The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and

Nazi Berlin

by Christian Goeschel

On 21 June 1944, three years after Nazi Germany’s attack on the Soviet

Union, Heinrich Himmler, Reichsfu¨hrer SS and Chef der Deutschen Polizei

(Head of the SS and Chief of the German Police), gave a lecture to

Wehrmacht

generals. Himmler praised himself and the SS for cleansing

Germany of the Jews and insisted that there must never be another 1918

– referring to the German revolution of that year, allegedly brought about

by a coalition of Jews, Bolsheviks and criminals.

1

This speech came weeks

after the Allied landing in Normandy, when a German victory in the war

was increasingly unlikely and the Nazi regime had begun to escalate its

persecution of racial and social outsiders. Gangs of organized criminals,

the

so-called

Ringvereine

,

supposedly

dominated

by

Jews

and

Communists, were said to be subverting German society and undermining

the war effort. According to Himmler:

When a man was released from the penitentiary, an organization

was already available to him, organized by a comrade who had been

released from the penitentiary two or three months earlier. They would

agree then: we will do a big job because we must make some more money

again.

2

Himmler’s speech reinforced a powerful Nazi myth about the criminal

underworld, that it was part of a Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy which had

crippled Germany under the Weimar Republic until the Nazis destroyed it in

1933.

3

Concern with law and order was not exclusive to the Nazis, but to a

greater extent than many other modern regimes, perhaps,

4

they believed

that the repression of crime was central to their gaining and maintaining

popular support. Many Germans had been worrying about dramatically

rising crime rates since the end of the First World War. Eliminating crime

and thereby restoring the state’s authority was a Nazi priority, one of the

chief reasons why the Nazis appealed to large sections of German society, as

Detlev Peukert has shown. Even fifty years after the end of the Third Reich,

according to oral history interviews conducted by Eric Johnson and

Australian National University

Christian.Goeschel@anu.edu.au

History Workshop Journal Issue 75

Advance Access Publication 21 January 2013

doi:10.1093/hwj/dbs034

ß The Author 2013. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of History Workshop Journal, all rights reserved.

Karl-Heinz Reuband, many Germans still believed that whatever bad

things Hitler and the Nazis had done, they did at least clamp down on

criminality.

5

In this article, I dismantle and challenge the Nazi myth about crime

through a critical examination of the Berlin Ringvereine, which were central

in German debates on the criminal underworld. Little evidence has survived

on Ringvereine activity. Such records as there are, significantly, were put

into an archival collection on crimes and political offences committed during

the Weimar Republic, following a decree by the Reich Ministry of Justice

which conformed to the official Nazi view that the Weimar Republic was

undermined by crime and social decay.

6

With the exception of Patrick

Wagner’s work, the few existing accounts rely too much on anecdotal

rather than archival material and overlook the Nazi impact on the

Ringvereine

’s history. Furthermore, the existing studies agree that the

Nazis successfully repressed the Ringvereine upon coming to power.

7

In

reality, underworld syndicates continued to operate beyond the Nazi cap-

ture of power in 1933 – despite Nazi claims about the total elimination of

crime. There is no evidence that the Nazis ever arrested all Ringvereine

members; indeed, documents point to their survival beyond 1933.

Therefore the history of these underworld syndicates raises questions

about the limits of Nazi control of German everyday life, prompting reflec-

tions on the limits of the Nazi state’s monopoly of violence, the role of crime

in German political culture and continuities between the Weimar Republic

and the Third Reich.

A pub brawl that turned into a street fight on the cold night of 28

December 1928 brought German crime syndicates to public attention.

Between eleven o’clock and midnight, nine well-dressed men with top hats

entered a pub near Berlin’s Silesian Station, an area notorious for crime and

prostitution. Their leader ordered a round of drinks. People in the pub knew

him and his men: they were members of the Immertreu (‘Always Loyal’) and

Norden

(‘North’) crime syndicates. After ordering another round, the leader

of the men, Adolf Leib, known as Muscle-Adolf, approached Schulniess, a

young artisan from Hamburg in a group of carpenters employed on the

construction of the Berlin underground.

8

The atmosphere in the pub was extremely tense. A few hours previously,

Schulniess had knifed Emil Malchin, a Ringverein member. Muscle-Adolf,

keen to avoid an open confrontation with the Hamburg carpenters, wanted

to settle the case without involving the authorities. He demanded a large

sum from the carpenters to pay for Malchin’s hospital treatment. They

refused. Muscle-Adolf lost patience and grabbed Schulniess by his legs. A

pub brawl began. The carpenters, helped by bricklayers from the same con-

struction site, attacked the top-hatted men with their tools. Muscle-Adolf

and his men fought back, but were forced outside.

9

Schulniess was severely injured. Someone called the police who briefly

restored order. As soon as the police left, Muscle-Adolf’s men alerted other

The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and Nazi Berlin

59

Ringvereine

who arrived almost at once. A street battle erupted, involving

some 200 men. A bricklayer was beaten up so badly that he later died in

hospital. Eyewitnesses heard between twenty and thirty gunshots.

Neighbours rang the police again, but the men disappeared before they

arrived. A few days later, on New Year’s Eve 1928, in a heated political

atmosphere and after street fighting between Communists and Nazis, the

police arrested Muscle-Adolf and eight other members of the Immertreu

association. They admitted their involvement in the first fight but denied

killing the bricklayer. Members of the public, afraid of reprisals by the

syndicates, were extremely reluctant to testify to the police, as a frustrated

detective highlighted in his report.

10

For many police officials, their appar-

ent inability to crack down on the gangs reflected the weakness of the

Weimar state, overly concerned with legalistic quibbles, and led to demands

for tougher policing. The multi-volume police file ends with a note by a Nazi

legal official from 1938, noting that this was a case of historical importance

which must therefore be preserved for posterity.

11

The main features of the

Nazi myth of criminality were all present in this case: a weak police force

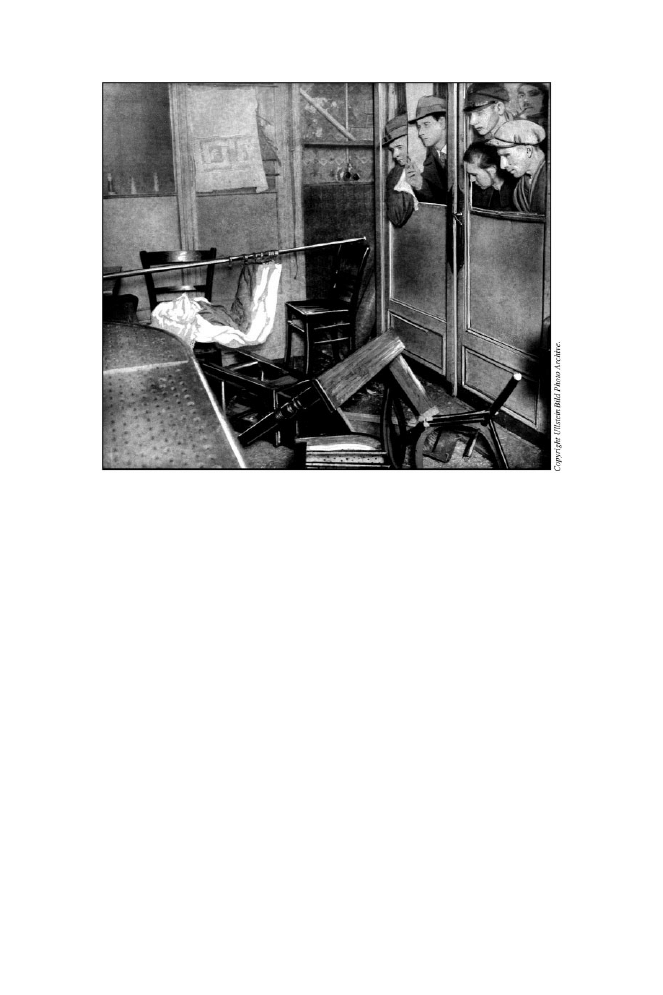

Fig. 1. ‘Pub Wrecked in Breslauer Strasse’, Photograph published in the tabloid Tempo, 31

December 1928. Berlin locals inspect the damage to a Friedrichshain bar after a fight on 28/29

December 1928 between members of the Immertreu (‘Always Loyal’) Ringverein (gang) and

carpenters from Hamburg employed on a local construction job.

History Workshop Journal

60

confronted by an omnipresent gang of dangerous criminals, undermining

Germany.

* * *

Who were these criminals? The Ringvereine were established in the late nine-

teenth century when there was a surge in clubs and associations in Germany.

Ex-convict associations set up by criminals as a respectable front, the ‘rings’

purported to be sporting or wrestling associations, hence the name

Ringvereine

(literally, ‘ring’ associations).

