Notes on Templar personnel and government at the turn

of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries

Alan Forey

The Bell House, Church Lane, Kirtlington, Oxon, OX5 3HJ, UK

Keywords:

Templars

Hospitallers

Recruitment

Provincial and central administration

Sergeants

a b s t r a c t

The Hospital of St John is thought to have been in various respects

in a rather more healthy condition than the order of the Temple in

the late thirteenth century, and comparisons and contrasts

between the two orders have recently been made, often to the

detriment of the Templars. This view is examined with reference to

recruiting, the role of sergeants, ignorance among brothers,

provincial administration, central government, and roles after the

collapse of the crusader states. The argument is advanced that the

Temple was not in a noticeably worse state than the Hospital and

that on many issues the similarities between the two orders are

more marked than the differences.

Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

In recent years the Templars have been having a bad press. Not only have several writers maintained

that during admission ceremonies recruits to the order denied Christ, spat on the cross and engaged in

indecent kissing;

there have also been claims that at the end of the thirteenth century the Templars

had difficulty in recruiting, were often ignorant, and, in Riley-Smith’s words, possessed ‘an anarchic

and archaic system of management’. He also writes that ‘the state of the order seems to have been so

E-mail address:

1

B. Frale, L’ultima battaglia dei Templari: dal codice ombre d’obbedienza militare alla costruzione del processo per eresia (Rome,

2001); B. Frale, ‘The Chinon chart. Papal absolution to the last Templar master Jacques de Molay’, Journal of Medieval History, 30

(2004), 109–34; A. Demurger, Chevaliers du Christ. Les Ordres religieux-militaires au moyen a

ˆge, XIe–XVIe sie`cle (Paris, 2002), 223;

A. Demurger, Les Templiers. Une chevalerie chre´tienne au moyen a

ˆge (Paris, 2005), 484–94; A. de la Croix, L’Ordre du Temple et le

reniement du Christ (Paris, 2004); J. Riley-Smith, ‘Were the Templars guilty?’, in: The medieval crusade, ed. S.J. Ridyard

(Woodbridge, 2004), 107–24; E. Lord, The Templar’s curse (Harlow, 2008), 136.

Contents lists available at

Journal of Medieval History

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e /

0304-4181/$ – see front matter Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jmedhist.2009.03.002

Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

dire that one wonders how long it could have been allowed to remain in existence.

Slowness of

communications inevitably made effective central control difficult in any international order, but the

Hospital is thought to have been in various respects in a rather more healthy condition, and

comparisons and contrasts between the two orders have been made, often to the detriment of the

Templars.

Although numerous criticisms could be voiced of the arguments relating to Templar admission

ceremonies, here the focus will be on the personnel and governmental structures of the Temple at the

turn of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and the extent to which the Temple differed from the

Hospital in these matters, although comparisons are inevitably hampered by the differing nature of the

sources surviving for the two institutions. Many of the criticisms which have been expressed about

Templar personnel and government are based on comments made during the Templar trial, and there

is, of course, no material of a comparable kind for the Hospitallers. On the other hand, the central

archives of the Temple have completely disappeared, and there are, for example, no surviving texts of

any statutes issued by Templar general chapters.

Recruitment

It has on several occasions been suggested that the Temple encountered difficulties in recruiting in the

later thirteenth century.

The argument has related in some cases to an apparent lack of postulants

from particular groups. Attention has been drawn to the ages of those who testified during the Templar

trial in some regions, and it has been suggested that the recruitment of young men capable of fighting

had not been maintained.

Most of the Templars questioned in the West were certainly not very young

when interrogated: of those who gave evidence in Paris in 1307, nearly 60 per cent were over 40.

On

this point it is impossible to make any comparison with the Hospitallers in the early fourteenth century,

although in 1373 the average age of Hospitallers in some western priories was greater than that of

Templars at the beginning of the century. The situation in the Hospital in the later fourteenth century

may, however, have been influenced by particular factors, such as plague.

It may be pointed out,

however, that the average age on entry of Templars questioned during the trial was the mid- to late-

twenties.

Little is known about ages on recruitment in earlier periods of Templar history, but the

records of interrogations in Paris in 1309–11,

which provide the most extensive information about

ages, do not suggest a marked change in the years after 1291 (see

Of course, many recruits who had been middle-aged or elderly when they entered the order in the

decades before 1291 would have died before the time of the interrogations: if this is taken into account

the figures of 69 per cent joining before 1291 when below 30 and 59.3 per cent in the order’s last 16

years suggest that recruiting patterns had not changed to any considerable extent, although there had

apparently been more postulants in their teens before 1291. Since nearly 60 per cent of those entering

the Temple after the collapse of the crusader states were below 30 on admission it can scarcely be

2

J. Riley-Smith, ‘The structures of the orders of the Temple and the Hospital in c.1291’, in: The medieval crusade, ed. Ridyard,

127–8, 131, 141, 143; similar comments are made in J. Riley-Smith, ‘ Towards a history of military-religious orders’, in: The

Hospitallers, the Mediterranean and Europe. Festschrift for Anthony Luttrell, ed. K. Borchardt, N. Jaspert and H.J. Nicholson

(Aldershot, 2007), 281, where it is also stated that ‘it is indisputable that the order was in chaos.’

3

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 127–8; M. Miguet, Templiers et Hospitaliers en Normandie (Paris, 1995), 128; E. Gooder, Temple

Balsall. The Warwickshire preceptory of the Templars and their fate (Chichester, 1995), 83–4; R. Studd, ‘From preceptor to prisoner

of the Church: Ralph Tanet of Keele and the last of the Templars’, Staffordshire Studies, 8 (1996), 43.

4

Gooder, Temple Balsall, 83.

5

A.J. Forey, ‘Towards a profile of the Templars in the early fourteenth century’, in: The military orders. Fighting for the faith and

caring for the sick, ed. M. Barber (Aldershot, 1994), 197; see also A. Gilmour-Bryson, ‘Age-related data from the Templar trials’, in:

Aging and the aged in medieval Europe, ed. M.M. Sheehan (Toronto, 1990), 132–3.

6

A.M. Legras, ‘Les Effectifs de l’ordre des Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean de Je´rusalem dans le prieure´ de France en 1373’, Revue

Mabillon, 60 (1984), 362–3, 368–9; L’Enqueˆte pontificale de 1373 sur l’ordre des Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean de Je´rusalem, ed. A.M.

Legras (Paris, 1987), 105.

7

A.J. Forey, ‘Recruitment to the military orders (twelfth to mid-fourteenth centuries)’, Viator, 17 (1986), 150; see also

Gilmour-Bryson, ‘Age-related data’, 134. Age on recruitment was recorded only in some districts.

8

J. Michelet, Proce`s des Templiers, 2 vols (Paris, 1841–51).

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

151

claimed that the order did not have enough men who were of fighting age. It is also clear that at least in

some regions most recruits to the rank of knight in the period after the fall of Acre were still joining at

a young age: of 10 knights who were recruited in Aragon and Catalonia after 1291 and whose age on

recruitment is known, all but one had entered the order when below 20: the average age of these nine

knightly recruits was little more than 15.

Admittedly, not all young recruits were capable of fighting. Many Templar sergeants did not have

a military role, which was the preserve of knights and sergeants-at-arms; and it has further been

maintained that the order no longer appealed sufficiently to the knightly class.

Certainly, it could be

pointed out that by contrast, the Hospital found it necessary in 1292 to impose restrictions on the

admission of knights, except in the Iberian peninsula,

and it has been claimed that towards the end of

the thirteenth century the proportion of sergeants in the Temple was much greater than in the

Hospital.

It is undeniably true that the majority of Templars who were arrested and questioned in the

early fourteenth century were sergeants, although it is not known how many of these were capable of

serving in the field: of the lay brothers who testified before the papal commissioners in Paris between

1309 and 1311 and whose rank is definitely known, 177 were sergeants and only 16 were knights; and

an undated record of testimonies presented in the south of France includes the evidence given by six

knights and 17 sergeants.

Even in the Iberian peninsula, where the Templars still had a military role,

sergeants outnumbered knights: of the brothers questioned in Aragon and Catalonia, 20 were knights

and 46 were sergeants.

The situation was, however, different at the order’s headquarters in Cyprus,

where knights predominated.

Of course, the brothers in Cyprus constituted only a small proportion of

the order’s membership, but it must be remembered that in the East many brothers were killed or

captured when the remnants of the crusader states were being lost and when the island of Ruad fell in

1302, and that most of these brothers were knights.

The life expectancy of sergeants d most of whom

did not serve in the East d at that time must have been greater and this would affect the ratio of

knights and sergeants.

