ORIGINAL RESEARCH—WOMEN’S SEXUAL HEALTH

Impaired Sexual Function in Patients with Borderline Personality

Disorder is Determined by History of Sexual Abuse

jsm_1422

3356..3363

Olaf Schulte-Herbrüggen, MD,* Christoph J. Ahlers, MSc,

†

Julia-Maleen Kronsbein, MD,*

Anke Rüter, MSc,* Scharif Bahri, MD,* Aline Vater, MSc,* and Stefan Roepke, MD*

*Charité-University Medicine Berlin, Campus Benjamin Franklin, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Berlin,

Germany, EU;

†

Charité-University Medicine Berlin, Campus Mitte, Institute of Sexual Science and Sexual Medicine,

Berlin, Germany

DOI: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01422.x

A B S T R A C T

Introduction.

Patients suffering from a Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) display altered sexual behavior, such

as sexual avoidance or sexual impulsivity, which has repeatedly been linked to the sexual traumatization that occurs

in a high percentage of BPD patients. Until now, no empirical data exists on whether these patients concomitantly

suffer from sexual dysfunction.

Aim.

This study investigates sexual function and the impact of sexual traumatization on this issue in women with

BPD as compared to healthy women.

Main Outcome Measures.

Sexual function was measured using the Female Sexual Function Index. Additionally,

diagnoses were made with SCID II Interviews for Axis II and with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

for Axis I disorders. The Post-traumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale for trauma evaluation was used. Sexual orientation

was assessed by self-evaluation.

Methods.

Forty-five women with BPD as diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria and 30 healthy women completed

questionnaires on sexual function and sexual abuse history, as well as interviews on axis I and II disorders and

psychotropic medication.

Results.

The BPD group showed a significantly higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction. Subgroup analyses revealed

that BPD with concomitant sexual traumatization, and not BPD alone, best explains impaired sexual function. Sexual

inactivity was mainly related to current major depression or use of SSRI medication. In sexually active participants,

medication and symptoms of depression had no significant impact on sexual function.

Conclusions.

Not BPD alone, but concomitant sexual traumatization, predicts significantly impaired sexual func-

tion. This may have a therapeutic impact on BPD patients reporting sexual traumatization. Schulte-Herbrüggen

O, Ahlers CJ, Kronsbein JM, Rüter A, Bahri S, Vater A, and Roepke S. Impaired sexual function in patients

with borderline personality disorder is determined by history of sexual abuse. J Sex Med 2009;6:3356–3363.

Key Words.

Borderline Personality Disorder; Sexual Orientation; FSFI; Sexual Abuse; Sexual Dysfunction; Female

Sexual Function

Introduction

B

orderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a

complex mental disorder characterized by a

pervasive pattern of instability in emotion regula-

tion, interpersonal relationships, self-image, and

impulse control [1]. Prevalence rates of up to 5.8%

have been found in the general population [2].

BPD is the most common personality disorder in

clinical settings and is characterized by severe

functional impairment, substantial treatment utili-

zation, and a high mortality rate [3].

Impulsivity in BPD affects multiple areas of

life such as spending money, traffic behavior,

substance abuse, eating, and sexuality [4]. Even

though clinical experience suggests impulsive

3356

J Sex Med 2009;6:3356–3363

© 2009 International Society for Sexual Medicine

sexual behavior, identity disturbance, and unstable

relationships accompanied by hyper- as well as

hypo-sexual desire disorders (often leading to

sexual avoidance or promiscuity) are frequently

seen phenomena in patients with BPD, there is not

much empirical data available regarding sexual

behavior in this group of patients. A study on 119

male and 284 female adolescents from primary

care settings reported an increased number of

unsafe sexual partners for females with elevated

Personality Disorder (PD) symptom levels.

Besides others, the BPD symptoms of “impulsiv-

ity,” “abandonment fear,” and “unstable self-

image” were associated in this study with a high

number of sexual partners [5]. Data on adolescents

are not directly applicable to adults, thus there is

little empirical evidence pointing toward increased

promiscuity and risk for unsafe sex practices in

patients with BPD [6,7]. On the other hand, there

is a study by Zanarini and colleagues [8] reporting

that 42.2% of the female BPD patients to be

avoidant of consenting sex, and 36.5% had become

symptomatic (e.g., had become dissociated, re-

ported feeling suicidal, or hurt themselves) after

consenting to sex within the last 2 years. A study by

Sansone and colleagues [9] reported earlier sexual

exposure as well as rape, but no other aspects of

sexual impulsivity, such as a larger number of

sexual partners or more frequent treatment for

sexually transmitted diseases, in their sample of 76

women with BPD symptomatology. Nevertheless,

the study did not differentiate between sexually

active and sexually inactive participants.

