movie monsters

1

The Psychological Appeal of Movie

Monsters

Stuart Fischoff, Ph.D., Alexandra Dimopoulos, B.A., François Nguyen, B.A.

California State University Los Angeles

Media Psychology Lab

and

Rachel Gordon

Executive Editor, Journal of Media Psychology

Online Publication Date: August 25, 2005

Journal of Media Psychology, Volume 10, No. 3, Summer, 2005

movie monsters

2

ABSTRACT

A nationwide sample of 1,166 people responded to a survey exploring choices for

a favorite movie monster and reasons why a monster chosen was a favorite. The sample

was comprised of equal but culturally diverse numbers of males and females. Ages

ranged from 16 to 91. Results of the study indicated that, for both genders and across age

groups, the vampire, in general -- and Dracula in particular -- is the king of monsters..

With a few exceptions (women found vampires and the Scream killers more sexy and

ranked the demon doll, Chucky, significantly higher than males), males and females were

generally attracted to the same monsters and for similar reasons. As predicted, younger

people were the more likely to prefer recent and more violent and murderous slasher

monsters, and to like them for their killing prowess. Older people were more attracted to

non-slashers and attracted for reasons concerned with a monster's torment, sensitivity,

and alienation from normal society. While younger people also appreciated the classic

film monsters such as Frankenstein and King Kong, a parallel cross-over by older

respondents for more recent monsters, like Michael Myers, was not reciprocated.

Overall, though, monsters were liked for their intelligence, superhuman powers and their

ability to show us the dark side of human nature.

movie monsters

3

The Psychological Appeal of Movie Monsters

The open secret of why films have been so popular for over 100 years, in venues

ranging from the 2-dimensional, black and white, silent films viewed on five-inch screens

of the turn-of-the-century nickelodeons to the 21

st

century, stories-high, 3D IMAX

screens which fully immerse audiences in the booming high fidelity, color-saturated

action, may lie less in cinematic technology than in what film does for its viewers. Film

appeals to viewers' appetites for an extraordinary, vicarious experience, and the

convulsion of emotions that it so often delivers.

Given previous results of research on differential viewer reactions to films from

differing film genres (cf., Fischoff, 1997, Kaplan and Kickul, 1996), different film genres

may be expected to provide different vicarious and emotional experiences. In the case of

horror films, it is believed to be the thrill of fright, the awe of the horrific, the experience

of the dark and forbidden side of human behavior that lures people into the dark mouth of

the theater to be spooked (cf., Zillmann, Weaver, Mundorf, and Aust, 1986).

According to statistics provided by the online archives of the industry newspaper,

Variety, of the 250 or so top grossing films released by the American film industry each

year, approximately 15 films (6%) are of the horror genre. Numerous academics and non-

academics have written extensively on the topic of horror films, movie monsters, all-time

scary films, and the like. Some, like Michael Apter (1992) and his theory of detachment

and parapathic emotions, have looked at theoretical reasons why people seem to enjoy the

ostensibly negative experience of being frightened by a movie experience. According to

Apter, potential for escape into safe distance is paramount. Others, like Zillmann et al.,

(1986), for example, have looked at why horror films are good "date" movies or, like

Jonathan Crane (1994), have outlined how the horror genre has changed over the years,

evolving into a type which is far more violent and explicitly bloody. Researchers like Ed

Tan (1996) have demonstrated that film emotions are not ersatz stepchildren of authentic

emotions. Rather, film-induced emotions are themselves real experiences because the

film, in collusion with the audience eye and audience desire to be transported, can fool

the brain. In other words, a horror film can be “really scary” -- if we allow it!

movie monsters

4

Since the early part of the 20

th

century, when the horror film genre was born,

scary movies have developed into different clusters of themes. Silent film era horror

films, primarily European, were a mixed bag of legends and science fiction (e.g.,

Metropolis (1926), Nosferatu (1922), The Golem(1920), Edison's Frankenstein short

(1910), and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919)). Following the era of silent films came

the now-legendary era of the sympathetic monsters of the 1930's, as exemplified by

Universal Studio’s monster triumvirate, Frankenstein, Dracula, and the Mummy, and

their spin-offs and sequels. According to Crane (1994), these monsters were generally

seen as misunderstood outcasts from society, to be pitied, and even occasionally, as with

Dracula, found to be attractive. Audiences are said to have identified with these monsters

that were portrayed as existing on the outside of the normal community. Perhaps the

monsters’ onscreen plights tapped into audience feelings of social inequity and

recollection of social torment at the hands of their social peers.

The 1950s was awash in science fiction-fantasy monster pictures addressing such

things as science run amok, fear of alien invaders (The Thing [From Another World],

1951, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, 1956) and the disastrous and unanticipated

consequences of radioactive fallout (e.g., Them, 1954 and Godzilla, 1956). The late

1950s brought a new wave of monsters directed toward a different audience than those

who sought out monsters in the earlier decades. The new audience was the youth market,

and the monsters and their monstrous behaviors addressed the sensibilities of young

males and females. According to Skal (1993), this transition from multi-generational

appeal of films in general, and of horror films in particular, to a principally youth-

oriented market developed as the buying power of the young began to increase in the late

1950s. Beside youth oriented dramas like Rebel Without A Cause (1955), the angst of

adolescence was further explored with films like I Was A Teenage Werewolf (1957) and I

Was A Teenage Frankenstein (1958). Here, the monsters were not “the other” but, “us,”

possibly in all our adolescent hormonal rage and confusion. Filmmakers Roger Corman

and Sam Arkoff, among others, opened up a treasure trove of box office dollars by

appealing to this hungry market of young filmgoers and the youth-oriented film market

made its move to become the 800 pound behemoth it is today.

movie monsters

5

Hollywood, helped by the collapse of the old Hayes or Motion Picture Code in the

1960s, issued itself the license to shock, titillate and nauseate. This was coupled with

advances in the technology of special effects, and assured that the old tradition of almost

sanitary, often unseen horror, and gradual, enveloping, suspense was traded in for a new

tradition of horror, one of shock and blood-drenched gore, all to the delight of this

bulging youth market (Baird, 2000; Crane, 1994). Extremism in the pursuit of the

monster box office by monsters on screen became a mantra, not a vice. It is no wonder

that the cinematic vehicles for these emerging horror icons ran with blood, guts, and free-

standing heads and limbs. "The central focus are scenes that dwell on the victim's fear

and explicitly portray the attack and it's aftermath" (Weaver & Tamborini, 1996, p.38).

The slasher movie had arrived. Examples of slasher killers include Michael Myers from

Halloween (1978), Freddy Krueger from A Nightmare on Elm Street (1985) and

Leatherface from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974).

As horror films became more gruesome, more explicit, more horrifying than

terrifying, more shock than suspense, the older audiences began to stay away in droves.

According to research by Fischoff (1998), a trend could be observed: as viewers age,

their appetite for violence decreases and their attraction to the new, bloodier horror genre

decreases as well. A momentum begins and, in response, Hollywood shifts from

targeting adult market audiences to targeting primarily teen market audiences. Box office

goals dictate that such movies increasingly and violently focus on the plights of young

people, thereby further alienating middle age and older moviegoers, and further locking

the horror genre into what has become the youth culture juggernaut.

Film monsters have proven to be such unforgettable characters that in many

instances they have become part of our culture. Most Americans would recognize a

picture of Frankenstein, Dracula, King Kong, Godzilla or the Mummy before recognizing

a Supreme Court Justice. Like so many popular culture figures, these monsters have

become such recognizable icons, either through novel characterizations and product

merchandising, or through repeated film presentations on TV or via home video. But this

phenomenon is not exclusive to monsters from older films. Freddy, Jason, and Michael

have made their bid for fright “immortality.”

movie monsters

6

These newer slasher monsters are very different from cinematic horror monsters

of the past. As social climates, film technology, and local and national film policies

changed, so did monsters, in form, behavior and sensibilities. Are changes always

welcome? Are these changing monster types appealing to some groups and not to others?

Cowan and O’Brien (1990) found that in slasher monster films, the slashers are primarily

men, and sexy women were more likely to die than non-sexy women. Males on the other

hand, were targets for death if they possessed negative masculine traits (their sexual

allure didn’t matter).

One might expect that females would be put off more by slasher monsters than

males because women are punished for being sexual while men are merely punished for

being arrogant, pushy, or selfish, suggesting an implicit equation between female

sexuality and negativity. Yet, Fischoff (1994) found that although females and males do

not differ in their attraction to the horror film genre, they do differ in their attraction to

violence, males liking violence in movies more than females do. Are females less

attracted to violent movie monsters as well?

Further, does age matter? Do people of different ages wax nostalgic about

different monsters? If so, why? In other words, what makes horror monsters attractive

and what makes them unattractive, to different age groups, to different genders? It is

likely the case that, when analyzing people’s attraction to the “stars” of this genre called

Horror, one size does not fit all. If people are attracted to movies because of what

emotions it invites in them, what biographic resonances it incites (Fischoff, 1978), what

vicarious payoffs are meted out, it would be of interest to students of the genre as well as

filmmakers who keep the genre’s pipeline gurgling and churning.

Sadly, there is little empirical research on what or who are people’s favorite

monsters and what reasons underlie such affections. No study of which the present

authors are aware has systematically sampled a national population for their individual

preferences on these movie monster matters. This study was designed to explore our

favorite monsters and why we feel connected to them. It also sought to explore the

following research questions and hypotheses derived from the abundant but solely

speculative literature on horror movies and movie monsters.

Hypotheses:

movie monsters

7

H

1

. Young people will prefer more recently conceived movie monsters while

older people will prefer vintage film monsters.

H

2

. Young people will prefer film monsters that are more violent and disposed to

killing large numbers of people than will be older people.

H

3

: Young people, rather than older people, will be more likely to prefer film

monsters that are attractive because of their killing inclinations.

H

4

: Males will prefer more violent movie monsters than Females.

Research Questions:

RQ

1

. What are the favorite film monsters?

RQ

2

. Do males and females differ in terms of the specific monsters they find

favorites?

