12/11/2007 03:35 PM

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 1 of 11

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912

Subject

Key-Topics

DOI:

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition

RAIMO ANTTILA

Linguistics

»

Historical Linguistics

cognition

10.1111/b.9781405127479.2004.00012.x

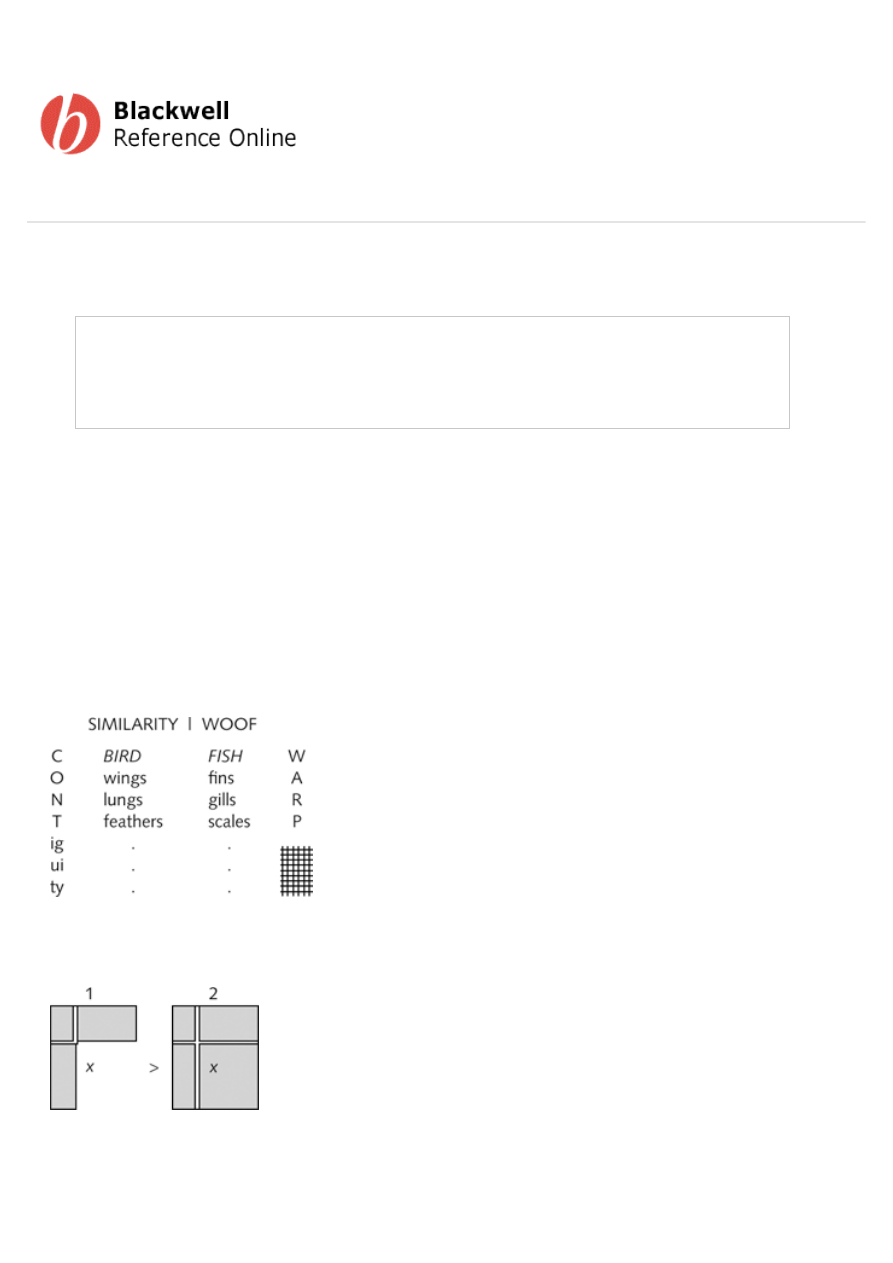

Greek science was based on an analogical grid of a contiguity axis (also known as causal, or indexical) and a

similarity axis. Thus Aristotle defined genera in the way shown in

figure 10.1

(Hesse 1966: 61; this has often

been quoted, e.g., Anttila 1977: 18; Itkonen 1994: 44; Itkonen and Haukioja 1996: 137).

Lining up secure similarities gives an anchor for going into the uncertainties (the dots in

figure 10.1

),

especially if there is an imbalance (

figure 10.2

).

1

This is still the essence of scientific analysis (and everyday

perception and understanding). Note how water waves led to sound waves to light waves, and so on (Hesse

1966: 11, 68, 93–6). There are positive and negative analogies that build up explanations, but particularly

useful in everyday life is persuasive analogy - for example, the state is to its member as a father is to his

child - and such analogies are the essence of cultural networks and mythologies (there is nothing else, in

fact).

2

Analogy mediates between actuality and potentiality.

