RUTH CHARLES

THE EXPLOITATION OF CARNIVORES AND OTHER FUR-

BEARING MAMMALS DURING THE NORTH-WESTERN

EUROPEAN LATE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC AND MESOLITHIC

Summary.

The exploitation of large mammals, particularly large herbi-

vores, has dominated perceptions of Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic

subsistence behaviour in north-western Europe. This paper critically reviews

the evidence for the exploitation of a complementary resource which has

received little attention within the archaeological literature — carnivores and

other fur-bearing mammals. Evidence for exploitation of individual species is

described and discussed. A model is then developed to explain the apparent

expansion of the subsistence base to include a wide range of fur-bearing

mammals during the Lateglacial and Mesolithic. This paper concludes by

arguing that although the use of carnivore meat and pelts cannot be viewed as

a dominant trend in European hunter-gatherer subsistence practices, their

contribution to hunter-gatherer economies cannot be ignored.

The reconstruction of European Palaeo-

lithic and Mesolithic economic activities has

been a primary concern of researchers over

the last 150 years. Relatively little attention

has been paid to evidence for the exploitation

of carnivores and other fur-bearing mammals,

especially those which do not normally form a

part of modern western European dietary

practices. However, detailed examination of

faunal assemblages from a series of Late

Upper Palaeolithic and early Mesolithic sites

in north-western Europe indicates that such

mammals were exploited both for their meat

and pelts. The material discussed here origi-

nates from archaeological sites dating to the

Lateglacial and early Postglacial and asso-

ciated with Creswellian, Magdalenian, Ma-

glemosian

and

Ertebølle

archaeological

residues (Fig. 1). In most cases the sites

discussed are those currently under review by

the author (Gough’s Cave, the Robin Hood

Cave, Trou de Chaleux, Trou des Nutons,

Trou du Frontal, Grotte de Sy Verlaine, Grotte

du Cole´opte`re, and Star Carr), although

additional examples have been drawn from

the published literature. In the former in-

stances faunal assemblages have been exam-

ined with the specific objective of identifying

direct evidence for the human exploitation of

animals via the evidence of butchery marks on

bones.

Recent research on the Danish Mesolithic,

particularly the Ertebølle, has led the way in

documenting the exploitation of such mam-

mals (Rowley-Conwy 1980 & in press;

Trolle-Lassen 1986 & 1987). The exploitation

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY 16(3) 1997

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997, 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK

and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

253

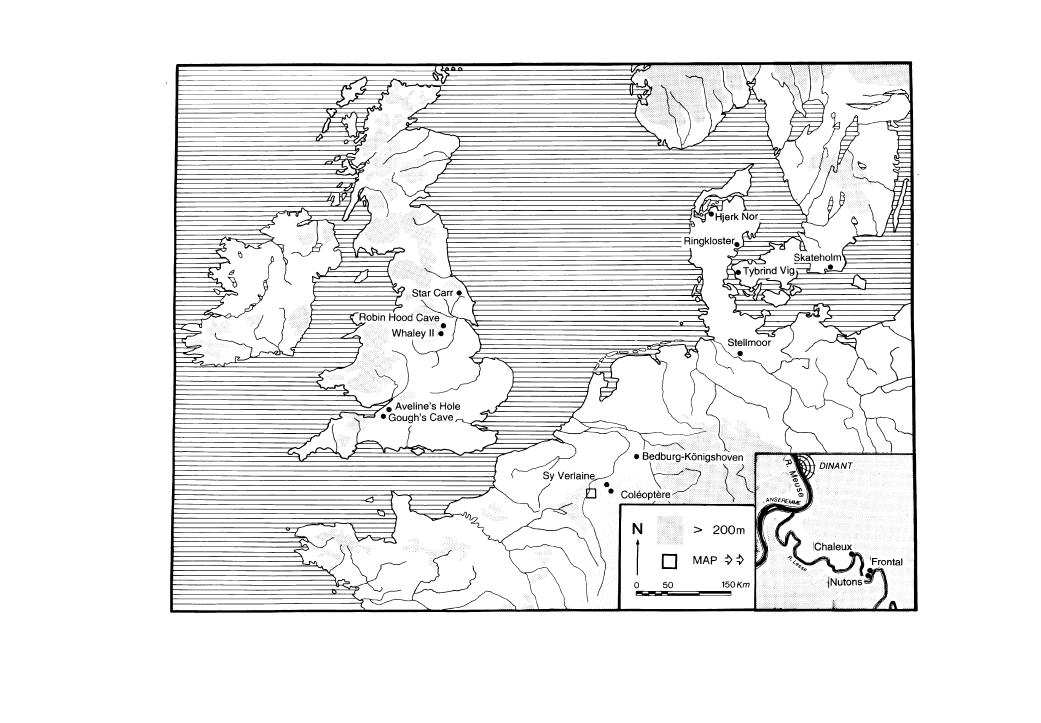

Figure 1

Location map of sites discussed within the text.

THE

EXPLOITATION

OF

CARNIVORES

AND

OTHER

FUR-BEARING

MAMMALS

OXFORD

JOURNAL

OF

ARCHAEOLOGY

254

ß

Blackwell

Publishers

Ltd.

1997

of one particular fur-bearing species (Lepus

timidus) has also been reported during the

British Lateglacial (Charles & Jacobi 1994).

Recent work indicates that the small scale

exploitation of such mammals was more

widespread during the Late Upper Palaeo-

lithic and early Mesolithic. However, in most

of the assemblages discussed here there is

also abundant evidence for the human ex-

ploitation of a number of ungulate species

which formed the primary subsistence base at

these sites, and which have dominated

perceptions of the hunting/trapping activities

which took place.

In contemporary western European society

carnivores are rarely, if ever, viewed as a

potential food source, and only a limited

range of fur-bearing mammals are exploited

for their pelts. However, there is no reason

why these preferences should be reflected in

the European prehistoric archaeological re-

cord. Indeed, the review that follows demon-

strates that whilst a range of carnivore

species may not have been a regular dietary

staple, they were on occasion exploited both

for their meat and pelts. Modern poachers

and countrymen questioned in the Oxford

region suggested that carnivore meat is

avoided today because it ‘tastes bad’, how-

ever, none of these informants had actually

tried carnivore meat, believing the nature of

the prohibition to be self evident. Contem-

porary non-European societies rarely main-

tain dietary taboos similar to those prevalent

in Europe, and the use of dogs, cats and a

variety of rodents as food can be documented

in many parts of the world. Similarly a

variety of rodents and other mammals rarely

considered edible by modern Europeans were

enjoyed by both ancient Romans and Greeks.

Grahame Clark’s seminal volume Prehis-

toric Europe: the economic basis (1952) first

drew to prominence the potential contribu-

tion of small game animals to Palaeolithic

and Mesolithic communities. However, there

are relatively few detailed discussions of the

archaeological evidence for this activity.

What follows is a review of the evidence

for the exploitation of a variety of carnivores

and fur-bearing mammals from the Late

Upper Palaeolithic and early Mesolithic of

north-western Europe (used here to mean

Britain, Benelux, Germany and southern

Scandinavia). Each species will be dealt with

individually and the nature of the evidence

discussed in detail.

URSIDAE

Brown bear (Ursus arctos)

In general, it is uncommon to find cut-

marked bear bones from Late Upper Palaeo-

lithic and early Mesolithic contexts, although

bears are frequently present in faunal assem-

blages. It is usually assumed that these

predators were denning in caves at times

when humans were absent. There are few

convincing accounts of the human exploita-

tion of bears in the archaeological literature.

Suggestions that Middle Palaeolithic sites

such as Ista´llo´sko¨ and Szeleta belonged to a

‘cave bear cult’ in south-eastern Europe are

dubious. Instead it seems probable that the

bear remains found in these caves came from

animals which died naturally during hiberna-

tion and that bears were the main residents of

these sites for much of Middle Palaeolithic

time (Allsworth-Jones, 1986) rather than

there being any direct link with humans.

Re-examination of such ‘cave-bear cult’

faunas for direct butchery evidence may

prove to be a useful path for future research,

offering an approach which could demon-

strate whether humans had contributed in any

way to the accumulation of these bear

remains.

The paucity of clear evidence of bear

RUTH CHARLES

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

255

exploitation

during

the

Pleistocene

and

Holocene may be explained by bears’

tendency to avoid direct contact with hu-

mans, unless they pose a threat, and their

choice of dens in relatively secluded areas.

The hunting of bears is a highly dangerous

pastime, even with modern guns and rifles.

Modern weapons have to be of a large

calibre, and often a number of shots are

necessary to kill an adult (Nelson 1973, 122–

124; Domico 1988, 170), a luxury rarely

available whilst being charged by a bear. The

use of snares as a means of trapping bears has

been documented by Nelson (1973, 116–

117), as have a range of techniques for

hunting bears in their dens. Almost all

require the use of projectiles, and it is

assumed that Late Pleistocene and early

Holocene bear exploitation

would have

involved the use of an efficient projectile

technology and/or the opportunity to take

bears by surprise either via traps or when

found hibernating.

