12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 1 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

Subject

Key-Topics

DOI:

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change

ALICE C. HARRIS

Linguistics

»

Historical Linguistics

syntax

10.1111/b.9781405127479.2004.00018.x

In this chapter I seek to characterize briefly an approach to universals of diachronic syntax that depends

crucially upon a rich cross-linguistic corpus.

1

I do this by stating some of the aims of the study (section 1),

briefly describing differences between the approach taken here and others (section 2), and describing the

method followed (section 3). Section 4 sets out an example from Georgian, which helps with the

characterization of reanalysis and actualization (section 5). Section 6 is devoted to an extended example,

which illustrates the application of this method in one area of syntax, the change from biclausal to

monoclausal structure.

1 Goals of the Study of Syntactic Change

Different approaches to language can be distinguished in part in terms of their goals. Among my goals in

studying syntactic change are the following:

i to characterize syntactic change accurately;

ii to identify and characterize universals of syntactic change;

iii to explain syntactic change;

iv to build a theory of change.

Characterizing syntactic change includes a consideration of general questions, such as: Is syntactic change

regular? Is it directional? It includes a description of the mechanisms of syntactic change. In addition, a

complete characterization comprises a description of the changes that actually occur in natural languages.

HC applies inductive methods in searching for universals of change, seeking the general rule on the basis of

specific cases. Examining instances of the “same” change in diverse languages, we can focus on elements of

that change that are the same or similar and eliminate from consideration elements that vary from one

language to another. This method is described in greater detail in section 3.

There are many kinds of explanation, and among the most effective is demonstration of a relationship

between the familiar and that which is (or was) unfamiliar. It may be that the better way to view goal (iii) is

that we seek simply to understand all aspects of syntactic change, and we include here attention to the

causes of change.

2

It may be too early to state a general theory of change, but it is at least possible in our current state of

understanding to distinguish language-particular from universal aspects of syntactic change, to state

generalizations about classes of change, and to identify the kinds of syntactic change that are possible in

natural language and, at least by implication, the kinds that are not.

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 2 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

natural language and, at least by implication, the kinds that are not.

2 Approaches to the Characterization and Explanation of Syntactic Change

Logically there are two basic ways to approach the study of change. One approach begins with a theory and

examines what that theory tells us about what we should expect to find in language change. The best-

known theory-driven approach of this sort is found in Lightfoot (1979, 1991). What have we learned from

these studies? The centerpiece of Lightfoot (1979) was the Transparency Principle, “a rather imprecise,

intuitive idea about limits on a child's ability to abduce complex grammars” (Lightfoot 1981: 358), which was

proposed to characterize the point at which change takes place. In Lightfoot (1991) we find the notion of

“degree-Ø learnability,” likewise a hypothesis about the way a child learns language. But the hypothesis of

imperfect learning cannot account for all syntactic change, since many diverse languages retain the source

construction beside the reanalyzed structure (see Harris and Campbell 1996). And if we are looking for a set

of general principles that limit syntactic change or statements of universals of syntactic change, we come

away from Lightfoot (1979, 1991) empty-handed. Lightfoot adroitly avoids commiting to anything of

substance by arguing that there are no constraints on change other than the theory of Universal Grammar.

Naturally, Universal Grammar sets upper limits on change, but the doctrine that it adequately characterizes

syntactic change would imply, for example, that it is possible for any sanctioned construction to become any

other, without limit. Even if there were no limits on syntactic change other than those imposed by Universal

Grammar, one could still state valid generalizations. Yet we come away from these studies with no

universals, with no constraints, with no hypotheses that can be tested. It is my position that the theory of

Universal Grammar is as yet incompletely stated, and that studies of universal properties of syntactic change

will contribute significantly to developing it further.

3

A second approach is data-driven and seeks to develop generalizations based on the corpus of actual

changes. Many studies of the diachronic syntax of individual languages or individual families, including my

own studies (e.g., 1985, 1991, 1994, 1995), are intended in this spirit as contributions to the general

corpus. There is a wealth of data available on attested changes (i.e., changes during the historical period) in

some languages of the Indo-European, Semitic, Uralic, Kartvelian, Dravidian, and Sino-Tibetan families,

among others. Even some languages outside these families are attested for a long enough period that

syntactic change can be carefully tracked; for example, a comparison of Classical Nahuatl with those of the

modern Nahuatl dialects known to be its descendants provides attestation of change. Among the problems

for the would-be constructor of theories is that it requires knowledge of the language to analyze the texts,

to read much of the secondary literature, and to avoid the pitfalls of incomplete understanding of the

synchronic systems.

Among data-driven approaches, some limit themselves to particular aspects of change. For example, while

we have learned a great deal from recent work in grammaticalization, that approach is primarily centered on

features of words and morphemes and on the transition from the former to the latter. For example, in a

grammaticalization approach to the case study in section 4 below, emphasis would be on the transition from

verb to auxiliary; in contrast, it is my aim to treat the structural change involved, as well as the verb-to-aux

transition. Similarly, recent functionalist studies contribute to our understanding of certain types of change,

but they provide no general characteristics of change. Finally, several important recent papers have provided

valuable studies of the gradual implementation of particular changes in syntax (e.g., Kroch 1989a; Fischer

and van der Leek 1987; Naro 1981; Naro and Lemle 1976). What these studies do not identify clearly is the

mechanism that gets these processes started and constraints on that mechanism.

4

In our work, we seek to

provide an overall framework in which contributions to various individual aspects of syntactic change can be

correlated with others to make sense of diachronic syntax.

3 Cross-Linguistic Perspective

The method of cross-linguistic comparison developed in HC is part of an overall framework for the

description and explanation of data from a wide variety of languages, and on this basis we develop a theory

of morphosyntactic change. The method begins by comparing the “same” changes in very different

languages. Characteristics that are found in language after language are candidates for universals, and from

them we develop hypotheses which can then be tested against additional data. We reason that

characteristics that do not occur in all instances must be language-specific. This method begins by

comparing changes that are as closely matched as possible for input structure, output structure, and

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 3 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

comparing changes that are as closely matched as possible for input structure, output structure, and

meaning-function. Generalizations are made at this level, and the comparison proceeds to a higher level,

where the previous set of changes are compared with other sets which have already been compared

internally. Again generalizations are drawn, and, if appropriate, the comparison continues, throwing an ever-

wider net.

An example which is elaborated below in section 6 is the simplification of biclausal structures into

monoclausal ones. The changes from independent modal verbs to modal auxiliaries in different languages

are compared, and conclusions are drawn. At a second level, these results are compared with conclusions

based on comparisons of similar changes involving other independent verbs, such as ‘have, hold, keep’ used

in perfects, and ‘be’ in progressives. At a third level, other transitions from biclausal to monoclausal

structure (i.e., not involving creation of auxiliaries) are compared with the results previously obtained.

A second example, not included below, involves the operation of word order change. We found typological

approaches limiting, and we look instead at the changes that actually occur. At a first level we compare

verbs and auxiliaries that are not adjacent in the input to the change and are adjacent after the change. At a

second level we compare with these results other changes from discontinuous to continuous constituency. A

further level adds comparison of changes of the relative positions of head and dependent (HC, 195–238).

5

Cross-linguistic comparison is set within a theory that recognizes only three mechanisms of syntactic

change: reanalysis, extension, and borrowing. Other phenomena that might be described by others as

mechanisms of change are, in our view, usually a specific instance or type of one of these. Reanalysis is a

mechanism which changes the underlying structure of a syntactic pattern and which does not involve any

modification of its surface manifestation.

6

We understand underlying structure in this sense to include at

least (i) constituency, (ii) hierarchical structure, (iii) category labels, and (iv) grammatical relations. Surface

manifestation includes morphological marking, such as morphological case, agreement, and gender-class.

Extension is a mechanism which results in changes in the surface manifestation of a pattern and which does

not involve immediate or intrinsic modification of underlying structure. Borrowing is a mechanism of change

in which a replication of the syntactic pattern is incorporated into the borrowing language through the

influence of a host pattern found in a contact language.

Other aspects of this theory that are essential for a complete understanding of cross-linguistic comparison

are (i) that syntactic change is regular, in the sense that it is rule-governed and not random (HC, 325–30),

(ii) that research to date has not shown any kind of syntactic change to be absolutely unidirectional, though

many changes are known to proceed usually in one direction (HC, 330–43), and (iii) that reanalysis depends

upon the possibility of multiple analysis

7

(HC, 81–9).

4 An Example: Georgian unda

This example from Georgian will be used in sections 5 and 7 to make several points. As will be immediately

clear, the change is very similar to one in English.

In the historical period the Georgian modal ‘want’ has become an auxiliary, expressing a range of

modalities, including necessity, intention, and obligation.

8

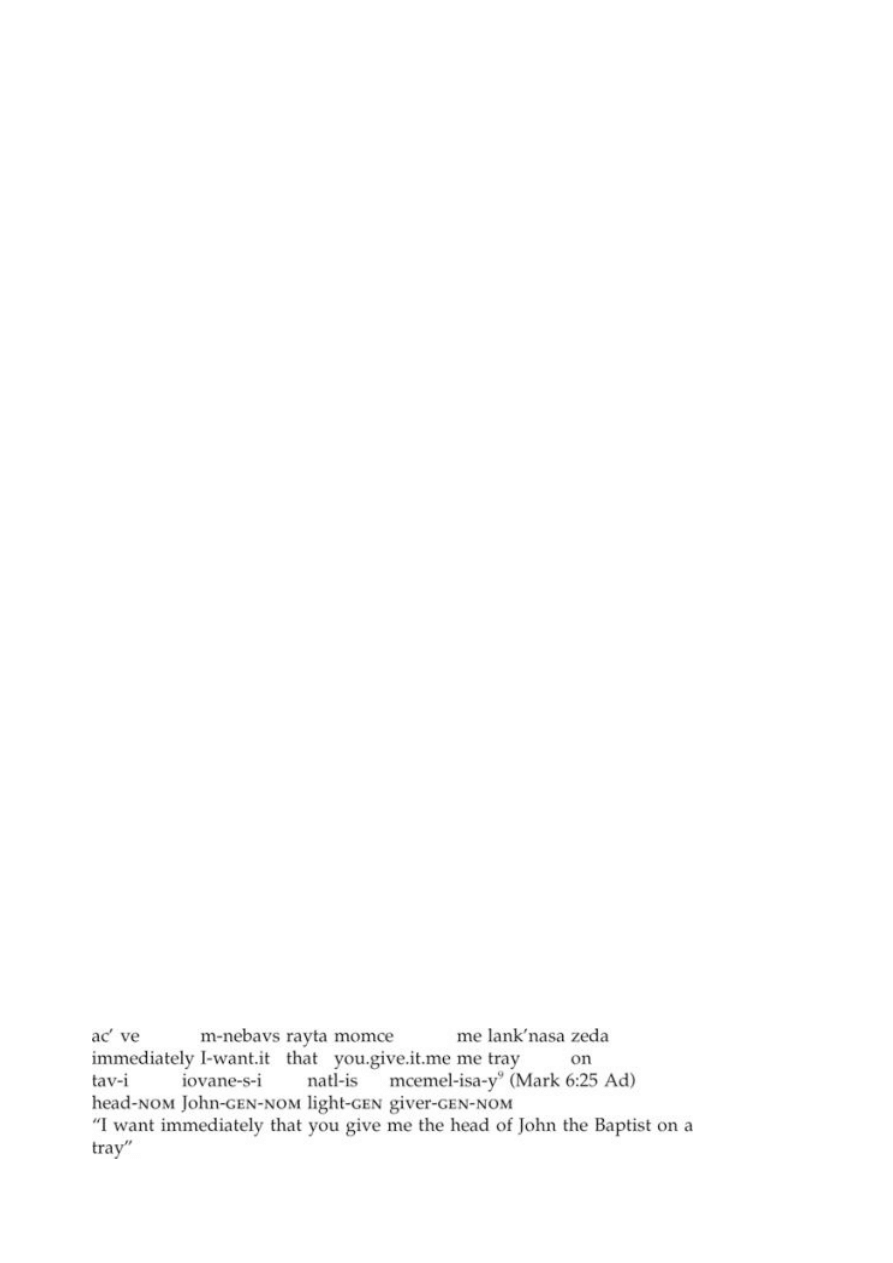

Old Georgian hnebavs ‘wants’ was an independent verb that could have a nominal object or a sentential

object expressed in the subjunctive, in the aorist, or in any of several non-finite forms. Examples with the

