Defining organization

There are many different approaches to defining organisations. Due to numerous perspectives

there is a lack of consensus about what precisely the term organisation means. R.W. Griffin, for

example, defines organisation as a “group of people working together in a structured and co-ordinated

way to achieve a set of goals” [Griffin 2009a, p. 4]. The presented definition is very short and

synthetic, but at least four important issues are emphasised in this sentence:

•

organisations are composed of people,

•

organisational activities are focused on achieving an established set of goals,

•

people work together to achieve goals, which means that they co-operate,

•

work within the organisation is co-ordinated in some way.

According to S.P. Robbins, organisation is a “continuously co-ordinated social entity, with

relatively identifiable boundaries that functions on the relatively continuous basis to achieve a

common goal or set of goals” [Robbins 1990, p. 4]. What is important, the continuous and stable

character of an organisation is stressed in this definition.

J.C. Wiliams, A.J. DuBrin and H.L. Sisk define an organisation as a “rationally structured

system of interrelated activities, processes, and technologies within which human efforts are co-

ordinated to achieve specific objectives” [Wiliams, DuBrin and Sisk 1985, p. 18]. Due to this

definition, an organisation is a rational object in which all components: individuals’ activities,

behaviour, processes, and technologies are integrated and related in a rational way.

Most authors agree that there are some basic elements that each organisation consists of:

•

People (personnel, staff, employees, members): people with their knowledge, skills, and attitudes

are basic component of each organisation. Organisations are founded by people, managed by

people, and they hire people. Thus, many researchers and managers treat people as the most

important resource of an organisation.

•

Goals (purposes, objectives, targets): goals can be defined as future states that organisation want

to achieve in its activities. In practice, organisations aim towards various sets of goals, e.g. a

turnover, profits, stocks value, high quality of products or services, organisational development,

organisational flexibility, satisfaction and morale of employees, etc. Organisational goals are

often in conflict, e.g. quantity versus quality, short-term profits versus long-term ones, etc. One of

the most difficult tasks for managers is to build a hierarchy and coherence of particular goals.

•

Structure: in almost all definitions of an organisation, we could find terms like “coordinated”,

“structuralised”, “hierarchy”, etc. All of them mean that individual activities are ordered in a

more or less formal way. The structure of an organisation allows to integrate and coordinate

individuals’ activities.

•

Technology: it can be understood as all machinery and tools that are used in designing products,

a production process, delivering goods, as well as communication and coordination of activities.

The technology used by organisation is strictly related with the profile of its activity and the

industry in which the business operates.

The first two components are named “soft” organisational elements. On the other hand, structure and

technology are treated as “hard” elements.

R.H. Hall presents more enlarged and detailed definition of an organisation. According to him,

“an organisation is a collective with relatively identifiable boundaries, a normative order (rules), ranks

of authority (hierarchy), communication systems and membership coordination systems (procedures);

this collective exists on the relatively continuous basis, in environment, and is engaged in activities

that are usually related to a set of goals; the activities have outcomes for organisational members, for

the organisation itself, and for society” [Hall 1999, p. 30]. At least two things are worth underlining in

this definition. First, an organisation exists in its environment (representatives of classical and

behavioural schools of management focused on the interior of an organisation and did not draw too

much attention to its environment). Secondly, the effects of an organisational activity concern not only

its founders and owners, but also other groups of interests: managers, workers, customers, co-workers,

local society, etc. This is the base of stakeholders and corporate social responsibility theories.

Why do we need organisations?

Imagine, how would the world looks like if there were no organisations? The one possible answer is

that it would be very different. Basic questions appear in this context: do we as individuals and

societies need organisations to survive and develop? What are the main reasons for founding

organisations and belonging to them? Explaining why we need organisations, we can mention at least

four basic groups of reasons.

The first is related to the synergy effect, which

appears when the effect generated by the whole is higher

that the simple sum of effects generated by the parts.

Aristotle as the first said that the whole is not just the sum of

parts, which means that it is something more. If all

organisational components are interrelated to and co-operate

with one another, the added value is created. R.H. Hall

[1999] emphasises that organisations are needed to have

complex things done. People working in organisations are

able to do things and accomplish goals that individuals

cannot.

The second reason for founding organisations and belonging to them is human needs.

According to Maslow’s motivation theory, we all feel needs of a different kind, and there is a

hierarchy of them in Maslow’s theory (to find more information about the theory, see Section 2.3.4.).

One of them is social needs. We all want to belong to the group, have good relationships with other

people, we need to be liked and loved by others. This is one of the reasons why we work in groups and

found organisations.

The next reason is that organisations protect us against chaos. As we could see in the

aforementioned definitions, organisations have their hierarchy, formal rules, and standards. Thanks to

that, they are ordered and stable.

J.A. Stoner and Ch. Wankel argue that organisations play a significant role in creating,

developing, and protecting knowledge, which is important for the whole civilisation. Without

organisations like universities, schools, research institutes, museums, and business corporations, we

would not be able to collect, develop, and share knowledge.