12

They constituted communities

for like-minded ex-convicts and members of the German underworld, long

marginalized, who aspired to a petty-bourgeois life and above all to respect-

ability.

13

Unlike the secretive Italian or American crime syndicates of

the same period, the Ringvereine were even officially registered under the

Reich Association Law. Members were forbidden by their statutes to

commit crimes. But in reality, like crime syndicates elsewhere, the Berlin

Ringvereine

were engaged in prostitution, the drug trade, the management of

the city’s night-life and the ‘offer’ of ‘protection’.

14

Their culture demanded

conformity to a meticulous code of respectable behaviour, and dispensation

of ‘justice’ to anyone who transgressed its rules. Control of a particular

territory was a key feature of any Ringverein.

15

Although only men were allowed to join, wives and girlfriends were an

indispensable part of their community, often providing income to members

through prostitution and waitressing.

16

The principle of mutual assistance

was central to the Ringvereine, as names such as Immertreu (‘Always Loyal’)

suggest. They helped members who were arrested and their families, for

example by finding jobs and hiring lawyers. Whenever a member died,

every associate had to attend his funeral without fail or risk expulsion,

reinforcing the Ringvereine’s insistence on loyalty and comradeship.

17

According to estimates of the Prussian Ministry of the Interior, around

seventy such associations, with approximately 5,000 members, existed in

Berlin in the early 1930s, before the Nazis came to power. Moreover,

Ringvereine

allegedly existed throughout Germany and mutually supported

one another. These assertions are hard to verify, and it must remain a pos-

sibility that the Prussian bureaucrats exaggerated them, feeding the fantasy

that omnipresent and powerful crime syndicates were undermining

Germany.

18

The purpose of the Ringvereine went far beyond professional criminal

activity. Their networks provided patronage, loyalty and friendship, offering

their members a distinctive, institutionalized and masculine sub-culture.

19

In

a way, the Ringvereine provided a parallel universe in which members lived,

worked and socialized, similar to other associations, including political

groups such as the Nazi and Communist parties. A respectable and legal

outward appearance was important to the Ringvereine. It reflected the torn

identity of the ex-criminals who were striving to be part of society.

20

At the

The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and Nazi Berlin

61

same time the Ringvereine, composed of criminals with an aspiration for

bourgeois status and public recognition, blurred the boundary between the

criminal underworld and the respectable public.

In the deprived working-class neighbourhoods of central Berlin the crime

syndicates created a culture of fear. Concern over rising crime rates had

increased since the German defeat of 1918.

21

Public discourse on the

Ringvereine

was contradictory. For some the members were ‘professional

criminals’, highly skilled men making their living through crime. For others

their criminality was ‘hereditary’, which meant of course that they were

incorrigible and should be locked up permanently. As recent studies have

emphasized, biologically determinist views of criminality (following

Lombroso) co-existed with interpretations of criminality as being caused

and exacerbated by environment.

22

Many commentators linked the

Ringvereine

to the alleged weakness of the Weimar state. In the late 1920s

it was commonly held both by experts on ‘the criminal’ and by public opin-

ion that criminals were undetectable and therefore particularly dangerous

and subversive.

23

Newspapers, always interested in crime stories,

24

carried detailed reports

of the December 1928 brawl described above and the subsequent trial of

Ringverein

members. The liberal Vossische Zeitung, for instance, ran a long

report on ‘the battle of the crooks at the Silesian station’,

25

and compared

the Ringvereine to the romanticized underworld of The Threepenny Opera,

the hit of the 1928 theatre season, by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, which

highlighted the Weimar obsession with crime and the seemingly fluid bound-

aries between respectable society and the criminal underworld.

26

Other

voices, particularly from the right, were more alarmist. Der Montag,

owned by the far-right press tsar Alfred Hugenberg, ascribed the emergence

of organized crime gangs to the increasing influence of American culture

and the Weimar Republic’s purportedly degenerate atmosphere.

27

Der

Angriff

, Berlin’s Nazi newspaper, edited by Joseph Goebbels (Gauleiter of

Berlin and a master propagandist in the making), carried an expose´ of the

shocking extent of organized crime in Berlin and demanded tough measures

against ‘insolent gangs of pimps and criminals’ who were allegedly operating

across the whole of Berlin, not only in the poor East, but also in the more

prosperous West. The aim was to attract the support of middle-class voters

for the Nazis, still a marginal party. Goebbels insisted that the Nazis would

eradicate criminality once and for all.

28

However it was not only the Nazis who made the eradication of crime

a major political issue. For other parties too, the desire for a strong and

stable state went with concern about law and order. Vorwa¨rts, the daily

paper of the Social Democrats, who were in control of Prussia and its

police, drew an alarmist picture of the Ringvereine and insisted on New

Year’s Eve 1928 that ‘the police must take drastic measures’.

29

Such reports

reinforced a general perception of the Ringvereine as dangerous crime net-

works. By hammering home stories about the omnipresence of the

History Workshop Journal

62

dangerous criminal underworld and police inability to crack down on them,

newspapers of diverse political leanings helped to undermine the Weimar

Republic’s legitimacy.

In the wake of the Immertreu street fight, in early January 1929, Berlin’s

Police President dissolved the Ringvereine on the basis of the Reich

Association Law, but the Ringvereine took legal action and were soon rein-

stated. Muscle-Adolf and his accomplices went on trial in February 1929

before the Moabit Criminal Court, defended by Berlin’s most prominent

lawyers, Erich Frey and Max Alsberg.

30

In a letter to the state prosecutor,

Alsberg denied that Immertreu was a crime syndicate and reminded him

that the police maintained close contacts with Immertreu, while admitting

that some members were ex-convicts. He insisted that the Hamburg carpen-

ters were to blame for the fight, as they had attacked Malchin in the first

place. Alsberg named at least eleven witnesses who could testify in favour of

Muscle-Adolf and his associates, along with thirty-six other men and women

who would confirm that the Hamburg carpenters had on several previous

occasions breached the peace. Clearly, these witnesses were either linked to

the Ringvereine or had been coerced by them to testify in their favour. It was

through fear and intimidation on the one hand, and a culture of mutual

support on the other, that the Ringvereine were able to mobilize so many

witnesses.

31

Like other modern mafia organizations, the Ringvereine also

bribed and bullied prosecution witnesses. In the end, the trial was a major

embarrassment for the court and the judiciary, and a triumph for the

Ringvereine

. Neither the man who had injured Schulniess nor the killer of

the bricklayer was ever found. Muscle-Adolf received a very lenient sen-

tence of ten months in gaol for breach of the peace, while another man

got away with five months in prison. The remaining defendants were

acquitted.

32

Despite all the media attention, the 1928–29 incidents were in reality very

local, confined to a few working-class blocks of Berlin. The mythical sig-

nificance of the Ringvereine, constructed by the press, political parties and

the Ringvereine themselves, far outweighed their actual importance. In many

ways, clubs like Norden or Immertreu were variants of ordinary associational

life, more brutal but not greater in influence than other organizations. Here

were groups of ex-convicts keen to be integrated in society, but at the same

time determined to keep their distinctive sub-culture. But not everyone

shared this view. The 1928–29 incidents caused resentment among some

members of the public and some of the police who believed that the weak

and degenerate Weimar ‘system’ supported professional criminals. Police

attitudes towards the Ringvereine were divided. While some police officers

saw Ringvereine members as dangerous professional criminals, many

co-operated with them to keep red-light districts under control. This re-

flected divisions in criminological discourses and practices relating to orga-

nized crime. Some crime officers were resigned to the existence of the

The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and Nazi Berlin

63

Ringvereine

, recognizing that in certain poor neighbourhoods of East Berlin

the state was unable to maintain its monopoly of violence,

33

and the

Ringvereine

’s practice of restraining tensions among themselves was of as-

sistance to the police. Furthermore, since the Ringvereine were all officially

registered, the police were confident that they could easily identify and

locate their members.

34

Links between the police and the Ringvereine were so close that some

officials, including Ernst Gennat, the famous chief of the Berlin criminal

police’s homicide squad, even attended annual Ringverein parties, lavish

affairs with expensive food and champagne.

35

Bernhard Weiss, deputy presi-

dent of the Berlin police (viciously attacked by the Nazis as a Jew), also

attended one of the parties. The ring members attended in tails, their girl-

friends or wives in ball gowns. In a letter to Max Alsberg of 29 March 1929,

weeks after the conclusion of the trial of Muscle-Adolf and his confederates,

Weiss asked Alsberg to ensure that the Immertreu syndicate would keep a

low profile until the media attention to the Ringvereine caused by the trial

had subsided. For Weiss too, the Ringvereine were a necessary evil, main-

taining order in neighbourhoods of Berlin where the police were ineffective.

