Human Mosaic

A Journal of the Social Sciences

Volume 34

2003

Numbers 1–2

Human Mosaic

A Journal of the Social Sciences

Volume 34

2003

Numbers 1–2

Articles

Bloodletting and Vision Quest Among the Classic Maya.

A Medical and Iconographic Reevaluation

Sven Gronemeyer .........................................................................................................................................5

X-Ray Toads and “e Enema Pot.” A Maya Vase in the San Antonio Museum of Art

Michael McBride.......................................................................................................................................15

Knowing When to Clear the Fields: Manacus vitellinus

and Swidden Farming in Northern Coclé, Panamá

Nina Müller-Schwarze...............................................................................................................................25

Human Cranial Plasticity. e Current Re-evaluation of Franz Boas’s Immigrant Study

Markus Eberl.............................................................................................................................................31

Violent Cures for Violence: Bad Medicine, Silent Politics, Evacuation and Transit

Rebecca Golden..........................................................................................................................................39

Book Reviews

Jeff Benedict. No Bone Unturned: e Adventures of a Top Smithsonian Forensic Scientist

and the Legal Battle for America’s Oldest Skeletons.

Reviewed by Kerriann Marden ..................................................................................................................48

Karl G. Heider. Seeing Anthropology: Cultural Anthropology through Film.

Reviewed by Nina Müller-Schwarze............................................................................................................49

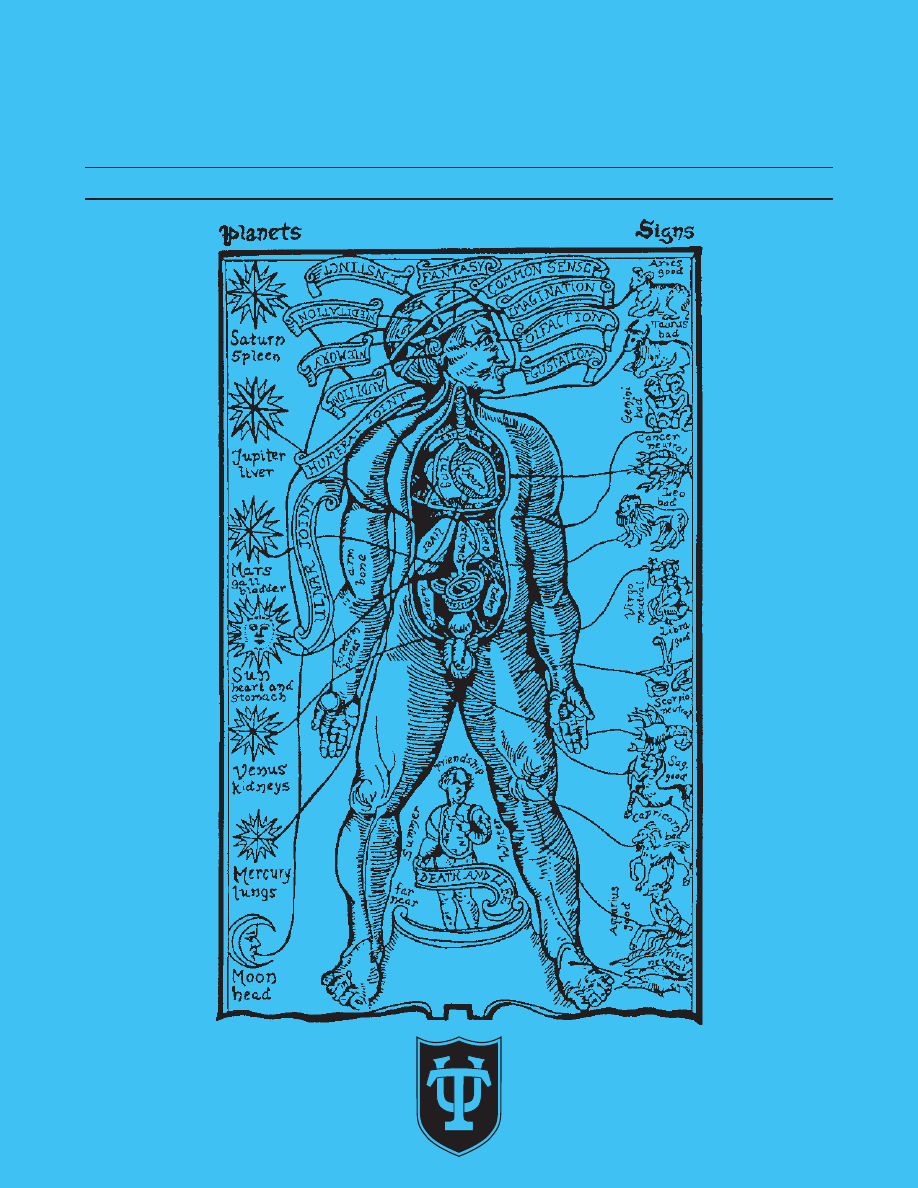

Cover:

Parts of the human body ruled by planets and constellations. Redrawn, with English captions, by Marianna A. Kunow on

page 26 in Victoria R. Bricker and Helga-Maria Miram (2002) An Encounter of Two Worlds: e Book of Chilam Balam of Kaua.

(Middle American Research Institute Publication 68) New Orleans: Tulane University. Courtesy of the Middle American Research

Institute.

5

Impressum

Human Mosaic (ISSN 0018-7240) is published semi-annually by the graduate students of the Social Sciences at Tulane

University. It has served since 1966 as a forum for the presentation of ideas of interest to the Social Sciences. Subscrip-

tion is $18.00 per year.

Checks or purchase orders should be made payable to Human Mosaic. Back issues, except Volume 1, Number 1, are

available at $9.00 per copy. Volume 1, Number 1 is available by special arrangement for $15.00 per copy.

Human Mosaic website: http://www.tulane.edu/%7Eanthro/other/humos/humos.htm

Managing Editor:

Markus Eberl

Acting Editors:

Jim Dugan

Vance Hutchinson

Timothy Knowlton

Book Review Editor:

Sara Phillips

All comunication should be directed to:

Human Mosaic

c/o Department of Anthropology

Tulane University

New Orleans LA 70118

Information for authors

e editors welcome articles from both students and faculty in the Social Sciences and related fields, about topics

pertaining to the Social Sciences. Manuscripts should be submitted in duplicate with formatting in American Anthro-

pologist style (the style guide is available at http://www.aaanet.org/pubs/style_guide.htm). We strongly urge authors to

submit manuscripts on a 31⁄2” IBM compatible diskette or a - in Rich Text Format. Bibliographic information

should be unformatted in plain text. Illustrations are limited to line drawings in ink and black-and-white photographs

(halftone, high contrast) with a maximum size of 61⁄2 × 71⁄2 inches. Illustration may also be submitted in a scanned

format, in consultation with the Human Mosaic editors. e editors reserve the right to make minor editorial changes

without notice. Unpublished manuscripts will be returned only if accompanied by a stamped, selfaddressed return

envelope. ose accepted for publication will not be returned, but the author will receive two copies of the issue in

which her/his article appears.

5

Introduction

is article (1) deals with the medical and organic bases

of bloodletting among the Classic Maya. It is interested

specifically with the question of whether it was possible to

produce visions by harvesting blood from the human body,

a hypothesis first presented by Peter Furst (1979) and later

by Linda Schele and Mary Miller (Schele and Miller 1986:

177).

A tabulation of different methods of drawing blood from

the human body will be accompanied by a short anatomic

survey. A consideration of the causes and mechanisms of al-

tered states of consciousness allows assessing whether blood

sacrifice can create trances. e latter considerations are

based on interviews with physicians specializing in neurol-

ogy and psychiatry, who practice at the county hospital in

Lüdenscheid, Germany. It appears that bloodletting alone

is not able to produce visions, but rather that psychological

and pharmacological stimulants contribute to it.

At this point a remark about the methods is appropri-

ate: while the medical aspects presented here are based on

clinical studies, a comparable experimental approach is

impossible in the case of the ancient Maya. We have only

fragmentary information about many aspects of the Classic

Maya. It is, however, possible in some cases to supplement

information that is missing for the Classic period (A.D. 250

to 950) from Colonial sources (after A.D. 1540). I have

done so in the following to provide a fuller picture. Yet, I

am aware that Colonial and Classic sources are separated

by several hundred years and that the Colonial sources may

not accurately reflect Classic period customs.

Previous research

e fact that the Maya of the Classic period made offerings

of their own blood has been known for a long time on the

basis of numerous iconographic and epigraphic analyses

(among others Proskouriakoff 1973, Joralemon 1974,

Baudez 1980, Stuart 1984 and Winters 1986). In these

previous works, a very detailed iconographic system was

recognized of how the various aspects of the blood sacrifice

were displayed and the ritual action was depicted together

in writing and pictorial representations.

Yet, few works dealt with the techniques of sacrifice as

well as with the ritual aspects from a medical perspective.

Peter Furst attempted in 1974 to provide a connection

between bloodletting, pain and vision. Robicsek and Hales

(1989) did a surgical evaluation of heart sacrifice. Kremer

and Flores (1993) analyzed the so-called “ritual self-de-

capitation”. I will focus on the hypotheses of Furst and

of Schele and Miller about inducing visions by harvesting

Human Mosaic 34(1–2), 2003, pages ##–##

Bloodletting and Vision quest among the Classic Maya

A medical and iconographic reevaluation

Sven Gronemeyer

Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität

Bonn, Germany

Keywords: Maya, bloodletting, ##

(1) e present article summarizes the results of a paper originally writ-

ten during summer 1999 and presented during summer term 2000 in

Nikolai Grube’s advanced seminar “Recent approaches in the explora-

tion of Classic Maya religion” at the Institut für Altamerikanistik und

Ethnologie at the University of Bonn.