Brown bears are present in the Late

Magdalenian faunas from the Trou de

Chaleux (Hulsonniaux), the Trou du Nutons

(Furfooz), the Trou du Frontal (Furfooz) and

the Grotte de Sy Verlaine (Hamoir) in

Belgium. They are also present in the

Creswellian-associated faunas from Gough’s

Cave (Cheddar) and the Robin Hood Cave

(Creswell) in Britain. Of these, the only

specimens which can be directly linked to

human activity are those recovered from the

Trou de Chaleux in Belgium.

The number of identifiable specimens

present (NISP) count for bear at Chaleux is

relatively low (65; 1.78% of the overall

assemblage; full details of assemblage com-

position are given in Charles 1994), and the

body part representation data indicates that

only selected parts of three bear carcasses

were recovered. The remains of at least two

adults and one juvenile were present. In the

case of the juvenile only 3 metapodia with

unfused proximal epiphyses were recognised,

suggesting the presence of an isolated paw

rather than an entire skeleton. Both adult

bears are represented by parts of the skull

(mandibles, a maxilla and loose teeth), three

vertebrae, an innominate, sacrum, part of the

forelimb, the lower portion of the hind limb

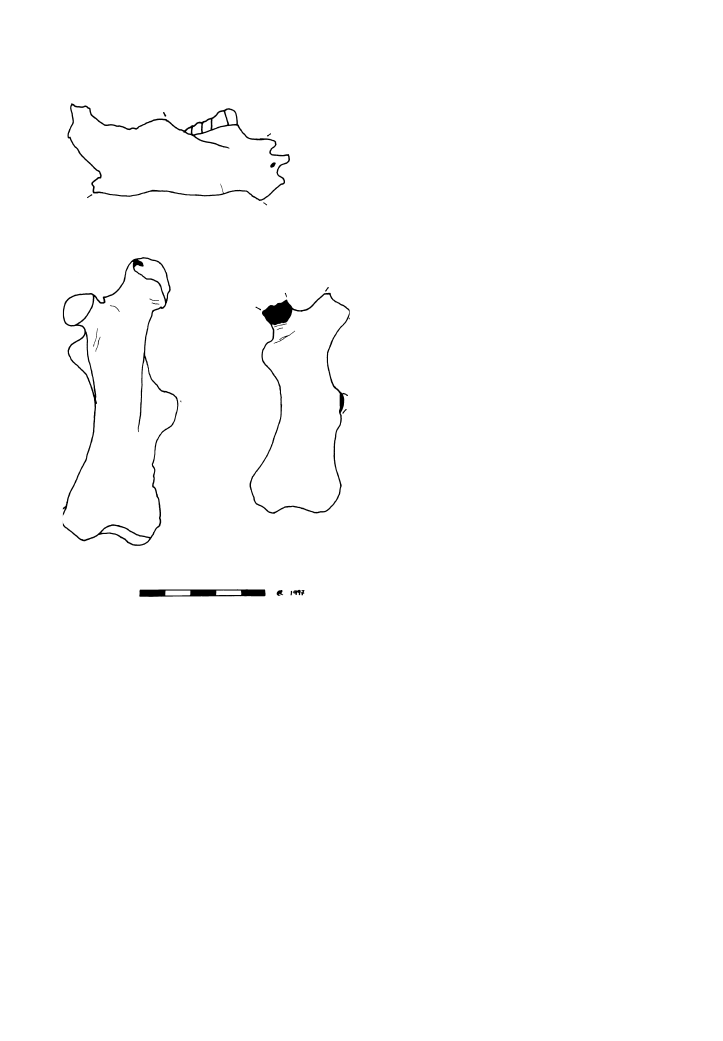

and the phalanges. Butchery marks were

observed on the bones of at least two of the

three individuals (an adult and the juvenile;

Fig. 2). With the exception of a left mandible,

all the butchery marks were confined to the

paws and for the most part correspond with

skinning, although marks across two tarsals

and three phalanges are indicative of dis-

articulation. Amongst these are three meta-

tarsals belonging to the adult (all cut) which

were originally part of the same paw.

Brown bear dens are usually selected for

their remoteness from centres of human

population, and may be in long-term use by

successive generations of bears. Depending

on environmental conditions, bears will begin

hibernation between September and early

November and continue until the April of the

following year. Cubs may den with their

mothers for up to two winters and this may

well be the situation with at least one adult

and the juvenile from Chaleux. Consequently

the taking of the two bears from Chaleux

could indicate autumn or winter seasonality

for this particular ‘event’ at the site. Before

hibernation commences, bears lay down an

large amount of fat to see them through the

winter months. Both Domico (1988) and

Partridge (1992) give the figure of 90 lb

(41 kg) as an upper limit for food consump-

tion within a 24 hour period. Nelson’s

account of the north American Kutchin

Indians (1973, 115–116) noted that there

were only certain periods of the year during

which these animals were considered ‘fit’ for

eating, primarily when they had large fat

THE EXPLOITATION OF CARNIVORES AND OTHER FUR-BEARING MAMMALS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

256

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

reserves (autumn and early winter), although

they were taken during other parts of the year

for their skins. From a human perspective,

bears have many uses. Their fat may well

have been a valuable resource for the human

residents of the cave. Their skins are tough

and hard wearing, and their stored fat is

known to make good fuel for lamps, has a

high calorific value and may also be

extremely useful in the waterproofing of

skins. Coles (1991, 136) notes that bear

grease was a good adhesive agent for the

pigments used in prehistoric art (although

there is no evidence for cave painting at

Chaleux or any of the Belgian caves). Their

hides are at their best between the autumn

and spring, and have been observed being

used for mattresses and for insulation among

contemporary north American Indians (Nel-

son 1973, 127).

Evidence for the Mesolithic exploitation of

brown bears is equally rare, but does exist. At

Medvedia Cave near Ruzı´n in Slovakia, the

skeletal remains of at least one bear were

found associated with composite arrowheads

(bone points with imbedded microliths, Ba´rta

1989). For the time being, the bears from

Chaleux and Medvedia Cave remain the only

unambiguous examples of the Late Pleisto-

cene and early Holocene human exploitation

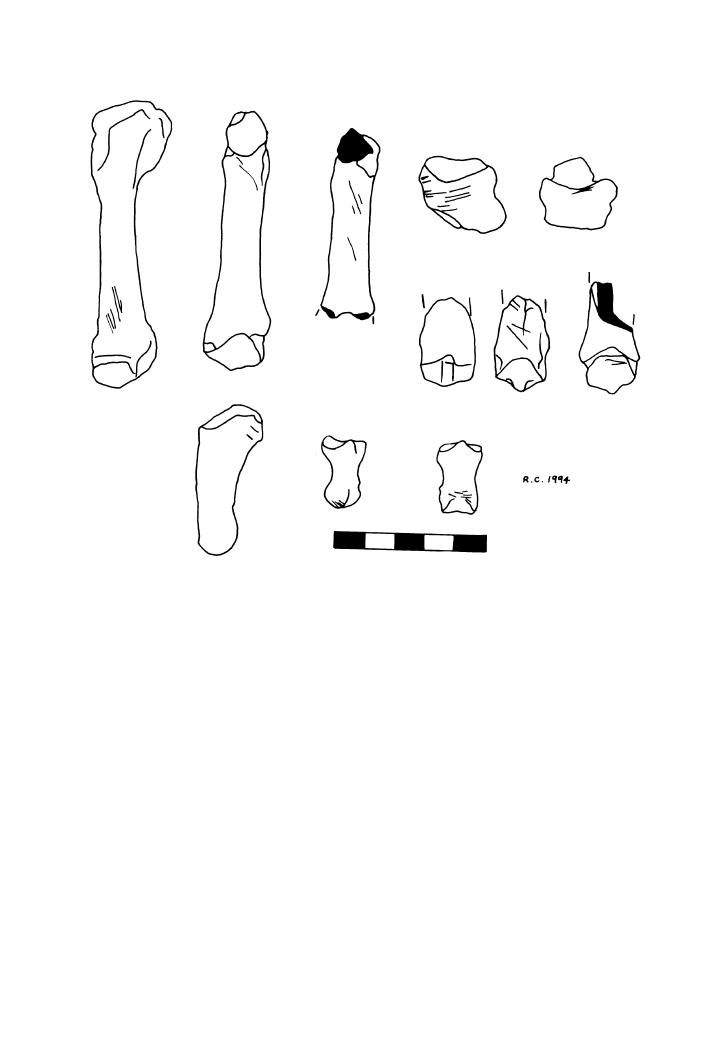

Figure 2

Cut-marked bear bones from the Trou de Chaleux.

RUTH CHARLES

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

257

of brown bear.

CANIDAE

Wolf (Canis lupus) and dog (Canis familiaris)

Wolves are the largest wild canids, weigh-

ing between 16 and 60 kg. They have been

known to live for up to 13 years and have a

well defined mating season between January

and April. Originally the wolf had one of the

widest distributions of any known mammal,

being distributed throughout the northern

hemisphere north of 15º lattitude. Their

habitat tolerance is extremely variable, po-

pulation densities being proportional to those

of their prey. Generally they live in family

groups (packs) with complex social organisa-

tion (Mech 1970), pack size is also variable,

upper limits being 30 individual although

groups of eight to twelve are more common

(Ginsberg & MacDonald 1990). Flexibility

appears to be the main aspects of wolf

behaviour, and this is reflected in their diets,

which focus on large ungulates when avail-

able, but will also include carrion, smaller

prey and rubbish discarded by humans.

