ADAD-N?R?R? III'S FIFTH YEAR IN THE SABA'A STELA.

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND

Shuichi Hasegawa

Presses Universitaires de France |

« Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale »

2008/1 Vol. 102 | pages 89 à 98

ISSN 0373-6032

ISBN 9782130570042

Article disponible en ligne à l'adresse :

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

http://www.cairn.info/revue-d-assyriologie-2008-1-page-89.htm

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Pour citer cet article :

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Shuichi Hasegawa, « Adad-n?r?r? III's Fifth Year in the Saba'a Stela. Historiographical

Background », Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 2008/1 (Vol. 102), p. 89-98.

DOI 10.3917/assy.102.0089

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Distribution électronique Cairn.info pour Presses Universitaires de France.

© Presses Universitaires de France. Tous droits réservés pour tous pays.

La reproduction ou représentation de cet article, notamment par photocopie, n'est autorisée que dans les limites des

conditions générales d'utilisation du site ou, le cas échéant, des conditions générales de la licence souscrite par votre

établissement. Toute autre reproduction ou représentation, en tout ou partie, sous quelque forme et de quelque manière

que ce soit, est interdite sauf accord préalable et écrit de l'éditeur, en dehors des cas prévus par la législation en vigueur en

France. Il est précisé que son stockage dans une base de données est également interdit.

Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - - - 109.243.68.227 - 30/05/2015 15h00. © Presses Universitaires de France

[RA 102-2008]

Revue d’Assyriologie, volume CII (2008), p. 89-98

89

ADAD-NĒRĀRĪ III’S FIFTH YEAR IN THE SABA’A STELA

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND

BY

Shuichi H

ASEGAWA

The significance of the Saba’a Stela lies not only in the fact that it is one of the few

inscriptions of Adad-nērārī III (810-783 BCE) but also in its reference to the king's fifth year as

the beginning of his western campaign. Adad-nērārī’s inscriptions are all but summary

inscriptions,

1

and this is the only chronological data mentioned in his inscriptions. This date,

however, has been a matter of debate among scholars, because it does not coincide with other

Assyrian sources. This study offers a new solution that is based on historiographical analysis of

the text.

The Saba’a Stela was discovered in 1905 at Saba’a, south of Jabal Sinjar in north Iraq.

The text on the stela consists of thirty-three lines which are inscribed under an image of the

king and divine symbols. The stela measures 192 x 47 cm (top) / 50.5 cm (bottom), and is in

poor condition.

2

The text of the stela, published by E. Unger, can be divided into seven sections :

3

1)

dedication (ll. 1-5) ; 2) Adad-nērārī III’s genealogy (ll. 6-11a) ; 3) campaign to the land of Hatti

“in the fifth year” (ll. 11b-18a) ; 4) tribute from Mari’ king of Damascus (ll. 18b-20) ; 5)

erection of the statue in Zabanni (ll. 21-22) ; 6) introduction of Nergal-ēreš (ll. 23-25) ; and 7)

curses (ll. 26-33).

Text

1. [ana]

⸢d⸣

IŠKUR gú-gal AN u ⸢KI-tim DUMU

d

a-nim⸣ qar-du šar-⸢hu⸣

2. [gí]t-ma-⸢lu ša⸣ pu-un-⸢gu⸣-lu ku-bu-uk-kuš a-ša-⸢red⸣

3.

⸢d⸣

í-gì-gì qar-rad

d

DIŠ.U šá hi-it-lu-pu nam-ri-ri ra-kib

4. [UD].⸢MEŠ⸣ GAL.MEŠ ha-líp me-lam-me ez-⸢zu⸣-te mu-šam-qit HUL.MEŠ

5. [na-a]-⸢ši⸣ qi-na-an-zi KÙ-te mu-šab-riq NIM.GÍR EN GAL-e EN-šú

6. [

m

10-ÉRIN].⸢TÁH⸣ MAN GAL-u MAN dan-nu MAN ŠÚ MAN KUR aš+šur MAN la šá-

na-⸢an⸣ SIPA tab-ra-te

7. [ÉN]SI MAH šá ni-iš qa-ti-šú ⸢na⸣-dan zi-bi-šú ih-šu-hu

8. [DINGIR].⸢MEŠ⸣ GAL.⸢MEŠ⸣ SIPA-su

4

GIM šam-me TI.LA UGU UN.MEŠ

9. [KUR aš]+⸢šur⸣ ú-⸢ṭí⸣-bu-ma ú-ra-pi-šú KUR-su A

m

šam-ši-10 MAN dan-nu

1. The term “summary inscription” was first suggested by H. Tadmor (1973 : 141). The concept of the term is

similar to that of E. Schrader’s “Übersichtsinschriften” (Schrader 1872 : 130 ; Tadmor, ibid., 141, n. 2).

2. The Stela is exhibited in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum (catalogue number 2828).

3. Unger 1916 ; Donner 1970 : 52-53 (ll. 11-22) ; Tadmor 1973 : 144-48 ; Weippert 1992 : 44, n. 16 (ll. 21-

22) ; RIMA 3, A.0.104.6.

4. W. Schramm (1973 : 112) reads : [DINGIR.M]EŠ GAL.[MEŠ šá

!

] SIPA-⸢su⸣.

Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - - - 109.243.68.227 - 30/05/2015 15h00. © Presses Universitaires de France

90

SHUICHI HASEGAWA

[RA 102

9

0

10. [MAN ŠÚ] MAN KUR aš+šur A ⸢A⸣

m

šùl-ma-nu-MAŠ šá-pir mal-ki PAP-eš mu-šá-pi-ih

11. [MAN].MEŠ KÚR.MEŠ ina MU 5.KÁM <šá>

5

ina GIŠ.GU.ZA MAN-ti GAL-iš

6

12. [ú]-⸢ši⸣-bu-ma KUR ad-ki ⸢ÉRIN⸣.HI.<A>-at KUR aš+šur ⸢DAGAL⸣.MEŠ ana KUR

«hat» hat-te-⸢e⸣

7

13. [a-na] ⸢DU⸣ lu aq-bi ana

8

ÍD pu-rat-te ina me-li-šá e-bir MAN.MEŠ-ni

14. [māt hatte]

9

⸢DAGAL⸣-te šá ina tar-ṣi

m

šam-ši-10 AD-ia

10

id-nin-ú-ma

15. ⸢ik-ṣu⸣-[ru ÉRIN.HÁ.MEŠ]-šú-un

11

ina qí-bit aš+šur

d

⸢AMAR.UTU⸣

12

d

IŠKUR

d

iš-tar

DINGIR.[MEŠ]

16. ⸢tik-lì-ia⸣ [pul]-⸢hu me-lam⸣-mu is-hu-pu-šú-nu-te-ma GÌR.[II.MEŠ-ia]

17. iṣ-ba-tú GUN ma-⸢da⸣-[tú...] x x x [...]