Figure 10.1 The structure of analogy

Figure 10.2 Gap filling

12/11/2007 03:35 PM

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 2 of 11

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912

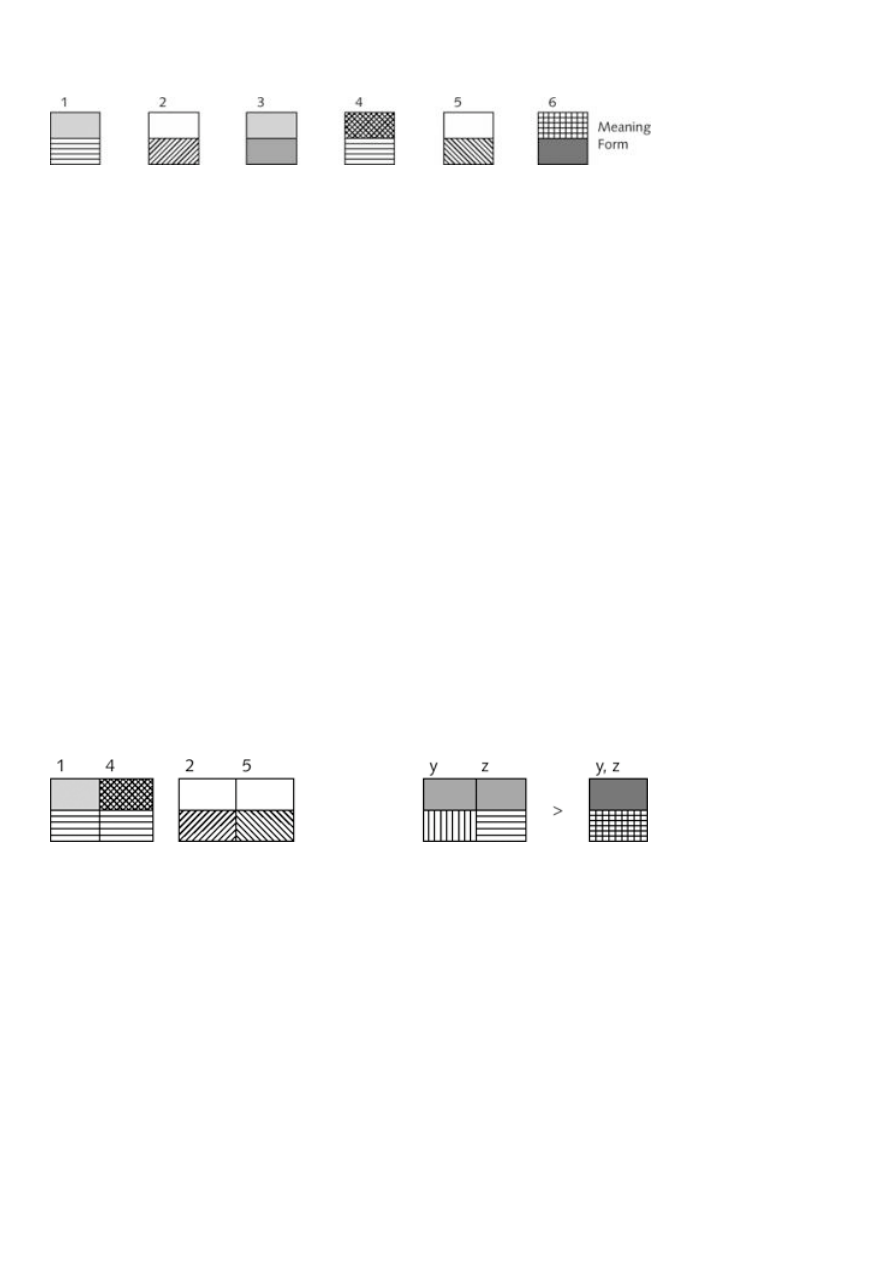

Figure 10.3 Meaning and form

The two axes in the analogical frame (reflecting a proportional relationship, an expression of similarity of the

sort A : B :: C : D) cover any kind of material where we have similarity and contiguity. In

figure 10.2

, we have

on the left two axes which share the top left corner unit. There is a gap x that calls out to be filled by

analogy; this has happened on the right, with the box x. This situation is usually given with numbers: 4/2 =

10/x; x = 5, and no problems arise, since we get exact results (identical relations). But with most material

fed into such structures we have to be happy with vaguer similarities (in other words, the similarity stretch

between x and x [>] can be a long gradient scale = drift). Note that the left-right sequence in

figure 10.2

succinctly summarizes analogy's two great theoretical powers. First, it shows that analogy is the agent that

dives into the hermeneutic gap, the átopon, the ‘out of place,’ the strange, the problem that asks to be

explained or solved; second, at the same time it is an impelling force of closure in gestalt terms. In such

structural asymmetry perception strives for wholeness. Thus, hermeneutics (pattern explanation) and gestalt

theory work under the same laws of human understanding. We also secure imposing metatheoretical glory

for analogy, although we just generally see its practical application value.

When it comes to linguistic signs - and let's just say words at this juncture - we have to remember that they

are combinations of form and meaning (again simplifying the situation to a Saussurean colligation).

Incredible mistakes are committed if only form is considered, and thus analogy seems to fail (but it is the

linguist who has failed; cf. Itkonen and Haukioja 1996: 135). Similarity relations exist both in meaning and

in form, and meaning and form are combined in the symbolic colligation. Observe the six such colligations in

figure 10.3

, say, where the squares represent words. The top part of the square represents meaning and the

bottom form. Words (2) and (5) share the same meaning, and (1) and (4) the same form. Various degrees of

similarity can also be perceived (

figure 10.4

). Thus a figural set-up with identical form would work toward

changing meaning (1) toward meaning (4) or vice versa (the diagrams again emphasize identity), or with (2)

and (5), the forms could go either way. The actual forces depend on the centrality of each feature in context,

culture, grammar, and so on. Numbers (2) and (5) could also portray allomorphy, as could (y) and (z), since

the lexical meaning is identical, and in this situation contamination (y, z) is also normal.

Figure 10.4 Similarity relations

The force here has been described (see, e.g., Anttila 1972), in a way used ever since the Ancient Greeks, as

“one form-one meaning” (although this particular characterization is mine, as well as the notation below), an

ideal in sign formation that of course will never be achieved, but the ideal pushes constant change (cf.

Anttila 1977:55–8, 1989: 100–1, 107, 129–30, 143–6, 407; Itkonen and Haukioja 1996: 162). The main

force in such change is analogy, as rationality, of course. What this principle says is that the configurations V

(two meanings - one form) and Λ (one meaning-two forms) tend to be leveled out to I or split into I, I.

(Then of course metaphor, metonymy, loan translation, and folk etymology again create polysemy I > V.)

Allomorphic alternation, Λ, as in the original shade/shadow, or cow/ki-ne, tends either to split into

independent words I, I (shade and shadow with different meanings) or to get leveled out into I (as in

cow/cow-s). Extension of alternation from a more restricted environment to practically every word as in

Lapp/Saami consonant gradation, Λ, I > Λ, still represents unity for diversity. Leveling and extension remain

as the most prevalent analogical change concepts.

12/11/2007 03:35 PM

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 3 of 11

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912

The situation (1, 4) in

figure 10.4

is so-called homonymic clash, and if change occurs, formal differentiation

is expected. Keller's treatment of German englisch ‘angelic’ and englisch ‘English’ is a good example (1994:

80–3, 93–5, 124, 132, 156). In a context like englische Mädchen the conflict was insidious, and the first one

was replaced by engelhãft, restoring one meaning-one form. The identical base morphemes need not be

perceived; the sign is normally taken as a whole. But any feature perceived and any interpretation

successfully forced on a percept is a potential anchoring for analogy. Thus French cerise > cheris was

interpreted in English to have the pl. -s, which then necessitated a new analogical sg. cherry. Similarly Arabic

kitabu ‘book’ in Swahili was interpreted to contain the native noun classifier ki-, whereby the plural had to

manifest as vitabu. Such examples are commonplace (latest treatment in Itkonen 1999: §III).

