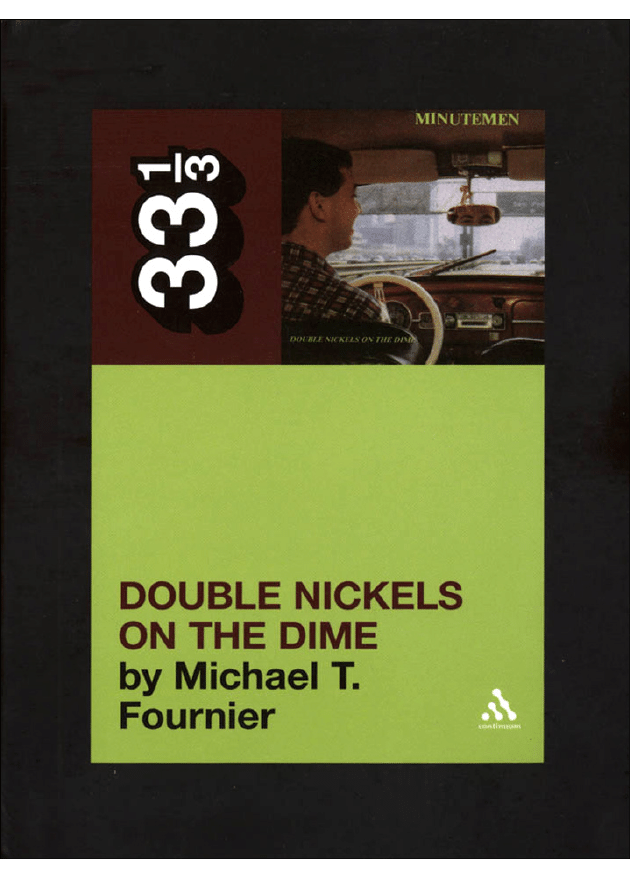

Double Nickels on the Dime

Praise for the series:

It was only a matter of time before a clever publisher realized

that there is an audience for whom Exile on Main Street or

Electric Ladyland are as significant and worthy of study as

The Catcher in the Rye or Middlemarch.... The series, which

now comprises 29 titles with more in the works, is

freewheeling and eclectic, ranging from minute rock-geek

analysis to idiosyncratic personal celebration—The New York

Times Book Review

Ideal for the rock geek who thinks liner notes just aren’t

enough—Rolling Stone

One

of

the

coolest

publishing

imprints

on

the

planet—Bookslut

These are for the insane collectors out there who appreciate

fantastic design, well-executed thinking, and things that make

your house look cool. Each volume in this series takes a

seminal album and breaks it down in startling minutiae. We

love these. We are huge nerds—Vice

A brilliant series...each one a work of real love—NME (UK)

Passionate, obsessive, and smart—Nylon

Religious tracts for the rock ’n’ roll faithful—Boldtype

2

[A] consistently excellent series—Uncut (UK)

We...aren’t naive enough to think that we’re your only source

for reading about music (but if we had our way...watch out).

For those of you who really like to know everything there is

to know about an album, you’d do well to check out

Continuum’s “33 1/3” series of books.—Pitchfork

For reviews of individual titles in the series, please visit

our

website

at

and

Also available in this series:

Dusty in Memphis by Warren Zanes

Forever Changes by Andrew Hultkrans

Harvest by Sam Inglis

The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society by

Andy Miller

Meat Is Murder by Joe Pernice

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn by John Cavanagh

Abba Gold by Elisabeth Vincentelli

Electric Ladyland by John Perry

Unknown Pleasures by Chris Ott

3

Sign ‘O’ the Times by Michaelangelo Matos

The Velvet Underground and Nico by Joe Harvard

Let It Be by Steve Matteo

Live at the Apollo by Douglas Wolk

Aqualung by Allan Moore

OK Computer by Dai Griffiths

Let It Be by Colin Meloy

Led Zeppelin IV by Erik Davis

Armed Forces by Franklin Bruno

Exile on Main Street by Bill Janovitz

Grace by Daphne Brooks

Murmur by J. Niimi

Pel Sounds by Jim Fusilli

Ramones by Nicholas Rombes

Endtroducing... by Eliot Wilder

Kick Out the Jams by Don McLeese

Low by Hugo Wilcken

4

In the Aeroplane Over the Sea by Kim Cooper

Music from Big Pink by John Niven

Paul’s Boutique by Dan LeRoy

Doolittle by Ben Sisario

There’s a Riot Goin’ On by Miles Marshall Lewis

Stone Roses by Alex Green

Bee Thousand by Marc Woodsworth

The Who Sell Out by John Dougan

Highway 61 Revisited by Mark Polizzotti

Loveless by Mike McGonigal

The Notorious Byrd Brothers by Ric Menck

Court and Spark by Sean Nelson

69 Love Songs by LD Beghtol

Songs in the Key of life by Zeth Lundy

Use Your Illusion I and II by Eric Weisbard

Daydream Nation by Matthew Steams

Trout Mask Replica by Kevin Courrier

5

People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm by

Shawn Taylor

Forthcoming in this series:

London Calling by David L. Ulin

Aja by Don Breithaupt

Rid of Me by Kate Schatz

and many more . . .

6

Double Nickels on the Dime

Michael T. Fournier

7

2009

The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc

80 Maiden Lane, New York, NY 10038

The Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd

The Tower Building, 11 York Road, London SE1 7NX

Copyright © 2007 by Michael T. Fournier

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by

any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording,

or otherwise, without the written permission of the publishers

or their agents.

Printed in Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fournier, Michael T., 1973-

Double nickels on the dime / by Michael T. Fournier.

p. cm. – (33 1/3)

eISBN-13: 978-1-4411-2216-2

1. Minutemen (Musical group) Double nickels on the dime. 2.

Punk rock

music—United States—History and criticism. I. Title.

ML421.M58F68 2007

782.42166092′2—dc22

8

2007004600

9

In memory of

D. Boon

1958-1985

Frank L. Fournier

1914–2006

Craig Ryder

1967–2005

10

Contents

Arena Rock Is the New Wave: Side D.

Punk Rock Is the New Nostalgia: Side Watt

Dance Rock Is the New Pasture: Side George

Chump Rock Is the New Cool: Side Chaff

11

History Lesson

The three members of the Minutemen—singer/guitarist

Dennes “D.” Boon, bassist Mike Watt, and drummer George

Hurley—spent their teen years in San Pedro, California, a

working class port suburb of Los Angeles. San Pedro was a

rough town, so Boon’s mom encouraged him and Watt to

play music. That way, she reasoned, they’d be doing

something productive and safe, away from the streets.

Boon was nominated guitarist. Before Watt got a proper bass,

he played the low strings on a guitar. D. and Mike mostly

taught themselves their instruments, trying to do covers of

“Smoke on the Water” and such. The famous anecdote about

their early years is that they didn’t realize that instruments

had to be tuned together. They thought that the looseness or

tightness

of

strings

was

a

matter

of

personal

preference—some guys liked to play tighter than others.

Their high school graduation came at roughly the same time

as the first wave of punk acts playing in Los Angeles.

Watt and Boon would drive up and see bands play the (in)

famous Masque club. If the weird dudes up on stage could

play in a band, the two friends reasoned, anyone could.

Including them.

Watt and Boon’s first punk band was called the Reactionaries.

(Their first group, which mostly played covers, was titled

Bright Orange Band. Watt had the band’s acronym painted on

the back of his jacket, causing everyone to mistakenly start

calling him Bob.) George Hurley, a former surfer who

12

switched to the drums after a near-death experience on the

waves, played the skins. Martin Tambourovich was the

singer.

After the Reactionaries disbanded in 1979, Boon and Watt

kept writing and playing songs. George Hurley joined a New

Wave band called Hey Taxi!, leaving the two friends

drummerless. Local welder Frank Tonche assumed the role.

The new three-piece was dubbed the Minutemen.

Tonche was none too enamored with the punk scene. He quit

the band quickly. Hurley was re-recruited when Hey Taxi!

broke up.

The Minutemen eschewed a traditional front man, feeling that

such a role was too “rock,” preferring instead to have a band

member (usually Boon, sometimes Watt) sing the quirky

lyrical bursts the band became known for.