13

18. ana KUR aš+šur ú-ru-ni am-h[u-ur...] [ana KUR ša ANŠE-šú DU]

14

19. lu aq-bi

m

ma-ri-’ ina URU di-maš-qí ⸢lu⸣ [...e-sir-šu...]

15

20. <1>

?

ME GUN KÙ.GI 1 LIM GUN KÙ.BABBAR GUN [...amhur]

16

21. ⸢ina⸣ u₄-me-šú-ma ú-še-piš-ma ṣa-lam be-lu-te-ia li-ta-[at qur]-⸢di-ia⸣

22. [ip]-šet qa-ti-ia ina qer-bi-šú al-ṭur ina AN

17

za-ban-ni

18

⸢ul⸣-[zi]z-šú N[A₄

( ?)

]

19

5. The supplement of <ša> here was first suggested by B. Meissner (1917 : 55).

6. Cf. i-na šur-rat LUGAL-ti-ia i-na mah-re-e BALA-ia ša i-na GIŠ.GU.ZA LUGAL-ti ra-bi-iš ú-ši-bu “in

the beginning of my lordship (and) in my first palû after I sat on the throne in majesty” (Adad-nērārī II, A.0.99.1, ll.

8-9) ; ina šur-rat MAN-ti-a ina mah-ri-i BALA-ia šá ... ina GIŠ.AŠ.TI MAN-ti GAL-iš ú-ši-bu “in the beginning of

my lordship (and) in my first palû after ... I sat on the throne in majesty” (Aššur-naṣirpal II, A.0.101.1, ll. 43-44). The

phrase LUGAL-ti / MAN-ti rabîš appears only in the context of the beginning of a king’s reign. For this reason, S.

Page (1969 : 458) takes it as indication of the co-regency between Adad-nērārī III and Semiramis, his mother.

However, this šá is better understood as “since”, and thus the sentence should be translated “since I sat on the throne

in majesty.” See A. Poebel 1943 : 82, n. 297.

7. After ana KUR, Unger’s copy reads hat-hat-te áš-ud. Schramm (1973 : 112) reconstructs : KUR Hat-te

<ra-pa>-áš-⸢te⸣. Tadmor had reconstructed previously (1969 : 47, n. 12, 13) as hat-te GAL-te but later (1973 : 145)

as hat-te-⸢e⸣ (also RIMA 3). Tadmor, judging from the collation based on a photograph and a latex sqeeeze,

comments (1973) that the line ends with hat-te-⸢e⸣ with no further characters (Tadmor’s communication from J. D.

Hawkins).

8. For this ana, I follow Grayson who explains it as nota accusativi (RIMA 3, footnote). Unger (1916 : 14-15)

states that this is a meaningless vertical line. Cf. Donner 1970 : 52, n. 11. Schramm holds that it can be discarded

(1973 : 112). Unger did not transliterate it, nor did Tadmor (1973 : 145). On the use of ana as nota accusativi in

another inscription from Adad-nērārī III's reign, see Hasegawa in press.

9. Unger (1916 : 10) and Donner (1970 : 52) reconstruct [nakrūte (KÚR.MEŠ)], but Tadmor’s reconstruction

[KUR hat-te] seems more likely (1969 : 47, n. 13 ; 1973 : 145) ; Grayson follows him in RIMA 3. Schramm’s

reconstruction [šá KUR hat-te] (1973 : 112) is another possibility.

10. In an inscription from Šamšī-Adad V (823-11 BCE), father of Adad-nērārī III, a similar phraseology ina

tarṣi PN AD-ia appears (RIMA 3, A.0.103.1, ll. 39-40).

11 . This restoration is only tentative. Compare ummāni-šú DUGUD-tú ik-ṣur-ma in the Babylonian

Chronicle, (BM 21946, Obv. l. 21 : Wiseman 1956 : 70 ; Grayson 1975 : 100). Unger (1916 : 10) and Donner

(1970 : 52) reconstruct si-d[i

( ?)

-ir

( ?)

-t]a

( ?)

-šú

( ?)

-un, which is less probable. Tadmor (1973 : 145) reconstructs ⸢ik

?

-

lu

?

⸣ [ú IGI.DU₈]-šú-un “withheld their tribute”, which is followed by Grayson in RIMA 3. In Pazarcık Stela (Obv. ll.

7-10), Adad-nērārī III stated that the rebellious kings caused him and his mother to cross the Euphrates. This

reinforces the restoration of ll. 14-15 of the Saba’a Stela, in which Adad-nērārī considers an offensive action of his

enemies (“organised their [army]”) taken during his father’s reign as a casus belli, rather than only “withholding [of]

tribute.” See Hasegawa in press.

12. For the reconstruction of

d

⸢AMAR⸣.UTU, see Tadmor 1973 : 145, note for l. 16

sic !

.

13. Unger (1916 : 10) and Donner (1970 : 52) offer a reading iṣ-ba-tú biltu (GUN) ma-da-[tú lu

( ?)

ú-

kin

( ?)

]xx[...].

14. Following Tadmor’s reconstruction (1973 : 145). See also Sader 1987 : 238. Schramm (1973 : 112) offers

an alternative reconstruction : [ana tâmti rabīte alāka].

15. Unger (1916 : 10) and Donner (1970 : 52) reconstruct : [lu e-sir-šú ar-du-ti ēpuš

( ?)

].

16. Unger (1916 : 10) and Donner (1970 : 52) reconstruct : [ma-da-tú-šú am-hur].

Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - - - 109.243.68.227 - 30/05/2015 15h00. © Presses Universitaires de France

2008

ADAD-NĒRĀRĪ'S FIFTH YEAR IN THE SABA'A STELA

91

23. ⸢šaṭ

?

⸣-ri

md

IGI.DU-KAM LÚ.GAR.KUR URU né-med-

d

15 URU ap-ku ⸢URU ma⸣-re-e

24. KUR ra-ṣa-pi KUR qat-ni URU BÀD-duk-1.LIM URU kar-«a»-

m

AŠ PAB-⸢A URU sir⸣-qu

25. KUR la-qé-e KUR hi-in-da-nu URU an-at KUR su-hi URU aš+⸢šur⸣-DAB-bat

26. NUN-ú EGIR-ú šá ṣa-lam šu-a-tú ul-tú KI-šú i-⸢na⸣-šà-[ni-ni ana] ⸢KI⸣ [šá

?

]-ni-ma

20

27. ⸢man⸣-nu lu ina SAHAR.HA i-kát-ta-mu lu ina É á-⸢sak

( ?)

-ki

( ?)

⸣ u-še-ra-be

28. MU MAN EN-ia u MU šaṭ-ri i-pa-ši-ṭu-ma MU-šú i-šaṭ-ṭar aš+šur AD ⸢DINGIR.MEŠ⸣

29. li-ru-ur-šu-ma NUMUN-šú MU-šú ina KUR li-hal-li-qu

d

⸢AMAR⸣.UTU [...]

