Quality of life and disparities among long-term cervical

cancer survivors

Howard P. Greenwald

&

Ruth McCorkle

&

Kathy Baumgartner

&

Carolyn Gotay

&

Anne Victoria Neale

Received: 14 July 2013 / Accepted: 13 February 2014

# Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014

Abstract

Purpose Little population-based research has been done on

social, economic, and environmental factors affecting quality

of life (QOL) among long-term cancer survivors. This re-

search assesses the impact of disease and nondisease factors

on QOL among long-term survivors of cervical cancer.

Methods In a collaborative, observational study, data were

obtained from cancer registries, interviews, and self-

administered questionnaires. Comparisons of QOL were made

between women with cervical cancer histories and women from

the general population. A total of 715 women 4

–28 years

postdiagnosis were identified from cancer registries in Con-

necticut (N=208), Detroit Metropolitan Area (N=211), New

Mexico (N=197), and Hawaii (N=99). QOL was measured

according to four SF-36 dimensions

—physical functioning,

social functioning, bodily pain, and general health status.

Results Means on SF-36 measures among women with cer-

vical cancer histories were close to or higher than women in

the general population. In a multiple regression analysis,

economic disadvantage negatively predicted physical func-

tioning (B=−13.4, SE=2.1), social functioning (B=−13.2,

SE=2.4), bodily pain (B=−12.6, SE=2.5), and general health

(B=−12.8, SE=2.1). Residence in New Mexico negatively

predicted several QOL dimensions. No impact of race was

detected when income was controlled. Disease stage did not

predict QOL.

Conclusions Cervical cancer does not generally reduce QOL

among long-term survivors. Economic disadvantage and res-

idential location affect QOL through mechanisms yet to be

determined.

Implications for Cancer Survivors Women diagnosed with

cervical cancer have good prospects for high quality of life;

socioeconomic status strongly affects quality of life over the

long term.

Keywords Survivorship . Disparities . Quality of life .

Women

’s health . Cancer

Introduction

Concern with quality of life (QOL) has grown as the life

expectancy of cancer survivors has increased. Racial and

socioeconomic factors reportedly help determine outcomes

of cancer and other diseases [

]. Research has begun to

demonstrate the existence of disparities in health-related qual-

ity of life (QOL) across several nondisease dimensions [

,

Although consequences of survivable cancers and their treat-

ment may become most apparent over the entire life course,

foregoing research has typically examined the experience of

short-term survivors. The research reported here assesses the

impact of both disease and nondisease factors, including race,

socioeconomic status, and geography, on QOL among long-

term survivors of cervical cancer.

According to the American Cancer Society, 12,340 cases of

invasive cancer of the uterine cervix were expected to occur in

the USA in 2013 [

]; an additional 50,000 noninvasive (in

situ) cases can be expected yearly. In 2013, nearly 250,000

H. P. Greenwald (

*)

Sol Price School of Public Policy, University of Southern California,

650 Childs Way, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0626, USA

e-mail: greenwa@usc.edu

R. McCorkle

Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

K. Baumgartner

University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA

C. Gotay

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

A. V. Neale

Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA

J Cancer Surviv

DOI 10.1007/s11764-014-0352-8

women in the USA were alive with histories of invasive

cervical cancer [

]. When women with histories of noninva-

sive disease are added, survivors likely totaled well over one

million. Because cervical cancer frequently occurs among

young women, it is capable of affecting QOL across a broad

range of the life course.

Researchers have reported widespread challenges to QOL

among cancer survivors [

], with low QOL more frequent

among the socially disadvantaged [

]. Several studies have

identified racial and ethnic disparities in QOL among cancer

survivors. Assessments of QOL in breast, colorectal, and pros-

tate cancer have detected poorer QOL among racial and ethnic

minorities than among Caucasian survivors [

]. A study

specifically focused on QOL among cervical cancer survivors

found disparities between Hispanic and non-Hispanic women

on social, emotional, and body image dimensions [

]. A meta-

analysis of 21 studies reported Hispanic survivors to have

significantly lower QOL than other groups [

], and a recent

literature review found African-American cancer survivors to

have lower QOL than Caucasians [

Several generations of researchers have addressed the prob-

lem of reduced QOL among cancer survivors of all back-

grounds [

]. In cervical and other gynecological malig-

nancies, survivors reportedly face special challenges such as

difficulty in marital relations, disappointment due to loss of

childbearing ability, and issues regarding sexuality, sexual

function, and sexual identity [

]. Recent studies and

commentaries have drawn particular attention to long-term

and late effects of cancer and cancer treatment [

The research reported here is intended to help build more

complete understanding of the long-term impact of cervical

cancer on QOL and the determinants of low QOL among

cervical cancer survivors. Unlike many earlier studies, this

research utilizes data drawn from population-based sources

rather than individual treatment facilities, focuses on survivor-

ship well beyond the often-cited 5-year marker, and covers

several varied geographical areas in which key minority groups

are widely represented. Representation of minorities is particu-

larly important in view of growing interest in health disparities.

Methods

Data

The investigators identified women with histories of cervical

cancer through Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results

(SEER) registries in Connecticut, Michigan (Detroit area),

New Mexico, and Hawaii between 2000 and 2003. Led by

principal investigators at four universities (Yale, Wayne State,

University of New Mexico, and University of Hawaii), these

studies were funded independently by the National Cancer

Institute and approved by the Institutional Review Board of each

grantee organization. After deletion of individual identifiers,

data were pooled for the purpose of collaborative analysis. Data

were collected between December, 2001, and December, 2003.