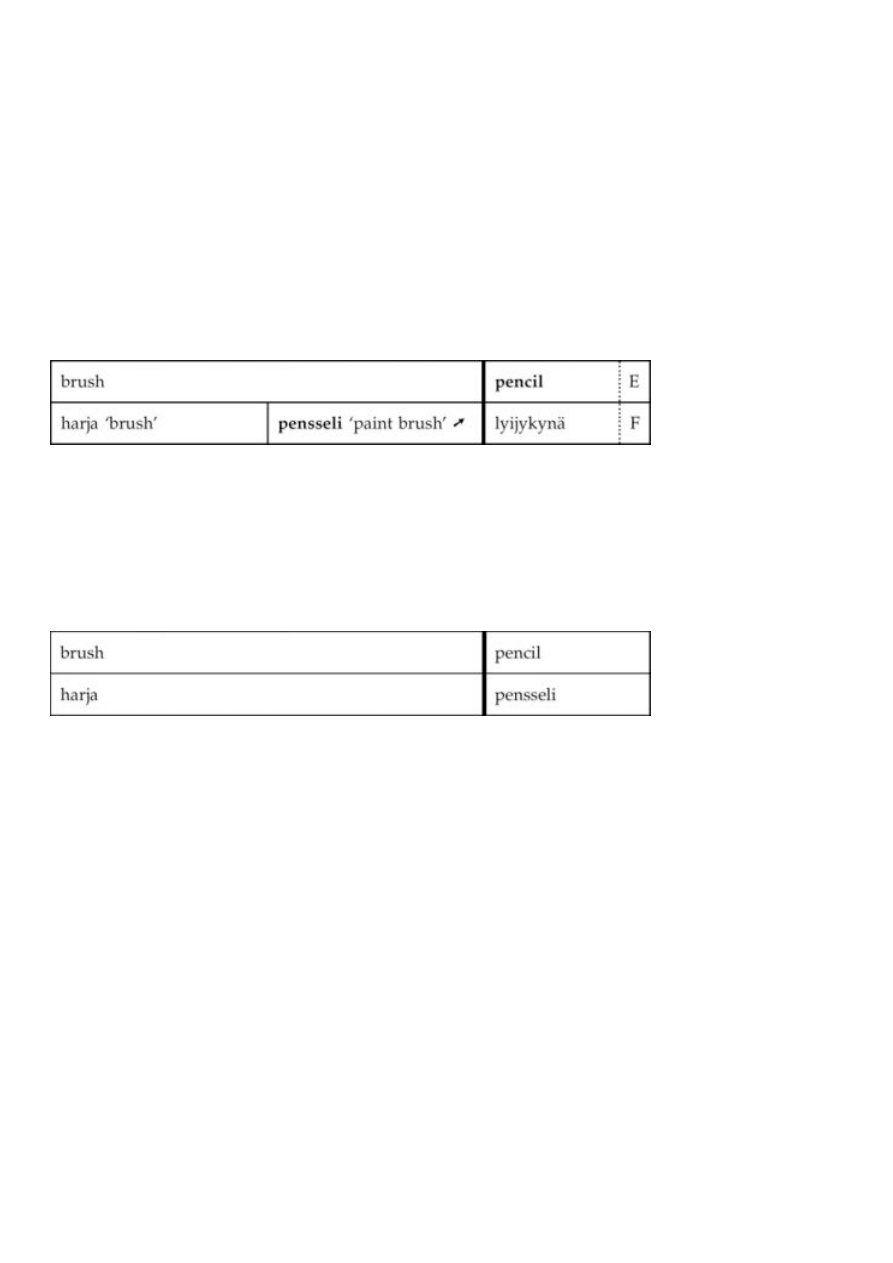

These figural form-meaning colligations appear everywhere in language structure and use. Consider

borrowing, perfectly analogical. For example, note the following situation between American English and

Finnish as pertains to certain “tools of smudging,” forming thus a general semantic similarity field of

something like this articulation:

This kind of different partition of semantic fields is typical between languages, and it does not matter that

lyijykynä ‘lead-pen/quill’ is motivated. The relation here between the two languages is roughly Λ/I (with the

slash indicating the formal similarity (the arrow) in pensseli/pencil). In American Finnish however, where

English is an extremely strong social force (the necessary indexical anchoring for analogy), it exerts the one

meaning-one form pressure on Finnish. Since pensseli /pencil is a formal match, it is kept, but with English

semantics, whereupon harja takes on the whole range of English brush:

The result is greater one-to-one unity, both in form and in meaning, between English and American Finnish

(i.e., I I). This is quite common in (American) immigrant situations; for example English like (1)

‘similar/equal’ and (2) ‘to be fond of’ versus German gleich(-) (1) has yielded Pennsylvania Dutch (2) ich

gleiche dich ‘I like you’. Similar examples could be multiplied by the thousands.

1 Definition of Analogy

The above was of course quite general, but sufficient; largely the proportional aspect was treated, hinted at

with language material. Now when the basic structure has been laid out, we can add a basic definition:

analogy is a relation of similarity, that is, a diagram (in the sense of Peirce 1965: vol. II, with warp and

woof). In other words it is structural similarity (Itkonen and Haukioja 1996: 157; cf. Holyoak and Thagard

1995: 208). A diagram is the central icon, central in any science. But it is central in perception and cognition

also, because if we would just rely on images (i.e., mere pictures of feeling-similarity), we would not get

anywhere (not out of our own heads, although we would not even know it). A diagram gives us a reasonable

map of reality pointing toward further knowledge. All this is heightened with the higher-order diagram, the

metaphor (which I try to avoid here for reasons of space).

The proportion brings out the relation quite nicely and convincingly (for most linguists). It can be said that

the faculty to analogize is innate, and language faculty falls under this imperative. More generally one can

say that we have here a relation between a model and a copy, and the copy can be quite blurred (or in other

words: mapping knowledge from one domain into another: Itkonen and Haukioja 1996: 137). In language it

has been quite comfortable to espouse the proportion (Paul 1880), but one needs the other end also (from

12/11/2007 03:35 PM

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 4 of 11

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912

Hermann 1931 to Winter 1969; see Anttila 1977: 72–6).

3

The ability to copy is enormously powerful, as

seen in language learning, or any learning, in the social context (Short 1999). Thus it is no wonder that

linguistic signs can also be copied and modified, lifted out of their original contexts. Note that in science we

end up with theoretical terms that are stipulated (“not seen”), whereas in language the new items pop out

immediately for approval (whether they get approved is another matter). There is no difference in the

analogical structure.

2 Transposition and Analogy

All cognition is based on relation and order, that is, gestalts. Gestalt is ultimately based on relations,

because it is the total relation of relations (Weinhandl 1960: 132, 166).

