Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

By Steve Smith

Artist Biographies & Media Guide written by Mark Griffith

Edited by Joe Bergamini and Steve Smith

Transcriptions by Steve Smith

Engraving by Michael Dawson

Design and Layout by Joe Bergamini

Assisted by Willie Rose

Produced by Paul Siegel and Rob Wallis

Co-Produced by Steve Smith

STANDING ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

Copyright © 2008 Hudson Music LLC

All Rights Reserved

www.hudsonmusic.com

2

Foreword.......................................................3

Artist Biographies & Media Guide................3

Buddy Rich....................................................3

Art Blakey......................................................6

Max Roach...................................................10

Philly Joe Jones...........................................12

Elvin Jones...................................................13

Joe Dukes.....................................................16

Tony Williams..............................................19

John Riley....................................................25

Steve Smith..................................................27

“Standing on the Shoulders of Giants”.......30

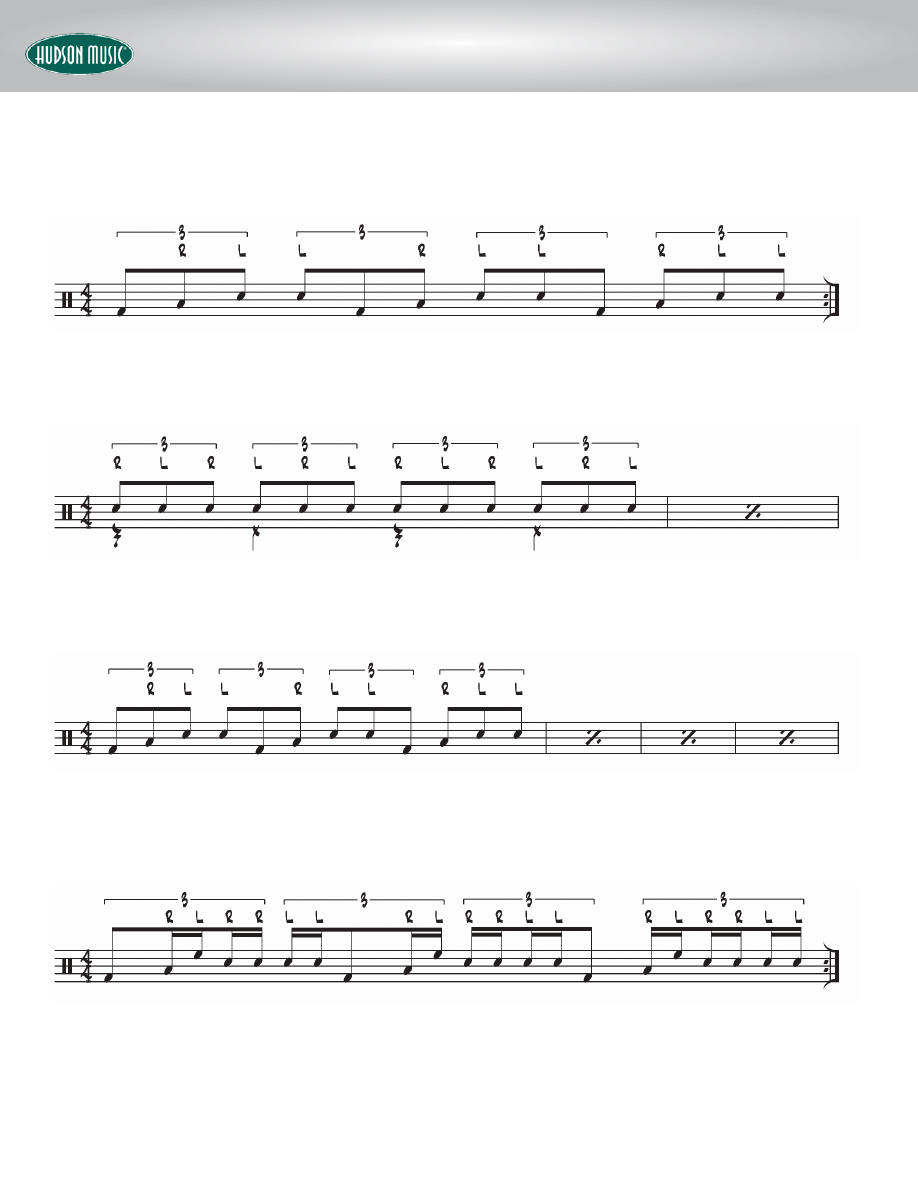

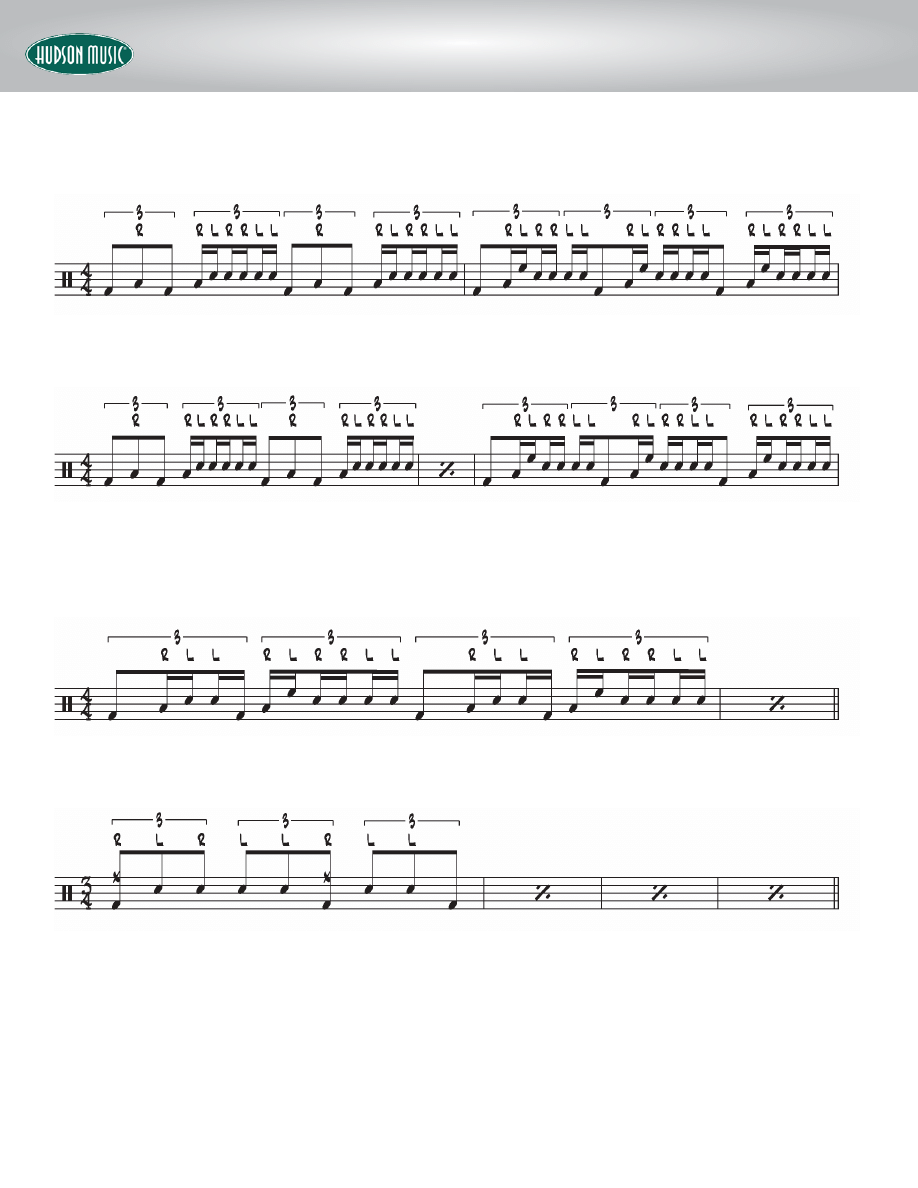

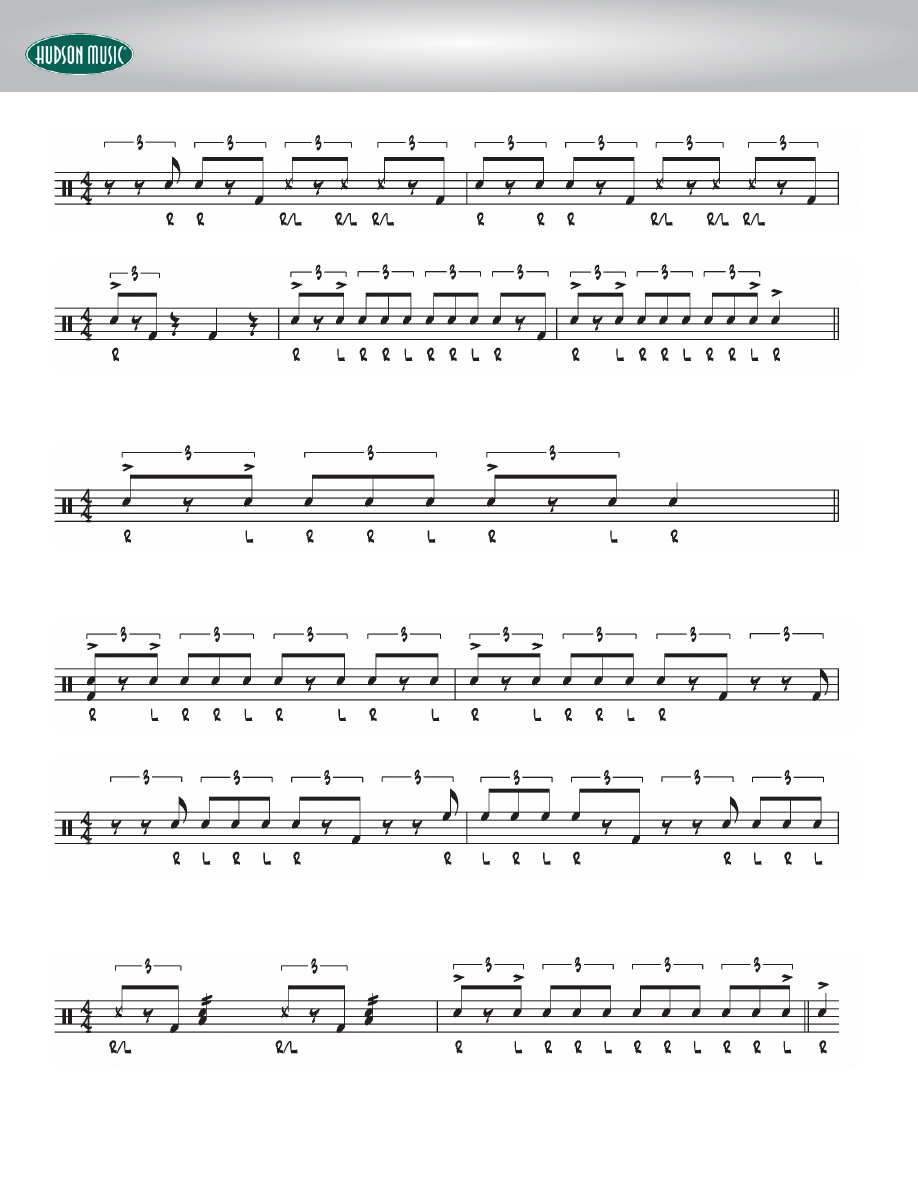

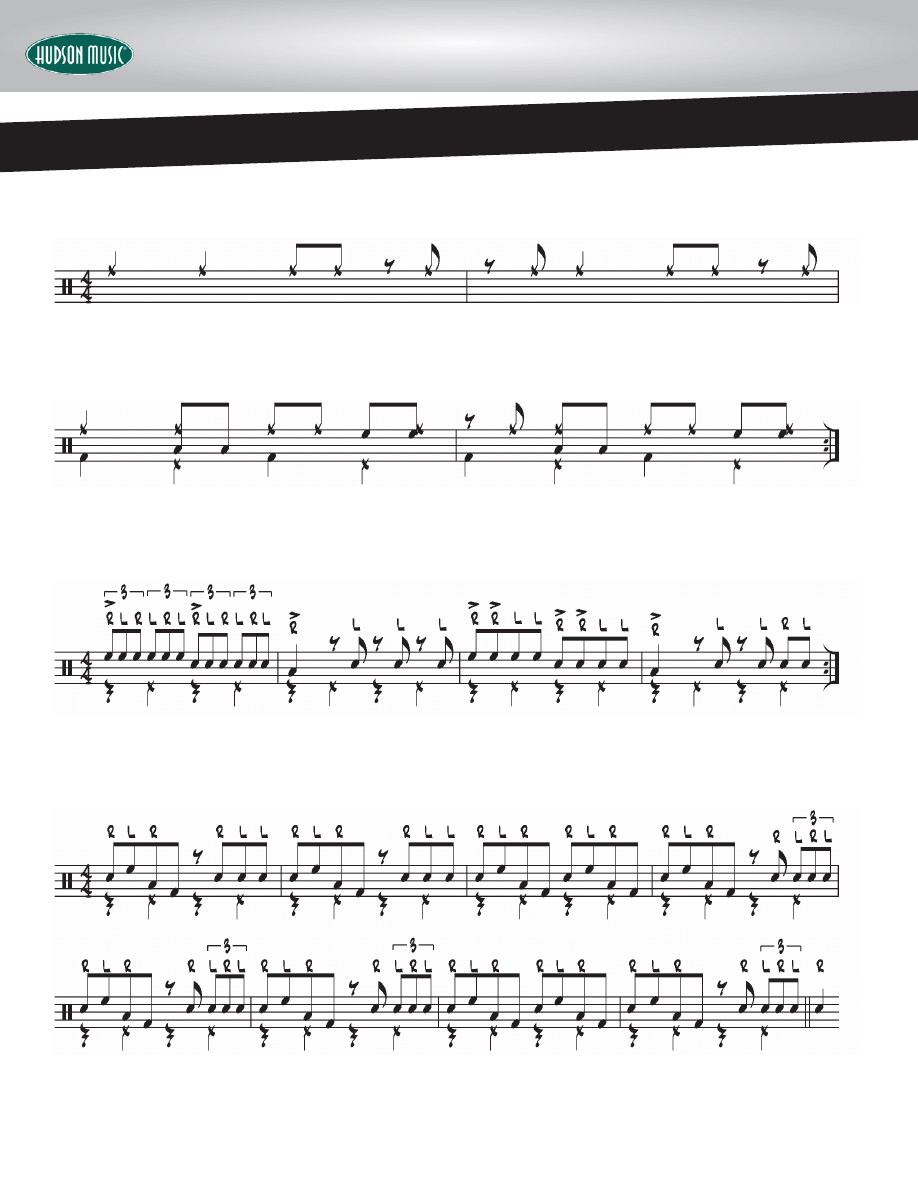

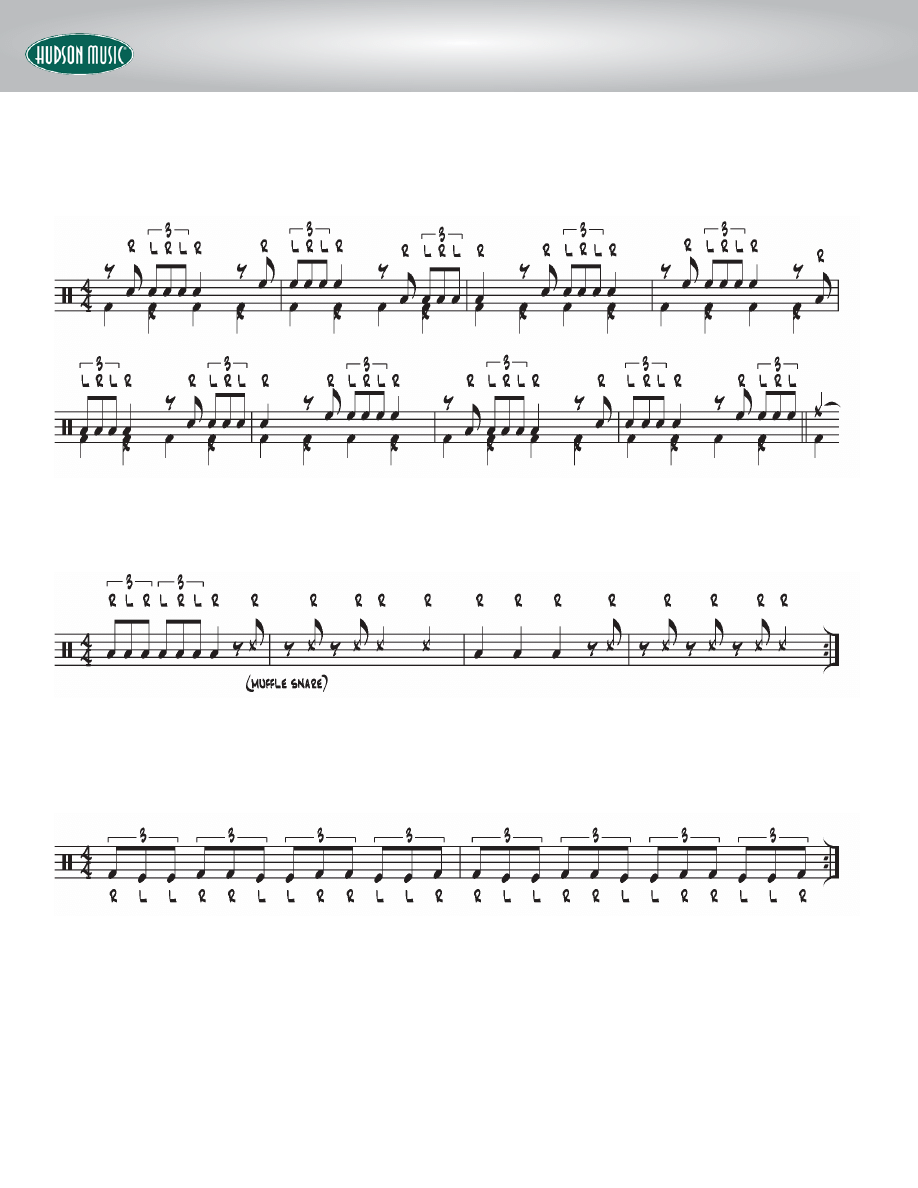

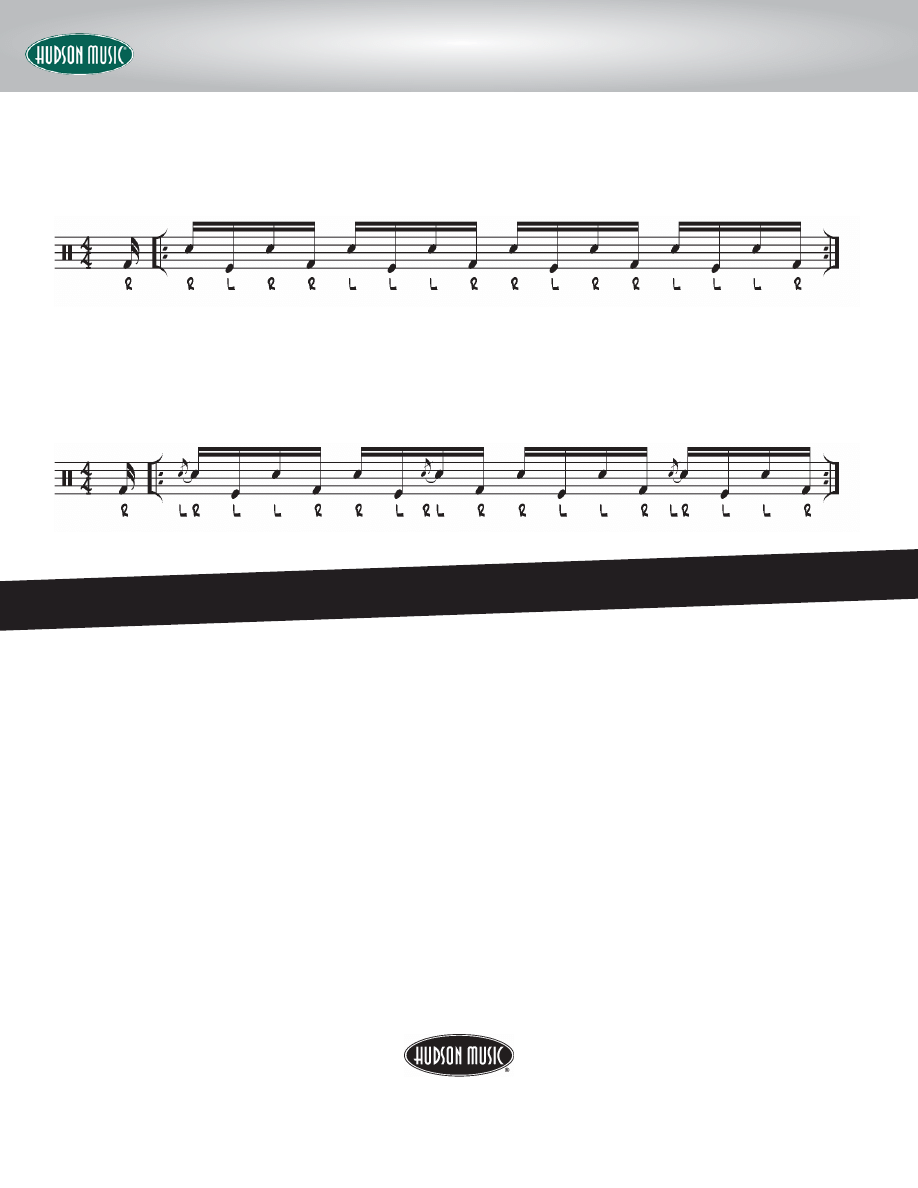

Musical Examples.......................................31

“Moments Notice”.......................................31

“Insubordination”........................................32

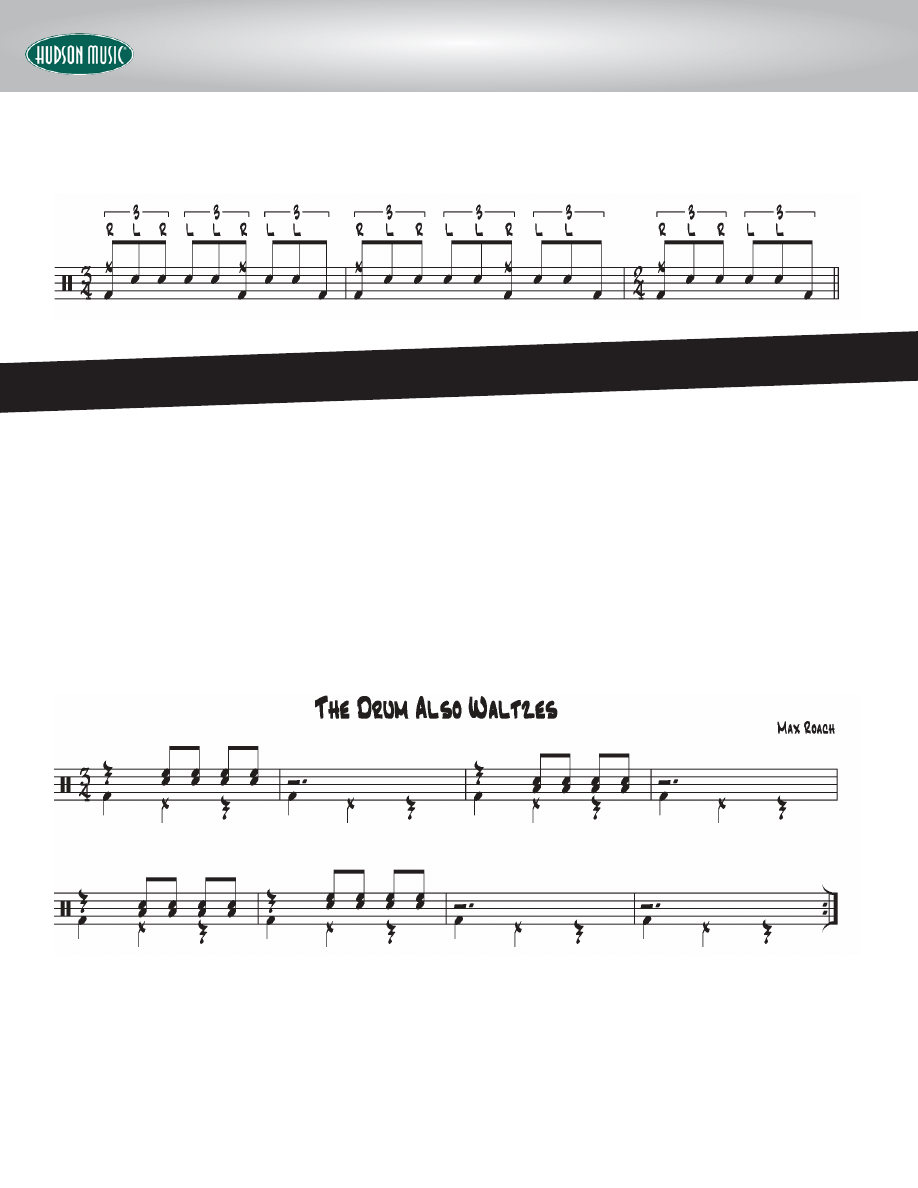

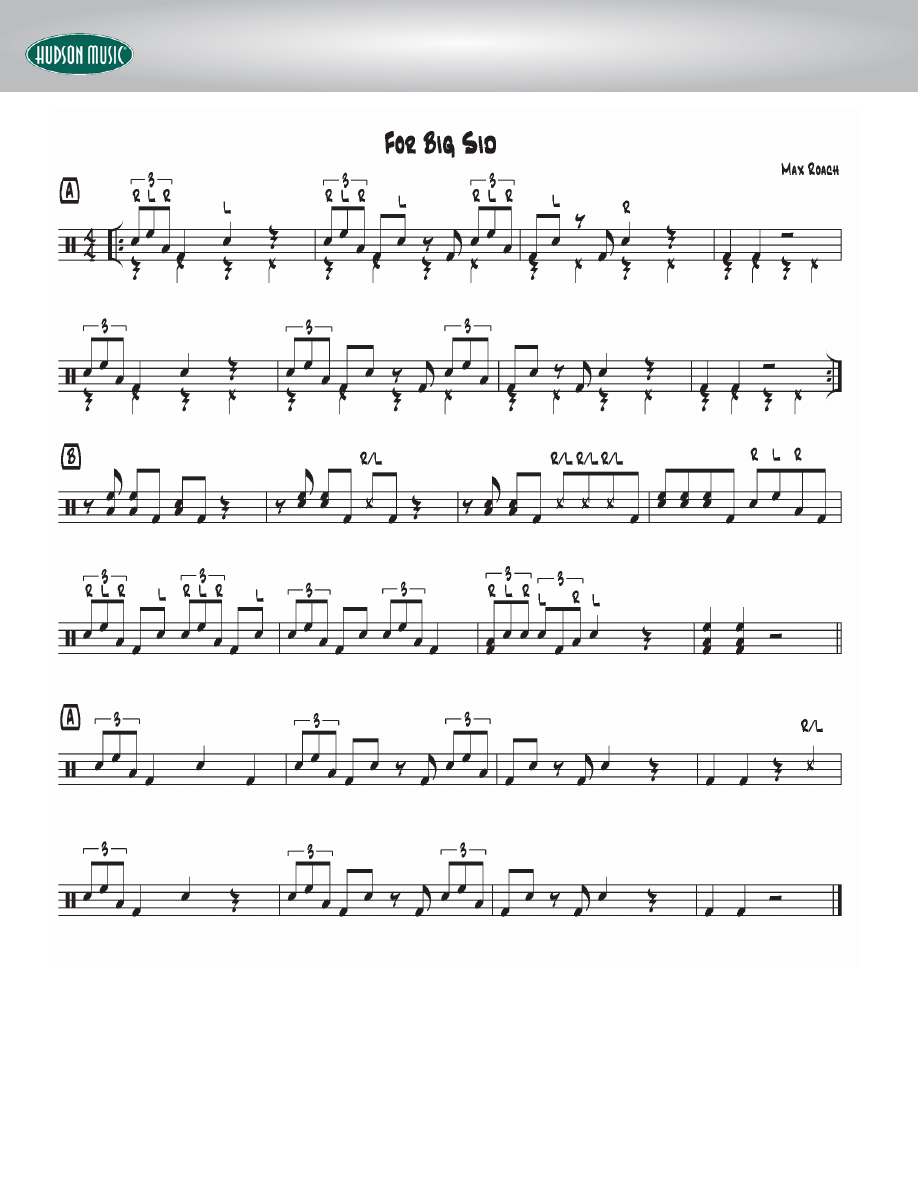

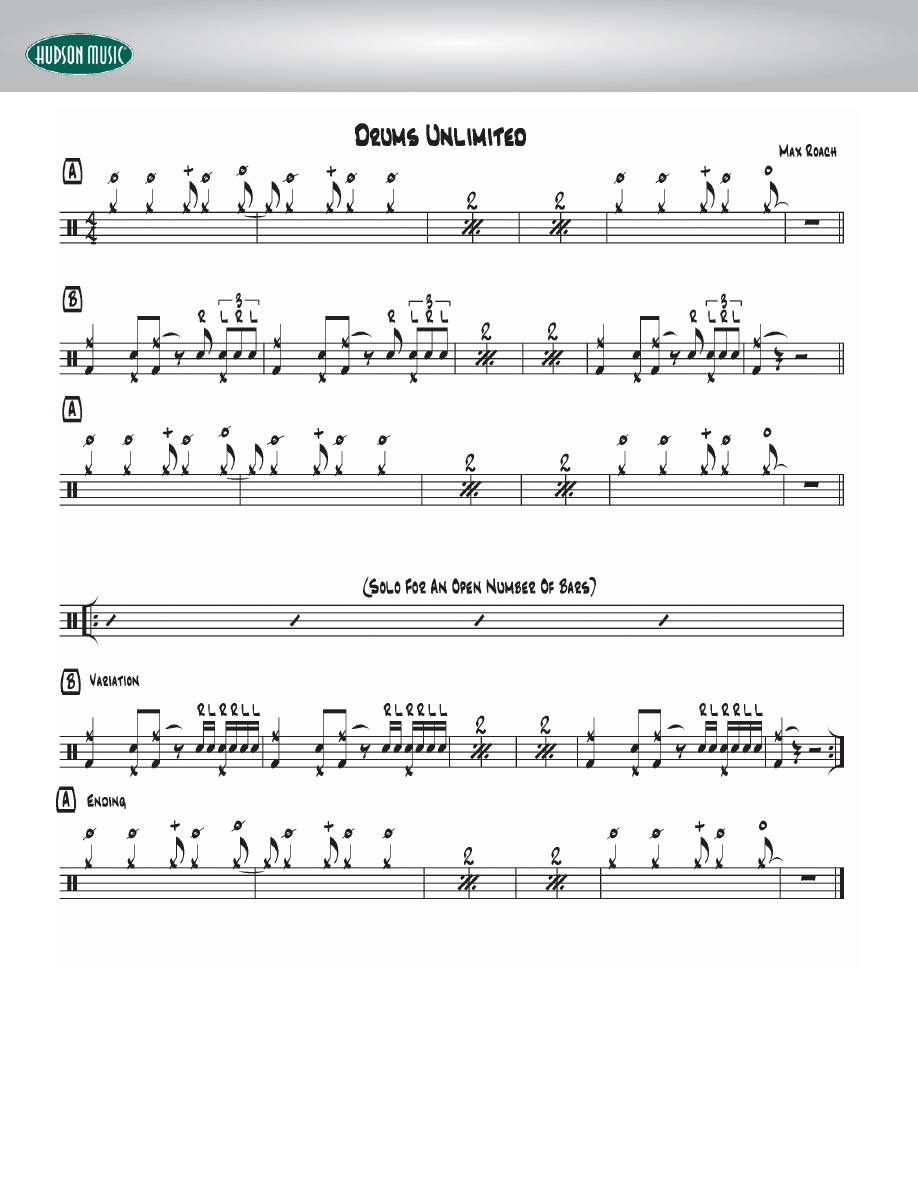

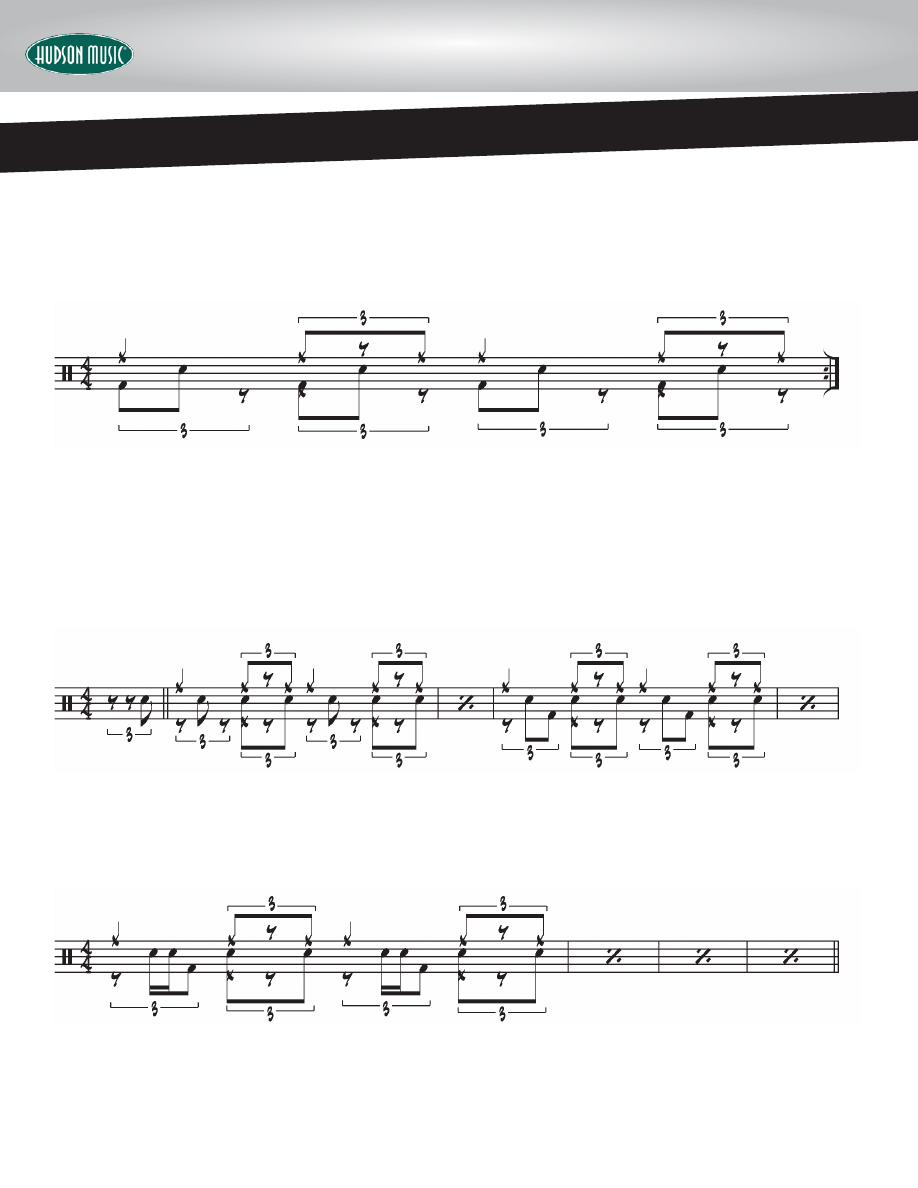

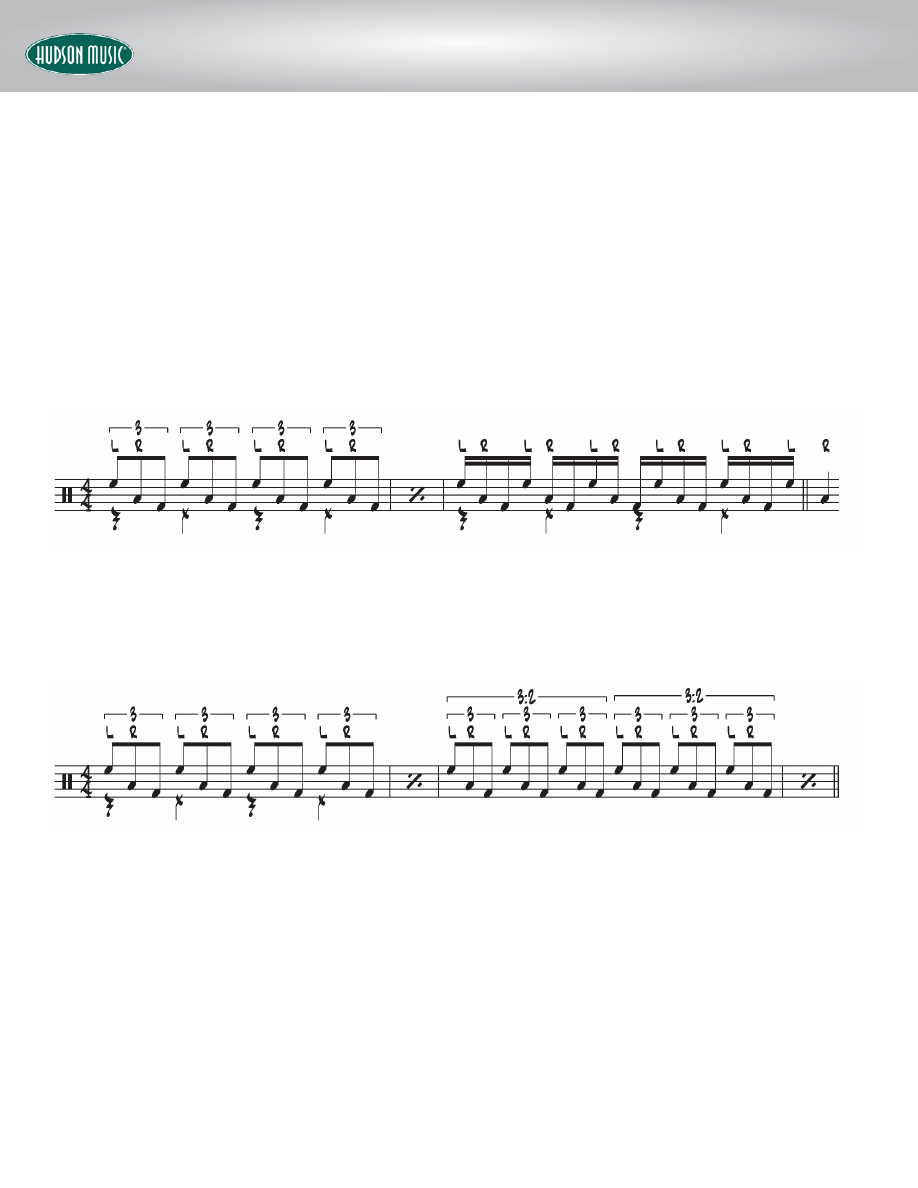

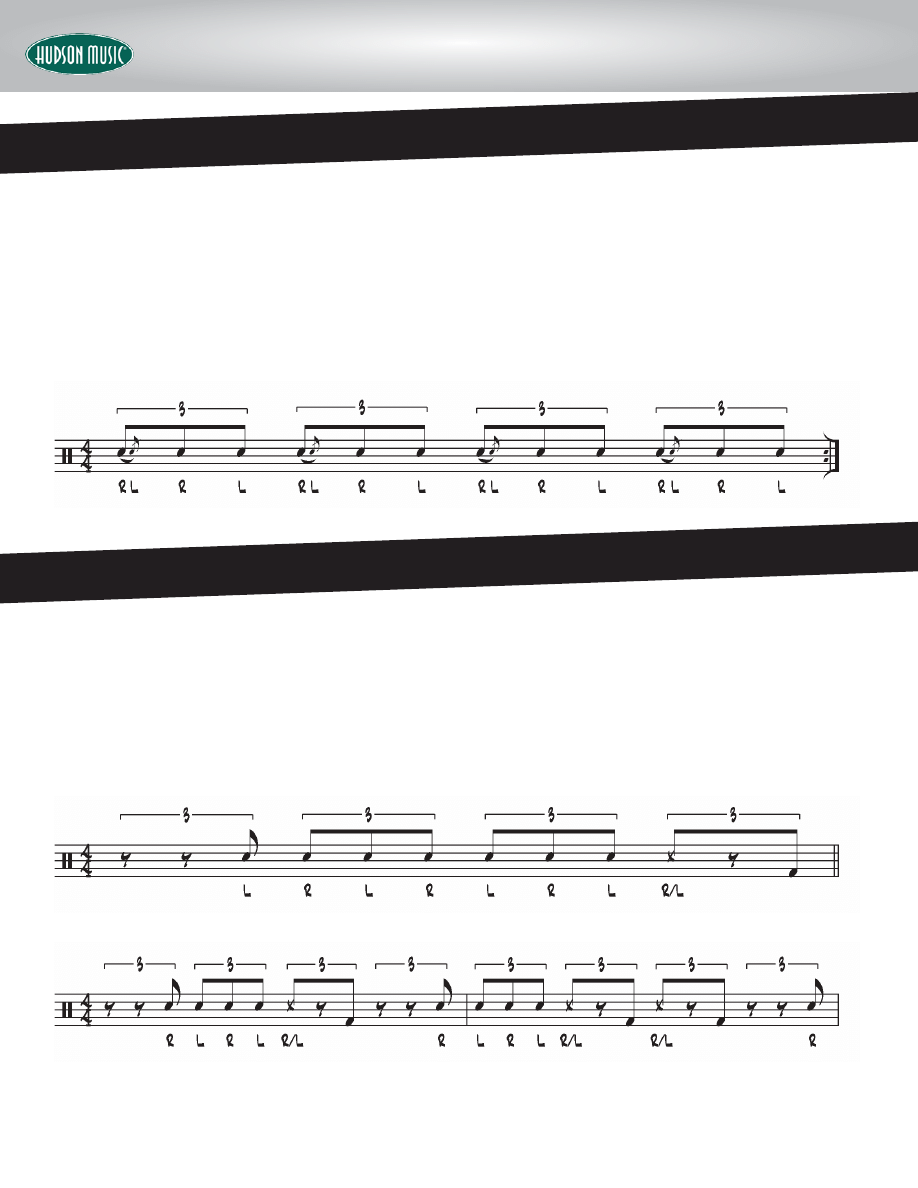

Max Roach...................................................36

“Three Card Molly”: Elvin Jones................39

“Sister Cheryl”: Tony Williams...................41

“Two Bass Hit”: Philly Joe Jones................41

“A Night in Tunisia”: Art Blakey..................43

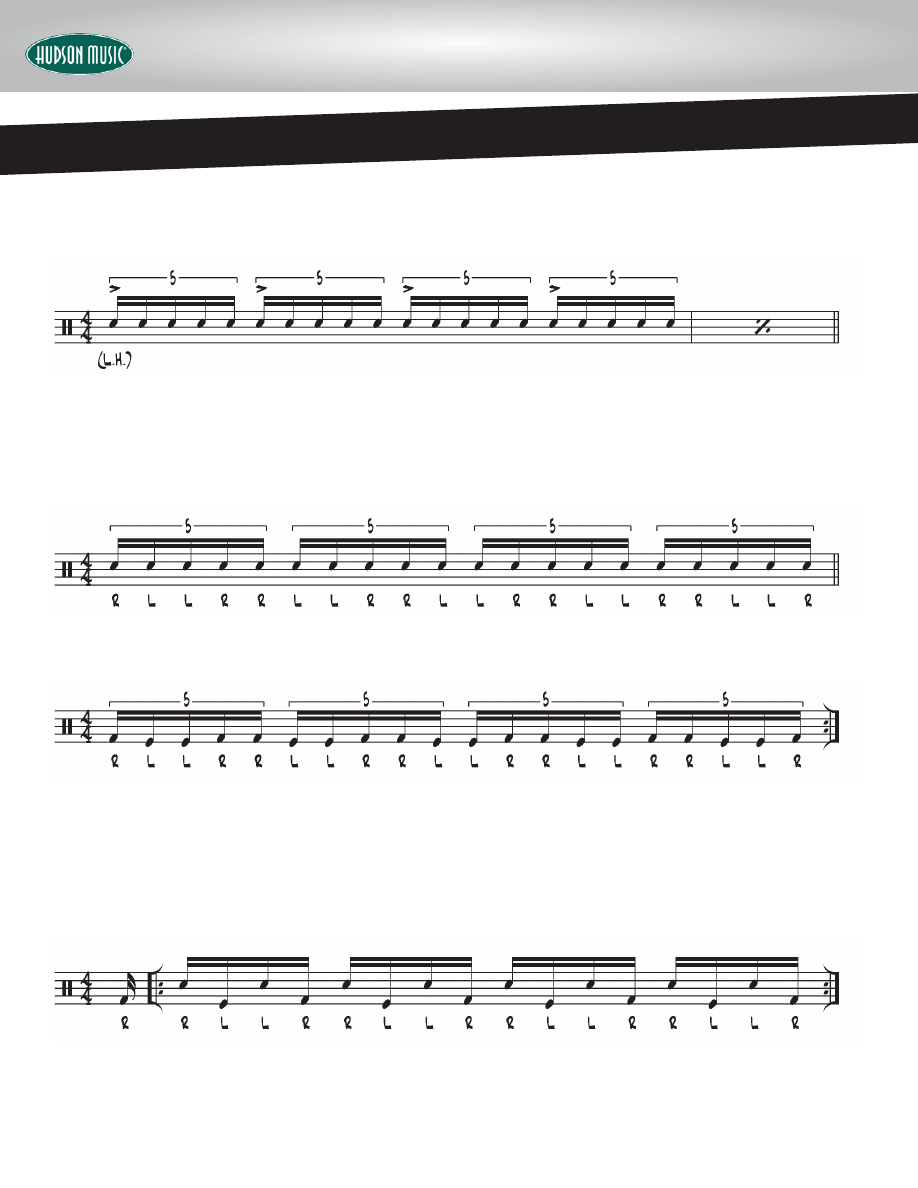

Solo in Fives.................................................45

Conclusion...................................................46

Drum Legacy DVD Chapter List..................47

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

STANDING ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

Table of Contents

3

In keeping with the theme of Standing on the Shoulders of Giants, Mark Griffith has written detailed

biographies and a suggested media guide that highlights the early influences, development, innovations

and legacy of the principal “giants” discussed in my Drum Legacy DVD. This unique approach will help

us appreciate and gain insight into the makeup of these very talented and inspiring gentlemen.

My own playing style occurs as a culmination of myriad factors: the time and place of my upbringing,

the instruction I have received, the many playing situations that I’ve been involved in, the in-depth study

of countless drummers that came before me, and the decisions I’ve made of what to play and when to

play it. Regardless of which styles of music you play, this is a universal way of learning to play an in-

strument, and of learning to play music. Mark Griffith brings these ideas to life in his vivid and percep-

tive writing.

- Steve Smith

Foreword

Featured Artist Biographies & Media Guide

By Mark Griffith

(drummer, recording artist, author

, historian)