The Minutemen played their first gig with Los Angeles’

Black Flag. After their set, Hag guitarist Greg Ginn, owner of

the SST record label, asked the trio if they wanted to put out a

record. The Minutemen guys couldn’t believe it. A record

after their first show!

The Paranoid Time EP, released in 1980, contained seven

short spurts of song that sounded wholly unique—jagged,

obtuse, and edgy. The records that followed—The Punch

Line, a fifteen-minute long LP released in 1981; What Makes

a Man Start Fires, their second long-player; the Joy and Bean

Spill EPs—documented the band defining and refining their

sound and aesthetic.

13

“It

was

such

odd,

prickly,

and,

at

first

pass,

un-listener-friendly music,” says Clint Conley, bassist for

Mission of Burma. “Furthermore, it seemed like rock in a

different language—like these savants had been airlifted in

from some distant continent. It shared almost none of the

syntax, surface, and convention of the ‘new’ music of the

time. No fat guitars, no power chords, no mouthfeel! These

short, strange eruptions had no specific reference to any spot

on the rock spectrum, really—Chuck Berry to Velvet

Underground. It was completely original and brave music.”

The Minutemen’s music sometimes takes the back burner

when the group is discussed simply because of the character

of both the band itself and the three men who played in it.

They were striking onstage: The ex-surfer drummer with the

squeeb ‘do playing faster than seemed humanly possible as

the flannel-clad ringer for Castro wrestled his bass and blew

locomotive steam from his cheeks. In the front, this huge guy

in bad shoes and cutoffs dwarfing his guitar, playing

dentist-drill blasts. They played songs about Latin America

and big thunder law, extended these metaphors you’d piece

together as you fell asleep weeks after hearing ‘em. They

portrayed the personal as political but were never preachy or

out of line, leading by example with a sense of humor, a huge

set of influences, and fierce determination to do it their way.

The Minutemen were a bunch of normal dudes with jobs and

worries who put things together

and made it happen. They were a band that used the

infrastructure and ethos of punk rock but were light years

away from the scene’s musical orthodoxy.

There is tragedy in the Minutemen’s story, as well. Singer/

guitarist D. Boon died in a van accident on December 22,

14

1985, just after the Minutemen’s 3 Way Tie (For Last) was

released. Watt swore off music until a young man from Ohio

named Ed Crawford showed up at his door. Shortly thereafter,

Crawford, along with Watt and George Hurley, started a new

band named flREHOSE.

This book is not about all that.

But it kinda is.

See, the music I love has always made me want to dig deep,

to figure out what the songs were about, and who/what

influenced them. Once I get those things, it’s easy to start

putting together an idea of what the players were thinking,

what they were shaped by, and how they funneled their

energies into something unheralded.

In the course of researching for this book, I have been lucky

enough to receive commentary and support from some of the

folks who were involved in making what I consider to be the

greatest record of all time. I’ve heard tons of stories and have

been presented with new ways to look at the album. A lot of

the anecdotes are pretty specific, super geeky—just the kind

of stuff, in other words, I would want to read about the album

if I wasn’t writing this book myself. I guess what I’m trying

to get at is this: I’m assuming that you, the reader, are way

into the band. Maybe not, though. Maybe Double Nickels is

one of those records that’s been sitting on your shelf for a

long time. Lord knows it’s more than a little intimidating. It’s

a long-ass album, daunting and seemingly impenetrable.

There’s a lot to absorb, which is why I’ve been going back to

it again and again for fifteen years. I still hear new stuff with

15

every spin, little nuances that had been missed in the

largeness of the opus.

So, it’s up to you how to read this. You can go straight

through and read about all of the songs, start to finish, or you

can flip around and find your favorites first. It’s cool.

16

History Lesson (Part II)

Work on the record that would eventually become Double

Nickels began in the summer and fall of 1983, following the

Minutemen’s European tour with label mates Black Flag.

In early 1983, the Minutemen were asked to contribute a song

to producer/ex-Blue Cheer keyboardist Ethan James’s Radio

Tokyo Tapes, named after the Venice, California, club where

he worked. Write a song, James told the band, and I’ll record

it for free. The Minutemen, of course, wrote really short

tunes,

so

they

mashed

three

songs

together—“Self-Referenced,” “Cut,” and “Dream Told By

Moto”—and recorded them all in one shot. (Those three

songs, along with five more recorded for a total of $50, would

later be released as the Buzz or Howl Under the Influence of

Heat EP.)

In the early eighties, it was difficult to find recording

engineers and producers who understood both the sonic and

aesthetic qualities of punk. Prior to the Radio Tokyo sessions,

the band had recorded solely with Spot, SST’s de facto house

producer. He always did a good job with the band, but, as

bassist Mike Watt said, “Ethan, although not knowing us

much, tapped right in. He’s a very open guy, not a lot of

prejudice.” The Minutemen were so impressed by the Radio

Tokyo sessions that they enlisted James to record their next

full-length.

The Minutemen recorded an album’s worth of material with

James in early 1983.

17

Then, in December, Hüsker Dü, a Minneapolis three-piece,

came through town, and posed an inadvertent challenge to the

band. Hüsker Dü—singer/drummer Grant Hart, singer/

guitarist Bob Mould, and bassist Greg Norton—were friends

with the Minutemen. Both acts were three-pieces, providing

musical camaraderie and kinship, and both bands, by that

time, were recording for SST Records. Hüsker Dü’s first

recording was released on the Minutemen’s New Alliance

imprint. “[SST] didn’t have the wherewithal to put out this

tape that (Hüsker ü) gave them called Land Speed Record and

we thought it was like methamphetamine Blue Oyster Cult,”

Watt says. “We really liked it, so we put it out. We put out

their first album.” (Hüsker Dü later returned the favor by

releasing the Minutemen’s Tour Spiel’EP on their Reflex

imprint.)

In the winter of 1983, Hüsker Dü made their way to

California. They were eager to get into the studio to record

their long batch of ambitious new songs, tided Zen Arcade,

with Spot.

Zen Arcade is a double-length concept album about a

runaway who experiences a life full of confusion and terror

outside of the familiar confines of home (before, of course, he

wakes up and finds that his trip was merely a dream). The

record contains tinges of psychedelia, quiet acoustics, and

Eastern meter, light years from the angry, buzzing thrash the

band was known for. It wasn’t all new and unconventional for

the band, though. Bits of, pop melody lie submerged under

Bob Mould’s trademark locust hum of guitar, with drums that

always felt a fraction of a second off anchoring howling

torrents of lament. Nothing like Zen Arcade had ever come

out of the punk scene before. The album (along with Double

18

Nickels, a little later) was, according to American Hardcore

author Steven Blush, “either the pinnacle or the downfall of

the pure hardcore scene.” After Hüsker Dü and the

Minutemen released their respective double albums, many

punk bands would begin to ignore the stylistic limitations of

the punk scene.

In the wake of Hüsker Dü’s magnum opus, the Minutemen

decided to rise to the inadvertent challenge presented by their

friends. Reknowned rock critic/former SST Records manager

Joe Carducci says, quite simply, “It just hadn’t occurred to the

Minutemen to do a double album.”

SST Records was willing and able to release the double

albums by both bands. “One thing that was really amazing

about SST records what that they did not censor their art in

any way,” says Steven Blush. “If a band came up and said

that they wanted to put out a triple album, they’d do it. If you

went to a major label with a relatively young band and said

that you wanted to do a double album or a triple album,

they’d laugh you out of the office.”

“[Hüsker Dü] had a whole concept with theirs,” says Mike

Watt. “[W]e already invented a batch of songs, recorded ‘em,

so we had to stretch and make a concept to put this [record]

together to be like them. It wasn’t really a competition, even.

When I wrote ‘Take That, Hüskers!’ in [the Double Nickels

liner

notes] it was acknowledging that they gave us the idea to

make a double album.”

It was back to James’s Radio Tokyo to record a second batch

of songs. It’s interesting to note that the songwriting

19

throughout Double Nickels is cohesive despite the time that

passed between the first and second recording sessions. The

players have no memory of which songs come from which

session—the work was simply done. (There are a few songs

that I was able to pin down as being products of either the

first or second session due to contextual clues. When such

hints come up, I’ve made notes in the entries for the tunes in

question.)