PROCEDURE AND METHODOLOGY

Members of the Media Psychology Lab

1

at California State University, Los

Angeles under the direction of the first author conducted a year-long, nation-wide survey

of (among other things) the preferences people have for certain movie monsters. Data

collection took place between September 2000 and August 2001. A variety of direct and

indirect contact venues were employed to garner responses from academic and

nonacademic settings. This resulted in a cross-sectional, convenience sample of 1,166.

This included 597 females, 567 males, and two individuals who withheld gender

information.

The participants ranged in ages from 6 through 91 with a mean age of 34.2. The

total number of people who were classified as “young,” (25 years or younger), “middle”

(26-49 years) and "older"(50+) is 531, 371 and 253 respectively. The sample, therefore,

is skewed toward younger respondents. These three age range categories were found to

be highly effective for comparing age groups in previous research on film preferences (cf.

Fischoff, 1998). For those respondents who filled out the long version of the survey, the

age distribution was even less representative of those over 50 (n = 38), further attenuating

1

We would like to thank Ana Franco, Angela Hernandez and Leslie Hurry for

their assistance on this research.

movie monsters

8

the proportionate presence of older respondents in our sample. Respondents came from

the four major racial/ethnic groups, Caucasian, Asian, Hispanic and African-American.

Ethnicity was included to assure sample representativeness rather than as an intended

independent research variable.

The survey questionnaire was developed over a number of open-ended pilot

studies to elicit a range of items addressing reasons for individual monster preferences

2

.

People were asked to respond to potential monster preference reasons on a 4-point Likert-

type Scale ranging from 0 (no influence) to 3 (very influential). The final survey

contained 43 closed-ended reasons for liking a monster. In order to collect more data on

favorite movie monsters citations when people did not have the time to fill out a long list

of reasons behind the selection, a short version of the survey was designed and

administered in rapid response street interviews.

Slasher Monsters

For purposes of specific hypothesis-related analyses, all monsters cited by

respondents were classified into one of two categories: slasher or non-slasher. The

operational definition of a slasher monster in the present study was that it was portrayed

on screen as a serial or mass murderer, motivated by some deluded or self-justifying

revenge or outrage. It was also necessary that the murders committed by the monster

generally were unrelated to the monster’s actual survival needs (e.g., vampires and blood

needs). Further, a slasher monster should be portrayed as generally experiencing no

remorse for its murderous rampages. Monsters that murdered for reasons such as fear,

survival, or procreational needs and were not necessarily mass murderers, were classified

as non-slashers.

Examples of familiar slasher monsters are Freddie Krueger from A Nightmare on

Elm Street series of films, and Chucky, the demon doll from the Child’s Play series.

Examples of familiar non-slasher monsters are Frankenstein, Dracula and Gill Man from

the Creature From the Black Lagoon film series.

2

The survey also looked at scariest films. That data will be presented at a later

date.

movie monsters

9

The determination of a monster as a slasher or non-slasher was derived from

judgments and assessments of film monsters by academics authors such as Crane (1994),

Pinedo (1993), Twitchell (1985), and Cowan & O’Brien (1990), comments obtained

during pilot studies, and the judgments and observations of the research team. Two

members of the research team decided into which category a monster would fall and, if

no agreement was obtained, a third team member helped decide the classification. In

95% of the cases, there was no such disagreement. Of the 1, 038 monsters cited, the total

number of monster citations falling into the slasher category is 290 while 748 fall into the

non-slasher category,

χ

2

(1, N = 1,038) = 202.1, p < .001.

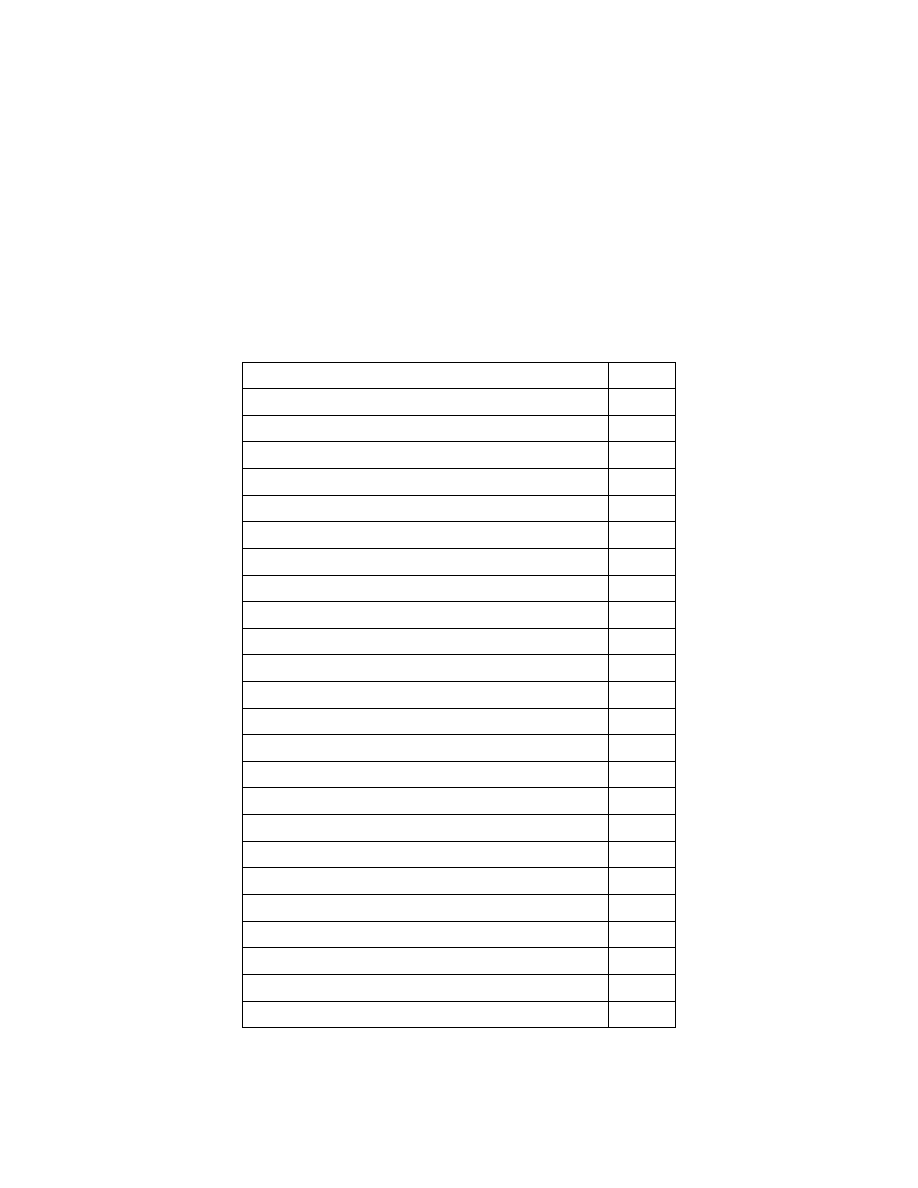

Adapting a data reduction procedure employed by Wilkins (2000), an additional

classification of the 43 reasons for a monster being a favorite was used for ease of

interpretation. Forty-two of the 43 reasons were collapsed into 9 Scales. The number of

the scales, their rank in terms of frequency of citation, and their meaning, are presented in

Table 1. Reasons were placed in scale categories on the basis of shared dimensions of

surface meanings. For example, there are two items which comprise the Self-Reference

Scale (Scale 1): Reason 2 (“monster reminds me of myself”) and Reason 36 (“I first

experienced the monster as a child”). Of particular interest in the present study and its

hypotheses, Scale 6, Dimensions of Killing, contained nine items with reference to such

reasons as “monster enjoys killing” (Reason 11) and “monster kills lots of people”

(Reason 14).

movie monsters

10

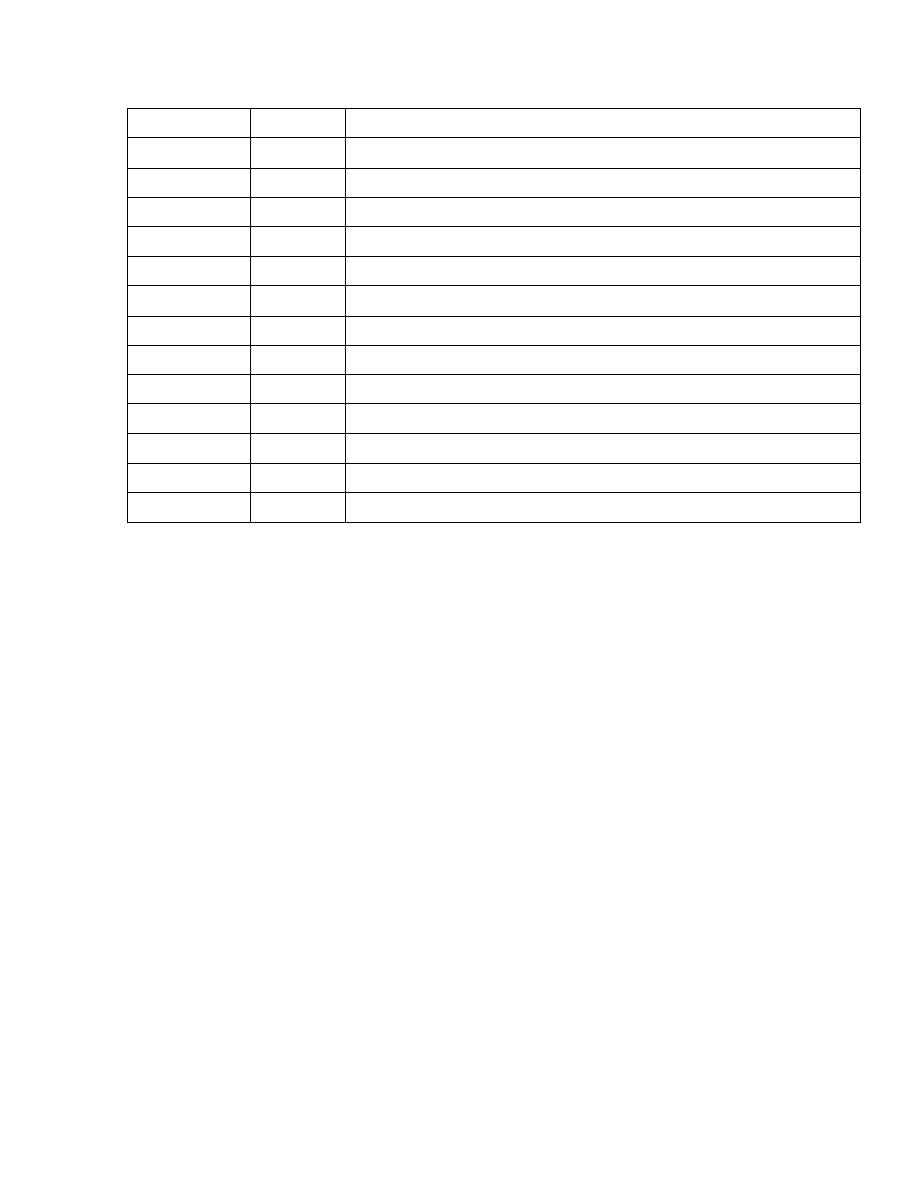

Table 1.