No comparable figures about the proportions of knights and sergeants exist for the Hospital at the

beginning of the fourteenth century. The earliest surviving evidence dates from 1338. Surveys

undertaken in that year show that of the lay Hospitallers in England, Scotland and Wales whose ranks

are known, 31 were knights and 47 sergeants, while in the priory of St Gilles there were 72 knights and

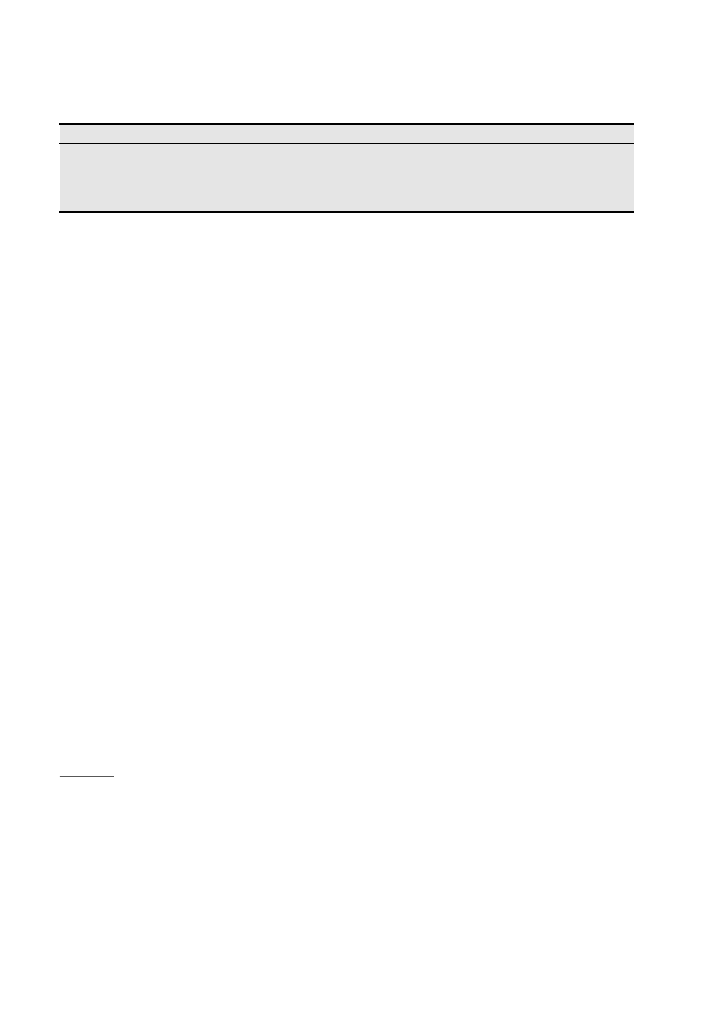

Table 1

Ages on entry of Templars questioned in Paris, 1309–11

Age on entry

Up to 1291

1292–1307

Below 20

21 (25%)

10 (8.6%)

20–29

37 (44%)

71 (50.7%)

30–39

22 (26.2%)

38 (27.1%)

40–49

3 (3.6%)

13 (9.3%)

Over 50

1 (1.2%)

6 (4.3%)

9

These figures are derived from Barcelona, Archivo Capitular, codex 149, and H. Finke, Papsttum und Untergang des

Templerordens, 2 vols (Mu¨nster, 1907), vol. 2, 364–72, doc. 157, although Finke gives Bernard of Puigvert’s age on recruitment as

20, when it was in fact stated to have been 15 (Barcelona, Archivo Capitular, codex 124, f. 20–20v).

10

Miguet, Templiers et Hospitaliers en Normandie, 128; Strudd, ‘From preceptor to prisoner’, 44.

11

J. Delaville Le Roulx, Cartulaire ge´ne´ral de l’ordre des Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean de Je´rusalem, 4 vols (Paris, 1894–1906), vol. 3,

608–9, doc. 4194, art. 2.

12

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 125.

13

Forey, ‘Recruitment’, 144; Michelet, Proce`s, passim; Finke, Papsttum, vol. 2, 342–64, doc. 156.

14

A.J. Forey, The fall of the Templars in the Crown of Aragon (Aldershot, 2001), 76.

15

Forey, ‘Recruitment’, 144.

16

Of eight Aragonese Templars who wrote from an Egyptian prison to James II of Aragon in 1306, all those whose rank is

known were knights: A. Masia´ de Ros, La Corona de Arago

´n y los estados del Norte de Africa (Barcelona, 1951), 299–300, doc. 32.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

152

144 sergeants.

Sergeants were in the majority, but the preponderance of this rank numerically was

then not so marked as in the Temple earlier.

Yet it should be remembered that only a minority of the members of either order was expected to

fight, and that in the years following the collapse of the crusader states the military undertakings of

both Temple and Hospital were limited. In these altered circumstances the Hospital was in 1292

seeking to increase the proportion of non-knightly brothers, who were less costly to maintain and who

could undertake many of the administrative and other tasks which had to be fulfilled in the West. It is

not known whether the Temple was adopting a similar policy: the majority of Templars who were

interrogated had entered the order after 1291, and it is not known whether the ratio of knights to

sergeants had earlier been higher.

That the Temple’s appeal to the knightly classes was declining at

the end of the thirteenth century can only be a supposition.

Clear evidence is also lacking about overall recruitment to the Temple. At times in the early four-

teenth century the Hospital was placing general restrictions on recruiting, suggesting that there was

a sufficient supply of postulants to that order,

but no similar decrees survive for the Templars.

Evidence about length of service given during the proceedings of the trial does not, however, suggest

any marked decline in overall recruitment in the Temple’s later years. The accompanying tables

indicate the proportion of brothers interrogated in various places who were admitted in the 15 years

leading up to the Templars’ arrest (

), and the numbers admitted in each of the last three five-

year periods up to 1307 (

The smallest proportion of recruits from 1293 onwards was among those questioned at Clermont,

but this is the smallest sample, and recruitment in that group was brisk between 1303 and 1307. The

exceptionally high proportion of recent recruits in Cyprus is to be explained by the practice of sending

brothers, especially knights, to the East shortly after their admission in western countries. This custom

obviously affects to some extent the figures for overall recruitment compiled from western sources. All

the Aragonese brothers interrogated in Cyprus, for example, had entered the Temple after the fall of

Acre in 1291.

In order to assess the precise significance of the statistics presented, information would

also be needed about death rates, and this does not exist. Yet as between a fifth and a quarter of those

interrogated in western Europe had joined the order in the five years leading up to the arrests, and in

most cases between 40 per cent and 50 per cent had entered in the 10 years up to 1307, the figures do

not lend support to the notion that recruitment was noticeably declining.

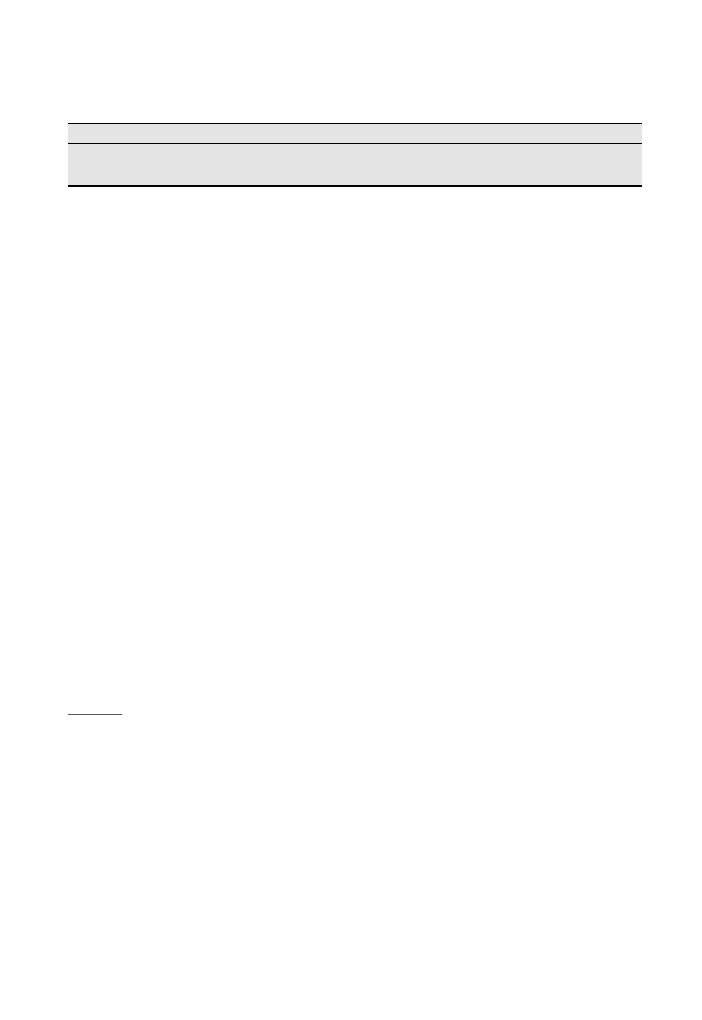

Table 2a

Dates of admission of interrogated Templars

Paris, 1307

Clermont, 1309

Aragon, 1309–10

Paris, 1309–11

Cyprus, 1310

Recruited up to 1292

52 (38.8%)

38 (56.7%)

38 (39%)

91 (40.4%)

12 (16.7%)

Recruited 1293–1307

82 (61.2%)

29 (43.3%)

59 (61%)

134 (59.6%)

60 (83.3%)

Total

134

67

97

225

72

17

L.B. Larking, The Knights Hospitallers in England (Camden Society, first series 65, London, 1857), passim; D. Selwood, Knights

of the cloister. Templars and Hospitallers in central-southern Occitania, 1100–1300 (Woodbridge, 1999), 158; cf. J. Gle´nisson,

‘L’Enqueˆte pontificale de 1373 sur les possessions des Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean-de-Je´rusalem’, Bibliothe`que de l’E

´cole des

Chartes, 129 (1971), 92; Forey, ‘Recruitment’, 145.