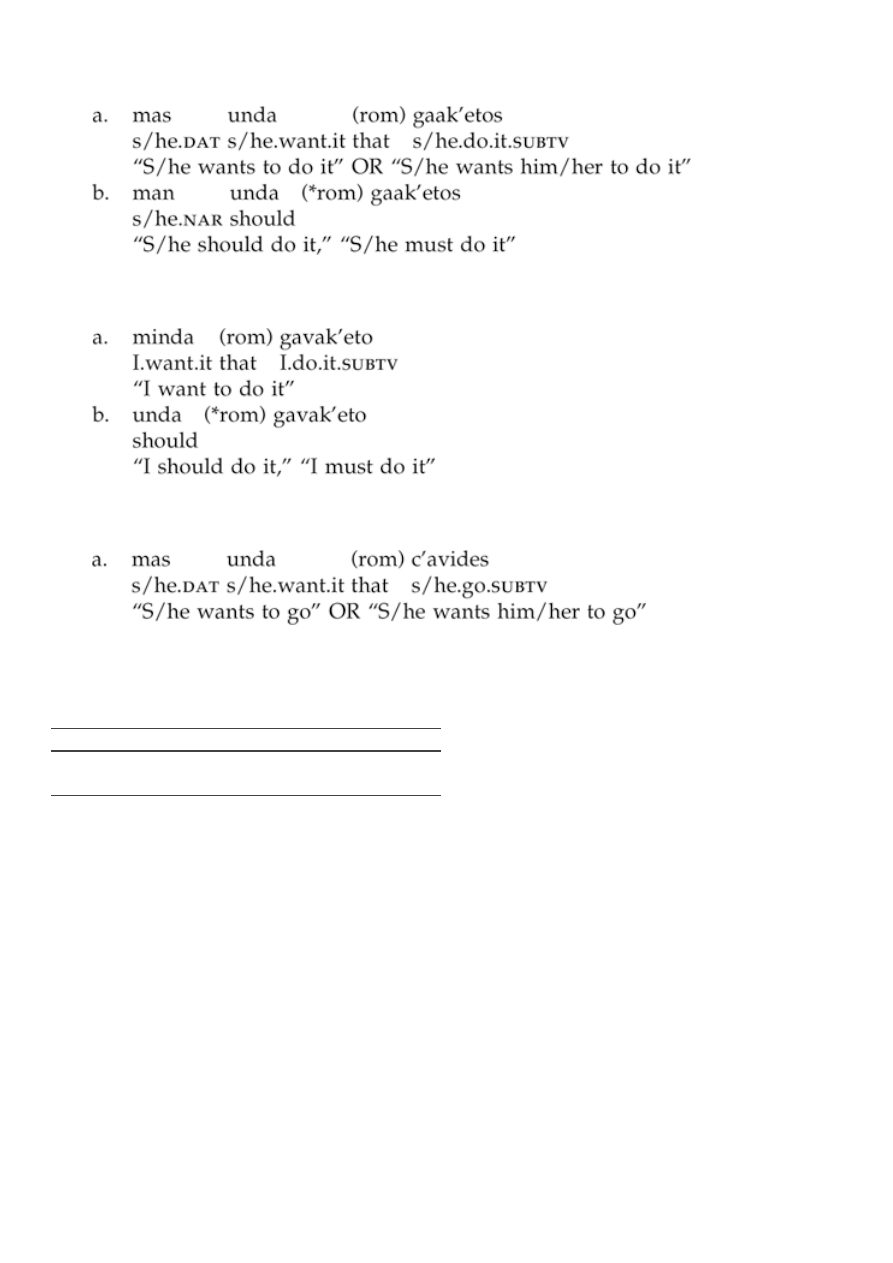

subjunctive are given in (1) and (2):

(1)

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 4 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

(2)

The present tense forms of this verb in Old Georgian included m-nebavs ‘I want it,’ g-nebavs ‘you want it,’

h-nebavs ‘s/he wants it,’ and the imperfect (past) mi-nda ‘I wanted it,’ gi-nda ‘you wanted it,’ u-nda ‘s/he

wanted it.’ The imperfect forms came to be used for the present tense by the eleventh or twelfth century,

and a new imperfect was created: mi-ndoda, gi-ndoda, u-ndoda (Sarǰvela[]e 1984: 412–13). Thus, the forms

used today for the present tense of ‘want’ are so-called past-presents. The verb ‘want’ was and is one of a

number of verbs, traditionally called inversion verbs, which govern a syntactic pattern in which the

experiencer (here, the one who wants) is in the dative and conditions indirect object agreement, and the

stimulus (here, that which is wanted) is in the so-called nominative case and conditions subject agreement.

Thus, the m-, g-, h- and the mi-, gi-, u- prefixes isolated in the forms above in general mark indirect

object agreement, in this instance agreement with the experiencer.

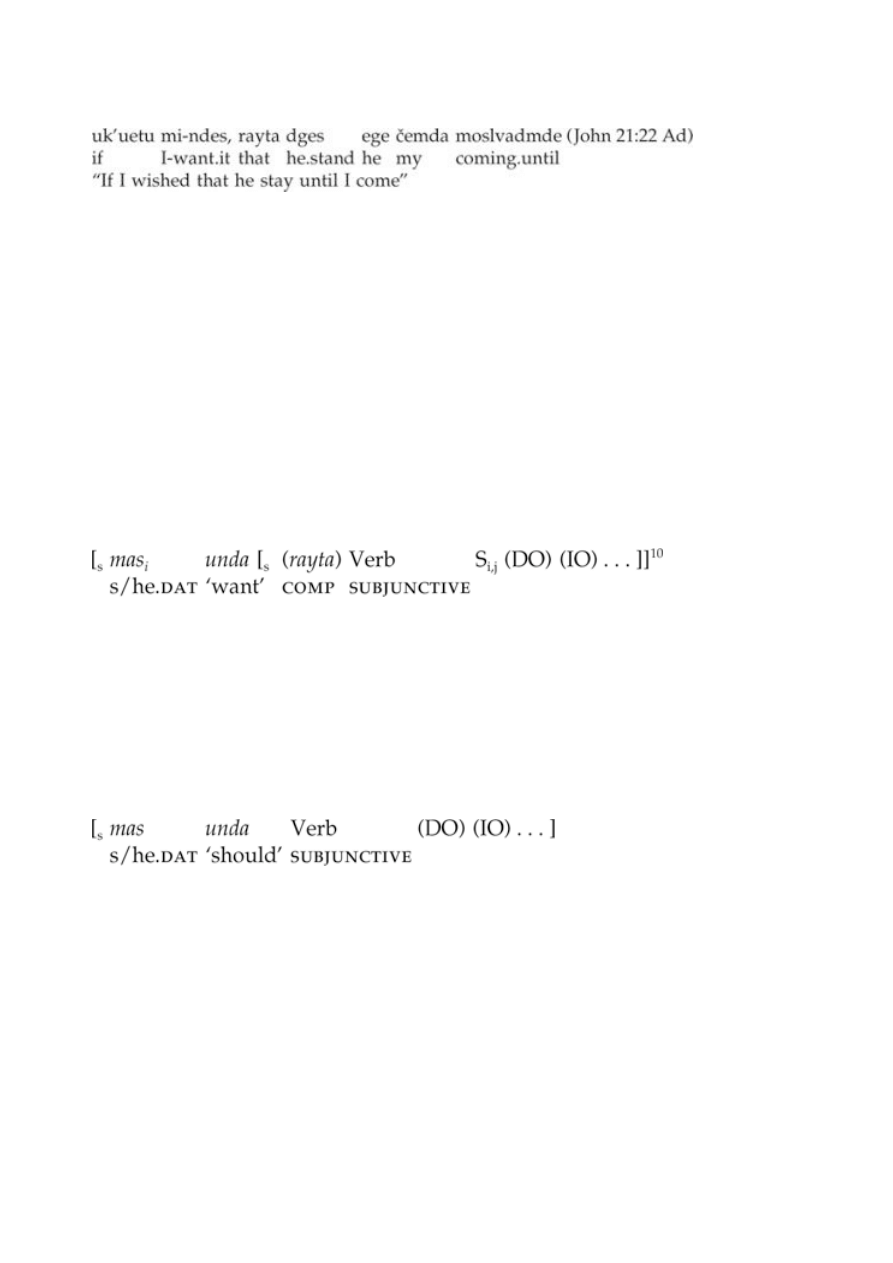

(1) and (2) illustrate the pattern in (3), which occurred in both Old and Middle Georgian (from the twelfth

century):

(3)

The form unda cited in (3) was imperfect tense in Old Georgian, but later present. (1) and (2) show that in

Old Georgian the initial subject of unda (the experiencer, mas in (3)) did not have to be coindexed

(coreferential) with an argument of the verb of the subordinate clause; when the initial subject of the matrix

was coindexed with an argument in the subordinate clause, the latter was generally omitted.

The biclausal structure represented in (3) was reanalyzed as the monoclausal pattern in (4):

(4)

At the same time, the meaning of unda changed from ‘want’ to a range of modalities including epistemic

necessity and deontic obligation. In this innovative usage it ceased to be conjugated, but exists in this single

form (derived from and identical to the third person experiencer, third person singular stimulus form). The

original biclausal construction continues to exist side by side with the new, maintaining its original meaning,

its original structure (with an optional complementizer and with the option of a non-coreferential subject in

the complement clause), and its original complete paradigmatic variation (with the tense adjustment from

imperfect to present described above), as illustrated in part in (5a), (6a), and (7a) below. Thus in the modern

language there is an invariant auxiliary unda ‘should, ought, must’ beside a third person lexical verb form

unda ‘s/he wants it,’ which still alternates paradigmatically with minda ‘I want it,’ ginda ‘you want it,’ and

the plural forms.