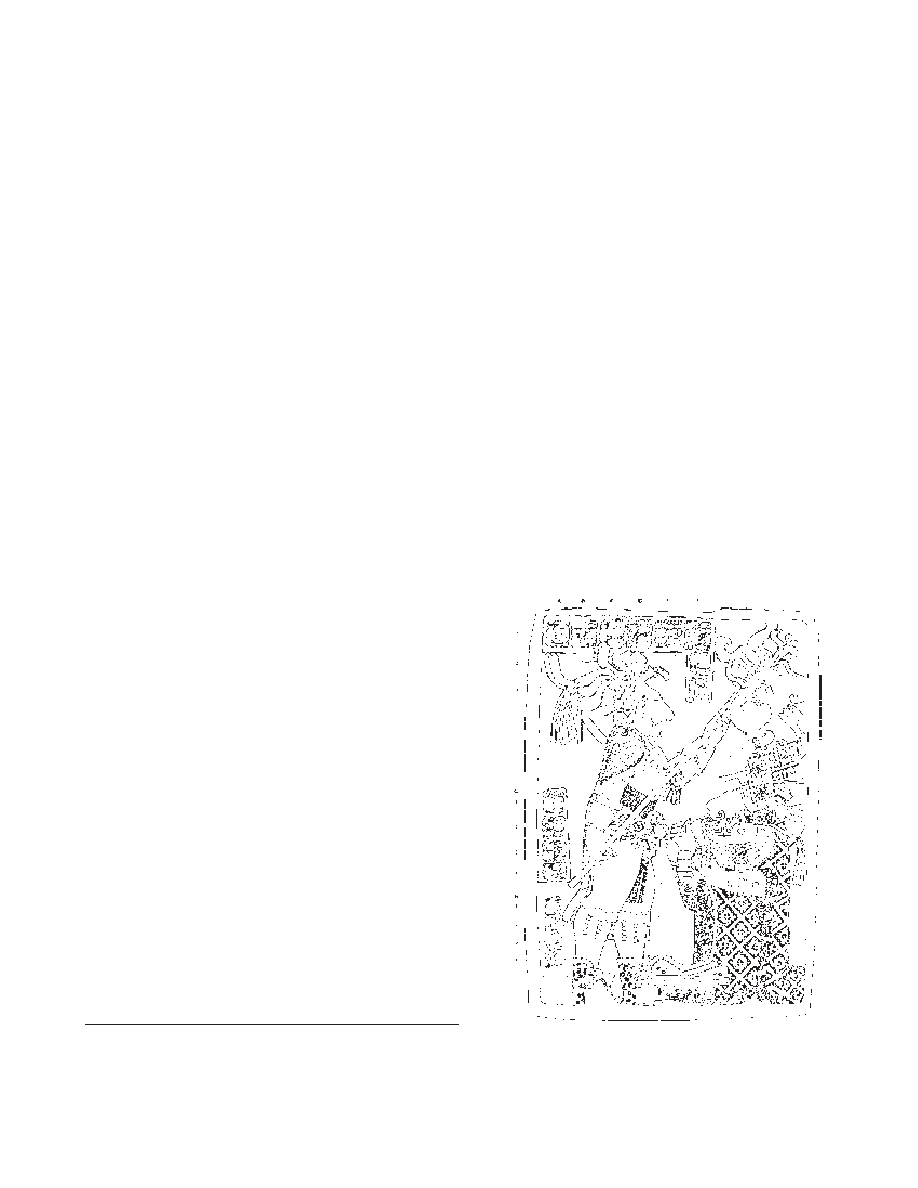

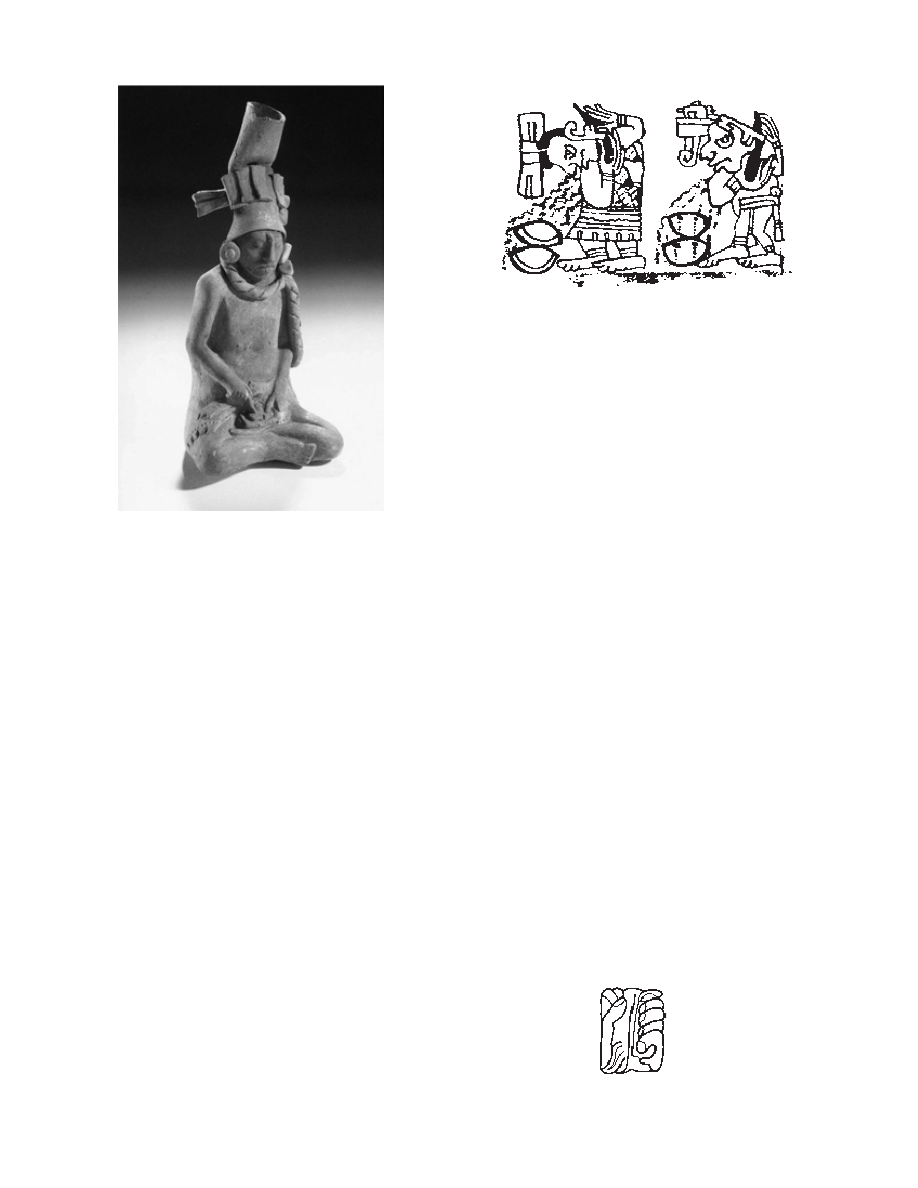

Figure 1a. Lady Xook lets blood by pulling a thorn-lined rope

through the mutilated tongue. Note the bowl that catches the

rope on a staple of blood-spotted paper. Yaxchilan Lintel 24.

Drawing: Ian Graham. In: Graham 1977: 3-53.

6

Human Mosaic

Volume 34, Numbers 1–2

7

blood from the human body, since it is the best known

and most accepted. A more comprehensive discussion of it

will follow in the main part of this paper together with the

critique.

Bloodletting in Maya art and writing

e act of bloodletting can be demonstrated by icono-

graphic and epigraphic evidence. Carolyn Tate (1992: 88)

gives a list of iconographic elements that allow the identi-

fication of this theme. Among them are a set of bloodlet-

ting equipment, consisting of a bowl with lancets, stingray

spines, cord, and bark paper. Representations of this equip-

ment are embedded together in explicit scenes of this act,

as on Yaxchilan Lintel 24 (Figure 1a). A special costume

is also of importance in the art of Yaxchilan, with women

wearing a Mexican year-sign headdress. e explicit scenes

at Yaxchilan allowed Tatiana Proskouriakoff (1973) to

identify several hieroglyphs that occur in the written con-

text of bloodletting and vision scenes, the verb T714 (see

below) and the sign T712, proposed to be the hieroglyphic

representation of an obsidian lancet (Proskouriakoff 1973:

172). e appearance of visions is connected with the rep-

resentation of a bent centipede body (it is also called “vision

serpent,” Boot 2000: 193) from whose maw an anthropo-

morphic figure frequently emerges (Figure 10).