So, the challenge the Minutemen faced was to create a

concept from a seemingly disparate bunch of songs, recorded

months apart in two separate sessions.

They rose to the occasion and came up with interlocking

concepts. The first was a reaction to the popular music of the

time: a pre-Van Halen Sammy Hagar had scored a big pop hit

with “I Can’t Drive 55.” The Minutemen thought it would be

funny to comment on the nature of Hagar’s little ditty by

letting listeners know that driving fast wasn’t terribly defiant.

“So to wear red leather and say that you can’t drive 55 like

that’s the big rebellion thing ... to us, the big rebellion thing

was writing your own fuckin’ songs and trying to come up

with your own story, your own picture, your own book,

whatever. So he can’t drive 55, because that was the national

speed limit? Okay, well drive 55, but we’ll make crazy

music,” says Watt.

The cover of Double Nickels on the Dime spells it all out:

Watt driving his VW Beetle at exactly 55 miles per

hour—double nickels, in truckerspeak—on California’s

Interstate 10, affectionately known as the Dime. Minutemen

buddy/contributor

20

Dirk Vandenberg snapped photos from the backseat as Watt

piloted the Dub under a sign for San Pedro, the Minutemen’s

hometown. It took three circuits around Los Angeles to get

the photo right, but they got it.

“We had to drive all over Los Angeles and whenever we

found a San Pedro freeway sign we took a shot,” says

Vandenberg. “There were three elements that Mike wanted in

the photo: a natural kind of glint in his eyes reflected in the

rearview mirror, the speedometer pinned exactly on 55mph,

and, of course, the San Pedro sign guiding us home. There

were two separate days of shooting with me smashed up in

the backseat of his VW. I had to push myself back in the seat

as far as possible to get every element needed in the shot. We

finally got lucky and nailed it. The big story to me is how we

worked pretty hard to get it right and when the shot was

finally presented to SST someone botched the cropping for

the print and cut off the end of the word Pedro on the album

jacket.”

For their second concept, the Minutemen decided all three

dudes in their band would have a solo song on their album

sides. Their inspiration was Ummagumma, a double album

released by Pink Floyd in 1969. Ummagumma featured solo

performances by each band member. In keeping with the

automotive/driving 55 theme, each side of Double Nickels

would be announced by the particular band member’s car

starting (and, at the end of the record, the song “Three Car

Jam”—all three engines revving at once—would send things

off).

21

The good songs, Watt realized, should be at the beginning of

each side, and the ones that weren’t quite up to par should be

“hugging label,” on the inside of the record. The solution,

then, was to have a kind of fantasy draft, to draw straws and

let each member of the band pick songs in turn, and put the

leftovers, the “chaff,” on the final side of the album. That

way, says Watt, the songs that weren’t on the band’s top shelf

wouldn’t “glob up” and each member’s individuality would

show through all the more in the songs that they chose as their

favorites. “[Y]ou separate the wheat from the chaff,” Watt

explains, “’cuz that was the side that had the songs that

nobody picked.”

22

Arena Rock Is the New Wave: Side D.

Songs selected by D. Boon comprise the first side of Double

Nickels on the Dime.

I remember the day I first bought the record. It was sometime

in 1991, after finishing up my SATs at Concord High School

in New Hampshire. I was deep in the throes of skateboarding

at that point, spending hours a day skating in an upside-down

metal satellite dish (no kidding—hey, East Concord was

pretty rural!), watching videos of my favorite skaters—Mike

Vallely, Matt Hensley, Mike Frazier, Neil Blender—when I

finished. The old Santa Cruz skateboard films turned me on to

tons of great music on SST Records. I remember being

particularly impressed by this one song that played while

Jason Jessee skated a halfpipe. The song was called “Paranoid

Chant.” I tracked down a copy of the song on one of my

record-buying trips to Newbury Comics in Harvard Square.

This is all before the internet—I really had to dig to find

information about stuff back then. We all did. I went through

microfilm at the school library during free periods, looking

for catalogued articles about the Dead Kennedys, Clash, and

Sex Pistols. At one point, I found a clipping that talked about

what an amazing record Double Nickels was, and made a

mental note to buy it the first chance I got.

After I finished my SATs, I went down to Warren Street, first

to the comic shop, then to the record store directly across the

street. A cassette of Double Nickels was there in the small

23

import/punk section. I bought it and drove home listening to it

in my 1981 Volkswagen Rabbit pickup.

For the first few months that I owned Double Nickels, I’d start

at the beginning of side one and listen for awhile, mostly

when driving, then rewind back to “Anxious Mofo” and start

again. The thought of listening to the whole record from start

to finish every time was way too intimidating.

It makes sense, then, that I know the first batch of songs on

Double Nickels the best—I’ve listened to them the most.

Some of the record’s most silly, catchy, and intense songs are

on D.’s side. As I listened to the record more and more, I

came to appreciate the fact that the Minutemen had this goofy

sense of humor that set them apart from other bands. They

had their own style and weren’t afraid to be self-deprecating.

Take “#1 Hit Song,” for example. I was charmed by D. Boon

singing this seemingly by-rote ditty about love and tapering

off halfway through, going so far as to spell out the letters to

“et cetera.” If the Minutemen were going to sing a love song,

I quickly realized, they would never be so direct, so cloying.

Stopping halfway through made “#1 Hit Song” that much

funnier: “We know that you know we’re winking.”

Awesome!

I had listened to and enjoyed SST’s cassette reissues of the

first batch of Minutemen EPs and long players, but as

wonderful as some of that early stuff was/is, the songs tend to

blur together. Burst after burst after burst—it was hard to

catch up. There’s always talk of the Minutemen being

iconoclasts, writing these short, intense songs with an

unwavering ferocity and dedication to their craft. The talk, of

course, is all true. Thing is, though, that there were also all

24

these other bands who were writing really, really short songs

and playing them at blinding speeds. A lot of the hardcore

records I was listening to at the time, like the seminal This Is

Boston, Not L.A. compilation, featured ridiculously fast, angry

songs. I thought the Minutemen were good, but I wasn’t sold

on their greatness until I heard Double Nickels.

The onslaught of short, blazing songs the Minutemen were

known for was replaced by a greater sense of texture. Take

D.’s side, for example. After three songs, the shimmering,

gorgeous “Cohesion” gives a listener the space to breathe a

little bit. The complete change in musical gears that

“Cohesion” provides recontextualizes the beginning of the

album, making “Anxious Mofo,” “Theater Is the Life of

You,” and “Viet Nam” into a block of listening, a unit of

measurement. It was like the band was demarcating

easy-to-digest segments. Three songs, the pretty instrumental,

three more, the pretty song with the funny title, three more,

the weird one that mentioned the bass player by name, then

the car noise that signified the beginning of side two.

The sequencing was something of a happy accident—again,

the band had their own fantasy draft to determine the record’s

running order—but it all worked out for the best. The

segments on D’s side of the album, with their bursts

and pauses, pulled me in, allowed me to keep listening to this

monster of an album, left me excited to return and keep

learning more about both the band’s songs and the reasons

behind them. A goofy, varied introduction to their spiel, one

that proved to be warm and inviting enough to keep me

coming back.

25

“D. Boon had the most trebly guitar sound, totally scratchy

and everything,” says Mac McCaughan, owner of Merge

Records and singer/guitarist of Superchunk and Portastatic,

“but the songs are so catchy it was like they were ... making

this super catchy, memorable music. It’s totally in your face

in a lot of ways, and definitely lyrically, but at the same time

there was this pop side to it that was awesome. They

managed, in a forty-second song where thirty seconds of it

was scratchy guitar and crazy rhythms ... to have ten seconds

of it be this super catchy chorus.”

“Anxious Mofo” starts the album out (after, of course, the

sound of D. Boon starting his van). The Minutemen were

democratic in their songwriting. Someone would bring in a

riff, a bridge, some part of a song, and the rest of the band

would write around it. Drummer George Hurley wrote the

lyrics to “Mofo.” It’s a bold way to start an album, with the

lyric “Serious as a heart attack / makes you feel this way.”