Wolf and/or dog remains have been

recorded at many of the sites under discus-

sion here. Canids were recovered from the

Lateglacial layers at the Trou de Chaleux,

Trou des Nutons, Trou du Frontal, Grotte de

Sy Verlaine, Gough’s Cave and the Robin

Hood Cave; the domestic dog from Star Carr

is well known in the literature (Degerbøl

1961). Although the presence of semi-feral

dogs during the northern European Upper

Palaeolithic has been suggested by Benecke

(1987), this has yet to be demonstrated at any

of the Lateglacial sites listed here, and all

canids recovered from the Pleistocene layers

at these sites are identified as Canis lupus. At

both the Trou des Nutons in Belgium and

Gough’s Cave in Britain cut-marks are

present on the wolf remains.

The actual number of specimens showing

butchery evidence is low. A single distal

humerus from the Trou des Nutons shows

multiple parallel cuts along the medial aspect

of the distal end and shaft which correspond

with both meat removal and disarticulation.

The only cut specimens from Gough’s Cave

are two phalanges (Natural History Museum

Acc. No. M.13796), with transverse cuts

present across the palmate surfaces, relating

to skinning. A further example is given by

Rowley-Conwy (in press) from Ringkloster,

where four dog crania were recovered

showing cut marks relating to skinning. In

the cases of Gough’s Cave and Ringkloster it

is clear that the animals in question were

processed for their pelts, and certainly for

their meat at the Trou des Nutons. Addition-

ally, canids are present within the assem-

blages from Sy Verlaine (Minimum Number

of Individuals = one), the Trou du Frontal

(MNI = three) and the Trou de Chaleux (MNI

= two). None of these latter specimens was

cut, and the possibility that they represent

‘natural deaths’ within the cave cannot be

excluded.

Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and arctic fox

(Alopex lagopus)

It is often unclear whether one or two

species of fox are present in European Late

Pleistocene faunal assemblages, although the

red fox (Vulpes vulpes) is usually assumed to

be the only fox present in early Holocene

ones. Clutton-Brock et al. (1976) identified

various point of difference between different

members of the Canidae, but few of these are

applicable to post-cranial elements or in-

complete crania. In general, modern arctic

foxes are smaller than red foxes, one of the

most distinctive differences being that their

muzzles are relatively shorter and broader

THE EXPLOITATION OF CARNIVORES AND OTHER FUR-BEARING MAMMALS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

258

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

than their red counterparts. It is possible to

differentiate these two species osteologically,

but this is only possible on certain anatomical

elements, and requires them to be complete.

One of the main points of differentiation is

within the dental arcade; however, this is

rarely complete in Pleistocene specimens.

Both red and arctic foxes live in dens with

complex burrow systems (Ginsberg & Mac-

Donald 1990). These are used primarily for

shelter and rearing young. In the case of

arctic foxes there is evidence to suggest that

these dens may be in long term use by

succeeding generations. The average life

span of a fox is a few years (11 is given as

a maximum: op. cit., 34), although a den may

be in continual use for up to 300 years.

The arctic fox (Alopex lagopus) occurs in

two colour morphs (‘white’ and ‘blue’),

which change seasonally. Its habitat is today

limited to circumpolar regions, especially

arctic tundra. It is an opportunistic scavenger

and predator, and has been known to

scavenge meat from seal carcasses (op. cit.,

34) and to take seabird eggs.

The colouring of the red fox is quite

variable but not seasonal. Animals have been

observed to have pelts in a range of shades

from grey to bright red, although the most

common is reddish-brown. Red foxes are

distributed throughout the northern hemi-

sphere and much of southern Australia. Their

natural habitat is a dry, mixed landscape,

although they are also found in uplands,

mountains, deserts and sand dunes. In short,

they are a highly flexible and adaptable

species. Their diet is varied, including

beetles, earthworms, small mammals (includ-

ing lagomorphs), birds, fruit and carrion.

They are often blamed for the death of

juvenile livestock (e.g. lambs), although it is

unclear whether they actively hunt these or

taken them as carrion. They are also known

to cache food surpluses (Ginsberg & Mac-

Donald 1990).

Both species of fox are currently trapped

for their pelts in various parts of the world.

The trapping of arctic foxes for their pelts is a

relatively well documented activity during

the Upper Palaeolithic of other regions (cf.

Klein 1973, 56). The evidence from the

Russian sites of Mezin and Avdeevo, consists

of virtually complete fox skeletons (exclud-

ing paws), which Klein suggests were

removed with the skins.

The skinning of animals leaves very few

traces in the archaeological record. Cut

marks may be present at key points of

severance — in the region of the snout, and

perhaps on the lower limbs, where the skin

has been ‘ringed’ to remove it from the body.

The precise location of both points of

severance will vary. This variation may relate

to a wide range of factors, including the

particular butchery ‘tradition’ and techniques

involved, as well as personal ‘style’ on the

part of the butcher/furrier. This being the

case, the recognition of human exploitation

of foxes solely for their pelts via butchery

evidence is likely to be rare — and greater

credence is often placed on body part

representation

information

when

sample

sizes are adequate. However, this does not

preclude the presence of direct butchery

evidence, and where this exists it can only

add credibility to arguments for the exploita-

tion of these fur bearing mammals.

Such evidence is present at many of the

sites under discussion here (the Trou de

Chaleux, Trou des Nutons, the Trou du

Frontal and Star Carr); although only the

Trou de Chaleux yielded sufficiently high

numbers of fox remains to make body part

representation analyses a worthwhile exer-

cise. It is tempting to argue that the fox

remains found at the other sites (the Grotte

du Cole´opte`re, the Grotte de Sy Verlaine,

Gough’s Cave and the Robin Hood Cave)

RUTH CHARLES

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

259

were also present due to human agency.

However, there is no direct evidence for this,

and in each case the NISP counts for Vulpes

sp. were so low that the remains could easily

be accounted for by one or two individuals

denning in the caves at a later date.

At Chaleux, the foxes were the second

most abundant species (NISP = 473, 12.93%

of the assemblage). Consequently their po-

tential significance within the local Lategla-

cial hunting/trapping economy should not be

underestimated. Of the five fox bones with

butchery marks, one — a left scapula — is

clearly very recent in origin. The remaining

four specimens (two femora, a humerus and a

scapula) show longitudinal marks consistent

with meat removal. It is difficult to establish

whether more (or, indeed all) the foxes at

Chaleux were present due solely to human

agency, or to the actions of several predators

of which humans were just one. As the fox

bones lack any spatial information (as indeed

does all the faunal material from Chaleux)

and the excavator, E

´ douard Dupont, made no

detailed comment on them, it is impossible to

know whether the fox bones were encoun-

tered as disarticulated elements, in articulated

units or as complete skeletons.

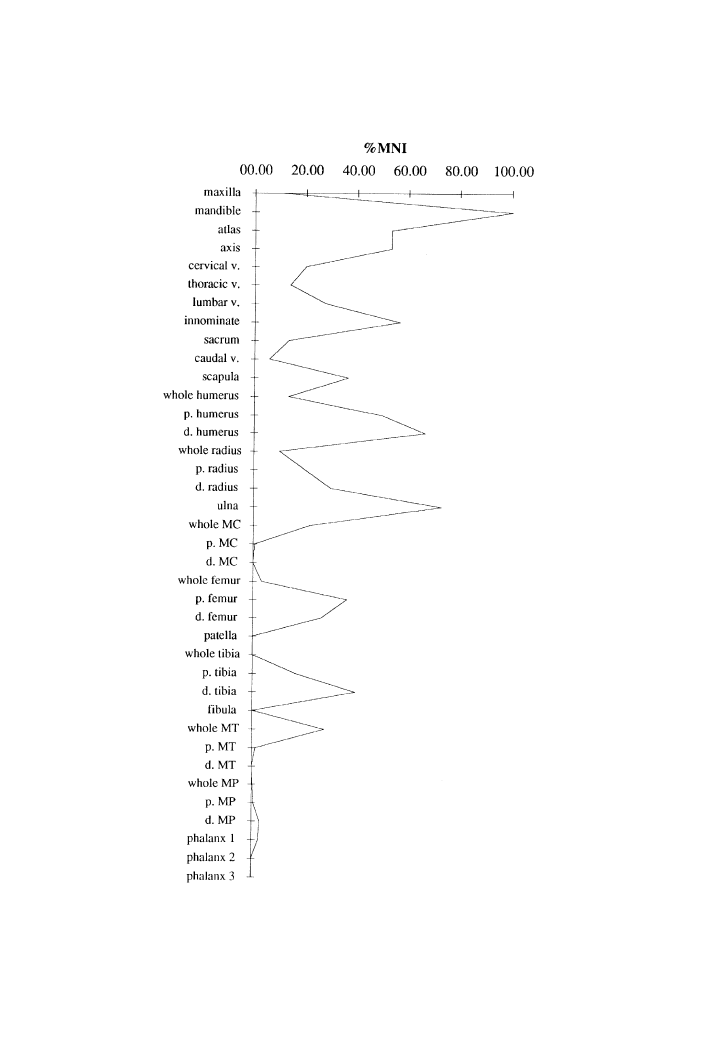

An MNI count of 17 was obtained from the

mandibles. Examination of body-part repre-

sentation (Table 1) does not give a clear

indication as to whether complete or almost

complete carcasses were present at the site.