Linda Schele and Mary Miller (1986: 179) recognized

that no direct (epigraphic) relationship exists between

blood sacrifice and the rise of a vision. ey suspected

it on the basis of the clustering of certain iconographic

motifs. Tatiana Proskouriakoff (1973: 169) was the first

to recognize that the hieroglyph T714 (Figure 2) which

is now read as /TZAK/ (Grube 1991: 86) always occurs

in the inscriptions, when the appearance of visions in the

form of a bent centipede is depicted in the accompanying

iconography. e Diccionario Cordemex (Barrera Vasquez

1980: 850) paraphrases tzak with conjurar nublados and

conjurar temporales. As Diane Winters (1986: 235) has ob-

served, T714 never occurs with scenes of bloodletting. On

the other hand, only iconographic indications of the blood

sacrifice occur with the appearance of visions. e problem

is embedded in the semantic dimension of the word tzak,

which describes a cultural concept familiar to the ancient

Maya, but whose exact, emic notion is lost to us, though

we can approximate its meaning. For this reason it was

not necessary to describe the events more closely in the

inscriptions, the scenes depicted show rather “key motifs”

of the whole rite. Consider the following example: the term

“celebrating high mass”, its contents and their sequence are

understandable for a person familiar with Christian liturgy

and need no further comment, whereas a person with a dif-

ferent cultural background may not understand it. e text

(Table 1) of Lintel 25 of Yaxchilán (Figure 10) exemplifies

how the ancient Maya described this ritual:

Figure 1b. Bloodletting with a chisel perforating a part of the

penis, ceramic figurine. Note the small slab on which the penis

is placed as it was described by Francisco Ximénez. Photo: Justin

Kerr. In: Schele and Miller 1986: 203.

Figure 1c. Withdrawal of blood from the ear lobe by piercing with

a flint or obsidian lancet. Note the zigzag lines coming from the

bodies. ey are originally painted in red and represent streams

of blood. Codex Madrid, p. 95a. Drawing: Sven Gronemeyer.

Figure 2. e sign T714 /TZAK/. Drawing: Sven Gronemeyer.

6

Human Mosaic

Volume 34, Numbers 1–2

7

A1 jo’

IMIX

chan mak

5 Imix 4 Mak [9.12.9.8.1, Oc-

tober 23, AD 681]

B2 u tzakaw k’awiilal

she conjured the “supernatural”

appearance

C1 u tok’ pakal

of the flint and shield

D1 aj k’ak’ o chaak

Aj K’ak’ O Chaak [denomina-

tion for the figure in the maw]

E1 u k’uhul tzak

it is the divine conjuring of the

F1 chan winikhaab?

4 K’atun

ajaw

lord

F2 itzamnaaj b’ahlam Shield-Jaguar

F3 u cha’n aj nik

he is the captor of Aj Nik

F4 k’uhul siijyaj-chan? Holy lord of

ajaw bakab

Yaxchilán Bakab

G1 u ba’anil na’ ohl

this is her depiction of the first

entrance

G2 wi’-te’-naah

(into the) house of the dynasty

founder

H1 ch’ahom

the “Scatterer” is

I1 ixik k’abal xook

Lady K’abal Xook

I2 u yoktel

(it is) her “appearance”

I3 tan ha’ siijyaj-chan? on the plaza of Yaxchilán

Table 1: Yaxchilan, Lintel 25, Inscription (Transliteration and

translation: Sven Gronemeyer)

Methods of bloodletting

Several body parts were used for the withdrawal of blood

as well as a series of instruments to puncture and perforate

and various methods to catch the blood.

Iconographic and figurative representations of both

Classic and Postclassic periods show the piercing of the

tongue, penis and ear lobe to withdraw blood (Figures

1a–c). Ethnohistorical sources further testify to bloodlet-

ting from the arms (Tovilla 1960: 183) and the lips and

cheeks (Landa 1959: 49). Within the framework of this

paper, I will limit myself to tongue and penis perforations

because of the abundance of the sources. e ear lobe sac-

rifice is limited to the Codex Madrid. Schele and Miller

allude in their discussion of the so-called “scattering rite”

to the withdrawal of blood from the groin (Schele and

Miller 1986: 182–183). e scattering rite usually depicts

the dropping of what looks like pellets and is interpreted

as the casting of liquids which remain unspecified in the

inscriptions. Since this rite is exclusively carried out by

men, Schele and Miller presumably refer to the perforation

of the penis here. Diego de Landa confirms these practices

in his Relación and continues to explain (Landa 1959: 49,

chapter 28):

Que hacían sacrificios con su propia sangre cortándose

unas veces las orejas a la redonda, por pedazos, y así las

dejaban por señal. Otras veces se agujeraban las mejillas,

otras el labio de abajo; otras se sajaban partes de sus cu-

erpos; otras se agujeraban las lenguas, al soslayo, por los

lados, y pasaban por los agujeros unas pajas con grandísi-

mo dolor; otras, se harpaban lo superfluo del miembro

vergonzoso dejándolo como las orejas, [...].

ey offered sacrifices of their own blood, sometimes cut-

ting themselves around in pieces and they left them in

this way as a sign. Other times they pierced their cheeks,

at other their lower lips. Sometimes they scarify certain

parts of their bodies, at others they pierced their tongues

in a slanting direction from side to side and passed bits of

straw through the holes with horrible suffering, other slit

the superfluous part of the virile member leaving it as they

did their ears, […] (Translated in Tozzer 1941: 113–114)

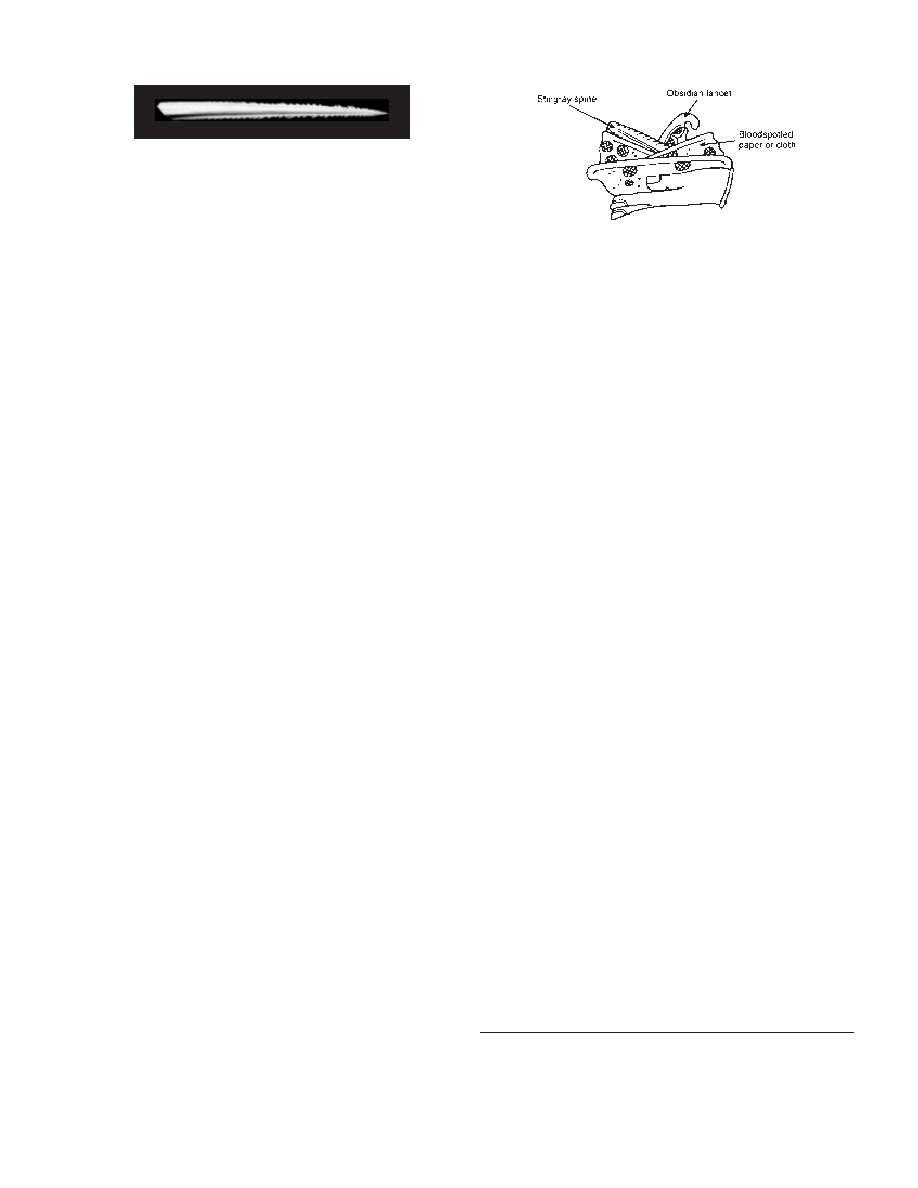

Different instruments were available to the Maya to pierce

their body and to draw blood. Very common were the

spines of native stingrays (Figure 3), lancets that imitate

stingray spines (2), obsidian and flint blades, agave thorns,

or bone awls. Such instruments are shown in the sacrificial

bowl on Lintel 25 from Yaxchilán (Figure 4).