The

listener

is

struck

with

a

gravity

that’s

nonspecific—you’re not sure exactly what he wrote the lyrics

about, but they impact you nonetheless. Hurley’s lyrics tend

to be dense to the point of being almost indecipherable, but,

somehow, they don’t lose any immediacy because the listener

can still find something in the words to latch on to.

At the time the album was being written, Hurley was

working early in the morning at a factory job, which informed

his songwriting. “[I]f you know the situation,” Watt says,

“you know the environment that bred it. The only time

[Hurley] ever explained a song to us was our first song that

was over two minutes. On What Makes a Man Start Fires, it

was called ‘The Anchor.’ He said, ‘This one’s about a

dream.’ Okay, but all the rest are about work. I know ‘cuz

26

that’s when he’s writing ‘em. But that’s when they’re really

loose, too, because you can’t concentrate on songwriting in

this big horizontal mill, running in needles for needle valves.

Can’t give too much—he’ll hurt himself! Minutemen, we’re

always servicing expression, not really trying to pay tribute to

a form, in a way. Not at all, because we didn’t really know

about songwriting. We’d never done it.”

The lyrics that follow the introductory salvo—“No device to

measure / no words to define / I mean, how can I express / let

alone possess?”—can apply to some unspecified instance in a

listener’s life. Or, if you’re feeling literal, it’s easy to picture

Hurley, bleary-eyed and sleepless from playing a show the

night before, reluctantly settling into a day of repetition. The

devices mentioned in the lyrics can be metaphorical or

actual—it could be George at the factory, or it could be the

recurring Minutemen theme of language coming into play, the

thought that there’s not a specific word to discuss the

situation at hand. (As the record progresses, multiple

instances of rumination on the topic of language will be

discussed.)

“Mofo” also features one of the sparsest guitar solos on the

record. D. Boon was an amazing guitarist, incorporating

elements of funk, jazz, and flamenco into his style, sometimes

using all three in the course of one song. At the end

of “Mofo,” he uses fewer notes than usual. Watt calls Boon’s

guitar playing on the song “econo,” one of the Minutemen’s

catchphrases (as discussed in the song “The Politics of Time,”

on Hurley’s side of the album). The notes that are played all

count. There’s no filler.

27

The words to “Theater Is the Life of You,” according to

Watt, are “just a spiel.” Watt found notes, ramblings written

on scraps of paper in D. Boon’s van, and brought them to

practice to be used as lyrics. Boon was “never embarrassed,

never ashamed or anything, never changed [the words],” says

Watt, because “he understood the thing with epiphanies.”

Boon and Watt had played together since they were boys,

and, as such, were keyed into each other’s styles and nuances.

A single listen was generally all it took for one dude to link

musically with the other. More of the practice time was spent

working Hurley’s drums into the mix, Watt says, because “we

didn’t want him to be just the backbeat shit. That’s the whole

idea of the band, not just economy in the material sense, but

makin’ it like conversation. Making this an interesting

conversation. We’re going to have Georgie in here, man.

We’re going to make space for him, he’s going to come in

here and speak, spell his name with his fuckin’ fills, so that

would take a little of the time. That wasn’t really that

traditional, but luckily, Georgie didn’t have reverence for

what was tradition.”

Musically, “Theater” is dense. There are many instances on

the album where members of the band will advance or retreat

their playing to allow for the other instruments to come to the

top of the mix. On “Theater,” though, everything collides a

bit, doesn’t have room to breathe, like the

part of the conversation where everyone talks at the same

time. Hurley’s drumming, heavy on crash cymbals,

occasionally overpowers D. Boon’s treble-heavy guitar work.

The listener gets a nice dichotomy right at the beginning of

the record: the intense focus of “Anxious Mofo,” with its

democratic arrangement, versus the focused intensity of

28

“Theater Is the Life of You,” with all three dudes howlin’ at

the same time.

The three Minutemen were inspired by different things at

different times, which is reflected by the variation in both

their music and lyrics. Boon’s words in “Theater,” much like

Hurley’s on “Anxious Mofo,” aren’t sweeping; they rely

instead on impressions of a specific moment, without context

provided, to form a narrative flow. The moment that Boon

was writing about has been lost to history, but the lyrics are

universal enough to be easily applied to some instance in the

listener’s life. Elsewhere on the album, like on “Corona,”

Watt’s homage to spending Fourth of July on a Mexican

beach, the lyrics are more anecdotal.

“Viet Nam” is a song that shows the influence of the Pop

Group, a band that, along with Wire and Creedence

Clearwater Revival, was a huge influence on the Minutemen.

The Pop Group’s music integrated elements of funk, reggae,

and jazz into a post-punk framework. When the Minutemen

started playing, punk rock was still loose, undefined, and

relatively free of stylistic codes and taboos. It was the

influence of the Pop Group, says Watt, that helped bring

home the point that the Minutemen could mix their copious

influences however they saw fit. The members of the Pop

Group were all fiercely well read, erudite, and full of ideas on

literature,

politics, and seemingly everything else. The Minutemen were

the same way—always reading, always trying to learn more

about the world. “We can put anything with anything!” says

Watt. “Anything goes! Take pictures, don’t take pictures,

gigs, flyers, all these things! All up to us! World of

possibilities!”

29

The Pop Group has a song called “Blind Faith” that

influenced the structure of “Viet Nam.” Watt describes “Blind

Faith” as “kinda disco.” Prior to starting research for this

book, I had never listened to the Pop Group, so I tracked

down some of their albums. The Pop Group’s sonic influence

is easily audible in the Minutemen’s recordings—trebly

guitar, off-kilter rhythms, bubbling bass.

“Viet Nam” is funny, at least initally. The song’s first lyrics

are “Let’s say I’ve got a number / that number’s fifty

thousand / that’s ten percent / of five hundred thousand / oh,

here we are / in French Indochina.” To a contemporary

listener, the words sound like a bunch of non sequitors strung

together to fit the meter, a trick used to best effect by

Pavement in the early 90s. I was doing a lot of my initial

listening to the record while I was driving, and, as such,

didn’t pay a whole lot of attention to the names of the songs.

So, for me, “Viet Nam” was “the 50,000 song,” “#1 Hit

Song” was “the E-T-C song,” stuff like that.

I did eventually get around to looking at the track listing on

my cassette tape’s cover. Once I did, “Viet Nam” was put into

context, and didn’t seem as funny any more: 58,148

Americans killed, and an estimated 500,000 North

Vietnamese dead. The reason for all of the atrocities is

outlined in the last lyric: “not one domino shall fall,” a

reference to the American anti-Communism campaign that

was used,

to similar results, during the Korean War in the 50s. (The

Minutemen often sang about the effects of American foreign

policy—elsewhere on Double Nickels the theme is revisited

on both “West Germany” and “Untitled Song for Latin

America.”)

30

The lyrical gravity of “Viet Nam” is put into relief by the

musical form the band chose. The main guitar riff sounds

kinda silly, not unlike a scale as it slides up and down the

guitar’s neck—the kind of stuff that you try to play the first

day you figure out the shape of a barre chord. Watt’s bass

punctuates, adding ringing twangs to silences like he’s trying

to get a word in edgewise, and Hurley’s drums are

unrelenting. The song’s this all-out assault, poppy and busy,

and it’s about American foreign policy. It’s like, who the hell

are these guys?

That was the thing—the Minutemen’s juxtapositions added

import because they were so jarringly original, following the

Pop Group’s stylistic lead of mixing improbable genres,

taking it to the next level. Again, the Minutemen’s

unorthodox habit of putting anything with anything recurs

throughout the record, one of many underlying themes of

Double Nickels.

The first instance of the band’s recurring Ummagumma-

themed instrumentals is “Cohesion.” As Watt and Boon were

growing up, they were both influenced by a San Pedro

musician named Roy Mendez-Lopez. He was an “incredible

virtuoso” on the guitar, says Watt, with a Coltrane-esque

practice regimen, spanning an incredible number of hours a

day. Mendez-Lopez lived in his car—“talk about econo,” says

Watt—built his own guitars, learned Vivaldi pieces, and

played intricate flamenco songs. He was an inspiration to

Watt and Boon, encouraging them both to play along with

their favorite records, then put their own personal spins on the

material after they had it wired. Mendez-Lopez often played a

flamenco classic called “La Linda,” a song later appropriated

31

by the Doors in their song “Spirit Caravan.” “La Linda” was

also an inspiration for “Cohesion.”

