D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

20

13

A L E X A N D E R PER ESW E TO FF-M O R A T H

An Alphabetical Hymn by St. Cyril of Turov?

On the Q uestion o f Syllabic Verse Com position in E a rly M edieval

Russia

We redej> oft & finde]) y-write

& Jjis clerkes wele it wite,

Layes j>at ben in harping

Ben y-founde o f ferli Jjing.

—-Anonymous: Sir Orfeo

1. In a 16th-C manuscript containing a peculiar redaction o f the Life o f St.

Cyril o f Turov, we find a short list of Cyril’s writings which ends: ина

лшожашаїа ыаписа, цркви прєдасть; ка№ьиъ великій ш покалыми

створи к гоу по глава а^вХки. се и доnN't творА в-Ьрши рКстіи ліое.1

It has been observed more than once that this Great Kanon, каи^ыъ ве

ликім,

has never been found and that it may well be lost for ever (Makarij

1995 [1868], 365; Eremin 1955, 362 note; Podskalsky 1996, 387).

In this paper I shall argue that the Great Kanon (henceforth: KV) as

cribed to Cyril actually was composed by him, and that at least parts of this

hymn have long been known in the scholarly literature as an anonymous

South Slavic text.

2. The short Life o f Cyril appears among the texts for April 28 in the sec

ond redaction of the Old Russian Synaxarion (Пролог), a calendrically ar

ranged miscellany of Saints’ Lives with a complex textual history. The Life

was most probably written after the Tatar invasion; the oldest known MS

with it, however, dates from the late 14th/early 15th C, and in this redaction

the Great Kanon is never mentioned. Instead we read: си в с а л\ыожаи-

шаіа ыаписавъ и цркви прєдасть· ідже Т a o n u n Ii держить вЪргша ї

с&рьскиїа

[sic] люди· в са просвЪциюцж ї весела ці и.2 It is beyond the

scope o f this paper to determine whether the passage about the Great

Kanon is original, but I shall shortly return to the question of its trustwor

thiness.

1 “He wrote many other works and bequeathed to the Church; he created a Great Peniten

tial Kanon for the Lord according to the heads [or: chapters?] of the alphabet, which is

celebrated [?] by the faithful Russian people up to this day.” Cit. ed. Suchomlinov 1858,2.

2

Cit. ed. Nikol'skij 1907, 64; translation in Franklin 1991, 169f; this redaction is

reflected in other published late MSS as well.

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

20

13

2.1 The Synaxarion text is the only early source on Cyril’s life that has

come down to u s— no contemporary references to him e x ist. In the schol

arly literature it is customarily stated that Cyril was bom in Turov at the be

ginning of the 12th C, elected bishop of that same town in the 1160s and

that he died before 1182 (the latter date has been particularly disputed). In

spite o f these conventional dates there may be good reason to doubt his

episcopate and, indeed, his very existence as we picture it. Franklin recent

ly put forward an almost stunningly reductionist “cautious version” of his

biography (Franklin 1991, lxxv, Ixxx; cf., however, Thomson 1992):

Kirill of Turov probably existed. If he did exist, then he probably lived

in the mid- to late twelfth century, was certainly a monk, and perhaps

the bishop o f Turov (Turau). He may also have written a number of

homilies and prayers, and perhaps some letters [...] As a figure in his

tory Kirill of Turov is elusive almost to the point of invisibility. Kirill

o f Turov exists in tradition, exists as tradition. But whether or not the

tradition stems from an identifiable person, and how such a person

actually lived— these are matters o f the vaguest conjecture. The tradi

tion of Kirill o f Turov is the large number of works attributed to him.

Even in this extreme version, Cyril the writer remains with us in the form

of a cluster of (presumably) 12th-C works of a certain stylistic, thematic

and theological homogeneity which early on were attributed with some

consistency to a person whose vita bears the impress of truth. In this vita

we read about a learned anchorite and later bishop, bom of well-to-do par

ents in Turov in the first half of the 12th C— and all of this may be true. In

the discussion that follows, it should be borne in mind that the writer whom

we call Cyril of Turov probably acquired the basis of his phonetic system

in Turov (between Kiev and Volhynia) early in the 12th C. He seems to have

been given a fine education, as his works reveal a man o f extensive reading

and considerable rhetorical skills. He was certainly a liturgist.

3.1.1 The kanon is one of the most important and complex hymnic ■

forms of the Byzantine church. Ideally it consists of nine odes, each one of

which contains several stanzas: the initial heirmos and usually three or four

troparia (sometimes more). The kanon as a whole does not follow any sin

gle metrical form, but each heirmos serves as a model for the following

troparia (a necessity as the troparia were originally sung to the same melo

dy as the heirmos). The heirmos is thematically based on one of nine spec

ified biblical canticles which it paraphrases in such a way that the heirmos

o f the first ode alludes to the first canticle (from Exod. xv), the heirmos of

116

Alexander Pereswetoff-Morath

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 44 1998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

20

13

An Alphabetical Hymn by St. Cyril o f Turov? 117

the second ode alludes to the second canticle (from Deut. xxxii), and so on.

The specific liturgical theme of the kanon is treated in the troparia, ideally

drawing from the imagery and wording of the model canticle (Wellesz

1961, 198-245; von Gardner 1980,40ff).

3.1.2 Acrostics were introduced into kanon composition at an early

stage, whereby the first letters of the stanzas made up messages such as the

name of the composer or the title of the hymn. Alphabetical acrostics,

where the initial letters formed the alphabet row, were also popular in

kanons (Weyh 1908, 4 2 f; Krumbacher 1897, 697).

3.2 The syllabism and strophic form of the Byzantine originals were of

ten well preserved in the translated hymns of the first period of South Slavic

letters (Jakobson 1985a), although there are also a great many hymns that

do not present any traces whatsoever of the Greek isomorphism and poeti

cal form (von Gardner 1980, 40ff; Fedotov 1986, 21 ff).

.

The knowledge gained from translating these texts was put into practice

by South Slavic writers at an early stage as they began to compose original

hymns of remarkable technical complexity (Jakobson 1985a). It has never

been cogently demonstrated that such a development ever took place in ear

ly medieval Russia;3 still, it seems to be clear that East Slavic literati were

aware of the syllabic structure of the imported hymns and poems right up

to the time of the elimination of the weak jers (ь/ъ) in Old Russian, which

led to the collapse of the ancient syllabic and vocalic system and thereby to

the disappearance of the old poetic forms (cf. Zykov 1974, 310f).4 In litur

gical poetry the old syllabism was often preserved long after the jers had

been dropped in everyday speech, as the hymnic texts were supported by

archaic liturgical pronunciation as well as by written music (which treated

the jers as equivalents to the full vowels, cf. Uspenskij 1997.)