18

Half of the knights interrogated in Paris between 1309 and 1311 had joined the order before the loss of Acre, but it is

difficult to draw any conclusions from this evidence, partly because some young knights recruited in France were in the East.

19

Delaville Le Roulx, Cartulaire, vol. 4, 23–4, doc. 4550, art. 2; C.L. Tipton, ‘The 1330 chapter general of the Knights Hospitallers

at Montpellier’, Traditio, 24 (1968), 305–6; Legras, ‘Effectifs’, 363.

20

Michelet, Proce`s; R. Se`ve and A.-M. Chagny-Se`ve, Le Proce`s des Templiers d’Auvergne, 1309–1311 (Paris, 1986); Finke,

Papsttum, vol. 2, 364–72 doc. 157; Barcelona, Archivo Capitular, codex 149; K. Schottmu¨ller, Der Untergang des Templer-Ordens, 2

vols (Berlin, 1887), vol. 2, 143–400; A. Gilmour-Bryson, The trial of the Templars in Cyprus. A complete English edition (Leiden,

1998). There is some overlap between the groups questioned in France: overall totals of those questioned are therefore not

given.

21

The figures do not take into account those held in Muslim captivity in Egypt at the time of the trial: these included some

captured at Ruad in 1302 who were fairly recent recruits, such as the Aragonese brothers William of Castellbisbal and G. of Bac,

who had entered the order in the mid-1290s: Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 2, 453; Masia´ de Ros, La Corona de Arago

´n y los estados del

norte de Africa, 299–300, doc. 32; Forey, Fall of the Templars, 217.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

153

The number of brothers in many western houses at the time of the arrests was certainly small,

which might be taken to suggest declining numbers, but it is usually difficult to make comparisons

about the personnel in houses in different periods of Templar history. Moreover, some indicators of

generally declining numbers and a shortage of recruits to which attention has been drawn are of

questionable value. Although it has been noted that the number of brothers who can be traced in some

Aragonese convents declines in the later thirteenth century,

this comment is based on lists of

brothers in documents issued in the name of the Templars and may reflect merely scribal practice

rather than an actual diminution in numbers: the decline is not apparent in the documentation of all

Aragonese convents. The Aragonese provincial master Berenguer of Cardona also on one occasion

wrote to the commander of Mallorca saying that he could not meet the latter’s request for some

brothers to be sent to the island; but the master was ready to allow men to be recruited in Mallorca: the

letter does not indicate that potential recruits were lacking.

It has also been observed that the

number of silver spoons in English Templar houses recorded in inventories compiled when the

brothers were arrested was usually greater than the number of Templars known to have been resident

in 1307.

Yet it needs to be established that such spoons were intended exclusively for the use of

brothers, and not also for guests. It has further been alleged that the Templars could no longer man all

their conventual houses: the records of the Templar trial show, for example, that heads of some

neighbouring commanderies were living in the convents of Montpellier and St Gilles.

But it needs to

be demonstrated that these commanderies had at one time been independent of Montpellier or St

Gilles, and had not always been merely dependencies of these houses: those administering depen-

dencies remained members of their mother convent and were often mentioned among those

approving documents issued in the name of the convent. There is, however, evidence of the apparent

downgrading of some Templar houses in England. The existence of dormitories was recorded at the

time of the arrests of the Templars at Dokesworth (Duxford) in Cambridgeshire and Templehurst in

Yorkshire, but these houses each then contained only one brother other than the preceptor; and there

were no brothers at Rockley in Wiltshire, where there was a refectory and chapel.

Downgrading

could, of course, result from reorganisation rather than a decline in the supply of recruits: the Templar

convent of Chivert in Valencia was downgraded when the castle of Pen

˜ ı´scola, which was acquired in

1294, became the centre of Templar administration in northern Valencia;

and it has been pointed out

that the downgrading of South Witham in Lincolnshire, which at the time of the arrests was admin-

istered by a lay bailiff, may have been occasioned by the nature of the site rather than a lack of

recruits.

Downgrading might in some cases also be explained by a lack of resources to maintain an

establishment rather than a lack of potential recruits. In the later thirteenth century the Temple, like

the Hospital, was experiencing financial difficulties which were occasioned by the loss of estates in the

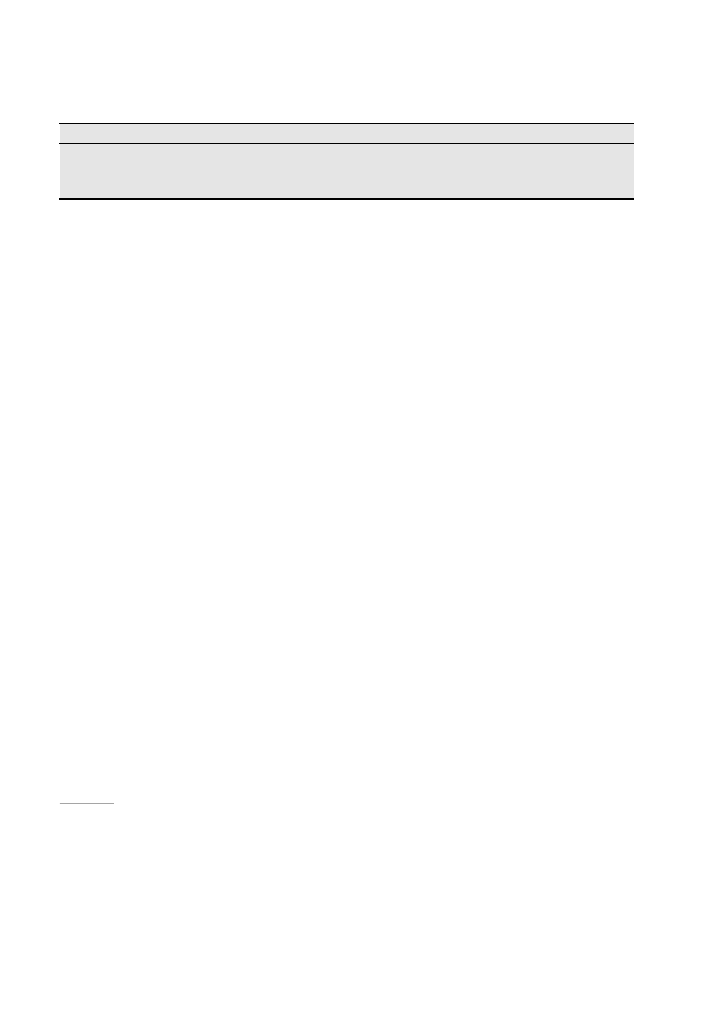

Table 2b

Dates of admission of those recruited 1293–1307

Paris, 1307

Clermont, 1309

Aragon, 1309–10

Paris, 1309–11

Cyprus, 1310

Recruited 1293–97

19

7

19

26

7

Recruited 1298–1302

32

7

22

53

21

Recruited 1303–07

31

15

18

55

32

Total

82

29

59

134

60

22

A.J. Forey, The Templars in the Corona de Arago

´n (London, 1973), 278; Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 128.

23

Barcelona, Archivo de la Corona de Arago´n (henceforth ACA), Cancillerı´a real, Cartas reales diploma´ticas (henceforth CRD),

Templarios 285; see also CRD, Templarios 371.

24

Gooder, Temple Balsall, 83–4.

25

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 127; see L. Me´nard, Histoire civile, eccle´siastique et litte´raire de la ville de Nismes, 7 vols (Paris,

1750-8), vol. 1, Preuves, 198–201, 203–4, 207–8.

26

Gooder, Temple Balsall, 83.

27

Forey, Templars in the Corona de Arago

´n, 102.

28

Gooder, Temple Balsall, 83. On buildings at South Witham, see E. Lord, The Knights Templar in Britain (Harlow, 2002), 100–1;

‘South Witham’, Current Archaeology, 9 (1968), 232–7.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

154

East, the dwindling of donations in the West, reductions in privileges and immunities, and the obli-

gation to contribute to new forms of royal and papal taxation.

Financial hardship is apparent not only

from letters stressing the lack of funds but also from the alienating of property to meet current

expenses. It might, of course, be argued that after the loss of the Holy Land the Temple was spared the

costs of maintaining castles and garrisons there, but after 1291 the Templars still had a military role in

Armenia and they held the island of Ruad, off the Syrian coast, from 1300 until 1302. The order’s

headquarters on Cyprus had to be maintained and there was also the cost of shipping men and supplies

out to the East, besides naval expenses in the eastern Mediterranean. That the financial situation

remained difficult after 1291 is apparent from continued requests for supplies from the West in

addition to the normal responsions: in 1300, for example, the Aragonese provincial master received

a plea from James of Molay to give all possible assistance to those in the East.