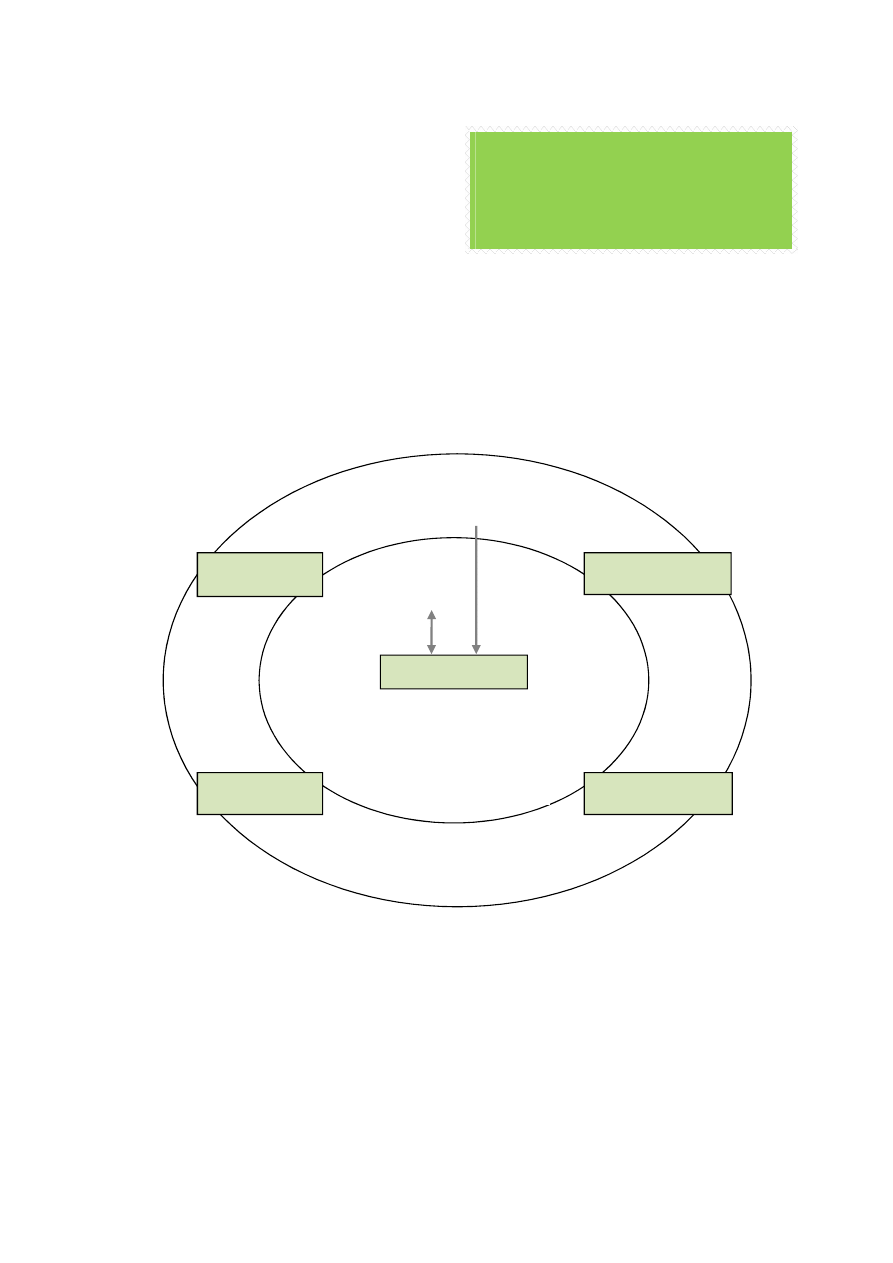

The model of organization

The study of the nature of organisation seemed to be simpler if we could base it on the model of