3.3.1

As a hymnic form the kanon was part of the pre-existing liturgical

model taken over by Slavia Orthodoxa from Byzantium, and South Slavic

writers were to compose kanons of their own as well (cf. Jakobson 1985a-

b). These original and translated South Slavic kanons were available in

Russia as early as the 11th С (cf. Koschmieder 1952) and, in addition, a

small number of Kievan Russian kanons were written for the feasts of au

tochthonous Russian Saints (Podskalsky 1996, 376ff).

3 The observations in Bylinin 1988 seem promising but this study reached me too late to

be considered in the present paper.

4 In secular language the weak jers seem to have disappeared completely in Novgorod/

Smolensk and Galicia/Volhynia long before the 13th C, whereas the process in Kiev and

“на других территориях, вероятно, тяготевших к Киеву, [...] проходил медленнее и

получал завершение только к середине XIII в.” (Ivanov 1995, 23 ff, cit. p. 25).

Scando-Slavica, Tomus44 J998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

20

13

3.3.2 The Byzantine custom of constructing kanon acrostics with au

thors’ names and hymn titles was known and imitated by South and East

Slavs alike (Hannick 1973), and the Greek Metropolitan John seems to

have been an early intermediary in Russia. His Greek kanon for the martyr

brothers Boris and Gleb had an acrostic, as the title of the Slavic translation

states (cf. 4.1.1). An acrostic has also been identified in the early East

Slavic kanon for St. Theodosius of the Caves, allowing us to attribute it

with some certainty to the monk Gregory of the Caves— with the exception

of Cyril the only native Kievan Russian kanon-writer known by name.5

3.3.3 Except for the one mentioned in Cyril’s Life, not a single Slavic

kanon with an alphabetical acrostic seems to be known before the 16th C,

but other alphabetical poems were composed. For example, one of the ear

liest Slavic poems to have come down to us is the South Slavic dodecasyl-

labic Azbucnaja molitva (henceforth: AM)6 whose initial letters form a

Slavic alphabet. Similar poems were to be composed by South Slavic writ

ers and frequently copied in Kievan Russia. In time, original Russian alpha

betical poems would also appear, the oldest of which (whose Russian

origin is beyond doubt) have survived in MSS from the 15th C.7

4.1.1

We have already seen that the Life of St. Cyril originated in the

middle of the 13th С at the earliest, and that the mention of the alphabetical

kanon has yet to be traced in MSS older than the 16th C. The reported

kanon title, however, is remarkable and the wording по главами has

known parallels in only two other texts: Metropolitan John’s Kanon for

SS. Boris and Gleb (11th С) — Канонъ тьм а же святыима, имЪяи по

главамъ грьчьскый стихъ: Си Давыду пЪснь приношу Роману (cit. ed.

Abramovic 1916, 138)— and a translated hymn— по грьчьскоумоу· no

глйллъ·:· л£ъ.Боуковьи— which has survived in a 12th-C Russian MS (see

5.3.2). The peculiar formula can hardly have arisen spontaneously in KV,

and we shall see that the author may have borrowed both the title and the

idea for the hymn from the latter text. It would not be too bold to suggest

that the author’s name, as well as the original title, was present in the MS

from which Cyril’s biographer (or the copyist/editor of his Life) derived his -

information about KV.

5 Spasskij 1949,128f. Gregory is mentioned as ‘'творець каноном” at the Monastery of

the Caves at the end of the 11th C.

6 Variously attributed to Constantine the Philosopher and Constantine of Preslav (see Olof

1973; Kuev 1974; cf. Zykov 1974).

r

7 The genre was to enjoy certain popularity in Muscovy, where the poems, old and new,

were known as Tolkovyja azbuki. Any traces of syllabic organisation in the poems at that

time were rudimentary at best (Pereswetoff-Morath 1994; Steensland 1997).

118

Alexander Pereswetoff-Morath

Scanilo-Slavica, T om us441998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

20

13

4.1.2

We now know that syllabic as well as alphabetical poetry was cop

ied in Kievan Russia and that acrostics with names and titles were part of

native kanon composition. Cyril thought highly o f church singing8 and was

exceptionally creative in his own kanons: the two extant kanons which tra

dition ascribes to Cyril appear to be the only two original Slavonic kanons

whose heirmoi are original compositions and not translations from the

Greek (Mathiesen 1971, 197; cf. Spasskij 1949, 131).9

It would hardly be surprising if the only Slavic writer to compose his

own heirmoi in accordance with Greek tradition was also the only one to

have constructed a Byzantine-style alphabetical kanon. To my knowledge

it has never been noted in the scholarly literature that Cyril used acrostics

and alphabets in his texts (cf. note 11, however), but an undeniable alpha

betical principle can be demonstrated in his Prayer Kanon, Канонъ

молебень (henceforth: KM).10 In this hymn each ode ends with one stanza

to the Trinity (triadikon) and one to the Mother of God (theotokion) (the

ninth ode deviates slightly). In five cases out of nine, the first letter of the

alphabet, ‘A ’, opens the first troparia but no other (out o f a total of 45 stan

zas)! In odes 1-8, all triadika but one and all the theotokia begin with the

letter ‘Я ’ (compared to merely two of the remaining 24 stanzas)! Not sur

prisingly, the letter ‘Я ’, which opens the two concluding stanzas o f each

ode, ends the alphabet row of most Slavic alphabetical acrostics.

It is obvious that the odes of KM are flanked by the symbolically

charged beginning and end of the alphabet. There are exceptions to this pat

tern, but we do not have the author’s text before us. We note the fact that

Cyril was familiar with alphabetical symbolism, as exemplified in a kanon

by him. In the other kanon ascribed to Cyril (praising the princess Olga),

we also find traces o f a peculiar literal principle.11

8 Cf. in his Sermon on the Entry into Jerusalem: Но сдъ же слово окративше,

ггьсньми, яко цв-Ьты, святую церковь въньчаем и праздник украсим (cit. ed. Eremin

1957,411).

9 A probable consequence is that Cyril, in accordance with Byzantine practice, composed

the music of the kanon as well. This would make him the first Russian composer known by

name.

■

10 Unfortunately published only with standardised spelling from a 14th-C MS (Makarij

1995 [1868], 363-365, 594-597). Cf. Mathiesen 1971, 196, where a second 1490 MS is

signalled.

I

11 In four out of eight odes the heirmos and the first troparion open with (nearly) the same

lexeme: величаваго-величіе, дръжавною-дръжав'ною and so on; in yet another ode the

first three stanzas open with the letter ‘П’ (cf. ed. Nikol'sky 1907). This organisation was

established by Spasskij (1949, 130f; cf. Hannick 1973,156f).

