Abstract

Cultural studies is a response to political crisis: it is the institutional

memory of failed revolutions. Can cultural studies move beyond memory

to action? This article describes the writer’s involvement in a non-pro t,

volunteer-run punk storefront in Toronto.

Keywords

cultural studies; anarchism; punk; gender

I

S I T P O S S I B L E

that cultural studies might do things? Or more exactly that

we in cultural studies might do things as well as teaching and writing?

1

What

would this mean and what could we do? In this article I characterize cultural

studies as the memory of failed revolutions. I don’t mean to be overly critical of

this, because keeping this memory is worthwhile. But what if cultural studies

moved beyond this? I think we would experience very rapidly the limits of what

can be done. Not just the lack of funding and skilled people but very real road-

blocks are put in our way. What we could do is quite limited. This sense of politi-

cal power as a force that makes things dif cult must then return to our work.

What we might learn from trying to do more are the real limits of cultural

studies.

Cultural studies as memory of failed revolution

Since the Second World War, cultural studies and critical thinking about culture

have expanded from a specialized interest to become a central concern. The topic

of culture is unavoidable in everyday life and political discussion. And the study

Alan O’Connor

WHOS EMMA AND THE LIMITS OF

CULTURAL STUDIES

Cultural Studies ISSN 0950-2386 print/ISSN 1466-4348 online © Taylor & Francis Ltd

n

Commentary

C U LT U R AL S T U D I E S 1 3 ( 4 ) 1 9 9 9 , 6 9 1 – 7 0 2

of culture in university centres has become a major growth industry in the

academy, in some cases incorporating material previously included in literature,

history, sociology, art, lm, media and women’s studies departments. We need

to think about the reasons for this academic success story. It may in fact serve to

divert us from serious and completely unresolved political problems that might

be better addressed directly.

The topic of culture seems to have emerged at moments in which there is a

crisis of democracy. Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy (1867/1969) was

written against the pressures of the working class in nineteenth-century England.

Demonstrating workers pulled down a fence surrounding a park. A panicked

Arnold saw art and philosophy as a kind of guarantee against the workers’

demands. All that is sweetness and light will preserve England from the anarchy

of the working class. A hundred years later, with the political demands of the

working class which fought in the war from 1938 to 1945 and pressures from the

emerging Third World for political independence, the theme of culture emerges

strongly again. It was this that Raymond Williams picked up on in his famous book

Culture and Society (1958/1963), but the theme of culture and identity is every-

where in the postwar period. It is there in Sartre’s Anti-Semite and Jew (1946/1965)

in which he puzzles about Jewish identity. It is there in quite a different way in

Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1963/1968), especially in his brilliant

chapter on national culture in a revolutionary African situation. The time frame

is different in Latin America, most of which gained its independence by the 1820s.