No juvenile bones were recorded and,

although this may indicate that the cave

may not have been a den, this possibility

cannot be fully eliminated. It is interesting

that the first cervical vertebrae (atlas and

axis) are present in identical numbers (eight),

although the % MNI figures for the other

vertebrae are much reduced. Complete long

bones are relatively rare, although they are

present. Proximal and distal ends occur in

significantly different quantities, although

this seems to be linked more with their

relative robustness than with human selection

of different body parts. Fibulae are totally

absent which, given the fragile nature of this

bone, may again be taken as an indication

that bones were fragmented beyond recogni-

tion (or recovery) whilst buried.

Of perhaps greatest note is the relative lack

of metapodia and phalanges. The metapodia

occur only in very low frequencies, as do the

1st phalanges, whilst the 2nd and 3rd are

totally absent. There are three possible

explanations for this: first, that these ele-

ments were not recovered on site due to poor

excavation techniques; second, that these

elements were not identified after recovery;

and finally that they were not originally

present at the site. The first two possibilities

do not seem to be particularly likely and as

recovery from this excavation appear to have

been excellent (Charles 1994), it is assumed

here that the BPR information is a reflection

of what was originally present at the site

rather than a distortion caused by poor

recovery techniques.

Klein’s (1973) account of skinned foxes

from Russian sites seems to hint at the fate of

at least some of the Chaleux foxes. Like their

Russian counterparts, the Chaleux foxes have

lost their paws, a fact highly suggestive of

skinning. Animal remains from Chaleux are

present in high numbers, and the occurrence

of the smaller anatomical elements of most

species in relatively high proportions indi-

cates that this patterning is not due to poor

excavation recovery. It is also worth noting

that only one fox cranium and three maxillae

were present in the collections, in very

noticeable contrast with the number of fox

mandibles, again suggesting that anatomical

elements likely to be attached to the pelts had

been removed from the site.

Despite the circumstantial evidence for

skinning and trapping activities at or near

THE EXPLOITATION OF CARNIVORES AND OTHER FUR-BEARING MAMMALS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

260

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

TABLE 1

Body Part Representation data for fox (Vulpes sp.) from the Trou de Chaleux

RUTH CHARLES

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

261

Chaleux, very few of the fox bones show any

direct butchery marks. The cut marks on five

fox bones from Chaleux do not indicate

skinning, but rather meat removal (humerus

and femora) and disarticulation (scapula).

Similarly the 3 cut fox bones from the Trou

des Nutons (a left mandible and two distal

right humeri) all indicate meat removal, as do

the marks noted on humeri from the Trou du

Frontal. The red fox bones from Star Carr

come from one individual (Fraser & King

1954, 73) and cut marks present on a phalanx

(Natural

History

Museum

Acc.

No

1958.11.10.43) are consistent with skinning

whereas marks noted on ribs, lumbar verteb-

rae, a humerus, femora and the tibii all

indicate meat removal. Additionally, Row-

ley-Conwy (in press) reports the presence of

a fox skull with transverse cuts across its

front from Ringkloster, relating to skinning.

Overall the evidence for the exploitation of

foxes at these sites is limited, suggesting that

although on occasion foxes were exploited

for both pelts and meat during the Late

Pleistocene and early Holocene this was not a

mainstay of the local economy. Today foxes

are considered vermin, and both vermin and

carnivores are not generally thought of as a

viable food resource in the way that rabbit or

hares are. Whether any such cultural distinc-

tion was made during the Pleistocene is

unclear, although it is worth noting that

within Klein’s sites in Russia the foxes do not

appear to have been used for food, but

instead discarded as complete carcasses.

It seems quite possible that, as well as

being the prey of humans, one or both species

of fox were resident in the Lesse valley caves

during the late Pleistocene and Holocene.

Their dens may be used over relatively long

time periods, and during such periods it is

likely that a selection of vertebrates, inverte-

brates and other food substances will have

been brought by them to the cave, accounting

for components of the faunal assemblage.

Similarly at various times the foxes them-

selves may have been the prey of other

carnivores living in this area. At Star Carr the

picture is somewhat different, with an

isolated red fox carcass brought to the site

and processed for its meat and pelt.

Whilst foxes cannot be viewed a primary

subsistence sources at any of these sites, it is

clear that they did have a role to play in the

subsistence economy of the hunter-gatherers

who used these places, and that they were

exploited for both their furs and their meat.

MUSTELIDAE

Wolverine (Gulo gulo)

Wolverines are today mainly restricted to

the taiga and southern tundra zones of

Eurasia, including parts of the old Soviet

Union, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Mongolia,

northern China, and also extend into the new

world in much of Canada, Alaska and

possibly the Rocky mountains. However, this

is by no means a reflection of their past

distribution. They are highly adaptable ani-

mals, and records from the earlier parts of

this century, as well as the last, suggest that

they were found in more southerly regions in

the recent past (Schreiber et al. 1989, 22–23).

They have extremely large home ranges,

approx. 800–900 km

2

in summer, and per-

haps even larger in winter (ibid., 22). The

wolverine is a predator, capable of taking

large mammals, although in general it is

mainly a scavenger of herbivore carcasses up

to the size of reindeer and red deer. Modern

wolverines are up to 1 metre in length, and

their pelts are dark brown (sometimes almost

black), with a pair of yellowish stripes

running from the shoulders to the rump. In

general, wolverines tend to avoid human

settlements, and to date there is little research

THE EXPLOITATION OF CARNIVORES AND OTHER FUR-BEARING MAMMALS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

262

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

available on their ecology and behaviour

patterns. It seems unlikely that wolverines

came into frequent contact with humans

during the Palaeolithic, and their vicious

reputation no doubt preceded them. Indeed,

wolverine remains are rarely found on

western European Upper Palaeolithic and

Mesolithic sites, and this species has only

been identified at two of the sites considered

here, the Trou de Chaleux and the Trou des

Nutons. Only two specimens (one from

Chaleux and one from the Trou des Nutons)

hint at an association with human activity

(see below).

In many, if not all, of the regions where it

is found today, the wolverine is traditionally

hunted for its fur. Like many animals, they

frequently follow set routes and setting traps

in ‘natural corridors’ such as ravines is

common practice among recent hunters

(Nelson 1973). As wolverines are also one

of the main scavengers from traplines,

wolverine traps are today frequently set near

the ends of trap lines to diminish predation

from other traps. Similarly, kill sites for other

large mammals provide excellent locations to

set traps for wolverines (as well as foxes and

wolves) as the smell attracts scavenging

animals. Because of the wolverine’s strength

and violent nature it is a difficult animal to

keep restrained and extra strong traps and

snares need to be used, although deadfall

traps are also highly effective.

Their fur is thought (R. Jacobi pers. comm.)

to be especially useful in extremely cold

environments, as it does not freeze when

damp, and consequently makes a fine edging

for hoods, amongst other uses. The specimen

from Chaleux is a partial scapula, with

numerous marks which may have been the

result of butchery activities across its posterior

surface. However, the true origin of these

marks could not be determined by micro-

scopic inspection. Examination of the speci-

men by Jill Cook of the British Museum

revealed that the most prominent marks

closely matched marks of natural origin found

on the remains of a cow from Draycott

(Andrews & Cook 1985). Others, less promi-

nent, could only be identified as possible cuts.

The other specimen, a proximal right femur

from the Trou des Nutons had a single,

somewhat ambiguous mark, which, as with

its counterpart from Chaleux, could neither be

confirmed or denied as a cut. if the marks from

both specimens were indeed the result of

butchery activity, then they would correspond

with meat filleting rather than skinning,

although the one would not preclude the

other. However, given the questionable nature

of the marks from these specimens, it remains

unclear whether the wolverine ever formed a

component in any stone age meal in the Lesse

Valley. Similarly it is unclear as to whether

these specimens are parts of the Late Magda-

lenian faunal assemblages, or a more recent

additions. Both the range of species present

alongside recent radiocarbon dating has

indicated that faunal material was accumu-

lated within the same geological units at the

Trou de Chaleux and the Trou des Nutons

during the Lateglacial and the early Post-

glacial (Charles 1994; Rosine Orban pers.

comm.). However, wolverines were certainly

known to Magdalenian hunter-gatherers; one

is engraved on a perforated baˆton from La

Madeleine (Cremades 1992). They have been

identified from other Lateglacial contexts in

north-western Europe such as Chelms Combe

at Cheddar (Andrew Currant pers. comm.) and

Petersfels (Albrecht et al. 1983, 78) and are

thought to have been present in north-western

Europe during the early Postglacial.

Badger (Meles meles)

Present knowledge is extremely patchy

about the temporal and spatial distribution of

RUTH CHARLES

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

263

badgers during the Holocene and Pleistocene

in western Europe. Their apparent presence

in Late Pleistocene assemblages is usually

taken as evidence for more recent contam-

ination. However, badger fossils have been

recorded from genuine Late Pleistocene and

early Holocene contexts in north-western

Europe, including Petersfels (Albrecht et al.