An Alphabetical Hymn by St. Cyril o f Turov?

119

Scando-Slavica, T om us441998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

20

13

4.1.3

Penance, покаяние, is the overriding theme in Cyril’s liturgical

production, as may be expected from an old anchorite and stylite. As Maka-

rij (1995 [1868]), Golubinskij (1901), Mathiesen (1971) and others have

noted, KM is emphatically penitential, ‘покаянный’, and Cyril’s prayers

are imbued with regret, penance and fear of the fire of Gehenna and the Last

Judgement.12

4.2

Taken together, particulars in Cyril’s writing and traits in the title of

KV support the explicit attribution of the Life. It has often been noted in

works on Cyril that this hymn has disappeared without a trace. At this point

in our inquiry, we must ask ourselves if this is correct or if KV can be iden

tified as an extant text.

5.1

One of the oldest surviving Slavic alphabetical poems is theAzbuka

pokajal'naja (henceforth: AP),13 known in its oldest form from an East

Slavic Horologion (Часослов) from the second half of the 13th C.14 Part

of this MS (ff. 154r-207r) consists of prayers after Vespers, six of which

are attributed to Cyril (the last one on ff. 194r-201v), followed by AP (ff.

207r-210r). A total of 18 prayers attributed to Cyril are found for the first

time in this MS. The monastic regulation commentaries (ustavnye prime-

canija) contained in the codex led Speranskij to conclude that Cyril himself

must have taken part in the compilation of its set of texts.15

It has been established that AP is directly dependent on AM in its par

ticular alphabet row as well as in textual borrowings (Olof 1973,5ff; Zykov

1974, 311). Just as with AM, AP was originally written in dodeca-syllabic

verse by a writer who still pronounced the old weak jers (Sobolevskij

1910).16 It is still commonly believed that AP is a South Slavic composition

but, as Zykov remarks, one cannot exclude the possibility of its being Old

12 They have been characterised as: “горячія моленія тяжкаго гръшника, сознающаго

свою крайнюю студность и всеокалялость и взывающаго къ Богу или Его небес-

нымъ предстателямъ о непреданіи врагу, о избавленіи оть геены и о сподобленій

рая. По тону своему онъ напоминаютъ молитвы предъ причащеніемь [і. е. молитвы

покаянныя, А. Р-М]” (Golubinskij 1901,840f).

13 Also known as Jaroslavskij azbukovnik. For a survey of the literature, see Olof 1973,

4ff; Zykov 1974, 310f. For MSS, cf. Droblenkova 1972. Ed.: Sobolevskij 1910 (cf. list in ’

SK, p. 322); a number of editions of late MSS with the text are also extant.

14 JaMZ, No 15481 (= SK 387), ff. 207r-210r.

^

15 Speranskij apud Eremin (1955,365), who does not rule out the possibility. (Speranskij’s

view is shared by Rogacevskaja (1993,12f), who is preparing a critical edition of Cyril’s

prayers. 1 am grateful to Ingunn Lunde for drawing my attention to this work.) Speranskij

was also of the opinion that the codex itself originated from southern Russia (see SK, p.

322); this finds some support in Ivanov 1995,12,28.

16 Speranskij (1910, 2ff) and Jakobson (1923, 354—356 with an “Old Bulgarian” recon

struction) dated it to the very early South Slavic period.

120

Alexander Pereswetoff-Morath

Scancfo'Skivica, Tomus 44 1998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2013

An Alphabetical Hymn by St. Cyril o f Turov? 121

Russian, especially in view of the fact that it is known exclusively from East

Slavic MSS (Zykov 1974, 311). One must also keep in mind that syllabic

poetry was recognised in Kievan Russia.

5.2

In Cyril’s Life, the lost kanon is called каиКт* великім, which is

one of the traditional names (ό μέ-γας κανών) of the most voluminous of

all kanons, written by St. Andrew of Crete and performed during Great

Lent. Its character is clearly penitential and in 12th-C Russia, at least, it was

also known as кан[унъ] пока[я?]н[ыгь] (cf. 5.3.2). Great Lent, like all pe

riods of fasting, is particularly marked by penitence. The words kůnSntv ве

ликій ш покйАыии imply some kind of association with ο μ έγ α ς κανών

in theme, construction or liturgical application.17

5.2.1 In attempting to identify KV with AP, we find obvious support as

well as striking complications in the kanon tradition. First, there are many

indications that AP had a hymnic function in a liturgical context— private

or communal: a) In the oldest MS, a Horologion, AP is found after a series

of prayers after Vespers, b) We know that the амй of the immediately pre

ceding prayer is directly followed by the words ггЬмиге томоу and the title

of AP, а^ъБоуковыикъ (cf. SDJa, 1:77). With no manuscript and no exact

context, the words

πϊνμ ιε

томоу

cannot be properly interpreted, but they

nonetheless strengthen the link with liturgical singing, c) In an Old Russian

text, where verse is not expected, the very regular syllabic form of AP im

plies a hymn, supported stanza after stanza by a melody, d) AP refers to it

self as MOAEEbNdia ntCNb: Юже коньчевая молебную пЪ снь,/ въпию к

тебъ, святая Троице (АР, line 67, cit. ed. Sobolevskij 1910) and we note

that rrtCNb is the prevalent Slavic term for the odes of the kanon.