11

The independent verb ‘want’ is illustrated below in (5a), (6a), and (7a), and the derived

auxiliary in (5b), (6b), and (7b):

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 5 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

(5)

(6)

(7)

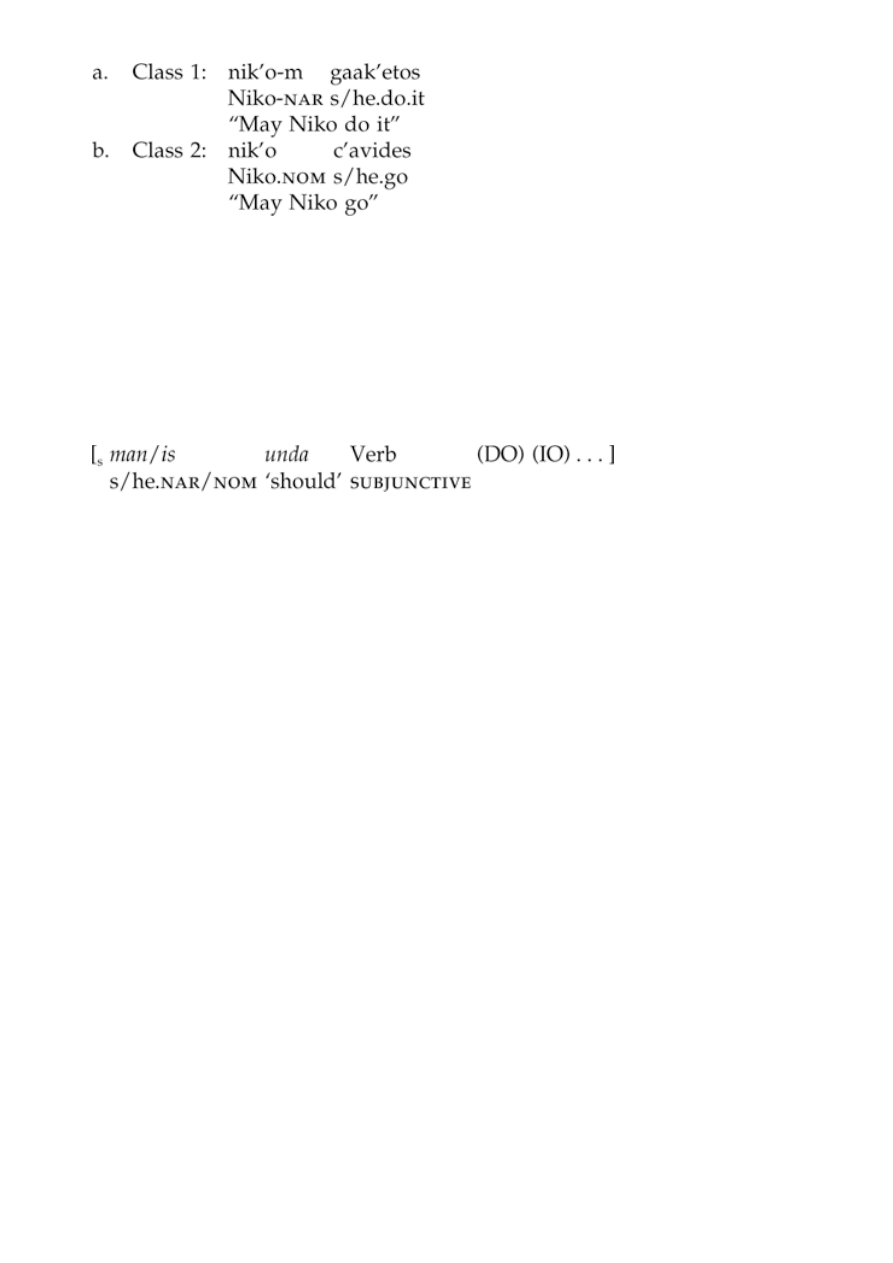

Table 16.1Two case patterns in the subjunctive

Morphological class Subject case Direct object case

1

Narrative

Nominative

2

Nominative

Following reanalysis as a monoclausal structure, other changes in the clausal syntax were also made. In (4),

after reanalysis, the initial subject is still expressed in the dative, the case required by the syntax of the old

verb ‘want’ as an inversion verb; later the pattern required by the (main) verb was extended to this

construction. In Georgian, case marking of subjects varies according to the morphological category of the

(main) verb. The patterns in

table 16.1

illustrate those found in (5b), (6b), and (7b).

12

Class 1 generally

contains transitive verbs, and class 2 a subset of intransitives.

These patterns are required in simple sentences, as illustrated in (8):

(8)

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 6 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

The difference between the case pattern governed by the independent verb ‘want,’ described above, and

those governed by verbs in the subjunctive provides clear evidence that the subject in sentences such as

(5b), (6b), and (7b) is governed by the (main) verb. The verb gaak’ teba ‘do’ of (5)-(6) is a class 1 verb, and

in the (b) sentences the subject can only be in the narrative case, as indicated in

table 16.1

. The verb c'asvla

‘go’ in (7) is a class 2 verb and governs the nominative case; in (7b) the subject can only be in the

nominative. The structure of the (b) sentences is represented in (9), that of the (a) sentences in (3):

(9)

The characteristics that distinguish the older (a) construction of (5)-(7) from the innovative (b) construction

are summarized below:

Source construction (a):

Sentence structure: biclausal

Meaning of unda: ‘want’

Morphology of unda: one form in a complete paradigm varying according to tense-aspect

category, according to person and number of the experiencer, and according to person and

number of the stimulus Government of case of matrix subject: by the verb ‘want’

13

Innovative construction (b):

Sentence structure: monoclausal

Meaning of unda: ‘must, should, need, ought, etc.’

Morphology of unda: invariant

Government of case of matrix subject: by the main verb

5 Reanalysis, Actualization, and Syntactic Doublets

Some scholars have taken the view that smaller, extensional (surface) changes apply in a language until they

force speakers to reanalyze a construction, but Timberlake (1977) has argued effectively that this view is not

reasonable. He points out that there would be no reason for these surface changes, extensions, to take

place unless reanalysis had already occurred. Timberlake (1977) uses the term actualization for the smaller

changes that accommodate the reanalysis. Reanalysis is, in fact, not visible to us directly, and it is only

through meaning change (which is not always present) or through the actualization that follows reanalysis

that we can see its effects.

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 7 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

The Georgian change described above provides a good example of why we cannot reasonably suppose that

reanalysis follows actualization. One might at first suppose that in Georgian the inversion construction is

disappearing, as it did in English,

14

and that this accounts for the replacement of the dative experiencer of

(1)-(2) with a subject with case determined by the main verb, as in (5b), (6b), and (7b). However, the

inherited inversion construction is used with numerous other affective verbs in Georgian, such as those

meaning ‘hear, understand,’ ‘like,’ ‘love,’ and ‘hate,’ and it shows no signs of disappearing with any of these

lexical items. It is also used in a productive desiderative construction, which creates affective forms out of

verbs that are not inherently affective, such as me-mγereba ‘I want to sing, I feel like singing’ (cf. second

and third person forms ge-mγereba, e-mγereba), related to v-mγeri ‘I am singing.’ The same basic

sentence structure is used productively in the evidential construction (Harris 1981). Given that the

construction with a dative subject is used so widely and so productively in the language, the replacement of

the dative experiencer with one in the case determined by the main verb cannot have been part of the

disappearance of this pattern. There simply is no reason for the main verb to begin to determine the subject

of unda, unless that NP is really the subject of the main verb. The reanalysis of the biclausal construction as

monoclausal, as on our analysis, provides the motivation: the case of the (former) subject of ‘want’ begins to

be determined by the main verb because it has become the subject of that verb.

But, one might argue, this approach provides a motivation for actualization but removes the motivation for

reanalysis. Not so. Reanalyses are not caused by the accumulated affect of (unmotivated) actualizations, but

are brought about by at least two other factors. In some instances, such as that discussed by Timberlake

(1977), the source structure becomes ambiguous because of phonological changes. In this type of reanalysis,

the original structure is typically replaced by a new structure because of an ambiguity. In the Finnish case

discussed by Timberlake, for example, the original accusative singular *-m and the genitive singular *-n fell

together through phonological change (final -m > -n), and the accusative object was reanalyzed as a genitive

object. A second frequently noted cause of reanalysis is the provision of stylistic variety or greater

expressiveness. When this is the cause of reanalysis, the innovative structure typically does not replace the

source structure, but continues to coexist with it. This is true of the Georgian example above, where the

innovative modal usage of unda continues to exist side by side with the ‘want’ usage; the innovative usage

provides the language with a new expression. As we see below, our German and Aγul examples are also

innovations of this sort, and indeed changes of this type are relatively common. We have termed reanalyses

in which the innovative structure continues to coexist with the old “syntactic doublets” (Harris and Campbell

1996). While there are probably additional causes of reanalyses, these two types can be clearly identified at

this time. Thus, reanalyses apply because of ambiguity or a need for variety of expression (or for other

reasons), and actualization gradually brings the innovative structure into line with the rest of the grammar.

A further reason for rejecting the view that surface changes lead up to reanalysis is that this would entail

that these smaller changes just coinciden-tally lead in the same direction. While some reanalyses are simple

enough that few adjustments need to be made later by extensions, in other examples many extensions are

needed to make the innovative structure consistent with the rest of the language.

15

Reanalysis of modals in

English is a good example; according to one count, as many as twelve separate surface changes were made

in connection with this reanalysis (Lightfoot 1979: 101–13). To claim that even a significant proportion of

these applied before reanalysis, coincidentally accommodating the same reanalysis, even though it had not

yet applied, would not be reasonable. The fact that a similar reanalysis is found to apply in language after

language (illustrated by Georgian in section 4 and Aγul in section 6.1), makes such a hypothesis even less

tenable. I conclude, therefore that reanalyses apply relatively early, often setting off a series of extensions,

which accommodate the new structure to the existing grammar.

6 Simplification of Biclausal Structures

In sections 6.1–6.2 below, I compare with the Georgian modals two additional examples of clause fusion,

which we define through the two-part definition in (10):

(10) Clause fusion is a diachronic process in which:

i a biclausal surface structure becomes a monoclausal surface structure, and

ii the verb of the matrix clause becomes an auxiliary, that of the subordinate clause becomes the

main (lexical) verb.

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 8 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

In section 6.1 I present a change in Aγul for direct comparison with Georgian, but for purposes of this

presentation I omit similar changes in the modals of English, German, and other languages. In section 6.2 I

take the comparison to a higher level, adding a description of an example of fusion that does not involve

modals, namely the formation of the German perfect. Again, for reasons of length, I omit explicit

comparison with perfects in English, French, Modern Greek, Georgian, etc.

6.1 Aγul

Aγul is a member of the Lezgian subgroup of the North East Caucasian language family. This example differs

from those given in section 4 and in section 6.2 in that this change is not attested. For this reason, too little

detail is known about the change in Aγul for this language to provide us with major input to our inductive

study of the nature of the change studied. It is included here because the close similarity of this change to

that documented in section 4, given that the two languages are unrelated

16

and not in contact, helps to

establish that this is a common sort of change.