e perforation of the tongue

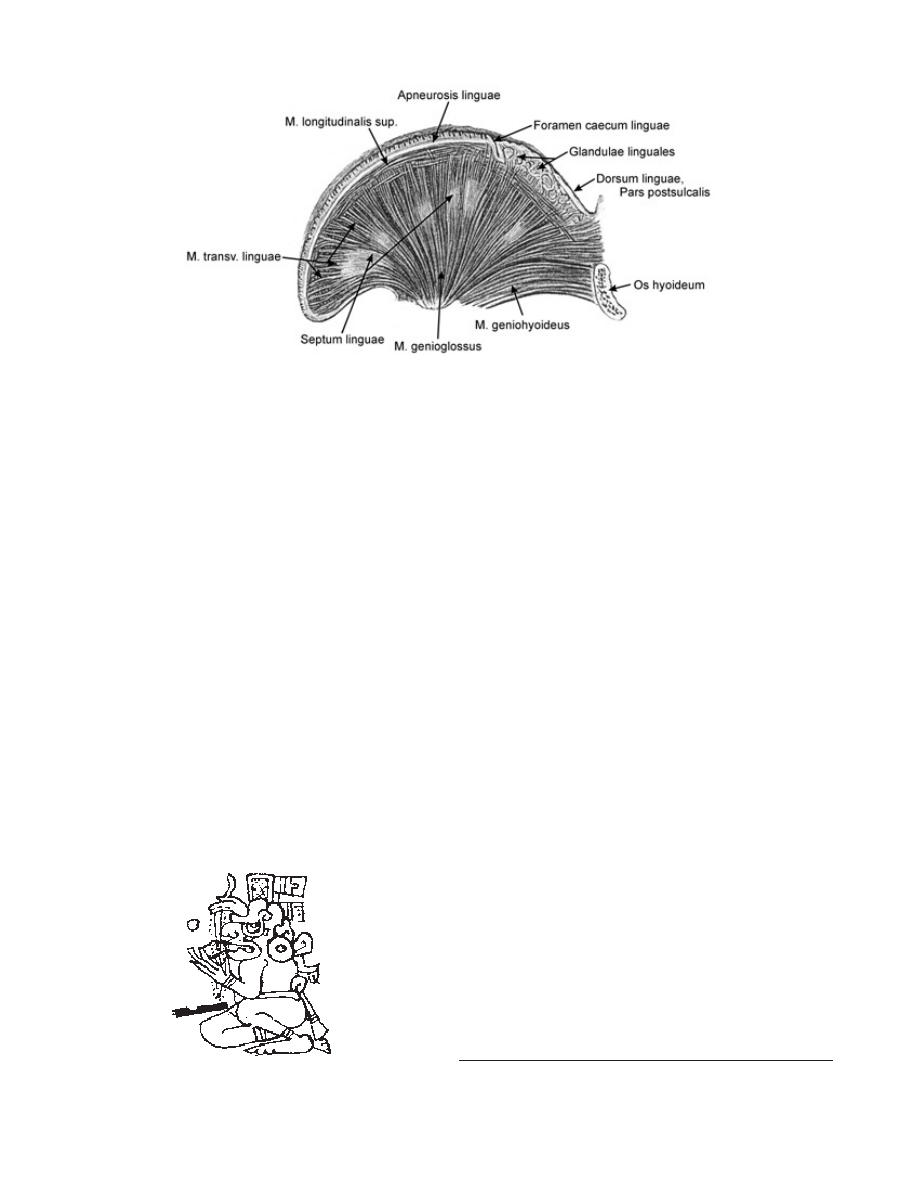

I proceed with some remarks about the anatomy of the

tongue (Lingua, Figure 5). e tongue fills the whole length

and width of the oral cavity and is an essential auxiliary or-

gan for tasting, speaking and chewing. One distinguishes

between external tongue muscles which essentially are used

Figure 3. Spine of the Atlantic Stingray (Dasyatis sabina), which

has its circulation area in the Gulf of Mexico. Download from

http://nersp.nerdc.ufl.edu/~pmpie/spine.jpg on 07-16-2000.

Figure 4. Detail from Yaxchilan Lintel 25. e hand of Lady

Xook holds a sacrificial bowl with several instruments. Drawing:

Sven Gronemeyer after Graham 1977: 3-55.

(2) According to Christian Prager (pers. communication: 1999) such

lancets could have been set into the wound to secure a continuous flow

of blood after the wounds had been pierced by other implements. On ac-

count of the presence of “Perforator God” motives (cf. Joralemon 1974:

62), such lancets presumable only had symbolic function, since jade also

produces no sufficiently sharp blade in order to make a cut.

8

Human Mosaic

Volume 34, Numbers 1–2

9

for the movement of the whole organ and the inner mus-

cles that modify the shape of the tongue. e coordination

of both types can occur synchronously. e motor nerve on

the topside stretches to the tip of the tongue (Apex linguae)

(Blotevogel 1950: 29f).

Iconographic examples suggest that the tongue was

pierced in the area of the tip. is is for example displayed

in the painting on the eastern wall of Room 3 of Structure

1 in Bonampak, and in the Codex Madrid (Figure 6). It

remains, however, unclear, how the tongue was held during

the perforation so that it would not slip out of one’s grasp.

e tongue was possibly dried with a piece of cloth before

the perforation. Another very simple method to immobi-

lize the tongue, though it cannot be demonstrated, is to

place the outstretched tongue onto a plane base on which it

would then be supported immobile.

One should also point out that a perforation of the

tongue involves the risk of an infection or even sepsis re-

sulting from the use of unsterilized instruments. e pro-

cess of healing a cut into the tissue caused by sharp blades

takes more time than other injuries, because the tissues

are completely severed and connecting fibers need to be

rebuilt. In the opinion of Rainer Brocksieper, physician for

inner medicine consulted on this topic, food intake delays

the healing of a tongue wound. We can also assume that

chewing problems occurred and that the reduced flexibility

of injured tongue muscles may have resulted in disarticula-

tion.

Information about the measures of the cord that was

pulled through the tongue must remain speculative. How-

ever, the iconographic material allows to recognize that the

cord was pulled through the tongue from top to bottom.

One can see on Lintels 17 and 24 from Yaxchilan how

the hand which holds the cord above the tongue shapes a

kind of loop with three fingers, through which the rope is

moved. e other hand clasps the cord in order to pull it

through the perforation in the tongue, then the cord drops

into a basket filled with other offerings. On Lintel 24 of

Yaxchilán (Figure 1a) the thorns incorporated into the rope

are pulled through the wound with their ventral side com-

ing first. If pulled the other way, they would have bored

into the underside of the tongue like barbs.

One should consider the inscription (3) that accompa-

nies the scene on Lintel 24 of Yaxchilán (Table 2).

A1 ti jo’

EB

’

on [the day] 5 Eb

B1 jo’lajun mak

15 Mak [9.13.17.15.12, Octo-

ber 28, AD 709],

u b’aah

it is her image

C1 ti ch’abil

while creating

D1 ti k’ak’al hul

under the fire-staff

E1 u ch’ab chan

he creates, the 4

winikhaab? ajaw

the 4 K’atun lord

F1 itzamnaaj b’alam

Shield Jaguar,

Figure 5. Anatomy of the human tongue, longitudinal section. Drawing left by Rainer Brocksieper, modified.

Figure 6. God B perforates his tongue by grasping the tip. Note

the dots surrounding the blade. ey may represent sawtooths.

Codex Madrid, p. 96b. Drawing: Sven Gronemeyer.

(3) In this paper the inscriptions (Tables 1 and 2) will be given without

transcription and morphological segmentation, but only purely phone-

mic. I will also not discuss for reasons of clarity the often conflicting

readings.

8

Human Mosaic

Volume 34, Numbers 1–2

9

u cha’n

he is the captor of

F2 aj nik

Aj Nik

F3 k’uhul siijyaj-chan? Holy Lord of

ajaw

Yaxchilán

G1 u baah ti ch’abil

it is her image while creating

G2 ixik ch’ak kaban

Lady Ch’ak Kaban

G3 ixik k’abal xook

Lady K’abal Xook

G4 ixik kaloomte’

Lady Kaloomte’

Table 2: Yaxchilan, Lintel 24, Inscription (Transliteration and

translation: Sven Gronemeyer)

It can be seen that the inscription identifies the partici-

pants (Shield Jaguar and Lady K’abal Xook) and provides

a partial description of the scene (see the allusion to the

fire-staff). Yet, the text makes no explicit reference to the

blood sacrifice (4).

e perforation of the penis

e perforation of the penis is not only common in re-

cords from the Classic and Postclassic periods (e.g., Codex

Madrid, f. 19b and 82b; Figure 1b) but was also noted

in Colonial accounts. Francisco Ximénez gives a detailed

and medically interesting description about blood sacrifice

among the Manché-Chol-Maya (1973: 164, chapter 31):

En la ranchería de Vicente Pach vi los sacrificios. Cogían

un cincel y un mazo de palo, ponían al que se había de

sacrificar sobre una losa de piedra lisa, sacábanle el viril y

se lo partían en tres partes, quedando la mayor en medio,

cosa de dos dedos a lo largo, [...] sin echar gota de sangre

y al parecer sin sentimiento de el paciente [...].

In Vicente Pach’s ranch I saw the sacrifice. ey took a

chisel and wooden mallet, placed the one who had to sac-

rifice himself on a smooth stone slab, took out his penis

and cut it in three parts two finger breadths [up], the larg-

est in the center […]. e one who was undergoing the

operation did not seem to suffer, and did not lose a drop

of blood. (Translated in Schele and Miller 1986: 180)