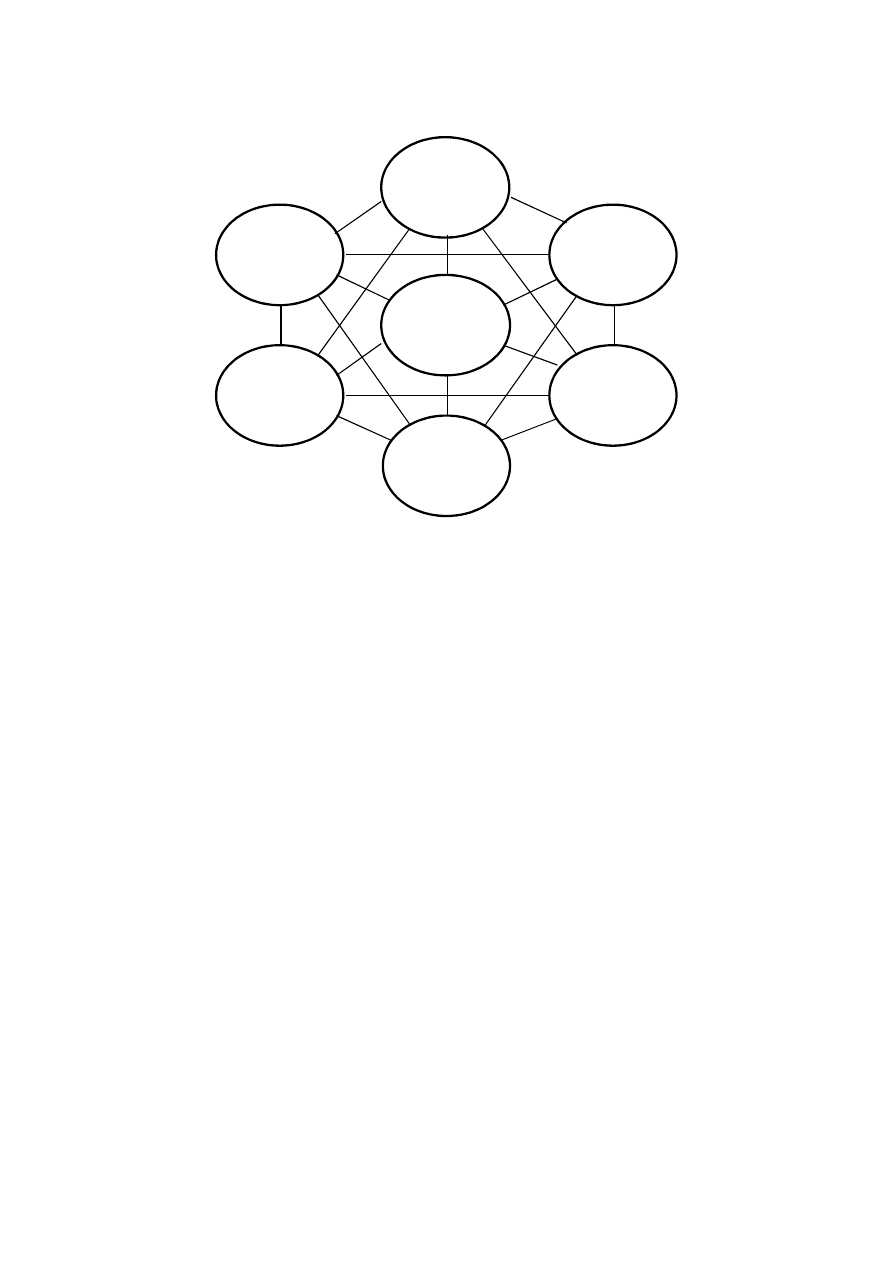

organisation. T. Peters and R. Waterman [1982] developed one of the most popular models in the

early 1980s, which is known as McKinsey 7S Framework. The model involves seven interdependent

components (see Figure 1.2.).

Organisations exist because they:

•

protect us against chaos,

•

facilitate the synergy effect,

•

allow for fulfilling humans needs,

•

support

the

development

and

diffusion of knowledge.

Figure 1.2. McKinsey 7S Model

Source: [Peters and Waterman 1982, p. 10].

The name of the model comes from the number and names of its main components. There are seven

main elements in the model and the name of each starts with the letter “S”. Those elements will be

described very generally in this section, and more detailed definitions will be present in subsequent

chapters of this book. According to T. Peters and R. Waterman [1982], the main organisational

elements are:

•

Strategy: a long-term plan of organisation’s activities devised to build and maintain a

competitive advantage.

•

Structure: the manner in which organisation components – its departments, divisions, or any

other subunits – are designed and interrelated.

•

Systems: the daily activities and procedures that staff members engage in to get the job done.

•

Style: a pattern of behaviour in leadership process. It contains a way of managerial behaviour,

and relationships between managers and subordinates.

•

Staff: all employees (managers, workers) in organisation with their competences, and

attitudes.

•

Skills: technical knowledge and skills which are hold within organisation, e.g., know-how.

•

Shared values: commonly held beliefs, values, mind-sets, and assumptions that shape how an

organisation behaves (organisational culture).

According to the research study performed in seventy-two best-run American companies, the last

component was the crucial factor in building a competitive advantage and high performance of

business organisations.

To be effective, organisation must have a high degree of fit or internal alignment among all the

seven components. Each one must be consistent with and reinforces the others. The model seems to be

helpful in understanding the nature of organisation.