Bernard “Buddy” Rich

(September 30, 1917 – April 2, 1987)

Buddy Rich was introduced to the music business through the vaudeville entertainment circuit as “Traps,

The Drum Wonder” when he was not even two years old. He went on to perform as a tap dancer and a

singer on the burgeoning entertainment circuit in the 1930s and ’40s. After devoting himself to drum-

ming’ he became influenced by Tony Briglia (of the Casa Loma Orchestra), Chick Webb, Gene Krupa, Jo

Jones, and later, Shadow Wilson. During his career he played with musicians from the entire history of

jazz: from Dixieland to swing to bebop and even fusion. He first recorded in 1937 with swing and Dix-

ieland clarinetist Joe Marsala (replacing drummer Danny Alvin). These recordings are available on

Marsala’s Classics 1936-1942. Buddy spent 1938 with Bunny Berigan’s band, 1939-1942 with Tommy

Dorsey’s band, and in 1945 he formed his own band. In his band, Buddy set the musical bar very high

for all of the musicians that surrounded him, and even higher for himself.

Buddy Rich is often referred to as “the greatest drummer who ever lived.” However, to truly gain insight

to the musical greatness of Buddy Rich, you should first focus on his work as a sideman. Long before he

became a star drummer/bandleader, Buddy was busy performing and recording with his peers as a side-

man. This was where you really heard Buddy’s musicianship, and how he drove and complimented other

musicians. A perfect example is on the phenomenal 1946 Lester Young Trio recording with Lester,

Buddy, and Nat “King” Cole. Buddy’s early involvement with the Jazz At The Philharmonic tours (pro-

duced by Norman Granz) may have been the impetus for his recordings with Ella Fitzgerald, Bud Pow-

ell, and Charlie Parker. These numerous recordings are all outstanding. On Ella and Louis, Buddy

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

STANDING ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

4

complimented and supported one of the great jazz singers, Ella Fitzgerald, and the inventor of small

group jazz, Louis Armstrong, with authenticity, taste, and musicality. On Pres & Sweets (Lester Young

and Harry “Sweets” Edison), Buddy’s sense of no-nonsense, driving swing is superb. On The Genius Of

Bud Powell, Buddy and bassist Ray Brown hook up nicely to provide percolating support as Bud burns

up the piano. Thelonious Monk appreciated Buddy’s strong, yet often overlooked sense of groove. On the

recording Bird & Diz, Buddy adapted his swing drumming roots to the bebop environment, leaving room

for Monk’s quirky comping as well as the soaring solos of Parker and Gillespie. Also check out Buddy’s

more restrained playing with pianists Art Tatum, Oscar Peterson, and Teddy Wilson.

Benny Carter's The Urbane Sessions presents an interesting look at Buddy Rich. Not only is this a breath-

takingly beautiful and sublime recording, but this collection also features Buddy with two of his lesser-

known drum contemporaries: Alvin Stoller and Jackie Mills. It is a wonderful opportunity to compare

and contrast these three talented drummers. Alvin and Buddy had many of the same gigs; in fact, Stoller

replaced Buddy when he left Tommy Dorsey’s band (drummer Mo Purtill also had the daunting task of

“replacing” Buddy in the Dorsey band). Interestingly, when Buddy played in a more supportive role,

Buddy and Alvin sounded very similar. Stoller is on scores of superb recordings by leaders such as Roy

Eldridge, Coleman Hawkins, Erroll Garner, and Frank Sinatra. Drummer Jackie Mills came out of the

same swing tradition as Buddy, and held many prestigious gigs as well. But like many drummers of the

