We Have Never Been Latourian:

Archaeological Ethics and the Posthuman

Condition

T

IM

F

LOHR

S

ØRENSEN

This article is motivated by the recent proposal of a

‘symmetrical’ approach in

archaeology. Symmetrical archaeology takes its starting point in Bruno Latour

’s

contention that we have

– paradoxically – always been able to practice a

symmetry

between

humans

and

non-humans,

and

that

we

have,

simultaneously, also always been able to distinguish humans from non-

humans. It has been argued by its proponents that symmetrical archaeology

has ethical ramifications, yet this dimension remains only vaguely described in

the current literature. This article seeks to explore what it might mean to extend

ethics from humans to non-humans, and it contends that such a relationship is

already being practised. Archaeological practice and heritage management are

salient examples of how the ability to distinguish and conflate humans and

non-humans frequently occurs along the lines of a number of undeclared and

un-critiqued political and ethical logics. In effect, some things and some people

are embraced by an empathetic embroidery, while others are disenfranchised.

The article contends that a symmetrical principle in archaeology and heritage

poses central ethical challenges to the ways in which the archaeological Other is

defined and identified.

Keywords: symmetrical archaeology; humans; non-humans; ethics; body;

heritage

INTRODUCTION

Let me first briefly tell you the story about

Lasse. Lasse was a 10-year-old boy from

Denmark, who had cancer in one of his feet

and had to have it amputated (Skovsbøl 2010).

After learning that the cancer meant that he

would lose his foot, Lasse became very con-

cerned with the destiny of his foot and was

determined that it should not simply be dis-

carded as ordinary tissue waste, which is the

norm in Danish hospital practice. Lasse wanted

to part formally with his foot, and his parents,

the hospital and the local vicar agreed to his

wish in order to aid his emotional healing pro-

cess. Before his foot was amputated, the family

held a farewell dinner for Lasse

’s foot, where the

entire table was decorated in black: black table

cloth, black napkins, black candlelight, black

balloons. Upon the amputation of the foot, the

family held a formal funeral for it, keeping the

foot in a small, white coffin in the home until the

day of the funeral. Then the family went to the

cemetery and buried the foot, and the vicar held

ARTICLE

Norwegian Archaeological Review, 2013

Vol. 46, No. 1, 1

–18, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2013.779317

Tim Flohr Sørensen, Aarhus University, Department of Culture and Society, Section for Archaeology Moesgård, 8270

Højbjerg, Denmark. E-mail: farktfs@hum.au.dk

© 2013 Norwegian Archaeological Review

a eulogy over the severed body part. The funeral

was followed by a wake, where the dining table

was dressed in a kaleidoscope of colours and

spring flowers to celebrate that the cancer was

gone and that Lasse had been equipped with a

new

– artificial – foot to move on in life.

This story may remind us of Bruno Latour

’s

observations on the complicated relationship

between humans and non-humans, between

people and things. Defining

‘modernity’ as

the great divide, Latour (1993) argues that

there are no

‘premodern’ or ‘postmodern’ as

opposed to

‘modern’ humans: human beings

have always been able to distinguish humans

from non-humans, and they have always had

the capacity to confuse humans and non-

humans. Here, Latour (1993, pp. 10

–11, 47)

speaks of

‘translation’ or ‘mediation’ as

opposed to

‘purification’. ‘Translation’ and

‘mediation’ define the world as a mixture of

nature and society, while

‘purification’ estab-

lishes

a

clinical

ontological

distinction

between humans and non-humans. In this,

Latour

’s (1993, p. 11) point is that the non-

modern gaze considers the world through

both lenses simultaneously and that even

moderns have always been able to conflate as

well as separate humans and non-humans in

practice, but have never been explicit about

the relationship between the two categories

(Latour 1993, p. 51). Accordingly, things are

always integral parts of human society and

never apart from it (Latour 1992, 2005,

pp. 71

–72).

Latour (1993, pp. 142

–145) goes as far as to

propose a

‘parliament of things’ where objects

are democratized as a result of their inherently

hybridized ontology with people, being essen-

tially enmeshed in human existence. He argues

that

‘[b]y defending the rights of the human

subject to speak and to be the sole speaker, one

does not establish democracy; one makes it

increasingly more impracticable every day

’

(Latour 2004, p. 69). In Latour

’s view, true

democracy can emerge only if non-human

voices are uttered with the aid of human repre-

sentatives, thus indicating, effectively, that we

have never been (truly) democratic. Latour

would have us give democratic voice to non-

humans, i.e. to animals, tools, pottery, bronze

swords, jewellery, buildings, space ships, etc.,

because they constitute an imbricated part of

the

‘common world’ of humans and non-

humans, emerging as a

‘collective’ rather

than a

‘society’ (Latour 2004, pp. 47, 53–54,

62, ch. 5, 2005, p. 75).

The question is whether this is a valid

proposition. Many archaeologists would

probably answer readily and with little hes-

itation in the negative. Whereas Latour

(1993) argues that

‘we have never been mod-

ern

’, because ‘we’ (i.e. human beings) have

never been able to categorically separate

humans from non-humans or nature from

society, the modernist ground on which

archaeologists rest (Thomas 2004) implies

that that they have never been Latourian,

i.e. they have always been able to discrimi-

nate humans from non-humans. As Tim

Dant argues, most of the time moderns

hardly give any thought to things and, if we

do,

‘we regard them as “mere” objects that

do not in any way compete with humans for

status as beings. Objects are there for us to

use and dispose of in whatever way we wish;

we may treat them well or badly without any

concern for their rights or feelings because

they have none

’ (2005, p. 62).

In this, Dant cites a pedestrian rejection of

the democracy of things and alludes to a

potential ethics beyond that of humans

(we may of course observe that such a posthu-

man ethics is already realized in notions of

animal rights and animal welfare). This collo-

quial attitude to things, it may be argued, is

merely a stubborn and mind-numbingly auto-

mated reproduction of the Cartesian prejudice

that things are inanimate, dead matter and

hence inferior to humans. Thus, the capacity

to distinguish subjects from objects, humans

from non-humans, nature from society has

simply become part of an un-critiqued mod-

ern, Western doxa (Latour 1993, pp. 97

–103,

2004, pp. 45

–46).

Extending this logic to the ethical dimen-

sions of archaeological remains, we need to

2

Tim Flohr Sørensen

challenge the status of the human as a priori

privileged over the non-human, which calls for

a rethinking of a number of relations; for

instance, the relation between that which is

integrated into the organic body as opposed

to detachable and inorganic, non-bodily arte-

facts or the animate being in relation to the

inanimate object. Or, in other words, how,

why and with what legitimacy do archaeolo-

gists separate the prosthetic hand from the

organic hand, the amputated hand from the

whole body, the glove from the hand, the

wedding ring from the finger on the hand or

the hand from the tattoo on the hand? Do they

make arbitrary distinctions based on contem-

porary ontologies and ethics or is the aim to

try to approximate a hypothetical Other in

the past and her or his notions of human and

non-human, body and non-body?

The symmetrical relationship between hu-

mans and non-humans, and the

‘democracy’

that Latour advocates, should not be entirely

unfamiliar to archaeologists as it has, argu-

ably, already been effectuated for quite some

time in the field of heritage, in the sense that

things

– or, rather, some things – are protected

and treated as if charged with ethical rights

similar to those of humans (see also Harrison

2012, ch. 9). This discourse works on two

levels. One seeks to protect things from

destruction, while the other seeks to give peo-

ple access to objects and places. In discourses

on

‘heritage’ and ‘cultural property’ as unique

or irreplaceable the position of things is

uncannily similar to that of humans and the

rights of humans. On the one hand, institu-

tions such as UNESCO stipulate in the

Convention Concerning the Protection of the

World Cultural and Natural Heritage that the

disappearance of items of cultural heritage

‘constitutes a harmful impoverishment’ of all

nations of the world, which implies that the

loss of cultural heritage is a loss for humans

and for human society. On the other hand, the

widespread discourse on heritage in national

heritage agencies, in political agendas and at

historical tourist sites rarely specifies that pro-

tection of things from the past is decided by

humans and in the interest of humans, but

simply disseminates

‘heritage’ as a value in

its own right with an intrinsic and irreplace-

able importance (see Smith 2006, Waterton

and Smith 2009). However, only certain things

are cherished as indestructible or inviolable, or

so important that people should be given

access to them: some items become cherished

while others are relegated to a shadow exis-

tence as anonymous, mass objects or because

they are classified as undiagnostic or unrepre-

sentative. The political or moral power of

things that Latour (1992) identifies is thus

already a reality, but it issues forth more as

an oligarchy than a democracy, because the

privilege of having a

‘voice’ and being ‘heard’

is granted only to a few lucky things selected

by their spokespersons (or lobby) in current

heritage practice (see also Meskell 2010).