4

The most crucial concept in all this

is that of transposition: gestalts are invariants of transpositions, similarities of correspondences. “For

whatever one would mean by gestalt, the transposability of gestalt has to be taken as its essential property,

as already von Ehrenfels tried to show” (Kaila 1945: 65; below Kaila's emphasis is eliminated). “We have

verified that one essential side in symbol function is connected with intermodal transposability [and add

analogical extension]. Here one sees the connection of symbol function with gestalt formation” (pp. 65–6).

One has to assume that “the organs forming the gestalts reach the invariants contained in the multiplicity of

receptor excitation. I call the principle in this assumption the principle of invariance of perception.

‘Invariants’ mean here the unifiedly recurring relations in the different areas with a multiplicity of excitation”

(p. 86). “Thus the process of consciousness is from beginning to end a search for invariants, finding them,

and partly also creating them” (p. 89; my translation). Transposition holds the key role (Weinhandl 1960:

406–12) in connection with invariance, isomorphy, language, natural law, and constancy. When a factor

(structure-point) varies, matching covariance of other factors produces invariance (p. 406). Transposition is

crucial for our experience, memory, and cognition, and it presupposes recognition (p. 407), since we have to

recognize a structure in other materials. In the symbolic mode (verbal, graphic, numerical) we get

categorization in that we assign facts to recognized concepts, thereby getting an isomorphic representation

for the object (one meaning-one form; Shapiro 1991). Transposition thus provides (in immediate experience)

an isomorphic replica (Kaila 1945: 407); similarity is again central (cf. pp. 206, 408).

5

If we could not

experience similar structures or figures or facts, we would really have nothing. It is constancy that gives

another match to invariance of objects (as experienced or perceived), and thus fills another aspect of

phenomenal representation (p. 411). This is how we get a constant external world and a chance for a fixed

starting-point (e.g., for analogy). This is, again, how we can further explain the human mechanism for

fiction and hypostatization. More particularly, we see the immediate reasons for the necessity of

epiphenomenal meanings (grammatical meaning, metaphor, riddles, and the like).

We have again reached the concept of analogy, although it might not be apparent to all linguists. The step

from transposition to analogy can be best exemplified by the fact that our perception grasps the world

through complex formation (perception of wholes) and abstraction (Dörner 1977). Our concepts are

relational stencils that classify incoming information. Gestalts and super-signs are characteristically of the

structural kind, since their composition can be transposed into other media or units (p. 74). A structure or

configuration of relations establishes a gestalt, and since the relations are not contained in the parts of the

whole, but obtain between them, a gestalt is indeed “more than the sum of its parts” (p. 75). As for

transposability, Dörner states that it is nothing but the possibility of interchanging the components of a

structure with others. The gestalt principle is simply a structure of empty slots for the components (pp. 75–

6). Finally, Dörner shows how argument from analogy consists in (i) matching a known domain of reality with

another structurally similar one, in (ii) abstracting the structure, the gestalt from the known, and (iii) putting

this structure over the unknown area. “An argument from analogy is an attempted transfer of a structure

from one domain of reality to another” (p. 81). This is critical analogy, but the same holds for what we know

from language, and this is what philosophers, psychologists, and scientists have come up with time and

again. Gestalt principles give a solid philosophical foundation for analogy and inference in general. Analogy,

as used in traditional linguistics, is perfectly valid. Whatever its limits are, they cannot be rectified or

eliminated by denying the notion altogether, since it is all we have (cf. Holyoak and Thagard 1995: 148,

262). Further, it is no use trying to formalize it for “proper” explanation, as linguists wanted to do during

and since the 1970s. Harald Höffding (1924: 26) already analyzed concepts like analogy and symbol as

correlative concepts expressing a mutual relation. Höffding took synthesis and relation as correlative

categories, exactly like continuity and discontinuity, resemblance and contrast (difference). These are

fundamental categories; analogy is formal (cf. Itkonen 1994: 52), and totality real.

12/11/2007 03:35 PM

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 5 of 11

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912

In short, similarity is the most important holistic process in mental life. It is the basic axiom for all cognition,

and since we are dealing with similarity we have here a continuity agent between percepts, parts, and even

sciences (Höffding 1924; Anttila 1977: 5). Models of formal logic fail, because analogy does not fit into their

either-or tallies. Note that Leibniz already pleaded for topology, analysis situs; such notions have been

rediscovered in cognitive linguistics (see Heine and Traugott, this volume), curiously tied with metaphor, not

analogy.

In fact, rationality is a process of becoming from indeterminate vagueness, and thus change is a primary

aspect of reality (Shapiro 1991: esp. §5). The use of symbols involves their further determination and this

necessarily leads to change. Language use is largely problem-solving in communication (including its many-

faceted context) and thereby falls under rationality, since one cannot solve problems without any reason.

Language use falls likewise under emergence phenomena in which structure and becoming cannot be

separated. And indeed, analogy is the main force in language structure, and it is an agent of change. What

has confused many is that similarity/analogy works both in structure, giving it cohesion, and as a process

for problem-solving (Itkonen 1991: 313–20, 1994: 44; Itkonen and Haukioja 1996: 136, 142). This is

traditionally well understood, although since the 1960s both aspects have been badly blurred, apparently

both on purpose and by accident.

6

3 Analogy and Metaphor

The two crucial factors in any relevant conception of cognition, namely similarity and contiguity, come out in

(cognitive or otherwise) linguistics as metaphor and metonymy. Of course, today the Peircean terms iconicity

and indexicality also abound, particularly the former (see Anttila and Embleton 1995: n.9). Now there is no

end to the literature on metaphor, and often no indication is given that the notion was quite well understood

before.

7

Something like this was bound to happen, since Chomsky's denial of metaphor as a relevant thing

and the rejection of analogy by the whole school was startling incompetence. Of course formalists and those

sympathetic to them say that explaining everything with metaphor does not explain anything.

8

In principle

there is no difference between metaphor and analogy for our purposes.

9

It was a mindless coup in linguistic

theory to abolish analogy in the face of its long tradition in linguistics and philology (although its

reintroduction in Optimality Theory has now made some linguists revolutionary).

The problem with analogy seems to be the following: against the nice dualities like similarity ~ contiguity,

metaphor ~ metonymy, icon ~ index, abduction ~ induction, which all match, analogy is a mixed bag; it

mixes the two columns, as it were. Since the context (the warp) is so crucial, I have called analogy an

indexical icon (Anttila and Embleton 1995: 98). The contiguity aspect of analogy (nearness) is also

emphasized by Coates (1987: 337). Locality is again central in cognitive psychology and linguistics, and this

is true of analogy also, since it requires orientation as a crucial anchoring factor (Vaught 1986: 324–5; Haley

1997). In current cognitive theory the prototype gives the orientation point, and then metaphor carries it

further. Note that this is exactly what the Ancient Greeks had in their paradigm (example) and analogy

(proportion). The paradigm is the indexical part.