day, Mills was overshadowed by the enormous spectacle of Buddy Rich. Mills’ resume includes record-

ings with Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman, and Harry James. There are hundreds of drummers like

Stoller and Mills throughout the history of drumming that have not received the attention that they de-

serve, yet have made huge contributions to the history of the instrument. All three of these drummers

make strong contributions to The Urbane Sessions by Benny Carter.

As Buddy Rich’s drumming skills grew and his reputation became more renowned, the entertainment

value of Buddy's spectacular drumming occasionally overshadowed his sense of musicality. Buddy knew

the importance of entertainment, and he learned many of his showmanship techniques from those who

came before him. Chick Webb, Papa Jo Jones, and Sid Catlett were all stick-wielding showmen, but

Buddy—and Gene Krupa before him—permanently brought the drums to the front of the stage and made

the drum solo a spectacle of entertainment to behold.

Buddy’s own recordings span the 30-plus years that he worked as a bandleader. During this time,

Buddy’s band was among the hardest-working bands in the music business. Nightclubs, casinos, dances,

television shows, high schools, colleges, shopping malls, and private affairs were all opportunities for the

Buddy Rich Big Band to get off of the bus and work. Throughout this time, Buddy made many record-

ings of his hard-working ensembles. Perhaps the first high-quality recording by Buddy and his band is

This One’s For Basie (1956). This album delivers exactly what the title describes: a swinging, in-the-

pocket affair that the Count would have dug. Ten years later, Buddy’s Swingin’ New Big Band record-

ing included an infamous arrangement of songs from West Side Story. The “West Side Story Medley”

would remain with Buddy for his entire career, and prove to be a true crowd-pleaser that always featured

lengthy and outrageous drum solos. “Channel One Suite” from 1968’s Mercy, Mercy was another drum

feature and crowd favorite.

Around this time, Buddy began to include arrangements of pop tunes such as “Uptight (Everything’s

Alright),” “Norwegian Wood,” and “Ode To Billie Joe,” as well as soul-jazz standards such as “Mercy,

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

5

Mercy, Mercy” and “Sister Sadie” in his performances. His “swinging” sense of straight-eighth rock time-

keeping was a truly unique time feel that made these arrangements come to life. In an era where many

bandleaders were fusing jazz and rock, Buddy was one of the only musicians that fused the big-band

swing tradition, small-group jazz, and rock. Buddy Rich’s own brand of “fusion” had a style all its own.

Throughout the 1960s and ’70s his recordings Big Swing Face, Keep The Customer Satisfied, and The

Roar of ’74 inspired countless drummers to incorporate different musical genres into their own ap-

proaches, while grooving hard and playing the drums with an unrelenting fire and virtuosity.

Some of the most revered Buddy Rich recordings documented his “battles” with other virtuoso drum-

mers. In 1959, Rich versus Roach proved to be an interesting and influential contrast in approaches,

where each drummer led his quintet in a battling format. 1952’s The Drum Battle paired Buddy and

Gene Krupa with a band of all-stars, but only featured them together on one track. The recording Are

You Ready For This? featured Buddy and Louis Bellson battling on the song “Slides and Hides.” Al-

though this title is hard to find, it is well worth looking for. His televised battles with “Tonight Show”