Empirical data point out that childhood sexual

abuse (CSA), an identified contributory variable to

BPD, is associated with sexual impulsivity, mostly

promiscuity [10,11]. Although the empirical data

are not completely consistent, hypo- and hyper-

sexual desire can be observed in CSA survivors [12].

Apart from studies on sexual behavior in BPD

patients, there is even less evidence with regard to

the extent that sexual characteristics (e.g., sexual

function) are affected for these patients [13]. Hurl-

bert and colleagues found higher levels of sexual

assertiveness, higher sexual self-esteem, greater

sexual preoccupation, more sexual boredom, and

greater sexual dissatisfaction as compared to

women without BPD [14].

In the present study, we focused on sexual func-

tion in women with BPD in a clinical sample

compared with healthy women with respect to

contributing factors such as medication, psychia-

tric comorbidity (e.g., depression), post-traumatic

stress disorder (PTSD), and history of sexual abuse.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Forty-five patients diagnosed with BPD (accord-

ing to DSM-IV) and 30 healthy women agreed to

participate in the study. A larger number of BPD

patients was chosen to guarantee an equal number

of sexually active participants in each group. All

BPD patients were admitted to our specialized

inpatient treatment program for BPD, during

which they were consecutively recruited into the

study between October 2005 and March 2008.

Prior to admission to the inpatient program, all of

them were on a waiting list and none was admitted

for acute care. Patients were not reimbursed

for study participation. Healthy controls were

recruited via media advertisements and reim-

bursed for participation. The study was approved

by the ethics committee of the Charité-University

Medicine Berlin. All participants provided written

informed consent after having received a thorough

explanation of the study.

Axis II diagnoses were confirmed or excluded in

patients and controls with the German version of

the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

(SCID II); axis I diagnoses were assessed with the

German version of the Mini International Neu-

ropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.). Exclusion cri-

teria for the patients were anorexia nervosa,

oligophrenia, schizophrenia, pregnancy, and age

younger than 18 years. Current or chronic medical

conditions in patients and controls were excluded

by a clinical interview. Any use of medication

within the prior 2 months was an exclusion crite-

rion for controls. Interviews were performed or

supervised by a senior psychiatrist. Concurrent

comorbid psychiatric diagnoses in BPD patients

included the following: major depression (actual

N = 11, 24.4%; lifetime N = 23, 51.1%), dys-

thymia

(actual

N = 10,

22.2%),

obsessive–

compulsive disorder (actual N = 4, 8.9%), PTSD

(actual N = 18, 40%), panic disorder (actual N = 5,

11.1%), alcohol use disorder (last year, N = 11,

24.5%), substance use disorder (last year, N = 15,

33.3%), bulimia (actual N = 14, 31.1%); and

among comorbid personality disorder diagnoses,

paranoid (N = 4, 8.9%), schizotypal (N = 1, 2.2%),

antisocial (N = 2, 4.4%), narcissistic (N = 1,

2.2%), histrionic (N = 2, 4.4%), avoidant (N = 8,

17.8%), obsessive–compulsive (N = 6, 13.3%).

Fourteen (31.1%) BPD patients were on atypical

neuroleptics, 25 (55.6%) on SSRIs, and 18 (40%)

were without psychotropic medication. None of

the patients took any other medication.

Sexual Function in BPD

3357

J Sex Med 2009;6:3356–3363

Assessment Instruments

The PTSD Diagnostic Scale (PDS) is a 49-item

self-report measure of PTSD that was used to

assess all six DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for PTSD

[1]. In the study, we used the instrument for assess-

ment of trauma type. Depressive symptoms were

assessed with the 17-item Hamilton Depression

Scale (HAMD). Sexual orientation was assessed by

self-evaluation of the participants.

Sexual Function

For assessment of female sexual function, the

Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), a 19-item

self-report instrument, was applied, including six

key domains (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm,

satisfaction, and pain). The administration takes

about 15 minutes. Responders were asked to base

their responses on the previous 4 weeks. Subscores

are computed by item summation and by multi-

plying by a weighting factor. A total score is cal-

culated by summation of all subscores, indicating

an overall sexual function score. A total FSFI score

of 26.55 or lower has been defined as the cut-off

score for distinguishing between impaired and

intact sexual function [15]. Former studies have

described inter-item reliability values within the

acceptable range for sexually healthy women

(Cronbach’s a = 0.82–0.92) [16]. The FSFI has

been validated and culturally adapted in about 15

countries, including Germany [17].

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS

(version 14) software. Before using parametric

tests,

histograms

were

graphed

and

the

Kolmogorov–Smirnov

test

was

performed.