Reasons and Rankings for Monsters Being Favorites

All Monsters

Scale

Number

Rank Scale

Meaning

1

9

viewer autobiographic reference

2 4

monster's

appearance

3 3

positive psycho-social

characteristics of monster

4 1

negative psycho-social

characteristics of monster

5 6

supernatural

powers

6

5

dimensions of killing

7

7

enlightenment provided by monster

8 8

sex/romance/attractive

9

2

empathy, pity, compassion for

monster

For analytic purposes, each respondent’s score on a scale was the sum of the

scores on each of the reasons comprising the scale. Recall that each reason could range

in score from 0-3. Using reason sums allows for comparisons between monsters on each

scale, but not for comparisons between scales because scales varied in number of

component reasons. The number of items comprising a scale ranged from 2 to 9.

RESULTS

Data was collected from a respondent pool of 1,166. However, as only a subset of

this total answered the long form of the survey with the 43 reasons, the N for analysis of

reasons why a person liked a particular monster was limited to 700 survey protocols

while the tally of favorite monsters is based on an N of 1,034.

movie monsters

11

Favorite Monsters

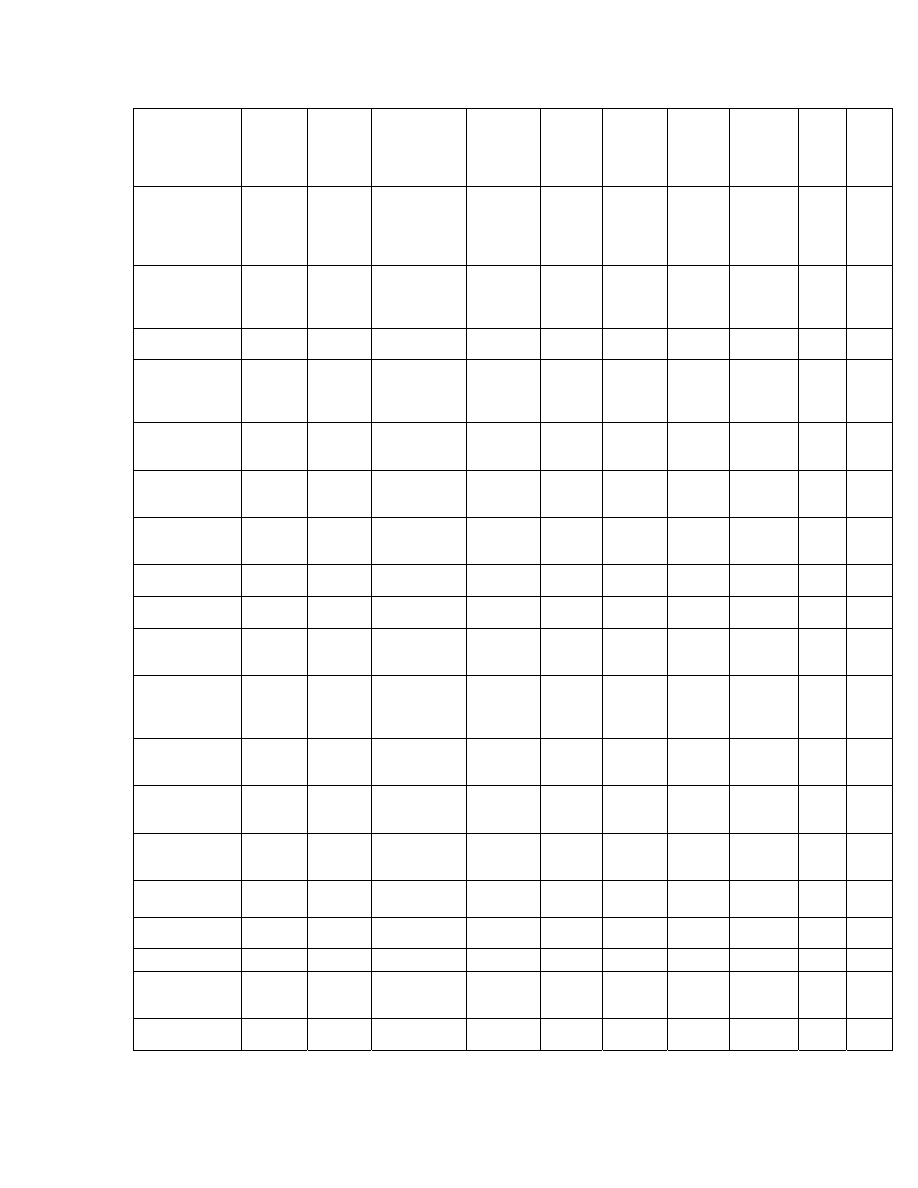

Tables 2, 3, and 4 contain, respectively, the “Top 25” favorite monsters for All

Respondents, for Males and Females separately and for Young, Middle and Older

Respondents separately.

Table 2.

Frequency Citations for “Top 25” Monsters for All Respondents

All Respondants

Monster

Rank

Vampires (Dracula)

1

Freddy Krueger

2

Godzilla 3

Frankenstein 4

Chucky 5

Michael Myers (Halloween)

6

King Kong

7

Hannibal Lecter

8

Jason Voorhees (Friday 13

th

) 9

Alien (Alien series)

10

Exorcist girl (Linda Blair)

11

Scream killers

12

Predator 13

E. T.

14

Mummy 15

Darth Vader

16

Shark from Jaws

17

It (The Clown)

18

Jack Nicholson (The Shining)

19

Werewolf 20

Blob 21

Gill-Man (Creature From the Black Lagoon)

22

The Thing

23

Beast (Beauty and the Beast)

24

Candyman 25

movie monsters

12

All Respondents

There were 205 different, favorite individual movie monsters cited ranging from

Freddy Krueger, Frankenstein, and the Werewolf to facetiously nominated outliers such

as Shelley Winters, Barbra Streisand, and Michael Jackson. Ten percent (132) of

respondents reported no favorite movie monster. Of that number, 78 were female (60%)

and 54 were male (40%). Thus, 6.7% of females and 4.6% of males had no favorite

monsters,

χ

2

(1, N = 1,166) = 3.63, p< .06. While previous research (Fischoff, Antonio,

and Lewis, 1997) has shown that females and males do not significantly differ in terms of

preference for films of the Horror genre, results from this study suggests that they do

differ in terms of likelihood of having a favorite movie monster.

Age and Vintage of Favorite Monster

H

1

predicted that young people will prefer more recently conceived movie

monsters while older people will prefer monsters of an earlier vintage. The correlation

between the average age of the respondent selecting a monster and the year that the film

introducing the monster was initially released (or, if the there were many sequels, the

average year of release of the sequels) is r = -.63, p < .001; as the monster film’s release

year increases, the average age of the respondent selecting it decreases, supporting H

1

.