Cognitive linguistics has got great mileage out of body metaphors, here too ignoring earlier work (Anttila

1992a: 66). The body is also central in the problem of foundational analogy, or incongruous counterparts, in

orientation (right and left) (Vaught 1986: 314–16, 325–6; see also Haley 1997 for foundational analogies).

Finally, whether we accept it or not, it is constructive to remember Vaught’ s plea for an analogical relation

between the immediate and the dynamic object and the two interpretants (1986: 321). Analogy joins them,

but also keeps them separate (distant). Meaning is thus perfectly analogical.

10

One defense of metaphor in cognitive linguistics is that semantic field theory would not be able to shift

between fields, whereas metaphor offers such a possibility (cf. Anttila 1992a: 66). This is strong camouflage,

since analogy was always taken as giving this ability (Höffding 1924: 72; and others).

11

There is no

difference between analogy and metaphor in this context, and we have seen how analogy performed exactly

this service (transposition; Dörner 1977).

4 Leaking Syllogisms

12/11/2007 03:35 PM

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 6 of 11

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912

Among the first to combine analogy with abduction was Anttila (1977), but now this is becoming more

matter of fact, for example, in Thagard (1988), for whom, by necessity, as we now know, analogical

inference involves similarity and causality (pp. 60–5, 165). Past solutions are crucial for new problem-

solving, in other words, experience in context. Although analogy mixes induction and abduction, no harm is

done, because in historical explanation we need just that. This is also the situation in the computational

paradigm in which problem-solving must be tied to induction (Thagard 1988: xi, 15, 19, 26, 70, and

particularly his diagram: 28, which shows that in his system induction feeds into abduction), abduction (pp.

52–60), analogy (22, 24, 92–5), or analogical abduction (60–2). What all this means is that analogy is crucial

in any science; it improves explanations within theories and supports hypotheses already discovered (pp. 92,

94–5). Since analogy goes from individual to individual (Aristotle; Thagard 1988: 95; Melis 1989: 89) it is

particularly handy in any real or historical context. It also supplies a frame for holistic thinking (Melis 1989:

89), or is in fact holistic and analytic at the same time (Haley 1988: 6). Analogy can be taken as an inference

that leads to a solution of a problem, thus mixing abduction, induction, and the practical syllogism, that is,

perception and experiential context as premises (necessary conditions) lead to interpretation as conclusion

(cf. Melis 1989: 96). Time and again it comes out that analogy is an agent of closure (Melis 1989: 89), and

only its strictest forms are formalizable, otherwise the human is necessary (Melis 1989: 98–9; Coates 1987:

321, 319, 336), and in fact we need key words even in computer programs (Melis 1989: 104). The human is

necessary, because that is where experience and the true analogical ability reside (this is de facto another

strong plea for hermeneutics). Also Thagard's program PI (= process of induction) requires background

knowledge stored in concepts, and uses a goal-directed component (p. 29), and schemas over propositions

(p. 31), concepts over rules (pp. 38–9; Coates 1987: 320, 337). No wonder formalists are unhappy. As for

metatheory and for treating change, they are also wrong. To put the issue in a nutshell in this context:

traditional analogy, as manifested and known in historical linguistics, was and is right (cf. the “proportional”

schemas in Thagard 1988: 93; Melis 1989: 90; Holyoak and Thagard 1995: 95).

At this juncture it is good to remember that analogy is indeed often equated with induction (Itkonen 1994:

45; Itkonen and Haukioja 1996: 132, 140) - and correctly so. But induction has a bad ring to many

theoreticians, and maybe this is why many push metaphor, if they can ignore the equation of metaphor with

analogy.

12

Ignorance is no help in anything but one's piece/peace of mind. But of course the metaphor

cannot do without an indexical launching pad. Haley points out that there is a powerful interactive index in

metaphor:

This indexical component of metaphor is … its clash of dissimilars… . Like a red flag, another

Peircean example of the Index, the semantic shock of a novel metaphor is what brings it into

the foreground of perception. Or we might say that the figural tension of the metaphor is the

indexical “smoke” which “points” (the first function of any index) to the metaphorical “fire.”

(1988: 14)

This kind of index forces something to be an icon: “meaningful metaphorical tension is that kind of index

which contains an icon, as a photograph reliably ‘points’ to the object represented by its iconic image” (p.

15). Such indexical interaction (p. 53) is crucial throughout. An index in this mode shapes its object and

becomes “something of an icon in itself” (p. 135; cf. p. 98), which is also true of assimilation in sound

change, it would seem. “[W]hat identifies something as a candidate for interpretation as metaphor is species

opposition, for it is this that provokes the search for a figural icon, its object, and their similarity. If this

search is successful, the utterance is confirmed as metaphor” (p. 100; note transposition and closure again).

“[I]t is the metaphorical index that is forever forcing us to understand and appreciate the proliferation of

semantic species” (p. 151). Throughout his book Haley shows that when the iconic content approaches

diagrammaticity or analogy the index is also enhanced, suggesting more imaginative possibilities (p. 161; cf.

also pp. 22, 33, 56, 78, 84, 143); in fact he “believe[s] diagrammatic thought must have been the

breakthrough which crystallized the differentiation of semantic levels in language and consciousness” (p.

153). In other words, we see that analogy/metaphor is an agent of closure, filling the átopon, and thus there

is a new place.

13

The inductive attention-arousing indexical gap in the diagram is of course “the initial problem” on which

perception and abduction feed (major premise: “The surprising fact, C, is observed”, from Peirce; e.g., Anttila

1989: 404, 1992b). Treating English place names, Coates (1987: 330) “suggests that the parameter of

relatedness is distance apart, literally the distance on the ground - or the sea - between them” and uses this

12/11/2007 03:35 PM

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 7 of 11

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912

relatedness is distance apart, literally the distance on the ground - or the sea - between them” and uses this

to explain analogical reformations. The distance can come from a mental map, of course, but “nearness is

the spatial expression of, and is prototypical for, the relation of similarity” (p. 337). This is another

convincing case of the index working itself into a kind of icon along the lines Haley suggests for the

metaphor. Spotting such a tension or gap is of course an invitation to solve the problem, that is, it is an

imperative to action, and such action propels change, in fact and by definition, whether we want definitions

or not.

14

So, whether we take our path through metaphor or any of the leaking syllogisms (abductive, practical,

actionist; see Anttila 1992b), we are led to fallible situations (cf. Holyoak and Thagard 1995: 209), but these

situations are the only ones that lead to new knowledge and solved problems (which then immediately

create new problems; Short 1999). This is one reason Peirce called abduction and induction ampliative

inference. It is the reason too why prediction and formalization are really of little use. This is the traditional

position. It is also the position people come back to, again and again, whether with new terminology or not.