SEER is a population-based cancer surveillance program

supported by the National Cancer Institute. The completeness

and reliability of SEER registries has been widely researched

[

]. SEER records include dates of diagnosis and treat-

ment, stage, basic demographics, and geographic information.

Individuals identified through SEER were contacted by per-

sonnel associated with each individual SEER registry and

interviewed in person or via telephone or sent mail question-

naires. Similar procedures were used at all sites to obtain

physician permission to contact cervical cancer survivors.

Assessments of potential response bias in these data are

reported in publications based on data from two research sites.

In Connecticut, a response rate of 85 % was obtained, and the

respondents did not differ by statistically significant margins

from all cervical cancer survivors in the registry in age, stage,

and county of residence [

]. Metropolitan Detroit reported a

response rate of 62 %, but age and stage of survey respondents

did not differ from those of nonrespondents [

]. The re-

sponse rates for Hawaii and New Mexico were 34 and

16 %, respectively. Comparison of respondents in Hawaii

and New Mexico with 2010 census data suggests overrepre-

sentation of Caucasians at both sites.

Subject selection for the study differed across the four

research sites. The Connecticut protocol restricted accrual to

women with histories of invasive cancer. Research teams

using the other registries accrued both in situ and invasive

cases. At the Connecticut, New Mexico, and Hawaii sites,

research teams interviewed all individuals in the registries

who met the study criteria, whose physicians gave consent,

who could be reached during the study period, and who were

willing to be interviewed. In the Detroit area, an identical

recruitment procedure was used, except that a random sample

of potential subjects was selected and approached. The sam-

pling method and rationale are described elsewhere [

]. A

total of 715 observations were obtained.

To compare cervical cancer patients with national QOL-

related norms, the researchers utilized data from the National

Survey of Functional Health Status (NHS). Conducted in

1990, the NHS was a cross-sectional survey designed to

obtain national normative data for the SF-36, a measure which

will be described below. The sampling frame for the NHS was

drawn from the 1989 and 1990 sampling frames of the Gen-

eral Social Survey, an annual survey of non-institutionalized

adults in the USA. Conducted via telephone and mail, the

NHS oversampled individuals over age 65; 2,474 responses

were obtained, a response rate of 77 % [

Although the NHS and the study of cervical cancer survi-

vors reported here were carried out approximately a decade

apart, comparison of means from the two data sources remains

valid. Strong differences in women

’s health did not seem to

J Cancer Surviv

have developed across this interval. Data on related metrics

for comparable intervals are available from the National

Health Interview Survey. Among women interviewed in

1991, 2000, and 2003, 10.1, 9.3, and 9.6 % reported that their

health status was fair or poor (as opposed to excellent, very

good, or good). Among women interviewed in 1990, 2001,

and 2002, 13.0, 11.9, and 12.3 % reported limitations on

activity caused by chronic disease (as opposed to no such

limitations) [

,

].

Measures

Quality of life among cervical cancer survivors was assessed

according to four composite indicators from the SF-36

—

physical functioning, social functioning, bodily pain, and

general health. The SF-36, perhaps the world

’s most widely

used instrument for assessing health-related quality of life,

consists of eight scales measuring various dimensions of

functional health status [

]. The SF-36 has undergone

extensive reliability and validity testing and assessment of

differences between telephone and mail responses [

Although questions comprising all eight were administered

in the data collection procedure described above, only four are

reported here. Two of the research teams (Yale and University

of Hawaii) used version 1 of the SF-36 instrument, while two

(Wayne State and the University of New Mexico) used version

2, which contains minor modifications of wording for some

items and, for some items, a different number of response

options. Both SF-36 versions continue in widespread use. For

the four dimensions used here, all component items and asso-

ciated response options on versions 1 and 2 of the SF-36

instruments are identical.

The SF-36 physical functioning scale is based on ten

questions asking subjects about their ability to perform activ-

ities such as walking, lifting, bathing, or dressing. The social

functioning scale comprises two questions regarding the fre-

quency and extent to which health problems have interfered

with social activities. The bodily pain scale includes two

items, one focusing on amount of pain experienced in the past

4 weeks, the other on the degree to which pain interfered with

the subject

’s normal work. The general health scale is based

on five questions about the subject

’s self-perceived current

health status and expectations regarding future health.

Analysis

Data analysis focused on testing of four hypotheses. Three are

based on the literature summarized above:

H

1

—Cervical cancer survivors will have lower QOL than

comparable women assumed not to have histories of

cervical cancer.

H

2

—Black and Latina cervical cancer survivors will have

lower QOL than Caucasian survivors.

H

3

—Economically disadvantaged cervical cancer survi-

vors will have lower QOL than non-disadvantaged

survivors.

A final hypothesis was based on the general expectation

that more extensive disease would result in lower QOL:

H

4

—Cervical cancer survivors with histories of invasive

disease will have lower QOL than women diagnosed with

in situ disease; among women with invasive disease,

those with histories of higher stage cancer will have lower

QOL than those at lower stage.

To test H

1

, means on the SF-36 physical functioning, social

functioning, bodily pain, and general health scales were com-

puted, and comparison made with means on these indicators

obtained from the NHS [

]. This procedure was intended to

assess whether QOL of the cervical cancer survivors in this

study differed from the general population of women. In view

of the prevalence of cancer history of any kind among adult

women in the USA during the data collection period (about

6.5 million) [

] in an adult female population approximat-

ing103 million), this procedure compared cervical cancer

survivors with women largely without histories of cancer.

Statistical significance of differences between means on the

sample of cervical cancer survivors and subjects in the nation-

al survey were assessed via z scores.

