the world of jazz, it’s often flamboyant

soloists who garner the most attention.

But it’s the rhythm section—the bass

and drums—who make things

really

swing. On gigs where there are no bass and drums, the

guitarist is expected to be the virtual rhythm section. One

cool way to make the groove happen is to strum four-

chords-to-the-bar, à la Freddie Green. But to get things

seriously cooking, you’ll need to lay down bass lines

yourself, and add rhythmic punctuation with well-placed

chordal and melodic counterpoint. ■ How can one

player do the physical and creative work of two? With

practice and persistence, it

is possible to simulate a mini-

ensemble. In this lesson, we’ll work through the basic

secrets

of

the

walking

bass

to jazzy comping

In

by adam levy

a beginner’s guide

basic steps of building a hardy bass-

and-chords groove. First, we’ll iso-

late the essential skills, and then

we’ll merge these elements to create

a solid, swinging accompaniment.

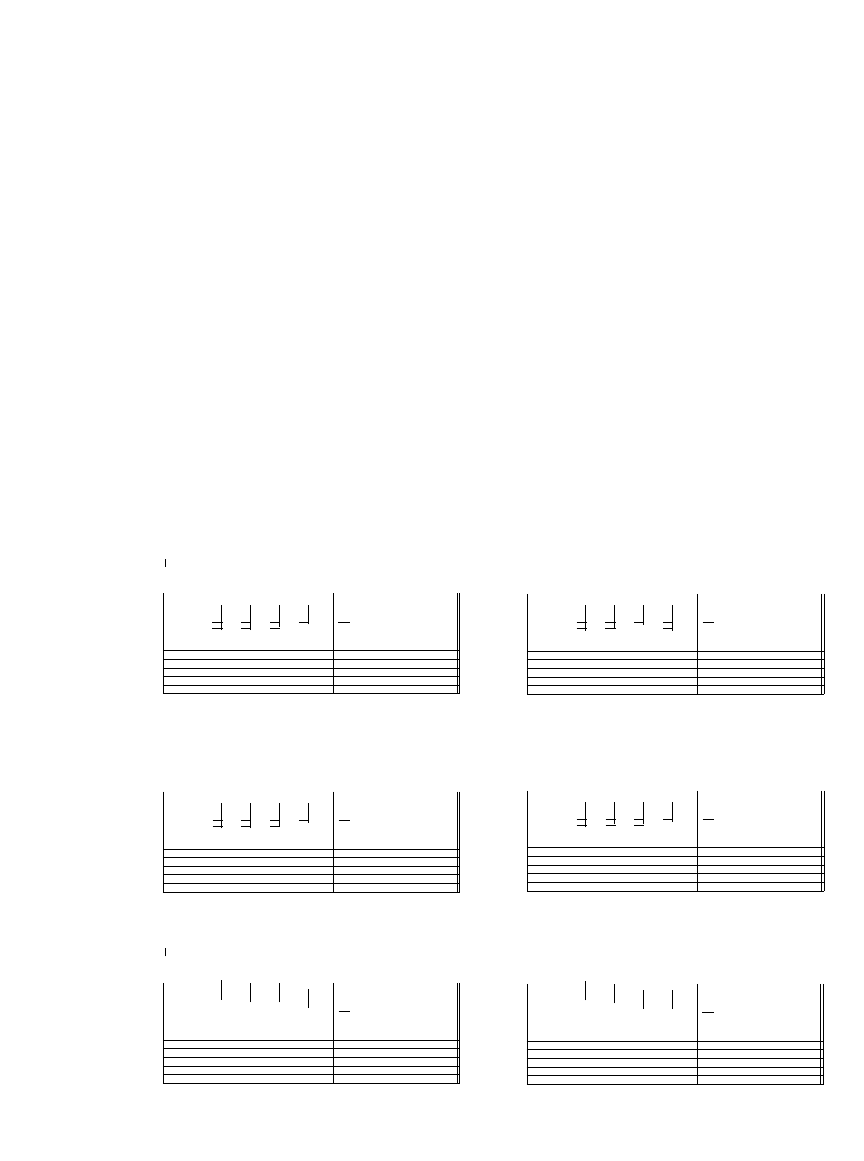

Baby Steps

Let’s start with a simple, two-

measure chord progression—G7-

C7—and the most elementary bass

line that will get us from the root

of the first chord (G) to the root of

the second (C) using scalewise mo-

tion. Jazz bass lines are typically

rendered in steady quarter-notes,

so if we walk an upward line from

one root to the other (beat one, bar

1 to beat one, bar 2), we’ll have to

account for five notes: G, x, x, x, C.

Stepping up through the appropri-

ate scale for G7—G Mixolydian—

we only have four notes (G, A, B,

C). This means we’ll either have to

repeat a note (Examples 1a and

1b) or add a chromatic passing

tone (Examples 1c and 1d). Any of

these solutions is fair play.

Walking downward from G is

simpler, because there are just

enough scale tones to fit—G, F, E,

D, C. But you can still add chro-

maticism if you like, as shown in

Examples 2a and 2b.