Note in this context van Wolde (1996): she rightly emphasizes the analogical element in Peirce's logic,

although he himself dropped it later (in name at least). She pleads for a combination of induction, abduction,

and analogy, since all are inferences from sampling. Abduction (possible to general) makes a leap for a

possible truth, induction (actual to general) does not secure certain truth either, and both are analogic in

nature (Peirce's ampliative inference). Nothing in substance seems to have been added; it is the old names

game again. Van Wolde concludes: “So far, however, no analogic has been set up and its elementary value

for the solution of problems is not as yet fully taken into account” (p. 348). This sounds baffling, because

Vaught (1986) went a long way on the high theory side, and in fact such a logic has been standard in

linguistics for decades (note analogy as an indexical icon in Anttila and Embleton 1995). Note that even

deduction (van Wolde's logic) needs analogy to be learned! When she uses analogical inference to transpose

experience into cultural codes, and then these codes into behavior and action (p. 346), she is applying

analogy according to Ancient Greek science (and current folk mythology). There is indeed transposition

between fields or domains; this comes out and has come out at every turn, now and in history (cf. Holyoak

and Thagard 1995: §§7, 9).

5 Measuring and Classifying Analogy

What is extremely important in this is the role of indexicality. Of course, ever since Saussure (and beyond)

association has represented it (see also Esper 1973 from the psychological point of view), but analogy asks

for indexicality as ascribed (assigned) similarity. On this basis Coates can give a typology of motivation for

analogical reformation (if change takes place) (1987: 333–4). Such a typology must indeed be based on

somehow measuring the interlocking of similarity and indexicality. As already mentioned, the difficulty is

that contexts and percepts cannot easily be given or defined in advance. This is why the usual classificatory

schemes of analogy are not very useful. They try to give in advance what the dynamics are and what comes

before and what the result would be. The most famous case of such classification attempts is the

“controversy” between Kurylowicz (e.g., 1945–9) and Mańczak (e.g., 1958, 1980), portrayed succinctly, for

example, by Best (1973: 61–107; cf. also Anttila 1977: 76–80), and most recently “tested” by Salm (1990)

through verbs (see also Hock 1991: chs 9–11; Winters 1995; Hock, this volume). Roughly, one can say that

Kurylowicz looked at the issue from the point of view of grammar, sphere of employment, qualitative

relations, and proportional analogy, whereas Mańczak has concentrated on frequency and statistics,

quantitative aspects, use in actual context, attacking the proportional formula. All this mixes up abduction

and deduction in that the emphasis has been on diachronic correspondences, between before and after,

rather than looking at the analysis of change itself. All commentators seem to agree that Mańczak fares

better (granting that the questions posed by the two are often somewhat incommensurate). Kurylowicz has

done best with his fourth law (that the new form takes on the normal unmarked function and that the old

one gets special readings). Of course, the two forms must both be attested (e.g., brothers/brethren,

mouses/mice, etc.), and mouses is hardly the unmarked “normal” form. The upshot is that neither (or no

linguist) is able to nail down all changes or to predict them, and in this Hermann Paul fares quite well, since

he said (1880: 208) that we would have to be omniscient to do that (Salm 1990: 170, 172). Paul, the great

defender of the proportional view of analogy, keeps on coming out right (Wurzel 1988; Itkonen 1999). The

practical result of analogical change classification is thus that the non-proportional configuration wins out

as the essence of the similarity-contiguity vectors (the Hermann/Coates line, as it were), although the

(“universal”) Paul proportion gives the best immediate conviction.

12/11/2007 03:35 PM

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 8 of 11

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912

The direction of analogical change remains a problem, especially if one wants to predict it. Any direction can

apparently be reversed in the right situation (Vennemann 1972b; Becker 1990). The best results have been

achieved within natural morphology, where one maintains, largely with justification, that changes tend to go

from marked to unmarked forms (see Mayerthaler 1980b; Wurzel 1989; Dressler, this volume, for further

references and discussion). Then, of course, there are problems in interpreting markedness; and social

aspects can override language structure.

The main reason why classification of analogical changes is not so interesting or useful is that similarity

cannot be predicted in advance. It needs the total context as the background.

6 Recent History in Linguistics

Linguistics has traditionally been based on analogy, both synchronically and diachronically. This has been

clearest in morphology, which tends to have analogous paradigms for its inflections. In the Ancient Greek

terminology, analogy was the regularity observed and paradigm was the example provided for its application

or manifestation (cf. a modern application in Malone 1969). This combination gave the basic notation for

handling grammatical facts, and it was in fact quite good, because analogy has been and is always used

when the object of study is not directly there. We do not observe grammar directly. A basic split occurred in

linguistics when generative grammar rejected the notion of analogy in the early 1960s, maintaining that

there is only underlying phonology and phonological rules. It is still difficult to see the rationale behind this,

because it is analogical for two reasons. First, the historical model was analogically imported into synchrony;

second, analogy was further used for positing underlying forms in borderline cases. When the tense/lax

alternation in pairs like divine/divinity, sane/sanity, etc. required uniform long or tense vowels on the

historical model, this result or knowledge had to be extended into the new unknown domain of, say, boy.

Here adherents revel - and opponents reeled - at such an extreme application of the generative

phonological method with the positing of a systematic phonetic (underlying) form /b /. Such an analogically

established form proved now that analogy does not exist, or is at least seriously inadequate, with the

concomitant claim that this was the only underlying form with psychological reality in English; a singularly

unconvincing claim, since English speakers have great difficulties in producing front rounded vowels. The

non-existent analogy was a great molder of theory in the positing of underlying forms (which were things,

not relational points), but when it came to the playback mode, analogy could be discarded.

Note that the acceptance of such a theory is also analogical: once this theory became fashionable (and we

know that anything can become fashionable in the right social conditions), it became a feature, shibboleth,

or emblem to be imitated. We have the two factors of the analogical frame: (i) the indexical identification of

this theory with contemporary prestige and future success, and (ii) the similarity extension of this feature to

(or acceptance by) the scholar who wants to belong. And most linguists wanted to belong, because it was

not only that prestige was involved, but also that the theory secured the best and best-paying jobs. This

kind of situation is the standard structure in the adoption of youth gang emblems, etc. And such social

factors are also the strongest forces behind the adoption of any language features, including sound change.