Cervical cancer survivors were compared with women in the

NHS first for all cervical cancer survivors and then for nonmi-

nority (Caucasian) subjects only. Although limited in scope, a

comparison of nonminority subjects with the national sample

may be more valid than a comparison of all cervical cancer

survivors with the national survey. In the cervical cancer survi-

vor sample as a whole, African-Americans, a key disadvan-

taged group, were underrepresented. Percentages of Asian-

Americans and Latinas in the cervical cancer survivor sample

approximated their percentage in the USA population as a

whole. But most Latinas and Asian-Americans in the cervical

cancer sample resided, respectively, in New Mexico and Ha-

waii, and their responses to a history of cervical cancer may

differ from those of their counterparts in other locations.

The investigators assessed H

2

through H

4

through multiple

regression (OLS) equations predicting the SF-36 variables.

Ethnic category was entered into regression equations as di-

chotomous variables for African-American, Asian-American,

and Hispanic, with Caucasian omitted as a referent. Economic

disadvantage was conceptualized as relatively low income, and

represented in the equations as a dichotomous variable indicat-

ing lowest income quartile among subjects from each catch-

ment area. Lowest income quartile was used as an index of

economic disadvantage rather than a specific dollar figure to

J Cancer Surviv

adjust for differences in income distribution and cost of living

across the four study catchment areas. Locale was represented

as dichotomous variables representing Detroit, New Mexico,

and Hawaii, with Connecticut omitted as a referent.

Separate sets of regressions were computed for all women

in the sample and women diagnosed with invasive diseases. In

the first of these analyses, stage was represented as a dichot-

omous variable (in situ vs. invasive), and in the second as a

continuous three-degree variable (stages I, II, and III). In all

equations, time since diagnosis and age at interview were

entered as contextual variables.

Results

Women accrued in the study were 4

–28 years post-diagnosis;

their ages at time of interview ranged from 26 to 92 years.

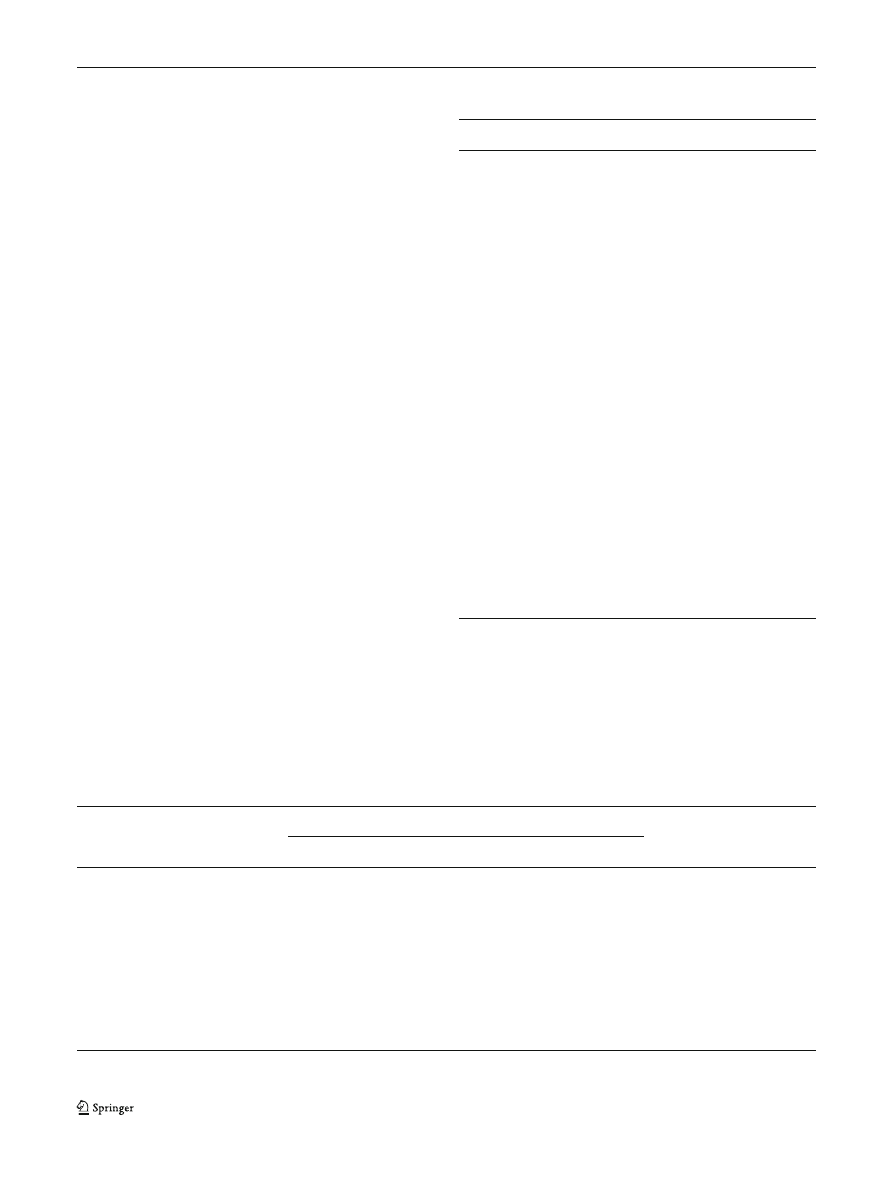

Table

compares the characteristics of the samples obtain-

ed from the Connecticut, Detroit, New Mexico, and Hawaii

registries. Demographic features of each sample reflect differ-

ences in the populations of each SEER site. In addition,

differences across sites are visible in extent of initial disease

(in situ vs. invasive), a consequence of the differences in data

collection protocols of each group of investigators.