C U L T U R A L S T U D I E S

6 9 2

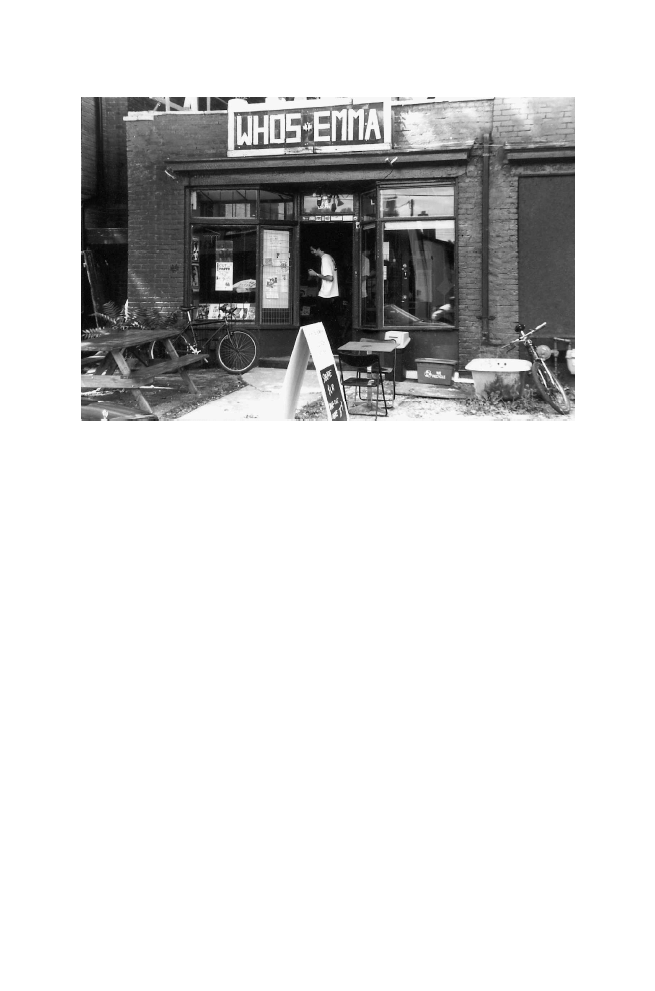

Plate 1 Whos Emma

Photo by Alan O’Connor

But we may note an important literature on national identity. In Mexico this

occurs especially after the blocked revolution of the 1910s. Octavio Paz’s The

Labyrinth of Solitude (1950/1985) is only the best-known work of a shelf of books

agonizing over questions of Mexican national character.

What we recognize easily as cultural studies, work written in the last thirty

years, the graduate research centre that grew into an academic industry, is equally

a product of revolution blocked. Cultural studies is clearly a product of the rela-

tive space won after the failed student-worker revolts of 1968. The political

system gave that much: space for a more relevant university curriculum. But the

bodies beaten by the police in Paris, the students demonstrating in London and

those murdered by the army in Mexico City in 1968 had fundamental democratic

demands that were mainly denied. It is the wholly ambivalent role of cultural

studies to keep alive in the academy the memory of failed revolution. Edward

Thompson put it best in his famous words at the beginning of The Making of the

English Working Class that ‘I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite

cropper, the “obsolete” hand-loom weaver, the “utopian” artisan, and even the

deluded followers of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of pos-

terity’ (1968: 13). To successfully write this memory is indeed a bitter reward.

Outside the university and in quite different parts of the globe, people remem-

ber in their own words and actions hopeless revolts and defeated revolutions.

Cultural studies as action

During the academic year of 1996 to 1997, instead of the usual round of uni-

versity classes and meetings, I helped open a storefront in downtown Toronto. It

was named ‘Whos Emma’ after the anarchist Emma Goldman who lived the last

years of her life on a nearby street. We wanted a name that made a reference to

Goldman who lived in this area in the 1930s when it was a working-class Jewish

neighbourhood. Most of the kids didn’t know who she was and often asked,

‘Who’s Emma Goldman?’ We left the apostrophe and question mark off at the

suggestion of the art student who had designed and made our store sign (from

rusted steel and used construction timber). The storefront was in part modelled

on San Francisco’s volunteer-run punk storefront called the Epicenter. There was

also a conscious relationship with the anarchist infoshop movement, which has a

stronger history in Europe than in North America. These are non-pro t coffee

shops, performance spaces and centres for information on events and political

issues. Whos Emma would have a relationship with Toronto anarchists, but its

foundation was in the contemporary punk scene.

2

The ambiguous relationship turned out to be one of the major issues as the

project developed. In cultural studies this is the theoretical question of the

relationship between culture and politics. It requires an analysis of the political

conjuncture. In Gramsci’s terms, are we in a period of a war of movement or a

L I M I T S O F C U L T U R A L S T U D I E S

6 9 3

war of position? Every analysis we have of the 1990s would say that this is not a

period of rapid revolutionary movement. In this case, Gramsci suggests the strat-

egy of a war of position: in this case not so much digging trenches as building an

oppositional culture.