It was also reported that

in the mid-1290s instructions were issued to restrict Templar almsgiving because of the lack of funds,

and at the time of the Templars’ arrest a considerable number of the order’s properties were in a state

of disrepair. In England, for example, a fulling mill at Witham was derelict and another mill at Rothley

was broken down,

and at Bretteville in Normandy extensive repairs to buildings had to be made

before the property could be farmed out by French royal officials in 1309.

Repairs were similarly

undertaken in Aragon while Templar property was in royal hands: among buildings restored was the

parish church of Orrios, which was said in 1310 to be in such a ruinous state that services could not be

held there.

If there was in fact any reduction in overall numbers, it may have been because the order was

seeking to restrict recruitment at a time of financial difficulty, as some monasteries did in the thir-

teenth century and as the Hospital was doing in the early fourteenth,

rather than because there was

a lack of potential recruits. There are indications that in the Temple’s later years provincial masters

were keeping a close control on recruitment and that heads of houses were not allowed complete

freedom of action. In his testimony during the Templar trial Ponzard of Gizy stated that ‘the said

masters of bailiwicks seek permission from provincial commanders to create brothers.’

Examples of

permission being given are provided by letters written at the turn of the thirteenth and fourteenth

centuries by the Aragonese provincial master Berenguer of Cardona to Peter of San Justo when the

latter was commander of Corbins and later when he had charge of the convent in Mallorca: needed

recruits were to be admitted.

Many Templar witnesses also stated during the trial that they had been

admitted by a local Templar official on the orders or authority of a superior, often a provincial master or

visitor, implying a degree of central control of recruitment.

The backing and support of family and

influential friends were also sometimes still necessary at the turn of the thirteenth and fourteenth

centuries to gain admission, as they had been earlier. During the trial a non-Templar witness in Paris

stated that about the year 1300 an individual had sought his help in gaining admission to the order, and

Robert le Brioys, who had entered the Temple about 1297, asserted that his request for admission had

been supported by the bishop of Be´ziers.

Several Templars also claimed that simoniacal admissions

29

On Templar acquisitions and privileges in Aragon, see Forey, Templars in the Corona de Arago

´n, caps. 2, 4.

30

H. Finke, Acta Aragonensia, 3 vols (Berlin, 1908–22), vol. 1, 78–9, doc. 55.

31

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 629, 641; vol. 2, 87–8.

32

Gooder, Temple Balsall, 86.

33

Miguet, Templiers et Hospitaliers en Normandie, 177–8.

34

ACA, Cancillerı´a real, registro 291, f. 273; Forey, Fall of the Templars, 137.

35

U. Berlie`re, ‘Le Nombre des moines dans les anciens monaste`res’, Revue be´ne´dictine, 41 (1929), 231–61; 42 (1930), 19–42;

G.G. Coulton, Five centuries of religion, 4 vols (Cambridge, 1923–50), vol. 3, 540–58.

36

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 38.

37

ACA, CRD Templarios 285, 400.

38

See, for example, Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 265, 342, 418, 541, 605, 611. A. Demurger, ‘Le Personnel des commanderies

d’apre`s les interrogatoires du proce`s des Templiers’, in: La Commanderie. Institution des ordres militaires dans l’Occident

me´die´val, ed. A. Luttrell and L. Pressouyre (Paris, 2002), 139–40, points out that in Provence a large proportion of Templars

questioned had been admitted by the provincial master, although this trend was less marked in more northerly parts of

France: but the important issue is the extent to which admissions were controlled by the heads of provinces.

39

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 184, 449; see also vol. 2, 259, 351.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

155

were still common: some recruits had to pay to be admitted.

It should also be remembered that

younger sons who did not obtain a share of family properties still had to find a livelihood, and that for

many of them entry to a military order may have been more attractive than enclosure in a monastery.

Although no decrees issued by the Temple survive, as they do for the Hospital, which was seeking to

ensure that recruitment did not place a strain on resources in the early fourteenth century, it is

nevertheless possible that the Templars were imposing restrictions on recruitment rather than

suffering from a lack of postulants.

Role of sergeants

It has been argued that besides being more numerous in the Temple than in the Hospital, sergeants

comprised a more significant component of the former order than of the latter.

They were certainly

appointed to some important Templar offices in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. At

the order’s headquarters certain positions were filled by brothers of this rank. Apart from the posts

listed in Templar regulations as the preserve of sergeants,

the office of treasurer in Cyprus in the early

fourteenth century was held by Peter of Castello´n, who was a sergeant, as were all the brothers

interrogated in Cyprus who had held the posts of almoner or infirmarer.

The two Templar treasurers

in Paris called John of Tour were similarly sergeants, as was their predecessor Humbert,

and many

preceptors in France were of that rank, some of them holding leading positions: the sergeants Auvret

and Philip Agate were preceptors of Normandy, and the last three commanders of the important

commandery of Ponthieu belonged to the rank of sergeant.

In France, knights appear at times to have

been subordinate to sergeants.

In Aragon, on the other hand, where the Templars still had a military

role, sergeant commanders were few and tended to be placed in charge of lesser convents or those

sited in cities: they were not usually given command of convents located in castles.

In making use of

sergeants in administrative positions, especially in areas away from the frontiers of Christendom, the

Temple was taking advantage of the skills possessed by some brothers of this rank, and Templar

practice can hardly be looked upon in this context as being archaic, even if the exercise of authority by

sergeants over knights may in some instances have aroused resentment.

Much of the information about the rank of office-holders in the Temple comes from the records of

the trial, and it is more difficult to discover the status of individual Hospitaller officials in the late

40

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 38; vol. 2, 206; Finke, Papsttum, vol. 2, 338, doc. 155.

41

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 125.

42

La Re

`gle du Temple, ed. H. de Curzon (Paris, 1886), 113, art. 143.

43

Schottmu¨ller, Untergang, vol. 2, 184, 262, 296, 298, 301, 303; Gilmour-Bryson, Trial in Cyprus, 106, 210, 255, 257, 260, 263;

A.J. Forey, ‘Letters of the last two Templar masters’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, 45 (2001), 164–5, 168–70, docs. 11, 17; Finke,

Papsttum, vol. 2, 371, doc. 157.

44

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 595; vol. 2, 192. On the treasurers in Paris, see L. Delisle, Me´moire sur les ope´rations financie`res des

Templiers (Paris, 1889), 61–73.

45

Miguet, Templiers et Hospitaliers en Normandie, 127; A. Trudon des Ormes, ‘Liste des maisons et de quelques dignitaires de

l’ordre du Temple en Syrie, en Chypre et en France’, Revue de l’orient latin, 7 (1899), 247, 269–70. Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 126–7,

states that the sergeant William Charnier ‘seems to have reached the rank of grand commander’, signifying that he was the

head of a province. William was certainly a sergeant and one Templar witness in Italy referred to him as ‘grand preceptor in

the Patrimony of the blessed Peter in Tuscany’, while another referred to the province of Rome: Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 2, 137;

A. Gilmour-Bryson, The trial of the Templars in the Papal State and the Abruzzi (Vatican City, 1982), 202, 206, 209; T.

Bini, ‘Dei Tempieri e del loro processo in Toscana’, Atti della Reale Accademia Lucchese di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 13

(1845), 497. But the Patrimony appears not to have been a province: see F. Bramato, Storia dell’ordine dei Templari in

Italia. Le fondazioni (Rome, 1991), 90, 157–8; Gilmour-Bryson, Papal State, 131–2, 173, 188, 201–2, 214, 250; F. Tommasi,

‘L’ordine dei Templari a Perugia’, Bollettino della Deputazione di Storia Patria per l’Umbria, 78 (1981), 12, 51–2, doc. 7.

46

A.J. Forey, ‘Rank and authority in the military orders during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries’, Studia monastica, 40

(1998), 310.

47

A.J. Forey, ‘Templar knights and sergeants in the Corona de Arago

´n at the turn of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries’, in:

As ordens militares e as ordens de cavalaria na construça

˜o do mundo ocidental, ed. I.C.F. Fernandes (Lisbon, 2005), 634–5.

48

On tensions between knights and sergeants, see Forey, ‘Rank and authority’, 325–7.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

156

thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. But it has been suggested that the Hospitaller treasurer

Thomas Mausu may have been a sergeant,

and in 1338 half of the Hospitaller bailiwicks in England

and Wales were administered by sergeants. Six of these sergeant commanders had knights subject to

them: at Quenington, in Gloucestershire, where three Hospitallers resided, a sergeant had authority

over two knights.

Hospitaller practice in employing sergeants for administrative tasks was not totally

different from that of the Temple.

It has, however, further been argued that, whereas many Templar sergeants were engaged in menial

work, in the Hospital this was done by servants.

The Temple certainly used brothers for many

domestic or agricultural tasks: the functions undertaken by Templars in the Aragonese province, for

example, included those of cook, shoemaker, tailor, smith, gardener, cowherd, oxherd and shepherd,

and many were referred to by the term ‘labourer’ (operarius, obrero) and were presumably manual

workers with no particular skill.