STRUCTURE

SYSTEMS

STAFF

SHARED

VALUES

STYLE

STRATEGY

SKILLS

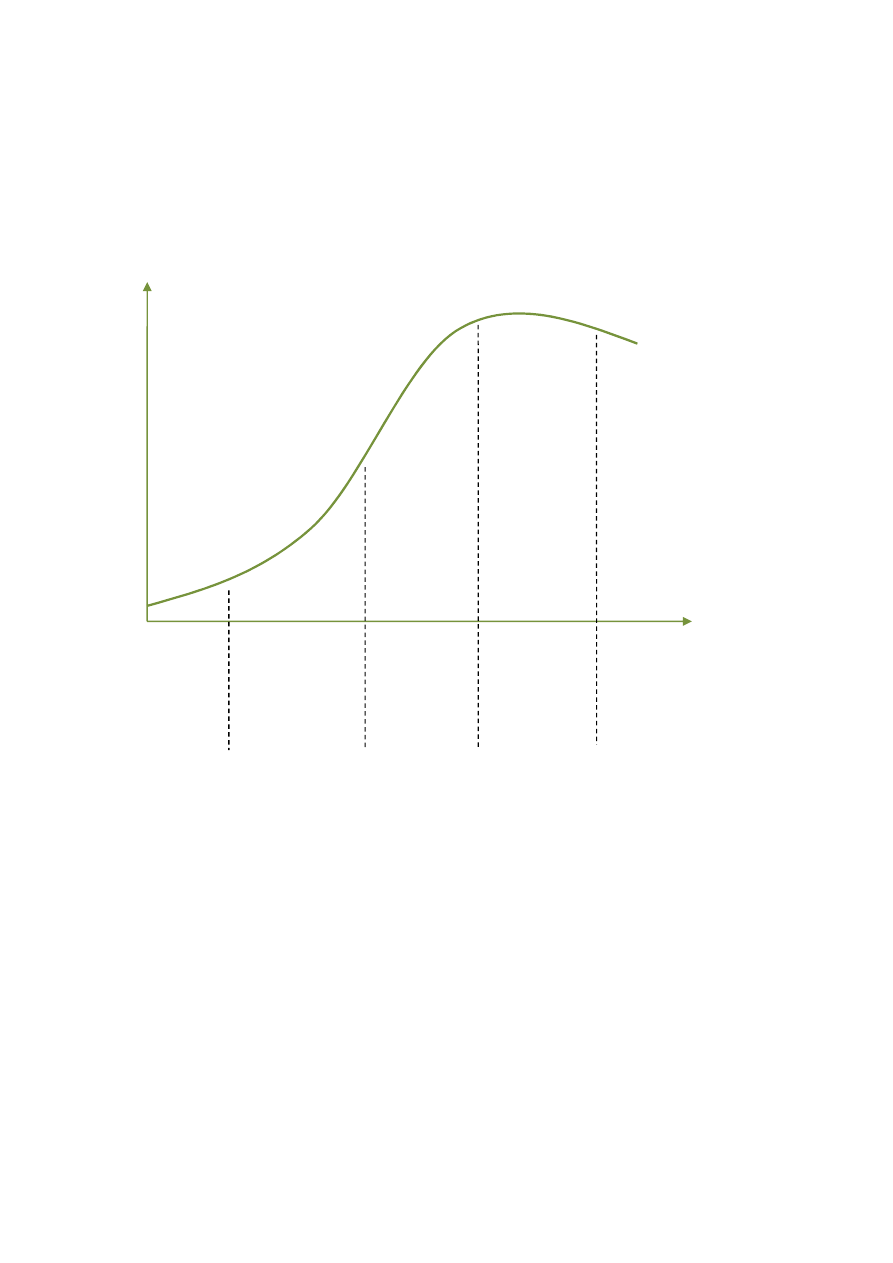

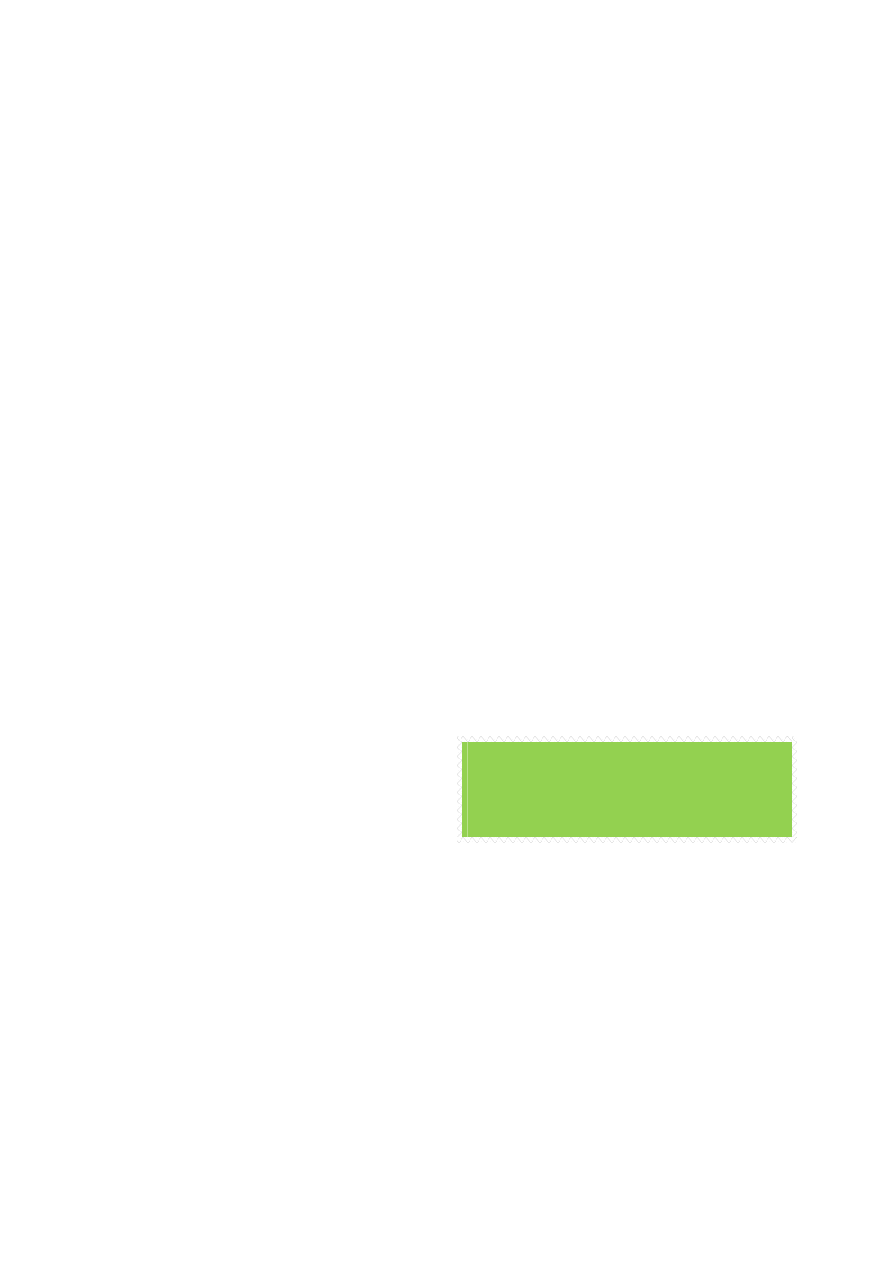

Organisational life cycle

Organisations are born (are founded) to develop and eventually die, like every human being, or

animals. This metaphor let us talk about an organisational life cycle, and make use of it to predict what

may happen with organisations during its existence. The life cycle refers to a pattern of predictable

developmental changes that typically occur in most organisations. There are various life-cycle models

in theory, and we will describe one of them in our further considerations.

Figure 1.3. Organisational life cycle

Source: [Robbins 1990, p. 22].

The model comprises five stages. The first one is defined as the entrepreneurial stage. At this

stage organisation is in its infancy, the whole management is in the hands of its owner (founder).

Management is based on intuition, personal engagement, direct interactions, and informal relationships

between managers and workers. There is no formal structure, written rules and procedures, and

creativity is very high.

As the organisation grows, it goes to the collectivity stage. A mission and a strategy have

been clarified, and individuals identify with group and build informal relationships. Structure and

systems still remain rather informal, and most decisions remain in the hands of a founder.

The next phase is called the formalisation-and-control stage. The formal structure appears,

and intuitive activities are replaced by rules and procedures. An organisation has become more stable

and predictable. To make an organisation more effective, formal systems are introduced, e.g. a

motivation system. Efficiency of workers and the whole organisation is emphasised. Decisions are

made by senior management, and creativity is much lower at this stage.

3. Formalisation-

and-control stage

– Formalisation of

rules

– Stable structure

– Emphasis on

efficiency