3

Perhaps participants in Whos Emma would learn political

skills such as facilitating meetings as well as helping to strengthen radical culture

in Toronto. The relation between culture and politics is also the subject of

Bookchin’s (1995) polemic against lifestyle politics. He argues for a political

movement based on opposition to capitalism rather than one based on lifestyle

or subcultural activities. The sharp debate between Bookchin and his opponents

at the Fifth Estate and Anarchy magazines

4

has tended to assume the experience of

an older generation: it is mainly a debate about the generation of 1968. With the

experience of Whos Emma, I would say that Bookchin’s criticisms of lifestyle

politics have some validity. However, he and his critics have very little rsthand

knowledge of contemporary subcultures. The issue of the relation between cul-

tural activism and political organizing has also been debated with direct refer-

ence to autonomous spaces such as Whos Emma. Brad Sigel criticizes the North

American infoshop movement from a Love and Rage position that argues for a

more political strategy of a federation of anarchist collectives. The problems with

the infoshop strategy, he argues, include little participation from the local com-

munity, the dominance of punk-rock culture, the role of arts spaces and infos-

hops in inner-city gentri cation, poor internal dynamics between participants,

and above all the absence of clear goals. The problem according to Sigel is that

infoshops have no strategy for revolutionary social change.

The limits of what can be done

Trying to do something more than research and writing quickly reveals the real

effects of power and resistance to change. The rst set of issues has to do with

funding and starting the project. In fact, most projects stop here, never having

the funds to get going. Related to this is dealing with landlords, with city regu-

lations and legal matters. These issues can be dif cult, complex and cost money.

Is a landlord going to give a two-year commercial lease to 17-year-old punk kids

with a vague non-pro t project? A second set of issues has to do with organiz-

ation and personal disagreements. A new collective project can spend months of

agonizing meetings deciding on its structure, decision-making processes and

organization. Sometimes this can be easier if there are some shared understand-

ings, for example, about non-hierarchical structures. In the course of these pre-

liminary meetings personal con icts and disagreements are likely to arise. In

many cases these personal issues are dealt with very poorly. This is sometimes

due to a lack of understanding about what is happening and a lack of mediation

skills. Personal con icts can easily destroy a project even before it gets going and

can remain under the surface for years. A third set of issues has to do with the

C U L T U R A L S T U D I E S

6 9 4

purpose of the project. At the beginning the aims and goals are likely to be fairly

unde ned. People with many different backgrounds and interests arrive at poss-

ibly quite large meetings. It is impossible to satisfy everyone. As the project

becomes more de ned some people lose interest and fall away. Differences in

aims and goals can often be expressed as personal con icts: ‘you don’t respect

me.’ How these issues are handled will have important consequences for the

future of the whole project. So the limits are real: nances and dealing with legal

matters; creating an organizational culture in which people can work together;

and developing a collective project that of necessity excludes some people and

ideas.

Whos Emma

Meetings to plan the new project started in 1995 and it soon became clear that

people had very different projects in mind. Hardcore kids were looking for a

place to put on all-ages shows because there was no adequate venue in Toronto.

Others saw that as too limiting and wanted a performance space for different

types of music, including hip-hop. One person was interested in selling used

goods as a way of funding an informal performance space and art centre (perhaps

with facilities for pottery making). One person had experience of an anarchist

infoshop in Holland and had that in mind.

5

Another person was interested in

opening a vegan restaurant. One person insisted that the space should be fully

accessible for disabled participants. Some women wanted a feminist space,

perhaps for women only. Many young people came to meetings with a vague

sense of wanting to be part of something cool, without any clear idea of what

that might be. Without a place to meet, often without a facilitator for meetings

and with little shared sense of what the project might become, these meetings

ended in ‘personal’ disagreements that sometimes had consequences for years.

With the project dead, I spent the summer travelling through the USA and visit-

ing venues for shows, punk record stores and infoshops. Many useful ideas came

from this.