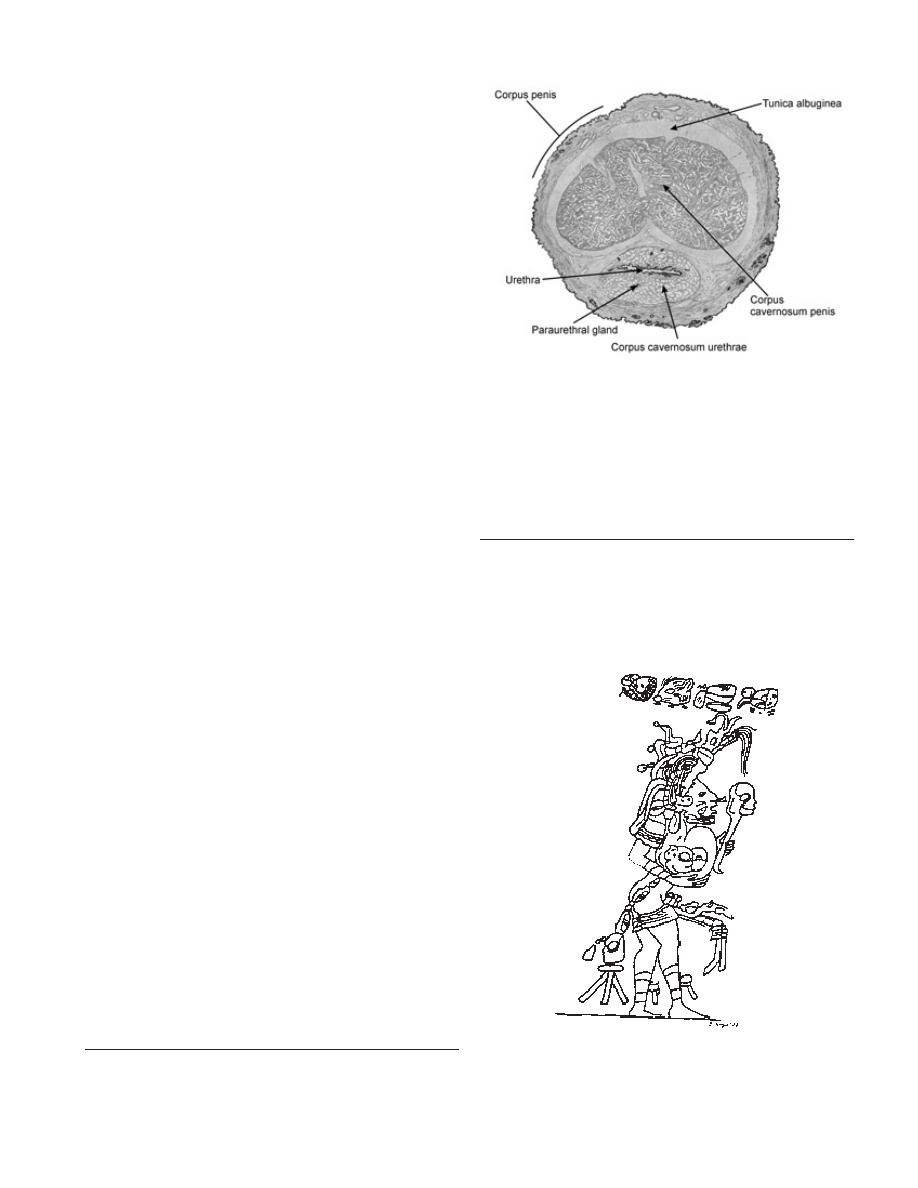

To understand the damage that can be done to the penis by

blood sacrifice, a short anatomical description is in order.

e penis (Corpus penis, Figure 7) surrounds the ureter

(Urethra) and two erectile tissues, the Corpus cavernosum

penis on the dorsal side and the Corpus cavernosum urethrae,

that runs out into the glans (Glans penis), on the ventral

side. e foreskin (Orificium praeputii) covers the glans as

the prolongation of the Corpus penis. e entire erectile tis-

sue is covered by a layer of connective tissue about 1 mm in

thickness, the Tunica albuginea. (Blotevogel 1951: 149f.)

e Ch’ol rite (5), the Jaina figurine (Figure 1b), the

representations in the Codex Madrid, and most important-

ly, the persons on the ceramic vessel K3844 who have bone

Figure 7. Anatomy of the human penis, cross-section . In: Barg-

mann 1967: 561, modified.

(4) In all inscriptions accompanying scenes of blood sacrifice, the word

“blood” is never mentioned. Instead of this, e.g. as seen on YAX Lnt. 24,

the text speaks about “creating” something through the bloodletting,

expressed by the sign T712, /CH’AB/ (Stanley Guenter, personal com-

munication in 2001).

Figure 8. Detail from vessel K3844. e standing person features

a pointed instrument in the penis and a bundle in the right arm

inscribed with ek’ b’ahlam. Drawing: Elisabeth Wagner. In: Kre-

mer and Uc Flores 1996: figure 8.

(5) For this source cf. Joralemon 1974: figure. 5. e three markings on

the glans could very well be similar representations of the description

given by Francisco Ximénez (Joralemon 1974: 61). Also the markings on

the penis of the right figure on the south balustrade of House A of the

Palenque Palace (cf. Greene Robertson 1985: figure 290) as well as those

on the “penis glyph” T761 may very well represent the same description

(for a more iconographic approach hereto cf. Jones 1994: 81f.).

10

Human Mosaic

Volume 34, Numbers 1–2

11

awls plugged into their male organs (Kerr 1992: 443, Fig-

ure 8) evince the wounding of the Corpus penis or the glans

respectively. One could pierce the dorsal side in a slanting

direction to avoid an injury of the urethral duct. e icono-

graphic material gives no indication that cords were used

during the perforation of the Corpus penis. Yet, the Relacíon

geográfica y histórica de Panama written by Requejo Salcedo

in 1640 mentions that the foreskin was pierced (quoted

after Tozzer 1941: 114, note 525):

ey make a hole in the foreskin of the penis with a fish

spine, and through these with a cotton cord, half a finger

in width, they all thread themselves together [...].

As with tongue piercing, the danger of infection during

the perforation of the penis existed. No further side ef-

fects occurred while piercing the foreskin, but as Rainer

Brocksieper pointed out to me, during the perforation of

the Corpus penis or the glans the danger of an injury of the

ureter existed. is damage would have caused pain while

urinating. With scaring of the tissue, the danger of clos-

ing of the urethral duct existed, which could lead to death

by kidney failure. An injury to the erectile tissue and to

the surrounding Tunica albuginea may, in addition, have

resulted in a temporary loss of sensitivity of the glans and

temporary erectile problems.

Let us refer to Jürgen Kremer and Fausto Uc Flores’s

investigation (1993: 86f.) to answer how infections were

possibly prevented. On vessel K3844 a figure carries a bun-

dle inscribed with ek’ b’ahlam, the name of a herb (Croton

flavens) whose leaves have a strong styptic effect (Kremer

and Flores 1993: 87). To what extent a sore supply of the

tongue took place must remain undetermined for the mo-

ment, as well as the question whether the techniques of

perforation and sore supply were secret medical knowledge

(6). As Alexander Voß pointed out to me, a herb called

(x-) kaka(l)tun (cf. Roys 1976) contains iodine and may

have been used for sterilization of the instruments and the

wounds.

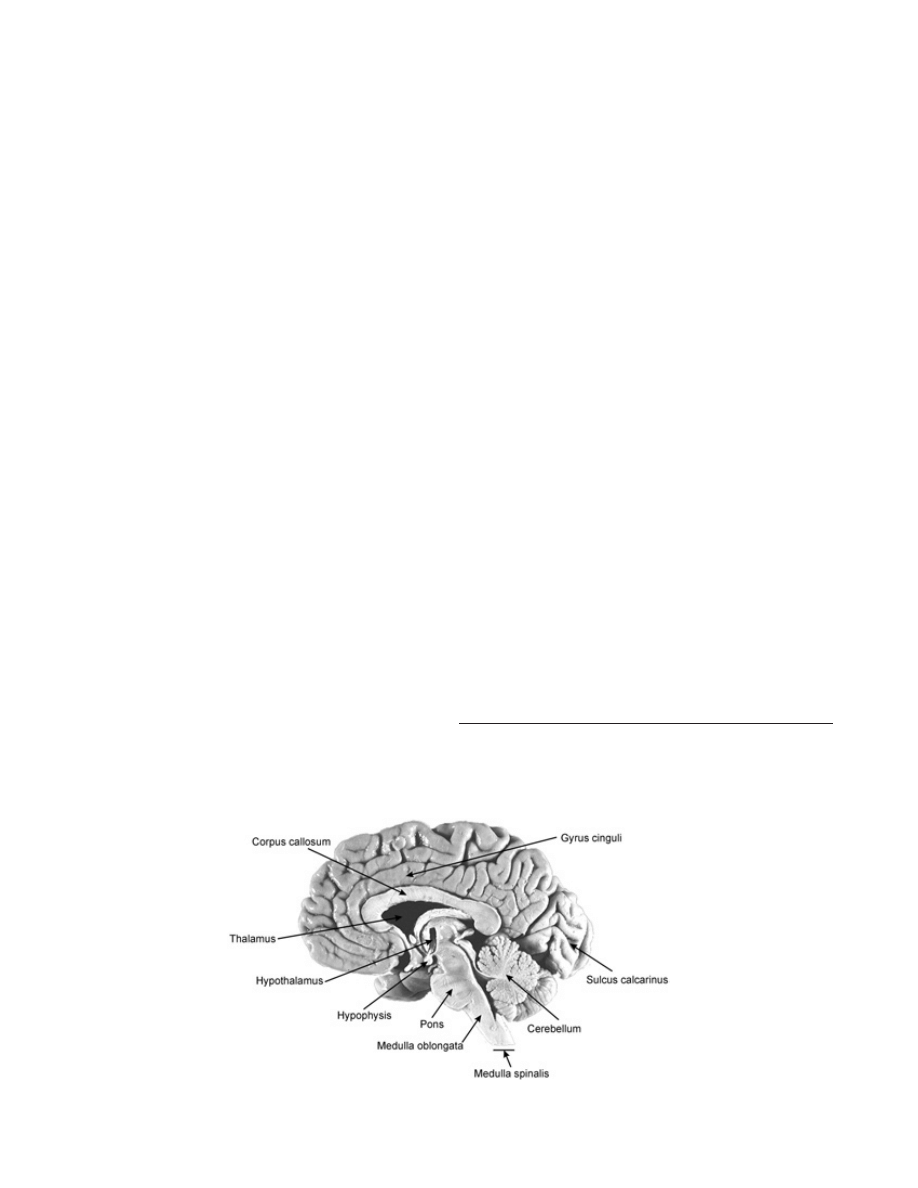

e organic basis for entering into trances

Although it may sound paradoxical at first, no sharp separa-

tion between the different states of human consciousness

actually exist. Between the extremes of being awake and

the state of trance exists a gradual transition from one state

of consciousness into another (Luczak 1999: 16). As results

from researches on hypnosis have shown, people with high

creativity and imagination are considerably more suscep-

tible to altered states of consciousness. During trance, an

increase in mental activity is registered in the area of the

Sulcus calcarinus (Figure 9) indicating intense visual hallu-

cinations (Luczak 1999: 16).