Between-groups comparisons were done with two-

tailed t-tests. The distribution of sexual orienta-

tion in the two study groups was assessed with

cross tabulations and analyzed with chi-square

tests. Further analyses were performed with linear

regression models, multiple analyses of covariance

(MANCOVA), and Pearson’s correlation coeffi-

cients. All significance levels were set to 0.05. All

means and standard deviations were presented

when appropriate.

Results

Self-Reported Sexual Orientation

Self-evaluation of sexual orientation revealed

24.4% bisexual and 6.7% homosexual BPD

patients, and 6.7% bisexual and 13.3% homo-

sexual healthy controls. All others reported

heterosexual

orientation.

Nevertheless,

the

distribution of sexual orientation did not differ

significantly between the two groups (Table 1).

Sexual Activity and Major Depression

Twenty-six (57.8%) of the BPD patients and 10

(33.3%) of the control women reported no sexual

activity during the 4 weeks prior to the interview.

These distribution differences were statistically

significant (c

2

(1)

=

4.31, P = 0.04). To investigate

whether lack of sexual activity within the last 4

weeks might be an effect of medication or depres-

sive symptomatology, comorbid axis I disorder, or

history of sexual abuse, which have repeatedly

Table 1

Sociodemographic data and psychometric measures in patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and

healthy controls

BPD patients

N

= 45, mean (SD)

Healthy controls

N

= 30, mean (SD)

Statistics

Age

28.2 (7.2)

27.7 (4.2)

T

= 0.30

HAMD total score

11.4 (4.8)

1.9 (1.7)

T

= 10.4**

Sexual orientation

Heterosexual

31, 68.9%

24, 80%

c

2

(2)

= 4.44

Homosexual

3, 6.7%

4, 13.3%

P

= 0.11

Bisexual

11, 24.4%

2, 6.7%

FSFI

N

= 19

†

N

= 20

†

Total score

24.1 (5.1)

30.8 (2.8)

T

= -5.1** df = 37

Desire

3.5 (1.8)

3.9 (1.0)

T

= -1.1 df = 37

Arousal

4.1 (1.3)

5.3 (0.5)

T

= -4.0** df = 23.7

Lubrification

5.0 (1.1)

5.7 (0.5)

T

= -2.5* df = 25.0

Orgasm

3.3 (1.2)

5.2 (0.9)

T

= -5.6** df = 37

Satisfaction

3.8 (1.7)

5.1 (0.9)

T

= -3.0** df = 26.7

Pain

4.5 (1.2)

5.7 (0.5)

T

= -4.1** df = 23.5

*P

< 0.05; **P < 0.01.

†

Sexually active within the last 4 weeks.

BPD

= Borderline personality disorder; df = degrees of freedom; FSFI = Female Sexual Function Index; HAMD = 17-item Hamilton depression scale;

SD

= standard deviation.

3358

Schulte-Herbrüggen et al.

J Sex Med 2009;6:3356–3363

been shown to reduce sexual desire and function

[12,18,19], a stepwise forward logistic regression

analysis predicting sexual inactivity was per-

formed, including HAMD score, treatment with

atypical neuroleptics, SSRI use, sexual traumatiza-

tion (item 5 or 6 of the PDS), dysthymia, and

PTSD as covariates. Accordingly, only inclusion of

SSRI medication (B = -1.5, P = 0.025) resulted

in a significant model (Nagelkerke’s R

2

=

0.17)

explaining sexual abstinence. Actual major depres-

sive episode (MDE) could not be included in the

regression model as only one patient (5.3% of the

sexually active patients) in the MDE group was

sexually active. Thus, the distribution of sexually

active vs. non-sexually active was significantly dif-

ferent in the group with comorbid MDE versus no

comorbid MDE (c

2

(1)

=

6.55, P = 0.01). Seven

patients with comorbid MDE were taking an SSRI

(representing 63.6% of patients with comorbid

MDE), and 18 patients without comorbid MDE

were taking an SSRI (representing 52.9% of

patients without comorbid MDE); this distribu-

tion was not significantly different (c

2

(1)

=

0.39,

P = 0.54), indicating that actual MDE and SSRI

medication were two independent variables influ-

encing sexual abstinence.