With the academic year 1996 to 1997 fast approaching, I decided to get the

project going and then let a collective form around it. This would eliminate the

agonizing meetings we had in 1995 and it would also exclude many of the pro-

jects. I found a small storefront for rent on a side-street in Kensington Market. At

the time it was a tattoo shop. Using my university salary I had no trouble secur-

ing a twelve-month lease. The store was tiny and I did most of the cleaning and

painting myself. With my high school woodworking skills, I made a counter, two

record/CD bins, a bookcase and a rack for zines. A plumber hooked up a small

bar sink and we were ready to serve coffee. With some dif culty I got a fridge on

loan from an iced-tea company so we had somewhere to keep juice and soymilk

cool. The store was so small that there was space for only one restaurant table and

L I M I T S O F C U L T U R A L S T U D I E S

6 9 5

two chairs, but I constructed a picnic table outside. In all it took about a month’s

work to set it up and it was a really nice break from working at the university.

The size of the space and the amount of money I had available eliminated

many of the 1995 possibilities. There was no space for a pottery wheel. Very

small shows might happen in the basement or occasionally outside the store, but

this could not really be a performance space. Setting up a restaurant was far too

expensive. The washroom was in the basement, down very inaccessible stairs

(but I made sure there was a comfortable chair for people to rest in). As a long-

time gay activist, I had lots of experience working with lesbian feminists, but this

was clearly not going to be a women-only space. For myself, I wanted it to be a

queer-positive space. The punk scene makes claims to being against homo-

phobia, but in practice offers little support to queer participants.

6

In the initial stages, Whos Emma drew on the resources of my roommates

and mainly suburban hardcore kids. Two people who did large ‘distros’ put large

amounts of records on consignment.

7

Many of the initial volunteers were friends

of friends. This had the result of associating the store with one speci c part of

the hardcore scene. However, other volunteers, some of whom eventually played

important roles, simply showed up at the store or at meetings and offered to help

out. The tensions between different parts of the punk scene, especially between

suburban Straight Edge kids, downtown ‘drunk’ punks, a small number of

anarchists, would play themselves out in the coming months.

8

Later there would

be tensions with the women’s collective. But for now, Whos Emma got off to a

surprisingly smooth start.

The day-to-day operation of Whos Emma was based on experience. Some

of this was from observing how other spaces were set up, some of it was from

how things are done within the DIY hardcore scene. I had done a distro at shows

for about a year before Whos Emma. And some of it was based on prior politi-

cal experience. With the traumatic meetings of 1995 in mind, I decided to use

common sense, consult with friends informally about each decision and then

later have things ratied or changed when Whos Emma had a functioning col-

lective structure. The store was so small that the layout of it was fairly obvious.

I copied the design of record bins from another record store. The store had

recently been painted purple and I didn’t change it. The volunteer structure was

based on my experience as a volunteer at The Body Politic in the mid-1980s. Each

volunteer would work one shift of four hours each week. There was no super-

vision. The hardcore scene works on an honour system. From the beginning

every volunteer was completely trusted with the cash and stock. People who

opened the store in the morning got keys. The schedule lled up quickly.

The idea was that people who wanted to get involved but didn’t have much

experience could start by doing a weekly shift. It took about half an hour to

explain everything from the light switches to the different sales tax on records

and books (though later we spent a lot of energy working on a comprehensive

training manual). Other roles needed more knowledge and experience. A

C U L T U R A L S T U D I E S

6 9 6

record-ordering committee quickly formed and also a book-ordering commit-

tee. To my delight I wasn’t needed on either. A nance committee would look

after bookkeeping, banking and nancial planning (I was always needed on this

committee). Other committees would develop as needed. The committees

would be accountable to the monthly general meeting.

