What Psychedelics Really Do to Your Brain

Inside how ayahuasca, MDMA, DMT and psilocybin mushrooms affect the body – and how

researchers are using them to help people with mental illness.

From mushrooms to MDMA, psychedelics are making a comeback in the therapeutic world.

Hallucinations. Vivid images. Intense sounds. Greater self-awareness.

Those are the hallmark effects associated with the world's four most popular psychedelic drugs.

Ayahuasca, DMT, MDMA and psilocybin mushrooms can all take users through a wild mind-

bending ride that can open up your senses and deepen your connection to the spirit world. Not all

trips are created equal, though – if you're sipping ayahuasca, your high could last a couple of hours.

But if you're consuming DMT, that buzz will last under than 20 minutes.

Still, no matter the length of the high, classic psychedelics are powerful. Brain imaging studies have

shown that all four drugs have profound effects on neural activity. Brain function is less constrained

while under the influence, which means you're better able to emotion. And the networks in your

brain are far more connected, which allows for a higher state of consciousness and introspection.

These psychological benefits have led researchers to suggest that psychedelics could be effective

therapeutic treatments. In fact, many studies have discovered that all four drugs, in one way or

another, have the potential to treat depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, addiction and

other mental health conditions. By opening up the mind, the theory goes, people under the influence

of psychedelics can confront their painful pasts or self-destructive behavior without shame or fear.

They're not emotionally numb; rather, they're far more objective.

Of course, these substances are not without their side effects. But current research at least suggests

that ayahuasca, DMT, MDMA and psilocybin mushrooms have the potential to change the way

doctors can treat mental illness – particularly for those who are treatment-resistant. More in-depth

studies are needed to understand their exact effects on the human brain, but what we know now is at

least promising. Here, a look at how each drug affects your brain – and how that's being used to our

advantage.

Ayahuasca

Ayahuasca is an ancient plant-based tea derived from a combination of the vine Banisteriopsis

caapi and the leaves of the plant psychotria viridis. Shamans in the Amazon have long used

ayahuasca to cure illness and tap into the spiritual world. Some religious groups in Brazil consume

the hallucinogenic brew as religious sacrament. In recent years, regular folk have started to use

ayahuasca for greater self-awareness.

That's because brain scans have shown that ayahuasca increases the neural activity in the brain's

visual cortex, as well as its limbic system – the region deep inside the medial temporal lobe that's

responsible for processing memories and emotion. Ayahuasca can also quiet the brain's default

mode network, which, when overactive, causes depression, anxiety and social phobia,

a video released last year by YouTube channel AsapSCIENCE

. Those who consume it end up in a

meditative state.

"Ayahuasca induces an introspective state of awareness during which people have very personally

meaningful experiences," says Dr. Jordi Riba, a leading ayahuasca researcher. "It's common to have

emotionally-laden, autobiographic memories coming to the mind's eye in the form of visions, not

unlike those we experience during sleep."

According to Riba, people who use ayahuasca experience a trip that can be "quite intense"

depending on the dose consumed. The psychological effects come on after about 45 minutes and hit

their peak within an hour or two; physically, the worst a person will feel is nausea and vomiting,

Riba says. Unlike with LSD or psilocybin mushrooms, people high on ayahuasca are fully aware

that they're hallucinating. It's this self-conscious tripping that has led people to use ayahuasca as a

means to overcome addiction and face traumatic issues. Riba and his research group at Hospital do

Sant Pau in Barcelona, Spain, have also begun "rigorous clinical trials" using ayahuasca for treating

depression; so far, the plant-based drug has shown to reduce depressive symptoms in treatment-

resistant patients, as well as produce "a very antidepressant effect that is maintained for weeks,"

says Riba, who has studied the drug with support from the Beckley Foundation, a U.K.-based think

tank.

His team is currently studying the post-acute stage of ayahuasca effects – what they've dubbed the

"after-glow." So far, they've found that, during this "after-glow" period, the regions of the brain

associated with sense-of-self have a stronger connection to other areas that control autobiographic

memories and emotion. According to Riba, it's during this time that the mind is more open to

psychotherapeutic intervention, so the research team is working to incorporate a small number of

ayahuasca sessions into mindfulness psychotherapy.

"These functional changes correlate with increased 'mindfulness' capacities," Riba says. "We

believe that the synergy between the ayahuasca experience and the mindfulness training will boost

the success rate of the psychotherapeutic intervention."