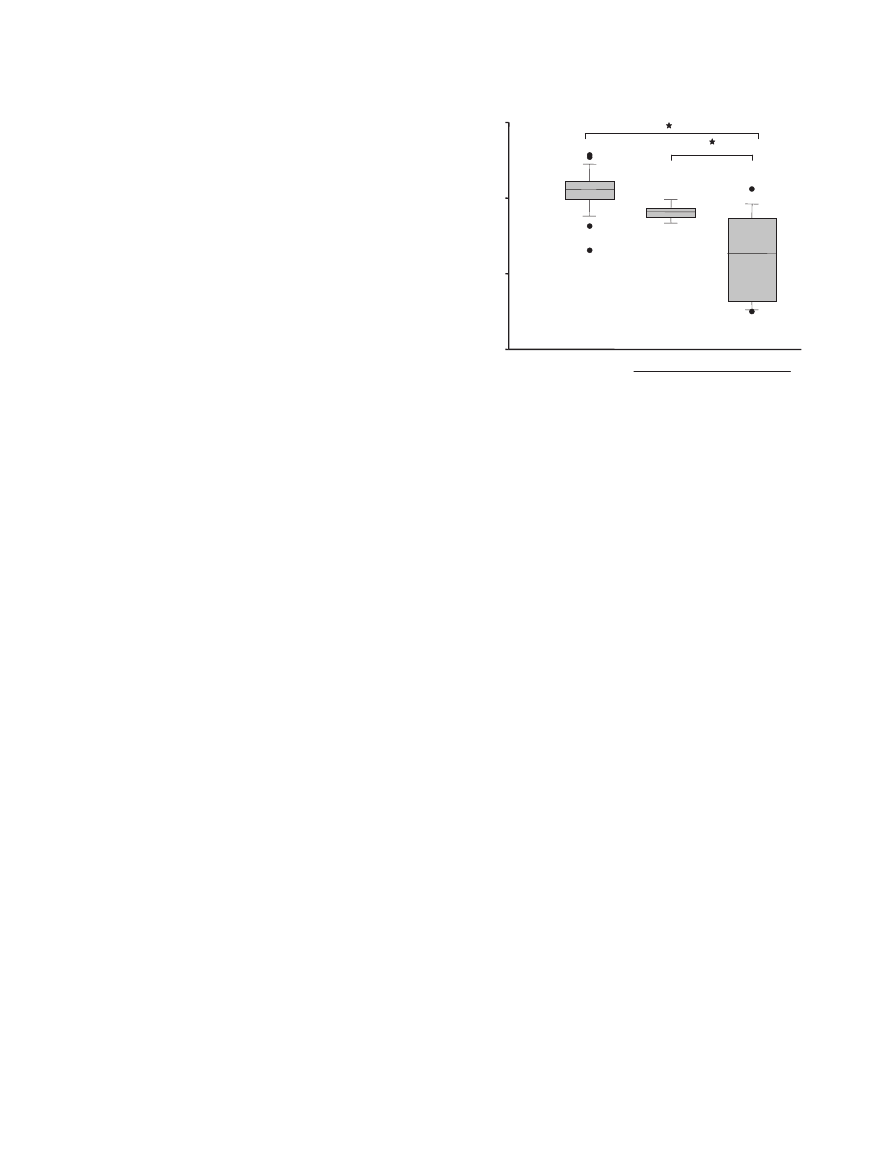

Sexual Function in Patients with BPD

Patients with BPD showed a significant reduction

of sexual function as reflected in the FSFI total

score and almost all subscores. Only the subscore

“desire” was unchanged compared to healthy

women (Table 1). Since 9 (47.4%) of the sexually

active BPD patients had FSFI total scores below

26.5 points (mean 24.1 [SD 5.1]), a remarkable

number of patients in the study group met the

criteria for “sexual dysfunction” as specified by

the validation study [15]. In the control group,

two women showed an FSFI score below 26.5

(Figure 1). Three sexually active BPD patients and

one sexually inactive BPD patient did not fill out

the PDS (assessment of trauma type) and were

excluded from the analysis of predictors of sexual

dysfunction. Seventeen (68.0%) out of 25 sexually

inactive BPD patients reported a history of sexual

traumatization. Eleven (68.8%) out of 16 sexually

active BPD patients reported a history of sexual

traumatization. All controls filled out the PDS, of

whom none reported a history of sexual traumati-

zation. Since sexual dysfunction has widely been

discussed in the context of sexual traumatization,

especially CSA, we performed subgroup analyses

using a stepwise regression model, including the

variables psychotropic medication (SSRI or atypi-

cal neuroleptics), sexual traumatization (item 5 or

6 of the PDS), and HAMD score. This statistical

approach revealed a significant model (corrected

R

2

=

0.20) with sexual traumatization (B = -5.7,

P = 0.047) as the only contributing factor. An

anova model for sexually active participants with

group (BPD with sexual traumatization, BPD

without sexual traumatization, and controls) as the

only independent variable, and FSFI sum score as

the dependent variable, revealed a significant

influence of group (P

< 0.001). Post hoc analysis

(Bonferroni-corrected) revealed a significant dif-

ference of mean FSFI score between controls

and BPD patients with sexual traumatization

(P

< 0.001) and BPD patients with and without

sexual traumatization (P = 0.03) (Figure 1). None

of the sexually active BPD patients who did not

report a history of sexual traumatization showed

an FSFI score below 26.5 (Figure 1).