The purpose of Whos Emma emerged in a practical way, without much dis-

cussion. We would sell underground records and tapes, some radical books and

zines. This was a direct continuation of distros that several of us were already

doing. We could have occasional small punk shows in the tiny basement. We were

already doing that at our house. We would organize workshops on skills that are

valued within the subculture: silk-screening T-shirts, doing sound for a live show,

putting on a punk show, bicycle repairs, vegan cooking, setting up a pirate radio

station and on political movements such as MOVE. We would provide a free

meeting space and encouragement for similarly minded groups such as Food Not

Bombs and eventually for Earth First.

9

All of this happened. After about a month

we had our rst potluck meal and collective meeting. It was so large we had to

have it outside the store, a huge circle of friends and volunteers. We had a trained

facilitator and an agenda that put practical matters up for discussion (hours of

operation, the four-hour volunteer schedule) but kept away from dif cult issues

of the political purpose and philosophy of Whos Emma.

10

Later these issues

would hit hard.

One of my university friends asked me what I wanted to get out of Whos

Emma. I wanted to try ‘informal education’ after several years of university

teaching. Could we learn the skills to work together and develop a cultural

project? Personally I wanted a break from the university. Making bookshelves and

looking after a hundred practical details was a relief from half a dozen years of

lectures and marking essays. I found Hakim Bey’s (1985) playful ideas about a

temporary autonomous zone liberating. This wasn’t like founding a political

party or a university. Even if Whos Emma collapsed after six months, I thought

it was still worth doing. Other people might pick up the idea and try again.

11

From the beginning I made it clear that my commitment was for one year. After

that it would have to stand on its own feet.

Consensus decision-making and the ght over major

labels

The day-to-day business was taking care of itself. People were surprisingly con-

scientious about doing their shifts. Those who started with more than one shift

came under pressure to forgo the extra ones and give other people a chance.

Doing a shift was fun. Record ordering was being done with energy. Interesting

books appeared on the shelves. Sales were adequate for paying the rent (but not

much else). An opening show with punk bands and a comedy troupe was held in

L I M I T S O F C U L T U R A L S T U D I E S

6 9 7

the street outside the store. It generated a lot of goodwill and helped mend some

bad feelings from the ill-fated meetings in 1995.

The first big fight came over major labels. This brought together at least

two fundamental issues: how we take decisions and the politics of the punk

scene. Take the first. My own experience as a political activist was one that took

the values of collectivity and consensus decision-making as givens. Collectivity

means involving everyone in decision-making, holding committees that take

decisions accountable to the larger group, rotating positions of responsibility

and sharing skills. The collective is also open in the sense that anyone can come

and join in. Consensus decision-making means not voting, but spending the

time to hear each person and working out agreements that satisfy everyone.

12

There are several preconditions for deciding by consensus: among them a

fundamental agreement on the project and the goodwill and honesty of every-

one involved. These are practical anarchist principles but I’d learned them from

the Toronto radical gay and lesbian movement of the early 1980s. How minori-

ties are treated in decision-making processes is a fundamental radical queer

issue.

The issue we were soon trying to decide at Whos Emma was this: what

records should we sell? There were two parts to this. Should we sell punk that

is released on major labels and should we not carry records that some people

found objectionable? The issue of a complete boycott of all music on major labels

was in part a response to the commercial interest in ‘grunge’ in the early 1990s

and the rediscovery of punk by the music industry. Maximum Rock ‘n’Roll zine took

a particularly hard line on this. From a slightly different point of view, avoiding

major labels is part of the hardcore DIY ethic.

13

One of the contradictions of this

position is that most hip-hop, jazz and protest music is on a major label. An argu-

ment made by some older participants was that 1977 generation punk is on major

labels. Newcomers were imposing their own political agenda on a scene that had

a more complicated history. Record ordering was done by an autonomous com-

mittee, mainly made up of people with a very extensive knowledge of punk and

hardcore bands. The issue came to the monthly general meeting. This was a rst

problem. In spite of assurances that this kind of accountability is normal, the

record-ordering group felt ‘targeted’ and vulnerable to criticism. The discussion

took several meetings. One helpful presentation explained that there were actu-

ally several categories of records.