1983, 80) and Kendrick’s Cave (from which

two perforated badger teeth have been used

as pendants, Roger Jacobi pers. comm.).

Badgers are denning animals and live in

sets; the morphology of these is highly

variable, but they may be extremely large

covering many cubic metres. The tunnels

tend to be linked, and there are many

chambers, often with bedding of vegetation.

Badgers also ‘like’ using caves (Hans Kruuk

pers. comm.). Sets are often shared with

other carnivores, including foxes, otters and

wild cats. These sets are thought to be in long

term use, perhaps being used over centuries.

Indeed, one near Kirkhead Cavern in Cum-

bria is mentioned in the Doomsday Book and

is still in use. It is unclear whether these sets

are used continuously, or episodically by

different badger clans. Although in general

badgers prefer hilly districts, especially

heavily wooded ones (Neal 1948, 122), they

are highly adaptable, and can survive in a

range of habitats and soils. Many of the

Lateglacial caves discussed here, with steep

talus cones, surrounding slopes and proxi-

mity to water, would have proved ideal

locations for badgers.

It is possible that badgers may have played

some part in the accumulation of the faunal

assemblage found in the cave sites. Although

their diet is primarily made up of earthworms

(Kruuk 1989, 39), they are known occasion-

ally to eat a variety of foodstuffs including

salmon, frogs and toads, wood pigeon,

passerines, a variety of small mammals

including rabbits and hares, and carrion up

to the size of sheep and deer. They have even

been observed to kill lambs (Kruuk 1989,

Plate 11) and to take chunks of food,

including carrion, back to cubs in the sets.

In recent times omnivorous tendencies have

been observed amongst badgers in areas

away from extensive agriculture, where they

take carrion, small mammals and vegetable

matter. The cubs are prone to high mortality

rates within the sets, but this varies with local

ecological conditions (Hans Kruuk pers.

comm.). Kruuk has observed corpses of very

young badgers well away from sets, which

must have been taken there by adults, but

thinks that most will be either left inside the

set or eaten by adults. Similarly Kruuk has

noted that ‘small mammal remains can be

passed relatively undamaged in the faeces,

and their latrines inside the set or, in the

cave-based sets in an ‘entrance hall’ (Hans

Kruuk pers. comm.). One particularly inter-

esting feature is that badgers do not chew or

gnaw bones, so it is difficult actually to

demonstrate a direct link between badger

activity and the accumulation of faunal

remains. Given what has been outlined

above, badgers could have been responsible

for at least part of the accumulation of small

mammals and fish bones and even some of

the larger mammal bones, at many of the

Lateglacial caves discussed here, although

this cannot be conclusively demonstrated.

Direct butchery evidence was observed on

badger bones from the Trou de Chaleux,

Trou des Nutons, Gough’s Cave and Star

Carr. In each case only a small number of cut

marked bones were present, and the marks

indicate different processing activities at

different sites (Fig. 3).

An MNI of four was calculated for the

Chaleux badgers, based on the innominates,

scapulae and femora. No juvenile bones were

recorded. In total 66 badger bones were

present (1.8% of the assemblage). Although

THE EXPLOITATION OF CARNIVORES AND OTHER FUR-BEARING MAMMALS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

264

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

the NISP is too small to formulate any

meaningful discussion of significant trends

in BPR, it is interesting to note in passing that,

as with the foxes from Chaleux, the lower

portions of the badger limbs were totally

absent. Similar arguments to those used in

relation to the fox limbs (above) might be

applied to suggest a case for the skinning of

badgers (and consequently that they too might

have been trapped for their pelts).

The only cut marked badger bones from

Chaleux are five femora. Only longitudinal

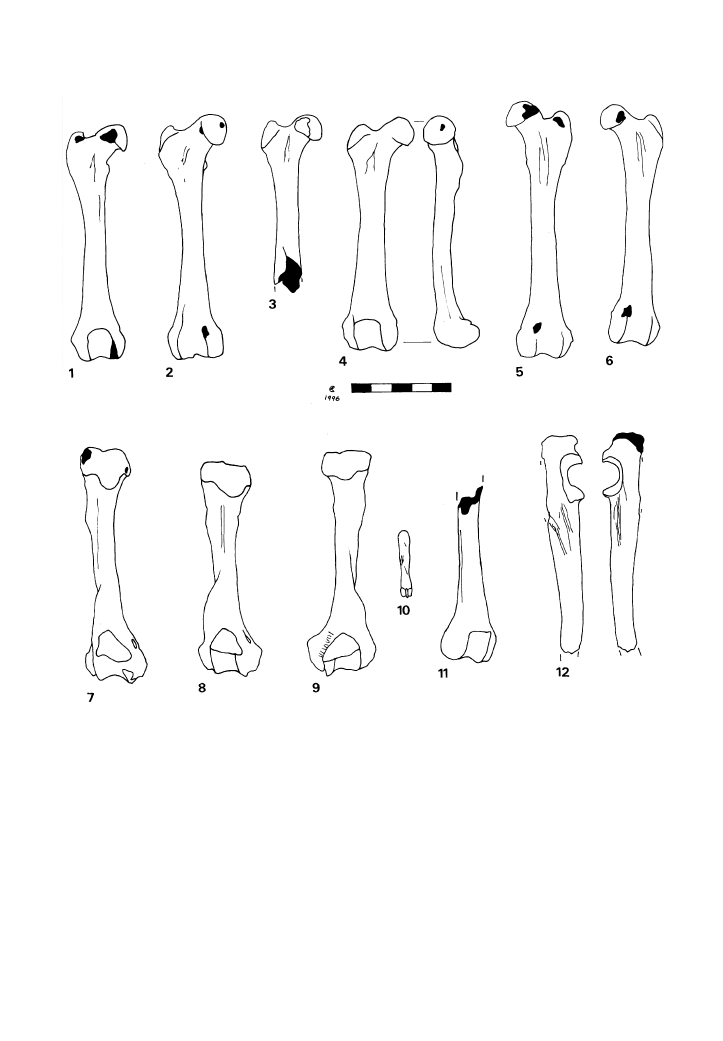

Figure 3

Cut-marked badger bones from the Trou des Nutons (1, 7, 8, 11 & 12), Trou de Chaleux (2, 3, 4, 5 & 6) and Star Carr

(9 &10).

RUTH CHARLES

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

265

groups of cuts were present, almost all of

which were located towards the proximal

ends. The same is true for the five cut bones

from Nutons (a right ulna, two left humeri, a

right femur and a distal left femur) and the

sole cut specimen from Gough’s Cave, a

juvenile humerus with longitudinal cuts

towards the proximal end of the shaft. In

each case these indicate meat removal,

suggesting that whilst badgers may have

been hunted/trapped for their distinctive

pelts, their meat was also of some interest.

Indeed meat removal is the only activity for

which there is any direct evidence at the Late

Upper Palaeolithic sites. In contrast, the two

cut specimens from the early Mesolithic site

of Star Carr show marks which correspond

with skinning (Fig. 3, Nos 9 & 10), although

meat filleting marks are also present on the

distal portion of a humerus. Similarly Row-

ley-Conwy (in press) noted a badger skull

with cut marks relating to skinning from

Ringkloster.

Pine marten (Martes martes) and other small

mustelids

Today there are approximately 53 separate

species of mustelid, which are found primar-

ily in the northern temperate zones of north

America and Eurasia (Schreiber et al. 1989).

These include the badger and the wolverine

(both discussed above) as well as marten,

mink, stoat and weasel. Each member of the

Mustelidae has its own particular set of

environmental preferences and behaviour.

The constraints of space prohibit a detailed

description of each species here.

Mustelids rarely occur in Lateglacial con-

texts in north-western Europe. None were

reported by Currant (1986, 1991) at Cheddar,

neither were any observed by Turner (1991)

in the Neuwied basin Lateglacial faunas.

Although some mustelids have been identi-

fied at the Lesse valley caves, only wolverine

and

badger

remains

(discussed

above)

showed any trace of human modification.

Overall mustelids were only present at these

sites in very low numbers (cf. Charles 1994).

In Mesolithic contexts, however, smaller

mustelids do appear to have figures within

the economy, although accounts are sparse.

At Star Carr the remains of two pine martens

(Martes martes) recovered by Clark show

butchery marks consistent with skinning and

meat removal. The only other evidence for

their exploitation comes from Denmark,

where Rowley-Conwy (1980) has commen-

ted on the specialist exploitation of smaller

fur bearing mammals within the Ertebølle

complex. At Tybrind Vig (Trolle-Larson

1987) the remains of at least 13 complete

pine martens were recovered alongside, a

polecat, and four otters, all apparently

processed for their pelts. Similarly some

articulated skeletons of pine marten were

recovered from Ringkloster (Rowley-Conwy

in press), transverse cuts corresponding with

skinning being present on the front of many

of the crania; overall at least 18 individuals

were recovered from the site.

Prehistoric exploitation of these species

seems to have focused on their pelts. The fact

that they do not appear to occur within

Lateglacial faunas is probably a function of

their distribution and habitat during this time,

rather than the result of any conscious

selection on the part of late ice age trappers.

The apparent increased emphasis on the

exploitation of such species, possibly linked

to the use of specialist trapping camps (cf.