The same is true of the social aspect of sound change: Speaker

1

uses Sound

1

in Word

1

, and I use something

else. If Speaker

1

has prestige for me I might consciously or unconsciously want to imitate him or her and

adopt Sound

1

as an index of him or her or his or her class, exactly as I might copy his or her clothing style

as another index. I myself assign myself (consciously or unconsciously) to Speaker

1

's class as a potentially

similar member; thus it is again ascribed/assigned similarity, but that does not matter; it is strong causal

similarity in human action. We want to be stamped with the same die. This social aspect of change is quite

obvious and well known in dialect geography, either social or areal, and can be left out in this context.

Regular sound change has the same analogical structure: when a sound changes in Word

1

, or Group

1

, it also

changes in Word

2

, and so on (= clear proportion). This is exactly how regular sound change proceeds from

group to group and category to category, however they be defined in the particular case. The similarity

vectors are usually identical sound environments or conditions, but can also be semantic or grammatical

(see Hock and Hale, this volume). Such semantic-formal similarity is indeed what belongs to the essence of

analogy whatever the units are that are fed into the grid (cf. Coates 1987). Ever since the mid-1800s

distinctive features have been portrayed analogically: p/b = t/d, etc. (this is the static structure mode), but

then (in the structuralist era) gaps in the phoneme inventory could be expected to be filled out analogically

(in the dynamic process mode). New phonemes came about, but not new distinctive features (see Leed

1970).

12/11/2007 03:35 PM

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 9 of 11

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912

1970).

In the 1970s I was busy mapping the generative treatment of analogy (as delineated above). The first phase

away from mere phonological rules (for them) was bringing back the analogical morphological paradigm, but

under terms like distinctness conditions, leveling conditions, paradigm coherence, etc. (Anttila 1977: 98–

110). More recently the watch was taken over by Esa Itkonen, whose output is an excellent survey of the

current scene. He has run the gamut from extralinguistic reality to language (thing/action = noun/verb) and

then language structure alone (Itkonen 1994). Particularly important now is Itkonen and Haukioja (1996),

because it shows that a computer program can be written for syntactic analogy, contrary to the theoretical

claims by generativists. Analogy is indistinguishable from the traditional substitution test (Itkonen 1994:49).

Thus John / ran away is identical in structure to My oldest brother / has bought a new house (NP-1 / VP-1

= NP-2 / VP-2). Narrowing one's focus into mere physical similarity, as, for example, in Chomsky's boy /

boys = enjoy / enjoys, refutes the very structure of language (just the form part of signs in

figures 10.3

and

10.4 above

). An innate principle is needed (for generativists) to tell us that Mary is the subject in Mary

bought a dog to play with (Itkonen and Haukioja 1996: 161). Analogy with Mary bought a ball to play with

would have given a better answer straight, and furthermore, appeal to innatism means giving up on

explanations altogether, as Itkonen has been stressing. In analogy one uses known cases to understand new

or unknown cases; there is no mystery.

15

Analogy does exactly what might be considered impossible.

Similarly, Paul Kiparsky's newest name for analogy, viz. optimization, continues the line of creating new

labels that sound theoretical and innovative (Itkonen and Haukioja 1996: 162–3). One can note that a

gradual increase in regularity and system cohesion is a typical inductive matter, and on this feature alone we

see that analogy lurks there. Finally, in their treatment Itkonen and Haukioja scrutinize Jackendoff's

representative work, and show that the latter's headed hierarchy, cross-field generalization (for metaphor),

and preference rule systems all fall under analogy. “Although Jackendoff makes no attempt to formalize his

‘preference rule systems’, they have been hailed as a major discovery” (1996: 166). What was not allowed for

analogy is freely given to these disguised and distorted variants. Higher and higher-level generalizations are

a respected goal in any science, but here generative linguists go the other way; still - after all these decades.

Itkonen and Haukioja list six important implications from their work on analogy; chief among them is the

following (1996: 167):

Analogy refutes the modular conception of mind, in two complementary ways. The view that

language is a mental module entails that it is “encapsulated” both vis-à-vis extralinguistic

reality and vis-à-vis other modules. Iconicity (as an exemplification of the static analogy)

shows that language is not “encapsulated,” because perceptual structure (causally) explains

linguistic structure. Analogical inference or generalization (which represents the dynamic

aspect of analogy) is a cross-modular process which applies equally to language, vision, logic,

music, etc. and shows, eo ipso, that language is not “encapsulated” vis-à-vis other modules.

Jerry Fodor, who proposed this extraordinary wrong way (or language organ), said: “The more global a

cognitive process is, the less anybody understands it. Very global processes, like analogical reasoning, aren't

understood at all” (1983: 107). These are the “problems and mysteries” of generative grammar that live on

and are cherished within that school or its offshoots (Itkonen 1994: 50–1).

16

Analogy gives the best and

only agent for universal grammar (Itkonen 1994: 50–2; cf. also 1991).

7 Summing Up, through “Psychology and Cognitive Science”

There is one work that nicely gives the good points of analogy as they have been expounded over the past

two millennia: Holyoak and Thagard's Mental Leaps: Analogy in Creative Thought (1995). Some references

to this work have already been given. One has to note that the authors treat the period from 1980, by which

time analogy had been pretty much banned in America. They also consider only literature in English, which

has become standard procedure, and there is really no linguistics, that is, language material, in the text.

17

My treatment followed the tradition by considering the gestalt school and Peircean semiotics (i.e., since

about 1890). A surprise for many is that Holyoak and Thagard re-establish the tradition to the dot. This

Cartesian twist (real truths have to be found over and over again) was expected by those who knew the

tradition. They of course give their results as “their theory.” The expectation was that if the truth had been

found earlier, it would be found now again, if the investigation were properly carried out. And it did come

12/11/2007 03:35 PM

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 10 of 11

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912

found earlier, it would be found now again, if the investigation were properly carried out. And it did come

out.

Holyoak and Thagard's book gives it all in one place (at 320 pages the reader gets more detail than here,

even if very few hints at language). Analogy is the cognitive glory of humans, and of course it can be

followed up in other species also, particularly monkeys and apes. The authors trace the development of this

faculty in children, and then in scientists, in religion and culture, and in empathy. They also test their ideas

with computer programs. All this means exactly the same as Itkonen and Haukioja's results: analogy proves

that modularity is wrong. Analogy must be used in explanation and understanding, problem-solving,

decision-making, persuasion, communication, that is, in all kinds of learning or human activity. Analogies

are noticed, retrieved, compiled, and constructed (cf. Kaila 1945 above). Analogy is indeed the warp and

woof between similarity, structure, models, purpose, and cause (Holyoak and Thagard 1995: esp. 5–6, 22–

37, 202–9, 257–61). Humans are simply analogical animals. Language structure and language use are also

predominantly analogical, and this is why analogy is the backbone of universal grammar.