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed sexual function

in women with BPD compared to healthy con-

trols. For the first time, we provide empirical evi-

dence for impaired sexual function in this group.

Hereby, current sexual abstinence was mainly

explained by a current episode of major depression

or concomitant medication with an SSRI. Further

Controls BPD without

BPD with

Hx of sexual abuse

FSFI sum

score

10

20

30

40

Figure 1 The figure shows the sum scores of the Female

Sexual Function Index for healthy controls (N

= 20), BPD

patients who did not reported sexual abuse (N

= 5), and

BPD patients who reported sexual abuse (N

= 11). The data

are presented as box plots displaying the median, quartiles,

and extremes. Asterisks indicate significant differences

(*P

< 0.05) that are corrected for multiple comparisons

(Bonferroni). Hx

= History.

Sexual Function in BPD

3359

J Sex Med 2009;6:3356–3363

investigation showed that in sexually active

women, BPD with concomitant sexual trauma-

tization, rather than BPD alone, is crucial for

sexual dysfunction in adulthood in these patients,

whereas co-diagnoses such as PTSD, major

depression, as well as use of medication neurolep-

tics or SSRIs) do not have a comparable impact.

Only the FSFI subscore “desire” did not differ

from healthy controls. This finding is in line with

a former study on sexuality in BPD patients reveal-

ing more positive attitudes about sex and greater

sexual preoccupation on the one hand, and sexual

dissatisfaction on the other hand [14]. The authors

suggest that a higher preoccupation with sex, com-

pared to non-borderline women is not surprising

since patients with BPD need “to bolster their

self-image, to approximate the kind of intimacy of

which they are incapable and to combat the feeling

of loneliness and boredom.” One possible expla-

nation for the fact that some studies reveal reduced

as well as increased sexual desire in BPD patients,

and the fact that in the present study, we find

unchanged sexual desire as compared to healthy

controls, may be due to the fact that BPD patients

with reduced sexual desire were not sexually active.

The FSFI is designed and validated to assess sexual

desire during sexual activity intervals, but not for

those subjects who feel sexual desire but do not

have sex. Future experimental studies are required

to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of these

findings with a focus on questions of general and

sexual identity.

This study clearly shows that sexual dysfunction

is not specific to BPD, but is often closely asso-

ciated with it since sexual traumatization is a

common but not obligatory phenomenon in these

patients. There is widely accepted evidence linking

CSA with long-term sexual dysfunction in adult-

hood in clinical samples [20–22]. Furthermore,

data from population-based studies reveal that

CSA, which is a common phenomenon, contrib-

utes to a significant impairment in the sexual func-

tioning of adults, especially in women [23]. In

contrast to that, a recent study on 699 college

students who anonymously completed question-

naires on sexuality and sexual abuse history

revealed differences between women who experi-

enced sexual abuse and non-abused controls for

sexual satisfaction, but not on the FSFI sum score

[21]. Interestingly, a meta-analytic study supports

the hypothesis that sexual dysfunction affects a

significant but quite small percentage of those who

have experienced CSA in a long-lasting and severe

manner [24].

Additional factors like better coping strategies,

personality traits [25] that may constitute a vulner-

ability to develop a personality disorder like BPD,

but also the level of ferocity and the relationship

with the abuser (e.g., a family member), may be

factors that contribute to suffering from sexual

dysfunction in adulthood.

Very little experimental data on the possible

mechanisms for how CSA may influence sexual

function in adulthood is available. An activation of

the sympathetic nervous system by physical exer-

cise did increase sexual arousal in healthy subjects,

but not in the CSA plus PTSD group [26]. More-

over, a subgroup of CSA survivors revealed in-

creased cortisol levels after exposure to a sexually

stimulating video, which may reflect an increased

automatic fear response to sexual stimuli [27]. In a

sample of 56 women with and without a history of

CSA, a study using an implicit association test

indicated a lack of excitatory cognitive and affec-

tive responses to sexual stimuli [28]. In this study,

however, sex was not more strongly associated

with an unpleasant valence compared to daily

activities. Sexual self-schemas, describing how

people make sense of the sexual self and how they

react to sexual stimuli, were investigated in CSA

survivors and controls. For cohabitating partners,

there was a significant relationship between CSA

and negative affect, which was mediated by the

“romantic/passionate” schema. This relationship

was independent from depression anxiety [29].