So, while Latour argues that there is an

unproductive asymmetry between humans and

non-humans, reproduced through the modernist

agenda, we may extend the problem into the

(modernist) practice of archaeology and heri-

tage. After introducing symmetrical archaeol-

ogy and its ethical contours, I explore a

number of cases and scenarios from archaeol-

ogy and the heritage industry that are ethically

charged, but which nevertheless tend to fall

under the radar of explicit ethical scrutiny,

despite being invested with explicit ethical deci-

sions and highly political consequences. This

allows for a critical scrutiny of the limits of ethics

and the range to which the symmetrical

approach has bearing for the field of ethics in

archaeology.

FROM HUMAN ETHICS TO MATERIAL

ETHICS

The modernist division of humans and

non-humans has been challenged within, for

instance, technology and culture studies in

recent decades. In an influential article Donna

Haraway (1985) thus proposed three

‘bound-

ary breakdowns

’, disputing the margins of,

respectively, humans and animals, organism

and machine, and the physical and the

We Have Never Been Latourian

3

non-physical (Haraway 1991, pp. 151

–154).

The work of Haraway, among others, has

been part of an expanding interest in social,

technological and philosophical imbrications

of humans and non-humans, and in the poten-

tial transcending of humanism and the privi-

leged position of the human. An array of

studies into posthumanism, new materialism

and speculative realism addresses ethical chal-

lenges to contemporary and future societies

(see,

e.g.,

Barad

1998,

Hayles

1999,

Badmington 2000, Bryant et al. 2011, van der

Tuin and Dolphijn 2010, Pyyhtinen and

Tamminen 2011, see also Verbeek 2005, 2006,

2011), while the implications are rarely seen as

historical let alone archaeological (but see

Dawney et al. in prep.).

Within archaeology, the Latourian and

posthumanist notion of a non-discriminatory

approach to humans and non-humans has

been embraced explicitly by the branch of

so-called

‘symmetrical archaeology’ (e.g.

Olsen 2003, 2012, Domanska 2006, Witmore

2006, 2007, Shanks 2007, Webmoor 2007,

Webmoor and Witmore 2008, Normark 2010).

This approach calls attention to the symmetry

between humans and non-humans in the

archaeological discipline, effectively levelling

the modernist opposition of people and things.

It thus highlights a number of interesting and

potentially necessary redirections in archaeol-

ogy, yet it also raises a number of challenging

issues.

The aim of symmetrical archaeology is,

allegedly, not to invoke any

‘simplistic’

equivalence of humans and non-humans, but

rather to appreciate their

‘distributed collec-

tive

’ and the complex entanglement of people

and things (Witmore 2007, p. 547). Bjørnar

Olsen (2003, 2006) thus takes up Latour

’s

notion of a democracy of things, and argues

that archaeology has overlooked things.

Despite its being the very

‘discipline of things’

(Olsen 2003, p. 89, Olsen et al. 2012), the focus

is always drawn to meta-theory, politics and

society. Instead, he appeals for an archaeol-

ogy that can embrace how non-humans and

humans are created in mutual collaboration

(see also Hodder 2012). He asks for an

approach that allows us to appreciate

‘how

objects construct the subject

’ (Olsen 2003,

p. 100) and how things are part of political

processes (Olsen 2006, p. 17). Olsen wishes not

only to include non-humans as social partici-

pants at an analytical level, but even more to

be

‘pragmatic’ about the accounts of archae-

ological and historical

‘collectives’ (Olsen

2007, p. 586).

For Michael Shanks, the politics of this

agenda is also about

‘who we are’ (2007,

p. 591), and the symmetrical

‘attitude’ is thus

about opening up to new identities for people

and things. In this, it is important to stress that a

symmetrical approach allegedly does not col-

lapse humans and non-humans into one uni-

form identity: things are not the same or equal,

just because they are approached as symmetri-

cally constituted (Olsen 2012, pp. 211

–213,

Olsen et al. 2012, p. 13), but are instead partici-

pants in

‘heterogeneous networks’ (Shanks

2007, p. 593, Witmore 2007, p. 550) or

‘mix-

tures

’ (Witmore 2007, p. 559, Webmoor and

Witmore 2008, p. 59, Olsen 2010, pp. 132

–

136). As such, there are no autonomies: all

objects and subjects are entangled and depen-

dent (Hodder 2012). These new identities

– and

their symmetrical ontology

– obviously have

bearings on the political and ethical aspects of

the beings that inhabit the world.

Interestingly, Christopher Witmore anno-

unces in his manifesto for symmetrical archae-

ology that the symmetrical levelling is

‘neither

axiological nor ethical

’ (2007, p. 547). Soon

after he argues that

‘a symmetrical archaeol-

ogy builds on the strengths of what we do as

archaeologists

’ (Witmore 2007, p. 549).

For some, however, it may be somewhat dif-

ficult to see how the practice of archaeology can

be divorced from ethics, and it is particularly

curious to see an ethical claim abandoned in

the light of symmetrical archaeology

’s necessary

association with Latour

’s democratizing project.

So, if anything, symmetrical archaeology is

involved in a political project, and it seems to

me to be naive to consider practice and politics

disconnected from the ethical field.

4

Tim Flohr Sørensen

A number of writings under the moniker of

symmetrical archaeology have indeed expli-

citly highlighted ethics as a direct consequence

of the symmetry principle. For instance,

Shanks (2007) declares that symmetry is pre-

cisely an ethical principle, even though the

exact implications remain somewhat unclear.

It seems that a postcolonial attitude to the

representation of the past is part of this ethical

and political principle, revolving around criti-

cal judgements of how archaeologists may be

‘speaking’ for the past in its absence (Shanks

2007, p. 592). Ewa Domanska (2006, p. 172)

makes the ethical stakes slightly more explicit,

arguing that a material ethics implies, in part,

that things are not simply seen as commodities

or tools for human use, and she cites Silvia

Benso

’s critique of the objectification of

things, i.e. that things are reduced to objects

(Domanska 2006, p. 183). While this line of

thinking is not elaborated much further and

stops short of making specific claims as to

pragmatic ethics, Timothy Webmoor suggests

that

‘care’ for things through archaeological

practice, representation and heritage

‘eco-

logy

’ is in essence a care for ‘our collective

selves

’ (Webmoor 2012, p. 21). Olsen (2012,

pp. 219

–220) adopts a similar approach in

moving towards an ethical

‘care’ for things,

emphasizing that such an embrace is not

achieved by anthropomorphizing non-humans,

but can instead be exemplified in the prac-

tical curation of things in museum collections

and archaeological conservation. Here, Olsen

argues, things are not cherished for the ways in

which humans may see them as valuable, beau-

tiful, meaningful or as commodities, but simply

for what they are

‘in their own thingness’ (Olsen

2012, p. 220, but see also Morphy 2010).

HIERARCHIES OF HERITAGE

While proponents of the symmetrical principle

in archaeology have claimed to identify a lack

of specific ethical consideration of things in

the contemporary world, it may, nevertheless,

be argued that certain archaeological objects

are in fact treated as if endowed with an

unquestionable value, similar to that which is

otherwise ascribed to humans within the mod-

ernist paradigm. These non-human objects do

not simply remain classified under the generic

token of

‘archaeological evidence’ or ‘prehis-

toric remains

’. They become canonized as

‘cultural heritage’, and are certainly attributed

with power not unlike the one normally

referred to under the heading of

‘fetishism’.

Objects of heritage are thus indestructible,

secularly sacred, due to their uniqueness or

their perceived cultural value, conforming

very well to Latour

’s notion of the ever-

present conflation and exchange of human

and non-human

‘competences’ (Latour 1999,

p. 182).

In a sense, some non-humans thus achieve a

status of having

‘thing rights’, being protected

by international as well as national conven-

tions in what has been characterized as a

‘heri-

tage cult

’ (Raj Isar 2011, p. 39), framing an

unquestionable imperative to protect, con-

serve and disseminate whatever is raised to

the category of

‘cultural heritage’ (see also

Domanska 2006, pp. 177

–178). Interestingly,

these rules and regulations serve to protect

selected non-humans against humans (for an

illustrative case, see Bille 2012). And when

these fetishized non-humans are from time to

time endangered, destroyed or

‘executed’ as if

they were humans, as in the case of the

Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan, the reac-

tion from certain members of the international

community sometimes seems to indicate that

precisely these non-humans are at least as pre-

cious as humans (Holtorf 2005b, Harrison

2012, pp. 186

–188, see also Francioni and

Lenzerini 2003).