1. Entrepreneurial

stage

– Ambiguous goals

– High creativity

2. Collectivity stage

– Informal

communication and

structure

– High commitment

4. Elaboration-of-

structure stage

– More complex

structure

–Decentralisation

– Diversified markets

5. Decline stage

– High employee

turnover

– Increased conflict

– Centralization

Formation

Growth

Maturity

Decline

A growing organisation diversifies its strategy. Managers seek new products or markets to

obtain benefits and a higher level of security. According to Chandler’s theory [1962], a structure

follows a strategy, so the structure is changing as well: it is getting more flat, decision-making process

is being decentralised, and strategic business units (SBU) are set apart. This phase, called “the

elaboration-of-structure stage” provides an organisation with new opportunities to grow.

Due to the impact of external or internal factors, e.g. shrinking market or old technology, an

organisation enters into the decline stage. Efficiency and financial situation is getting worse and the

motivation of employees decreases, which leads to conflicts within the organisation, the increase of

the employee’s turnover, etc. It can mean the end of the organisation or its renewal.

Organizational environment

Most management thinkers who represented early movements – scientific management and

administrative management – focused mainly on the interior of an organisation. They tried to make an

organisation more efficient without looking at external conditions. Their works includes important and

practical theories, which were very useful and easy to apply in stable and predictable conditions (the

beginning of the twentieth century). Nevertheless, all those researchers seemed to underestimate the

importance of external environment of an organisation. A good example of internal orientation is Ford,

who produced only one model of Ford T and only in black colour. Customers’ taste and requirements

were not taken into consideration in those times.