1 I have balanced out the frame of the diagram by actually writing in a text (a weaving metaphor), as an antidote

to all kinds of crazy textualities so popular today. It also reminds us which is which, if we are left cold with the

weft. But best of all, this is a direct example of perception requiring balance (closure), that is, we have a case of

“esthetic” analogy.

2 Similarity (analogy) in myth and cultural concepts comes out nicely in the basic encyclopedias, for example, the

Britannica CD 97. See also Itkonen (1994: 45) and Itkonen and Haukioja (1996: 165), as well as Holyoak and

Thagard (1995: §9).

3 In the historical surveys Esper (1973) supports the Paul line, whereas Best (1973) comes to the Hermann side.

The verdict is also clear: Paul's proportion A : A’ :: B : X → A : A’ :: B : B’ is just a special case of Hermann's A

c

::

B

c

→ A :: A'

c

(in which the subscript represents some kind of conceptual similarity, and this pushes greater formal

similarity).

4 I will take a short cut in that I refer only to the editor of this volume, not to its individual authors (for a more

detailed profile, see Anttila 1992a). This is a very important theoretical volume, never referred to, and it appeared

right at the time when linguistics started to get derailed.

5 Both isomorphism and analogy are defined as structural similarity and they are of course related (Itkonen 1994:

44).

6 Or, as youths in Central Ohio (information from Brian Joseph, pers. comm.) say, “on accident,” an analogy

squaring standard on purpose and by accident.

7 In this rich literature on metaphor under cognitive auspices, there is usually no mention of the Shapiros’ work

(e.g., Shapiro and Shapiro 1988; and earlier). This is the tradition that has produced the most exciting work on

metaphor, Haley (1988). Now one must add/peruse Keller (1995). I would further single out Bosch (1985) and

Bencze (1989), as they come to a position very compatible with the one delineated above. Among other things,

they emphasize the context (field) and do not draw a line between normal and figurative readings. Bencze

addresses the issue of determination almost in Peircean terms and treats symmetry dynamics with reference to

some of the same authors von Slagle (1974; see Anttila 1992a) was relying on when he stressed the same.

Danesi's work has the added bonus and interest that he refers to Vico and Nietzsche for emphasizing the primacy

of metaphor. Metaphor is the backbone of all cognition and there is no knowledge apart from it (Danesi 1987:

157, 159, 160–1, 163, 1990: 228). Context is crucial, which shows an immediate affinity to analogy. In the

dispute over the literal versus figurative readings, the metaphors are basic, primary (Danesi 1987: 160, 162), and

this makes the generative position totally wrong (for more references, see Anttila 1992a).

8 I myself have fallen under the same criticism in my defense of analogy, which I took as the same kind of

backbone in Anttila (1989, 1977) as the cognitive linguists now use metaphor for. Curiously, this kind of work on

analogy has never been referred to in the cognitive linguistics context, although analogy is now a commonplace in

artificial intelligence (AI). There tends to be this distribution: analogy in artificial intelligence, metaphor in cognitive

linguistics, and both in philosophy of science, from which then metaphor does also enter AI (see, e.g., Thagard

1988; Helman 1988). Ever since Aristotle, analogy has been the basic category for talking about cognition. Thus it

is no wonder that linguists return to it after aberrations. This happened ultimately in generative grammar (Anttila

1977; and see Itkonen's work below). Now all kinds of terminological equivalences must be known, a great burden

in the field.

12/11/2007 03:35 PM

10. Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition : The Handbook of Historical Linguistics : Blackwell Reference Online

Page 11 of 11

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912

in the field.

9 Metaphor is a prime example of analogy (Itkonen 1994: 46). Analogy and metaphor are the same and not the

same (Holyoak and Thagard 1995: 220, 223, 235).

10 Of course, if we want to be really scholarly we might put this into Greek: meaning is schizoantikeimenic and

schizosemasic. It is now that analogy starts to sound good, and it also is Greek.

11 We have here an often-noted problem in the current field. If such ignorance is real ignorance, it means serious

incompetence. If it is done on purpose, it does not deny incompetence, but adds a damning moral flaw, not earlier

tolerated in scholarship. Today both aspects are tolerated, as long as the “scholar” makes a name for himself or

herself.

12 Andersen (1973), a deservedly influential article, is flawed in that it treats abduction and deduction only, clearly

giving emphasis to the latter. Its “flavor” is against analogy, and thus it was no wonder that Savan (1980) had to

put induction in there, a fact not noticed by many.

13 Some modern readers might miss the point that átopon, from Greek α- ‘un’ + τoπ- ‘place,’ has the same

semantic elements as utopia, from Greek ??- ‘not’ + τoπ- ‘place,’ as well as the beginning of topology.

14 This indexical tension is again a facet of the larger well-known component of “strangeness” (the átopon) in

hermeneutics, which also lurks in dissonance and coherence theories of meaning (cf., e.g., Itkonen 1983: 205–6;

Anttila 1989: 405–7, 409–11).

15 The generativists reverse this procedure, even taking as a norm something that never happens (Itkonen 1983:

309).

16 A good state-of-the-art position on modularist thinking (or avoidance of thinking?) is Fromkin (1997); see also

Haukioja (1993 with his discussion with Fromkin, pp. 398–405).

17 A brief bibliography of the history of analogical treatments around language can be had through a combination

of Best (1973), Esper (1973), Anttila (1977), Anttila and Brewer (1977), and Mayerthaler (1980a).

Cite this article

ANTTILA, RAIMO. "Analogy: The Warp and Woof of Cognition." The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Joseph,

Brian D. and Richard D. Janda (eds). Blackwell Publishing, 2004. Blackwell Reference Online. 11 December 2007

<http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/tocnode?id=g9781405127479_chunk_g978140512747912>

Bibliographic Details

The Handbook of Historical Linguistics

Edited by: Brian D. Joseph And Richard D. Janda

eISBN: 9781405127479

Print publication date: 2004

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Guide to the properties and uses of detergents in biology and biochemistry

Sterne The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

SHSBC418 The Progress and Future of Scientology

Theory and practise of teaching history 18.10.2011, PWSZ, Theory and practise of teaching history

ebook Martial Arts The History and Philosophy of Wing Chun Kung Fu

Herrick The History and Theory of Rhetoric (27)

Becker The quantity and quality of life and the evolution of world inequality

The Disproof and proof of Everything

The positive and negative?fects of dna profiling

The Agriculture and?onomics of Peru

The Goals and?ilures of the First and Second Reconstructio

The Differences and Similarities of Pneumonia and Tuberculosi

The?vantages and disadvantages of travelling by?r

The problems in the?scription and classification of vovels

więcej podobnych podstron