21

30. ⸢MAN⸣-su lis-kip ŠU.II-šú IGI.II

22

-šú ka-mu-su lim-nu-šú

d

UTU ⸢DI⸣.KUD ⸢AN u KI⸣

31. ⸢ik⸣-le-tú ina KUR-šú li-šab-ši-ma a-a i-ṭu-lu a-ha-⸢meš

d

IŠKUR⸣

32. gú-gul AN-e KI-⸢tim⸣ MU lis-su-uh GIM tib e-ri-bu-u ⸢lit⸣-bi-ma

33. li-šam-qit KUR-s[u]

Translation

1-5) [To] the god Adad, master of watering heaven and underworld, son of the god

Anu, splendid hero, [pe]rfect (one) whose strength is massive, first and foremost of the Igigi

gods, warrior of the Anunnaku gods, the one who is clad in awe-inspiring radiance, the one who

rides the great [stormes] (and) is clad in furious aura, the one who causes to fall the evil, the one

who bears a pure whip, the one who causes lightning to flash, the great lord, his lord :

6-11a) [Adad-nēr]ārī, great king, strong king, king of the world, king of Assyria,

unrivalled king, brilliant shepherd, exalted city-ruler, whose prayer (and) giving of food

offerings the great gods desired (and) they made his shepherdship as healing grass to the people

of [As]syria (and) widened his land ; son of Šamšī-Adad (V), strong king, [king of the world],

king of Assyria, son of Shalmaneser (III), ruler of all kings, the one who scatters the enemy

kings/lands.

11b-18a) In the fifth year <since> I sat on the throne in majesty, I mustered the land

(and) the troops of wide Assyria, and I verily commanded to march to the land of Hatti. I

crossed the Euphrates in its flood. The kings of extended [land of Hatti] who, in the time of

Šamšī-Adad, my father, became strong and organised their [army] — by the command of

Aššur, ⸢Marduk⸣, Adad, Ištar, the gods, my support, the fearsome radiance overwhelmed them

and they seized my foot. They brought tribute and t[ax] [...] (and) I received (it).

18b-20) I verily commanded [to march to the land of Damascus]. [I verily confined]

Mari’ in the city Damascus, [... he brought to me] 100 talents of gold, 1000 talents of silver. [I

received it and took it to Assyria].

21-22) At that time I had made the image of my lordship and the victory of my heroism

(and) the deeds of my hand. I erected it in Zabanni/Anzabanni.

17. The sign AN here is probably a scribal error for URU. See Tadmor, ibid. 145 ; Weippert 1992 : 44, n. 16 ;

RIMA 3 : 209, footnote.

18. Zabanni is identified with Tell Umm ‘Aqrubba (Kühne 1991). Cf. Shea 1978 : 106.

19. Weippert (1992 : 44, n. 16) reads : [e]p-šet qa-ti-ia AŠ(ina) qer-bi-šú al-ṭur AŠ(ina) URU Ha

!

-ban-ni ul-

[zis-s]u

!

.

20. This tentative reconstruction is based on the close phraseology in the inscription of Aššur-naṣirpal II

(A.0.101.38 ll. 40-43) : ... NA₄.NA.RÚ.A-ia šu-a-tú i-na-šú-ú ina áš-ri šá-ni-ma i-šá-ka-nu ina A.MEŠ ŠUB-ú ina

IZI i-qa-lu-ú ina SAHAR.MEŠ i-ka-ta-mu ina É ki-li ú-še-ra-bu-ši. “... who removes this stele of mine, puts it in

another place, throws (it) into water, burns it with fire, covers (it) with dirt, (or) takes it into a prison ...” Schramm

(1973 : 113) reconstructs : i-tú-ru ⸢ana⸣

( ?)

aš[ar(K[I)-šá]-ni-ma

( ?)

. Grayson (RIMA 3) reconstructs i-⸢ laq

( ?)

-qu

( ?)

⸣-

ni-ma.

21. After ⸢AMAR⸣.UTU, Schramm (1973 : 113) reconstructs [bēlūt]-s[u].

22. Tadmor’s transliteration is IGI.MEŠ (1973 : 145).

Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - - - 109.243.68.227 - 30/05/2015 15h00. © Presses Universitaires de France

92

SHUICHI HASEGAWA

[RA 102

9

2

23-25) The stone (which is) inscribed of Nergal-ēreš, provincial governor of the city

Nēmed-Ištar, the city Apku, the city Mari, the land Raṣappa, the land Qatnu, the city Dūr-

duklimmu, the city Kār-Aššurnaṣirpal, the city Sirqu, the land Laqê, the land Hindānu, the city

Anat, the land Suhi, the city Aššur-aṣbat.

26-33) A later prince who takes this image from its land to [somewhere] else, (and)

whoever either covers (it) with dust or brings (it) in a sanctum (or) erases the name of the king,

my lord and the inscribed name

23

and writes his (own) name : Aššur, the father of the gods,

may curse him, and destroy his seed (and) his name from the land. The god Marduk [...], may

overthrow his kingship and charge his hands and eyes in bondage. Šamaš, judge of heaven and

earth, may cause there to be darkness in his land so that they cannot see each other. Adad,

master of watering heaven and earth, may tear out (his) name (and) rise like an onslaught of

locusts (and) may strike hi[s] land.

In the light of other sources, the date of the inscription can be established. In l. 25 of the

Saba’a Stela, Hindānu is enumerated as one of the lands that belong to Nergal-ēreš.

24

According

to the Nineveh Stone Tablet (RIMA 3, A.0.104.9), Hindānu was added by royal decree to the

territory of Nergal-ēreš in 797 BCE. The text of the Saba’a Stela was thus written between 797

and 783 BCE, the year of Adad-nērārī III's death. Assuming that the submission of Mari’ to

Adad-nērārī took place in 796 BCE,

25

the text would have been written after 796 BCE and

before 783 BCE.

When, was the “fifth year” of Adad-nērārī III as recorded in l. 11 ? This question has

been a disputable subject for quite some time. To establish the chronology of Adad-nērārī III’s

reign, two sources must be consulted: the Eponym Canon and the Assyrian King List. The

Eponym Canon yearly enumerates the eponyms, including the kings’ names, and the Assyrian

King List records the length of each king’s reign. The chronology of the Assyrian kings in the

Neo-Assyrian Period, between Šamšī-Adad V and Tiglathpileser III, can be obtained by

comparing these two sources. Yet, it is difficult to establish the reign of Adad-nērārī III due to

the discrepancy in these two sources. There are two views as to the king's reign : 1) 809-782

BCE ; 2) 810-783 BCE. Based on the assumption that there is an error in the Assyrian King

List, E. Forrer (1915 : 15-16) and E. F. Weidner (1941-44 : 367) suggest the former view.