But we are still left with the question: why

should some things be preserved? Surely, we

cannot proceed along the lines of the wide-

spread happy-go-lucky attitude in the heritage

industry that simply prescribes that

‘heritage

is good for you

’ (as coined by Furtado 2006,

but see also Harrison 2009, Smith 2006), based

on the often unqualified dogma that

‘heritage’

is circumscribed by an unquestionable time-

less and eternal value, that it is something that

We Have Never Been Latourian

5

we can all learn from, something whose

absence would deprive us of cultural identity

and humanity. In this perspective,

‘heritage’ is

meant to outlive the temporal scale of indivi-

dual human life and become a shared resource

for all humanity at all times, e.g. in

UNESCO

’s concept of ‘outstanding universal

value

’ (Cleere 1996, Jokilehto 2006). Hence,

objects and places of cultural heritage are

canonized as particularly valuable for humans

and not as things in their own right (Olsen

2012, pp. 218

–219), which is not surprising as

long as the term cultural heritage is main-

tained (Webmoor 2012, p. 15).

The World Heritage Declaration is, never-

theless, one thing, while the more mundane

and local canonization of ancient and histor-

ical artefacts and places remains less explicitly

conceived (see also Omland 2006). In these

cases the reason why only some non-human

remains are protected against destruction

remains largely unstated, which means that

numerous non-humans are readily given over

to oblivion once the archaeologists have

counted the postholes and the contractor is

ready to build the superhighway. In this

light, it appears that we happily accept that

only some non-humans enjoy rights of protec-

tion (see also Webmoor 2012, p. 14).

Another set of issues emerges when we turn

from heritage as protection to heritage as the

right to access. The latter can readily be con-

sidered an extension of the Latourian demo-

cratization of things, because giving access to

things is a way of letting them be

‘heard’.

However, the majority of archaeological arte-

facts are never made available to public scru-

tiny, but stored in museum facilities beyond

public access. In addition, items that are

deemed unimportant and unworthy of preser-

vation are subjected to experiments and

destruction in the name of science, where

objective knowledge of their composition,

date and provenance is achieved. Frequently,

samples are extracted from logs of wood, pot-

tery, bone fragments and metals, but not

necessarily to shed light on the sampled arte-

fact itself. Oftentimes, the sampled artefacts

serve as statistical material that helps to illu-

minate more important finds.

The politics of ostracisation stand in sharp

contrast to the common archaeological atti-

tude to the mundane and the trivial as offering

the most informative access to the reality of

the past (Lucas 2012, p. 125). Whereas the

dramatic and unique are often mistrusted in

archaeology as extraordinary and unrepresen-

tative of past societies, the repetitive produc-

tion of flint artefacts, mud bricks, pottery, pins

and pendants is argued to offer access to a

more complete picture of past realities. This

seems to suggest that there is a tension

between the widespread canonization of

objects

such as the

Ur Standard,

the

Trundholm Chariot, the Terracotta Army,

Stonehenge,

Great

Zimbabwe

and

the

Acropolis (Fig. 1) and archaeological knowl-

edge production based on the myriads of

undiagnostic potsherds, flint flakes and bone

fragments that are excavated throughout the

world, but which readily fall into popular

oblivion,

because

they

are

not

made

accessible.

Metaphorically speaking, and expanding

on Latour

’s laconic terminology, we may

observe how some non-humans

– the ‘faceless

minions

’ (Witmore 2007, p. 552) – are forced

to do the filthy slave labour for an imperialist

archaeology and a heritage industry on a mis-

sion to colonize the past, providing for an

enlightened present. These anonymous, disen-

franchised artefacts are excavated simply to

do the hard work of manufacturing raw data

for the sake of the celebrity non-humans on

the canonized heritage lists, contextualizing,

illuminating and framing the celebrity non-

humans. Within this scheme of things, these

non-humans function as the wretched masses

that continuously build nations, narratives

and knowledge, but at the same time are trea-

ted as replaceable and disposable second-class

heritage citizens; they can be exploited at our

convenience and then relegated to the shadow-

life of statistical material (Fig. 2). As such,

many non-humans are treated in the same

way as colonial rulers treated the colonized,

6

Tim Flohr Sørensen

‘with little or no concern for their welfare’

(Dant 2005, p. 62). They are, after all,

‘just

things

’. While some non-humans find a place

in the limelight, others are stowed away in

storage facilities where the sun never shines.

Hence, if there is any legitimacy in inscrib-

ing non-humans into a democracy, it also

means that mundane, trivial and non-

diagnostic artefacts should be incorporated

more conspicuously into the heritage agenda,

as they traditionally have been in archaeology

(Lucas 2012, ch. 2), so that

‘heritage celebri-

ties

’ are not privileged over the masses. This is

a challenge that highlights how ethically and

politically charged a symmetrical principle in

archaeology and heritage practice needs to be,

if we are to buy into its agenda (see also Solli

2011,

Harrison

2012).

A

symmetrical

relationship

between

humans

and

non-

humans can never be merely analytical

(Witmore 2007, p. 547), and cannot exclu-

sively

concern

the

relationship

between

humans and non-humans, because it essen-

tially hinges on a

‘flat ontology’ (Harman

2009, pp. 207

–208), and hence advocates a

levelling not just of people and things, but

also of non-humans among other non-

humans. Rodney Harrison thus argues that

the

‘flat notion of the social’ necessitates an

‘inclusive sense of ethics that acknowledges

not only the universal rights of humans, but

also those of non-humans

’ (2012, p. 218).

Recognizing the difficulties in defining what

constitutes

the

rights

of

non-humans,

Harrison stipulates that part of the problem

may be that we are not accustomed to

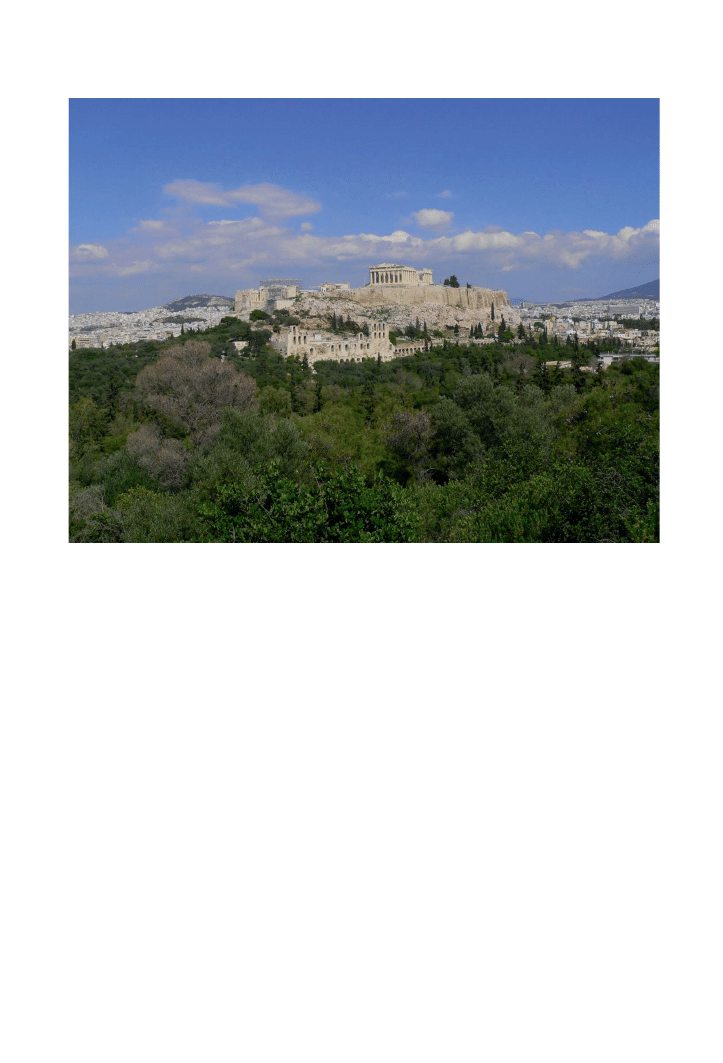

Fig 1. The Acropolis, Greece: a renowned and respected heritage celebrity. Photograph by Troels Myrup

Kristensen. Used by kind permission.