The Minutemen thought that the record’s themes would be

readily apparent to listeners—the respective record sides

named after band members, the obvious 55 miles per hour

imagery, the Floyd-esque solo songs. “No one got it. No one!

Zero! Stuff that was so obvious. [W]e were in our own world

so much. . . . How could you see that, not being us?” says

Watt.

The references that might have been obvious to the band, who

grew up in the “thermos bottle” of San Pedro, were often lost

on the punk rock public, whose knowledge of music and

history was generally far more limited in scope. Initially,

punk rock was a reaction against the status quo, and part of

that reaction was carving out a new path and forgetting the

past. “There wasn’t hardly anyone doing it” in San Pedro,

says Watt, but the scene in Los Angeles was only a short

drive away. The relative isolation of playing their blue-collar

port hometown ensured that their style, though influenced by

others, would remain their own thing. They were always

happy to map out the geneaology of their own group via the

bands and people that influenced them (and did so at the end

of Side Watt, on “History Lesson, Part II.” Skip ahead, if you

like).

When the Minutemen first got into punk rock, things were

wide open, undefined—part of the reason why they

liked the new thing so much. As time passed, a sort of

musical and stylistic orthodoxy came about, due in part to the

emergence of hardcore as the next extension of punk.

Suddenly, this umbrella, under which all of the weirdos

32

gathered and did their thing, disappeared, and a strict code of

rules took its place. Coloring inside a set of lines took the

place of creativity.

“Part of the problem with hardcore,” says Steven Blush,

author of American Hardcore, “is that it kinda wanted you to

stay the same. And as you grow, you expand and you

experiment, and hardcore stood in opposition to their

experimenting.”

Students in my History of Punk Rock class at Tufts

University were very fond of the Minutemen’s music. The

band’s ability to take risks and to draw influence from many

different styles and genres went over very well with them.

The scene police, I’m sure, would frown, and heavily, on a

flamenco instrumental being included on a so-called punk

album, but the Minutemen’s insistence on not giving a shit

and playing what they wanted to play was universally well

received by a bunch of kids who had little prior exposure to

the band. “Punk wasn’t a style of music,” says Watt, “it was a

state of mind, and the style of music was up to each band

doing it.”

“It’s Expected I’m Gone” starts with a slow drumbeat (for

the Minutemen, anyway), no bass or guitar. Over the years,

the song has been a popular one for other musicians to

sample/cover: Jawbox, Sublime, and, most recently Bonnie

“Prince” Billy with Tortoise have all tried it.

The song’s relative slowness was the Minutemen’s

attempt to change their dynamic. Playing a bunch of songs of

the same speed and length wouldn’t make for a good show,

they realized, so the tempo was slowed to a more relaxed pace

33

to try and replicate the way thoughts occur. “[W]e changed

gears a lot because that’s how it seems the mind would work,

from there to there to there to mere,” Watt says.

After Hurley’s drums start things off, Watt’s bass line and

Boon’s guitar weave around each other through the song’s

verses. I’m inclined to say that it’s the bass line that provides

the lead part of the song, but both sets of strings wind up

balancing out pretty well—there’re bursts of treble from

Boon, with Watt adding coughs of bass as the waves of guitar

subside.

Structurally, the guitar solo doesn’t have a lot to do with the

rest of the song. What had been a very calculated,

thick-sounding number suddenly veers off course and

becomes the platform for one of Boon’s prototypical

blues-tinged solos, with Watt punctuating, this time using a

jazz framework for his bass playing. The two parts, guitar and

bass, don’t sound like they should fit together, but somehow

they do—the Minutemen, once again, trying to replicate how

the mind works. Then it’s suddenly back to the beginning, a

repeat of Hurley’s drum intro, then the verse.

The lyrics to “It’s Expected I’m Gone” are very

self-referential, an instance of impressionistic thoughts that

refer back to a specific moment in time. The lyric “I don’t

want to hurt / see, my position was here / I mean, as it was, I

was” could be talking about anything, really. It’s up to the

listener to try and find a situation in his or her life to apply the

words to.

The last lyrics of the song, “No hope / See, that’s what

34

gives me guts / big fucking shit / right now, man,” were

written specifically because Watt thought it would be funny

for D. Boon to shout “big fucking shit” onstage. Seriously. D.

Boon was picked on a lot as a kid because of his size, and

developed both character and self-confidence as a result.

When he strapped his guitar on, he was determined to play

without any inhibition. “He would get so into it, man, I just

wanted him to say that, just the feeling—no meaning or sense

of the word,” Watt says. “I never really told him that until

later.”

On a record as long as Double Nickels, there are going to be

peaks and valleys, ebbs and flows. On each of the album’s

four sides, there are lulls in the action before the intensity

begins anew. Sometimes songs contain many different,

disparate parts. “#1 Hit Song” is an example.

The tune starts off with something resembling a tide—the

band builds to what seems to be a crescendo, retreats, builds

back to almost the same point, stops. As the intro notes fade

away, the main riff of the song kicks in: this very

rock-sounding guitar lead. From there, Hurley’s drums propel

the song along at an even, radio-sounding pace, far less

frantic than his usual fare. D. Boon sings Hurley’s lyrics, in

what Watt describes as a “caricature of being smooth”: “On

the back of a winged horse / through the sky, pearly gray /

love is leaflike / you and me, baby.” The listener is set up for

the punch line, the final lyrics: “twinkle, twinkle / blah blah

blah / E / T / C.” The last bit, the et cetera, acts as a sort of

surrender, like “all right, we tried to play it straight. We’re not

buying it, and we know you aren’t, either. We hope you

enjoyed our little experiment—now we’re going to go back to

doing what we do.” What D. Boon does, of course, is kick

35

into a typically blazing guitar solo, one of the few overdubs

on the album. “D. Boon only used an effect on records. He

would overdub with his green Tube Screamer, 909. Worth a

lot of money now, econo shit [then],” says Watt. “He used

this hollow body Gibson ES 120 that had to have the cord

soldered right into it. He used that to overdub leads. Never

played it live, hardly.”

It’s interesting to note that after Double Nickels was released,

the band decided to release a follow-up album that utilized

more traditional song structures and lyrics, kinda similar to

“#1 Hit Song.” It was a bit of a goof—“we made fun of

ourselves really heavy,” says Watt—but it was an attempt to

see what could happen if the band played music that was

geared toward a wider audience. The follow-up, titled

Project: Mersh, contains songs that eschew the Minutemen’s

formula (or what passes for one), taking on the more familiar

trappings of rock music: verse-chorus-verse song structure,

songs between two and a half and four minutes in length,

fadeouts. Mersh still sounds good after all this time—the

horns!—but it’s not a record I pull out all that often. When all

was said and done, it sold half as many as Double Nickels did.

Minutemen songs sometimes had a certain musical gravity to

them, a weight, but not because of the use of power chords.

D. Boon’s guitar playing seldom relied on standard chugga

chugga punk riffage. “His chords were thirds, or ninths,

thirteenths,” says Watt. On “Two Beads at the End,”

though, Boon uses standard punk chord shapes, making the

song sound more like a “pop norm” than usual. Of course, the

Minutemen’s idea of a pop norm was often

pretty far from pop, as is the case here. The standard chord

shapes are only used for the half of the song that features

36

lyrics. There’s the song’s introduction, a reprise, and then an

extended, repeated outro which takes up the other half.

David Rees, the artist responsible for the comic strip Get Your

War On, is a huge fan of “Two Beads at the End.” “It’s . . .

funky and rhythmic without sounding like ‘funk music,’

which I don’t really like,” he says. “It’s just bad-ass and

original. It’s physical, in a way, because Boon is obviously in

total control of his instrument. The world I always think of for

that lick is ‘jabbing.’ Like it’s jabbing at the other

instruments. The quick slide down the neck . . . sounds so

casual, with so much panache—I love it! Then, a few beats

later, the song opens up and the verse begins. ‘Two Beads at

the End’ is an original, sophisticated song.”

