤n Tokko¤n (lines 500-2000). A chronicle about the Tocco

dynasty of Epeiros (North-Western Greece). Written around the begin-

ning of the 15

th

century.

Die¤ge¤sis tou Aleksandrou (lines 1-1500). The rhymed version of the

Alexander poem, most likely composed in Zakynthos around the begin-

ning of the 16

th

century.

Depharanas, Tribo¤le¤s, Gioustos. All three of these poets are from the

Heptanese region (Gioustos and Depharanas from Zakynthos, Tribo¤le¤s

from Kerkyra (Corfu)). Their works date from the beginning of the 16

th

century.

Aito¤los. This is a poem from the middle of the 16

th

century, which

does not have a title. According to Bànescu the poem’s composer hails

from Aito¤lia (western Greece), hence the listing.

These are the texts that constitute the database for investigating the

position of weak pronouns in Later Medieval Greek and Early Modern

Greek. It is obvious that these texts span a rather large time period

(roughly five centuries) and were written in different parts of the empire.

Most scholars, however, maintain that there is little differentiation within

this body of texts, either according to time-period, or by geographical

origin (cf. Browing 1983, Joseph 1978/1990, Mackridge 1993, Horrocks

1997), especially with respect to the variation of pronoun placement.

More significantly, the information about the authors of these texts is

22

Variation and Morphosyntactic Change in Greek

lacking in most cases, and one has to rely on the educated guesses of

philologists. For these reasons the investigation will begin by treating the

texts as a single group, as Mackridge himself did.

Unlike Mackridge, however, I have not included the Cypriot texts in

this group, for, as I will show in Chapter 5, they differ substantially from

the other texts with respect to pronoun placement. There are three Cyp-

riot texts from this period. The first one, Assizes, is a text of laws of the

period, written in the middle of the 14

th

century. The other two,

Ekse¤ge¤sis te¤s Glykeias Kho¤ras Kyprou by Makhairas (15

th

century, sec-

tions 175-200 and 300-330), and Die¤ge¤sis Khronikas Kyprou by Bous-

tro¤nios (16

th

century, sections 75-135), are chronicles of events taking

place in Cyprus. Boustro¤nios’ chronicle starts where Makhairas’ ends.

Unfortunately, I only had access to small excerpts from the Assizes, so

only the two chronicles were consulted in this study.

For the examination of weak object pronoun placement in Early Mod-

ern Greek, the standard editions of the poems of Ero¤phile¤ (lines 1-500),

Thysia tou Abraam (lines 1-500), and Boskopoula were chosen from the

works of the Cretan Rennaisance (17

th

century). In addition, prose texts

from Baleta’s Anthologia te¤s De¤motike¤s Pezografias (Anthology of de-

motic prose, pages 113-256), also written in the 17

th

century, were ex-

amined. These excerpts are usually two or three pages long, and come

from various places of the then Greek-speaking world. Finally, for Early

and Middle Medieval Greek, Maas’ (1912) compilation of the rhythmi-

cal Acclamations were consulted, since they are believed to be the clos-

est approximation of the vernacular of the time (6

th

-10

th

century).

Accountability and the linguistic variable in morphosyntactic

research

The variationist framework employed in this research was developed as