Weidner assumes that Adad-nērārī, unlike his predecessors, filled his eponym in his first regnal

year. The fourteen years ascribed to the reign of Šamšī-Adad V, father of Adad-nērārī III, must

accordingly be curtailed between one to thirteen years.

26

As a result of this “correction”, Adad-

nērārī III’s full regnal years began in 809 and ended in 782 BCE.

27

On the other hand, A. Poebel (1943 : 74-79) lays greater weight on the Assyrian King

List. Against Forrer and Weidner, Poebel suggests that it is unnecessary to assume the reign of

Šamšī-Adad V lasted fourteen years instead of the thirteen years recorded in the King List. He

23. Grayson (RIMA 3) translates MU šaṭri as “my name.”

24. The list of the sources, in which his name is mentioned, is found in Åkerman and Baker 2002 : 981a-

982a. His name is also rendered as “Pālil-ereš”. See Åkerman and Baker, 2002 : 981a ; Postgate 1970 : 33 ; Tadmor

1973 : 147, n. 32 ; Timm 1993 : 65, n. 29 with earlier literature.

25. Tadmor 1973 : 146-147 ; Millard and Tadmor 1973 : 62-64 ; Weippert 1992 : 53 ; Lemaire 1993 : 149,

153.

26. Weidner (1941-1944) also changes the ten years for Aššur-nērārī V's reign recorded in the King List to

eight years.

27. This view is followed by Schramm (1973 : 114-115) and Weippert (1992 : 49). Using the recent

modification in the date of the solar eclipse, which has been generally dated to 763 but is now corrected to 762, S.

Timm (1993 : 61, n. 11) has accordingly moved each of these dates later by one year ; so that, according to him,

Adad-nērārī III’s first regnal year falls in 808 BCE.

Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - - - 109.243.68.227 - 30/05/2015 15h00. © Presses Universitaires de France

2008

ADAD-NĒRĀRĪ'S FIFTH YEAR IN THE SABA'A STELA

93

assumes that from Adad-nērārī II (911-891 BCE) to Tiglathpileser III (745-727 BCE), the

eponym of each king falls in his second regnal year rather than the first.

This result emerges when calculating back from the accession year of Tiglathpileser III,

745 BCE, as recorded in K51, and using the length of reign of each king in the King List. The

reigns of the kings between Adad-nērārī III and Aššur-nērārī V should all be placed one year

earlier than in Forrer’s counting : Adad-nērārī III’s first regnal year should be in 810 with his

reign ending in 783 BCE. According to this calculation, it is unnecessary to shorten both Adad-

nērārī III’s and Aššur-nērārī V’s reigns as recorded in the Assyrian King List.

28

This

chronology has been widely accepted among scholars.

29

While Poebel’s chronology seems to settle the problem of the gap between the Eponym

Chronicles and the Assyrian King List, another chronological difficulty arises in l. 11 of the

Saba’a Stela. It indicates that the campaign against Hatti commenced “in the fifth year <since>

I sat on the throne in majesty” (ina MU 5.KÁM <šá> ina GIŠ.GU.ZA MAN-ti GAL-iš). The

fifth year of Adad-nērārī III is date to 806 BCE according to Poebel's chronology.

30

However,

the event entry of the Eponym Chronicles for the year 806 registers “to Mannea” (ana KUR

man-na-a-a), which is located in the far east, beyond the Zagros Mountain. On the other hand,

the entry for 805 BCE registers “to Arpad” (ana KUR ar-pad-da), which is placed in the land

of Hatti.

Poebel is aware of this problem and tries to solve it by explaining the campaign as

follows. The preparations for the campaign against Arpad in 805 BCE had already started a

year earlier, in 806 BCE, at the command of the Assyrian king. Yet, due to the brevity of the

Eponym Chronicles, the campaign was not recorded for 806 BCE (1943 : 84).

31

Similarly, H.

Tadmor (Millard and Tadmor 1973 : 62) suggests that the entries of the Eponym Chronicles

represent the locations of the king and his camp at the turn of the year when the report was sent

back to Assyria. If this hypothesis is correct, one may surmise that the Assyrian king and his

camp were in Mannea at the turn of the years 807-806 BCE, and that Adad-nērārī III launched a

campaign to Hatti in the middle of 806 BCE, while at the turn of the years 806-805 BCE, the

king and his camp were at Arpad. This hypothesis is highly conjectural because we do not even

know at what point in the year those entries were recorded.

By being aware that this hypothesis

is unfounded, Tadmor alternatively proposes returning to Forrer’s chronology, which dates

Adad-nērārī III’s fifth year to 805 BCE.

32

W. H. Shea (1978 : 105-106) proposes five possibilities for solving this problem : 1) the

fifth year of the Saba’a Stela refers to Adad-nērārī III’s personal reign after four years of co-

regency with his mother, Semiramis, i.e. 802 BCE ; 2) the military targets in the entries of the

Eponym Chronicles were reported from the field at the end of the campaign and were thus

recorded with the eponyms in the following years (Tadmor’s hypothesis) ; 3) Adad-nērārī III

conducted two different campaigns in 806 BCE, only one of which, i.e. Mannea, was recorded ;

28. A ten-year reign for Aššur-nērārī V was attested also in the SDAS King List. See Gelb 1954 : 223, col. iv,

l. 23.

29. Page 1968 : 147, n. 27 ; Cazelles 1969 : 108 ; Tadmor 1969 : 46, n. 3 ; Lipinski 1969 : 167, n. 37 ;

Donner 1970 : 56, n. 23 ; Cody 1970 : 328-329 ; Grayson 1976 : 140b, n. 48 ; Shea 1978 : 102-103 ; Millard 1994 :

13 ; Yamada 2003 : 75.

30. Poebel 1943 : 82, n. 299.

31. It should be noted that Poebel suggested this dating for Adad-nērārī III’s first campaign westwards in

opposition to the assumption, commonly held at that time, that ina GIŠ.GU.ZA MAN-ti GAL-iš in the Saba’a Stela l.

11 means the year when he ascended the throne after the four years of co-regency with Semiramis, his mother. This

assumption had been suggested by Unger (1916 : 19) and was followed by some scholars. Cf. Poebel, 1943 : 80-83.

32. Tadmor 1973 : 146. Oded (1972 : 25-26, n. 6) takes a similar attitude to this matter.

Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - - - 109.243.68.227 - 30/05/2015 15h00. © Presses Universitaires de France

94

SHUICHI HASEGAWA

[RA 102

9

4

4) the date of the Saba’a Stela is incorrect owing to a scribal error ;

33

5) the Eponym Chronicles

for this period are incorrect owing to a scribal error. Shea, in his conclusion, prefers the fifth

possibility because of some discrepancies between the two recensions of the Eponym

Chronicles.