Previously, Alsberg had been attacked by the Berlin Bar Association for

going to a Ringvereine party, together with Robert Heindl, a retired police

official and author of The Professional Criminal, an influential study in

1926.

36

Worried about rumours that they had accepted bribes, both

Heindl and Alsberg insisted that they had paid for their meals and drinks

out of their own pockets.

37

Such stories of police relations with the gangs were the tip of an iceberg.

For Alsberg and Heindl and many others, the rings were fascinating and

somewhat disreputable, but not illegal or threatening. It was not clear that

their members were really ‘professional criminals’ in Heindl’s sense. In his

study, written amidst initiatives to reform the German penal code, Heindl

had drawn up a typology of dangerous ‘professional criminals’, people who

had not drifted into crime by chance but who were pursuing crime for a

living. For Heindl, there were around 1,000 ‘professional criminals’ in

Germany who were so dangerous that they ought to be held in permanent

in ‘preventive detention’. Other commentators went much further and in-

sisted that there were several thousand dangerous criminals, including petty

thieves, who had to be detained forever.

38

As long as the Ringvereine stayed in the realms of their relative obscurity

and marginality, the police and the public tolerated them. But as soon as

they stepped out of their neighbourhoods, right-wing commentators ex-

pressed moral outrage, reinforcing middle-class fears that top-hatted crim-

inals, aspiring to the trappings of bourgeois life, were taking over Berlin.

39

When the Ringvereine threw expensive and elegant parties on Potsdamer

Platz in central Berlin, right-wing commentators were furious. In a March

1929 speech before the Prussian Diet, prompted at least partly by the 1928–9

History Workshop Journal

64

incident involving Muscle-Adolf, Franz Alexander Kaufmann, deputy of the

national-conservative DNVP, thundered:

But never have these professional criminals been so brazen and shame-

less . . . and never have these criminals dared to prostitute themselves in

huge public celebrations and to show off what they can afford. There

have been occasions where 4,000 convicted delinquents got together, in

dinner jackets, patent leather shoes, probably also with top hats . . . One

really has to say that it is time to take drastic action.

40

The Ringvereine’s adoption of bourgeois dress and their claiming of bour-

geois spaces seemed subversive to many at the time, although perhaps the

criminals’ intention was to hide their criminal identities. At the same time,

the romanticized image of organized crime as a self-policing underworld

with ancient rules and rituals resonated in Weimar culture. The

Ringvereine

, keen to portray themselves as honest and decent, but also fear-

some, knew how important media representation was. Dr Arthur

Landsberger, author of a number of best-selling crime novels, is said to

have advised the Ringvereine in their dealings with the press. Landsberger

maintained good relations with the Ringvereine and received a monthly hon-

orarium from the famous Ullstein publishing house for his short reports on

the underworld in the popular tabloid B.Z. am Mittag.

41

That organized criminals understood the workings of the media and

wished to influence their press image is fascinating, but at a time when

political manipulation of the media was on the rise it is not altogether

surprising. In 1929, coinciding with the trial of Muscle-Adolf and his ac-

complices, Landsberger published a book in which he offered an alternative

perspective on the Ringvereine. He drew on the prominence of American

crime syndicates to downplay the extent of the Ringvereine’s activities. After

a detailed account of the battle between Immertreu and the Hamburg car-

penters he concluded: ‘Within less than half an hour the act of private justice

and private enforcement was done’.

42

For Landsberger the Ringvereine were

in no way different from other clubs, such as the exclusive Wannsee Golf

Club. To defuse public concerns he even reprinted Immertreu’s code of con-

duct, which gave the Ringvereine an aura of bourgeois respectability: each

new member had to attend five meetings without fail and on time, or be

fined three marks. Penalties were also imposed on those who were late

for meetings, who appeared drunk in public or who lost their membership

pin, the visual marker of belonging to the syndicate. Failure to attend a

member’s funeral meant expulsion. Landsberger portrayed the syndicates

as decent, honourable, petty-bourgeois associations, designed to rehabili-

tate ex-convicts. Around a dozen such clubs existed in Berlin, he claimed,

and they were linked to similar associations throughout Germany.

Landsberger finished his text by declaring the political neutrality of the

rings, to refute the right-wing charge that they were Communist fronts.

The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and Nazi Berlin

65

He declared: ‘Above all, the Ringvereine are apolitical. They don’t give a toss

whether Hitler or Tha¨lmann, Seeckt or Scheidemann want to declare dicta-

torship. They have something better to do: to cultivate the life of the

association.’

43

To present themselves as harmless, self-governing clubs of ex-criminals,

as in this account, was part of the Ringvereine’s successful media strategy.

The view of the Ringvereine as self-policing crime syndicates, maintaining

law and order instead of the inefficient police, also suited them. This was

immortalized on celluloid in Fritz Lang’s 1931 film M, released a year after

the Nazis’ electoral breakthrough in the September 1930 Reichstag elections.

In the climax of the film organized criminals put the child murderer Beckert

(played by Peter Lorre) on trial in a kangaroo court, surrounded by a public

which demands his death. The gangsters are led by the charismatic

Schra¨nker (played by Gustaf Gru¨ndgens), wearing the hat and leather

gloves which many viewers would have associated with the Ringvereine.

The police, personified by a fat inspector, are depicted as unable to deal

with the child murderer, in line with the widespread sentiment that the

Weimar state failed to maintain law and order. What is more,

Muscle-Adolf is said to have advised Lang on the inner workings of orga-

nized crime gangs, for a substantial sum of money, and Gru¨ndgens, later one

of the Third Reich’s leading actors, was reportedly an honorary member of a

Ringverein

, reflecting bohemian fascination with organized crime.

44

If true,

here was more evidence of Ringvereine concern with their public image.

Lang’s film was only a modest success at the box office, but as a convincing

critique of the Weimar legal system it prompted political commentary. The

Nazis, including Joseph Goebbels, welcomed the film’s message that the

Weimar state had failed and that crime would best be eradicated through

drastic extra-legal measures. Through their media presence, the Ringvereine

became shorthand for what had gone amiss in Weimar Germany. After the

1929 trial, however, they gradually disappeared from the front pages, prob-

ably because they decided to keep a low profile. Yet in the German imagin-

ary of crime, they remained present, not least thanks to M.

45

The Ringvereine continued to control their territories and defend them

against any intruders, amidst rising mass unemployment and the gradual

disintegration of the Weimar Republic. A 1931 incident, also taken from

the set of case files archived by Nazi legal officials in the late 1930s, illustrates

this point. In the early hours of 21 March, the police were called to Willi W.’s

pub in East Berlin’s Markusstrasse. Minutes after W. had called last orders,

two gunmen entered the pub, shouting ‘Hands Up!’. They shot the waiter

Paul K. several times. Neighbours alerted the police. K. was rushed to hos-

pital in an ambulance. He survived.

46

Before the police arrived all traces of the

fight, including bullets, had been removed. Next morning the police interro-

gated several witnesses, including the landlord, his wife and some customers.

No one identified the gunmen. The crime officers were sure that the witnesses

were deliberately withholding vital information, whether because they were

History Workshop Journal

66

connected in one way or another to the Ringvereine or because they feared

reprisals. The police soon established that the victim K. was a pimp with a

long criminal record and a member of the Friedrichstadt syndicate, officially

registered as a men’s choir. The pub was known as a regular gathering place of

the Friedrichshain syndicate, allied with Friedrichstadt. According to a con-

versation between two prostitutes overheard by the police, K. had been shot

by members of the Felsenfest (‘Rock-Solid’) syndicate, itself officially regis-

tered as a lottery association. The police investigations confirmed that the

incident

had

resulted

from

a

dispute

between

Friedrichstadt

and

Friedrichshain

syndicates on the one hand and their rivals, the Felsenfest

gang, on the other. The gunmen were after Willy S., one of the bosses of

Friedrichshain

, and had shot K. by accident. Although the police questioned

five suspects, all related to the Ringvereine, they failed to identify the gunmen.

Their final report noted that Felsenfest had paid K. several hundred

Reichsmark in compensation to settle the case without involving the autho-

rities. Because of the rings’ culture of silence vis-a`-vis the authorities – omerta`,

the honourable code of silence – and their practice of silencing witnesses, the

police had little choice but to close the case.

47

Around this time the Nazis were emerging as Germany’s largest political

party. Many members of the Berlin criminal police joined the party in the

hope that the Nazis would give them additional powers to suppress crime

and the Ringvereine.

48

Creeping Nazification of the police reinforced the

perception of the Ringvereine as degenerate professional criminals who

were associated with the Communists. When Ali Ho¨hler shot the Nazi ac-

tivist Horst Wessel in February 1930, Goebbels’s propaganda celebrated

Wessel as a martyr and stressed Ho¨hler’s purported connections to the

Ringvereine

, code for the criminal underworld.