Yet, as the number of brothers in many Templar houses was very

small, domestic tasks were inevitably performed mainly by outsiders, as was agricultural work when

some demesne farming was undertaken. At Baugy in Normandy in 1307 there were apparently only

three brothers but the Templar house there employed 27 outsiders in various capacities, including

those of cowherd, shepherd, swineherd, carter, baker, cook and porter; and an inventory compiled at

that time for Bretteville lists 12 outsiders in the service of that Norman house.

The situation in

English Hospitaller houses in 1338 seems to have been not very different, while in commanderies of the

Hospitaller priory of Provence at that time the numbers of full-time agricultural workers varied from

none to 37, the average being about 10.

It is difficult to draw a clear-cut distinction between the

Temple and Hospital in the employment of outsiders for domestic and agricultural tasks.

Ignorance

It is true that many Templars in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries had an inadequate

grasp of their order’s rule and regulations.

The evidence is found in testimonies provided during the

Templar trial, and there is, of course, no comparable evidence for other military orders, although the

Teutonic order did find it necessary to decree that a penance should be imposed on brothers who failed

to learn the Paternoster, Creed and Hail Mary within six months of entry and that a more severe

punishment should be meted out to those who had not mastered them after a year.

But it would be

surprising if brothers of the Hospital, or of other military orders, were much better informed than

Templars. Members of the various orders came from similar backgrounds and the majority were

laymen; and there is no evidence of a novitiate in the Hospital during which recruits might receive

formal instruction, while in the Teutonic order a probationary period was not compulsory.

Although

in most military orders vernacular copies existed of rules, statutes and customs, many lay brothers

were probably incapable of reading them, and in all orders it was assumed that regulations would be

assimilated partly by periodic public readings: that this practice was not just an obsolete survival from

earlier monastic usage is indicated by the Hospital enacting a decree in 1293 stating that a part of the

49

J. Burgtorf, ‘Leadership structures in the orders of the Hospital and the Temple (twelfth to early fourteenth century):

select aspects’, in: The crusades and the military orders. Expanding the frontiers of medieval Latin Christianity, ed. Z. Hunyadi and

J. Laszlovsky (Budapest, 2001), 384–5.

50

Forey, ‘Rank and authority’, 311.

51

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 126.

52

Forey, Templars in the Corona de Arago

´n, 280–1.

53

L. Delisle, E

´tudes sur la condition de la classe agricole et de l’e´tat de l’agriculture en Normandie au moyen aˆge (Evreux, 1851),

721–4; G. Lizerand, Le Dossier de l’affaire des Templiers (Paris, 1964), 46–54; cf. M. Miguet, ‘Le Personnel des commanderies du

Temple et de l’Hoˆpital en Normandie’, in: La Commanderie, 96.

54

Larking, Hospitallers in England, xxx–xxxii, xxxiv–xxxv; B. Beaucage, ‘L’Organisation du travail dans les commanderies du

prieure´ de Provence en 1338’, in: La Commanderie, ed. Luttrell and Pressouyre, 110–12.

55

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 131; A.J. Forey, ‘Novitiate and instruction in the military orders during the twelfth and thirteenth

centuries’, Speculum, 61 (1986), 15–16.

56

M. Perlbach, Die Statuten des Deutschen Ordens nach den a

¨ltesten Handschriften (Halle, 1890), 61, Gesetze II(e).

57

Forey, ‘Novitiate’, 2, 4–5.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

157

order’s statutes should be read at every chapter.

It has been stressed that the Templars decreed that

no brother should have a copy of the rule or statutes without the permission of the central convent

d

only brothers in positions of authority were expected to have them d and that many brothers

interrogated in the early fourteenth century said that they had never seen a copy of the rule;

but in

1283 the Hospitallers themselves decreed that no brother should possess a copy of the rule and statutes

unless he had authority over other brothers or had the master’s permission.

How many houses of

military orders actually possessed copies of rules and regulations is not known. Certainly only a limited

number of copies of the Templar rule and customs are known to have been seized when brothers were

arrested,

but the evidence is, of course, far from complete. It has been claimed that the Hospitallers

‘seem to have circulated their rule and statutes widely’, but there is no evidence to indicate what

proportion of Hospitaller convents possessed copies of the order’s regulations.

It would certainly be

rash to assume that Hospitaller houses usually possessed a copy of the rule and statutes, for the

Teutonic order found it necessary to decree that every house of the order should have a copy of its

rule,

and in the thirteenth century even some monasteries d where the literacy rate would have

been higher than in military orders d possessed no copy of their rule.

Provincial administration

A number of differences in structure and organisation at the provincial level of administration has been

postulated between the Temple and Hospital. Hospitaller priories and Templar provinces have been

compared, and it has been argued that the Hospitallers displayed a preference for smaller adminis-

trative units at this level: they therefore had a greater number of senior officials who were in

communication with the East.

The number of Hospitaller priories in European lands certainly

58

Delaville Le Roulx, Cartulaire, vol. 3, 638–40, doc. 4234, art. 7; cf. Forey, ‘Novitiate’, 14.

59

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 129–30; for the Templar regulation, see, Re

`gle du Temple, 189, art. 326; see also Michelet, Proce`s,

vol. 1, 388.

60

Delaville Le Roulx, Cartulaire, vol. 3, 450–5, doc. 3844, art. 7; cf. A. Luttrell, ‘The Hospitallers’ early statutes’, Revue Mabillon,

75 (2003), 12.

61

Fewer than a dozen copies in Aragonese lands are mentioned in surviving inventories and other documentation relating to

Templar possessions passing into James II’s hands: J. Villanueva, Viage literario a las iglesias de Espan

˜a, 22 vols (Madrid,

1803–52), vol. 5, 200–2, doc. 2; J. Rubio´, R. d’Alo´s and F. Martorell, ‘Inventaris ine`dits de l’orde del Temple a Catalunya’, Anuari de

l’Institut d’Estudis Catalans, 1 (1907), 393–6, doc. 4; F. Martorell y Trabal, ‘Inventari dels bens de la cambra reyal en temps de

Jaume II (1323)’, Anuari de l’Institut d’Estudis Catalans, 4 (1911–12), 553, 562–6; J.E. Martı´nez Ferrando, ‘La ca´mara real en el

reinado de Jaime II (1291–1327). Relaciones de entradas y salidas de objetos artı´sticos’, Anales y Boletı´n de los Museos de Arte de

Barcelona, 11 (1953–54), 182–98, doc. 134 (in this and the preceding source seven copies in the king’s hands in 1323 are listed);

J. Masso´ Torrents, ‘Inventaris dels bens mobles del rey Martı´ d’Arago´’, Revue hispanique, 12 (1905), 415, 420, 422, 435, 453 nos 6,

39, 53, 154, 285 (this lists five in the early fifteenth century). A copy belonging to the house of Mas-De´u in Roussillon, which

formed part of the Aragonese province, was surrendered by a Templar chaplain to the bishop of Elne in 1310: Michelet, Proce`s,

vol. 2, 434.

62

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 130. Reference is made there to A. Luttrell, ‘ The Hospitallers’ early written records’, in: The

crusades and their sources. Essays presented to Bernard Hamilton, ed. J. France and W.G. Zajac (Aldershot, 1998), 143–6, but this

essay mentions merely a handful of manuscripts.

63

Perlbach, Statuten, 63, Gesetze III(b); 71, Gesetze 17.

64

C.R. Cheney, Episcopal visitation of monasteries in the thirteenth century, 2nd edn (Manchester, 1983), 157–8, 168. It has also

been argued that on some issues, such as the nature of chapters and various types of legislation, many Templars were confused:

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 136, 141. Yet it does not follow that, because the term ‘general chapter’ was used of both provincial and

central assemblies, brothers could not distinguish between them; and it would be surprising if all Templars interrogated during

the trial had a clear notion of the various types of regulation. Whether a clear distinction between types of legislation was

necessary for efficient government may be questioned. Certainly confusion about forms of legislation was by no means

unknown in the Hospital: see Luttrell, ‘Hospitallers’ early written records’, 151; Luttrell, ‘Hospitallers’ early statutes’, 15, 17; and

it can hardly be claimed that Hospitaller regulations constituted a coherent and user-friendly collection of rulings.

65

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 131–2, 141.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

158

exceeded that of Templar provinces: one estimate is that the Hospitallers had 23 priories and the

Templars 12 or 13 provinces.

Yet Hospitaller priories varied greatly in size and importance. The

French houses of the Hospital were grouped into only three priories,

whereas there were apparently

nine in Italy. The number in the latter peninsula was hardly justified by geographical extent or by the

importance of Italy to the Hospital: in 1302 the Italian priories were together expected to provide only

13 brethren-at-arms to serve in the East, while the three French priories were to supply a total of 41.