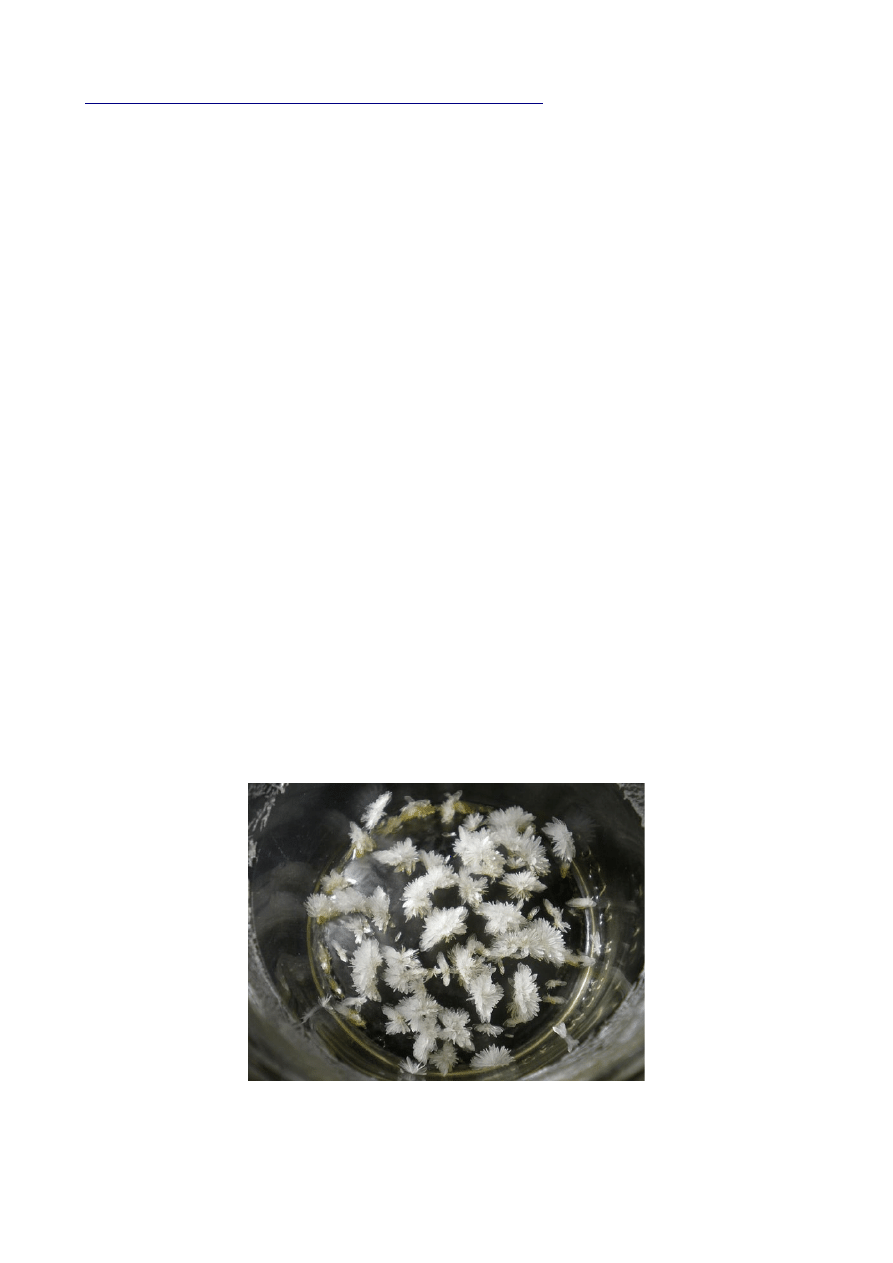

DMT is crystalized so that it can be smoked.

DMT

Ayahuasca and the compound N,N-Dimethyltryptamine – or DMT – are closely linked. DMT is

present in the leaves of the plant psychotria viridis and is responsible for the hallucinations

ayahuasca users experience. DMT is close in structure to melatonin and serotonin and has

properties similar to the psychedelic compounds found in magic mushrooms and LSD.

If taken orally, DMT has no real effects on the body because stomach enzymes break down the

compound immediately. But the Banisteriopsis caapi vines used in ayahuasca block those enzymes,

causing DMT to enter your bloodstream and travel to your brain. DMT, like other classic

psychedelic drugs, affect the brain's serotonin receptors, which research shows

vision, and sense of bodily integrity

. In other words: you're on one hell of a trip.

Much of what is known about DMT is thanks to Dr. Rick Strassman, who first published

groundbreaking research on the psychedelic drug

. According to Strassman, DMT

is one of the only compounds that can cross the blood-brain barrier – the membrane wall separating

circulating blood from the brain extracellular fluid in the central nervous system. DMT's ability to

cross this divides means the compound "appears to be a necessary component of normal brain

physiology," says Strassman, the author of two quintessential books on the psychedelic, DMT: The

Spirit Molecule and DMT and the Soul of Prophecy.

"The brain only brings things into its confines using energy to get things across the blood-brain

barrier for nutrients, which it can't make on its own — things like blood sugar or glucose," he

continued. "DMT is unique in that way, in that the brain expends energy to get it into its confines."

DMT actually naturally occurs in the human body, and is particularly present in the lungs.

Strassman says it may also be found in the pineal gland – the small part of the brain associated with

the mind's "third eye." The effects of overly active DMT when ingested via ayahuasca can last for

hours. But taken on its own – that is, smoked or injected – and your high lasts only a few minutes,

according to Strassman.

Although short, the trip from DMT can be intense, more so than other psychedelics, Strassman says.