49

Nazi propaganda also

highlighted

alleged

connections

between

the

Ringvereine

and

the

Communists. A Nazi book memorialized the storm-trooper Hans

Maikowski, killed in January 1933 allegedly by Communists, turning him

into a martyr who had followed in Wessel’s footsteps as a spearhead of the

Nazi fight against Communism in Berlin. The book complained about the

alliance between Communists and the Treue Freunde (‘Loyal Friends’) syn-

dicate in a working-class district in Berlin. The authors asked the rhetorical

question: ‘What other political conviction can a criminal have but a

Communist one?’ Here was the Nazi idea of a pact between Communists

and criminals.

50

In reality, matters were more complex. One case from 1932, when the

Nazis and the Left fought each other in a kind of civil war in some of

Berlin’s working-class neighbourhoods, is emblematic of the political pos-

itioning of the Ringvereine and the emergence of parallel universes in the

fraying atmosphere of late Weimar Berlin. Communists, Nazis, Socialists

and other groups such as the Ringvereine all demonstrated the increasing

polarization of German society and offered their members a distinctive

sub-culture. Increasingly, political groups contested the control of territories

The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and Nazi Berlin

67

in Berlin. This inevitably led to conflicts with the Ringvereine. Some

Ringvereine

sided with the Communists, while others attacked them, as in

a raid by one crime syndicate on a Communist meeting-place in March 1931.

In general, territorial control was more important for the Ringvereine than

politics.

51

On the night of 3 August 1932 the Berlin criminal police filed a report

about a ‘political murder’ in the Wedding working-class district, following a

street fight involving Communists and Nazis. This file too ended up in the

Nazi collection of Weimar-era criminal incidents as it seemed to suggest

links between the Communists and the Ringvereine against the Nazis.

52

From inside the Alte Linde pub, a known haunt of Communists and more

recently of the Loge Norden (‘Northern Lodge’), someone had fired a gun,

killing Fritz S., a Nazi party member aged thirty-seven. On hearing the

gunshots, the publican closed the pub’s shutters. He refused to open them

when the police arrived on the scene. With the help of enraged Nazis they

forced them open and searched the premises and all those inside. Two men

were found hiding in the basement. They were arrested, along with seventeen

other men and one woman. The street fight must have been vicious: the

police seized several knives, two small-calibre bullets and a bloodied Nazi

party armband. The Berlin homicide squad, famous throughout Germany

for its investigative work, took over the case.

53

Among the suspects were Willi H. and Arthur H., each with previous

convictions. Willi H., aged thirty-seven, claimed to be running a small busi-

ness. His criminal record suggests that it was a shady one: he had been

sentenced in 1929 for handling stolen goods (Hehlerei). Arthur H., an un-

employed locksmith aged thirty-four with no registered domicile, had no

fewer than ten convictions, for dealing in stolen goods and for grievous

bodily harm.

54

Arthur H. denied shooting the Nazi or being a

Communist, but admitted to having joined the Loge Norden in 1930. He

claimed that Willi H. had confessed to him while they were hiding in the

basement that he, Willi, had fired the gun.

55

Willi H., also a member of the Loge Norden, told the police his version of

events. He had been swimming in a lake on Berlin’s outskirts on 2 August

and went to the pub late that night for the Loge Norden’s weekly meeting.

Suddenly, someone shouted ‘The Nazis are here and fighting with the

Communists’. Willi H. and his mates all agreed that ‘this brawl is political;

it is none of our business’. According to Willi H., Arthur H. prompted the

pub’s landlord to lower the shutters. When he heard a gunshot, Willi H.

fired his gun, allegedly just for self-defence. He then hid in the pub basement

with Arthur H., who told him to throw away his gun. Willi H. wrapped his

gun, along with twelve bullets, in a bloodied copy of the Communist tabloid

Berlin am Morgen

– a detail suggesting that at least some in this ring’s

regular pub read a Communist paper and probably had some Communist

sympathies.

56

History Workshop Journal

68

Other members of the Loge Norden (who had clearly co-ordinated their

testimonies) confirmed Willi H.’s story. Willi H. was innocent. During the

interrogation of Franz S., also a member of the Loge Norden, the police

discovered the real background to this incident. While in the neighbourhood

the day before the fight, Franz S. had heard Nazis bullying and hitting

Communists outside the Alte Linde pub. S. and his mates were furious as

they claimed to be in charge of the streets around the Alte Linde. The fight

was thus about territorial control and not primarily party politics.

57

However, as this case shows, the decision of the Ringvereine to stop the

Nazis advancing in Ringverein-controlled territories became politically

loaded. Such events contributed to the Nazi myth about the Ringvereine

as dangerous Communist fronts. Even before the Nazis came to power,

the perceived association of the Ringvereine with Communism was made a

pretext for a police clampdown. When the right-wing Papen government

illegally seized control of Prussia and the Prussian police in July 1932, the

criminal police began to take a more aggressive position against the

Ringvereine

. Several raids in the autumn of 1932 led to the temporary arrests

of up to one hundred Ringverein members, but they were very quickly

released, for lack of evidence.

58

Despite its illegal actions, the Papen gov-

ernment thus still respected the need for evidence in criminal cases. Only a

few months later, the government’s attitude would change dramatically.

* * *

Almost as soon as they came to power, the Nazis enacted draconian legis-

lation against ‘habitual criminals’, often but not always people with a string

of convictions for relatively minor offences. In the wake of a Prussian

Ministry of the Interior decree on the ‘application of preventive police de-

tention of professional criminals’ (Anwendung der vorbeugenden Polizeihaft

gegen Berufsverbrecher

), issued in November 1933, the criminal police, in

co-operation with the judiciary and the SS, arrested many Ringvereine mem-

bers, often holding them in the concentration camps set up by the regime

since the spring of 1933. The Nazi crackdown was facilitated by the police

having access to the Ringvereine’s membership files, so all the police had to

do was to find and arrest those listed as members. The crackdown climaxed

in raids against thousands of alleged ‘habitual criminals’ in 1937, as Nazi

terror increasingly targeted social and racial outsiders.

59

Willi H., mentioned above, received a tough prison sentence in April 1934

from an increasingly Nazified judiciary.

60

He was sentenced to fifteen years in

a penitentiary for manslaughter and attempted manslaughter, although it

could not be proved that he had planned an attack on the Nazis. According

to the records of the Berlin jury court (Schwurgericht) Willi H., like most

people arrested by the Nazis as ‘habitual criminals’, was a typical petty

crook. Only schooled until second grade, he had worked as an errand boy

before joining the German Navy during the war where he saw enemy action in

The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and Nazi Berlin

69

the Battle of the Skagerrak in 1916. After the war, he failed in various jobs and

eventually started selling soap in street markets. He soon drifted into petty

crime and began to handle stolen goods. This activity brought him into con-

tact with the Loge Norden. For the court, because Willi H. had been a member

of the Rote Hilfe (‘Red Aid’), a Communist charity, he was a Communist

criminal. This prompted the tougher sentence. In fact, the court’s main con-

cern was to denounce Willi H. as a Communist, rather than to uncover the

Loge Norden’s

intricate networks of thieves and fences. His lawyer appealed

but the Leipzig Reich Court (Reichsgericht) rejected the appeal.

61

Willi H. was

held in various penitentiaries, initially in Brandenburg-Go¨rden. From here he

was transferred to one of the penal camps run by the Reich Ministry of

Justice, in the Emsland near the Dutch border, before being moved to the

Untermassfeld prison in Thuringia. From here, along with thousands of

others identified as habitual criminals, he was transferred in April 1943 to

the Buchenwald concentration camp.

62

At this point his file ends. He may well

have died in the camp, as did many ‘habitual criminals’.

63

The myth of having dealt with organized crime was a central aspect of

Nazi propaganda. In September 1933, months after Hitler’s appointment as

Reich Chancellor, Hermann Go¨ring, Prussian Minister President and in

charge of the Prussian police, gave a speech praising the Third Reich’s re-

pression of crime. The new regime, he insisted, detained ‘enemies of the

state’ in concentration camps. (In fact, up to a total of 200,000 prisoners,

mostly Communists and Socialists, alongside some purported criminals,

were held in the improvised early concentration camps in 1933.)

64

Go¨ring

also emphasized that the Nazis were restoring law and order, a key issue for

the Nazis and many of their supporters:

The criminal police force has started a ruthless campaign against profes-

sional criminals and has had some stunning successes even with previous

crimes whose clarification was not possible or desirable for previous

governments. . . . The Ringvereine must not appear in public any longer

and will be further repressed until the underworld is annihilated. The

number of grave, sensationalist and dangerous crimes has fallen extraor-

dinarily, or they have ceased altogether, so that safety and order rule

again in this area, as a clear success of National Socialism.