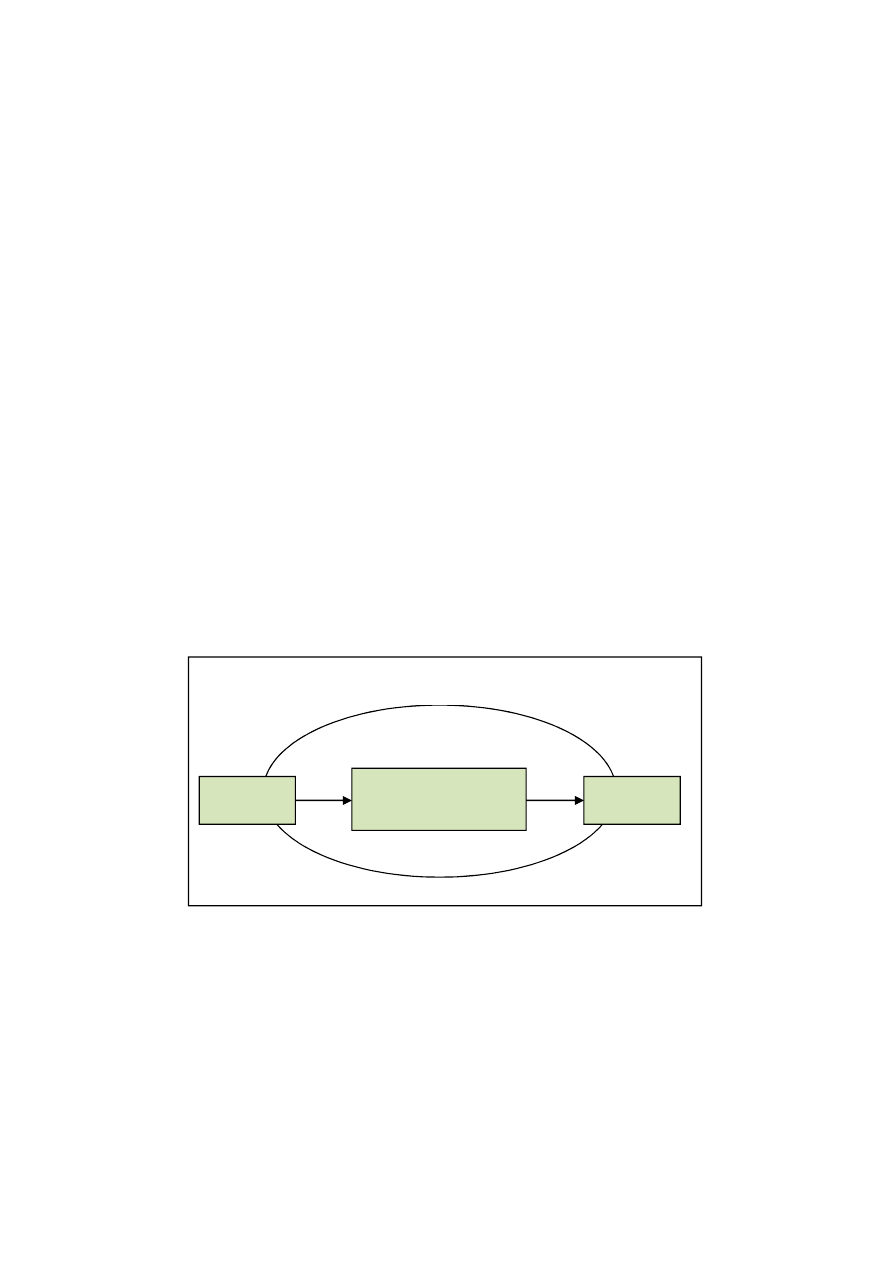

Further schools of management – the systems approach and the contingency approach – show

that an organisation exists in its external environment. According to the system approach, organisation

should be perceived as an open system. It means that there is continuous and dynamic exchange of

resources, energy, and information between an organisation and its environment. A simplified graphic

representation of the organisation as an open system is shown in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4. Organisation as an Open System

Source: [Donnelly, Gibson and Ivancevich 1992, p. 29].

Raw materials, labour, money, and knowledge are inputs in business organisations. A transformation

process means the change of raw materials into final products using proper methods and tools.

Additionally, final products or services are outputs of business organisations. All organisations seem

to be open systems and it is hard to imagine an organisation that does not interact with its external

environment nowadays.

INPUTS

OUTPUTS

TRANSFORMATION

PROCESS

SYSTEM

(ORGANISATION)

ENVIRONMENT

It

is

rather

easy

to

define

what

organisational environment is. E. Turban and J.R.

Meredith define the environment as “several

elements that lie outside the system in the sense that

they are not inputs, outputs, or processes. However,

they have an impact on the system’s performance

and consequently on the attainment of its goals”

[Turban and Meredith 1991, p. 28]. According to R.L. Daft, we can define external environment as

everything that is outside organisation boundaries but may affect the organisation [Daft 2011, p. 47].

Types of organisational environment

There are different approaches to the way of classifying and describing different types of

organisational environment. We can set apart the general environment, sometimes known as the

macro-environment, and the task environment, called also micro- or close environment.

Figure 1.5. Micro- and macro-environment of organisations

Source: Authors’ own work.

The main difference between task and general environment of organisation concerns the direction of

relationship. Task environment influences the organisation and the organisation affects task

environment in day-to-day interactions. The relationship is bilateral in this case, e.g. organisations

negotiate with suppliers, affect customers, and compete with market rivals.

General environment affects the organisation but the organisation does not affect general

environment (or the influence is limited very much in some cases, e.g. a large global organisation may

The external organisational environment

includes all elements and factors existing

outside the organisation which have the

potential

for

affecting

organisational

performance.

ORGANISATION

SUPPLIERS

COMPETITORS

CUSTOMERS

BANKS

OTHER INSTITUTIONS

FINANCIAL

INSTITUTIONS

GOVERMENT

AGENCIES

TASK

ENVIRONMENT

GENERAL

ENVIRONMENT

ECONOMIC

SITUATION

SOCIOCULTURAL

LEGAL AND

POLITICAL

TECHNOLOGICAL

affect technological or political domains). Regular enterprises generally do not have influence on

national economy, a law system, or society.