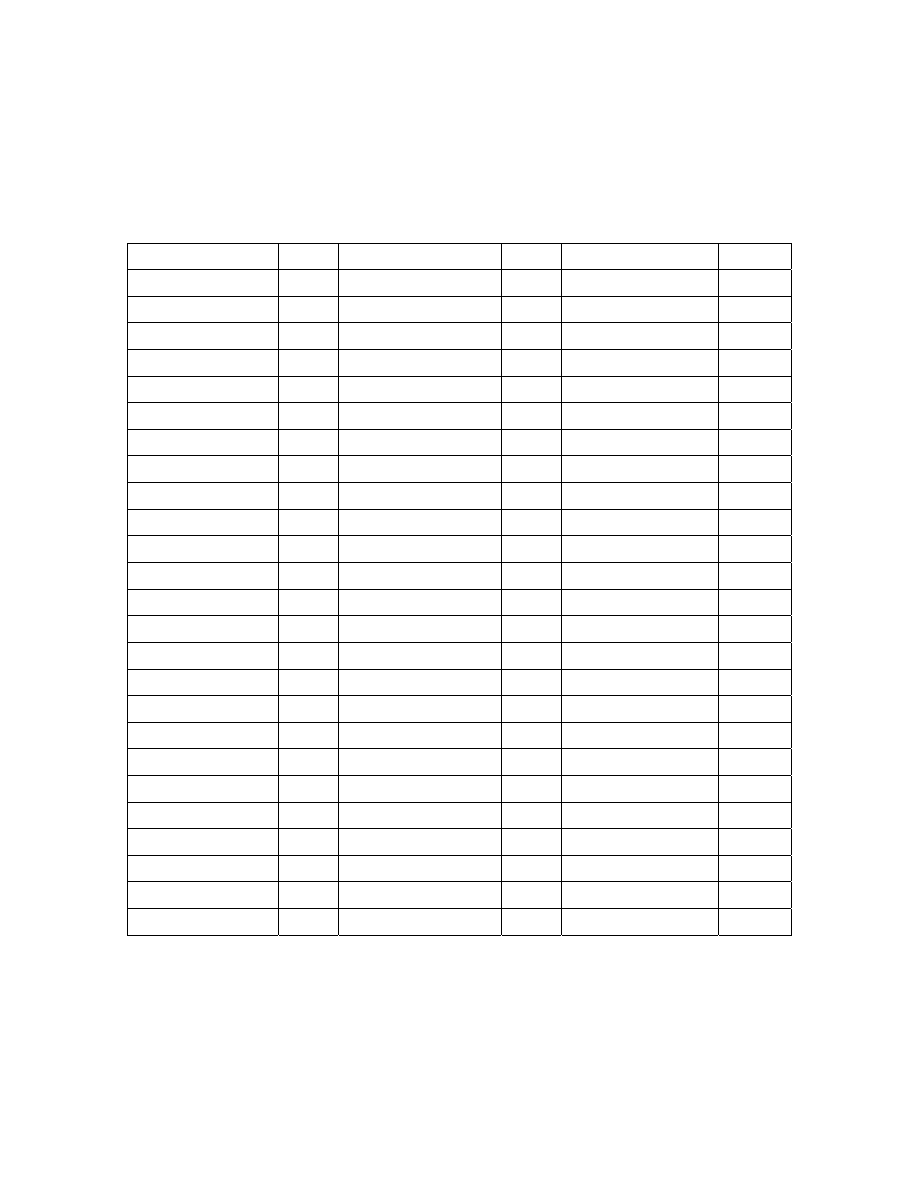

Taking another angle of regard and looking more closely at the 25 most favorite

monsters in terms of citations frequencies, Table 3 contains data arranged according to

the average or mean age of respondents selecting one of these monsters, as well as the

standard deviation of the age mean. The monsters are ranked from the lowest mean age

of respondents selecting them to the highest mean age.

movie monsters

13

Table 3.

Mean Age of Respondents Choosing Individual Monsters

Monster

Mean Age of

Selecting

Respondents

SD

Film Source

Release Year

Scream killers

s

18.4 4.9

1996

It (The Clown)

s

19.7 2.9

1990

Candyman

s

20 2.3

1992

Chucky

s

21.9 6.5

1988

Michael Myers

s

22.7 5.5

1986

Exorcist Girl

24.2

10.6

1973

Freddy Krueger

s

24.6 8.8

1989

Jason Voorhees

s

25.8 11.9

1987

Hannibal

s

28.8 12.8

1996

Predator

s

29.5 12.6

1988

Darth Vader

29.6

13.7

1980

Jaws shark

32

8.9

1975

Beast (Beauty and the Beast) 33.1

20.7

1991

Werewolf (Chaney)

33.5

17

1941

Vampire (Dracula-Lugosi)

33.6

16.7

1931

Godzilla (Japanese)

34.3

14.7

1975

Alien Creature

35.6

13.2

1982

Terminator 36.9

18.1

1988

The Thing

37.1

16.3

1951

Mummy (Karloff)

39.9

21.9

1932

Blob (The Blob) 40.6

16.3

1958

E.T. 44.1

15.9

1982

Frankenstein (Karloff)

44.3

20.5

1933

Jack Nicholson (The Shining) 46.4

14.8

1980

Gill-Man (Black Lagoon) 48.9

18.1

1954

King Kong

52

18.1

1933

s = slasher monster

It is clear that, with minor exceptions, monsters from the 1980s and 1990s

dominate the top or younger domain of the list, and monsters from the 1930s through the

1950s, again with minor exceptions, occupy the bottom or older domain of the list. In

other words, younger respondents, who dominated the sample, were partial to more

movie monsters

14

recent vintage movie monsters while older people, who were in the minority of the

sample, were partial to earlier vintage movie monsters.

Looking at the adjacent standard deviation (SD) statistics (degree of dispersion of

individual scores around the mean of all the scores) in Table 3, another trend emerges.

The five monsters which topped the list (Scream Killers, It [The Clown], Candyman,

Chucky, Michael Myers) fall into the slasher monster category. These slasher have both

the lowest average age (ranging from 18.4 to 22.7) of respondents selecting them, and the

lowest SDs (e.g. SD = 2.9 when compared with a mean of 44.3 and a SD of 20.5 for

Frankenstein). By contrast, the more classic non-slasher monsters have yielded data with

higher average ages but also have larger SDs. The implication here is that earlier, more

classic Hollywood monsters have a broader age appeal than do later Hollywood

monsters.

Monster preferences by respondents in the Middle Age range show the broadest

generational straddle, finding monsters from the ‘30s to the ‘80s very appealing but, with

the exception of Hannibal Lecter, finding few ‘90s monsters with any appeal.

Monster and Violence

Age and Monster Violence

H

2

predicted that young people will prefer more violent, slasher-type monsters

than will older people. Results provide strong and consistent support for this prediction.

As predicted, 45.4% of younger people cited monsters classified as slashers while the

figures were 21% and 9.7% for Middle and Older people respectively,

χ

2

(2, N = 1,034) =

104.59, p < .001. Each age group was significantly different from each other and in the

expected direction.

movie monsters

15

Table 4.

Frequency Citations for “Top 25 Monsters for All Age Groups

Young

Middle

Older

Monster Rank

Monster Rank

Monster Rank

Freddy Krueger

1

Vampires

1

Vampires

1

Vampires 2

Godzilla

2

Frankenstein

2

Chucky 3

Frankenstein

3

King

Kong

3

Michael Myers

4

Freddy Krueger

4

Godzilla

4

Godzilla 5

Alien

5

E.

T.

5

Jason Voorhees

6

Shark from Jaws

6

Mummy

6

Hannibal Lecter

6

King Kong 7

Jack

(The

Shining)

7

Exorcist Girl

8

Jason Vorhees

8

Gill-Man

7

Scream Killers

9

Hannibal Lecter

9

Alien

7

Frankenstein 10

Michael

Myers 10

Freddy

Krueger

10

It (The Clown)

11

Chucky

10

Hannibal Lecter

10

Predator 12

Predator 10

Blob

10

Candyman

13

Jack (The Shining)

10

The Thing

10

Mummy 14

E.

T.

10

Jason

Vorhees

14

Darth Vader

14

Blob

10

Werewolf

14

Beast (Beauty and) 14 Darth

Vader

16 Predator

14

Alien 17

Werewolf

17

Exorcist

girl

14

Werewolf 18

Mummy

17

Darth

Vader

14

King Kong

19

Gill-Man

19

Beast (Beauty and)

14

E. T.

19

Exorcist girl

19

Michael Myers

0

The Thing

19

The Thing

19

Chucky

0

Shark from Jaws

22

It (The Clown)

22

Shark from Jaws 0

Gill-Man 22

Beast

(Beauty

and)

22

Scream Killers

0

Jack (The Shining) 24 Scream Killers

24

Candyman

0

Blob

24

Candyman

25

It (The Clown)

0

Gender and Monster Violence

When it comes to gender, results were opposite to that predicted in. It was

predicted in H

4

that males would prefer the more violent and rapacious movie monsters,

the slashers as it were. Surprisingly, results show that females, not males, cited the

movie monsters

16

higher percentage of slasher movie monsters, 34.5% compared with a male citation

percentage of 27.9%,

χ

2

(1, N = 1,034) = 5.23, p < .02. This is a complete reversal of

prediction.