Hurley wrote the lyrics for “Two Beads.” As per usual, when

Boon and Watt asked what the song was about, Hurley said

he couldn’t remember. “Georgie said a lot of times he’d write

[lyrics] and then right away forget what they were about. So

[we] never had any inkling to that one. [T]he songs would

sometimes be little babies, little creatures of their own. It

came from us, but now it’s gone. [‘Two Beads’] was like that.

He never told us about . . . ‘feel like a poker in someone’s

fireplace,’” Watt says. Despite the obtuse nature of the lyrics,

though, Boon was able to sing them with conviction. There’s

an urgency to Boon’s delivery that makes a listener identify

with what’s being said, even if the lyrics are indecipherable.

“Do You Want New Wave or Do You Want the Truth?” is

one of the angriest songs on the record. It’s also one of

the prettiest. Upon initial listen, the song seems gentle. The

first few lyrics—“a word war / could set off the keg / ‘my

words are war!’ / should a word have two meanings?”—feel

37

innocent, but the first cuss—“what the fuck for? / should

words serve the truth?” ends the verse. Something is going on

here.

“New Wave” was written as a pause, a breath. Watt thought

of Minutemen albums as “big landscapes,” and intended

“New Wave” to be a valley, despite the quiet rage that seethes

throughout it. Boon plays his guitar quietly, Watt chips in

with drone, and Hurley contributes guitar, as well as drums

that recall the stand-up style of Maureen Tucker of the Velvet

Underground.

Artist Raymond Pettibon turned the band on to the language

and semiotic theories of Ludwig Wittgenstein and Umberto

Eco, which the Minutemen referenced in the song. The song’s

lyrics deal with the duplicity of words—wondering if there

are still sensations that have not been strictly defined by

language, and reflecting on anger in the ways that words can

be twisted around to be used as weapons. Ruminations about

language are another recurring theme on the record—on the

first song, “Anxious Mofo,” the question “how can I express,

much less possess?” is posed, and later on, in “The World

According to Nouns,” the theme is revisited once again.

As “New Wave” winds down, the multiple narrators state

their opposing views: “I stand for language / I speak for truth

/ I shout for history.” The very last line—“I am a cesspool /

for all the shit / to run down in”—finds the multiple narrators

united as they swap lyrics. It’s a shocking end, alarmingly

immediate, as the song itself glides in for an easy

landing. Finishing on such a lyrically jarring note provides a

good counterpoint to the shimmering beauty of the rest of the

song.

38

How does the genre of New Wave tie into the notion of

language, semiotics? Through record sales and marketing.

The first batch of CBGB’s and London bands didn’t sell as

well as the record companies had hoped—they were a little

too edgy and inaccessible. In an effort to try and boost sales,

bands that weren’t altogether mainstream in approach were

marketed as “New Wave.” When we remember New Wave

now, twenty years later, the tendency is to think about

synth-based stuff, the kind of songs that are played at retro

80s nights at dingy scenester bars. At the time, though,

anything that was remotely left of center was being marketed

as New Wave to try and capture the attention of the

record-buying public—throwing a bunch of shit at the wall to

see what would stick. As the music was codified, it became

easier for bands to tailor their sound and image to the trends,

which resulted in a more homogenous sound. Happens every

couple of years—disco, grunge, swing, shoegaze, et cetera.

The music that was the inadvertent spawn of punk rock left

the Minutemen wondering what had happened, how words

had been twisted to betray.

“Don’t Look Now” is the only song on Double Nickels on

the Dime that wasn’t recorded at Radio Tokyo. At the

suggestion of former SST co-owner/rock critic Joe Carducci,

the Minutemen used a cassette tape of the song, a Creedence

Clearwater Revival cover, that was recorded at a live show at

Hollywood’s Club Lingerie. “They had [‘Don’t Look Now’]

recorded [in a studio],” says Carducci, “but I liked my version

with the first bunch of casual knucklehead fans talking over

the band and that lyric. So I explained what it added to the

song to Mike and he said, ‘Yeah, switch the versions,’

without even hearing it. The Minutemen were always brave

like that.”

39

Sonically, the song sounds pretty good, especially considering

that it was recorded live to cassette. The band is a little

distant, like they’re playing at the end of a long hallway, and

there are musical intricacies—fills, licks—that are lost in the

tape’s muddiness. Carducci’s point wasn’t really about the

band’s performance, but what was going on in the audience

while the song was being played.

The Minutemen were big fans of CCR for several reasons:

their politics, their music, the everyman approach they took to

playing (Watt’s well-documented love of wearing flannel is a

direct result of seeing John Fogerty decked out in checks on

Creedence’s artwork). In the case of “Don’t Look Now,” the

emphasis is on politics. Who’s going to take care of all the

things that are usually taken for granted—food, shelter,

clothing? Not the band, D. Boon intones from the stage, and

not the audience, either—they’re not even paying attention.

They’re busy talking.

Singing, Watt says, is one thing, but actually doing is another,

something that CCR’s singer/songwriter John Fogerty had to

deal with in the sixties, a decade rife with slogans and

patriotism. “[Fogerty]’s like, who’s going to grow the food,

who’s going to do this or that, you know? You talk the

fuckin’ talk, but what’s real?” By using Carducci’s tape, the

onus is thrown direcdy on the listener. It’s not the people

gossiping at the show who are going to take any sort of

responsibility. Is it you, the listener? Are you even paying

attention? “All the stuff you take for granted,” says Watt.

The theme of responsibility recurs on the third side of the

album, on the song “Themselves,” which is a much less

rhetorical, more hands-on take on the same issues. The

40

Minutemen’s working-class background is as much of an

influence on their songwriting as any of the groups they

cite—time and again on Double Nickels (and in the rest of

their catalogue), lyrics are drawn from the band members’

experience and perspective. “We didn’t make enough to live

on [playing music] even living econo,” says Watt, “so we’re

always working the whole time. So we never had lack of stuff

to write about.”

“Shit from an Old Notebook” is a song Watt built around

some writing Boon had done. “To keep me from getting in the

ruts, I’d ask those guys to give me words,” Watt says. “So

that was actually an old notepad. Not even haiku, just

thinking out loud, not rhyming or anything.”

“Notebook” is the last song Watt played with a pick (though

he sometimes uses one now, after an extended layoff). On the

early records, the Minutemen’s breakneck tempos rendered

Watt’s bass playing down to something resembling rhythm

guitar—he played lots of chords. As the band began to

diversify a little, adding more space and time to their songs,

Watt’s bass lines began to breathe more. (Plus, Watt got a

Fender Telecaster bass, which he wanted to play with his

fingers.)

I went back and listened to “Shit from an Old Notebook”

more critically after Watt told me that the song was his last

use of a pick. With that nugget of info in mind, I could hear

how his bass sounded restrained and less funky

than on some of the album’s other songs. But maybe, I

thought, I was a victim of suggestion, filling in gaps that

weren’t really there. I don’t play bass, after all—don’t play

anything; I just listen. Ryan Gear, who runs the Watt/

41

Minutemen/flREHOSE mailing list, plays bass, so I asked his

opinion on the matter.

“[I]t does sound a bit flatter than some songs written later not

played with a pick,” Gear said. “It’s still one of my favorite

Minutemen songs, more for the lyrics mainly. Instead of

Watt’s bass lines anchoring the song (pardon the pun), I get

the aural feeling that’s led along by Georgie’s drumming and

D.’s voice. . . . Also, in regards to playing, I could never

really play bass that well with a pick, mainly because I never

learned with a pick, and didn’t even try playing with a pick

until after I’d been playing for five years or so. So whenever I

play/try to play with a pick, my playing feels more forced and

robotlike and I don’t really have the feel like I can flow

through notes than when I just play with my fingers. That’s

another impression I was just getting from ‘Shit from. . .’

from hearing it again now.”

The song itself is a screed against advertising. “Psychological

methods to sell,” sings D. Boon, “should be destroyed.” The

lyrics are rattled off in a rapid-fire staccato of fury, syllables

crammed up against each other. The thought of promoting the

art in question, whether it’s writing, painting or music, gets

more thought and effort than the art itself—things get too

commercial (or, in the Minutemen’s slang, mersh) and the

focus gets lost. “Notebook” is a cautionary tale, a reminder

that the business aspect of art shouldn’t get in the way of its

creation. The last lyrics of the song—“Morals, ideas,

awareness, progress / let yourself be

heard!”—provide a counterpoint for D. Boon’s guitar solo,

which runs for the second half of the song’s ninety-six

seconds. Not only is Boon doing what he was just singing

about, letting himself be heard, but he’s letting the product (in

42

this case, the song) sell itself, through its passion and its

nonreliance on traditional structure. A fifty-second guitar solo

to finish the tune off is a giant middle finger to the suits the

band is singing about/against—fuck advertising indeed.