drummer Ed Shaughnessy garnered even more attention for the art of drumming. Buddy even made a

record with the legendary Indian tabla player Ustad Alla Rahka called Rich Ala Rahka.

Seeing Buddy Rich play was one of the most thrilling musical experiences one could ever have. There are

fortunately many DVD’s currently available that highlight Buddy’s brilliance. Buddy Rich: Jazz Legend

1917-1987 (Alfred Publishing Company) gathers many of the best clips of Buddy in performance, and

presents them in chronological order in an amazing look at his life and career. Live at the 1982 Montreal

Jazz Festival (Hudson Music) and the recently released Live In ’78 (on the Jazz Icons series) are awe-

inspiring and helpful in studying Buddy’s drumming.

There are also some very good books about Buddy. Jazz singer Mel Torme is the author of Buddy's bi-

ography, Traps, The Drum Wonder. Doug Meriwether's Mister, I Am The Band - Buddy Rich: His Life

and Travels includes an excellent discography by Clarence C. Hintze with dates and locations of record-

ing dates, radio broadcasts, television shows, and performances. Upon careful study, you can see how

hard this band (and its leader) worked, and the distance that they traveled to spread the sound of big

band music. Buddy also followed in the tradition of Gene Krupa and Cozy Cole (who wrote the book

Modern and Authentic Drum Rhythms for the Teacher, Student, and Professional), and wrote an in-

structional snare drum book with Henry Adler, called Buddy Rich’s Modern Interpretation Of Snare

Drum Rudiments.

Buddy Rich was more than a phenomenal drum soloist. He was a relentless bandleader that demanded

100 percent from all of his musicians. He could demand this because he consistently delivered 110 per-

cent. In his long and storied career he entertained millions of music lovers, and inspired countless young

people to pick up a pair of drumsticks. Buddy had the true mark of a performing professional: he was

the definition of consistency. As a drummer, his timekeeping was instantly identifiable, and his won-

derful touch on the instrument was impeccable. In one way or another, Buddy Rich has influenced every

drummer that has ever picked up a pair of sticks, from Philly Joe Jones to Carmine Appice to Travis

Barker. He is an important part of a lineage of drummers who brought the drums into the spotlight.

Today, anyone who plays a drum solo or leads a band is carrying on the tradition of this lineage of out-

standing musicians, and walking in the footsteps of the great Buddy Rich.

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

6

Art (Abdullah Ibn Buhaina) Blakey

(October 11, 1919 – October 16, 1990)

Art Blakey had one of the most diverse careers in jazz drumming. He was a successful sideman, a sty-

listic pioneer, a bandleader, and ultimately a drumming icon. Not to mention that in jazz, there was no

bigger talent scout of up-and-coming musicians. He began playing the piano as a young man, eventu-

ally switching to drums, and he never looked back. Art spent his youth in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; the

hard-working, blue-collar attitude of this industrial capital never left Blakey’s unique character. Blakey

was one of the best storytellers in jazz, both with the sticks and without. For example, he would recall

the sound of the mine buckets dumping coal as the inspiration behind his press roll, with its sudden

crescendo—and there has never been a better description! His hard-driving timekeeping and no-frills,

bold-faced attitude towards drumming can be traced back to his blue-collar roots.