We Have Never Been Latourian

7

communicating with non-humans, and that

the exchange between humans and non-

humans is temporally contingent, or emer-

gent. The latter in particular implies that ethi-

cal relations are not necessarily stable or

eternal, but that they can change and dissolve

(Harrison 2012, pp. 218

–219).

ETHICS AND THE (POST)HUMAN

BODY

In effect, this implies that the ethical issues

addressed by Latour and the posthuman para-

digm are not entirely irrelevant for archaeology,

no matter how modernist its foundation may be,

and are not just of theoretical or conceptual

import. In an archaeological perspective, the

question emerges as to whether modernity

’s

immediate readiness to ascribe ethical rights

solely to humans (and animals) does justice to

the communities that archaeologists excavate;

communities that may precisely have seen a

piece of jewellery as inseparable from the buried

individual or who would have experienced an

artefact that archaeologists consider to be a

‘mere thing’ as deeply animated by a soul or

constituting a full, independent ontological

form of existence in its own right. In this light,

the modern, archaeological relegation of such

‘things’ to the status of dead, inanimate matter is

hardly justifiable.

Latour

’s (1999, p. 182) call for incorporat-

ing things and people into a flat ontology,

where humans and non-humans overlap and

are capable of swapping competences and

properties could, accordingly, be seen in the

light of much older anthropological insights

into the relationship between humans, things

and the animated world. Under the headings

of fetishism, animism and perspectivism, we

know from ethnography that objects are

sometimes experienced and conceptualized as

embodied parts of people or as having imma-

nent power (e.g. Pietz 1985, 1987, 1988, Spyer

1998, Viveiros de Castro 1998, 2004, Pels

1998, 2010, Pedersen 2001, Hornborg 2006,

Holbraad

2007,

Willerslev

2007).

Such

enchantments of non-humans may be more

difficult to detect in an archaeological or his-

torical context, but in light of ethnographic

observations it seems naive to automatically

exclude the possibility that certain finds could

have played an active role in past societies as

enchanted objects with embedded power or

personality, or even with their own indepen-

dent subjective perspective on the world. In

this light, the question is whether archaeologi-

cal artefacts were sometimes circumscribed in

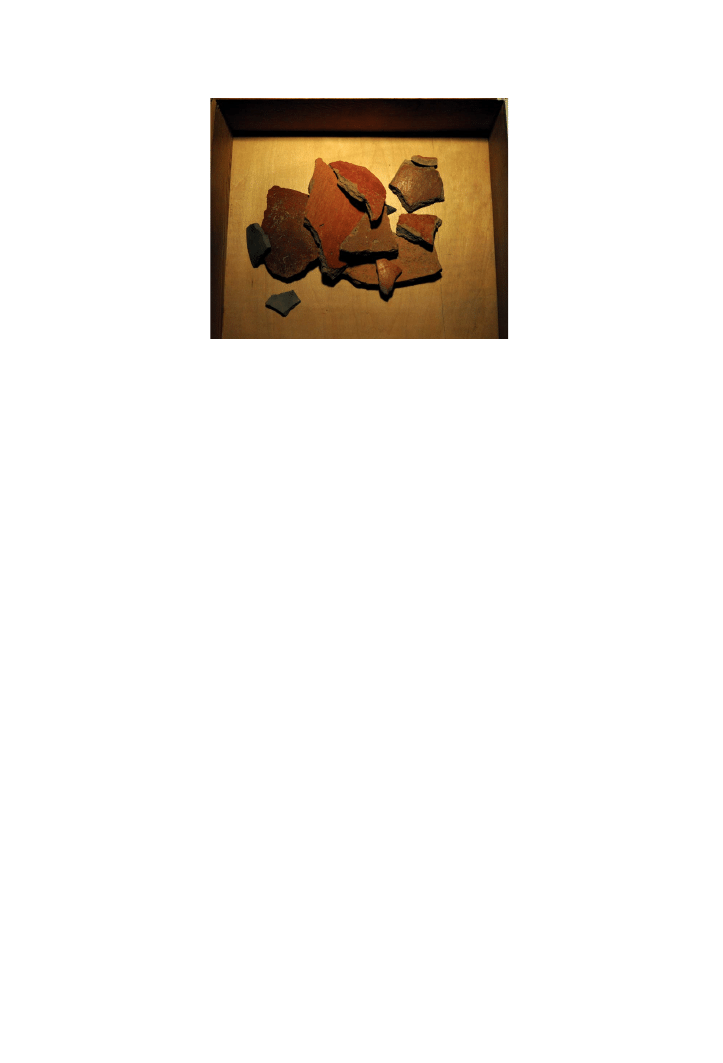

Fig. 2. Undiagnostic potsherds, or

‘faceless minions’. Photograph by Tim Flohr Sørensen.

8

Tim Flohr Sørensen

the past by a similar animism and what the

ethical implications of such cases might be.

Likewise, the complex entanglement of peo-

ple and things may assume concrete form in

corporeal integrations of humans and non-

humans, where things can become integral to

personhood or extensions of a human. We

may refer to the rather trivial example of the

wedding ring that is oftentimes considered so

important a part of a person that s/he is buried

with it or it assumes the role of an heirloom

with an immanent power. However, the point

is not simply that things can have power or

constitute parts of people. In the light of the

issues raised with Harrison above, the crucial

challenge for archaeology is to be able to cope

with the fact that human

–non-human rela-

tions may oscillate and change character

over time. This is not only a question of deter-

mining what archaeologists should regard as

human and non-human, but also of recogniz-

ing the changing identities of the human body

in history (e.g. Butler 1993, Gil 1998, van

Dijck 2005, Robb and Harris forthcoming).

Moving on from the wedding ring, we may

consider whether personalized items, such as

adornment in the form of piercings, tattoos,

scars and implants, form part of the human

body, and whether they should, as a conse-

quence, be granted the same ethical status as

the rest of the human body. We may hypothe-

tically distinguish between attributes that have

been inscribed, engraved or implanted on the

body as opposed to those that may be

detached and re-attached as separate objects.

Consider, for example, the tattoos on the skin

of the so-called Ice Man from the Alps

(e.g. Sjøvold et al. 1995). The tattoos are inte-

grated into the skin of the person, and, despite

having been applied artificially, they do not

seem to be regarded as an alienable part of the

Ice Man. Unlike his tools and clothes, the

tattoos are not separable from his body, but

can he be understood without either of them?

On display in the South Tyrol Museum of

Archaeology in Bolzano, museum curators

have not carved the tattoos from his skin,

and probably would never consider doing so,

but his axe, bow and other equipment are not

displayed as equally integral to his bodiness.

In many archaeological cases it is, indeed,

extremely difficult to recognize when a non-

congenital or inorganic application is to be

understood as something the person consid-

ered to be an essential part of her- or himself.

Marie Louise Stig Sørensen (1995, p. 102)

observes how female dress in the North

German Bronze Age is characterized by

being fixed to certain positions on the body,

by often being attached permanently to the

body and by being highly visible. While all

kinds of attire can be seen as extensions of

the body, inseparable objects

– objects that

are forged onto the body

– draw the attention

to a special construction of bodiness and iden-

tity. The status of these irremovable artefacts

as part of the person

’s ontology or identity is a

matter of cultural definitions, but we may at

least stipulate that a bracelet that cannot be

removed from the arm and which is highly

visible

– and thereby socially pronounced –

does not simply represent a personal construc-

tion of identity for the wearer. The bracelet

can be integrated into the social perception of

the individual

’s body or may even have been

imposed on the body by social norms, creating

and presencing (as opposed to merely repre-

senting) her identity or sense of self (Sørensen

1995, p. 108).

This problem about the limits of bodiness

also finds exemplification in the story about

Lasse and the foot that was amputated.

Ethically speaking, Lasse

’s foot was consid-

ered and treated as a legitimate part of Lasse

– by himself, his family and his community –

regardless of whether it was attached to the

rest of his body or not; it had historically been

part of him, which is why it still constituted a

part of Lasse even when it had been severed.

So, if Lasse

’s severed foot cannot simply be

seen as ontologically alien or

‘other’ from the

whole, integrated body, what about his new

artificial limb? This insistence on an ontologi-

cal persistence in the relationship between the

part and the whole of a person breaks down

the barrier ordinarily maintained between

We Have Never Been Latourian

9

what is to be granted the status of body

proper, of body part or of

‘artificial’ extension

of the body.