5.2.2 Apart from these general traits, AP may be satisfactorily linked to

the kanon tradition. Its opening section is closely related to the sixth heir-

mos of a translated kanon in the eighth tone, known from Russian heirmos

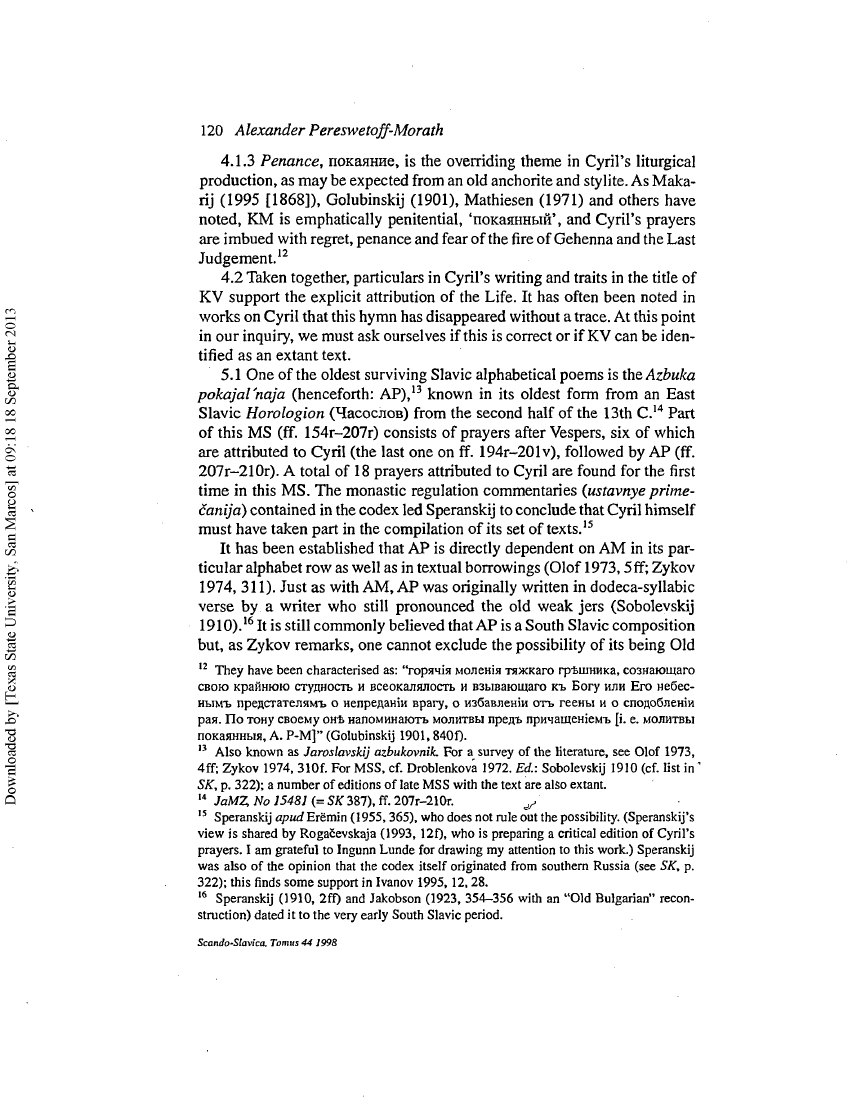

books, Heirmologia (Ирмологии), from the 12th C. Compare:

Азъ тебе припадаю, милостиве,

едкржима приими

μ α ·

милосьрдє*

гр-Ьхы многыми одержимь.

грЪхъми мъмогыими· и

припадаюша къ фЕдротамъ ти·

(АР, lines 1 -2 )18

(heirmos from the sixth ode).19

17 I will not enter into a discussion on the liturgical function of the texts treated in this

paper, as this would require expertise in the field of historical liturgies, a considerable

number of unavailable MSS and liturgical books for comparison, as well as a diplomatic

edition of JaMZ No 15481. I can only suggest some possibilities and present a small

number of texts for comparison.

.

18 Here and henceforth cit. ed. Sobolevskij 1910,13 ff.

19 Here and henceforth cit. ed. Koschmieder, 1: 286.

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

20

13

Note the fairly close resemblance to passages from other heirmoi in the

eighth tone from the same Heirmologion, e. g.: Десницю ми простри,

милостиве, / якоже Петру волнами грузиму (АР, lines 9-10) and ыъ

СйЛУЬ Кр^ЬПТіКОуМ·· р о у к о у М И п р о с г ь р и · ІйКО П е т р о в и И ИС Т к Л А БО Ж Е

м о и

в ъ

^

в е д и

m á

·:·, or affinities such as: Буря мя гръховьная по-

тапляїєть (АР, line 3)

----Е Е ^ Д Ь Ы й r p 't y O K L N i · и п р Е г р * Ь ш Е ы и и Б О у р А

m á съмоуфакть.. Without a thorough study of an extensive sample of texts

it is impossible to determine exactly how related material was borrowed.

The composition of a kanon is characterised, musically and textually, by

the inclusion of components (centons) from other hymns; at the same time

this basic material is often already at hand in the biblical canticles or in oth

er religious texts. I do not propose to trace the exact influences, only to

point out their existence.

There seems to be a clear connection between AP and the sixth ode of

the kanon (modelled on Jonah’s prayer from the belly of the fish) as it was

known in Kievan Russia;20 however, the fact that AP repeatedly returns to

Jonah’s prayer presents us with a problem.21 AP is a sincere and well-

wrought hymn which flows naturally from its first line, the tone remains un

altered throughout the text and the vocabulary is homogeneous. While all

o f this befits a penitential hymn, it shows that AP does not embrace a kanon

in its entirety. (I have observed no unmistakable parallels to formulas from

odes other than the sixth.) Thus, in spite of the kanon connection, AP is not

a complete kanon, nor can it be a “digest” from one. The remaining alter

natives would seem to be that the hymn consists of one single ode or that it

is connected with the kanon in a less formal way.

5.3.1

Identifying AP as the sixth ode of a kanon would entail a great

many complications.22 One would have to operate with troparia of excep

tional length or number, and there would be no suggestion in the ode of the

all-but-obligatoiy stanza to the Mother of God (theotokion) (the end of the

hymn might possibly be interpreted as a triadikon, however). In order to ex

plain the length of the hymn one might look for a kontakion and an oikos,

the hymns that usually accompany the sixth ode (cf. Wellesz 1961, 240ff; ’

cf. e. g. KM), but this, as well, would give rise to several problems. The fact

20 While all of the oldest known Heirmologia MSS are East Slavic, the Heirmologion sup

posedly belongs to the first generation of South Slavic translations (Hannick 1978b, 76-89;

on the translation, cf. Koschmieder 1952-55 2:45-61, esp. 60).

21 Cf. for example the line: Избави мя изъ глубины грЪховьныя, / якоже Иону отъ

кита, Христе (АР, lines 19-20), with many parallels in the kanon tradition.

22 An entire alphabetical acrostic would be exceptional in one single ode; only one Byzan

tine example, ingeniously composed, seems to be known (Wellesz 1961,199ff).

122

Alexander Pereswetoff-Morath

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 44 1998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2013

is that we cannot at present fit the hymn into any stanzaic pattern whatso

ever. We can point out the problems, but not the solutions. If we are to see

in AP a regular section of a kanon, it is characterised by great originality

and ambitions of creating a grand hymnic form, in which case we must sup

pose that the remaining parts of the kanon are lost or as yet unidentified.