Addressing hypothesis H

1

, Table

compares means on the

four SF-36 scales obtained from the cervical cancer survivors

with means from the NHS [

]. Higher scores on the SF-36

scales correspond to higher levels of health-related QOL. For

example, a high numerical score on the SF-36 bodily pain

scale would mean that the subject had, over the preceding

4 weeks, experienced little pain and when pain was experi-

enced it had little if any impact on daily activities. Because

SF-36 scores differ by age in the national sample, and because

age distribution differs across the four cervical cancer survivor

samples, comparisons in Table

are made within 10-year age

groups. Table

presents findings based on all cases accrued.

Generally, means on all four SF-36 scales were higher for

the cervical cancer survivors than the national sample. The

strongest relationships were found within the older age groups

(45 years and over). All statistically significant differences

occurred in relationships in which the cervical cancer

Table 1 Characteristics of sample

Site

Total

p

Connecticut

Detroit

New Mexico

Hawaii

Race

Caucasian (percent)

92.8

84.5

67.5

40.2

75.2

<0.001

Asian (percent)

1.9

0

0

56.7

8.3

<0.001

African-American (percent)

4.3

13.1

0

0

5.0

<0.001

Hispanic (percent)

0

0.5

32.5

0

9.1

<0.001

Age at interview (mean)

55.2

52.0

58.5

51.4

53.7

<0.001

Invasive disease (percent)

98.4

27.1

47.9

30.3

53.2

<0.001

Years since diagnosis (mean)

14.0

9.2

21.4

10.1

12.5

<0.001

Total cases

208

211

197

99

715

Percentages for

“other” or unknown race (N=17) not presented

Table 2 Means on SF-36 dimensions

—cervical cancer survivors vs.

national sample

Age group

Cervical cancer survivors National sample z-score

Dimension: physical functioning

25

–34

91.9

89.1

0.77

35

–44

89.6

88.1

0.97

45

–54

86.6

82.9

2.80**

55

–64

77.9

73.1

2.24*

65 and over 69.6

61.9

2.96**

Dimension: social functioning

25

–34

84.1

84.1

0.017

35

–44

82.7

83.1

−0.196

45

–54

80.8

82.7

−1.48

55

–64

80.9

79.4

0.735

65 and over 83.8

77.0

2.63**

Dimension: bodily pain

25

–34

82.7

79.6

0.75

35

–44

76.6

74.9

0.87

45

–54

74.4

72.1

1.57

55

–64

73.9

66.6

3.73***

65 and over 74.7

63.4

4.57***

Dimension: general health

25

–34

74.6

74.8

−0.053

35

–44

71.3

74.3

−1.71

45

–54

71.6

70.5

0.836

55

–64

68.3

62.9

3.08**

65 and over 67.1

61.6

2.70**

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

J Cancer Surviv

survivors had higher SF-36 scores than the national sample.

Differences of this kind were found for all four SF-36 scales.

Recognizing the underrepresentation of African-

Americans and potential differences between minorities

in New Mexico and Hawaii and their counterparts else-

where, comparison of SF-36 means was also made

using data only on Caucasian cervical cancer survivors.

Findings from this comparison were nearly identical

with those presented in Table

.