Rowley-Conwy 1980) during the Mesolithic

is probably a reflection of the locally

available resources. The possibility that an

intensification in the trapping of fur bearing

mammals during the Ertebølle made a

valuable a commodity for trade with local

agricultural communities cannot be dis-

THE EXPLOITATION OF CARNIVORES AND OTHER FUR-BEARING MAMMALS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

266

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

counted, and links between the two groups

have been suggested both in terms of lithic

technology and pottery (Zvelebil & Rowley-

Conwy 1986).

FELIDAE

Lynx (Lynx lynx) and Wild Cat (Felis

sylvestris)

The modern range of the wild cat (Felis

sylvestris) includes much of Africa and

Eurasia, the species being highly adaptable

(Kurte´n 1968). In appearance they resemble

the modern domestic tabby, having thick

grey and black banded coats with white

throat patches, and often white patches on the

abdomen. Their range in western Europe has

been severely reduced during recent centuries

due to hunting and trapping, although small

populations have successfully recolonised

parts of Belgium, the Czech Republic,

Slovakia, Germany, France and Scotland.

Their primary diet consists of rodents,

supplemented by rabbits and birds (Anon.

1995, 18).

The lynx (Lynx lynx) is the largest of the

living lynxes, and has today become locally

extinct across much of western Europe.

However, it is primarily a woodland species

and is found in isolated patches of boreal

forest in modern Europe and is widely

distributed across the northern Asiatic taiga

belt, ranging to the south into Asia Minor,

Iran and Tibet (Kurte´n 1968). Adult males

weigh approximately 22 kg, the females

weighing slightly less. Both have greyish

coats, with varying degrees of rust and

yellow; most lynxes are spotted black or

reddish-brown, although occasionally the

pattern is indistinct. Amongst the most

recognisable characteristics are the promi-

nent black ear tufts and shortened tail with a

black tip. They are capable of hunting

ungulates three to four times their own size,

including roe deer and chamois; although

when such species are scarce they will take a

wide range of smaller mammals, especially

hares and pikas. They have a tightly defined

mating season between February and April,

with the young being born during May and

June (Anon. 1995, 13).

Common during much of the Weichselian,

the presence of the lynx within north-western

European Lateglacial faunas has been sus-

pected for some time, and has been con-

firmed as an integral part of the Lateglacial

interstadial fauna from Gough’s Cave, Ched-

dar (Currant et al. 1989; Currant 1991) by

AMS dating (OxA-3411 12650

120 BP

taken from a lynx tibia). Whether lynxes

were also present in north-western Europe

during the early Holocene is still open to

debate, although probable. A cut marked lynx

ulna from Aveline’s Hole, Somerset could

either date to the Late Pleistocene or early

Holocene, as human activity has been

identified and firmly dated at this site during

both periods. However, attempts to date the

lynx ulna via the Oxford AMS unit were

unsuccessful due to low collagen levels in the

specimen (Roger Jacobi pers. comm.). The

transverse cut marks along the shaft of this

specimen correspond with meat filleting, and

it is likely (although undemonstrated) that

this animal was skinned prior to processing.

Wild cat (Felis sylvestris) is also present in

many Late Pleistocene and early Holocene

faunas from western Europe. This species

occurs in all the Late Pleistocene faunas from

the Lesse valley caves, although none of

these specimens show any direct evidence for

human activity. Roger Jacobi (pers. comm.)

has identified two cut and charred distal tibii

of wild cat from Whalley II, associated with

geometric microliths and assumed to be of

mesolithic age. The species is absent from

the Late Pleistocene faunas from The Robin

RUTH CHARLES

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

267

Hood Cave in Britain and Grotte du Cole´op-

te`re and Sy Verlaine in Belgium and no felids

are recorded in the early Holocene assem-

blage from Star Carr. Outside the British

Isles the most convincing evidence for the

human exploitation of wild cat during the

Mesolithic comes from the Danish Ertebølle

sites of Tybrind Vig (Trolle-Lassen 1987)

and Hjerk Nor (Rowley-Conwy 1980, in

press), which yielded high quantities of bones

from fur bearing species, with a notable bias

towards wild cat at Hjerk Nor. The latter site

was suggested to be a special purpose camp

focussing on the exploitation of fur bearing

mammals, which again links in with the

suggestion (above) that a part of the Ertebølle

economy centred on the exploitation of fur

bearing mammals.

RODENTIA

Beavers (Castor fiber)

Beaver remains have been recorded from

Palaeontological

contexts throughout the

Pleistocene, and there is a continuous record

of this species in western Europe throughout

the Middle and Late Pleistocene (Kurte´n

1968). It is the largest living rodent, and on

average is approximately 110 cm in length.

As with many of the species discussed above,

human exploitation in Europe has signifi-

cantly effected the distribution of contem-

porary beaver populations; although remnant

populations persist in parts of Scandinavia,

the Rhoˆne and Elbe river networks and across

much of eastern Europe into Eurasia. Beavers

are another forest-dwelling animal, and

prefer boreal forest environments closely

allied with river networks. They instinctively

construct

dams,

regulating

water

levels

around their lodges (ibid.).

Beavers have been recovered from archae-

ological contexts in north-western Europe

dating to the early postglacial, although it is

unclear whether they were present in this

region during any part of the preceding

Lateglacial. The earliest radiocarbon deter-

minations available confirm beaver as part of

the northern European fauna by the 9th

millennium BP (OxA-1119 9320

120 BP

from Gough’s Old Cave, Britain and OxA-

2874 9220

90 BP from Stellmoor,

Germany).

Neither

of

these

specimens

showed any signs of human modification,

although another beaver specimen from

Stellmoor is described as a ‘mandibular

artefact of beaver’ (OxA-2873 7830

80

BP; Hedges et al. 1993). Other finds of

beaver within Lateglacial age faunas are

known — the partial

remains of one

individual was recovered from the Grotte de

Sy Verlaine, although whether this specimen

is truly of Lateglacial age is ambiguous (cf.

Charles 1994).

Coles & Orme (1983) propose a subtle

relationship between beaver and human

modification of the landscape, in which the

presence of beaver dams may have led to

locations becoming desirable places for

Mesolithic exploitation. In addition to the

changes in local landscape, the presence of

beavers themselves may have held some

attraction for hunter-gatherers. Eleven of the

beaver bones from Star Carr show cut marks

corresponding with skinning, meat filleting

and disarticulation (Fig. 4). Rowley-Conwy

(in press) reports a beaver skull with skinning

marks from Ringkloster. Beavers make good

eating (Nelson 1973) and their fat, as that of

other species discussed here, would have had

many uses, as a part of prehistoric diet as

well as a resource for other activities. In

addition to this, beavers of both sexes also

produce castoreum, a yellow fluid produced

in the castor glands located near the anal

opening (ibid.). This is used by the beavers to

mark their scent on the shore around their

THE EXPLOITATION OF CARNIVORES AND OTHER FUR-BEARING MAMMALS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

268

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

dams and lodges. Other glands also located in

this region secrete an oil which is used to

maintain their fur quality. If these glands are

extracted, dried and mixed together, their

secretions can be used to make bait for other

terrestrial fur species (ibid.) or medicine

(Kurte´n 1968).

Ethnographic accounts of north American

trappers detail various methods for trapping

beaver and other small mammals (Davis

1986). One common thread is that they are

particularly difficult animals to capture due

to their complex behavioural patterns, and

complicated trapping methods, differing from

those commonly used on land based mam-

mals, are required (Nelson 1973). Having

first identified the location of beaver lodges

in a region and checked that they are in use,

trappers must next locate beaver runways —

habitually used underwater channels from the

beaver lodge and nearby dens to their feed

pile. In winter these are often under ice, and

can be detected by sound. The runways are

used all year round and they provide an

excellent location for setting snares. Nelson

recounts (ibid., 255–257) that multiple snares

are set by the Kutchin Indians in tiers so that

they fill the runway. Such snares are best

checked every two to three days, although

returns diminished once the beavers become

aware of their presence.

Arctic hare (Lepus timidus) and brown hare

(Lepus europaeus)

Present distribution of arctic hare (Lepus

timidus) ranges across to tundra and con-

iferous forest zones of Eurasian Russia and

west Siberia above 50º north. Their distribu-

tion is determined to some degree by

altitude,

Yalden

(1971)

documented

an

altitudinal split between brown and arctic

hares in which the arctic hares occupied a

higher niche between 280 m and 570 m OD.

Their preferred habitat is a mixture of

Calluna- and Eriophorum-dominated heath,

sheltered from predominant winds and away

from grassy areas, although it is widespread

within boreal forests and arctic forest region

(Kurte´n 1968). Population densities tend to

fluctuate within 7 to 12 year cycles, most

probably

linked

to

fluctuations

in

the

numbers of their major predators (especially

the lynx). A striking feature of Lepus timidus

is the change in pelage during the year —

during the summer months the coat is

Figure 4

Cut-marked beaver bones from Star Carr.

RUTH CHARLES

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

269

brown, but between autumn and spring the

coats turn white. It is one of the larger

lagomorphs, average size being between 52

to 70 cm.

Brown hares are today widespread across

much of Europe (excluding the Iberian

peninsula) and the Near East; this species is

also gradually extending into Scandinavia,

replacing local populations of arctic hares.