5.3.2

Rather, I would suggest that AP is a hymn intended to be sung in

connection with the kanon, although it is not part of the kanon proper. I

would like to suggest a possible source of inspiration for an alphabetical

hymn connected to a penitential kanon in Kievan Russia, which may well

have exerted an influence on AP regardless of whether or not it is a regular

ode. In a Russian Lenten Triodion (Постная Триодь) from the 12th C,

containing the Great Kanon of St. Andrew (here named ка· пока·! Cf. 5.2),

the kanon is followed by стир· то* ка· по грьчьскоумоу· по глймъ·:·

а'^ЪБоуковьи23— 24 stichera, hymns written in the original Greek as an al

phabetical acrostic, the memory of which has been preserved in the Slavic

title. Unfortunately, I have not been able to examine these stichera directly

but it is nonetheless noteworthy that in an alphabetical hymn “belonging”

to the classic Great Penitential Kanon, we find a title o f that same excep

tional construction which we have already registered in Cyril’s Life (кл-

великТй ш поклаыии [...] к гоу по глава л^вХки) and which has

another parallel in Metropolitan John’s Kanon for Boris and Gleb (see 3.3;

4.1.1) but apparently nowhere else.24 My identification would locate them

all in 1 l-12th-C Russia. Even though the perfect coherence of AP makes it

improbable that it was intended as a collection of stichera— these were

normally sung separately during liturgy— it would appear, given the form

of the title and the connection with the Penitential Kanon, that a Slavic

writer, having come into contact with the alphabetical stichera, has been in

spired to compose A P— a hymn corresponding in part to the kanon tradi

tion, constructed as an alphabetical acrostic. A model for a Slavic

alphabetical poem was available and, in fact, known to him in AM;

Andrew’s kanon, too, may have played a role, as well as contemporary pen

itential prayers and possibly Greek alphabetical kanons.

5.4.1

As a first step in applying the title каыКыъ

ееликш

ш

покл

/А

ыии

[...] к гоу по

гллел

д^в&ки to АР, I have demonstrated the presence of an

influence from the kanon tradition (possibly the клыХыъ

велик

Т

и

).

Apart

23 “Stichera to that kanon, in Greek according to the heads [or: chapters?] of the alphabet”.

Cit. apud Gorskij and Nevostruev 1869,506.

24 In his extensive investigation into the Slavic names of acrostics, Hannick (1973,162) is

aware of only the third of these instances and writes: “Der Ausdruck po glavarm. in der

Überschrift [...] bleibt bisher einzigartig, obgleich durchaus verständlich”.

An Alphabetical Hymn by St. Cyril o f Turov?

123

Scando’Slavica, Tomus 44 J998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity

,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2013

from that, we have seen that AP, line after line, follows the Slavic alphabet

(d^EoyKd); the fact that the theme of the hymn is the penance

(

π ο κ λ ι λ ν ϊ ε

)

of a remorseful sinner is accentuated in almost every line (see 6.3.2); it is

probable that the words

κ r o y

designate the second hypostasis of the God

head,25 and the sinner of AP assuredly addresses Christ (χρπ<τε ten times,

cnace once), notwithstanding the praise of the Trinity in the last quarter of

the hymn. Taken together with the overall kanon connection and the link to

St. Andrew’s Great Kanon, the applicability of the compound title to AP

forms a complex and strong argument for identifying AP (wholly or in part)

with

κ α Ν & Ν ΐ ι

β ε λ η κ ϊ η

ι υ

π ο κ

&

α ν η η

,

which, as I have shown, was very

likely composed by Cyril of Turov.

5.4.2

a) I have suggested that a group of translated alphabetical stichera

provided the inspiration to write AP. These stichera were attached to St.

Andrew’s Great Penitential Kanon, and their title in a Russian 12th-C litur

gical MS is almost exactly paralleled by the title of KV in a form that is oth

erwise practically unknown, b) I have demonstrated a thematic influence on

AP from the sixth ode of the kanon, with a textual dependence upon earlier

translated kanons. c) Quite apart from the specific dependence on the kanon

tradition, many pieces of evidence imply a hymnic function for AP. The

question o f exactly how AP enters into the tradition must, however, be left

unanswered for the time being. If the hymn stands alone and was not taken

from a larger structure, the links to the kanon would nonetheless have been

immediately perceptible to a Russian worshipper such as St. Cyril’s hagi-

ographer or a later copyist of the Saint’s Life. Its author may have plausibly

named it

κ λ ν Χ ν Ί ι β ε λ η κ ϊ η u j π ο κ α ι α ν ϊ η [ . . . ]

κ

r o c n o A o y n o γ λ δ β ο μ Ί ι c a ,-

E&KM

vel sim. or, rather, X ((D)

κ & ν & ν δ β ε λ η κ α γ ο

etc., whence a copyist

might have taken pars pro toto and quite simply called it

κ & ν Χ ν ί ι β ε λ η κ ϊ η

etc. d) I repeat that it has been established that the alphabet row, the dodeca-

syllabic form and certain textual fragments have been borrowed from AM.

6.1

Thus, there seems to be a set of texts underlying AP, all of which are

extant in East Slavic 12th-C MSS (though, it would appear, originally

South Slavic works). We know that AP has come down to us exclusively in ■

’

East Slavic MSS; we know that Cyril of Turov was exceptionally well-

versed in the literature available in Kievan Russia— even the sharpest mod

em critic of Cyril’s originality and abilities as an author admits that he was

“about as erudite as it was possible to be” in Russia with no knowledge of

Greek.26 No other “Kievan” writer— if that is what we are looking for— is

25 Makarij 1995 [1868], 365, even though ro>cnc>Ak. in OCS may occasionally translate

expressions like θεός ττατηρ.

124

Alexander Pereswetoff-Morath

Scartdo-Slavica, Tomus 44 J998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity

,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2013

An Alphabetical Hymn by St, Cyril o f Turov?

125

likely to have composed a text of such complexity (with the exception of

Metropolitan Hilarion whose work, however, does not exhibit Cyril’s char

acteristic contrition).

6.2

In the oldest manuscript with Cyril’s prayers we also find the oldest

version of AP; the last cluster of his prayers concludes five folia before AP.

The MS was copied a century after Cyril’s probable lifetime, but scholars

have argued that Cyril took part in compiling the actual set of texts.