And although the Hospitallers had four priories in the Iberian peninsula, that of Castile and Leon

covered the larger part of the lands under Christian rule, and was very much larger than those of

Portugal and Navarre. It is therefore difficult to discern any consistent Hospitaller policy of creating

small provinces. It has been suggested that in some cases provincial boundaries were determined by

linguistic frontiers;

but these were not always very clear-cut, and the limits of both Hospitaller

priories and Templar provinces were more clearly influenced by political frontiers. Although bound-

aries of Hospitaller priories in Italy did not necessarily conform to existing political divisions, the

creation of numerous priories there may be in part a reflection of the political fragmentation which

characterised the country.

A further difference at the level of the province which has been postulated is that Templar provincial

masters were itinerant, whereas Hospitaller priors had a fixed base.

The Templar master of Aragon

and Catalonia was certainly not based at a central convent, although a provincial archive and possibly

a provincial treasury were housed at Miravet on the lower Ebro in the later thirteenth century.

Yet it

needs to be demonstrated that the itinerant character of the Aragonese provincial master was typical.

The head of the English province presumably spent much of his time in London, where he had

a chamber at the New Temple,

and probably the provincial master of France similarly resided mainly

in Paris: the provincial chapter certainly normally met there.

The distinction between sedentary and

itinerant heads of provinces or priories should also not be exaggerated. The heads of all provinces or

priories spent a considerable amount of time in visitations of houses subject to them. In 1338 the

English Hospitaller prior, who was based in London, was undertaking visitations for 121 days in the

year.

It has further been suggested that within Templar provinces, commanderies were grouped into

bailiwicks, while this practice was not generally adopted in Hospitaller priories.

Templar organisation

within provinces has been insufficiently investigated, and for some regions there is a lack of detailed

evidence. Difficulties are also created by the imprecision of the terminology employed in surviving

documents: words such as ‘commander’, ‘preceptor’ and ‘bailiff’ could be used in varying contexts, and

interchangeably. An official bearing one of these titles could be the head of a province, have charge of

a Templar convent, be responsible for a dependency of a convent, or have a more menial task: those in

charge of animals were sometimes called preceptors or commanders of sheep, cows or pigs.

The

66

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 131–2.

67

Templar lands in France and Provence constituted at least four provinces. E.G. Le´onard, Introduction au cartulaire manuscrit

du Temple du Marquis d’Albon (Paris, 1930), 19–20, discusses the evidence about the status of Normandy and comes to the

conclusion that it formed part of the province of France; cf. Demurger, Templiers, 149. For an alternative view, see Miguet,

Templiers et Hospitaliers en Normandie, 13.

68

Delaville Le Roulx, Cartulaire, vol. 4, 36–41, doc. 4574, art. 14.

69

J. Riley-Smith, The Knights of St John in Jerusalem and Cyprus, c.1050–1310 (London, 1967), 353; A. Soutou, ‘Les Templiers et

l’aire provençale: a` propos de ‘‘La Cabane de Monzon’’ (Tarn-et-Garonne)’, Annales du Midi, 88 (1976), 93.

70

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 133.

71

Forey, Templars in the Corona de Arago

´n, 315–16; A.J. Forey, ‘Sources for the history of the Templars in Aragon, Catalonia and

Valencia’, Archives, 21 (1994), 16–17.

72

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 454, f. 61, 92, 125, 127v; D. Wilkins, Concilia magnae Britanniae et Hiberniae, 4 vols

(London, 1737), vol. 2, 348, 371–2. References to a master’s chamber in some other English houses occur, but these may

merely indicate a room which was temporarily assigned to him while he was staying: London, British Library, Cotton MS

Julius B xii, f. 74; MS Bodley 454, f. 40–1, 155; Wilkins, Concilia, vol. 2, 343.

73

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 399, 413, 501, 514, 535, 553, 627–8; vol. 2, 35–6; Delisle, Ope´rations financie`res, 176, 208.

74

Larking, Hospitallers in England, 211.

75

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 127.

76

Forey, Templars in the Corona de Arago

´n, 281; Me´nard, Histoire de Nismes, vol. 1, Preuves, 186, 189, 198, 199, 207, 214.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

159

terms ‘bailiwick’ (baiulia) and ‘house’ (domus) could similarly be used in a variety of contexts. It is

therefore often difficult to discern the precise nature of Templar establishments. Furthermore, little is

usually known in detail about arrangements for the payment of responsions to the head of a province

and it is difficult to trace which Templars attended provincial chapters: information on these topics

could throw considerable light on administrative organisation.

The evidence for the Aragonese province is, however, fuller than that for other regions, and the

administrative organisation there is relatively clear. In 1307 there were 36 houses or convents d the

latter term was commonly used in Aragonese documents d which were assessed for responsions and

paid them directly to the provincial master.

There were no intermediate officials between the heads

of these convents and the central authorities of the province, even though the province covered several

distinct political units. The order admittedly had only two convents in the kingdom of Navarre d at

Aberı´n and Ribaforada

d

and the same number in the kingdom of Mallorca, which was not created

until James I’s death in 1276. Yet there was no deputy of the provincial master who had overall charge

in Aragon or Catalonia. The convents consisted of a commander or preceptor and a varying d often

fairly small d number of brothers, who normally included a ‘keeper of the keys’ (claviger) or ‘cham-

berlain’ (camerarius). These houses also usually had a chapel

and a chaplain, although the latter was

not necessarily a member of the order. It was in these convents that all the recorded admissions in the

province took place.

Within the district subject to each of these establishments brothers were often

appointed, with the title of commander or preceptor, to have charge of the administration of a group of

estates.

These subordinate officials remained members of their mother house, and were answerable

to the head of the convent. They might spend most of their time at the convent, but sometimes

a subordinate commander was accompanied by one or more other brothers and a small dependent

house was created; some of these even had chapels.

Yet these brothers remained under the authority

of the head of the convent. Arrangements about appointing subordinate commanders were, however,

often flexible, and at times the tasks performed by such nominees were carried out by laymen.

Although the surviving documentation for the Catalan convent of Gardeny is very considerable and

a subordinate commander of Segria´ can be traced throughout the thirteenth century, a commander of

Urgel was mentioned only in 1282 and between 1296 and 1302, while a commander of Escarabat was

named only in 1278.

It is clear, however, that there were in the Aragonese province no more than two

levels of administration below the provincial master: convents were not grouped into larger bailiwicks.

As Castile, Leon and Portugal were usually subject to a single provincial master, a deputy for Castile

and Leon was at times appointed with the title of comendador mayor,

but there is no other evidence of

77

Forey, Templars in the Corona de Arago

´n, 415–19, doc. 45.

78

On the Templars in Navarre, see S.A. Garcı´a Larragueta, ‘ El Temple en Navarra’, Anuario de estudios medievales, 11 (1981),

635–61.

79

Several Templar communities, however, held services in nearby parochial churches: J. Fuguet Sans, L’arquitectura dels

Templers a Catalunya (Barcelona, 1995), 235 n. 8.

80

Finke, Papsttum, vol. 2, 364–72, doc. 157; Barcelona, Archivo Capitular, cod. 149; Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 2, 423–515.

81

For lists and comment, see Forey, Templars in the Corona de Arago

´n, 270–1, 451–2. To those named should be added Rourell,

which was a dependency of Barbera´: see J.M. Sans i Trave´, ‘El Rourell, una preceptoria del Temple al Camp de Tarragona

(1162?–1248)’, Boletı´n arqueolo

´gico, 103–4 (1976–7), 133–201. For the dependencies of Mas-De´u in Roussillon, see L. Verdon, La

Terre et les hommes en Roussillon aux XIIe et XIIIe sie`cles. Structures seigneuriales, rente et socie´te´ d’apre`s les sources templie`res

(Aix-en-Provence, 2001), 24; and for those of Huesca, A. Conte, La encomienda del Temple de Huesca (Huesca, 1986), 57–8.

82

The Templar house of Barcelona, for example, had its own chapel from the mid-thirteenth century, even though it was then

dependent on the convent of Palau: Fuguet Sans, Arquitectura dels Templers, 286–8. H. Nicholson, The Knights Templar. A new

history (Stroud, 2001), 123, states that in 1198 there were at least nine members of the Temple at Rourell, which was subject to

Barbera´, but this would be an exceptionally large number for a dependency, and possibly not all those listed in the relevant

document were normally resident there: Colleccio

´ diploma

`tica de la casa del Temple de Barbera

` (945–1212), ed. J.M. Sans i Trave´

(Barcelona, 1997), 286–7, doc. 193.

83

Information about these offices is found in the Gardeny parchments in ACA, Ordenes religiosas y militares, San Juan de

Jerusale´n.

84

G. Martı´nez Diez, Los Templarios en la Corona de Castilla (Burgos, 1993), 55, 61.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

160

the grouping of houses into bailiwicks in these kingdoms. The summons sent out during the Templar

trial by the archbishop of Toledo to brothers in Castile and Leon does allude to Templars ‘who used to

live in the houses of Cebolla and Villalba which belong to the bailiwick of Montalba´n’,

but the word

‘bailiwick’ (bayliva) was used in this document of almost all Templar establishments in Leon and

Castile: Cebolla and Villalba were probably merely dependencies of Montalba´n.

More than a century ago Trudon des Ormes maintained that Templar houses in France were by

contrast grouped into 11 bailiwicks, and his opinion has been repeated a century later.