Art Blakey’s drumming is often identified by a relentless and insistent 2 & 4 on the hi-hat; a sizzling, thin

ride cymbal; and straightforward comping phrases. His drum sound was lower in pitch than his peers,

and had less sustain. A strong underpinning of the shuffle was present in his swing feel, and when he laid

into a full-blown shuffle it could “wake the dead.” Blakey was one of the first jazz drummers to adopt a

decidedly Afro-Cuban approach, resulting a jazz mambo groove that became another Blakey trademark.

Blakey’s early polymetric approach opened the door for Elvin Jones’—and eventually Tony Williams’—

more advanced polyrhythmic styles. This often resulted in a tribal and even African “resonance” to the

rhythmic interplay. Blakey attributed this to his several trips to Africa, although these trips are still of-

ficially undocumented, and claimed by some to be fabrications that can be credited only to Blakey’s rep-

utation as a great storyteller.

While Art Blakey is often recognized as one of the most important contributors to “hard bop” drum-

ming, his approach was rooted in the swing tradition of Chick Webb, Papa Jo Jones, Cozy Cole, and Big

Sid Catlett. His approach was less refined than his peers, and fell somewhere between Kenny Clarke and

Max Roach. Blakey’s movements behind the drum set were often very exaggerated, his use of dynamics

was dramatic, and his bands were always entertaining to watch. And while it was Art’s timekeeping that

had the most indelible influence on drummers, his soloing was a show unto itself. Art’s extended solos

were based upon groove and polyrhythmic dexterity. Like Max Roach, his solos always had a distinct

form, and were based upon thematic material, not technique. Even when he recorded his only unac-

companied drum solo, called “The Freedom Rider” (from the album of the same name), there was an ob-

vious sense of form and groove. Art Blakey’s influence on jazz drumming is still as strong today as it was

in the ’50s and ’60s. Many jazz drummers have acknowledged Blakey’s impact, including Ralph Peter-

son, Carl Allen, Cindy Blackman, Cecil Brooks III, Lewis Nash, Winard Harper, and Marvin “Smitty”

Smith. However, due to the sheer breadth of his career output—and the popularity of other, more “dru-

mistic” drummers—Blakey’s contribution remains somewhat unappreciated by many drummers today.

Art Blakey first recorded in 1942 with pianist Mary Lou Williams. Williams came from Andy Kirk and

his Clouds Of Joy band (with drummer Ben Thigpen). She had a transitional approach that was rooted

in swing but laid the groundwork for bebop. The same can be said about Blakey. Art then went on to a

short stint with the highly influential Fletcher Henderson Big Band. In 1944, Blakey gained a great deal

of attention when he joined the great Billy Eckstine band, replacing Washington DC drummer Charlie

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

7

Buck. As a young drummer, you could not have picked two better gigs than playing with Henderson and

Eckstine; many of the future stars of jazz came through those two bands. In Eckstine's band alone, Blakey

played with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Sarah Vaughn, Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt, Dexter Gordon,

Miles Davis, Kenny Dorham, and Fats Navarro. Many of these musicians would later call on Blakey for

record dates and live appearances. With Eckstine, Art’s sloshy hi-hat sound was similar to Papa Jo’s sig-

nature hi-hat approach, and the excitement that Blakey creates is reminiscent of Chick Webb. The CD

set Billy Eckstine: The Legendary Big Band 1943-1947 captures this band at its peak. When Eckstine

broke up his band in 1947, Blakey seized the opportunity and formed his own group, Art Blakey’s Sev-

enteen Messengers. Then in 1948, Blakey played on James Moody’s Modernists, appearing with conguero

Chano Pozo. The album contains some of the earliest fusion of Afro-Cuban music and jazz. Today, this

recording is included on New Sounds - Art Blakey's Messengers/James Moody & His Modernists. On

this CD, You can hear Pozo’s strong influence on Blakey, and Blakey’s swing-era timekeeping.

In 1947, Blakey recorded with Thelonious Monk for the first time. In the words of Thelonious’ son, drum-

mer T.S. Monk, “Blakey was the first drummer to frame Monk’s music correctly.” Monk and Blakey were

truly peers: they had similar backgrounds, and were very close in age. This kinship comes through loud

and clear on Monk’s Genius Of Modern Music Volume 1, and 1952’s Volume 2. Blakey and Monk would

collaborate often through the years, but their best recording together occurred in 1958 on Art Blakey’s

Jazz Messengers with Thelonious Monk. This recording really shows Blakey’s reduction of the bebop

style of drumming: He has stripped out all of the unnecessary notes and patterns, taking a decidedly

swing-era approach to Monk’s music—without framing it as such. What Max Roach did for Charlie

Parker’s music, Art Blakey did for Monk.

The pairing of Blakey with Charlie Parker was stupendous. Parker’s 1950 recording One Night In Bird-

land is priceless. It features the only pairing of Blakey and Parker on record. This is unfortunate be-

cause the pair played together so well. Blakey brought out a different side of Parker. Art left a lot of

space, and Parker easily filled it up. “One Night” is also one of Parker's only live recordings on which the

performances extend beyond the typical three-minute limit of the recording technology of the day. The

cuts from this live broadcast average seven minutes in length, and feature Blakey manning the pace of

this groundbreaking music. This recording makes an interesting comparison to the Dizzy Gillespie/Char-

lie Parker Town Hall recordings of 1945, which feature Max Roach and Big Sid Catlett. For an even more

interesting comparison of Roach and Blakey, listen to Roach’s solo on “Wee,” from the 1953 Jazz at

Massey Hall concert recording. In it, Max pays such obvious homage to Blakey that it is hard to believe

that you aren’t actually listening to Blakey himself: the mambo pattern between the toms, the five-stroke

rolls around the set—every “Blakeyism” is there. It’s an inspiring listen.

Another piece to the early Blakey drumming puzzle is his work with Miles Davis. The two had played to-

gether in the Eckstine band, and Miles looked up to Blakey. This bond is strong on the newly-issued

Miles Davis recording Birdland 1951, which shows Blakey in full-on bebop mode. There are some tem-

pos here that rival some of Max’s fastest, and while Miles’ playing isn’t at its best, Blakey sets a fire be-

neath everybody. Also from 1951, Miles’ Dig is one of the first studio recordings that extended the

three-minute-per-tune time limit. These recordings offer a huge drum lesson; you can hear how Blakey’s

drumming framed the arrangements. The drummer is the de-facto arranger of every ensemble. The

mood and dynamic set by the drummer often shapes the soloists’ approaches into a spontaneous

arrangement that differs each night. The drummer can vary the orchestration of time-keeping sounds

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

8

(hi-hat, ride, brushes), the texture of accompanying sounds (brushes, cross stick, bells of the cymbals,

short dead strokes, legato sounds, etc.), and the lilt of the time flow to inspire one-of-a-kind-

performances from the soloists. Blakey was a master of this. On Dig you hear Blakey shaping the dif-

ferent soloists (Miles, Sonny Rollins, Jackie McLean, Walter Bishop) into a cohesive unit, and producing

a spectacular recording. Drum-wise, the fours on “Denial” are a textbook for jazz drumming independ-

ence, and the backbeats and press rolls on “Out Of The Blue,” and “Bluing” are vintage Blakey.

Art Blakey often played on recordings that members of his Jazz Messengers made outside of the band.

Selecting his best work as a sideman is difficult; Art was a consistently stellar performer. However, Sax-

ophonist Hank Mobley’s classic Soul Station is one of Art Blakey’s finest recordings as a sideman. The

title track is a quintessential example of the Blakey shuffle, with Art never letting go of the groove. His

time feel is the perfect balance of an insistent 2 & 4 on the hi-hat, a swinging ride-cymbal pattern, and

bubbling ghost notes combined with dead-stroke backbeats on the snare drum. “This I Dig of You” and

“If I Should Lose You” are textbook versions of swing, and nearly every performance from this record-

ing is a finger-poppin’ drum lesson. Pianist Horace Silver’s Trio recording of 1953 offers yet another

side of Art Blakey’s early style. While Silver would become a key ingredient in the original Jazz Mes-

sengers, in 1953 Blakey was a sideman on Silver’s first recording. Blakey lightened his approach greatly

for this date, sounding a great deal like his fellow Pittsburgh native Kenny Clarke, and even a little like

Shadow Wilson. Over the years Blakey wasn’t known for his work with pianists in a trio setting, but his

melodic drumming on this date is proof that he excelled in this format. Another thing of special note on

this recording are two duets between Blakey and conguero Sabu, continuing Blakey's contribution to

the fusing of Afro-Cuban music and jazz. Blakey interpreted many of the hand-drumming techniques

that he saw congueros using, and applied them to the drum set. He often changed the pitches of his

drums by applying pressure to the heads, and soloed with mallets producing a dry sound similar to hand

drums. Later, in 1955, Kenny Dorham’s Afro-Cuban featured Blakey with master conguero Carlos

“Patato” Valdes. Together they weave a tapestry of influential Afro-Cuban jazz.

Though he excelled on numerous record dates as a sideman, Art Blakey is best remembered for leading

The Jazz Messengers. The many editions of this band relentlessly toured the world, spreading the pop-

ularity of jazz with sincere and memorable performances. For the personnel of his band, Blakey became

one of jazz’s greatest talent scouts. Musicians such as Benny Golson, Lee Morgan, Horace Silver, Clif-

ford Brown, Wayne Shorter, Keith Jarrett, Chuck Mangione, Stanley Clarke, Wynton Marsalis, and Bran-

ford Marsalis all found success in Blakey’s bands. (Jarrett and Mangione both appear on the wonderful

yet forgotten Buttercorn Lady). There were numerous Jazz Messenger lineups, and even more record-

ings (I review them in detail in my “Artist on Track” articles in the October and November 1999 issues

of Modern Drummer magazine). Like Miles Davis, Blakey allowed each version of his band to develop

its own sound and approach. In the beginning, the Messengers featured Clifford Brown, Lou Donaldson,

and Horace Silver. This edition of the group was a bebop machine. A Night At Birdland Vols. 1 and 2 are

among the best bebop-era recordings ever. The soloists all had very different approaches and Blakey

gave them personalized support. These recordings also spotlight Art playing with bassist Curly Russell.

These two musicians had a wonderful hook-up that made the beat a little lighter than previous bebop

recordings. Also check out Blakey and Russell’s telepathic connection on Clifford Jordan and John

Gilmore’s Blowing In From Chicago. And speaking of blowing, Johnny Griffin’s 1957 record A Blow-

ing Session—featuring Blakey igniting John Coltrane, Hank Mobley, Lee Morgan, and Griffin—is the

definition of the term “jam session.”

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

9

The next edition of the Jazz Messengers featured Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley, and Horace Silver, and

they brought with them a catalog of new tunes and a funkier approach that became known as “hard

bop.” This band is best heard on Live at The Cafe Bohemia Vols. 1 and 2. When Benny Golson, Lee Mor-

gan and Bobby Timmons joined the band, the Jazz Messengers hit their popular stride, with tunes like

“Moanin,’” Blues March,” and “I Remember Clifford” becoming jazz standards. Moanin’ is truly a clas-

sic jazz album. This version of the band also appears on the Jazz Icons DVD Art Blakey Live In 1958. The

1960 edition of The Messengers, with Wayne Shorter stepping into Golson’s position, hit its artistic

stride. This lineup is featured on the Mosaic Box set The Complete Blue Note Recordings Of Art Blakey’s

1960 Jazz Messengers—an essential collection of nine discs by this band. According to bassist-histo-

rian John Goldsby, when bassist Reggie Workman joined the Messengers in 1962 he turned the band

“from a straight ahead bebop group into a freewheeling jazz experiment.” This resulted in the out-

standing recordings Ugetsu, Caravan, and Free For All. This fire-breathing band added youngsters

Cedar Walton, Curtis Fuller, and Freddie Hubbard into the mix, and they could not be contained. With

these younger musicians in the band, Blakey’s drumming became more modern. There was also another

soloist in the front line, which put Blakey’s accompaniment skills to even better use. Art would let his

time float occasionally with this group, probably due to the influence of younger drummers such as Tony

Williams and Elvin Jones (both of whom he had influenced years before). Listen to his elastic time feel

on “Caravan” and “This Is For Albert.” But these tunes only hinted at what was to come. The recorded

height of this edition of the band came on the title track of 1964’s Free For All. This album rivals the

Coltrane Quartet in its sheer electricity, and is an unarguable classic. Their next record, Indestructible,

comes close to its legendary predecessor, which is no small task.

Finally, I’ll mention a group of recordings that has been overlooked by the drum community for far too

long. Art Blakey felt a kinship with all of his percussive peers, including the African and Afro-Cuban

drummers who taught him so much. It was Blakey who arranged the 1960 concert and recording of

Gretsch Night At Birdland with Elvin Jones, Philly Joe Jones, and Charli Persip. Art also gathered drum-

mers like Roy Haynes, Specs Wright, Art Taylor, Philly Joe Jones and Papa Jo Jones, along with African

and Afro-Cuban percussion legends including Ray Baretto, Sabu, and “Patato” Valdes in the studio to

record percussion ensemble pieces. The results of these sessions, Orgy In Rhythm Vols. 1 and 2, Drum

Suite, Holiday For Skins Vols. 1 and 2, Drums Around The Corner, and The African Beat, all featured

a strong camaraderie between the drummers, not to mention stellar performances.

Art Blakey had a wonderful sense of being totally in the moment when he played. When he played he re-

acted to all of the contributions from the musicians in the band—he heard everything! Music drove his

drumming, and his drumming drove the music. Perhaps Art himself said it best when he stated, “In jazz,

you get the message when you hear the music.” As we have seen, there are many ways to hear Blakey’s

music. There are also many DVD’s to see Art Blakey’s drumming. The previously mentioned Art Blakey

Live in 1958 and TDK’s 1976 Jazz Messengers are highly recommended, as is John Ramsay’s book Art

Blakey's Jazz Messages (Alfred Publishing Co.). But the lessons are in the groove and the signature

sound that Art Blakey created. Excitement emanated from the drums when Art Blakey played them. His

drumming was a joyful and sincere “free-for-all” for all to enjoy.