A recent study comparing the experience

of

osseointegrated

prostheses

(prostheses

implanted into the users

’ bone) and prostheses

suspended with sockets showed that the

integration of the prosthesis into the bone

facilitated the experience of the prosthesis

’

incorporation into the body proper (Lundberg

et al. 2011). It should be mentioning, however,

that an anthropological dissertation on people

with socketed prostheses has testified that

people can likewise experience the detach-

able prosthesis as a part of the body, stating

that the prosthesis

‘is also me’ (Østergaard

2006).

Taking this line of thinking a step further,

Vivian Sobchack (2005, 2010) has accounted

for the sequence of events between losing her

leg to cancer and getting an artificial leg. She

describes the process of changes from being

used to walking on two legs, to having her leg

amputated and having to walk on crutches

–

which she describes as having three legs

– and

occasionally hobbling around on her one

remaining healthy leg. This is what she terms

a

‘choreography for one, two and three legs’,

having to learn and identify with an altered

bodiness and sensation of self. She explains

how the number of legs she was equipped

with at any given time had to be the basis for

how she defined herself and her bodily being.

The presence of two legs, the absence of a leg

or the temporary equipment with three

‘legs’

or even a trolley in the supermarket framed

her understanding of herself, regardless of

what was human tissue and what was techni-

cally

‘artificial’ or a ‘tool’. The supermarket

trolley or the crutches thus approximate

humanness in the same way as an artificial

limb, and Sobchack maintains that they are

‘literally – if incompletely – incorporated’

(2005, p. 57) into the ensemble constituting

the lived body, being

‘the ground of our inten-

tional movement acts, not the figure

’ (ibid).

Sobchack points to the fact that the integra-

tion of a tool or prosthesis into the perceptual

continuity of the whole body depends on

motor skills and the capacity to exercise the

‘one, two and three legged choreography’; the

integration works best the more the prosthesis

disappears into the perceptual background,

where one becomes less aware of its presence,

echoing Drew Leder

’s (1990) notion of the

‘absent body’. This illustrates that the rela-

tionship between human and non-human

does not need to be seen as a clear-cut dichot-

omy or as a stable or permanent continuity,

but can also unfold as sliding positions in a

spectrum of changeable possibilities. In all of

these cases, the margins of body and non-body

are compromised. It may be argued from a

modernist point of view, however, that this is

merely a perceptual, phenomenological or

subjective experience of bodiness and being,

whereas ethical concerns apply only to those

aspects of the body that can be recognized as

distinctly human and can be shared more

objectively as such.

However, the boundaries of the human

organism and the entire notion of the

‘body’

are in many instances breached, which has

consequences for how we relate to and situate

being human (Haraway 1991, Hayles 1999).

In an immediate and practical context, dispo-

sal practices highlight precisely the temporary

and unfixed character of body and bodiness

(see, e.g., papers in Rebay-Salisbury et al.

2010, Kuijt et al. forthcoming). Cremation is

one aspect of such bodily transience, where the

notion of and attitude to the human body in

contemporary Western societies as well as his-

torically can be seen as suspended between

integrity and fragmentation (Sørensen and

Rebay 2008, Sørensen

and Bille 2008,

Sørensen 2009). In the current West, crema-

tion transforms the body to

‘ashes’, perceived

as a new integrity of the body, yet this sub-

stance is most often composed of a fusion of

the human body, its dress and a casket. This is

not merely a condition of cremation in mod-

ern times, where technology and humanity

melt together; archaeological examples of cre-

mation also display a similar production of a

blended human-thing relationship. It may be

10

Tim Flohr Sørensen

illustrated at the Early Bronze Age locale of

Damsgård in north-western Denmark (Olsen

and Bech 1994), where a cremation site was

found beneath a burial mound. A woman had

been burnt in a shallow pyre-pit and the

remains of the cremation were then deposited

in an adjacent stone cist. The stone cist con-

tained a fragment of an arm bone, which had

merged partially with a bronze arm ring dur-

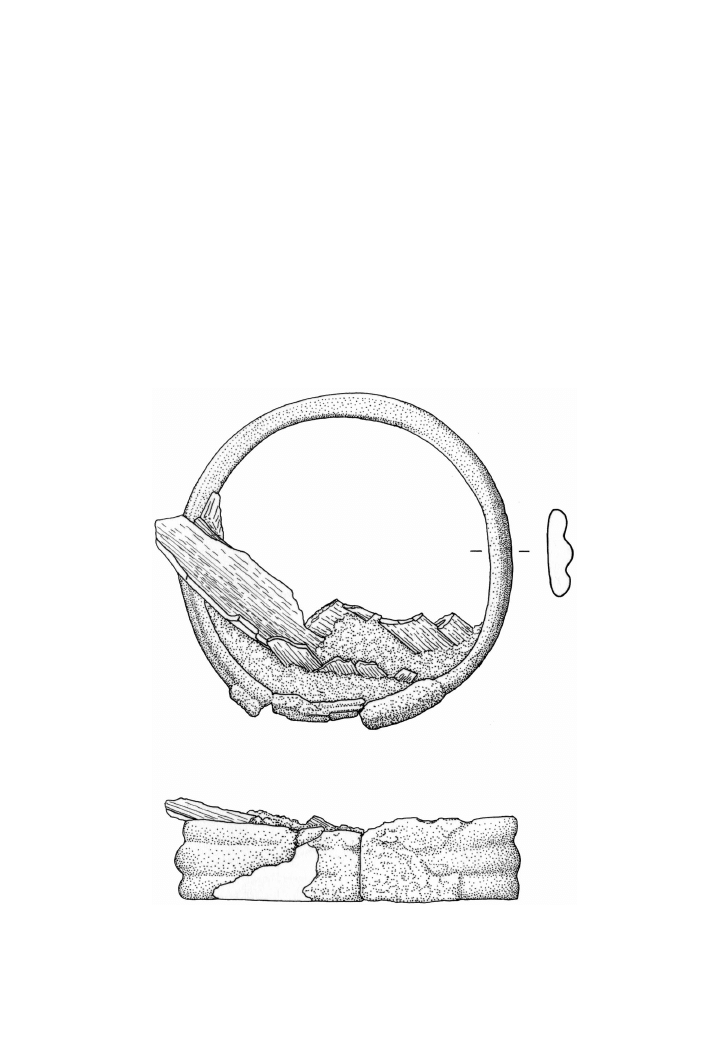

ing the cremation (Fig. 3), suggesting that the

people responsible for the disposal of the dead

person chose not to distinguish between

human and non-human matter after the

cremation, and that they were not primarily

concerned with the coherence of the body as a

purely

human

body

upon

being burnt

(Sørensen forthcoming).

There are, in other words, no purely human

remains upon cremation, and, after being

burnt, the human and non-human elements

are in many cases indistinguishable.

‘Ashes’

are a conglomerate of the partially or entirely

burnt human body, its organic and inorganic

dress, and the container in which (or the pyre

on which) the body was cremated. The ashes

are

– in all aspects of the term – posthuman.

Fig. 3. Bronze arm ring and fragment of human bone, Damsgård, northwestern Jutland, Denmark. After

Aner and Kersten (2001). Printed with permission from Nationalmuseet Copenhagen.

We Have Never Been Latourian

11

DISIDENTIFICATION

Altogether, these examples offer a spectacle

for thinking critically through the limits of

the human and the associated range of ethical

implications. A number of the issues described

above already have consequences for how

archaeology diagnoses and represents past

remains, while their ethical dimensions rarely

breach the confines of the human

–non-human

divide that Latour identifies in modernity, and

ethics hence sits comfortably within the mar-

gins of what is considered human. The over-

laps of people and things outlined above,

however, involve imbrications that make a

separation impossible, such as in the case of

tattoos or cremation. Taking these examples

seriously as modes of thinking about a poten-

tial posthuman ethics triggers a number of

challenges to archaeology with consequences

for cases that are less immediately recogniz-

able as ethically charged.

So, how should archaeologists relate ethi-

cally to a prehistoric scenario, encountering

bodies with things or even the absence of

bodies but the presence of things? If the

human body is to be considered with refer-

ence to ethical claims, what about its non-

congenital or non-human traits? If body

parts and prostheses, adornments and perso-

nal belongings can be members of the

human body, what about other objects that

have less intimate, integrated or personal

character

– where is the dividing line and

how do we make the judgement? If these

questions have any import it implies that

we can assume no straightforward justifica-

tion in identifying more immediately with

people than things. Within the flat ontology

of posthumanism, people and things operate

at the same ontological level, and for

archaeology this should of course also

include taking past conceptions of the char-

acter of the human or non-human Other

into account.