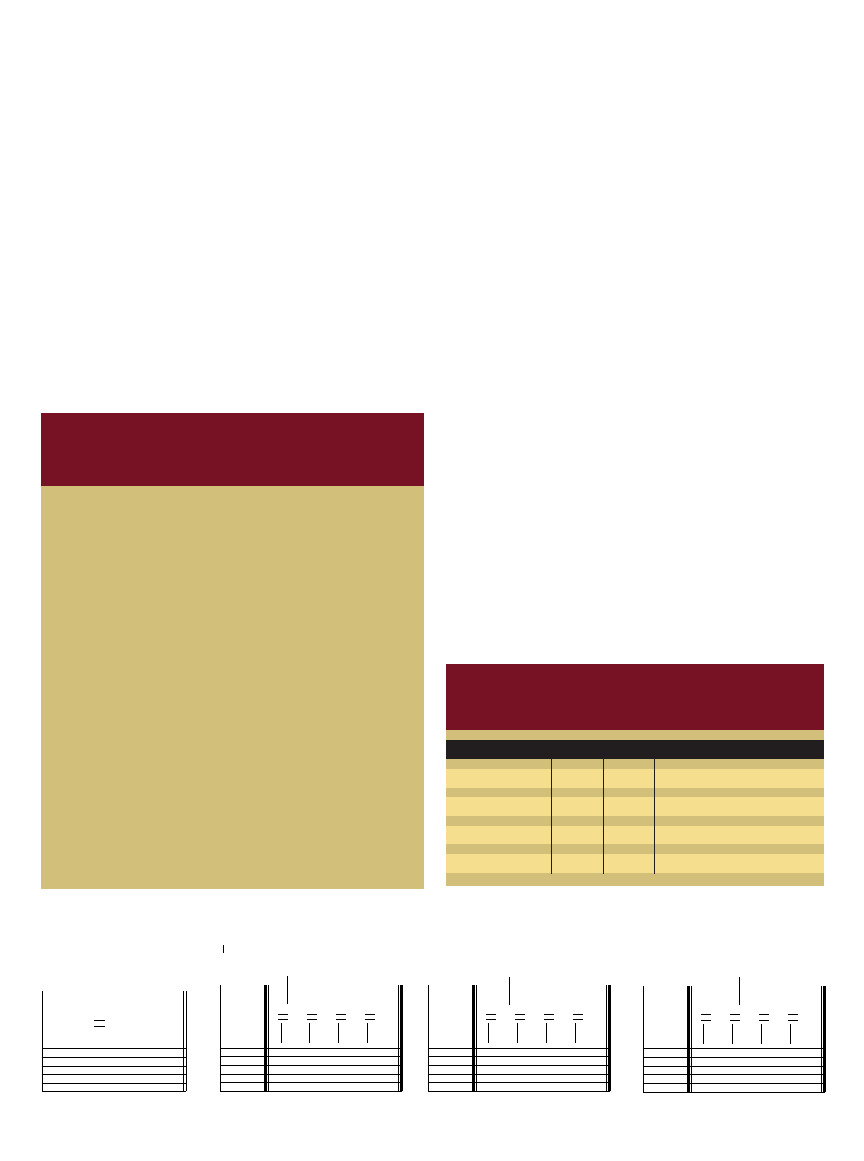

Adding Harmony

and Rhythm

The next step is to add harmo-

ny. Here, the job is to outline a pro-

gression’s essential harmonic con-

tent. Of course, on any given beat,

one fretting-hand finger will be

tied up with a bass note, so your

chord palette will be limited to

two- and three-note voicings. Giv-

en such restrictions, the best bet

is to play a chord’s 3 and 7, which

are its definitive tones. On G7, for

example, laying down F and B (the

b7 and 3) above the G bass gives

our ears enough information to

infer G7 (Ex. 3). For other chord

types, use the appropriate 3 and 7

(see table, Definitive Chord Tones).

Now, we could simply let the

chord’s 3 and 7 ring out as whole-

notes, but half the fun lies in

adding syncopated chordal punch-

es to create a swinging feel. The

simplest way to do that is to in-

clude one eighth-note punch per

measure. To practice this, repeat

a one-measure phrase using G7,

and place a chord punch on the

first eighth-note of the measure

(Ex. 4a). Note: Treat all eighth-note

rhythms in this lesson as “swing”

eighth-notes.

Next, shift the punch to the

second eighth-note of the measure

(Ex. 4b), then the third eighth-note

of the measure (Ex. 4c), and so on,

until the punch is on the eighth

eighth-note (the and of beat four).

Make sure to work on this punch-

over-bass concept at a variety of

tempos, from 72 bpm to 200 bpm.

You can make this exercise even

more interesting by repeating a

two-measure phrase, which gives

you eight more possibilities for the

eighth-note punch.

Once the basic one-punch-

per-bar groove starts feeling good,

it’s time to tackle more complex

rhythms. Examples 5a and 5b put

two common jazz-comping

rhythms to work.