Table

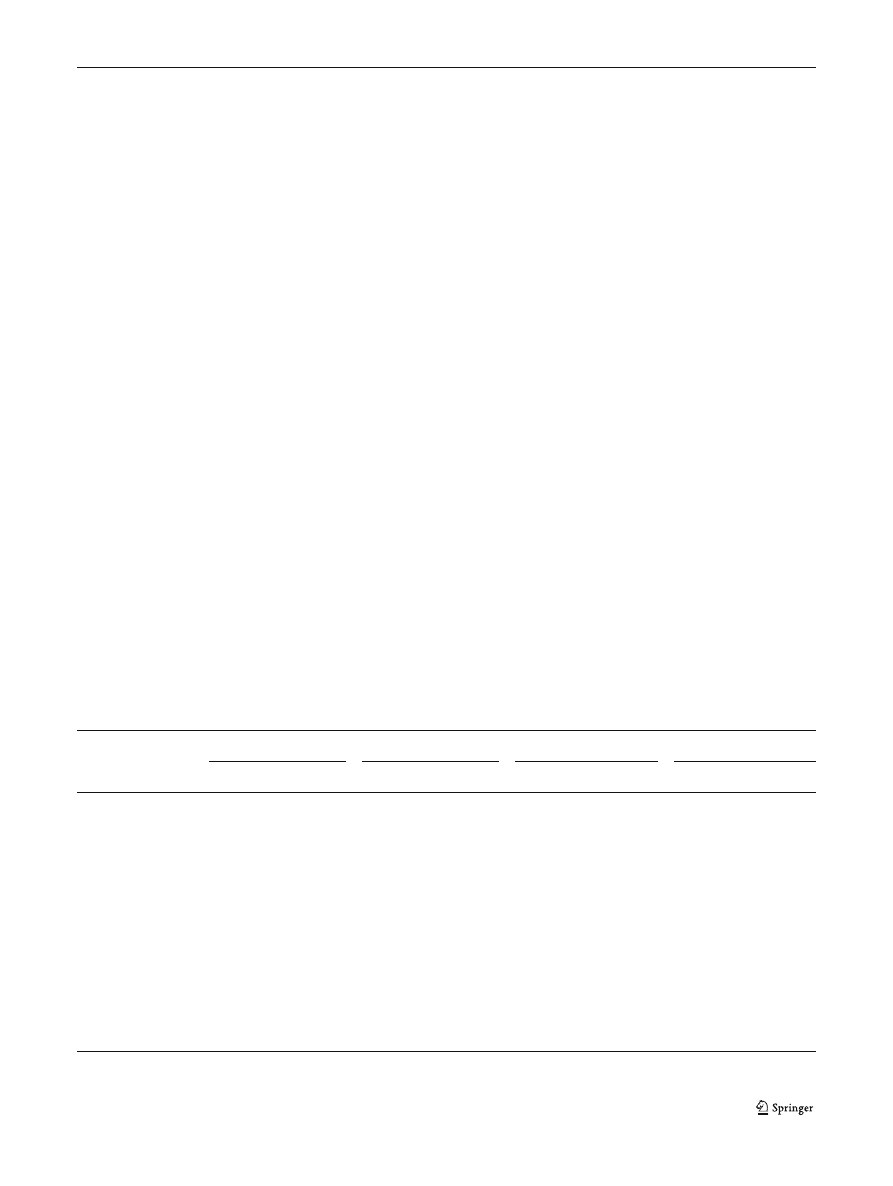

presents coefficients from OLS equations testing

H

2

through H

4

. These equations predict QOL among all

individuals accrued. Age at interview significantly predicts a

lower score on the SF-36 physical functioning dimension

(p<0.001) but has no significant relations with other SF-36

scales. Neither years since diagnosis nor race predicts any of

the dependent variables. Residence in New Mexico predicts

lower scores on three of the four SF-36 dimensions (p<0.05).

Income in the lowest quartile of subjects from each site was

the strongest and most consistent predictor of SF-36 dimen-

sions, economic disadvantage according to this measure

predicting lower scores on all the SF-36 measures

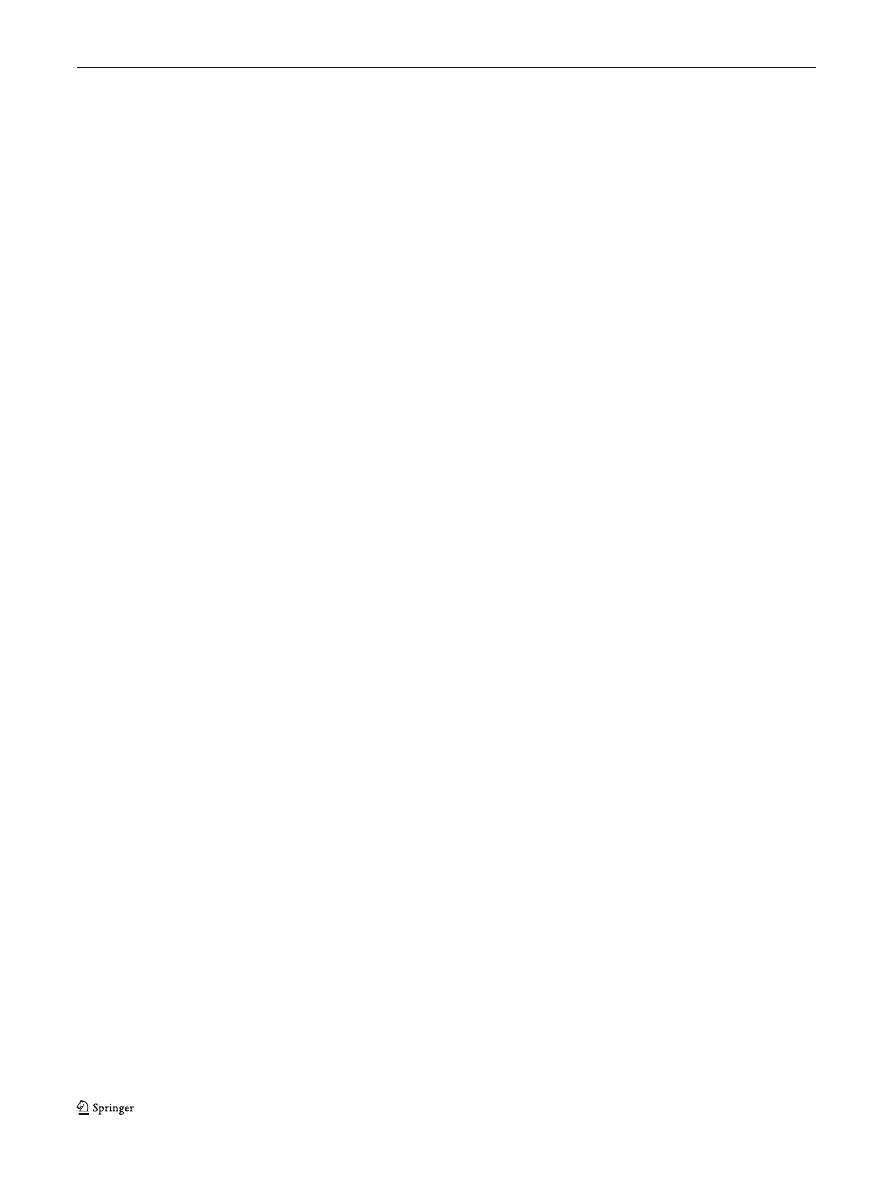

(p<0.001). To aid interpretation of Table

, a table appears

in the

to this article presenting means on the depen-

dent variables by race and research site.

Notably, stage (represented as in situ vs. invasive) did not

predict QOL according to any of the SF-36 measures. The

analysis reported in Table

was repeated for only invasive

cases, the equations including a continuous variable

representing stages I through III. Stage did not predict QOL

in any of these equations; economic disadvantage and resi-

dence in New Mexico continue to strongly predict QOL on all

dimensions.