This

species

prefers

open

grasslands,

although as with its arctic counterpart, is

found throughout the European boreal forest

zone. This species does not undergo a colour

change, and as its name suggest is brown in

colour and slightly smaller than arctic hares,

the average size being between 48 and 68 cm

in modern specimens.

The exploitation of hares in prehistory has

rarely caused much comment, although

during the Lateglacial a case can be made

for the recognition of specialist hare trapping/

processing stations (cf. Charles & Jacobi

1994). Boyle’s recent review of Upper

Palaeolithic faunas from south-west France

reveals a marked increase in the numbers of

hares and rabbits during the Late Magdale-

nian and Azilian (1990, 203), and again the

use of some sites as specialised processing

camps is a strong possibility. For example,

Boyle cites the striking example of Pont

d’Ambon, in which the conventional view of

the faunal assemblage is one of red deer

domination (90% of the large herbivore

fauna) however, if calculations are modified

to include the hares and rabbits (represented

by over 6000 bones), then red deer fall to

only 8.1% of the species at the site — rabbits

and hares accounting for almost 90% of the

fauna.

Hares possess a number of potentially

attractive features apart from their meat for

Late Pleistocene trappers. Their pelts could

have provided warm linings and trimmings

for clothing, their bones the raw materials for

a range of tools, and sinews and tendons the

materials for cordage and thread.

The Robin Hood Cave at Creswell Crags is

perhaps one of the better known examples of

a Lateglacial hare exploitation site. Butchery

evidence was used as a key to re-assess the

faunal assemblage, revealing that the only

species whose presence at the site was

demonstrably due to human activity were

arctic hares. Individual cut specimens of

these were selected as samples of AMS

dating (Charles & Jacobi 1994). As only low

numbers of cut hare bones were present and

as hares and rabbits are both extremely lean

animals, it was suggested that use of this site

during the Lateglacial was short-lived, as

humans could not have survived for long on

such a lean diet, the phenomenon of ‘protein

poisoning’ (Speth & Spielmann 1983) being

invoked.

Additionally evidence for the exploitation

of hares has been noted at three further sites

under discussion here, all dating to the

Bølling Interstadial phase of the Lateglacial

— The Trou de Chaleux (three cut speci-

mens), the Trou du Frontal (four cut speci-

mens) and Gough’s Cave at Cheddar (three

cut specimens). Whilst none of these sites

can be seen as a specialist hare processing

camps, it is worth noting that this species

provided a dietary change from the mainstays

of Late Palaeolithic diet recorded at these

sites — the horse, aurochs and red deer.

DISCUSSION

Whilst by no means can it be argued that

carnivores and other fur-bearing mammals

formed a dietary staple for western European

hunter-gatherers during the Late Pleistocene

and early Holocene, it is clear that they did

make a contribution to the human economy.

Rowley-Conwy (1980) has argued that the

exploitation of fur bearing mammals is most

THE EXPLOITATION OF CARNIVORES AND OTHER FUR-BEARING MAMMALS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

270

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

likely to occur during the winter, as this is the

season when their fur is of the highest

quality. Accounts of recent north American

hunters and trappers (Nelson 1973) concur

with this suggestion, and add that fur-

trapping primarily for trading purposes is

only likely to occur in times of abundance

(Winterhalder 1980). It is unlikely, however,

that animals were trapped solely for their

furs, and the evidence presented here con-

firms that meat was removed from many of

the carnivores and fur bearing mammals

discussed above. In addition to providing

pelts for clothing and barter, such animals

could have provided an occasional alternative

to dietary staples such as reindeer, horse, red

deer and aurochsen and/or provided meat

when such herbivores were rare or absent.

Whilst the role of larger mammals cannot

be understated during the European Late

Palaeolithic and Mesolithic, a picture of

increased emphasis on the exploitation of

fur bearing mammals during this period is

emerging alongside the recognition of spe-

cialist exploitation camps such as the Robin

Hood Cave and Hjerk Nor. This suggests a

broadening of the subsistence base. Rather

than arguing for a dramatic shift in the nature

of faunal exploitation during the Lateglacial

and early Postglacial, it is suggested here that

the exploitation of fur bearing mammals and

other carnivores reflects an expansion in the

economic base.

In addition to providing a supplement to

dietary staples of locally available plant

foods, ungulate and marine resources, the

meat from carnivores and fur-bearing mam-

mals could have been used as bait to entice

further animals into traps. This is certainly

possible, although regular use of meat

obtained in this way is unlikely due to the

low minimum number of individuals counts

for each species encountered at each site.

It is probable that an expansion in the

subsistence base can be viewed within the

broader context of environmental change

during the Lateglacial and the eventual

development of Boreal forests in north-

western Europe during the early Postglacial,

bringing with it commensurate changes in

regional ecology. The data discussed within

this paper are drawn from archaeological sites

dating either to one of the Interstadial phases

of the Lateglacial or to the early Postglacial.

The evidence for forest development during

the Bølling Interstadial is poor for north-

western Europe, and so the true nature and

extent of forest/tree cover surrounding the

sites discussed here and dating to that period

remains unclear. Better information is avail-

able for the early Postglacial (Simmons et al.

1981), particularly in the vicinity of Star Carr

(Walker & Godwin 1954, Cloutman 1988,

Cloutman & Smith 1988, Day & Mellars

1994).

The European earlier Holocene is gener-

ally characterised by the increase in plant and

tree cover leading to the eventual appearance

of climax forest during the Atlantic phase of

the Flandrian; alongside this eustatic and

isostatic changes radically transformed the

landscape, including the formation of the

English channel and the Irish Sea (Simmons

et al. 1981). The larger mammals such as red

deer (Cervus elaphus) present in north-

western Europe during the Lateglacial and

early Postglacial are relatively flexible in

their behavioural patterns, and are known to

congregate in large herds in open environ-

ments and to lead far more solitary life styles

in forested ones. Shifts in exploitation

strategies have been suggested (Jacobi et al.

1976; Simmons et al. 1981) as adaptations to

these environmental changes.

A model developed to explain the diversity

of resource procurement amongst the north

American Cree seems the most appropriate

analogy here, in which the vast and widely

RUTH CHARLES

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

271

(but unevenly) distributed resources of boreal

forests are recognised by foragers familiar

with a large area, but in which it is only

feasible to exploit a small portion in any

given season or year (Winterhalder 1983). By

applying the general principles of Optimal

Foraging Theory (cf. Krebs 1977), a series of

different ‘patches’ within the boreal forest

can be recognised in which the available prey

occurs in small, dispersed ‘packets’. Conse-

quently, the expectation is that foragers

spend a considerable amount of time search-

ing for these ‘packets’, pursue a relatively

large proportion of the species encountered

on any given trip and so have a fairly broad

dietary range and utilise a wide range of

‘patches’.

In such a model one would expect the

primary dietary focus to be towards the

exploitation of larger mammals, further

subsidised by the trapping of smaller mam-

mals. This suggestion is certainly borne out

at many of the sites discussed here — the

Trou de Chaleux, Trou des Nutons, Trou du

Frontal, Gough’s Cave, Ringkloster, Tybrind

Vig and Star Carr). These faunal assem-

blages are dominated by large and medium

sized ungulates, all of which show extensive

butchery marks relating to skinning, meat

removal,

disarticulation

and

subsequent

smashing of bones for marrow. Additionally,

various smaller fur bearing mammals are

present which bear evidence for both skin-

ning and meat extraction. All of these sites

can be interpreted as hunting camps, and in

most cases the use of these locations by late

Pleistocene and early Holocene hunter-gath-

erers is believed to have been seasonal. It

seems most likely that when the opportunity

arose for the exploitation of small game this

was unlikely to be disregarded. Efficient

trapping of such animals could be greatly

enhanced by the use of ‘unattended facilities’

(or traps), as the pursuit of larger mammals

can be combined with the routine checking

of trap lines, thus maximising the potential

returns. Such an explanation is proposed here

to account for the widening of the dietary

niche within north-western European Late

Palaeolithic and Mesolithic groups.

Such a model does not, however, exclude

the presence of specialist trapping camps

aimed primarily at the recovery of pelts (in

this case the Robin Hood Cave and Hjerk

Nor) — and again such sites have been

recognised in both the Late Upper Palaeo-

lithic and Mesolithic, although they are

generally seen as exceptions to the general

‘rule’ of large-mammal dominated sites.