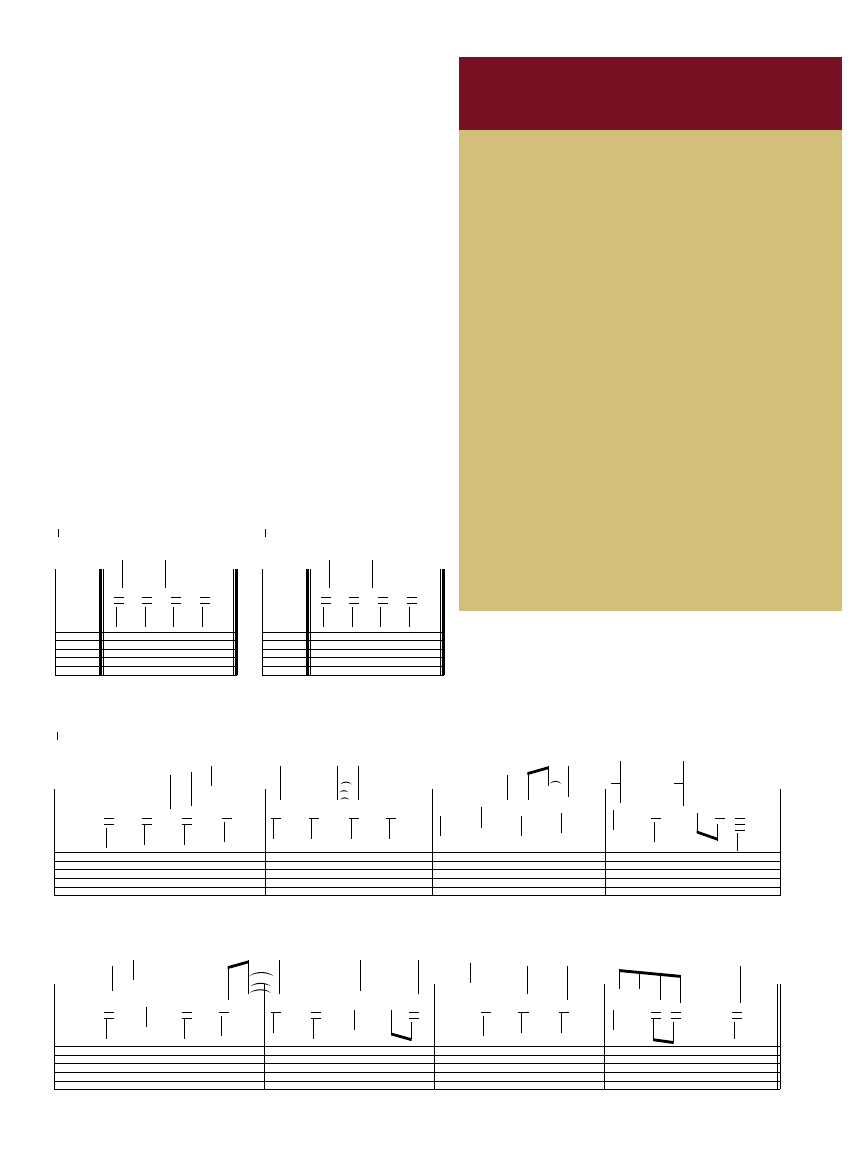

Use Your Illusion

Once you’ve made nice with

the previous examples, it’s time to

move on to the final step—putting

it all together. The bluesy, eight-

measure etude (Ex. 6) combines

all the points we’ve discussed, and

offers a few extra goodies. Pay

close attention to the left-hand fin-

gerings, as some of the chords—

particularly C9 in bars 5 and 6—are

nearly impossible to sustain for

their full value without using the

suggested fingerings.

Notice how the rhythmic

chordal phrasing in bars 3 and 4

mimics the phrase in bars 1 and

2. Such symmetry makes comp-

ing musical, and not just a series

of random eighth-note punches.

=============

=

T

A

B

&

# 44

ö ö ö ö

w

G7

C7

= 72-120

ö

2

2

4 1

3

3

3

5

2

=============

=

T

A

B

&

# 44

ö

ö

ö ö

w

G7

C7

2

2

4 1

3

3

3

5

2

=============

=

T

A

B

&

# 44

ö ö ö ö

w

G7

C7

2

2

4 1

3

3

5

2

#

4

3

=============

=

T

A

B

&

# 44

ö ö

ö

w

G7

C7

2

2

4

1

3

3

5

2

ö#

1

1

Ex. 1a

Ex. 1b

Ex. 1c

Ex. 1d

=============

=

T

A

B

&

# 44

w

G7

C7

3

ö ö ön ö

3

3

2 1

1

5

4

3

5

= 72-120

ö

=============

=

T

A

B

&

# 44

w

G7

C7

3

ö ön ö öb

3

3

1

1

2

5

5

3

4

Ex. 2a

Ex. 2b

Use this concept as you develop

your own bass-and-chord moves.

Work the etude up to speed

gradually, keeping time with a

metronome or beat box. If you can’t

make your bass line and chords

swing at a slow, sultry pace, you

won’t be able to make them swing

at medium or fast tempos. You may

find it helpful to practice the bass

line (downstemmed notes) and the

chord punches (upstemmed notes)

separately before attempting to

play them all together.

To really get into the swing of

things, try setting your time keeper

at half the actual tempo, using its

clicks as beats two and four. As

awkward as this may feel at first,

it’s a tried-and-true method for

improving swing feel by de-em-

phasizing beats one and three,

which are more favorably accent-

ed in rock than in jazz. Make sure

that your two parts (bass and

chords) are balanced musically. To

get the clearest perspective, record

yourself and listen to the results.