But such as critique also exposes a series of

contradictory practices in current archaeology

and heritage practice: while the archaeological

modernist attitude seems content to reject a

symmetrical principle, heritage management

happily elevates (some) non-humans to the

state of proper

‘beings’. Based on archaeol-

ogy

’s modernist disposition, it is not difficult

to understand why the discipline has trouble

embracing the relationship between humans

and non-humans as a mess, but why are non-

humans sometimes fetishized as entities of

timeless and universal value? And why are

only some non-humans treated in this way?

Heritage practice in effect suggests that the

ethical imperative to protect and conserve is

not only a matter of intellectual attitudes to

objects and places of cultural and educational

value, but equally shrouded in less explicit

mechanisms.

In a radical argument, Brit Solli (2011) con-

tends that certain objects of heritage can

‘defend themselves’ and constitute ‘an essen-

tial heritage

’ by way of their age, anomaly and

beauty (2011, pp. 46

–47). This is an argument

for a

‘mitigated essentialism’ (2011, p. 47): the

universal recognition of certain material qua-

lities that are claimed to be so pervasive and

make it

‘self-evident for everyone that this is a

treasure to be cherished

’. When Solli identifies

heritage items that can defend themselves and

make themselves heard, it indicates that the

thing speaks to us, that it touches us. This

seems to suggest that the past can be not only

so close, affectively, that we can almost touch

it, but also so impressive or pressing that we

are automatically touched by it (see also

Wingfield 2010). It is precisely this affective

quality that situates some objects of heritage

very close to the fetish, and, while there is

nothing wrong with the fetish, it does result

in inherently inconsistent ethical obligations

towards non-humans. For something to be

understood as fetish, it hinges on a human

‘believer’ acknowledging the object as

endowed with a spirit or an agency, being

animated and animating. Heritage objects, in

other words, depend on a human subject

situated in cultural or perceptual proximity

in order to identify with and respond to

its agent-like qualities.

‘Age’, ‘anomaly’,

12

Tim Flohr Sørensen

‘beauty’, ‘treasure’: terms whose essence and

meaning, and not least political use and

fetishisation, relentlessly shift and remain con-

tingent on their historical and cultural con-

text. So if things are not identified as old,

special, pretty or precious, where are they

situated in the heritage hierarchy? Can we

hear them at all?

Two points of critique furthermore emerge

as a consequence of heritage fetishism: if the

thing can

‘defend itself’, does it really need

human representation? And is the immediate

identification

with

affectively

powerful

objects not a call to attend even more care-

fully to the

‘missing masses’ and the ‘faceless

minions

’ at the expense of ‘heritage celebri-

ties

’? These questions suggest the need for

moving closer to and, at the same time,

further away from the archaeological Other

and the heritage object, depending on one

’s

given subjective position. Through an analy-

tical exercise of disidentification it thus

becomes possible to share without erasing

differences (Medina 2003), which allows the

archaeological practice and heritage work to

appreciate situations and contexts where

human

and

immediately

recognizable

human qualities are decentred. Sharing, in

this connection, is about diagnosing continu-

ities between humans and non-humans, while

at the same time being susceptible to histori-

cally and culturally contingent contexts and

their heterogeneity. This means that the con-

ventional archaeological practice of interpre-

tation needs to be placed at the foreground of

this ethical task, because it seeks to under-

stand how people, things, subjects, objects,

abjects, nature, society and what have you,

might have been situated in the past. Hence,

a symmetrical principle or flat ontology

should not be claimed as a universal condi-

tion or constitute an a priori directive for our

understanding of past Others, as it forecloses

the archaeological importance of trying to

understand how human-thing relationships

and ontologies might have looked in the

past. Accordingly, we may need to become

more familiar with the alien Other, and more

distant from the familiar, which compels us

to be able to address, approach and

empathize with the Other without being

able to identify with her or him (see also

Graves-Brown 2011).

CONCLUSIONS AND CONSEQUENCES

While the title of this article speaks in the voice

of the deniers of a confusion of humans and

non-humans, it also seeks to situate a

Latourian approach to things and people

(and parts of people) within an ethical discus-

sion of the practice of archaeology

– whether

conventional or

‘symmetrical’ – and the field

of cultural heritage. The article has argued

that archaeological ethics are located on

dynamic

and

sliding

scales,

oscillating

between the deeply reflective and the casually

intuitive, and that any discussion of ethics is

not (and should not be) characterized by con-

sensus (Tarlow 2006, p. 199). The aim has

been to move beyond the prevailing discussion

of ethical practice that dominates the archae-

ological debate, centred on the handling of

human remains (e.g. Scarre 2006, Kaufmann

and Rühli 2010), looting and the trading of

cultural property (e.g. Hamilakis 2003) or the

potential conflict between archaeologists and

indigenous people and their descendants

(e.g. Watkins 2003). The objective of the arti-

cle has instead been to address the ethical

implications of the de facto sliding scales of

humans and non-humans in the light of the

recent onset of Latour-inspired symmetrical

agendas in archaeology. The aim has been, in

other words, not to evaluate the legitimacy of

a Latourian anthropology or a symmetrical

archaeology, but to explore their conse-

quences for the ethical dimensions of archae-

ology and heritage practice.

Without disarming my argument entirely,

I do want to flag a disclaimer, underlining

that certain aspects of this article have been

more polemic than others. I personally do not

think that the conflation of subject and object

in a Latourian sense is unproblematic and I do

believe that there are very good reasons to give

We Have Never Been Latourian

13

humans primacy over non-humans in terms of

ethics

– also when it compromises so-called

‘cultural heritage’. I would like to suggest,

nevertheless, that any polemic offers the

potential to question ready-made normativity,

and in this case I believe that the common-

sense, unqualified rejection of the ethical

claims of non-humans should be challenged.

It should be made clear that I am not trying

to argue that all artefacts and occurrences

from the past, or the present, should be treated

with the same ethical claim as living or

recently deceased human beings. I am, rather,

trying to question where we draw the line

between those phenomena that are treated as

if they can be subject to ethical claims and

those that cannot. The issue has been

addressed at several levels: whether non-

bodily non-humans should be included in

ethical scrutiny and if they should be given

rights similar to those of human beings,

whether there is any justification for singling

out

spectacular

monuments

as

more

important than fragments of anonymous,

mass-produced,

mundane

objects,

and

whether there is any ethical legitimacy in

defining human remains as empathically clo-

ser to the researcher than non-human objects.

If Harrison (2012, pp. 217

–220) is correct in

characterizing the ethics of heritage as contin-

gent, this also indicates that we have a respon-

sibility for being susceptible to the possibility

of decay and disappearance as positive quali-

ties of an object, place or practice. Some qua-

lities of human

–non-human relations are

precisely temporal and may not be captured

best by sustainability (in the sense of durabil-

ity). If heritage is not simply a set of tangible

relics or intangible expressions and practices,

but something constituted as relational and

emergent (Harrison 2012, p. 226), then one

of its primary qualities may be its capacity

for deterioration. In the end, we may, hence,

raise the question if of whether a Latourian

attitude to archaeology and heritage should

pay more attention not only to the symmetry

Fig. 4. Lille Bamse. Animated for some; an alienable thing for others; himself seemingly untroubled by the

posthuman condition. Photograph by Tim Flohr Sørensen.

14

Tim Flohr Sørensen

of humans and non-humans, nature and

society, but also to the emergence and dissolu-

tion of relations, in effect allowing things of

the past not to be conserved (see also Holtorf

2005a, 2005b).