As a part of the general environment, we can also identify a special kind of environment that is

called “international environment”. This domain is crucial for organisations that operate on markets

indifferent countries.

The task environment

All components that stay with continuous and mutual interactions with the organisation

constitute the task environment, especially:

•

Suppliers: who provide raw materials, equipment, energy and media.

•

Customers: who buy final products or services (the outputs of organisation). According to

marketing theory, this is the most important group of interests in environment and

management should take special care of them.

•

Competitors: who operate on the same market and offer the same or similar goods. The

relationship between the organisation and its competitors may be friendly, indifferent or

hostile.

•

Government agencies: who represent national and local interests, take care of workers and

customers, promote ecology, etc..

•

Banks and financial institutions: who ensure the external source of capital offering

organisations loans, and other financial instruments,

•

Other institutions: which may influence organisation’s existence and development, e.g.

labour unions.

The task environment is also known as “the competitive environment” with the role of competitors is

emphasised in this case. According to M.E. Porter, five competitive forces determine the level of

competition in a given industry (for more information about Porter’s five competitive forces see

Section 3.2).

In the early 1960s, the global debate started to be dedicated to the role of business

organisations in solving social problems, like unemployment, pollution, clients’ safety, equality

between people with different sexes, races, age, etc. Should the companies be obliged to protect

natural environment, workers, customers and local society or only care for stockholders’ interests or

focus only on their goals and incomes? Some authors think that they should, and since the theory of

corporate social responsibility (CSR) appeared, it is getting more and more followers both among

scientists and managers.

The general environment

The general environment consists of various segments. According to PEST analysis, the major

domains of general environment are:

•

Political and legal domain: includes a political system of the country, and allows for

regulations that individuals and organisations must follow: the law system of the country, the

monetary and taxation policies, the health and safety regulations, the European Union

directives, etc.

•

Economic domain: affects all organisations which are part of a national and global economy.

Major economic factors are GDP, inflation, an unemployment rate, the salaries level, interest

rates, and currencies. All these macro-economic factors determine external conditions for

functioning and development of business, as well as non-profit organisations.

•

Socio-cultural domain: is related to society, national culture, and religion. One of the most

important factors in this domain is demography (the size and the age of population). Other

important factors are the level of education, customs, religion, beliefs, values, and lifestyle.

The aforementioned factors seem to be crucial until people are the immanent component of all

institutions, and people as customers buy products and services offered by organisations.

•

Technological domain: includes all mechanical and electronic devices which are used to

design, make and deliver products and services to customers. Nowadays the most widespread

and powerful are communication and collaboration technologies.

Every organisation is dependent on its external environment to some extent. Some companies are

more vulnerable to the aforementioned factors than others, depending on the resources that they

possess, and a strategy that they realise. For instance, organisations with strong financial resources are

much more resistant to economic fluctuations than those with no financial reserves [Hall 1999, p.

218]. Moreover, organisations that diversify their products or services portfolio will probably be less

vulnerable than those who offer only one single product. To read more about various strategies,

resources and environmental adjustment, see Chapter 3.

We will try to explain what management process is, starting with an overview of a few selected

definitions. M.P. Follett for example defined management as “the art of getting things done through

people” [Stoner, Freeman, Gilbert 1997, p. 53]. This definition seems to be very general, but the

explanation of three key words: “things”, “done” and “people” contributes to a clearer understanding.

“Things” mean different tasks that organisations perform to achieve established set of goals. “Done”

means accomplishing goals effectively and efficiently, and “people” means that the tasks are

completed by people.

H. Weihrich and H. Koontz define management as “the process of designing and maintaining

an environment in which individuals, working together in groups, efficiently accomplish selected

aims” [Weihrich and Koontz 1993, p. 4]. J.A. Stoner and Ch. Wankel treat management as “the

process of planning, organizing, leading, and controlling the efforts of organisation members and of

using all other organisational resources to achieve stated organisational goals” [Stoner and Wankel

1986, p. 32]. The last definition stresses that the management is a process comprised of four logically

and chronologically interrelated activities, called also “processes or functions of management”.

All the presented definitions seem to be

complementary to one another, as they describe

management,

stressing

its

most

important

characteristics and components from different

perspectives.