65

Go¨ring’s claims about the Nazi regime’s eradication of crime and the result-

ing decline in crime rates were meant to distract from the inconvenient

reality that compared to levels before 1932 – the climax of the Great

Depression with its very high incidence of property-related offences –

crime rates were still fairly high in the Third Reich.

66

Moreover, the Third

Reich’s official crime rates did not include state-sponsored political crime,

which with the wave of terror during the Nazi consolidation of power in

1933 had reached unprecedented levels. Still, there was a widespread popu-

lar perception during the Third Reich, constantly endorsed by Nazi

History Workshop Journal

70

propaganda, that crime rates were declining sharply because of tough

policing. Go¨ring’s admission that the Ringvereine had not yet been ‘annihi-

lated’ was significant and indicated that some Germans were still sceptical of

Nazi rhetoric about the Third Reich’s successful clampdown on crime.

German society in 1933 was deeply polarized between Nazi supporters

and those who opposed the new regime or remained reserved towards it,

especially the working class. Massive terror against the Left was accompa-

nied by propaganda about the elimination of crime (and the Ringvereine).

Go¨ring warned that the regime could not afford to be complacent because

the Ringvereine were still a threat, despite all previous ‘ruthless campaigns’.

The Nazi myth was designed to appeal to large sections of German society,

since it was – like Nazi rhetoric about the revision of the Versailles Treaty

perhaps – a seemingly uncontroversial issue for many Germans, which legit-

imized Nazi rule. Indeed, this myth became extremely powerful within

German society and was a major reason why ordinary people supported

the Nazi regime.

67

Even after the consolidation of Nazi rule, the Ringvereine featured prom-

inently in political and academic discourses. In 1936, the criminologist Max

Hagemann published an article on organized criminals for the highly influ-

ential Dictionary of Criminology. For him, tough Nazi policing had des-

troyed the Ringvereine once and for all.

68

Kurt Daluege, a police general

and chief of the Order Police (Chef der Ordnungspolizei), railed against the

Weimar Republic’s weakness in dealing with organized crime in a 1936

book. He insisted that the ‘old state tolerated that . . . criminals associated

with each other in a ‘‘Reich Association of Ex-Convicts’’ ’. What infuriated

Daluege was that the Weimar police forces had allegedly repressed ‘hun-

dreds and hundreds of Nazi rallies’, but no gatherings of the Ringvereine.

For Daluege the brutal crackdown on the Ringvereine by the Nazis in 1933

was completely justified as it had deterred criminals from continuing with

their activities.

69

It is true that the police attacked the Ringvereine, both using the Reich

President’s Emergency Degree of 28 February 1933 (the Reichstag Fire

Decree), and also threatening extra-legal violence against them. Most

Ringvereine

grudgingly accepted their dissolution amidst a massive cam-

paign of Nazi terror against anyone standing in the way of the new

regime in the spring of 1933, and there were only a few arrests. But some

associations did not give in so easily. These organized a concert for 2,000

people in June 1933, in the Saalbau Friedrichshain, a popular entertainment

venue in East Berlin. When the police threatened to arrest the owner of the

premises, and the musicians, the Ringvereine cancelled the event and al-

legedly even refunded the tickets. Daluege claimed that only thirty people

had shown up, most of them drunk, and concluded triumphantly that this

event had been the last public appearance of the Ringvereine, before praising

the Third Reich’s tough repression of professional and habitual criminals.

70

Along the same lines, in 1941 Arthur Nebe, the high-ranking SS officer

The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and Nazi Berlin

71

effectively in charge of the criminal police, expressed retrospective outrage at

the riches previously accumulated by the Ringvereine:

Thus it was in the end no surprise that those convicted because of crim-

inal or dishonourable activities gathered in a ‘Reich Association of

Ex-Convicts’ or that in many big cities, underworld associations mush-

roomed. Even though these ring associations were disguised as social or

lottery clubs, as leisure or sports clubs, their entire membership was

composed of criminals with heavy sentences who got together to

defend their interests. Over and over again they committed crimes and

stole sums which allowed them a certain luxury. They wore gold club pins

or gold rings with the club’s emblem. At festivities or funerals they

showed off richly embroidered banners and flags made of heavy silk

and their lawyers appeared as honorary guests. Truly a symbol of the

decline of mores!

Nebe invoked the riches amassed by the Ringvereine to appeal to ‘healthy

public sentiment’ (der gesunde Instinkt des Volkes), a Nazi concept used to

justify tough measures that breached the legal code. He also introduced

racist overtones when he triumphantly concluded after Hitler’s appointment

as Reich Chancellor that the ‘national comrade could breathe again and

describe those dark figures as what they were: as subhuman beings

(Untermenschen) and a pack of criminals’.

71

These accounts of the Ringvereine were emblematic of the Nazi myth of

crime. Emphasis on the threat posed by the Ringvereine was linked to the

claim that these dangerous gangs had been eliminated by the regime. Since

organized crime threatened the safety of Germans, tough methods, as im-

plemented by the Nazis, were absolutely necessary. Stress on seemingly dan-

gerous groups such as the Ringvereine was used to legitimize the existence

and the brutal methods of the Nazi regime.

Nazi claims about the repression of the criminal underworld are hard to

verify, as very little evidence has survived, but what is clear is that the Nazis

did not fully destroy the informal networks of the Ringvereine. Despite

tough police measures, some Ringvereine were still active in Berlin in

1935, two years after the Nazi seizure of power, according to a report

filed in the news-sheet of the Prussian State Criminal Office. The report

subscribed to the Nazi myth of the Ringvereine and was widely circulated

among criminal police officers throughout Prussia. It highlighted the case of

Rosenthaler Vorstadt

(‘Rosenthal Suburb’), a Ringverein officially dissolved

in 1933. Ex-members were forging coins on a grand scale before distributing

them in pubs. Nobody dared to report the counterfeiters to the police. The

Ringvereine

still had a fearsome reputation in their former strongholds, and

the culture of settling disputes internally continued beyond 1933. Under

Nazi repression members of the Ringvereine were still loyal to each other,

helping each other in the face of imminent arrest, as a frustrated police

History Workshop Journal

72

official noted. Networks thus remained largely intact. The Ringvereine con-

tinued to operate with the same structure and organization as before 1933,

although they now had to hide their activities. On 17 September 1935 the

police carried out a raid and detained twenty-six men, all of them

ex-members of Rosenthaler Vorstadt. The police arrested them separately

to prevent them from co-ordinating their testimonies. Fourteen were kept in

custody, but the rest had to be released because of a lack of evidence against

them. For the police, the success of the Rosenthaler Vorstadt syndicate well

after the Nazi seizure of power was unacceptable as it showed that the Nazi

state was unable to control Berlin. In a brief historical sketch of the

Ringvereine

, appended to the report, the police explained that syndicate’s

success in resisting repression by reference to its distinctive culture and its

excellent relations with other Ringvereine. The report ended on a rather

gloomy note and concluded that the Ringvereine were still dangerous and

a force to be reckoned with. Whether the report exaggerated the

Ringvereine’s

activities to justify even tougher police measures is unclear,

but must remain a possibility.

72

There are no official statistics for the extent of organized crime under the

Nazis, but a few spectacular cases challenge the regime’s rhetoric of order

established. One case of Ringverein activity beyond 1933 kept the Berlin

judicial and police authorities so busy that it filled almost a hundred files.

This concerned a gang of highly professional burglars, with at least thirty

members allegedly connected to the Ringvereine, who systematically stole

goods worth several hundred thousand Reichsmark from expensive shops,

and then sold them via middlemen.

73

According to a 1937 court verdict, the gang operated from 1926 until

1935 and carried out at least 200 thefts. At the centre of the gang was H., a

trained baker. Because of the aggressive police interrogations of H. and his

mates the files have to be interpreted with care, even though it is clear that

H. and his comrades did commit a string of burglaries and were engaged in a

highly sophisticated criminal network. H. had volunteered for service in the

First World War and was wounded in action. After his demobilization he

joined a paramilitary organization fighting Bolshevism in the Baltic States

before he moved to Berlin in 1920, where he failed to find a job. He then

decided to start a new life in Argentina (though he never got there). To

finance his passage he burgled his uncle’s watch shop, his first crime. At

the same time, he changed his name. He then found work as a waiter and

porter in a nightclub in the impoverished Bu¨lowstrasse district in central

Berlin, where he got in touch with pimps and thieves, his future accomplices,

and most likely with several Ringvereine. Sentenced to several spells in

prison throughout the 1920s, he committed his first large-scale burglary in

1926 after he met Oskar W., who was German-Jewish. Together with W.

and another man, H. burgled a hosiery shop. They sold the loot for 300

Reichsmark. After their first job, H. and his mates grew ever more confident

in their ability to go undetected and unpunished, and continued with ever

The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and Nazi Berlin

73

more brazen burglaries of luxury shops. Briefly under arrest in January

1933, when Hitler became Reich Chancellor, H. was released in June

1933. He tried to make a living selling fabric patterns, but soon returned

to his old trade of burglary until his arrest in October 1934, still under his

fake identity. He only confessed that his correct name was H. during his first

interrogation in late October 1934, probably while threatened by the police.