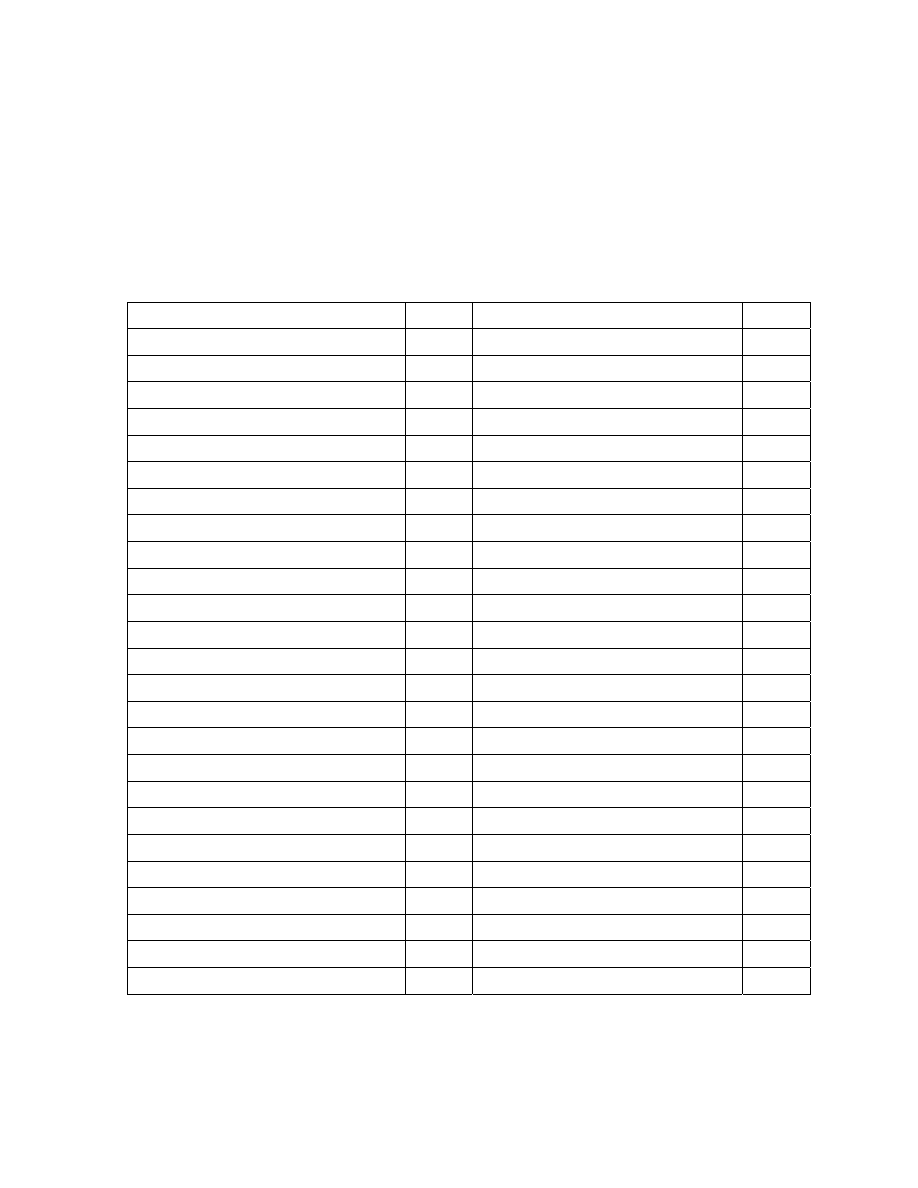

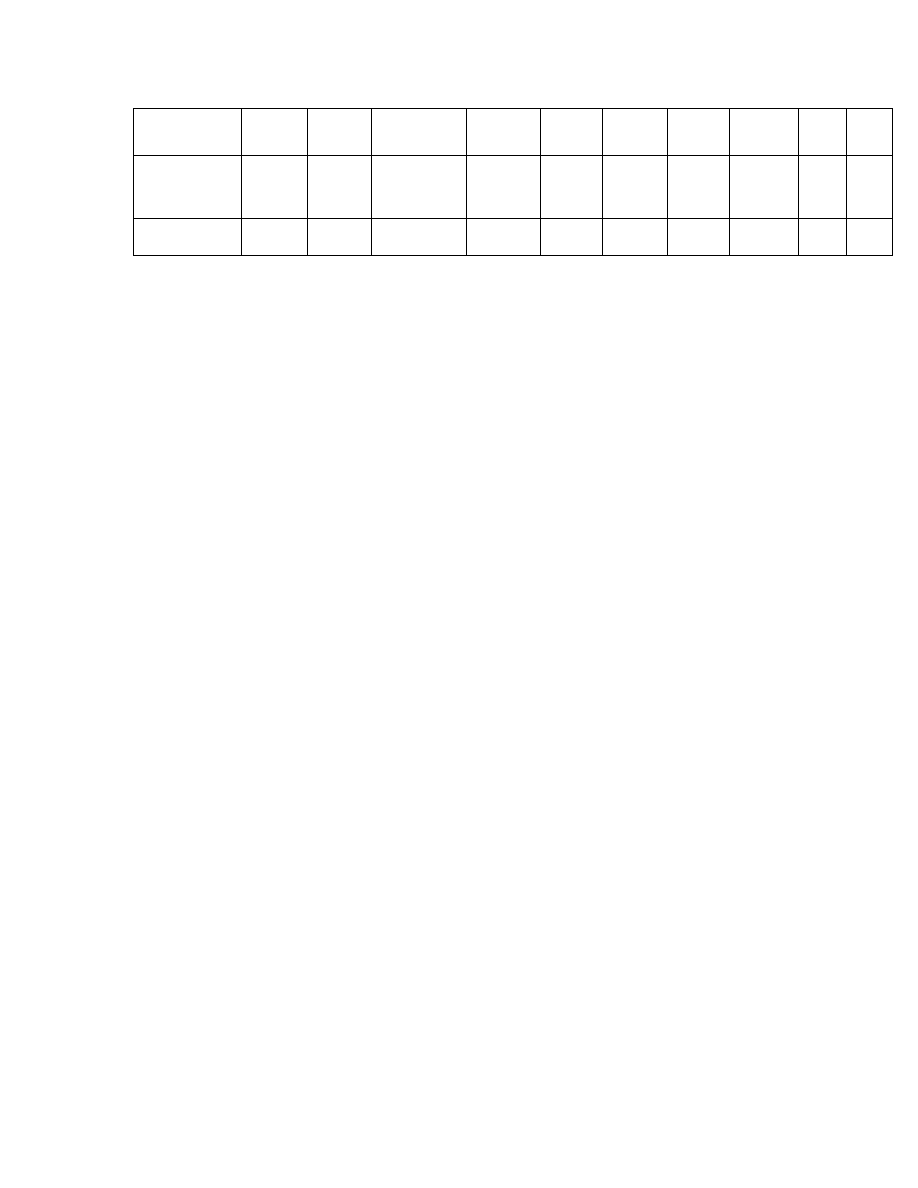

Table 5.

Males and Female “Top 25” Monster Rankings Based on Citations

Frequencies

Monsters Cited - Males

Rank

Monsters Cited - Females

Rank

Vampires 1

Vampires

1

Godzilla 2

Freddy

Krueger

2

Frankenstein 3

Godzilla

3

Freddy Krueger

4

Chucky

3

King Kong

5

Frankenstein

5

Michael Myers

6

Hannibal

6

Alien 7

Michael

Myers

7

Jason Voorhees

8

Exorcist girl

7

Hannibal 9

Jason

Voorhees

9

Predator 9

Scream killers

10

Darth Vader

11

King Kong

11

Chucky 12

E.T. 12

Mummy 12

Alien 12

Jack (The Shining) 14 It

(Clown)

14

Exorcist girl

14

Mummy

15

Jaws 16

Beast

(Beauty and) 15

E.T. 16

Jaws

17

The Thing

16

Werewolf

18

Werewolf 19

Predator 18

Gill Man (Black Lagoon) 19

Candyman

18

Blob 19

Blob

18

Scream killers

22

Jack (The Shining) 22

It (Clown)

22

Gill Man (Black Lagoon) 22

Candyman 24

Darth

Vader

24

Beast (Beauty and) 25 The

Thing

24

Similar gender results are obtained when viewed from a slightly different angle.

Table 5 shows the top-ranked monsters cited by males and females. The Spearman rank

movie monsters

17

order correlation for male and female rankings of Top 25 Monsters is significant, r

s

= 68,

p < .001. Males and females essentially tallied similar lists of favorite monsters with

minor exceptions in terms of the ranking of certain monsters, specifically Chucky (ranked

4

th

for females and 12

th

for males) and Regan, the possessed girl in the original Exorcist,

played by Linda Blair (ranked 7

th

for females and 14

th

for males). Furthermore, females

were about 40% more likely to mention vampires than males and twice as likely to

mention killers from Scream.

But, other than shifts in rankings, males and females were effectively in

agreement when it came to favorite monsters. H

4

- females will prefer less violent

monsters than males - seems to have found no support. Moreover, in response to RQ2,

“do males and females differ in terms of the monsters they find favorites?” The answer

appears to be not much.

What differences there are between males and females may be more readily found

when looking at reasons for selecting a monster as a favorite.

Rationales Behind Favorite Monster Choices: Scale Scores

Space limits a detailed presentation and discussion of the nine scale variables

developed for the present study. Focus will be confined principally to Scale 6,

Dimensions of Killing. H

3

predicted that, compared with older people, younger people

will be more likely to prefer film monsters that are attractive because of their killing

inclinations. Results cited above concerning H

2

established that there is essentially a

negative relationship between age and preference for very violent film monsters such that

as age goes up, preference for violent, murderous film monsters goes down. But as to the

reasons for preferring a monster, comparisons between genders and between age groups

are instructive.

Gender

Scale 6 of the 9 scales developed for analysis of reasons concerns all items

concerned with reasons underlying dimensions of killing, e.g., monster enjoys killing,

kills many people, kills deserving people, etc. ANOVAS reveal significant differences

between age groups and genders in scores on this scale. Males were significantly more

likely to favor monsters because of their killing capacity than were females, t (577.5) =

1.99, p < .05. Males had a mean score on Scale 6 of 9.83, SD = 5.82 while females had a

movie monsters

18

mean score of 8.91, SD = 5.94. Thus, although females were somewhat more likely to

prefer monsters that were classified as slashers, they were somewhat less likely to prefer

them for their wide range of killing parameters as expressed in Scale 6. Instead, women

were more likely to prefer monsters because of positive psycho-social characteristics

(Scale 3), e.g., monster has a sensitive side or shows compassion.

Age

Regarding age, an ANOVA for age on Scale 6 yielded a statistically significant

effect for age, F( 2,687)= 13.55 p < .001. A post hoc comparison of significance of

differences between Young, Middle and Older age group means supports the hypothesis,

M

young

= 10.07, SD = .27, M

middle

= 8.33, DF = .42, M

older

= 6.09, DF = .86. Each age

group is significantly different from each other at alpha levels greater than .05. Thus, age

and preference for a monster because of the variety of ways and the variety of types of

people it kills were, as predicted, inversely related. Hence data support prediction of H

3:

young people prefer monsters more for their dimensions of killing than do older people.

Slashers and Non-Slashers

Looking the data in terms of how citers of slasher and non-slasher monsters

scored on Scale 6, results indicate that, as might be expected, persons who selected

slasher monsters, such as Freddy Kreuger or Michael Myers, had significantly higher

scores on the Dimensions of Killing scale than those who selected non-slashers, such as

Dracula or Godzilla. Slasher citers obtained a mean score on Scale 6 of 12.27, SD = 4.35

while Non-Slasher choosers had a mean score of 7.84, SD = 6.03, t(627.8) = 11.01, p <

.001.

Rationales Behind Favorite Monster Choices: Reason Scores

All Monsters

Table 6 contains an overall rank ordering of reasons why a monster was chosen

as favorite. Ranking was derived from computing the mean of all respondents rating of

that reason as it applied to their monster choice. The top five reasons have nothing

explicitly to do with degree of monster murderousness. Rather, the qualities of

intelligence, superhuman strength, embodying pure evil, not being inhibited or morally

constrained, and showing us the dark side of human nature, garner the most appeal.

Thus, a theme running across most monster preferences concerns issues regarding evil,

movie monsters

19

absence of moral inhibition, and an exploration of the dark side of human nature. Only in

later reasons offered do we find dimensions of killing to be of primary importance. But,

for young men, recall, this is an extremely potent rationale.

Table 6.