17

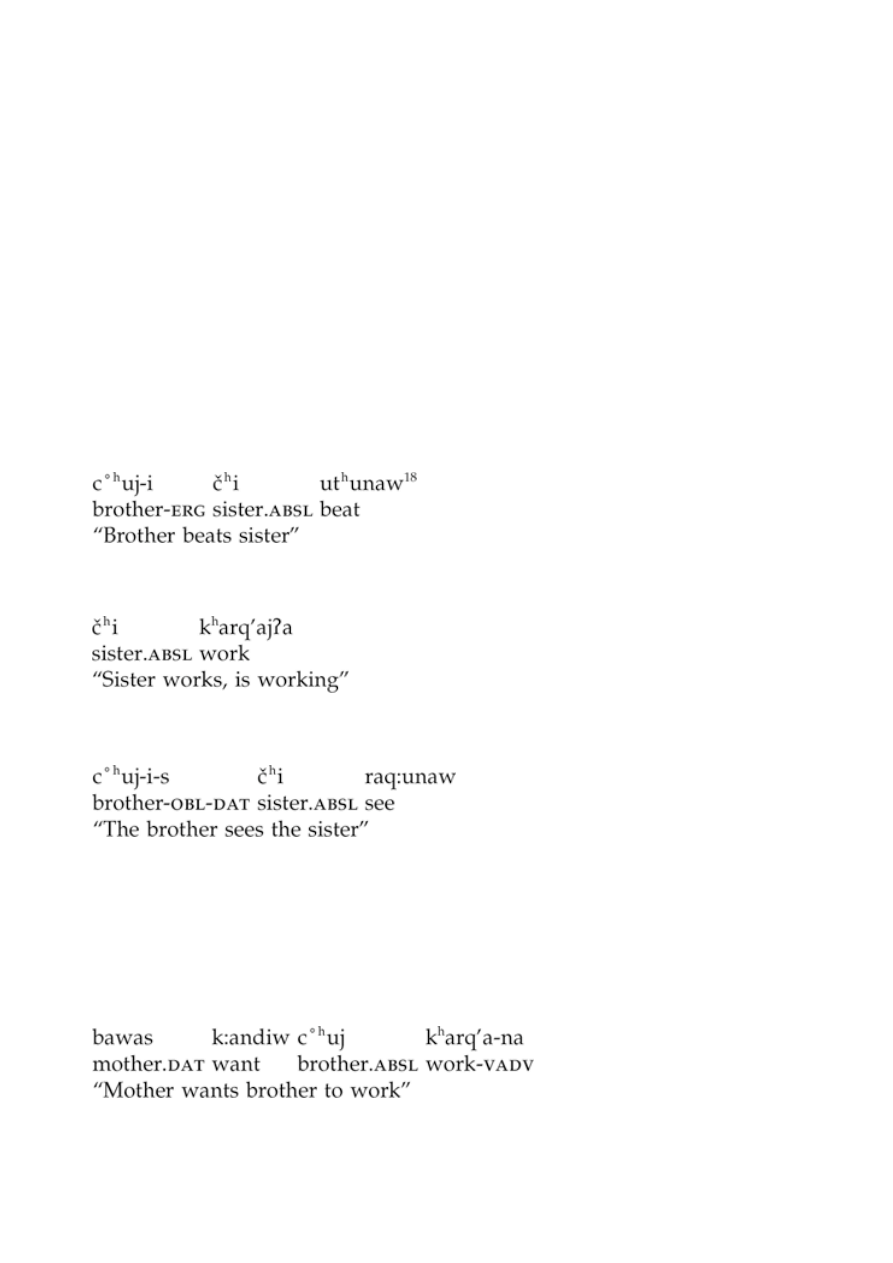

The case marking system of Aγul is typical of Lezgian languages and of other members of the North East

Caucasian family. Subjects of ordinary transitive verbs are in the ergative case, as in (11), and subjects of

intransitives and direct objects are in the absolutive case, as in (12):

(11)

(12)

(13)

The basic word order is SOV, as illustrated here.

19

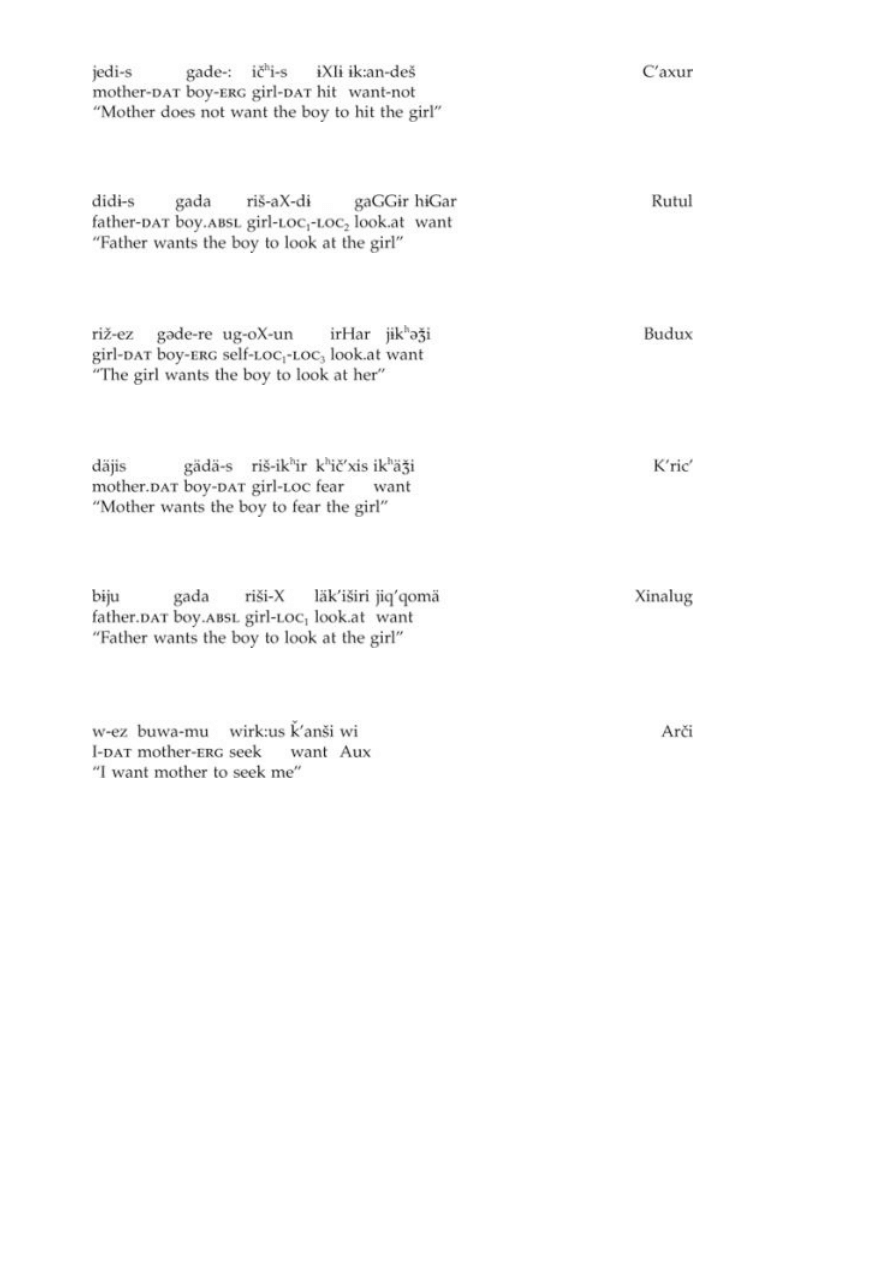

In Proto-Lezgian a root modal ‘want’ occurred as a matrix verb, governing an experiencer in the dative case,

and occurring with an embedded clause; (14) illustrates this in Aγul:

(14)

Every Lezgian language preserves this basic pattern, though the marking on the embedded verb varies from

language to language (see appendix). In Aγul, in this pattern the verb of the embedded clause is expressed

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 9 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

language to language (see appendix). In Aγul, in this pattern the verb of the embedded clause is expressed

in the non-finite form referred to as a verbal adverb, with the ending -na. When the experiencer of the

matrix clause is coreferential with an argument of the embedded clause, the latter is not expressed and the

verb takes the infinitive form:

(15)

(16)

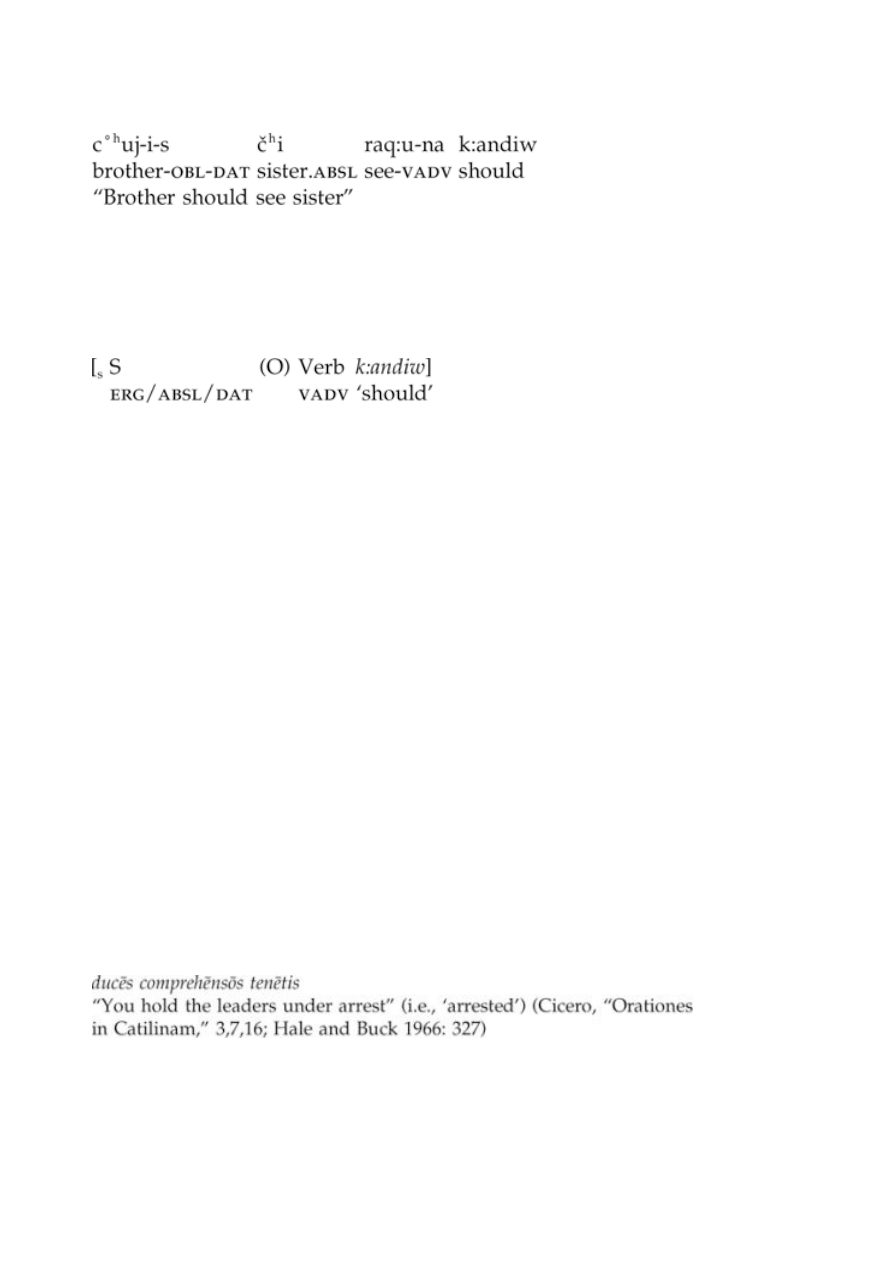

(17)

Note that in (15)-(17), the clauses of (11)-(13), mutatis mutandis, are embedded under ‘want.’ The complex

constructions in (14) and in (15)-(17) have the same basic structure, shown in (18):

(18)

In this structure, the matrix S is the dative experiencer of ‘want,’ and the S of the embedded clause may be

a dative experiencer or an ergative or absolutive subject.