But some of

the bailiwicks which he identified were provinces, while others were not, and he admitted that his

groupings were often tentative and in some cases merely guesswork.

Yet, although the use of the

term baiulia in French sources is not necessarily significant, there is evidence to suggest that the

grouping into bailiwicks of houses which were comparable to the convents in Aragon was the custom

in various regions of France. Commanders were said sometimes to be in charge of Templar houses in

a region, or to be commanders of a district rather than just a house, even in the later period of Templar

history. In 1254 a brother Hugh was preceptor of the houses of the Temple in Brie and in 1274 William

Borelli was preceptor of the houses of the Temple in the bailiwick of Chartres, while Templar estab-

lishments in the county of Burgundy were administered by a ‘preceptor of the houses of the Temple in

Burgundy’.

In 1245 Peter Langan was preceptor of the houses of the Temple in Brittany,

and there

was also a preceptor of Normandy.

In some places there were two commanders d one of the baiulia,

with apparently wide authority, and the other of the house itself where the baiulia was centred: the

latter was not called merely sub-commander, as existed in some convents in certain periods in the

order’s history. Robert of St Just was reported to have been preceptor of the bailiwick of Sommereux

about the year 1294, while Peter of Bresle was preceptor, presumably only of the house there.

John of

Tour was similarly preceptor of the baiulia of E´tampes when Arnulf of Champenelhe was preceptor of

E´tampes itself.

It is often difficult to distinguish which officials had authority over a larger bauilia and

which ruled merely a house, but the existence of two commanders in the same place lends support to

the notion that houses were sometimes grouped into bailiwicks. It may also be noted that some

commanders conducted receptions in neighbouring houses or gave instructions that a recruit should

be admitted in a nearby foundation. The places where recruits were received by the commander of

Ponthieu or on his command included Beauvoir, Forest-l’Abbaye, Grandselve, Loison, Mouflie`res and

Oisemont,

and the Templar in charge of Chartres was responsible for admissions at several houses

including Arville, La Bossie`re and Villedieu-les-Maurepas.

Such receptions were sometimes stated to

have been conducted in the presence of the commander of the house where the recruit was admitted.

Regional commanders also involved themselves in other ways in the affairs of particular houses in the

district: in 1300, for example, the ‘commander and procurator of the houses of the knighthood of the

Temple of Brie’ took action in a dispute between the Templars of Provins and the prior of Saint-Ayoul.

It is, of course, often difficult to be certain about the status of some subordinate houses and to discover

whether they housed a Templar community similar to an Aragonese convent, or were just granges

85

F. Fita y Colome´, Actas ine´ditas de siete concilios espan

˜oles celebrados desde el an

˜o 1282 hasta el de 1314 (Madrid, 1882),

81; A. Javierre Mur, ‘Aportacio´n al estudio del proceso contra el Temple en Castilla’, Revista de archivos, bibliotecas y museos, 69

(1961), 75–8, doc. 3.

86

Trudon des Ormes, ‘Liste des maisons’, Revue de l’orient latin, 5 (1897), 392, 440–2; M. Barber, The new knighthood. A history

of the order of the Temple (Cambridge, 1994), 229.

87

Trudon des Ormes, ‘Liste des maisons’, Revue de l’orient latin, 5 (1897), 390, 394, 443.

88

Le´onard, Introduction, 121, 145, 155; J. Richard, ‘Les Templiers et les Hospitaliers en Bourgogne et en Champagne me´r-

idionale (XIIe–XIIIe sie`cles)’, in: Die geistlichen Ritterorden Europas, ed. J. Fleckenstein and M. Hellmann (Sigmaringen, 1980),

232.

89

Le´onard, Introduction, 109.

90

A list of preceptors of Normandy is given by Le´onard, Introduction, 116.

91

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 241–2.

92

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 598.

93

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 243, 328, 374, 444, 465, 468–9, 480, 481, 488, 489, 491, 622; vol. 2, 1, 75, 132; Schottmu¨ller,

Untergang, vol. 2, 63; Finke, Papsttum, vol. 2, 331, doc. 155.

94

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 543, 558; vol. 2, 184, 288.

95

V. Carrie`re, Historie et cartulaire des Templiers de Provins (Paris, 1919), 165–8, doc. 159.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

161

where no more than a single Templar was resident. Yet the office of claviger is recorded in some houses

which lay within a bailiwick, which suggests that they were more than small dependencies: a Templar

who was questioned at Poitiers in 1308 held that post at Campagne, which was stated to be in the

bailiwick of Ponthieu.

Houses which apparently formed part of a bailiwick also in some instances had

their own subordinate houses, implying a three-tier level of administration below the level of

provincial master: an inventory compiled in 1309 thus lists the houses or granges dependent on Mont-

de-Soissons, which seems to have lain in the bailiwick of Brie; and Moisy, which apparently also lay in

the same bailiwick, apparently had La Sablonnie`re and Nanteuil-le`s-Meaux among its dependencies.

Houses which were under the authority of the preceptor of Normandy similarly had dependencies.

That at Renneville had several, including Brettemare and Beaulieu; and according to an inventory of

Fresnaux drawn up in 1307, that house had one brother resident at Louvigny.

Payments made at the

time of provincial chapters in Paris in 1295 and 1296 include some made by houses which lay within

bailiwicks, such as Mont-de-Soissons and Moisy: these houses were presumably paying the respon-

sions for which they were responsible.

Admittedly, evidence of these kinds is not necessarily to be accepted in all cases. In the testimonies

given by Templars during the trial there were no doubt lapses of memory and in some cases confusion:

one brother questioned in Paris in 1311 said that he had been admitted to the order c.1306 by Gerard of

Villiers, preceptor of Brie and Mont-de-Soissons; but Gerard was in fact then master of the province of

France.

Nor did the admission of a recruit by a preceptor of another house always signify that the

latter was the head of the bailiwick conducting a ceremony in a subordinate house: although some

admissions at Neuville were conducted by the commander of Chaˆlons-sur-Marne, who was apparently

the head of the bailiwick in which Neuville was situated, the commanders of Reims and of Payns are

also known to have received recruits there.

Nor should it be assumed that all houses where

admissions took place were more than granges, for several Templars stated that they had entered the

order at places which were described merely as granges.

But the evidence is sufficient to indicate the

grouping of houses which were more than small dependencies into bailiwicks in several parts of

France.

Yet the grouping of such houses into bailiwicks may not have been practised in all parts of the

province of Provence. It has recently been pointed out that Provençal sources make no reference to

bailiwicks as a tier of organisation between the province and the commandery;

and records of the

interrogations of Templars conducted during the Templar trial at Nıˆmes, Aigues-Mortes and Ale`s allude

to the convent as the main unit of organisation: those mentioned include St Gilles, Montpellier and Le

Puy-en-Velay, and brothers who had charge of lesser establishments were listed among the members

of such convents.

Although it has been suggested that in the south the convent was the equivalent of

the bailiwick in the north,

it is arguable that in some districts the administrative organisation was

similar to that in north-eastern Spain, which until 1240 was linked to Provence to constitute a single

province of ‘Provence and certain parts of Spain’.

It has been maintained that the English province was also divided into bailiwicks, within which the

various preceptories or commanderies lay.

Certainly in the inquest compiled in 1185 Templar

96

Schottmu¨ller, Untergang, vol. 2, 63.

97

Le´onard, Introduction, 127–8. For a reception at La Sablonnie`re by the commander of Moisy, see Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 520.

98

Miguet, Templiers et Hospitaliers en Normandie, 293–6; Delisle, E

´tudes, 727–8.

99

Delisle, Ope´rations financie`res, 176–8, 209–10.

100

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 637.

101

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 406-7.

102

Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 2, 181, 336; Me´nard, Histoire de Nismes, vol. 1, Preuves, 176.

103

D. Carraz, L’Ordre du Temple dans la basse valle´e du Rho

ˆne (1124–1312). Ordres militaires, croisades et socie´te´s me´ridionales

(Lyon, 2005), 98 n. 75.

104

Me´nard, Histoire de Nismes, vol. 1, Preuves, 172–219. On Templar foundations in Provence, see d apart from Carraz, Ordre du

Temple d J.-A. Durbec, ‘Les Templiers en Provence. Formation des commanderies et re´partition ge´ographique de leurs biens’,

Provence historique, 9 (1959), 3–37, 97–132; Selwood, Knights of the cloister, cap. 5; Le´onard, Introduction, 28–88.

105

Demurger, ‘Personnel’, 141.

106

Forey, Templars in the Corona de Arago

´n, 88–9.

107

Lord, Knights Templar in Britain, 22; cf. Barber, The new knighthood, 375 n. 3.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

162

properties were in some parts of England grouped into bailiwicks, but this term was not used in a very

precise sense. Lincolnshire constituted one baiulia, but within that there was the baiulia of Lindsey, and

Lindsey was divided into the smaller baiulie of Cabourn, Goulceby, Bolingbroke and Tealby.

The last

of these comprised merely some three and a half carucates of land and six tofts, and produced a yearly

rent of only £3.

