14 Waterfront archaeology in British towns

Gustav Milne

Records of the discovery of timber or stone wharves were

published over 160 years ago (eg Laing 1818, 5-6), but the

wide-ranging concept

and the actual term ‘waterfront

archaeology’ are recent additions to urban studies. The

subject was effectively launched in London in 1979 at an

international conference in which it was shown that water-

front archaeology was not myopically concerned with the

form of ancient quays. Since almost any definition of towns

must refer to the importance of trade (Heighway 1972, 8-9;

Hodges 1982, 20-5) it was suggested that a study of the

development of the harbour area as a whole could provide

graphic evidence of,

and suggest reasons for a town’s

origins, growth or decline. The first review of waterfront

archaeology was published by the CBA as recently as 1981

(Milne & Hobley 1981) and covered work in nineteen

British towns. This paper will therefore summarize, analyse

and augment the information presented in that volume

rather than simply duplicating it.

Waterfront excavations of varying size have recently been

conducted in many towns, including:

Bristol

(Ponsford 1981; Williams 1981; Medieval Archaeol,

26, 1982, 168-70, Figs 1 & 2)

Caerleon

(Boon 1978; Boon 1980)

Cambridge (Medieval Archaeol, 18,

1974, 199)

Cardiff

(Webster 1977)

Dover

(Rahtz 1958; Rigold 1969; Philp 1980 & 1981)

Dublin

(Wallace 1981)

Durham

(Carver 1974)

Exeter

(Henderson 1981)

Gloucester

(Hurst 1974; Rowbotham 1978; Heighway &

Garrod 1981)

Hartlepool

(Young 1983)

Harwich

(Basset 1981)

Hull

(Ayers 1979, 1981)

Ipswich

(Wade 1981; Medieval

Archaeol, 26, 1982, 208)

Kirkwall

(McGavin 1982)

King’s Lynn

(Clarke & Carter 1977; Clarke 1981)

Leith

(CBA 1981, 103)

Lincoln

(Jones & Jones 1981; Medieval Archaeol, 27, 1983,

188)

L o n d o n

(Bateman & Milne 1983; Hobley 1981; Miller

1977, 1982; Milne

& Milne

1979, 1981 & 1982; Schofield

1981; Tatton-Brown 1974)

Norwich

(Carter 1981;

Ayers

1983; Ayers & Murphy 1983)

Oxford

(Durham 1977; Durham

1981; Medieval Archaeol,

26, 1982, 204-5)

Perth

(CBA 1982, 89)

P l y m o u t h (Medieval Archaeol, 13, 1969, 264,

Fig 80;

Barber & Gaskell-Brown 1981)

Poole

(Horsey 1981)

P o r t s m o u t h

(Fox 1981)

Reading (Medieval Archaeol, 26,

1982, 173)

Southwark

(Sheldon 1974; Dennis 1981)

Staines

(Crouch & Shanks 1980)

Westminster

(Green 1976; Mills 1980)

Woolwich

(Courtney 1974, 1975)

York

(Richardson 1959; Addyman 1981, 1983;

Medieval

Archaeol, 27, 1983, 209-10)

In addition, waterfront excavation has been argued as a

priority in towns such as Boston (Harden 1978, 36), Great

Yarmouth (Rogerson 1976, 43) and Newcastle (McCombie

& O’Brien 1983), and for various towns in the south-west

including Axbridge, Bridgwater, Minehead, Watchet,

Ilchester and Langport (Aston & Leech 1977, 169).

Waterfront reclamation

The first result of the recent work is the realization that the

waterfront of many riparian or coastal towns has been arti-

ficially extended. This phenomenon is both widespread and

of major topographical significance. Although a pioneering

paper on the extension of the King’s Lynn waterfront was

published in 1973 (Clarke 1973) the possibility that other

English towns may have had a similar development was

initially overlooked by students of urban topography (cf

Barley 1976). Medieval waterfront reclamation has now

been demonstrated by excavation in many British towns

including Bristol, Dublin, Exeter, Harwich, Hull, Ipswich,

King’s

Lynn,

Lincoln,

London,

Middlesborough,

Plymouth, Poole, Portsmouth and York. Roman waterfront

reclamation has been less extensively studied. However, the

evidence from Dover (Philp 1981) and London (Bateman &

Milne 1983) (Fig 89) seems to suggest that it too could have

been widespread.