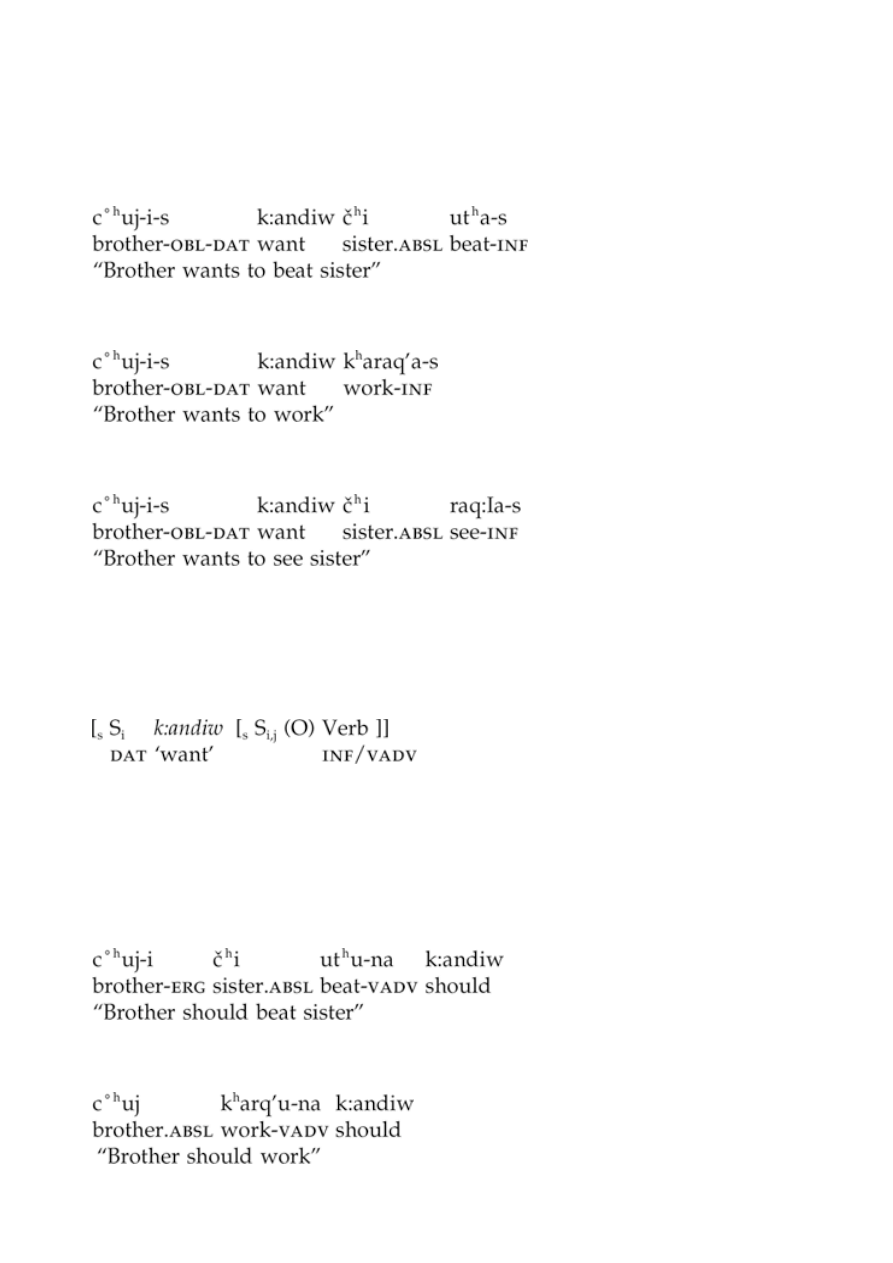

The structure in (18) has been reanalyzed as a single clause, illustrated in (19)–(21):

(19)

(20)

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 10 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

(21)

Notice that the meaning of k:andiw has also changed to ‘should.’ The mono-clausal structure of (19)–(21)

can be represented as (22):

(22)

Observe the differences between the older construction, (18), and the innovative construction, (22): (i) The

verb k:andiw ‘want’ in (15)-(17) is a matrix verb, while in (19)-(21) the same form has the meaning ‘should’

and the status of an auxiliary. (ii) The word order of the complex examples (15)-(17) is consistent with the

basic SOV order of the language, in that each clause adheres to this order. In (19)-(21), too, the order in the

clause is SOV Aux; but because we now have a single clause, the order of the individual words is quite

different, (iii) The case of the experiencer in (15)-(17) is dative, determined by the verb ‘want’; this is

consistent with the case used for experiencers of other affective verbs, such as ‘see’ in (13). In (19–21), on

the other hand, the case of the subject, ‘brother,’ is determined by the main verb, as can be seen by

comparing (19)-(21) with the simple sentences at the beginning of this section, (11)-(13). Thus, ‘beat’ takes

an ergative subject in (19), as in (11); ‘work’ requires an absolutive in (20), as in (12); and ‘see’ governs a

dative in (21), as in (13).

There are many similarities between the attested change in the modal in Georgian and the transition

undergone by Aγul. Some of these similarities are also shared by the changes undergone by the modals in

English and other languages, but others are not shared. Because the data surveyed at this level necessarily

omit a number of relevant languages, I draw no conclusions at this stage but go on to a higher level

comparison. At this point I describe the origin of the perfect in French (section 6.2) and the detailed

actualization of the reanalysis of the haben-perfect in German (section 6.3). These two changes can be

compared with the origins of the modal auxiliaries in Georgian (section 4) and Aγul (section 6.1) to formulate

generalizations about clause simplification in section 6.4.

6.2 French perfect

Latin had a construction making use of a matrix verb tenbre ‘hold,’ habēre ‘keep, hold,’ or another verb

with a similar meaning:

(23)

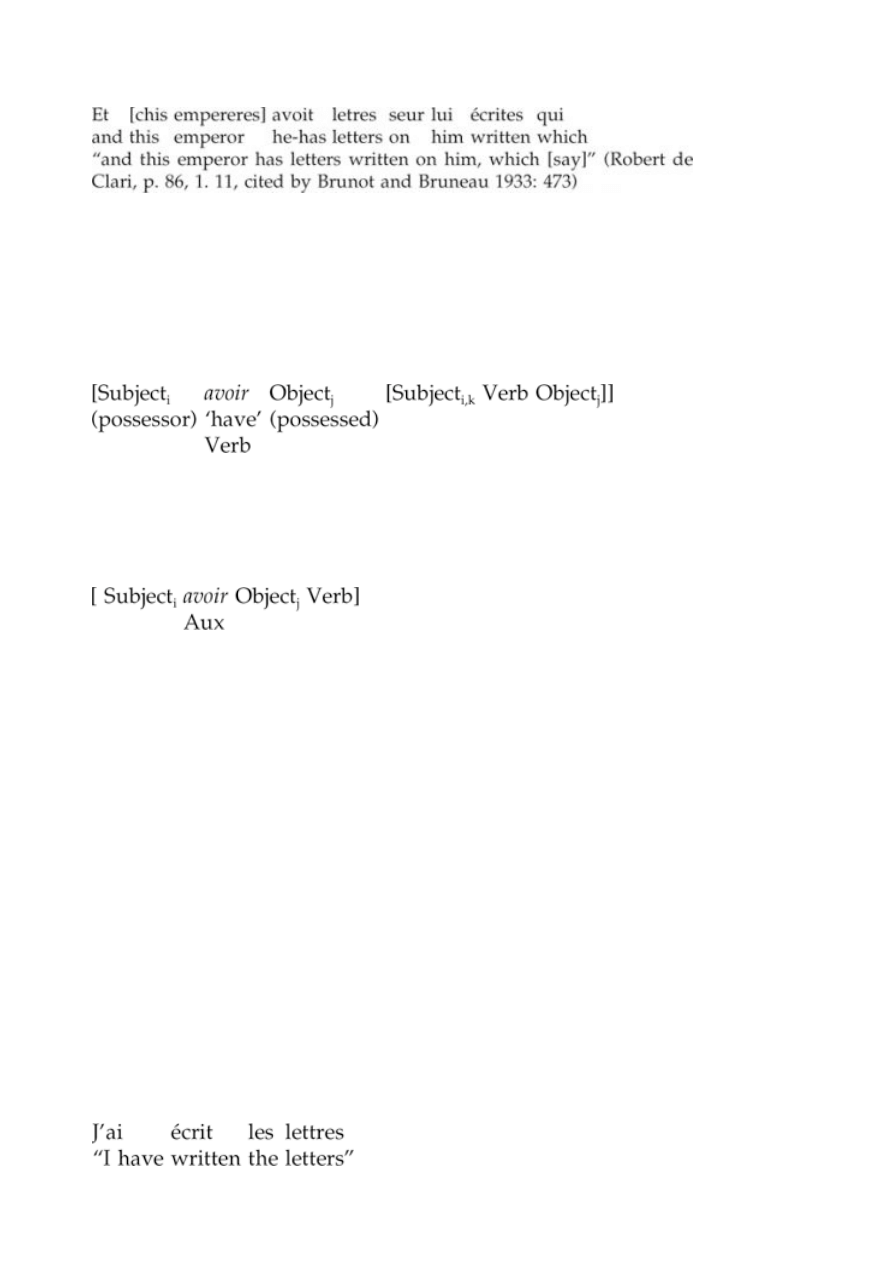

Specialists analyze this as a biclausal structure, with the verb of the subordinate clause expressed as a past

passive participle, here comprehēnsōs ‘arrested,’ which forms a constituent with the direct object of the

main clause, here ducēs' leaders.’ This structure is reflected in early French examples such as (24):

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 11 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

(24)

The passage occurs on a statue and describes the letters (words) written on the statue of the emperor. This

is likewise analyzed by specialists as a biclausal construction, with the matrix verb avoir ‘have,’ and with the

verb of the subordinate clause expressed with the past passive participle, écrites ‘written.’ The biclausal

possessive structure of Latin and early French can be schematized as (25):

(25)

This was reanalyzed, yielding the structure schematized in (26):

(26)

The reanalysis involved the following changes, among others: (i) The biclausal structure of (25) became

monoclausal in (26). (ii) The matrix verb avoir ‘have’ is reflected in the auxiliary of the same form in (26). (iii)

Not shown in (25)-(26) is the fact that the meaning of the construction has changed from, roughly, ‘one

possesses something to which something has been done’ to ‘one has done something.’ An example from

Modern French showing these changes is (27):

(27) J'ai écrit les lettres

“I have written the letters”

The reanalysis of the possession construction as a perfect has been greatly simplified here; it is described in

greater detail in Vincent (1982), in HC (ch. 7), and in other sources cited there. The actualization of this

reanalysis has not been included here, and I turn instead to the more complex actualization of the parallel

reanalysis in German.