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

10

Maxwell Lemuel “Max” Roach

(January 10, 1924 - August 16, 2007)

Max Roach was an inspirational human being. He was born in rural North Carolina, and came to New

York City to attend the Manhattan School of Music. He first recorded in 1943 with Coleman Hawkins,

and became a regular on the groundbreaking 52nd Street music scene. Max became the house drummer

at Monroe’s, and will always be associated with the music he helped create, bebop. He performed and

recorded with every musician that had a part in creating modern small group jazz: Charlie Parker

(Swedish Schnapps), Thelonious Monk (Genius In Modern Music Volume 2), Bud Powell (Jazz Giant),

Charles Mingus (the duet “Percussion Discussion” from At The Bohemia), Dizzy Gillespie, (The Quintet

Live At Massey Hall), and Miles Davis (Birth Of The Cool). For drummers, there are fast tempos, and

then there are Max Roach fast tempos. For bandleaders, Max was always a portrait of maturity, taste and

virtuosity at the drums.

Many drummers laid the groundwork for Max Roach. He learned from the swing-drumming tradition

of Papa Jo Jones and Chick Webb. He inherited the baton of musicality from Cozy Cole, and absorbed

the melodicism of Big Sid Catlett. Kenny Clarke’s innovations helped create bebop drumming, but Max

Roach created the art form of modern drumming by wrapping all these advances into one package. Max’s

practice of interspersing accents during the time flow became known as “dropping bombs,” and was an

impetus of innovation in jazz drumming. Max Roach threw down the gauntlet, and drummers realized

that the bar had been raised.

Max’s blistering tempos and virtuosity with Charlie Parker in 1945 set the standard for all generations

of bebop and jazz drummers to follow. Discovered only recently, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie - Town

Hall, New York City, June 22, 1945, on the Uptown label, is quite possibly the best recording of bebop

available. Both Max Roach and Big Sid Catlett shine on it. This is Max’s best bebop drumming on record.

Max went on to co-lead a band with trumpeter Clifford Brown. His playing with this band defined mu-

sicality on the drums, and created a drumset vocabulary that is still used today. Max’s sense of lyricism

created drum solos and comping figures that could be sung, and his solos clearly stated the form of the

song. Max began to create longer rhythmic motifs, extended his phrases across the barline, and gener-

ally applied the new bebop language to the drum set. All the recordings that this band made, especially

Study In Brown, More Study In Brown, Brown and Roach Inc., and Clifford Brown and Max Roach,

are essential musical cornerstones of the jazz drumming vocabulary.

Possibly the greatest meeting of two musicians at the top of their game occurs on the 1959 recording Rich

versus Roach, featuring Buddy Rich and Max Roach. This controversial and unique recording remains

a favorite of today’s drumming greats, and for many it was an introduction to jazz drumming. This album

has prompted much discussion, and every exciting note from these two masters could, and should, be

analyzed. One interesting aspect of this recording didn’t come from a drum solo, but instead came from

what was happening during a drum solo. When Max led his own band, he often wondered why the other

musicians would stop playing during his solos. This led him to insist that he receive the same type of ac-

companiment as everyone else. On Rich versus Roach pianist Richie Powell comped behind some of

Max’s solos, and Max soloed over a walking bass line on the popular “Sing, Sing, Sing.” At the time,

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

11

these were not common practices, but Max insisted that the drum solo was equal in musical value to any

other solo. Max was a rare breed, a musician and a technician.

Max was well-known for his mastery of odd time signatures. In 1951, Thelonious Monk’s “Carolina

Moon” featured Max playing in 6/4. In 1956, Max played drums on Sonny Rollins’ “Valse Hot,” one of

the earliest 3/4 jazz waltzes. Also in 1956, Max and Clifford Brown played “Love is a Many Splendored

Thing” in 5/4 on the quintet’s Live at Basin Street. Max’s own group was performing the composition

“As Long As You’re Living” in 5/4 years before the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s popular “Take Five.” How-

ever, Roach didn’t record his composition until 1960 (“Take Five” was released in 1959). In 1957 Max

even released an entire record of compositions in 3/4 entitled simply Jazz in 3/4 Time.

Max’s influence went beyond the drums. His recordings Award Winning Drummer, Deeds Not Words,

and Max Roach +4, introduced jazz greats Booker Little, Hank Mobley, and George Coleman to the

scene. Max was also a busy social activist. In the ’50s and ’60s he became outspoken in his demands for

civil rights, producing such albums as We Insist: The Freedom Now Suite and Percussion Bitter Suite.

The latter featured singer Abbey Lincoln, who at the time was his wife.

When Max Roach performed, you never quite knew what you were going to hear. In 1966, the ground-

breaking Drums Unlimited included three unaccompanied drum compositions: “The Drum Also

Waltzes,” “For Big Sid,” and “Drums Unlimited,”—a tradition that he started in 1958 with his solo drum

piece “Conversation.” Max will be forever associated with these solos. Later, these compositions would

evolve into solo drum concerts, along with duet appearances and recordings with avant-garde stalwarts

like Archie Shepp, Anthony Braxton, and Cecil Taylor. Max’s solo drumming concept developed into

the band M’Boom, a recording and touring jazz percussion ensemble that Max founded with jazz drum-

ming mainstays Roy Brooks, Frederick Waits, Steve Berrios, and Joe Chambers. Since Max was one of

the first drummers to use a tympani with his drum set (while recording with Monk in the ’50s), a per-

cussion ensemble seemed like a natural progression. In the 1980s, Max’s own quartet and The Uptown

String Quartet (featuring his daughter Maxine on viola) merged, creating his Double Quartet.

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, all of Max’s various projects came together on two recordings: Max +

Dizzy Paris 1989, and To The Max. The first featured Max and Dizzy Gillespie playing duets from

throughout the history of jazz. Max also played his solo drum compositions, and there was an interest-

ing 32-minute interview. To The Max included many of Max’s different musical projects on an out-

standing two CD set.

Late in life, Max continued to be an active performer and was deeply involved in jazz education. He re-

ceived a MacArthur “genius” grant, participated in children’s music programs, taught at the collegiate

level, and was one of the first jazz musicians to collaborate with rappers. His performances and compo-

sitions always integrated tradition and innovation. His noted solo “Mr. Hi Hat” came from a concept

that Papa Jo Jones introduced, and that tradition is continued today by drummers Roy Haynes and Steve

Smith. Max also wrote compositions in tribute to unsung greats such as Big Sid Catlett and JC Moses.

Mr. Roach’s importance as a musician can be appraised by the diversity of drummers that he has influ-

enced: Stan Levey, Roy Haynes, Ed Blackwell, Joe Morello, Tony Williams, John Bonham, Steve Gadd,

and Terry Bozzio to name a few. All of these drummers drew a huge inspiration from the deep musical

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

12

well that is Max Roach. His influence is essential in the realm of modern drumming, and will be felt for-

ever. Max Roach was a musical innovator, a virtuoso, a master drummer, a bandleader, and a true pro-

fessor of the drums.

Joseph Rudolph “Philly Joe” Jones

(July 15, 1923 - August 30, 1985)

Philly Joe Jones was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and came from a prolific music scene that pro-

duced jazz greats like Benny Golson, Jimmy Heath, and John Coltrane. Jones’ nickname differentiated

him from the earlier “Papa” Jo Jones. He was influenced early on by lesser-known drummers on the

Philadelphia jazz scene like Butch Ballard, Dave Black, and Specs Wright. Philly Joe first recorded in

1947 with Joe Morris in a jazz-influenced Rhythm & Blues band that also featured saxophonist Johnny

Griffin. Early on, Philly Joe played many R&B style gigs; his shuffling backbeat on Joe Morris’ Anytime,

Anyplace, Anywhere documents Philly Joe playing in this style.

Philly Joe Jones firmly entered the jazz realm in 1953, with Tadd Dameron and Lou Donaldson. These

early recordings show a strong and swinging time feel, and prove Joe to be a solid accompanist. Jones

would eventually become a uniquely slick drummer, using precise stickings and flashy hand movements.

Ultimately, this slickness seeped into everything he played. He studied with Cozy Cole, who helped him

master the rudiments, and he also worked extensively out of the Charles Wilcoxon snare drum books.

Eventually he became influenced by Buddy Rich and incorporated a flashier and more drumistic ap-

proach to his playing. His complete assimilation of the rudimental approach became the most identifi-

able component of Philly Joe’s soloing vocabulary. He excelled at trading fours and eights, which can be

heard on the songs “Billy Boy,” “Two Bass Hit,” (both from the Miles Davis recording Milestones), “Ah

Leu Cha” (from Davis’ Round About Midnight) , and “Sippin At Bells” (from Sonny Clark’s Cool Strut-

tin’). As these recordings show, Philly Joe’s fours and eights were usually snare/rudiment based, and al-

ways stunning. For further listening, check out the amazing exchanges on “Temperance” from Wynton

Kelly’s Kelly At Midnight.

Philly Joe Jones participated in all of Miles Davis’ classic recordings from 1956: Workin,’ Cookin,’

Steamin,’ and Relaxin,’—all of which are loaded with jazz standards. It was Miles who, upon hearing

the now-common swing groove with a cross-stick accent on beat four, christened it the “Philly lick.” This

useful beat can be heard at its best during the piano solo on “All Of You” from Davis’ Round About Mid-

night, and “Miles” from Davis’ Milestones.

The brushwork of Philly Joe Jones is truly legendary. His predominant brush playing is featured

throughout Bud Powell’s Time Waits (especially on the song “Sub City”), and on Bill Evans’ trio record-

ing California Here I Come. In 1968 Premier Drums published his (currently out-of-print) brush book

entitled Brush Artistry.

Philly Joe’s timekeeping was multifaceted. It could be brash, audacious, and filled with attitude, as on “Be

Bop” from Sonny Clark’s Trio, “Dr. Jeckyl” from Milestones, “Moment’s Notice” from John Coltrane’s Blue

Train, and “Minority” from Everybody Digs Bill Evans. Or it could be very relaxed, as on “Bye Bye Black-

bird” from Round About Midnight, and “Surrey with the Fringe On Top” from Steamin.’

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

13

Although he didn’t record often with larger ensembles, he could certainly drive a big band. It has been

said that Buddy Rich would often hire Philly Joe to rehearse charts with his band. For this aspect of

Joe’s playing, listen to Tadd Dameron’s The Magic Touch, Philly Joe’s own Big Band Sounds Drums

Around The World, and Dameronia’s To Tadd With Love. Philly Joe was truly at home in any size band

or jazz context. For a unique example of his drumming, listen to Philly Joe and Sonny Rollins play a

duet on “Surrey With The Fringe On Top,” from Rollins’ Newk’s Time. This was possibly the only “duet”

of Jones’ career, and is a very telling look into his style and sound. Although Philly Joe was widely

recorded as a freelancer, his suggested recordings as a bandleader are Blues For Dracula, and Trail-

ways Express.

From 1955 through 1962, Philly Joe Jones was the most influential voice in jazz drumming. He was al-

ways at his best when playing with bassists Paul Chambers and Sam Jones. Late in his career he toured

a great deal with Bill Evans and Bobby Hutcherson, and was co-leader of the group Dameronia. Video

footage of Philly Joe is rare. Some footage exists of Philly Joe sitting in with Thelonious Monk in 1968,

but it is hard to find. On the Legends of Jazz Drumming DVD (Alfred Publishing Co.) there is a clip of

Philly Joe playing with pianist Bill Evans.

Philly Joe influenced nearly every jazz drummer that came after him, however, New York’s Kenny Wash-

ington, San Francisco’s Vince Laetano, and Rochester’s Vinnie Ruggiero are some of the most-influ-

enced “disciples” of the great master. Philly Joe Jones remains the quintessential 1950s small-group

jazz drummer, and was named as one of the 25 most influential drummers of all time by Modern Drum-

mer magazine.

Elvin Ray Jones

(September 9, 1927 – May 18, 2004)

Elvin Jones was more than a drummer, he was a musical spirit that humanized all of what the drums

truly represent. Elvin came from a musical family; he was the younger brother of jazz legends Hank and

Thad Jones. He came up through the ranks in the fertile Detroit jazz scene, which also produced in-

strumentalists such as Barry Harris, Kenny Burrell, Milt Jackson, and Ron Carter; and notable drum-

mers such as Louis Hayes, Oliver Jackson, and Roy Brooks. Elvin Jones was a supremely significant

drummer that absorbed some late swing influences from Shadow Wilson and Gene Krupa, and walked

through the door opened by Art Blakey. Elvin first recorded in 1948 with Thad Jones and Billy Mitchell.

Thankfully, these recordings are still available on a collection called Swing Not Spring, released by Savoy

records. It must be remembered that Elvin is important not only because of his work with the legendary

John Coltrane Quartet from 1960 to 1965. Elvin’s pre-and post-Coltrane work is also influential.

When Elvin moved to New York in 1955, he freelanced with J.J. Johnson, Tommy Flanagan, and Sonny

Rollins. The recordings with these leaders show a confident drummer with good time, firmly based in

the jazz tradition, whose ideas occasionally slipped across bar lines, and was imparting a slight legato

time feel to the other musicians. On the recordings by J.J. Johnson (Dial J.J. 5, 1957), Bennie Green

(Soul Stirrin’, 1958), and Harry “Sweets” Edison (Patented By Edison, 1957), we hear prime examples

of Elvin’s early sideman work. He never “upsets the apple cart,” is workman-like in his approach, and is

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

14

very swinging. With Sonny Rollins’ A Night At The Vanguard (1957), we hear Elvin progressing and be-

ginning to experiment. With Rollins, the ideas that would crystallize later with Coltrane are sporadi-

cally present, but are still somewhat unrefined. Rollins’ chordless trio created an unadulterated

environment for Elvin to experiment and stretch, and this essential recording is the result. We pick up

on Elvin’s progression in 1961 on Freddie Hubbard’s Ready For Freddie and Yusef Lateef’s Into Some-

thing, where we can hear some of the ideas from 1957 starting to really come together. Many of these

early recordings paired Elvin with bassist Wilbur Little, who was clearly unfazed by Elvin’s unique “ex-

pansion of time.” Later, bassists Ron Carter and Gene Perla filled this same role. Elvin was taking Art

Blakey’s polyrhythmic approach and expanding upon it. Elvin allowed the pulse to breathe, and his poly-

metric rhythmic vocabulary was truly multi-directional.