6.3.1 As AP does not deal with things temporal, one can hardly expect

to find any specific historical data in it that would tie the hymn to Cyril. Yet

the penitential theme is highly characteristic for the Saint’s entire liturgical

production. Furthermore, general parallels and common formulas abound

in AP, Cyril’s prayers and his Prayer Kanon (KM). Considering that hymns

and prayers are composed from traditional biblical, patristic and hymnic

material, it is difficult to ascertain if any single parallel is due to direct in

fluence. Nonetheless I wish to point out a whole set o f traits in AP and

Cyril’s liturgical legacy that, to my mind, clearly indicate a common au

thor. (No prayers or kanons have been undisputably attributed to Cyril;

hence single parallels between different works of his are, unfortunately,

particularly tenuous.)27

6.3.2 The first line of AP, which seems to have been inspired by Greek

kanons, bears a remarkably precise resemblance to the first troparion o f the

sixth ode of Cyril’s KM.28 To: А зъ тебе [variant reading: к тобе] припа

даю, милостиве, / гръхы многыми одержимъ (АР) corresponds: А з к

Тобе припадаю, Христе Спасе, прося прощения моих грехов [...] но

яко милостив, даже ми сльзы покаянья (ode 6; cf. the odes 2 ,5 and 8).29

The natural comparison of the hymnic self, the Prodigal son and the publi

can (see AP, line 18, 29) is frequent in the prayers (pp. 239, 315, 319, cf.

pp. 242, 277, 344; ode 8); the entreaty to be delivered from геоны [...]

26 Thomson 1992,209; on the scant knowledge of literary Greek among Old Russian liter

ati, not least of all Cyril, see Thomson 1983; cf. Franklin 1992.

27 In spite of the fact that Cyril is commonly regarded as one of the most important medie

val Russian ecclesiastical writers, no critical edition of his liturgical oeuvre has been pub

lished, which means that falsely attributed texts have not been discarded from his authentic

production (cf., however, note 15.) In a survey of the state of research, Podskalsky (1996,

387) expresses with surprising assurance the view that more than 30 texts are genuine (cf.

Franklin 1991, lxxxi ff).

28 AP is quoted from ed. Sobolevskij 1910; KM from ed. Makarij 1995 [1868] (cf. note

10); Cyril’s prayers from Tschilewskij 1965. References from these editions are given with

line numbers (AP), page numbers (prayers) and ode numbers (KM) in brackets.

29 With variants, азъ (къ) тобъ припадаю constitutes a fairly common component in

Cyril’s prayers (pp. 248,250,254,274 etc.).

ScandO'Slavica, Tomus 44 1998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

20

13

в-Ьчныя (line 23) and Judgement Day has many parallels in Cyril’s prayers

(pp. 247, 256, 316), in which the fear of Gehenna has been pointed out as

an important theme (Golubinskij 1901, 840 f; cf. Podskalsky 1996, 389).

Likewise, we find in AP the theme, characteristic of Cyril’s work,30 of over

coming sleep/evil by nocturnal chanting: Нощью мя на irbmne укрепи, /

тяготу соньную отгнавъ ми (lines 31-32) and: да и нъ пршдущую нощь

необъятъ буду гр’Ьховвымъ [sic] мракомъ и тяжкымъ сномъ, но

укрЪпи мя на полунощное пъше (р. 312); cf.: тяжкой сонь отгнавше

(р. 246). Compare: РуцЬ мои въздЪю к тебе, Христе, / греховными

стрелами уязвенъ (lines 37-38) and: не мини отъ д-Ьтска уязвена

вражьими стрЪлами (р. 304); ибо тЬло злобою уязвихъ, ни руку

въздЪти на высоту (р. 282). Compare common wording such as: избави

[...] черьви неусыпающа (line 24; p. 292) and, especially, ковникъ

дьяволъ (line 25; p. 318)31. Compare how the redemption of king Hezeki-

ah (2 (4) Kgs. xx) is associated with that of Jonah in AP as well as in one

of Cyril’s prayers.32

6.4 In his own creative kanons, Cyril utilised alphabetical symbolism

and other alphabetical/literal patterns. Syllabic verse was in principle

recognised in Kievan Russia and would be compatible with the liturgical

pronunciation which may be inferred for the Saint. But are there any traces

of a syllabic structure in Cyril’s writings?

6.4.1

In an interesting paper on prosody and rhetoric in the liturgical

works of St. Cyril, О. I. Fedotov concludes that the stanzas of KM are too

irregular to be defined as verse, and too regular to be mere accident. In his

view, Cyril “скорее всего относился к канонам как к прозаическим

произведениям [...] и применял для ритмической организации текста

лишь риторические правила” (Fedotov 1986, 32), but his discussion of

the syllabism of the kanon odes involves several complications due to un

certainties about the vocalism of the text. Fedotov has counted the syllables

of a non-diplomatic edition (Makarij) of a MS which is 200 years younger

30 RogaSevskaja (1993, 19) has singled out “тема сна” as central to Cyril’s prayers; in

Cyril’s works the intermediary state between light and darkness/night and day may be

overcome in two complementary ways: by direct divine intervention or by the subject’s

willingness to give himself over to полоунофиоЕ rrtNiE.

'

31 In its nearly complete corpus of Old Russian (-14th C) MSS, SDJa registers only three

occurrences of the word кс>Екмикъ, only one of them (AP!) together with the word дьа-

еолъ.; in the OCS text corpus the word figures only twice, in neither case with дьАвол-к.

32 Cf. Избави мя изъ глубины грЪховьныя, якоже Иону отъ кита, Христе.

И|езекиины ми слезы даруй (АР, lines 19-21) and: И того ради покаяшя образы

исперва на всгьхъ показа: Иезекию отъ смерти къ животу възврати, Манасно отъ

узъ избави, 1ону изъ чрева китова исторжъ (pp. 318f).

126

Alexander Pereswetojf-Morath

Scando'Slavica, Tomus 44 1998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

20

13

An Alphabetical Hymn by St. Cyril o f Turov? 127

than the presumed author’s text and is separated from it by radical changes

in the syllabic structure of the Old Russian language (and, possibly, by the

disappearance of the consciousness of syllabic poetry). All this would ac

count for the possible disappearance of original words or sections, as well

as the insertion of new ones.33

6.4.2. It is quite obvious that there are stanzas in the published KM

manuscript that deviate substantially in length from the surrounding ones.

It is more important, however, to note the long sets of stanzas which point

to a strong isomorphism in many odes despite their total length. Even Fedo

tov’s syllable count for the stanzas of the seventh ode produces the figures:

6 2 ,6 1 ,6 3 ,6 0 ,6 1 , and for the second ode: 65,58, 56,55,58; the fourth and

the sixth odes, too, are strikingly isosyllabic. One should keep in mind that

in ancient Slavic hymnody minor deviations from the norm seem to be per

missible in each line (cf. Gove 1978, 217); therefore, a few syllables more

or less in a stanza are perfectly acceptable even in a fairly strict syllabic

hymn.34

In view of this, it would be a remarkable feat to produce this compara

tive isosyllabism either by accident, or through rhetorical parallelism.

There is good reason to suspect that Cyril knew and was able to put into

practice the principles of syllabic verse.35

?