Remember, you’re trying to create

an aural illusion, so the bass line

should have the timbre of an up-

right, and the chord punches

should sound like guitar. Whichev-

er instrument you try to emulate,

keep your chords timbrally distinct

from the bass.

Homework

Okay, so you’ve got the basic

moves under your fingers. Now

what? For walking practice, work

on 12-bar blues progressions at

various tempos in several different

keys—including keys that could

easily make use of open-string

bass notes (such as E, A, D, G, and

C), as well as those that are less

likely to include open strings (such

as Bb, Eb, and Ab). When you’re

comfortable walking and comping

through blues progressions, take

a stab at a few simple jazz stan-

dards, such as “Take the A Train”

or “All of Me.” With a little effort,

you’ll soon be able to walk and

chew gum at the same time.

g

======

=

T

A

B

&

# 44

G7

wwn

w

2

1

1

4

3

3

Ex. 3

========

T

A

B

&

# 44

G7

= 72-120

ö

Swing feel

{

..

öjön

ö

ä Î î

{

..

ö ö ö

4

3

3

3

3

3

2

1

1

Ex. 4a

========

T

A

B

&

# 44

G7

{

..

{

..

ä öjön

ö

3

ö

4

3

3

Î î

ö ö

3

3

1

1

2

Swing feel

Ex. 4b

========

T

A

B

&

# 44

G7

{

..

{

..

Î

ö

3

öjön

ö

ä

4

3

3

î

ö ö

3

3

2

1

1

Swing feel

Ex. 4c

here’s more to walking bass than learning a few hip bass

lines. As you’re trying to create an aural illusion, the trick is to

get a timbre that suggests acoustic bass. And to really make

the magic work, you’ve got to pay attention to details. Rule

number one: Do not use a pick—the resulting sound is often point-

ed and plucky. For optimum bass-like attack, use the flesh on your

picking-hand thumb. (That’s

not how bassists do it, but it’s the best

way to approximate their timbre on the guitar.) Your attack should

be quick and sure, but not heavy handed. The last thing you want

is the un-bass-like sound of your strings slapping the frets. (After

all, upright basses don’t

have frets.) It’s also a good idea to exper-

iment with where you locate your picking hand, as different points

along the string create subtle timbral changes. In general, you

want to have your hand a little closer to the nut than usual, with

your thumb hovering near the end of your fretboard.

If you’re an electric player, you’ll want to dial in a clean, clear

tone, with little or no reverb. A guitar with a wooden bridge will

give you the most authentic attack and decay, and for a bona fide

bass vibe, use a set of flatwound strings.

—AL

t

bass tone

chord type

3

7

example

maj7

3

7

Cmaj7 = E (3), B (7)

dom7

3

b7

C7 = E (3), Bb (b7)

m7 (or m7b5)

b3

b7

Cm7 = Eb (b3), Bb (b7)

dim7

b3

bb7

Cdim7 = Eb (b3), A (bb7)

definitive chord tones

================================

T

A

B

&

# 44

G7

= 72-120

ö

Swing feel

Î

ä öjöö ööjö

ö#

ö

ö

ö.

ö

öööb

ö

ö

ä öjöö ööö

ö#

Î

ö

Îö ö

ä öjö öö

ö

öö

ö

ö

ön

ö

öö#

öj

îön À

ö

C9

C dim7

#

G7

F7

E7

1

3

1

1

2

2

1

1

3

4

2

2

4

1

3

3

1

1

2

3

3

1

2

2

1

1

1

3

4

1

1

2

3

3

4

1

2

2

2

3 5

3

3

4

5

5

7

6

8

7

8

8

8

7

8

8

8

9

9 9

10

10

7

9

9

9

10

10

12

12

7

7

8

8

7

7

7

6

7

7

0

1

ä

ööb

ö

================================

T

A

B

&

#

5

öjö#

ö

ö.