Elvin Jones could play louder than most other drummers, and when it was appropriate he created thun-

derous waves of rhythm. But he could also play softer than just about anyone. On pianist Tommy Flana-

gan’s Overseas (1957) we hear this side of Elvin’s playing. He could play softly and tenderly with brushes,

mallets, or sticks. This was never more evident than when Elvin played in a piano trio context. His trio

recordings with McCoy Tyner (Inception), Phineas Newborn (Harlem Blues), Tommy Flanagan

(Eclypso), Hank Jones (Upon Reflection), James Williams (Magical Trio 2), Stephen Scott (Aminah’s

Dream), John Hicks (Power Trio), and Robert Hurst (One For Namesake), balanced Elvin’s lighter

touch with the sheer power he was known for. Elvin was always tasteful and sensitive to the musical

landscape. Adam Nussbaum recalls seeing Elvin accompany jazz singer Maxine Sullivan at a jazz brunch,

and being knocked out by Elvin’s extreme sensitivity, “It wasn’t all slammin’ and bashin’,” recalls Nuss-

baum. As further proof of this important point check out Elvin’s playing on singer Johnny Hartman’s I

Just Dropped by to Say Hello, and with Gil Evans on Great Jazz Standards. While Evans’ recordings

were not big band dates, the large groups and intricate arrangements did require a different sensibility

from Elvin. Elvin’s stellar playing obviously impressed Gil, as he would later work with Evans on The In-

dividualism Of Gil Evans, and play percussion on Miles Davis’ collaborations with Evans, Sketches Of

Spain and Quiet Nights.

In my opinion, the most meaningful work of Elvin’s career (other than his playing with Coltrane) is his

work with organist Larry Young and guitarist Grant Green. Elvin’s drumming with Young (who would

later anchor the Tony Williams Lifetime) was firmly grounded in the tradition of B3 organ-style drum-

ming. His heavy quarter note pulse locked in with Young’s bass lines, and the sparse instrumentation

left room for Elvin’s ever-present 12/8 rhythmic underpinnings. Grant Green’s guitar kept the dynamic

of the group down; consequently the music doesn’t get as intense as the great Coltrane Quartet. This re-

straint makes these recordings somewhat more accessible, and a great place for drummers to start lis-

tening to Elvin. Other recordings include Grant Green’s Talkin About, Solid, and Street Of Dreams (all

recorded in 1964), and I Want To Hold Your Hand and Matador (both from 1965). Larry Young’s Into

Somethin’ added Sam Rivers to the trio of Young, Green, and Jones; and the highly influential Unity fea-

tured Joe Henderson and Woody Shaw with the dynamic rhythm section of Larry Young and Elvin

Jones. All these recordings are earthly and inviting, as opposed to Coltrane’s otherworldly quartet, which

lived somewhere in the rarified musical stratosphere.

It has been said to hear the influence of Elvin’s drumming, all you must do is to listen to any drummer

that came before Elvin, and then listen to any drummer that came after him. Some of the best examples

of drummers that evolved as direct descendents of Elvin Jones include Mitch Mitchell, Ginger Baker,

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

15

Adam Nussbaum, and Jeff “Tain” Watts. Similarly, it is also interesting to listen to Elvin’s drumming

before and after the Coltrane Quartet. Elvin joined Coltrane in 1960, replacing the unsung yet influen-

tial Pete LaRoca. In Elvin, John Coltrane found an improvisational partner who pushed his quartet (with

pianist McCoy Tyner and bassist Jimmy Garrison) to heights that will never be equaled. Elvin Jones’ lop-

ing time feel, polyrhythmic approach, boundless energy, and thunderous crescendos were part of the

quartet’s signature. But however aggressive and bombastic its peaks, the band could also take it down

to a whisper. This group was together for only five years, but in that time they made a wide array of

recordings. Elvin is heard at his all-embracing best on Crescent and A Love Supreme, and his most sub-

lime on Ballads, John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, and John Coltrane and Duke Ellington. There

are many live Coltrane recordings, but the Live At The Vanguard series (1961), Afro Blue Impressions

(1963), and One Up, One Down: Live At The Half Note (1965) are definitive documents of this hard-

working band. They made many studio recordings and all of them are remarkable, but Ascension and

Transition both offer the quartet at its aggressive peak. My Favorite Things and Africa/Brass provide

slightly mellower offerings. A fantastic example of Elvin’s spot-on timekeeping can be heard on 1960’s

Coltrane’s Sound. This band is also captured on Coltrane’s Jazz Icon and Jazz Casual DVDs.

Elvin made legendary recordings with other bandleaders as well. Wayne Shorter’s Speak No Evil, Joe

Henderson’s Inner Urge, and McCoy Tyner’s The Real McCoy are perhaps the most treasured examples.

But Shorter’s Juju and Night Dreamer along with Henderson’s In n’ Out can’t be forgotten. It is no co-

incidence that Elvin was present for many classic recordings. What he brought to a recording session (or

the bandstand) could not be measured by the notes alone. Elvin Jones had a spiritual presence that was

palpable to the musicians around him. His capability of producing waves of pulse and free expression-

ism on the drums emanated from his tenure with Coltrane. Two recordings with Ornette Coleman, Love

Call and New York Is Now, show this side of Elvin. And he would continue this approach throughout

his life: Check out the 1999 recording Momentum Space with avant-garde masters Dewey Redman and

Cecil Taylor. But to appreciate his emotional range, listen to the 1964 recording Stan Getz & Bill Evans

to hear a more restrained side of Elvin.

The seemingly endless waves of pulse, often combined with a gentle overture, made Elvin’s own albums

unique. And these recordings often spotlighted future stars of jazz. The Ultimate Elvin Jones and Puttin’

It Together featured saxophonist Joe Farrell. Live At The Lighthouse featured Dave Liebman, and On

The Mountain featured Jan Hammer. Elvin’s influence went far beyond jazz. Guitarist Carlos Santana

calls Elvin’s 1969 recording Poly-Currents (with conguero Candido Camero) one of his “absolute fa-

vorites.” Musicians from every style have been struck by the thunder and lightning that is Elvin Jones.

Some of his more uncelebrated work includes his drumming in the ’60s psychedelic western movie

Zachariah, his recording with the group Oregon, Together, and with television soundtrack composer

Raymond Scott’s Secret 7 on The Unexpected. And however unique these situations were, Elvin always

brought a childlike sense of musical adventure to the proceedings.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s many of today’s jazz greats called upon Elvin to bring his magical

spirit to their recordings. John McLaughlin formed an organ trio that featured Elvin, and the subse-

quent recording After The Rain is a modern classic. Kenny Garrett went head-to-head with Elvin on

African Exchange Student, and Wynton Marsalis benefited from Jones’ pulse on Thick In The South.

Elvin would continue to lead his Jazz Machine band and introduce future stars to the jazz world until

his death. Their Jazz Machine video (View Video), and Elvin’s Different Drummer (Alfred Publishing

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

16

Co.) video provide visual proof of Elvin’s inimitable style. Elvin Jones’ welcoming, larger-than-life spirit

remains with anyone who ever met him, and drummers continue to walk through the artistic doors

which he opened. He is one of the most influential drummers of all time.

Joseph “Dukes” Thomas

(August 21, 1937 - December 1992)

There is no doubt that Joe Dukes is the least known drummer mentioned in this package. But don’t let

your lack of familiarity cause your interest to waver. Music history is filled with influential drummers

who have not received their just due—but the jazz drumming continuum stands upon their shoulders

nonetheless. As an introduction to this forgotten great, let’s set the scene with some historical context

and musical background. To understand Joe Dukes, we need to take a look back at the beginnings of the

Hammond B3 organ trios.

In 1950, “Wild” Bill Davis was one of the first keyboard players to take the Hammond B3 organ outside

of its usual home, the church. Davis popularized the combination of jazz and R&B with a “big band” ap-

proach, and applied it to a trio setting: organ, drums and guitar. In 1951, Bill Doggett started an organ

trio and followed in Wild Bill’s footsteps. By the mid ’50s, Philadelphian Jimmy Smith started drawing

darker and more percussive sounds from the organ. He added some bebop and greasy blues to the B3

vocabulary, and the organ’s popularity grew in leaps and bounds.

In support of this new style of jazz, a circuit of “organ clubs” soon established itself throughout the

United States. These clubs all had Hammond B3 organs permanently installed in their establishments

to accommodate the many popular touring organ groups. These bands performed with a bluesy, highly

accessible, and inviting approach that music lovers across the country found quite appealing. This is the

environment in which Joe Dukes established himself as a drummer. There were many bands that were

based around the sound of the Hammond B3, but the organ drummers were a breed unto themselves.

There were dozens of organists making a living on the chitlin’ circuit (as it was called) including “Wild”

Bill Davis, Jimmy Smith, Groove Holmes, Jimmy McGriff, Brother Jack McDuff, Dr. Lonnie Smith,

Reuben Wilson, “Big” John Patton, Don Patterson, Johnny “Hammond” Smith, Gene Ludwig, and

Charles Earland. These groups are a tradition within the jazz tradition.

This exciting scene gave early exposure to many legendary musicians such as George Benson, Pat Mar-

tino, Grover Washington Jr., and Joe Lovano. And many celebrated drummers including Bernard Pur-

die, Billy Hart, and Mike Clark cut their teeth playing in organ bands that included equal doses of groove

and swing. There were a handful of drummers that became known almost exclusively for their style of

organ drumming, including Chris Columbo, Eddie Gladden, Ben Dixon, Jimmy Lovelace and Joe Dukes.

Drumming giants Tony Williams and Steve Gadd have mentioned the importance of seeing the early

organ groups and experiencing the drummers’ infectious sense of groove. This influence was so strongly

felt that Williams’ first band, the Tony Williams Lifetime, was an organ trio, and Steve Gadd’s band The

Gadd Gang (although it didn’t have an organ player) had the honky-tonk vibe of an organ group.

Many of drumming history’s established greats (including Elvin Jones, Harvey Mason, and Dennis

Chambers) have benefited greatly from their experience playing with organ groups. There are still many

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

17

fantastic organists keeping this tradition alive, including Joey DeFrancesco, Larry Goldings, John

Medeski, Hank Marr, Tony Monaco, and Mike LeDonne. And there are many drummers who continue

to bring the organ groove to every note that they play. These drummers include Donald Bailey, Grady

Tate, Idris Muhammad, Alvin Queen, Bill Stewart, Byron Landham, and Cecil Brooks III.

This all brings us to the great Joe Dukes. Joe Dukes was born Joseph Thomas on August 21, 1937 in

Memphis, Tennessee. He died in December of 1992 in New York City. He is one of the most important

drummers to emerge from the organ-drumming tradition. Joe hit the music scene as a part of the

Brother Jack McDuff group in 1961. He stayed with McDuff for six years and played on numerous record-

ings. The McDuff group (which included George Benson) was often augmented by guest soloists, big

bands, and singers on their recordings. They even had a hit record called “Rock Candy.”

Joe Dukes’ style of swing had an unrelenting energy that recalls early Art Blakey and a sense of melod-

icism and virtuosity that recalled Max Roach. Dukes brought these influences to the organ-drumming

tradition. Up until that point, the organ-drumming style was rather unrefined. It relied on greasy swing

and supportive groove as opposed to solos, independence, and polyrhythmic patterns. Although many

of the early organ drummers didn’t have the technique that the bebop drummers had, they had all the

feel one could want in a musician. They were drummers who related more to the earlier swing-drum-

ming tradition than to later bebop drumming styles. The organ drummers could keep people dancing

and clapping well into the night; this was a staple of the chitlin’ circuit. To quote a phrase, “they swung

you into bad health!” Like the swing big bands of Benny Moten or Jimmy Lunceford, the organ bands

played good-time party music.

Joe Dukes always kept this “feeling” in his drumming, but he also added a sense of virtuosity. He fused

the organ style of swing-influenced drumming, the modern style of small-group bebop drumming, and

later added a sense of funkiness that was unmatched. He was also a fantastic showman! You can hear

Joe Dukes’ swinging brand of traditional organ-style drumming on Brother Jack Meets The Boss, where

Gene Ammons guests with McDuff’s band. On Brother Jack McDuff’s Screamin’ we hear an explosive

Joe Dukes on the bluesy “After Hours” and the swing staple “One O’Clock Jump.” Joe stretches out and

solos at length over a Latin vamp on the title track. Also appearing on this album is the original version

of Dukes’ melodic drumming feature, “Soulful Drums.” This showcase places Joe Dukes in the line of

truly melodic drummers that began with Big Sid Catlett, continued with Max Roach and Sam Woodyard,

and continues today with Terry Bozzio and Ari Hoenig. Dukes rerecorded this tune on his own The

Soulful Drums Of Joe Dukes (reissued on CD under Jack McDuff’s name) with an even more aggressive

approach. “Soulful Drums” has since been covered by Idris Muhammad and Steve Smith and remains

as one of the most unique drum features ever recorded.

The collection Jack McDuff: Legends of Acid Jazz features a great dose of Joe Dukes. The breakneck

tempo of Ray Charles’ “I Got A Woman” is breathtaking. The band is preaching while being catapulted

by Joe’s groove on “Hallelujah Time,” “From The Bottom Up,” and “Scufflin.” Dukes’ tighter time feel

on “Au Privave” shows that he was very capable of fitting into the more traditional role of a bebop drum-

mer. The McDuff recording Crash (featuring guitarist Kenny Burrell) is a more relaxed and swinging

example of McDuff, Dukes, and company.

To get a feel for what the chitlin’ circuit was all about, check out Jack McDuff’s Live. This is an out-

standing recording of two shows that McDuff’s group played in 1963, and includes an inspired reading

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

18

of the group’s hit “Rock Candy,” among other swingin’ and soulful good-time jazz. You can almost smell

the chicken frying and the greens simmering.