6.3 German perfect

The expression of the perfect with haben ‘have’ or eigan ‘own,’ which eventually developed in other North

and West Germanic languages, is not attested in the earliest forms of German; it first appears in ninth-

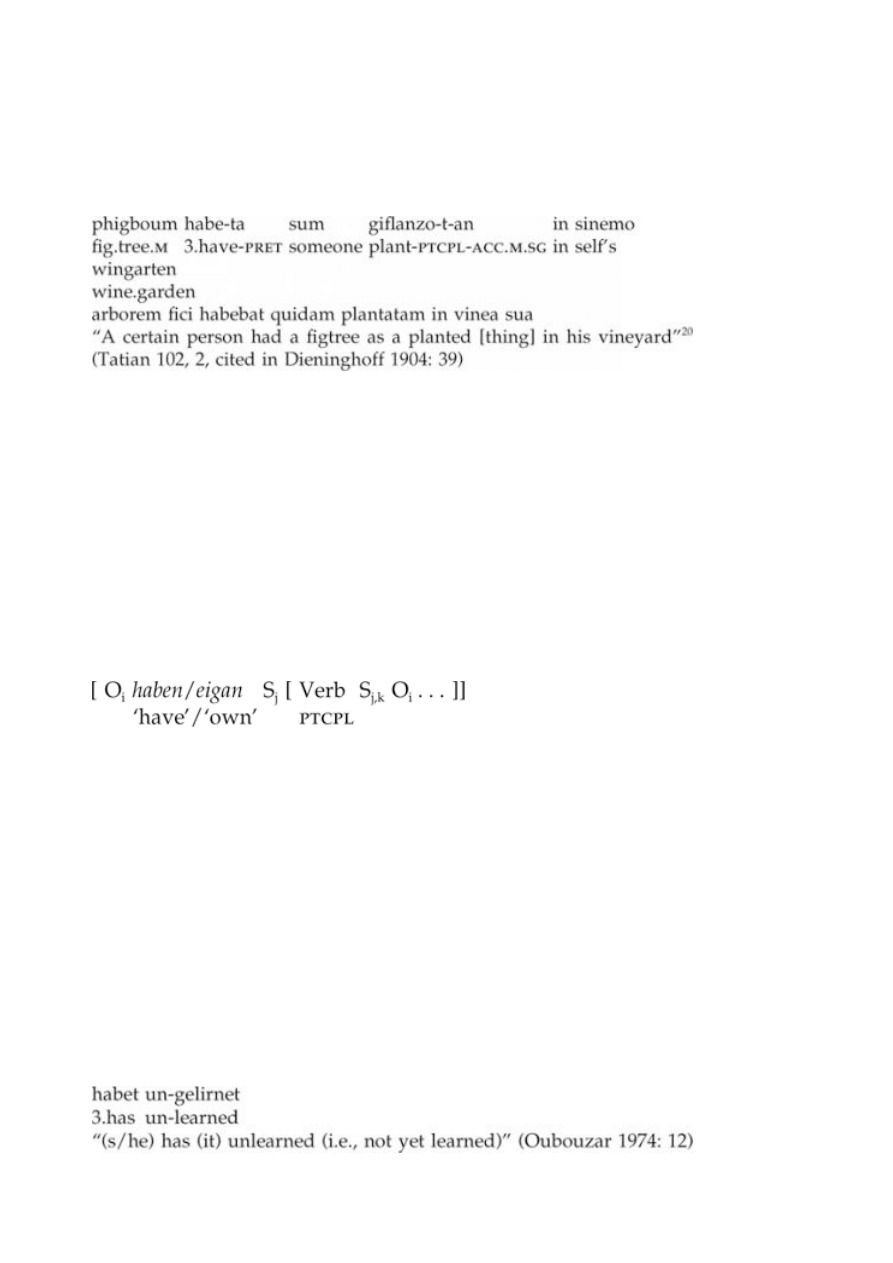

century works (Ebert 1978: 58). Example (28) illustrates several important characteristics of this

construction:

(28)

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 12 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

First, note that it was not required that the subject of the matrix clause be coreferential with that of the

embedded clause, as illustrated in (28), and as schematized in (29):

(29)

(In (29) the clause-internal order of (28) is followed, but not all aspects of this are necessarily significant.)

Second, because this construction states literally that something is possessed, there must exist a thing

possessed, a direct object; in (28) this is phigboum ‘figtree.’ Third, as indicated in (29), the object of the

matrix clause and of the participle had to be coreferential; O

i

in the participle did not show up on the

surface. However, only transitive verbs were originally used with haben/eigan. Fourth, the participle is a

deverbal adjective, which is stative in character. Because the embedded clause, ‘planted … in his garden,’

modifies the direct object, it agrees with it in case, gender, and number. In truth, agreeing forms were

infrequent in even the oldest German (Ebert 1978: 58), but examples such as (28) with agreement reveal the

grammatical relations that existed. An additional adjectival characteristic is that the participle could be

negated with the prefix un- ‘un-,’ as in (30):

(30)

The possibility of non-coreferential subjects (as in (28)), the requirement of a direct object in each clause,

and the adjectival nature of the participle establish that the construction in (29) is biclausal.

The German periphrasis with haben/eigan was originally used only with transitives as part of an expression

of the perfect. The perfect of intransitives was formed with wesan ‘be’ or, under certain circumstances, with

werdan ‘become’ in early texts (Paul 1949: 334; see Dieninghoff 1904: 8–9 for details). The perfect with

intransitives developed somewhat earlier than that with haben/eigan, the focus of our attention here, the

latter not occurring in the earliest texts.

21

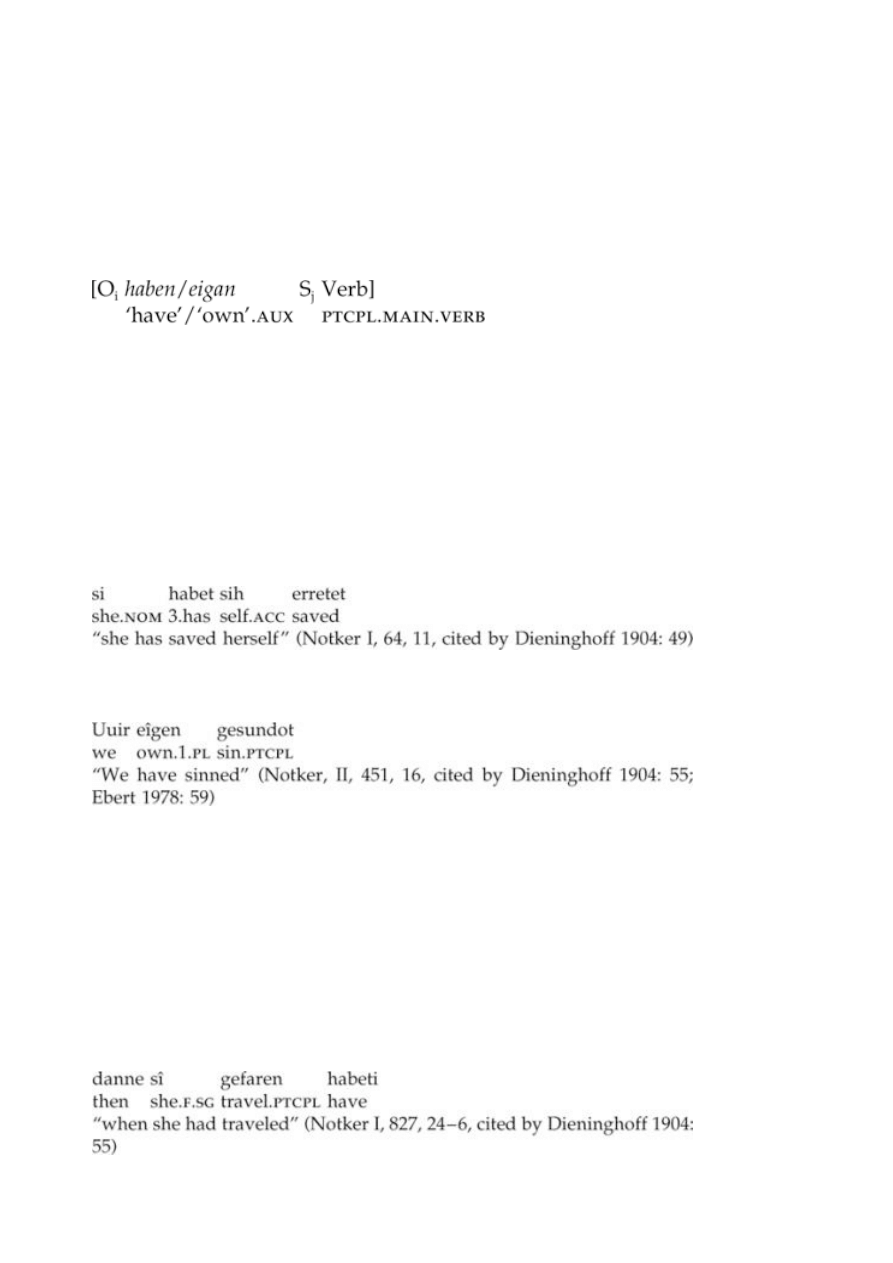

The reanalysis of the pattern (29) changed its biclausal structure to mono-clausal, with haben/eigan ‘have,

hold, own’ becoming an auxiliary and the participle becoming the expression of the main verb. Another

result of the reduction to a single clause was that there was a single subject of the auxiliary and the main

verb; no longer was it possible for each to have its own subject, as it was in (29):

22

(31)

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 13 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

Reanalysis also involved a change in meaning; while the old participle was static, in the new meaning it was

dynamic. The old analysis, (29), included the notion of possession (e.g., ‘I hold it done’), while the derived

(31) expresses the perfect (e.g., ‘I have done it’). One of the manifestations of the change from the

possession meaning is the appearance of reflexives; since ‘one possesses oneself’ is not a very useful

expression, we may assume that this usage was eschewed until after the change in meaning. In

Dieninghoff's (1904:49) corpus, Notker is the first to have the direct object reflexive, as in (32):

(32)

Thus, by Notker's time, approximately 1000 ce, the appearance of reflexives shows that in at least some

examples the meaning of possession had been replaced by that of the perfect.