H. was given a nine-year sentence in a penitentiary.

74

Because he was Jewish,

his accomplice Oskar W. received an even tougher sentence. For the court, it

was clear that W. belonged to a network of Jewish organized criminals who,

as part of a Jewish conspiracy to undermine German society, had committed

insurance fraud. The criminal police even issued a press release in August

1935 claiming that there was a Jewish association specializing in such bur-

glaries. W. was also accused of burgling a shop in 1935 at the request of a

Jewish wool-trader who was facing difficult times because of the intensified

Nazi drive to rid the German economy of Jews. Allegedly, the wool trader

had tried to defraud his insurance company of the enormous sum of 70,000

Reichsmark; yet to no avail, as a night-porter caught the burglars

red-handed.

75

W. was sentenced to fifteen years in a penitentiary with subsequent con-

finement in a prison. But he fled to Czechoslovakia, where he was beyond

the reach of the German authorities. There he was arrested for yet another

burglary, and spent four years in prison in Prague. At the request of the

German authorities the Czechoslovaks deported him to Germany on 1

March 1937 and at the border he was arrested immediately by the

German police. W. then applied to serve his sentence in Czechoslovakia

and in late December 1938 the German authorities, rather incredibly, sent

him back to Prague to do his time. In March 1939, when after the annex-

ation of the Sudetenland Germany seized the remaining Czech lands, W.

again fell under the power of the Nazi judiciary.

76

He was sent to the

Waldheim penitentiary in Saxony where he was expected to serve his various

sentences until 1956. We do not know whether W. survived the war. Given

the relentless judicial persecution of Jewish prisoners, who from 1942 were

handed over to the police for ‘annihilation through labour’, he probably

died in a Nazi camp.

77

Two conclusions can be drawn from this admittedly scant evidence. The

Nazis had not managed to repress the Ringvereine completely in the mid

1930s. For the late 1930s and the war years there is no documentary evi-

dence of Ringverein activity. The Nazis, gearing up for war, introduced new

draconian police measures which had a devastating impact on the

Ringvereine

, especially the March 1937 mass arrests of some 2,000

ex-convicts and alleged criminals and the December 1937 introduction of

preventive police custody (polizeiliche Vorbeugehaft) in concentration camps

for suspected criminals.

78

The lack of documentary evidence for Ringverein

activity beyond the mid 1930s allows another explanation too: Nazi officials

History Workshop Journal

74

believed their own propaganda that organized crime had been crushed; thus

there was no more reason to police and document it.

79

* * *

Muscle-Adolf, protagonist of the central story in this article, resurfaces in a

post-war police file. Having survived the Third Reich’s terror, in June 1946

he was picked up for illegal gambling, in a pub in north Berlin. The police

confiscated the staggering sum of more than 11,000 Reichsmark and five

decks of cards, alongside precious coffee beans, half a pound of salmon and

a tin of caviar. Muscle-Adolf was involved in black-marketeering, an illegal

activity though almost acceptable in the context of bombed-out Berlin and

shortages. (There is no evidence, though, that the Ringvereine ran the black

market.)

80

The omerta` of the Ringvereine still functioned: nobody would

testify against Muscle-Adolf and the police had to close the case.

81

Despite their claims, the Nazis had failed to wipe out the Ringvereine,

which continued to operate through the political ruptures of 1933 and

1945 as their networks and rituals of belonging held their members together.

The history of the Ringvereine reminds us of the continuity of German

everyday life beyond the political caesura of 1933.

82

After 1933, Nazi repression of the Ringvereine was extremely tough, but

not all members were arrested and some continued with their illegal activ-

ities, a fact that disturbed Nazi officials as it revealed the limits of their

ability to control German everyday life. The rather scarce evidence suggests

that individual members of the Ringvereine adapted to the repressive atmos-

phere of the Third Reich which, at least until the regime’s radicalization in

the mid to late 1930s, struggled to impose fully its own state monopoly of

violence. The persistence of some Ringvereine, articulated by Go¨ring and

other high-ranking officials, was used to legitimize the existence of the Nazi

state and justify brutal Nazi methods against ‘dangerous’ criminals.

The wider significance of the history of the Ringvereine lies in the myth

surrounding them. As Hobsbawm suggested in the postscript to the new

edition of his seminal study of social banditry, myths are central to its per-

ception and socio-political significance.

83

Similar observations apply to the

Ringvereine

. The myth surrounding them must not be taken at face value –

the fallacy of most existing accounts of the Ringvereine – but neither can it

be too easily dismissed. Dismantling this myth is difficult because of the

problems, limitations and biases of the surviving evidence. Archival material

is scant and raises many epistemological problems, as the collaboration be-

tween criminals and police left its mark in the files. All this points to the

wider question of how to write history of organized crime.

84

The belief that

Weimar Germany was undermined by the Ringvereine was a product of

late-Weimar anxieties and Nazi propaganda, before and after 1933. The

Ringvereine

tried to counter it and portray themselves as law-abiding citi-

zens, striving for respectability.

The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and Nazi Berlin

75

The Nazis propounded the myth that the Weimar Republic had been

subverted by criminal gangs and that they had repressed them. The increas-

ingly influential legend of omnipresent criminal gangs helped undermine

popular legitimacy of the Weimar Republic. It is not a coincidence that

much of the surviving evidence on the Ringvereine in the Weimar

Republic was preserved in the late 1930s by Nazi legal officials to reinforce

the Nazified history of Weimar as overridden with crime. Many Germans

perceived the Republic as a state that was unable to maintain the monopoly

of violence, whether the challenge was political or criminal. Such views re-

sulted from newspaper stories, books, plays like the Threepenny Opera and

later films such as M. Yet crime was not simply an aspect of Weimar’s

popular culture.

In the polarized political culture of the Weimar Republic accusations of

criminality featured prominently. From around 1923 Hitler and the Nazis

constantly denounced the founding fathers of the Republic as ‘November

criminals’, Socialists, Communists and Jews, who had stabbed the victorious

German army in the back in 1918. Supporters of the Republic found the

term offensive, yet, conflated with the popular stab-in-the-back legend, it

began to pervade political discourse.

85

For the Nazis and many on the

Right, the Weimar Republic was completely illegitimate: they claimed that

it had been founded and was being run by criminals. The Nazis exploited the

widespread concern with crime and used it to justify their violent methods to

reach power and, after 1933, to consolidate it. The Nazi myth of organized

crime thus linked the political and the criminal and became a very potent

political instrument. The Nazi myth of crime also had a strong racist di-

mension and, at least to some extent, helped legitimize Nazi racial terror.

Leading Nazis, including Hitler and Himmler, identified the criminal under-

world as part of a Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy, typically equating criminal-

ity, Communism and the Jews with one another, though obviously with no

evidence.

86

The Nazi myth of crime, dismantled in this article through a case

study of the Ringvereine, was a powerful, yet complicated conflation of

politics with crime and race. It was a central Nazi strategy to gain popular

support, and it was so successful that the myth still resonated with many

Germans for decades after 1945.

Christian Goeschel teaches Modern European History at the Australian

National University. His published work so far has focused on the social

and cultural history of Weimar and Nazi Germany. In 2009, he published

Suicide in Nazi Germany

(Oxford University Press) which was translated

into German in 2011 (Suhrkamp Verlag). More recently, he has begun a

new project on the entanglement between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.

History Workshop Journal

76

NOTES AND REFERENCES

I have incurred many debts during the preparation of this article, which has its origins in

presentations at the 2010 conference of the German Studies Association and the 2011 workshop

on ‘How to Write the History of Organised Crime’, at Birkbeck, University of London. I thank

David Laven, Molly Loberg, Charles van Onselen, Lucy Riall, Jan Ru¨ger, Carolyn Strange,

and the referees and editors, especially Jane Caplan, Anna Davin and Daniel Pick, for their

helpful suggestions. Finally, I thank the Leverhulme Trust for its funding of my research.

1 On context, see Richard J. Evans, Rituals of Retribution: Capital Punishment in Germany

1600–1987,

Oxford, 1996, pp. 702–3.

2 Bundesarchiv Berlin (hereinafter BAB), NS 19/4014, Bl. 169–70: Rede des Reichsfu¨hrers

SS in Sonthofen vor Generalen der Wehrmacht, 21 June 1944. My thanks to Nikolaus

Wachsmann for showing me this document. On this speech, see Peter Longerich, Heinrich

Himmler

, Oxford, 2012, p. 695.