If we are to take the symmetrical proposi-

tion seriously or at least some of the agenda

’s

posthuman element, it involves at least two

propositions: first, we need to re-evaluate not

only notions of human and non-human, but

also the capability to identify varieties of inter-

mediary and fluctuating beings in the archae-

ological record, and, second, there is a need to

recognize the symmetry between non-humans

in various forms of being and their temporal

properties. In the end, the question emerges: is

there any legitimacy in maintaining the non-

human object simply as an

‘object’, denied of

its right to be treated under the banner of

ethical standards, if it was treated and concep-

tualized in prehistory as

‘alive’, having had

‘personhood’ or was an inseparable part of a

prehistoric human being? Such an object is, of

course, part of the pre-modern (or a-modern)

mindset that Latour identifies, which in his

view has never fully been replaced or revolu-

tionized by modernity. So, we have always

been fetishizing, animating and conflating

the perspectives of humans and non-humans,

even though many (or most?) archaeologists

and curators today might argue that at least

they have never been Latourian.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The main body of this article was written when

I enjoyed a Marie Curie research fellowship at

the University of Cambridge on the Forging

Identities project, funded by EC Framework

7. Basic ideas in the article were presented at a

Forging Identities workshop on ethics and

politics in 2010, and discussion with the parti-

cipating PhD students stimulated me to move

on with the manuscript. A number of indivi-

duals have contributed significantly in the

advanced

work

with

this

article:

Ben

Davenport, Marie Louise Stig Sørensen,

Juliane Wammen, and in particular Dacia

Viejo-Rose and Mikkel Bille. Moreover, I

am very grateful for highly valuable com-

ments and critique provided by two peer

reviewers, Rodney Harrison and an anon-

ymous referee. All mistakes remain my own.

REFERENCES

Aner, E. and Kersten, K., 2001. Die Funde der älteren

Bronzezeit des nordischen Kreises in Dänemark,

Schleswig-Holstein und Niedersachsen, Band 11,

Thisted Amt. Neumünster: Karl Wachholtz Verlag.

Badmington, N., ed., 2000. Posthumanism. Basin-

gstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Barad, K. 1998. Getting real: technoscientific prac-

tices

and

the

materialization

of

reality.

Differences, 10(2), 87

–128.

Bille, M., 2012. Assembling heritage: investigating

the UNESCO proclamation of Bedouin intangi-

ble heritage in Jordan. International Journal of

Heritage Studies, 18(2), 107

–123.

Bryant, L.R., Srnicek, N. and Harman, G., eds,

2011. The speculative turn: continental material-

ism and realism. Melbourne: re.press.

Butler, J., 1993. Bodies that matter: on the discursive

limits of

‘sex’. London: Routledge.

Cleere, H., 1996. The concept of

‘outstanding uni-

versal value

’ in the World Heritage Convention.

Conservation and Management of Archaeological

Sites, 1(4), 227

–233.

Dant,

T.,

2005.

Materiality

and

society.

Maidenhead and New York: McGraw Hill/

Open University Press.

Dawney, L.A., Harris, O.J.T. and Sørensen, T.F. in

prep. Being materially-affective: the place of the

human after post-humanism. Manuscript under

review.

Domanska, E., 2006. The return to things.

Archeologia Polona, 44, 171

–185.

Francioni, F. and Lenzerini, F., 2003. The destruc-

tion of the Buddhas of Bamiyan and interna-

tional law. European Journal of International

Law, 14(4), 619

–651.

Furtado, P., 2006. Heritage is good for you. History

Today, 54(9), 2.

Gil, J., 1998. Metamorphoses of the body.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Graves-Brown, P. 2011. Touching from a distance:

alienation, abjection, estrangement and archae-

ology. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 44(2),

131

–44.

We Have Never Been Latourian

15

Hamilakis, Y., 2003. Iraq, stewardship and

‘the

record

’: an ethical crisis for archaeology. Public

Archaeology, 3(2), 104

–111.

Haraway, D.J., 1985. A cyborg manifesto: science,

technology, and socialist-feminism in the late

twentieth century. Socialist Review, 15(2), 65

–108.

Haraway, D.J., 1991. Simians, cyborgs, and women:

the

reinvention

of

nature.

London:

Free

Association Books.

Harman, G., 2009. Prince of networks: Bruno Latour

and metaphysics. Melbourne: re.press.

Harrison, R., 2009. What is heritage? In: R. Harrison,

ed.

Understanding

the

politics

of

heritage.

Manchester: Manchester University Press, 5

–42.

Harrison, R., 2012. Heritage: critical approaches.

London: Routledge.

Hayles, K. N., 1999. How we became posthuman.

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hodder, I., 2012. Entangled: an archaeology of the

relationships between humans and things. Chiches-

ter: Wiley.

Holbraad, M., 2007. The power of powder: mul-

tiplicity and motion in the divinatory cosmol-

ogy of Cuban Ifa (or mana, again). In: A.

Henare, M. Holbraad and S. Wastell, eds.

Thinking through things: theorising artefacts

ethnographically. London: Routledge, 189

–

225.

Holtorf, C., 2005a. Can less be more? Heritage in the

age of terrorism. Public Archaeology, 5(2), 101

–109.

Holtorf, C., 2005b. Iconoclasm: the destruction and

the loss of heritage reconsidered. In: G. Coulter-

Smith and M. Owen, eds. Art in the age of terror-

ism. London: Paul Holberton, 228

–239.

Hornborg, A., 2006. Animism, fetishism, and

objectivism as strategies for knowing (or not

knowing) the world. Ethnos, 71(1), 21

–32.

Jokilehto, J., 2006. World heritage: defining the

outstanding universal value. City & Time, 2 (2).

Available from: http://www.ceci-br.org/novo/

revista/rst/viewarticle.php?id=45 [Accessed 12

April 2012].

Kaufmann, I.M. and Rühli, F.J., 2010. Without

‘informed consent’? Ethics and ancient mummy

research. Journal of Medical Ethics, 36(10),

608

–613.

Kuijt, I., Quinn, C. and Cooney, G., eds., forth-

coming. Fire and the body: cremation as a context

for social meaning. Tucson: University of

Arizona Press.

Latour, B., 1992. Where are the missing masses?

The sociology of a few mundane artifacts. In:

W. E. Bijker and J. Law, eds. Shaping technol-

ogy/building society. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press, 225

–258.

Latour, B., 1993. We have never been modern. New

York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Latour, B., 1999. Pandora

’s hope: an essay on the

reality of science studies. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Latour, B., 2004. Politics of nature: how to bring the

sciences

into

democracy.

Cambridge,

MA:

Harvard University Press.

Latour, B., 2005. Reassembling the social: an intro-

duction to actor-network theory. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Leder, D., 1990. The absent body. Chicago. IL:

Chicago University Press.

Lucas, G., 2012. Understanding the archaeological

record.

Cambridge:

Cambridge

University

Press.

Lundberg, M., Hagberg, K. and Bullington, J.,

2011. My prosthesis as a part of me: a qualitative

analysis of living with an osseointegrated prosthe-

tic limb. Prosthetics and Orthotics International,

35(2), 207

–214.

Medina, J., 2003. Identity trouble: disidentification

and the problem of difference. Philosophy and

Social Criticism, 29(6), 655

–680.

Meskell, L., 2010. Human Rights and Heritage

ethics. Anthropological Quarterly, 83(4), 839

–859.

Morphy, H., 2010. Afterword: museum material-

ities: objects, engagements, interpretations. In: S.

Dudley, ed. Museum materialities: objects,

engagements,

interpretations.

London:

Routledge, 275

–285.

Normark, J., 2010. Involutions of materiality:

operationalizing a neo-materialist perspective

through the causeways at Ichmul and Yo

’okop.

Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory,

17(2).

Olsen, A.-L. H. and Bech, J.-H., 1994. Damsgård:

en overpløjet høj fra ældre bronzealder per. III

med stenkiste og ligbrændingsgrube. Kuml,

1993

–1994, 155–198.

Olsen, B., 2003. Material culture after text:

re-membering things. Norwegian Archaeological

Review, 36(2), 87

–104.

Olsen, B., 2006. Ting-mennesker-samfunn: intro-

duksjon

til

en

symmestrisk

arkeologi.

Arkæologisk Forum, 14, 13

–18.

Olsen, B., 2007. Keeping things at arm

’s length: a

genealogy of asymmetry. World Archaeology,

39(4), 579

–588.

16

Tim Flohr Sørensen

Olsen, B., 2010. In defense of things: archaeology

and the ontology of objects. Lanham, MD:

Altamira Press.

Olsen, B., 2012. Symmetrical archaeology. In: I.

Hodder, ed. Archaeological theory today. 2nd

edn. Cambridge: Polity Press, 208

–228.

Olsen, B. et al., 2012. Archaeology: the discipline

of things. Berkeley: University of California

Press.

Omland, A., 2006. The ethics of the World Heritage

concept. In: C. Scarre and G. Scarre, eds. The

ethics of archaeology: philosophical perspectives

on

archaeological

practice.

Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 242

–259.