Alongside this the possible expansion of

symbolic expression via clothing and perso-

nal adornment cannot be excluded, although

this aspect of stone age life remains difficult

to quantify. Highly stylised engravings are

known from a variety of Lateglacial and early

Postglacial locations, including Go¨nnersdorf

in Germany (Bosinski 1991), Gough’s Cave

(Charles 1989) and Kendrick’s Cave (Sievek-

ing 1971) in Britain. Gamble (1991) has

suggested that the Magdalenian ‘symbolic

explosion’ of the Lateglacial can be inter-

preted within the context of social knowledge

and communication between pioneer groups

re-colonising the north-western European

mainland, allowing for the maintenance of

social contacts over great distances. He notes

that this use of symbolism within material

culture appears to diminish after the pioneer

phase. However, with the dramatic changes in

landscape coincident with the early postgla-

cial, one can again detect the increasing use of

symbolic media within the archaeological

record. Star Carr in Britain (Clark 1954),

Berlin-Biesdorf (Reinbacher 1956), Hohen

Viecheln (Schuldt 1961) and Bedburg-Ko¨nig-

shoven in Germany (Street 1991) have

yielded worked frontlets of red deer: whilst

the use of these objects remains ambiguous,

THE EXPLOITATION OF CARNIVORES AND OTHER FUR-BEARING MAMMALS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

272

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

they are frequently interpreted as head-gear

used as part of hunting equipment and/or

ritual. Inspection of the ones recovered from

Star Carr revealed that the antlers on these

specimens had been shaved or whittled on

their medial surfaces, which would have

served to lighten the weight of these objects

whilst not diminishing their overall effect

when viewed from below, adding some

circumstantial evidence to the suggestions

that they were indeed worn, and that they

were less likely to be used in a hunting

situation in which the wearer was unlikely to

be viewed from below.

In addition to the isolated occurrences

described above, lithic technology shifted

from the pan-European early Mesolithic

‘broad blade’ industries (consisting primarily

of obliquely blunted points) to the regionally

specific late and later Mesolithic ‘narrow

blade’ industries (made up of a range of

microlithic forms) (Jacobi 1976, Gendel

1989, Arts 1989). The redefinition of the

landscape by marine transgressions, river

development and expansion and forest growth

would have had a profound impact on

Mesolithic communities and their communi-

cations. If population densities changed (cf.

Meiklejohn 1978), and social groups re-

structured as an adaptation to different

resource availability, then a need for the

maintenance of social contact and knowledge

between such groups would have become a

priority. This social change may be invoked as

at least one of the reasons behind an

expansion of symbolic behaviour during the

European Mesolithic.

Whilst it is unlikely that archaeologists can

today reconstruct the precise belief systems

associated with the use of such animals, it is

perhaps possible to acknowledge that in

certain instances a symbolic explanation is

the most appropriate. Examples might in-

clude the dog burials from the late Mesolithic

cemeteries at Skateholm and Bredasten,

Sweden (Larsson 1994) and at Vedbaek,

Denmark (Brinch Petersen 1990) as well as

the child burial placed on a swan’s wing at

the Ertebølle cemetery at Vedbaek, Denmark

(Albrethsen & Brinch Petersen 1976).

Whilst it is true that in many recent and

contemporary societies the hunting/trapping

and subsequent exploitation of small mam-

mals is often undertaken by women and

children, this does not preclude males taking

part in such activities (cf. Szeuter 1988).

Suggestions that an emphasis on the exploi-

tation of smaller mammals equate with an

increased role for women and children in the

food quest cannot be supported here. The

evidence presented shows a direct link

between human activity and the exploitation

of small mammals; cut marks (and other

forms of butchery evidence) can say little

about the gender or biological sex of the

individual who wielded the stone tools which

made them — only that such activities took

place. Whilst the search for female perspec-

tives and roles within Palaeolithic society

remains an important research issue (cf.

Conkey 1991), there seems little opportunity

to develop it within the framework of this

paper, unless the reader wishes to reinforce

stereotypes of Palaeolithic and Mesolithic

societies in which men hunted big game and

women small game. Neither such scenario is

necessarily valid, and the gender of the

hunters, trappers and butchers remains un-

known.

CONCLUSIONS

The evidence presented here relating to the

exploitation of carnivores and other fur

bearing mammals during the late Palaeolithic

and early Mesolithic is drawn from the

author’s personal observations combined

with examples known from the published

RUTH CHARLES

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

273

literature. By no means can it be seen as a

definitive account. The purpose of this paper

has been to document specific instances

where such mammals have been exploited,

and to draw attention to aspects of Palaeo-

lithic and Mesolithic faunal exploitation

beyond the conventional view of these

populations as big game hunters. This is not

to say that large mammals were not hunted

— they clearly were, and dominate many of

the faunal assemblages discussed here. In-

stead this paper has highlighted another

aspect of prehistoric subsistence, suggesting

that carnivores and fur bearing mammals

provided occasional variety to Late Pleisto-

cene and early Holocene diets as well as a

useful resource for pelts used in clothing

manufacture and trade. It is hoped that

evidence reported here will stimulate an

awareness of the potential within Palaeolithic

and Mesolithic faunal assemblages to provide

information on the role of subsidiary re-

sources, such as those provided by fur

bearing mammals.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Peter Rowley-Conwy for

providing access to his unpublished work, Juliet

Clutton-Brock and Pat Carter for giving access to Star

Carr material, Hans Kruuk for his many comments

about badger behaviour, Roger Jacobi for adding to my

knowledge of the British Lateglacial database and

Derek Roe for his many comments on draft versions

of this paper. Figure 1 was drawn by R.M.C. Cook.

Much of the material reported here was analysed as part

of doctoral research undertaken by the author between

1990 and 1994 and funded by The British Academy,

The Queen’s College, Oxford and grants from the

Meyerstein Fund of Oxford University and Christ

Church, Oxford.

Department of Archaeology

University of Newcastle

Newcastle-upon-Tyne NE1 7RU

REFERENCES

ALBRECHT, T., BURKE, H.

and

POPLIN, F.

1983: Naturwis-

senschaftliche Untersuchungen an Magdale´nien-Inven-

taren

vom

Petersfels,

Grabungen

1974–1976

(Tu¨bingen, Tu¨binger Monographien zur Urgeschichte,

Herausgegeben von Hansju¨rgen Mu¨ller-Beck Band 8).

ALBRETHSEN,

S.E.

and

BRINCH

PETERSEN,

E.

1976:

Excavation of a Mesolithic cemetary at Vedbaek,

Denmark. Acta Archaeologica 47, 1–28.

ALLSWORTH-JONES, P.

1986: The Szeletian and the

transition from Middle to Upper Palaeolithic in Central

Europe (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

ANDREWS, P.A.

and

COOK, J.

1985: Natural modification to

bones in a temperate setting. Man 20, 675–691.

ANON

. 1995: Wild Cats (London, IUCN).

ARTS, N.

1989: Archaeology, environment and the social

evolution of later band societies in a lowland area. In

Bonsall, C. (ed.) The Mesolithic in Europe (Edinburgh,

John Donald Publishers Ltd), 291312.

BARTA, J.

1989: Hunting of Brown Bears in the

Mesolithic: Evidence from the Medvedia Cave near

Rusı´n in Slovakia. In Bonsall, C. (ed.) The Mesolithic in

Europe (Edinburgh, John Donald Publishers Ltd), 456–

460.

BENECKE, N.

1987: Studies on Early Dog Remains from

Northern Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science 14,

31–49.

BRATLUND, B.

1991: The bone remains of mammals and

birds from the Bjørnsholm shell-mound. Journal of

Danish Archaeology 10, 97–104.

BRINCH PETERSEN, E.

1990: Nye grave fra Jaegerstenal-

deren. Strøby Egede og Vedbaek (Copenhagen, Natio-

nalmuseets Arbejdsmark), 19–33.

BOSINSKI,

G.

1991: The representation of female

figurines in the Rhineland Magdalenian. Proceedings

of the Prehistoric Society 57(1), 51–64.

BOYLE, K.V.

1990: Upper Palaeolithic Faunas from

South-West France: a zoogeographic perspective (Ox-

ford, British Archaeological Reports, International

THE EXPLOITATION OF CARNIVORES AND OTHER FUR-BEARING MAMMALS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

274

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

Series 557).

CHARLES, R.

1989: Incised ivory fragments and other

Late Palaeolithic finds from Gough’s Cave, Cheddar,

Somerset. Proceedings of the University of Bristol

Spelaeological Society 18(3), 400–408.

CHARLES, R.

1994: Food for Thought: Late Magdalenian

Chronology and Faunal Exploitation in the north-

western Ardennes (Unpublished D.Phil. dissertation,

University of Oxford).

CHARLES, R.

and

JACOBI, R.M.

1994: Lateglacial faunal

exploitation at the Robin Hood Cave, Creswell Crags.

Oxford Journal of Archaeology 13(1), 1–32.

CLARK, J.G.D.

1952: Prehistoric Europe: The economic

basis (London, Methuen & Co. Ltd).

CLARK, J.G.D.

1954: Excavations at Star Carr, an early

Mesolithic site at Seamer, near Scarborough, Yorkshire

(Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

CLOUTMAN, E.W.

1988: Palaeoenvironments in the Vale

of Pickering part 2: Environmental History at Seamer

Carr. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 54, 21–36.

CLOUTMAN, E.W.

and

SMITH, A.G.

1988: Palaeoenviron-

ments in the Vale of Pickering, part 3: Environmental

History at Star Carr. Proceedings of the Prehistoric

Society 54, 37–58.

CLUTTON-BROCK, J., CORBET, G.B.

and

HILLS, M.

1976: A

review of the family Canidae, with a classification by

numerical records. Bulletin of the Natural History

Museum (Zoology) 29(3), 119–199.

COLES, J.M.

1991: Elk and Ogopogo. Belief systems in

the hunter-gatherer rock art of northern lands. Proceed-

ings of the Prehistoric Society 57(1), 129–147.

COLES, J.M.

and

ORME, B.J.

1983: Homo sapiens or Castor