However, to stop paying attention to Joe Dukes’ drumming after the famous McDuff group would be a

mistake. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, Dukes joined forces with another of the great organists, Dr. Lon-

nie Smith. Smith had played with George Benson’s popular working band (with superb organ drummer

Marion Booker), and eventually went out on his own. Joe Dukes soon signed on. Dr. Lonnie Smith’s

group was one of the busiest organ groups in the 1970s and often included baritone saxophonist Ron-

nie Cuber, whom some drummers might recognize from his work with Steve Gadd’s Gadd Gang. Dr.

Lonnie Smith (like many other leaders of the time) often included funky versions of popular tunes in his

sets. On his recordings Drive and the essential Live At The Club Mozambique, Smith’s band played Sly

Stone’s “I Want To Thank You,” and Blood Sweat and Tears’ “Spinning Wheel.” In the hands of Joe

Dukes, these grooves percolate with excitement and a sense of funk more often associated with James

Brown’s bands. Witness the selection “I Can’t Stand It” for confirmation of this claim. Joe’s drum breaks

and infectious beats on “Spinning Wheel” could easily be mistaken for funk masters Modeliste or

Garibaldi. Yes, Joe Dukes was that funky! His funk playing has that unique sense of swing that could

only come from a jazz background, and his lighter touch keeps the syncopated conversation of his left-

hand comping smooth, exciting, and propulsive.

Check out Joe’s version of a classic fusion groove on the intro of “Twenty Five Miles.” Note the similar-

ities between this groove and the one that Tony Williams plays on “It’s About That Time” (released only

four months earlier on Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way). Joe’s exciting drive on “Seven Steps to Heaven”

also recalls Tony Williams; however, the swinging quarter-note groove that Dukes lays down on the end

vamp is organ drumming at its best! Both of these examples show a distinct Tony Williams-esque ap-

proach, reminding us that while Tony was influenced early on by the organ drummers, that influence was

eventually reciprocated. Joe’s brisk time-feel almost channels Art Blakey on the tune “Expressions,”

while his comping leans closer to Philly Joe Jones, and his all too brief solo shows a sense of virtuosity

that is truly Dennis Chambers-ish. The “stupid funky” grooves on “Scream” and “Play It Back” reminds

us that Joe’s early Memphis roots were never too far from the surface. I must also mention that all of this

authentic funk and jazz drumming is happening on the same set of drums and cymbals, dispelling the

modern myth of a separate “jazz drum sound” and “funk drum sound.” Joe Dukes’ drum sound on Live

at the Club Mozambique destroys this fallacy by letting us hear some serious swing, and treacherous

groove from the same drums and cymbals, not to mention the same drummer!

The tradition of the organ-led groups in jazz is very important, but it would have been lost without the

influence of the drummers. Joe Dukes is one of the most important players from that tradition, and his

inclusion in this set is monumental. It is rumored that none other than Frank Zappa recognized Joe

Dukes’ unique sense of groove: He is rumored to have sought Joe to occupy the drum chair in his band.

Although I have never been able to confirm this, Chester Thompson (who followed Dukes into Jack Mc-

Duff’s band before joining Zappa himself) told me that in his opinion this would have made sense, and

that Dukes was Zappa’s type of drummer. Dukes assimilated a unique blend of characteristics into his

playing that I have never heard from another drummer: excitement, melodicism, drive, funk, and swing.

Joe Dukes created a supremely soulful and unique voice on the drum set. And after all, isn’t that what

it’s all about?

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

19

Anthony Tillmon “Tony” Williams

(December 12, 1945 - February 23,1997)

Tony Williams has been lauded by nearly everyone who has ever picked up a drumstick, and rightfully

so. He has inspired us all! His virtuosity is unmatched, and creativity runs rampant throughout his ca-

reer of groundbreaking music and breathtaking drumming. He walked through the door that Roy

Haynes, Art Blakey, and Elvin Jones opened for highly interactive, aggressive, and elasticized modern

drumming. His work with the Miles Davis Quintet set the standard for creative mid-’60s jazz drumming.

His sideman recordings on Blue Note with Jackie McLean, Kenny Dorham, Grachan Moncur III, Andrew

Hill, and Herbie Hancock cemented his importance in a new style of music that introduced an avant-

garde sense of freedom into a more straight-ahead setting. This was later referred to as “free bop.” As a

bandleader, Tony led many different ensembles. His first recordings, Life Time and Spring, expanded

the sense of freedom that Tony took to his work with Miles. Later, this sense of freedom was integral to

his early Lifetime trio with Larry Young and John McLaughlin—the band that defined the concept of jazz-

rock or fusion. His mid-’70s band, The New Tony Williams Lifetime (with Allan Holdsworth, Tony New-

ton, and Alan Pasqua) created the treatise for many later approaches in jazz-rock with their recording

Believe It. With his final quintet, Tony explored his compositional and arranging skills with six stellar

recordings of his own compositions that framed his consistent, explosive, and supportive drumming. In

between all of his work as a bandleader, there were many special recordings that benefited greatly from

Tony’s presence. It is no coincidence that Tony played on so many classic recordings; his inclusion on a

recording date raised the musical bar.

For this package, Tony Williams has an even more special meaning. Tony is the perfect example of a

modern drummer who was standing on the shoulders of those who came before him. He assimilated the

approaches of his favorite drummers and added to them, advancing the artform of jazz drumming while

inspiring others to do the same. At the time of his death he was even working on a project that exam-

ined the evolution of jazz drumming. Tony’s greatness is well documented on his many recordings. But

what is often overlooked is that because these recordings began at an early age, they afford us the chance

to study the development of an exceptional artist. Today, not only can we examine his recordings, we

can examine how his peers on the jazz drumming scene influenced him in his formative years. It’s time

that we go back a little further and examine the roots and influences of this innovative drummer and see

what shaped the musical mind of this one-of-a-kind artist.

As a boy, Tony was very aware of the tradition of jazz drumming. His father was an active saxophonist

on the Boston jazz scene, which was the home of forward-thinking musicians like Herb Pomeroy, Jaki

Byard, and Sam Rivers. We can gain insight into what this environment must have been like by listen-

ing to Tony on Sam Rivers’ Fuschia Swing Song. Through his father and his early teacher Alan Dawson,

Tony was getting experience playing jazz with many older Boston musicians. He was learning on the

bandstand in a “trial by fire” environment. While he was studying with Dawson, there is no doubt that

a sense of fearless musical exploration was emerging in Tony. But this interest in musical exploration

was not only confined to jazz. Like many teens in the 1960s, Tony was also enamored with rock’n’roll.

He cited groups like The Beatles and The MC5 among his favorites.

The teenage years are an impressionable and rebellious time in anyone’s life, and the teenager thinks

there is nothing he cannot do. There is a good dose of this youthful bliss and creative innocence in Tony’s

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

20

early, super-confident drumming approach. Because of his audacious technical abilities, it is easy to for-

get that when Tony began playing with Miles Davis he was only a teenager. However, in retrospect this

may be one of the reasons that he could be so daring. Think about the confidence that must have come

from playing with an icon like Miles Davis, starting in 1963 at the age of 17. Combine this with the fact

that that the 1960s were a time of change, rebellion, and cultural upheaval. With Miles Davis, Tony had

fallen in with a man some considered to be the ultimate rebel. To properly study Tony Williams, we

must understand his upbringing, with this myriad of personal, cultural and musical influences. To re-

ally appreciate and fully understand Tony’s uniqueness we should look at the drumming influences that

were present “on the scene” (both locally and nationally), and how they manifested themselves in Tony’s

drumming. This creates a cultural perspective to contextualize Tony’s groundbreaking drumming and

extraordinary musical approach.

When Tony’s father used to take him to Boston nightclubs to hear live jazz, many of the groups that he

heard were the then-popular organ groups. Tony would later comment that those groups had a strong in-

fluence on him. Possibly this is one of the reasons why his first Lifetime band was an organ trio. The

Boston jazz scene was very active, and Tony most likely would have heard drummers Bill “Baggy” Grant,

Clarence Johnson, Larry Winters (all of whom were very close with Alan Dawson), and Jimmy Zitano. Zi-

tano was good enough to have played with Miles in Boston in 1955, and later recorded with Donald Byrd.

Bill “Baggy” Grant was one of the “godfathers” of bebop drumming. He played and recorded with Char-

lie Parker, Gigi Gryce, and Boston pianist Jimmy Martin. Clarence Johnson was a supremely-swinging

drummer who recorded with Freddie Roach, James Moody, Ben Webster, and Harry “Sweets” Edison.

In a 1985 drum clinic, Tony talked about the ingredients that he felt would make a perfect drummer:

technique, feel, and creativity. He began by citing Boston drummers with these attributes, mentioning

Dawson’s technical abilities and Baggy’s feel. Unfortunately he couldn’t recall the name of his Boston-

area example for creativity, but I have no doubt that it is one of the drummers named above, seen by

Tony in his formative years. He then proceeded to recall the big-name drummers that had those quali-

ties: Max Roach (technique), Art Blakey (feel), and Philly Joe Jones (creativity). Tony made no secret of

the fact that as he developed, he went through periods where he consciously tried to sound like his major

influences: Max Roach, Art Blakey, Roy Haynes, and Philly Joe Jones. But in addition to these giants,

Tony also mentioned lesser-known influences like Jimmy Cobb, Louis Hayes, and Clifford Jarvis. While

a great deal of examination has been done on the big-name drummers, the lesser-known players have

been largely ignored. Let’s take a look at a few of Tony’s lesser-known influences.

By the time Tony first recorded in 1963 with Jackie McLean (Vertigo, One Step Beyond), Herbie Han-

cock (My Point Of View), and Kenny Dorham (Una Mas), his drumming was ripe with influences from

his jazz-drumming peers. These drummers set the standard with the same bandleaders whom Tony

would soon be working with. For example, Tony’s straight-eighth-note “boogaloo” playing and loose

swing was very similar to that of the popular Billy Higgins. Tony’s ride cymbal playing had assimilated

bits of Art Taylor, Jimmy Cobb, Shelly Manne and Louis Hayes. His looser, more out-of-time playing had

its origins with Pete LaRoca and later showed evidence of Sunny Murray and Rashied Ali. Herbie Han-

cock told me that “Tony’s sense of exploration and fire was inspired by his boyhood friend, drummer Clif-

ford Jarvis.”

Billy Higgins’ influence on Tony can be heard when you listen to Billy’s playing on Donald Byrd’s 1961

recording Free Form, Jackie McLean’s Let Freedom Ring, Herbie Hancock’s Takin’ Off, and Dexter Gor-

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

21

don’s Go! (all recorded in 1962). Compare these recordings to Tony’s early 1963 recordings as a sideman

on Blue Note. Higgins had become known for his swinging and joyful time feel. He combined his time-

keeping with a sense of freedom that came from his experience with Ornette Coleman. Together this

created a unique looseness within Billy’s effervescent time flow. All the while, Higgins’ comping style kept

a more traditional bebop approach. But the similarities between Billy and Tony didn’t stop there. Hig-

gins created a signature “boogaloo beat” that was very straightforward and direct, as heard on Han-

cock’s “Watermelon Man” and Lee Morgan’s “The Sidewinder.” This groove became immensely popular

and most drummers were influenced by it. But Tony’s interpretation loosened up the eighth notes, ac-

centuated the bass drum, and widened the beat slightly. This resulted in more of a rock feel (listen to

“Eighty One” on Miles Smiles and “Stuff” on Miles in the Sky), as opposed to Billy’s sanctified R&B

boogaloo. This makes sense because Tony was from one of the earliest rock-influenced generations. Billy

Higgins’ voice in drumming was a combination of a loose time feel, a traditional comping style, and a

signature groove. Thus, the young Tony Williams sounded similar to the already established Billy Hig-

gins both in style and approach.

When Miles Davis was putting together a new band in the early ’60s, he considered other drummers

before hiring Tony Williams. He recorded with Frank Butler and New Yorker Willie Bobo (who was re-

portedly offered the gig before Tony). But it was Tony who ultimately got the call. Tony was replacing

Jimmy Cobb, who in turn had replaced Philly Joe. Musically, the new band was entirely different in con-

ception and direction, yet Cobb had laid some of the groundwork for Tony. Upon listening to Jimmy’s

drumming on Miles’ 1961 Live At The Blackhawk recordings, you are introduced to Cobb’s instantly

identifiable ride cymbal approach. This approach was created by Jimmy’s unique sense of “rhythmic

skipping” and breaking up the beat (often attributed to more modern players), combined with his sig-

nature swinging-quarter-note style. This was a major, yet usually overlooked, influence on Tony’s early

timekeeping.

Tony’s ride cymbal playing flattened out at higher tempos. The origin of this approach is usually iden-

tified with Max Roach. But Max’s strong influence on Tony was found more in his melodicism, musi-

cality, and orchestration. For uptempo timekeeping, give a listen to Shelly Manne breaking up the ride

on “Love For Sale” from Shelly Manne and His Men at The Manne Hole Vol. 1, or Louis Hayes’ brisk

swing on Kenny Drew’s Undercurrent and Freddie Redd’s Shades of Redd. When asked, Tony would

often recall the influence of Louis Hayes.

Art Taylor’s timekeeping was a favorite among musicians in the late ’50s and early ’60s. Both Jackie

McLean and Kenny Dorham worked with Taylor in the years preceding their work with Tony. “A.T.” (as

he was called) had a professional and unobtrusive drumming approach, but it was his comfortable and

slightly pushing time feel that musicians liked. Listen to the slight push of his time feel on McLean’s

Swing, Swang, Swingin,’ and Kenny Dorham’s Inta Somethin’, and compare it to Tony’s. We can even

compare their takes on the tune “Una Mas,” which they both recorded with Dorham.

In 1959, Pete LaRoca recorded the first free-form drum solo on a tune that was otherwise played in time.

“Minor Apprehension” from Jackie McLean’s New Soil was highly influential. Suddenly drummers could

solo off of an internal “pulse,” free of the restraints of keeping strict time for themselves within their

solos. LaRoca was an important drummer; he played in John Coltrane’s first band (that went un-

recorded), and recorded and toured with Sonny Rollins’ trio. At the time, Pete was also playing with

Steve Smith

Drum Legacy

22