The Minutemen wrote a lot of material. (Maybe you’ve

noticed.) They were afraid of falling into ruts, writing songs

that were similar in style, like tract houses—“put the garage

on this side,” says Watt, “the porch over here.” In an effort to

keep things fresh, the band often asked their friends for lyrics/

songs, and the remaining songwriting duties were divided

among the three guys. Not assigning songs, but rather writing

them when muse struck kept the pressure low. “Nature

Without Man” is one of two songs on the record—along

with “Little Man with a Gun in His Hand”—with lyrics

penned by Chuck Dukowski, bass player for Black Flag from

1977 to 1983, and former manager of Global Booking, the

agency responsible for booking the tours of many bands on

the SST label. While Black Flag and the Minutemen were on

tour, Mike Watt found the lyrics to “Nature Without Man”

penned in a little notebook Dukowski carried around and

asked Chuck if the words could be used in a song.

“I was thinking about morality and the intellectual

impositions we place upon an existence that I feel is without

purpose, or morality,” Dukowski said. “I was saying that

humanity is inherently self-conscious and self-important. We

think our morality is universal when in fact it’s all in our

heads. We’re trapped inside ourselves. Our feelings are what

offer us our grounding and our core intellectual and moral

direction. The heart and mind, the pied piper in the poem,

exact their payment from humanity for their gifts of

self-consciousness and the rushes of fulfillment and

43

understanding. But the main point is that these things exist

only for us and have no reality outside of us.”

Watt describes “Nature Without Man” as “mechanical.” D.

Boon begins with this sorta rolling guitar riff, which, after

two repetitions, is augmented by a typically inventive Watt

bass line and a Hurley drumbeat that incorporates a series of

seemingly disparate stutters and fills that hang together and

form a steady backbeat.

When the verses kick in, Watt’s bass provides the main riff.

D. Boon sings Dukowski’s lyrics, and Hurley adds tight,

varied drum fills in behind every bleat of Boon’s guitar.

When he’s not filling, Hurley plays the cymbals to fill the

void left by Boon’s guitar. After the verses, the main riff is

repeated, and a section that would be the solo in any other

song comes around, featuring diis mechanical main guitar

line. The line is reminiscent of both Gang of Four and Wire,

and reminds me of stuff that would later come out of the

Louisville scene—Slint, Rodan, Crain, et cetera. The pinpoint

precision of the “solo” part of the song acts as a nice

counterpoint to the rolling, comparative looseness of the main

riff.

There’s also the gag that this mechanical-sounding song is

being used to describe the state of man’s consciousness. It

took me a jillion listens to tap in, get the joke, another layer.

“One Reporter’s Opinion” is a collection of slights and

slags on Mike Watt. I, had always assumed that one of the

Minutemen had lifted the lyrics from some rock critic’s

scathing fanzine review and set ‘em to music. Not the case at

all, as it turns out: Watt wrote the song about himself.

44

Watt had been reading James Joyce’s epic Ulysses on tour

and was smitten with the way the book was written. The

action of Ulysses takes place over the course of twenty-four

hours, a single day, during which Joyce shifts his writing style

to fit the mood of the main character, Leopold Bloom.

Watt’s lyrical style veered toward the obtuse. D. Boon

sometimes said that the words Watt wrote should be more

concrete, more inviting to the listeners. Watt decided that he

would shift his lyrical perspective, as Joyce did, and use a

song as a vehicle to pick on himself. He was “relating

expression to a personal experience” by putting his own name

in the song. D. Boon included “One Reporter’s Opinion” on

his side of the record as a validation of the form (and perhaps

in the same humorous light that Watt used when he wrote

lyrics like “big fucking shit / right now, man” specifically so

that D. Boon would yell them during a performance).

D. Boon delivers the lyrics to “One Reporter’s Opinion” over

a hi-hat-driven Hurley drumbeat and a jazzy, inventive Watt

bass line that caroms all over the place. Boon’s guitar fills in

gaps where there are no vocals, culminating in the song’s

outro, during which the whole band plays together. Boon spits

the words out as he begins his bursts of stun guitar.

The lyrics to “One Reporter’s Opinion” are downright clever.

Watt observes that at the end of Ulysses, the book “got

skeletal, [Joyce] is doing question/answers.” The first

lyric—“What could be romantic to Mike Watt? / He’s only a

skeleton”—plays on that notion and pays homage by asking a

question,

then

referencing

the

aforementioned

ques-tion-and-answer form of Ulysses as the answer. Watt is a

45

skeleton—no meat on him, no substance, just “a series of

points / no height, length, or width.”

The next lyric—“In his joints he feels life”—is a double

entendre. Watt either feels life in his joints, where points

meet, thereby reinforcing the previous lyric, or in his joints,

the dope that he smokes. Pain, the song goes on, is the

toughest riddle—not a feeling, but something that Watt has to

ponder, ruminate on, because he’s so dumb.

The final lyrics outline all of Watt’s shortcomings:

“He’s chalk.”

Watt says that chalk “don’t break easy ... it crumbles.” When

used the wrong way on a blackboard, of course, chalk

screeches and sends chills to the base of your spine.

“He’s a dartboard.”

What do you use a dartboard for? As a target, or course,

something to throw projectiles at.

“His sex is disease.”

Another double entendre here—he either needs to go to the

free clinic, or he has his own horrible gender.

“He’s a stop sign.”

He causes things to screech to a halt.

46

Punk Rock Is the New Nostalgia: Side

Watt

A couple years back, I decided to get serious, stop calling

myself a writer and actually do it—try and sit down at the

same time, every day, and work on craft and self-discipline.

The vehicle I chose was my CD collection. My New Year’s

resolution for 2005 was to listen to and review every compact

disc in my rack.

Somewhere in there, probably summer, around the time I was

on the letter P, I got the notion in my head that I should write

a book about Double Nickels for the 33 1/3 series. It’s my

favorite record.

I knew that simply submitting clips from my blog wasn’t

going to cut it, in terms of the application process. I had to

find something concrete that would help me out.

My idea was still in its early stages when We Jam Econo

screened at the Coolidge Corner Theater in Brookline. Me

and my then-roommate Stoops walked over. Before the film

started, we checked the merch booth as the Minutemen

played over the P.A. I bought a brown “econo” shirt. The

woman behind the table thanked me and said that buying

T-shirts live saved them a trip to the post office.

*Ding!*

“You did the film?”

47

“No, my husband did.”

“Is he here? I’d love to meet him!”

She stepped away for a sec, then returned with this guy Keith.

He was very nice, and took relish in answering all my dorky

questions about making the film, doing the interviews, all

that. I mentioned to him that I was going to write the Double

Nickels book for Continuum, and he said “Great! Let me

know how it goes.”

Cut to a few months later. The due date for book pitches was

looming. I found Keith’s email address online and sent him a

message explaining we had met and talked about my book at

Coolidge Corner. Could he hook me up with Watt?

A few days later, an unfamiliar email address in my box.

Watt.

He had been impressed by the Pink Floyd book, and was

amenable to being interviewed.

Holy shit.

Holy shit.

Holy shit.

I made some calls, and booked tickets for California that

night.

48

Come January, my friends John and Kimmee dropped me off

in front of Watt’s place, this big stucco apartment complex in

San Pedro. Within minutes, we were in his van, driving

around town.

I couldn’t believe it.

This guy whose music had been so inspirational to me was

showing me the sights—his sights. That’s where D. Boon

used to live, he said, pointing to an apartment window. That’s

where Minutemen played their first show.