Documentary, cartographic or topographical evidence has

been used to suggest areas of reclamation in several towns

such as Dartmouth (Martin 1980), Gloucester (Heighway &

Garrod 1981) and Newcastle (McCombie & O’Brien 1983).

Reclaimed land can often be readily identified on the

ground. If a town is built on a hill with a steep slope down

to the river, then

a

level terrace extending from the foot of

the hill to the present day river bank may well represent an

area of artificial encroachment. Examples of this may be

seen at Newcastle, where a number of narrow lanes or chares

descend the steep cliff edge to the level quayside terrace

running 60-100m to the River Tyne; or at Rye where the

Strand terrace now occupied by magnificent 18th and 19th

century timber-clad warehouses extends from the foot of

The Mint/Mermaid Street to the present-day quay on the

River Tillingham. Where towns have been built on more

level sites, then the reclamation zone is often found between

a sinuous street laid out over the original river bank, and the

present-day channel of the river. The area between the High

(or Hithe) Street and the River Hull in Kingston-upon-Hull,

and the area between the line of King, Queen and Nelson

Streets and the River Ouse in King’s Lynn are two well

known examples.

The motivation for extensive urban waterfront recla-

mation (eg Fig 90) has been discussed in a recent paper

(Milne 1981) in which it is suggested that it is possible to

distinguish between developments designed to win land; to

provide deep-water berths; to overcome the problems of

silting or to maintain a sound frontage. Such distinctions are

192

Milne: Waterfront archaelolgy in British towns

193

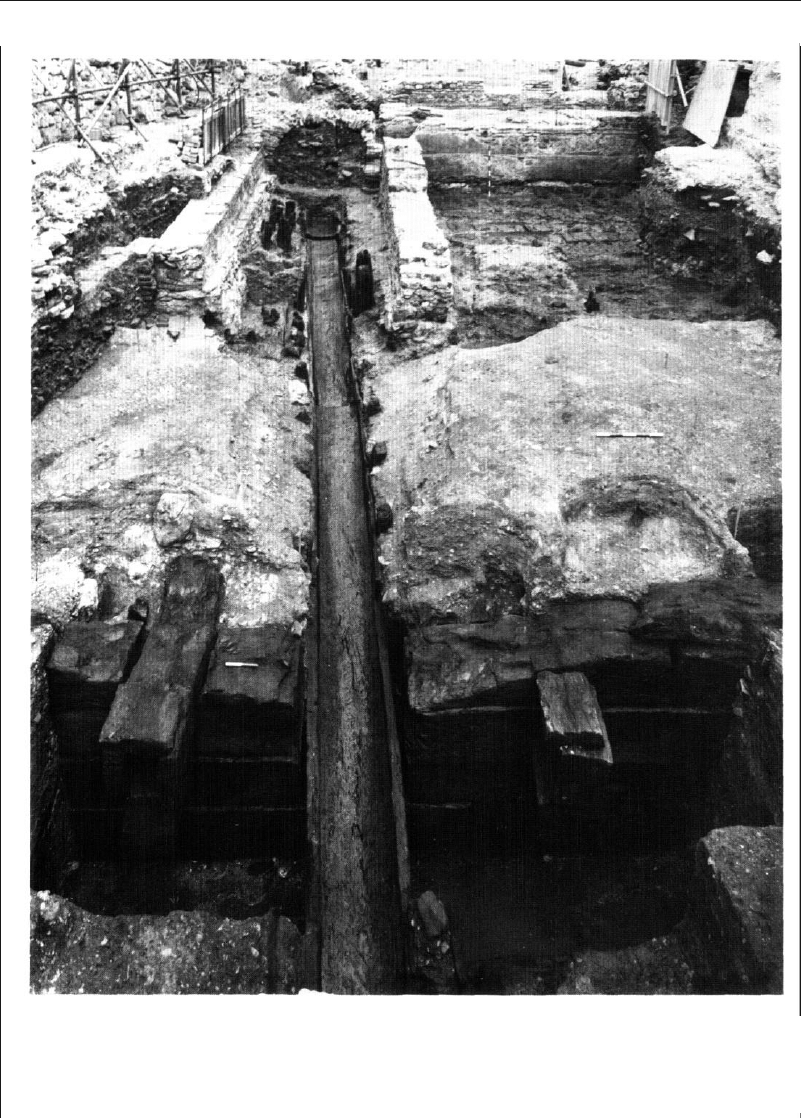

Fig 89 Late 1st century timber-faced quay surviving to its full height with open-fronted warehouse to the north, showing the

remarkable preservation and deep stratification found on a London waterfront site (Pudding Lane, 1980) (Museum of London)

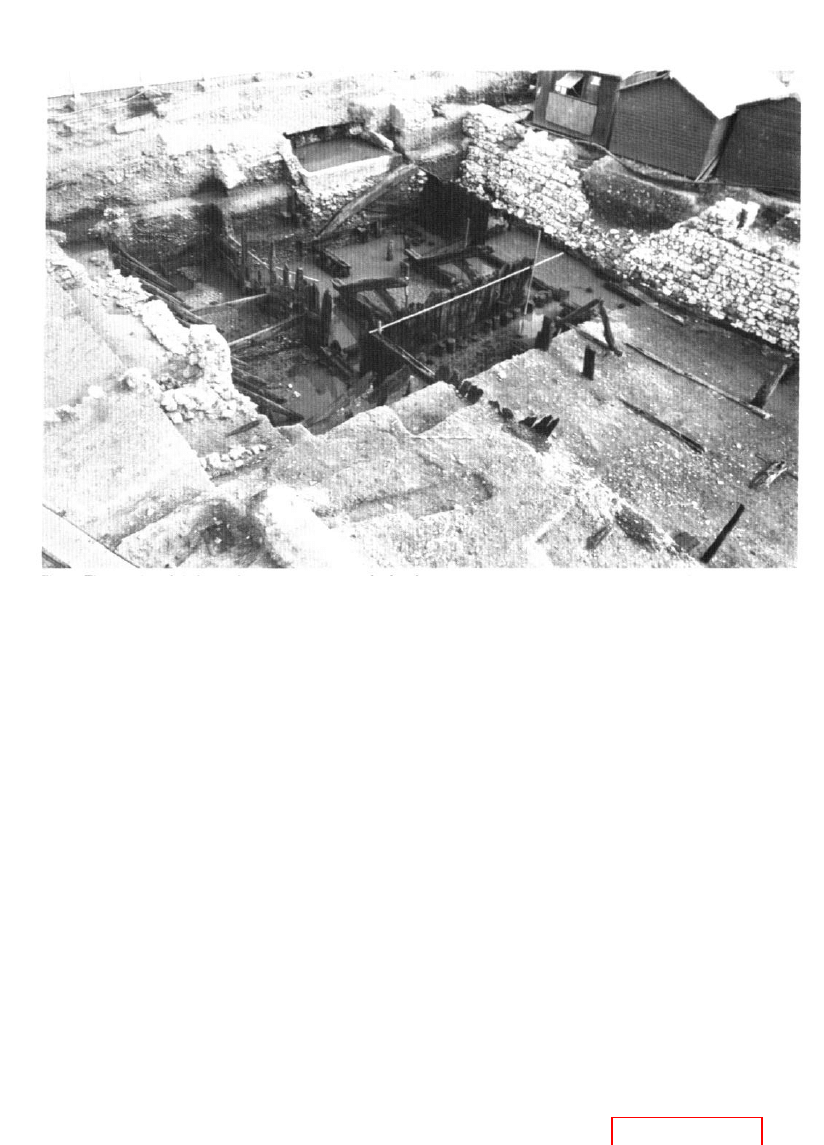

Fig 90 The remains of timber and stone revetments on the foreshore mark successive stages in the advance of London's medieval

waterfront (from left to right) at the Trig Lane sire, 1974-6 (Museum of London)

necessary if the correct implication of the extension for the

growth of the town is to be drawn.