3 On Nazi constructions of Jewish criminality, see Michael Berkowitz, The Crime of My

Very Existence: Nazism and the Myth of Jewish Criminality

, Berkeley, 2007, pp. 24–45.

4 See, for example, the studies on Italy by Steven C. Hughes, Crime, Disorder and the

Risorgimento: the Politics of Policing in Bologna,

Cambridge, 1994, pp. 1–5; John Davis,

Conflict and Control: Law and Order in Nineteenth-Century Italy

, Atlantic Highlands NJ,

1988; David Laven, ‘Law and Order in Habsburg Venetia 1814–1835’, Historical Journal 39,

1996, pp. 383–403; on France, see for example Gordon Wright, Between the Guillotine and

Liberty: Two Centuries of the Crime Problem in France

, New York, 1983.

5 Detlev Peukert, Inside Nazi Germany: Conformity, Opposition and Racism in Everyday

Life

, London, 1987, pp. 198–9. See also Eric A. Johnson and Karl-Heinz Reuband, What We

Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany

, London, 2005, p. 342.

6

On

the

collection,

see

http://www.landesarchiv-berlin.de/php-bestand/print.php?

edit¼529&anzeige¼A%20Rep.%20358%20Generalstaatsanwaltschaft%20bei%20dem%20

Landgericht%20Berlin, accessed 24 Feb. 2012; on the collection policy, see also Molly Loberg,

‘The Streetscape of Economic Crisis: Commerce, Politics, and Urban Space in Interwar Berlin’,

Journal of Modern History

, forthcoming, June 2013.

7 Anecdotal studies include Werner W. Malzacher, Berliner Gaunergeschichten: Aus der

Unterwelt 1918–1933

, Berlin, 1970, pp. 44–66; Frank Ruhla, Wir sind doch kein

Gesangverein

. . . sagten die Berliner Ganoven und so war es auch, Rosenheim, 1971; Peter

Feraru, Muskel-Adolf & Co. Die ‘Ringvereine’ und das organisierte Verbrechen in Berlin,

Berlin, 1995. The only serious historical study is by Patrick Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft ohne

Verbrecher: Konzeption und Praxis der Kriminalpolizei in der Zeit der Weimarer Republik und

des Nationalsozialismus

, Hamburg, 1996, pp. 194–5.

8 My account is based on the police investigation, for which see Landesarchiv Berlin

(hereinafter LAB), A. Rep. 358-01, no. 2220, Vorla¨ufiger Schluss- und Vorfu¨hrungsbericht, 2

Jan. 1929. For a different discussion of the case, see Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, pp. 153–4.

9 LAB, A Rep. 358-01, no. 2220, Bl. 186: Verhandelt, 2 Jan. 1929.

10 LAB, A Rep. 358-01, no. 2220, Vorla¨ufiger Schluss- und Vorfu¨hrungsbericht, 2

Jan. 1929.

11 LAB, A Rep. 358-01, no. 2220, Bd. 10, Bl. 10: Vermerk, 3 June 1938.

12 Arthur Hartmann and Klaus von Lampe, ‘The German Underworld and the

Ringvereine

from the 1890s through the 1950s’, Global Crime 9, 2008, pp. 108–35, here p.

127; on associations, see David Blackbourn, History of Germany 1780–1918: the Long

Nineteenth Century

, Oxford, 2003, pp. 210–1.

13 See The German Underworld: Deviants and Outcasts in German History, ed. Richard J.

Evans, London, 1988; and Richard J. Evans, Tales from the German Underworld, New Haven,

1998.

14 On protection, see Diego Gambetta, The Sicilian Mafia: the Business of Private

Protection

, Cambridge MA, 1993, pp. 1–2; Charles Tilly, ‘War Making and State Making as

Organized Crime’, in Bringing the State Back In, ed. Peter B. Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer

and Theda Skopcol, Cambridge, 1985, pp. 169–91, here p. 170.

15 Patrick Wagner and Klaus Weinhauer, ‘Tatarenblut und Immertreu. Wilde Cliquen und

Ringvereine um 1930 – Ordnungsfaktoren und Krisensymbole in unsicheren Zeiten’, in

Unsichere Großsta¨dte? Vom Mittelalter bis zur Postmoderne, ed. Martin Dinges and Fritz

Sack, Konstanz, 2000, pp. 265–90, here p. 272.

The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and Nazi Berlin

77

16 On gender and organized crime, see Renate Siebert, Secrets of Life and Death: Women

and the Mafia

, London, 1996.

17 Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, pp. 155–64.

18 For the numbers, see Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, p. 157.

19 Thomas Welskopp, ‘ ‘‘Die im Dunkeln sieht man nicht’’: Systematische U¨berlegungen zu

Netzwerken der Organisierten Kriminalita¨t am Beispiel der amerikanischen Alkoholsyndikate

der Prohibitionszeit’, in ‘Unternehmerische Netzwerke’: Eine historische Organisationsform mit

Zukunft?

, ed. Hartmut Berghoff and Jo¨rg Sydow, Stuttgart, 2007, pp. 291–317. On masculinity,

see the classic studies by John Tosh, ‘What Should Historians do with Masculinity? Reflections

on Nineteenth-century Britain’, History Workshop Journal 38, 1994, pp. 179–202; George L.

Mosse, The Image of Man: the Creation of Modern Masculinity, Oxford, 1996.

20 Eric Hobsbawm’s concept of social banditry, in rural societies a popular form of re-

sistance against oppression, is therefore inapplicable to the culturally and socially affirmative

Ringvereine

, but his emphasis on cultural traditions is helpful. See Eric Hobsbawm, Primitive

Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th centuries

, Manchester,

1959; Hobsbawm, Bandits (1969), London, new edn, 2000; on the mafia, see Jane C. Schneider

and Peter T. Schneider, Reversible Destiny: Mafia, Anti-Mafia and the Struggle for Palermo,

Berkeley, 2003; Anton Blok, The Mafia of a Sicilian Village, 1860–1960: a Study of Violent

Peasant Entrepreneurs

, Oxford, 1974; see also the recent work by Letizia Paoli, Mafia

Brotherhoods: Organized Crime, Italian Style

, Oxford, 2003, p. 16.

21 On perceptions of a post-war moral disorder, see Richard Bessel, Germany after the

First World War

, Oxford, 1993, pp. 220–53.

22 Sace Elder, Murder Scenes: Normality, Deviance, and Criminal Violence in Weimar

Berlin

, Ann Arbor, 2010, pp. 20–1; Richard F. Wetzell, Inventing the Criminal: a History of

German Criminology, 1880–1945

, Chapel Hill, 2000, pp. 174–8. More generally, see Daniel Pick,

Faces of Degeneration: a European Disorder, c.1848–c.1918

, Cambridge, 1993.

23 Richard F. Wetzell, ‘Criminology in Weimar and Nazi Germany’, in Criminals and their

Scientists: the History of Criminology in International Perspective

, ed. Wetzell and Peter Becker,

Cambridge, 2006, pp. 401–23.

24 See, for instance, Peter Fritzsche, Reading Berlin 1900, Cambridge MA, 1996; Benjamin

Hett, Death in the Tiergarten: Murder and Criminal Justice in the Kaiser’s Berlin, Cambridge

MA, 2004.

25 Vossische Zeitung, 1 Jan. 1929; on the press, see Bernhard Fulda, Press and Politics in

the Weimar Republic

, Oxford, 2009.

26 Vossische Zeitung, 5 Jan. 1929.

27 Der Montag, 7 Jan. 1929; Der Montag, 31 Dec. 1928; Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, p.

154. On Weimar perceptions of crime, see Todd Herzog, Crime Stories: Criminalistic Fantasy

and the Culture of Crisis in Weimar Germany

, New York, 2009, p. 6.

28 Der Angriff, no. 2, 14 Jan. 1929, ‘Kampf um Berlin’.

29 Quoted in Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, p. 154, citing Vorwa¨rts, 31 Dec. 1928.

30 On Alsberg and the trial, see Curt Riess, Der Mann in der schwarzen Robe: Das Leben

des Strafverteidigers Max Alsberg

, Hamburg, 1965, pp. 203–8. On Frey’s recollections, see

Erich Frey, Ich beantrage Freispruch: Aus den Erinnerungen des Strafverteidigers Prof. Dr.

Dr. Erich Frey

, Hamburg, 1959, pp. 247–68.

31 LAB, A Rep. 358-01, no. 2220, Bl. 101–105, Max Alsberg an den Herrn

Oberstaatsanwalt, 10 Jan. 1929.

32 LAB, A Rep. 358–02, no. 2220, Bl. 76ff.: ‘Im Namen des Volkes’; Wagner,

Volksgemeinschaft

, p. 166.