As the afternoon wore on, the amazement, the Is this

happening? wore off. Something else took its place. My Watt

interview was conducted in front of this coffee place on San

Pedro’s main drag. People recognized him, had questions,

wanted records signed—he was humble and appreciative

about everything. Watt has been a boisterous proponent of

punk rock since he discovered it, but there’s more to it than

him talking (and believe you me, dude talks a lot!). He’s

always saying that everyone should start their own band, paint

their own picture, write their own book. It wasn’t a speech to

me, though—it was action. He was helping out, taking an

active part, even though we had never met before I flew out

there. Real names be proof, you know?

“I think that somehow Watt manages to . . . see the current

scene as though it was still 1985,” says Mac McCaughan.

“And I don’t mean it in a retro way ... back then if you were

into punk rock you were part of this community because

everyone wasn’t into [it], and you couldn’t just ... go online to

find out about punk rock. You had to go to a hardcore show . .

. you had to go see bands in the basement of a church or

49

whatever. So it created like a bond between people, I think ...

it was like an extended family, really, and I think that Watt

has managed to keep that kind of perspective on things when

I think it’s easy for people to kind of grow out of that or

something, you know?”

Yes, I do.

* * *

For me, the biggest surprise about Double Nickels was Watt’s

admiration/integration of stylistic elements drawn from James

Joyce’s epic Ulysses. I had never thought of the novel and the

record in the same mental breath, but it makes sense: Ulysses,

like Double Nickels, is one of those grand, commonly

referenced pieces of art (uh-oh, here he goes talking about

art!) that sits on the shelf unappreciated because of the

intimidation factor.

Ulysses takes place over the course of a single day. The

writing style varies from chapter to chapter as multiple

narrators and perspectives come into view. Watt’s side of the

record liberally borrows from Joyce’s novel, using a number

of different lyrical and narrative devices—a real literary

record. It’s not a song-by-song/chapter-by-chapter likeness,

by any means, but the influence can be felt most keenly (but

not solely) throughout Watt’s side.

“It seemed to me then, and still does now,” Watt says, “that

[Joyce] was trying to write about everything. And in a way

the Minutemen were trying to do the same. Never sat down

and agreed to do this or anything, but it seems like we’re

trying to write about everything. The whole world, the

50

history, the future, what can be, could^ be, would be, what

might have been. So, we’re overreaching, and this is the thing

we get out of it—basically, [Ulysses is] about one fuckin’

day! Guy goes to a funeral, takes a bath, beats off on the

beach. You know, so like Minutemen, we were writing

things, and therefore trying to like ... we were obviously

overreaching, so I felt a sympathetic chord, for some reason.”

Patterning an album after one of the masterworks of literature

is certainly overreaching, but the only way progress is ever

made is by challenging oneself. The songs that are on Watt’s

side of Double Nickels succeed way more often than they fail,

even if you’re not into the whole Joycean theme. There are a

bunch of different styles and sounds that come up over the

course of the side. The more you listen to the record, the

deeper into the songs you can get.

I’ve heard Double Nickels a zillion times, and half of that

zillion has been over the last year or so, in researching and

writing this book. When I listen to the album now, I tend to

think of Watt’s side as my favorite. Sure, I listened to D.’s

side the most back in the day, but knowing the story (okay,

stories) behind Watt’s songwriting changed my view. Double

Nickels, obviously, is a long-ass album, and the way that

everyone seems to get through it initially is by picking

favorites and using those songs as touchstones. (“Okay,

‘Political Song’ is on, then there’s a few until ‘Toadies,’ and

then . . . “) My recent immersion in the album allowed me to

spend time with some of the songs on the record, Watt’s side

in particular, that I had previously skipped over while I was

waiting for the next immediately poppy, catchy song to come

up. There are ebbs and flows that add up to this fantastic slab.

51

“Political Song for Michael Jackson to Sing” has always

been among my favorite Minutemen tunes. It’s a perfect mix

of poignant and silly, with great stop/starts and sing-along

parts.

Watt wrote the song for Michael Jackson, no joke. “Wrote a

letter to him, with the lyrics, never got an answer back,” Watt

says. “But actually, that’s why [the song is] called

that, I actually thought of him to sing that song. I thought,

‘Man, if he would sing this song people would think about

sending people off to war.’”

The lyrics for “Political Song” reflect on experiences that

Watt had during his time in the Boy Scouts. The town of San

Pedro was heavy on blue-collar tradition—the men went to

work; the women were homemakers. Watt was put in the Boy

Scouts, like many other young men, to help fill the hole left

by his father working all the time. His first Scoutmaster, Watt

says, a man named Riley, was great. “Hiking up the

mountains a lot, lot of nature, learned a lot about the Indians. .

. . They were teaching us about the nature, the traditions, all

that.”

When Riley retired, though, another Scoutmaster took over,

one that shifted the focus from learning to regiment, from the

outdoors to a more militaristic approach. Instead of going on

hikes, the boys in the Scout troop were made to dress

identically and drill. Watt grew up with the Vietnam war on

the news every day, watching ships depart from his Naval

home town, but “none of it had as much effect on me as how

the Scout thing went from going out there on bigass hikes,

really strenuous, learning stuff about Indians, which the only

other way to learn about was the movies, which the guys

52

making those movies knew nothing about them—Tonto,

Tonto means idiot. This guy says, No, this is the way you

drill, everybody’s uniform, you can’t wear your special little

patches, my Order of the Arrow thing, conformity,

conformity—we’re going to make it the military.”

Watt’s hope was that Michael Jackson would use the lyrics

and make people think more about war, the prospect of

sending boys—some of them just a few years removed

from their Boy Scout experiences—off to fight and die.

The music on “Political Song” is fairly standard punk fare,

atypical for the Minutemen. Riffs are straightforward,

allowing Watt’s lyrics to come to the forefront. As the song

builds, the Minutemen set the listener up. Prior to the music

kicking in, D. Boon intones the words “List monitors arrive

with petition,” then the song immediately revs into high gear.

As the music tapers off at the end of the verse, there’s a pause

reminiscent of the way the song starts, during which D. Boon

immortally says “I must look like a dork.” (The song was

always a favorite during my years working on staff at

Wah-Tut-Ca Scout Reservation in Northwood, New

Hampshire. Short shorts and knee-high wool socks during the

middle of summer? We all knew a little something about

looking like dorks.) Then the song starts again.

So, after two instances of vocals over silence, the listener

expects a third. Instead, the Minutemen deliver a joke. “If we

heard mortar shells,” Boon sings, “We’d cuss more in our

songs / and cut down on guitar solos.”

Pregnant pause.

53

Ridiculously over-the-top guitar solo. There are no mortar

shells to be heard.

Then, back to vocals over silence.

“So dig this big crux”: ten years after the war, there’s no

worry about the draft, the “big sweat point,” but kids in the

Scouts being made to act and dress the same is downright

wrong. Boys shouldn’t have to glimpse into a “wholeness

that’s way too big.” They should simply be allowed to be

boys.

Check out the bass line on “Maybe Partying Will

Help”—pretty funky, eh? It’s not hard to envision the likes

of Flea and Les Claypool perking up their ears upon hearing

the song. When Watt was growing up, the only records with

bass lines that weren’t buried deep in the mix were funk

albums, so he played along with them. It shows.

When the song starts, all that’s audible is the bass, which

sounds lighthearted. In typical Minutemen fashion, the song

becomes at odds with itself very quickly. The whole band

plays at the same time, not taking turns or creating a whole lot

of space for each other, similar to “Theater Is the Life of

You.”

“As I look over this beautiful land,” D. Boon sings on

“Partying,” “I can’t help but realize that I am alone.” From

there, the lyrical stakes get higher as the guitar drops out and

the song slows down, gets more reflective: “Why I’m able to

waste my energy / to notice life being so beautiful / maybe

partying will help.” The contradiction is deep: the narrator,

who is alone, wants to party with other people so that he will

54

stop noticing how beautiful everything is. It’s a bit of a

knot—partying as an antidote to solitude is one thing, but to

eradicate beauty? The lyrical narcissism of these lyrics suits

the quiet mood of the chorus’s music, but then, once again,

the funk bass kicks back into party mode.

The next verse contains an instance of the printed lyrics being

at odds with what’s sung. The album’s sleeve contains the

lyrics “What about the people who don’t have what I have? /

They’re victims of my leisure.” Makes sense, right? For

years, I’ve been hearing “What about the people who don’t

have what I ain’t got? / Are they victims of my leisure?” The