Rank Ordering of Reasons for a Monster Being a Favorite

Mean Rank

Code

Meaning

2.08 1

superhuman

strength

1.97 2

very

intelligent

1.84

3

monster is pure evil

1.8

4

monster is not inhibited or morally constrained

1.79

5

shows us dark side of human nature

1.78

6

monster enjoys killing

1.74

7

monster never ages or dies

1.74

7

monster is an outcast

1.7 9

looks

realistically

horrifying

1.64

10

monster kills lots of people

1.64

10

monster kills good people

1.61

12

monster acts out of self-protection or rage

1.6

13

monster has serious psychological problems

1.59

14

never know who monster is going to kill

1.57

15

monster has own subculture

1.57

15

monster has a sense of humor

1.52

17

helps us understand evil

1.48

18

I enjoy being frightened and this monster really frightens me

1.45

19

helps us understand insanity

1.44

20

monster is misunderstood by society

1.42

21

monster has a sensitive side

1.41

22

can't control his violence

1.33

23

monster can disguise its evil ways

1.3

24

monster can alter his/her body shape

1.3

24

monster can take control of victim's minds

1.16

26

like different ways monster kills people

1.14

28

I like what the monster wears

1.01

29

monster consumes human flesh/blood

movie monsters

20

1

30

monster is compassionate

0.99

31

reflects ancient myths

0.93

32

monster can fly or levitate

0.87

33

monster can become invisible

0.87

33

monster can read a person's mind

0.8

35

turns victim into monster

0.75

36

monster reminds me of myself

0.71

37

reassures me there's life after death

0.71

37

monster is sexy, charming

0.69

39

can have sex whenever he/she wants

0.67

40

kills deserving teenage males

0.65

41

kills deserving teenage females

0.55

42

experienced it first as a child

0.42

43

like the way monster uses humans for reproduction

Reasons by Gender

Male and female participants answered with similar reasons as to why a monster

was their favorite. When analyzed by multiple t-tests, in only three instances were

significant differences revealed. But three reasons out of 43 being significantly different

could have easily occurred by chance and only one of the three reasons was related to

violence while the other two dealt with identification. Males were more likely to explain

their selection of Godzilla (M

males

= 1.15, M

females

= 0.25, t(691) = 3.42, p<.001). and

King Kong (M

males

=1.71, M

females

= 0.43, t(691) = 2.14, p<.05) because they felt the

monsters “reminds me of myself.” As regards reasoning related to violence, Chucky was

selected by males more often than females because “I like the way the monster kills

people” (M

males

= 2.67, M

females

=1.00, t(691) = 6.5, p<.001). All other monster

comparisons showed little difference or no discernible pattern of differences in selected

reasoning among males and females. Consequently, Hypothesis 4 predicting that males

would be less attracted to monsters that were violent than would females was not

supported by the present data.

movie monsters

21

Reasons by Age

Hypothesis 3 predicted that young people would prefer film monsters for

different, more violent reasons, than older people. Four items address the issues

surrounding killing or dimensions of killing: Monsters enjoy killing, monsters kill lots of

people, monsters kill deserving teenage males, and monster kills deserving teenage

females. Results of an ANOVA of the mean of the sum of these four variables supports

the prediction. In contrast to respondents of middle and older age ranges, younger

respondents find a monster attractive because of the numbers of people it kills and who in

particular it kills to a significantly greater degree F(2,683) = 11.29, p < .001. A post hoc

analysis revealed the differences between Older (M = .77) and Younger (M = 1.24) to be

significant and that between Younger and “Middle” (M = .96), to be significant. The

differences between Older and Middle, while in the predicted age direction, were not

statistically significant. Older people, by contrast, found reasons of social rejection and

alienation to be the bulwark for their monster preferences.

Reasons by Individual Monsters

Table 7 displays the mean scores on all 43 reasons for the Top 10 Favorite

Monsters. Recall the scores o each reason can range from 0 to 3. Any mean score less

than one would indicate that that reason was not particularly important in that monster

being considered a favorite. Hence, data discussion will generally be restricted to reasons

with mean scores above 1.

movie monsters

22

Table 7

Mean Reason Scores* for "Top 10" Favorite Movie Monsters

Reason

Vampire

N = 134

Freddy

Krueger

N = 87

Frankenstein

N = 61

Jason

Voorhees

N = 29

Michael

Myers

N = 37

Godzilla

N = 75

Chucky

N = 39

Hannibal

Lecter

N = 30

King

Kong

N

=34

Alien

N =

26

turns victim

into monster

2.24

0.49 0.29 0.4

0.16

0.22 0.75 0.56 0.23

1.1

monster

reminds me of

myself 0.95

0.46

0.79

0.43 0.25 0.68 0.28 0.84

1.07

0.47

reassures me

there's life

after death

1.26

0.72 0.68 0.9

0.62

0.49 0.97 0.24 0.08

0.27

monster is

compassionate 1.33 0.28

2.25

0.4 0.28 1.2 0.59

1.08

2.5

0.33

monster is

pure evil

1.72

2.54

0.66

2.5 2.75

1.31

2.56 2.12

0.54 1.73

monster never

ages or dies

2.48

2.19 0.79 2.7 2.47

1.93

2.47

0.68 0.85

1.33

monster has

own subculture

2.39

1.24 0.54 1.1

1.19

1.56 1.22 1.44 0.92

2.13

monster has a

sensitive side

1.97

0.49

2.25

0.4 0.42

1.74

0.78

1.68 3

0.6

Monster has a

sense of

humor 1.5

2.17

1.61 0.75

0.38

1.22

2.19

1.96 1.9

0.33

monster is not

inhibited or

morally

constrained

1.9

2.12

1.18 0.95

1.97

1.54

2.06 2.28

1.77 1.5

monster

enjoys killing

1.69 2.35

0.64

2.55 2.53 1.8

2.53 2.44

0.62 1.47

Monster is

sexy, charming

1.86

0.26 0.07 0.2 0.5

0.41 0.22 1.12 0.62

0.33

like different

ways monster

kills people

0.96

1.81

0.39

2.1 1.56

1.05 1.31 1.48

0.46 1.44

monster kills

lots of people

1.53

2.28

0.61

2.85 2.64 1.78

2.37

1.76 1.1

1.6

kills deserving

teeage

females 0.76

1.26

0.14

1.5

0.97 0.68 0.84 0.32 0.23

0.33

kills deserving

teeage males

0.72

1.25

0.39

1.45

1.06 0.71 0.81 0.4 0.46

0.33

superhuman

strength

2.36

2.15 1.79 2.55 2.47 2.32 1.91 0.84 2.15

2.4

monster can

become

invisible 1.19

1.25

0.5 1.1

0.5

0.41

0.47 0.4 0

0.27

helps us

understand

evil 1.77

1.25

1.5

1.8 1.41

1.22

1.62

2.08

1.1 1.2

helps us

understand

insanity 1.28

1.81

1.32 1.95

2.13

0.88

1.97

2.24

0.62 0.87

movie monsters

23

shows us

where science

and

technology can

go wrong

0.78

0.87

2.14

0.6 0.56

2.02

1.44 0.64

1.23

1.94

I enjoy being

frightened and

this monster

really frightens

me 1.46

1.96

0.86 1.8

2.25

1.32

1.94

1.6 0.85

2.1

monster has

serious

psychological

problems

1.32

2.29

1.21 2.2

2.75

0.78

2.43 2.36

0.62 0.6

monster kills

good people

1.72 1.9

1.03

2.25 2.15 1.5

2.37

1.6 0.77

1.82

monster

consumes

human

flesh/blood

2.33

0.91 0.29 0.6

0.28 1.02 0.56 2.56

0.23 1.13

monster can

alter his/her

body shape

2.23 1.76

0.36 0.45

0.13

0.66

1.19 0.36 0 1.8

never know

who monster is

going to kill

1.67

1.97

1.03

2.35

1.81 1.56 2.19 1.52 1.15

2.47

looks

realistically

horrifying 1.27

2.43

1.59 1.95

2.1

1.88 2.16 0.84 1.54

2.93

monster is an

outcast

1.84 2.13

2.21

1.8

2.41

1.88 2.22 1.46 2.15

0.73

can't control

his violence

1.84

1.09

2.1

1.25 1.41 2.1 1.41 1.16

1.54

0.87

monster is

misunderstood

by society

1.78

0.85

2.11

1.1 1.41

1.71

0.94

1.54

2.85

0.8

monster acts

out of self-

protection or

rage 1.57

1.62

1.66 2.1

1.69

2.38

1.97 1.44

2.37

1.47

monster can

disguise its evil

ways

2.1

1.26 0.43 1.15

0.84

0.8

2.25 2.24

0.38 0.6

can have sex

whenever

he/she wants

1.69

0.72 0.43 0.4

0.09

0.5 1.1 0.63 0

0.27

shows us dark

side of human

nature

2.28

1.99 1.43 1.85

2.66

1.24 1.94 2.36

1.31 1.1

experienced it

first as a child

0.5 0.41 0.71

0.3 0.28 0.83 0.47 0.52 0.77

0.27

reflects ancient

myths 1.8

0.66

0.57

0.95

0.66 1.17 1.03 0.48 1.15

0.47

very intelligent

2.55

1.74 1.1 1.81

1.69 1.46 2.25 2.76

1.69

2.33

monster can

take control of

victim's minds

2.26 2.18

0.32 1.1

0.34

0.59

1.88 1.88 0

0.47

monster can

fly or levitate

2.19

1.07 0.18 0.35

0.06

0.76 0.53 0.2 0

0.47

movie monsters

24

monster can

read a

person's mind

1.54 1.65

0.14 0.75

0.19

0.27

0.47 1.36 0

0.33

like way

monster uses

humans for

reproduction

0.69 0.35

0.27

0.35 0.09 0.29 0.63 0.28 0

1.53

I like what the

monster wears

1.97

1.22 0.25 1.15

1.81

0.54 1.44 0.79 0.33

0

The highest mean reason scores in each row are printed in bold. Suffice it to say

here that on matters concerning killing dimensions, slasher monsters generally score

highest, something already seen in the presentation of results regarding Scale Scores,

especially Scale 6.