7.1 In this paper I have been able to present a circumstantial case only.

I have set forth a) several arguments implying that the Alphabetical Great

Penitential Kanon mentioned in a redaction of the Life of St. Cyril of Turov

was in fact written by Cyril; b) several arguments implying that this kanon,

or rather part of it, is identical with an alphabetical hymn, Azbuka poka-

jal'naja, which is known from a Kievan (?) 13th-C MS containing several

works by Cyril and possibly compiled by him as well; c) several arguments

which, quite apart from the discussion o f the Great Kanon, suggest that the

hymn was written by Cyril (thematic, textual and structural parallels; the

inclusion of AP in JaM Z 15481). I have pointed out a possible source of in

spiration as well as a typological parallel for the hymn in some alphabetical

stichera attached to the Great Penitential Kanon of St. Andrew of Crete in «

an East Slavic MS; I have also shown that the hymn appears to be themat

ically and textually modelled on translated kanons, available in Kievan

33 It is clear from the deformed acrostics given by Spasskij that kanons were in no way

exempt from such corruption. Another source of error in Fedotov’s operations may be

some doubtful phonetic interpretations of Old Russian jers and

h

in certain positions.

34 In contrast to modem practice, both heirmoi and troparia were actually sung in Kievan

Russia (von Gardner 1980,43 f).

f

33 Bylinin (1988, 34) reports, interestingly, some syllabism in a prayer by Cyril.

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 44 1998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

20

13

Russia. It is already known that the form of the hymn was in part borrowed

from a South Slavic alphabetical poem. All of these texts were available in

the 12th-C Russia of St. Cyril. It is uncertain whether the hymn consists of

a kanon ode or whether it is only loosely connected with the kanon, but the

latter alternative seems to be the more likely one. In that case it is quite con

ceivable that the kanon proper, to which the hymn was attached, should be

Cyril’s Prayer Kanon, in which we find some textual similarities as well as

a certain alphabeticism. Together they may have been intended as a Slavic

counterpart of the μ έ γ α ς κανών of St. Andrew.36

7.2

If accepted, my identification entails certain consequences for the

history of early medieval Russian literature, namely that syllabic poetry

and alphabetical texts were actually written in Kievan Russia: The first phe

nomenon has otherwise been demonstrated in original East Slavic texts

from the 16th/17th CC only, the second from the 15th C only, although both

have occasionally been suspected to be older. It may also indicate some

new aspects of the Russian recension of Byzantine culture as the alphabet

ical hymn has several interesting traits which reflect a creative attitude in at

least one talented writer towards the given tradition of (South) Slavic hym-

nody, though still in line with Byzantine tradition. The features I have dem

onstrated in the kanon writing of St. Cyril may be explained by Slavic

sources, but are still easier to explain if we assume that the author was also

versed to some extent in Greek sources and had some first-hand experience

o f Greek hymnody.

A bbreviations

A M

Azbučnaja molitva

AP

Azbuka pokajal'naja

■

JaM Z

Jaroslavskij istoriko-architektumyj muzej-zapovednik

KM

Kanon" m oleben''

KV

Kanun" velikii

SK

Svodnyj katalog slavjano-russkich rukopisných knig, chranjaščichsja v

SSSR. X I-X IIIw .,

Moscow 1984

SDJa

Slovar'drevnerusskogo jazyka (XI-XIV

vv.), 1-, Moscow 1988-

SORJaS Sborník Otdelenija russkago jazyka i slovesnosti Imperatorskoj Akademii

Nauk

TODRL Trudy O tdela drevnerusskoj literatury

36 Cf. Matiesen’s (1971) observations on the similarities between KM and St. Andrew’s

kanon and on the probability that KM was sung during Great Lent. It seems improbable

that KM alone should be the penitential hymn specifically referred to in the Life as com

posed Π* ΓΛΔΒΔ A^eXkH.

128

Alexander Pereswetoff-Morath

Scando'Slavica, Tomus 441998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2013

An Alphabetical Hymn by St. Cyril o f Turov?

129

L iterature

Abramovic. D. I. 1916: Zitija svjatych mucenikov B orisa i G ieba i slu zby im

(= Pamjatniki drevne-russkoj literatury 2), Petrograd.

Bylinin, V. K. 1988: “K probleme sticha slavjanskoj gimnografii (X -X III vv.)”,

Slavjanskie literatury: X m eidunarodnyj s~ezd slavistov. Sofija, se n tja b r'

1988 g. Doklady sovetskoj delegacii, 33-51, Moscow.

Droblenkova, N. F. 1972: “Bibliografiöeskaja popravka k XXVII tomu PSRL”,

TODRL 2 7 ,4 5 8 -4 6 0 .

Eremin, I. P. 1955-1957: “Literaturnoe nasledie Kirilla Turovskogo”, TODRL 11,

13, 3 4 2 -3 6 7 ,4 0 9 -4 2 6 .

Fedotov, 0 . 1 . 1986: “O ritmiöeskom stroe pamjatnikov drevnerusskoj gimnografii

kievskogo perioda”, in: L iteratu ra D revnej R usi: M ezvu zovskij sborn ik

naucnych trudov, 19-34, Moscow.

Franklin, S. 1991: “Introduction”, Sermons and Rhetoric o f Kievan Rus': Trans

lated and with an Introduction by Simon Franklin, xiii-cix (= Harvard Library

o f Early Ukrainian Literature: English Translations 5), Cambridge, Mass.

---------- 1992: “Greek in Kievan Rus'”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 46, 69-81.

von Gardner, J. 1980: Russian Church Singing I, Orthodox Worship and Hymno-

graphy, Crestwood.

Golubinskij, E. 190l:Istorija russkoj cerkvi 1:22, Moscow.

Gorskij, A. and K. Nevostruev 1869: Opisanie slavjanskich rukopisej Moskovskoj

sinodal'noj biblioteki 3:1, Knigi bogosluzebnyja, Moscow.

Gove, Antonina F. 1978: “The Evidence for Metric Adaption in Early Slavic Trans

lated Hymns”, in Hannick 1978a, 211-246.

Hannick, C. 1973: “D ie Akrostichis in der kirchenlavischen liturgischen D ich

tung”, Wiener slavistisches Jahrbuch 18,151-162.

---------- (ed.) 1978a: Fundamental Problems o f Early Slavic Music and Poetry

(= Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae. Subsidia 6), Copenhagen.

---------- 1978b: “Aux origines de la version Slave de l ’Hirmologion”, in Hannick

1978a, 5-120.

Ivanov, V. V. (ed.) 1995: Drevnerusskaja grammatika XII-X1II vv., Moscow.

Jakobson, R. 1923: “Zametka o drevne-bolgarskom stichoslozenii”, Izvestija Ot-

delenija russkago jazyka i slovesnosti Rossijskoj Akademii Nauk 24, 351-358.