34

In these solutions, either harmonising the data both in the Saba’a Stela and the

Eponym Chronicles (solutions 1-3), or, assuming errors in either of the two (solutions 4-5), the

possibility of the scribe’s manipulation of numbers was not considered. Recently, M. De

Odorico’s study on the use of numbers and quantifications in the Assyrian royal inscriptions

(1995) exemplifies that the Assyrian scribes, for propagandistic purposes, positively altered or

created numbers in the texts.

Tadmor (1958 : 30b-33a) demonstrates that the scribe’s manipulation of numbers could

have also occurred concerning the year counting in the Assyrian inscriptions. He enumerates

such examples of manipulating the year-count in Sargon II’s inscriptions. For example, Sargon

II, after he usurped the throne encountered internal conflicts in his accession year and his first

regnal year; then, he conducted a campaign in his second regnal year. This first campaign is

recorded in “Assur Charter” as campaign of “year two” to his second palû, while “Sargon’s

Prisms” and Fragment A. 16947 date the same event to his first palû. Tadmor suggests that, the

latter system was later employed to conceal the fact that Sargon did not conduct a campaign

during his first regnal year. In another inscription composed during the last years of Sargon,

even the campaign to Elam and Tu’munu was transferred from his second palû to his first palû.

Tadmor points out (1958 : 31b, n. 80) that the same tendency can also be observed in a

summary inscription from Khorsabad.

35

The image of a king fighting annually, like Sargon II, was also observed in other

Assyrian kings’ inscriptions. Analysing the stylistic changes in Shalmaneser III’s annalistic

inscriptions, S. Yamada (2003 : 73-79, 87-88, esp. 77-79; 2009 : xv-xviii) points out that the

palû annals were introduced in Shalmaneser III’s reign in order to display the king’s constant

military campaigning. By contrast, in the reign of Šamšī-Adad V, Shalmaneser III’s successor,

girru replaced palû, as the king could not conduct a campaign until his fifth regnal year. In the

reigns of Tiglathpileser III and Sargon II, both known for their military achievements, the palû

annals were indeed renewed.

36

Yamada's studies reveal some inconsistency in the stylistic

features of Assyrian annalistic inscriptions in the ninth and eighth centuries BCE, and shed light

also on the text of the Saba’a Stela.

Though Saba’a Stela is classified in the genre of summary inscription, its author

evidently attempts to relate the military achievement of Adad-nērārī III to a chronological fixed

point by using the expression “in the fifth year <since> I sat on the throne in majesty”. The

expression “in the X year” (ina MU X.KÁM), which originated in Babylonia, is foreign to the

Assyrian royal inscriptions.

37

The use of this Babylonian expression for the regnal year may

33. Recently Kuan (1995 : 98) adopted this assumption and suggested that the author of the Saba’a Stela

mistakenly wrote the sign for five, which is very similar to that of sign for six in cuneiform. See also Hughes 1990 :

196, n. 68.

34. Shea 1978 : 106, n. 26.

35. Weidner (1941-44 : 52-53) explained the difference between the palû-counting of the Annals of Sargon II

and that of the Prism-Inscription : the author of the latter counted the “Kriegsjahr” in which the king himself took

part, while the years that the king was ina māti or only his proxy led the campaign, were not counted. The problem of

dating the events in the beginning of Sargon II’s reign has recently been studied by Fuchs (1994 : 81ff).

36. Yamada 2003 : 84-85; 2009 : xxviii-xxix. See also Tadmor 1958 : 30-31.

37. This expression appears in Shalmaneser III’s inscription. A.0.102.1. 41) i-na MU 1.KÁM-ma šu-a-ti “in

that very year”. Cf. Yamada 2009 : xi, n. 9.

Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - - - 109.243.68.227 - 30/05/2015 15h00. © Presses Universitaires de France

2008

ADAD-NĒRĀRĪ'S FIFTH YEAR IN THE SABA'A STELA

95

also indicate a scribe’s attempt to conceal the inactivity of the king.

38

The entry of the Eponym

Chronicles for Adad-nērārī III’s first regnal year (810 BCE, following Poebel’s chronology)

indeed records “in the land” (i-na KUR), suggesting that the king did not campaign in that year.

Considering the manipulation of years in the Assyrian royal inscriptions for concealing the

king’s military inactivity, it would not be surprising if the scribe of this text counted the year

from the first military campaign in 809 BCE rather than from the first regnal year (810 BCE),

when the king did not campaign. For this purpose, the scribe employed the foreign Babylonian

expression ina MU X.KÁM. This means that there is no scribal error but a scribal

manipulation.

39

This hypothesis postulates the existence of an annalistic text of Adad-nērārī III,

in which his military campaign was yearly counted. The scribe of the Saba’a Stela possibly

used such an annalistic text as a source for his composition.

40

Another piece of evidence may support the hypothesis that the scribe used an annalistic

text, when composing the Saba’a Stela. The expression “<since> I sat on the throne in majesty”

(<šá> ina GIŠ.GU.ZA MAN-ti GAL-iš) in l. 11 has close parallels in other Assyrian royal

inscriptions. It is remarkable that almost all those parallels are accompanied with the phrases

“in my accession year” (ina šurrât šarrūtīya) and “after I nobly ascended the royal throne” (ina

mahrê palêya ša ina kussê šarrūte rabîš ūšibu). This refers to the beginning of the king’s reign

(particularly the first phrase [See Table 1]).

41

The use of the expression ina GIŠ.GU.ZA MAN-

ti GAL-iš alone in our text may indicate that the author of the Saba’a Stela shortened the

original annalistic text : he took the expression ina GIŠ.GU.ZA MAN-ti GAL-iš from the

description of Adad-nērārī III’s accession year ; and joined it with ina MU 5.KÁM from the

later part of the text ; but forgot to add ša between them.

42

The scribe’s propagandistic intention may be reflected also in the use of “in” (ina) in l.

11. Using the expression “in the fifth year” (ina MU 5.KÁM), the text dates Adad-nērārī III’s

campaign to “the land of Hatti” to his “fifth year.” It certainly creates an impression that the

subjugation of “the (entire) land of Hatti” was achieved only “in the fifth year” of Adad-nērārī.

On the other hand, the Eponym Chronicles record that the Assyrian army advanced to Arpad in

805 BCE, after which Assyria conducted four continuous campaigns to the west (805 to Arpad,

804 to Hazazu, 803 to Ba’li, 802 to the Mediterranean

43

) and another in 796 BCE (to

38. It also indicates the Babylonian influence in the Assyrian royal inscriptions at that time, as possibly

reflected also in the Nineveh Tablet. Cf. Tadmor 1958 : 30b, n. 74 for the Babylonian form of the year. Tadmor

(1958 : 31) assumed that the difference of the year-count between the sources resulted from the activity of two

different schools of scribes which differently counted years. Cf. Fuchs 1994 : 84, n. 4.