1 Those on one of the major labels.

2 Those on fake indies that are 100 per cent owned by a major.

3 Indie labels that have press and distribute agreements with a major.

4 Underground labels that are self-distributed, or represented by an indepen-

dent distribution organization such as Mordam.

In addition, a royalty of a few cents is paid on every CD to the multinational cor-

poration that holds the rights to that format. The discussion was wide-ranging.

C U L T U R A L S T U D I E S

6 9 8

Some people wanted to know why big corporations were so bad anyhow. An

anti-capitalist politics could not be assumed. Some people with extensive

musical knowledge wanted us to be a ‘proper’ music store. People weren’t born

punks. We shouldn’t be elitist towards the kid who comes in looking for the

new Green Day CD. Perhaps to survive economically we needed to be a ‘one

stop’ store where you could get what you were looking for. Someone did

research into what we were actually selling and found out that many important

bands fall into the third category, so that’s where we drew the line. Major labels

and fake indies were out. Bands with press and distribute agreements were

reluctantly accepted. Any exceptions (for example, for a bene t record) would

be brought to the monthly collective meeting. At least we decided.

Punk and gender politics: no consensus possible

Punk is a very boy-dominated and heterosexual scene.

14

I realized from the start

that we would have to take steps to try to make Whos Emma a woman-positive

space. So from the very beginning we had:

1 Women’s records – in a section labelled ‘Grrls Kick Ass’ and displayed on the

walls.

2 Feminist books.

3 Posters of women’s events on the walls.

4 Monday was women’s day, right from the very rst week. We borrowed the

idea from the Epicenter of having no male volunteers that day. I usually kept

away from the store on Mondays.

5 One of our rst workshops was for women only. It was given by a woman

sound person on how to run sound at a club. There was some protest at this

‘discrimination’ especially from younger male volunteers who wanted to do

the workshop too. (We repeated it as a mixed gender workshop about a

month later.)

6 The facilitators for the general monthly meetings were alternated so that

every second collective meeting was facilitated by a woman.

7 Women were informally encouraged to participate fully, for example, to take

volunteer shifts and positions of responsibility.

For me, this wasn’t a matter for discussion. After all, the place was named for

Emma Goldman. The response from male participants varied. Some were in

support, others didn’t see the need. I was willing to talk to people about this but

not willing to sit through a collective meeting in which basic feminist positions

had to be defended.

The issue over records arose over some Straight Edge bands whose vegan

and animal rights positions extended into anti-abortion politics. We were selling

bands that were exactly this.

15

A related issue was that some records and CDs

L I M I T S O F C U L T U R A L S T U D I E S

6 9 9

had covers that some women found offensive, or had lyrics that were offensive.

This was a much more dif cult discussion than the decision about major labels.

Arguments were made about censorship and where you draw the line. Who

decides what’s offensive? What if someone objected to Pansy Division’s explicit

gay imagery and lyrics? The record-ordering committee felt even more targeted.

They explained that they ordered records from lists and often had no way of

knowing what the record cover would be like. They couldn’t be expected to

know the lyrics of all bands. That was easy to accept. What was more dif cult

was why we were selling Straight Edge bands that everybody knows to be anti-

abortion. On this general issue we reached some understandings of each other’s

positions but were unable to reach consensus. We simply couldn’t decide. Even

when some key people resigned (and they were an important loss) we still would

not have been able to reach consensus on this issue.