Thus, the first available studies on this issue point

to complex physiological but also psychological

(cognitive and emotional) changes that contribute

to impaired sexual function in CSA survivors.

Further studies are warranted to elucidate the neu-

rophysiological and sociopsychological mecha-

nisms of sexual dysfunction in this context.

In addition, BPD women show a trend for

describing themselves as more bisexually-oriented

as compared to healthy controls. This trend might

hypothetically reflect a part of general and sexual

identity disturbance probably due to an ambiva-

lence resulting from a heterosexual orientation

in combination with an abuse-derived coping

strategy of sexuality. In a prospective 10-year-

follow-up study investigating the prevalence of

homo- and bisexuality in 290 BPD patients, of

whom 233 were female, compared to 72 subjects

with other personality disorders, BPD patients

revealed significantly more homo- and bisexual

orientations [30]. In the present study, 13.3% of

the healthy women described themselves as homo-

sexual. Depending on the definition of homosexual

3360

Schulte-Herbrüggen et al.

J Sex Med 2009;6:3356–3363

orientation, the prevalence in large surveys of

national population-based samples in the United

States and France was approximately 11% regard-

ing “homosexual attraction but no homosexual

behavior,” and

⫾18% regarding “homosexual

attraction and behavior.” Examination of “homo-

sexual behavior separately” finds that only about

3% of the females report real homosexual contacts

[31]. In the present study, we did not differentiate

between sexual attraction, sexual self-definition,

and sexual behavior; and pre-orgasmic imagina-

tion, thus, the prevalence of sexual orientation

should be interpreted with caution, and further

research is needed to address this topic.

The concept of sexual orientation as a dimen-

sional paradigm of erotic experience (above all,

pre-orgasmic fantasies) and sexual behavior with

inexact transition between hetero-, homo-, and

bisexuality has been widely discussed [32]. The

large number of self-reports of bisexuality in BPD

may reflect identity disturbance, which is listed

in the DSM-IV [1] as a criterion for BPD, and

describes an uncertainty about sexual orientation

as a part of an indefinite sexual identity. Former

studies have repeatedly pointed to an association

between homosexuality and bisexuality, especially

in male BPD patients, compared to the prevalence

in the general population [33,34]. It has even been

suggested that homosexual orientation in a pre-

dominantly heterosexual environment increases

identity confusion, and therefore, promotes a

higher prevalence of BPD among homosexually

or bisexually oriented individuals [35]. However,

there has been controversial discussion about this

issue since research on the association between

BPD and homosexuality may have not sufficiently

taken into consideration the possible sexual orien-

tation bias in diagnoses of BPD that were based on

DSM-III and -IIIR criteria [36,37].

The DSM-IV states that patients with BPD may

experience sudden changes in sexual identity, but

takes into account that conflicts about sexual ori-

entation, especially in young adults, are a frequent

but often transient problem within healthy per-

sonality development, and therefore should not be

mistakenly diagnosed as a criterion for BPD.

Some important limitations of the present study

have to be taken into consideration. Sexual dys-

function and the type of trauma were only assessed

by questionnaires. Additional clinical exploration

of sexual problems by a senior psychiatrist as con-

ducted for the assessment of Axis I and II disorders

would have supported the clinical significance of

impaired sexual function as assessed by the FSFI.

Furthermore, the study does not include a struc-

tured clinical exploration of the reasons for the

sexual abstinence that was reported by an impor-

tant number of women in both groups. In addi-

tion, verification of reported sexual traumatization

(e.g., by asking family members or court records)

would have increased the validity of the assessment

of trauma type. Also, subthreshold PTSD and

severity of PTSD symptoms were not considered

in the present study. The study includes a small

number of women, but provides highly significant

findings. Further studies in larger samples are

needed to replicate the results. Furthermore, in

the current study we did not assess sexual dysfunc-

tion according to DSM-IV criteria. Also, medical

conditions that could influence sexual function,

libido, or sexual activity were only considered to be

absent according to clinical interview, and were

not assessed using structured methods (e.g., lab

tests).

In conclusion, sexual traumatization in women

with BPD closely determines sexual dysfunction.

In addition, current depression or SSRI medica-

tion are the main causes for sexual abstinence in

these patients. These factors are common phe-

nomena in BPD. Therefore, this may have great

impact on diagnostic procedures as well as thera-

peutic intervention in BPD patients, especially

when the issue of partnership and sexuality is con-

cerned. In our sample, an remarkable number of

the women with BPD reported themselves to be

bisexual, which might hypothetically reflect the

BPD typical identity disturbance.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Jane Thompson for the linguistic

revision.