Users on DMT have reported similar experiences to that of ayahuasca: A greater sense of self, vivid

images and sounds and deeper introspection. In the past, Strassman has suggested DMT to be used

as a therapy tool to treat depression, anxiety and other mental health conditions, as well as aid with

self-improvement and discovery. But studies of DMT are actually scarce, so it's hard to know the

full extent of its therapeutic benefits.

"There isn't much research with DMT and it ought to be studied more," Strassman says.

MDMA

Unlike DMT, MDMA is not a naturally occurring psychedelic. The drug – otherwise called molly or

ecstasy – is a synthetic concoction popular among ravers and club kids. People can pop MDMA as a

capsule, tablet or pill. The drug (sometimes called ecstasy or molly) triggers the release of three key

neurotransmitters: serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine. The synthetic drug also increases levels

of the hormones oxytocin and prolactin, resulting in a feeling of euphoria and being uninhibited.

The most significant effect of MDMA is the release of serotonin in large quantities, which drains

the brain's supply – which can mean days of depression after its use.

Brain imaging has also shown that MDMA causes a decrease in activity in the amygdala – the

brain's almond-shaped region that perceives threats and fear – as well as an increase in the

prefrontal cortex, which is considered the brain's higher processing center. Ongoing research on

psychedelic drugs and the effects on various neural networks has also found that MDMA allows for

more flexibility in brain function, which means people tripping on the drug can filter emotions and

reactions without being "stuck in old ways of processing," according to Dr. Michael Mithoefer, who

has studied MDMA extensively.

"People are less likely to be overwhelmed by anxiety and better able to process experience …

without being numb to emotion," he says.

Last year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted researchers permission to move ahead

with plans for a large-scale clinical trial to examine the effects of using MDMA as treatment for

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Mithoefer oversaw the phase-two trials – backed by the

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), an American nonprofit founded in

the mid-1980s – that informed the FDA's decision. During the study, people living with PTSD were

able to address their trauma without withdrawing from their emotions while under the influence of

MDMA because of the complex interaction between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. Since

the phase two trials had strong results,

that he expects the

FDA to approve the phase three trial plans sometime early this year.

While research into MDMA's use for PTSD treatment is promising, Mithoefer cautions that the

drug not be used outside of a therapeutic setting, as it raises blood pressure, body temperature and

pulse, and causes nausea, muscle tension, increased appetite, sweating, chills and blurred vision.

MDMA could also lead to dehydration, heart failure, kidney failure and an irregular heartbeat. If

someone on MDMA doesn't drink enough water or has an underlying health condition, the side

effects can be life threatening.

Psilocybin Mushrooms

Mushrooms are another psychedelic with a long history of use in health and healing ceremonies,

particularly in the Eastern world. People tripping on 'shrooms will experience vivid hallucinations

within an hour of ingestion, thanks to the body's breakdown psilocybin, the naturally-occurring

psychedelic ingredient found in more than 200 species of mushrooms.

Research out of the Imperial College London

, published in 2014, found that psilocybin, a serotonin

receptor, causes a stronger communication between the parts of the brain that are normally

disconnected from each other. Scientists reviewing fMRI brain scans of people who've ingested

psilocybin and people who've taken a placebo discovered that magic mushrooms trigger a different

connectivity pattern in the brain that's only present in a hallucinogenic state. In this condition, the

brain's functioning with less constraint and more intercommunication; according to researchers

from Imperial College London,

this type of psilocybin-induced brain activity

seen with dreaming and enhanced emotional being.

"These stronger connections are responsible for creating a different state of consciousness," says Dr.

Paul Expert, a methodologist and physicist who worked on the Imperial College London study.

"Psychedelic drugs are a potentially very powerful way of understanding normal brain function."

Emerging research may prove magic mushrooms effective at treating depression and other mental

health conditions. Much like ayahuasca,

activity in the brain's default mode network, and people tripping on 'shrooms have reported

experiencing "a higher level of happiness and belonging to the world," according to Expert. To that

end, a

study published last year in the U.K. medical journal

of mushrooms reduced depressive symptoms in treatment-resistant patients.

That same study noted that psilocybin could potentially treat anxiety, addiction and obsessive-

compulsive disorder because of its mood-elevating properties. And other research has found that

psilocybin can reduce the fear response in mice

, signaling the drug's potential as a treatment for

PTSD.

Despite these positive findings, research on psychedelics is limited, and consuming magic

mushrooms

. People tripping on psilocybin can experience paranoia or a

complete loss of subjective self-identity, known as ego dissolution, according to Expert. Their

response to the hallucinogenic drug will also depend on their physical and psychological

environment. Magic mushrooms should be consumed with caution because the positive or negative

effect on the user can be "profound (and uncontrolled) and long lasting," Expert says. "We don't

really understand the mechanism behind the cognitive effect of psychedelics, and thus cannot 100

percent control the psychedelic experience."

*Correction: This article has been updated to clarify that Dr. Jordi Riba's work is supported by the

Beckley Foundation, not MAPS.

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

więcej podobnych podstron