Altered states of consciousness can be caused in two

ways: in a pharmacological manner and in a psychological

manner. e stimulants for the first type are hallucinogenic

drugs. Psychological stimulants are specific techniques for

the attainment of a trance state.

In a series of experiments, it was determined that simple

alterations of consciousness and slight trance merely influ-

ence thinking and cause interferences in concentration, a

feeling of loosing self-control, strong fluctuations in mood

and intense emotionality. In this way, hard trances, above

all, cause modifications in the optical perception: halluci-

nations of colour and shape occur, and in extreme cases

even scenic imaginations (Luczak 1999: 19).

Figure 9. Anatomy of the human brain, longitudinal section.

Download from http://www1.biostr.washington.edu on 09-10-1999, modified.

(6) e fact, that the contemporary milperos of Yucatán still use ek’ b’alam

(Kremer and Flores 1993: 86) might speak against secret knowledge that

was lost with the ancient elite.

10

Human Mosaic

Volume 34, Numbers 1–2

11

e perforation as a trigger of hallucinogenic effects?

Since the blood sacrifice was the central part of the entire

rite, should one also consequently assume that it caused al-

tered mental states? Linda Schele and Mary Miller asserted

that this might be possible, namely with the release of en-

dorphins caused by the sensed pain and the loss of blood

during the sacrifice (Schele and Miller 1986: 177).

Pain is directly passed on by receptors embedded in the

skin and the inner organs to several regions of the brain.

Periphery nerve fibers direct the irritation directly to the

spinal cord (Medulla spinalis). e perception of the inten-

sity of the pain takes place in the Gyrus cinguli region of the

brain, whereas the subsequent sensation of pain after the

initial perception is produced by biochemical reactions in

the thalamus.

As the physicians from the county hospital pointed out

to me, experiments have shown that the fear of undergoing

painful procedures may cause an intensifying of the actual

sense of pain. Equally, in the opinion of Dr. Pfennig from

the county hospital consulted on this topic, it may be of

importance whether the perforation is carried out alone or

with the aid of trusted assistants, as mentioned previously

by Ximénez on the Manché-Chol. eoreticians of behav-

ior demonstrated in series of experiments that angst can

be learned, unlike innate fright. Consequently, suppressing

of fear is also possible to learn (Benesch 1998: 101). By

embedding the act of perforation into a ritual context, this

may perhaps have increased pain tolerance or caused the

participants to accept pain stoically (cf. Furst 1974: 186).

Endorphins are endogenic, pain-blocking oligopeptides

that are produced in the pituitary gland (Hypophysis) and

the hypothalamus and that react with opiate receptors in

the thalamus (Figure 9), the limbic system and the brain

stem and adjust the sensation of pain directly in the brain.

ey are chemically related to the opiate alkaloids to which

include morphine. According to Dr. Heusler from the

county hospital endorphins produced in the brain as a re-

flex to pain during perforation are of insufficient quantities

to achieve a concentration that would induce a hallucina-

tion. ey are also reduced through the action of specific

enzymes in a very short period of time. e endorphins

would have to be synthesized again very quickly to main-

tain a specific concentration, but this is actually not the

case. Consequently, this aspect falls short of a convincing

explanation for entering a trance state as Schele and Miller

assumed.

However, what endorphins may cause is an euphoric

elation, a reason why they are colloquially termed “luck

hormones”. After the consumption of drugs containing

opiates, one can find a similar behavior among addicts: af-

ter extreme happiness, a stage of depression occurs with the

diminution of the effect. A similar effect is known from afi-

cionados of extreme sports: endorphins can cause addiction

because of their opiate-analogous structure and perennially

require new avenues for release.

e loss of blood would then, after Schele and Miller,

remain the only possible explanation for the occurrence of

hallucinations. Extreme loss of blood can, indeed, induce a

comatose state in which a person can perceive visions, but

in this case the loss of blood is so extreme that death is

fairly inevitable. Even if strong hemorrhages did indeed oc-

cur during the rite, the loss of blood would never have been

large enough, because of the peculiar anatomy of the re-

spective organs. A professional piercer consulted by the au-

thor states that the loss of blood is most often so little that it

is barely recognized. (Of course, one must also be aware of

the fact that the hole for the piercing which is to be inserted

into it is often only 2 mm in diameter.) Nevertheless, all the

explanations for the incidence of hallucinations caused by

the blood sacrifice as proposed by Schele and Miller are not

viable from a medical standpoint.

One should not assume that it was impossible to induce

hallucinations during blood sacrifice. In my opinion, hal-

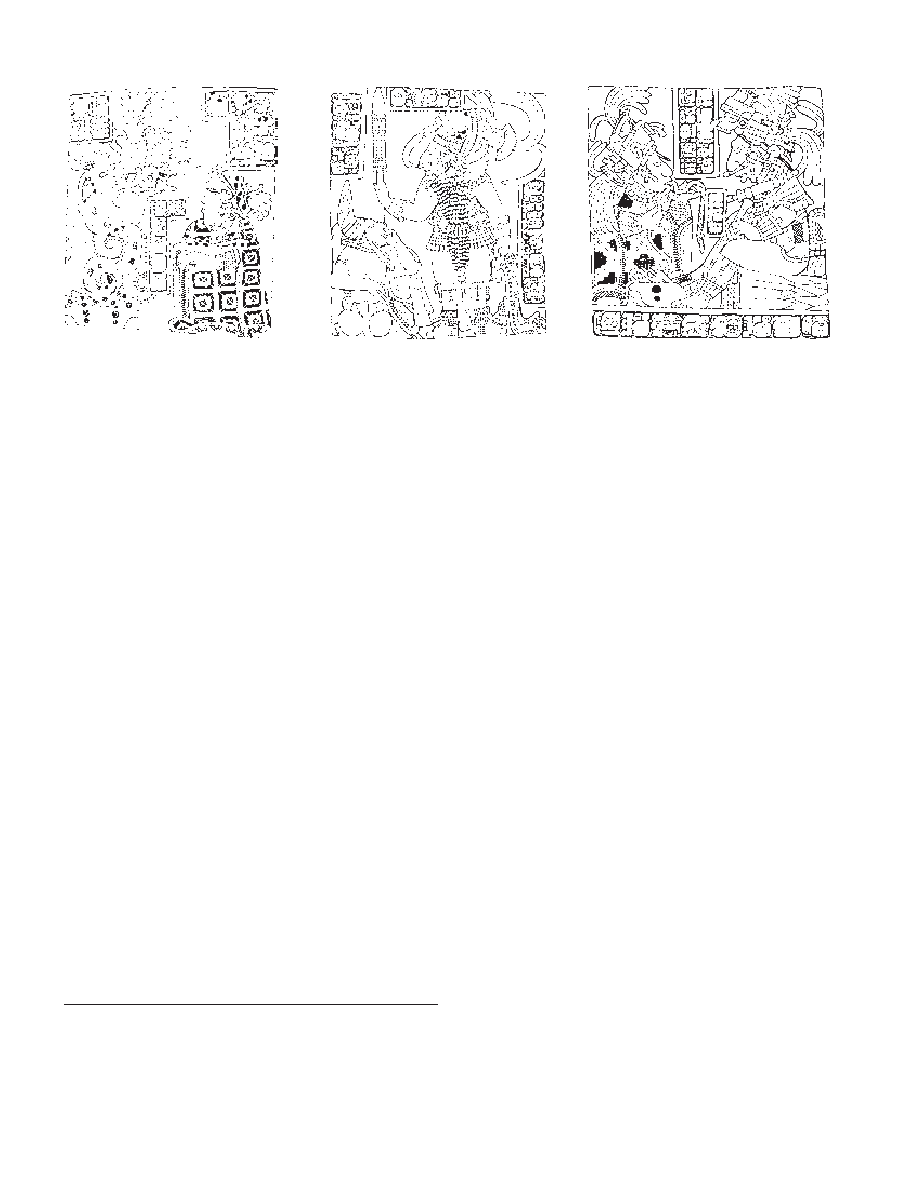

Figure 10. Lady Xook gazes at the rising vision serpent above

a bowl similar to the one seen in Figure 1a. Note the bowl she

holds containing bloodletting equipments. Yaxchilan Lintel 25.

Drawing: Ian Graham. In: Graham 1977: 3-55.