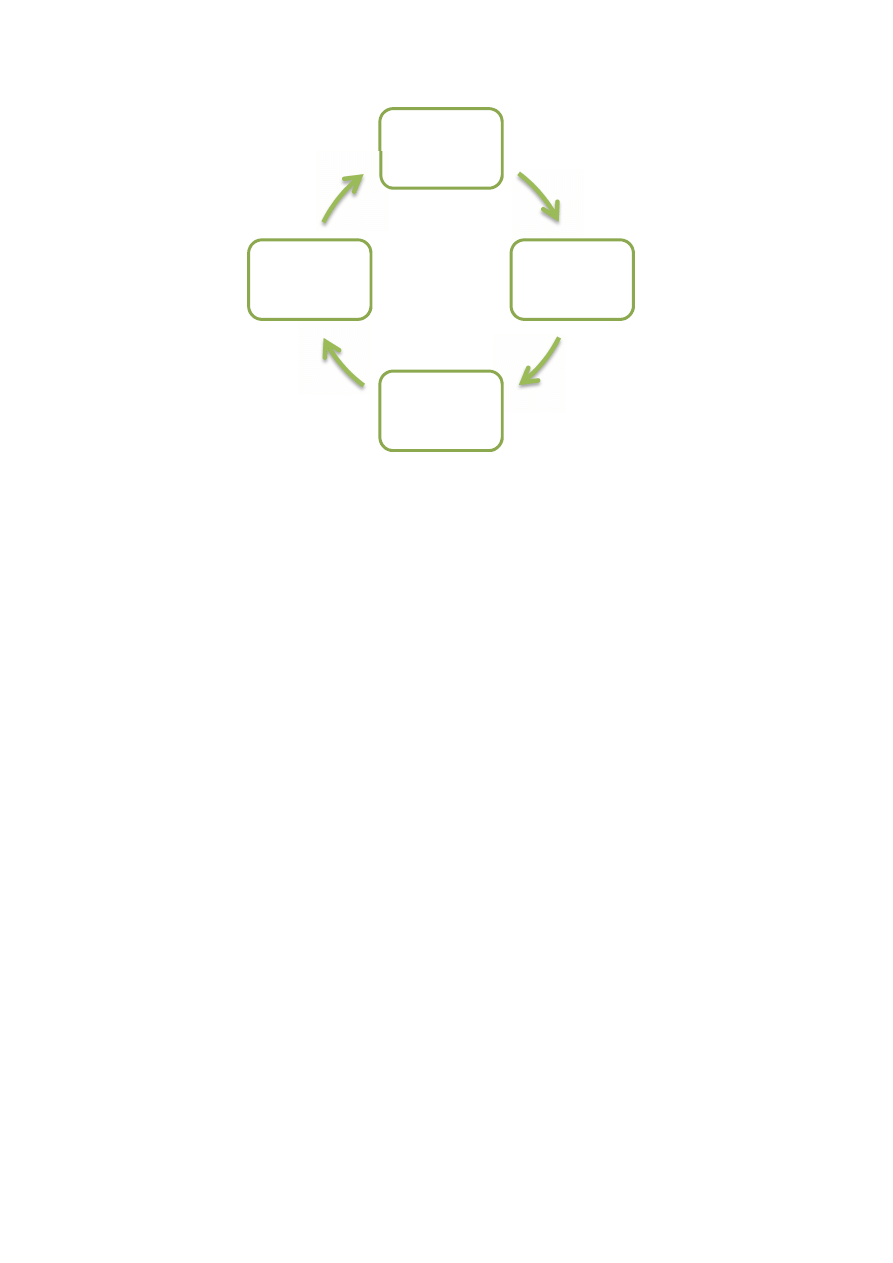

The management functions

Understanding the nature of a management process will be easier after a deeper study of the scheme of

management (see Figure 1.8).

Management is the process of planning,

organizing,

leading

and

controlling

of

individuals’ activities, focused on achieving an

established set of goals.

Figure 1.8. The process of management

Source: Adapted from [Robbins and DeCenzo2002, p. 35].

Main functions of the management process are:

•

Planning: it implies that managers think through their goals and actions in advance. Their

actions are usually based on some methods, plans, or the logic, rather than on the hunch. The

objects of planning are goals, ways and methods used to achieve established goals, required

resources, and particular activities.

•

Organizing: it means that managers co-ordinate human and material resources of the

organisation. The effectiveness of an organisation depends on its ability to transform its

resources into goals. The more integrated and co-ordinated work is, the more effective an

organisation can be. The effect of the organizing function is an organisational structure.

•

Leading: it describes how managers direct and influence subordinates, getting others to

perform essential tasks. By establishing the proper conditions, they help their subordinates do

their best.

•

Controlling: it means that managers attempt to assure that the organisation is moving toward

its goals. If any part of their organisation is on the wrong track, managers try to find out the

reason for this fact and set things right.

Generally, we may conclude that management is a process in which organisations transform and use

resources to achieve established sets of goals.

Organizing

Determining what

needs to be done, in

what order and by

whom

Leading

Guiding and

motivating all

involved parties

Controlling

Monitoring activities

to ensure that they

achieve

results

Planning

Defining goals and

establishing

action plans

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

test one rko, Test 1 i 2

one for you one for me worksheet count circle bw

one for you one for me worksheet count

one for you one for me worksheet connect bw

one for you one for me worksheet draw color count bw

tips for test takers b2 c1

Beatles For No One

Test 3 notes from 'Techniques for Clasroom Interaction' by Donn Byrne Longman

the Placement tests for Speakout ~$eakout Placement Test A

Test for functional groups

the Placement tests for Speakout Speakout Placement Test Instructions

ESL Seminars Preparation Guide For The Test of Spoken Engl

2007 04 Choosing a Router for Home Broadband Connection [Consumer test]

Minor data package v 7 05 (MCU SW 4 03 38) only for Field Test variant phones

KasparovChess PDF Articles, Sergey Shipov The Best One Qualifies for the World Championship!

the Placement tests for Speakout Speakout Placement Test A

NKJO British Culture Topic areas for the class test

więcej podobnych podstron