Pedersen, M.A., 2001. Totemism, animism and

North Asian indigenous ontologies. The Journal

of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 7(3),

411

–427.

Pels, P., 1998. The spirit of matter:. on fetish, rarity,

fact, and fancy. In: P. Spyer, ed. Border fetish-

isms: material objects in unstable spaces. London:

Routledge, 91

–121.

Pels, P., 2010. Magical things: on fetishes, com-

modities, and computers. In: D. Hicks and

M.C. Beaudry, eds. Oxford handbook of material

culture studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

613

–633.

Pietz, W., 1985. The problem of the fetish I.

RES: Journal of Anthropology and Aesthetics,

9, 5

–17.

Pietz, W., 1987. The problem of the fetish II: the

origin of the fetish. RES: Journal of Anthropology

and Aesthetics, 13, 23

–45.

Pietz, W., 1988. The problem of the fetish III:

Bosman

’s Guinea and the Enlightenment theory

of fetishism. RES: Journal of Anthropology and

Aesthetics, 16, 105

–123.

Pyyhtinen, O. and Tamminen, S., 2011. We have

never been only human: Foucault and Latour on

the question of the anthropos. Anthropological

Theory, 11(2), 135

–152.

Raj Isar, Y., 2011. UNESCO and heritage: global

doctrine, global practice. In: D. Viejo-Rose, ed.

Heritage, memory and identity. London: Sage,

39

–52.

Rebay-Salisbury, K., Sørensen, M.L.S. and Hughes,

J., eds., 2010. Body parts and wholes: changing

relations and meanings. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Robb, J. and Harris, O.J.T., eds., forthcoming. The

body in history: Europe from the Paleolithic to the

future. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scarre, G., 2006. Can archaeology harm the dead?

In: C. Scarre and G. Scarre, eds. The ethics of

archaeology:

philosophical

perspectives

on

archaeological practice. Cambridge: Cambridge

Univsersity Press, 181

–198.

Shanks, M., 2007. Symmetrical archaeology.

World Archaeology, 39(4), 589

–596.

Sjøvold, T. et al., 1995. Verteilung und Größe der

Tätowierungen am Eismann vom Hauslabjoch.

In: K. Spindler et al., eds. Der Mann im Eis, Vol.

2, Neue Funde und Ergebnisse. Wien: Springer,

279

–286.

Skovsbøl, U., 2010. Lasses afsked med sin fod.

Kristeligt Dagblad, 5 March.

Smith, L., 2006. Uses of heritage. New York:

Routledge.

Sobchack, V., 2005. Choreography for one, two

and three legs (a phenomenological meditation

in movements). Topoi, 24, 55

–66.

Sobchack, V., 2010. Living a

‘phantom limb’: on

the phenomenology of bodily integrity. Body &

Society, 16(3), 51

–67.

Solli, B., 2011. Some reflections on heritage and

archaeology in the Anthropocene. Norwegian

Archaeological Review, 44(1), 40

–54.

Sørensen, M.L.S., 1995. Reading dress: the con-

struction of social categories and identities in

Bronze Age Europe. Journal of European

Archaeology, 5, 93

–114.

Sørensen, M.L.S. and Rebay, K.C., 2008. From

substantial bodies to the substance of bodies:

analysis of the transition from inhumation to

cremation during the Middle Bronze Age in

Europe. In: J. Robb and D. Boric´, eds. Past

bodies: body-centered research in archaeology.

Oxford: Oxbow Books, 59

–68.

Sørensen, T.F., 2009. The presence of the dead:

cemeteries, cremation and the staging of non-

place. Journal of Social Archaeology, 9(1),

110

–135.

Sørensen, T.F., forthcoming. Re/turn: cremation,

movement and re-collection in the Early Bronze

Age of Denmark. In: I. Kuijt, C. Quinn and G.

Cooney, eds. Fire and the body: cremation as a

context for social meaning. Tucson: University of

Arizona Press.

Sørensen, T.F. and Bille, M., 2008. Flames of trans-

formation: the role of fire in cremation practices.

World Archaeology, 40(2), 253

–267.

Spyer, P., ed., 1998. Border fetishisms: material

objects in unstable spaces. London: Routledge.

We Have Never Been Latourian

17

Tarlow, S., 2006. Archaeological ethics and the

people of the past. In: C. Scarre and G. Scarre,

eds. The ethics of archaeology: philosophical per-

spectives on archaeological practice. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 199

–216.

Thomas, J., 2004. Archaeology and modernity.

London: Routledge.

van der Tuin, I. and Dolphijn, R., 2010. The trans-

versality of new materialism. Women: A Cultural

Review, 21(2), 153

–171.

van Dijck, J., 2005. The transparent body: a cultural

analysis of medical imaging. Seattle: University

of Washington Press.

Verbeek, P.-P., 2005. What things do: philosophical

reflections on technology, agency, and design.

Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania University Press.

Verbeek, P.-P., 2006. Materializing morality: design

ethics and technological mediation. Science

Technology Human Values, 31(3), 361

–380.

Verbeek, P.-P., 2011. Moralizing technology: under-

standing and designing the morality of things.

Chicago. IL: University of Chicago Press.

Viveiros de Castro, E., 1998. Cosmological deixis

and Amerindian perspectivism. The Journal of

the Royal Anthropological Institute, 4(3), 469

–488.

Viveiros de Castro, E., 2004. Exchanging perspec-

tives: the transformation of objects into subjects

in Amerindian ontologies. Common Knowledge,

10(3), 463

–484.

Waterton, E. and Smith, L., 2009. There is no such

thing as heritage. In: E. Waterton and L. Smith,

eds.

Taking

archaeology

out

of

heritage.

Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars

Publishing, 10

–27.

Watkins, J., 2003. Archaeological ethics and

American Indians. In: L.J. Zimmerman, K.D.

Vitelli and J. Hollowell-Zimmer, eds. Ethical

issues in archaeology. Walnut Creek, CA:

AltaMira Press, 129

–141.

Webmoor, T., 2007. What about

‘one more turn

after the social

’ in archaeological reasoning?

Taking things seriously. World Archaeology,

39(4), 546

–562.

Webmoor, T., 2012. An archaeological metaphy-

sics of care: on heritage ecologies, epistemogra-

phy and the isotopy of the past(s). In: B.

Fortenberry and L. McAtackney, eds. Modern

materials: the proceedings of CHAT Oxford,

2009. Oxford: Archaeopress, 13

–23.

Webmoor, T. and Witmore, C.L., 2008. Things are

us! A commentary on human/things relations

under the banner of a

‘social archaeology’.

Norwegian Archaeological Review, 41(1), 1

–18.

Willerslev, R., 2007. Soul hunters: hunting, animism

and personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wingfield, C., 2010. Touching the Buddha: encoun-

ters with a charismatic object. In: S. Dudley, ed.

Museum materialities: objects, engagements,

interpretations. London: Routledge, 53

–70.

Witmore, C.L., 2006. Vision, media, noise and the

percolation of time: symmetrical approaches to

the mediation of the material world. Journal of

Material Culture, 11(3), 267

–292.

Witmore, C.L., 2007. Symmetrical archaeology:

excerpts of a manifesto. World Archaeology,

39(4), 546

–562.

Østergaard, E.B., 2006. Protesen er også mig: en

antropologisk undersøgelse af, hvordan mennes-

ker, der har fået amputeret en del af et ben,

oplever at føle sig hele, at benprotesen inkorpor-

eres og at blive reintegreret i samfundet.

Unpublished Master

’s dissertation. Copenhagen:

University of Copenhagen.

18

Tim Flohr Sørensen

Copyright of Norwegian Archaeological Review is the property of Routledge and its content

may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright

holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for

individual use.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Język angielski Write a story ending with the wordsI have never see him agai

Do we have a good reason to?lieve in existence of a higher

Zizek Are we in a war Do we have an enemy

We have an environmental crisis?cause we have a people cris

We have the widest range of equipment and products worldwide

Do We Have Souls

plany, We have done comprehensive research to gauge whether there is demand for a new football stadi

Anderson, Poul We Have Fed Our Sea

TRUE PRIMES We Have Won CDEP (Locust Music) LST086lst086

Atlantis We Will Never Know doc

Anderson, Poul We Have Fed Our Sea

Suzette Haden Elgin We Have Always Spoken Panglish

Elgin, Suzette Haden We Have Always Spoken Panglish

Americans Think We Have the World’s Best Colleges We Don’t Kevin Carey

Have Never Desired Your Good Opinion

więcej podobnych podstron