Waterfront reclamation is not only of considerable

interest topographically but is also significant in a wider

archaeological sense, for the reclamation zone provides a

remarkable archive of deeply stratified, well preserved,

waterlogged deposits. These are often rich in environmental

evidence, and may contain large artefactual assemblages

including organic material such as leather and wooden

objects not usually encountered on 'dry' archaeological

sites.

Waterfront structures

British urban waterfront excavations have also produced

examples of Roman, Saxon, and medieval wharves and

revetments. The major Roman sites were at Caerleon,

Dover and London (Fig 89), but earlier work in other British

towns has been summarized by Fryer (1973), and Cleere

(1978). The early medieval waterfront has been examined in

Dublin, Ipswich, London, Norwich, Oxford and Poole,

while later medieval timber or stone wharf or revetment

structures have been recorded in at least seventeen British

towns: Bristol, Dublin, Exeter, Harwich, Hull, Ipswich,

King's Lynn, Lincoln, London, Hartlepool, Plymouth,

Poole, Reading, Southwark, Staines, Westminster and

York. Timber revetments have also been revealed on rural

sites, such as the moated manor at Stretham in Sussex

(Medieval Archaeol, 22 (1978), 18l-2). A number of other

features associated with the waterfront have also been

studied, including bridges at Beverley (Medieval Archaeol,

25 (1981), 216-18, fig 7); Exeter; London (Milne 1982b);

and Oxfordshire (Medieval Archaeol, 25 (1981), 225;

Medieval Archaeol, 26 (1982), 205); landing stages and jetties

at Driffield, Harwich and London (Milne & Milne 1982,

42-7); fish weirs on the Trent (Salisbury 1980, 88-91); and

a royal dockyard at Woolwich (Courtney 1974, 1975). The

remains of mills have been located on urban and rural water-

front sites at Batsford, Sussex (Bedwin 1980); Glasgow

(Medieval Archaeol, 26 (1982), 222); Bordesley Abbey

(Medieval Archaeol, 25 (1981), 188; 26 (1982), 185); and at

Waltham, where the wheel-pit and associated features were

initially thought to represent part of a wharf (Huggins 1972,

81-9).

The study of the construction and structural development

of waterfront structures is of interest in its own right (Milne

1979), but an assessment of the woodworking and carpentry

techniques and joinery recorded on waterfront sites also has

a much wider significance (Fig 91). Firstly, it often provides

closely dated examples of ancient carpentry. The complex

bridle-butted scarf joint from the revetment erected in c

1380 at Trig Lane, London is the earliest surviving joint of

its type, for example (Hewett 1980, 267).

Secondly, it enables characteristics of the vernacular

carpentry of a particular period to be identified and assessed

even when few or even no examples of that date are known

to survive above ground. In Dublin, Wallace has attempted

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Barrett J C Ko I A phenomenology of landscape A crisis in British landscape archaeology

Archaeology in Albania 1991 1999

List of Words Having Different Meanings in British and American English

Waterfront archaeology and vernacular

Augmenting Phenomenology Using Augmented Reality to aid archaeological phenomenology in the landscap

LECTURE 5 Christianity in the British Isles

Legg Calvé Perthes Disease in Czech Archaeological Material

Phoenicia and Cyprus in the firstmillenium B C Two distinct cultures in search of their distinc arch

Foreign Archaeological Missions Working in Cyprus

The Nature of Experiment in Archaeology

Insoll configuring identities in archaeology The Archaeology of Identities

LECTURE 6 ATTACHMENT 1 Business entities in the British Isles

Deep water Archaeological Survey in the Black Sea 2000 Season

British Patent 19,426 Improvements in the Construction and Mode of Operating Alternating Current Mot

LECTURE 4 ATTACHMENT 4 Courtroom criminal trial in the British Isles

British Patent 19,420 Improvements in Alternating Current Electro magnetic Motors

0415226767 Routledge Fifty Key Figures in Twentieth Century British Politics Sep 2002

więcej podobnych podstron