Corresponding Author: Stefan Roepke, MD, Depart-

ment of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Charité-

University

Medicine

Berlin,

Campus

Benjamin

Franklin, Eschenallee 3, D-14050 Berlin, Germany,

EU. Tel: +49-30-8445-8796; Fax: +49-30-8445-8365;

E-mail: stefan.roepke@charite.de

Conflict of Interest: None.

Statement of Authorship

Category 1

(a) Conception and Design

Stefan Roepke; Julia-Maleen Kronsbein; Olaf

Schulte-Herbrüggen; Christoph J. Ahlers

Sexual Function in BPD

3361

J Sex Med 2009;6:3356–3363

(b) Acquisition of Data

Julia-Maleen Kronsbein; Aline Vater; Anke Rüter;

Scharif Bahri

(c) Analysis an Interpretation of Data

Stefan Roepke; Olaf Schulte-Herbrüggen; Anke

Rüter; Scharif Bahri

Category 2

(a) Drafting the Manuscript

Stefan Roepke; Olaf Schulte-Herbrüggen; Aline

Vater

(b) Revising It for Intellectual Content

Scharif Bahri; Christoph J. Ahlers; Julia-Maleen

Kronsbein

Category 3

(a) Final Approval of the Completed Manuscript

Julia-Maleen Kronsbein; Anke Rüter; Olaf Schulte-

Herbrüggen; Christoph J. Ahlers; Aline Vater;

Stefan Roepke

References

1 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and

statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edition.

American Psychiatric Association: DSM-IV; 1994.

2 Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B,

Stinson FS, Saha TD, Smith SM, Dawson DA,

Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ. Prevalence,

correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV

borderline personality disorder: Results from the

Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol

and Related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69:

533–45.

3 New AS, Triebwasser J, Charney DS. The case for

shifting borderline personality disorder to Axis I.

Biol Psychiatry 2008;64:653–9.

4 First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB.

User’s guide for the structured clinical interview

for DSM-IV personality disorders (SCID II). Wash-

ington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

5 Lavan H, Johnson JG. The association between axis

I and II psychiatric symptoms and high-risk sexual

behavior during adolescence. J Personal Disord

2002;16:73–94.

6 Hull JW, Clarkin JF, Yeomans F. Borderline per-

sonality disorder and impulsive sexual behavior.

Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993;44:1000–2.

7 Miller FT, Abrams T, Dulit R, Fyer M. Substance

abuse in borderline personality disorder. Am J Drug

Alcohol Abuse 1993;19:491–7.

8 Zanarini MC, Parachini EA, Frankenburg FR,

Holman JB, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. Sexual

relationship difficulties among borderline patients

and axis II comparison subjects. J Nerv Ment Dis

2003;191:479–82.

9 Sansone RA, Barnes J, Muennich E, Wiederman

MW. Borderline personality symptomatology and

sexual impulsivity. Int J Psychiatry Med 2008;38:53–

60.

10 Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, daCosta GA,

Akman D. A review of the short-term effects of

child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl 1991;15:537–

56.

11 Paolucci EO, Genuis ML, Violato C. A meta-

analysis of the published research on the effects of

child sexual abuse. J Psychol 2001;135:17–36.

12 Rellini A. Review of the empirical evidence for a

theoretical model to understand the sexual problems

of women with a history of CSA. J Sex Med 2008;

5:31–46.

13 Zemishlany Z, Weizman A. The impact of mental

illness on sexual dysfunction. Adv Psychosom Med

2008;29:89–106.

14 Hurlbert DF, Apt C, White LC. An empirical

examination into the sexuality of women with

borderline personality disorder. J Sex Marital Ther

1992;18:231–42.

15 Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual

function index (FSFI): Cross-validation and devel-

opment of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther

2005;31:1–20.

16 Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston

C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, D’Agostino R Jr. The

Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidi-

mensional self-report instrument for the assessment

of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 2000;

26:191–208.

17 Berner MM, Kriston L, Zahradnik HP, Härter M,

Rohde A. Validity and reliability of the German

female sexual function index (FSFI-d). Geburtshilfe

Frauenheilkd 2004:293–303.

18 Clayton AH. Female sexual dysfunction related to

depression and antidepressant medications. Curr

Womens Health Rep 2002;2:182–7.

19 Martin-Du PR, Baumann P. [Sexual dysfunctions

induced by antidepressants and antipsychotics]. Rev

Med Suisse 2008;4:758–62.

20 DiLillo D. Interpersonal functioning among women

reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse:

Empirical findings and methodological issues. Clin

Psychol Rev 2001;21:553–76.