39. The scribe might have been Babylonian or of the Babylonian scribal tradition, as seen in the expression

ina MU 5.KÁM. Here the use of this expression is similar to that of palû in the Shalmaneser III and Sargon II’s

inscriptions. Cf. Tadmor 1958 : 29, n. 60 ; Yamada 2003 : 81-84.

40. Another possibility, though less likely, is that the author of the Saba’a Stela used Eponym Chronicles or

their prototype and erroneously calculated Adad-nērārī III’s reign from 809 BCE, the eponym year of Adad-nērārī

III. The line just above the line of year 809 BCE in the Eponym Chronicles had been considered as a dividing line

between Šamšī-Adad V’s reign and that of Adad-nērārī III. Poebel (1943 : 76-77), however, shows that the line

indicates the beginning or the end of an eponym period. Nevertheless, the scribe, who inscribed the text on the

Saba’a Stela, might have interpreted it, as scholars before Poebel did, as the beginning of Adad-nērārī III’s reign.

41. Poebel (1943 : 82, n. 297) illustrates two similar expressions from the Old Akkadian texts. The exception

is for example, Aššur-bēl-kala’s inscription (A.0.89.2, ‘Col. iii’ 22’) i-na 4-te ša-at-te ⸢ša i-na⸣ [kussê šarrūte ūšibu

...] “In the fourth year after [I ascended the royal throne]”. Although the sentence is fragmentary, the restoration fits

the context well. For the meaning of the expression šurrât šarrūtīya ina mahrê palêya, see Yamada 2000 : 12, n. 6 ;

Tadmor 1958 : 27-29.

42. This hypothetical annalistic text might have been compiled after Hindānu was added to the territory of

Nergal-ēreš in 797 BCE. Cf. Kuan 1995 : 97.

43. I identify tâmtim in the event entry for 802 BCE in the Eponym Chronicles as the Mediterranean.

Brinkman (1968 : 217, n. 1359), indicating that there is no example of eponyms referring to a body of water in the

Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - - - 109.243.68.227 - 30/05/2015 15h00. © Presses Universitaires de France

96

SHUICHI HASEGAWA

[RA 102

9

6

Manṣuate). Tadmor (1973 : 146), considering that the main historical subject of the Saba’a

Stela is Adad-nērārī III’s military achievements in these years, suggests that the scribe’s

intention in noting “in the fifth year” may have been to indicate that those events occurred after

the king’s fifth year. Even so, this theory does not explain why the scribe employed the term

“in” (ina) here. With due regard to the propagandistic character of Assyrian royal inscriptions,

it is likely that the scribe took this phrase from an annalistic text and intentionally left “in” (ina)

in this sentence, in order to give an impression, as if the conquest of “the (entire) land of Hatti”

had been achieved in a single year. This intention is obviously reflected in the phrase “In one

year I verily submitted the land Amurru (and) the land Hatti at my feet” in ll. 4-5 in the Tell al-

Rimāḥ Stela of Adad-nērārī III (RIMA 3, A.0.104.7), whose author is also Nerga l-ēreš.

To summarise, the historiographical analysis of the Saba’a Stela may reveal the

author’s manipulation in the text, in order to, on the one hand, conceal the king’s inactivity in

his first regnal year, and on the other hand, exaggerate the king’s conquest of the “land of Hatti”

in a single year. These two manipulations serve to present the image of the ideal Assyrian king

at that time, who unremittedly conducts military campaigns and subjugates the wide area in a

short period of time.

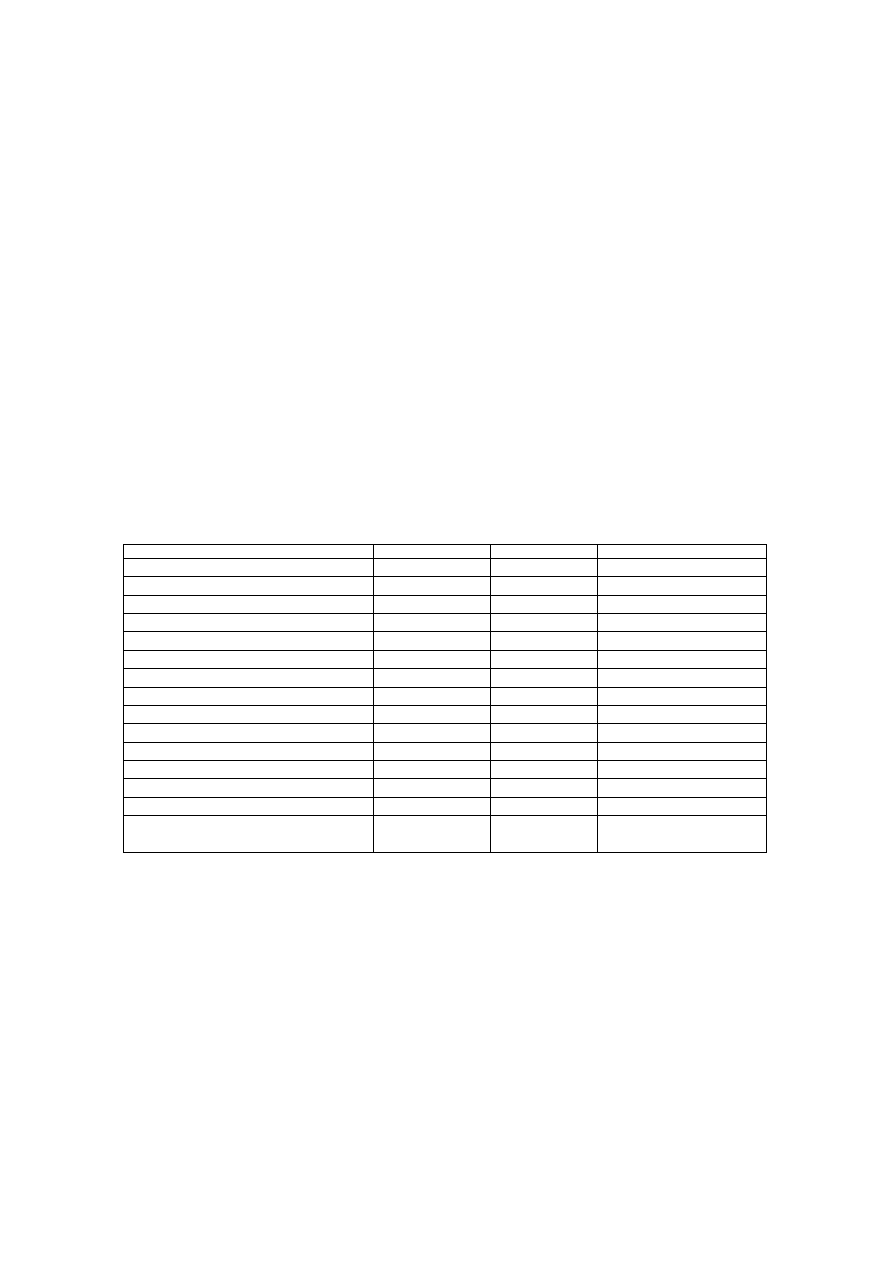

Table 1. Phraseology in the expression ina šurrât šarrūtīya ina mahrê palêya ša ina kussê šarrūte rabîš