The limits of cultural activism

The months ew by and soon my sabbatical year was over. By then Whos Emma

was long functioning under its own dynamic. We even had our own monthly

radio show. Back at work, I would gradually reduce my involvement until I nally

left. It was an engrossing experience and I felt sad to leave it behind. What came

from all this energy and unpaid work from so many people? Those most critical

of the project say it has no clear objectives and is a distraction from real politi-

cal organizing. They are in part right. Whos Emma is tied to punk subculture: it

is neither anarchist nor socialist. It’s a ‘cool’ place but that does not necessarily

extend to a clear anti-capitalist politics. And its politics about gender are com-

pletely unresolved. To say that it is counter-hegemonic or that it represents poli-

tics through culture does not really say much. But even to get this far was a

struggle against a world that imposes limits and exerts so many pressures to

destroy an alternative such as this. We were limited in resources, in experience

and skills: above all in the personal and political skills needed to get further than

we did. We started something and we grew. Yet the doubts remain. Is this also

the memory of failed revolution?

Notes

1

Activist-oriented research in Germany is discussed in McRobbie (1982). More

recently see McKay (1998), O’Hara (1995), and Duncombe (1997).

2

For another account of Whos Emma see Munroe (1997).

3

Forgacs’ (1988) very useful edited collection of Gramsci is unfortunately out

of print.

4

This debate took place in the anarchist press but see Watson (1996).

C U L T U R A L S T U D I E S

7 0 0

5

On the Dutch squatters’ movement see ADILKO (1990/1994). A free associ-

ation of authors and researchers, ADILKO (The Foundation for the Advance-

ment of Illegal Knowledge) was established in Amsterdam in 1983.

6

In fact, a planned queer night at Whos Emma never really got off the ground,

though the storefront has usually had a number of queer participants, some-

times playing key roles. Gay punks were involved in establishing ABC NO-RIO

in New York as a hardcore venue (Mike Bullshit), at the Gilman Street space

in San Francisco (Tom Jennings), and in the Profane Existence collective in Min-

neapolis (Dan).

7

A ‘distro’ involves the sale of records and zines at show and through mail order.

It is sometimes a source of income and is sometimes combined with a small

self-produced record label.

8

For differences in the contemporary punk scene see O’Hara (1995), Profane

Existence Collective (1997), Lahickey (1997), DuBrul (1997), Leblanc

(1999).

9

Butler and McHenry (1992), DAM Collective (1997).

10

In fact there was a big debate at the rst meeting about having a Snapple fridge.

For some people it was too commercial: they wanted to make our own iced

tea. Other objections were based on rumours about the company, which were

quite widespread at the time in underground culture. Making our own iced

tea was not practical and would probably contravene health regulations. The

Quaker Oats corporation, which had purchased Snapple, supplied us with

detailed refutations of the rumours. This issue would resurface from time to

time.

11

The existence of Whos Emma did seem to encourage people in Toronto and

elsewhere with similar ideas. However, it should be noted that several very

active and committed volunteers were also looking for experience to set up

their own small businesses (restaurants, record stores).

12

On consensus decision-making see Kaner (1996).

13

Much of this debate took place in zines, but see Albini (1997).

14

Leblanc (1999), especially ch. 4.

15

It later turned out that some of these records were ordered by a young woman

punk (not Straight Edge) who took the position that some types of feminism

are authoritarian. Or put more simply, she liked the music and ordered the

records to annoy people. For a good introduction to Straight Edge see Lahickey

(1997).

References

ADILKO (1994) Cracking the Movement: Squatting Beyond the Media, trans. Laura

Martz, New York: Autonomedia. (Originally published in 1990.)

Albini, Steve (1997) ‘The problem with music’, in Thomas Frank and Matt Weiland

(eds) Commodify Your Dissent: Slavos from The Baf er, New York and London:

Norton.

L I M I T S O F C U L T U R A L S T U D I E S

7 0 1

Arnold, Matthew (1969) Culture and Anarchy, Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press. (Originally published 1867.)

Bey, Hakim (1985) T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic

Terrorism, New York: Autonomedia.

Bookchin, Murray (1995) Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable

Chasm, San Francisco, CA: AK Press.