The actualization of the reanalysis involved a number of structural changes. According to evidence cited by

Dieninghoff (1904:15–16) and Oubouzar (1974), the transitive perfect with haben/eigan ‘have, hold, own’

developed through a number of stages, next tolerating sentential objects or genitive-case objects, then

elided objects. Not until Notker's texts (c.1000) could (31) be used without an object in the matrix clause, as

illustrated by (33)-(34):

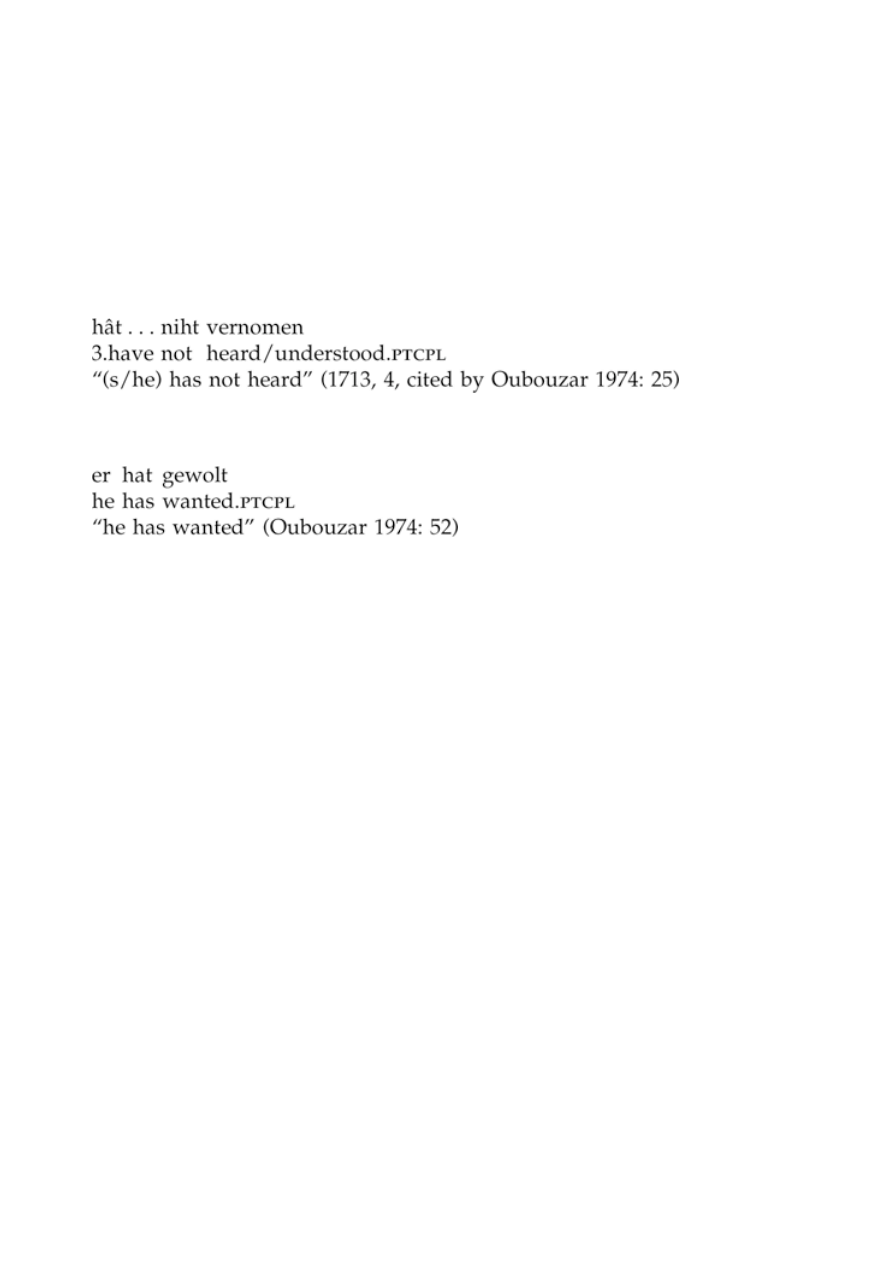

(33)

(34)

An additional structural change is the loss of the requirement of the corefer-ential object previously

necessary in the embedded clause (the participle). Hence, in Notker's work the participle may be intransitive,

as in (33) and (34).

The participle likewise lost its adjectival character. As mentioned above, the inflection illustrated in (28) was

never common, but it now ceased to occur altogether.

23

While past participles continue to be negated as

adjectives with the prefix un- ‘un-,’ the negation of the perfect is expressed instead with the negative

particle, niht ‘not.’ (35) gives an example from the Nibelungenlied (early thirteenth century):

(35)

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 14 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

The transitive (now also the intransitive) perfect was consolidated by the loss of the defective auxiliary eigan

‘own’ in this function.

24

Oubouzar (1974) has investigated details of the changes in aspect, as the innovative analytic perfect was fit

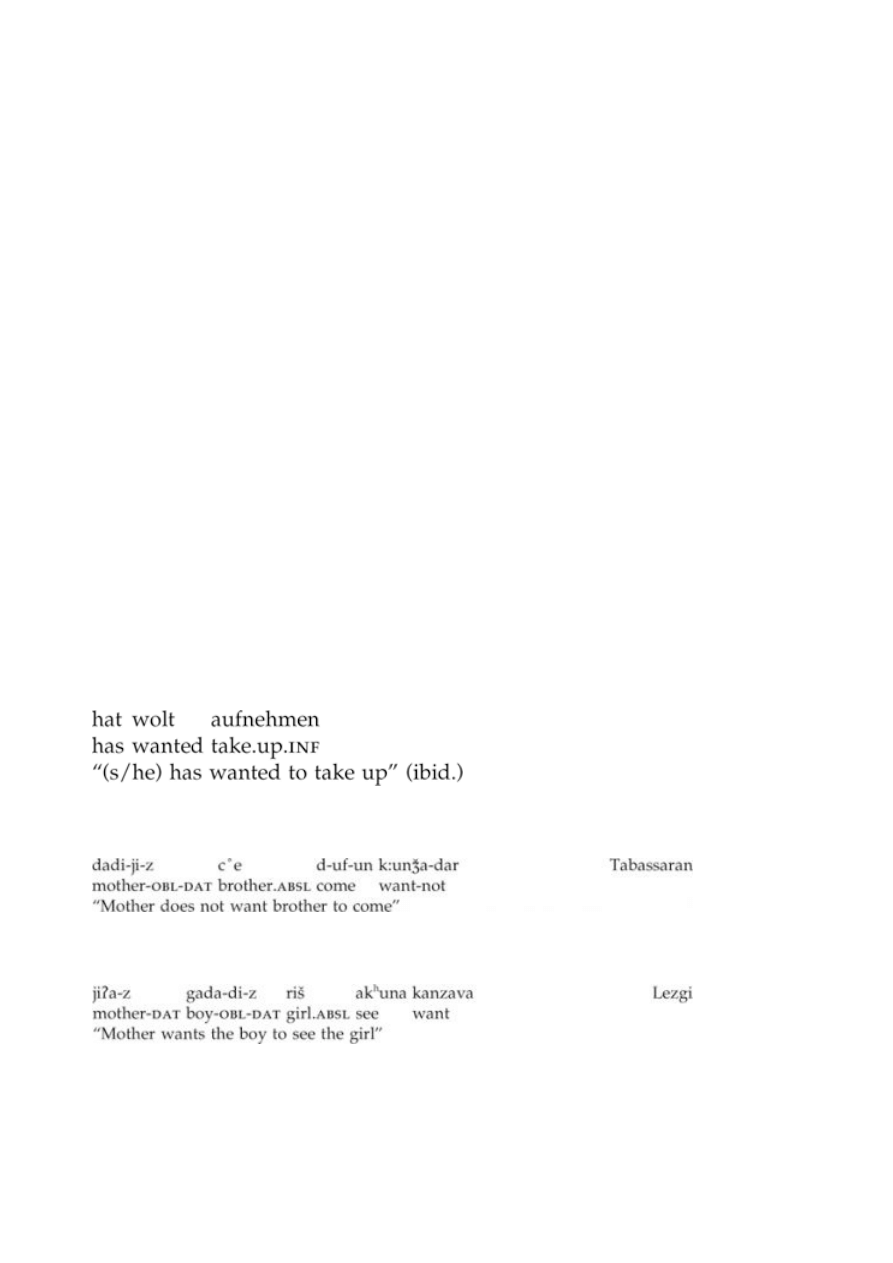

into the existing system of tense/aspect/ mood. In particular, in the earlier works, the perfect with haben

(/eigan) was only rarely used with the durative (her kursiv) verbs - the modals and the verb haben ‘have’

itself (see also Paul 1949: 334). By early sixteenth-century texts, however, haben could be used both in the

pattern illustrated in (36), and in that in (37), both with modals:

(36)

(37)

Several examples of perfect forms of the verb haben ‘have’ itself (hat gehabt ‘has had’) are found in the

fifteenth century, but they become more numerous in the following century (Oubouzar 1974: 52). By the

middle of the sixteenth century we find new future perfects (wird getan haben ‘will have done’) (Oubouzar

1974: 65). Oubouzar (1974) documents additional changes that incorporate the perfect in haben fully into

the verbal system of the language.

25

Four of the structural changes described above - reduction to one subject, loss of the matrix object, loss of

the embedded object, and loss of the adjectival character of the participle - clearly establish that the output

construction is monoclausal. I suggest, however, that for quite some time, both analyses were available to

speakers. Oubouzar (1974: 12), for example, points out that most of the examples of the haben/eigan

perfect in Notker's works are open to the original “possession” interpretation, while a few require

interpretation as perfects.

Some scholars have argued that the Germans borrowed the perfect from Latin or from the Romance

languages (e.g., Meillet 1930: 129). However, Ebert (1978: 59) argues that the similar construction in Latin

must have been borrowed from the Germans, inasmuch as a cognate construction is found in Old Icelandic,

which could not have been influenced by Latin or by the languages descended from it. Benveniste (1966)

argues that the fact that the perfect with haben/eigan forms a complex system with the perfect in wesan

‘be’ and in werdan ‘become’ and that at least some parts of this system are found in all Germanic languages

show that this could not have been borrowed outright from Latin. For our purposes it is not essential to

reach a conclusion on this issue, since both groups of languages underwent similar processes (see, e.g.,

Vincent 1982 or Brunot and Bruneau 1933 on French). If the construction was borrowed, it was not simply

the monoclausal structure, (31), that was borrowed. I assume that if the construction was borrowed, multiple

analyses (29) and (31) were borrowed together; the direction of change would presumably follow from this.

6.4 A universal characterization of clause simplification

When we compare the changes described in section 4, in section 6.1, section 6.2, and in section 6.3 with

others that cannot be described here, we find a regularity that has not been expressed (but see HC, 191–4).

When the construction is first reanalyzed and it begins to be used in a new way (here, for the formation of

the perfect in German, for modality in Georgian and Aγul), conservative rules, reflecting the source structure,

at first continue to make it appear that the auxiliary determines grammatical characteristics of those

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 15 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

at first continue to make it appear that the auxiliary determines grammatical characteristics of those

constituents that were in the matrix clause of the source construction, while the main verb does so for those

that were in its embedded clause. Grammatical characteristics that are at issue include (i) the number of

arguments, the argument roles they fill, and the marking they bear, (ii) the triggering of any lexically

conditioned obligatory synchronic rules (for example, Inversion), (iii) the ability to undergo optional

synchronic syntactic rules (for example, Antipassive), and (iv) any exceptional behavior (for example, Quirky

Case, suppletion). In German, for example, after the perfect usage had begun the following features of the

source construction, (29), were at first carried over to the post-reanalysis construction, (31): (i) haben

‘have’/eigan ‘own’ required its own object; (ii) haben ‘have’ /eigan ‘own’ was used only with transitive main

verbs; (iii) participles were adjectival, as shown by negation with un- and by occasional examples of

adjectival agreement; (iv) haben ‘have’ itself could not have a perfect; (v) reflexives did not occur, etc.

Similarly, immediately after reanalysis in Georgian the reflex of the subject of the matrix verb continued to

occur in the dative case (as it does even today in the ‘want’ construction of (5a), (6a), and (7a)).

However, in each instance the monoclausal construction was eventually extended to all aspects of the

structure. For German details of this transition were presented above in section 6.3. In Georgian, the case

pattern of the main verb, the reflex of the verb of the embedded clause, was extended to the mono-clausal

structure. (Additional support for the view that after reanalysis the main verb governs the syntax of the

clause comes from additional examples cited in HC, ch. 7.)