ūšibu that appears in the Assyrian royal inscriptions

Kings and References in RIMA

ina šurrât šarrūtīya

ina mahrê palêya

ša ina kussê šarrūte rabîš ūšibu

Aššur-bēl-kala : A.0.89.2, ‘Col. i’ 8’

X

(X)

44

(X)

Aššur-dan II : A.0.98.1, 6-7

(X)

X

X

Adad-nērārī II : A.0.99.1, Obv. 8-9

X

X

X

Aššur-naṣirpal II : A.0.101.1, Col. i 43-44

X

X

X

Aššur-naṣirpal II : A.0.101.17, Col. i 61-63

X

X

X

45

Aššur-naṣirpal II : A.0.101.18, 2’

(X)

(X)

X

Shalmaneser III : A.0.102.1, 14

X

X

X

Shalmaneser III : A.0.102.2, 14-15

X

X

X

Shalmaneser III : A.0.102.6, 28

X

-

X

Shalmaneser III : A.0.102.10, 19-20

X

-

X

Shalmaneser III : A.0.102.11, Obv. 13’b-15’a

X

-

X

Shalmaneser III : A.0.102.14, 22-23

X

-

X

Shalmaneser III : A.0.102.16, 6

X

-

X

Shalmaneser III : A.0.102.1001, Obv. 3’-4’

X

X

X

Tiglathpileser III : the Stele from Iran,

Stela I/A, 36-37

X

X

X

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Åkerman, K. and Baker, H.D. 2002. Pālil-ēreš. In : Baker, H.D. (ed.) The Prosopography of the Neo-Assyrian

Empire. Volume 3/I P-Ṣ. Helsinki : 981a-982a.

Brinkman, J.A. 1968. A Political History of Post-Kassite Babylonia 1158-722 B.C. (Analecta Orientalia 43). Roma.

form ana + toponym, suggests identifying it as the “Sealand” of Southern Babylonia. The identification of the “Sea”

here with the Mediterranean might be corroborated by the Tell al-Rimāḥ Stela that mentions Adad-nērārī III's visit to

Arvad (Millard and Tadmor 1973 :59; Weippert 1992 : 50). The unpublished second fragment of the Šēḫ Ḥamad

Stela also mentions Adad-nērārī's visit to Arvad. I owe this information to Luis Siddal.

44. X denote that the phrase is completly/mostly preserved in the text, and (X) denotes that the phrase in the

text is almost broken and lost, and is thus based on the reconstruction.

45. Before the phrase, there is

d

šámaš DI.KUD UB.MEŠ AN.DÙL-šú DÙG.GA UGU-ia iškunu.

Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - - - 109.243.68.227 - 30/05/2015 15h00. © Presses Universitaires de France

2008

ADAD-NĒRĀRĪ'S FIFTH YEAR IN THE SABA'A STELA

97

De Odorico, M. 1995. The Use of Numbers and Quantifications in the Assyrian Royal Inscriptions. SAAS 3.

Helsinki.

Donner, H. 1970. Adadnērārī III. und die Vasallen des Westens. In : Kuschke, A. and Kutsch, E. (eds.) Archäologie

und altes Testament (Festschrift für Kurt Galling zum 8. Januar 1970). Tübingen : 49-59.

Forrer, E. 1915. Zur Chronologie der neuassyrischen Zeit. Mitteilungen der Vorderasiatischen Gesellschaft 20.

Jahrgang (Leipzig, 1916).

Fuchs, A. 1994. Die Inschriften Sargons II. aus Khorsabad. Göttingen.

Gelb, I. J. 1954. Two Assyrian King Lists. JNES 13 : 209-230.

Grayson, A.K. 1975. Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles. New York & Glückstadt (Reprinted in 2000. Winona

Lake).

Hasegawa, S. in press. Historical and Historiographical Notes on the Pazarcık Stela. Akkadica 131.

Hughes, J. 1990. Secret of the Times : Myth and History in Biblical Chronology (JSOTS 66). Sheffield.

Kuan, J.K. 1995. Neo-Assyrian Historical Inscriptions and Syria-Palestine. (Jian Dao Dissertation Series 1). Hong

Kong.

Kühne, H. Eds. 1991. Die rezente Umwelt von Tall Šēḫ Ḥamad und Daten zur Umweltrekonstruktion der assyrischen

Stadt Dūr-Katlimmu. (Berichte der Ausgrabung Tall Šēḫ Ḥamad/Dūr-Katlimmu, Bd., 1) Berlin.

Lemaire, A. 1993. Joas de Samarie, Barhadad de Damas, Zakkur de Hamat. La Syrie-Palestine vers 800 av. J.-C. EI

24 : 148*-157*.

Meissner, B. 1917. Referate : Eckhard Unger, Reliefstele Adadnirars III. aus Saba’a und Semiramis. (Publikationen

der Kaiserlich osmanischen Museen. II.) Edba, 1916. Deutsche Literaturzeitung 38 : 54a-55a.

Millard, A.R. and Tadmor H. 1973. Adad-nērārī III in Syria. Iraq 35 : 57-64.

Oded, B. 1972. The Campaigns of Adad-nērārī III into Syria and Palestine. Studies in the History of the Jewish

People and the Land of Israel 2 : 25-34 (Hebrew).

Page, S. 1969. Adad-nērārī III and Semiramis : the Stelae of Saba’a and Rimah. Orientalia 38 : 457-458.

Poebel, A. 1943. The Assyrian King List from Khorsabad — Concluded. JNES 2 : 56-85.

Postgate, J.N. 1970. A Neo-Assyrian Tablet from Tell al Rimah. Iraq 32 : 31-35, Pl. XI.

RIMA 3 = Grayson, A. K. 1996. Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC II (858-745 BC) (The Royal

Inscriptions of Mesopotamia : Assyrian Periods, vol. 3), Toronto.

Sader, H. 1987. Les états araméens de Syrie depuis leur fondation jusqu’à leur transformation en provinces

assyriennes. Beirut.

Schrader, E. 1872. Die Keilinschriften und das Alte Testament. Gießen.

Schramm, W. 1973. Einleitung in die Assyrischen Königsinschriften, zweiter Teil, 934-722 v. Chr. Leiden/Köln.

Shea, W.H. 1978. Adad-nērārī III and Jehoash of Israel. JCS 30 : 101-113.