33 Hsi-Huey Liang, Die Berliner Polizei in der Weimarer Republik, Berlin, 1977, p. 164.

34 Wagner and Weinhauer, ‘Tatarenblut und Immertreu’, p. 274.

35 Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, p. 171.

36 Robert Heindl, Der Berufsverbrecher: Ein Beitrag zur Strafrechtsreform, Berlin, 1926;

on Heindl, see Herbert Reinke, ‘‘‘Robert Heindl’s Berufsverbrecher’’: Police Perceptions of

Crime and Criminals and Structures of Crime Control in Germany during the First Half of

the Twentieth Century’, in Crime and Culture: an Historical Perspective, ed. Amy Gilman

Srebnick and Rene´ Le´vy, Aldershot, 2005, pp. 49–62.

37 LAB, A. Pr. Br., Rep. 030, Tit. 198B, Nr. 21309, Bl. 21: Weiss to Max Alsberg, 23

March 1929; ibid, Bl. 23–4: Abschrift Robert Heindl an Max Alsberg, 21 March 1929.

38 On background, see Nikolaus Wachsmann, ‘Between Reform and Repression:

Imprisonment in Weimar Germany’, Historical Journal 45, 2002, pp. 411–32, here p. 424.

History Workshop Journal

78

39 Heinrich Berl, Die Heraufkunft des fu¨nften Standes: Zur Soziologie des Verbrechertums,

Karlsruhe, 1931, p. 79.

40 Quoted in Wagner and Weinhauer, ‘Tatarenblut und Immertreu’, p. 276,

citing Sitzungsberichte des Preussischen Landtages, 3. Wahlperiode, Band 3, Berlin, 1929,

p. 4,689.

41 On Landsberger’s work for the Ringvereine, see PEM [Paul Marcus], Heimweh nach dem

Kurfu¨rstendamm: Aus Berlins glanzvollsten Tagen und Na¨chten, Berlin, 1952, pp. 45–6.

42 Arthur Landsberger, Die Unterwelt von Berlin: Nach den Aufzeichnungen eines ehemali-

gen Zuchtha¨uslers. Mit einer Schlußbetrachtung von Dr. Max Alsberg, Berlin, 1929, p. 14.

43 Landsberger, Die Unterwelt von Berlin, pp. 17–24, p. 24.

44 Anton Kaes, M, London, 2000, pp. 50–1.

45 Kaes, M, pp. 66–9; p. 73 ; on Muscle-Adolf’s advising of Lang, see Ulrich Zander, ‘Die

Schlacht am Schlesischen Bahnhof’, Der Tagesspiegel, 28 Dec. 2008.

46 LAB, A Rep. 358–01, no. 525: Abschrift Krim. Tgb., 21 March 1931; for a different

interpretation of this case, see Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, pp. 168–9.

47 LAB, A Rep. 358–01, no. 525, II: Reserve-Mordkommission, 24 March 1931;

Reserve-Mordkommission, 30 March 1931; Vermerk, 7 April 1931. For an example of the

syndicates

bullying

witnesses,

see

‘Im

Schreckensbann

der

Ringvereine’,

Berliner

Lokal-Anzeiger

, 9 Oct. 1931.

48 Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, pp. 186–7.

49 Eve Rosenhaft, Beating the Fascists? The German Communists and Political Violence,

Cambridge, 1983, pp. 23, 134; for a contemporary Nazi source, see Erwin Reitmann, Horst

Wessel: Leben und Sterben

, Berlin, 1933, p. 28. On Wessel, see Daniel Siemens, Horst Wessel:

Tod und Verkla¨rung eines Nationalsozialisten, Munich, 2009.

50 Hans Maikowski, Sturm 33, geschrieben von Kameraden des Toten, Berlin, 1933, p. 33.

On Maikowski, see Jay W. Baird, To Die for Germany: Heroes in the Nazi Pantheon,

Bloomington, 1990, pp. 91–100.

51 Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, p. 160, n. 39 (p. 449). More generally, see Rosenhaft,

Beating the Fascists?

, p. 134; Pamela E. Swett, Neighbors and Enemies: the Culture of

Radicalism in Berlin, 1929–1933

, Cambridge, 2004, pp. 188–213.

52 LAB, A Rep. 358-01, no. 8033, Bl. 3: ‘Bericht u¨ber einen politischen Mord am

Mittwoch, dem 3. August 1932 vor dem Hause Triftstr. 67’ (44. Revier. Berlin, den 3.

August 1932); see also Bl. 127–30: ‘Bericht’, 5 Aug. 1932.

53 On the homicide squad, see Elder, Murder Scenes, pp. 45–80.

54 LAB, A Rep. 358-01, no. 8033: ‘Auszug aus dem Strafregister’, undated.

55 LAB, A Rep. 358-01, no. 8033: Bl. 46–8: ‘Vorgefu¨hrt erscheint’, 3 Aug. 1932.

56 LAB, A Rep. 358-01, no. 8033: Bl. 52–8: ‘Vorgefu¨hrt erscheint’, 3 Aug. 1932.

57 LAB, A Rep. 358-01, no. 8033: Bl. 67–70: ‘Vorgefu¨hrt erscheint’, 3 Aug. 1932

58 Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, p. 172.

59 For the 1933 decree, see The Nazi Concentration Camps, 1933–1939: a Documentary

History

, ed. Christian Goeschel and Nikolaus Wachsmann, Lincoln NE, 2012, pp. 20–1; on the

increasing Nazi persecution of ‘habitual criminals’ and ‘asocials’, see Nikolaus Wachsmann,

‘The Nazi Policy of Exclusion: Repression in the Nazi State, 1933–1939’, in Nazi Germany, ed.

Jane Caplan, Oxford, 2008, pp. 122–45, esp. pp. 133–7.

60 On the radicalization of the judiciary after 1933, see Nikolaus Wachsmann, Hitler’s

Prisons: Legal Terror in Nazi Germany

, New Haven, 2004, pp. 165–88.

61 LAB, A Rep. 358-01, no. 8035, Bl. 76–84: ‘Im Namen des Volkes’, 27 April 1934.

62 LAB, A Rep. 358-01, no. 8039, Bl. 33: Zuchthaus Untermassfeld an die

Staatsanwaltschaft Berlin, 19 April 1943. On the transfer of state prisoners to the police and

the camps, see Nikolaus Wachsmann, ‘ ‘‘Annihilation through Labor’’: the Killing of State

Prisoners in the Third Reich’, Journal of Modern History 71, 1999, pp. 624–59.

63 Nikolaus Wachsmann, ‘From Indefinite Confinement to Extermination: ‘‘Habitual

Criminals’’ in the Third Reich’, in Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany, ed. Robert Gellately

and Nathan Stolzfus, Princeton, 2001, pp. 165–91.

64 Christian Goeschel and Nikolaus Wachsmann, ‘Before Auschwitz: the Formation of the

Nazi Concentration Camps, 1933–9’, Journal of Contemporary History 45, 2010, pp. 515–34,

here p. 522.

65 BAB, R 19/395, Bl. 36–45: ‘Abteilung II des Preuss. Ministeriums des Innern’, 11 Sept. 1933.

The Criminal Underworld in Weimar and Nazi Berlin

79

66 Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, pp. 215–16. See also ‘Erfolg der Vorbeugungshaft: 476

Berufsverbrecher mit fast 5000 Jahren Freiheitsstrafen’, Berliner Bo¨rsen-Zeitung, no. 500,

24 Oct. 1935, reprinted in The Nazi Concentration Camps, ed. Goeschel and Wachsmann,

pp. 294–6.

67 See Peukert, Inside Nazi Germany, pp. 198–9; Johnson and Reuband, What We Knew, p. 342.

68 Max Hagemann, ‘Verbrechertum, organisiertes’, in Handwo¨rterbuch der Kriminologie

und der anderen strafrechtlichen Hilfswissenschaften

, ed. Alexander Elster and Heinrich

Lingemann, Berlin, 1936, vol. 2, p. 903.

69 Kurt Daluege, Nationalsozialistischer Kampf gegen das Verbrechertum, Munich, 1936,

pp. 15–16, 20–1.

70 Daluege, Nationalsozialistischer Kampf, pp. 15–21 (pp. 15–16 for quotations). For

background, see Wagner, Volksgemeinschaft, pp. 194–5.

71 SS-Brigadefu¨hrer, Generalmajor der Polizei Nebe und SS-Obersturmbannfu¨hrer

Oberregierungs- und -kriminalrat Werner, Organisation und Meldedienst der Reichs-

kriminalpolizei

, Berlin, 1941, p. 17.

72 BAB, R 58/483, Bl. 20–8: ‘Die Aufkla¨rung der durch Mitglieder des fru¨heren

Unterweltvereins

‘‘Rosenthaler