Our view is that after reanalysis of biclausal structures as monoclausal, although the main verb governs the

syntax, the auxiliary at first appears to govern the constituents that were originally in its clause. This

paradox follows in part from our definition of reanalysis, which changes abstract structure but not surface

structure, as discussed above in section 5. We have stated this generalization informally as the Heir-

Apparent Principle:

The Heir-Apparent Principle

When the two clauses are made one by diachronic processes, the main verb governs the syntax

of the reflex clause.

Perhaps this view can best be understood by comparing it with phonological change. After the loss of a

conditioning sound, the effects of a phonological rule often continue for some time to be realized. For

example, in German, i or j conditioned umlaut in a preceding syllable; thus, beside the singular gast ‘guest,’

Old High German had plural gast-i, later gest-i. But when the plural suffix became e, which was not an

umlaut trigger, the umlauted vowel continued for a time to appear: gest-e ‘guests.’ Although the parallelism

of the phonological example and the syntactic example is not complete, the former helps us to see that in

language change the form is conservative. In the umlaut example, the stem retains its old form, as though

the triggering i were still there. In the syntactic example, the grammatical characteristics of the source

construction are retained for a time, as though the structure were still biclausal. In gest-e we can clearly see

the absence of the umlaut trigger, but a monoclausal structure resulting from reanalysis can only be inferred

from other characteristics. While the main verb actually governs the syntax of the reflex clause, for a time

the conservative form retains the characteristics of its former structure.

It is not a coincidence that the conservative characteristics of a simplified biclausal structure are often the

very characteristics that have led synchronic syntacticians to posit complex deep structures for simple

surface structures. The characteristics are evidence of a conflict between the two (or more) analyses assigned

to the structure by speakers, and a contrast of deep and surface structure provides one way of reconciling

these competing analyses synchronically. Diachronically they are reconciled by the recognition of different

source and reflex structures.

It is not only the changes illustrated above that show the regularity noted in the Heir-Apparent Principle. In

fact, this generalization is not limited to clause fusion (defined above in (10)). The same regularity is also

found in focus clefts that become monoclausal focus constructions and in biclausal quotation structures that

become monoclausal quotative constructions (HC, ch. 7).

7 The Explanatory Value of Cross-Linguistic Comparison

The most obvious value of cross-linguistic comparision of transitions in syntax is that it enables us to

identify universals of syntactic change. While we may develop hypotheses about what is universal on the

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 16 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

identify universals of syntactic change. While we may develop hypotheses about what is universal on the

basis of study of a single language, hypotheses formed in this way are often little more than speculation.

Hypotheses about the nature of change that have been developed on the basis of careful consideration of

several, varying languages can be taken seriously and tested against further data. Data on syntactic changes

are plentiful, and thus there is no shortage of material on which to test hypotheses.

In connection with the identification of universals, comparison also enables us to identify with some

assurance those aspects of changes that are language-particular. By comparing the same change in very

different, unrelated languages we can both isolate a core that is universal, and identify actualizations that

are, in some cases, very different; an example of this is the comparison of the development of Georgian

modals and that of English modals (HC, 173–82). By comparing the same change in structurally similar

languages, we can begin to formulate an idea of the kinds of actualization required by a particular reanalysis

under shared circumstances; an example of this sort offered here is the comparison of Georgian and Aγul.

Morphology often reveals what is going on in syntax. The examination of a change in a language with a

relatively rich morphology may provide evidence relative to the same change in a language with fewer overt

indications of syntactic relationships. In this way, in some instances, through comparison we can learn more

about a change in a single language than might have been possible through the study of that language

alone.

As a by-product of comparison, we may note aspects of change that could, in principle, have been observed

by examining a single language, but which, in fact, have been overlooked. Perhaps this is simply due to the

linguist recognizing in an unfamiliar language system a regularity that is easily ignored in the familiar. One

example of this is the recognition that if the same change (e.g., independent modal verb to modal auxiliary)

occurs in many languages without the particular configuration of morphological and syntactic traits that

some have found so important in one language, that configuration cannot be a necessary condition to the

change (see discussion above in section 5 and in HC, 176–82). Another example is the recognition that in

reanalysis, the innovative construction need not displace the source construction (Harris and Campbell

1996), but may result instead in syntactic doublets.

APPENDIX

(38)

(39)

(40)

(41)

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 17 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

(42)

(43)

(44)

(45)

(46)

Examples (38)-(45) are from Kibrik (1979–81); the Udi example (46), the only Lezgian language not included

in Kibrik (1979–81), is from my own fieldnotes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I am grateful to Lyle Campbell for many discussions of these ideas and for comments on an earlier version of

this manuscript. Naturally, remaining errors are my own.

1 The discussion throughout draws on the approach set out in Harris and Campbell (1995) (henceforth HC).

Although this chapter is entirely new, many of the ideas expressed in it are developed in greater detail in HC

(1995), and I have made no attempt to distinguish my ideas from our ideas.

2 This statement is intended in a general sense. I do not wish to be thought of as a proponent of hermeneutics,

since I prefer cause-and-effect explanations where possible.

3 More specific critiques of Lightfoot's proposals and of other theory-driven approaches may be found in HC,

passim.

4 Kroch (1989a) is a partial exception to this; he accepts the position of Ellegård that do-Support originated as

causative do. However, little attention is given to how this interacts with the implementation that he documents

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 18 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

causative do. However, little attention is given to how this interacts with the implementation that he documents

carefully.

5 The order described here is, of course, the order of investigation, not the order of presentation of the results.

6 This definition is based on that given in Langacker (1977: 58); we have also been much influenced by the

discussion of reanalysis provided in Timberlake (1977).

7 It is not at all a coincidence that the multiple analyses recognized by speakers in the process of reanalysis often

correspond to different levels of syntactic analysis proposed by synchronic syntacticians. See further section 6.3

below.

8 Georgian is a member of the Kartvelian language family. It is attested from the fourth or fifth century ce.

9 The following abbreviations are used in glossing examples: absl absolutive case, acc accusative case, dat dative

case, gen genitive case, nar narrative case, nom nominative case, obl formant of oblique stem; m masculine, f

feminine; sg singular, pl plural; comp complementizer; aux auxiliary, inf infinitive, pret preterite, ptcpl participle,

subtv subjunctive, vadv verbal adverb; 1. first person subject, etc. In the identification of Old Georgian texts, “Ad”

indicates the Adisi codex.

10 The order most frequently found in the embedded clause of this construction is verb-initial. In (3) and other

such formulas, S is subject, O object, DO direct object, IO indirect object, and V verb.

11 It is quite common for a source construction to persist beside the innovative structure derived from it by

reanalysis. For discussion and examples, see HC, 81–9, 113, 310–12.

12 A more detailed description of the inversion pattern in Old Georgian, with examples, may be found in Harris

(1985: 273–86) and a description and illustrations of the patterns summarized in table

16.1

in the same source,

especially pp. 49–51. For Modern Georgian, the inversion construction is described in Harris (1981: 117–45), and

the patterns of

table 16.1

in Harris (1981: 40–7).

13 As argued in Harris (1981) and (1985), the experiencer is the initial subject in the inversion construction. This

is the sense of “subject” intended here.

14 Old English had a construction traditionally called the impersonal, similar to the inversion construction of

Georgian, where the experiencer occurred in the dative case and the stimulus conditioned subject-verb agreement

(see van der Gaaf 1904).

15 Actualization may involve more than extensions; sometimes it may include a further reanalysis (HC, 80–1).

16 In the Caucasus, in addition to languages of the Indo-European and Turkic families, one finds languages of

three indigenous families: North East Caucasian, North West Caucasian, and Kartvelian. Although many attempts

have been made to show a genetic relationship among these three, no one has presented evidence that was at all

convincing. One recent work, Nikolaev and Starostin (1994), has adduced evidence that does convince some

linguists of a genetic relationship between North East and North West Caucasian (but not Kartvelian). Georgian is a

member of the Kartvelian family and is unrelated to Aγul, a North East Caucasian language.

17 The change described here is also not likely to have resulted through any sort of indirect contact, since it has

not, to my knowledge, occurred in other languages of the area.

18 All Aγul data presented here are from Kibrik (1979–81). I apologize for the violent content of some examples;

alternative examples with minimal constrasts are not available.

19 The generalization of word order is based on the observation that speakers treat the experiencer as a subject,

as in a number of other languages (Harris 1984).

20 This is a form of translation that has become traditional for this Old High German construction (see Paul 1949:

334, etc.).

21 In Dieninghoff's corpus, the early texts in which eigan and haben occur only as main verbs are Isidor, the

Interlinear-Version der Benediktiner-Regeln, Murbacher Hymnen, Monsee-Wiener Fragmente, and the

Weiβenburger Katechismus (1904: 38, 59). Zieglschmid (1929: 56) gives a similar list. Together with the evidence

adduced below, this suggests that reanalysis occurred in the tenth century, recognizing that it probably occurred

at different times in different dialects.

12/11/2007 03:39 PM

16. Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 19 of 19

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918

at different times in different dialects.

22 The perfect with sein was probably reanalyzed earlier than that with eigen and haben. This probably accounts

for the fact, noted by Maurer (1926: §49), that in any given period a higher percentage of haben than of sein

precedes the lexical verb. The position following the lexical verb is, in German, the position assigned to an

auxiliary. The fact that sein took over this position ahead of haben (both did so gradually) suggests that the

former was the first to be reanalyzed.

23 Oubouzar (1974: 12) implies that neither inflection on participles nor participial negation with un- is found in

her corpus after Notker's work, dated to the eleventh century.

24 Dieninghoff (1904: 38, 57) notes that eigan fails to appear either as an auxiliary or as a main verb in Tatian's

and Williram's works.

25 A complete study of the haben/ eigan perfect would include a more careful consideration of the changes in the

place of this construction in the tense/aspect/mood system of the language and of its relation to similar

constructions, such as Oubouzar (1974) provides. A complete treatment would examine the gradual

implementation of the reanalyses considered here. The present chapter is not the place for a complete study of

that kind, and instead my purpose is to extract those portions that provide a basis for comparison with other

languages.

Cite this article

HARRIS, ALICE C. "Cross-Linguistic Perspectives on Syntactic Change." The Handbook of Historical Linguistics.

Joseph, Brian D. and Richard D. Janda (eds). Blackwell Publishing, 2004. Blackwell Reference Online. 11 December

2007 <http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/tocnode?

id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747918>

Bibliographic Details

The Handbook of Historical Linguistics

Edited by: Brian D. Joseph And Richard D. Janda

eISBN: 9781405127479

Print publication date: 2004

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

17 Functional Perspectives on Syntactic Change

25 Psycholinguistic Perspectives on Language Change

A Perspective on ISO C

a relational perspective on turnover examining structural, attitudinal and behavioral predictors

Perspectives on Garden Histories

Cross linguitic Awareness A New Role for Contrastive Analysis

Perspectives on Garden Histories 2

A Perspective on ISO C

14 Grammatical Approaches to Syntactic Change

A post representational perspective on cognitive cartography

Conflicting Perspectives On Shamans And Shamanism S Krippner [Am Psychologist 2002]

A Perspective on Psychology and Economics

Phillip G Zimbardo A Situationist Perspective On The Psychology Of Evil Understanding How Good Peo

Perspectives on Garden Histories 2

an analyltical perspective on favoured synthetic routes to the psychoactive tryptamines j pharm biom

więcej podobnych podstron