12

Human Mosaic

Volume 34, Numbers 1–2

13

lucinogens of vegetable and animal origin were of signifi-

cant importance in entering states of altered consciousness,

likely in connection with psychological stimulants. ese

psychological stimulants were part of the preparations

to the blood sacrifice that included days of fasting and

ritual steam-baths as described by Landa (Schele and Miller

1986: 178; cf. Furst 1974: 188), sensory monotony (Mac

Leod and Puleston 1978: 75f.) (7), and perhaps ritual

dance (8). e weakening of the body caused by fasting

and steam-baths leads to a state of hypoglycemia which

may cause neurological deficiency symptoms including

psychotic states and light trances. I am still unable to deter-

mine a direct relationship between the taking of psychiatric

drugs, blood sacrifice, vision and subsequent dance, since

the inscriptions provide no such reference.

e steps involved in bloodletting rites

In what sequence were the individual steps of a ritual that

involved bloodletting performed? By means of the series of

Lintels 24 to 26 of Structure 23 in Yaxchilán (cf. Figures 1a

and 10), which show blood sacrifice – vision – war motif,

Linda Schele and Mary Miller determined a template for

sacrificial actions (Schele and Miller 1986: 177). In Yax-

chilan Structure 21 a similar series exists in the form of

Lintels 15 to 17, but one that follows the sequence vision

– war motif – blood sacrifice (Figure 11). Schele and Miller

remark that the motif sequence in Structure 21 is not

identical with the one from Structure 23, yet, they didn’t

alter their overall hypothesis about the sacrificial sequence,

developed on the sequence from Structure 23.

One can examine their sequence from two perspectives:

(a) the dates contained in the texts, and (b) the content

of the inscriptions and their relation to the iconographic

scenes.

e dates on the lintels show that there are time gaps of

several years (Lintel 24: 9.13.17.15.12 5 Eb’ 15 Mak, Oc-

tober 28, 709, Lintel 25: 9.12.9.8.1 5 Imix 4 Mak, October

23, 681, Lintel 26: 9.14.12.6.12 12 Eb’ 5 Wayeb’, February

12, 724). Solely because of this reason, a direct association

of the proposed parts of the sacrificial sequence is question-

able and a cause-and-effect relationship is not given.

Furthermore, as pointed out throughout the paper, we

are not able to determine a direct relationship between

text and image. e explicit mentioning of blood never

occurs in connection with sacrificial actions. e action

of “creating” something, expressed by T712 in the context

of the bloodletting scenes, never occurs in scenes involving

the vision serpent. A closer examination of epigraphy and

iconography reveal further inconsistencies when compar-

ing these details with the sequence proposed by Schele and

Miller. On Lintel 25 from Yaxchilán, Lady Xook is seen

without the iconographic markers on her cheek which are

commonly interpreted as blood markers and which she

likely spilled during the bloodletting displayed on Lintel

24. e inscription (Table 2) of Lintel 25 reports that she

had shedded a substance, probably blood, in the interior of

the house of the dynasty founder and afterwards stepped

out onto the plaza of Yaxchilán (G1–I3). is description

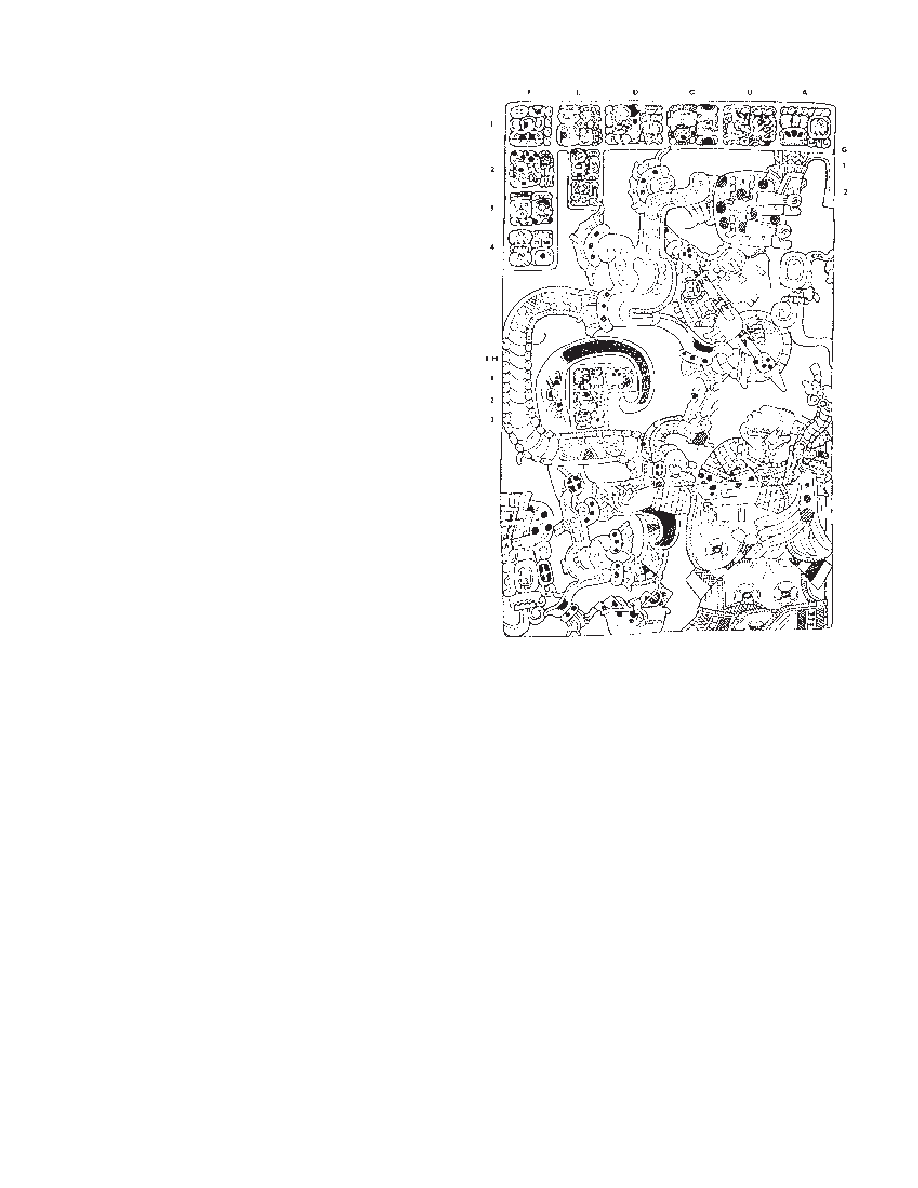

Figure 11. Lintels 15, 16 and 17 from Yaxchilan. (a) Lintel 15 shows a the appearance of the vision serpent (compare with Figure 10),

(b) Lintel 16 displays the capture of noble in the rank of a sajal, and (c) Lintel 17 shows Bird Jaguar IV and his wife, Lady Mut B’ahlam

offering blood. She pulls a cord through her tongue (compare with Figure 1a), while he uses a bone awl to draw blood from his male

organ. Drawings: Ian Graham. In: Graham 1977: 3-39, 3-41, 3-43.

a

b

c

(7) e authoress withdrew herself, together with other subjects, for 48

hours into total darkness and silence in a cave. A state similar to medita-

tion was reported to result after time.

(8) Excessive dancing can affect the psyche in connection with a monot-

onous-rhythmical stimulation through music (as in our contemporary

techno culture) and generate trances by stimulus satiation, people almost

“drown” in a strong sensory input. A public performance of these rites

may easily have stimulated collective trances and mass hysteria.

12

Human Mosaic

Volume 34, Numbers 1–2

13

stands after the text position containing the description of

the conjuring (B1–D1).

ough these examples show that we have to reconsider

the sequence of steps during the ritual, current proposals

of how the blood sacrifice and the vision quest actually

were connected and carried out would remain tentative

and speculative since it cannot be reconstructed from the

sources we have at hand.

Summary

After presenting and discussing some of the methods and

accompanying rituals and equipment the Maya used to

withdraw blood from the body, I examined whether it is

possible to produce visions by bloodletting. I conclude

that the direct cause-and-effect relationship between blood

sacrifice and trances that Linda Schele and Mary Miller ad-

vanced in their book “e Blood of Kings” are not tenable

from a medical point of view. I suspect that trances were

rather provoked by a combination of pharmacological and

psychological stimulants. It should be noted that we have

to reconsider the sequence of ritual events that involved

bloodletting. e evidence we have from epigraphy and

iconography does not support any hypothesis of how these

events were connected or carried out, mostly the result of a

missing one-to-one relation between text and image.

Acknowledgements

For their assistance during the realization of this manuscript

and their crucial reflection and discussion I thank Berthold

Riese and Nikolai Grube as well as Christian Prager, Alexander

Voß, Markus Eberl, Elisabeth Wagner, Pierre Robert Colas, and

Stanley Guenter. – In the case of the medical questions I thank

Rainer Brocksieper, doctor for inner medicine in Halver and the

Drs Harald Heusler, Udo Pfennig and Doris Bartels from the

Kreiskrankenhaus Lüdenscheid. For their friendly help I further

acknowledge Kerstin Eva-Maria Becker from the hospital admin-

istration and Julika Bauckhage from the library of the house.

Bibliography

Bargmann, Wolfgang

1967

Histologie und mikroskopische Anatomie

des Menschen. 6th edition. Stuttgart: Gustav

ieme.

Barrera Vasquez, Alfredo

1980

Diccionario Maya Cordemex, Maya–Español, Es-

pañol–Maya. Mérida: Ediciones Cordemex.

Baudez, Claude F.

1980

e Knife and the Lancet: e Iconography of

Sacrifice at Copán. In: Proceedings of the Fourth

Palenque Round Table, vol. 6. Elizabeth Benson,

ed. Pp. 203–210. San Francisco: Pre-Columbian

Art Research Institute.

Benesch, Hartmut, ed.

1998

Grundlagen der Psychologie. Studienausgabe.

Band 6: Persönlichkeitspsychologie und Psycho-

therapie. Augsburg: Bechtermünz.

Blotevogel, Wilhelm

1950

Anatomie des Menschen. Zweiter Teil. München:

Tropon-Werke.