Butler, C. T. Lawrence and McHenry, Keith (1992) Food Not Bombs: How to Feed the

Hungry and Build Community, Philadelphia, PA: New Society Publishers.

DAM Collective (1997) Earth First! Direct Action Manual, Eugene: SWEF!

DuBrul, Sasha Altman (1997) Carnival of Chaos: On the Road with the Nomadic Festival,

New York: Autonomedia/Bloodlink.

Duncombe, Stephen (1997) Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative

Culture, London and New York: Verso.

Fanon, Frantz (1968) The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington, New

York: Grove Press. (Originally published 1963.)

Gramsci, Antonio (1988) An Antonio Gramsci Reader:Selected Writings 1916–1935, ed.

David Forgacs, New York: Schocken.

Kaner, Sam (1996) Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making, Philadelphia, PA:

New Society Press.

Lahickey, Beth (1997) All Ages: Re ections on Straight Edge, Huntington Beach: Revel-

ation Books.

Leblanc, Lauraine (1999) Pretty in Punk: Girls’ Resistance in a Boys’ Subculture, New

Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

McKay, George (ed.) (1998) DiY Culture: Party and Protest in Nineties Britain, London

and New York: Verso.

McRobbie, Angela (1982) ‘The politics of feminist research: between text, talk and

action’, Feminist Review, 12: 46–57.

Munroe, Jim (1997) ‘Who’s Emma?’, Punk Planet, July/August: 102–5.

O’Hara, Craig (1995) The Philosophy of Punk:More than Noise!, San Francisco, CA: AK

Press.

Paz, Octavio (1985) The Labyrinth of Solitude, trans. L. Kemp, Y. Miles and R. P.

Beldash, New York: Grove (Originally published 1950.)

Profane Existence Collective (ed.) (1997) Making Punk a Threat Again! The Best Cuts

1989–1993, Minneapolis: Profane Existence.

Sartre, J. P. (1965) Anti-Semite and Jew, trans. George J. Becker, New York: Schocken.

(Originally published 1946.)

Sigal, Brad (n.d.) ‘Demise of the beehive collective: infoshops ain’t the revolution’,

online at ‘Directory of Infoshops’ at Mid-Atlantic Infoshop,

Thompson, E. P. (1968) The Making of the English Working Class, Harmondsworth:

Penguin. (Originally published 1963.)

Watson, David (1996) Beyond Bookchin: Preface for a Future Social Ecology, New York:

Autonomedia.

Williams, Raymond (1963) Culture and Society: 1780–1950, Harmondsworth:

Penguin. (Originally published 1958.)

C U L T U R A L S T U D I E S

7 0 2

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

In the Wake of Cultural Studies Globalization,Theory and the University Rajan, Tilottama

Classical Translation and the Location of Cultural Authority

Wanner, Cunning Intelligence in Norse Myth Loki Odinn and the Limits of Sovereignty

Massimo Berruti The Unnameable in Lovecraft and the Limits of Rationality

Angela McRobbie The Uses of Cultural Studies A Textbook

witchcraft and the limits of interpretations

The Appeal of Exterminating Others ; German Workers and the Limits of Resistance

Bourdieu, The Sociology Of Culture And Cultural Studies A Critique Mary S Mander

Stuart Hall s Cultural Studies and the Problem of Hegemony Brennon Wood

ebooksclub org Dickens and the Daughter of the House Cambridge Studies in Nineteenth Century Literat

Barnett Culture geography and the arts of government

034 Doctor Who and the Image of the Fendahl

030 Doctor Who and the Hand of Fear

035 Doctor Who and the Invasion of Time

Dr Who Target 043 Dr Who and the Monster of Peladon # Terrance Dicks

Dr Who Target 035 Dr Who and the Invasion of Time # Terrance Dicks

Dr Who Target 007 Dr Who and the Brain of Morbius # Terrance Dicks

025 Doctor Who and the Face of Evil

więcej podobnych podstron