Using highest scores in each column to provide a thumbnail characterization of

each monster’s most salient characteristics which contributed to their being a sample

favorite, interpretation of results suggest the following:

1. Vampires engage viewers most because of their intelligence and because they

never die or age. They are also the sexiest of all monsters, with Hannibal Lecter coming

in second. Vampires share another commonality with Hannibal, their taste for humans

although Hannibal is noted for sins of the flesh while Vampires drink -- not wine, but

blood.

2. Freddy Krueger, one of the slasher monsters, is principally highlighted as

“pure evil,” but a close second is that he is “realistically horrifying.”

3. Frankenstein scores high on compassion and sensitivity and the fact of is

being both an outcast and an example of where science can go wrong.

4. The most outstanding feature of slasher Jason Voorhees, of Friday the 13

th

is

that he is an unstoppable killing machine. His cornicopic feats of slicing and dicing a

seemingly endless number of adolescents and the occasional adult is impressive to his

fans. He scores the highest of all 10 monsters on all relevant killing variables comprising

Scale 6, with a mean score of 13.52. His closest rival is Freddy Krueger scores only

12.29 on this Dimensions of Killing variable. Considering that his body count does not

compare with those of Godzilla or the creature from Alien, it is an impressive

accomplishment to be effectively anointed the King of Killers. Jason’s audience appeal

movie monsters

25

is further abetted by his immortality, his apparent enjoyment of killing and by his

superhuman strength.

5. Michael Myers, of Halloween fame, is, like Jason Voorhees, a slasher monster

extraordinaire. While also the embodiment of pure evil, he also stands apart from others

in his highest score for serious psychological problems, M = 2.75. Michael’s closest

rivals are Chucky, M = 2.53 and Hannibal, M = 2.36. Why Michael is seen as more

troubled than Jason is not discernible from the data. That it may be related to his

witnessing his sister having sex in the introductory episode of this franchise, which

putatively led to his psychotic reaction and murder of his sister, is one possibility.

6. Godzilla’s most dominant features are that it acts out of self-protection or rage

and that it has superhuman strength and that, a result of atomic testing in the Pacific, is a

product of science and technology going very wrong. Its destruction of cities and its

inhabitants seems “understandable” in this light given her favorite status. Godzilla scores

third lowest in penchant for killing, higher only than King Kong and Frankenstein.

7. Another slasher monster, Chucky, the demon doll from the Child’s Play series,

was, it may be recalled, picked three times as often by females as males. Enjoying

killing, having serious psychological problems, and embodying pure evil are his principal

virtues for being a favorite. But, like some other monsters, such as Vampires, Hannibal

and Alien, Chucky is considered quite intelligent and appealing for that reason.

8. Hannibal Lecter, the most recently minted of the Top 10 monsters, lacks

totally any supernatural “gifts,” but his intellectual appeal is the highest of all, M = 2.76.

Likewise, because of his non-supernatural status, he provides his admirers with an

appreciation of the workings of an insane mind. His mean score on this reason of helping

us understand insanity is 2.24. Lecter’s closest rival on this variable was Michael Myers

whose mean score on this reason is 2.13. And, top scorer again, Hannibal is viewed as

the monster who is least morally inhibited or constrained. Thus, Hannibal’s

supernaturally unadulterated, sardonic cannibalism makes him a righteous target for

judgment about human failings. At the same time, such failings seem to be part and

parcel of his audience appeal.

9. King Kong is the king of the sensitivity and the recipient of the most pity. He

is rated as having the most Sensitive Side of all the 10 monsters, M = 3.0 is the Most

movie monsters

26

Misunderstood, M = 2.85 and the Most Compassionate, M = 2.5. He virtually ties with

Godzilla as having his violence justified because he acts out of self-protection and rage.

10. Finally, the creature from Alien is a favorite in large measure because one

never knew the monster was going to kill (“everybody” was usually a safe bet) and

because it was so horrifying looking, M = 2.93. Freddy Krueger’s score on this reason,

M = 2.43, was a distant second. Intelligence was also a strong point. So, intelligence,

unpredictability and sheer physical horrific all teamed up to place the lizard mother from

Alien in the current pantheon of movie monsters.

DISCUSSION

Previous research has shown that females are less likely than males to prefer

movies that show violence and gore. The present study found no evidence for consistent

and systematic differences between the genders in terms of monster choices. Therefore,

no support for our third hypothesis could be confirmed regarding greater or lesser

preferences for murderous monsters. Nevertheless, the study did find that females were

less likely to have a favorite monster than males. It may be that females, particularly the

younger women and those who did choose a monster and enjoy horror films, are just as

"blood thirsty" a cast of viewers as their male counterparts. Further research might

examine if other factors influence the responses of female subjects such as the presence

of a self-reliant, briefly victorious, female protagonist in the horror films chosen such as

Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley in the Alien series and the women who live to scream another

day in another film, in so many slasher horror films, women such as Jamie Lee Curtis in

Halloween I and II.

In terms of favorite monsters, most emphatically the fictional vampire species

in general, and Bela Lugosi’s Dracula in particular, is the king of the netherworld of

film monsters. This may be due to the timeless nature of the story as well as the

countless vampire remakes that have flooded cinema over the years and the popularity of

imitating Bela Lugosi. Moreover, F. W. Murnau’s Bram Stoker rip-off, Nosferatu,

notwithstanding, Dracula has most often been played by very attractive men who serve to

increase the sexual power of the character in prowess and romance. This has served to

boost the monster’s appeal for both men and women, although women, understandably

rated vampires significantly more sexy than did males, M

male

= 1.29, M

female

= 2.11,

movie monsters

27

t(49.2) =3.03 p < .001. In the Top 10 list of monsters, for all respondents, vampires were

rated as the sexiest (M = 1.86), followed a distant second by Hannibal Lecter (M = 1.13).

With high ratings on looks and brains, and an appeal to both men and women, it is

perhaps no wonder that the vampire (and Dracula especially) is the most popular movie

monster.

Why is a serial murderer like Dracula considered sexy and attractive?

Psychological research has reaffirmed conventional wisdom repeatedly in studies

showing that we are more ready to empathize with and excuse handsome or beautiful

people when they commit crimes than is our disposition when it comes to the non-

handsome, the non-beautiful defendants. (Stewart, 1980). We also tend to attribute more

positive personality characteristics to attractive people (Tesser, 1995). Even in

“monsterland,” it seems, it pays to be beautiful or handsome --and sympathetic! Recent

films on the Ann Rice literary creation, Vampire Lestat, prompt both sexual and

sympathetic responses from fans of her books and the derivative movies.

Vampires have an additional virtue … of sorts. As a western society, to a likely

neurotic degree, we fear aging and death and the Vampire character is ideally tempting in

both regards. He never ages and never dies completely. He also has supernatural powers

that may be appealing to those who feel powerless.

The results of our study support the hypotheses that younger moviegoers prefer

more recent horror film monsters and are far more partial to slasher monsters than are

older moviegoers. Results also support our hypothesis that younger viewers prefer a

newer generation of horror monster and, it may be surmised, a cinematic style and

storyline drenched in the sensational and novel forms of bloodletting and mortal dispatch

favored by the likes of Freddy, Michael, Jason and their brethren of evil. Slasher -

monster storylines place the acts of murder in the foreground. What little there might be

in terms of rationale for the seemingly endless orgies of death in which these films

commerce, is unceremoniously relegated to the background, as if to say, “Why ask why?”

Contemporary monsters might easily be considered psychopathic in their

bloodlust as they eschew even a scintilla of remorse. In other words, older monsters

struggled with their stature as deviants and killed for survival (Dracula), out of fear-

induced rage (Frankenstein), search for a loved one (Karloff’s Mummy) or, as with the

movie monsters

28

Wolf Man, bestial possession. This monster quartet, in their original film appearances,

often yearned for the deliverance of death. Indeed, according to Crane (1994), it was

Lugosi’s 1931 Dracula who uttered the plaintive lines “To die. To really be dead. That

must be glorious.”

But the modus operandi of contemporary monsters? Contemporary monsters

seem to kill because…they kill. Even though brief psychological explanations are given

in various modern slasher films, such as revenge against their original aggressors, they do

not seem to stand as important during the subsequent installments. These psychological

motivations, mentioned in the premier episodes of the series films seem obligatory rather

than substantive and frequently exercises no palpable influence on character motivation

or behavior. It is not surprising then, that in subsequent iterations of the movie

(sometimes called sequels), motivation for murder all but disappears.

These changes in film styles (quick, bloodless dispatch vs. explicit slaughter) and

reinvention of the formulae for character motivation (existential despair vs. sheer

nihilism) may reflect altering value trends in popular culture. Or, they may bespeak a

culture which itself was or is still reflecting social and political nightmares in

contemporary society, as has been argued by Crane (1994), Pinedo (1997) and Waller

(1987).

Yet, whether legendary horrormeisters such as George Romero, Tobe Hooper or

Wes Craven were (and are) speaking for a post-Viet Nam war, politically cynical

generation, as they have claimed in film interviews, or are merely people of a generation,

is a moot point. But the explicitness of their filmic violence in the 70s seemed to be

echoed in the 80s and 90s in other horror franchises series like Scream and the Hannibal

Lecter oeuvre, and in the explicitness of music lyrics, body adornments, piercings, and

the clothing styles for the culture of youth. Lecter continues to mimic the prevailing

culture of America, both civilized and savage. He looks, according to David Skal (1996),

very much like us. A monster for the millennium, Lecter wears his evil on the inside not

on his face. His disfigurement is spiritual, not physical. He is Jeffrey Dahmer meets

Norman Bates with a seductive panache of Wall Street’s Gordon Gekko.

For once, it seems, Hollywood got it right. The respondents in our survey saw

Lecter as pure evil; not evil in looks, but in deed and conscience. Thus, evil is the

movie monsters

29

charming gentleman next door, not the freak in the circus or the drooling psychotic off

his meds. In the tradition of Pogo, we’ve come to know the monster and the monster is

very often, us.