---------- 1985a: “The Slavic Response to Byzantine Poetry” [1963], in Selected

Writings 6:1, 240-259, Berlin - New York - Amsterdam.

---------- 1985b: “Sketches for the History o f the Oldest Slavic Hymnody: Com

memoration o f Christ’s Saint and Great Martyr Demetrius”, in: Selected Writ

ings 6:1, 286-346, Berlin - New York - Amsterdam.

Koschmieder, E. 1952-55: D ie ältesten Novgoroder Hirmologien-Fragmente 1-2

(= Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philoso

phisch-historische Klasse N. F. 35, 37), Munich.

Krumbacher, K. 1897: Geschichte der byzantinischen Litteratur von Justinian bis

zum Ende des oström ischen R eiches (52 7 -1 4 5 3 ) (= Handbücher der klas

sischen Altertums-wissenschaft 9: l 2), Munich.

Kuev, K. M. 1974: Azbucnata molitva v slavjanskite literaturi, Sofia.

Makarij (Bulgakov) 1995 [1868]: Istorija russkoj cerkvi, t. 2, Moscow.

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

D

o

w

n

lo

ad

ed

by

[T

ex

as

St

at

e

Un

iversity,

Sa

n

M

ar

co

s]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

20

13

130

Alexander Pereswetoff-Morath

[Mathiesen] Mat'esen, R. 1971: “Tekstologičeskie zamečanija o proizvedenijach

Vladimira Monomacha”, TODRL 26, 192-201.

N ikol'sky, N. K. 1907: “Proložnoe žitie Kirilla, episkopa Turovskago”, in “Mate-

rialy dlja istorii drevnerusskoj duchovnoj pis'm ennosti. №№ I-X X III”,

SORJaS, 82, 62-64.

Olof, K. D. 1973: Philologische und literarische Aspekte slavischer Alphabets-

akrostichis nebst einem Exkurs über die slavischen Buchstabennamen, Am

sterdam.

Pereswetoff-Morath, A. I. 1994: Vadprofeterna sagt...: En undersökning av ett

Tolkovaja azbuka (= Lunds universitet. Slaviska

I n s tit u tio n en .

Exam ens-

uppsatser 2), Lund.

[Podskalsky] Podskal'ski, G. 1996: Christianstvo i bogoslovskaja literatura v

Kievskoj Rusi (9 8 8 -1 2 3 7 gg.) (= Subsidia Byzantinorossica 1), St. Petersburg.

Rogačevskaja, E. B . 1993: M olitvoslovnoe tvorčestvo Kirilla Turovskogo (problé

my tekstologii i poětiki), Avtoreferat dissertacii na soiskanie učenoj stepeni

kandidata filologičeskich nauk, Moscow.

Sobolevskij, A. I. 1910: “Drevnija cerkovno-slavjanskija stichotvorenija IX -X ve-

kov”, His: “Materialy i izsledovanija v oblasti slavjanskoj filologii i arche

ologii”, SORJaS 88, 1-35.

Spasskij, Th. G. 1949: “Akrostichi i nadpisanija kanonov russkich minej”, Pravo-

slavnaja mysl'. Trudypravoslavnago bogoslovskago instituta v P artie 7, 126—

150.

[Steensland] Stensland, L. 1997: “Byl li Pskov mestom roždenija russkogo žanra

tolkovych azbuk?”, in [J. I. Bj0mflaten] Ja. I. B'ernfiaten (ed.), Pskovskie gov-

ory: istorija i dialektologija russkogo jazyka, 164-171, Oslo.

Suchomlinov, M. I. (ed.) [1858]: Rukopisi grafa Alexija Uvarova, t. 2, Pamjatniki

slovesnosti 1, St. Petersburg.

Thomson, Francis J. 1983:“Quotations o f Patristic and Byzantine Works by Early

Russian Authors as an Indication o f the Cultural Level o f Kievan Russia”,

Slavica Gandensia 10, 65-102.

---------- 1992: “On Translating Slavonic Texts into a Modem Language, Together

with a Translation o f Luke o f Novgorod’s Homily to the Brethren”, Slavica

Gandensia 19, 205-217.

Tschižewskij, D. et al. (ed.) 1965 : K irill von Turov: Gebete: Nach der Ausgabe in

„ Pravoslavnýj Sobesednik" 1858 (= Slavische Propyläen: Texte in Neu- und

Nachdrucken 6), Munich.

Uspenskij, B. A. 1997: “Russkoe knižnoe proiznošenie XI-XII vv. i ego svjaz' s

južnoslavjanskoj tradiciej. (Čtenie erov)” [1988], in Izbrannye trudy 3, O b šč ee"

i slavjanskoe jazykoznanie, 143-208, Moscow.

W ellesz, E. 1961: A H istory o f Byzantine Music and Hymnographyl, Oxford.

W eyh, W. 1908: “D ie A krostichis in der byzantinischen K anonesdichtung”,

Byzantinische Zeitschrift 17, 1-69.

Zykov, É. G. 1974: “Russkaja peredelka drevnebolgarskogo stichotvorenija”,

TODRL 28, 308-316. '

Scando-Slavica, Tomus44 1998

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

The Way of Perfection by St Teresa of Avila

comment on 'Quantum creation of an open universe' by Andrei Linde

Folklore as an Historical Science by Gomme

Kundalini An Occult Experience by GS Arundale previously ed 1938 (2006)

Avant Garde and Neo Avant Garde An Attempt to Answer Certain Critics of Theory of the Avant Garde b

AN OCEAN APART by Sammy Goode

Majewski, Marek; Bors, Dorota On the existence of an optimal solution of the Mayer problem governed

算盤 Abacus Mystery of the Bead The Bead Unbaffled An Abacus Manual by Totton Heffelfinger & Gary F

Catena Aurea The Gospel Of Mark A Commentary On The Gospel By St Thomas Aquinas

The Enigma of Survival The Case For and Against an After Life by Prof Hornell Norris Hart (1959) s

The Personal Correspondence of Hildegard of Bingen Selected Letters with an Intro & Comm by Joseph

THEORY AN INTERMEDIATE TEXT by David Friedman

Charging an Enochian Tablet by Benjamin Rowe

An Alchemical poem by Thomas Rawlin

Pritsak An eleventh century turkic bilingual (turko slavic) graffito from the St Sophia cathedral in

Interruption of the blood supply of femoral head an experimental study on the pathogenesis of Legg C

Pancharatnam A Study on the Computer Aided Acoustic Analysis of an Auditorium (CATT)

Chambers Kaye On The Prowl 2 Tiger By The Tail

więcej podobnych podstron