Discussion

Because this study follows survivors of cervical cancer over

an extended portion of the life course, it provides a more

comprehensive picture of the disease

’s consequences for

QOL than earlier studies. Unlike most previous studies, it

includes subjects who were treated at many different facilities

and reside in a broad range of geographic locations across the

USA. Of the four hypotheses presented above, only H

3

re-

ceived support, highlighting the importance of a key dimen-

sion of socioeconomic status in predicting quality of life

among long-term cervical cancer survivors.

The study suggests that most women who have survived

cervical cancer compare favorably with similarly aged women

in the general population, most of whom have not had cervical

cancer or other malignancies. Among the long-term cervical

cancer survivors on whom this study reports, those in higher

age categories have the most favorable scores on four key SF-

36 scales relative to their counterparts in the general population.

The study reports a strong relationship between economic

disadvantage and low QOL, as indicated by all of the four SF-

36 indicators used in this article. None of the minority groups

represented in this study differed from Caucasian subjects on

any of the four SF-36 scales after economic disadvantage,

residential location, and other background variables had been

controlled. New Mexico residents, regardless of race or eco-

nomic disadvantage, were found to have lower QOL than

cervical cancer survivors accrued elsewhere.

The observation that cervical cancer survivors in the older

age groups have higher QOL than women in the same age

ranges without histories of cervical cancer suggests that an

effective process of adaptation may take place in this disease.

Table 3 Regression of disease features, residence, race, and income quartile on SF-36 dimensions

Physical functioning

Social functioning

Bodily pain

General health

B

95 % CL

B

95 % CL

B

95 % CL

B

95 % CL

Age at interview

−0.54***

−0.72/−0.37

0.02

−0.17/0.22

−0.051

−0.26/0.16

−0.042

−0.22/0.13

Invasive disease

0.17

−4.10/4.34

−0.43

−5.03/4.44

−1.974

−7.06/3.10

−2.385

−6.66/1.89

Years since diagnosis

−0.17

−0.57/0.22

0.10

−0.35/0.55

−0.228

−0.70/0.24

−0.169

−0.56/0.23

Research site

Detroit

−3.48

−9.40/2.42

2.64

−4.10/9.38

−1.653

−8.68/5.37

−3.201

−9.11/2.71

New Mexico

−5.78

−11.56/−0.01

−8.33*

−14.97/−1.76

−7.302*

−14.15/−0.46

−6.380*

−12.15/−6.1

Hawaii

2.49

−5.91/10.89

−2.83

−12.48/6.81

0.952

−8.99/10.90

−0.868

−9.35/7.61

Race

Asian

−2.82

−11.46/5.81

5.89

−4.00/15.79

6.265

−3.95/16.48

0.545

−8.21/9.30

African-American

−1.61

−10.19/6.97

3.98

−5.79/13.77

−1.066

−11.22/9.08

−2.110

−10.65/6.43

Hispanic

−2.15

−9.12/4.81

−3.86

−11.82/4.08

−1.985

−10.29/6.32

0.222

−6.72/7.16

Lowest income quartile

−13.44*** −17.59/−9.30 −13.18*** −17.93/−8.44 −12.555*** −17.46/−7.65 −12.811*** −16.96/−8.66

R

2

0.171

0.079

0.055

0.067

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

J Cancer Surviv

Studies of survivors of cervical and other cancers provide evi-

dence that serious illness can motivate individuals to adopt

positive approaches to life and healthier lifestyles [

] and that

the survivor

’s capacity for resilience may be more important in

determining QOL than the physical features of disease [

,

In a study comparing cancer survivors with people without

cancer histories, the oldest of the survivors evidence the least

QOL impact, potentially due to a longer period of time to adapt

to long-term physical and psychological effects [

]. Alterna-

tively, this observation may be due to increasing perceived

quality of life among older women, but definitive assessment

of this possibility is beyond the scope of the present article.

Variation in QOL among the cervical cancer survivors studied

here may have resulted at least in part from disparities in access to

health services, unmeasured in this study. Since access to health

services is related to income, reduced access may play a part in

reducing QOL among economically disadvantaged cervical can-

cer survivors. The finding in this study, that economic disadvan-

tage predicts relatively low QOL and that race has a relatively

small impact on QOL after disadvantaged economic status has

been controlled, is consistent with earlier research [

].

Residential location has been reported as a determinant of

health-related QOL [

,

], but has not been definitively

studied. Potential explanations may lie in a relative scarcity

of resources in poor communities for health services or non-

health social support. Potentially, differences in perception

may help explain the geographical disparities reported here.

It has been reported that residents of deprived communities

are generally more likely to perceive their health as poor than

residents of nondeprived communities [

It is important to emphasize that, among many individuals

who have survived cervical cancer and other serious diseases,

QOL may be determined substantially by factors independent

of the disease history. The latter possibility is supported by the

observation here that cervical cancer survivors generally enjoy

QOL comparable to or even higher than that of women with

no such histories. Furthermore, studies in a number of fields

indicate that disadvantaged socioeconomic status reduces

levels of perceived life satisfaction and personal happiness,

dimensions akin to quality of life, within largely healthy

populations [

The possibility of sampling bias must be considered in

interpreting this study

’s results. Underrepresentation of minor-

ities (and hence lower-income women) in the sample as a

whole may have biased scores on the QOL scales upward.

Even if such bias were present, the inference would remain

valid that large numbers of women with histories of cervical

cancer enjoy QOL similar to or higher than women without

such histories. If the sample were biased in favor of the

relatively advantaged, moreover, it would seem likely that

the importance of economic disadvantage would be even

greater in a completely unbiased sample. This is because

women with the very lowest income would be the most likely

to encounter barriers to health care and other resources, and

thus be at particularly elevated risk of low QOL.