ö

ö

Î

ööö ööbö úúú

ö

ö

ö

ö.ö.ö.

ö ö

öjöön

(

)

A7

C9

D7sus

5

5

6

8

7 0

5

5

2

2

3

3

3

3

5

5

5

5

3

0

3

3

5

4

1

1

2

4

3

4

1

1

1

1

3

3

1

4

2

1

1

4

2

ä

Î

ön.

ö

ö

ööb öbö

ö#

ö

ö

öb ööb

öb

öön

ön

Î

Î

öönöö

ö

G13

C7

D

A 7 G7

G13

U

b

4

1

1

1

4

2

3

1

1

3

4

3

2

1

2

4

3

6

2

5

3

3

4

4

5

3

5

6

5

4

4

4

3

3

3

3

2

0

0

öJ ä

1

1

3

Ex. 6

========

T

A

B

&

# 44

G7

= 72-120

ö

Swing feel

{

..

ö

î

{

..

ö ö ö

4

3

3

3

3

3

ö.ön. öjö

4

3

2

1

1

Ex. 5a

========

T

A

B

&

# 44

G7

= 72-120

ö

Swing feel

{

..

ö

î

{

..

ö ö ö

4

3

3

3

3

3

ö.ön. öjö

4

3

2

1

1

Ex. 5b

oe Pass is likely the best known and most extensively recorded

guitarist to feature walking bass lines in his music. His solo

discs on Pablo (including the

Virtuoso series and Montreux

’75) contain numerous examples of high-caliber walking, and

his duets with vocalist Ella Fitzgerald offer further inspiration.

Lenny Breau was another fine walker. Found on

Five O’clock Bells

[Genes], “Little Blues” illustrates his prowess. Tuck Andress—the

fretboard titan in the guitar-and-vocal duo Tuck and Patti—is yet

another master.

Tears of Joy [Windham Hill Jazz] evinces the out-

er limits of walking guitar lines, and

Reckless Precision, his solo

outing on Windham Hill Jazz, is packed with sauntering bass and

rich counterpoint. Of course, nearly any record by 7-string pio-

neer George Van Eps will motivate wannabe walkers. The new kid

on the block is 8-stringer Charlie Hunter, whose approach has

roots in R&B and straight-ahead jazz. You can hear Hunter in full

swing on his mid-’90s Blue Note discs

Bing! Bing! Bing! and

Ready. . . Set. . . Shango!

If you want to go to the low-end source, check out the undis-

puted kings of jazz bass—Ray Brown and Paul Chambers. Brown

made many great records in the ’50s and ’60s as a member of

the Oscar Peterson Trio, and some of Chambers’ finest walking

can be heard on the 1956 recordings

Cookin’ with the Miles

Davis Quintet and Relaxin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet.

—AL

j

the sound of walking

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Mantak Chia Taoist Secrets of Love Cultivating Male Sexual Energy (328 pages)

Exploring the Secrets of the Female Clitoris!

7 Secrets of SEO Interview

Midnight Secrets of Shadow Channeler Spell List

Benefits and secrets of fasting

Dragonstar Secret of the Shifting Sands

Final Secret of Free Energy Bearden

Insider Secrets of Online Poker

21 Success Secrets of Self Made Millionaires

Midnight Secrets of Shadow The Death That Comes in the Night

Secret Of The Academy, Slayers fanfiction, Prace niedokończone

Rucker The Secret of Life

Gopi Krishna Ancient Secrets of Kundalini

MKTG Secrets of the Marketing Masters

Midnight Secrets of Shadow Midnight 2nd Edition Errata

CoC Secrets of the Kremlin

Money Making Secrets of Mind Power Masters

Midnight Secrets of Shadow Shadow Servants

więcej podobnych podstron