21 Rellini A, Meston C. Sexual function and satisfac-

tion in adults based on the definition of child sexual

abuse. J Sex Med 2007;4:1312–21.

22 Rumstein-McKean O, Hunsley J. Interpersonal and

family functioning of female survivors of childhood

sexual abuse. Clin Psychol Rev 2001;21:471–90.

23 Najman JM, Dunne MP, Purdie DM, Boyle FM,

Coxeter PD. Sexual abuse in childhood and sexual

dysfunction in adulthood: An Australian population-

based study. Arch Sex Behav 2005;34:517–26.

24 Rind B, Tromovitch P, Bauserman R. A meta-

analytic examination of assumed properties of child

sexual abuse using college samples. Psychol Bull

1998;124:22–53.

25 Harris JM, Cherkas LF, Kato BS, Heiman JR,

Spector TD. Normal variations in personality are

associated with coital orgasmic infrequency in

3362

Schulte-Herbrüggen et al.

J Sex Med 2009;6:3356–3363

heterosexual women: A population-based study.

J Sex Med 2008;5:1177–83.

26 Rellini AH, Meston CM. Psychophysiological

sexual arousal in women with a history of child

sexual abuse. J Sex Marital Ther 2006;32:5–

22.

27 Rellini A, Hamilton LD, Delville Y, Meston C.

Association between dissociation and cortisol

response during states of heightened physiological

sexual arousal in women with a history of child

sexual abuse. International Society for the Study of

Women’s Sexual Health 2007.

28 Rellini A, Ing D, Meston C. Implicit and explicit

cognitive processes and sexual arousal in survivors of

child sexual abuse. Meeting of the International

Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health

2006.

29 Meston CM, Rellini AH, Heiman JR. Women’s

history of sexual abuse, their sexuality, and sexual

self-schemas. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:229–

36.

30 Reich DB, Zanarini MC. Sexual orientation and

relationship choice in borderline personality disor-

der over ten years of prospective follow-up. J Per-

sonal Disord 2008;22:564–72.

31 Sell RL, Wells JA, Wypij D. The prevalence of

homosexual behavior and attraction in the United

States, the United Kingdom and France: Results of

national population-based samples. Arch Sex Behav

1995;24:235–48.

32 Rubio-Aurioles E, Wylie K. Sexual orientation

matters in sexual medicine. J Sex Med 2008;5:1521–

33.

33 Dulit RA, Fyer MR, Miller FT, Sacks MH, Frances

AJ. Gender differences in sexual preference and sub-

stance abuse in inpatients with borderline personal-

ity disorder. J Personal Disord 1993;7:182–5.

34 Zubenko GS, George AW, Soloff PH, Schulz P.

Sexual practices among patients with borderline

personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1987;144:

748–52.

35 Silverstein C. The borderline personality disorder

and gay people. J Homosex 1988;15:185–212.

36 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and

statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd edition.

Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1980.

37 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and

statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd edition

rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press;

1987.

Sexual Function in BPD

3363

J Sex Med 2009;6:3356–3363

Copyright of Journal of Sexual Medicine is the property of Blackwell Publishing Limited and its content may

not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

A Ser49Cys Variant in the Ataxia Telangiectasia, Mutated, Gene that Is More Common in Patients with

Personality Constellations in Patients With a History of Childhood Sexual Abuse

Effects of Clopidogrel?ded to Aspirin in Patients with Recent Lacunar Stroke

Difficult airway management in a patient with traumatic asphyxia

Dialectic Beahvioral Therapy Has an Impact on Self Concept Clarity and Facets of Self Esteem in Wome

Konstatinos A Land versus water exercise in patients with coronary

Muscle Mass Gain Observed in Patients with Short Bowel Syndrome

Difficult airway management in a patient with traumatic asphyxia

Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy of the Medial Prefrontal Cortex in Patients With Deficit Schi

Serum cytokine levels in patients with chronic low back pain due to herniated disc

The Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Markers of Blood Lipids, and Blood Pressure in Patients

Effect of high dose intravenous ascorbic acid on the level of inflammation in patients with rheumato

The relationship of Lumbar Flexion to disability in patients with low back pain

Chromatopelma cyaneopubescens First detailed breeding in captivity with notes on the species Journal

The World Is Flat Brief History of the Twenty First Century

Loyalty in National Socialism, A Contribution to the Moral History of the National Socialist Period

High Choline Concentrations in the Caudate Nucleus in Antipsychotic Naive Patients With Schizophreni

A nonsense mutation (E1978X) in the ATM gene is associated with breast cancer

Pathological dissociation and neuropsychological functioning in BPD

więcej podobnych podstron