Tadmor, H. 1958. The Campaigns of Sargon II of Assur : A Chronological-Historical Study. JCS 12 : 22-40, 77-100.

Tadmor, H. 1969. A Note on the Saba’a Stele of Adad-nērārī III. IEJ 19 : 46-48.

Tadmor, H. 1973. The Historical Inscriptions of Adad-nērārī III. Iraq 35 : 141-150.

Timm, S. 1993. König Hesion II. von Damasukus. WO 24 : 55-84.

Unger, E. 1916. Reliefstele Adadnērārīs III. aus Saba’a und Semiramis (Publicationen der Kaiserlich Osmanischen

Museen 2). Konstantinopel.

Weidner, E.F. 1930-31. Die Annalen des Königs Aššurbêlkala von Assyrien. AfO 6 : 76-94.

Weidner, E.F. 1941-44. Die Königsliste aus Chorsābād. AfO 24 : 363-369.

Weippert, M. 1992. Die Feldzüge Adadnararis III. nach Syrien Voraussetzungen, Verlauf, Folgen. ZDPV 108 : 42-

67.

Wiseman, D.J. 1956a. Chronicles of Chaldean Kings (626-556 B.C.) in the British Museum. London.

Yamada, S. 2000. The Construction of the Assyrian Empire — A Historical Study of the Inscriptions of Shalmaneser

III (859-824 B.C.) Relating to His Campaigns to the West (Culture and History of the Ancient

Near East, vol. 3), Leiden/Boston/Köln.

2003. Stylistic Changes in Assyrian Annals of the Ninth Century B.C. and Their Historical-Ideological

Background. Orient (Bulletin of the Society for the Near Eastern Studies in Japan) 46-2 : 71-91

(Japanese).

2009. History and Ideology in the Inscriptions of Shalmaneser III : An Analysis of Stylistic Changes in the

Assyrian Annals. In : Eph‘al, I. and Na'aman, N. (eds.) Royal Assyrian Inscriptions: History,

Historiography and Ideology – A Conference in Honour of Hayim Tadmor on the Occasion of

His Eightieth Birthday 20 November 2003. Jerusalem : vii-xxx.

Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - - - 109.243.68.227 - 30/05/2015 15h00. © Presses Universitaires de France

98

SHUICHI HASEGAWA

[RA 102

9

8

ABSTRACT

The present article discusses the “fifth year” of Adad-nērārī III’s reign as mentioned in the Saba’a Stela

from a historiographical point of view. The king’s “fifth year” has long been a matter of debate. Inconsistencies in

the chronological data provided by the Eponym Chronicles and the Assyrian King List have given rise to various

solutions. Poebel’s dating of the king’s reign, i.e., 810-783 BCE, makes Adad-nērārī’s “fifth year” 806 BCE, the year

of the campaign “to Mannea”, according to the Eponym Chronicles. Yet, Mannea beyond the Zagros Mountain lies

in the opposite direction to where the campaign was allegedly conducted by Adad-nērārī in his “fifth year”, namely,

to “the land of Hatti”. The proposed solutions, such as assuming a two-year campaign in 806-805 BCE, or assuming

an error either in the Saba’a Stela or in the Eponym Chronicles, fail to consider the possibility of numbers being

manipulated by the scribe. The employment of the Babylonian year count in the inscription, a count foreign to the

Assyrian royal inscriptions, may reveal the scribe’s intention to conceal the king’s inactivity of his first regnal year,

i.e., 810 BCE, the date of “in land” according to the Eponym Chronicles. The manipulation serves to present the

image of an ideal Assyrian king, which first emerged during Shalmaneser III’s reign.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article traite d'un point de vue historiographique de la « 5

e

année » du règne d'Adad-nērārī III, telle

qu'elle est mentionnée dans la stèle de Saba'a. Cette « 5

e

année » est depuis longtemps sujette à débat. Les

incohérences des données chronologiques fournies par les Chroniques Eponymales et la Liste Royale Assyrienne ont

donné lieu à plusieurs solutions. La datation du règne de ce souverain donnée par Poebel, c.-à-d., 810-783 av. J.-C.,

fait de la « 5

e

année » d'Adad-nērārī l'an 806 av. J.-C., l'année de la campagne « contre les Mannéens » selon les

Chroniques Eponymales. Néanmoins, le pays des Mannéens, situé au délà du Zagros, se trouve dans la direction

opposée à celle où la campagne aurait été conduite par Adad-nērārī dans sa « 5

e

année », à savoir, « le pays de

Hatti ». Les solutions proposées, telle que supposer une campagne de deux ans en 806-805 av. J.-C., ou une erreur

dans la stèle de Saba'a ou dans les Chroniques Eponymales, ne permettent pas de considérer la possibilité d'une

manipulation de nombres par le scribe. L'emploi d'un comput annuel à la babylonienne dans cette inscription,

comput étranger aux inscriptions royales assyriennes, peut révéler l'intention du scribe de dissimuler l'inactivité du

roi dans sa 1

ère

année de règne, c.-à-d. 810 av. J.-C., la date « dans le pays » selon les Chroniques éponymales. Cette

manipulation sert à présenter une image d'un roi assyrien idéal, qui a émergé pour la première fois durant le règne de

Salmanazar III.

Department of Christian Studies, College of Arts, Rikkyo University

Nishi-Ikebukuro 3-34-1, Toshima-ku, Tokyo 171-8501, Japan

Document téléchargé depuis www.cairn.info - - - 109.243.68.227 - 30/05/2015 15h00. © Presses Universitaires de France

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Żyto, Kamila Film in the Shadow of History Józef Lejtes and Polish School (2015)

Functional improvements desired by patients before and in the first year after total hip arthroplast

Dating Insider Seduction In The Year 2K

Functional improvements desired by patients before and in the first year after total hip arthroplast

Increased diversity of food in the first year of life may help protect against allergies (EUFIC)

Detection and Molecular Characterization of 9000 Year Old Mycobacterium tuberculosis from a Neolithi

Ideals and action in the reign of Otto III

The Faction Paradox Protocols 04 In the Year of the Cat

The Problem of Unity in the Polish Lithuanian State 1963 [Oswald P Backus III]

CRASHES AND CRISES IN THE FINANCIAL MARKETS, ekonomia III, stacjonarne

Equality In the Year 2000 Mack Reynolds

Gary B Nash The Forgotten Fifth, African Americans in the Age of Revolution (2006)

Glądalski, Michał Patterns of year to year variation in haemoglobin and glucose concentrations in t

Can you imagine what our lives will be like in the year 2050

or Calf Swelling in the 68 year old Wife of a Malpractice Attorney

Verne Jules In the Year 2889

Jules Verne In the Year 2889

Mettern S P Rome and the Enemy Imperial Strategy in the Principate

Early Variscan magmatism in the Western Carpathians

więcej podobnych podstron