The findings reported here do not fully characterize the

long-term cervical cancer survivor. Only four of eight SF-36

scales on which data were collected were addressed in this

article. Information on emotional issues captured by two of the

scales not included in the analysis would provide a more

complete picture. In addition, data on sexual adaptation col-

lected in the study but not analyzed here would be of value.

It should in no way be inferred from this study that cervical

cancer does not represent a risk for low QOL across the life

cycle. Although successful adaptation appears to be the norm,

at least 40 % of younger women in this study scored lower on

one or more of the SF-36 scales than the national mean for

their age group. The determinants of lower QOL among these

women and the part potentially played by interaction between

disease and socioeconomic and geographical factors deserve

further investigation. But the findings reported here under-

score the importance of considering social, economic, and

place-related factors capable of reducing QOL in assessing

and treating patients with histories of cancer.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the following grants

and contracts: SEER Special Studies Connecticut Department of Health

2001-345, NO1-PC-65064, NO1-PC-CN 77001, and NO1-PC-67007.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors of this article have any

conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Appendix

References

1. Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J. Race, socioeconomic sta-

tus, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research op-

portunities. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69

–101.

Table 4 Means of SF-36 dimensions by race and site

Physical

functioning

Social

functioning

Bodily

pain

General

health

Race

Caucasian

83.7

82.5

75.7

70.7

Asian

79.5

86.9

82.3

72.2

African-American

74.6

86.1

70.3

64.3

Hispanic

77.3

68.6

65.7

64.2

Site

Connecticut

83.9

82.8

76.4

71.9

Detroit

83.3

86.4

76.1

70.8

New Mexico

79.5

74.0

69.7

66.1

Hawaii

82.6

85.4

80.0

72.2

J Cancer Surviv

2. Kaur JS, Coe K, Rowland J. Enhancing life after cancer in diverse

communities. Cancer. 2012;118(21):5366

–73.

3. Moadel AB, Morgan CM, Dutcher J. Psychosocial needs assessment

among an underserved, ethnically diverse cancer patient population.

Cancer. 2007;109(Supplement 2):446

–54.

4. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures. Atlanta:

American Cancer Society; 2013.

5. De Moor JS, Marietto AB, Parry C, Alfano MA. Cancer survivors in

the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and

implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev.

2013;22(4):651

–70.

6. Weaver KE, Forsythe LP, Reeve BB, et al. Mental and physical

health-related quality of life among U.S. cancer survivors: population

estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer

Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(11):2108

–17.

7. Richardson LC, Wingo PA, Zack MM, et al. Health-related quality of

life in cancer survivors between ages 20 and 64 years: population-

based estimates from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance

System. Cancer. 2008;112(6):1380

–9.

8. Matthews AK, Tejeda S, Johnson TP, et al. Correlates of quality of

life among Africa-American and White cancer survivors. Cancer

Nurs. 2012;35(5):355

–64.

9. Ashing-Giwa KT, Lim J. Examining the impact of socioeconomic

status and socioecologic stress on physical and mental health quality

of life among breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36:

79

–88.

10. Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, et al. Cervical cancer survivor-

ship in a population based sample. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:358

–

64.

11. Luckett T, Goldstein D, Butlow PN, et al. Psychological morbidity

and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: a system-

atic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(13):1240

–8.

12. Powe BD, Hamilton J, Hancock N, et al. Quality of life of African-

American Cancer Survivors: a review of the literature. Cancer.

2007;109(Issuer Supplement 2):435

–45.

13. Davis RM, Cullin JW, Miller LS, Titus M. Physical rehabilitation. In:

Haskell WB, editor. Cancer treatment. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1986.

p. 940

–5.

14. Dobkin PL, Morrow GR. Long-term side effects in patients who have

been treated successfully for cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1986;3:23

–

51.

15. Poplack DG, Brouwers P. Late CNS sequelae in long-term survivors

of childhood leukemia. Proceedings of the fifth national conference

on human values and cancer-1987. Atlanta: American Cancer

Society; 1987. p. 35

–41.

16. Bonica JJ. Importance of the problem. In: Bonica JJ, Ventafridda V,

editors. Advances in pain research and therapy. New York: Raven;

1979.

17. Daut RL, Cleeland CS. The prevalence and severity of pain in cancer.

Cancer. 1982;50:1913

–8.

18. Coyle N, Foley K. Pain in patients with cancer: profile of patients and

common pain syndromes. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1985;1:93

–9.

19. Chapman CR, Syrjala K, Sargur M. Pain as a manifestation of cancer

treatment. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1985;1:100

–8.

20. Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, et al. The prevalence of

psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA. 1983;249:

751

–7.

21. Kornblith AB, Anderson J, Cella DF, et al. Hodgkin disease survivors

at increased risk for problems in psychosocial adaptation. Cancer.

1992;70:2214

–24.

22. Shands ME, Lewis F, Zahlis EH. Mother and child interactions about

the mother

’s breast cancer: an interview study. Oncol Nurs Forum.

2000;27:77

–85.

23. Lewis FM, Hammond MA. Psychosocial adjustment of the family to

breast cancer: a longitudinal study. J Am Med Wom Assoc. 1996;47:

194

–200.

24. Yabroff KR, Lawrence FW, Clauser S, et al. Burden of illness in

cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J

Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1322

–30.

25. Bradley CJ, Bednarek HL, Newmark D. Breast cancer survival,

work, and earnings. J Health Econ. 2003;21:757

–9.

26. Greenwald HP, Dirks SJ, Borgatta EF, et al. Work disability among

cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 1989;29:1253

–9.