1951

Anatomie des Menschen. Dritter Teil. München:

Tropon-Werke.

Boot, Erik

2000

Architecture and Identity in the Northern Maya

Lowlands: e Temple of K’uk’ulkan at Chich’en

Itsa, Yucatan, Mexico. In: e Sacred and the Pro-

fane: Architecture and Identity in the Maya Low-

lands. Acta Mesoamericana, 10. Pierre R. Colas,

Kai Delvendahl, Marcus Kuhnert, and Annette

Schubart, eds. Pp. 183–204. Markt Schwaben:

Verlag Anton Saurwein.

Furst, Peter T.

1974

Fertility, Vision Quest and Auto-Sacrifice: Some

oughts on Ritual Blood-Letting Among the

Maya. In: Proceedings of the Second Palenque

Round Table, vol. 3. Merle G. Robertson, ed. Pp.

181–193. Pebble Beach, Calif.: Robert Louis Ste-

venson School.

Graham, Ian

1977

Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions. Vol-

ume 3 Part 1: Yaxchilán. Cambridge, Mass.: Har-

vard University, Peabody Museum of Archaeology

and Ethnology.

1979

Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions. Vol-

ume 3 Part 2: Yaxchilán. Cambridge, Mass.: Har-

vard University, Peabody Museum of Archaeology

and Ethnology.

Grube, Nikolai

1991

Tzak. In: Notebook for the XVth Maya Hiero-

glyphic Workshop at Texas. Linda Schele, ed. Pp.

86–90. Austin: University of Texas.

1992

Classic Maya Dance. Evidence from hieroglyphs

and iconography. Ancient Mesoamerica 3(2):

201–218.

Islas, Melinda D.

1990

e Blood Speaks: Maya Ritual Sacrifice. Unpub-

lished Master esis, Department of Anthropol-

ogy, University of Arizona.

Jones, Tom

1994

Of Blood and Scars: A Phonetic Rendering of

the ‚Penis Title‘. In: Proceedings of the Seventh

Palenque Round Table, vol. 9. Merle G. Robert-

son, ed. Pp. 79–86. San Francisco: Pre-Columbian

Art Research Institute.

14

Human Mosaic

Volume 34, Numbers 1–2

15

Joralemon, David

1974

Ritual Blood-Sacrifice among the Ancient Maya.

Part I. In: Primera Mesa Redonda de Palenque,

vol. 2. Merle G. Robertson, ed. Pp. 59–75. Pebble

Beach, Calif.: Robert Louis Stevenson School.

Kerr, Justin

1992

e Maya Vase Book: A Corpus of Rollout Pho-

tographs of Maya Vases, vol. 3. New York: Kerr

Associates.

Kremer, Jürgen and Fausto Uc Flores

1996

e Ritual Suicide of Maya Rulers. In: Proceed-

ings of the Eighth Palenque Round Table, vol. 10.

Merle G. Robertson, ed. Pp. 79–91. San Fran-

cisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute.

Landa, Diego de

1959

Relación de las cosas de Yucatán. 8th edition.

Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa.

Löffler, Georg

1994

Funktionelle Biochemie. Eine Einführung in die

medizinische Biochemie. 2nd edition. Berlin:

Springer .

Luczak, H.

1999

Nicht von allen guten Geistern verlassen. GEO-

Magazin 09/1999: 14–21.

Mac Leod, Barbara, and Dennis E. Puleston

1978

Pathways Into Darkness: e Search For e Road

to Xibalbá. In: Proceedings of the ird Palenque

Round Table, vol. 4. Merle G. Robertson, and

Donnan C. Jeffers, eds. Pp. 71–77. Monterrey:

Pre-Columbian Art Research Center.

Miller, Mary E.

1986

e Murals of Bonampak. Princeton: Princeton

University Press

Proskouriakoff, Tatiana

1973

e Hand-grasping-fish and Associated Glyphs

on Classic Maya Monuments. In: Mesoameri-

can Writing Systems. Elizabeth Benson, ed. Pp.

165–178. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks.

Pschyrembel

1986

Klinisches Wörterbuch mit klinischen Syndromen

und Nomina Anatomica. 225th edition. Berlin:

de Gruyter.

Riese, Berthold Chr.

1995

Die Maya: Geschichte, Kultur, Religion.

München: C.H. Beck.

Robertson, Merle G.

1985

e Sculpture of Palenque, vol. 2: e Early

Buildings of the Palace and the Wall Paintings.

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Robicsek, Francis, and Donald M. Hales

1989

Maya Heart Sacrifice: Cultural Perspective and

Surgical Technique. In: Ritual Human Sacrifice

in Mesoamerica. Elizabeth Boone, ed. Pp. 49–90.

Washington D.C: Dumbarton Oaks.

Roys, Ralph L.

1976

e Ethnobotany of the Maya. Middle American

Research Institute Publ. 2. Philadelphia: Institute

for the Study of Human Issues.

Ruiz, Andrés C.

1999

El viaje al Otromundo: El camino de chamán en

la religion Maya Clásica. Cuadernos Prehispanicos

16: 5–27.

Schele, Linda

1989

Human Sacrifice among the Classic Maya. In:

Ritual Human Sacrifice in Mesoamerica. Eliza-

beth Boone, ed. Pp. 7–48. Washington D.C:

Dumbarton Oaks.

Schele, Linda, and David Freidel

1990

A Forest of Kings. New York: William Morrow

and Company.

Schele, Linda, and Mary E. Miller

1986

e Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya

Art. Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum.

Stuart, David

1984

Blood Symbolism in Maya Iconography. In: Maya

Iconography. Elizabeth Benson, ed. Pp. 175–221.

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stuart, David, with Stephen Houston, and John Robertson

1999

Recovering the Past: Classic Maya Language and

Classic Maya Gods. In: Notebook for the XXIIIrd

Maya Hieroglyphic Forum at Texas. Nikolai Gr-

ube, ed. Austin: University of Texas.

Tate, Carolyn E.

1992

Yaxchilan. e design of a Maya Ceremonial City.

Austin: University of Texas Press.

ompson, J. Eric S.

1962

A Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. Norman: Univer-

sity of Oklahoma Press.

Tovilla, Martín Alfonso

1960

Relaciones historico-descriptivas de la Verapaz, el

Manché y Lacandon, en Guatemala. Guatemala

City: Editorial Universitaria.

Tozzer, Alfred M.

1941

Landa’s Relación de las Cosas de Yucatan: A trans-

lation. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archae-

ology and Ethnology, 18. Cambridge, Mass: Har-

vard University, Peabody Museum of Archaeology

and Ethnology.

Winters, Diane

1986

A Study of the Fish-in-Hand Glyph, T714: Part 1.

In: Proceedings of the Sixth Palenque Round Table,

vol. 8. Merle G. Robertson, ed. Pp. 233–245. San

Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute.

Ximénez, Francisco

1973

Historia de la Provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa

y Guatemala de la Orden de Predicadores. Libro

Quinto. Ciudad Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional.

Human Mosaic 34(1–2), 2003

Articles

Sven Gronemeyer: Bloodletting and Vision Quest Among the Classic Maya.

A Medical and Iconographic Reevaluation

Michael McBride: X-Ray Toads and “e Enema Pot.” A Maya Vase in the

San Antonio Museum of Art

Nina Müller-Schwarze: Knowing When to Clear the Fields: Manacus vitel-

linus and Swidden Farming in Northern Coclé, Panamá

Markus Eberl: Human Cranial Plasticity. e Current Re-evaluation of Franz

Boas’s Immigrant Study

Rebecca Golden: Violent Cures for Violence: Bad Medicine, Silent Politics,

Evacuation and Transit

Book Reviews

Kerriann Marden reviews Jeff Benedict’s No Bone Unturned: e Adventures

of a Top Smithsonian Forensic Scientist and the Legal Battle for America’s Oldest

Skeletons.

Nina Müller-Schwarze reviews Karl G. Heider’s Seeing Anthropology: Cultural

Anthropology through Film.

Back Cover

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Jouni Yrjola Easy Guide to the Classical Sicilian (feat Richter Rauzer and Sozin Attacks)

SHSBC377 THE CLASSIFICATION AND GRADATION PROGRAM

SHSBC434 The Classification Chart and Auditing

SHSBC434 THE CLASSIFICATION CHART AND AUDITING&0766

Hillary Clinton and the Order of Illuminati in her quest for the Office of the President(updated)

D Stuart The Fire Enters His House Architecture and Ritual in Classic Maya Texts

L Bryce Boyer, Ruth M Boyer, and Harry W Basehart Shamanism and Peyote Use Among the Apaches

Jouni Yrjola Easy Guide to the Classical Sicilian (feat Richter Rauzer and Sozin Attacks)

Exclusive Hillary Clinton and the Order of Illuminati in her quest for the Office of the President

Greg Costikyan Cups and Sorcery 02 One Quest, Hold the Dragons

Coping with Vision Loss Understanding the Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Effects by Cheri Colb

Hillary Clinton and the Order of Illuminati in her quest for the Office of the President(2)

Love and Sex Among the Inverteb Pat Murphy

Gifford, Lazette [Quest for the Dark Staff 06] Freedom and Fame [rtf]

Death and Designation Among the Michael Bishop

Seahra The Classical and Quantum Mechanics of

Hackmaster Quest for the Unknown Battlesheet Appendix

Gifford, Lazette [Quest for the Dark Staff 01] Aubreyan [rtf](1)

Gifford, Lazette [Quest for the Dark Staff 08] Hope in Hell [rtf](1)

więcej podobnych podstron