The inquest makes no reference to Templar officials in charge of these districts, and in

the surveys of some parts of the country d such as Essex and Oxfordshire d the term baiulia was not

used. The groupings in the 1185 inquest were usually not of long-term significance: in most of England

there was later no intermediary between the preceptory and the provincial master. The only exception

was Yorkshire, which was described as a baiulia in 1185 and which at least from the early thirteenth

century until 1307 was subject to a preceptor of Yorkshire.

That this official had authority over

houses which can be classified as convents is suggested by lists of Templars arrested in Yorkshire in

1308, for these indicate a number of communities consisting of several Templars including a preceptor

and claviger.

There is also evidence of an intermediate official in Ireland at least from the later twelfth

century: the master of Ireland had charge of Templar houses there but was subordinate to the English

provincial master.

Although not all provinces have been examined here, and more research is needed on Templar

organisation in some regions, it would seem that Templar organisation within provinces did not

conform rigidly to a single pattern. Whereas in the Aragonese province there is no evidence of the

grouping of convents into bailiwicks, this does appear to have happened in some parts of France and in

some areas of the English province. In England, the reason for the existence of a commander of

Yorkshire is possibly that the English provincial master was based mainly in the south of England.

Remoteness probably also accounts for the existence of a master of Ireland. In parts of France, the

formation of bailiwicks may have been encouraged by the large number of Templar houses within

a province.

Yet the flexibility which apparently characterised Templar provincial organisation is also to some

extent apparent in the Hospital: in that order the creation of an intermediate level of administration

between the house and the priory was not unknown. Until the middle of the thirteenth century the

Hospital had a commander who had authority over all the houses in the district of Rouergue, and for

the rest of the century one commander had charge of houses in that region to the north of the Tarn and

another exercised supervision south of that river.

And just as the Templar provincial master of Leon,

Castile and Portugal at times had a comendador mayor to act for him in some areas, so after 1230

lieutenants were appointed in Leon and Castile to act as deputies of the Hospitaller prior of Leon and

108

Records of the Templars in England in the twelfth century. The 1185 inquest with illustrative charters and documents, ed.

B.A. Lees (British Academy, Records of the economic and social history of England and Wales, first series 9, London,

1935), xxxii, clii, 78, 100, 104, 106, 108.

109

Records of the Templars, ed. Lees, xxxii, 106.

110

E.J. Martin, ‘The Templars in Yorkshire’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 29 (1927–29), 371; J.E. Burton, ‘The Knights Templar

in Yorkshire in the twelfth century: a reassessment’, Northern History, 27 (1991), 27. A list is given in The Victoria history of the

counties of England. Yorkshire, vol. 3 (London, 1974) 257.

111

E.J. Martin, ‘The Templars in Yorkshire’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 30 (1930–31), 141.

112

H. Wood, ‘The Templars in Ireland’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 26C (1907), 332–3; Lord, Knights Templar in

Britain, 179–80. References also occur to a Templar master or preceptor of Scotland: see, for example, Calendar of documents

relating to Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1884), 125, 126–7, 147. Yet there appear to have been only two Templar establishments in

Scotland d at Balantrodoch and Maryculter d and in the records of the Templar trial only four brothers resident in Scotland

d

including two fugitives d are mentioned: Wilkins, Concilia, vol. 2, 381; The Knights of St John of Jerusalem in Scotland,

ed. I.B. Cowan, P.H.R. Mackay and A. Macquarrie (Scottish Historical Society, 4th series 19, Edinburgh, 1983), xviii–xix,

xxii; and in the records of a dispute in 1287 it was stated that certain dues owed by Maryculter to St Mary of Kelso

were to be paid at Balantrodoch: Registrum episcopatus Aberdonensis, 2 vols (Edinburgh, 1845), vol. 2, 288–93. It

would seem that Maryculter was dependent on Balantrodoch and that the Scottish master was in fact the preceptor

of Balantrodoch.

113

A. Soutou, ‘ Trois chartes occitanes du XIIIe sie`cle concernant les Hospitaliers de La Bastide-Pradines (Aveyron)’, Annales du

Midi, 79 (1967), 122–6, 144–53.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

163

Both orders appear to have adopted a fairly flexible approach in matters of administration

within a province or priory.

Central government

In the central government of the Temple, consisting of master, convent and chapter-general, weak-

nesses have been discerned in the Templar chapter general. It has been argued that, although Hospi-

taller chapters-general were ‘proper legislatures’, in the Temple legislation rested in the hands of the

master and convent: ‘chapters-general were legislatures only because they were present at them.’

Yet the Barcelona version of the Templar Customs includes a clause stating that ‘all these aforemen-

tioned things the master and the convent may add to or remove, and establish and keep just as seems

to them beneficial to the house. And furthermore it [. . .] should be done by the chapter general, for in

no other way [. . .] may the establishments of the house be removed.’

This could be interpreted to

signify that the consent of the chapter general was necessary only for the repealing of regulations,

although the wording is not free from ambiguity and can be taken in a different sense; but even

a limited interpretation would give the chapter general a role in legislative matters.

It has further been maintained that whereas the Hospital had a ‘properly representative chapter-

general’, the chapters-general of the Templars ‘were not representative, because the western grand

commanders [provincial masters] did not come to them’.

Representative government might be

regarded as desirable as an end in itself, irrespective of practical consequences, but it may be questioned

whether this was a widely-held view towards the end of the thirteenth century: although then and in

the early fourteenth century demands were made in various kingdoms for regular parliamentary

assemblies, to which certain issues should be submitted (as in England in Henry III’s and Edward II’s

reigns, and in Aragon in 1283), these demands were prompted by unpopular or unsuccessful royal

policies and were not of long-term significance. But representative government could also be seen as

having the practical advantage of making for effective rule. In this context doubts have been expressed

about the extent to which the central authorities of the Temple were in touch with events in western

provinces.

The degree of representation at Templar chapters-general needs therefore to be

considered.

The Barcelona version of the Templar Customs certainly states that ‘it is established in the Temple

that the commanders of the lands of Tripoli and Antioch should come each year to chapter where the

master and the convent are.’

Yet this merely implies that western provincial masters did not have to

come to the East every year. To have expected heads of western provinces to travel frequently to the

Holy Land or later to Cyprus would obviously have occasioned numerous prolonged absences from

their provinces, as journeys were affected not only by the difficulties and slowness of travel but also at

times by bouts of sickness. When the Aragonese provincial master Berenguer of San Justo went to the

Holy Land in 1286 his province was in the hands of a lieutenant from September of that year until May

1287: in that period no documents were issued in Berenguer’s name in Spain.

His successor,

Berenguer of Cardona, sailed for Cyprus in August 1300 and was not back in the peninsula until at least

114

C. Barquero Gon

˜ i, ‘Los Hospitalarios en el reino de Leo´n (siglos XII y XIII)’, El reino de Leo

´n en la alta edad media, 9 (1997),

356.

115

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 135, 139.

116

The Catalan rule of the Templars. A critical edition and English translation from Barcelona, Archivo de la Corona de Arago

´n, Cartas

reales, MS 3344, ed. J. Upton-Ward (Woodbridge, 2003), 38, art. 72.

117

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 140, suggests that there was little legislative activity in the Temple, but the early demise of the

order and the loss of its central archives make assessment difficult: there was no doubt a greater concern after the trial to

preserve title deeds than copies of Templar regulations. In the records of the trial reference was made on a number of occasions

to decrees issued in general chapters, but these have not survived: Michelet, Proce`s, vol. 1, 458; F.J.M. Raynouard, Monumens

historiques relatifs a

` la condemnation des chevaliers du Temple et a

` l’abolition de leur ordre (Paris, 1813), 282–3; Wilkins, Concilia,

vol. 2, 350–1; Se`ve and Chagny-Se`ve, Proce`s des Templiers d’Auvergne, 120.

118

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 135, 137.

119

Riley-Smith, ‘Structures’, 139.

120

Catalan rule, 22, art. 44.

121

Forey, Templars in the Corona de Arago

´n, 422.

A. Forey / Journal of Medieval History 35 (2009) 150–170

164

June 1301, while his journey to the East in 1306 began in late summer, and a lieutenant exercised

authority in the province until April 1307.

There was therefore a justification for the Templar ruling

that ‘commanders of western lands should not come to the East, unless they are ordered to do so by the

master and the chapter’: it took account of the practicalities of travel.

Even religious orders which

were based in the West did not insist on the attendance of abbots of more distant monasteries at every

chapter general.

Yet clearly western provincial masters of the Temple did at times travel out to the

East: in the later thirteenth century it was apparently the norm for them to be recalled every four

years.

As decisions about appointments to the post of provincial master were expected to be made in

the chapter-general,

and as within provinces commanders were expected to provide an account of

their houses at the provincial chapter, it would seem likely that provincial masters would be expected

usually to have their tenure confirmed or ended at a chapter-general.

The situation in the Temple may not in fact have been very different from that in the Hospital. The

heads of western priories could obviously not attend every Hospitaller general chapter, as at some

periods these met annually, and this may have been the expected frequency. In the later thirteenth

century heads of western priories were apparently obliged to go to the East every five years, and in