27. Corney R, Everett H, Howells A, et al. The care of patients

undergoing surgery for gynecological cancer: the need for

information, emotional support and counseling. J Adv Nurs.

1992;17:667

–71.

28. Bukovic D, Strinie T, Habek M, et al. Sexual life after cervical

carcinoma. Coll Anthropol. 2003;27:173

–80.

29. Juraskova I, Butnow P, Robertson R. Post-treatment sexual adjust-

ment following cervical and endometrial cancer: a qualitative insight.

Psycho-Oncol. 2003;12:267

–79.

30. Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, et al. Early-stage cervical carci-

noma, radical hysterectomy, and sexual function. Cancer. 2004;100:

97

–106.

31. Elit L, Esplem MJ, Butler K, et al. Quality of life and psychosexual

adjustment after prophylactic oophrectomy for a family history of

ovarian cancer. Fam Cancer. 2001;1:149

–56.

32. Robson M, Hensley M, Barakat R, et al. Quality of life in women at

risk for ovarian cancer who have undergone risk-reducing

oophrectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:281

–7.

33. Roussis NF, Waltrous L, Kerr A, et al. Sexual response in the patients

after hysterectomy, total abdominal versus supracervical versus vag-

inal procedure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1427

–8.

34. Herzog TJ, Wright JD. The impact of cervical cancer on quality of

life

—the components and means for management. Gynecol Oncol.

2007;107:572

–7.

35. Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychologi-

cal long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(Issue

Supplement 11):2577

–92.

36. Ganz PA. Survivorship: adult cancer survivors. Prim Care. 2009;36:

721

–41.

37. Mettlin CJ, Menck HR, Winchester DP, et al. A comparison of breast,

colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers reported to the National Cancer

Data Base and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

Program. Cancer. 1997;79(10):2052

–61.

38. Zippin C, Lum D, Hankey BF. Completeness of hospital cancer case

reporting from the SEER Program of the National Cancer Institute.

Cancer. 1995;76:2343

–50.

39. Greenwald HP, McCorkle R, Fennie K. Health status and adaptation

among long-term cervical cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol.

2008;111:449

–54.

40. Bartoces MG, Severson RK, Rusin BA, et al. Quality of life and self-

esteem of long-term survivors of invasive and noninvasive cervical

cancer. J Womens Health. 2009;18(5):655

–61.

41. McHorney CA, Kosinski MA, Ware JE. Comparisons of the costs

and quality of norms for the SF-36 health survey collected by mail

versus telephone interview: results from a national survey. Med Care.

1994;32:551

–67.

42. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 1995.

Hyattsville: Public Health Service; 1996.

. Accessed 23 Dec 2013.

43. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2005.

Hyattsville: Public Health Service; 2006.

. Accessed 23 Dec 2013.

44. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short form health

survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med

Care. 1992;30:473

–83.

45. McHorney CA, Ware JE, Rachel Lu JF, et al. The MOS-36 Short

Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling as-

sumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care.

1994;32:40

–66.

J Cancer Surviv

46. Ware JE, Kosinski MA, Gandek MA. SF-36 health survey: manual

and interpretation guide. Boston: New England Medical Center, The

Health Institute; 1993.

47. Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER Cancer

Statistics Review, 1975-2008. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute;

2008.

http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/

. Accessed 17 Jul 2011.

48. Greenwald HP, McCorkle R. Remedies and life changes

among invasive cervical cancer survivors. Urol Nurs.

2007;27(1):47

–53.

49. Bardwell WA, Natarajan L, Dimsdale JE, et al. Objective cancer-

related variables are not associated with depressive symptoms in

women treated for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:

2420

–7.

50. Scheier MF, Helgeson VS. Really, disease doesn

’t matter? A com-

mentary on correlates of depressive symptoms in women treated for

early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2407

–8.

51. Do DP, Finch BK, Basturo R, et al. Does place explain racial health

disparities? Quantifying the contribution of residential context to the

Black/White health gap in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:

1258

–68.

52. Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD. Rural-urban disparities in

health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1050

–7.

53. Sathyanarayanan S, Brooks AJ, Hagen SE, et al. Multilevel analysis

of the physical health perception of employees: community and

individual factors. Am J Health Promot. 2012;26(5):e126

–36.

54. Barger SD, Donoho CJ, Wayment HA. The relative contributions of

race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, health, and social relationships

to life satisfaction in the United States. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(2):

179

–89.

55. Yang Y. Social inequalities and happiness in the United States: 1972

–

2004: an age-period cohort analysis. Am Sociol Rev. 2008;73(2):

204

–26.

J Cancer Surviv

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Becker The quantity and quality of life and the evolution of world inequality

health behaviors and quality of life among cervical cancer s

Quality of life of 5–10 year breast cancer survivors diagnosed between age 40 and 49

Intertrochanteric osteotomy in young adults for sequelae of Legg Calvé Perthes’ disease—a long term

Cho Chikun's encyclopedia of life and death part three a

Cho Chikun's encyclopedia of life and death part one ele

Quality of Life in Women with Gynecologic Cancer in Turkey

A Matter of Life and Death By Derdriu oFaolain

Quality of Life 100

Cho Chikun s encyclopedia of life and death part three a

Jack London Love of Life and Other Stories

89 1268 1281 Tool Life and Tool Quality Summary of the Activities of the ICFG Subgroup

Sterne The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

Long term Management of chronic hepatitis B

THE CHEMICAL COMPOSITION AND SENSORY QUALITY OF PORK

Master Wonhyo An Overview of His Life and Teachings by Byeong Jo Jeong (2010)

Three Important Qualities Of Christ's Life

więcej podobnych podstron