Lecter still carries on the tradition of Freddy and Jason. He kills for pique and

pleasure, gamesmanship, hunger and lust, not for moral outrage, self-protection or

persecution. He is remorseless and asks the viewer to share, or at least overlook his

peculiar tastes. Charm, Hollywood would have us believe, excuses almost everything.

Lecter’s insouciant airs make him a monster for the the 21

st

century and beyond—Id

incarnate. Greed is good and murder can be fun…and filling too. As Crane (1994)

would have it, “violence in the contemporary shocker is never redemptive, revelatory,

logical, or climactic (it does not resolve conflicts.)” (p. 4). Violence simply is.

There is clearly a cultural as well as generational gap between those under 25 and

those over 40. The horror films and favorite monsters reflect this gap. So did results

from research by Fischoff and his students on favorite film quotes (Fischoff et al, 2000),

which indicated that young people favored more violent and vengeful quotes from

movies than did older respondents.

CONCLUSIONS

In general, different monsters are adored for different reasons but, overall,

characteristics such as superhuman strength, intelligence, luxuriating in the joy of being

evil and being unfettered by moral restraints, are some of the most popular reasons

favored by the sample. Moreover, monsters are admired for holding a mirror up to our

darker sides and assisting us in understanding evil. Perhaps it is the evil that we fear

lurks in all of us, the evil that, in reality, dares not show its face or speak its name. But it

is an evil that does dare parade itself across the movie screen for our vicarious enjoyment

and delectation.

Beyond what a monster may show us about ourselves and our darker side, our

results indicate that what monsters must do above all is behave horrifically and evoke in

us extreme emotions, especially the adrenalized emotion of fear. Looking scary is useful

as well. Moviegoers also relish their monsters displaying such positive traits as

compassion, sensitivity, humor, and intelligence. Regardless of age, members of all age

groups in this study, in varying degrees, liked characters who were sympathetic because

movie monsters

30

of their afflictions and torments. Moreover, the supernatural powers that the monster

possesses are attractive. Our modern and classic literature and legends show that we

humans fantasize about having powers beyond the normal. Whether we’re rooting for

Superman or Dracula, good or evil, superhuman powers are an audience favorite.

It is worth noting that over 90% of the people who cited classic monsters who

were reprised in modern remakes, specified their favorites to be the original, not the

remakes. Remakes tend to disappoint. Remakes of films such as Godzilla, The Thing

and King Kong, for example, were each singled out for particular rejection by

respondents. The myriad of actors portraying Dracula over the decades once Bela

Lugosi’s star went into decline, including such notables as Jack Palance, Christopher Lee,

Frank Langella and, most recently, Gary Oldman, seemed to carry on the tradition of the

romantic vampire, but Lugosi’s Dracula was still the most frequently mentioned

incarnation.

A closing thought about the monster preferences of the young versus the older

viewer. Younger viewers do celebrate the riot of blood and dismemberment unleashed

by contemporary film monsters. But it must be noted that the more classic film monsters

have appeal across generations - an appeal far broader than the appeal of later monsters.

Modern respondents clearly like classic monsters. They like them almost as much as do

older respondents and, as evidence shows, for many of the same reasons: outsider,

misunderstood, sympathetic, frightened, and compassionate. Perhaps those qualities are

most exquisitely represented in the monster who is taken from his home, placed in an

environment he doesn’t understand and is brought to his iconic demise because of the

love for but not of a woman—King Kong. Kong is a monster with whom people of all

generations can identify and sympathize. And the youth of today is no exception.

Remarkably, though, it would appear that younger movie goers have another set

of criteria that they invoke for the modern movie monsters, the Freddys, the Michaels, the

Jasons: who they kill, how they kill, and how often they kill counts for a lot, and the

bloodier, the better.

This mass murderer dimension of monster appreciation is largely absent from the

metrics and aesthetics employed by older respondents. This may reflect a co-existing set

of preferences in younger minds that they handle easily, a set of tastes that straddle

movie monsters

31

generations of popular culture and film monsters. Jenkins (2000) offers the suggestion

that violent entertainment like this serves four functions for young people including

fantasies of empowerment, of transgression, intensification of emotional experience, and

acknowledgement that the world is not always a safe, friendly place. This youthful

juggling act, this plasticity of filmic preference, may both astonish and offend older

people but it’s one that younger people have come to find rather normal. Whether it

means something deeper and more disturbing about real life tolerances for rape and

murder and real life appetites of younger viewers for death sports and snuff films, is open

to speculation.

When these younger viewers approach middle age, whether they continue to find

such explicit violence and mayhem as appealing as they do now is another open question.

Research cited earlier suggests that time alters such appetites. But perhaps times have

changed and, like greed on Wall Street, a monster mired in murder, mutilation and

mayhem will remain an allure not to be outgrown but, rather, a timeless source of an

evening’s entertainment for the entire family.

movie monsters

32

REFERENCES

Apter, M. (1992). The psychology of excitement, in The Dangerous Edge, The Free

Press-Macmillan, New York,

Baird, R. (2000).The Startle Effect, Film Quarterly, Spring, p.p.1-18 ,

Cantor, J. (1994). Fright reactions to mass media, in Media effects: Advances in theory

and research, J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Erlbaum Publishing, Hillsdale, NJ,

pp. 213-245,

Cantor, J., & Oliver, M.B. (1996). Developmental differences in responses to horror, in

Horror films: Current research on audience preferences and reactions, J.B.

Weaver III & R. Tamborini, (Eds.), Erlbaum Publishing, Mahwah, NJ,

Cowan, G. & O’Brien, M. (1990). Gender and survival vs. Death in slasher films: A

content analysis, Sex Roles, 23: 3, p.p 187-196.

Crane, J. L. (1994). Terror and everyday life: Singular moments in the history of the

horror film, Sage Publishing,: Thousand Oaks, Ca,

Fischoff , S., Cardenas , E., Hernandez , A. Wyatt, K., Young, J. and Gordon, R. (August

2000). Popular movie quotes: Reflections of a people and a culture, Paper

presented at annual meeting of APA, Washington, D.C, ,.

Fischoff, S. (August, 1998). Favorite Film Choices: Influences of Beholder and the

Beheld, Paper presented at annual meeting of APA Convention, San Francisco.

Fischoff, S., Antonio, J., & Lewis, D. (August, 1997). Favorite films and film genres as a

function of race, age, and gender, Paper presented at annual meeting of APA,

Chicago.

Fischoff, S. (August, 1994). Race and sex differences in patterns of film attendance and

avoidance. Paper presented at annual meeting of APA, Los Angeles.

Jenkins, H. (Winter 2000). Lessons from Littleton: What Congress doesn’t want to hear

about youth and media, Independent School.

http://www.nais.org/pubs/ismag.cfm?file_id=357&ismag_id=14

(accessed

90/19/02).

Kaplan, M. & Kickul, J. (May, 1996). Mood and extent of processing plot and visual

information about movies, Paper presented at annual meeting of Midwestern

Psychological Association, Chicago,.

movie monsters

33

Pinedo, I. (1997). Recreational terror: Women and the pleasures of horror film viewing,

State University of New York Press, Albany, N.Y.

Sparks, G. & Miller, W. (1998), as cited in Purdue News,

http://news.uns.purdue.edu/uns/html4ever/981016.Sparks.films.html,.

Stewart II, J. E. (1980). Defendant’s attractiveness as a factor in the outcome of trials,

Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 10, p.p. 348-361.

Skal, D. (1993). The Monster Show: A cultural history of horror, W. W. Norton & Co.:

New York.

E. Tan, E., (1996). Emotion and the structure of narrative film, Erlbaum Publishing,

Mahwah:, N.J.

Tesser, A. (1995). Advances in social psychology, McGraw-Hill Publishing, New York,

N.Y.

Twitchell, J. B. (1985). Dreadful pleasures: An anatomy of modern horror, Oxford Press:

N.Y.

Waller, G. A. (1987). American Horror: Essays on the modern American horror film,

University of Illinois Press: Urbana, Ill.

Weaver, J.B , & Tamborini, R. (Eds. (1996). Horror film: Current research on audience

preferences and reactions, Erlbaum Publishing, Mahwah: NJ.

Wilkins, K. G. (2000). The role of media in public disengagement from political life,

Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44(4), pp. 569-580.

.Zillmann, D.,Weaver, J. B., Mundorf, N., & Aust, C. F. (1986). Effects on an opposite-

gender companion’s affect to horror on distress, delight, and attraction, Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 51, pp. 586-594.

.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Medical Psychology 4 effects of disease, IC, ATI

Presentation 5 Psychological Aspects of Treatment of the S

Alta J LaDage Occult Psychology, A Comparison of Jungian Psychology and the Modern Qabalah

Walęcka Matyja, Katarzyna; Kurpiel, Dominika Psychological analisys of stress coping styles and soc

LITTLEWOOD Bringing Ritual to Mind psychological fundation of cultural forms by R N McCauley

PSYCHOLOGICAL IMAGE OF MAN IN SAMUEL BECKETT`S NOVELS

Śliwerski, Andrzej Psychometric properties of the Polish version of the Cognitive Triad Inventory (

Do methadone and buprenorphine have the same impact on psychopathological symptoms of heroin addicts

EFF v DoJ Appeal of OLC Opinion Denied

Gitmo Detainees Win! Appeal of Forcefeeding End

Anti Semitism and the Appeal of Nazism

Carl Jung On The Psychology Pathology of So Called Occult Phenomena

A Tale of Two Monsters or the Dialectic of Horror The MA Thesis by Lauren Spears (2012)

Wack, Tantleff Dunn Relationship between Electronic Game Playing, Obesity and Psychological Functio

TRANSIENT HYPOFRONTALITY AS A MECHANISM FOR THE PSYCHOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF EXERCISE

Davison Socio Psychological Aspects of Grop Processes

The Appeal of Exterminating Others ; German Workers and the Limits of Resistance

Krauss Social Psychological Models of Interpersonal Communication

więcej podobnych podstron